Combined Diet and Exercise for Health: Green Prescription Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/20

|10

|7966

|99

Report

AI Summary

This research article, published in BMC Public Health in 2018, investigates the impact of the Green Prescription program in New Zealand, a primary care intervention focused on improving patient health through exercise prescriptions. The study analyzed data from a survey of 1488 patients, examining the effects of changing diet and increasing physical activity on various health parameters, including metabolic, physiological, and psychological outcomes. The findings reveal that combined diet and exercise interventions lead to superior health improvements compared to either diet or exercise alone, particularly in weight loss, blood pressure reduction, and cholesterol management. The study emphasizes the potential benefits of incorporating nutrition education into the Green Prescription initiative, especially for patients with metabolic health problems, and underscores the importance of addressing both physical activity and dietary behaviors to maximize positive health outcomes within primary care settings. The research highlights the need for policy-makers to consider nutrition education as a key component of the Green Prescription program, offering a comprehensive approach to disease prevention and health promotion.

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

Combined diet and physicalactivity is

better than diet or physicalactivity alone at

improving health outcomes for patients in

New Zealand’s primary care intervention

Catherine Anne Elliot* and MichaelJohn Hamlin

Abstract

Background:A dearth of knowledge exists regarding how multiple health behavior changes made within an

exercise prescription programme can improve health parameters.This study aimed to analyse the impact of

changing diet and increasing exercise on health improvements among exercise prescription patients.

Methods:In 2016,a representative sample of allenroled New Zealand exercise prescription programme (Green

Prescription) patients were surveyed (N = 1488,29% male,46% ≥ 60 yr).Seven subsamples were created according

to their associated health problems;metabolic (n = 1192),physiological(n = 627),psychological(n = 447),sleep

problems (n = 253),breathing difficulties (n = 243),fallprevention (n = 104),and smoking (n = 67).After controlling

for sex and age,multinomialregression analyses were executed.

Results:Overall,weight problems were most prevalent (n = 886,60%),followed by high blood pressure/risk of

stroke (n = 424,29%),arthritis (n = 397,27%),and back pain/problems (n = 382,26%).Among patients who

reported metabolic health problems,those who changed their diet were 7.2,2.4 and 3.5 times more likely to lose

weight,lower their blood pressure,and lower their cholesterol,respectively compared to the controlgroup.

Moreover,those who increased their physicalactivity levels were 5.2 times more likely to lose weight in comparison

to controls.Patients who both increased physicalactivity and improved diet revealed higher odds of experiencing

health improvements than those who only made one change.Most notably,the odds of losing weight were much

higher for patients changing both behaviours (17.5) versus changing only physicalactivity (5.2) or only diet (7.2).

Conclusions:Although it is not currently a programme objective,policy-makers could include nutrition education

within the Green Prescription initiative,particularly for the 55% of patients who changed their diet while in the

programme.Physicalactivity prescription with a complimentary nutrition education component could benefit t

largest group of patients who report metabolic health problems.

Keywords:Primary care intervention,Physicalactivity,Exercise prescription,Disease prevention,Diet,Metabolic

health,Physiologic,Psychologic,Behavior change,Nutrition

* Correspondence:catherine.elliot@lincoln.ac.nz

Department of Tourism,Sport and Society,Lincoln University,PO Box 85084,

Lincoln,Christchurch,Canterbury 7647,New Zealand

© The Author(s).2018 Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5152-z

Combined diet and physicalactivity is

better than diet or physicalactivity alone at

improving health outcomes for patients in

New Zealand’s primary care intervention

Catherine Anne Elliot* and MichaelJohn Hamlin

Abstract

Background:A dearth of knowledge exists regarding how multiple health behavior changes made within an

exercise prescription programme can improve health parameters.This study aimed to analyse the impact of

changing diet and increasing exercise on health improvements among exercise prescription patients.

Methods:In 2016,a representative sample of allenroled New Zealand exercise prescription programme (Green

Prescription) patients were surveyed (N = 1488,29% male,46% ≥ 60 yr).Seven subsamples were created according

to their associated health problems;metabolic (n = 1192),physiological(n = 627),psychological(n = 447),sleep

problems (n = 253),breathing difficulties (n = 243),fallprevention (n = 104),and smoking (n = 67).After controlling

for sex and age,multinomialregression analyses were executed.

Results:Overall,weight problems were most prevalent (n = 886,60%),followed by high blood pressure/risk of

stroke (n = 424,29%),arthritis (n = 397,27%),and back pain/problems (n = 382,26%).Among patients who

reported metabolic health problems,those who changed their diet were 7.2,2.4 and 3.5 times more likely to lose

weight,lower their blood pressure,and lower their cholesterol,respectively compared to the controlgroup.

Moreover,those who increased their physicalactivity levels were 5.2 times more likely to lose weight in comparison

to controls.Patients who both increased physicalactivity and improved diet revealed higher odds of experiencing

health improvements than those who only made one change.Most notably,the odds of losing weight were much

higher for patients changing both behaviours (17.5) versus changing only physicalactivity (5.2) or only diet (7.2).

Conclusions:Although it is not currently a programme objective,policy-makers could include nutrition education

within the Green Prescription initiative,particularly for the 55% of patients who changed their diet while in the

programme.Physicalactivity prescription with a complimentary nutrition education component could benefit t

largest group of patients who report metabolic health problems.

Keywords:Primary care intervention,Physicalactivity,Exercise prescription,Disease prevention,Diet,Metabolic

health,Physiologic,Psychologic,Behavior change,Nutrition

* Correspondence:catherine.elliot@lincoln.ac.nz

Department of Tourism,Sport and Society,Lincoln University,PO Box 85084,

Lincoln,Christchurch,Canterbury 7647,New Zealand

© The Author(s).2018 Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5152-z

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Background

A lack of physicalactivity,tobacco smoking and an

unhealthy dietcontribute to almost80% ofthe world’s

risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [1].Po-

sitioned as the leading cause of premature death globally

[2],cardiovascular disease is an epidemic driven by type

2 diabetesand the metabolic syndrome [3].Empirical

evidence suggests thatthe co-occurrence ofbehavioral

risk factors yield greater risks for chronic diseases than

the sum oftheir individualindependenteffects [4,5].

For instance,individuals who are diagnosed with meta-

bolic syndrome show a 50-60% higher risk ofhaving a

cardiovascular disease than those without metabolic syn-

drome [6].With an estimated 20-25% ofthe world’s

adult population presentingmetabolicsyndrome[3],

multiple disease risk factors are increasingly common in

adults [7].

Major risk factors of cardiovascular disease and meta-

bolic syndrome are physicalinactivity and poor diet [8]

with physicalinactivity positioned as the primary cause

of most chronic diseases[9]. Although compelling

evidence existsfor the efficacy ofimproving physical

activity and diet [10] in treating individuals with multiple

risk factors [11],usualcare relies on pharmacotherapies

which merely address disease symptoms [12].

Cardiovascular disease is the number one single cause

of death in New Zealand,accounting for 33% per annum

[13].In 1998,New Zealand actively addressed this con-

cern by initiating aprimary-careintervention strategy

called Green Prescription,whereby generalpractitioners

and practice nurses refer or prescribe eligible patients to

trained personnel[14].Nearly 40,000 Green Prescription

referrals were written by clinicians in New Zealand from

2013 to 2014 [15].Green Prescription patientsmight

receive an exercise prescription for any combination of

cardiorespiratory,metabolic,physiologicalor psycho-

logical reasons.Once enroled,patients meet with physical

activity specialists who customise a physicalactivity rou-

tine which is catered to the patients’needs and lifestyles

while addressing barrierssuch asasthma,injury,back

pain, etc.

The Green Prescription Programmeis akin to a

globallyadoptedhealth initiativecalled Exerciseis

Medicine.Since both programmes focus on increasing

physical activity a as means of chronic disease

prevention,there is little scope to focus on the nutri-

tional componentof the energybalanceequation.

Nevertheless,68% of survey respondentsreported

they have receivedinformationon healthy eating

through Green Prescription.Additionally,55% of

patientsin the subsamplesanalysedin this study

reported changingdiet as well as physicalactivity.

From a physiologicalperspective,the energy balance

behaviors ofincreasing physicalactivity and changing

diet are major preventivetherapies,particularlyfor

weightloss,[10,16] but also for metabolic syndrome

[11] and cardiovasculardisease[17]. Evidencesug-

gests an increasedlikelihood of weight loss when

multiple health behaviorchangesare implemented

compared to one [10,16, 18].From a behavioraland

motivationalself-regulationstandpoint,the synergistic

effectsof improvingdiet and physicalactivityhave

been investigated.A study from Mata et al. [19]

showed that physical activity self-determination

predicted eating self-regulation and fully mediated the

relationship between physicalactivity and eating self-

regulation during a lifestyle weight-management

programme[19]. This suggeststhat psychological

mechanismsinvolved in motivation may help explain

the association between physicalactivityand eating

behaviors.Nevertheless,there is a dearth of know-

ledge regarding the effects ofmultiple health behavior

changesby exercise prescription patientsto improve

metabolic,physiologicaland psychologicaloutcomes.

This study aimed to analyse the impactof changing

diet and increasing exercise on health improvements

among exercise prescription patients.

Methods

The ethics application for this study was considered and

subsequently waived by the Health and Disability Ethics

Committees in New Zealand due to the research being

an evaluation of an existing programme.Responses were

collected on an informed consentbasis as partof the

17th annualGreen Prescription patientsurvey.The

survey was administered by Research New Zealand as

contracted by the NZ Ministry of Health to measure the

performance of Green Prescription.

This mixed-method online,telephone and paper-based

survey wasconducted from March-May 2016 using a

stratified random sample.Green Prescription patients

who had contact with one ofthe 17 Green Prescription

contractholdersin all DistrictHealth Boardsover 6

months from July-December2015 were eligiblefor

sampling.

Sample

Contract holders throughout New Zealand,who are re-

sponsible for delivering the nationalGreen Prescription

Programme,submitted theirpatientlist to Research

New Zealand, totaling 18,849 Green Prescription

patients throughout the country.Historically,there have

been lower survey response rates among minority groups

enroled in Green Prescription,namely,Māori and Pacific.

Assuming a low response rate,an oversampling ofthese

groups was executed to help ensure a more ethnically-

representative sample ofpatients.In the total sample,

European New Zealanderrespondentscomprised 59%,

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 2 of 10

A lack of physicalactivity,tobacco smoking and an

unhealthy dietcontribute to almost80% ofthe world’s

risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [1].Po-

sitioned as the leading cause of premature death globally

[2],cardiovascular disease is an epidemic driven by type

2 diabetesand the metabolic syndrome [3].Empirical

evidence suggests thatthe co-occurrence ofbehavioral

risk factors yield greater risks for chronic diseases than

the sum oftheir individualindependenteffects [4,5].

For instance,individuals who are diagnosed with meta-

bolic syndrome show a 50-60% higher risk ofhaving a

cardiovascular disease than those without metabolic syn-

drome [6].With an estimated 20-25% ofthe world’s

adult population presentingmetabolicsyndrome[3],

multiple disease risk factors are increasingly common in

adults [7].

Major risk factors of cardiovascular disease and meta-

bolic syndrome are physicalinactivity and poor diet [8]

with physicalinactivity positioned as the primary cause

of most chronic diseases[9]. Although compelling

evidence existsfor the efficacy ofimproving physical

activity and diet [10] in treating individuals with multiple

risk factors [11],usualcare relies on pharmacotherapies

which merely address disease symptoms [12].

