Pride or Embarrassment? Employees' Emotions and Corporate Social Responsibility

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|30

|11652

|362

AI Summary

This study explores how the employees of a financial firm use emotional arguments to construct different views of their employer’s corporate social responsibility. The study identifies six categories of emotional arguments the employees used to construct views of where their employing organization’s CSR is derived from.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

This is an electronic reprint of the original article.

This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail.

Author(s):

Title:

Year:

Version:

Please cite the original version:

All material supplied via JYX is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and

duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that

material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or

print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be

offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user.

Pride or Embarrassment? Employees' Emotions and Corporate Social Responsibility

Onkila, Tiina

Onkila, T. (2015). Pride or Embarrassment? Employees' Emotions and Corporate

Social Responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental

Management, 22 (4), 222-236. doi:10.1002/csr.1340

2015

Final Draft

This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail.

Author(s):

Title:

Year:

Version:

Please cite the original version:

All material supplied via JYX is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and

duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that

material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or

print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be

offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user.

Pride or Embarrassment? Employees' Emotions and Corporate Social Responsibility

Onkila, Tiina

Onkila, T. (2015). Pride or Embarrassment? Employees' Emotions and Corporate

Social Responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental

Management, 22 (4), 222-236. doi:10.1002/csr.1340

2015

Final Draft

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Pride or Embarrassment?

Employees’ emotions and corporate social responsibility

Abstract

This study explores how the employees of a financial firm use emotional arguments to

construct different views of their employer’s corporate social responsibility. It is

theoretically based on the recent literature regarding employee perspectives of CSR,

and especially on the role of emotions in CSR. Furthermore, the study utilizes

rhetorical theory as a framework for data analysis. A qualitative study, based on face-

to-face interviews, was conducted among 27 employees in a Finnish financial firm.

The study identifies six categories of emotional arguments the employees used to

construct views of where their employing organization’s CSR is derived from. These

categories relate positive emotions to satisfaction with the employing organization’s

CSR and negative emotions to dissatisfaction. The results show that employees also

experience external pressures for CSR, but only implicitly, because they do not wish

be embarrassed by their employer.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility, employees, rhetoric, emotions, financing

firm

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is usually conceptualized through different

stakeholder groups and their importance to and demands on CSR. The discussion has

recently been extended to the importance of employees—not simply as demanders of

responsibility in issues such as responsible HRM practices (Celma et al., 2012) but as

participating in or initiating, for instance, donations (Haski-Leventhal, 2012). However,

the role of employees in how CSR is perceived is under-researched and the literature

Employees’ emotions and corporate social responsibility

Abstract

This study explores how the employees of a financial firm use emotional arguments to

construct different views of their employer’s corporate social responsibility. It is

theoretically based on the recent literature regarding employee perspectives of CSR,

and especially on the role of emotions in CSR. Furthermore, the study utilizes

rhetorical theory as a framework for data analysis. A qualitative study, based on face-

to-face interviews, was conducted among 27 employees in a Finnish financial firm.

The study identifies six categories of emotional arguments the employees used to

construct views of where their employing organization’s CSR is derived from. These

categories relate positive emotions to satisfaction with the employing organization’s

CSR and negative emotions to dissatisfaction. The results show that employees also

experience external pressures for CSR, but only implicitly, because they do not wish

be embarrassed by their employer.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility, employees, rhetoric, emotions, financing

firm

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is usually conceptualized through different

stakeholder groups and their importance to and demands on CSR. The discussion has

recently been extended to the importance of employees—not simply as demanders of

responsibility in issues such as responsible HRM practices (Celma et al., 2012) but as

participating in or initiating, for instance, donations (Haski-Leventhal, 2012). However,

the role of employees in how CSR is perceived is under-researched and the literature

argues for more research on the employees in addressing responsibility in business

(Russell and Griffiths, 2008).

Prior research on environmental responsibilities in business has highlighted the

importance of emotions to responsibility. Russell and Griffiths (2008, p.85) stated:

While environmental management research does mention emotive components of pro-

environmental behavior (Andersson and Bateman, 2000; Bansal and Roth, 2000; Ramus

and Steger , 2000), there are very few studies that examine emotion directly.

The importance of emotions was further stressed by Fineman (1996a, p.480):

I wish to argue that pro-environmental organizational changes, like other organizational

changes, depend crucially on the emotional meanings that key actors attribute to

environmental protection.

However, one finds surprisingly little data on the emotions employees relate to CSR

and their consequences for its different meanings. As Russell and Griffiths (2008) point

out, while environmental management research has mentioned the emotive

components of pro-environmental behavior, there are few studies that examine

emotions directly. From an environmental responsibility point of view, these include

Fineman’s (1996a) and Fineman and Sturdy’s (1999) work, whereas solely from a

CSR point of view emotions remain unstudied. Still, emotions explicitly brought up by

the interviewees were a striking feature in my interviewee material concerning

corporate social responsibility and information dissemination in a financial firm.

Prior research on employee roles in CSR has especially maintained employees as a

coherent, unified group that demands CSR among other stakeholders (Jamali, 2008;

Longo et al., 2005; Royle, 2005; Preuss et al., 2009; McWilliams and Siegel, 2001).

In addition, the studies on cultural changes in regards to CSR have aimed at creating

such a coherent group by managerial action (Halme, 2002; Siebenhuner and Arnold,

2007; Haugh and Talwar, 2010; Benn and Martin, 2010; Del Brio et al., 2008). Thus

the research has focused on asking what the employee demands are on CSR among

other stakeholders and how management can motivate employees to participate in

CSR. However, a few studies have embraced the different meanings that employees

attach to CSR. For instance, Rupp et al. (2006) stressed employees’ different

judgments of their employing organization’s CSR. Still, little is known about the

employees’ judgments of how their employing organization’s CSR is defined and the

emotions related to those judgments.

(Russell and Griffiths, 2008).

Prior research on environmental responsibilities in business has highlighted the

importance of emotions to responsibility. Russell and Griffiths (2008, p.85) stated:

While environmental management research does mention emotive components of pro-

environmental behavior (Andersson and Bateman, 2000; Bansal and Roth, 2000; Ramus

and Steger , 2000), there are very few studies that examine emotion directly.

The importance of emotions was further stressed by Fineman (1996a, p.480):

I wish to argue that pro-environmental organizational changes, like other organizational

changes, depend crucially on the emotional meanings that key actors attribute to

environmental protection.

However, one finds surprisingly little data on the emotions employees relate to CSR

and their consequences for its different meanings. As Russell and Griffiths (2008) point

out, while environmental management research has mentioned the emotive

components of pro-environmental behavior, there are few studies that examine

emotions directly. From an environmental responsibility point of view, these include

Fineman’s (1996a) and Fineman and Sturdy’s (1999) work, whereas solely from a

CSR point of view emotions remain unstudied. Still, emotions explicitly brought up by

the interviewees were a striking feature in my interviewee material concerning

corporate social responsibility and information dissemination in a financial firm.

Prior research on employee roles in CSR has especially maintained employees as a

coherent, unified group that demands CSR among other stakeholders (Jamali, 2008;

Longo et al., 2005; Royle, 2005; Preuss et al., 2009; McWilliams and Siegel, 2001).

In addition, the studies on cultural changes in regards to CSR have aimed at creating

such a coherent group by managerial action (Halme, 2002; Siebenhuner and Arnold,

2007; Haugh and Talwar, 2010; Benn and Martin, 2010; Del Brio et al., 2008). Thus

the research has focused on asking what the employee demands are on CSR among

other stakeholders and how management can motivate employees to participate in

CSR. However, a few studies have embraced the different meanings that employees

attach to CSR. For instance, Rupp et al. (2006) stressed employees’ different

judgments of their employing organization’s CSR. Still, little is known about the

employees’ judgments of how their employing organization’s CSR is defined and the

emotions related to those judgments.

This encouraged me to conduct a rhetorically oriented study on explicit emotions

expressed by employees while talking about their employing organization CSR. The

study asks how employees of a Finnish financial firm use explicitly emotional

arguments to construct different views of corporate social responsibility. The study

shows that employees use emotional arguments to construct distinct views of where

their employing organization’s CSR is derived from, relating positive emotions to

satisfaction with CSR and negative emotions to shortcomings in the employing

organization’s CSR.

I first review the previous research on CSR, emotions and employees and show its

implications for this study. Second, I present the rhetorical approach of the study as

well as the research context, material and methods. Finally, I explain the empirical

results of the study and discuss the contribution of the study.

Corporate Social Responsibility, Emotions and Employees

Multiple Meanings of CSR

The first definitions of corporate social responsibility date back to the 1950s. During

this era it held different meanings (Carroll, 1999), from Friedman’s (1970)

argumentation of profit maximization to more modern definitions encompassing

different pillars or dimensions of CSR (Carroll, 1993; Wood, 1991; Elkington, 1997).

