Strategies to Control Healthcare-Acquired MRSA Transmission: A Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/19

|12

|4091

|470

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the control of healthcare-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) transmission, addressing a critical public health concern. The research utilizes a PICO question framework, examining interventions to curb MRSA spread among patients and nursing staff. A comprehensive literature review, drawing on databases like CINAHL and PubMed, identifies key issues, including the impact of HA-MRSA on mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs. The report explores biological plausibility, highlighting interventions like mupirocin and the importance of hand hygiene. It then outlines methods for problem identification, hazard notification, dose response, and exposure assessment, emphasizing the role of surveillance and risk communication. The study assesses the 5 C's of MRSA transmission and evaluates the effectiveness of interventions such as hand hygiene protocols and health education. The report concludes by emphasizing the importance of risk communication to minimize infection and carriage, stressing the need for effective strategies to protect healthcare workers and patients.

ENVIRONMENTAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

1. Research (PICO) question

1. Research (PICO) question

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Can transmission of healthcare acquired methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) be controlled by multiple

interventions?

P (population) - patients and nursing staffs

I (intervention) – Addressing the need to tackle transmission of methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospital settings and examine the

good practices

C (comparison) – various strategies to minimise the acquisitions of MRSA

O (outcome) – curbing healthcare acquired (HA) complications by MRSA.

2. Background

i. Literature review

The review of several literatures was conducted utilising the search databases

such as CINAHL, PubMed and EBSCOhost, Additionally the search items

include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, control of infection by

MRSA and implementation of control measures for patients and nurses. The

literature search consisted of 53 articles out of which 20 were chosen to identify

the problems, notification on hazard, response to dose, exposure assessment and

characterize the risk.

Globally, healthcare acquired infections are one of the major implications of

mortality. Morbidity and excessive financial burden. Staphylococcus aureus is

most potent nosocomial pathogen leading to healthcare acquired complications

such as pneumonia, meningitis and bacteraemia. The administration of

antibiotics and antimicrobial agents has significantly increased in the recent

past; as a result, there has been a drastic reduction in infection and death rates

(Littman and Viens, 2015). As antibiotics have been the major line of treatment

for a long period, few bacteria have developed resistance towards the antibiotics

thereby rendering the treatment ineffective (Lloyd et al., 2005). Currently,

antibiotic resistance has become a problem worldwide and research is being

done to curb antibiotic resistance (Fukunaga et al., 2016). As such, MRSA, a

strain of S. aureus exhibits resistance against methicillin and is a serious

concern to public health owing to its elevated levels in mortality rates among

the antibiotic resistant organisms.

Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) be controlled by multiple

interventions?

P (population) - patients and nursing staffs

I (intervention) – Addressing the need to tackle transmission of methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospital settings and examine the

good practices

C (comparison) – various strategies to minimise the acquisitions of MRSA

O (outcome) – curbing healthcare acquired (HA) complications by MRSA.

2. Background

i. Literature review

The review of several literatures was conducted utilising the search databases

such as CINAHL, PubMed and EBSCOhost, Additionally the search items

include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, control of infection by

MRSA and implementation of control measures for patients and nurses. The

literature search consisted of 53 articles out of which 20 were chosen to identify

the problems, notification on hazard, response to dose, exposure assessment and

characterize the risk.

Globally, healthcare acquired infections are one of the major implications of

mortality. Morbidity and excessive financial burden. Staphylococcus aureus is

most potent nosocomial pathogen leading to healthcare acquired complications

such as pneumonia, meningitis and bacteraemia. The administration of

antibiotics and antimicrobial agents has significantly increased in the recent

past; as a result, there has been a drastic reduction in infection and death rates

(Littman and Viens, 2015). As antibiotics have been the major line of treatment

for a long period, few bacteria have developed resistance towards the antibiotics

thereby rendering the treatment ineffective (Lloyd et al., 2005). Currently,

antibiotic resistance has become a problem worldwide and research is being

done to curb antibiotic resistance (Fukunaga et al., 2016). As such, MRSA, a

strain of S. aureus exhibits resistance against methicillin and is a serious

concern to public health owing to its elevated levels in mortality rates among

the antibiotic resistant organisms.

MRSA or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus has its effect in precisely

the similar manner as that of Staphylococcus aureus and leads the exact manner

of infections and sufferings (Lee et al., 2018). MRSA is different from the other

is because of its resistance to some antibiotics. There are various antibiotics

which are effective in such infections but it may be a bit risky to use as it might

have chances to cause severe side effects (Turner et al., 2019). Though,

development of the MRSA infection is very not as much common as for normal

people, but it is more frequent for the individuals who obtain Methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus to be transporters (Harkins et al., 2017). These

people are often called as ‘colonised’ people, which states that the organism

exists without harming the individual, on their skin or in their nasal region or

throat, and are found to be not cause any difficulties related to health. one of the

amendments that has been made by the legal agencies is patient advocacy in

condition of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection (Galar et al.,

2019). Patient advocacy provides the right to the person take his/her health care

related as well as treatment related decision and if not possible they can hire

their personal advocates.

