Entry Test Reading Comprehension: Deforestation and Human Uniqueness

VerifiedAdded on 2023/02/06

|9

|2905

|92

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This document presents a reading comprehension assignment comprised of two passages. The first passage delves into the issue of deforestation in the 21st century, analyzing the shift from small-scale efforts to large-scale industrial practices, its drivers like urban population growth and agricultural exports, and its environmental consequences. The passage also explores potential solutions, such as increasing agricultural productivity on existing cleared lands and international efforts to reduce deforestation. The second passage challenges the notion of human uniqueness, particularly in the context of language, by examining communication abilities in other species, including gestures in primates, babbling in dolphins, and the ability of animals to assign meaning to sounds. The assignment includes a series of questions testing comprehension of the passages, requiring identification of key information, understanding of arguments, and completion of sentences with specific details from the text. This assignment provides a comprehensive analysis of complex topics and serves as a valuable tool for enhancing reading comprehension skills.

ENTRY TEST

READING TEST

READING PASSAGE 1

Deforestation in the 21st century

When it comes to cutting down trees, satellite data reveals a shift from the patterns of

the past

A Globally, roughly 13 million hectares of forest are destroyed each year. Such

deforestation has long been driven by farmers desperate to earn a living or by loggers

building new roads into pristine forest. But now new data appears to show that big,

block clearings that reflect industrial deforestation have come to dominate, rather than

these smaller-scale efforts that leave behind long, narrow swaths of cleared land.

Geographer Ruth DeFries of Columbia University and her colleagues used satellite

images to analyse tree-clearing in countries ringing the tropics, representing 98 per

cent of all remaining tropical forest. Instead of the usual ‘fish bone' signature of

deforestation from small-scale operations, large, chunky blocks of cleared land reveal

a new motive for cutting down woods.

B In fact, a statistical analysis of 41 countries showed that forest loss rates were most

closely linked with urban population growth and agricultural exports in the early part

of the 21st century - even overall population growth was not as strong an influence.

‘In previous decades, deforestation was associated with planned colonisation,

resettlement schemes in local areas and farmers clearing land to grow food for

subsistence,' DeFries says. ‘What we’re seeing now is a shift from small-scale

farmers driving deforestation to distant demands from urban growth, agricultural trade

and exports being more important drivers.’

C In other words, the increasing urbanisation of the developing world, as populations

leave rural areas to concentrate in booming cities, is driving deforestation, rather than

containing it. Coupled with this there is an ongoing increase in consumption in the

developed world of products that have an impact on forests, whether furniture, shoe

leather or chicken feed. ‘One of the really striking characteristics of this century is

urbanisation and rapid urban growth in the developing world,’ DeFries says, ‘People

in cities need to eat.’ ‘There’s no surprise there,’ observes Scott Poynton, executive

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 7

READING TEST

READING PASSAGE 1

Deforestation in the 21st century

When it comes to cutting down trees, satellite data reveals a shift from the patterns of

the past

A Globally, roughly 13 million hectares of forest are destroyed each year. Such

deforestation has long been driven by farmers desperate to earn a living or by loggers

building new roads into pristine forest. But now new data appears to show that big,

block clearings that reflect industrial deforestation have come to dominate, rather than

these smaller-scale efforts that leave behind long, narrow swaths of cleared land.

Geographer Ruth DeFries of Columbia University and her colleagues used satellite

images to analyse tree-clearing in countries ringing the tropics, representing 98 per

cent of all remaining tropical forest. Instead of the usual ‘fish bone' signature of

deforestation from small-scale operations, large, chunky blocks of cleared land reveal

a new motive for cutting down woods.

B In fact, a statistical analysis of 41 countries showed that forest loss rates were most

closely linked with urban population growth and agricultural exports in the early part

of the 21st century - even overall population growth was not as strong an influence.

‘In previous decades, deforestation was associated with planned colonisation,

resettlement schemes in local areas and farmers clearing land to grow food for

subsistence,' DeFries says. ‘What we’re seeing now is a shift from small-scale

farmers driving deforestation to distant demands from urban growth, agricultural trade

and exports being more important drivers.’

