Multilevel Model: TFL, Skill Development, Knowledge & Creativity

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/26

|21

|15492

|436

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review examines the impact of dual-focused transformational leadership (TFL) on employee creativity, addressing the challenge of fostering both individual and team creativity. It introduces a multilevel model connecting dual-focused TFL to creativity, incorporating skill development at the individual level and knowledge sharing at the team level as mediating mechanisms. The review differentiates between individual-focused TFL, which emphasizes individual skill development, and team-focused TFL, which promotes team knowledge sharing. Findings from high-technology firms indicate that individual-focused TFL positively influences individual creativity through skill development, while team-focused TFL impacts team creativity through knowledge sharing. Furthermore, knowledge sharing moderates the relationship between individual-focused TFL, skill development, and individual creativity, highlighting the synergistic effects of individual and team dynamics. The study contributes to the understanding of how leaders can facilitate multilevel creativity by examining the differential impacts of dual-focused TFL and identifying level-specific mechanisms that connect TFL to creativity.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308293733

Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team

knowledge sharing: Influences of dual‐focused transformational leadership

Article in Journal of Organizational Behavior · September 2016

DOI: 10.1002/job.2134

CITATIONS

51

READS

5,749

4 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Examining Multilevel Factors' Influences on Organizational Creativity and Innovation and Its Dynamic Mechanism in Enterprise TransformationView project

Gerardo R UngsonView project

Yuntao Dong

University of Connecticut

5 PUBLICATIONS73CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Zhi-Xue Zhang

Peking University

66PUBLICATIONS1,438CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Chenwei Li

San Francisco State University

17PUBLICATIONS188CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team

knowledge sharing: Influences of dual‐focused transformational leadership

Article in Journal of Organizational Behavior · September 2016

DOI: 10.1002/job.2134

CITATIONS

51

READS

5,749

4 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Examining Multilevel Factors' Influences on Organizational Creativity and Innovation and Its Dynamic Mechanism in Enterprise TransformationView project

Gerardo R UngsonView project

Yuntao Dong

University of Connecticut

5 PUBLICATIONS73CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Zhi-Xue Zhang

Peking University

66PUBLICATIONS1,438CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Chenwei Li

San Francisco State University

17PUBLICATIONS188CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Enhancing employee creativity via individual ski

development and team knowledge sharing:

Influences of dual-focused transformational

leadership

YUNTAO DONG1*, KATHRYN M. BARTOL 2, ZHI-XUE ZHANG 3 AND CHENWEI LI 4†

1University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, U.S.A.

2University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, Maryland, U.S.A.

3Peking University, Beijing, China

4San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, U.S.A.

Summary Addressing the challenges faced by team leaders in fostering both individual and team creativity

developed and tested a multilevelmodelconnecting dual-focused transformationalleadership (TFL)and

creativity and incorporating intervening mechanisms at the two levels. Using multilevel, multiso

data from individual members, team leaders, and direct supervisors in high-technology firms, we

individual-focused TFL had a positive indirecteffecton individualcreativity via individualskill develop-

ment, whereas team-focused TFL impacted team creativity partially through its influence on tea

sharing. We also found that knowledge sharing constituted a cross-level contextual factor that m

relationship among individual-focused TFL,skill development,and individualcreativity.We discuss the

theoreticaland practicalimplications of this research and offer suggestions for future research.Copyright

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: transformationalleadership;employeecreativity;skill development;knowledgesharing;

multilevel

Employee creativity, defined as the generation of novel and useful ideas (Amabile, 1988; Zhou & Sha

critical to organizational survival and effectiveness. There has been increasing research interest in ex

leaders might do to encourage the production of creative outcomes (Anderson, Potočnik, & Zhou, 201

of teams,in particular,this can presenta specialchallenge.On the one hand,ideas are ultimately offered up by

individuals,and hence,it is useful for leaders to develop individuals'knowledge and skills needed for creativity.

On the other hand,related research suggests that team creativity is more than the sum of its individual

requires the exchange of knowledge among team members. Emphasizing promoting individuals'development (Dvir,

Eden,Avolio, & Shamir,2002)while encouraging collective contribution (Eisenbeiss,Van Knippenberg,&

Boerner, 2008), transformational leadership (TFL) is particularly well suited to set in motion appropria

at both the individual and team levels to handle this dual challenge.

Yet, in a recent meta-analysis, Rosing, Frese, and Bausch (2011) have pointed to inconsistencies in

on TFL–creativity relationship and suggested that the high degree of variation found in the relationsh

to the lack of clarification of the levels of analyses. In fact, recent theoretical advancements regardin

effective transformational leaders have different emphases when managing individuals and teams (L

Boyle, 2016; Li, Shang, Liu, & Xi, 2014; Wang & Howell, 2010; Wu, Tsui, & Kinicki, 2010), with some b

*Correspondence to: Yuntao Dong, University of Connecticut, 2100 Hillside Road, Unit 1041, Storrs, CT 06269, U.S.A. E-mail: y

dong@business.uconn.edu

†This research was initiated when Professor Chenwei Li was at Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne,

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Received 28 May 2015

Revised 30 July 2016, Accepted 10 August 2016

Journal of Organizational Behavior, J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/job.2134

Research Article

development and team knowledge sharing:

Influences of dual-focused transformational

leadership

YUNTAO DONG1*, KATHRYN M. BARTOL 2, ZHI-XUE ZHANG 3 AND CHENWEI LI 4†

1University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, U.S.A.

2University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, Maryland, U.S.A.

3Peking University, Beijing, China

4San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, U.S.A.

Summary Addressing the challenges faced by team leaders in fostering both individual and team creativity

developed and tested a multilevelmodelconnecting dual-focused transformationalleadership (TFL)and

creativity and incorporating intervening mechanisms at the two levels. Using multilevel, multiso

data from individual members, team leaders, and direct supervisors in high-technology firms, we

individual-focused TFL had a positive indirecteffecton individualcreativity via individualskill develop-

ment, whereas team-focused TFL impacted team creativity partially through its influence on tea

sharing. We also found that knowledge sharing constituted a cross-level contextual factor that m

relationship among individual-focused TFL,skill development,and individualcreativity.We discuss the

theoreticaland practicalimplications of this research and offer suggestions for future research.Copyright

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: transformationalleadership;employeecreativity;skill development;knowledgesharing;

multilevel

Employee creativity, defined as the generation of novel and useful ideas (Amabile, 1988; Zhou & Sha

critical to organizational survival and effectiveness. There has been increasing research interest in ex

leaders might do to encourage the production of creative outcomes (Anderson, Potočnik, & Zhou, 201

of teams,in particular,this can presenta specialchallenge.On the one hand,ideas are ultimately offered up by

individuals,and hence,it is useful for leaders to develop individuals'knowledge and skills needed for creativity.

On the other hand,related research suggests that team creativity is more than the sum of its individual

requires the exchange of knowledge among team members. Emphasizing promoting individuals'development (Dvir,

Eden,Avolio, & Shamir,2002)while encouraging collective contribution (Eisenbeiss,Van Knippenberg,&

Boerner, 2008), transformational leadership (TFL) is particularly well suited to set in motion appropria

at both the individual and team levels to handle this dual challenge.

Yet, in a recent meta-analysis, Rosing, Frese, and Bausch (2011) have pointed to inconsistencies in

on TFL–creativity relationship and suggested that the high degree of variation found in the relationsh

to the lack of clarification of the levels of analyses. In fact, recent theoretical advancements regardin

effective transformational leaders have different emphases when managing individuals and teams (L

Boyle, 2016; Li, Shang, Liu, & Xi, 2014; Wang & Howell, 2010; Wu, Tsui, & Kinicki, 2010), with some b

*Correspondence to: Yuntao Dong, University of Connecticut, 2100 Hillside Road, Unit 1041, Storrs, CT 06269, U.S.A. E-mail: y

dong@business.uconn.edu

†This research was initiated when Professor Chenwei Li was at Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne,

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Received 28 May 2015

Revised 30 July 2016, Accepted 10 August 2016

Journal of Organizational Behavior, J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/job.2134

Research Article

most meaningfully targeted at individuals (individual-focused TFL) and other behaviors more properly dir

the team (team-focused TFL). Thus, the dual-focused conceptualization of TFL may have the potential to

creativity research. Li et al. (2016) have made a first attempt to adopt dual-focused TFL in this realm by

predictinnovation in teams.However,there is widespread recognition thatinnovation encompasses both idea

generation (creativity)and implementation,which are increasingly viewed as involving substantially different

dynamics and mechanisms (Anderson etal.,2014;Rosing etal.,2011).Hence,in this study,we focus squarely

on multilevel associations between dual-focused TFL and creativity.