Patient advocacy and Personal advocacy is permitted to patients admitted to

health care settings which are licensed under the chapter 405. The legal

amendment states that the patient has total right to choose personal advocate

and the advocate must be with the patient in every process of the examination,

treatment and effective result while suffering from infection due to Methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Werner & Shaban, 2018). The patients have

the authority to recruit more than one personal advocate for themselves. The

patient advocates role is to help the patient make effective decisions regarding

the health, treatment and recovery. The healthcare has the right to limit the

advocates presence in areas where it may risk the patient’s health such as sterile

chambers prepared for the patient as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus has the high chance of spreading. In any circumstance, if the patient

advocate is not permitted to stay with the patient, the health care setting is

bound to provide a written application with detailed reason behind not

permitting the advocate (Walrath et al., 2015). The copies should be provided to

the patient as well as the advocate. It is necessary for the patient as well as the

nursing staff to practice protective measures in order to avoid the spread of the

infection (Werner, Zimmerman & Elder, 2016). The nursing staff needs to

follow basic rules such as keeping the patient in a separate chamber that needs

to be sterile enough to avoid the infection to grow or spread. The nurses at the

same point needs to preserve them from getting infected thus they need to use

the similar manner as that of Staphylococcus aureus and leads the exact manner

of infections and sufferings (Lee et al., 2018). MRSA is different from the other

is because of its resistance to some antibiotics. There are various antibiotics

which are effective in such infections but it may be a bit risky to use as it might

have chances to cause severe side effects (Turner et al., 2019). Though,

development of the MRSA infection is very not as much common as for normal

people, but it is more frequent for the individuals who obtain Methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus to be transporters (Harkins et al., 2017). These

people are often called as ‘colonised’ people, which states that the organism

exists without harming the individual, on their skin or in their nasal region or

throat, and are found to be not cause any difficulties related to health. one of the

amendments that has been made by the legal agencies is patient advocacy in

condition of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection (Galar et al.,

2019). Patient advocacy provides the right to the person take his/her health care

related as well as treatment related decision and if not possible they can hire

their personal advocates.

Patient advocacy and Personal advocacy is permitted to patients admitted to

health care settings which are licensed under the chapter 405. The legal

amendment states that the patient has total right to choose personal advocate

and the advocate must be with the patient in every process of the examination,

treatment and effective result while suffering from infection due to Methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Werner & Shaban, 2018). The patients have

the authority to recruit more than one personal advocate for themselves. The

patient advocates role is to help the patient make effective decisions regarding

the health, treatment and recovery. The healthcare has the right to limit the

advocates presence in areas where it may risk the patient’s health such as sterile

chambers prepared for the patient as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus has the high chance of spreading. In any circumstance, if the patient

advocate is not permitted to stay with the patient, the health care setting is

bound to provide a written application with detailed reason behind not

permitting the advocate (Walrath et al., 2015). The copies should be provided to

the patient as well as the advocate. It is necessary for the patient as well as the

nursing staff to practice protective measures in order to avoid the spread of the

infection (Werner, Zimmerman & Elder, 2016). The nursing staff needs to

follow basic rules such as keeping the patient in a separate chamber that needs

to be sterile enough to avoid the infection to grow or spread. The nurses at the

same point needs to preserve them from getting infected thus they need to use

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

protections such as gloves, protective aprons, hand hygiene and other cleaning

and disinfecting measures (Garvey et al., 2019).

ii. Rational and significance:

One of the studies revealed that the risk of mortality was twice higher than that

of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus which significantly increases the duration of

stay, utilizing resources of the healthcare facilities, medication and extra nursing

staffs for care thus leading to economic burden for the patient (Kundrapu et al.,

2012). MRSA can survive on hospital surfaces such as catheters, surgical

instruments, hospital floor and furniture and cause outbreaks if left

uncontrolled. Consequently, it is important to understand the disease burden and

the potential factors associated with the spread of infection in order to manage

HA-MRSA (Fox et al., 2015). Furthermore, identifying the risk factors will

ensure formulation of guidelines and recommendations for prevention policies,

in particular, good hand hygiene, adequate care of vascular devices and

cleanliness of the hospital environment (Minhas et al., 2011).

iii. Biological plausibility:

The biological plausibility includes prolonged bacteraemia resulting in severe

complications such as meningitis and septic shock. In addition, these

complications result in prolonged bacteraemia (Green, 2015). In addition,

MRSA based interventions have a significant impact in surgery, for instance

mupirocin administered intranasally has significantly minimised MRSA

associated infections at the site of surgery in orthopaedic and cardiothoracic

surgery, however not effective in general surgery. The causes for such reasons

remain unclear, however a dosage regimen to decolonise MRSA prior to

surgery and development of rapid diagnostic assays can be effective to curb

MRSA transmission. Also, utilisation of two interventions such as hygiene and

antibiotics or placement of patients in isolation rooms or proper screening can

be effective in the prevention and control.

and disinfecting measures (Garvey et al., 2019).

ii. Rational and significance:

One of the studies revealed that the risk of mortality was twice higher than that

of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus which significantly increases the duration of

stay, utilizing resources of the healthcare facilities, medication and extra nursing

staffs for care thus leading to economic burden for the patient (Kundrapu et al.,

