Energy Geography - Industrial Revolution

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/18

|24

|7229

|16

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running Head: ENERGY GEOGRAPHY

Energy in Industrial Revolution

Name

Institutional affiliation

Energy in Industrial Revolution

Name

Institutional affiliation

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 2

Contents

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................3

OBJECTIVES..................................................................................................................................................4

METHODOLOGY...........................................................................................................................................4

Case Studies.............................................................................................................................................4

Secondary Sources...................................................................................................................................5

Case Study of the First Industrial Revolution in Britain........................................................................5

Case Study on Just Transition in South Africa......................................................................................6

ANALYSIS.....................................................................................................................................................7

Role of Energy in Industrial Revolution....................................................................................................7

The Just Transition...................................................................................................................................9

Industrial Revolution and Just Transition...............................................................................................11

Just Transition in South Africa...............................................................................................................12

Coal in South Africa...........................................................................................................................12

Life After Coal....................................................................................................................................13

Employments.....................................................................................................................................13

Regional Economic Developments....................................................................................................14

Political Impacts.................................................................................................................................15

Institutions for Just Transition...........................................................................................................15

Just Transition in South Korea...............................................................................................................16

Institutions for Just Transition...........................................................................................................17

Policies...............................................................................................................................................18

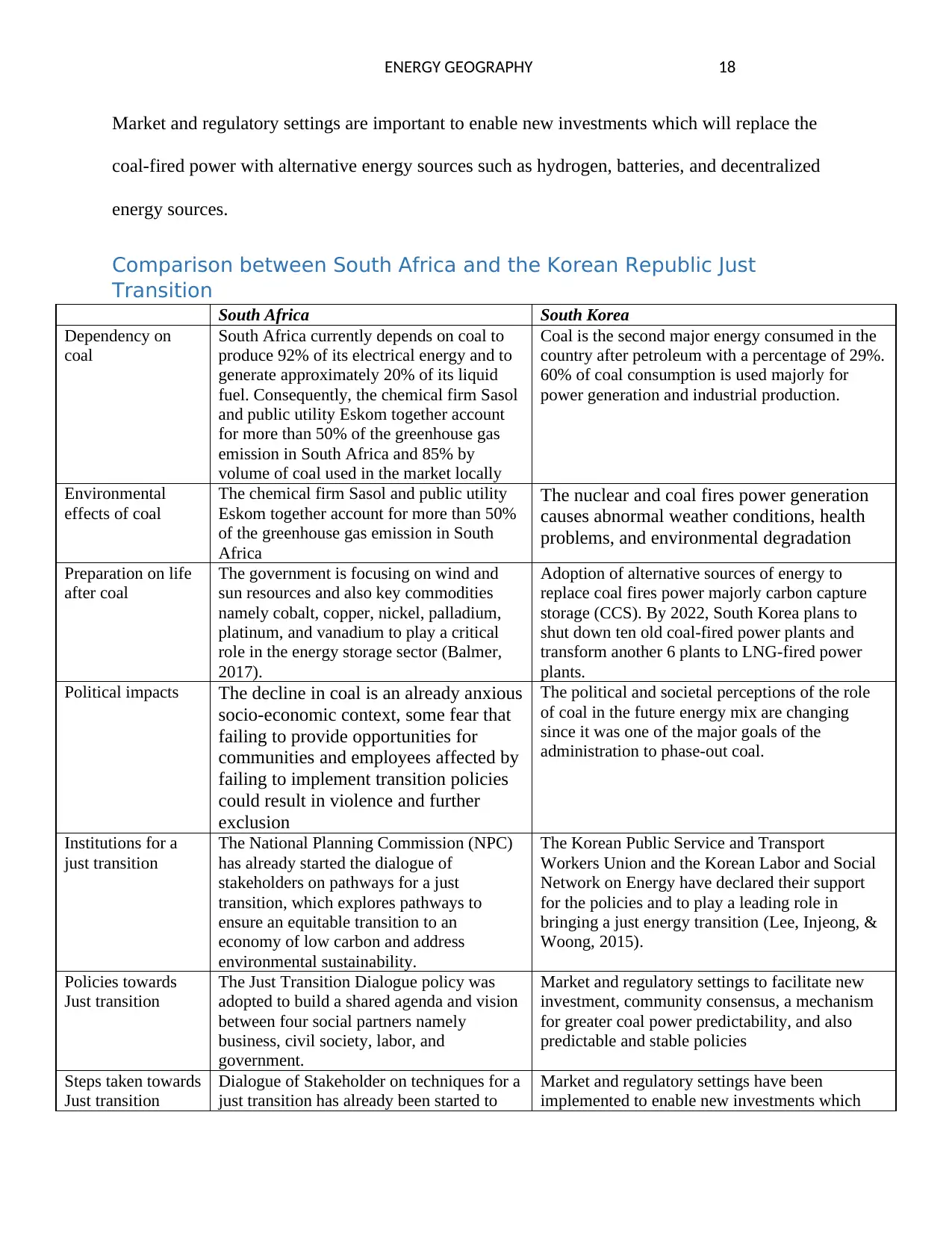

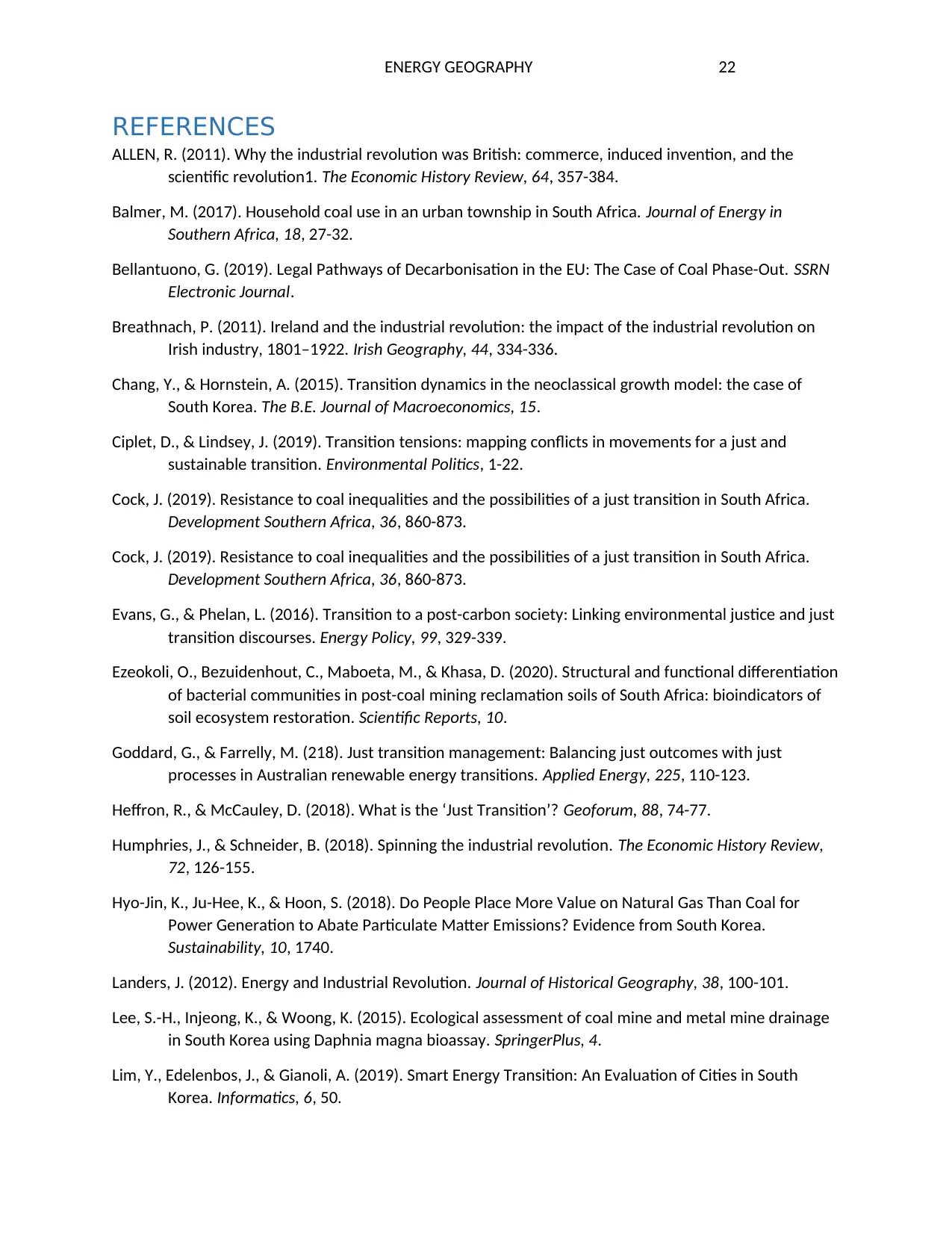

Comparison between South Africa and the Korean Republic Just Transition........................................18

