Challenges Arising from COP21 Decision

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|23

|6057

|1

AI Summary

This article discusses the challenges that arose from the COP21 decision and its impact on global climate change efforts. It also explores the goals and mission of COP21 and the challenges faced in implementing the Paris Agreement.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Energy Sustainability 1

ENERGY SUSTAINABILITY

By (Name)

Course

Professor’s name

University name

City, State

Date of submission

ENERGY SUSTAINABILITY

By (Name)

Course

Professor’s name

University name

City, State

Date of submission

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Energy Sustainability 2

Abstract

The effort to ensure that energy sustainability has been achieved in the world is a debate that has

been going on since the 19th centuries. Kyoto protocol report was first initiated in the early 90s

before the United Nations framework Convention Climate Change was formed in 2015 as

COP21 held in Paris. This question seeks to understand the challenges that rose from COP21

decision. The second question concerns the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) which explains the

assessment of life cycle environmental, social and economic sustainability of the production of

shale gas and use. The assessment scope covers the United States and UK situations to estimate

the effects fracking activities has to the environment. The third question explains the political

and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measures in the housing and

transport sectors in Sweden, the United States and China. The forth question critically evaluates

the social, financial, and environmental impacts of developing renewable energy technologies in

the United States.

Abstract

The effort to ensure that energy sustainability has been achieved in the world is a debate that has

been going on since the 19th centuries. Kyoto protocol report was first initiated in the early 90s

before the United Nations framework Convention Climate Change was formed in 2015 as

COP21 held in Paris. This question seeks to understand the challenges that rose from COP21

decision. The second question concerns the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) which explains the

assessment of life cycle environmental, social and economic sustainability of the production of

shale gas and use. The assessment scope covers the United States and UK situations to estimate

the effects fracking activities has to the environment. The third question explains the political

and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measures in the housing and

transport sectors in Sweden, the United States and China. The forth question critically evaluates

the social, financial, and environmental impacts of developing renewable energy technologies in

the United States.

Energy Sustainability 3

Abstract........................................................................................................................................ 2

1.0 Challenges arising from COP21 decision............................................................................. 3

Introduction................................................................................................................................ 3

The goals and mission of COP21............................................................................................... 4

Challenges.................................................................................................................................. 4

2.0 Life cycle assessments of fracking activities in USA and UK............................................. 6

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………........6

Fracking Process..........................................................................................................................8

Results ………………………………………………………………………………………....8

Conclusion and Recommendation..............................................................................................9

3.0 Political and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measure in

the housing and transport sectors............................................................................................. 10

Sweden Case Study................................................................................................................... 10

Energy consumption in Sweden……………………………...…………………………… .10

Case Studies of UK………………………..………………………………………………… .12

China Case Study

…………………………………………………………………………………………………13

4.0 Impacts of developing renewable energy technologies...................................................... 15

Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 15

Environmental Impacts............................................................................................................. 16

Financial Impacts...................................................................................................................... 17

Social Impacts........................................................................................................................... 18

References ....................................................................................................................................19

1.0 Challenges arising from COP21 decision

Introduction

Abstract........................................................................................................................................ 2

1.0 Challenges arising from COP21 decision............................................................................. 3

Introduction................................................................................................................................ 3

The goals and mission of COP21............................................................................................... 4

Challenges.................................................................................................................................. 4

2.0 Life cycle assessments of fracking activities in USA and UK............................................. 6

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………........6

Fracking Process..........................................................................................................................8

Results ………………………………………………………………………………………....8

Conclusion and Recommendation..............................................................................................9

3.0 Political and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measure in

the housing and transport sectors............................................................................................. 10

Sweden Case Study................................................................................................................... 10

Energy consumption in Sweden……………………………...…………………………… .10

Case Studies of UK………………………..………………………………………………… .12

China Case Study

…………………………………………………………………………………………………13

4.0 Impacts of developing renewable energy technologies...................................................... 15

Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 15

Environmental Impacts............................................................................................................. 16

Financial Impacts...................................................................................................................... 17

Social Impacts........................................................................................................................... 18

References ....................................................................................................................................19

1.0 Challenges arising from COP21 decision

Introduction

Energy Sustainability 4

In 2015, 12th of December, 196 parties of the United Nations (UN) framework Convention on

Climate Change initiated in Paris Agreement. The legal binding was an international move to

combat the effects of climate change (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The signing of the

agreement culminated after six years close door meetings with the international leaders under the

support of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The

decision was reached after intense pressure from international leaders to avoid a repeat of

Copenhagen conference of 2009 (Dimitrov, 2010). The agreement came up with

recommendations of controlling the global warming. This required all parties in the convention

to formulate progressive climate targets which will be consistent to the global warming goal of

below 2 degrees Celsius (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). In a nutshell, the global treaty was meant to

strengthen the global response towards the threats of climate change. All parties are obliged to

contribute to the mitigation and adaptation measures that will help combat climate change

(Northrop & Ross, 2016). Countries were to contribute by developing plans and communicate

the same to the secretariat of the convention.

The goals and mission of COP21

In the Paris agreement, more emphasis was directed to the process rather than the

mitigation goals. The aim of the agreement depend on voluntary mitigation measures coupled

with a series of processes that are directed towards a common goal with a collective ambition in

mind unlike the Kyoto protocol that formulated specific targets. After the implementation and

decisions made in COP 21, what followed were a number of challenges that the parties had to

deal with and overcome them if the Paris Agreement goals were to be met (Roberts, 2015). The

first thing will be to reconcile the bad blood between Paris agreement top down goals and the

bottom up ambitions of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). In particular, the level

In 2015, 12th of December, 196 parties of the United Nations (UN) framework Convention on

Climate Change initiated in Paris Agreement. The legal binding was an international move to

combat the effects of climate change (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The signing of the

agreement culminated after six years close door meetings with the international leaders under the

support of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The

decision was reached after intense pressure from international leaders to avoid a repeat of

Copenhagen conference of 2009 (Dimitrov, 2010). The agreement came up with

recommendations of controlling the global warming. This required all parties in the convention

to formulate progressive climate targets which will be consistent to the global warming goal of

below 2 degrees Celsius (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). In a nutshell, the global treaty was meant to

strengthen the global response towards the threats of climate change. All parties are obliged to

contribute to the mitigation and adaptation measures that will help combat climate change

(Northrop & Ross, 2016). Countries were to contribute by developing plans and communicate

the same to the secretariat of the convention.

The goals and mission of COP21

In the Paris agreement, more emphasis was directed to the process rather than the

mitigation goals. The aim of the agreement depend on voluntary mitigation measures coupled

with a series of processes that are directed towards a common goal with a collective ambition in

mind unlike the Kyoto protocol that formulated specific targets. After the implementation and

decisions made in COP 21, what followed were a number of challenges that the parties had to

deal with and overcome them if the Paris Agreement goals were to be met (Roberts, 2015). The

first thing will be to reconcile the bad blood between Paris agreement top down goals and the

bottom up ambitions of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). In particular, the level

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Energy Sustainability 5

of emission reduction stipulated in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is not even

close to meet the mitigation goals of Paris Agreement (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

In this respect, it is critical to ensure the agreement review mechanism is effective.

Challenges

The effort injected in the treaty framework to ensure that there is transparency and

understanding among member states to gain the international support was another major setback.