Although TFL is recognized as an influential enabler for creativity, there have been diverse and mixed

what pathways a leader may take to affect individual and team creativity. One major line of research has

the role of the leader as a facilitator of follower creativity (Mainemelis, Kark, & Epitropaki, 2015). Here, w

thatresearch stream by exploring the possibility thatdual-focused TFL increases the prospectthatthe followers

themselves can step up to the creativity requirements of the job,while also stimulating the team toward greater

creativity production.Specifically,individual-focused TFL tends to “stimulate individuals to develop their own

skills” (Li et al., 2016, p. 4), while team-focused TFL motivates team members to offer information out of

to benefitthe collective (Zhang,Tsui, & Wang,2011)and enables “transmission and sharing ofknowledge”

(García-Morales, Lloréns-Montes, & Verdú-Jover, 2008, p. 300). Enhanced individual skills and knowledge

may, in turn, help the individual and the group, respectively, enact their creative potential. Hence, indivi

development and team knowledge sharing may be important mechanisms linking dual-focused TFL and

However, research has yet to examine these mechanisms simultaneously under a dual-focused framew

tions remain regarding how dual-focused TFL may uniquely and synergistically impact individual and tea

ity. This is important because, as Gong, Kim, Lee, and Zhu (2013, p. 844) have noted, “individuals must

back into the study ofteam creativity” as team creativity depends on the foundationalindividualcapability to

generate ideas. At the same time, as Gilson, Lim, Luciano, and Choi (2013) have claimed, individual deve

and creativity are constantly shaped by team knowledge exchange. These arguments highlight the pote

tages of integrating dual-focused TFL and creativity and the associated mechanisms in a multilevel fram

Accordingly,we propose and testa theoreticalmodelthatexamines how dual-focused TFL may influence

individualand team creativity via separate channels.Integrating the dual-focused TFL perspective and creativity

literature,we consider skilldevelopmentatthe individualleveland knowledge sharing atthe team levelas the

mediating mechanisms. Further, in view of calls for understanding how the multilevel mediators of TFL m

with each other (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin,2013),we investigate the cross-levelinfluence of team knowledge

sharing on the individual-level relationships.

We aim to make three significant contributions. First, we examine the differential impacts of individual

team-focused TFL on creativity, demonstrating the utility of dual-focused TFL in the creativity realm. Sec

tifying individual skill development and team knowledge sharing as influence channels of individual-focu

team-focused TFL, our study addresses the need for research on level-specific mechanisms that connect

ity (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013) and contributes to the broader literature on creative leadership wit

differentmeans through which a leader may facilitate multilevelcreativity (Mainemelis etal.,2015).Third,by

simultaneously examining the multilevel mediators, we are able to provide insights regarding the cross-l

on individual creativity while bringing a conceptual and empirical integration to “findings related to the d

effects of team dynamics and individual contributions” on employee creativity (Li et al., 2016, p. 2).

Theory and Hypotheses

In this section, we trace the development of our model by first explicating a dual-focused conceptualizat

We next examine the mediating relationships explaining how individual-focused TFL boosts employee cr

enhancing individualskill developmentand how team-focused TFL fosters team creativity via promoting team

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

the team (team-focused TFL). Thus, the dual-focused conceptualization of TFL may have the potential to

creativity research. Li et al. (2016) have made a first attempt to adopt dual-focused TFL in this realm by

predictinnovation in teams.However,there is widespread recognition thatinnovation encompasses both idea

generation (creativity)and implementation,which are increasingly viewed as involving substantially different

dynamics and mechanisms (Anderson etal.,2014;Rosing etal.,2011).Hence,in this study,we focus squarely

on multilevel associations between dual-focused TFL and creativity.

Although TFL is recognized as an influential enabler for creativity, there have been diverse and mixed

what pathways a leader may take to affect individual and team creativity. One major line of research has

the role of the leader as a facilitator of follower creativity (Mainemelis, Kark, & Epitropaki, 2015). Here, w

thatresearch stream by exploring the possibility thatdual-focused TFL increases the prospectthatthe followers

themselves can step up to the creativity requirements of the job,while also stimulating the team toward greater

creativity production.Specifically,individual-focused TFL tends to “stimulate individuals to develop their own

skills” (Li et al., 2016, p. 4), while team-focused TFL motivates team members to offer information out of

to benefitthe collective (Zhang,Tsui, & Wang,2011)and enables “transmission and sharing ofknowledge”

(García-Morales, Lloréns-Montes, & Verdú-Jover, 2008, p. 300). Enhanced individual skills and knowledge

may, in turn, help the individual and the group, respectively, enact their creative potential. Hence, indivi

development and team knowledge sharing may be important mechanisms linking dual-focused TFL and

However, research has yet to examine these mechanisms simultaneously under a dual-focused framew

tions remain regarding how dual-focused TFL may uniquely and synergistically impact individual and tea

ity. This is important because, as Gong, Kim, Lee, and Zhu (2013, p. 844) have noted, “individuals must

back into the study ofteam creativity” as team creativity depends on the foundationalindividualcapability to

generate ideas. At the same time, as Gilson, Lim, Luciano, and Choi (2013) have claimed, individual deve

and creativity are constantly shaped by team knowledge exchange. These arguments highlight the pote

tages of integrating dual-focused TFL and creativity and the associated mechanisms in a multilevel fram

Accordingly,we propose and testa theoreticalmodelthatexamines how dual-focused TFL may influence

individualand team creativity via separate channels.Integrating the dual-focused TFL perspective and creativity

literature,we consider skilldevelopmentatthe individualleveland knowledge sharing atthe team levelas the

mediating mechanisms. Further, in view of calls for understanding how the multilevel mediators of TFL m

with each other (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin,2013),we investigate the cross-levelinfluence of team knowledge

sharing on the individual-level relationships.

We aim to make three significant contributions. First, we examine the differential impacts of individual

team-focused TFL on creativity, demonstrating the utility of dual-focused TFL in the creativity realm. Sec

tifying individual skill development and team knowledge sharing as influence channels of individual-focu

team-focused TFL, our study addresses the need for research on level-specific mechanisms that connect

ity (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013) and contributes to the broader literature on creative leadership wit

differentmeans through which a leader may facilitate multilevelcreativity (Mainemelis etal.,2015).Third,by

simultaneously examining the multilevel mediators, we are able to provide insights regarding the cross-l

on individual creativity while bringing a conceptual and empirical integration to “findings related to the d

effects of team dynamics and individual contributions” on employee creativity (Li et al., 2016, p. 2).

Theory and Hypotheses

In this section, we trace the development of our model by first explicating a dual-focused conceptualizat

We next examine the mediating relationships explaining how individual-focused TFL boosts employee cr

enhancing individualskill developmentand how team-focused TFL fosters team creativity via promoting team

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

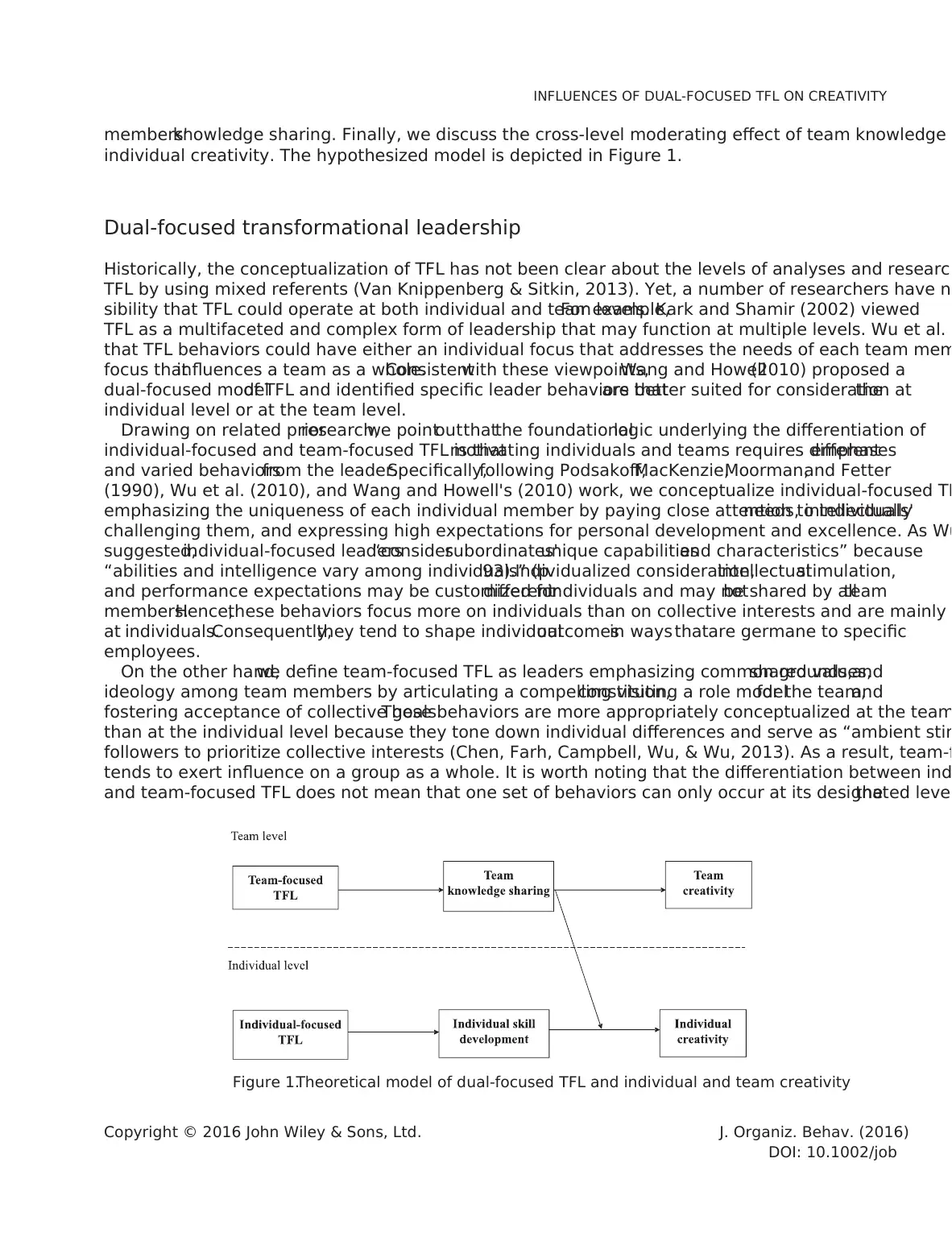

members'knowledge sharing. Finally, we discuss the cross-level moderating effect of team knowledge