Alliances for Transition Management....................................................................................................19

CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................................................20

RECOMMENDATION..................................................................................................................................21

REFERENCES..............................................................................................................................................22

Contents

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................3

OBJECTIVES..................................................................................................................................................4

METHODOLOGY...........................................................................................................................................4

Case Studies.............................................................................................................................................4

Secondary Sources...................................................................................................................................5

Case Study of the First Industrial Revolution in Britain........................................................................5

Case Study on Just Transition in South Africa......................................................................................6

ANALYSIS.....................................................................................................................................................7

Role of Energy in Industrial Revolution....................................................................................................7

The Just Transition...................................................................................................................................9

Industrial Revolution and Just Transition...............................................................................................11

Just Transition in South Africa...............................................................................................................12

Coal in South Africa...........................................................................................................................12

Life After Coal....................................................................................................................................13

Employments.....................................................................................................................................13

Regional Economic Developments....................................................................................................14

Political Impacts.................................................................................................................................15

Institutions for Just Transition...........................................................................................................15

Just Transition in South Korea...............................................................................................................16

Institutions for Just Transition...........................................................................................................17

Policies...............................................................................................................................................18

Comparison between South Africa and the Korean Republic Just Transition........................................18

Alliances for Transition Management....................................................................................................19

CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................................................20

RECOMMENDATION..................................................................................................................................21

REFERENCES..............................................................................................................................................22

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 3

INTRODUCTION

This research paper discusses the role of energy in the industrial revolution and also just

transition in South Africa and South Korea. The research also compares just transition in South

Africa to another country and then suggests the alliances South Africa may develop to manage

the transition. The industrial revolution started in the 18th century when agricultural societies

became more urban and industrialized. Industrial revolution can be defined as the process of

change from handicraft an agrarian economy to one dominated by machine and industry

manufacturing (Tomory, 2016). This transition was characterized by the development of

machine tools, the rise of the mechanized factory system, the increasing use of water power and

steam power, new iron production, and chemical manufacturing processes, and also going to

machines from hand production methods.

The industrial revolution was majorly confined in Britain in the period 1760 and 1830. France

was less thoroughly and more slowly industrialized than either Belgium or Britain. The major

features of the industrial revolution were cultural, socioeconomic, and technological changes

(Humphries & Schneider, 2018). The changes in technology included an increase in application

of science in industry; Significant developments in communication and transportation including

radio, telegraph, airplane, automobile, steamship, and steam locomotive; a new organization of

work known as the factory system which entailed increased specialization and division of labor;

the invention of new machines like power loom and spinning jenny which enabled production

increase with minimal human energy expenditure; the use of new sources of energy including

both motive power and fuels like internal combustion engine, petroleum, electricity, steam

engine, and coal; and also the application of new basic material majorly steel and iron

(Breathnach, 2011).

INTRODUCTION

This research paper discusses the role of energy in the industrial revolution and also just

transition in South Africa and South Korea. The research also compares just transition in South

Africa to another country and then suggests the alliances South Africa may develop to manage

the transition. The industrial revolution started in the 18th century when agricultural societies

became more urban and industrialized. Industrial revolution can be defined as the process of

change from handicraft an agrarian economy to one dominated by machine and industry

manufacturing (Tomory, 2016). This transition was characterized by the development of

machine tools, the rise of the mechanized factory system, the increasing use of water power and

steam power, new iron production, and chemical manufacturing processes, and also going to

machines from hand production methods.

The industrial revolution was majorly confined in Britain in the period 1760 and 1830. France

was less thoroughly and more slowly industrialized than either Belgium or Britain. The major

features of the industrial revolution were cultural, socioeconomic, and technological changes

(Humphries & Schneider, 2018). The changes in technology included an increase in application

of science in industry; Significant developments in communication and transportation including

radio, telegraph, airplane, automobile, steamship, and steam locomotive; a new organization of

work known as the factory system which entailed increased specialization and division of labor;

the invention of new machines like power loom and spinning jenny which enabled production

increase with minimal human energy expenditure; the use of new sources of energy including

both motive power and fuels like internal combustion engine, petroleum, electricity, steam

engine, and coal; and also the application of new basic material majorly steel and iron

(Breathnach, 2011).

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 4

OBJECTIVES

The purpose and objectives of this research paper include:

To analyze the role of energy in the industrial revolution

To discuss just transition in South Africa and South Korea.

To compare just transition in South Africa to another country

To suggest the alliances South Africa may develop to manage the transition

METHODOLOGY

The sources of data adopted for this research on the role of energy in the industrial revolution

include secondary sources and case studies.

Case Studies

This research methodology involves a detailed, in-depth, and close scrutiny of a particular case

by following a formal method of research. The case study research method allows the

exploration and understanding of complex issues through reports of past studies. Through a case

study, it is possible to go beyond the quantitative statistical method and understand the behavior

conditions through the perspective of different people (Widdowson, 2011). The case studies that

would be examined in this research include the industrial revolution, use of energy in the

industrial revolution, application of industrial revolution to the just transition, and comparison of

the just transition in South Africa another company and then suggesting the alliances South

Africa may develop to manage transition (Tight, 2010). These case studies are likely to appear in

formal research venues as journals and professional conferences and not popular studies.

Case study research method involves multiple or single case studies, quantitative evidence,

benefits from prior theoretical proposition development and relies on different sources of

evidence. Case study assists in explaining both the outcome and process if the industrial

revolution through complete analysis, reconstruction, and observation. Case studies also in their

OBJECTIVES

The purpose and objectives of this research paper include:

To analyze the role of energy in the industrial revolution

To discuss just transition in South Africa and South Korea.

To compare just transition in South Africa to another country

To suggest the alliances South Africa may develop to manage the transition

METHODOLOGY

The sources of data adopted for this research on the role of energy in the industrial revolution

include secondary sources and case studies.

Case Studies

This research methodology involves a detailed, in-depth, and close scrutiny of a particular case

by following a formal method of research. The case study research method allows the

exploration and understanding of complex issues through reports of past studies. Through a case

study, it is possible to go beyond the quantitative statistical method and understand the behavior

conditions through the perspective of different people (Widdowson, 2011). The case studies that

would be examined in this research include the industrial revolution, use of energy in the

industrial revolution, application of industrial revolution to the just transition, and comparison of

the just transition in South Africa another company and then suggesting the alliances South

Africa may develop to manage transition (Tight, 2010). These case studies are likely to appear in

formal research venues as journals and professional conferences and not popular studies.

Case study research method involves multiple or single case studies, quantitative evidence,

benefits from prior theoretical proposition development and relies on different sources of

evidence. Case study assists in explaining both the outcome and process if the industrial

revolution through complete analysis, reconstruction, and observation. Case studies also in their

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 5

true essence, investigate and explore the role of energy in the industrial revolution in Britain

through detailed contextual analysis.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources of data consist of information that has been collected and normally

interpreted by other researchers and then recorded in articles, books, and other publications. A

secondary source may include more data about the industrial revolution than primary sources.

These sources of information act as a way of keeping us with or discussing progress in the field

of study, wherein a researcher may use observations of another on a particular topic to

summarize his viewpoints on the industrial revolution (Pavlov, 2019). The secondary source of

information includes streaming video, newspaper articles, online journal articles, and books. The

secondary data are available readily from other sources hence there are no particular methods of

collection. The secondary sources of data can be both qualitative and quantitative. The

quantitative data can be acquired through transcripts, interviews, diaries, and newspapers.

Case Study of the First Industrial Revolution in Britain

The industrial revolution was confined largely to Britain in the period 1760 to 1830. The British

prohibited the exportation of manufacturing techniques, skilled workers, and machinery. The

monopoly of Britain could not last longer especially since some Britons saw some industrial

opportunities abroad that were profitable, while continental European businessmen sought to lure

the capability of the British to their countries (ALLEN, 2011). Two Englishmen, Joh Cockerill,

and William brought the industrial revolution to Belgium through the development of machine

shops in 1807. Belgium became the first country in the European continent to be economically

transformed (PARK, 2018). The government policies in England toward commerce and property

promoted the spread of global trade and innovation.

true essence, investigate and explore the role of energy in the industrial revolution in Britain

through detailed contextual analysis.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources of data consist of information that has been collected and normally

interpreted by other researchers and then recorded in articles, books, and other publications. A

secondary source may include more data about the industrial revolution than primary sources.

