Environmental Rebound Effects: Consumer Decisions and Economic Impact

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|32

|13268

|265

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on an MPRA paper, examines the environmental rebound effects stemming from consumer decisions to adopt 'green' consumption habits. It explores the potential for rebound effects to diminish the anticipated environmental benefits of actions such as reduced vehicle use, decreased electricity consumption, and the shift to more efficient vehicles and lighting. Using Australian data, the study finds that ignoring rebound effects can lead to overestimations of environmental benefits, particularly in cases involving more efficient technologies rather than simple conservation. The research highlights that lower-income households may exhibit higher rebound effects, suggesting the need for targeted environmental policies. The study also demonstrates the trade-off between economic and environmental advantages of 'green' choices and attributes the size of rebound effects to life-cycle analysis (LCA) methodologies. The report concludes by emphasizing that these results represent the minimum rebound effects to be considered in policy evaluation. The report is contributed by a student and is available on Desklib, a platform providing AI-based study tools.

MPRAMunich Personal RePEc Archive

What if consumers decided to all ‘go

green’ ? Environmental rebound effects

from consumption decisions

Cameron K. Murray

University of Queensland

July 2012

Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/40405/

MPRA Paper No.40405, posted 1.August 2012 01:09 UTC

What if consumers decided to all ‘go

green’ ? Environmental rebound effects

from consumption decisions

Cameron K. Murray

University of Queensland

July 2012

Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/40405/

MPRA Paper No.40405, posted 1.August 2012 01:09 UTC

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

What if consumers decided to all ‘go green’ ?

Environmental rebound effects from consumption decisions

Cameron K. Murray1,∗

University of Queensland,St Lucia, Queensland, Australia, 4067

Abstract

Shifting consumer preferences towards ‘green’consumption is promoted by many governments

and environmentalgroups.Rebound effects,which reduce the effectiveness ofsuch actions,are

estimated for cost-saving ‘green’ consumption choices using Australian data.

Cases examined are:reduced vehicle use,reduced electricity use,changing to smaller passenger

vehicles, and utilising fluorescent lighting.It is found that if rebound effects are ignored when eval-

uating ‘green’ consumption, environmental benefits will be overstated by around 20% for reduced

vehicle use,and 7% for reduced electricity use.Rebound effects are higher,and environmental

benefits lower,when more efficient vehicles or lighting are utilised rather than simple conserva-

tion actions offorgoing use.In addition,lower income households have higher rebound effects,

suggesting that environmentalpolicy directed at changing consumer behaviour is most effective

when targeted at high income households.Additionally,an inherent trade-off between economic

and environmental benefits of ‘green’ consumption choices is demonstrated.

The size of the rebound effect, and the observed variation with household income, is attributed to

life-cycle analysis (LCA) methodologies associated with the calculation of embodied GHG emis-

sions ofconsumption goods.These results should be therefore be interpreted as the minimum

rebound effect to include in policy evaluation.

Keywords: Rebound effect; conservation; household consumption; greenhouse emissions

∗Corresponding author

Email address:ckmurray@gmail.com (Cameron K. Murray )

1ph. +617 3255 2936, m.+61422 144 674

Preprint submitted to Elsevier July 31, 2012

Environmental rebound effects from consumption decisions

Cameron K. Murray1,∗

University of Queensland,St Lucia, Queensland, Australia, 4067

Abstract

Shifting consumer preferences towards ‘green’consumption is promoted by many governments

and environmentalgroups.Rebound effects,which reduce the effectiveness ofsuch actions,are

estimated for cost-saving ‘green’ consumption choices using Australian data.

Cases examined are:reduced vehicle use,reduced electricity use,changing to smaller passenger

vehicles, and utilising fluorescent lighting.It is found that if rebound effects are ignored when eval-

uating ‘green’ consumption, environmental benefits will be overstated by around 20% for reduced

vehicle use,and 7% for reduced electricity use.Rebound effects are higher,and environmental

benefits lower,when more efficient vehicles or lighting are utilised rather than simple conserva-

tion actions offorgoing use.In addition,lower income households have higher rebound effects,

suggesting that environmentalpolicy directed at changing consumer behaviour is most effective

when targeted at high income households.Additionally,an inherent trade-off between economic

and environmental benefits of ‘green’ consumption choices is demonstrated.

The size of the rebound effect, and the observed variation with household income, is attributed to

life-cycle analysis (LCA) methodologies associated with the calculation of embodied GHG emis-

sions ofconsumption goods.These results should be therefore be interpreted as the minimum

rebound effect to include in policy evaluation.

Keywords: Rebound effect; conservation; household consumption; greenhouse emissions

∗Corresponding author

Email address:ckmurray@gmail.com (Cameron K. Murray )

1ph. +617 3255 2936, m.+61422 144 674

Preprint submitted to Elsevier July 31, 2012

1. Background

More sustainable consumption patterns are promoted by governments, environmental groups and

internationalagencies as a measure to combat environmentaldegradation (UN,1992;OECD,

2002).Efforts to reduce resource consumption, including energy consumption and the associated

negative externality of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, through household consumption choices

are attractive due to the ability for win-win outcomes;where cost saving ‘green’behaviour si-

multaneously leads to environmentalbenefits.If consumer preferences can be nudged towards

less every and resource intensive consumption,through information and marketing campaigns,

then environmentalexternalities can be party corrected by being brought into consumer utility

functions.

Before promoting an agenda to nudge consumer preferences towards ‘green’consumption,the

scale of potential environmental benefits should be understood.It is commonly assumed that high

rates of adoption of win-win ‘green’ consumption choices will significantly reduce GHG emissions.

However,this assumption is typically made using incomplete engineering-type analysis,where

many little actions are expected to add up to significant economy wide changes.This type of

calculation ignores economic rebound effects.

Rebound effects describe the flow-on effects from technology and consumption pattern changes that

offset intended environmentalbenefits.In the context of cost-effective new technology,rebound

effects are generally classified as direct,indirect,or economy wide (Sorrelland Dimitropoulos,

2008).Direct effects (or price effects) occur when new technology decreases the effective price of a

good or service, and consumers adapt by consuming more of that good or service.Indirect effects

(or incomes effects) occur when reduced costs of a good or service lead to increased consumption of

other goods and services, which themselves have embodied GHG emissions.Finally the economy-

wide effect considers these two effects,plus changes to the scale and composition of production

economy-wide, including the emergence of new products and services.