Cardiovascular disease is the number one single cause

of death in New Zealand,accounting for 33% per annum

[13].In 1998,New Zealand actively addressed this con-

cern by initiating aprimary-careintervention strategy

called Green Prescription,whereby generalpractitioners

and practice nurses refer or prescribe eligible patients to

trained personnel[14].Nearly 40,000 Green Prescription

referrals were written by clinicians in New Zealand from

2013 to 2014 [15].Green Prescription patientsmight

receive an exercise prescription for any combination of

cardiorespiratory,metabolic,physiologicalor psycho-

logical reasons.Once enroled,patients meet with physical

activity specialists who customise a physicalactivity rou-

tine which is catered to the patients’needs and lifestyles

while addressing barrierssuch asasthma,injury,back

pain, etc.

The Green Prescription Programmeis akin to a

globallyadoptedhealth initiativecalled Exerciseis

Medicine.Since both programmes focus on increasing

physical activity a as means of chronic disease

prevention,there is little scope to focus on the nutri-

tional componentof the energybalanceequation.

Nevertheless,68% of survey respondentsreported

they have receivedinformationon healthy eating

through Green Prescription.Additionally,55% of

patientsin the subsamplesanalysedin this study

reported changingdiet as well as physicalactivity.

From a physiologicalperspective,the energy balance

behaviors ofincreasing physicalactivity and changing

diet are major preventivetherapies,particularlyfor

weightloss,[10,16] but also for metabolic syndrome

[11] and cardiovasculardisease[17]. Evidencesug-

gests an increasedlikelihood of weight loss when

multiple health behaviorchangesare implemented

compared to one [10,16, 18].From a behavioraland

motivationalself-regulationstandpoint,the synergistic

effectsof improvingdiet and physicalactivityhave

been investigated.A study from Mata et al. [19]

showed that physical activity self-determination

predicted eating self-regulation and fully mediated the

relationship between physicalactivity and eating self-

regulation during a lifestyle weight-management

programme[19]. This suggeststhat psychological

mechanismsinvolved in motivation may help explain

the association between physicalactivityand eating

behaviors.Nevertheless,there is a dearth of know-

ledge regarding the effects ofmultiple health behavior

changesby exercise prescription patientsto improve

metabolic,physiologicaland psychologicaloutcomes.

This study aimed to analyse the impactof changing

diet and increasing exercise on health improvements

among exercise prescription patients.

Methods

The ethics application for this study was considered and

subsequently waived by the Health and Disability Ethics

Committees in New Zealand due to the research being

an evaluation of an existing programme.Responses were

collected on an informed consentbasis as partof the

17th annualGreen Prescription patientsurvey.The

survey was administered by Research New Zealand as

contracted by the NZ Ministry of Health to measure the

performance of Green Prescription.

This mixed-method online,telephone and paper-based

survey wasconducted from March-May 2016 using a

stratified random sample.Green Prescription patients

who had contact with one ofthe 17 Green Prescription

contractholdersin all DistrictHealth Boardsover 6

months from July-December2015 were eligiblefor

sampling.

Sample

Contract holders throughout New Zealand,who are re-

sponsible for delivering the nationalGreen Prescription

Programme,submitted theirpatientlist to Research

New Zealand, totaling 18,849 Green Prescription

patients throughout the country.Historically,there have

been lower survey response rates among minority groups

enroled in Green Prescription,namely,Māori and Pacific.

Assuming a low response rate,an oversampling ofthese

groups was executed to help ensure a more ethnically-

representative sample ofpatients.In the total sample,

European New Zealanderrespondentscomprised 59%,

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 2 of 10

Māori 28% and Pacific 13%.The firststep in the data

collection processentailed separating largercontract

holders(with > 700patients)from smallercontract

holders.A sample of n = 2440Māori and Pacific

patientswas randomlyselected from thecombined

lists of the larger contractholders,proportionalto

the total numberof Māori and Pacific patientson

these lists.All patients with known contactdetails on

the lists of smallercontractholders(n = 4560)were

also selected.Finally, a random sample(n = 3000)

was selected from theremaininglists of the larger

contractholders in proportion with the totalnumber

of non-Māori/Pacific patients.

On 7th March 2016,selected patientsweresent a

letter from Research New Zealand invitingthem to

participate,along with a paper copy of the survey,and a

reply-paid envelope with three $250 giftvouchers used

as incentive.The letterintroduced the survey and its

purpose and gave instructions for completing the survey

on paper or online.On 30 March 2016,4657 patients

who had not yet responded were sent a reminder letter

and 1052 were sent a reminder email.Commencing 30

April 2015,a remindercall was made to all non-

responding Māoriand Pacific patients (n = 1973),and

non-Māori and Pacific patients (n = 960).Of these,1478

were contacted during the remindercall period (each

was called a maximum of five times).The main survey-

ing period ended on 15 May 2016.

To account for the varying sampling criteria applied to

large and small contract holders and the different participa-

tion rates,the results were weighted to be representative of

the proportion of patients from each contract holder.The

weighted results for the total sample have a maximum mar

gin of error of plus or minus 1.8%,at the 95% confidence

level (p. 15) [20].

Participation rate

A representative sample of10,000 patients were invited

to complete the survey.A totalof n = 2843 valid,com-

pleted responses were received during the survey period

(n = 2045 paper,n = 496 online,and n = 302 telephone),

representing a participation rate of28% [20].Data was

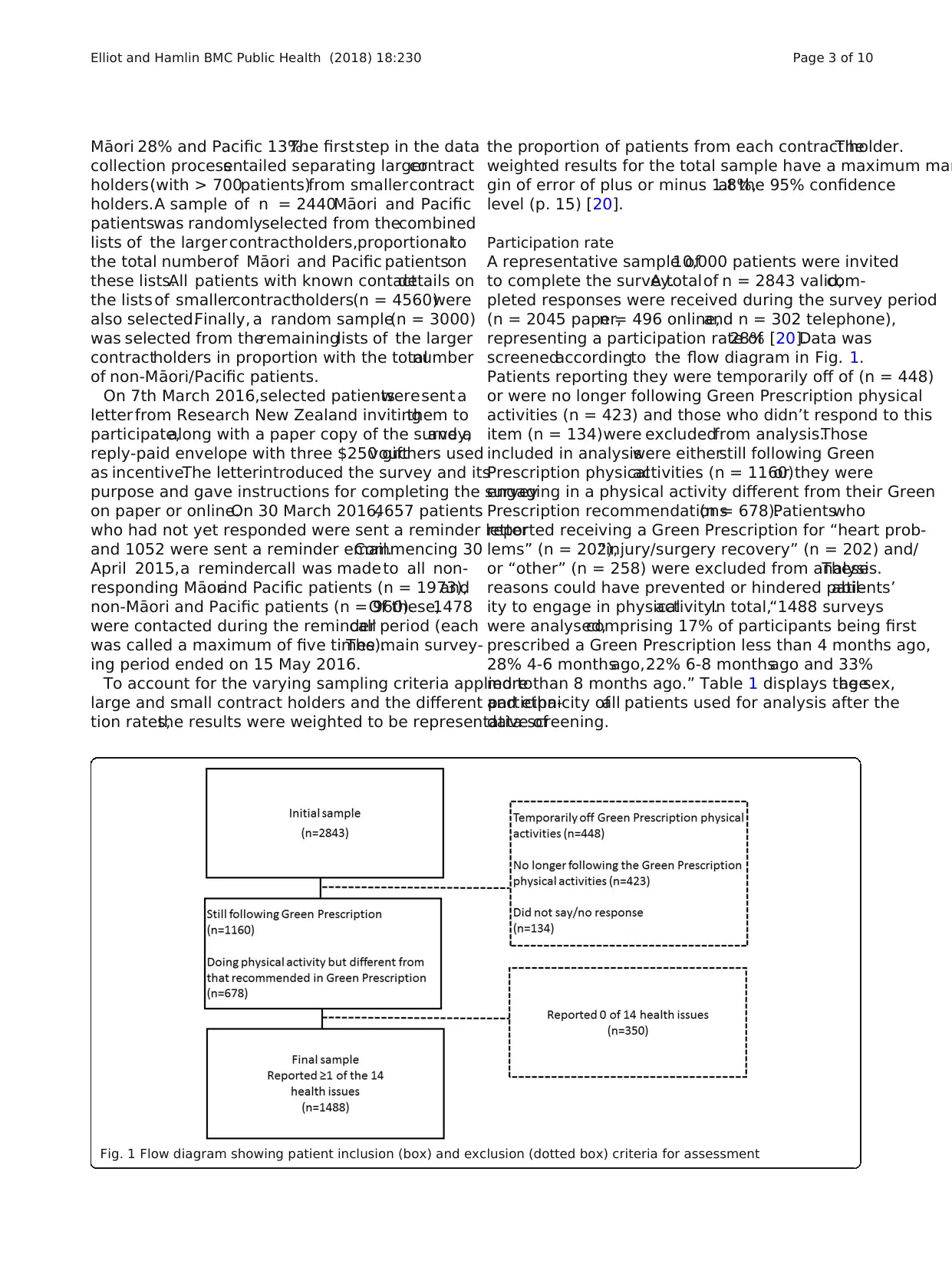

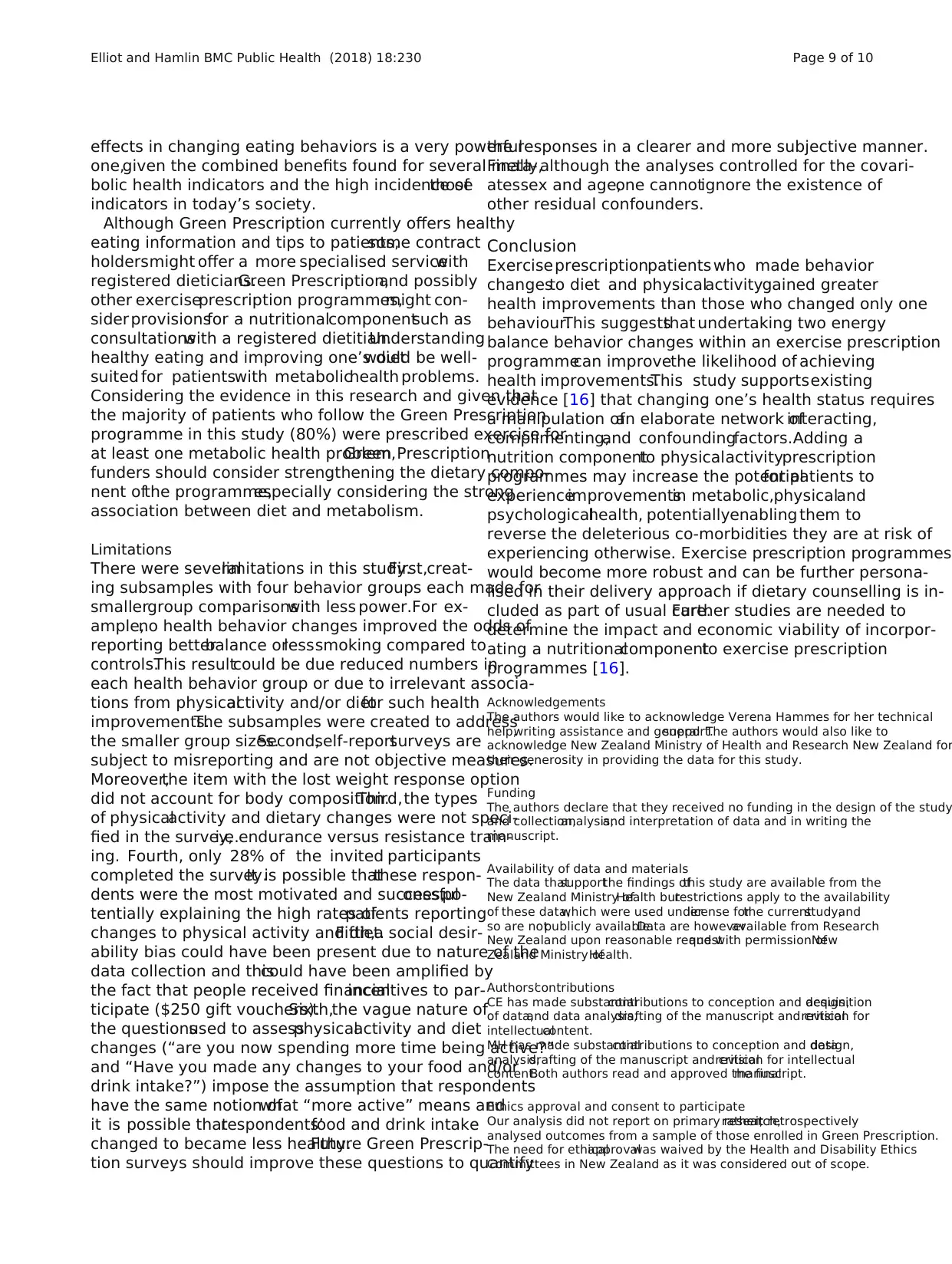

screenedaccordingto the flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Patients reporting they were temporarily off of (n = 448)