These sources of information act as a way of keeping us with or discussing progress in the field

of study, wherein a researcher may use observations of another on a particular topic to

summarize his viewpoints on the industrial revolution (Pavlov, 2019). The secondary source of

information includes streaming video, newspaper articles, online journal articles, and books. The

secondary data are available readily from other sources hence there are no particular methods of

collection. The secondary sources of data can be both qualitative and quantitative. The

quantitative data can be acquired through transcripts, interviews, diaries, and newspapers.

Case Study of the First Industrial Revolution in Britain

The industrial revolution was confined largely to Britain in the period 1760 to 1830. The British

prohibited the exportation of manufacturing techniques, skilled workers, and machinery. The

monopoly of Britain could not last longer especially since some Britons saw some industrial

opportunities abroad that were profitable, while continental European businessmen sought to lure

the capability of the British to their countries (ALLEN, 2011). Two Englishmen, Joh Cockerill,

and William brought the industrial revolution to Belgium through the development of machine

shops in 1807. Belgium became the first country in the European continent to be economically

transformed (PARK, 2018). The government policies in England toward commerce and property

promoted the spread of global trade and innovation.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 6

The government implemented patent laws that enabled investors to benefit financially from the

intellectual properties of their inventions. The coal and iron deposits were also abundant in Great

Britain and proved significant to the growth of all new machines made of steel or iron and coal

powered like the machinery and locomotive powered by steam (Tomory, 2016). As the England

population grew, more workers needed and were willing to buy textile goods. The cottage

industry showed how much individuals could produce in their homes through spinning and

weaving cloth by hand. However, this system of domestic production could not maintain the

increasing demands of the growing population of England. Various innovations shifted the

production of textile to a new system of factory.

Case Study on Just Transition in South Africa

Just transition is a framework developed by the movement of a trade union to include various

social interventions required to secure the livelihoods and rights of workers when economies are

shifting to sustainability in production, majorly protecting biodiversity and climate change. The

standards are set when setting climate goals for a clean economy (Widana, 2019). During the

process, sectors like forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, and energy which employ workers

must restructure. There were growing concerns that periods of structural economic change in the

past have left ordinary communities, families, and workers to bear the transition cost to the new

wealth production methods, resulting in exclusion for workers, poverty, and also unemployment.

A state-owned South African electricity utility known as Eskom announced the imminent closure

five of its power stations fired by coal in early 2017. The declaration sparked a strong reaction

from public debate and trade unions about how changes in the energy system of South Africa

will affect communities and workers (Balmer, 2017). There are policy mechanisms that already

exist in South Africa that could be used to reduce the negative impacts of a coal transition on

The government implemented patent laws that enabled investors to benefit financially from the

intellectual properties of their inventions. The coal and iron deposits were also abundant in Great

Britain and proved significant to the growth of all new machines made of steel or iron and coal

powered like the machinery and locomotive powered by steam (Tomory, 2016). As the England

population grew, more workers needed and were willing to buy textile goods. The cottage

industry showed how much individuals could produce in their homes through spinning and

weaving cloth by hand. However, this system of domestic production could not maintain the

increasing demands of the growing population of England. Various innovations shifted the

production of textile to a new system of factory.

Case Study on Just Transition in South Africa

Just transition is a framework developed by the movement of a trade union to include various

social interventions required to secure the livelihoods and rights of workers when economies are

shifting to sustainability in production, majorly protecting biodiversity and climate change. The

standards are set when setting climate goals for a clean economy (Widana, 2019). During the

process, sectors like forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, and energy which employ workers

must restructure. There were growing concerns that periods of structural economic change in the

past have left ordinary communities, families, and workers to bear the transition cost to the new

wealth production methods, resulting in exclusion for workers, poverty, and also unemployment.

A state-owned South African electricity utility known as Eskom announced the imminent closure

five of its power stations fired by coal in early 2017. The declaration sparked a strong reaction

from public debate and trade unions about how changes in the energy system of South Africa

will affect communities and workers (Balmer, 2017). There are policy mechanisms that already

exist in South Africa that could be used to reduce the negative impacts of a coal transition on

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 7

communities and workers. Tracking and recognizing their limitations is a significant step to

effectively using them in planning for closures of coal. The National Planning Commission has

initiated a dialogue of stakeholders on the pathway for a just transition that explores ways of

addressing the sustainability of the environment and ensure an equitable transition to an

economy of low-carbon. The NPC intends to build a shred agenda and vision between four social

partners, namely business, civil society, labor, and government.

The South African government is also encouraging a just transition to an economy of low carbon

through Sector Job Resilience Plans (SJRPs) and National Employment Vulnerability

Assessment (NEVA). The NEVA assesses the impacts on climate change responses and jobs of

climate change by location and sector to understand what the interventions related to job may be

needed and where they are needed as stipulated in the National Climate Change Response White

Paper (Widana, 2019). The Social and Labor Plans (SLPs) are expected to play a significant role

in the planning of the coal transition. An SLP which is a requirement of licensing for operations

of mining is a document that illustrates how mining companies plan to share some of the benefits

from the operations of mining with communities around. This document tackles social conflict

related to mining in South Africa and to support developments integrated locally.

ANALYSIS

Role of Energy in Industrial Revolution

The sources of energy during the industrial revolution made a significant impact historically and

resulted in a transition that would environmentally and technologically change the world.

Although the effects of the transition could not be realized fully until many years later, they

pushed the world in the right direction through of technology, distribution, and production (Stern

& Rydge, 2012). Only a smaller percentage of resources were used as sources of energy during

communities and workers. Tracking and recognizing their limitations is a significant step to

effectively using them in planning for closures of coal. The National Planning Commission has

initiated a dialogue of stakeholders on the pathway for a just transition that explores ways of

addressing the sustainability of the environment and ensure an equitable transition to an

economy of low-carbon. The NPC intends to build a shred agenda and vision between four social

partners, namely business, civil society, labor, and government.

The South African government is also encouraging a just transition to an economy of low carbon

through Sector Job Resilience Plans (SJRPs) and National Employment Vulnerability

Assessment (NEVA). The NEVA assesses the impacts on climate change responses and jobs of

climate change by location and sector to understand what the interventions related to job may be

needed and where they are needed as stipulated in the National Climate Change Response White

Paper (Widana, 2019). The Social and Labor Plans (SLPs) are expected to play a significant role

in the planning of the coal transition. An SLP which is a requirement of licensing for operations

of mining is a document that illustrates how mining companies plan to share some of the benefits

from the operations of mining with communities around. This document tackles social conflict

related to mining in South Africa and to support developments integrated locally.

ANALYSIS

Role of Energy in Industrial Revolution

The sources of energy during the industrial revolution made a significant impact historically and

resulted in a transition that would environmentally and technologically change the world.

Although the effects of the transition could not be realized fully until many years later, they

pushed the world in the right direction through of technology, distribution, and production (Stern

& Rydge, 2012). Only a smaller percentage of resources were used as sources of energy during

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 8

this duration, but the new resources and inventions discovered during the industrial revolution

were the significant features that made it a defining period.

The steam engines were invented in 1705 and were used majorly for pumping water out of coal

mines which flooded much of the season. However, it could produce energy. After the

improvement of the steam engines between the 1780s and 1760s, they could produce power, and

coal could be burned to propel machinery (Stern & Kander, 2012). This marked the beginning of

the railroads, with the steam engine development. The scarcity of trees for lumber resulted in the

popularity of coal especially in England, where coal was abundant (Mathews, Kidney, Mallon, &

Hughes, 2010). The early uses of wood, water, and wind for energy were substituted by coal,

which could generate high heat levels, operate much efficient machines and slowly replace

manual labor.

Coal seems to have started the revolution itself, resulting into a faster production pace for the

world. Coal was suitable due to the abundance of this resource and could be utilized in its natural

form. Wood was the major resource used for the generation of energy before the industrial

revolution, however, this resource became scarce hence other resources had to be found

(Majumdar, 2013). Lumber was becoming difficult to encounter and was not quickly renewable

sufficiently to supply its demand. Hence, charcoals also could not be abundantly used since they

are made from woods that are burned down into charcoal.

Many geographers, economic historians, ecological, and energy economists believe that the

growth in the quality and supply of energy and energy-related innovations play a significant role

in economic growth and also a significant component in explaining the industrial revolution. The

transition to the current growth regime begins when the change in technology first makes the

operation of the current technology profitable (MATHEWS, 2010). After sometimes, the

this duration, but the new resources and inventions discovered during the industrial revolution

were the significant features that made it a defining period.

The steam engines were invented in 1705 and were used majorly for pumping water out of coal

mines which flooded much of the season. However, it could produce energy. After the

improvement of the steam engines between the 1780s and 1760s, they could produce power, and

coal could be burned to propel machinery (Stern & Kander, 2012). This marked the beginning of

the railroads, with the steam engine development. The scarcity of trees for lumber resulted in the

popularity of coal especially in England, where coal was abundant (Mathews, Kidney, Mallon, &

Hughes, 2010). The early uses of wood, water, and wind for energy were substituted by coal,

which could generate high heat levels, operate much efficient machines and slowly replace

manual labor.