Although Carroll’s work (1993) and Elkington’s (1997) triple bottom line are commonly

accepted as starting points for a definition of CSR, still many researchers and

practitioners contest the term’s meaning. For example, Dahlsrud (2008) found 37

definitions for CSR. He concluded that the existing definitions are, to a large degree,

congruent and refer to five dimensions: stakeholder, social, economic, voluntariness

and environmental. He explains that the confusion is not so much about how CSR is

defined, but about how CSR is socially constructed in a specific context. Although

there is some agreement on what types of issues can be included in CSR on the

macro-level, we still know little of the meanings related to CSR in different micro-

contexts by different actors. In different contexts CSR can be a contested and disputed

expressed by employees while talking about their employing organization CSR. The

study asks how employees of a Finnish financial firm use explicitly emotional

arguments to construct different views of corporate social responsibility. The study

shows that employees use emotional arguments to construct distinct views of where

their employing organization’s CSR is derived from, relating positive emotions to

satisfaction with CSR and negative emotions to shortcomings in the employing

organization’s CSR.

I first review the previous research on CSR, emotions and employees and show its

implications for this study. Second, I present the rhetorical approach of the study as

well as the research context, material and methods. Finally, I explain the empirical

results of the study and discuss the contribution of the study.

Corporate Social Responsibility, Emotions and Employees

Multiple Meanings of CSR

The first definitions of corporate social responsibility date back to the 1950s. During

this era it held different meanings (Carroll, 1999), from Friedman’s (1970)

argumentation of profit maximization to more modern definitions encompassing

different pillars or dimensions of CSR (Carroll, 1993; Wood, 1991; Elkington, 1997).

Although Carroll’s work (1993) and Elkington’s (1997) triple bottom line are commonly

accepted as starting points for a definition of CSR, still many researchers and

practitioners contest the term’s meaning. For example, Dahlsrud (2008) found 37

definitions for CSR. He concluded that the existing definitions are, to a large degree,

congruent and refer to five dimensions: stakeholder, social, economic, voluntariness

and environmental. He explains that the confusion is not so much about how CSR is

defined, but about how CSR is socially constructed in a specific context. Although

there is some agreement on what types of issues can be included in CSR on the

macro-level, we still know little of the meanings related to CSR in different micro-

contexts by different actors. In different contexts CSR can be a contested and disputed

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

phenomenon (Dobers, 2009). Contextual factors influence the perceptions and

definitions of CSR. This means the current CSR concepts still suffer from a level of

abstraction to which Jamali (2008) offers the stakeholder approach as a practical

alternative. This approach, too, however, provides few tools for analyzing different

meanings of the concept.

Employees’ Importance to CSR

Despite the discussion of the different meanings of CSR, the mainstream literature

stresses employees as a unified group and the importance of shared responsibility. A

number of streams of research point out that employees, among other stakeholders,

demand CSR and note their crucial role in the internal organizational changes for

achieving CSR.

First, the stakeholder perspective places employees among key stakeholders concerning

CSR (Carroll, 1999; Jamali, 2008; Longo et al., 2005; Royle, 2005; Preuss et al., 2009;

McWilliams and Siegel, 2001). Among other stakeholders, they are pushing

organizations towards responsible behavior (Aguilera et al., 2007; Williams and Siegel,

2001). Williams and Siegel (2001) identified two major sources of demand for CSR:

consumer demand and demand from other stakeholders such as investors, employees

and the community. They especially identified the influence of unions, and interest in

labor relation policies, safety and financial security. Furthermore, Henriques and

Sadorsky (1999) identified four groups that demand firms to protect the natural

environment: regulatory stakeholders (government and trade associations),

organizational stakeholders (customers, suppliers, employees and shareholders),

community stakeholders (community groups and environmental organizations) and the

media. Sharma and Henriques (2005) examined how managers’ perceptions of different

types of stakeholder influences affect the types of sustainability practices that firms

adopt. A multiplicity of withholding influences (by regulators, environmental NGOs),

usage influences (by customers) and employee influences (through involvement) were

identified by managers. Preuss et al. (2009) found especially employee representatives

and trade unions as important demanders. Spence (2009) identified investors and

employees as being overwhelmingly the most important audiences targeted by social

and environmental reporting managers. Huang and Kung (2010) identified three groups

definitions of CSR. This means the current CSR concepts still suffer from a level of

abstraction to which Jamali (2008) offers the stakeholder approach as a practical

alternative. This approach, too, however, provides few tools for analyzing different

meanings of the concept.

Employees’ Importance to CSR

Despite the discussion of the different meanings of CSR, the mainstream literature

stresses employees as a unified group and the importance of shared responsibility. A

number of streams of research point out that employees, among other stakeholders,

demand CSR and note their crucial role in the internal organizational changes for

achieving CSR.

First, the stakeholder perspective places employees among key stakeholders concerning

CSR (Carroll, 1999; Jamali, 2008; Longo et al., 2005; Royle, 2005; Preuss et al., 2009;

McWilliams and Siegel, 2001). Among other stakeholders, they are pushing

organizations towards responsible behavior (Aguilera et al., 2007; Williams and Siegel,

2001). Williams and Siegel (2001) identified two major sources of demand for CSR:

consumer demand and demand from other stakeholders such as investors, employees

and the community. They especially identified the influence of unions, and interest in

labor relation policies, safety and financial security. Furthermore, Henriques and

Sadorsky (1999) identified four groups that demand firms to protect the natural

environment: regulatory stakeholders (government and trade associations),

organizational stakeholders (customers, suppliers, employees and shareholders),

community stakeholders (community groups and environmental organizations) and the

media. Sharma and Henriques (2005) examined how managers’ perceptions of different

types of stakeholder influences affect the types of sustainability practices that firms

adopt. A multiplicity of withholding influences (by regulators, environmental NGOs),

usage influences (by customers) and employee influences (through involvement) were

identified by managers. Preuss et al. (2009) found especially employee representatives

and trade unions as important demanders. Spence (2009) identified investors and

employees as being overwhelmingly the most important audiences targeted by social

and environmental reporting managers. Huang and Kung (2010) identified three groups

of stakeholders that greatly influence managerial choices regarding environmental

disclosure strategies: external stakeholders (government, debtors, consumers), internal

stakeholders (shareholders, employees) and intermediate stakeholders (environmental

NGOs and accounting firms). Furthermore, employee demands are not related only to

general CSR, but to environmental issues in particular. For instance Marshall et al. (2005)

found employee welfare to be an important driver for proactive environmental behavior

in the US wine industry. This approach assumes employees as a coherent and collective

group of individuals who unanimously demand responsible action from management.

Another main stream of research connects employees to internal organizational changes

to promote responsibility. This discussion has focused especially on the question of

developing a strongly integrative responsibility-oriented organizational culture (Dodge,

1997; Del Brio et al, 2008). The process of developing such a culture has mainly been

viewed through the concepts of sustainability and environmentalism as a collective

learning process (Halme, 1997; Halme, 2002; Siebenhuner and Arnold, 2007; Haugh and

Talwar, 2010; Benn and Martin, 2010; Del Brio et al., 2008) with the aim of creating a

holistic, shared understanding of responsibility in an organization. Furthermore, the

influence of managerial behavior on responsibility challenges has been identified as

being crucial in engaging employees to tackle the problems (Wolf, 2012; Ramus, 2002;

Baumgartner, 2009). The findings of Aragon-Correa et al. (2004) and Robertson and

Barling (2012) support the central role of executives in the so-called greening of an

organization. Ramus (2002) further emphasizes the importance of managerial tools

(education, participative communication and rewarding for sustainability) for such

change: supervisory behavior can positively affect employees’ environmental actions and

initiatives. Collier and Esteban (2007) focus on effective delivery of CSR practices—and

state that only the employees “whose value and vision are fully aligned with those of the

organization will handle these situations effectively” (p. 30). They conclude that it is

necessary for ethics and responsibility to become embedded in the culture of the

organization. They further point out that corporations have developed a range of CSR

practices, like such as codes of conduct, which seek to regulate the behavior of

employees. Marshall et al. (2005) follow the main stream as they stress the need for

infusing strong environmental values among employees throughout the company.

Zwetsloot (2003) highlight the importance of continuous learning related to management

system development in regards to CSR.

disclosure strategies: external stakeholders (government, debtors, consumers), internal

stakeholders (shareholders, employees) and intermediate stakeholders (environmental

NGOs and accounting firms). Furthermore, employee demands are not related only to

general CSR, but to environmental issues in particular. For instance Marshall et al. (2005)

found employee welfare to be an important driver for proactive environmental behavior

in the US wine industry. This approach assumes employees as a coherent and collective

group of individuals who unanimously demand responsible action from management.

Another main stream of research connects employees to internal organizational changes

to promote responsibility. This discussion has focused especially on the question of

developing a strongly integrative responsibility-oriented organizational culture (Dodge,

1997; Del Brio et al, 2008). The process of developing such a culture has mainly been

viewed through the concepts of sustainability and environmentalism as a collective

learning process (Halme, 1997; Halme, 2002; Siebenhuner and Arnold, 2007; Haugh and

Talwar, 2010; Benn and Martin, 2010; Del Brio et al., 2008) with the aim of creating a

holistic, shared understanding of responsibility in an organization. Furthermore, the

influence of managerial behavior on responsibility challenges has been identified as

being crucial in engaging employees to tackle the problems (Wolf, 2012; Ramus, 2002;

Baumgartner, 2009). The findings of Aragon-Correa et al. (2004) and Robertson and

Barling (2012) support the central role of executives in the so-called greening of an

organization. Ramus (2002) further emphasizes the importance of managerial tools

(education, participative communication and rewarding for sustainability) for such

change: supervisory behavior can positively affect employees’ environmental actions and

initiatives. Collier and Esteban (2007) focus on effective delivery of CSR practices—and

state that only the employees “whose value and vision are fully aligned with those of the

organization will handle these situations effectively” (p. 30). They conclude that it is

necessary for ethics and responsibility to become embedded in the culture of the

organization. They further point out that corporations have developed a range of CSR

practices, like such as codes of conduct, which seek to regulate the behavior of

employees. Marshall et al. (2005) follow the main stream as they stress the need for

infusing strong environmental values among employees throughout the company.