or were no longer following Green Prescription physical

activities (n = 423) and those who didn’t respond to this

item (n = 134)were excludedfrom analysis.Those

included in analysiswere eitherstill following Green

Prescription physicalactivities (n = 1160)or they were

engaging in a physical activity different from their Green

Prescription recommendations(n = 678).Patientswho

reported receiving a Green Prescription for “heart prob-

lems” (n = 202),“injury/surgery recovery” (n = 202) and/

or “other” (n = 258) were excluded from analysis.These

reasons could have prevented or hindered patients’abil-

ity to engage in physicalactivity.In total,“1488 surveys

were analysed,comprising 17% of participants being first

prescribed a Green Prescription less than 4 months ago,

28% 4-6 monthsago,22% 6-8 monthsago and 33%

more than 8 months ago.” Table 1 displays the sex,age

and ethnicity ofall patients used for analysis after the

data screening.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram showing patient inclusion (box) and exclusion (dotted box) criteria for assessment

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 3 of 10

collection processentailed separating largercontract

holders(with > 700patients)from smallercontract

holders.A sample of n = 2440Māori and Pacific

patientswas randomlyselected from thecombined

lists of the larger contractholders,proportionalto

the total numberof Māori and Pacific patientson

these lists.All patients with known contactdetails on

the lists of smallercontractholders(n = 4560)were

also selected.Finally, a random sample(n = 3000)

was selected from theremaininglists of the larger

contractholders in proportion with the totalnumber

of non-Māori/Pacific patients.

On 7th March 2016,selected patientsweresent a

letter from Research New Zealand invitingthem to

participate,along with a paper copy of the survey,and a

reply-paid envelope with three $250 giftvouchers used

as incentive.The letterintroduced the survey and its

purpose and gave instructions for completing the survey

on paper or online.On 30 March 2016,4657 patients

who had not yet responded were sent a reminder letter

and 1052 were sent a reminder email.Commencing 30

April 2015,a remindercall was made to all non-

responding Māoriand Pacific patients (n = 1973),and

non-Māori and Pacific patients (n = 960).Of these,1478

were contacted during the remindercall period (each

was called a maximum of five times).The main survey-

ing period ended on 15 May 2016.

To account for the varying sampling criteria applied to

large and small contract holders and the different participa-

tion rates,the results were weighted to be representative of

the proportion of patients from each contract holder.The

weighted results for the total sample have a maximum mar

gin of error of plus or minus 1.8%,at the 95% confidence

level (p. 15) [20].

Participation rate

A representative sample of10,000 patients were invited

to complete the survey.A totalof n = 2843 valid,com-

pleted responses were received during the survey period

(n = 2045 paper,n = 496 online,and n = 302 telephone),

representing a participation rate of28% [20].Data was

screenedaccordingto the flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Patients reporting they were temporarily off of (n = 448)

or were no longer following Green Prescription physical

activities (n = 423) and those who didn’t respond to this

item (n = 134)were excludedfrom analysis.Those

included in analysiswere eitherstill following Green

Prescription physicalactivities (n = 1160)or they were

engaging in a physical activity different from their Green

Prescription recommendations(n = 678).Patientswho

reported receiving a Green Prescription for “heart prob-

lems” (n = 202),“injury/surgery recovery” (n = 202) and/

or “other” (n = 258) were excluded from analysis.These

reasons could have prevented or hindered patients’abil-

ity to engage in physicalactivity.In total,“1488 surveys

were analysed,comprising 17% of participants being first

prescribed a Green Prescription less than 4 months ago,

28% 4-6 monthsago,22% 6-8 monthsago and 33%

more than 8 months ago.” Table 1 displays the sex,age

and ethnicity ofall patients used for analysis after the

data screening.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram showing patient inclusion (box) and exclusion (dotted box) criteria for assessment