Coal seems to have started the revolution itself, resulting into a faster production pace for the

world. Coal was suitable due to the abundance of this resource and could be utilized in its natural

form. Wood was the major resource used for the generation of energy before the industrial

revolution, however, this resource became scarce hence other resources had to be found

(Majumdar, 2013). Lumber was becoming difficult to encounter and was not quickly renewable

sufficiently to supply its demand. Hence, charcoals also could not be abundantly used since they

are made from woods that are burned down into charcoal.

Many geographers, economic historians, ecological, and energy economists believe that the

growth in the quality and supply of energy and energy-related innovations play a significant role

in economic growth and also a significant component in explaining the industrial revolution. The

transition to the current growth regime begins when the change in technology first makes the

operation of the current technology profitable (MATHEWS, 2010). After sometimes, the

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 9

contemporary sector develops and the traditional sectors decline as capital flow to the modern

sector to the traditional sector. The change from an economy that depended on land resource to

an economy based on fossil fuel is significant to the industrial revolution and could illustrate the

differential growth of the British and Dutch economies (VRIES, 2011). Both countries have the

relevant institutions for the industrial revolution to occur but the accumulation of capital in the

Netherlands faced a constraint in renewable energy resources, while in domestic coal mines of

Britain in combination with steam engines, provided a solution from the constraint.

Early in the industrial revolution, the coal transport had to be done by the use of conventional

energy carriers, such as horse carriage, and the cost implications are high, however, the coal-

using steam engine adoption for transportation purposes lowered the costs of trading and the

industrial revolution spread to other countries and regions (Landers, 2012).

The Just Transition

The transition to an economy that is carbon neutral will affect every aspect of the movement,

consumption, services provision, and goods production. This means that the greenhouse gas

intensity compared to the current pledges and past achievements must be improved with

consequently harsher employment and social impacts than what has been experienced so far

(Heffron & McCauley, 2018). This will result in major opportunities, costs, adjustments, and

changes and will affect job prospects, skills, working conditions, livelihoods, and jobs

considerably. Just transition can be defined as a framework developed by the movement of trade

unions to include various social interventions required to secure the livelihoods and rights of

workers when economies are shifting to sustainability in production, majorly protecting

biodiversity and climate change (Newell & Mulvaney, 2013).

contemporary sector develops and the traditional sectors decline as capital flow to the modern

sector to the traditional sector. The change from an economy that depended on land resource to

an economy based on fossil fuel is significant to the industrial revolution and could illustrate the

differential growth of the British and Dutch economies (VRIES, 2011). Both countries have the

relevant institutions for the industrial revolution to occur but the accumulation of capital in the

Netherlands faced a constraint in renewable energy resources, while in domestic coal mines of

Britain in combination with steam engines, provided a solution from the constraint.

Early in the industrial revolution, the coal transport had to be done by the use of conventional

energy carriers, such as horse carriage, and the cost implications are high, however, the coal-

using steam engine adoption for transportation purposes lowered the costs of trading and the

industrial revolution spread to other countries and regions (Landers, 2012).

The Just Transition

The transition to an economy that is carbon neutral will affect every aspect of the movement,

consumption, services provision, and goods production. This means that the greenhouse gas

intensity compared to the current pledges and past achievements must be improved with

consequently harsher employment and social impacts than what has been experienced so far

(Heffron & McCauley, 2018). This will result in major opportunities, costs, adjustments, and

changes and will affect job prospects, skills, working conditions, livelihoods, and jobs

considerably. Just transition can be defined as a framework developed by the movement of trade

unions to include various social interventions required to secure the livelihoods and rights of

workers when economies are shifting to sustainability in production, majorly protecting

biodiversity and climate change (Newell & Mulvaney, 2013).

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 10

During the process of just transition, sectors like forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, and energy

which employ workers must restructure their organization. It is believed that during structural

economic change in the past, ordinary communities, families, and workers were left to bear the

cost of transition which resulted into poverty and unemployment (Goddard & Farrelly, 218).

Uniting climate and social justice through just transition means to conform with demands for

fairness for workers in coal mines in developing countries that are coal-dependent who lack

opportunities of employment beyond coal; fairness for populations affected by wider

environmental impacts and air pollution of coal use; fairness for those having to depart their

homes due to rise of sea levels and engulf islands and coastal regions; fairness for workers in

economies emerging that demand their share of the industrialization dividend (Zhavoronkova &

Shpakovskiy, 2019).

For trade unions, the just transition illustrates the transition towards an economy of low-carbon

and resilience to climate that optimizes the importance of climate action while reducing

hardships for community and workers (Torres, 2019). Some of the policies that can be applied in

different countries include local economic diversification plans that provide community stability

and support decent work, social protection along with policies of active labor market, early

assessment, and research of the employment and social effects of climate policies, democratic

consultation and social dialogue of social partners such as communities, employers, and trade

unions, and sound investments in job-rich and sectors and low-emission technologies.

Industrial Revolution and Just Transition

Coal was the major resource used in the generation of power during the industrial revolution.

The shortage of trees for lumber resulted in the popularity of coal especially in England, where

coal was abundant. The just transition call for the need to decarbonize the economy through

During the process of just transition, sectors like forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, and energy

which employ workers must restructure their organization. It is believed that during structural

economic change in the past, ordinary communities, families, and workers were left to bear the

cost of transition which resulted into poverty and unemployment (Goddard & Farrelly, 218).

Uniting climate and social justice through just transition means to conform with demands for

fairness for workers in coal mines in developing countries that are coal-dependent who lack

opportunities of employment beyond coal; fairness for populations affected by wider

environmental impacts and air pollution of coal use; fairness for those having to depart their

homes due to rise of sea levels and engulf islands and coastal regions; fairness for workers in

economies emerging that demand their share of the industrialization dividend (Zhavoronkova &

Shpakovskiy, 2019).

For trade unions, the just transition illustrates the transition towards an economy of low-carbon

and resilience to climate that optimizes the importance of climate action while reducing

hardships for community and workers (Torres, 2019). Some of the policies that can be applied in

different countries include local economic diversification plans that provide community stability

and support decent work, social protection along with policies of active labor market, early

assessment, and research of the employment and social effects of climate policies, democratic

consultation and social dialogue of social partners such as communities, employers, and trade

unions, and sound investments in job-rich and sectors and low-emission technologies.

Industrial Revolution and Just Transition

Coal was the major resource used in the generation of power during the industrial revolution.

The shortage of trees for lumber resulted in the popularity of coal especially in England, where

coal was abundant. The just transition call for the need to decarbonize the economy through

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 11

close of the core-fire power plants because of climate change which was constructed during the

industrial revolution (Evans & Phelan, 2016). The industrial revolution resulted in the

employment of many workers in coal mines and core-fired power plants, however, the just

transition seeks to close these coal mines and power plants to prevent further environmental

degradation caused by the use of coal. The economic development promoted by the industrial

revolution was a result of infrastructural development especially in communities where the

industries were situated (Ciplet & Lindsey, 2019).