2012). MRSA can survive on hospital surfaces such as catheters, surgical

instruments, hospital floor and furniture and cause outbreaks if left

uncontrolled. Consequently, it is important to understand the disease burden and

the potential factors associated with the spread of infection in order to manage

HA-MRSA (Fox et al., 2015). Furthermore, identifying the risk factors will

ensure formulation of guidelines and recommendations for prevention policies,

in particular, good hand hygiene, adequate care of vascular devices and

cleanliness of the hospital environment (Minhas et al., 2011).

iii. Biological plausibility:

The biological plausibility includes prolonged bacteraemia resulting in severe

complications such as meningitis and septic shock. In addition, these

complications result in prolonged bacteraemia (Green, 2015). In addition,

MRSA based interventions have a significant impact in surgery, for instance

mupirocin administered intranasally has significantly minimised MRSA

associated infections at the site of surgery in orthopaedic and cardiothoracic

surgery, however not effective in general surgery. The causes for such reasons

remain unclear, however a dosage regimen to decolonise MRSA prior to

surgery and development of rapid diagnostic assays can be effective to curb

MRSA transmission. Also, utilisation of two interventions such as hygiene and

antibiotics or placement of patients in isolation rooms or proper screening can

be effective in the prevention and control.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3. Methods

i. Problem identification

The chances of acquiring MRSA at healthcare increase with immunocompetent

and immune susceptible patients, elderly, recipients of organ transplant, cancer

patients with prolonged chemotherapy, diabetics, chronic diseases, steroid

therapy, intravenous drug users, and those with prolonged medication with

antibiotics. The Centre for Disease Control states the 5 C’s such as crowding,

skin-skin contact especially between patients, their family members and nursing

staffs in the hospital settings, compromised skin, contamination and lack of

cleanliness as the prime factors for transmission of MRSA. In addition, patients

with previous colonisation with the strain, indwelling devices such as prolonged

vascular access, urinary catheter, endoscopic gastrostomy and drains in wound

(Bode et al., 2010). Furthermore, chronic wounds and admission in high risk

areas in the hospitals such as intensive critical care unit and burns may also be a

major risk problem with MRSA (Haverstick et al., 2017).

One of the studies conducted by Fox et al. (2015) assessed the rate of MRSA

associated hospital infections such as urinary tract infection due to in-dwellers

and central line associated systemic infection over a period of twelve months.

The study was based on a cardiovascular intensive care unit which is considered

a high-risk area where 1 nurse took care of 2 patients. A protocol for hand

hygiene was followed in the premises by patients that were admitted in addition

the nursing staffs of that unit. The intervention consisted of wiping the hand of

patients thrice a day using the wipes containing the disinfectant chlorohexidine

gluconate (2%) and the medial report was noted down. Results revealed a

reduction in the mean monthly rate of catheter associated urinary tract infection

from 9.1 to 5.6 in one thousand catheter days and a reduction from 1 to 0.50 in

one thousand catheter days for central line associated bloodstream infections.

These results indicated that following the protocol for hand hygiene

significantly reduced MRSA associated hospital infections than the results

obtained prior to the twelve-month period (Fox et al., 2015).

In another study, assessment of providing health education to patients, nursing

staffs and usage of hand hygiene protocol was performed to minimise MRSA

transmission via increased usage of hand hygiene protocol and educating the

patients to utilise hand hygiene wipes. This study was conducted for over a 19-

i. Problem identification

The chances of acquiring MRSA at healthcare increase with immunocompetent

and immune susceptible patients, elderly, recipients of organ transplant, cancer

patients with prolonged chemotherapy, diabetics, chronic diseases, steroid

therapy, intravenous drug users, and those with prolonged medication with

antibiotics. The Centre for Disease Control states the 5 C’s such as crowding,

skin-skin contact especially between patients, their family members and nursing

staffs in the hospital settings, compromised skin, contamination and lack of

cleanliness as the prime factors for transmission of MRSA. In addition, patients

with previous colonisation with the strain, indwelling devices such as prolonged

vascular access, urinary catheter, endoscopic gastrostomy and drains in wound

(Bode et al., 2010). Furthermore, chronic wounds and admission in high risk

areas in the hospitals such as intensive critical care unit and burns may also be a

major risk problem with MRSA (Haverstick et al., 2017).

One of the studies conducted by Fox et al. (2015) assessed the rate of MRSA

associated hospital infections such as urinary tract infection due to in-dwellers

and central line associated systemic infection over a period of twelve months.

The study was based on a cardiovascular intensive care unit which is considered

a high-risk area where 1 nurse took care of 2 patients. A protocol for hand

hygiene was followed in the premises by patients that were admitted in addition

the nursing staffs of that unit. The intervention consisted of wiping the hand of

patients thrice a day using the wipes containing the disinfectant chlorohexidine

gluconate (2%) and the medial report was noted down. Results revealed a

reduction in the mean monthly rate of catheter associated urinary tract infection

from 9.1 to 5.6 in one thousand catheter days and a reduction from 1 to 0.50 in

one thousand catheter days for central line associated bloodstream infections.

These results indicated that following the protocol for hand hygiene

significantly reduced MRSA associated hospital infections than the results

obtained prior to the twelve-month period (Fox et al., 2015).