In a new goal to develop climate finances form the developing countries to support the action of

UNFCCC (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The accounting modalities to set this

program running is still under discussion by the UNFCCC in order to formulate the best way

forward and find strategies of mobilizing these developing countries to take a drastic decision

towards supporting this initiative in order to save our planet with negotiations intended to be

achieved by 2025 (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). In the year 2015, OECD came up

with a climate policy initiative and proposed an estimate to support the progress of climate

finance as one of the major burning issues in COP21.

Paris Agreement on low emission should be consistent with the global emission with the

hope that emissions will fall from peak to zero or becoming negative in the half century to come

(Northrop & Ross, 2016). The sort, scale and pace of activities is likely to differ among and

across both developing and developed economies, however the stringency of the Paris

temperature goal is with the end goal that all nations will need to create and seek after low-

emanations improvement pathways, in the light of their diverse national circumstances and the

prospective IPCC extraordinary report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). 15 Major research, advancement and organization of imaginative new advances

will likewise be expected to accomplish these objectives (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). In spite of

of emission reduction stipulated in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is not even

close to meet the mitigation goals of Paris Agreement (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

In this respect, it is critical to ensure the agreement review mechanism is effective.

Challenges

The effort injected in the treaty framework to ensure that there is transparency and

understanding among member states to gain the international support was another major setback.

In a new goal to develop climate finances form the developing countries to support the action of

UNFCCC (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The accounting modalities to set this

program running is still under discussion by the UNFCCC in order to formulate the best way

forward and find strategies of mobilizing these developing countries to take a drastic decision

towards supporting this initiative in order to save our planet with negotiations intended to be

achieved by 2025 (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). In the year 2015, OECD came up

with a climate policy initiative and proposed an estimate to support the progress of climate

finance as one of the major burning issues in COP21.

Paris Agreement on low emission should be consistent with the global emission with the

hope that emissions will fall from peak to zero or becoming negative in the half century to come

(Northrop & Ross, 2016). The sort, scale and pace of activities is likely to differ among and

across both developing and developed economies, however the stringency of the Paris

temperature goal is with the end goal that all nations will need to create and seek after low-

emanations improvement pathways, in the light of their diverse national circumstances and the

prospective IPCC extraordinary report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). 15 Major research, advancement and organization of imaginative new advances

will likewise be expected to accomplish these objectives (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). In spite of

Energy Sustainability 6

ongoing sensational falls in the price of some key inexhaustible innovations, for example, solar

photovoltaic and wind16, advance in most of clean vitality technologies lags a long ways behind

what is expected to accomplish the Paris objectives.

The world faces a major challenge of meeting the food demands among its population while

combating, conserving biodiversity and adapting to climate change (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). A few types of land-based moderation activities, for example, monoculture

estates and utilizing area to develop original bio fuels can adversely affect biodiversity, the

accessibility and supply of nourishment and water and environment strength. Other relief

activities such as ecosystem-based methodologies (for example agro forestry and environment

reclamation) and atmosphere savvy horticulture can have positive advantages for both

biodiversity and human prosperity, while alleviating environmental change and improving

flexibility (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The opposition experiences among countries

when discussing about climate change gave birth to a new policy that will ensure every country

adopt certain strategies that will help in communally achieving sustainable development and

environmental conservation. These concerns were raised in COP21 held in Paris in 2015. During

the meeting other concerns were also raised which included;

Alleviating poverty through sustainable environment.

Engaging in discussions after which immediate actions are taken.

COP21 should be the back born of sustainable economy in the world and outlining its

benefits

ongoing sensational falls in the price of some key inexhaustible innovations, for example, solar

photovoltaic and wind16, advance in most of clean vitality technologies lags a long ways behind

what is expected to accomplish the Paris objectives.

The world faces a major challenge of meeting the food demands among its population while

combating, conserving biodiversity and adapting to climate change (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). A few types of land-based moderation activities, for example, monoculture

estates and utilizing area to develop original bio fuels can adversely affect biodiversity, the

accessibility and supply of nourishment and water and environment strength. Other relief

activities such as ecosystem-based methodologies (for example agro forestry and environment

reclamation) and atmosphere savvy horticulture can have positive advantages for both

biodiversity and human prosperity, while alleviating environmental change and improving

flexibility (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The opposition experiences among countries

when discussing about climate change gave birth to a new policy that will ensure every country

adopt certain strategies that will help in communally achieving sustainable development and

environmental conservation. These concerns were raised in COP21 held in Paris in 2015. During

the meeting other concerns were also raised which included;

Alleviating poverty through sustainable environment.

Engaging in discussions after which immediate actions are taken.

COP21 should be the back born of sustainable economy in the world and outlining its