C In other words, the increasing urbanisation of the developing world, as populations

leave rural areas to concentrate in booming cities, is driving deforestation, rather than

containing it. Coupled with this there is an ongoing increase in consumption in the

developed world of products that have an impact on forests, whether furniture, shoe

leather or chicken feed. ‘One of the really striking characteristics of this century is

urbanisation and rapid urban growth in the developing world,’ DeFries says, ‘People

in cities need to eat.’ ‘There’s no surprise there,’ observes Scott Poynton, executive

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ENTRY TEST

director of the Tropical Forest Trust, a Switzerland-based organisation that helps

businesses implement and manage sustainable forestry in countries such as Brazil,

Congo and Indonesia. ‘It’s not about people chopping down trees. It's all the people

in New York, Europe and elsewhere who want cheap products, primarily food.’

D Dearies argues that in order to help sustain this increasing urban and global demand,

agricultural productivity will need to be increased on lands that have already been

cleared. This means that better crop varieties or better management techniques will

need to be used on the many degraded and abandoned lands in the tropics. And the

Tropical Forest Trust is building management systems to keep illegally harvested

wood from ending up in, for example, deck chairs, as well as expanding its efforts to

look at how to reduce the ‘forest footprint’ of agricultural products such as palm oil.

Poynton says, ‘The point is to give forests value as forests, to keep them as forests

and give them a use as forests. They’re not going to be locked away as national

parks. That’s not going to happen.’

E But it is not all bad news. Halts in tropical deforestation have resulted in forest

regrowth in some areas where tropical lands were previously cleared. And forest

clearing in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical forest, dropped from roughly 1.9

million hectares a year in the 1990s to 1.6 million hectares a year over the last

decade, according to the Brazilian government. 'We know that deforestation has

slowed down in at least the Brazilian Amazon,’ DeFries says. ‘Every place is different.

Every country has its own particular situation, circumstances and driving forces.’

F Regardless of this, deforestation continues, and cutting down forests is one of the

largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions from human activity - a double blow

that both eliminates a biological system to suck up C02 and creates a new source of

greenhouse gases in the form of decaying plants. The United Nations Environment

Programme estimates that slowing such deforestation could reduce some 50 billion

metric tons of C02, or more than a year of global emissions. Indeed, international

climate negotiations continue to attempt to set up a system to encourage this, known

as the UN Development Programme’s fund for reducing emissions from deforestation

and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD). If policies [like REDD] are to

be effective, we need to understand what the driving forces are behind deforestation,

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 8

director of the Tropical Forest Trust, a Switzerland-based organisation that helps

businesses implement and manage sustainable forestry in countries such as Brazil,

Congo and Indonesia. ‘It’s not about people chopping down trees. It's all the people

in New York, Europe and elsewhere who want cheap products, primarily food.’

D Dearies argues that in order to help sustain this increasing urban and global demand,

agricultural productivity will need to be increased on lands that have already been

cleared. This means that better crop varieties or better management techniques will

need to be used on the many degraded and abandoned lands in the tropics. And the

Tropical Forest Trust is building management systems to keep illegally harvested

wood from ending up in, for example, deck chairs, as well as expanding its efforts to

look at how to reduce the ‘forest footprint’ of agricultural products such as palm oil.

Poynton says, ‘The point is to give forests value as forests, to keep them as forests

and give them a use as forests. They’re not going to be locked away as national

parks. That’s not going to happen.’

E But it is not all bad news. Halts in tropical deforestation have resulted in forest

regrowth in some areas where tropical lands were previously cleared. And forest

clearing in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical forest, dropped from roughly 1.9

million hectares a year in the 1990s to 1.6 million hectares a year over the last

decade, according to the Brazilian government. 'We know that deforestation has

slowed down in at least the Brazilian Amazon,’ DeFries says. ‘Every place is different.

Every country has its own particular situation, circumstances and driving forces.’