In another study, assessment of providing health education to patients, nursing

staffs and usage of hand hygiene protocol was performed to minimise MRSA

transmission via increased usage of hand hygiene protocol and educating the

patients to utilise hand hygiene wipes. This study was conducted for over a 19-

month period and results indicated that the rates for MRSA drastically reduced

by 63% post-intervention (Strigley et al., 2016).

ii. Hazard notification:

In cases where the laboratory in the healthcare facility confirms MRSA that has

been isolated from a patient who is admitted in the hospital, the person in-

charge, either the general practitioner, coordinator of infection control, the

nursing staffs who take care of that patient or the unit and personnel who are

recommended as per the guidelines of the healthcare facilities (Peters et al.,

2017). In case the notification of hazard occurred after the working hours of the

unit responsible for infection control and prevention, there must be a system to

ensure the notification is conveyed to the personnel in the unit at the earliest.

However, the duty nurse can be informed in such scenario.

iii. Dose response:

Vancomycin hydrochloride is considered as the gold standard for treating

MRSA associated infections. However new antibiotics such as dalfopristin,

linezolid and tigecycline are mentioned to have delirious effects on MRSA (Lee

et al., 2013), however they are expensive and not much of clinical research has

been done. In addition, sub-minimum inhibitory concentration of beta-lactam

antibiotics induced biofilm formation and the dose response was not effective.

iv. Exposure assessment:

MRSA assessment is based on the results of culture and system to screen

patients with confirmed history for MRSA. Clinical isolates from MRSA

infected patients must be the major component for management of surveillance

within the healthcare settings (Currie et al., 2013). Facilities that follow strict

surveillance program can identify the reservoirs or carriers of MRSA. It is

mandatory for exposure assessment to track patients who are positive for

MRSA via screening based on location, patient proportion and service provide

clinically. The data should be consistent for the evaluation to be relevant and

appropriate and comparative for studies prior and after therapy (Mishal et al.,

2001). The prevalence of MRSA is the ratio of the patients who colonize and

by 63% post-intervention (Strigley et al., 2016).

ii. Hazard notification:

In cases where the laboratory in the healthcare facility confirms MRSA that has

been isolated from a patient who is admitted in the hospital, the person in-

charge, either the general practitioner, coordinator of infection control, the

nursing staffs who take care of that patient or the unit and personnel who are

recommended as per the guidelines of the healthcare facilities (Peters et al.,

2017). In case the notification of hazard occurred after the working hours of the

unit responsible for infection control and prevention, there must be a system to

ensure the notification is conveyed to the personnel in the unit at the earliest.

However, the duty nurse can be informed in such scenario.

iii. Dose response:

Vancomycin hydrochloride is considered as the gold standard for treating

MRSA associated infections. However new antibiotics such as dalfopristin,

linezolid and tigecycline are mentioned to have delirious effects on MRSA (Lee

et al., 2013), however they are expensive and not much of clinical research has

been done. In addition, sub-minimum inhibitory concentration of beta-lactam

antibiotics induced biofilm formation and the dose response was not effective.

iv. Exposure assessment:

MRSA assessment is based on the results of culture and system to screen

patients with confirmed history for MRSA. Clinical isolates from MRSA

infected patients must be the major component for management of surveillance

within the healthcare settings (Currie et al., 2013). Facilities that follow strict

surveillance program can identify the reservoirs or carriers of MRSA. It is

mandatory for exposure assessment to track patients who are positive for

MRSA via screening based on location, patient proportion and service provide

clinically. The data should be consistent for the evaluation to be relevant and

appropriate and comparative for studies prior and after therapy (Mishal et al.,

2001). The prevalence of MRSA is the ratio of the patients who colonize and

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

are infected with MRSA and the number of patients in the population study at

one point of time. In addition, the exposure assessment should possess

definitions for all the measurements. Acquisition of the infection is related to

hospitalization if MRSA infection is detected more than 2 days following

admission (Borg et al., 2012).

At hospitals it is important to follow and notify the rates of prevalence for every

high-risk unit (Dickmann et al., 2017). It is important to identify populations

and service lines at high risk, analyse the transmission of MRSA in the

population of patients over a period of time before and after the interventions,

compare the spread of MRSA to evaluate whether multiple interventions are

necessary, prioritise interventions for specific patient care units and among

specific populations and develop a dosage regimen and effectively

communicate to the nursing staffs. One of the evaluations for the exposure

assessment of MRSA is determined as follows:

No. of new MRSA cases per unit per month/no. of patient days * 1000 = HA-

MRSA rates per 1000unit patient days

4. Risk communication:

The communication of risks involves several approaches to reduce the spread of

MRSA in healthcare settings such as wiping the hands regularly to minimise

infection and carriage. Contamination of the hand of healthcare staffs is one of

the major reasons for the transmission of MRSA among patients. Hand gloves,

instruments and aprons utilised by the healthcare workers may be the source of

infection. One of the studies conducted by Boyce et al (1997) revealed that 42%

of the gloves used by the nurse are contaminated however they had no direct

contact with the MRSA infected patients but experienced contact with the

surface of the room where the patients were admitted.

The clothing of the nurses is considered as one of the factors for transmission

among patients. Instruments utilised in the patient’s care such as thermometers,

blood pressure monitoring devices and otoscopes act as agents for the spread of

infection (Schoeder A et al., 2015). In addition, the use of antibiotics is

considered a risk communication factor. Furthermore, most of the complaints

from patients and their family members include improper communication about

MRSA. The groups for patient advocacy have given importance for rapid and

increased information on MRSA in hospital settings (Gigerenzer and Werwerth,

2013). This communication strategy will assist in clinical governance and

one point of time. In addition, the exposure assessment should possess

definitions for all the measurements. Acquisition of the infection is related to

hospitalization if MRSA infection is detected more than 2 days following

admission (Borg et al., 2012).