One widely held view is that the indirect effect with respect to GHG emissions is smalldue

to energy inputs comprising a smallcomponent ofhousehold expenditure (Lovins et al.,1988;

Schipper and Grubb,2000). This view is gradually being eroded.Recent studies utilising life-

cycle assessment (LCA) of embodied GHG emissions show that the amount of energy consumed

indirectly by households is often higher than energy consumed directly through electricity,gas,

and motor fuel,and is a growing proportion (Vringer and Blok, 1995, 2000; Vringer et al., 2007;

Lenzen, 1998; Lenzen et al., 2004; Weber and Perrels, 2000; Reinders et al., 2003)

Few studies explicitly or implicitly estimate the magnitude of the indirect rebound effect (Chalkley

et al., 2001;Lenzen and Dey,2002;Alfredsson,2004;Brannlund et al.,2007;Mizobuchi,2008;

2

More sustainable consumption patterns are promoted by governments, environmental groups and

internationalagencies as a measure to combat environmentaldegradation (UN,1992;OECD,

2002).Efforts to reduce resource consumption, including energy consumption and the associated

negative externality of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, through household consumption choices

are attractive due to the ability for win-win outcomes;where cost saving ‘green’behaviour si-

multaneously leads to environmentalbenefits.If consumer preferences can be nudged towards

less every and resource intensive consumption,through information and marketing campaigns,

then environmentalexternalities can be party corrected by being brought into consumer utility

functions.

Before promoting an agenda to nudge consumer preferences towards ‘green’consumption,the

scale of potential environmental benefits should be understood.It is commonly assumed that high

rates of adoption of win-win ‘green’ consumption choices will significantly reduce GHG emissions.

However,this assumption is typically made using incomplete engineering-type analysis,where

many little actions are expected to add up to significant economy wide changes.This type of

calculation ignores economic rebound effects.

Rebound effects describe the flow-on effects from technology and consumption pattern changes that

offset intended environmentalbenefits.In the context of cost-effective new technology,rebound

effects are generally classified as direct,indirect,or economy wide (Sorrelland Dimitropoulos,

2008).Direct effects (or price effects) occur when new technology decreases the effective price of a

good or service, and consumers adapt by consuming more of that good or service.Indirect effects

(or incomes effects) occur when reduced costs of a good or service lead to increased consumption of

other goods and services, which themselves have embodied GHG emissions.Finally the economy-

wide effect considers these two effects,plus changes to the scale and composition of production

economy-wide, including the emergence of new products and services.

One widely held view is that the indirect effect with respect to GHG emissions is smalldue

to energy inputs comprising a smallcomponent ofhousehold expenditure (Lovins et al.,1988;

Schipper and Grubb,2000). This view is gradually being eroded.Recent studies utilising life-

cycle assessment (LCA) of embodied GHG emissions show that the amount of energy consumed

indirectly by households is often higher than energy consumed directly through electricity,gas,

and motor fuel,and is a growing proportion (Vringer and Blok, 1995, 2000; Vringer et al., 2007;

Lenzen, 1998; Lenzen et al., 2004; Weber and Perrels, 2000; Reinders et al., 2003)

Few studies explicitly or implicitly estimate the magnitude of the indirect rebound effect (Chalkley

et al., 2001;Lenzen and Dey,2002;Alfredsson,2004;Brannlund et al.,2007;Mizobuchi,2008;

2

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Druckman et al.,2011).Since the rebound effect is expressed in terms ofa particular resource

or externality,estimates ofthe indirect effect require an estimate ofthe embodied resources in

household consumption.The scarcity of embodied resource data is one reason for slim body of

research,a point emphasised in Kok et al.(2006) reviewed 19 studies ofembodied energy and

GHG emissions from consumption patterns,finding only three that provided sufficient detailto

allow econometric estimation of the indirect effect.Given the variation in the embodied energy

and GHG emissions due to different composition of national energy sources, one would expect the

some cross-country variation of indirect rebound effects.

The rebound effect literature is also heavily focused on improvements in energy-efficient technology

and centres on the possibility of an economy wide backfire, where rebound effects are larger than

engineering estimates ofenvironmentalbenefits (Saunders,2000;Inhaber,1997;Alcott, 2005;

Hanley et al., 2008).

The most promising area for demand-side environmental policies to have short-run pay-offs is not

new technology,but the adoption of ‘green’consumption choices in the absence of any changes

to technology.In this context, better targeted nudging of consumer preferences may improve the

environmentalpay-off of such policies.But a better understanding of nature of rebound effects,

and therefore the potential size of environmental benefits, is required to achieve this aim.

2. Rebound effects from pure consumption choices

This paper considers the scenario where technology and product choice are fixed,and only con-

sumer preferences change.In the absence of technology changes, cost-saving ‘green’ consumption

choices are subject to rebound effects when liberated purchasing power is utilised for additional

consumption.A household with new ‘green’ preferences choosing a smaller but more fuel-efficient

car may be tempted to drive further,and will spend the resulting cost savings elsewhere in the

household budget.

Specific definitions ofdirect and indirect rebound effects are required in the context ofpure

consumption choices with fixed technology.The direct effect is the offsetting environmental impact

that occurs when cost savings are spent on the commodity from which they are saved.For example,

changing to a fuelefficient smallcar will generate savings for the household from fuelexpenses,

but driving further willincur some offsetting fuelcosts. The indirect effect is the offsetting

environmental impact from the increased spending in other areas of the household budget.

In this paper,consumption choices that involve new household capital,such as new appliances

or vehicles, are referred to as because the household service, of lighting or transport, is produced

3

or externality,estimates ofthe indirect effect require an estimate ofthe embodied resources in

household consumption.The scarcity of embodied resource data is one reason for slim body of

research,a point emphasised in Kok et al.(2006) reviewed 19 studies ofembodied energy and

GHG emissions from consumption patterns,finding only three that provided sufficient detailto

allow econometric estimation of the indirect effect.Given the variation in the embodied energy

and GHG emissions due to different composition of national energy sources, one would expect the

some cross-country variation of indirect rebound effects.

The rebound effect literature is also heavily focused on improvements in energy-efficient technology

and centres on the possibility of an economy wide backfire, where rebound effects are larger than

engineering estimates ofenvironmentalbenefits (Saunders,2000;Inhaber,1997;Alcott, 2005;

Hanley et al., 2008).

The most promising area for demand-side environmental policies to have short-run pay-offs is not

new technology,but the adoption of ‘green’consumption choices in the absence of any changes

to technology.In this context, better targeted nudging of consumer preferences may improve the

environmentalpay-off of such policies.But a better understanding of nature of rebound effects,

and therefore the potential size of environmental benefits, is required to achieve this aim.

2. Rebound effects from pure consumption choices

This paper considers the scenario where technology and product choice are fixed,and only con-

sumer preferences change.In the absence of technology changes, cost-saving ‘green’ consumption

choices are subject to rebound effects when liberated purchasing power is utilised for additional

consumption.A household with new ‘green’ preferences choosing a smaller but more fuel-efficient

car may be tempted to drive further,and will spend the resulting cost savings elsewhere in the

household budget.

Specific definitions ofdirect and indirect rebound effects are required in the context ofpure

consumption choices with fixed technology.The direct effect is the offsetting environmental impact

that occurs when cost savings are spent on the commodity from which they are saved.For example,

changing to a fuelefficient smallcar will generate savings for the household from fuelexpenses,

but driving further willincur some offsetting fuelcosts. The indirect effect is the offsetting

environmental impact from the increased spending in other areas of the household budget.