benefits

Energy Sustainability 7

2.0 Life cycle assessments of fracking activities in USA and UK

Introduction

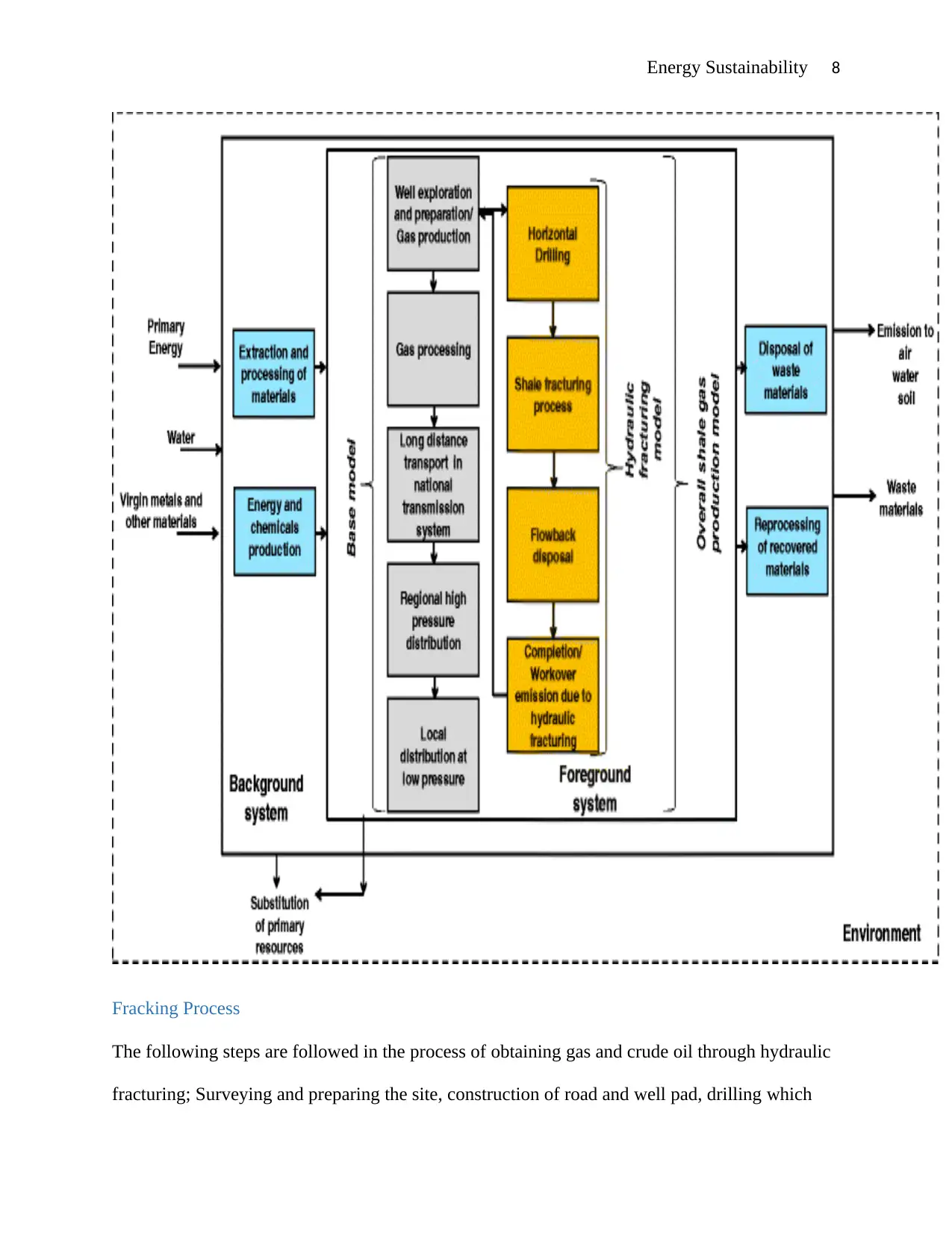

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) concerns the assessment of life cycle environmental, social

and economic sustainability of the production of shale gas and use. The scope of the assessment

covers United States and UK situations to estimate the effects fracking activities has to the

environment; the study also does a compares the effects of using traditional means to obtain gas

with fracking process (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). The centre stage of the study is on the effect on

water but also analysis will be done on the other factors. The study revolves around operations

that have received sharp criticism from environmental protection groups (Nhamo & Nhamo,

2016). The operations include flow back disposal and control of emissions. The main goal of

conducting Life cycle assessment is to identify the environmental impacts of a product on every

phase so as to find a means by which the effect can either be minimized or eliminated.

International Standard Organization (ISO) gives the standard of conformity when conducting a

Life Cycle Assessment (Northrop & Ross, 2016). The procedure consists of four steps;

Definition of goal and scope, Analysis of Inventory, assessment of Impact and then

Interpretation of the results. Below is a chart that looks into the process of fracking activities

both in the United States and U.K.

2.0 Life cycle assessments of fracking activities in USA and UK

Introduction

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) concerns the assessment of life cycle environmental, social

and economic sustainability of the production of shale gas and use. The scope of the assessment

covers United States and UK situations to estimate the effects fracking activities has to the

environment; the study also does a compares the effects of using traditional means to obtain gas

with fracking process (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). The centre stage of the study is on the effect on

water but also analysis will be done on the other factors. The study revolves around operations

that have received sharp criticism from environmental protection groups (Nhamo & Nhamo,

2016). The operations include flow back disposal and control of emissions. The main goal of

conducting Life cycle assessment is to identify the environmental impacts of a product on every

phase so as to find a means by which the effect can either be minimized or eliminated.

International Standard Organization (ISO) gives the standard of conformity when conducting a

Life Cycle Assessment (Northrop & Ross, 2016). The procedure consists of four steps;

Definition of goal and scope, Analysis of Inventory, assessment of Impact and then

Interpretation of the results. Below is a chart that looks into the process of fracking activities

both in the United States and U.K.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Energy Sustainability 8

Fracking Process

The following steps are followed in the process of obtaining gas and crude oil through hydraulic

fracturing; Surveying and preparing the site, construction of road and well pad, drilling which

Fracking Process

The following steps are followed in the process of obtaining gas and crude oil through hydraulic

fracturing; Surveying and preparing the site, construction of road and well pad, drilling which

Energy Sustainability 9

starts with vertical the horizontal, casing of the well, perforation, fracking, finalization and

production lastly either desertion or restoration of the site (Jenner and Lamadrid 2013). The

drilling process starts vertically, the direction which enables horizontal drilling which is line with

the process of forming the shale. Steel cases are inserted in the boreholes and cemented on the

rocks to hold the casing firmly (Hammond, O’Grady and Packham 2015 p. 2755). The casing on

the horizontal drilling is the perforated to pave way for the gas and crude oil. The next process is

fracking of the borehole using fracturing fluid which is driven through the horizontally drilled

hole to improve production. The fracking liquid is made up of water, chemicals and proppant.

99% of the fluid is water while the other percentages are a sorted chemicals and sand. The

completion phase involves recovery of the gas and abandoning of the site. Therefore, the study

looked into the impact of hydraulic fracturing activities as mentioned above and later

recommends the best practices to be undertaken in the production process by both the United

States and United Kingdom (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

Results

Poor waste water management practices lead to contamination of water bodies and the end result

will be rise in infections in human beings. The extent to which the water leads to contamination

of water reservoirs is determined by the techniques and methods used in withdrawal of the water

used in the fracking process (Northrop & Ross, 2016). Comparing the impact of shale gas to

natural gas, the negative impacts of natural gas is way higher and thus making fracking a better

option. When it comes to emission of gases to the atmosphere, it only happens when the process

is not done properly thus allowing chemicals and gases to penetrate the cracks on the rocks

(Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). Therefore, the Global Warming potential of hydraulic fracturing

process is low and can be controlled (Jiang, Hendrickson, and VanBriesen, 2014). Lastly, the

starts with vertical the horizontal, casing of the well, perforation, fracking, finalization and

production lastly either desertion or restoration of the site (Jenner and Lamadrid 2013). The

drilling process starts vertically, the direction which enables horizontal drilling which is line with

the process of forming the shale. Steel cases are inserted in the boreholes and cemented on the

rocks to hold the casing firmly (Hammond, O’Grady and Packham 2015 p. 2755). The casing on

the horizontal drilling is the perforated to pave way for the gas and crude oil. The next process is

fracking of the borehole using fracturing fluid which is driven through the horizontally drilled

hole to improve production. The fracking liquid is made up of water, chemicals and proppant.

99% of the fluid is water while the other percentages are a sorted chemicals and sand. The

completion phase involves recovery of the gas and abandoning of the site. Therefore, the study

looked into the impact of hydraulic fracturing activities as mentioned above and later

recommends the best practices to be undertaken in the production process by both the United

States and United Kingdom (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

Results

Poor waste water management practices lead to contamination of water bodies and the end result

will be rise in infections in human beings. The extent to which the water leads to contamination

of water reservoirs is determined by the techniques and methods used in withdrawal of the water

used in the fracking process (Northrop & Ross, 2016). Comparing the impact of shale gas to

natural gas, the negative impacts of natural gas is way higher and thus making fracking a better

option. When it comes to emission of gases to the atmosphere, it only happens when the process

is not done properly thus allowing chemicals and gases to penetrate the cracks on the rocks

(Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). Therefore, the Global Warming potential of hydraulic fracturing

process is low and can be controlled (Jiang, Hendrickson, and VanBriesen, 2014). Lastly, the

Energy Sustainability 10

most grievous impact the process leaves is the ability to reclaim the wells and also the manner in

which the fluid and material used in the process are disposed of.

Conclusion and Recommendation

After analysis of application of fracking activities in both United States and the U.K below are

recommendations to improve the state of affairs as far as protecting the environment is

concerned.