Zwetsloot (2003) highlight the importance of continuous learning related to management

system development in regards to CSR.

The above mentioned approaches to the role of employees in CSR both assume

employees as a coherent group or stakeholder that shares, or eventually comes to share,

approaches to CSR. However, some studies have highlighted the different perceptions

of CSR among employees. Both Howard-Grenville (2006) and Linnenluecke et al. (2009)

identify differences in employees’ understandings, but they explain the different

interpretations by the existence of different subcultures in organizational culture. Harris

and Crane (2002) identify confusion concerning the definitions and differences between

various concepts of organizational environmentalism among managers and cultural

greening not as a simple, one-dimensional concept. Baumgartner (2009) identified

discussions, uncertainty and tensions about sustainable development, especially about

further development regarding corporate sustainable development activities. Other

research has identified individual differences in employees’ orientation to CSR based, for

on the age of employee (Lipsett 2012). Furthermore, Ramus and Killmer (2007) point out

problems in the organizational integration of CSR: corporate greening behaviors are not

often formally required for an employee’s job and may suffer from a lack of clear goals or

certainty about organizational rewards. On the other hand, Zhu et al. (2012) and Alniacik

et al. (2011) showed the positive outcomes of CSR from the employee perspective.

Alniacik et al. found that positive CSR information enhances a potential employee’s

intentions to seek employment. Zhu et al. found worker satisfaction and commitment

persists as long as management is perceived to be making clear CSR efforts for

employees, such as enhancing the future security of their jobs.

Similar to the first main stream, which focused on employees as a stakeholder, this

second stream assumes employees as a unified group sharing views of corporate social

responsibility. However, the main difference is in the perspective that the latter one

stresses the need for change if management perceives that responsibility values are not

shared in the organization. If we perceive CSR only as top-down managed change

process, we encounter two major problems from the employee perspective: 1) the CSR

approach of the organization only relies on the managerial interpretation of the

organization, not on that of the employees who are supposed to implement it; and 2) The

employees will easily question the CSR approaches that are distant from their own work.

Studying Emotions toward CSR

employees as a coherent group or stakeholder that shares, or eventually comes to share,

approaches to CSR. However, some studies have highlighted the different perceptions

of CSR among employees. Both Howard-Grenville (2006) and Linnenluecke et al. (2009)

identify differences in employees’ understandings, but they explain the different

interpretations by the existence of different subcultures in organizational culture. Harris

and Crane (2002) identify confusion concerning the definitions and differences between

various concepts of organizational environmentalism among managers and cultural

greening not as a simple, one-dimensional concept. Baumgartner (2009) identified

discussions, uncertainty and tensions about sustainable development, especially about

further development regarding corporate sustainable development activities. Other

research has identified individual differences in employees’ orientation to CSR based, for

on the age of employee (Lipsett 2012). Furthermore, Ramus and Killmer (2007) point out

problems in the organizational integration of CSR: corporate greening behaviors are not

often formally required for an employee’s job and may suffer from a lack of clear goals or

certainty about organizational rewards. On the other hand, Zhu et al. (2012) and Alniacik

et al. (2011) showed the positive outcomes of CSR from the employee perspective.

Alniacik et al. found that positive CSR information enhances a potential employee’s

intentions to seek employment. Zhu et al. found worker satisfaction and commitment

persists as long as management is perceived to be making clear CSR efforts for

employees, such as enhancing the future security of their jobs.

Similar to the first main stream, which focused on employees as a stakeholder, this

second stream assumes employees as a unified group sharing views of corporate social

responsibility. However, the main difference is in the perspective that the latter one

stresses the need for change if management perceives that responsibility values are not

shared in the organization. If we perceive CSR only as top-down managed change

process, we encounter two major problems from the employee perspective: 1) the CSR

approach of the organization only relies on the managerial interpretation of the

organization, not on that of the employees who are supposed to implement it; and 2) The

employees will easily question the CSR approaches that are distant from their own work.

Studying Emotions toward CSR

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Emotions in work organizations have been defined from the social perspective:

According to Rafaeli and Worline (2001), emotions are essentially social, just as

people are. Fineman and Sturdy (1999) stress that emotions need to be understood

in terms of the social structures of which they are a part. Furthermore, Weiss and

Cropanzano (1996, p. 17) state that

Emotions are intuitively well understood yet a definitive definition of emotion has been

difficult to come by…an emotional reaction is not just one reaction but a constellation of

related reactions.

Emotions have been viewed from different perspectives (see Fineman and Sturdy

1999, p. 634), and the social perspective makes a distinction between the subjective

experience of emotions (feelings) and their personal/dramatic displays (emotions)

(Fineman, 1996b; Fineman and Sturdy, 1999). Fineman (1996b, p. 289) explains:

For those who spend much of their time in organizations, emotion talk is often taken for

granted: the gripes, the anger, the anxiety, the frustrations; the glee, the joy, the tedium,

the embarrassments, the despair. These are part of social creation and personal

expression of work and organizational life.

As Rafaeli and Worline (2001) suggest, emotions emerge within social collectives, so

work organizations are filled with emotions. Fineman (1996b) goes further, stating that

work activities are shaped by emotions.

Prior research on environmental responsibility has identified the emotional subtexts of

corporate greening (Fineman, 1996a), emotions related to environmental control

(Fineman and Sturdy, 1999) and the dangers of using dramatic and emotional

language in representing environmental issues in business (Andersson and Bateman,

2000). Fineman (1996a) identified four emotionally significant subtexts for corporate

greening: enacting green commitment, contesting green boundaries, defending

autonomy and avoiding embarrassment. These emotional subtexts were related to the

way green pressures were received and culturally incorporated or rejected by senior

managers in six UK supermarkets. It is especially noteworthy that managers do not

relate negative emotions only to rejecting green pressures and defending autonomy.

Many managers were keenly aware that they could be embarrassed by criticism of

their environmental record. Fineman and Sturdy (1999) continued research on

emotions in relation to environmental issues, as they identified emotions of control

among environmental regulatory inspectors and industrial managers in the UK.

Andersson and Bateman (2000) noted in their study that the use of dramatic and

According to Rafaeli and Worline (2001), emotions are essentially social, just as

people are. Fineman and Sturdy (1999) stress that emotions need to be understood

in terms of the social structures of which they are a part. Furthermore, Weiss and

Cropanzano (1996, p. 17) state that

Emotions are intuitively well understood yet a definitive definition of emotion has been

difficult to come by…an emotional reaction is not just one reaction but a constellation of

related reactions.

Emotions have been viewed from different perspectives (see Fineman and Sturdy

1999, p. 634), and the social perspective makes a distinction between the subjective

experience of emotions (feelings) and their personal/dramatic displays (emotions)

(Fineman, 1996b; Fineman and Sturdy, 1999). Fineman (1996b, p. 289) explains:

For those who spend much of their time in organizations, emotion talk is often taken for

granted: the gripes, the anger, the anxiety, the frustrations; the glee, the joy, the tedium,

the embarrassments, the despair. These are part of social creation and personal

expression of work and organizational life.

As Rafaeli and Worline (2001) suggest, emotions emerge within social collectives, so

work organizations are filled with emotions. Fineman (1996b) goes further, stating that

work activities are shaped by emotions.

Prior research on environmental responsibility has identified the emotional subtexts of

corporate greening (Fineman, 1996a), emotions related to environmental control

(Fineman and Sturdy, 1999) and the dangers of using dramatic and emotional

language in representing environmental issues in business (Andersson and Bateman,

2000). Fineman (1996a) identified four emotionally significant subtexts for corporate

greening: enacting green commitment, contesting green boundaries, defending

autonomy and avoiding embarrassment. These emotional subtexts were related to the

way green pressures were received and culturally incorporated or rejected by senior

managers in six UK supermarkets. It is especially noteworthy that managers do not

relate negative emotions only to rejecting green pressures and defending autonomy.

Many managers were keenly aware that they could be embarrassed by criticism of

their environmental record. Fineman and Sturdy (1999) continued research on

emotions in relation to environmental issues, as they identified emotions of control

among environmental regulatory inspectors and industrial managers in the UK.

Andersson and Bateman (2000) noted in their study that the use of dramatic and

emotional language in presenting environmental issues to gain top-management

support was not a significant predictor in the outcome of any championing episodes.

Rather the use of drama and emotion may have had a negative impact on the success

of championing episodes. Besides the environmental dimension, one can find

surprisingly little evidence on the emotions employees connect with CSR

Negative and positive affectivity are the main components of emotions (Weiss and

Cropanzano, 1996; Russell and Griffiths, 2008). Emotions can be represented in terms

of these two distinct dimensions. (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). As Fineman (1996a)

shows, both positive and negative emotions play a role in the adaptation of pro-

environmental behaviors within organizations. Managers spoke of positive emotions

in relation to commitment to environmental issues (such as belonging, respect, awe

and loyalty) but also negative emotions played a role, especially fear and

embarrassment. Thus there is evidence that both positive and negative emotions can

result in pro-environmental behavior.