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 3 of 10

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

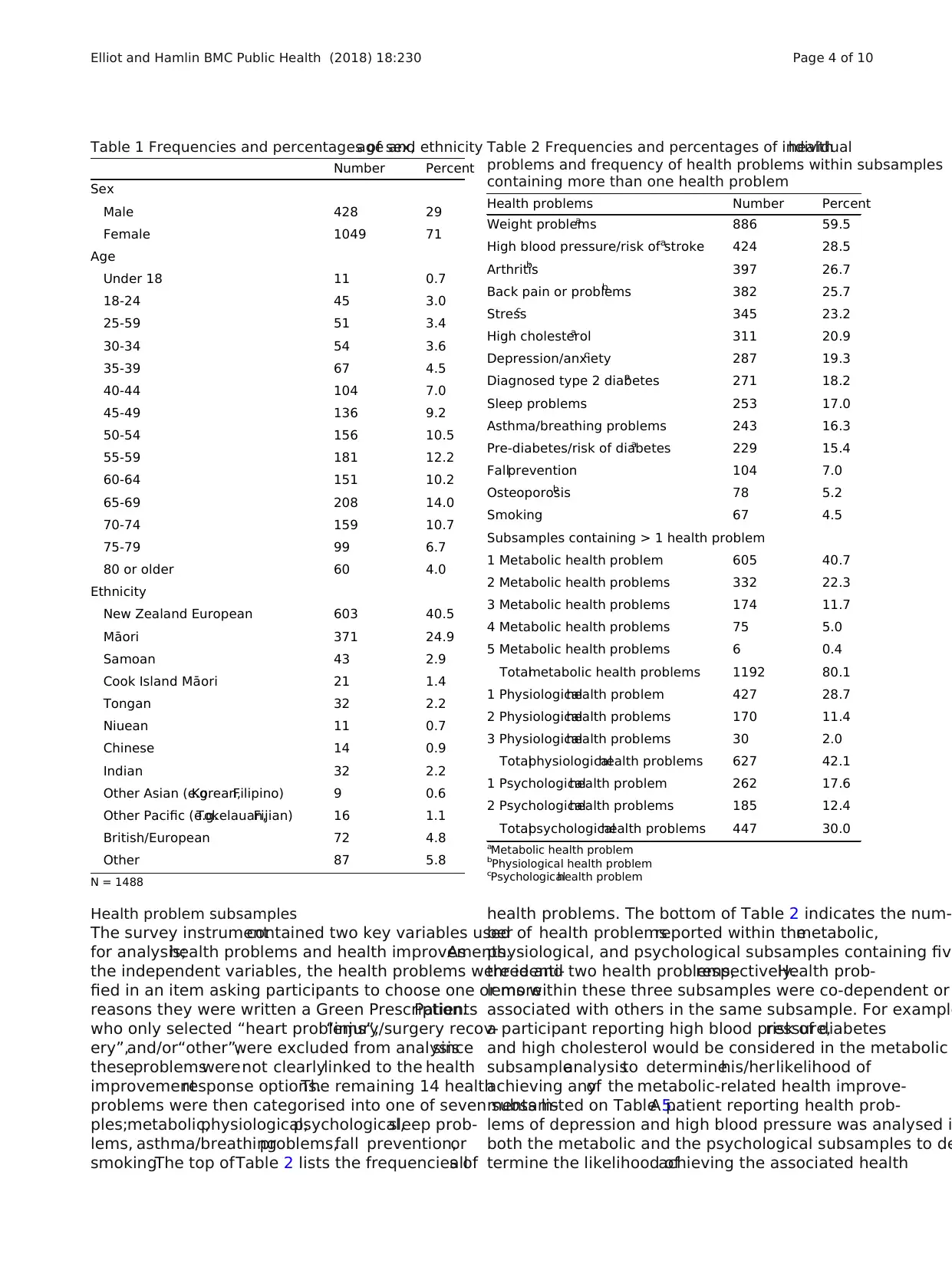

Health problem subsamples

The survey instrumentcontained two key variables used

for analysis;health problems and health improvements.As

the independent variables, the health problems were identi-

fied in an item asking participants to choose one or more

reasons they were written a Green Prescription.Patients

who only selected “heart problems”,“injury/surgery recov-

ery”,and/or“other”,were excluded from analysissince

theseproblemswerenot clearlylinked to the health

improvementresponse options.The remaining 14 health

problems were then categorised into one of seven subsam-

ples;metabolic,physiological,psychological,sleep prob-

lems, asthma/breathingproblems,fall prevention,or

smoking.The top ofTable 2 lists the frequencies ofall

health problems. The bottom of Table 2 indicates the num-

ber of health problemsreported within themetabolic,

physiological, and psychological subsamples containing five

three and two health problems,respectively.Health prob-

lems within these three subsamples were co-dependent or

associated with others in the same subsample. For example

a participant reporting high blood pressure,risk of diabetes

and high cholesterol would be considered in the metabolic

subsampleanalysisto determinehis/herlikelihood of

achieving anyof the metabolic-related health improve-

ments listed on Table 5.A patient reporting health prob-

lems of depression and high blood pressure was analysed i

both the metabolic and the psychological subsamples to de

termine the likelihood ofachieving the associated health

Table 1 Frequencies and percentages of sex,age and ethnicity

Number Percent

Sex

Male 428 29

Female 1049 71

Age

Under 18 11 0.7

18-24 45 3.0

25-59 51 3.4

30-34 54 3.6

35-39 67 4.5

40-44 104 7.0

45-49 136 9.2

50-54 156 10.5

55-59 181 12.2

60-64 151 10.2

65-69 208 14.0

70-74 159 10.7

75-79 99 6.7

80 or older 60 4.0

Ethnicity

New Zealand European 603 40.5

Māori 371 24.9

Samoan 43 2.9

Cook Island Māori 21 1.4

Tongan 32 2.2

Niuean 11 0.7

Chinese 14 0.9

Indian 32 2.2

Other Asian (e.g.Korean,Filipino) 9 0.6

Other Pacific (e.g.Tokelauan,Fijian) 16 1.1

British/European 72 4.8

Other 87 5.8

N = 1488

Table 2 Frequencies and percentages of individualhealth

problems and frequency of health problems within subsamples

containing more than one health problem

Health problems Number Percent

Weight problemsa 886 59.5

High blood pressure/risk of strokea 424 28.5

Arthritisb 397 26.7

Back pain or problemsb 382 25.7

Stressc 345 23.2

High cholesterola 311 20.9

Depression/anxietyc 287 19.3

Diagnosed type 2 diabetesa 271 18.2

Sleep problems 253 17.0

Asthma/breathing problems 243 16.3

Pre-diabetes/risk of diabetesa 229 15.4

Fallprevention 104 7.0

Osteoporosisb 78 5.2

Smoking 67 4.5

Subsamples containing > 1 health problem

1 Metabolic health problem 605 40.7

2 Metabolic health problems 332 22.3

3 Metabolic health problems 174 11.7

4 Metabolic health problems 75 5.0

5 Metabolic health problems 6 0.4

Totalmetabolic health problems 1192 80.1

1 Physiologicalhealth problem 427 28.7

2 Physiologicalhealth problems 170 11.4

3 Physiologicalhealth problems 30 2.0

Totalphysiologicalhealth problems 627 42.1

1 Psychologicalhealth problem 262 17.6

2 Psychologicalhealth problems 185 12.4

Totalpsychologicalhealth problems 447 30.0

aMetabolic health problem

bPhysiological health problem

cPsychologicalhealth problem

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 4 of 10

The survey instrumentcontained two key variables used

for analysis;health problems and health improvements.As

the independent variables, the health problems were identi-

fied in an item asking participants to choose one or more

reasons they were written a Green Prescription.Patients

who only selected “heart problems”,“injury/surgery recov-

ery”,and/or“other”,were excluded from analysissince

theseproblemswerenot clearlylinked to the health

improvementresponse options.The remaining 14 health

problems were then categorised into one of seven subsam-

ples;metabolic,physiological,psychological,sleep prob-

lems, asthma/breathingproblems,fall prevention,or

smoking.The top ofTable 2 lists the frequencies ofall

health problems. The bottom of Table 2 indicates the num-

ber of health problemsreported within themetabolic,

physiological, and psychological subsamples containing five

three and two health problems,respectively.Health prob-

lems within these three subsamples were co-dependent or

associated with others in the same subsample. For example

a participant reporting high blood pressure,risk of diabetes

and high cholesterol would be considered in the metabolic

subsampleanalysisto determinehis/herlikelihood of

achieving anyof the metabolic-related health improve-

ments listed on Table 5.A patient reporting health prob-

lems of depression and high blood pressure was analysed i

both the metabolic and the psychological subsamples to de

termine the likelihood ofachieving the associated health

Table 1 Frequencies and percentages of sex,age and ethnicity

Number Percent

Sex

Male 428 29

Female 1049 71

Age

Under 18 11 0.7

18-24 45 3.0

25-59 51 3.4

30-34 54 3.6

35-39 67 4.5

40-44 104 7.0

45-49 136 9.2

50-54 156 10.5

55-59 181 12.2

60-64 151 10.2

65-69 208 14.0

70-74 159 10.7

75-79 99 6.7

80 or older 60 4.0

Ethnicity

New Zealand European 603 40.5

Māori 371 24.9

Samoan 43 2.9

Cook Island Māori 21 1.4

Tongan 32 2.2

Niuean 11 0.7

Chinese 14 0.9

Indian 32 2.2

Other Asian (e.g.Korean,Filipino) 9 0.6

Other Pacific (e.g.Tokelauan,Fijian) 16 1.1

British/European 72 4.8

Other 87 5.8

N = 1488

Table 2 Frequencies and percentages of individualhealth

problems and frequency of health problems within subsamples

containing more than one health problem

Health problems Number Percent

Weight problemsa 886 59.5

High blood pressure/risk of strokea 424 28.5

Arthritisb 397 26.7

Back pain or problemsb 382 25.7

Stressc 345 23.2

High cholesterola 311 20.9

Depression/anxietyc 287 19.3

Diagnosed type 2 diabetesa 271 18.2

Sleep problems 253 17.0

Asthma/breathing problems 243 16.3

Pre-diabetes/risk of diabetesa 229 15.4

Fallprevention 104 7.0

Osteoporosisb 78 5.2

Smoking 67 4.5

Subsamples containing > 1 health problem

1 Metabolic health problem 605 40.7

2 Metabolic health problems 332 22.3

3 Metabolic health problems 174 11.7

4 Metabolic health problems 75 5.0

5 Metabolic health problems 6 0.4

Totalmetabolic health problems 1192 80.1

1 Physiologicalhealth problem 427 28.7

2 Physiologicalhealth problems 170 11.4

3 Physiologicalhealth problems 30 2.0

Totalphysiologicalhealth problems 627 42.1

1 Psychologicalhealth problem 262 17.6

2 Psychologicalhealth problems 185 12.4

Totalpsychologicalhealth problems 447 30.0

aMetabolic health problem

bPhysiological health problem

cPsychologicalhealth problem

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 4 of 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

improvements (i.e.lower blood pressure,feeling less de-

pressed/anxious). Combining health problems into subsam-

ples made for a more robust analysis.

Measures

Health behaviour

The health behaviorpredictorvariablewas used to

create fourbehaviourchange groupsfor comparison;

1. increased physicalactivity,2. changed diet(diet),3.

increased physicalactivity and changed diet(physical

activity and diet),or 4. no changes to physicalactivity

and diet(controlgroup).Groupingswere created by

using responsesfrom two items regardingbehavior

changesto physicalactivityand diet. The physical

activityitem was, “Compared with thetime before

you were first given a Green Prescription,are you

now spending more time being active,aboutthe same

amount of time being active or less time being

active?” Patients choosing the latter two options were

combinedinto the group “no increasein physical

activity.”The diet item was, “Haveyou made any

changes to your food and/or drink intake since being

given yourGreen Prescription?”and contained “yes”

and “no”response options.Table 3 indicates the fre-

quenciesof health problemsfor all four behaviour

change groups.

Health improvements

There were 15 health improvements analysed as dependent

variables.Patients who reported “yes” to noticing positive

changes since first being issued a Green Prescription were

then prompted to answer the follow-up item,“If yes,what

positive changes have you noticed?” There were originally 19

response options, but the options “feel stronger/fitter”,“gen-

erally feelbetter”,“more energy”,and/or “other” were ex-

cluded from analysisas theseoptionsdo not directly

associate with any one particular health problem. Descriptive

statistics of the 15 health improvements are listed in Table 4.

Analysis

A predictive analysis was conducted through multinomial

regression to interpret odds ratios (OR). A linear regression

was calculated to test the assumption ofmulticollinearity.

The minimum cut off for tolerance was set at 0.2 and the

maximum cut off for the variance inflation factor (VIF) was

5. All independent variables met these assumptions,with

tolerances ranging between .699 and .956 and VIF ranging

between 1.430 and 1.046.All other assumptions for multi-

nomial regression were met.Multinomial regressions were

conducted using the health behavior groups as the predic-

tors (physicalactivity,dietand physicalactivity and diet)

each compared to the control group (neither physical activ-

ity nor diet).Then,odds ratios (OR) were calculated with

95% confidence intervals.All multinomial regressions con-

trolled for sex and age groups (under 60, over 59).

Results

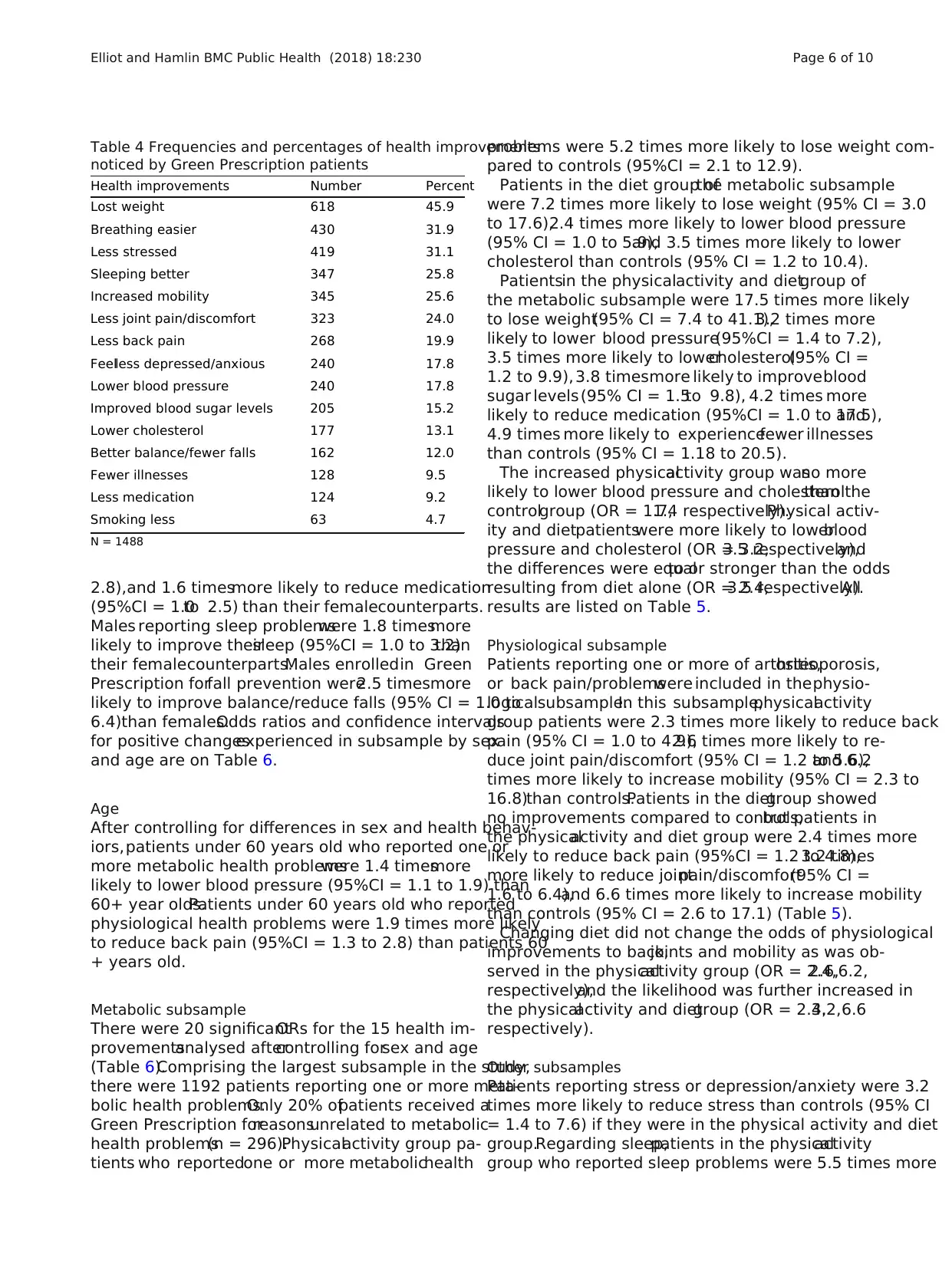

Overall,weightproblems were the mostcommonly re-

ported health problems (n = 886,60%),followed by high

blood pressure/risk ofstroke (n = 424,29%),arthritis

(n = 397,27%),and back pain/problems (n = 382,26%)

(Table 2).The most commonly reported health improve-

ments were weight loss (n = 618,46%),breathing easier

(n = 430,32%),and less stress (n = 419,31%) (Table 4).