To start off, from previous research the number of licenses being issued to companies to conduct

fracking process has been increasing in the U.K. The high number is attributed to the fact that the

U.K government is in support of the process considering the fact that it has the potential to settle

the deficiency of gas being experienced and also create more jobs. However, it is important to

note that the world is shifting towards clean energy and thus it will be wise to give more

attention to clean sources of energy such sun, wind, geothermal and hydropower. This is because

they are sustainable, less costly to produce and environment friendly.

Additionally, it has been noted that the process utilizes a lot of water in the fracturing process

since 90% of the hydraulic liquid is water. The water is mixed up with sand and other chemicals

therefore making it toxic (Jiang, Hendrickson and VanBriesen, 2014). In essence, the water is

wasted and can’t be reused. To control this effect, research has to go towards the process of

recycling the water so that it can be put to other uses such as irrigation.

most grievous impact the process leaves is the ability to reclaim the wells and also the manner in

which the fluid and material used in the process are disposed of.

Conclusion and Recommendation

After analysis of application of fracking activities in both United States and the U.K below are

recommendations to improve the state of affairs as far as protecting the environment is

concerned.

To start off, from previous research the number of licenses being issued to companies to conduct

fracking process has been increasing in the U.K. The high number is attributed to the fact that the

U.K government is in support of the process considering the fact that it has the potential to settle

the deficiency of gas being experienced and also create more jobs. However, it is important to

note that the world is shifting towards clean energy and thus it will be wise to give more

attention to clean sources of energy such sun, wind, geothermal and hydropower. This is because

they are sustainable, less costly to produce and environment friendly.

Additionally, it has been noted that the process utilizes a lot of water in the fracturing process

since 90% of the hydraulic liquid is water. The water is mixed up with sand and other chemicals

therefore making it toxic (Jiang, Hendrickson and VanBriesen, 2014). In essence, the water is

wasted and can’t be reused. To control this effect, research has to go towards the process of

recycling the water so that it can be put to other uses such as irrigation.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Energy Sustainability 11

3.0 Political and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measures in the

housing and transport sectors

Sweden Case Study

Over the past years, Sweden has managed to build more than one million housing units with a

number of renovation projects on the road sector (Högberg, et al., 2009). Their main focus has

been on achieving energy efficient buildings due to the government energy ambitions of saving

the consumption of energy in the country.

Energy consumption in Sweden

In the year 2007, Sweden consumed energy about 624 TWh with a population of 9 million

(Högberg, et al., 2009). At the time, most energy was produced through hydroelectric power.

Including the renewable energy obtained from waste heat and electric heating furnace. In total,

these amounted to 25TWh in 2006.the building and transport sector consumed 35%, 143TWh, of

the total consumption. Out of which 60%, went into hot water and heating (Högberg, et al.,

2009).

To put everything into context, Swedish government came up with policies that will help

address the situation of energy consumption. These energy policies include;

Programmes directed to energy efficiency

In 1970s, Swedish government implement a public action programme that will oversee the issues

of energy efficiency in the building industry and transport sector (Högberg, et al., 2009). This

initiative included the introduction of support procurement procedures and energy efficient

technology in dwellings. This programme did not lead into political discourse in the country but

contributed to the famous visionary term Peoples’ New Green Home which was phrased by the

3.0 Political and financial incentives for the implementation of energy efficiency measures in the

housing and transport sectors

Sweden Case Study

Over the past years, Sweden has managed to build more than one million housing units with a

number of renovation projects on the road sector (Högberg, et al., 2009). Their main focus has

been on achieving energy efficient buildings due to the government energy ambitions of saving

the consumption of energy in the country.

Energy consumption in Sweden

In the year 2007, Sweden consumed energy about 624 TWh with a population of 9 million

(Högberg, et al., 2009). At the time, most energy was produced through hydroelectric power.

Including the renewable energy obtained from waste heat and electric heating furnace. In total,

these amounted to 25TWh in 2006.the building and transport sector consumed 35%, 143TWh, of

the total consumption. Out of which 60%, went into hot water and heating (Högberg, et al.,

2009).

To put everything into context, Swedish government came up with policies that will help

address the situation of energy consumption. These energy policies include;

Programmes directed to energy efficiency

In 1970s, Swedish government implement a public action programme that will oversee the issues

of energy efficiency in the building industry and transport sector (Högberg, et al., 2009). This

initiative included the introduction of support procurement procedures and energy efficient

technology in dwellings. This programme did not lead into political discourse in the country but

contributed to the famous visionary term Peoples’ New Green Home which was phrased by the

Energy Sustainability 12

former Prime Minister Persson. During the 1990s and 1980s, the move to reduce energy

consumption was targeted to reduce the high dependence on oil but today the policy has a huge

impact on climate change (Högberg, et al., 2009). Following the 1988 climate policy to reduce

the Cco2 gas levels in the atmosphere, however this objective expanded to greenhouse gases in

all sectors of the economy forcing Swedish to sign the Kyoto Protocol to help in the fight of

mitigating the changes in climate. The Swedish strategy was marrying with the United Nation

FCCC aim of achieving the reduction in GHG emission (Högberg, et al., 2009).

Currently, there are a few changes in the energy efficiency programmes that were

adopted in the millennium days. Ever since the adoption of the climate changes strategy in 1993,

Swedish policies have always been in line the EU policies (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). The EU has set out targets in managing climate change and energy by ensuring that a 20%

reduction in GHG and 20% renewable energy goals are achieved by 2020 (Högberg, et al.,

2009). In addition, each year, the government of Sweden provide incentives to organizations

mandated with this responsibility in order to increase their financial muscle. With these resources

put in place, these organisations find it easy to achieve their environmental objectives of

sustainable development (Högberg, et al., 2009). These objectives have been divided into local

level, regional level and national level. The objectives are directly related to energy efficiency

and they include clean air, reduced climate change, good built environment and natural

acidification only.

Case Studies of UK

A low-carbon economy forms the heart at which energy efficiency thrives. Cutting down on

energy use, and a reduction on waste helps reduce energy bills, making the energy system

former Prime Minister Persson. During the 1990s and 1980s, the move to reduce energy

consumption was targeted to reduce the high dependence on oil but today the policy has a huge

impact on climate change (Högberg, et al., 2009). Following the 1988 climate policy to reduce

the Cco2 gas levels in the atmosphere, however this objective expanded to greenhouse gases in

all sectors of the economy forcing Swedish to sign the Kyoto Protocol to help in the fight of

mitigating the changes in climate. The Swedish strategy was marrying with the United Nation

FCCC aim of achieving the reduction in GHG emission (Högberg, et al., 2009).

Currently, there are a few changes in the energy efficiency programmes that were

adopted in the millennium days. Ever since the adoption of the climate changes strategy in 1993,

Swedish policies have always been in line the EU policies (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). The EU has set out targets in managing climate change and energy by ensuring that a 20%

reduction in GHG and 20% renewable energy goals are achieved by 2020 (Högberg, et al.,

2009). In addition, each year, the government of Sweden provide incentives to organizations

mandated with this responsibility in order to increase their financial muscle. With these resources

put in place, these organisations find it easy to achieve their environmental objectives of

sustainable development (Högberg, et al., 2009). These objectives have been divided into local

level, regional level and national level. The objectives are directly related to energy efficiency

and they include clean air, reduced climate change, good built environment and natural

acidification only.