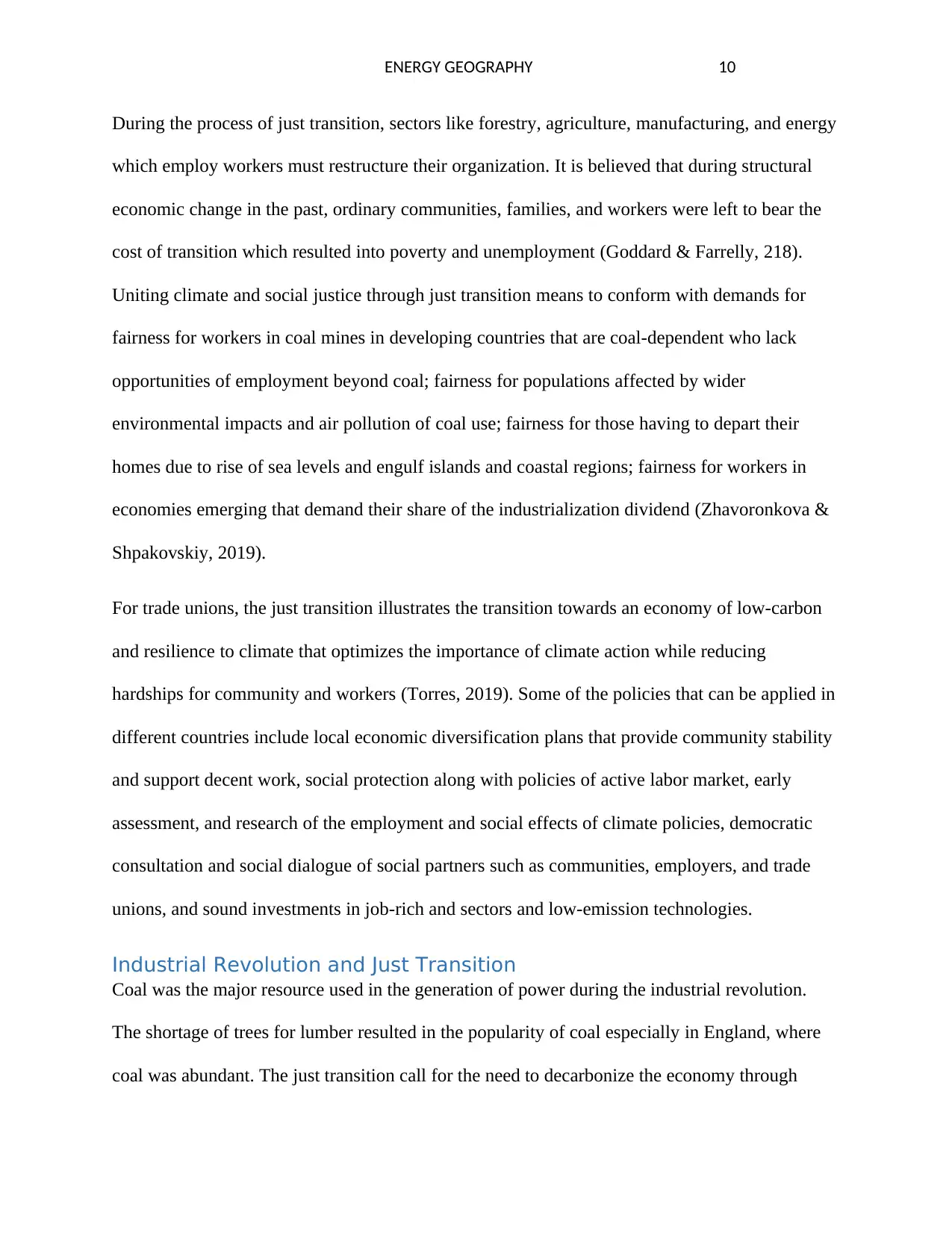

Figure 1: Global CO2 Emission Pathways (Evans & Phelan, 2016)

The industrial development will slow the industrial development since coal mines and companies

dependent on coal-fired power will have to seek alternatives. The lessons learned from the

industrial revolution include, there is need of thorough evaluation on long-term effects of energy

sources before they are implemented, environmental sustainability should be the first factor

when determining sources of energy, and lastly there is need of diversification of energy sources

to prevent over-reliance of a particular source of energy (Zadek, 2018).

close of the core-fire power plants because of climate change which was constructed during the

industrial revolution (Evans & Phelan, 2016). The industrial revolution resulted in the

employment of many workers in coal mines and core-fired power plants, however, the just

transition seeks to close these coal mines and power plants to prevent further environmental

degradation caused by the use of coal. The economic development promoted by the industrial

revolution was a result of infrastructural development especially in communities where the

industries were situated (Ciplet & Lindsey, 2019).

Figure 1: Global CO2 Emission Pathways (Evans & Phelan, 2016)

The industrial development will slow the industrial development since coal mines and companies

dependent on coal-fired power will have to seek alternatives. The lessons learned from the

industrial revolution include, there is need of thorough evaluation on long-term effects of energy

sources before they are implemented, environmental sustainability should be the first factor

when determining sources of energy, and lastly there is need of diversification of energy sources

to prevent over-reliance of a particular source of energy (Zadek, 2018).

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 12

Just Transition in South Africa

This section evaluates some of the major issues that should be thought through and discussed as

part of ensuring a just transition. The institutional arrangements, knowledge gaps, potential

economic development alternatives, and the political and economic impacts of a coal decline.

Coal in South Africa

South Africa currently depends on coal to produce 92% of its electrical energy and to generate

approximately 20% of its liquid fuel. Consequently, the chemical firm Sasol and public utility

Eskom together account for more than 50% of the greenhouse gas emission in South Africa and

85% by volume of coal used in the market locally (Balmer, 2017). In 2017, Coal is one of the

largest exports of South Africa by value accounting for approximately US$4.6 billion. The

Eskom employs about 50,000 workers in its fleet of majorly coal-fired power stations and the

sector of coal mining employs about 82,000 workers. The sector has been praised into the

political economy of the country for decades, through enabling of electricity supply based on

cheap fuel input, corruption scandals, linkages to political powerful trade unions, local

corporations, wealth accumulation in foreign companies, and creation of jobs (Cock, Resistance

to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019).

Nevertheless, various changes in the global and domestic energy landscapes are changing the

South African’s role of coal. There is a need to start a conversation about what South Africa will

do after coal and how to best manage the transition to reduce economic and social identity and

disruptions and find new opportunities. First, the electrical energy system is experiencing

structural change already (Zieleniewski & Brent, 2017). Various plants of coal are attaining the

end of their operational lives and becoming too costly to run and maintain. Coal resources are

also depleting at existing mined while new mining basins face substantial infrastructural and

commercial challenges related to rail connections and water supply. There is also a decline in

Just Transition in South Africa

This section evaluates some of the major issues that should be thought through and discussed as

part of ensuring a just transition. The institutional arrangements, knowledge gaps, potential

economic development alternatives, and the political and economic impacts of a coal decline.

Coal in South Africa

South Africa currently depends on coal to produce 92% of its electrical energy and to generate

approximately 20% of its liquid fuel. Consequently, the chemical firm Sasol and public utility

Eskom together account for more than 50% of the greenhouse gas emission in South Africa and

85% by volume of coal used in the market locally (Balmer, 2017). In 2017, Coal is one of the

largest exports of South Africa by value accounting for approximately US$4.6 billion. The

Eskom employs about 50,000 workers in its fleet of majorly coal-fired power stations and the

sector of coal mining employs about 82,000 workers. The sector has been praised into the

political economy of the country for decades, through enabling of electricity supply based on

cheap fuel input, corruption scandals, linkages to political powerful trade unions, local

corporations, wealth accumulation in foreign companies, and creation of jobs (Cock, Resistance

to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019).

Nevertheless, various changes in the global and domestic energy landscapes are changing the

South African’s role of coal. There is a need to start a conversation about what South Africa will

do after coal and how to best manage the transition to reduce economic and social identity and

disruptions and find new opportunities. First, the electrical energy system is experiencing

structural change already (Zieleniewski & Brent, 2017). Various plants of coal are attaining the

end of their operational lives and becoming too costly to run and maintain. Coal resources are

also depleting at existing mined while new mining basins face substantial infrastructural and

commercial challenges related to rail connections and water supply. There is also a decline in

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 13

global demand for coal which could reduce the exports of South Africa because of the

decarbonization of coal by the European Union.

Life After Coal

As the production of coal reduces, regional economic developments and jobs will require

attention. Substantial fluctuations in the power and mining sectors are also expected to have

consequences on the political landscape of South Africa. Provided the various dimensions, the

coal transition should not only be a matter of concern that is isolated for the Mineral Resources

and Environmental Affairs departments but rather a common challenge that is tackled across

various ministries and different government levels (Ezeokoli, Bezuidenhout, Maboeta, & Khasa,

2020).