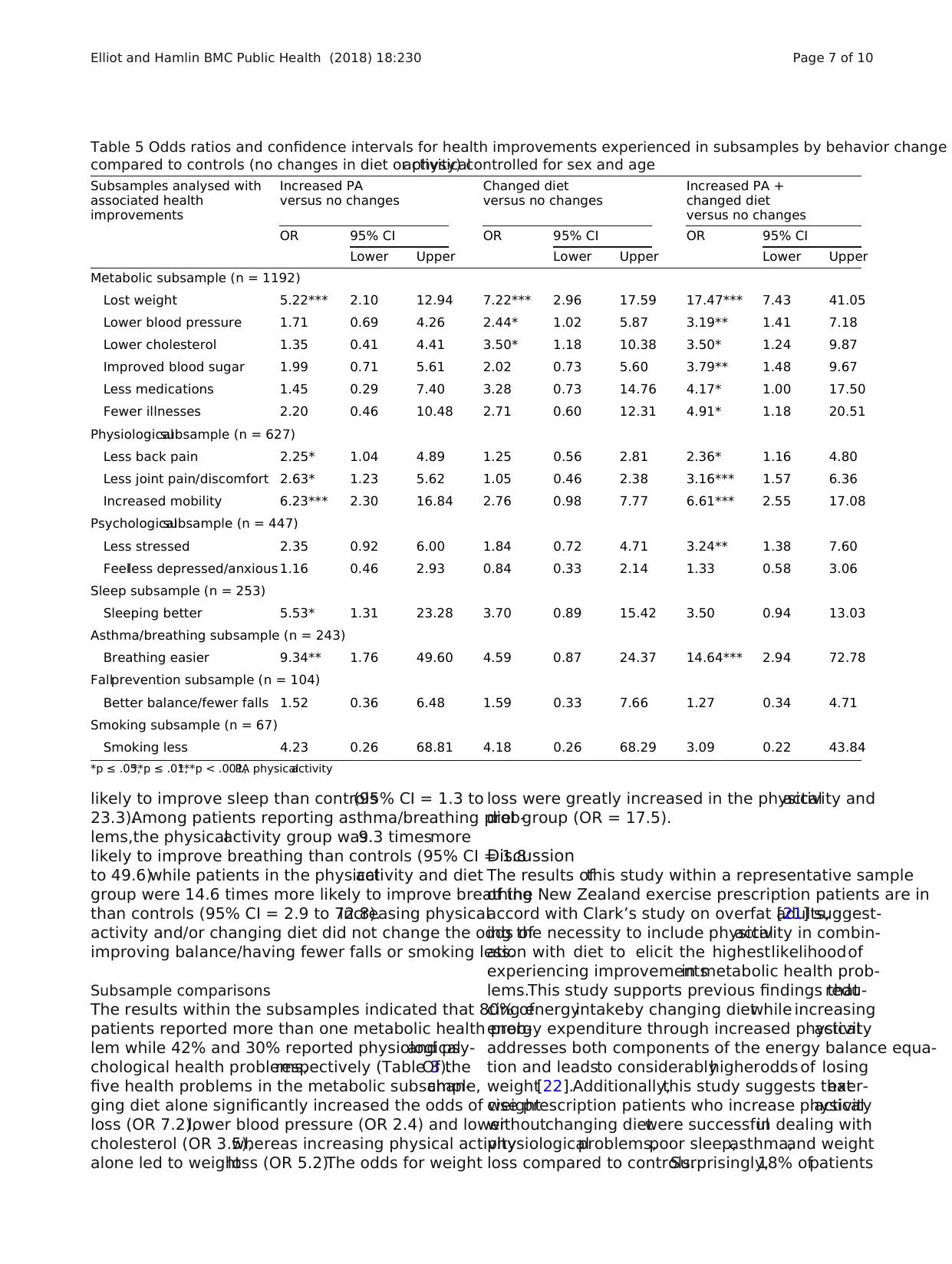

After controlling forsex and age,patientsin the diet

group were more likely to improve 3 ofthe 15 possible

health problems listed,and the physicalactivity group

improved 6 of15, but the physicalactivityand diet

group was more likely to improve 11 of 15 health prob-

lems compared to the control group (Table 5).

Sex

After controlling for differences in age and health behav-

ior, males who reported one or more metabolic health

problemswere2.0 timesmore likely to lower blood

pressure (95% CI = 1.4 to 2.7),1.8 times more likely to

lowercholesterol(95%CI = 1.3 to 2.6),2.0 timesmore

likely to improve blood sugarlevels(95% CI = 1.4 to

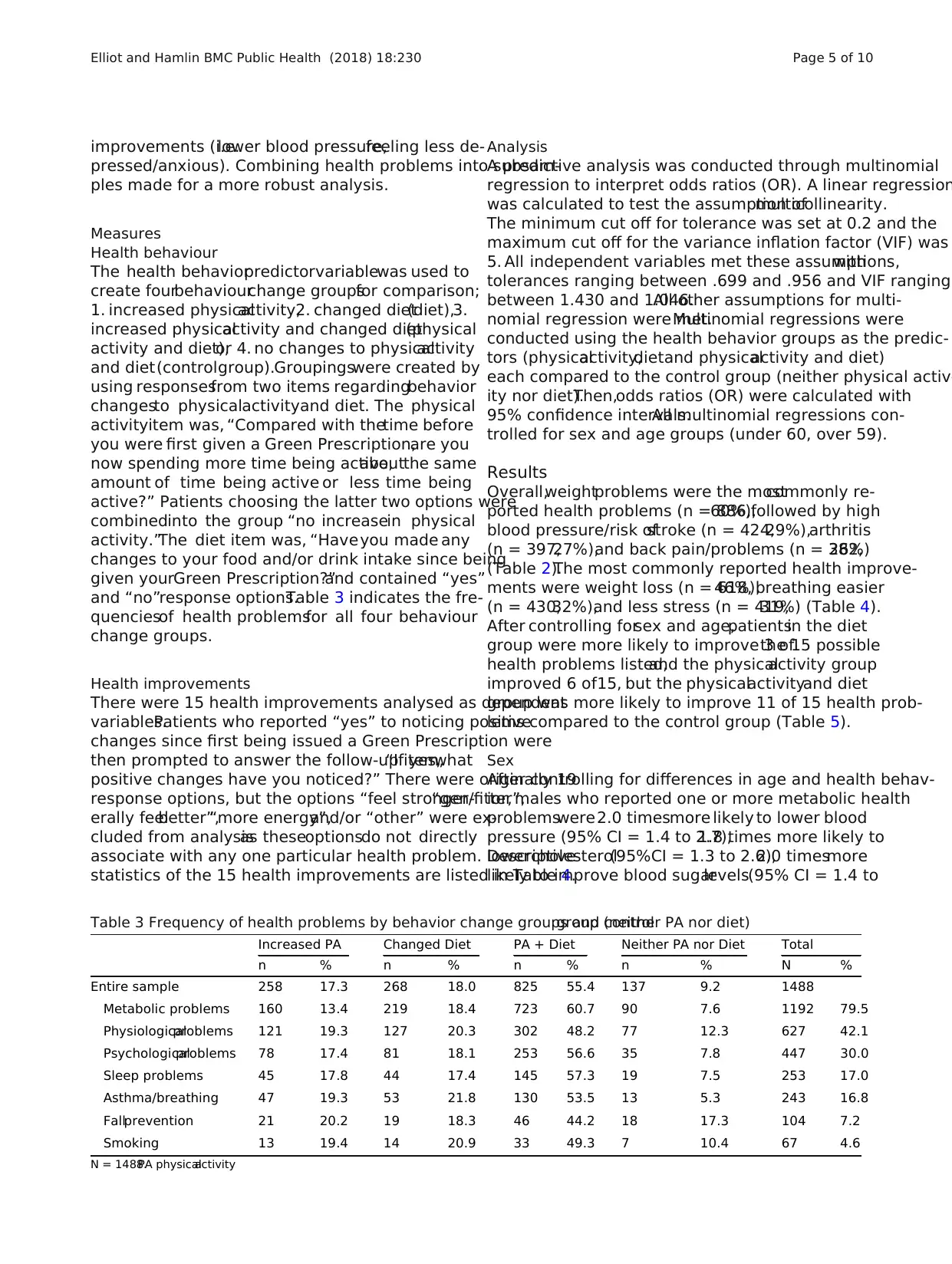

Table 3 Frequency of health problems by behavior change groups and controlgroup (neither PA nor diet)

Increased PA Changed Diet PA + Diet Neither PA nor Diet Total

n % n % n % n % N %

Entire sample 258 17.3 268 18.0 825 55.4 137 9.2 1488

Metabolic problems 160 13.4 219 18.4 723 60.7 90 7.6 1192 79.5

Physiologicalproblems 121 19.3 127 20.3 302 48.2 77 12.3 627 42.1

Psychologicalproblems 78 17.4 81 18.1 253 56.6 35 7.8 447 30.0

Sleep problems 45 17.8 44 17.4 145 57.3 19 7.5 253 17.0

Asthma/breathing 47 19.3 53 21.8 130 53.5 13 5.3 243 16.8

Fallprevention 21 20.2 19 18.3 46 44.2 18 17.3 104 7.2

Smoking 13 19.4 14 20.9 33 49.3 7 10.4 67 4.6

N = 1488.PA physicalactivity

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 5 of 10

pressed/anxious). Combining health problems into subsam-

ples made for a more robust analysis.

Measures

Health behaviour

The health behaviorpredictorvariablewas used to

create fourbehaviourchange groupsfor comparison;

1. increased physicalactivity,2. changed diet(diet),3.

increased physicalactivity and changed diet(physical

activity and diet),or 4. no changes to physicalactivity

and diet(controlgroup).Groupingswere created by

using responsesfrom two items regardingbehavior

changesto physicalactivityand diet. The physical

activityitem was, “Compared with thetime before

you were first given a Green Prescription,are you

now spending more time being active,aboutthe same

amount of time being active or less time being

active?” Patients choosing the latter two options were

combinedinto the group “no increasein physical

activity.”The diet item was, “Haveyou made any

changes to your food and/or drink intake since being

given yourGreen Prescription?”and contained “yes”

and “no”response options.Table 3 indicates the fre-

quenciesof health problemsfor all four behaviour

change groups.

Health improvements

There were 15 health improvements analysed as dependent

variables.Patients who reported “yes” to noticing positive

changes since first being issued a Green Prescription were

then prompted to answer the follow-up item,“If yes,what

positive changes have you noticed?” There were originally 19

response options, but the options “feel stronger/fitter”,“gen-

erally feelbetter”,“more energy”,and/or “other” were ex-

cluded from analysisas theseoptionsdo not directly

associate with any one particular health problem. Descriptive

statistics of the 15 health improvements are listed in Table 4.

Analysis

A predictive analysis was conducted through multinomial

regression to interpret odds ratios (OR). A linear regression

was calculated to test the assumption ofmulticollinearity.

The minimum cut off for tolerance was set at 0.2 and the

maximum cut off for the variance inflation factor (VIF) was

5. All independent variables met these assumptions,with

tolerances ranging between .699 and .956 and VIF ranging

between 1.430 and 1.046.All other assumptions for multi-

nomial regression were met.Multinomial regressions were

conducted using the health behavior groups as the predic-

tors (physicalactivity,dietand physicalactivity and diet)

each compared to the control group (neither physical activ-

ity nor diet).Then,odds ratios (OR) were calculated with

95% confidence intervals.All multinomial regressions con-

trolled for sex and age groups (under 60, over 59).

Results

Overall,weightproblems were the mostcommonly re-

ported health problems (n = 886,60%),followed by high

blood pressure/risk ofstroke (n = 424,29%),arthritis

(n = 397,27%),and back pain/problems (n = 382,26%)

(Table 2).The most commonly reported health improve-

ments were weight loss (n = 618,46%),breathing easier

(n = 430,32%),and less stress (n = 419,31%) (Table 4).

After controlling forsex and age,patientsin the diet

group were more likely to improve 3 ofthe 15 possible

health problems listed,and the physicalactivity group

improved 6 of15, but the physicalactivityand diet

group was more likely to improve 11 of 15 health prob-

lems compared to the control group (Table 5).