In prior research, Rupp et al. (2006) stress the importance of employees’ emotions to

CSR. According to them, employees’ perceptions of CSR trigger emotional, attitudinal,

and behavioral responses. They form a theoretical proposition on employees’

perceptions CSR which states (p. 540):

Employee perceptions of CSR will exert positive effects on individually relevant

outcomes such as organizational attractiveness, job satisfaction, organizational

commitment, citizenship behavior, and job performance. Employee perceptions of CSR

will exert negative effects on individually-relevant outcomes such as anger.

Similar to the proposition of Rupp et al. (2006), Carrus et al. (2008) show that negative

anticipated emotions and past behavior are significant predictors of desire to engage

in pro-environmental action.

Rhetorical Approach

This study describes how the types of corporate social responsibility are rhetorically

constructed in the interviews with employees, following the assumption that language

has the power to contribute to our understanding of the formation of views of certain

corporations’ CSR (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). This study joins the school of new

support was not a significant predictor in the outcome of any championing episodes.

Rather the use of drama and emotion may have had a negative impact on the success

of championing episodes. Besides the environmental dimension, one can find

surprisingly little evidence on the emotions employees connect with CSR

Negative and positive affectivity are the main components of emotions (Weiss and

Cropanzano, 1996; Russell and Griffiths, 2008). Emotions can be represented in terms

of these two distinct dimensions. (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). As Fineman (1996a)

shows, both positive and negative emotions play a role in the adaptation of pro-

environmental behaviors within organizations. Managers spoke of positive emotions

in relation to commitment to environmental issues (such as belonging, respect, awe

and loyalty) but also negative emotions played a role, especially fear and

embarrassment. Thus there is evidence that both positive and negative emotions can

result in pro-environmental behavior.

In prior research, Rupp et al. (2006) stress the importance of employees’ emotions to

CSR. According to them, employees’ perceptions of CSR trigger emotional, attitudinal,

and behavioral responses. They form a theoretical proposition on employees’

perceptions CSR which states (p. 540):

Employee perceptions of CSR will exert positive effects on individually relevant

outcomes such as organizational attractiveness, job satisfaction, organizational

commitment, citizenship behavior, and job performance. Employee perceptions of CSR

will exert negative effects on individually-relevant outcomes such as anger.

Similar to the proposition of Rupp et al. (2006), Carrus et al. (2008) show that negative

anticipated emotions and past behavior are significant predictors of desire to engage

in pro-environmental action.

Rhetorical Approach

This study describes how the types of corporate social responsibility are rhetorically

constructed in the interviews with employees, following the assumption that language

has the power to contribute to our understanding of the formation of views of certain

corporations’ CSR (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). This study joins the school of new

rhetoric born under the influence of the linguistic turn in the 1960s (Billig, 1987;

Perelman, 1982; Potter, 1996) and makes no distinction between rhetoric and reality.

Here, rhetoric is a part of socially constructed reality. New rhetoric is based on the

assumption that it is possible and necessary to classify how credibility emerges for

certain claims and on what basis commitment to different conclusions occurs. Unlike

studies of realism, constructionist studies do not aim to reveal social reality, but focus

on how people construct versions of social reality in social interaction (Burr, 1995).

Billig (1987) points out that rhetoric should be seen as a pervasive feature of the way

people interact and arrive at understanding. Rhetorical argumentation is an essential

quality of all language use and a persuasive feature in social interaction, when people

aim to accomplish a common understanding.

The rhetorical approach does not offer an unambiguous, clear research method. It can

be understood as a loose theoretical framework that allows opportunities to use and

develop different methods for analyzing texts. My loose framework for analysis was

guided by the following rhetorical principles:

• Openness: Billig (1987) describes openness as a possibility to present different

arguments that, while they may be conflicting, all of them are arguable. Finding

just a single correct solution, as required by logic, is impossible. By applying

the rhetorical approach, I am interested in the possibility of finding alternative

views that Billig (1987) describes as especially characteristic of political, ethical

and juridical questions. My interest is in finding competing realities in the texts

I have analyzed.

• Emotionality: Gilbert (1995) stresses that scholars have recognized that some

arguments are emotional, and some very emotional. They are very context-

related and occur because there are times when the expression of such feeling

is important for us. Furthermore, early on Aristotle (see Summa, 1996; Palonen

and Summa, 1996) represented three levels of the means for persuasion:

ethos, pathos and logos. Ethos is related to how the speaker presents himself

to the audience. Pathos deals with the means that are used for preparing the

audience to listen to the speaker, and also thus deals with the interaction in the

argumentation and discussion process. Pathos refers to means that are used

to decrease any obstacles to communication. That type of persuasion deals

with the emotional aspects in argumentation. Logos deals with the logical

Perelman, 1982; Potter, 1996) and makes no distinction between rhetoric and reality.

Here, rhetoric is a part of socially constructed reality. New rhetoric is based on the

assumption that it is possible and necessary to classify how credibility emerges for

certain claims and on what basis commitment to different conclusions occurs. Unlike

studies of realism, constructionist studies do not aim to reveal social reality, but focus

on how people construct versions of social reality in social interaction (Burr, 1995).

Billig (1987) points out that rhetoric should be seen as a pervasive feature of the way

people interact and arrive at understanding. Rhetorical argumentation is an essential

quality of all language use and a persuasive feature in social interaction, when people

aim to accomplish a common understanding.

The rhetorical approach does not offer an unambiguous, clear research method. It can

be understood as a loose theoretical framework that allows opportunities to use and

develop different methods for analyzing texts. My loose framework for analysis was

guided by the following rhetorical principles:

• Openness: Billig (1987) describes openness as a possibility to present different

arguments that, while they may be conflicting, all of them are arguable. Finding

just a single correct solution, as required by logic, is impossible. By applying

the rhetorical approach, I am interested in the possibility of finding alternative

views that Billig (1987) describes as especially characteristic of political, ethical

and juridical questions. My interest is in finding competing realities in the texts

I have analyzed.

• Emotionality: Gilbert (1995) stresses that scholars have recognized that some

arguments are emotional, and some very emotional. They are very context-

related and occur because there are times when the expression of such feeling

is important for us. Furthermore, early on Aristotle (see Summa, 1996; Palonen

and Summa, 1996) represented three levels of the means for persuasion:

ethos, pathos and logos. Ethos is related to how the speaker presents himself

to the audience. Pathos deals with the means that are used for preparing the

audience to listen to the speaker, and also thus deals with the interaction in the

argumentation and discussion process. Pathos refers to means that are used

to decrease any obstacles to communication. That type of persuasion deals

with the emotional aspects in argumentation. Logos deals with the logical

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

structures of different types of arguments for a certain claim and thus with the

abstract content of the claim. (Summa, 1996; Palonen and Summa, 1996).

• Associations and dissociations: Perelman’s (1982) theory of argumentation is

one of the foundations of the school of new rhetoric. In it the basic idea is to

create a dissociation and association (liaisons) between two or more issues.

Using liaisons means associative argumentation, creating connections

between different phenomena. If arguments are given as dissociation, they aim

at separating elements which language or a recognized tradition has previously

tied together and thus it structures information in a new way. In dissociation,

different sides are separated in the phenomena and they are proportioned to

each other or some other phenomena (Perelman, 1982).

Material and Methods

Research context and material

Prior research on financial firms' CSR has focused on critical approaches to CSR

reporting (Coupland, 2006; Douglas et al., 2004). The financial firm in this study has a

clear goal to be a CSR pioneer in the Finnish financial industry. It clearly states this

goal on its website. It publishes a responsibility report, participates in multiple CSR

projects and some of its employees, including the CEO, are active members in Finnish

CSR networks. Furthermore, because the firm is a cooperative owned by its customers,

it must meet special requirements of transparency and responsibility. Both the goal to

be a CSR pioneer in a less studied business branch and the ownership of the firm offer

an especially interesting research setting for this study. The organization employs

about 3,000 people. The operations cover banking, financing and insurance services.

Recently the corporation has faced a challenge: they downsized 150 employees. From

this organization 27 people were interviewed (39–95 min/each) and people from all

levels of the organizational hierarchy participated.

A qualitative and interpretative approach (Kovalainen and Eriksson, 2008) was applied

in this study because the aim was to understand the richness and complexity of

abstract content of the claim. (Summa, 1996; Palonen and Summa, 1996).

• Associations and dissociations: Perelman’s (1982) theory of argumentation is

one of the foundations of the school of new rhetoric. In it the basic idea is to

create a dissociation and association (liaisons) between two or more issues.

Using liaisons means associative argumentation, creating connections

between different phenomena. If arguments are given as dissociation, they aim

at separating elements which language or a recognized tradition has previously

tied together and thus it structures information in a new way. In dissociation,

different sides are separated in the phenomena and they are proportioned to

each other or some other phenomena (Perelman, 1982).

Material and Methods

Research context and material

Prior research on financial firms' CSR has focused on critical approaches to CSR

reporting (Coupland, 2006; Douglas et al., 2004). The financial firm in this study has a

clear goal to be a CSR pioneer in the Finnish financial industry. It clearly states this

goal on its website. It publishes a responsibility report, participates in multiple CSR

projects and some of its employees, including the CEO, are active members in Finnish

CSR networks. Furthermore, because the firm is a cooperative owned by its customers,

it must meet special requirements of transparency and responsibility. Both the goal to

be a CSR pioneer in a less studied business branch and the ownership of the firm offer

an especially interesting research setting for this study. The organization employs

about 3,000 people. The operations cover banking, financing and insurance services.