individual creativity. The hypothesized model is depicted in Figure 1.

Dual-focused transformational leadership

Historically, the conceptualization of TFL has not been clear about the levels of analyses and research

TFL by using mixed referents (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013). Yet, a number of researchers have no

sibility that TFL could operate at both individual and team levels.For example,Kark and Shamir (2002) viewed

TFL as a multifaceted and complex form of leadership that may function at multiple levels. Wu et al. (

that TFL behaviors could have either an individual focus that addresses the needs of each team mem

focus thatinfluences a team as a whole.Consistentwith these viewpoints,Wang and Howell(2010) proposed a

dual-focused modelof TFL and identified specific leader behaviors thatare better suited for consideration atthe

individual level or at the team level.

Drawing on related priorresearch,we pointoutthatthe foundationallogic underlying the differentiation of

individual-focused and team-focused TFL is thatmotivating individuals and teams requires differentemphases

and varied behaviorsfrom the leader.Specifically,following Podsakoff,MacKenzie,Moorman,and Fetter

(1990), Wu et al. (2010), and Wang and Howell's (2010) work, we conceptualize individual-focused TF

emphasizing the uniqueness of each individual member by paying close attention to individuals'needs, intellectually

challenging them, and expressing high expectations for personal development and excellence. As Wu

suggested,individual-focused leaders“considersubordinates'unique capabilitiesand characteristics” because

“abilities and intelligence vary among individuals” (p.93).Individualized consideration,intellectualstimulation,

and performance expectations may be customized fordifferentindividuals and may notbe shared by allteam

members.Hence,these behaviors focus more on individuals than on collective interests and are mainly

at individuals.Consequently,they tend to shape individualoutcomesin ways thatare germane to specific

employees.

On the other hand,we define team-focused TFL as leaders emphasizing common grounds,shared values,and

ideology among team members by articulating a compelling vision,constituting a role modelfor the team,and

fostering acceptance of collective goals.These behaviors are more appropriately conceptualized at the team

than at the individual level because they tone down individual differences and serve as “ambient stim

followers to prioritize collective interests (Chen, Farh, Campbell, Wu, & Wu, 2013). As a result, team-f

tends to exert influence on a group as a whole. It is worth noting that the differentiation between ind

and team-focused TFL does not mean that one set of behaviors can only occur at its designated levelthe

Figure 1.Theoretical model of dual-focused TFL and individual and team creativity

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

individual creativity. The hypothesized model is depicted in Figure 1.

Dual-focused transformational leadership

Historically, the conceptualization of TFL has not been clear about the levels of analyses and research

TFL by using mixed referents (Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013). Yet, a number of researchers have no

sibility that TFL could operate at both individual and team levels.For example,Kark and Shamir (2002) viewed

TFL as a multifaceted and complex form of leadership that may function at multiple levels. Wu et al. (

that TFL behaviors could have either an individual focus that addresses the needs of each team mem

focus thatinfluences a team as a whole.Consistentwith these viewpoints,Wang and Howell(2010) proposed a

dual-focused modelof TFL and identified specific leader behaviors thatare better suited for consideration atthe

individual level or at the team level.

Drawing on related priorresearch,we pointoutthatthe foundationallogic underlying the differentiation of

individual-focused and team-focused TFL is thatmotivating individuals and teams requires differentemphases

and varied behaviorsfrom the leader.Specifically,following Podsakoff,MacKenzie,Moorman,and Fetter

(1990), Wu et al. (2010), and Wang and Howell's (2010) work, we conceptualize individual-focused TF

emphasizing the uniqueness of each individual member by paying close attention to individuals'needs, intellectually

challenging them, and expressing high expectations for personal development and excellence. As Wu

suggested,individual-focused leaders“considersubordinates'unique capabilitiesand characteristics” because

“abilities and intelligence vary among individuals” (p.93).Individualized consideration,intellectualstimulation,

and performance expectations may be customized fordifferentindividuals and may notbe shared by allteam

members.Hence,these behaviors focus more on individuals than on collective interests and are mainly

at individuals.Consequently,they tend to shape individualoutcomesin ways thatare germane to specific

employees.

On the other hand,we define team-focused TFL as leaders emphasizing common grounds,shared values,and

ideology among team members by articulating a compelling vision,constituting a role modelfor the team,and

fostering acceptance of collective goals.These behaviors are more appropriately conceptualized at the team

than at the individual level because they tone down individual differences and serve as “ambient stim

followers to prioritize collective interests (Chen, Farh, Campbell, Wu, & Wu, 2013). As a result, team-f

tends to exert influence on a group as a whole. It is worth noting that the differentiation between ind

and team-focused TFL does not mean that one set of behaviors can only occur at its designated levelthe

Figure 1.Theoretical model of dual-focused TFL and individual and team creativity

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

conceptualization points out that some behaviors are conceptually more functional and more likely to op

certain level than at the other level.

Impacts of individual-focused TFL on creativity via individual skill development

Creativity theories suggest that effective leadership can serve as an enabler that helps individuals acqui

knowledge and skills, which are a key component for creating new ideas or products (Amabile, 1988; An

2014). This view is supported by studies from related fields. For example, in considering creativity as a s

of proactivity, Parker and Wu (2014, p. 393) proposed that “leaders can influence the proactivity of their

through fostering the development of knowledge, skills, and abilities.” Further, the developmental notion

individual-focused TFL, given its emphasis on mentoring, coaching, and challenging individual followers b

their needs and abilities.As such,follower developmentconstitutes a principalinfluence process through which

individual-focused TFL may foster individual creativity. We define individual skill development as one's a

ment in developmental activities in order to obtain work-related knowledge and skills to facilitate long-te

acquisition and enhancement related to one's work (Noe, 1996; Pulakos, Arad, Donovan, & Plamondon, 2

Relevant evidence suggests that individual-focused TFL can influence follower development by commu

high expectations for excellence and superior performance to stimulate followers'intrinsic needs for growth (Bass &

Avolio, 1994; Wang & Howell, 2010). Consequently, followers will more actively participate in developme

ities. For example, Dvir et al. (2002) found that transformational leaders motivate followers to exert extr

satisfy their own self-actualization needs. In addition, through intellectual stimulation, transformational l

encourage followers to challenge traditions and to think about problems from different perspectives,all of which

require followers to master new skills and to shift viewpoints via continuous development (Shin & Zhou,2003).

Finally,transformationalleaders emphasize individualized consideration,provide support,and show respectfor

individuals'needs for development.Along these lines,Maurer and colleagues (Maurer & Tarulli,1994;Maurer,

Weiss,& Barbeite,2003) found thatsupervisor supportfor developmentwas positively related to subordinates'

intention to participate in development activities as well as subsequent actual participation (e.g., attend

reading journals, or initiating new projects). Taken together, we expect individual-focused TFL to motivat

ual followers to actively engage in skill development.

Hypothesis 1: Individual-focused TFL is positively related to individual skill development.

Creativity scholars(e.g.,Amabile,1988)have posited thatthe extentto which individualsdevelop their

knowledge and skills in a given area of interest is one of “the major influences on output of creative idea

and is “necessary for … creativity to be produced” (p. 137). These skills comprise fundamental resources

uals to put existing information and newly generated ideas together in novel combinations (Anderson et

other words, factual knowledge, technical skills, and work experience in the domain of interest allow an

understand complexities and generate a set of response possibilities from which new responses can be s

larger the set of possibilities, the more numerous the alternatives available for producing something new

individuals who engage in skill development are more likely to have an increased range and depth of kno

more developed skills, providing them the basis for critical thinking that is needed to creatively solve pro

improve current processes (Zhang & Bartol, 2010). Woodman, Sawyer, and Griffin (1993, p. 301) quoted

insight: “Invention is little more than a new combination of those images, which have been previously ga

deposited in the memory.Nothing can be made ofnothing.He who has laid up no materialcan produce no

combination” (quoted in Offner, 1990).