F Regardless of this, deforestation continues, and cutting down forests is one of the

largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions from human activity - a double blow

that both eliminates a biological system to suck up C02 and creates a new source of

greenhouse gases in the form of decaying plants. The United Nations Environment

Programme estimates that slowing such deforestation could reduce some 50 billion

metric tons of C02, or more than a year of global emissions. Indeed, international

climate negotiations continue to attempt to set up a system to encourage this, known

as the UN Development Programme’s fund for reducing emissions from deforestation

and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD). If policies [like REDD] are to

be effective, we need to understand what the driving forces are behind deforestation,

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 8

ENTRY TEST

DeFries argues. This is particularly important in the light of new pressures that are on

the horizon: the need to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and find alternative

power sources, particularly for private cars, is forcing governments to make products

such as biofuels more readily accessible. This will only exacerbate the pressures on

tropical forests.

G But millions of hectares of pristine forest remain to protect, according to this new

analysis from Columbia University. Approximately 60 percent of the remaining tropical

forests are in countries or areas that currently have little agricultural trade or urban

growth. The amount of forest area in places like central Africa, Guyana and Suriname,

DeFries notes, is huge. ‘There’s a lot of forest that has not yet faced these pressures.’

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage 1 has seven paragraphs, A-G.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

NB You may use any letter more than once.

1 two ways that farming activity might be improved in the future

2 reference to a fall in the rate of deforestation in one area

3 the amount of forest cut down annually

4 how future transport requirements may increase deforestation levels

5 a reference to the typical shape of early deforested areas

6 key reasons why forests in some areas have not been cut down

Questions 7-8

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Which TWO of these reasons do experts give for current patterns of deforestation?

A to provide jobs

B to create transport routes

C to feed city dwellers

D to manufacture low-budget consumer items

E to meet government targets

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 9

DeFries argues. This is particularly important in the light of new pressures that are on

the horizon: the need to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and find alternative

power sources, particularly for private cars, is forcing governments to make products

such as biofuels more readily accessible. This will only exacerbate the pressures on

tropical forests.

G But millions of hectares of pristine forest remain to protect, according to this new

analysis from Columbia University. Approximately 60 percent of the remaining tropical

forests are in countries or areas that currently have little agricultural trade or urban

growth. The amount of forest area in places like central Africa, Guyana and Suriname,

DeFries notes, is huge. ‘There’s a lot of forest that has not yet faced these pressures.’

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage 1 has seven paragraphs, A-G.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

NB You may use any letter more than once.

1 two ways that farming activity might be improved in the future

2 reference to a fall in the rate of deforestation in one area

3 the amount of forest cut down annually

4 how future transport requirements may increase deforestation levels

5 a reference to the typical shape of early deforested areas

6 key reasons why forests in some areas have not been cut down

Questions 7-8

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Which TWO of these reasons do experts give for current patterns of deforestation?

A to provide jobs

B to create transport routes

C to feed city dwellers

D to manufacture low-budget consumer items

E to meet government targets

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ENTRY TEST

Questions 9-10

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

The list below gives some of the impacts of tropical deforestation. Which TWO of these

results are mentioned by the writer of the text?

A local food supplies fall

B soil becomes less fertile

C some areas have new forest growth

D some regions become uninhabitable

E local economies suffer

Questions 11-13

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND/OR A

NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

11 The expression ‘a ..................... ’ is used to assess the amount of wood used in

certain types of production.

12 Greenhouse gases result from the ..................... that remain after trees have

been cut down.

13 About ..................... of the world’s tropical forests have not experienced

deforestation yet.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 10

Questions 9-10

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

The list below gives some of the impacts of tropical deforestation. Which TWO of these

results are mentioned by the writer of the text?

A local food supplies fall

B soil becomes less fertile

C some areas have new forest growth

D some regions become uninhabitable

E local economies suffer

Questions 11-13

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND/OR A

NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

11 The expression ‘a ..................... ’ is used to assess the amount of wood used in

certain types of production.

12 Greenhouse gases result from the ..................... that remain after trees have

been cut down.