Case Studies of UK

A low-carbon economy forms the heart at which energy efficiency thrives. Cutting down on

energy use, and a reduction on waste helps reduce energy bills, making the energy system

Energy Sustainability 13

sustainable and reduces greenhouse emissions. The U.K housing and transport sectors have been

developing for hundreds of years, and the efficiency of their energy has changed from good to

bad to dreadful and back to being economical (Northrop & Ross, 2016). Strategies have been set

to give rise to good energy efficiency policy in decades to come. Energy efficiency can boost the

economy, and reduce the energy bills for transport and housing sectors offering maximum

potential for innovation and growth. The idea alone of achieving energy efficiency sets out the

opportunity in full.

In a case study on achieving growth in the U.K.'s Energy Efficiency retrofitting sector,

through energy efficiency measures, the political and financial incentives below stood out

(United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The U.K. adopted a green deal policy that assisted in

shifting the policy arena for retrofit (Northrop & Ross, 2016). The financial support from the

government was reduced since it was not efficient, and the private sector took over delivering

mechanisms, providing financial aid, and managing schemes that aim at reducing the carbon

levels domestically. The United Kingdom had in Place a change target, which implied that by

the 2050 age, the carbon level for residential property was reduced by 80 percent (United

Nations Climate Change, 2015). Therefore, the U.K. housing market needed an energy saving

measure via retrofitting. Retrofit policy measures had in the past targeted low goals in their fight

on energy efficiency to increase the performance of buildings such as increasing the loft

insulation (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The high ratio on energy efficiency scarcely

scratched the surface of the property enhancement sector. The variation gap between possible

energy is saving and achieving energy saving led to a gap difference in the performance of the

U.K. housing area.

sustainable and reduces greenhouse emissions. The U.K housing and transport sectors have been

developing for hundreds of years, and the efficiency of their energy has changed from good to

bad to dreadful and back to being economical (Northrop & Ross, 2016). Strategies have been set

to give rise to good energy efficiency policy in decades to come. Energy efficiency can boost the

economy, and reduce the energy bills for transport and housing sectors offering maximum

potential for innovation and growth. The idea alone of achieving energy efficiency sets out the

opportunity in full.

In a case study on achieving growth in the U.K.'s Energy Efficiency retrofitting sector,

through energy efficiency measures, the political and financial incentives below stood out

(United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The U.K. adopted a green deal policy that assisted in

shifting the policy arena for retrofit (Northrop & Ross, 2016). The financial support from the

government was reduced since it was not efficient, and the private sector took over delivering

mechanisms, providing financial aid, and managing schemes that aim at reducing the carbon

levels domestically. The United Kingdom had in Place a change target, which implied that by

the 2050 age, the carbon level for residential property was reduced by 80 percent (United

Nations Climate Change, 2015). Therefore, the U.K. housing market needed an energy saving

measure via retrofitting. Retrofit policy measures had in the past targeted low goals in their fight

on energy efficiency to increase the performance of buildings such as increasing the loft

insulation (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The high ratio on energy efficiency scarcely

scratched the surface of the property enhancement sector. The variation gap between possible

energy is saving and achieving energy saving led to a gap difference in the performance of the

U.K. housing area.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Energy Sustainability 14

The U.K. government started the Green Deal loan scheme at the beginning of 2013 (Su &

Thomson, 2016). It was a government initiative to help increase retrofit measures. Furthermore,

the U.K. government also launched the Energy Company Obligation new version motivating

energy suppliers to fund enhancements in energy efficiency to aid homeowners to decrease the

carbon emissions from their properties (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The Green Deal

scheme was designated to be a loan to the public, offering them a chance to commit to the

retrofit strategy at a broader scale. The government spearheaded the policy as its head or lead

strategy giving it a label of 'flagship.' The green deal, together with other measures, served as

energy security to protect the consumers from volatile energy prices (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). More federal incentives in the U.K. were put in Place to create a scenario where

the demand for energy is reduced through efficiency and furthermore reducing the need for a

broader variety to draw power (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). Thus, retrofit and energy

saving provide a foothold aiming at deregulation and allowing more measures to supply and save

energy. More distinctively the Green Loan scheme focuses on consumers providing a low carbon

economy and improving the housing and transport sectors (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). With

strategies placing the control of the policy on private areas, energy efficiency could grow at a

higher potential in the United Kingdom.

China Case Study

China has developed into a significant player when it comes to fighting CO2 omissions in the

combat against diverse climate change. It accounts for 40 to 50 percent of the global emissions,

which is over a quarter of the carbon emissions in the world (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Cancun conference

of 2010 proposed a peak when it comes to global emissions limiting the temperature rise to two

The U.K. government started the Green Deal loan scheme at the beginning of 2013 (Su &

Thomson, 2016). It was a government initiative to help increase retrofit measures. Furthermore,

the U.K. government also launched the Energy Company Obligation new version motivating

energy suppliers to fund enhancements in energy efficiency to aid homeowners to decrease the

carbon emissions from their properties (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The Green Deal

scheme was designated to be a loan to the public, offering them a chance to commit to the

retrofit strategy at a broader scale. The government spearheaded the policy as its head or lead

strategy giving it a label of 'flagship.' The green deal, together with other measures, served as

energy security to protect the consumers from volatile energy prices (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). More federal incentives in the U.K. were put in Place to create a scenario where

the demand for energy is reduced through efficiency and furthermore reducing the need for a

broader variety to draw power (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). Thus, retrofit and energy

saving provide a foothold aiming at deregulation and allowing more measures to supply and save

energy. More distinctively the Green Loan scheme focuses on consumers providing a low carbon

economy and improving the housing and transport sectors (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). With

strategies placing the control of the policy on private areas, energy efficiency could grow at a

higher potential in the United Kingdom.

China Case Study

China has developed into a significant player when it comes to fighting CO2 omissions in the

combat against diverse climate change. It accounts for 40 to 50 percent of the global emissions,

which is over a quarter of the carbon emissions in the world (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Cancun conference

of 2010 proposed a peak when it comes to global emissions limiting the temperature rise to two

Energy Sustainability 15

degree Celsius (Sioshansi, 2011). For this goal to be achieved, major global emitters, in this case,

China needed to be involved. It resulted in pressure for China to join an international climate

agreement that is uniform and binding when it comes to emissions gaps. China has great

potential within its energy-intensive sectors to lower its carbon emission (United Nations

Climate Change, 2015). This article focuses on the political and financial incentives for the

implementation of energy efficiency measures in the housing and transport sectors of China.

The building or rather the housing sector in China accounts for 15 percent of energy

consumption in the country by 2012. Statistics from IEA show that almost half of the housing

energy consumption is due to traditional biofuels from rural areas (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). The transport sector, on the other hand, accounts for 8 percent of the energy

consumed nationally and 9 percent for carbon emissions (Högberg, et al., 2009). The two

industries may seem to account for a small share of energy usage and carbon emission, but in

recent years, the acceleration has been over the roof. The transport energy consumption growth

rate has been recorded to increase rapidly, together with the housing sector. Urbanization and the

growth of income have been attributed as the main factors behind this growth rate (Nhamo &

Nhamo, 2016). China population rises by the millions, and in 2013, China added floor space

bigger than Australian housing inventory at 2 billion square meters (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). Furthermore, China became the world’s largest car market, leading to a

consumption-driven economy in terms of energy use and carbon emissions.