In this paper,consumption choices that involve new household capital,such as new appliances

or vehicles, are referred to as because the household service, of lighting or transport, is produced

3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

more cheaply (ignoring any reductions in quality).In these scenarios one would expect both direct

and indirect effects.

A household that goes ‘green’ without changing its capital stock, but instead chooses a conservation

approach, such as replacing driving with cycling or utilising electrical appliances more sparingly,

the indirect rebound effect will be the total rebound effect.These scenarios are pure conservation

choices.Distinguishing between the two types of behaviour provides a clearer picture of net effect

of household choices,at least in the short run,and the types of consumption choices that have

better associated environmental benefits.

Existing estimates ofrebound effects from consumption choices alone are limited.Alfredsson

(2004) estimates rebound effects from ‘green’ consumption choices of 14% for transport abatement,

and 20% for ‘green housing, and a back-fire (approximately 200%) for a ‘green diet and a rebound

effect for these combined actions of20% in terms ofGHG emissions.Additionally,the impact

of increasing incomes was shown to offset any benefits made by consumption pattern changes.

Specifically,exogenous income growth of 1% per year offsets allbut 7% of the decrease in GHG

emissions from the combination of changes by 2020,while income growth of 2% willmore than

compensate for consumption pattern changes,and lead to a 13% increase in GHG emissions by

2020.

Lenzen and Dey (2002) account for the rebound effect from a change to a cheaper low carbon diet,

with estimates around 50%.Druckman et al. (2011) estimate the direct and indirect rebound effect

for three abatement actionshousehold energy reduction,more efficient food consumption (less

throw-away food), and reduced vehicle travelwith results showing a 7%, 59% and 22% rebound

effects respectively in terms of GHG emissions.

One common feature of these studies is that the rebound effect model allows for re-spending on the

goods from which the saving where made,meaning in allscenarios have a direct rebound effect.

For example,Alfredsson (2004),Lenzen and Dey (2002) and Druckman et al. (2011) use models

where households who adopt a green diet then proceed to spend a portion of the cost savings on

the previous diet.Whether this has a materialimpact on the estimates is uncertain,but it is

one area where this paper improves the estimation of rebound effects, and enables differentiation

between pure conservation choices and efficient consumption choices.

Of particular interest is the potentialfor variation in the magnitude ofthe rebound effect for

consumption choices across the different household incomes.One might expect that since there is

a trade-off between direct and indirect effects,and direct effects have been observed to diminish

with rising incomes that indirect rebound effects may increase with rising income levels (Baker

et al., 1989; Milne and Boardman, 2000; Roy, 2000).Yet LCA data of embodied GHG emissions

4

and indirect effects.

A household that goes ‘green’ without changing its capital stock, but instead chooses a conservation

approach, such as replacing driving with cycling or utilising electrical appliances more sparingly,

the indirect rebound effect will be the total rebound effect.These scenarios are pure conservation

choices.Distinguishing between the two types of behaviour provides a clearer picture of net effect

of household choices,at least in the short run,and the types of consumption choices that have

better associated environmental benefits.

Existing estimates ofrebound effects from consumption choices alone are limited.Alfredsson

(2004) estimates rebound effects from ‘green’ consumption choices of 14% for transport abatement,

and 20% for ‘green housing, and a back-fire (approximately 200%) for a ‘green diet and a rebound

effect for these combined actions of20% in terms ofGHG emissions.Additionally,the impact

of increasing incomes was shown to offset any benefits made by consumption pattern changes.

Specifically,exogenous income growth of 1% per year offsets allbut 7% of the decrease in GHG

emissions from the combination of changes by 2020,while income growth of 2% willmore than

compensate for consumption pattern changes,and lead to a 13% increase in GHG emissions by

2020.

Lenzen and Dey (2002) account for the rebound effect from a change to a cheaper low carbon diet,

with estimates around 50%.Druckman et al. (2011) estimate the direct and indirect rebound effect

for three abatement actionshousehold energy reduction,more efficient food consumption (less

throw-away food), and reduced vehicle travelwith results showing a 7%, 59% and 22% rebound

effects respectively in terms of GHG emissions.

One common feature of these studies is that the rebound effect model allows for re-spending on the

goods from which the saving where made,meaning in allscenarios have a direct rebound effect.

For example,Alfredsson (2004),Lenzen and Dey (2002) and Druckman et al. (2011) use models

where households who adopt a green diet then proceed to spend a portion of the cost savings on

the previous diet.Whether this has a materialimpact on the estimates is uncertain,but it is

one area where this paper improves the estimation of rebound effects, and enables differentiation

between pure conservation choices and efficient consumption choices.

Of particular interest is the potentialfor variation in the magnitude ofthe rebound effect for

consumption choices across the different household incomes.One might expect that since there is

a trade-off between direct and indirect effects,and direct effects have been observed to diminish

with rising incomes that indirect rebound effects may increase with rising income levels (Baker

et al., 1989; Milne and Boardman, 2000; Roy, 2000).Yet LCA data of embodied GHG emissions

4

suggests that the opposite might be true due to the decrease in GHG intensity of luxury goods

(Lenzen et al., 2004, 2006; Hertwich, 2005).

Existing studies ofhousehold energy use suggest that rebound effects may be much higher in

households,and in countries,with low incomes,due to energy fuels comprising a larger share of

the household budget (Baker et al.,1989;Milne and Boardman,2000;Roy, 2000;Hong et al.,

2006).This evidence points to indirect effects becoming more significant than direct effects over

time and with increasing incomes.

Girod and De Haan (2010) suggest that evaluation of GHG emissions from consumption may over-

state emissions at high income levels due to increasing quality.The basic argument is that twice

the expenditure on a product does does purchase twice to physicalquantity.Yet these elevated

prices are either reflective ofincreased inputs to production,or some form ofrent transferred

to the producer,meaning that this assertion remains unclear at a macro levelVringer and Blok

(1995).

Indeed,as a backdrop to this literature,there remains a major concern about the limitations

of LCA data due to necessary boundary specifications ofinputs and outputs ofthe economy.

Variation in GHG intensity of consumption goods ultimately determines the size of the rebound

effect and the net environmentalbenefit ofconsumption choices.Typically LCA data shows a

trade-off between labour and energy intensity (Maddala,1965;Karunaratne,1981;Lenzen and

Dey, 2002),yet the supply oflabour into the production process requires the consumption of

other commodities.