13 About ..................... of the world’s tropical forests have not experienced

deforestation yet.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ENTRY TEST

READING PASSAGE 2

So you think humans are unique

There was a time when we thought humans were

special in so many ways. Now we know better. We are

not the only species that feels emotions, empathises

with others or abides by a moral code. Neither are we

the only ones with personalities, cultures and the

ability to design and use tools. Yet we have steadfastly

clung to the notion that one attribute, at least, makes

us unique: we alone have the capacity for language.

Alas, it turns out we are not so special in this respect either. Key to the revolutionary

reassessment of our talent for communication is the way we think about language itself.

Where once it was seen as a monolith, a discrete and singular entity, today scientists

find it is more productive to think of language as a suite of abilities. Viewed this way, it

becomes apparent that the component parts of language are not as unique as the whole.

Take gesture, arguably the starting point for language. Until recently, it was considered

uniquely human - but not any more. Mike Tomasello of the Max Planck Institute for

Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and others have compiled a list of

gestures observed in monkeys, gibbons, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orang-

utans, which reveals that gesticulation plays a large role in their communication. Ape

gestures can involve touch, vocalising or eye movement, and individuals wait until they

have another ape’s attention before making visual or auditory gestures. If their gestures

go unacknowledged, they will often repeat them or touch the recipient.

In an experiment carried out in 2006 by Erica Cartmill and Richard Byrne from the

University of St Andrews in the UK, they got a person to sit on a chair with some highly

desirable food such as banana to one side of them and some bland food such as celery

to the other. The orang-utans, who could see the person and the food from their

enclosures, gestured at their human partners to encourage them to push the desirable

food their way. If the person feigned incomprehension and offered the bland food, the

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 11

READING PASSAGE 2

So you think humans are unique

There was a time when we thought humans were

special in so many ways. Now we know better. We are

not the only species that feels emotions, empathises

with others or abides by a moral code. Neither are we

the only ones with personalities, cultures and the

ability to design and use tools. Yet we have steadfastly

clung to the notion that one attribute, at least, makes

us unique: we alone have the capacity for language.

Alas, it turns out we are not so special in this respect either. Key to the revolutionary

reassessment of our talent for communication is the way we think about language itself.

Where once it was seen as a monolith, a discrete and singular entity, today scientists

find it is more productive to think of language as a suite of abilities. Viewed this way, it

becomes apparent that the component parts of language are not as unique as the whole.

Take gesture, arguably the starting point for language. Until recently, it was considered

uniquely human - but not any more. Mike Tomasello of the Max Planck Institute for

Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and others have compiled a list of

gestures observed in monkeys, gibbons, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orang-

utans, which reveals that gesticulation plays a large role in their communication. Ape

gestures can involve touch, vocalising or eye movement, and individuals wait until they

have another ape’s attention before making visual or auditory gestures. If their gestures

go unacknowledged, they will often repeat them or touch the recipient.

In an experiment carried out in 2006 by Erica Cartmill and Richard Byrne from the

University of St Andrews in the UK, they got a person to sit on a chair with some highly

desirable food such as banana to one side of them and some bland food such as celery

to the other. The orang-utans, who could see the person and the food from their

enclosures, gestured at their human partners to encourage them to push the desirable

food their way. If the person feigned incomprehension and offered the bland food, the

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 11

ENTRY TEST

animals would change their gestures - just as humans would in a similar situation. If the

human seemed to understand while being somewhat confused, giving only half the

preferred food, the apes would repeat and exaggerate their gestures - again in exactly

the same way a human would. Such findings highlight the fact that the gestures of non-

human primates are not merely innate reflexes but are learned, flexible and under

voluntary control - all characteristics that are considered prerequisites for human-like

communication.

As well as gesturing, pre-linguistic infants babble. At about five months, babies start to

make their first speech sounds, which some researchers believe contain a random

selection of all the phonemes humans can produce. But as children learn the language

of their parents, they narrow their sound repertoire to fit the model to which they are

exposed, producing just the sounds of their native language as well as its classic

intonation patterns. Indeed, they lose their polymath talents so effectively that they are

ultimately unable to produce some sounds - think about the difficulty some speakers have

producing the English th.