At hospitals it is important to follow and notify the rates of prevalence for every

high-risk unit (Dickmann et al., 2017). It is important to identify populations

and service lines at high risk, analyse the transmission of MRSA in the

population of patients over a period of time before and after the interventions,

compare the spread of MRSA to evaluate whether multiple interventions are

necessary, prioritise interventions for specific patient care units and among

specific populations and develop a dosage regimen and effectively

communicate to the nursing staffs. One of the evaluations for the exposure

assessment of MRSA is determined as follows:

No. of new MRSA cases per unit per month/no. of patient days * 1000 = HA-

MRSA rates per 1000unit patient days

4. Risk communication:

The communication of risks involves several approaches to reduce the spread of

MRSA in healthcare settings such as wiping the hands regularly to minimise

infection and carriage. Contamination of the hand of healthcare staffs is one of

the major reasons for the transmission of MRSA among patients. Hand gloves,

instruments and aprons utilised by the healthcare workers may be the source of

infection. One of the studies conducted by Boyce et al (1997) revealed that 42%

of the gloves used by the nurse are contaminated however they had no direct

contact with the MRSA infected patients but experienced contact with the

surface of the room where the patients were admitted.

The clothing of the nurses is considered as one of the factors for transmission

among patients. Instruments utilised in the patient’s care such as thermometers,

blood pressure monitoring devices and otoscopes act as agents for the spread of

infection (Schoeder A et al., 2015). In addition, the use of antibiotics is

considered a risk communication factor. Furthermore, most of the complaints

from patients and their family members include improper communication about

MRSA. The groups for patient advocacy have given importance for rapid and

increased information on MRSA in hospital settings (Gigerenzer and Werwerth,

2013). This communication strategy will assist in clinical governance and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

adhering to professional and ethical guidelines as per the national and hospital

guidelines. Proper education to the patients will ensure the patients informing

about the requirement for screening and subsequent entry for admission in the

hospital. Furthermore, sharing of information and hand hygiene can reduce the

transmission of MRSA. Lack of knowledge about informing the status of

MRSA is one of the barriers that result in the spread of infection (Fukunaga et

al., 2017). In addition, the process of documentation must be made simple and

the feedback from audits on the patient proportions have to be recorded. Also,

the patient’s MRSA-positive status should be notified to the new healthcare

settings where the patients were to be transferred. Collaboration with nursing

staffs, planning in the discharge and management of patient’s case are effective

measures. In addition, it is essential to develop a transfer tool that is like the tool

developed by the Centre for Disease Control.

Major findings in the developing strategies are:

i) hand hygiene with chlorhexidine significantly reduced the acquisition of

MRSA and systemic infections (Climno et al., 2013)

ii) information about screening and outcomes to the patient

iii) disinfection of touch surfaces in patient’s rooms infected with MRSA

significantly minimised the transmission of infection via hands of nursing staffs

and other healthcare workers who took care of the patients.

iv) patients with positive MRSA can have recurrent infections due to drug

resistance, prolongEd admission in hospitals and be a carrier for MRSA

(Littman and Viens, 2015).

v) Isolation of contact and deceased patients from other patients in the unit and

nurses.

5. Conclusion:

The healthcare workers, nurses who work in accordance with the patients

infected with MRSA must abide by the guidelines and implement effective

strategies to prevent the transmission of MRSA within the healthcare settings.

In addition, education about MRSA to patients, prompt techniques of

disinfection can effectively prevent and control MRSA transmission.

Consequently, multiple interventions can promote effective management of

MRSA in hospitals. This will prevent prolonged stays in the hospital, charges

that cannot be reimbursed from Medicare and Medicaid and ensure reduction in

the financial burden of the patient.

6. References

guidelines. Proper education to the patients will ensure the patients informing

about the requirement for screening and subsequent entry for admission in the

hospital. Furthermore, sharing of information and hand hygiene can reduce the

transmission of MRSA. Lack of knowledge about informing the status of

MRSA is one of the barriers that result in the spread of infection (Fukunaga et

al., 2017). In addition, the process of documentation must be made simple and

the feedback from audits on the patient proportions have to be recorded. Also,

the patient’s MRSA-positive status should be notified to the new healthcare

settings where the patients were to be transferred. Collaboration with nursing

staffs, planning in the discharge and management of patient’s case are effective

measures. In addition, it is essential to develop a transfer tool that is like the tool

developed by the Centre for Disease Control.

Major findings in the developing strategies are:

i) hand hygiene with chlorhexidine significantly reduced the acquisition of

MRSA and systemic infections (Climno et al., 2013)

ii) information about screening and outcomes to the patient

iii) disinfection of touch surfaces in patient’s rooms infected with MRSA

significantly minimised the transmission of infection via hands of nursing staffs

and other healthcare workers who took care of the patients.

iv) patients with positive MRSA can have recurrent infections due to drug

resistance, prolongEd admission in hospitals and be a carrier for MRSA

(Littman and Viens, 2015).

v) Isolation of contact and deceased patients from other patients in the unit and

nurses.