Recently the corporation has faced a challenge: they downsized 150 employees. From

this organization 27 people were interviewed (39–95 min/each) and people from all

levels of the organizational hierarchy participated.

A qualitative and interpretative approach (Kovalainen and Eriksson, 2008) was applied

in this study because the aim was to understand the richness and complexity of

interactions and processes in social contexts. All the interviews focused on the

meaning of CSR in the interviewees’ daily work. All the interviews covered the same

four themes: job description of the interviewee, views on CSR in the corporation,

internal CSR communication, external CSR communication. All the topics were openly

discussed from the viewpoint of the employees’ daily job. The questions had an open-

ended structure, for example: Could tell me about your normal work day? How do you

relate to CSR in your corporation? How are you informed about CSR?

Analysis

I analyzed the interviews as argumentative texts in which versions of the employing

organization’s corporate social responsibility are being constructed, looking especially

at the types of emotional arguments used. I read through the interviews several times

and noticed that emotions repeatedly emerged when talking about the employing

organization’s CSR. I then used Atlas.ti for coding all the parts of the interviews in

which emotional arguments were explicitly used by the interviewees and reduced the

data. I then excluded those parts that did not deal with my research interest. I followed

the principles of rhetorical analysis (explained above) to analyze each extract with

explicit emotions and listed the emotion, its positive or negative meaning and what the

CSR is associated/dissociated with. For representation of the positive and negative

meaning, certain contrasts were identified. The interviewees used, for example,

certain positively laden emotions in the negative sense (e.g., “disappointment because

the firm lacks courage”) and vice versa. An example of the coding and analysis

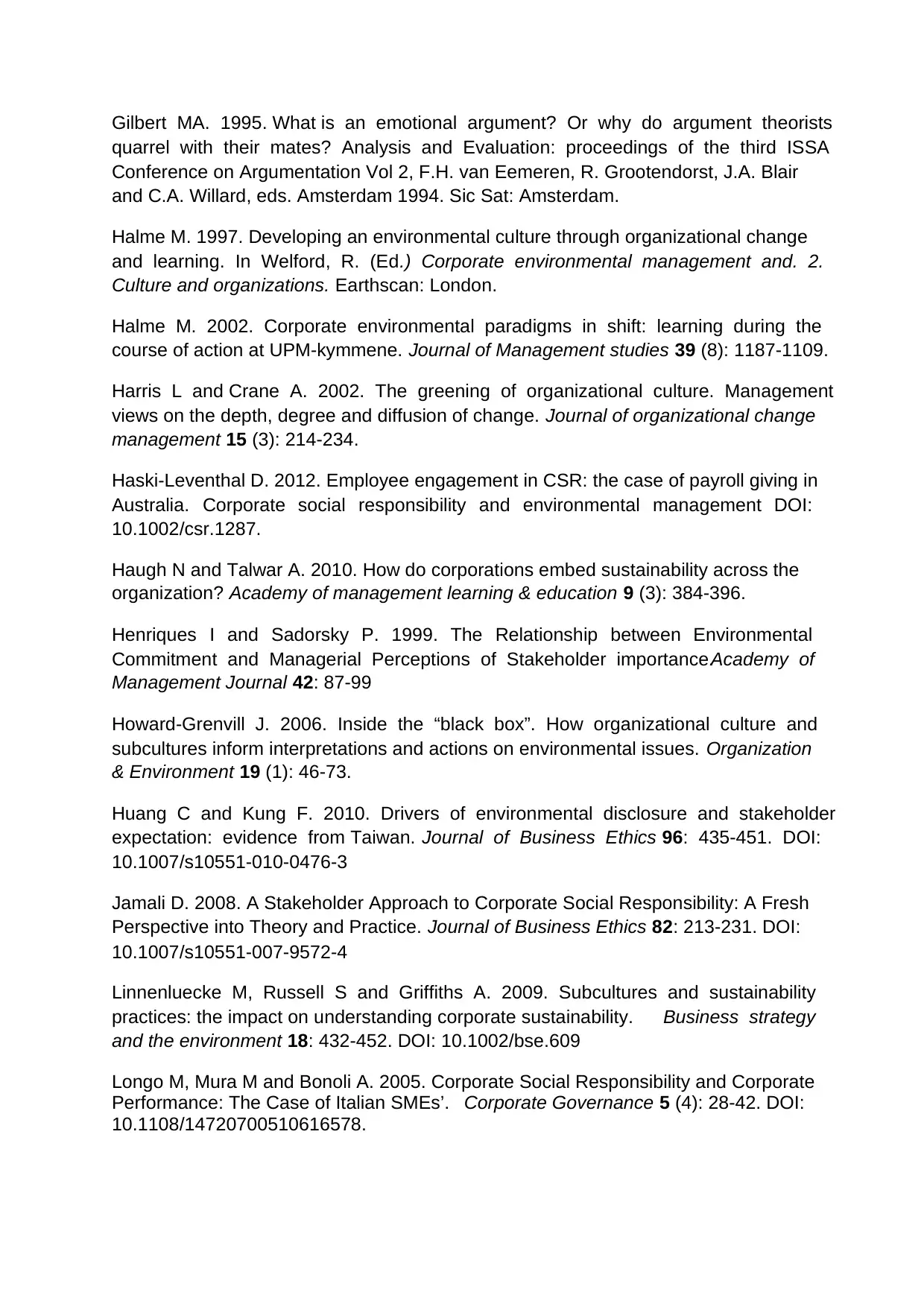

process is represented in Table 1.

------------------------------ INSERT TABLE1 ABOUT HERE----------------------------------

At this point in the analysis I noticed that emotional arguments were used to construct

different meanings for the employing organization’s CSR. I then continued by

analyzing the similarities and differences and arrived at two negative and four positive

ways of using emotional arguments to produce meanings of the employing

organization’s CSR. In all of them the interviewees produced a view of where their

meaning of CSR in the interviewees’ daily work. All the interviews covered the same

four themes: job description of the interviewee, views on CSR in the corporation,

internal CSR communication, external CSR communication. All the topics were openly

discussed from the viewpoint of the employees’ daily job. The questions had an open-

ended structure, for example: Could tell me about your normal work day? How do you

relate to CSR in your corporation? How are you informed about CSR?

Analysis

I analyzed the interviews as argumentative texts in which versions of the employing

organization’s corporate social responsibility are being constructed, looking especially

at the types of emotional arguments used. I read through the interviews several times

and noticed that emotions repeatedly emerged when talking about the employing

organization’s CSR. I then used Atlas.ti for coding all the parts of the interviews in

which emotional arguments were explicitly used by the interviewees and reduced the

data. I then excluded those parts that did not deal with my research interest. I followed

the principles of rhetorical analysis (explained above) to analyze each extract with

explicit emotions and listed the emotion, its positive or negative meaning and what the

CSR is associated/dissociated with. For representation of the positive and negative

meaning, certain contrasts were identified. The interviewees used, for example,

certain positively laden emotions in the negative sense (e.g., “disappointment because

the firm lacks courage”) and vice versa. An example of the coding and analysis

process is represented in Table 1.

------------------------------ INSERT TABLE1 ABOUT HERE----------------------------------

At this point in the analysis I noticed that emotional arguments were used to construct

different meanings for the employing organization’s CSR. I then continued by

analyzing the similarities and differences and arrived at two negative and four positive

ways of using emotional arguments to produce meanings of the employing

organization’s CSR. In all of them the interviewees produced a view of where their

employing organization's CSR is derived from. The data was originally produced in

Finnish, and the analysis process was conducted in the original language. The extracts

used in this article were then translated by a professional and checked by the

researchers in order to preserve their original meanings.