Dolphin calves also pass through a babbling phase, Laurance Doyle from the SETI

Institute in Mountain View, California, Brenda McCowan from the University of California

at Davis and their colleagues analysed the complexity of baby dolphin sounds and found

it looked remarkably like that of babbling infants, in that the young dolphins had a much

wider repertoire of sound than adults. This suggests that they practise the sounds of their

species, much as human babies do, before they begin to put them together in the way

characteristic of mature dolphins of their species.

Of course, language is more than mere sound - it also has meaning. While the traditional,

cartoonish version of animal communication renders it unclear, unpredictable and

involuntary, it has become clear that various species are able to give meaning to particular

sounds by connecting them with specific ideas. Dolphins use 'signature whistles’, so

called because it appears that they name themselves. Each develops a unique moniker

within the first year of life and uses it whenever it meets another dolphin.

One of the clearest examples of animals making connections between specific sounds

and meanings was demonstrated by Klaus Zuberbuhler and Katie Slocombe of the

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 12

animals would change their gestures - just as humans would in a similar situation. If the

human seemed to understand while being somewhat confused, giving only half the

preferred food, the apes would repeat and exaggerate their gestures - again in exactly

the same way a human would. Such findings highlight the fact that the gestures of non-

human primates are not merely innate reflexes but are learned, flexible and under

voluntary control - all characteristics that are considered prerequisites for human-like

communication.

As well as gesturing, pre-linguistic infants babble. At about five months, babies start to

make their first speech sounds, which some researchers believe contain a random

selection of all the phonemes humans can produce. But as children learn the language

of their parents, they narrow their sound repertoire to fit the model to which they are

exposed, producing just the sounds of their native language as well as its classic

intonation patterns. Indeed, they lose their polymath talents so effectively that they are

ultimately unable to produce some sounds - think about the difficulty some speakers have

producing the English th.

Dolphin calves also pass through a babbling phase, Laurance Doyle from the SETI

Institute in Mountain View, California, Brenda McCowan from the University of California

at Davis and their colleagues analysed the complexity of baby dolphin sounds and found

it looked remarkably like that of babbling infants, in that the young dolphins had a much

wider repertoire of sound than adults. This suggests that they practise the sounds of their

species, much as human babies do, before they begin to put them together in the way

characteristic of mature dolphins of their species.

Of course, language is more than mere sound - it also has meaning. While the traditional,

cartoonish version of animal communication renders it unclear, unpredictable and

involuntary, it has become clear that various species are able to give meaning to particular

sounds by connecting them with specific ideas. Dolphins use 'signature whistles’, so

called because it appears that they name themselves. Each develops a unique moniker

within the first year of life and uses it whenever it meets another dolphin.

One of the clearest examples of animals making connections between specific sounds

and meanings was demonstrated by Klaus Zuberbuhler and Katie Slocombe of the

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ENTRY TEST

University of St Andrews in the UK. They noticed that chimps at Edinburgh Zoo appeared

to make rudimentary references to objects by using distinct cries when they came across

different kinds of food. Highly valued foods such as bread would elicit high-pitched grunts,

less appealing ones, such as an apple, got low-pitched grunts. Zuberbuhler and

Slocombe showed not only that chimps could make distinctions in the way they vocalised

about food, but that other chimps understood what they meant, When played recordings

of grunts that were produced for a specific food, the chimps looked in the place where

that food was usually found. They also searched longer if the cry had signalled a prized

type of food.

Clearly animals do have greater talents for communication than we realised. Humans are

still special, but it is a far more graded, qualified kind of special than it used to be.

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

14 What point does the writer make in the first paragraph?

A We know more about language now than we used to.

B We recognise the importance of talking about emotions.

C We like to believe that language is a strictly human skill.

D We have used tools for longer than some other species.

15 According to the writer, what has changed our view of communication?

A analysing different world languages

B understanding that language involves a range of skills

C studying the different purposes of language

D realising that we can communicate without language

16 The writer quotes the Cartmill and Byrne experiment because it shows

A the similarities in the way humans and apes use gesture.