To overcome these truncation errors, with the assumption that labour input is merely a transfer,

Costanza (1980) estimated the embodied energy of a number of economic outputs with alternative

system boundaries.This method greatly reduced variation in energy intensity across outputs,

leading to the observation that ”there is a strong relationship between embodied energy and

dollar value”.Within Costanza’s (1980) framework, consumption pattern changes would provide

no net changes to energy consumption or GHG emissions.Indeed,the only way for household

to reduce their GHG emissions would be to reduce their income at the same time as reducing

expenditure through conservation behaviour, as suggested by Madlener and Alcott (2009).

With this in mind, this paper builds on these handful of studies of rebound effects from consump-

tion choices.In particular,pure conservation choices by households are modelled with indirect

effects only,and the sensitivity of the scale of the rebound effect to household incomes is exam-

ined. The differential benefits of ‘green’ consumption across the income range may provide clues

to better targeted policy,particularly in light of the relative attractiveness of cost-saving ‘green’

choices for low income households.Indeed,any difference in effectiveness between efficiency and

5

(Lenzen et al., 2004, 2006; Hertwich, 2005).

Existing studies ofhousehold energy use suggest that rebound effects may be much higher in

households,and in countries,with low incomes,due to energy fuels comprising a larger share of

the household budget (Baker et al.,1989;Milne and Boardman,2000;Roy, 2000;Hong et al.,

2006).This evidence points to indirect effects becoming more significant than direct effects over

time and with increasing incomes.

Girod and De Haan (2010) suggest that evaluation of GHG emissions from consumption may over-

state emissions at high income levels due to increasing quality.The basic argument is that twice

the expenditure on a product does does purchase twice to physicalquantity.Yet these elevated

prices are either reflective ofincreased inputs to production,or some form ofrent transferred

to the producer,meaning that this assertion remains unclear at a macro levelVringer and Blok

(1995).

Indeed,as a backdrop to this literature,there remains a major concern about the limitations

of LCA data due to necessary boundary specifications ofinputs and outputs ofthe economy.

Variation in GHG intensity of consumption goods ultimately determines the size of the rebound

effect and the net environmentalbenefit ofconsumption choices.Typically LCA data shows a

trade-off between labour and energy intensity (Maddala,1965;Karunaratne,1981;Lenzen and

Dey, 2002),yet the supply oflabour into the production process requires the consumption of

other commodities.

To overcome these truncation errors, with the assumption that labour input is merely a transfer,

Costanza (1980) estimated the embodied energy of a number of economic outputs with alternative

system boundaries.This method greatly reduced variation in energy intensity across outputs,

leading to the observation that ”there is a strong relationship between embodied energy and

dollar value”.Within Costanza’s (1980) framework, consumption pattern changes would provide

no net changes to energy consumption or GHG emissions.Indeed,the only way for household

to reduce their GHG emissions would be to reduce their income at the same time as reducing

expenditure through conservation behaviour, as suggested by Madlener and Alcott (2009).

With this in mind, this paper builds on these handful of studies of rebound effects from consump-

tion choices.In particular,pure conservation choices by households are modelled with indirect

effects only,and the sensitivity of the scale of the rebound effect to household incomes is exam-

ined. The differential benefits of ‘green’ consumption across the income range may provide clues

to better targeted policy,particularly in light of the relative attractiveness of cost-saving ‘green’

choices for low income households.Indeed,any difference in effectiveness between efficiency and

5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

conservation behaviour,and the additive effects ofmultiple ‘green’choices,are also important

policy considerations.

3. Methodology

Rebound effects are generally expressed as the amount ofenergy,resources or externality,gen-

erated by offsetting consumption,as a percentage ofpotentialreductions where not offsetting

consumption occurs (Berkhout et al.,2000). Measuring this baseline potentialreduction is a

critical factor in determining the scale of the rebound effect.

For example,an engineering estimate that converts per unit ofservice reductions in electricity

consumption of a more efficient appliance to kWh, then converts that into GHG emissions based

on transmission loss, electricity generation efficiency and the emissions per unit of coal combusted,

is flawed.(Lovins et al.,1988;Weizacker et al.,1998) The totalembodied energy in the more

efficient appliance (replacement capital) should be subtracted from the potential energy reductions

to determine the baseline,as this embodied resource consumption is necessary and inseparable

from the new appliance itself.This contrasts the position ofSorrelland Dimitropoulos (2008)

who propose that the embodied resource requirements of replacement capital comprise part of the

rebound effect.In this paper, the baseline potential reduction of GHG emissions is calculated as

the cost saving multiplied by the GHG intensity of that expenditure.Offsetting GHG emissions

are those embodied in the consumption of goods enabled by the cost savings.

3.1. Data

The 2003-4 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Household Expenditure Survey (HES) of 6,957

households aggregated into 36 commodity groups is used in this paper (ABS,2004).The corre-

sponding embodied GHG emissions for each commodity group, calculated using an input-output

based hybrid method, was made available from the Centre for Integrated Sustainability Analysis,

Sydney (Dey, 2008) (Appendix A).

Matching the two data sets shows decreasing emissions intensity with household income level,

but increasing quantity of emissions.No evidence of an environmentalKuznets curve for GHG

emissions is observed, which corresponds with the macroeconomic relationship between energy, or

greenhouse emissions,and gross domestic product typically seen in household emissions studies

(Holtz-Eakin and Selden, 1995; Schipper and Grubb, 2000; Greening, 2001; Lenzen et al., 2004).

3.2. Household demand models

The rebound effect model is based on a system of household demand equations where expenditure

on each commodity is dependent on total expenditure as a proxy for the household income level, as

6

policy considerations.

3. Methodology

Rebound effects are generally expressed as the amount ofenergy,resources or externality,gen-

erated by offsetting consumption,as a percentage ofpotentialreductions where not offsetting

consumption occurs (Berkhout et al.,2000). Measuring this baseline potentialreduction is a

critical factor in determining the scale of the rebound effect.

For example,an engineering estimate that converts per unit ofservice reductions in electricity

consumption of a more efficient appliance to kWh, then converts that into GHG emissions based

on transmission loss, electricity generation efficiency and the emissions per unit of coal combusted,

is flawed.(Lovins et al.,1988;Weizacker et al.,1998) The totalembodied energy in the more

efficient appliance (replacement capital) should be subtracted from the potential energy reductions

to determine the baseline,as this embodied resource consumption is necessary and inseparable

from the new appliance itself.This contrasts the position ofSorrelland Dimitropoulos (2008)

who propose that the embodied resource requirements of replacement capital comprise part of the

rebound effect.In this paper, the baseline potential reduction of GHG emissions is calculated as

the cost saving multiplied by the GHG intensity of that expenditure.Offsetting GHG emissions

are those embodied in the consumption of goods enabled by the cost savings.

3.1. Data

The 2003-4 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Household Expenditure Survey (HES) of 6,957

households aggregated into 36 commodity groups is used in this paper (ABS,2004).The corre-

sponding embodied GHG emissions for each commodity group, calculated using an input-output

based hybrid method, was made available from the Centre for Integrated Sustainability Analysis,

Sydney (Dey, 2008) (Appendix A).