Sex

After controlling for differences in age and health behav-

ior, males who reported one or more metabolic health

problemswere2.0 timesmore likely to lower blood

pressure (95% CI = 1.4 to 2.7),1.8 times more likely to

lowercholesterol(95%CI = 1.3 to 2.6),2.0 timesmore

likely to improve blood sugarlevels(95% CI = 1.4 to

Table 3 Frequency of health problems by behavior change groups and controlgroup (neither PA nor diet)

Increased PA Changed Diet PA + Diet Neither PA nor Diet Total

n % n % n % n % N %

Entire sample 258 17.3 268 18.0 825 55.4 137 9.2 1488

Metabolic problems 160 13.4 219 18.4 723 60.7 90 7.6 1192 79.5

Physiologicalproblems 121 19.3 127 20.3 302 48.2 77 12.3 627 42.1

Psychologicalproblems 78 17.4 81 18.1 253 56.6 35 7.8 447 30.0

Sleep problems 45 17.8 44 17.4 145 57.3 19 7.5 253 17.0

Asthma/breathing 47 19.3 53 21.8 130 53.5 13 5.3 243 16.8

Fallprevention 21 20.2 19 18.3 46 44.2 18 17.3 104 7.2

Smoking 13 19.4 14 20.9 33 49.3 7 10.4 67 4.6

N = 1488.PA physicalactivity

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 5 of 10

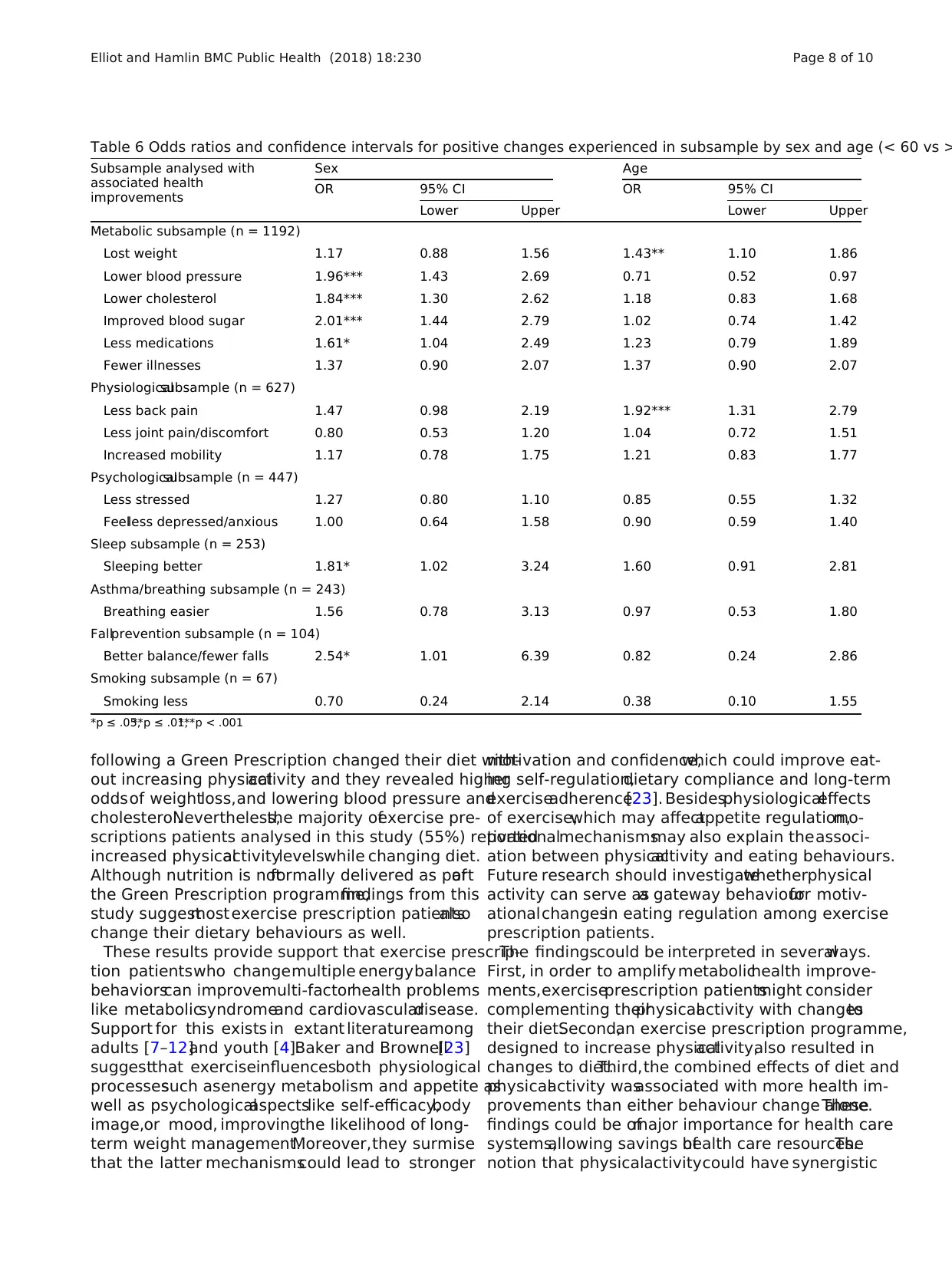

2.8),and 1.6 timesmore likely to reduce medication

(95%CI = 1.0to 2.5) than their femalecounterparts.

Males reporting sleep problemswere 1.8 timesmore

likely to improve theirsleep (95%CI = 1.0 to 3.2)than

their femalecounterparts.Males enrolledin Green

Prescription forfall prevention were2.5 timesmore

likely to improve balance/reduce falls (95% CI = 1.0 to

6.4)than females.Odds ratios and confidence intervals

for positive changesexperienced in subsample by sex

and age are on Table 6.

Age

After controlling for differences in sex and health behav-

iors,patients under 60 years old who reported one or

more metabolic health problemswere 1.4 timesmore

likely to lower blood pressure (95%CI = 1.1 to 1.9) than

60+ year olds.Patients under 60 years old who reported

physiological health problems were 1.9 times more likely

to reduce back pain (95%CI = 1.3 to 2.8) than patients 60

+ years old.

Metabolic subsample

There were 20 significantORs for the 15 health im-

provementsanalysed aftercontrolling forsex and age

(Table 6).Comprising the largest subsample in the study,

there were 1192 patients reporting one or more meta-

bolic health problems.Only 20% ofpatients received a

Green Prescription forreasonsunrelated to metabolic

health problems(n = 296).Physicalactivity group pa-

tients who reportedone or more metabolichealth

problems were 5.2 times more likely to lose weight com-

pared to controls (95%CI = 2.1 to 12.9).

Patients in the diet group ofthe metabolic subsample

were 7.2 times more likely to lose weight (95% CI = 3.0

to 17.6),2.4 times more likely to lower blood pressure

(95% CI = 1.0 to 5.9),and 3.5 times more likely to lower

cholesterol than controls (95% CI = 1.2 to 10.4).

Patientsin the physicalactivity and dietgroup of

the metabolic subsample were 17.5 times more likely

to lose weight(95% CI = 7.4 to 41.1),3.2 times more

likely to lower blood pressure(95%CI = 1.4 to 7.2),

3.5 times more likely to lowercholesterol(95% CI =

1.2 to 9.9), 3.8 timesmore likely to improveblood

sugar levels(95% CI = 1.5to 9.8), 4.2 times more

likely to reduce medication (95%CI = 1.0 to 17.5),and

4.9 times more likely to experiencefewer illnesses

than controls (95% CI = 1.18 to 20.5).

The increased physicalactivity group wasno more

likely to lower blood pressure and cholesterolthan the

controlgroup (OR = 1.7,1.4 respectively).Physical activ-

ity and dietpatientswere more likely to lowerblood

pressure and cholesterol (OR = 3.2,3.5 respectively),and

the differences were equalto or stronger than the odds

resulting from diet alone (OR = 2.4,3.5 respectively).All

results are listed on Table 5.

Physiological subsample

Patients reporting one or more of arthritis,osteoporosis,

or back pain/problemswere included in thephysio-

logicalsubsample.In this subsample,physicalactivity

group patients were 2.3 times more likely to reduce back

pain (95% CI = 1.0 to 4.9),2.6 times more likely to re-

duce joint pain/discomfort (95% CI = 1.2 to 5.6),and 6.2

times more likely to increase mobility (95% CI = 2.3 to

16.8)than controls.Patients in the dietgroup showed

no improvements compared to controls,but patients in

the physicalactivity and diet group were 2.4 times more

likely to reduce back pain (95%CI = 1.2 to 4.8),3.2 times

more likely to reduce jointpain/discomfort(95% CI =

1.6 to 6.4),and 6.6 times more likely to increase mobility

than controls (95% CI = 2.6 to 17.1) (Table 5).

Changing diet did not change the odds of physiological

improvements to back,joints and mobility as was ob-

served in the physicalactivity group (OR = 2.4,2.6,6.2,

respectively),and the likelihood was further increased in

the physicalactivity and dietgroup (OR = 2.4,3.2,6.6

respectively).

Other subsamples

Patients reporting stress or depression/anxiety were 3.2

times more likely to reduce stress than controls (95% CI

= 1.4 to 7.6) if they were in the physical activity and diet

group.Regarding sleep,patients in the physicalactivity

group who reported sleep problems were 5.5 times more

Table 4 Frequencies and percentages of health improvements

noticed by Green Prescription patients

Health improvements Number Percent

Lost weight 618 45.9

Breathing easier 430 31.9

Less stressed 419 31.1

Sleeping better 347 25.8

Increased mobility 345 25.6

Less joint pain/discomfort 323 24.0

Less back pain 268 19.9

Feelless depressed/anxious 240 17.8

Lower blood pressure 240 17.8

Improved blood sugar levels 205 15.2

Lower cholesterol 177 13.1

Better balance/fewer falls 162 12.0

Fewer illnesses 128 9.5

Less medication 124 9.2

Smoking less 63 4.7

N = 1488

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 6 of 10

(95%CI = 1.0to 2.5) than their femalecounterparts.

Males reporting sleep problemswere 1.8 timesmore

likely to improve theirsleep (95%CI = 1.0 to 3.2)than

their femalecounterparts.Males enrolledin Green

Prescription forfall prevention were2.5 timesmore

likely to improve balance/reduce falls (95% CI = 1.0 to

6.4)than females.Odds ratios and confidence intervals

for positive changesexperienced in subsample by sex

and age are on Table 6.

Age

After controlling for differences in sex and health behav-

iors,patients under 60 years old who reported one or

more metabolic health problemswere 1.4 timesmore

likely to lower blood pressure (95%CI = 1.1 to 1.9) than

60+ year olds.Patients under 60 years old who reported

physiological health problems were 1.9 times more likely

to reduce back pain (95%CI = 1.3 to 2.8) than patients 60

+ years old.

Metabolic subsample

There were 20 significantORs for the 15 health im-

provementsanalysed aftercontrolling forsex and age

(Table 6).Comprising the largest subsample in the study,

there were 1192 patients reporting one or more meta-

bolic health problems.Only 20% ofpatients received a

Green Prescription forreasonsunrelated to metabolic

health problems(n = 296).Physicalactivity group pa-

tients who reportedone or more metabolichealth

problems were 5.2 times more likely to lose weight com-

pared to controls (95%CI = 2.1 to 12.9).

Patients in the diet group ofthe metabolic subsample

were 7.2 times more likely to lose weight (95% CI = 3.0

to 17.6),2.4 times more likely to lower blood pressure

(95% CI = 1.0 to 5.9),and 3.5 times more likely to lower

cholesterol than controls (95% CI = 1.2 to 10.4).

Patientsin the physicalactivity and dietgroup of

the metabolic subsample were 17.5 times more likely

to lose weight(95% CI = 7.4 to 41.1),3.2 times more

likely to lower blood pressure(95%CI = 1.4 to 7.2),

3.5 times more likely to lowercholesterol(95% CI =

1.2 to 9.9), 3.8 timesmore likely to improveblood

sugar levels(95% CI = 1.5to 9.8), 4.2 times more

likely to reduce medication (95%CI = 1.0 to 17.5),and

4.9 times more likely to experiencefewer illnesses

than controls (95% CI = 1.18 to 20.5).