B the abilities of apes to use gesture in different environments.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 13

University of St Andrews in the UK. They noticed that chimps at Edinburgh Zoo appeared

to make rudimentary references to objects by using distinct cries when they came across

different kinds of food. Highly valued foods such as bread would elicit high-pitched grunts,

less appealing ones, such as an apple, got low-pitched grunts. Zuberbuhler and

Slocombe showed not only that chimps could make distinctions in the way they vocalised

about food, but that other chimps understood what they meant, When played recordings

of grunts that were produced for a specific food, the chimps looked in the place where

that food was usually found. They also searched longer if the cry had signalled a prized

type of food.

Clearly animals do have greater talents for communication than we realised. Humans are

still special, but it is a far more graded, qualified kind of special than it used to be.

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

14 What point does the writer make in the first paragraph?

A We know more about language now than we used to.

B We recognise the importance of talking about emotions.

C We like to believe that language is a strictly human skill.

D We have used tools for longer than some other species.

15 According to the writer, what has changed our view of communication?

A analysing different world languages

B understanding that language involves a range of skills

C studying the different purposes of language

D realising that we can communicate without language

16 The writer quotes the Cartmill and Byrne experiment because it shows

A the similarities in the way humans and apes use gesture.

B the abilities of apes to use gesture in different environments.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 13

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ENTRY TEST

C how food can be used to encourage ape gestures.

D how hard humans find it to interpret ape gestures.

17 In paragraph 7, the writer says that one type of dolphin sound is

A used only when dolphins are in danger.

B heard only at a particular time of day.

C heard at a range of pitch levels.

D used as a form of personal identification.

18 Experiments at Edinburgh Zoo showed that chimps were able to

A use grunts to ask humans for food.

B use pitch changes to express meaning.

C recognise human voices on a recording

D tell the difference between a false grunt and a real one.

Questions 19-23

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

Write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

19 It could be said that language begins with gesture.

20 Ape gestures always consist of head or limb movements.

21 Apes ensure that other apes are aware of their gesturing.

22 Primate and human gestures share some key features.

23 Cartoons present an amusing picture of animal communication.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 14

C how food can be used to encourage ape gestures.

D how hard humans find it to interpret ape gestures.

17 In paragraph 7, the writer says that one type of dolphin sound is

A used only when dolphins are in danger.

B heard only at a particular time of day.

C heard at a range of pitch levels.

D used as a form of personal identification.

18 Experiments at Edinburgh Zoo showed that chimps were able to

A use grunts to ask humans for food.

B use pitch changes to express meaning.

C recognise human voices on a recording

D tell the difference between a false grunt and a real one.