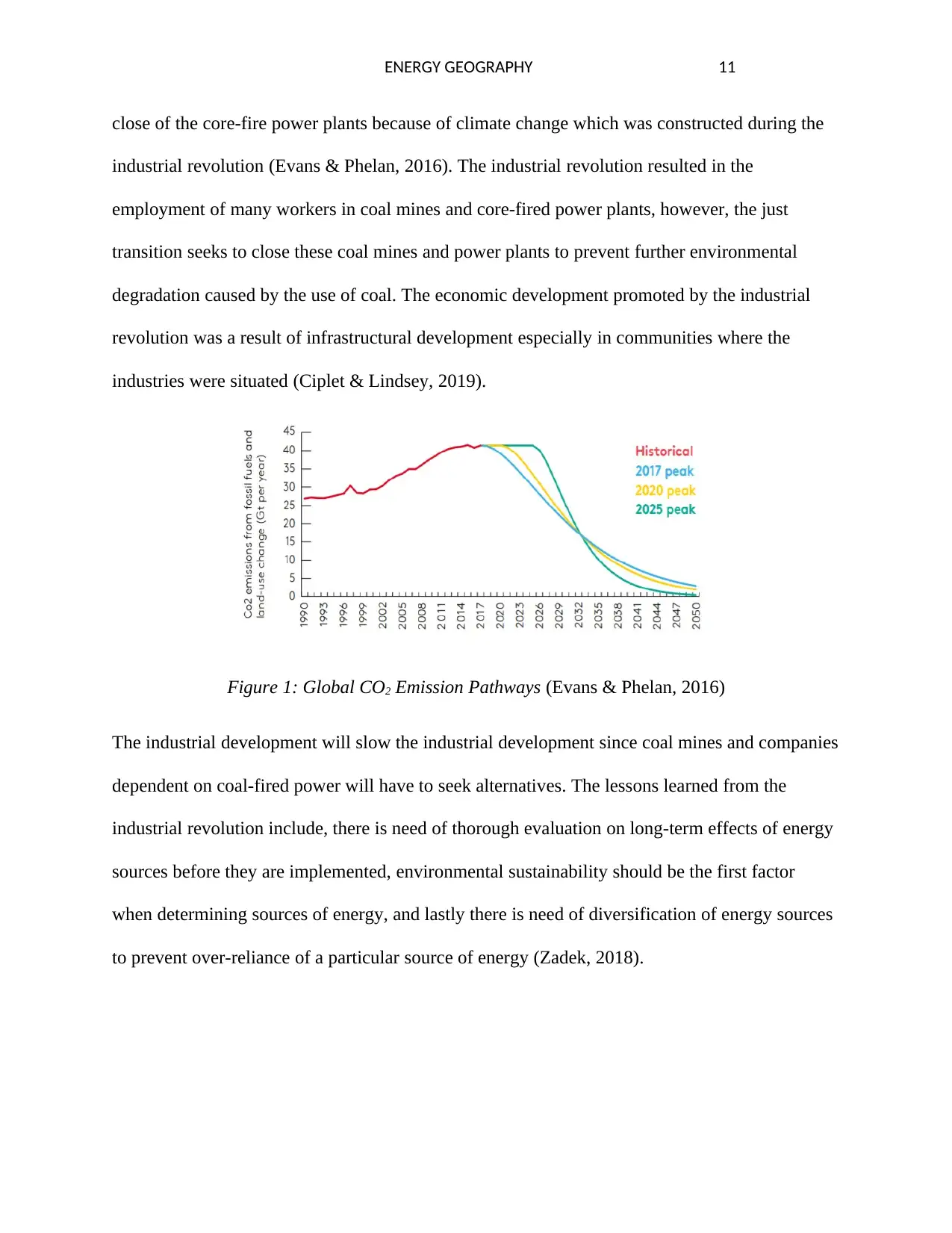

Employments

The employment in coal mines in South Africa trended downwards mostly as the sector became

more intensive in terms of capital after peaking in the early 1980s. Digitalization and automation

are anticipated to shrink further the workforce over the decades coming, reflecting global trends.

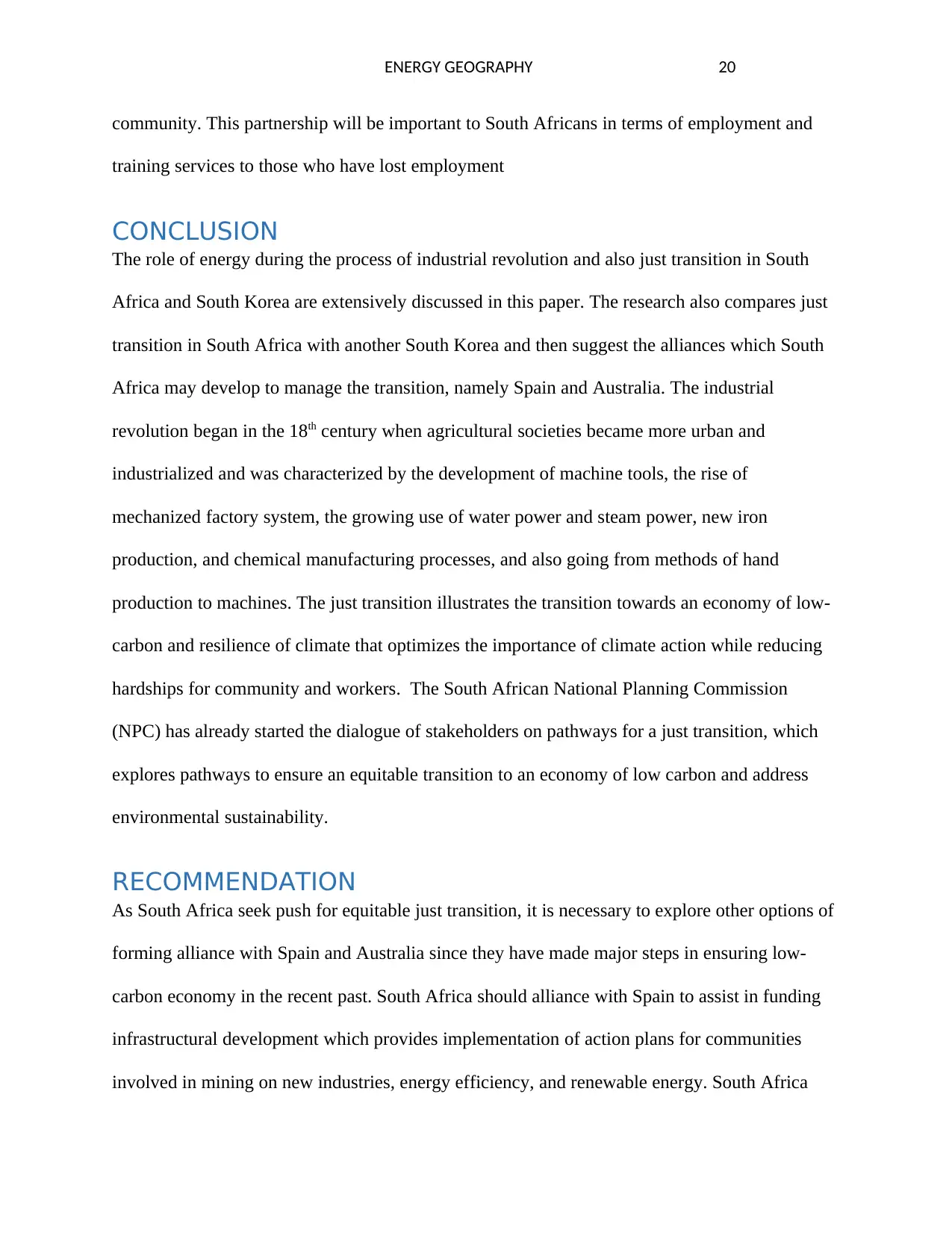

Figure 1: Projected and historical coal mining employment under future energy circumstances

(Zieleniewski & Brent, 2017)

global demand for coal which could reduce the exports of South Africa because of the

decarbonization of coal by the European Union.

Life After Coal

As the production of coal reduces, regional economic developments and jobs will require

attention. Substantial fluctuations in the power and mining sectors are also expected to have

consequences on the political landscape of South Africa. Provided the various dimensions, the

coal transition should not only be a matter of concern that is isolated for the Mineral Resources

and Environmental Affairs departments but rather a common challenge that is tackled across

various ministries and different government levels (Ezeokoli, Bezuidenhout, Maboeta, & Khasa,

2020).

Employments

The employment in coal mines in South Africa trended downwards mostly as the sector became

more intensive in terms of capital after peaking in the early 1980s. Digitalization and automation

are anticipated to shrink further the workforce over the decades coming, reflecting global trends.

Figure 1: Projected and historical coal mining employment under future energy circumstances

(Zieleniewski & Brent, 2017)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 14

Even without policy implementation to minimize the emissions of greenhouse gas, the

employment will reduce as mines and power plants reach the ends of times unless the lives of old

mines are extended or huge subsidies are issues to the sector to develop new plants of coal-fired

power (Moroeng, Wagner, Brand, & Roberts, 2018). Facing potentially rapid reduction in

employment in the coal sectors, trade unions have been called for a just transition for coal

communities and coal workers, highlighting the need of creating decent and alternative

opportunities for employment in the regions affected. A credible and clear plan regarding jobs is

significant to ensure communities, coal workers, and unions are part of the transition and not left

behind.

Regional Economic Developments

The major sectors contributing to the gross added value of South Africa are agriculture,

construction, manufacturing, and mining. Coal mining has also created revenues in the sector of

transport and employment. Rail and trucking transport of coal has increased over the last 10 year

both for delivery of power plants of Eskom and for export (Moroeng, Wagner, Brand, & Roberts,

2018). The other economic sectors that benefit from linkages with coal mining include business,

financial, and machinery services. South African mining companies also sometimes fund

services that are generally provided by local governments like sanitation, water, and housing.

Therefore, any decline in production could result in substantial economic and social upheaval in

case such impacts are not managed and understood carefully.