Supporting these arguments, Chen, Shih, and Yeh (2011) showed that individual possession of differen

was critical for public sector employees to connect different disciplines of knowledge and engage in the

thinking thatis crucialfor creativity.Similarly,Yang,Lee,and Cheng (2016) provided some relevantevidence

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

certain level than at the other level.

Impacts of individual-focused TFL on creativity via individual skill development

Creativity theories suggest that effective leadership can serve as an enabler that helps individuals acqui

knowledge and skills, which are a key component for creating new ideas or products (Amabile, 1988; An

2014). This view is supported by studies from related fields. For example, in considering creativity as a s

of proactivity, Parker and Wu (2014, p. 393) proposed that “leaders can influence the proactivity of their

through fostering the development of knowledge, skills, and abilities.” Further, the developmental notion

individual-focused TFL, given its emphasis on mentoring, coaching, and challenging individual followers b

their needs and abilities.As such,follower developmentconstitutes a principalinfluence process through which

individual-focused TFL may foster individual creativity. We define individual skill development as one's a

ment in developmental activities in order to obtain work-related knowledge and skills to facilitate long-te

acquisition and enhancement related to one's work (Noe, 1996; Pulakos, Arad, Donovan, & Plamondon, 2

Relevant evidence suggests that individual-focused TFL can influence follower development by commu

high expectations for excellence and superior performance to stimulate followers'intrinsic needs for growth (Bass &

Avolio, 1994; Wang & Howell, 2010). Consequently, followers will more actively participate in developme

ities. For example, Dvir et al. (2002) found that transformational leaders motivate followers to exert extr

satisfy their own self-actualization needs. In addition, through intellectual stimulation, transformational l

encourage followers to challenge traditions and to think about problems from different perspectives,all of which

require followers to master new skills and to shift viewpoints via continuous development (Shin & Zhou,2003).

Finally,transformationalleaders emphasize individualized consideration,provide support,and show respectfor

individuals'needs for development.Along these lines,Maurer and colleagues (Maurer & Tarulli,1994;Maurer,

Weiss,& Barbeite,2003) found thatsupervisor supportfor developmentwas positively related to subordinates'

intention to participate in development activities as well as subsequent actual participation (e.g., attend

reading journals, or initiating new projects). Taken together, we expect individual-focused TFL to motivat

ual followers to actively engage in skill development.

Hypothesis 1: Individual-focused TFL is positively related to individual skill development.

Creativity scholars(e.g.,Amabile,1988)have posited thatthe extentto which individualsdevelop their

knowledge and skills in a given area of interest is one of “the major influences on output of creative idea

and is “necessary for … creativity to be produced” (p. 137). These skills comprise fundamental resources

uals to put existing information and newly generated ideas together in novel combinations (Anderson et

other words, factual knowledge, technical skills, and work experience in the domain of interest allow an

understand complexities and generate a set of response possibilities from which new responses can be s

larger the set of possibilities, the more numerous the alternatives available for producing something new

individuals who engage in skill development are more likely to have an increased range and depth of kno

more developed skills, providing them the basis for critical thinking that is needed to creatively solve pro

improve current processes (Zhang & Bartol, 2010). Woodman, Sawyer, and Griffin (1993, p. 301) quoted

insight: “Invention is little more than a new combination of those images, which have been previously ga

deposited in the memory.Nothing can be made ofnothing.He who has laid up no materialcan produce no

combination” (quoted in Offner, 1990).

Supporting these arguments, Chen, Shih, and Yeh (2011) showed that individual possession of differen

was critical for public sector employees to connect different disciplines of knowledge and engage in the

thinking thatis crucialfor creativity.Similarly,Yang,Lee,and Cheng (2016) provided some relevantevidence

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

by showing that frontline bank tellers who possessed more knowledge and skills were likely to engag

thinking and identify new opportunities in the service realm. Finally, Choi (2004) found that creative a

refers to skills or competencies relevant to creative performance, such as the ability to look at proble

perspectives,was significantly related to individualcreativity.Taken together,ourtheorizing and the evidence

suggest that individual-focused TFL may enhance follower creativity because it is associated with kno

skill acquisition, a major predictor of individual creative performance.

Hypothesis2: Individualskill developmentmediatesthe relationship between individual-focused TFL and

individual creativity.

Impacts of team-focused TFL on team creativity as mediated by knowledge sharing

Enhancing team creativity requires leaders not only to develop creative individuals but also to promo

communication and information exchange (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006). As Taggar (2002) has pointed

should reach a higher level of creativity when they contain both creative members and effective proc

members can collectively approach and utilize knowledge available within the team. Due to its emph

vision and collective goals,team-focused TFL may be particularly effective in involving team membersin

knowledge sharing activities, which, in turn, help the team enact its creative potential. We define tea

sharing as the extent to which team members share task-relevant ideas, information, and suggestion

(Srivastava, Bartol, & Locke, 2006).

By communicating and promoting collective vision and values, team-focused transformational lead

membersunderstand thatindividualinputsof usefulknowledge and information are valuable to team goal

accomplishment.As a result,team members are likely to feel more inclined to engage in such efforts as off

constructive suggestions and sharing unique information so as to contribute to the achievementof mutualgoals

(Eisenbeiss etal.,2008).Moreover,by providing an appropriate role modeland facilitating team acceptance of

collective objectives, team-focused TFL may shape a deeper understanding and appreciation of contr

all members (Li et al., 2014; Shin, Kim, Lee, & Bian, 2012). As team members feel that their inputs ar

are willing to take the opportunity to share their knowledge (Detert& Burris,2007).In sampling research and

development(R&D) teams in a multinationalpharmaceuticalcompany,Kearney and Gebert(2009) found that

TFL was effective in fostering the exchange and elaboration of task-relevant information when the te

of specialized members.Consistently,Li etal. (2014) found thatgroup-focused leadership increased individual

members'knowledge-providing and knowledge-collecting behaviors. Based on these arguments, we hy

positive impact of team-focused TFL on team knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 3: Team-focused TFL is positively related to team knowledge sharing.

The positive impactof team knowledge sharing on team creativity is consistentwith the suggestion thatthe

communication of individual knowledge in a team is a viable resource for the team to generate new i

et al.,2013; Zhang et al.,2011).In line with previous research (e.g.,Gino,Argote,Miron-Spektor,& Todorova,

2010;Hülsheger,Anderson,& Salgado,2009),we refer to team creativity as the combination of newness an

usefulness of ideas that are developed by the team. Team creativity is not simply the aggregation of

by individual members; rather, it involves team members collectively processing information, conside

views, and eventually producing creative outcomes.

Specifically,because exchange of diverse information helps in boosting the repository of available ex

skills, and knowledge in the team, it enables the team to utilize and integrate the resources to accom

tasks, such as those of developing new products or procedures (Gardner, Gino, & Staats, 2012). For e

and Choi(2012)argued thata greaterteam knowledge stock offers more opportunities to recombine existi

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

thinking and identify new opportunities in the service realm. Finally, Choi (2004) found that creative a

refers to skills or competencies relevant to creative performance, such as the ability to look at proble

perspectives,was significantly related to individualcreativity.Taken together,ourtheorizing and the evidence

suggest that individual-focused TFL may enhance follower creativity because it is associated with kno

skill acquisition, a major predictor of individual creative performance.

Hypothesis2: Individualskill developmentmediatesthe relationship between individual-focused TFL and

individual creativity.

Impacts of team-focused TFL on team creativity as mediated by knowledge sharing

Enhancing team creativity requires leaders not only to develop creative individuals but also to promo

communication and information exchange (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006). As Taggar (2002) has pointed

should reach a higher level of creativity when they contain both creative members and effective proc

members can collectively approach and utilize knowledge available within the team. Due to its emph

vision and collective goals,team-focused TFL may be particularly effective in involving team membersin

knowledge sharing activities, which, in turn, help the team enact its creative potential. We define tea

sharing as the extent to which team members share task-relevant ideas, information, and suggestion

(Srivastava, Bartol, & Locke, 2006).

By communicating and promoting collective vision and values, team-focused transformational lead

membersunderstand thatindividualinputsof usefulknowledge and information are valuable to team goal

accomplishment.As a result,team members are likely to feel more inclined to engage in such efforts as off

constructive suggestions and sharing unique information so as to contribute to the achievementof mutualgoals

(Eisenbeiss etal.,2008).Moreover,by providing an appropriate role modeland facilitating team acceptance of

collective objectives, team-focused TFL may shape a deeper understanding and appreciation of contr

all members (Li et al., 2014; Shin, Kim, Lee, & Bian, 2012). As team members feel that their inputs ar

are willing to take the opportunity to share their knowledge (Detert& Burris,2007).In sampling research and

development(R&D) teams in a multinationalpharmaceuticalcompany,Kearney and Gebert(2009) found that

TFL was effective in fostering the exchange and elaboration of task-relevant information when the te

of specialized members.Consistently,Li etal. (2014) found thatgroup-focused leadership increased individual

members'knowledge-providing and knowledge-collecting behaviors. Based on these arguments, we hy

positive impact of team-focused TFL on team knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 3: Team-focused TFL is positively related to team knowledge sharing.