The increased physicalactivity group wasno more

likely to lower blood pressure and cholesterolthan the

controlgroup (OR = 1.7,1.4 respectively).Physical activ-

ity and dietpatientswere more likely to lowerblood

pressure and cholesterol (OR = 3.2,3.5 respectively),and

the differences were equalto or stronger than the odds

resulting from diet alone (OR = 2.4,3.5 respectively).All

results are listed on Table 5.

Physiological subsample

Patients reporting one or more of arthritis,osteoporosis,

or back pain/problemswere included in thephysio-

logicalsubsample.In this subsample,physicalactivity

group patients were 2.3 times more likely to reduce back

pain (95% CI = 1.0 to 4.9),2.6 times more likely to re-

duce joint pain/discomfort (95% CI = 1.2 to 5.6),and 6.2

times more likely to increase mobility (95% CI = 2.3 to

16.8)than controls.Patients in the dietgroup showed

no improvements compared to controls,but patients in

the physicalactivity and diet group were 2.4 times more

likely to reduce back pain (95%CI = 1.2 to 4.8),3.2 times

more likely to reduce jointpain/discomfort(95% CI =

1.6 to 6.4),and 6.6 times more likely to increase mobility

than controls (95% CI = 2.6 to 17.1) (Table 5).

Changing diet did not change the odds of physiological

improvements to back,joints and mobility as was ob-

served in the physicalactivity group (OR = 2.4,2.6,6.2,

respectively),and the likelihood was further increased in

the physicalactivity and dietgroup (OR = 2.4,3.2,6.6

respectively).

Other subsamples

Patients reporting stress or depression/anxiety were 3.2

times more likely to reduce stress than controls (95% CI

= 1.4 to 7.6) if they were in the physical activity and diet

group.Regarding sleep,patients in the physicalactivity

group who reported sleep problems were 5.5 times more

Table 4 Frequencies and percentages of health improvements

noticed by Green Prescription patients

Health improvements Number Percent

Lost weight 618 45.9

Breathing easier 430 31.9

Less stressed 419 31.1

Sleeping better 347 25.8

Increased mobility 345 25.6

Less joint pain/discomfort 323 24.0

Less back pain 268 19.9

Feelless depressed/anxious 240 17.8

Lower blood pressure 240 17.8

Improved blood sugar levels 205 15.2

Lower cholesterol 177 13.1

Better balance/fewer falls 162 12.0

Fewer illnesses 128 9.5

Less medication 124 9.2

Smoking less 63 4.7

N = 1488

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 6 of 10

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

likely to improve sleep than controls(95% CI = 1.3 to

23.3).Among patients reporting asthma/breathing prob-

lems,the physicalactivity group was9.3 timesmore

likely to improve breathing than controls (95% CI = 1.8

to 49.6)while patients in the physicalactivity and diet

group were 14.6 times more likely to improve breathing

than controls (95% CI = 2.9 to 72.8).Increasing physical

activity and/or changing diet did not change the odds of

improving balance/having fewer falls or smoking less.

Subsample comparisons

The results within the subsamples indicated that 80% of

patients reported more than one metabolic health prob-

lem while 42% and 30% reported physiologicaland psy-

chological health problems,respectively (Table 3).Of the

five health problems in the metabolic subsample,chan-

ging diet alone significantly increased the odds of weight

loss (OR 7.2),lower blood pressure (OR 2.4) and lower

cholesterol (OR 3.5),whereas increasing physical activity

alone led to weightloss (OR 5.2).The odds for weight

loss were greatly increased in the physicalactivity and

diet group (OR = 17.5).

Discussion

The results ofthis study within a representative sample

of the New Zealand exercise prescription patients are in

accord with Clark’s study on overfat adults,[21] suggest-

ing the necessity to include physicalactivity in combin-

ation with diet to elicit the highestlikelihoodof

experiencing improvementsin metabolic health prob-

lems.This study supports previous findings thatredu-

cing energyintakeby changing dietwhile increasing

energy expenditure through increased physicalactivity

addresses both components of the energy balance equa-

tion and leadsto considerablyhigherodds of losing

weight[22].Additionally,this study suggests thatexer-

cise prescription patients who increase physicalactivity

withoutchanging dietwere successfulin dealing with

physiologicalproblems,poor sleep,asthma,and weight

loss compared to controls.Surprisingly,18% ofpatients

Table 5 Odds ratios and confidence intervals for health improvements experienced in subsamples by behavior change

compared to controls (no changes in diet or physicalactivity) controlled for sex and age

Subsamples analysed with

associated health

improvements

Increased PA

versus no changes

Changed diet

versus no changes

Increased PA +

changed diet

versus no changes

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Lower Upper Lower Upper Lower Upper

Metabolic subsample (n = 1192)

Lost weight 5.22*** 2.10 12.94 7.22*** 2.96 17.59 17.47*** 7.43 41.05

Lower blood pressure 1.71 0.69 4.26 2.44* 1.02 5.87 3.19** 1.41 7.18

Lower cholesterol 1.35 0.41 4.41 3.50* 1.18 10.38 3.50* 1.24 9.87

Improved blood sugar 1.99 0.71 5.61 2.02 0.73 5.60 3.79** 1.48 9.67

Less medications 1.45 0.29 7.40 3.28 0.73 14.76 4.17* 1.00 17.50

Fewer illnesses 2.20 0.46 10.48 2.71 0.60 12.31 4.91* 1.18 20.51

Physiologicalsubsample (n = 627)

Less back pain 2.25* 1.04 4.89 1.25 0.56 2.81 2.36* 1.16 4.80

Less joint pain/discomfort 2.63* 1.23 5.62 1.05 0.46 2.38 3.16*** 1.57 6.36

Increased mobility 6.23*** 2.30 16.84 2.76 0.98 7.77 6.61*** 2.55 17.08

Psychologicalsubsample (n = 447)

Less stressed 2.35 0.92 6.00 1.84 0.72 4.71 3.24** 1.38 7.60

Feelless depressed/anxious 1.16 0.46 2.93 0.84 0.33 2.14 1.33 0.58 3.06

Sleep subsample (n = 253)

Sleeping better 5.53* 1.31 23.28 3.70 0.89 15.42 3.50 0.94 13.03

Asthma/breathing subsample (n = 243)

Breathing easier 9.34** 1.76 49.60 4.59 0.87 24.37 14.64*** 2.94 72.78

Fallprevention subsample (n = 104)

Better balance/fewer falls 1.52 0.36 6.48 1.59 0.33 7.66 1.27 0.34 4.71

Smoking subsample (n = 67)

Smoking less 4.23 0.26 68.81 4.18 0.26 68.29 3.09 0.22 43.84

*p ≤ .05,**p ≤ .01,***p < .001,PA physicalactivity

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 7 of 10

23.3).Among patients reporting asthma/breathing prob-

lems,the physicalactivity group was9.3 timesmore

likely to improve breathing than controls (95% CI = 1.8

to 49.6)while patients in the physicalactivity and diet

group were 14.6 times more likely to improve breathing

than controls (95% CI = 2.9 to 72.8).Increasing physical

activity and/or changing diet did not change the odds of

improving balance/having fewer falls or smoking less.

Subsample comparisons

The results within the subsamples indicated that 80% of

patients reported more than one metabolic health prob-

lem while 42% and 30% reported physiologicaland psy-

chological health problems,respectively (Table 3).Of the

five health problems in the metabolic subsample,chan-

ging diet alone significantly increased the odds of weight

loss (OR 7.2),lower blood pressure (OR 2.4) and lower

cholesterol (OR 3.5),whereas increasing physical activity

alone led to weightloss (OR 5.2).The odds for weight

loss were greatly increased in the physicalactivity and

diet group (OR = 17.5).

Discussion

The results ofthis study within a representative sample

of the New Zealand exercise prescription patients are in

accord with Clark’s study on overfat adults,[21] suggest-

ing the necessity to include physicalactivity in combin-

ation with diet to elicit the highestlikelihoodof

experiencing improvementsin metabolic health prob-

lems.This study supports previous findings thatredu-

cing energyintakeby changing dietwhile increasing

energy expenditure through increased physicalactivity

addresses both components of the energy balance equa-

tion and leadsto considerablyhigherodds of losing

weight[22].Additionally,this study suggests thatexer-

cise prescription patients who increase physicalactivity

withoutchanging dietwere successfulin dealing with

physiologicalproblems,poor sleep,asthma,and weight

loss compared to controls.Surprisingly,18% ofpatients

Table 5 Odds ratios and confidence intervals for health improvements experienced in subsamples by behavior change

compared to controls (no changes in diet or physicalactivity) controlled for sex and age

Subsamples analysed with

associated health

improvements

Increased PA

versus no changes

Changed diet

versus no changes

Increased PA +

changed diet

versus no changes

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Lower Upper Lower Upper Lower Upper

Metabolic subsample (n = 1192)

Lost weight 5.22*** 2.10 12.94 7.22*** 2.96 17.59 17.47*** 7.43 41.05

Lower blood pressure 1.71 0.69 4.26 2.44* 1.02 5.87 3.19** 1.41 7.18

Lower cholesterol 1.35 0.41 4.41 3.50* 1.18 10.38 3.50* 1.24 9.87

Improved blood sugar 1.99 0.71 5.61 2.02 0.73 5.60 3.79** 1.48 9.67

Less medications 1.45 0.29 7.40 3.28 0.73 14.76 4.17* 1.00 17.50

Fewer illnesses 2.20 0.46 10.48 2.71 0.60 12.31 4.91* 1.18 20.51

Physiologicalsubsample (n = 627)

Less back pain 2.25* 1.04 4.89 1.25 0.56 2.81 2.36* 1.16 4.80

Less joint pain/discomfort 2.63* 1.23 5.62 1.05 0.46 2.38 3.16*** 1.57 6.36

Increased mobility 6.23*** 2.30 16.84 2.76 0.98 7.77 6.61*** 2.55 17.08

Psychologicalsubsample (n = 447)

Less stressed 2.35 0.92 6.00 1.84 0.72 4.71 3.24** 1.38 7.60

Feelless depressed/anxious 1.16 0.46 2.93 0.84 0.33 2.14 1.33 0.58 3.06

Sleep subsample (n = 253)

Sleeping better 5.53* 1.31 23.28 3.70 0.89 15.42 3.50 0.94 13.03

Asthma/breathing subsample (n = 243)

Breathing easier 9.34** 1.76 49.60 4.59 0.87 24.37 14.64*** 2.94 72.78

Fallprevention subsample (n = 104)

Better balance/fewer falls 1.52 0.36 6.48 1.59 0.33 7.66 1.27 0.34 4.71

Smoking subsample (n = 67)

Smoking less 4.23 0.26 68.81 4.18 0.26 68.29 3.09 0.22 43.84

*p ≤ .05,**p ≤ .01,***p < .001,PA physicalactivity

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 7 of 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

following a Green Prescription changed their diet with-

out increasing physicalactivity and they revealed higher

oddsof weightloss,and lowering blood pressure and

cholesterol.Nevertheless,the majority ofexercise pre-

scriptions patients analysed in this study (55%) reported

increased physicalactivitylevelswhile changing diet.

Although nutrition is notformally delivered as partof

the Green Prescription programme,findings from this

study suggestmost exercise prescription patientsalso

change their dietary behaviours as well.

These results provide support that exercise prescrip-

tion patientswho changemultiple energybalance

behaviorscan improvemulti-factorhealth problems

like metabolicsyndromeand cardiovasculardisease.