5. Conclusion:

The healthcare workers, nurses who work in accordance with the patients

infected with MRSA must abide by the guidelines and implement effective

strategies to prevent the transmission of MRSA within the healthcare settings.

In addition, education about MRSA to patients, prompt techniques of

disinfection can effectively prevent and control MRSA transmission.

Consequently, multiple interventions can promote effective management of

MRSA in hospitals. This will prevent prolonged stays in the hospital, charges

that cannot be reimbursed from Medicare and Medicaid and ensure reduction in

the financial burden of the patient.

6. References

Fox C., Wavra T., Drake D., Mulligan D., Bennett Y., Nelson C., Kirkwood P.,

Jones L., Bader M. (2015). Use of a patient hand hygiene protocol to reduce

hospital acquired infections and improve nurses hand washing. American

Journal of Critical Care. Vol 24 (3). 217-223.

Strigley J. A., Furness C. D., Gardam M. (2016). Interventions to improve

patient hand hygiene: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection. Vol 94

(1). 23-29

Haverstick S., Goodrich C., Freeman R., James S., Kullar R., Ahrens M. (2017).

Patient’s hand washing and reducing hospital acquired infection. Critical Care

Nurse. Vol 37 (3).

Climno M. W., Yokoe D. S., Warren D. K., Perl T. M., Bolon M., Herwaldt

L.A., Wong E. S. (2013). Effect of daily chlorohexidine bathing on hospital-

acquired infection. N Engl J Med. Vol 368. 533-542

Currie K., Knussen C., Price L., Reilly J. (2013). Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus screening aas a patient safety initiative using patients

experiences to improve the quality of screening practices. Journal of Clinical

Nursing. Doi: 10.111/joen.12386

Kundrapu s., Sunkesula V., Jury I. A., Sitzlar B. M., Donskey C. J. (2012).

Daily disinfection of high touch surfaces in isolation rooms to reduce

contamination of healthcare workers hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiology.

Vol 33 (10). 1039-1042

Minhas P., Perl T. M., Carroll K. C., Shepard J. W., Shagraw K. A et al (2011).

Risk factors for positive admission surveillance cultures for methicillin resistant

Staphylococcis aureus and vancomycin-resistant eneterococci in neurocritical

care unit. Critical care Med. Vol 39. 2322-2329

Mishal J., Sherer Y., Levin Y., Katz D., Embon E. (2001). Two stage evaluation

and intravention program for control of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus

aureus in the hospital setting. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. Vol

33 (7). 498-501

Schroeder A., Schroeder M. A., D’Amico F (2009). What’s growing on your

stethoscope? And what you can do about it. J Fam Pract. Vol 58. 408-409

Dickmann P et al. (2017). Communicating the risk of MRSA: the role of

clinical practice, regulation and other policies in five European countries.

Frontiers in Public Health. Vol 5 (44). Doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017/00044

Jones L., Bader M. (2015). Use of a patient hand hygiene protocol to reduce

hospital acquired infections and improve nurses hand washing. American

Journal of Critical Care. Vol 24 (3). 217-223.

Strigley J. A., Furness C. D., Gardam M. (2016). Interventions to improve

patient hand hygiene: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection. Vol 94

(1). 23-29

Haverstick S., Goodrich C., Freeman R., James S., Kullar R., Ahrens M. (2017).

Patient’s hand washing and reducing hospital acquired infection. Critical Care

Nurse. Vol 37 (3).

Climno M. W., Yokoe D. S., Warren D. K., Perl T. M., Bolon M., Herwaldt

L.A., Wong E. S. (2013). Effect of daily chlorohexidine bathing on hospital-

acquired infection. N Engl J Med. Vol 368. 533-542

Currie K., Knussen C., Price L., Reilly J. (2013). Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus screening aas a patient safety initiative using patients

experiences to improve the quality of screening practices. Journal of Clinical

Nursing. Doi: 10.111/joen.12386

Kundrapu s., Sunkesula V., Jury I. A., Sitzlar B. M., Donskey C. J. (2012).

Daily disinfection of high touch surfaces in isolation rooms to reduce

contamination of healthcare workers hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiology.

Vol 33 (10). 1039-1042

Minhas P., Perl T. M., Carroll K. C., Shepard J. W., Shagraw K. A et al (2011).

Risk factors for positive admission surveillance cultures for methicillin resistant

Staphylococcis aureus and vancomycin-resistant eneterococci in neurocritical

care unit. Critical care Med. Vol 39. 2322-2329

Mishal J., Sherer Y., Levin Y., Katz D., Embon E. (2001). Two stage evaluation

and intravention program for control of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus

aureus in the hospital setting. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. Vol

33 (7). 498-501

Schroeder A., Schroeder M. A., D’Amico F (2009). What’s growing on your

stethoscope? And what you can do about it. J Fam Pract. Vol 58. 408-409

Dickmann P et al. (2017). Communicating the risk of MRSA: the role of

clinical practice, regulation and other policies in five European countries.

Frontiers in Public Health. Vol 5 (44). Doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017/00044

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Lee et al. (2013). Comparison of strategies to reduce methicillin resistant

Staphylococcus aureus rates in surgical patients: a controlled multicentre

intervention trial. Infectious Diseases. Vol 3 (9).