The positive impactof team knowledge sharing on team creativity is consistentwith the suggestion thatthe

communication of individual knowledge in a team is a viable resource for the team to generate new i

et al.,2013; Zhang et al.,2011).In line with previous research (e.g.,Gino,Argote,Miron-Spektor,& Todorova,

2010;Hülsheger,Anderson,& Salgado,2009),we refer to team creativity as the combination of newness an

usefulness of ideas that are developed by the team. Team creativity is not simply the aggregation of

by individual members; rather, it involves team members collectively processing information, conside

views, and eventually producing creative outcomes.

Specifically,because exchange of diverse information helps in boosting the repository of available ex

skills, and knowledge in the team, it enables the team to utilize and integrate the resources to accom

tasks, such as those of developing new products or procedures (Gardner, Gino, & Staats, 2012). For e

and Choi(2012)argued thata greaterteam knowledge stock offers more opportunities to recombine existi

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

information and ideas by making rich cognitive resources and diverse approaches available. These schol

evidence that if teams can identify relevant knowledge and activate the value of knowledge distributed a

bers, they will achieve higher levels of creativity. In contrast, if individual experience and resources are n

the cognitive resources within a team remain underutilized (Gino et al., 2010; Griffith & Sawyer, 2010). I

knowledge sharing also leads to a more comprehensive consideration of information, which is a necessa

enabling collective creativity (Gong et al., 2013).

The positive association between knowledge sharing and creativity has recently received some empiric

in a variety of teams,including research and developmentteams,manufacturing groups,and managementteams

(Gong etal.,2013;Sung & Choi,2012;Zhang etal.,2011).Based on a meta-analysis,Hülsheger etal. (2009)

concluded that internalcommunication of knowledge and other teamwork-related subjects among team mem

emerged as one of the most powerful agents of new idea generation and implementation in the team.Combining

with arguments underlying Hypothesis 3,we suggestthatteam-focused TFL willbe positively related to team

knowledge sharing, which will then lead to higher levels of team creativity.

Hypothesis 4: Team knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between team-focused TFL and team

Cross-level moderating impact by team knowledge sharing

According to Amabile (1988),open communication systems for knowledge exchange among differentorganiza-

tionalmembers may influence the extentto which domain skills fosterindividualcreativity.Therefore,team

knowledge sharing,as an indicator of open communication in work groups,may have a cross-levelimpacton

the relationship between individual skill development and creativity.Specifically,when sharing knowledge,team

members are exposed to various points of view and multiple alternatives,which may mutually inspire individual

team members (Hirst,Van Knippenberg,& Zhou,2009;Homan,Van Knippenberg,Van Kleef,& De Dreu,

2007).Individualmembers'knowledge poolmay be enlarged and theirdivergentthinking may be activated

and enhanced (Sheremata,2000).In other words,the sharing provides team members with more valuable infor-

mation and the discussion of shared knowledge can inspire them to develop new insights and strategies

ing problems.Team members can build on others'contributions to supplement their existing resources and aid in

producing their own creative alternatives. Hence, whereas one's skills and knowledge comprise the basic

blocks for individualcreativity,team knowledge sharing helps individualmembers to better utilize their existing

knowledge in generating novelideas (Zhou,Shin,Brass,Choi,& Zhang,2009).In line with this logic,Gong

etal. (2013) showed thatthrough exchanges with other team members and being exposed to diverse ideas,an

individual team member may enhance his or her divergent thinking that is conducive to creativity.They also ar-

gued that knowledge sharing may be particularly important for R&D teams because those team member

rely on high-quality information exchange to tackle complex problems and develop new products and se

a regular base.

Hypothesis 5a: Team knowledge sharing moderates the relationship between individualskilldevelopmentand

individual creativity, such that the relationship is stronger when there are higher rather than lower lev

knowledge sharing.

Considering also the individual-level relationships among TFL, skill development, and creativity hypoth

Hypothesis 2, we further propose that team knowledge sharing moderates the effect of individual-focuse

creativity via developing individual skills.

Hypothesis 5b: Team knowledge sharing moderates the mediated relationship between individual-focu

and individual creativity via skill development, such that the relationship is stronger when there are hi

than lower levels of team knowledge sharing.

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

evidence that if teams can identify relevant knowledge and activate the value of knowledge distributed a

bers, they will achieve higher levels of creativity. In contrast, if individual experience and resources are n

the cognitive resources within a team remain underutilized (Gino et al., 2010; Griffith & Sawyer, 2010). I

knowledge sharing also leads to a more comprehensive consideration of information, which is a necessa

enabling collective creativity (Gong et al., 2013).

The positive association between knowledge sharing and creativity has recently received some empiric

in a variety of teams,including research and developmentteams,manufacturing groups,and managementteams

(Gong etal.,2013;Sung & Choi,2012;Zhang etal.,2011).Based on a meta-analysis,Hülsheger etal. (2009)

concluded that internalcommunication of knowledge and other teamwork-related subjects among team mem

emerged as one of the most powerful agents of new idea generation and implementation in the team.Combining

with arguments underlying Hypothesis 3,we suggestthatteam-focused TFL willbe positively related to team

knowledge sharing, which will then lead to higher levels of team creativity.

Hypothesis 4: Team knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between team-focused TFL and team

Cross-level moderating impact by team knowledge sharing

According to Amabile (1988),open communication systems for knowledge exchange among differentorganiza-

tionalmembers may influence the extentto which domain skills fosterindividualcreativity.Therefore,team

knowledge sharing,as an indicator of open communication in work groups,may have a cross-levelimpacton

the relationship between individual skill development and creativity.Specifically,when sharing knowledge,team

members are exposed to various points of view and multiple alternatives,which may mutually inspire individual

team members (Hirst,Van Knippenberg,& Zhou,2009;Homan,Van Knippenberg,Van Kleef,& De Dreu,

2007).Individualmembers'knowledge poolmay be enlarged and theirdivergentthinking may be activated

and enhanced (Sheremata,2000).In other words,the sharing provides team members with more valuable infor-

mation and the discussion of shared knowledge can inspire them to develop new insights and strategies

ing problems.Team members can build on others'contributions to supplement their existing resources and aid in

producing their own creative alternatives. Hence, whereas one's skills and knowledge comprise the basic

blocks for individualcreativity,team knowledge sharing helps individualmembers to better utilize their existing

knowledge in generating novelideas (Zhou,Shin,Brass,Choi,& Zhang,2009).In line with this logic,Gong

etal. (2013) showed thatthrough exchanges with other team members and being exposed to diverse ideas,an

individual team member may enhance his or her divergent thinking that is conducive to creativity.They also ar-

gued that knowledge sharing may be particularly important for R&D teams because those team member

rely on high-quality information exchange to tackle complex problems and develop new products and se

a regular base.

Hypothesis 5a: Team knowledge sharing moderates the relationship between individualskilldevelopmentand

individual creativity, such that the relationship is stronger when there are higher rather than lower lev

knowledge sharing.

Considering also the individual-level relationships among TFL, skill development, and creativity hypoth

Hypothesis 2, we further propose that team knowledge sharing moderates the effect of individual-focuse

creativity via developing individual skills.

Hypothesis 5b: Team knowledge sharing moderates the mediated relationship between individual-focu

and individual creativity via skill development, such that the relationship is stronger when there are hi

than lower levels of team knowledge sharing.

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Method

Research site and participants

We collected data from eightcompanies in a major high-technology developmentzone located in northwestern

China.We sampled their R&D teams which consisted of professional-level employees working interdep

such as software engineers and new product developers.One of the authors visited these companies to distribut

and collect questionnaires during their working hours. Data were collected from team members, team

supervisors to whom the team directly reports. In the member survey, team members offered demog

tion and assessed the team leader's behaviors,team knowledge sharing,and task interdependence.In the leader

survey,team leaders evaluated each member's skilldevelopmentbehaviors and creativity.In a separate survey,

supervisors rated each team's creativity. All surveys were distributed to the participants in separate e

completed, the survey was put back in the envelope and then collected by the researcher. As all part

questions on theirown survey and theirresponses were keptconfidential,we reduced participants'concern in

answering the questions,especially those requiring team members to assess their team leader.The finalsample

consisted of 171 individuals in 43 teams from eight companies.Among the team members,the average age was

29 years, the average team tenure was 24 months, and 60 percent were male.