Political Impacts

There could be substantial political consequences of the decline in coal, specifically one that is

not managed properly. It is an already anxious socio-economic context, some fear that failing to

provide opportunities for communities and employees affected by failing to implement transition

policies could result in violence and further exclusion. Another significant political factor is that

Even without policy implementation to minimize the emissions of greenhouse gas, the

employment will reduce as mines and power plants reach the ends of times unless the lives of old

mines are extended or huge subsidies are issues to the sector to develop new plants of coal-fired

power (Moroeng, Wagner, Brand, & Roberts, 2018). Facing potentially rapid reduction in

employment in the coal sectors, trade unions have been called for a just transition for coal

communities and coal workers, highlighting the need of creating decent and alternative

opportunities for employment in the regions affected. A credible and clear plan regarding jobs is

significant to ensure communities, coal workers, and unions are part of the transition and not left

behind.

Regional Economic Developments

The major sectors contributing to the gross added value of South Africa are agriculture,

construction, manufacturing, and mining. Coal mining has also created revenues in the sector of

transport and employment. Rail and trucking transport of coal has increased over the last 10 year

both for delivery of power plants of Eskom and for export (Moroeng, Wagner, Brand, & Roberts,

2018). The other economic sectors that benefit from linkages with coal mining include business,

financial, and machinery services. South African mining companies also sometimes fund

services that are generally provided by local governments like sanitation, water, and housing.

Therefore, any decline in production could result in substantial economic and social upheaval in

case such impacts are not managed and understood carefully.

Political Impacts

There could be substantial political consequences of the decline in coal, specifically one that is

not managed properly. It is an already anxious socio-economic context, some fear that failing to

provide opportunities for communities and employees affected by failing to implement transition

policies could result in violence and further exclusion. Another significant political factor is that

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 15

a declining coal workforce denotes to the trade unions (Wang, 2013). A dramatic fall in the

production of coal poses a threat of existence to some sections of the trade union movements.

Institutions for Just Transition

There are already policy mechanisms existing in South Africa that could be applied in mitigating

the negative impacts of the transition of coal on communities and workers. Tackling and

recognizing their limitations is a significant step in effectively using them in planning for

closures of coal. The National Planning Commission (NPC) has already started the dialogue of

stakeholders on pathways for a just transition, which explores pathways to ensure an equitable

transition to an economy of low carbon and address environmental sustainability (Cock,

Resistance to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019).

The NPC seeks to implement a shared agenda and vision between four social partners namely

business, civil society, labor, and government. While this process is significant in supporting the

transition of low carbon in South Africa, it is unlikely to be granular sufficiently to manage the

transition of coal transition on its own.

The process stresses the complex problem of government coordination between and within the

departments with competing capacities and agendas to act. The Just Transition Dialogue of NPC,

however, represents a major effort to start thinking about the transition of coal (Cock, Resistance

to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019). The various

actors involved in the process also shows that a transition of low-carbon is a subject that is

relevant for all sectors of society. Something that is also effective for coal transition particularly.

Despite its limited constituency and broad scope, the dialogue can provide some significant

space and direction to discuss the various challenges related to the decline in coal.

a declining coal workforce denotes to the trade unions (Wang, 2013). A dramatic fall in the

production of coal poses a threat of existence to some sections of the trade union movements.

Institutions for Just Transition

There are already policy mechanisms existing in South Africa that could be applied in mitigating

the negative impacts of the transition of coal on communities and workers. Tackling and

recognizing their limitations is a significant step in effectively using them in planning for

closures of coal. The National Planning Commission (NPC) has already started the dialogue of

stakeholders on pathways for a just transition, which explores pathways to ensure an equitable

transition to an economy of low carbon and address environmental sustainability (Cock,

Resistance to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019).

The NPC seeks to implement a shared agenda and vision between four social partners namely

business, civil society, labor, and government. While this process is significant in supporting the

transition of low carbon in South Africa, it is unlikely to be granular sufficiently to manage the

transition of coal transition on its own.

The process stresses the complex problem of government coordination between and within the

departments with competing capacities and agendas to act. The Just Transition Dialogue of NPC,

however, represents a major effort to start thinking about the transition of coal (Cock, Resistance

to coal inequalities and the possibilities of a just transition in South Africa, 2019). The various

actors involved in the process also shows that a transition of low-carbon is a subject that is

relevant for all sectors of society. Something that is also effective for coal transition particularly.

Despite its limited constituency and broad scope, the dialogue can provide some significant

space and direction to discuss the various challenges related to the decline in coal.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 16

Just Transition in South Korea

The phase-out of the Coal-fired power station is spreading around the world with the launch of

the 2020 New Climate Regime. Coal phase-out is getting more support in the Republic of Korea

where nuclear and coal-fired power generation has been favored for long because of cost-

efficiency. However, evolving perspectives that the nuclear and coal fires power generation

causes abnormal weather conditions, health problems, and environmental degradation, the new

government inaugurated of the Republic of Korea has promised to cancel the plan for adding

more coal plants and is planning complete closure if coal plans (Lee, Injeong, & Woong, 2015).

During the last nine years of conservative rule, the energy policy of South Korea has been aimed

at restructuring so as to meet the interest of privatization or corporations. The result has been the

massive profits for corporations, the expansion of liquefied natural gas generation, and private

coal and nuclear power. The energy policy has been considered to be anti-climate and

undemocratic (Hyo-Jin, Ju-Hee, & Hoon, 2018). With South Korea not facing air contamination

with fine dust and earthquake threats, it is only natural that the energy workers who fought for

about two decades to protect the public energy system and stop privatization would lead in the

fight for a just energy transition. Provided the scale on which a just transition must take place, it

is predictable that many conflicts will occur among the different involved stakeholders. The best

path for transition is that which apply justice standards based on public accountability,

happiness, and public safety.

Energy transition must not mean that all the burden is put on the workers through job cuts or

onto the public through increased gas process and electricity. Huge corporations which for many

decades have guaranteed profits and enjoyed gas prices while contributing to climate change

must pay their share of the costs (Chang & Hornstein, 2015). The most immediate aim of

Just Transition in South Korea

The phase-out of the Coal-fired power station is spreading around the world with the launch of

the 2020 New Climate Regime. Coal phase-out is getting more support in the Republic of Korea

where nuclear and coal-fired power generation has been favored for long because of cost-

efficiency. However, evolving perspectives that the nuclear and coal fires power generation

causes abnormal weather conditions, health problems, and environmental degradation, the new

government inaugurated of the Republic of Korea has promised to cancel the plan for adding

more coal plants and is planning complete closure if coal plans (Lee, Injeong, & Woong, 2015).

During the last nine years of conservative rule, the energy policy of South Korea has been aimed

at restructuring so as to meet the interest of privatization or corporations. The result has been the

massive profits for corporations, the expansion of liquefied natural gas generation, and private

coal and nuclear power. The energy policy has been considered to be anti-climate and

undemocratic (Hyo-Jin, Ju-Hee, & Hoon, 2018). With South Korea not facing air contamination

with fine dust and earthquake threats, it is only natural that the energy workers who fought for

about two decades to protect the public energy system and stop privatization would lead in the

fight for a just energy transition. Provided the scale on which a just transition must take place, it

is predictable that many conflicts will occur among the different involved stakeholders. The best

path for transition is that which apply justice standards based on public accountability,

happiness, and public safety.

Energy transition must not mean that all the burden is put on the workers through job cuts or

onto the public through increased gas process and electricity. Huge corporations which for many

decades have guaranteed profits and enjoyed gas prices while contributing to climate change

must pay their share of the costs (Chang & Hornstein, 2015). The most immediate aim of

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 17

transition must be the provision of a reliable and safe supply of gas and electricity and a fair

repositioning of energy workers. These objectives can be attained if the energy industry is

reformed to operate as a public asset under public control, which would mistake caused by the

privatization led by business and conservative government interest over the past decade.

Globally, large energy corporations are the major obstacles to the policies of energy just

transition. Significantly, the energy trade unions, civil society and environmental organizations,

the public, National Assembly, and the government work together to derive a plan for democratic

over energy capital.

Institutions for Just Transition

The South Korean government has pledged to phase out nuclear and coal generation and increase

clean renewable energy and the government is currently moving towards enacting these

promises. Following a permanent closure of the Kori nuclear reactor in June 2019 and the

temporary shutdown of old coal-fired power plans. The government is now considering plans to

construct new nuclear reactors Kori 6 and 5 (Bellantuono, 2019). The Korean Public Service and

Transport Workers Union and the Korean Labor and Social Network on Energy have declared

their support for the policies and to play a leading role in bringing a just energy transition.