Matching the two data sets shows decreasing emissions intensity with household income level,

but increasing quantity of emissions.No evidence of an environmentalKuznets curve for GHG

emissions is observed, which corresponds with the macroeconomic relationship between energy, or

greenhouse emissions,and gross domestic product typically seen in household emissions studies

(Holtz-Eakin and Selden, 1995; Schipper and Grubb, 2000; Greening, 2001; Lenzen et al., 2004).

3.2. Household demand models

The rebound effect model is based on a system of household demand equations where expenditure

on each commodity is dependent on total expenditure as a proxy for the household income level, as

6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

is common in household demand studies (Deaton and Muellbauer, 1980; Haque, 2005; Brannlund

et al., 2007).Housing expenditure is excluded from data, as is expenditure on tobacco and health

services, which are not expected to be susceptible to the incorporation of environmental damage

into the utility function.Additionally,savings rates are assumed to be constant (saving reduced

costs would lead to greater future consumption in any case).

Selection ofa functionalform of the household demand system requires the ability to assess

the potentialvariation in the rebound effect at different income levels,and as such,the system

should allow for the possibility of threshold or saturation levels,where goods become inferior at

particular income levels.For completeness,four different household demand models are used to

generate parameters that feed into the estimation of the rebound effect;

1. a basic double semi-log (DSL) specification,

2. a DSL specification with non-income explanatory variables (DSL2),

3. the Working-Leser (WL) model of budget shares, and

4. a linear model.

Utilising this array of common functional forms also sheds some light on the sensitivity of estimates

to the statistical methods applied, which may be an important practical consideration for policy

assessment.The basic DSL is of the form

qi = αi + βi Y + γi ln Y (1)

where qi is the expenditure in on each of the 36 i commodities, and Y is total expenditure.The

extended DSL model in Equation 2 includes non-income explanatory variables;age of household

reference person, A, number of persons in the household, N , state, S, degree of urbanity, U , and

dwelling type,D, each ofwhich have been previously shown to have an impact on household

emissions (Lenzen et al.2004; Vringer et al.2007).

qi = αi + βi Y + γi ln Y + θ1i N + θ2i U + θ3i S + θ4i A + θ5i D (2)

The WL model relates budget shares, rather than expenditure, linearly with the logarithm of total

expenditure.The budget share, w, of each i commodity is calculated by

wi = qi

Y (3)

then the relationship

7

et al., 2007).Housing expenditure is excluded from data, as is expenditure on tobacco and health

services, which are not expected to be susceptible to the incorporation of environmental damage

into the utility function.Additionally,savings rates are assumed to be constant (saving reduced

costs would lead to greater future consumption in any case).

Selection ofa functionalform of the household demand system requires the ability to assess

the potentialvariation in the rebound effect at different income levels,and as such,the system

should allow for the possibility of threshold or saturation levels,where goods become inferior at

particular income levels.For completeness,four different household demand models are used to

generate parameters that feed into the estimation of the rebound effect;

1. a basic double semi-log (DSL) specification,

2. a DSL specification with non-income explanatory variables (DSL2),

3. the Working-Leser (WL) model of budget shares, and

4. a linear model.

Utilising this array of common functional forms also sheds some light on the sensitivity of estimates

to the statistical methods applied, which may be an important practical consideration for policy

assessment.The basic DSL is of the form

qi = αi + βi Y + γi ln Y (1)

where qi is the expenditure in on each of the 36 i commodities, and Y is total expenditure.The

extended DSL model in Equation 2 includes non-income explanatory variables;age of household

reference person, A, number of persons in the household, N , state, S, degree of urbanity, U , and

dwelling type,D, each ofwhich have been previously shown to have an impact on household

emissions (Lenzen et al.2004; Vringer et al.2007).

qi = αi + βi Y + γi ln Y + θ1i N + θ2i U + θ3i S + θ4i A + θ5i D (2)

The WL model relates budget shares, rather than expenditure, linearly with the logarithm of total

expenditure.The budget share, w, of each i commodity is calculated by

wi = qi

Y (3)

then the relationship

7

wi = αi + βi ln Y (4)

is estimated.The functional from of the Engel curve from the WL model is then determined by

substituting equation (3) into (4) to get

qi = αi Y + βi Y ln Y (5)

Appendices B through E provide results of these model regressions.In both DSL models, Whites

heteroskedasticity consistent method of calculating standard errors and covariance is used, while

for the linear and WL model, ordinary least squares is used with no further statistical adjustment.

It is important to note that total expenditure is a significant variable for every commodity group.

This validates to some degree the income determinism assumption underpinning these models.

The significance levels observed for the non-income explanatory variables in the extended DSL2

modelalso provide evidence that these household characteristics are important determinants of

expenditure choices.In the domestic fuel and power and vehicle fuel commodity groups, the most

GHG intensive expenditure groups,almost allof the non-income variables are significant.Most

other results follow intuitive logic.

3.3. Rebound effect model

The marginalbudget share (MBS),or the amount ofextra expenditure on commodity i for an

increase in totalexpenditure of one dollar,is utilised in the rebound estimation modelbased on

estimated coefficients from the household demand model.For each of the functionalforms used

in this study, the MBS for each i commodity is as follows:

DSL MBS i = βi + γi

Y

Linear MBS i = βi

WL MBS i = αi + β log Y + βi

Two alternative models are used for estimating the rebound effect.The first applies to efficient

consumption choices,an efficiency model,where although technology is fixed there are cheaper

energy efficient alternatives currently available for providing similar household services.Given that

technology is unchanged, there is a sacrifice in the quality of service, such as passenger kilometres,

that accompanies the reduction in price.In such cases,the direct effect,caused by the income

effect but excluding the substitution effect, will be considered.New ’green’ consumer preferences

cause the change in household capital, so estimating prices effects based on the ’ungreen’ sample,

and ignoring quality changes, would be misleading to some extent.

8

is estimated.The functional from of the Engel curve from the WL model is then determined by

substituting equation (3) into (4) to get

qi = αi Y + βi Y ln Y (5)

Appendices B through E provide results of these model regressions.In both DSL models, Whites

heteroskedasticity consistent method of calculating standard errors and covariance is used, while

for the linear and WL model, ordinary least squares is used with no further statistical adjustment.

It is important to note that total expenditure is a significant variable for every commodity group.

This validates to some degree the income determinism assumption underpinning these models.

The significance levels observed for the non-income explanatory variables in the extended DSL2

modelalso provide evidence that these household characteristics are important determinants of

expenditure choices.In the domestic fuel and power and vehicle fuel commodity groups, the most

GHG intensive expenditure groups,almost allof the non-income variables are significant.Most

other results follow intuitive logic.