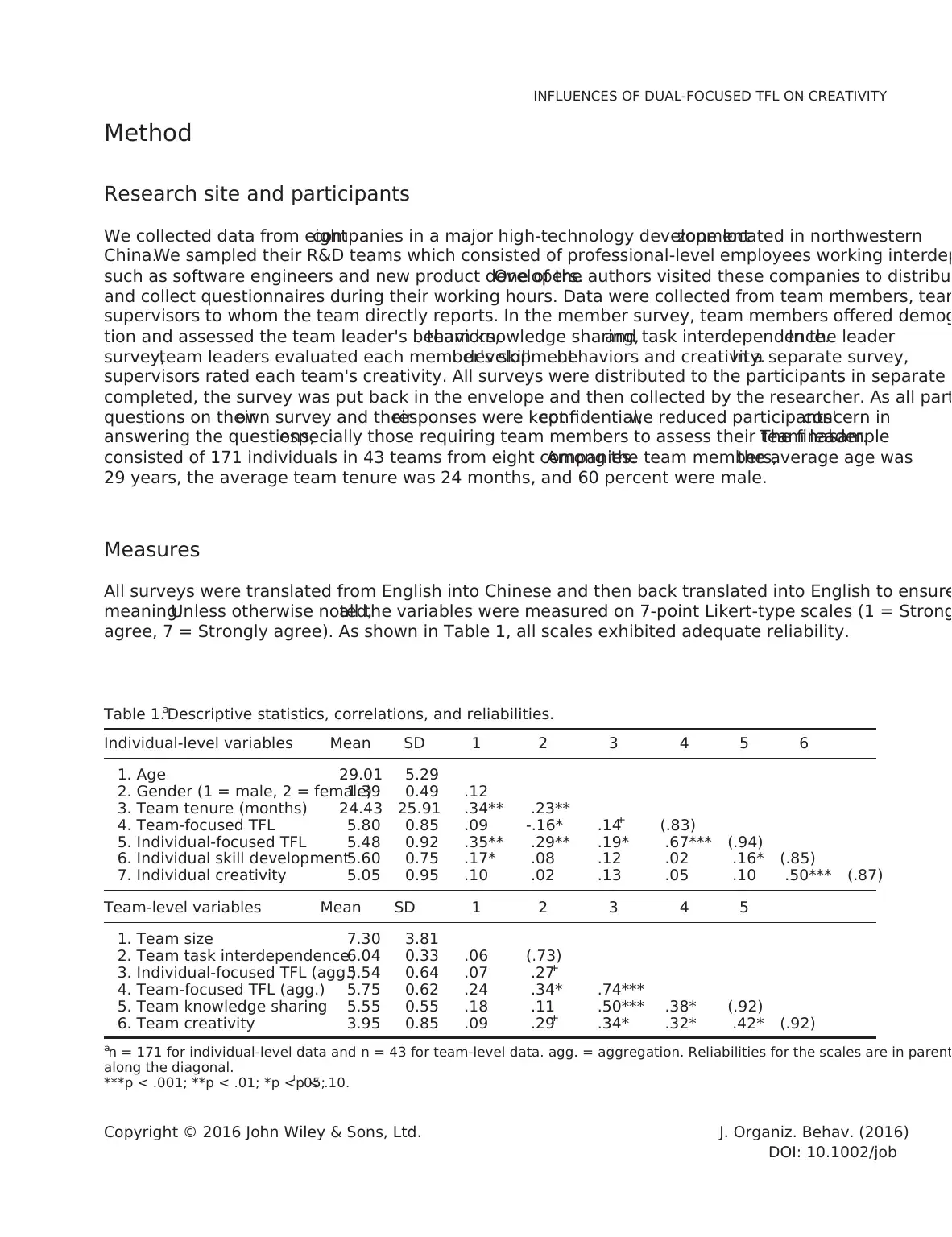

Measures

All surveys were translated from English into Chinese and then back translated into English to ensure

meaning.Unless otherwise noted,all the variables were measured on 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = Strong

agree, 7 = Strongly agree). As shown in Table 1, all scales exhibited adequate reliability.

Table 1.aDescriptive statistics, correlations, and reliabilities.

Individual-level variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Age 29.01 5.29

2. Gender (1 = male, 2 = female)1.39 0.49 .12

3. Team tenure (months) 24.43 25.91 .34** .23**

4. Team-focused TFL 5.80 0.85 .09 -.16* .14+ (.83)

5. Individual-focused TFL 5.48 0.92 .35** .29** .19* .67*** (.94)

6. Individual skill development5.60 0.75 .17* .08 .12 .02 .16* (.85)

7. Individual creativity 5.05 0.95 .10 .02 .13 .05 .10 .50*** (.87)

Team-level variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5

1. Team size 7.30 3.81

2. Team task interdependence6.04 0.33 .06 (.73)

3. Individual-focused TFL (agg.)5.54 0.64 .07 .27+

4. Team-focused TFL (agg.) 5.75 0.62 .24 .34* .74***

5. Team knowledge sharing 5.55 0.55 .18 .11 .50*** .38* (.92)

6. Team creativity 3.95 0.85 .09 .29+ .34* .32* .42* (.92)

an = 171 for individual-level data and n = 43 for team-level data. agg. = aggregation. Reliabilities for the scales are in parent

along the diagonal.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05;+

p < .10.

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Research site and participants

We collected data from eightcompanies in a major high-technology developmentzone located in northwestern

China.We sampled their R&D teams which consisted of professional-level employees working interdep

such as software engineers and new product developers.One of the authors visited these companies to distribut

and collect questionnaires during their working hours. Data were collected from team members, team

supervisors to whom the team directly reports. In the member survey, team members offered demog

tion and assessed the team leader's behaviors,team knowledge sharing,and task interdependence.In the leader

survey,team leaders evaluated each member's skilldevelopmentbehaviors and creativity.In a separate survey,

supervisors rated each team's creativity. All surveys were distributed to the participants in separate e

completed, the survey was put back in the envelope and then collected by the researcher. As all part

questions on theirown survey and theirresponses were keptconfidential,we reduced participants'concern in

answering the questions,especially those requiring team members to assess their team leader.The finalsample

consisted of 171 individuals in 43 teams from eight companies.Among the team members,the average age was

29 years, the average team tenure was 24 months, and 60 percent were male.

Measures

All surveys were translated from English into Chinese and then back translated into English to ensure

meaning.Unless otherwise noted,all the variables were measured on 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = Strong

agree, 7 = Strongly agree). As shown in Table 1, all scales exhibited adequate reliability.

Table 1.aDescriptive statistics, correlations, and reliabilities.

Individual-level variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Age 29.01 5.29

2. Gender (1 = male, 2 = female)1.39 0.49 .12

3. Team tenure (months) 24.43 25.91 .34** .23**

4. Team-focused TFL 5.80 0.85 .09 -.16* .14+ (.83)

5. Individual-focused TFL 5.48 0.92 .35** .29** .19* .67*** (.94)

6. Individual skill development5.60 0.75 .17* .08 .12 .02 .16* (.85)

7. Individual creativity 5.05 0.95 .10 .02 .13 .05 .10 .50*** (.87)

Team-level variables Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5

1. Team size 7.30 3.81

2. Team task interdependence6.04 0.33 .06 (.73)

3. Individual-focused TFL (agg.)5.54 0.64 .07 .27+

4. Team-focused TFL (agg.) 5.75 0.62 .24 .34* .74***

5. Team knowledge sharing 5.55 0.55 .18 .11 .50*** .38* (.92)

6. Team creativity 3.95 0.85 .09 .29+ .34* .32* .42* (.92)

an = 171 for individual-level data and n = 43 for team-level data. agg. = aggregation. Reliabilities for the scales are in parent

along the diagonal.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05;+

p < .10.

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Dual-focused transformational leadership

Transformational leadership was assessed using the 14-item version of Podsakoff et al.'s (1990) measure

also been used by Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, and Lowe (2009). Subsequent to the initiation of our data

we became aware of an emerging dual-focused TFL scale (Wang & Howell, 2010), which was based on th

TFL measures (e.g.,Avolio & Bass,2004;Podsakoff etal.,1990).Accordingly,we conducted a supplementary

study thatconfirmed the measurementequivalence between the scale we used and Wang and Howell's scale

(Appendix A).Podsakoff etal. (1990) identified six classes of TFL behaviors.Consistentwith the dual-focused

TFL conceptualization,offering individualized support,providing intellectualstimulations,and expressing high

performance expectations constituted individual-focused TFL and articulating a team vision,providing an appro-

priate model,and fostering acceptance of team goals constituted team-focused TFL.The referents in our items

reflected the appropriate targetof influence (i.e.,individualmembers or the team).Sample items for individual-

focused TFL included [The leader] “shows respectfor my personalfeelings” and “has stimulated me to rethink

the way Ido things.” Sample items forteam-focused TFL included [The leader]“articulates a vision forthe

team” and “facilitates the acceptance of group goals.”