Questions 19-23

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

Write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

19 It could be said that language begins with gesture.

20 Ape gestures always consist of head or limb movements.

21 Apes ensure that other apes are aware of their gesturing.

22 Primate and human gestures share some key features.

23 Cartoons present an amusing picture of animal communication.

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 14

ENTRY TEST

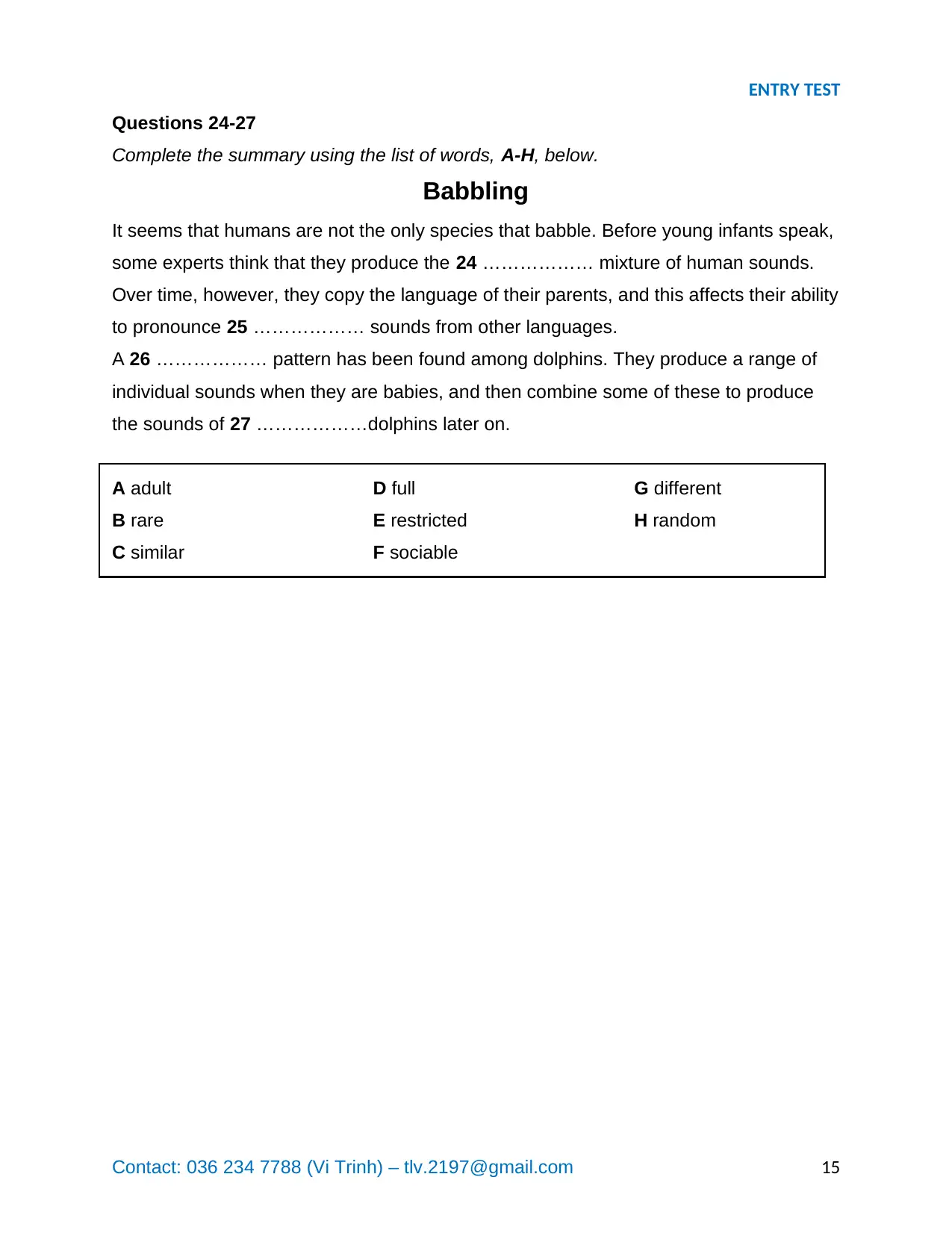

Questions 24-27

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-H, below.

Babbling

It seems that humans are not the only species that babble. Before young infants speak,

some experts think that they produce the 24 ……………… mixture of human sounds.

Over time, however, they copy the language of their parents, and this affects their ability

to pronounce 25 ……………… sounds from other languages.

A 26 ……………… pattern has been found among dolphins. They produce a range of

individual sounds when they are babies, and then combine some of these to produce

the sounds of 27 ………………dolphins later on.

A adult

B rare

C similar

D full

E restricted

F sociable

G different

H random

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 15

Questions 24-27

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-H, below.

Babbling

It seems that humans are not the only species that babble. Before young infants speak,

some experts think that they produce the 24 ……………… mixture of human sounds.

Over time, however, they copy the language of their parents, and this affects their ability

to pronounce 25 ……………… sounds from other languages.

A 26 ……………… pattern has been found among dolphins. They produce a range of

individual sounds when they are babies, and then combine some of these to produce

the sounds of 27 ………………dolphins later on.

A adult

B rare

C similar

D full

E restricted

F sociable

G different

H random

Contact: 036 234 7788 (Vi Trinh) – tlv.2197@gmail.com 15

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.