3.3. Rebound effect model

The marginalbudget share (MBS),or the amount ofextra expenditure on commodity i for an

increase in totalexpenditure of one dollar,is utilised in the rebound estimation modelbased on

estimated coefficients from the household demand model.For each of the functionalforms used

in this study, the MBS for each i commodity is as follows:

DSL MBS i = βi + γi

Y

Linear MBS i = βi

WL MBS i = αi + β log Y + βi

Two alternative models are used for estimating the rebound effect.The first applies to efficient

consumption choices,an efficiency model,where although technology is fixed there are cheaper

energy efficient alternatives currently available for providing similar household services.Given that

technology is unchanged, there is a sacrifice in the quality of service, such as passenger kilometres,

that accompanies the reduction in price.In such cases,the direct effect,caused by the income

effect but excluding the substitution effect, will be considered.New ’green’ consumer preferences

cause the change in household capital, so estimating prices effects based on the ’ungreen’ sample,

and ignoring quality changes, would be misleading to some extent.

8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The second applies to conservation choices, a conservation model, which only allows increases in

expenditure on the goods or services from which cost savings were not made.For example,an

individual who chooses to cycle instead of drive is unlikely to use any cost savings to drive further.

And even ifthey did,it would simply be a reduction in the conservation measure,and not a

rebound effect.Existing studies typically do not controlfor this in their models,meaning that

unlikely behaviour such as cost savings from electricity conservation being spent on more electricity

is a common outcome (Alfredsson, 2004; Brannlund et al., 2007; Druckman et al., 2011).

Denoting cost savings from ‘green’consumption choices X,then for commodity s from which

savings are made, the new expenditure in the efficiency model is

Qsnew = Qsold − X + X.MBS s (6)

while for all other for other i commodities in the household budget the new expenditure, Qi new , is

Qi new = Qi old + X.MBS i . (7)

In the conservation model the new expenditure on the conserved commodity is

Qsnew = Qsold − X (8)

while for allother i commodities the new expenditure levelensures Walras’Law by reallocating

the expected M BSs across all other commodities.

Qi new = Qi old + X.MBS i +

∞X

n=1

X.MBS n

s .MBS i . (9)

To estimate the change in GHG emissions from the change in consumption patterns,the expen-

diture in each commodity group is multiplied by the GHG intensity ofthat commodity.Since

there are no technology changes applicable to production stages of the economy, the same embod-

ied emissions data can be used in both the before and after scenario without concerns regarding

changing production patterns in the economy.

In the resource generic form of Lenzen and Dey (2002),if the overallembodiment of resource f

(in this case GHG emission),for commodity i,is Rf,i , then the totalembodiment off for all

consumption is

f = X Qi Rf,i (10)

9

expenditure on the goods or services from which cost savings were not made.For example,an

individual who chooses to cycle instead of drive is unlikely to use any cost savings to drive further.

And even ifthey did,it would simply be a reduction in the conservation measure,and not a

rebound effect.Existing studies typically do not controlfor this in their models,meaning that

unlikely behaviour such as cost savings from electricity conservation being spent on more electricity

is a common outcome (Alfredsson, 2004; Brannlund et al., 2007; Druckman et al., 2011).

Denoting cost savings from ‘green’consumption choices X,then for commodity s from which

savings are made, the new expenditure in the efficiency model is

Qsnew = Qsold − X + X.MBS s (6)

while for all other for other i commodities in the household budget the new expenditure, Qi new , is

Qi new = Qi old + X.MBS i . (7)

In the conservation model the new expenditure on the conserved commodity is

Qsnew = Qsold − X (8)

while for allother i commodities the new expenditure levelensures Walras’Law by reallocating

the expected M BSs across all other commodities.

Qi new = Qi old + X.MBS i +

∞X

n=1

X.MBS n

s .MBS i . (9)

To estimate the change in GHG emissions from the change in consumption patterns,the expen-

diture in each commodity group is multiplied by the GHG intensity ofthat commodity.Since

there are no technology changes applicable to production stages of the economy, the same embod-

ied emissions data can be used in both the before and after scenario without concerns regarding

changing production patterns in the economy.

In the resource generic form of Lenzen and Dey (2002),if the overallembodiment of resource f

(in this case GHG emission),for commodity i,is Rf,i , then the totalembodiment off for all

consumption is

f = X Qi Rf,i (10)

9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The potentialresource savings,or the denominator ofthe rebound effect,are calculated as X

multiplied by the embodied factor Rf for commodity s.The rebound effect for resource f can

then be expressed as a percentage of the potential resource savings, as

RE = (X.R f,s ) − (

P Qi old Rf,i − P Qi new .Rf,i )

X.R f,s

(11)

which simplifies to

RE = 1 −

P Qi old Rf,i − P Qi new .Rf,i

X.R f,s

(12)

Conservation and efficiency model are generated by using the two alternative Qnew calculations.

Further, each model is estimated using the four functional forms of the household demand system.

Importantly,in this modelthe rebound effect is a function ofthe totalexpenditure level(as a

proxy for income) and it is expected that a degree of variation will be observed across the income

range.

3.4. Cases

3.4.1. Vehicle fuel

Driving less,or choosing a smaller fuelefficient vehicle,are widely promoted choices households

can make to reduce GHG emissions (Foundation,2007;Government,2007). Both vehicle fuel

cases (conservation and efficiency) have been developed to represent the same baseline reductions

in fuel use and GHG emissions.

To ensure feasibility at all income levels, the efficiency case allows for the replacement of passenger

vehicles (household capital) with no change in capital cost.Evidence suggests that replacing the

average Australian passenger vehicle on the second hand market with one that uses 4L/100Kms

less fuelis possible without increased capitalcosts,by sacrificing size and quality (:20,2008;

of Consumer and Protection, 2008).Other input includes include the average number of kilometres

driven by Australian household per year,at approximately 13,900kms in 2003-04,and the price

of fuel at $0.90 per litre (ABS, 2006; of Consumer and Protection, 2008).

Further to the savings on motor fuelitself,there are cost savings on complementary goods such

as vehicle registration,tyres and servicing.The registration cost difference between a four and

six cylinder car (the most likely vehicle substitute) in Queensland is $111.95 (Transport,2008).

A saving of $50 has been assumed for the reduction in associated servicing and running costs per

year. Combining these figures to construct the cost savings for the efficiency case is shown in

Table 1.

10

multiplied by the embodied factor Rf for commodity s.The rebound effect for resource f can

then be expressed as a percentage of the potential resource savings, as

RE = (X.R f,s ) − (

P Qi old Rf,i − P Qi new .Rf,i )

X.R f,s

(11)

which simplifies to

RE = 1 −

P Qi old Rf,i − P Qi new .Rf,i

X.R f,s

(12)

Conservation and efficiency model are generated by using the two alternative Qnew calculations.

Further, each model is estimated using the four functional forms of the household demand system.

Importantly,in this modelthe rebound effect is a function ofthe totalexpenditure level(as a

proxy for income) and it is expected that a degree of variation will be observed across the income

range.