Support for this exists in extant literatureamong

adults [7–12]and youth [4].Baker and Brownell[23]

suggestthat exerciseinfluencesboth physiological

processessuch asenergy metabolism and appetite as

well as psychologicalaspectslike self-efficacy,body

image,or mood, improvingthe likelihood of long-

term weight management.Moreover,they surmise

that the latter mechanismscould lead to stronger

motivation and confidence,which could improve eat-

ing self-regulation,dietary compliance and long-term

exerciseadherence[23]. Besidesphysiologicaleffects

of exercise,which may affectappetite regulation,mo-

tivationalmechanismsmay also explain theassoci-

ation between physicalactivity and eating behaviours.

Future research should investigatewhetherphysical

activity can serve asa gateway behaviourfor motiv-

ationalchangesin eating regulation among exercise

prescription patients.

The findingscould be interpreted in severalways.

First, in order to amplify metabolichealth improve-

ments,exerciseprescription patientsmight consider

complementing theirphysicalactivity with changesto

their diet.Second,an exercise prescription programme,

designed to increase physicalactivity,also resulted in

changes to diet.Third,the combined effects of diet and

physicalactivity wasassociated with more health im-

provements than either behaviour change alone.These

findings could be ofmajor importance for health care

systems,allowing savings ofhealth care resources.The

notion that physicalactivitycould have synergistic

Table 6 Odds ratios and confidence intervals for positive changes experienced in subsample by sex and age (< 60 vs >

Subsample analysed with

associated health

improvements

Sex Age

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Lower Upper Lower Upper

Metabolic subsample (n = 1192)

Lost weight 1.17 0.88 1.56 1.43** 1.10 1.86

Lower blood pressure 1.96*** 1.43 2.69 0.71 0.52 0.97

Lower cholesterol 1.84*** 1.30 2.62 1.18 0.83 1.68

Improved blood sugar 2.01*** 1.44 2.79 1.02 0.74 1.42

Less medications 1.61* 1.04 2.49 1.23 0.79 1.89

Fewer illnesses 1.37 0.90 2.07 1.37 0.90 2.07

Physiologicalsubsample (n = 627)

Less back pain 1.47 0.98 2.19 1.92*** 1.31 2.79

Less joint pain/discomfort 0.80 0.53 1.20 1.04 0.72 1.51

Increased mobility 1.17 0.78 1.75 1.21 0.83 1.77

Psychologicalsubsample (n = 447)

Less stressed 1.27 0.80 1.10 0.85 0.55 1.32

Feelless depressed/anxious 1.00 0.64 1.58 0.90 0.59 1.40

Sleep subsample (n = 253)

Sleeping better 1.81* 1.02 3.24 1.60 0.91 2.81

Asthma/breathing subsample (n = 243)

Breathing easier 1.56 0.78 3.13 0.97 0.53 1.80

Fallprevention subsample (n = 104)

Better balance/fewer falls 2.54* 1.01 6.39 0.82 0.24 2.86

Smoking subsample (n = 67)

Smoking less 0.70 0.24 2.14 0.38 0.10 1.55

*p ≤ .05,**p ≤ .01,***p < .001

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 8 of 10

out increasing physicalactivity and they revealed higher

oddsof weightloss,and lowering blood pressure and

cholesterol.Nevertheless,the majority ofexercise pre-

scriptions patients analysed in this study (55%) reported

increased physicalactivitylevelswhile changing diet.

Although nutrition is notformally delivered as partof

the Green Prescription programme,findings from this

study suggestmost exercise prescription patientsalso

change their dietary behaviours as well.

These results provide support that exercise prescrip-

tion patientswho changemultiple energybalance

behaviorscan improvemulti-factorhealth problems

like metabolicsyndromeand cardiovasculardisease.

Support for this exists in extant literatureamong

adults [7–12]and youth [4].Baker and Brownell[23]

suggestthat exerciseinfluencesboth physiological

processessuch asenergy metabolism and appetite as

well as psychologicalaspectslike self-efficacy,body

image,or mood, improvingthe likelihood of long-

term weight management.Moreover,they surmise

that the latter mechanismscould lead to stronger

motivation and confidence,which could improve eat-

ing self-regulation,dietary compliance and long-term

exerciseadherence[23]. Besidesphysiologicaleffects

of exercise,which may affectappetite regulation,mo-

tivationalmechanismsmay also explain theassoci-

ation between physicalactivity and eating behaviours.

Future research should investigatewhetherphysical

activity can serve asa gateway behaviourfor motiv-

ationalchangesin eating regulation among exercise

prescription patients.

The findingscould be interpreted in severalways.

First, in order to amplify metabolichealth improve-

ments,exerciseprescription patientsmight consider

complementing theirphysicalactivity with changesto

their diet.Second,an exercise prescription programme,

designed to increase physicalactivity,also resulted in

changes to diet.Third,the combined effects of diet and

physicalactivity wasassociated with more health im-

provements than either behaviour change alone.These

findings could be ofmajor importance for health care

systems,allowing savings ofhealth care resources.The

notion that physicalactivitycould have synergistic

Table 6 Odds ratios and confidence intervals for positive changes experienced in subsample by sex and age (< 60 vs >

Subsample analysed with

associated health

improvements

Sex Age

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Lower Upper Lower Upper

Metabolic subsample (n = 1192)

Lost weight 1.17 0.88 1.56 1.43** 1.10 1.86

Lower blood pressure 1.96*** 1.43 2.69 0.71 0.52 0.97

Lower cholesterol 1.84*** 1.30 2.62 1.18 0.83 1.68

Improved blood sugar 2.01*** 1.44 2.79 1.02 0.74 1.42

Less medications 1.61* 1.04 2.49 1.23 0.79 1.89

Fewer illnesses 1.37 0.90 2.07 1.37 0.90 2.07

Physiologicalsubsample (n = 627)

Less back pain 1.47 0.98 2.19 1.92*** 1.31 2.79

Less joint pain/discomfort 0.80 0.53 1.20 1.04 0.72 1.51

Increased mobility 1.17 0.78 1.75 1.21 0.83 1.77

Psychologicalsubsample (n = 447)

Less stressed 1.27 0.80 1.10 0.85 0.55 1.32

Feelless depressed/anxious 1.00 0.64 1.58 0.90 0.59 1.40

Sleep subsample (n = 253)

Sleeping better 1.81* 1.02 3.24 1.60 0.91 2.81

Asthma/breathing subsample (n = 243)

Breathing easier 1.56 0.78 3.13 0.97 0.53 1.80

Fallprevention subsample (n = 104)

Better balance/fewer falls 2.54* 1.01 6.39 0.82 0.24 2.86

Smoking subsample (n = 67)

Smoking less 0.70 0.24 2.14 0.38 0.10 1.55

*p ≤ .05,**p ≤ .01,***p < .001

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 8 of 10

effects in changing eating behaviors is a very powerful

one,given the combined benefits found for several meta-

bolic health indicators and the high incidence ofthose

indicators in today’s society.

Although Green Prescription currently offers healthy

eating information and tips to patients,some contract

holdersmight offer a more specialised servicewith

registered dieticians.Green Prescription,and possibly

other exerciseprescription programmes,might con-

sider provisionsfor a nutritionalcomponentsuch as

consultationswith a registered dietitian.Understanding

healthy eating and improving one’s dietwould be well-

suited for patientswith metabolichealth problems.

Considering the evidence in this research and given that

the majority of patients who follow the Green Prescription

programme in this study (80%) were prescribed exercise for

at least one metabolic health problem,Green Prescription

funders should consider strengthening the dietary compo-

nent ofthe programme,especially considering the strong

association between diet and metabolism.

Limitations

There were severallimitations in this study.First,creat-

ing subsamples with four behavior groups each made for

smallergroup comparisonswith less power.For ex-

ample,no health behavior changes improved the odds of

reporting betterbalance orlesssmoking compared to

controls.This resultcould be due reduced numbers in

each health behavior group or due to irrelevant associa-

tions from physicalactivity and/or dietfor such health

improvements.The subsamples were created to address

the smaller group sizes.Second,self-reportsurveys are

subject to misreporting and are not objective measures.

Moreover,the item with the lost weight response option

did not account for body composition.Third,the types

of physicalactivity and dietary changes were not speci-

fied in the survey,i.e.endurance versus resistance train-

ing. Fourth, only 28% of the invited participants

completed the survey.It is possible thatthese respon-

dents were the most motivated and successfulones,po-

tentially explaining the high rates ofpatients reporting

changes to physical activity and diet.Fifth,a social desir-

ability bias could have been present due to nature of the

data collection and thiscould have been amplified by

the fact that people received financialincentives to par-

ticipate ($250 gift vouchers).Sixth,the vague nature of

the questionsused to assessphysicalactivity and diet

changes (“are you now spending more time being active?”

and “Have you made any changes to your food and/or

drink intake?”) impose the assumption that respondents

have the same notion ofwhat “more active” means and

it is possible thatrespondents’food and drink intake

changed to became less healthy.Future Green Prescrip-

tion surveys should improve these questions to quantify

the responses in a clearer and more subjective manner.

Finally,although the analyses controlled for the covari-

atessex and age,one cannotignore the existence of

other residual confounders.

Conclusion

Exerciseprescriptionpatients who made behavior

changesto diet and physicalactivitygained greater

health improvements than those who changed only one

behaviour.This suggeststhat undertaking two energy

balance behavior changes within an exercise prescription

programmecan improvethe likelihood of achieving

health improvements.This study supportsexisting

evidence [16] that changing one’s health status requires

a manipulation ofan elaborate network ofinteracting,

complimenting,and confoundingfactors.Adding a

nutrition componentto physicalactivityprescription

programmes may increase the potentialfor patients to

experienceimprovementsin metabolic,physicaland

psychologicalhealth, potentiallyenabling them to

reverse the deleterious co-morbidities they are at risk of

experiencing otherwise. Exercise prescription programmes

would become more robust and can be further persona-

lised in their delivery approach if dietary counselling is in-

cluded as part of usual care.Further studies are needed to

determine the impact and economic viability of incorpor-

ating a nutritionalcomponentto exercise prescription

programmes [16].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Verena Hammes for her technical

help,writing assistance and generalsupport.The authors would also like to

acknowledge New Zealand Ministry of Health and Research New Zealand for

their generosity in providing the data for this study.

Funding

The authors declare that they received no funding in the design of the study

and collection,analysis,and interpretation of data and in writing the

manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data thatsupportthe findings ofthis study are available from the

New Zealand Ministry ofHealth butrestrictions apply to the availability

of these data,which were used underlicense forthe currentstudy,and

so are notpublicly available.Data are howeveravailable from Research

New Zealand upon reasonable requestand with permission ofNew

Zealand Ministry ofHealth.

Authors’contributions

CE has made substantialcontributions to conception and design,acquisition

of data,and data analysis,drafting of the manuscript and criticalrevision for

intellectualcontent.

MH has made substantialcontributions to conception and design,data

analysis,drafting of the manuscript and criticalrevision for intellectual

content.Both authors read and approved the finalmanuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our analysis did not report on primary research,rather,it retrospectively

analysed outcomes from a sample of those enrolled in Green Prescription.

The need for ethicalapprovalwas waived by the Health and Disability Ethics

Committees in New Zealand as it was considered out of scope.

Elliot and Hamlin BMC Public Health (2018) 18:230 Page 9 of 10

one,given the combined benefits found for several meta-

bolic health indicators and the high incidence ofthose

indicators in today’s society.

Although Green Prescription currently offers healthy

eating information and tips to patients,some contract

holdersmight offer a more specialised servicewith

registered dieticians.Green Prescription,and possibly

other exerciseprescription programmes,might con-

sider provisionsfor a nutritionalcomponentsuch as

consultationswith a registered dietitian.Understanding

healthy eating and improving one’s dietwould be well-

suited for patientswith metabolichealth problems.