China has taken steps financially and politically to ensure energy efficiency in the

transport sector. It has raised the fuel efficiency standards to ensure the conservation of energy

and low levels of emissions. It has made enhancements in the fuel economy of light-duty

vehicles by reducing the emission intensity for the new cars in China (United Nations Climate

degree Celsius (Sioshansi, 2011). For this goal to be achieved, major global emitters, in this case,

China needed to be involved. It resulted in pressure for China to join an international climate

agreement that is uniform and binding when it comes to emissions gaps. China has great

potential within its energy-intensive sectors to lower its carbon emission (United Nations

Climate Change, 2015). This article focuses on the political and financial incentives for the

implementation of energy efficiency measures in the housing and transport sectors of China.

The building or rather the housing sector in China accounts for 15 percent of energy

consumption in the country by 2012. Statistics from IEA show that almost half of the housing

energy consumption is due to traditional biofuels from rural areas (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). The transport sector, on the other hand, accounts for 8 percent of the energy

consumed nationally and 9 percent for carbon emissions (Högberg, et al., 2009). The two

industries may seem to account for a small share of energy usage and carbon emission, but in

recent years, the acceleration has been over the roof. The transport energy consumption growth

rate has been recorded to increase rapidly, together with the housing sector. Urbanization and the

growth of income have been attributed as the main factors behind this growth rate (Nhamo &

Nhamo, 2016). China population rises by the millions, and in 2013, China added floor space

bigger than Australian housing inventory at 2 billion square meters (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015). Furthermore, China became the world’s largest car market, leading to a

consumption-driven economy in terms of energy use and carbon emissions.

China has taken steps financially and politically to ensure energy efficiency in the

transport sector. It has raised the fuel efficiency standards to ensure the conservation of energy

and low levels of emissions. It has made enhancements in the fuel economy of light-duty

vehicles by reducing the emission intensity for the new cars in China (United Nations Climate

Energy Sustainability 16

Change, 2015). In the building or housing section, China building codes have been improved as

compared to the past, making them increasingly stringent (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). However, the building codes are still not to that of European standards. In the energy

market transformation of China, the housing and transport sector are the main factors to

achieving energy efficiency (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The combined effort of the

carbon mitigation and energy conservation of these two platforms is a crucial element. Measures

such as the C& C regulations will help achieve this goal as it impacts the consumption sectors of

energy (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The government furthermore insists on a

renewable quota system to the usage of renewable energy in the market. The central policy

behind this strategy application is to conserve energy and mitigate carbon emission.

4.0 Impacts of developing renewable energy technologies

Introduction

Renewable energy obtains the name from the fact that their sources can be replenished.

Renewable energy is also referred to as clean energy because the process of generating the

energy is environmentally friendly compared to the non-renewable sources of energy which lead

to pollution of the environment (Twidell and Weir 2015). Notable sources of renewable energy

are the sun, wind, geothermal, hydropower and biomass. Solar power is currently the leading

source of renewable energy considering that it can easily be tapped by solar technology; it drives

winds and also facilitates growth of plants that can later be utilized in generation of biomass

(United Nations Climate Change, 2015). According to United Nations the 60% of greenhouse

gas come from the use of fossil fuels which currently is the leading source of energy in the world

at 80% (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). Therefore, to save the world steps have been made towards

Change, 2015). In the building or housing section, China building codes have been improved as

compared to the past, making them increasingly stringent (United Nations Climate Change,

2015). However, the building codes are still not to that of European standards. In the energy

market transformation of China, the housing and transport sector are the main factors to

achieving energy efficiency (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The combined effort of the

carbon mitigation and energy conservation of these two platforms is a crucial element. Measures

such as the C& C regulations will help achieve this goal as it impacts the consumption sectors of

energy (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). The government furthermore insists on a

renewable quota system to the usage of renewable energy in the market. The central policy

behind this strategy application is to conserve energy and mitigate carbon emission.

4.0 Impacts of developing renewable energy technologies

Introduction

Renewable energy obtains the name from the fact that their sources can be replenished.

Renewable energy is also referred to as clean energy because the process of generating the

energy is environmentally friendly compared to the non-renewable sources of energy which lead

to pollution of the environment (Twidell and Weir 2015). Notable sources of renewable energy

are the sun, wind, geothermal, hydropower and biomass. Solar power is currently the leading

source of renewable energy considering that it can easily be tapped by solar technology; it drives

winds and also facilitates growth of plants that can later be utilized in generation of biomass

(United Nations Climate Change, 2015). According to United Nations the 60% of greenhouse

gas come from the use of fossil fuels which currently is the leading source of energy in the world

at 80% (Nhamo & Nhamo, 2016). Therefore, to save the world steps have been made towards

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Energy Sustainability 17

adoption of clean energy in the world over. The process is not that easy because there are a

number of hindrances that range from technological challenges to high cost of adaptation

(Akella, Saini, and Sharma 2009 p.390). In the process of adaptation, a number of impacts are

felt across the board in different sectors. This paper looks into the impacts that renewable energy

has on the environment, financial and social aspects in the United States.

Environmental Impacts

Renewable energy utilization has varied impacts on the environment depending on the type of

technology used and the geographical location. The impacts are divided into four major

categories; Water usage, land usage, life-cycle greenhouse gas emission and Habitat loss (United

Nations Climate Change, 2015). Most of the renewable energy sources impacts on the

environment are better compared to the convention sources of energy such as fossil fuels. When

it comes to utilization of land wind turbines utilize an average of between 30 to 41 acres of land

per megawatt (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

According to a survey conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory one acre

of the land is permanently disturbed and 3.5 acres of the land is temporarily disturbed in the

process of construction (Nelson 2013). Therefore, the rest of the land can be used for other

purposes such as grazing and agriculture.National wind coordinating Committee (NWCC) in the

United States reported that wind turbines have led to death of birds and bats due to collision but

the effect is not that big to pose a threat to the population of the species (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015).

For the solar energy the impacts on the environment relate to land usage, water usage

and use of hazardous materials. In comparison to wind energy where the land could be used for

other purposes solar does not leave space for other activities beneath them. More so, solar

adoption of clean energy in the world over. The process is not that easy because there are a

number of hindrances that range from technological challenges to high cost of adaptation

(Akella, Saini, and Sharma 2009 p.390). In the process of adaptation, a number of impacts are

felt across the board in different sectors. This paper looks into the impacts that renewable energy

has on the environment, financial and social aspects in the United States.

Environmental Impacts

Renewable energy utilization has varied impacts on the environment depending on the type of

technology used and the geographical location. The impacts are divided into four major

categories; Water usage, land usage, life-cycle greenhouse gas emission and Habitat loss (United

Nations Climate Change, 2015). Most of the renewable energy sources impacts on the

environment are better compared to the convention sources of energy such as fossil fuels. When

it comes to utilization of land wind turbines utilize an average of between 30 to 41 acres of land

per megawatt (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

According to a survey conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory one acre

of the land is permanently disturbed and 3.5 acres of the land is temporarily disturbed in the

process of construction (Nelson 2013). Therefore, the rest of the land can be used for other

purposes such as grazing and agriculture.National wind coordinating Committee (NWCC) in the

United States reported that wind turbines have led to death of birds and bats due to collision but

the effect is not that big to pose a threat to the population of the species (United Nations Climate

Change, 2015).