Policies

The major policies implemented by the South Korean government to facilitate coal phase-out

and just transition include market and regulatory settings to facilitate new investment,

community consensus, a mechanism for greater coal power predictability, predictable and stable

policy. Predictable and stable policy for carbon is a significant policy for guiding transition and

reduce financing costs (Lim, Edelenbos, & Gianoli, 2019). The mechanism for greater

predictability of coal power exit is important for timely replacement investments which will

replace the coal power from the market to avoid reliability concerns and unnecessary cost.

transition must be the provision of a reliable and safe supply of gas and electricity and a fair

repositioning of energy workers. These objectives can be attained if the energy industry is

reformed to operate as a public asset under public control, which would mistake caused by the

privatization led by business and conservative government interest over the past decade.

Globally, large energy corporations are the major obstacles to the policies of energy just

transition. Significantly, the energy trade unions, civil society and environmental organizations,

the public, National Assembly, and the government work together to derive a plan for democratic

over energy capital.

Institutions for Just Transition

The South Korean government has pledged to phase out nuclear and coal generation and increase

clean renewable energy and the government is currently moving towards enacting these

promises. Following a permanent closure of the Kori nuclear reactor in June 2019 and the

temporary shutdown of old coal-fired power plans. The government is now considering plans to

construct new nuclear reactors Kori 6 and 5 (Bellantuono, 2019). The Korean Public Service and

Transport Workers Union and the Korean Labor and Social Network on Energy have declared

their support for the policies and to play a leading role in bringing a just energy transition.

Policies

The major policies implemented by the South Korean government to facilitate coal phase-out

and just transition include market and regulatory settings to facilitate new investment,

community consensus, a mechanism for greater coal power predictability, predictable and stable

policy. Predictable and stable policy for carbon is a significant policy for guiding transition and

reduce financing costs (Lim, Edelenbos, & Gianoli, 2019). The mechanism for greater

predictability of coal power exit is important for timely replacement investments which will

replace the coal power from the market to avoid reliability concerns and unnecessary cost.

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 18

Market and regulatory settings are important to enable new investments which will replace the

coal-fired power with alternative energy sources such as hydrogen, batteries, and decentralized

energy sources.

Comparison between South Africa and the Korean Republic Just

Transition

South Africa South Korea

Dependency on

coal

South Africa currently depends on coal to

produce 92% of its electrical energy and to

generate approximately 20% of its liquid

fuel. Consequently, the chemical firm Sasol

and public utility Eskom together account

for more than 50% of the greenhouse gas

emission in South Africa and 85% by

volume of coal used in the market locally

Coal is the second major energy consumed in the

country after petroleum with a percentage of 29%.

60% of coal consumption is used majorly for

power generation and industrial production.

Environmental

effects of coal

The chemical firm Sasol and public utility

Eskom together account for more than 50%

of the greenhouse gas emission in South

Africa

The nuclear and coal fires power generation

causes abnormal weather conditions, health

problems, and environmental degradation

Preparation on life

after coal

The government is focusing on wind and

sun resources and also key commodities

namely cobalt, copper, nickel, palladium,

platinum, and vanadium to play a critical

role in the energy storage sector (Balmer,

2017).

Adoption of alternative sources of energy to

replace coal fires power majorly carbon capture

storage (CCS). By 2022, South Korea plans to

shut down ten old coal-fired power plants and

transform another 6 plants to LNG-fired power

plants.

Political impacts The decline in coal is an already anxious

socio-economic context, some fear that

failing to provide opportunities for

communities and employees affected by

failing to implement transition policies

could result in violence and further

exclusion

The political and societal perceptions of the role

of coal in the future energy mix are changing

since it was one of the major goals of the

administration to phase-out coal.

Institutions for a

just transition

The National Planning Commission (NPC)

has already started the dialogue of

stakeholders on pathways for a just

transition, which explores pathways to

ensure an equitable transition to an

economy of low carbon and address

environmental sustainability.

The Korean Public Service and Transport

Workers Union and the Korean Labor and Social

Network on Energy have declared their support

for the policies and to play a leading role in

bringing a just energy transition (Lee, Injeong, &

Woong, 2015).

Policies towards

Just transition

The Just Transition Dialogue policy was

adopted to build a shared agenda and vision

between four social partners namely

business, civil society, labor, and

government.

Market and regulatory settings to facilitate new

investment, community consensus, a mechanism

for greater coal power predictability, and also

predictable and stable policies

Steps taken towards

Just transition

Dialogue of Stakeholder on techniques for a

just transition has already been started to

Market and regulatory settings have been

implemented to enable new investments which

Market and regulatory settings are important to enable new investments which will replace the

coal-fired power with alternative energy sources such as hydrogen, batteries, and decentralized

energy sources.

Comparison between South Africa and the Korean Republic Just

Transition

South Africa South Korea

Dependency on

coal

South Africa currently depends on coal to

produce 92% of its electrical energy and to

generate approximately 20% of its liquid

fuel. Consequently, the chemical firm Sasol

and public utility Eskom together account

for more than 50% of the greenhouse gas

emission in South Africa and 85% by

volume of coal used in the market locally

Coal is the second major energy consumed in the

country after petroleum with a percentage of 29%.

60% of coal consumption is used majorly for

power generation and industrial production.

Environmental

effects of coal

The chemical firm Sasol and public utility

Eskom together account for more than 50%

of the greenhouse gas emission in South

Africa

The nuclear and coal fires power generation

causes abnormal weather conditions, health

problems, and environmental degradation

Preparation on life

after coal

The government is focusing on wind and

sun resources and also key commodities

namely cobalt, copper, nickel, palladium,

platinum, and vanadium to play a critical

role in the energy storage sector (Balmer,

2017).

Adoption of alternative sources of energy to

replace coal fires power majorly carbon capture

storage (CCS). By 2022, South Korea plans to

shut down ten old coal-fired power plants and

transform another 6 plants to LNG-fired power

plants.

Political impacts The decline in coal is an already anxious

socio-economic context, some fear that

failing to provide opportunities for

communities and employees affected by

failing to implement transition policies

could result in violence and further

exclusion

The political and societal perceptions of the role

of coal in the future energy mix are changing

since it was one of the major goals of the

administration to phase-out coal.

Institutions for a

just transition

The National Planning Commission (NPC)

has already started the dialogue of

stakeholders on pathways for a just

transition, which explores pathways to

ensure an equitable transition to an

economy of low carbon and address

environmental sustainability.

The Korean Public Service and Transport

Workers Union and the Korean Labor and Social

Network on Energy have declared their support

for the policies and to play a leading role in

bringing a just energy transition (Lee, Injeong, &

Woong, 2015).

Policies towards

Just transition

The Just Transition Dialogue policy was

adopted to build a shared agenda and vision

between four social partners namely

business, civil society, labor, and

government.

Market and regulatory settings to facilitate new

investment, community consensus, a mechanism

for greater coal power predictability, and also

predictable and stable policies

Steps taken towards

Just transition

Dialogue of Stakeholder on techniques for a

just transition has already been started to

Market and regulatory settings have been

implemented to enable new investments which

ENERGY GEOGRAPHY 19

explore the pathways to ensure an equitable

transition to an economy or low carbon and

to address environmental sustainability

will replace the coal-fired power with alternative

energy sources such as hydrogen, batteries, and

decentralized energy sources.

Alliances for Transition Management

There are various countries in which South Africa can alliance with so that the country can

develop suitable methods of managing the transition. The major countries that have outstanding

policies on just transition which can be emulated by South Africa to ensure effective coal phase-

out include Spain and Australia. The closure of coal mines in Spain has been accompanied by

strategies of transition that are funded for workers of varying ages, along with plans of

environmental rehabilitations that major on employment for former miners (Menéndez &

Loredo, 2019). South Africa should also alliance with Spain and close its coal mines and then

fund the workers or even offer an alternative employment to the workers. Spain is currently

funding infrastructure development which provides implementation of action plans for

communities involved in mining on new industries, energy efficiency, and renewable energy.

South Africa should alliance with Spain to assist in the implementation of these action plans for

communities involved in mining process on new industries, energy efficiency, and renewable

energy.

Australia has innovative governance arrangements that assist in coordinating the transition of

coal mining through its Latrobe Valley Authority which is a partnership between government,

industry, and community that invests in infrastructure improvements, facilitate new business

development and assist workers to access employment and training services (Goddard &

Farrelly, 218). South Africa should alliance with Australia to assist in innovative governance

arrangements which will involve a partnership between the government, industry, and

explore the pathways to ensure an equitable

transition to an economy or low carbon and

to address environmental sustainability

will replace the coal-fired power with alternative

energy sources such as hydrogen, batteries, and

decentralized energy sources.

Alliances for Transition Management

There are various countries in which South Africa can alliance with so that the country can

develop suitable methods of managing the transition. The major countries that have outstanding

policies on just transition which can be emulated by South Africa to ensure effective coal phase-

out include Spain and Australia. The closure of coal mines in Spain has been accompanied by

strategies of transition that are funded for workers of varying ages, along with plans of