Green B. N. (2012). Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview

for manual therapists. J Chirop Med. Vol 11 (1), 64-75

Gigerenzer G., Wegwarth O. (2013). Five-year survival rates can mislead. BMJ.

Vol 348

Borg M. A., Camilleri L., Waisfisz B. (2012). Understanding the epidemiology

of MRSA in Europe: do we need to think outside the box? J Hosp Infect. Vol 81

(4). 251-256

Lloyd S. J. O., Svhreiber S. J., Kopp P. E et al. (2005). Superspreading and the

effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. Vol 438. 355-359

Bode L. G., Kloytmans J .A., Wertherirn H. F. et al. (2010). Preventing surgical

site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Eng J Med. 2010.

Vol 362. 9-17.

Fukunaga B. T., Sumida W. K., Taira D. A., Davis J. W., Seto T. B. (2016).

Hospital acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia

related to Medicare antibiotic prescriptions: a state level analysis. Hawaii J Med

Public Health. Vol 75 (10). 303-309

Littman J., Viens A. M. (2015). The ethical significance of antimicrobial

resistance. Public Health Ethics. Vol 8 (3). 209-224.

Peters C., Dulon M., Kleimuller O., Nienhaus A., Schabion A. (2017). MRSA

prevalence and risk factors among health personnel and residents in nursing

homes in Hamburg, Germany-a cross sectional study. PLoS One. Vol 12 (1).

E0169425

Galar, A., Weil, A. A., Dudzinski, D. M., Muñoz, P., & Siedner, M. J. (2019).

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis:

Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and

Management. Clinical microbiology reviews, 32(2), e00041-18.

Garvey, M. I., Bradley, C. W., Wilkinson, M. A., Holden, K. L., Clewer, V., &

Holden, E. (2019). The value of the infection prevention and control nurse led

MRSA ward round. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 8(1), 53.

Harkins, C. P., Pichon, B., Doumith, M., Parkhill, J., Westh, H., Tomasz, A., ...

& Holden, M. T. (2017). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerged

Staphylococcus aureus rates in surgical patients: a controlled multicentre

intervention trial. Infectious Diseases. Vol 3 (9).

Green B. N. (2012). Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview

for manual therapists. J Chirop Med. Vol 11 (1), 64-75

Gigerenzer G., Wegwarth O. (2013). Five-year survival rates can mislead. BMJ.

Vol 348

Borg M. A., Camilleri L., Waisfisz B. (2012). Understanding the epidemiology

of MRSA in Europe: do we need to think outside the box? J Hosp Infect. Vol 81

(4). 251-256

Lloyd S. J. O., Svhreiber S. J., Kopp P. E et al. (2005). Superspreading and the

effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. Vol 438. 355-359

Bode L. G., Kloytmans J .A., Wertherirn H. F. et al. (2010). Preventing surgical

site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Eng J Med. 2010.

Vol 362. 9-17.

Fukunaga B. T., Sumida W. K., Taira D. A., Davis J. W., Seto T. B. (2016).

Hospital acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia

related to Medicare antibiotic prescriptions: a state level analysis. Hawaii J Med

Public Health. Vol 75 (10). 303-309

Littman J., Viens A. M. (2015). The ethical significance of antimicrobial

resistance. Public Health Ethics. Vol 8 (3). 209-224.

Peters C., Dulon M., Kleimuller O., Nienhaus A., Schabion A. (2017). MRSA

prevalence and risk factors among health personnel and residents in nursing

homes in Hamburg, Germany-a cross sectional study. PLoS One. Vol 12 (1).

E0169425

Galar, A., Weil, A. A., Dudzinski, D. M., Muñoz, P., & Siedner, M. J. (2019).

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis:

Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and

Management. Clinical microbiology reviews, 32(2), e00041-18.

Garvey, M. I., Bradley, C. W., Wilkinson, M. A., Holden, K. L., Clewer, V., &

Holden, E. (2019). The value of the infection prevention and control nurse led

MRSA ward round. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 8(1), 53.

Harkins, C. P., Pichon, B., Doumith, M., Parkhill, J., Westh, H., Tomasz, A., ...

& Holden, M. T. (2017). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerged

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

long before the introduction of methicillin into clinical practice. Genome

biology, 18(1), 130.

Lee, A. S., de Lencastre, H., Garau, J., Kluytmans, J., Malhotra-Kumar, S.,

Peschel, A., & Harbarth, S. (2018). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Nature reviews Disease primers, 4, 18033.

Turner, N. A., Sharma-Kuinkel, B. K., Maskarinec, S. A., Eichenberger, E. M.,

Shah, P. P., Carugati, M., ... & Fowler, V. G. (2019). Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nature

Reviews Microbiology, 1.

Walrath, J. M., Immelt, S., Ray, E. M., van Graafeiland, B., & Himmelfarb, C.

D. (2015). Preparing patient safety advocates: Evaluation of nursing students’

reported experience with authority gradients in a hospital setting. Nurse

educator, 40(4), 174-178.

Werner, C., & Shaban, R. Z. (2018). Successfully clearing discharged patients

of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Opportunities for the prevention

and containment of antimicrobial resistance. Infection, disease & health, 23(1),

57-62.