Results

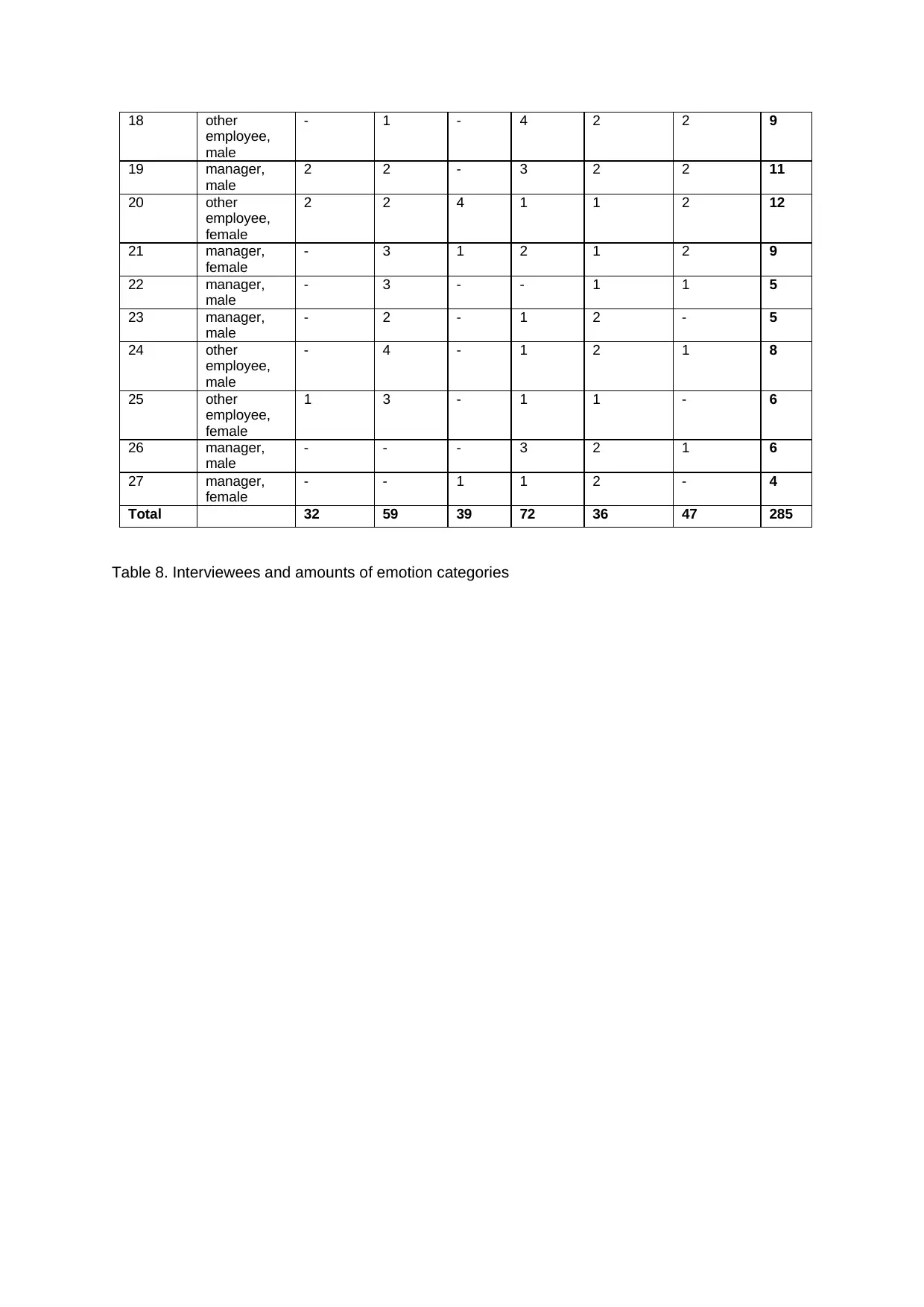

During my analysis process I identified six different categories of emotional arguments

to construct a view of the employing organization’s CSR. Two of them are negatively

laden and four of them are positively laden. The negative categories are cynicism and

discomfort in one’s own work and Irritation and lack of shared courage. The positive

categories are: Close to my heart and pride, Shared good will, Distinction from greed

and Avoidance of shame. In each of these categories, a view of the employing

organization’s CSR is constructed that takes a stance on where their employing

organization’s CSR is derived from. Altogether I analyzed 285 instances of emotions

being related to a certain view of the employing organization's CSR. In 91 (32%) of

them, a negative meaning emerged, and in 194 (68%) of them the positive meaning

emerged. In the following section I explain the content of each category and the view

produced.

Negative Categories

Cynicism and discomfort in one’s own work

The first negative category of emotional arguments is associated with cynicism and

discomfort within the boundaries of the employees’ daily work. The employing

organization’s CSR is defined here through individual choices and the work of

employees. This category was identified 32 (11%) times in the data. It associates the

descriptions of CSR with negative experiences and emotions within their own work.

Negative experiences are related, for example, to the difficulty of and boundaries on

making responsible decisions in their own work, irresponsible organizational action

faced in their own work and to the lack of opportunities to implement responsibility in

their own work. Thus the view of CSR constructed here is individualistic. It is especially

produced and defined through the boundaries of their own work, through what defines

how well or how poorly they can personally implement responsibility in their work. At

Finnish, and the analysis process was conducted in the original language. The extracts

used in this article were then translated by a professional and checked by the

researchers in order to preserve their original meanings.

Results

During my analysis process I identified six different categories of emotional arguments

to construct a view of the employing organization’s CSR. Two of them are negatively

laden and four of them are positively laden. The negative categories are cynicism and

discomfort in one’s own work and Irritation and lack of shared courage. The positive

categories are: Close to my heart and pride, Shared good will, Distinction from greed

and Avoidance of shame. In each of these categories, a view of the employing

organization’s CSR is constructed that takes a stance on where their employing

organization’s CSR is derived from. Altogether I analyzed 285 instances of emotions

being related to a certain view of the employing organization's CSR. In 91 (32%) of

them, a negative meaning emerged, and in 194 (68%) of them the positive meaning

emerged. In the following section I explain the content of each category and the view

produced.

Negative Categories

Cynicism and discomfort in one’s own work

The first negative category of emotional arguments is associated with cynicism and

discomfort within the boundaries of the employees’ daily work. The employing

organization’s CSR is defined here through individual choices and the work of

employees. This category was identified 32 (11%) times in the data. It associates the

descriptions of CSR with negative experiences and emotions within their own work.

Negative experiences are related, for example, to the difficulty of and boundaries on

making responsible decisions in their own work, irresponsible organizational action

faced in their own work and to the lack of opportunities to implement responsibility in

their own work. Thus the view of CSR constructed here is individualistic. It is especially

produced and defined through the boundaries of their own work, through what defines

how well or how poorly they can personally implement responsibility in their work. At

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the same time, this argumentation questions organizational support for responsible

choices and the work of individuals and considers whether it is even organizationally

prevented. The explicit emotions expressed included cynicism, frustration, stress,

displeasure and anxiety.

The following extract provides an example of this type of argumentation. Here the

interviewee was a person who was partially responsible for CSR issues in the

organization (in addition to other duties) and he describes how his attitude toward CSR

issues has developed:

At some point a lot of other work came up and I just wasn’t able to focus on

communicating about CSR as much I’d perhaps have wanted to. And it also felt that at

the beginning I believed in the whole issue a bit more. But I have to say that at some

point a certain kind of cynicism set in…there just wasn’t the possibility for this sort of

work and it just started to feel like it was maybe falling on deaf ears. And so my faith just

sort of faded.

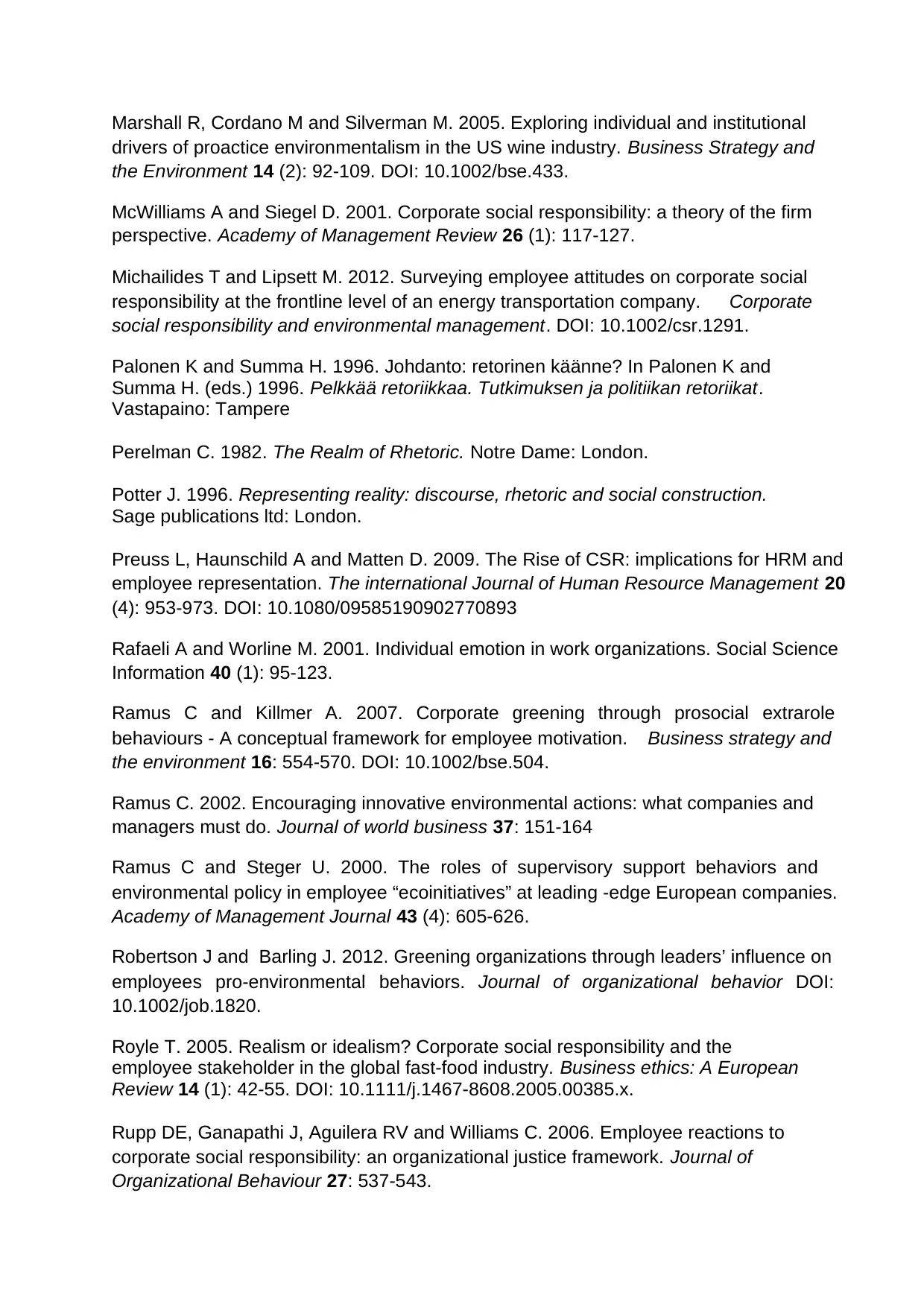

Table 2 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

----------------------------------INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE------------------------------