3.4. Cases

3.4.1. Vehicle fuel

Driving less,or choosing a smaller fuelefficient vehicle,are widely promoted choices households

can make to reduce GHG emissions (Foundation,2007;Government,2007). Both vehicle fuel

cases (conservation and efficiency) have been developed to represent the same baseline reductions

in fuel use and GHG emissions.

To ensure feasibility at all income levels, the efficiency case allows for the replacement of passenger

vehicles (household capital) with no change in capital cost.Evidence suggests that replacing the

average Australian passenger vehicle on the second hand market with one that uses 4L/100Kms

less fuelis possible without increased capitalcosts,by sacrificing size and quality (:20,2008;

of Consumer and Protection, 2008).Other input includes include the average number of kilometres

driven by Australian household per year,at approximately 13,900kms in 2003-04,and the price

of fuel at $0.90 per litre (ABS, 2006; of Consumer and Protection, 2008).

Further to the savings on motor fuelitself,there are cost savings on complementary goods such

as vehicle registration,tyres and servicing.The registration cost difference between a four and

six cylinder car (the most likely vehicle substitute) in Queensland is $111.95 (Transport,2008).

A saving of $50 has been assumed for the reduction in associated servicing and running costs per

year. Combining these figures to construct the cost savings for the efficiency case is shown in

Table 1.