Werner, C., Zimmerman, P. A., & Elder, E. (2016). Hospital based clearance of

patients with skin and soft tissue methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA): a systematic review of the literature. Infection, Disease & Health,

21(2), 72-83.

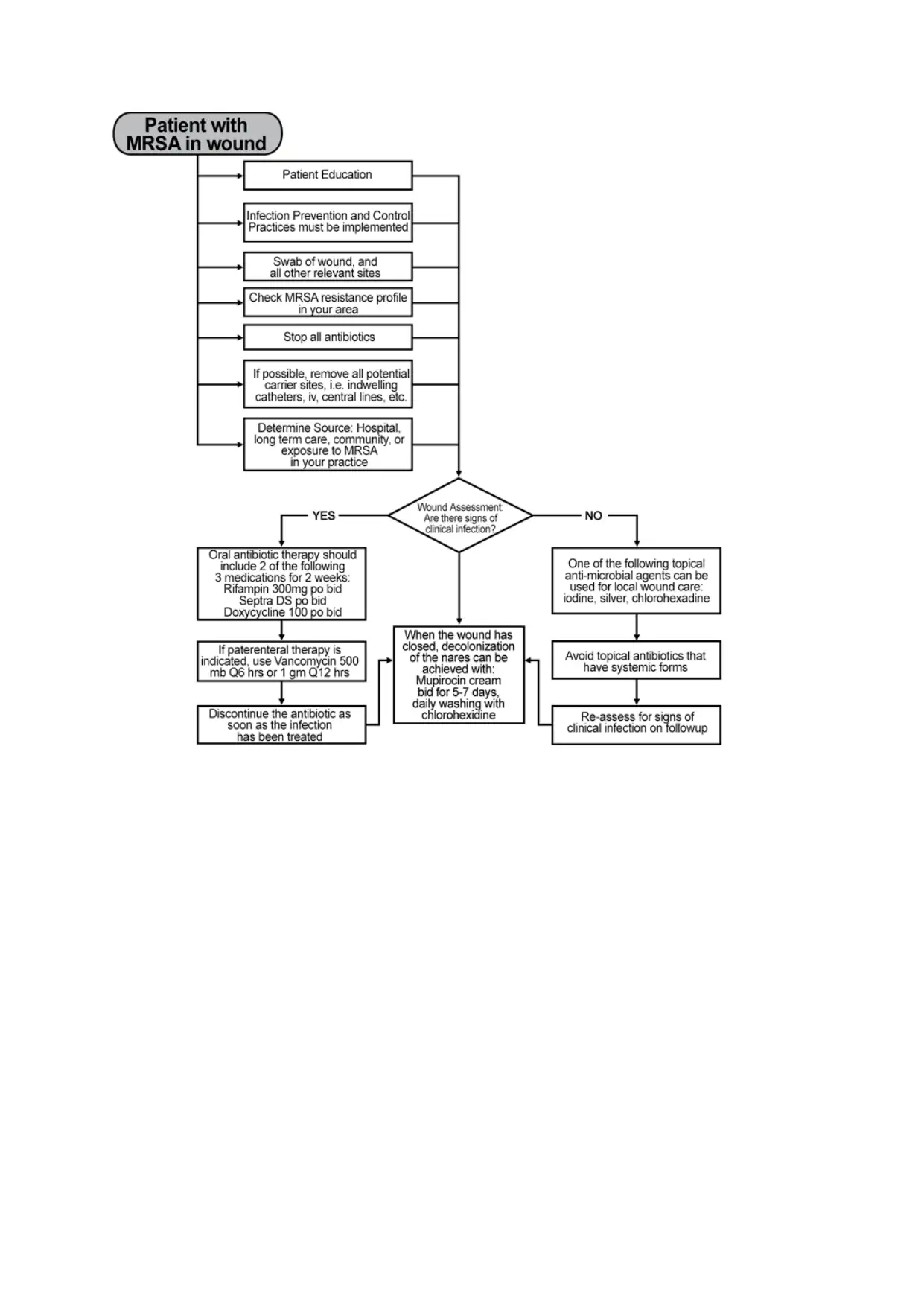

Appendix 1

biology, 18(1), 130.

Lee, A. S., de Lencastre, H., Garau, J., Kluytmans, J., Malhotra-Kumar, S.,

Peschel, A., & Harbarth, S. (2018). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Nature reviews Disease primers, 4, 18033.

Turner, N. A., Sharma-Kuinkel, B. K., Maskarinec, S. A., Eichenberger, E. M.,

Shah, P. P., Carugati, M., ... & Fowler, V. G. (2019). Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nature

Reviews Microbiology, 1.

Walrath, J. M., Immelt, S., Ray, E. M., van Graafeiland, B., & Himmelfarb, C.

D. (2015). Preparing patient safety advocates: Evaluation of nursing students’

reported experience with authority gradients in a hospital setting. Nurse

educator, 40(4), 174-178.

Werner, C., & Shaban, R. Z. (2018). Successfully clearing discharged patients

of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Opportunities for the prevention

and containment of antimicrobial resistance. Infection, disease & health, 23(1),

57-62.

Werner, C., Zimmerman, P. A., & Elder, E. (2016). Hospital based clearance of

patients with skin and soft tissue methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA): a systematic review of the literature. Infection, Disease & Health,

21(2), 72-83.

Appendix 1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.