For the solar energy the impacts on the environment relate to land usage, water usage

and use of hazardous materials. In comparison to wind energy where the land could be used for

other purposes solar does not leave space for other activities beneath them. More so, solar

Energy Sustainability 18

technology utilizes different chemicals that are harmful to the environment such as Hydrochloric

acid, sulphuric acid, Nitric acid and Hydrogen fluoride (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

Lastly, the impact of geothermal energy on the environment is essentially in relation to

open-loop systems which emit Hydrogen Sulphide (Northrop & Ross, 2016). When hydrogen

sulphide gets to the atmosphere it turns to sulphur dioxide which causes acid rain that affects

plants and the soil. However, it is important to note that use of renewable energy have minimal

impacts on the environment compared to the use of fossil fuels which cause environmental

pollution and deforestation (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

Financial Impacts

In the United States, 16% of energy sources are non-renewable and the uptake is quickly taking

shape (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). Use of renewable energy not only benefits the

environment but also impacts the economic sector of the sector. Increased use of renewable

energy has result to shifts in the trade sector in the sense that many production companies are

now focusing on producing products that utilize renewable energy (Northrop & Ross, 2016). In

the spirit of encouraging the use renewable energy, the United States government has reduced

import taxes for products meant to produce and develop technology in the renewable energy

sector. According to experts the dynamics are likely to improve both trade balance and the GDP

of the United States (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

According to a report by IRENA investments in the renewable sector could result to an increase

in the global GDP by 0.6% to 1.1% by the year 2030 (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

The changes will greatly improve the economic state of various countries in the world while at

the same time making the environment safe by using energy sources that cannot be depleted

technology utilizes different chemicals that are harmful to the environment such as Hydrochloric

acid, sulphuric acid, Nitric acid and Hydrogen fluoride (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

Lastly, the impact of geothermal energy on the environment is essentially in relation to

open-loop systems which emit Hydrogen Sulphide (Northrop & Ross, 2016). When hydrogen

sulphide gets to the atmosphere it turns to sulphur dioxide which causes acid rain that affects

plants and the soil. However, it is important to note that use of renewable energy have minimal

impacts on the environment compared to the use of fossil fuels which cause environmental

pollution and deforestation (Northrop & Ross, 2016).

Financial Impacts

In the United States, 16% of energy sources are non-renewable and the uptake is quickly taking

shape (United Nations Climate Change, 2015). Use of renewable energy not only benefits the

environment but also impacts the economic sector of the sector. Increased use of renewable

energy has result to shifts in the trade sector in the sense that many production companies are

now focusing on producing products that utilize renewable energy (Northrop & Ross, 2016). In

the spirit of encouraging the use renewable energy, the United States government has reduced

import taxes for products meant to produce and develop technology in the renewable energy

sector. According to experts the dynamics are likely to improve both trade balance and the GDP

of the United States (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

According to a report by IRENA investments in the renewable sector could result to an increase

in the global GDP by 0.6% to 1.1% by the year 2030 (United Nations Climate Change, 2015).

The changes will greatly improve the economic state of various countries in the world while at

the same time making the environment safe by using energy sources that cannot be depleted

Energy Sustainability 19

unlike using the conventional sources of energy that is harmful to the environment and also has

less return (Frondel, et al., 2010).

Social Impacts

Renewable energy has also impacted the social set-up of individuals in the United States.

To start with life of those employed in the renewable energy field has improved due to the

income generated from the firms. With good income, the employees are in a position to afford

good life for their families (Rogers, et al., 2012). Additionally, their children are able to attend

school and gain education. Secondly, renewable energy is relatively affordable compared to non-

renewable energy. The affordability makes it easy for the individuals earning less in the society

to access power through solar panels.

Conclusively, the use of renewable energy was essentially started to tame the negative

effects that arise from the use of non-renewable energy. Use of non-renewable energy has led to

emission of greenhouses gases that have caused climatic changes. Renewable energy is

generated from sources that can be replenished within one’s lifetime and thus saving the

environment from green gas emission and depletion of natural resources such as forests and

crude oil. The impacts of the use of renewable resource are quickly taking shape in the world

considering that the implementation and adoption levels are increasing with time. At the time use

of renewable energy stands at 16% with the solar energy being the most popular according to the

United Nation.

unlike using the conventional sources of energy that is harmful to the environment and also has

less return (Frondel, et al., 2010).

Social Impacts

Renewable energy has also impacted the social set-up of individuals in the United States.

To start with life of those employed in the renewable energy field has improved due to the

income generated from the firms. With good income, the employees are in a position to afford

good life for their families (Rogers, et al., 2012). Additionally, their children are able to attend

school and gain education. Secondly, renewable energy is relatively affordable compared to non-

renewable energy. The affordability makes it easy for the individuals earning less in the society

to access power through solar panels.

Conclusively, the use of renewable energy was essentially started to tame the negative

effects that arise from the use of non-renewable energy. Use of non-renewable energy has led to

emission of greenhouses gases that have caused climatic changes. Renewable energy is

generated from sources that can be replenished within one’s lifetime and thus saving the

environment from green gas emission and depletion of natural resources such as forests and

crude oil. The impacts of the use of renewable resource are quickly taking shape in the world

considering that the implementation and adoption levels are increasing with time. At the time use

of renewable energy stands at 16% with the solar energy being the most popular according to the

United Nation.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Energy Sustainability 20

References

Anderson, V. 2007.Energy efficiency policies. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Akella, A.K., Saini, R.P. and Sharma, M.P., 2009. Social, Economic and Environmental impacts

of renewable energy systems. Renewable Energy, 34(2), pp.390-396.

Bowen, A., &Rydge, J. 2011. Climate-Change Policy in the United Kingdom. 2nd ed. London:

Routledge

Broman, D., & Lawrence, L. R. 2009. Institutional and legal incentives and barriers for the

geothermal industry: Eastern Europe & China. Alexandria, VA, Bob Lawrence & Associates,

Inc. http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/LPS71236.

Burton Jr, G.A., Basu, N., Ellis, B.R., Kapo, K.E., Entrekin, S. and Nadelhoffer, K., 2014.

Hydraulic “Fracking”: Are surface water impacts an ecological concern? Environmental

Toxicology and Chemistry, 33(8), pp.1679-1689:https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2619.

Dale, A.T., Khanna, V., Vidic, R.D. and Bilec, M.M., 2013. Process based life-cycle assessment

of natural gas from the Marcellus Shale. Environmental science & technology, 47(10), pp.5459-

5466:https://doi.org/10.1021/es304414q.

Dimitrov, R.S., 2010. Inside Copenhagen: the state of climate governance. Global environmental

politics, 10(2), pp.18-24:https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2010.10.2.18

Frondel, M., Ritter, N., Schmidt, C.M. and Vance, C., 2010. Economic impacts from the

promotion of renewable energy technologies: The German experience. Energy Policy, 38(8),

pp.4048-4056:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.03.029

References

Anderson, V. 2007.Energy efficiency policies. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Akella, A.K., Saini, R.P. and Sharma, M.P., 2009. Social, Economic and Environmental impacts

of renewable energy systems. Renewable Energy, 34(2), pp.390-396.