10

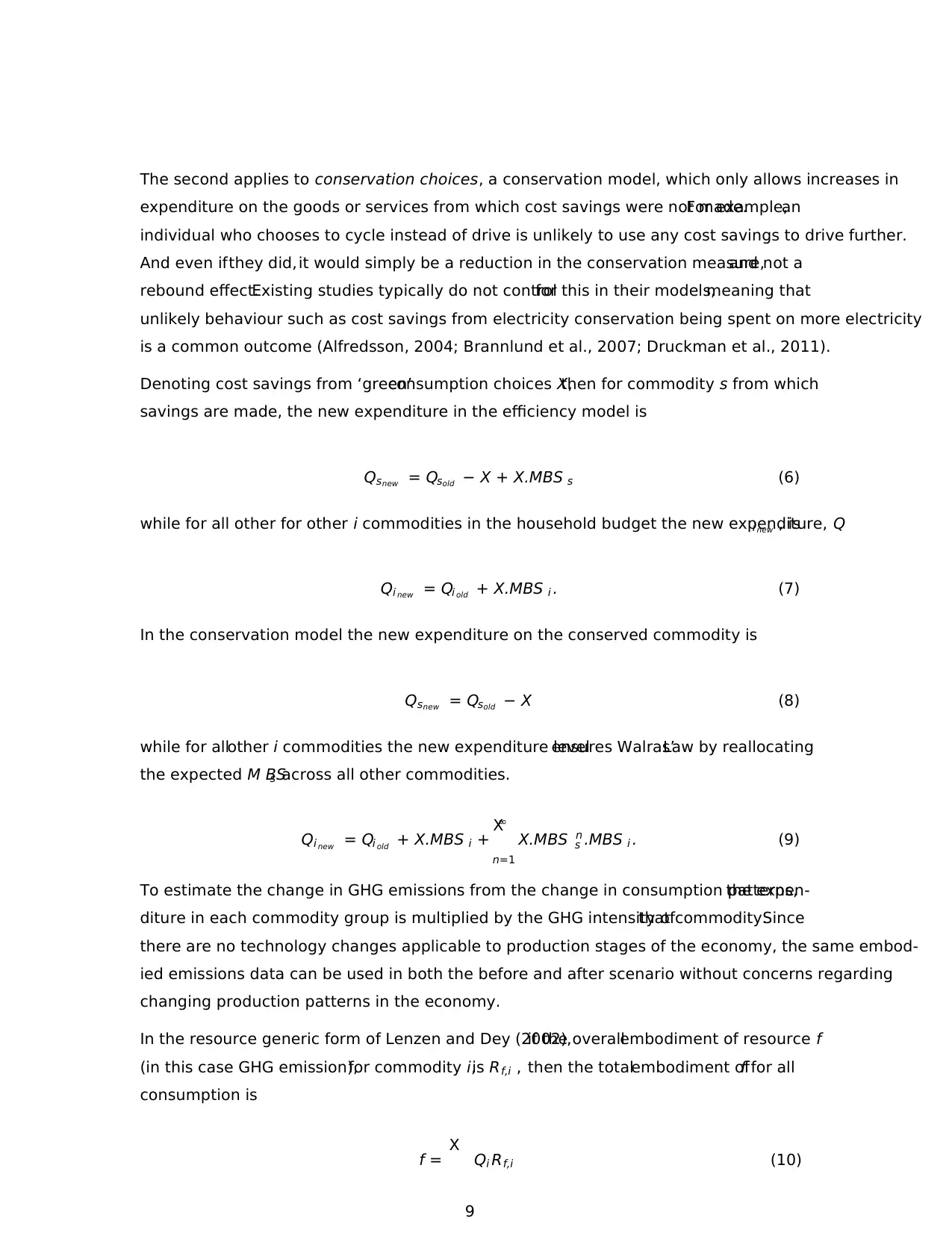

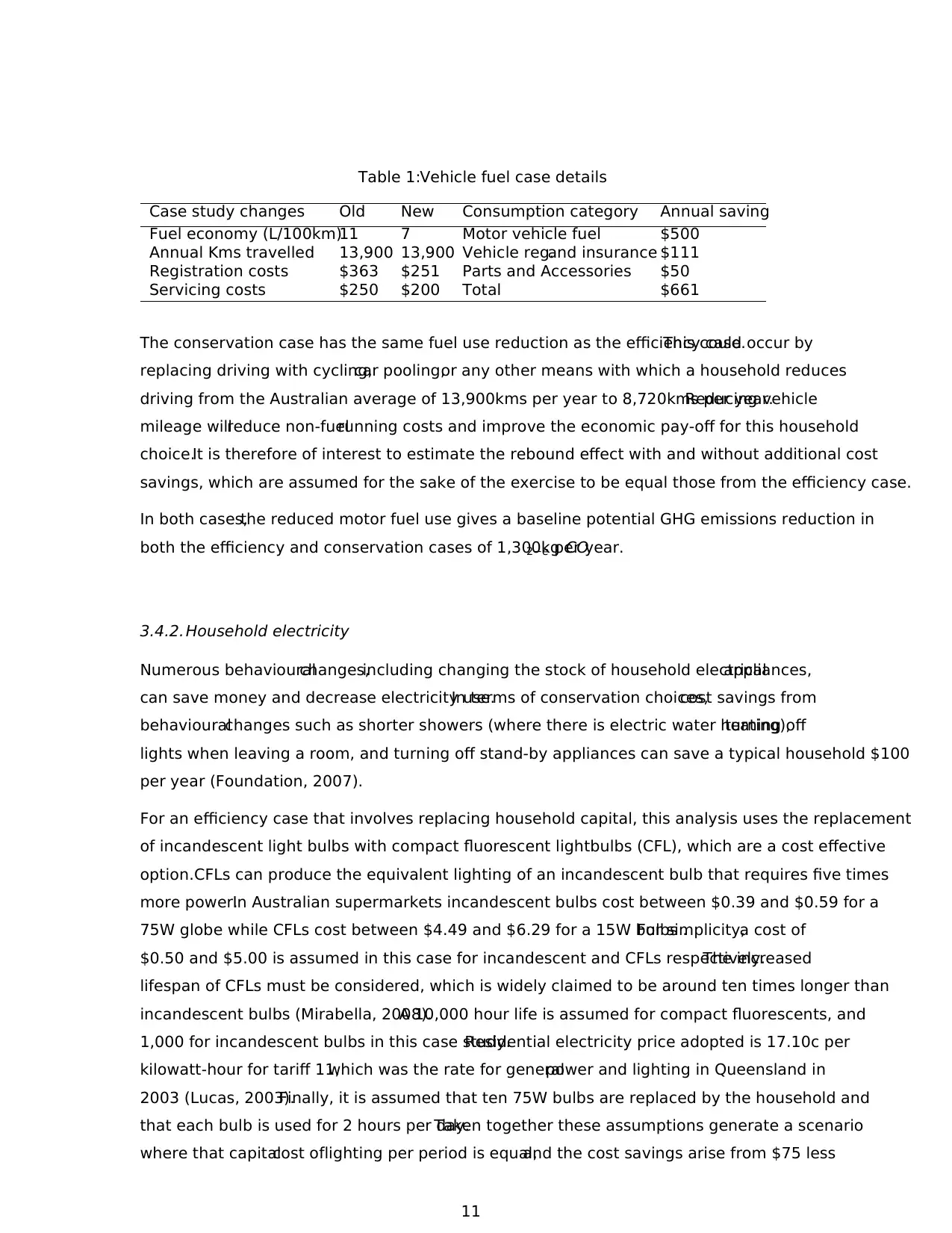

Table 1:Vehicle fuel case details

Case study changes Old New Consumption category Annual saving

Fuel economy (L/100km)11 7 Motor vehicle fuel $500

Annual Kms travelled 13,900 13,900 Vehicle reg.and insurance $111

Registration costs $363 $251 Parts and Accessories $50

Servicing costs $250 $200 Total $661

The conservation case has the same fuel use reduction as the efficiency case.This could occur by

replacing driving with cycling,car pooling,or any other means with which a household reduces

driving from the Australian average of 13,900kms per year to 8,720kms per year.Reducing vehicle

mileage willreduce non-fuelrunning costs and improve the economic pay-off for this household

choice.It is therefore of interest to estimate the rebound effect with and without additional cost

savings, which are assumed for the sake of the exercise to be equal those from the efficiency case.

In both cases,the reduced motor fuel use gives a baseline potential GHG emissions reduction in

both the efficiency and conservation cases of 1,300kg CO2−e per year.

3.4.2. Household electricity

Numerous behaviouralchanges,including changing the stock of household electricalappliances,

can save money and decrease electricity use.In terms of conservation choices,cost savings from

behaviouralchanges such as shorter showers (where there is electric water heating),turning off

lights when leaving a room, and turning off stand-by appliances can save a typical household $100

per year (Foundation, 2007).

For an efficiency case that involves replacing household capital, this analysis uses the replacement

of incandescent light bulbs with compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFL), which are a cost effective

option.CFLs can produce the equivalent lighting of an incandescent bulb that requires five times

more power.In Australian supermarkets incandescent bulbs cost between $0.39 and $0.59 for a

75W globe while CFLs cost between $4.49 and $6.29 for a 15W bulbs .For simplicity,a cost of

$0.50 and $5.00 is assumed in this case for incandescent and CFLs respectively.The increased

lifespan of CFLs must be considered, which is widely claimed to be around ten times longer than

incandescent bulbs (Mirabella, 2008).A 10,000 hour life is assumed for compact fluorescents, and

1,000 for incandescent bulbs in this case study.Residential electricity price adopted is 17.10c per

kilowatt-hour for tariff 11,which was the rate for generalpower and lighting in Queensland in

2003 (Lucas, 2003).Finally, it is assumed that ten 75W bulbs are replaced by the household and

that each bulb is used for 2 hours per day.Taken together these assumptions generate a scenario

where that capitalcost oflighting per period is equal,and the cost savings arise from $75 less

11

Case study changes Old New Consumption category Annual saving

Fuel economy (L/100km)11 7 Motor vehicle fuel $500

Annual Kms travelled 13,900 13,900 Vehicle reg.and insurance $111

Registration costs $363 $251 Parts and Accessories $50

Servicing costs $250 $200 Total $661

The conservation case has the same fuel use reduction as the efficiency case.This could occur by

replacing driving with cycling,car pooling,or any other means with which a household reduces

driving from the Australian average of 13,900kms per year to 8,720kms per year.Reducing vehicle

mileage willreduce non-fuelrunning costs and improve the economic pay-off for this household

choice.It is therefore of interest to estimate the rebound effect with and without additional cost

savings, which are assumed for the sake of the exercise to be equal those from the efficiency case.

In both cases,the reduced motor fuel use gives a baseline potential GHG emissions reduction in

both the efficiency and conservation cases of 1,300kg CO2−e per year.

3.4.2. Household electricity

Numerous behaviouralchanges,including changing the stock of household electricalappliances,

can save money and decrease electricity use.In terms of conservation choices,cost savings from

behaviouralchanges such as shorter showers (where there is electric water heating),turning off

lights when leaving a room, and turning off stand-by appliances can save a typical household $100

per year (Foundation, 2007).

For an efficiency case that involves replacing household capital, this analysis uses the replacement

of incandescent light bulbs with compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFL), which are a cost effective

option.CFLs can produce the equivalent lighting of an incandescent bulb that requires five times

more power.In Australian supermarkets incandescent bulbs cost between $0.39 and $0.59 for a

75W globe while CFLs cost between $4.49 and $6.29 for a 15W bulbs .For simplicity,a cost of

$0.50 and $5.00 is assumed in this case for incandescent and CFLs respectively.The increased

lifespan of CFLs must be considered, which is widely claimed to be around ten times longer than

incandescent bulbs (Mirabella, 2008).A 10,000 hour life is assumed for compact fluorescents, and

1,000 for incandescent bulbs in this case study.Residential electricity price adopted is 17.10c per

kilowatt-hour for tariff 11,which was the rate for generalpower and lighting in Queensland in

2003 (Lucas, 2003).Finally, it is assumed that ten 75W bulbs are replaced by the household and

that each bulb is used for 2 hours per day.Taken together these assumptions generate a scenario

where that capitalcost oflighting per period is equal,and the cost savings arise from $75 less

11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 32

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.