In keeping with previous research (e.g.,Li etal.,2016;Wang & Howell,2010),we averaged allitems atthe

individual level to create an overall score for the individual-focused TFL scale.To obtain the team-focused TFL,

we averaged allteam-focused items for each individualand then aggregated members'team-focused TFL scores

for each team.We computed rwg(j)to assess interrater agreement. The average rwg(j)across the 43 teams was .97,

indicating a high level of within-team agreement. We also obtained the intraclass correlation (ICC1) and

of group mean (ICC2). The ICC1 and ICC2 values were .23 (p < .001) and .54, respectively. Taking all the

into account, we concluded that aggregation of team member ratings of team-focused TFL was warrante

Individual skill development

Individual skill development was reported by team leaders using a six-item measure based on the work b

et al. (2000) and London and Mone (1987). It captured an individual team member's skill development b

the work context that were observed by the team leader. A sample item was “This team member works

his/her knowledge and skills up-to-date so he/she can work effectively.” We averaged all items to obtain

scale.

Individual creativity

We measured individualcreativity using the well-established four-item scale reported by Farmer,Tierney,and

Kung-McIntyre (2003). A sample item was “This team member seeks new ideas and ways to solve proble

Team knowledge sharing

Team knowledge sharing was assessed by the six team knowledge sharing items developed by Bartol, Li

and Wu (2009).A sample item was “There is a lot of exchange of information,knowledge,and sharing of skills

among members in our team.” The average rwg(j)across the 43 teams was .98. The ICC1 value was .17 (p < .01),

and the ICC2 value was .44. We aggregated the individual-level knowledge sharing scores for each team

the respective team-level construct.

Team creativity

Supervisors were asked to rate each team's creativity by using a four-item scale developed by Shin and

on a 7-pointscale ranging from 1 (Needs much improvement)to 7 (Excellent).Supervisors were provided the

definition of team creativity. A sample item was “How creative do you consider this team to be?”

Covariates

At the individual level, we controlled for individuals'age, gender, and team tenure, which have been found to impa

individual learning and creativity (e.g., Gong et al., 2013). At the team level, we controlled for team size

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Transformational leadership was assessed using the 14-item version of Podsakoff et al.'s (1990) measure

also been used by Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, and Lowe (2009). Subsequent to the initiation of our data

we became aware of an emerging dual-focused TFL scale (Wang & Howell, 2010), which was based on th

TFL measures (e.g.,Avolio & Bass,2004;Podsakoff etal.,1990).Accordingly,we conducted a supplementary

study thatconfirmed the measurementequivalence between the scale we used and Wang and Howell's scale

(Appendix A).Podsakoff etal. (1990) identified six classes of TFL behaviors.Consistentwith the dual-focused

TFL conceptualization,offering individualized support,providing intellectualstimulations,and expressing high

performance expectations constituted individual-focused TFL and articulating a team vision,providing an appro-

priate model,and fostering acceptance of team goals constituted team-focused TFL.The referents in our items

reflected the appropriate targetof influence (i.e.,individualmembers or the team).Sample items for individual-

focused TFL included [The leader] “shows respectfor my personalfeelings” and “has stimulated me to rethink

the way Ido things.” Sample items forteam-focused TFL included [The leader]“articulates a vision forthe

team” and “facilitates the acceptance of group goals.”

In keeping with previous research (e.g.,Li etal.,2016;Wang & Howell,2010),we averaged allitems atthe

individual level to create an overall score for the individual-focused TFL scale.To obtain the team-focused TFL,

we averaged allteam-focused items for each individualand then aggregated members'team-focused TFL scores

for each team.We computed rwg(j)to assess interrater agreement. The average rwg(j)across the 43 teams was .97,

indicating a high level of within-team agreement. We also obtained the intraclass correlation (ICC1) and

of group mean (ICC2). The ICC1 and ICC2 values were .23 (p < .001) and .54, respectively. Taking all the

into account, we concluded that aggregation of team member ratings of team-focused TFL was warrante

Individual skill development

Individual skill development was reported by team leaders using a six-item measure based on the work b

et al. (2000) and London and Mone (1987). It captured an individual team member's skill development b

the work context that were observed by the team leader. A sample item was “This team member works

his/her knowledge and skills up-to-date so he/she can work effectively.” We averaged all items to obtain

scale.

Individual creativity

We measured individualcreativity using the well-established four-item scale reported by Farmer,Tierney,and

Kung-McIntyre (2003). A sample item was “This team member seeks new ideas and ways to solve proble

Team knowledge sharing

Team knowledge sharing was assessed by the six team knowledge sharing items developed by Bartol, Li

and Wu (2009).A sample item was “There is a lot of exchange of information,knowledge,and sharing of skills

among members in our team.” The average rwg(j)across the 43 teams was .98. The ICC1 value was .17 (p < .01),

and the ICC2 value was .44. We aggregated the individual-level knowledge sharing scores for each team

the respective team-level construct.

Team creativity

Supervisors were asked to rate each team's creativity by using a four-item scale developed by Shin and

on a 7-pointscale ranging from 1 (Needs much improvement)to 7 (Excellent).Supervisors were provided the

definition of team creativity. A sample item was “How creative do you consider this team to be?”

Covariates

At the individual level, we controlled for individuals'age, gender, and team tenure, which have been found to impa

individual learning and creativity (e.g., Gong et al., 2013). At the team level, we controlled for team size

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

team leaders to reportthe totalnumber of team members.Team size has been suggested to influence employee

creativity and various team processes (e.g., Eisenbeiss et al., 2008; Hirst et al., 2009). We also contro

task interdependence because itmay have a distinctimpacton team knowledge sharing and employee creativity

(Gong et al.,2013; Li et al.,2016).Task interdependence was assessed using the four-item scale from Kirk

Rosen, Tesluk, and Gibson (2004) and aggregated to the team level.

Confirmatory factor analysis

We conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to examine the distinctiveness of the k

the study. The overall model fit was assessed by the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis ind

standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (R

hypothesized five-factormodel(i.e.,individual-focused TFL,team-focused TFL,skill development,individual

creativity,and knowledgesharing)indicated agood fit to the data(χ2(383)= 690.53,CFI = .92,TLI = .90,

SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .06). All indicators loaded significantly (p < .05) onto the intended latent varia

parison with a four-factor model, in which individual-focused TFL and team-focused TFL were loaded

(χ2(387)= 776.87, CFI = .89, TLI = .88, SRMR = .08, RMSEA = .06), showed that the hypothesized mode

significantly better than the alternative model(Δχ2(4)= 86.34,p < .001).We also compared the five-factor model

with another four-factor model,in which team leader-rated individual skill development and individual crea

were loaded on one factor. The model did not fit the data well (χ2(387)= 782.56, CFI = .89, TLI = .88, SRMR = .08,

RMSEA = .07) and was significant worse than the hypothesized model (Δχ2(4)= 92.03, p < .001). Finally, we found

that compared with a three-factor model, in which all variables reported by team members (individua

team-focused TFL,and knowledge sharing)were loaded on one factor(χ2(390)= 1211.78,CFI = .77,TLI = .75,

SRMR = .11,RMSEA = .09),the hypothesized models fitthe data significantly better (Δχ2(7)= 521.25,p < .001).

These results supported the discriminant validity of the measures used in the study.

Analytical approach

We used hierarchicallinear modeling (HLM) to testthe multilevelmodel.We included an intercept-only model

atthe organization levelto controlfor organizationaleffects.Hence,for the individual-leveland cross-levelre-

lationships,we applied HLM3 with team members specified atLevel1, teams atLevel2, and organizations at

Level 3.For the team-level relationships,we conducted HLM2 with teams at Level 1 and organizations at Lev

2. Following the recommendations by Zhang,Zyphur,and Preacher (2009),we group-mean centered individual

skill development and added its group mean back to the Level 2 intercept-only model as covariates f

levelinteractions.When testing the effectof individual-focused TFL,we included team-focused TFL to control

for its influence,whereaswhen testing the effectof team-focused TFL,we controlled forthe influence of

individual-focused TFL.This strategy allows us to demonstrate the distincteffects ofone aspectof TFL at a

given levelaftercontrolling forthe effectsof the otherTFL aspectat a differentlevel.To examine the

significance of the mediations and the moderated mediated relationships,we employed a Monte Carlo simulation

procedure using the open-source software R (Preacher & Selig,2012).This method more accurately reflects the

asymmetric nature of the sampling distribution of a mediating effect.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables at both individual an

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

creativity and various team processes (e.g., Eisenbeiss et al., 2008; Hirst et al., 2009). We also contro

task interdependence because itmay have a distinctimpacton team knowledge sharing and employee creativity

(Gong et al.,2013; Li et al.,2016).Task interdependence was assessed using the four-item scale from Kirk

Rosen, Tesluk, and Gibson (2004) and aggregated to the team level.