Bowen, A., &Rydge, J. 2011. Climate-Change Policy in the United Kingdom. 2nd ed. London:

Routledge

Broman, D., & Lawrence, L. R. 2009. Institutional and legal incentives and barriers for the

geothermal industry: Eastern Europe & China. Alexandria, VA, Bob Lawrence & Associates,

Inc. http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/LPS71236.

Burton Jr, G.A., Basu, N., Ellis, B.R., Kapo, K.E., Entrekin, S. and Nadelhoffer, K., 2014.

Hydraulic “Fracking”: Are surface water impacts an ecological concern? Environmental

Toxicology and Chemistry, 33(8), pp.1679-1689:https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2619.

Dale, A.T., Khanna, V., Vidic, R.D. and Bilec, M.M., 2013. Process based life-cycle assessment

of natural gas from the Marcellus Shale. Environmental science & technology, 47(10), pp.5459-

5466:https://doi.org/10.1021/es304414q.

Dimitrov, R.S., 2010. Inside Copenhagen: the state of climate governance. Global environmental

politics, 10(2), pp.18-24:https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2010.10.2.18

Frondel, M., Ritter, N., Schmidt, C.M. and Vance, C., 2010. Economic impacts from the

promotion of renewable energy technologies: The German experience. Energy Policy, 38(8),

pp.4048-4056:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.03.029

Energy Sustainability 21

Jenner, S. and Lamadrid, A.J., 2013. Shale gas vs. coal: Policy implications from environmental

impact comparisons of shale gas, conventional gas, and coal on air, water, and land in the United

States. Energy Policy, 53, pp.442-453: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.11.010

Jiang, M., Hendrickson, C.T. and VanBriesen, J.M., 2014. Life cycle water consumption and

wastewater generation impacts of a Marcellus shale gas well. Environmental science &

technology, 48(3), pp.1911-1920:https://doi.org/10.1021/es4047654

Jiang, Z. 2010. Research on energy issues in China. Amsterdam, Elsevier/Academic Press.

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10399313

Högberg, L., Lind, H. and Grange, K., 2009. Incentives for improving energy efficiency when

renovating large-scale housing estates: a case study of the Swedish million homes

programme. Sustainability, 1(4), pp.1349-1365: https://doi.org/10.3390/su1041349

Hammond, G.P., O’Grady, Á. and Packham, D.E., 2015. Energy technology assessment of shale

gas ‘Fracking’–a UK perspective. Energy Procedia, 75,

pp.2764-2771:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.526.

Nhamo, G. and Nhamo, S., 2016. Paris (COP21) Agreement: Loss and damage, adaptation and

climate finance issues. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies-Multi-, Inter-and

Transdisciplinarity, 11(2), pp.118-138: https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2016.1212479

Northrop, E. and Ross, K., 2016. After COP21: what needs to happen for the Paris agreement to

take effect? Geominas, 44(70), pp.133-137.

Jenner, S. and Lamadrid, A.J., 2013. Shale gas vs. coal: Policy implications from environmental

impact comparisons of shale gas, conventional gas, and coal on air, water, and land in the United

States. Energy Policy, 53, pp.442-453: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.11.010

Jiang, M., Hendrickson, C.T. and VanBriesen, J.M., 2014. Life cycle water consumption and

wastewater generation impacts of a Marcellus shale gas well. Environmental science &

technology, 48(3), pp.1911-1920:https://doi.org/10.1021/es4047654

Jiang, Z. 2010. Research on energy issues in China. Amsterdam, Elsevier/Academic Press.

http://site.ebrary.com/id/10399313

Högberg, L., Lind, H. and Grange, K., 2009. Incentives for improving energy efficiency when

renovating large-scale housing estates: a case study of the Swedish million homes

programme. Sustainability, 1(4), pp.1349-1365: https://doi.org/10.3390/su1041349

Hammond, G.P., O’Grady, Á. and Packham, D.E., 2015. Energy technology assessment of shale

gas ‘Fracking’–a UK perspective. Energy Procedia, 75,

pp.2764-2771:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.526.

Nhamo, G. and Nhamo, S., 2016. Paris (COP21) Agreement: Loss and damage, adaptation and

climate finance issues. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies-Multi-, Inter-and

Transdisciplinarity, 11(2), pp.118-138: https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2016.1212479

Northrop, E. and Ross, K., 2016. After COP21: what needs to happen for the Paris agreement to

take effect? Geominas, 44(70), pp.133-137.

Energy Sustainability 22

Roberts, D., 2016. A global roadmap for climate change action: From COP17 in Durban to

COP21 in Paris. South African Journal of Science, 112(5-6), pp.1-3:

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/a0158

Rogers, J.C., Simmons, E.A., Convery, I. and Weatherall, A., 2012. Social impacts of

community renewable energy projects: findings from a woodfuel case study. Energy Policy, 42,

pp.239-247.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.11.081.

Sioshansi, F. P. 2011. Energy, sustainability, and the environment: technology, incentives,

behavior.Amsterdam, Butterworth-Heinemann.http://www.books24x7.com/marc.asp?

bookid=41852.

Stigka, E.K., Paravantis, J.A. and Mihalakakou, G.K., 2014. Social acceptance of renewable

energy sources: A review of contingent valuation applications. Renewable and sustainable

energy Reviews, 32, pp.100-106.Nelson, V., 2013. Wind energy: renewable energy and the

environment. CRC press.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.12.026

S.U., B., & Thomson, E. (2016).China's energy efficiency and conservation: sectoral analysis.

http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4499631.

Twidell, J. and Weir, T., 2015. Renewable energy resources.Abingdon, United Kingdom:

Routledge.

United Nations Climate Change, 2015.COP 21.[Online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/process-

and-meetings/conferences/past-conferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/

cop-21[Accessed 23 June 2019].

Roberts, D., 2016. A global roadmap for climate change action: From COP17 in Durban to

COP21 in Paris. South African Journal of Science, 112(5-6), pp.1-3:

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/a0158

Rogers, J.C., Simmons, E.A., Convery, I. and Weatherall, A., 2012. Social impacts of

community renewable energy projects: findings from a woodfuel case study. Energy Policy, 42,

pp.239-247.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.11.081.

Sioshansi, F. P. 2011. Energy, sustainability, and the environment: technology, incentives,

behavior.Amsterdam, Butterworth-Heinemann.http://www.books24x7.com/marc.asp?

bookid=41852.

Stigka, E.K., Paravantis, J.A. and Mihalakakou, G.K., 2014. Social acceptance of renewable

energy sources: A review of contingent valuation applications. Renewable and sustainable

energy Reviews, 32, pp.100-106.Nelson, V., 2013. Wind energy: renewable energy and the

environment. CRC press.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.12.026

S.U., B., & Thomson, E. (2016).China's energy efficiency and conservation: sectoral analysis.

http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4499631.

Twidell, J. and Weir, T., 2015. Renewable energy resources.Abingdon, United Kingdom:

Routledge.

United Nations Climate Change, 2015.COP 21.[Online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/process-

and-meetings/conferences/past-conferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/

cop-21[Accessed 23 June 2019].

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Energy Sustainability 23

.

.

.

.

1 out of 23

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.