Irritation and lack of shared courage

The second negative category of emotional arguments questions the organizational

“will and spirit” for responsibility and at the same constructs a view of the employing

organization’s CSR that would mean shared and collective action. This category was

identified 59 (21%) times in the data. The main difference here with “cynicism and

discomfort within one’s own work” is that this first category relied on an individualistic

view of CSR whereas this second category stresses a collective approach. In this

argumentation explicit emotions are related to shortcomings of current corporate

approaches to responsibility, such as lacking a shared “spirit”, a lack of internal

changes, distance between CSR and usual employee, lack of CSR in daily practices

and poor practical implementation. In extreme cases, current approaches to CSR were

described as publicity stunts and related to green washing. This argumentation

questions whether the corporation is really responsible or whether it only talks like it

choices and the work of individuals and considers whether it is even organizationally

prevented. The explicit emotions expressed included cynicism, frustration, stress,

displeasure and anxiety.

The following extract provides an example of this type of argumentation. Here the

interviewee was a person who was partially responsible for CSR issues in the

organization (in addition to other duties) and he describes how his attitude toward CSR

issues has developed:

At some point a lot of other work came up and I just wasn’t able to focus on

communicating about CSR as much I’d perhaps have wanted to. And it also felt that at

the beginning I believed in the whole issue a bit more. But I have to say that at some

point a certain kind of cynicism set in…there just wasn’t the possibility for this sort of

work and it just started to feel like it was maybe falling on deaf ears. And so my faith just

sort of faded.

Table 2 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

----------------------------------INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE------------------------------

Irritation and lack of shared courage

The second negative category of emotional arguments questions the organizational

“will and spirit” for responsibility and at the same constructs a view of the employing

organization’s CSR that would mean shared and collective action. This category was

identified 59 (21%) times in the data. The main difference here with “cynicism and

discomfort within one’s own work” is that this first category relied on an individualistic

view of CSR whereas this second category stresses a collective approach. In this

argumentation explicit emotions are related to shortcomings of current corporate

approaches to responsibility, such as lacking a shared “spirit”, a lack of internal

changes, distance between CSR and usual employee, lack of CSR in daily practices

and poor practical implementation. In extreme cases, current approaches to CSR were

described as publicity stunts and related to green washing. This argumentation

questions whether the corporation is really responsible or whether it only talks like it

would be. The explicit emotions expressed included annoyance, disappointment over

the lack of good heart and courage, cynicism, anxiety and uncertainty.

In the following example an interviewee expresses his annoyance over current CSR

practices in the organization and questions whether it is only done as a duty like in all

other big firms:

Yeah, sure, it’s great that these things get thought about, but it’s kind of a pity that the

way they get implemented in practice is pretty poor, that there’s a bit of a feeling that this

is kind of a given, that these things are done only because these days a big company is

supposed to have some environmental responsibility and corporate responsibility thing,

that it’s not now…I guess it’s just that the whole thing should be a little more visible in

practice too.

Table 3 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

----------------------------------INSERT TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE------------------------------

Positive Categories

Close to one’s heart and pride

The first positive category of using emotional arguments associates CSR with its

importance in an individuals’ own work and with personal commitment. This category

was identified 39 (14%) times in the data. The category relies on a similar perspective

of the employing organization’s CSR as the category Cynicism and discomfort within

one’s own work, namely, that CSR is defined in the individual choices and work of

employees. Here, however, the argumentation leans on positive emotions related to

one’s own work. The argumentation constructs a view of a responsible employee for

whom personal commitment to CSR is important. It happens by stressing the

importance of their own work for the employer’s CSR, by expressing the personal

commitment to CSR and by expressing the importance of personal values to

responsibility. Typically for this argumentation the interviewees explained that

responsibility has great importance for them and CSR is “close to my heart”. In this

case the approach to CSR was individualistic: produced through personal commitment

the lack of good heart and courage, cynicism, anxiety and uncertainty.

In the following example an interviewee expresses his annoyance over current CSR

practices in the organization and questions whether it is only done as a duty like in all

other big firms:

Yeah, sure, it’s great that these things get thought about, but it’s kind of a pity that the

way they get implemented in practice is pretty poor, that there’s a bit of a feeling that this

is kind of a given, that these things are done only because these days a big company is

supposed to have some environmental responsibility and corporate responsibility thing,

that it’s not now…I guess it’s just that the whole thing should be a little more visible in

practice too.

Table 3 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

----------------------------------INSERT TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE------------------------------

Positive Categories

Close to one’s heart and pride

The first positive category of using emotional arguments associates CSR with its

importance in an individuals’ own work and with personal commitment. This category

was identified 39 (14%) times in the data. The category relies on a similar perspective

of the employing organization’s CSR as the category Cynicism and discomfort within

one’s own work, namely, that CSR is defined in the individual choices and work of

employees. Here, however, the argumentation leans on positive emotions related to

one’s own work. The argumentation constructs a view of a responsible employee for

whom personal commitment to CSR is important. It happens by stressing the

importance of their own work for the employer’s CSR, by expressing the personal

commitment to CSR and by expressing the importance of personal values to

responsibility. Typically for this argumentation the interviewees explained that

responsibility has great importance for them and CSR is “close to my heart”. In this

case the approach to CSR was individualistic: produced through personal commitment

and personal promotion of CSR. The explicit emotions expressed included pride,

enthusiasm, gratification and fulfillment.

The following extract is an example of this argumentation. The interviewee describes

her own commitment to CSR and continues by showing how the values are promoted

in the organization.

I’ve usually taken part in all the extra projects with enthusiasm and this responsibility

issue is one that is actually pretty close to my heart. If you think about it, when getting

familiar with the field for example, so we try to say how they should work in practice so

that everything in all ways goes right and responsibly.

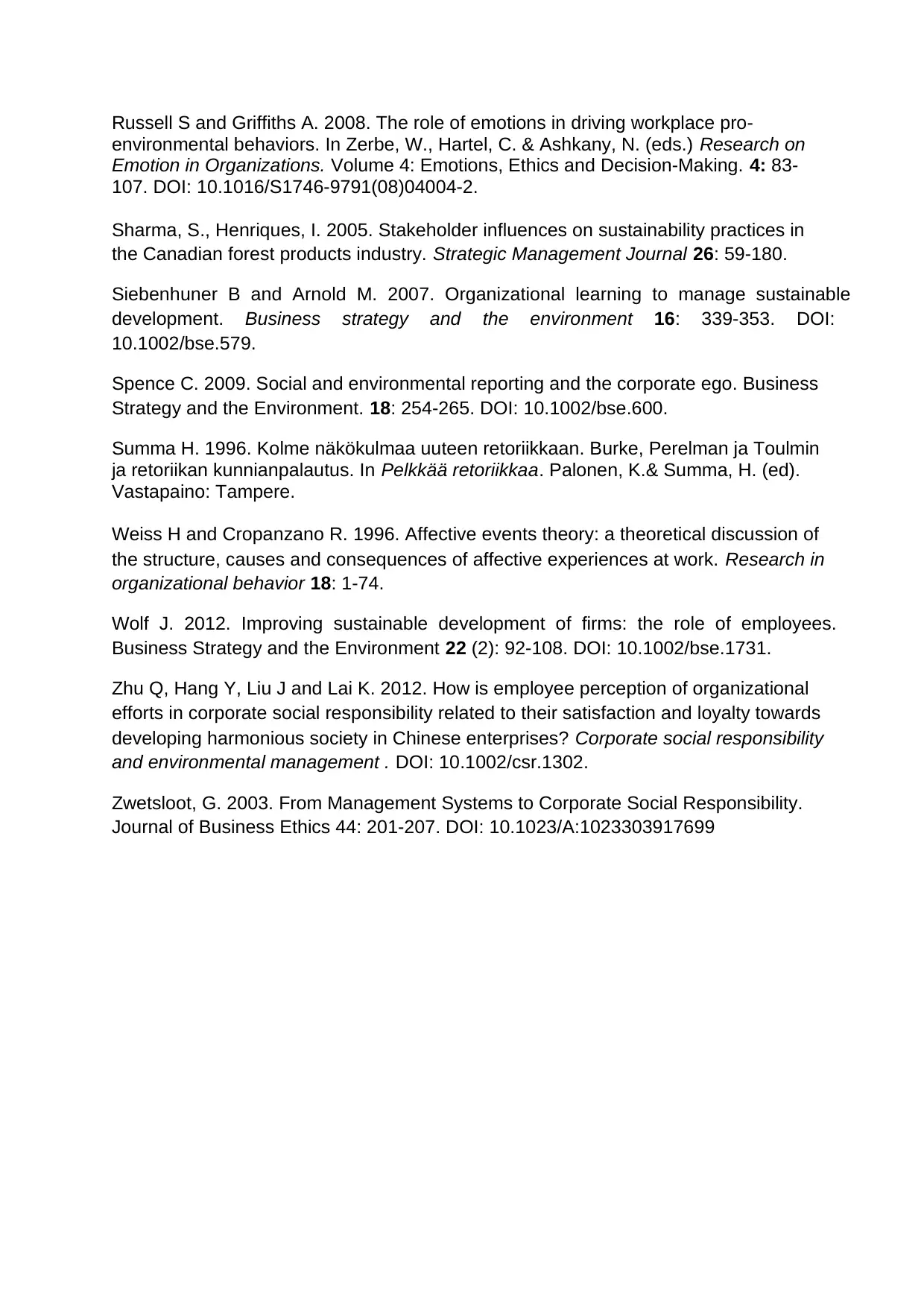

Table 4 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

------------------------------INSERT TABLE 4 ABOUT HERE-----------------------------------

Shared good will

The second positive category of emotional arguments associates positive emotions

with shared values and a “spirit” of responsibility in the organization. This category