Confirmatory factor analysis

We conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to examine the distinctiveness of the k

the study. The overall model fit was assessed by the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis ind

standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (R

hypothesized five-factormodel(i.e.,individual-focused TFL,team-focused TFL,skill development,individual

creativity,and knowledgesharing)indicated agood fit to the data(χ2(383)= 690.53,CFI = .92,TLI = .90,

SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .06). All indicators loaded significantly (p < .05) onto the intended latent varia

parison with a four-factor model, in which individual-focused TFL and team-focused TFL were loaded

(χ2(387)= 776.87, CFI = .89, TLI = .88, SRMR = .08, RMSEA = .06), showed that the hypothesized mode

significantly better than the alternative model(Δχ2(4)= 86.34,p < .001).We also compared the five-factor model

with another four-factor model,in which team leader-rated individual skill development and individual crea

were loaded on one factor. The model did not fit the data well (χ2(387)= 782.56, CFI = .89, TLI = .88, SRMR = .08,

RMSEA = .07) and was significant worse than the hypothesized model (Δχ2(4)= 92.03, p < .001). Finally, we found

that compared with a three-factor model, in which all variables reported by team members (individua

team-focused TFL,and knowledge sharing)were loaded on one factor(χ2(390)= 1211.78,CFI = .77,TLI = .75,

SRMR = .11,RMSEA = .09),the hypothesized models fitthe data significantly better (Δχ2(7)= 521.25,p < .001).

These results supported the discriminant validity of the measures used in the study.

Analytical approach

We used hierarchicallinear modeling (HLM) to testthe multilevelmodel.We included an intercept-only model

atthe organization levelto controlfor organizationaleffects.Hence,for the individual-leveland cross-levelre-

lationships,we applied HLM3 with team members specified atLevel1, teams atLevel2, and organizations at

Level 3.For the team-level relationships,we conducted HLM2 with teams at Level 1 and organizations at Lev

2. Following the recommendations by Zhang,Zyphur,and Preacher (2009),we group-mean centered individual

skill development and added its group mean back to the Level 2 intercept-only model as covariates f

levelinteractions.When testing the effectof individual-focused TFL,we included team-focused TFL to control

for its influence,whereaswhen testing the effectof team-focused TFL,we controlled forthe influence of

individual-focused TFL.This strategy allows us to demonstrate the distincteffects ofone aspectof TFL at a

given levelaftercontrolling forthe effectsof the otherTFL aspectat a differentlevel.To examine the

significance of the mediations and the moderated mediated relationships,we employed a Monte Carlo simulation

procedure using the open-source software R (Preacher & Selig,2012).This method more accurately reflects the

asymmetric nature of the sampling distribution of a mediating effect.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables at both individual an

INFLUENCES OF DUAL-FOCUSED TFL ON CREATIVITY

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Results of HLM null models

Prior to hypothesis testing,we examined whether there was significantbetween-team and between-organization

variance in the outcome variables by running null (intercept-only) models.The results showed that 29.33 percent

of the variance in individualcreativity resided atthe team level(χ2

(35)= 85.47,p < .001) and 0.31 percentof the

variance resided at the organization level (χ2

(7)= 10.50, p > .05). In addition, 14.97 percent of the variance in indiv

ual development resided at the team level (χ2

(35)= 58.42; p < .01) and 8.78 percent of the variance resided at the

organization level (χ2

(7)= 17.53; p < .05). We also found that 19.68 percent of the variance in team creativity

at the organization level(χ2

(7)= 15.86,p < .05).The results supported using HLM3 forindividual-levelmodel

estimation and HLM2 for team-level model estimation.

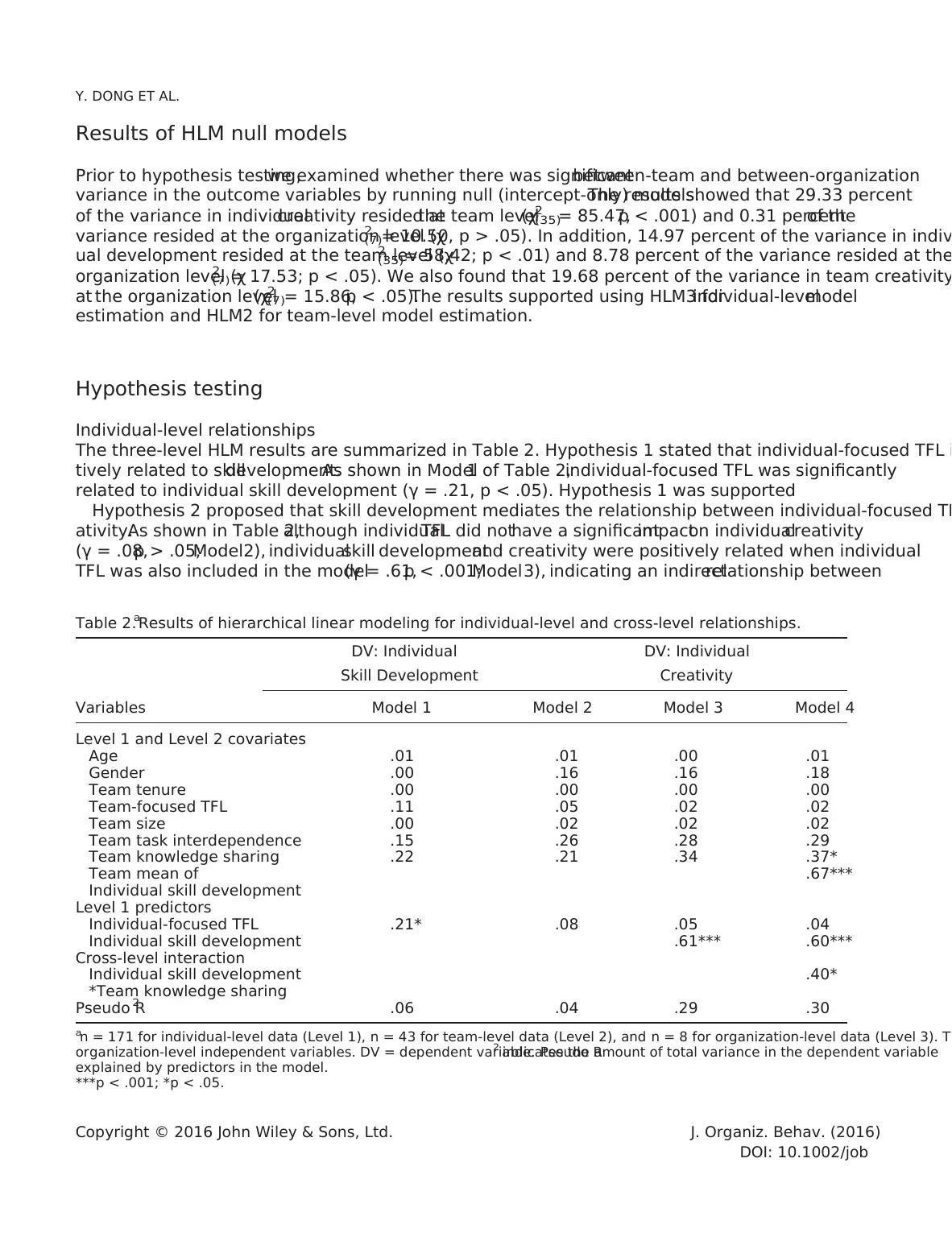

Hypothesis testing

Individual-level relationships

The three-level HLM results are summarized in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 stated that individual-focused TFL i

tively related to skilldevelopment.As shown in Model1 of Table 2,individual-focused TFL was significantly

related to individual skill development (γ = .21, p < .05). Hypothesis 1 was supported

Hypothesis 2 proposed that skill development mediates the relationship between individual-focused TF

ativity.As shown in Table 2,although individualTFL did nothave a significantimpacton individualcreativity

(γ = .08,p > .05;Model2), individualskill developmentand creativity were positively related when individual

TFL was also included in the model(γ = .61,p < .001;Model3), indicating an indirectrelationship between

Table 2.aResults of hierarchical linear modeling for individual-level and cross-level relationships.

DV: Individual DV: Individual

Skill Development Creativity

Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Level 1 and Level 2 covariates

Age .01 .01 .00 .01

Gender .00 .16 .16 .18

Team tenure .00 .00 .00 .00

Team-focused TFL .11 .05 .02 .02

Team size .00 .02 .02 .02

Team task interdependence .15 .26 .28 .29

Team knowledge sharing .22 .21 .34 .37*

Team mean of .67***

Individual skill development

Level 1 predictors

Individual-focused TFL .21* .08 .05 .04

Individual skill development .61*** .60***

Cross-level interaction

Individual skill development .40*

*Team knowledge sharing

Pseudo R2 .06 .04 .29 .30

an = 171 for individual-level data (Level 1), n = 43 for team-level data (Level 2), and n = 8 for organization-level data (Level 3). Th

organization-level independent variables. DV = dependent variable. Pseudo R2 indicates the amount of total variance in the dependent variable

explained by predictors in the model.

***p < .001; *p < .05.

Y. DONG ET AL.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/job

Prior to hypothesis testing,we examined whether there was significantbetween-team and between-organization

variance in the outcome variables by running null (intercept-only) models.The results showed that 29.33 percent

of the variance in individualcreativity resided atthe team level(χ2

(35)= 85.47,p < .001) and 0.31 percentof the