was identified 72 (25%) times in the data and thus it was the most frequently used in

the data. This is expressed in two meanings in the data: by descriptions of shared

values between individual employees and organizational values, and by descriptions

of a shared spirit for CSR among organizational members. Shared values between an

employee and the organization are described as organizational values ”with which one

can identify” and in statements such as the following: ”It would be hard to work

somewhere that didn’t operate according to my values” and ”I like it here, because this

company reflects my values”. Shared spirit among organizational members was found

in statements that expressed “pride in the shared values, pride that nobody resists

CSR, being happy that they could not complain about their colleagues, and that

employees “can sell with good conscience”. The view of CSR constructed here was

collective, produced and defined in collective shared values and mindsets. At the same

time, this argumentation led to a view of an integrated organizational culture

concerning CSR. The explicit emotions expressed included liking, comfort,

identification, pride, positivity, good will and agreement.

enthusiasm, gratification and fulfillment.

The following extract is an example of this argumentation. The interviewee describes

her own commitment to CSR and continues by showing how the values are promoted

in the organization.

I’ve usually taken part in all the extra projects with enthusiasm and this responsibility

issue is one that is actually pretty close to my heart. If you think about it, when getting

familiar with the field for example, so we try to say how they should work in practice so

that everything in all ways goes right and responsibly.

Table 4 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

------------------------------INSERT TABLE 4 ABOUT HERE-----------------------------------

Shared good will

The second positive category of emotional arguments associates positive emotions

with shared values and a “spirit” of responsibility in the organization. This category

was identified 72 (25%) times in the data and thus it was the most frequently used in

the data. This is expressed in two meanings in the data: by descriptions of shared

values between individual employees and organizational values, and by descriptions

of a shared spirit for CSR among organizational members. Shared values between an

employee and the organization are described as organizational values ”with which one

can identify” and in statements such as the following: ”It would be hard to work

somewhere that didn’t operate according to my values” and ”I like it here, because this

company reflects my values”. Shared spirit among organizational members was found

in statements that expressed “pride in the shared values, pride that nobody resists

CSR, being happy that they could not complain about their colleagues, and that

employees “can sell with good conscience”. The view of CSR constructed here was

collective, produced and defined in collective shared values and mindsets. At the same

time, this argumentation led to a view of an integrated organizational culture

concerning CSR. The explicit emotions expressed included liking, comfort,

identification, pride, positivity, good will and agreement.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

The following extract is an example of this argumentation. The interviewee

responded to the question of whether it is significant for him to be employed in an

organization that practices CSR.

Interviewee: I can’t, I can’t, well, it would be hard for me to work somewhere that

operated against my own values.

Interviewer: I see. Which of your own values especially connect with (financial firm’s)

business?

Interviewee: Well, for example, there’s how, well, there’s how, when you meet

someone else, so how you treat that other person in that situation, whether it’s a

customer, a customer, or like someone from the staff, someone, whoever, a partner.

Table 5 describes the expressed emotions, rhetorical association and the view of

where CSR is derived from as constructed in this category.

------------------------------------INSERT TABLE 5 ABOUT HERE-------------------------

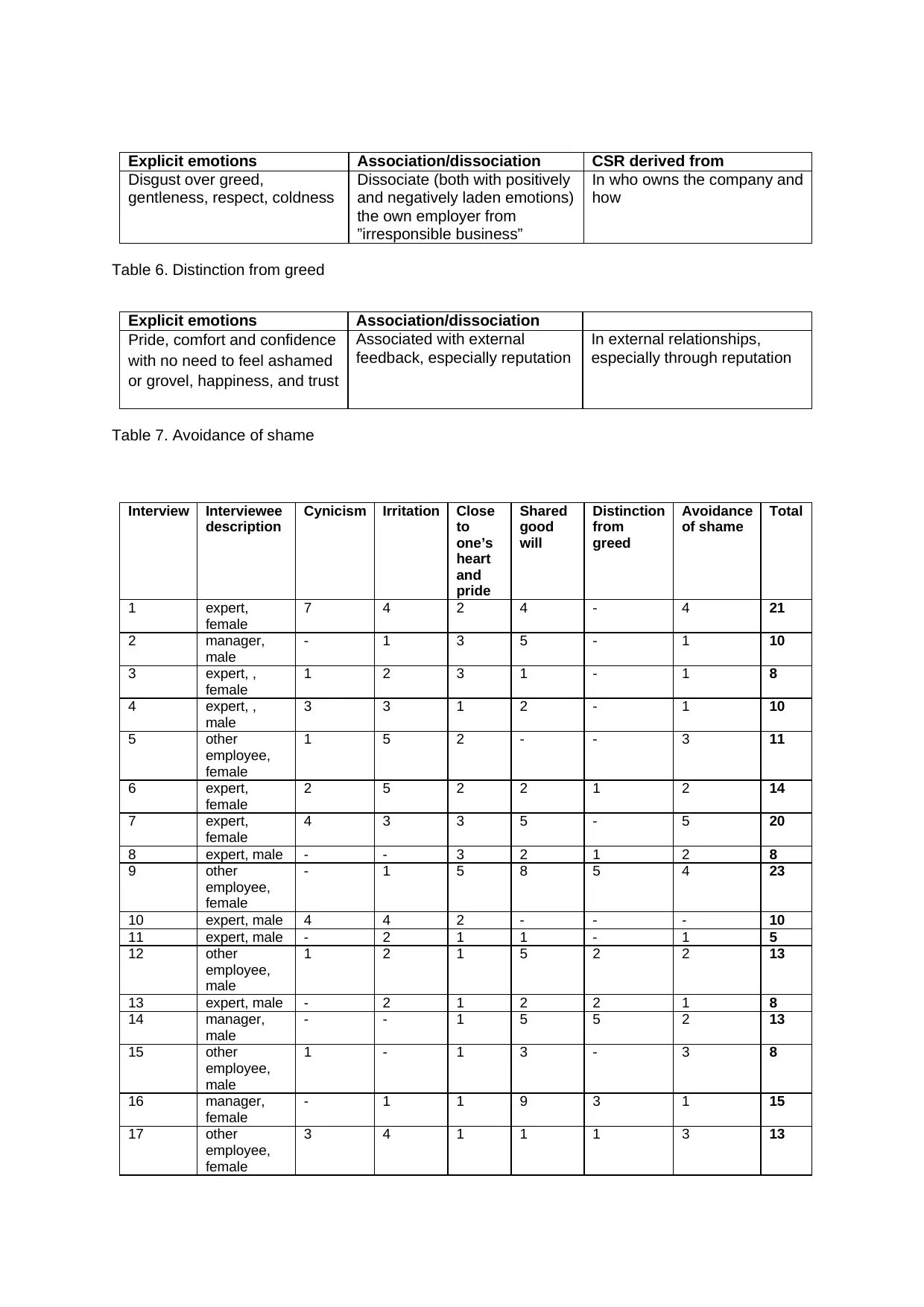

Distinction from greed

The third positive category of emotional arguments is constructed with different

argumentation tactics: instead of using emotional arguments for association, it creates

dissociation between the employing organization and other businesses. In addition,

both positively and negatively laden emotional arguments are used for constructing

this distinction. This category was identified 36 (13%) times in the data. It is especially

based on the organizational form of the firm as a co-operative owned by its customers.

This ownership model, according to the employees, leads to totally different premises

for business action as well as for corporate social responsibility compared with publicly

traded companies. Because the firm is a co-operative it leads to business that is,

according to the interviewees, “more humane instead of cold and serious” and to

building all the operations on the principle that the “other party is respected”. In this

argumentation, the interviewees construct the view that who own a company and how

has a great influence on CSR. The explicit emotions expressed are both positively (to

describe the employing organization) and negatively laden (to distinguish other

businesses). The explicit emotions expressed include disgust over a company’s greed,

gentleness, respect and coldness.

responded to the question of whether it is significant for him to be employed in an

organization that practices CSR.

Interviewee: I can’t, I can’t, well, it would be hard for me to work somewhere that

operated against my own values.

Interviewer: I see. Which of your own values especially connect with (financial firm’s)

business?

Interviewee: Well, for example, there’s how, well, there’s how, when you meet

someone else, so how you treat that other person in that situation, whether it’s a

customer, a customer, or like someone from the staff, someone, whoever, a partner.