Case Study: Ethical Consumerism, Affluence & Individual Factors

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|26

|17728

|237

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines ethical consumerism from a global perspective, utilizing a multilevel analysis to understand the interactions between individual-level predictors and country-level affluence. It addresses the limitations of previous Euro-centric research by incorporating data from over a doz...

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspe

A Multilevel Analysis of the Interacti

between Individual-Level Predictors

Country-Level Affluence

Nik Summers

Indiana University

ABSTRACT

Early empirical research on ethical consumerism—the deliberate purchase, or avoida

of products for political,ethical,or environmental reasons—was primarily individualistic in

nature.Recently,scholars have demonstrated the importance of structural and cultural con-

texts to the explanation of ethical consumerism,rendering explanations that fail to account

for such contextsincomplete.Unfortunately,mostof thisresearch hasbeen contained

within Europe,limiting potentially importantcountry-levelvariation.Because theories of

ethicalconsumerism suggest interactive relationships between individual- and macro-lev

variables,the Euro-centric nature of existing research raises questions about theoretical g

eralizability across all levels of analysis.This study uses the 2004 citizenship module of the

InternationalSocialSurvey Program (ISSP)—a data set that allows for increased country-

level heterogeneity while maintaining the highest standards of data quality—to run a se

of multilevel,logistic regression models with cross-levelinteractions between country-level

affluence and individual-levelpredictors.Seven of the eight individual-levelpredictors ana-

lyzed in these interactions are either more influentialin high-affluence countries than in

low-affluence countries or exhibit statistically uniform effects across the range of afflue

The lone exception is association involvement,which is more influentialas affluence de-

creases.The need to develop interactive models of political participation is discussed.

KEYWORDS : ethicalconsumerism;interaction effects;association involvement;low-cost

hypothesis; cross national.

Although sustained scholarly focus on ethicalconsumerism is recent,people across the world have

long called upon their political,ethical,and moral beliefs when making decisions in the marketp

Colonists,in what would later become the United States,forged a collective politicalidentity out of

the shared experience of boycotting British goods (Breen 2004).Severaldecades later,abolitionists,

The author thanks Patricia McManus,Fabio Rojas,Joseph DiGrazia,Michael Vasseur,and the anonymous Social Problems reviewers

for comments on this article. The author also wishes to thank Mannheim University for hosting him during the co

ticle as well as the participants of the Politics,Economy,and Culture workshop at Indiana University for the opportunity to rec

feedback on early versions ofthe project.Direct correspondence to:Nik Summers,1020 E.Kirkwood Ave.,Ballantine Hall744,

Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7103. E-mail: nesummer@indiana.edu.

VC The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for the Study of Social Problems.All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

303

Social Problems, 2016,63, 303–328

doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw009

Article

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

A Multilevel Analysis of the Interacti

between Individual-Level Predictors

Country-Level Affluence

Nik Summers

Indiana University

ABSTRACT

Early empirical research on ethical consumerism—the deliberate purchase, or avoida

of products for political,ethical,or environmental reasons—was primarily individualistic in

nature.Recently,scholars have demonstrated the importance of structural and cultural con-

texts to the explanation of ethical consumerism,rendering explanations that fail to account

for such contextsincomplete.Unfortunately,mostof thisresearch hasbeen contained

within Europe,limiting potentially importantcountry-levelvariation.Because theories of

ethicalconsumerism suggest interactive relationships between individual- and macro-lev

variables,the Euro-centric nature of existing research raises questions about theoretical g

eralizability across all levels of analysis.This study uses the 2004 citizenship module of the

InternationalSocialSurvey Program (ISSP)—a data set that allows for increased country-

level heterogeneity while maintaining the highest standards of data quality—to run a se

of multilevel,logistic regression models with cross-levelinteractions between country-level

affluence and individual-levelpredictors.Seven of the eight individual-levelpredictors ana-

lyzed in these interactions are either more influentialin high-affluence countries than in

low-affluence countries or exhibit statistically uniform effects across the range of afflue

The lone exception is association involvement,which is more influentialas affluence de-

creases.The need to develop interactive models of political participation is discussed.

KEYWORDS : ethicalconsumerism;interaction effects;association involvement;low-cost

hypothesis; cross national.

Although sustained scholarly focus on ethicalconsumerism is recent,people across the world have

long called upon their political,ethical,and moral beliefs when making decisions in the marketp

Colonists,in what would later become the United States,forged a collective politicalidentity out of

the shared experience of boycotting British goods (Breen 2004).Severaldecades later,abolitionists,

The author thanks Patricia McManus,Fabio Rojas,Joseph DiGrazia,Michael Vasseur,and the anonymous Social Problems reviewers

for comments on this article. The author also wishes to thank Mannheim University for hosting him during the co

ticle as well as the participants of the Politics,Economy,and Culture workshop at Indiana University for the opportunity to rec

feedback on early versions ofthe project.Direct correspondence to:Nik Summers,1020 E.Kirkwood Ave.,Ballantine Hall744,

Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7103. E-mail: nesummer@indiana.edu.

VC The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for the Study of Social Problems.All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

303

Social Problems, 2016,63, 303–328

doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw009

Article

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

including free blacks living in the North,opened “free produce” stores as an alternative to slave-

products and encouraged boycotting of the latter and the purchase of the former (Glick

In the 1930s, the Nazi party encouraged people to buy from German-only stores and fo

to hang “German Shop” signs in their front windows (Friedman 1996).In South Korea,the origin of

consumer goods,and especially the difference between domestically produced goods and t

in Japan,carry a symbolic importance that people carry with them to the register (Nelson

And, in Turkey, everyday citizens make choices to not purchase Coca-Cola products in

what they see as American cultural and economic imperialism (Sandıkcı and Ekici 2009

sumerism,as these examples show,covers a range ofbehavior including the deliberate purchase of

consumer products to reward companies for positive behavior (buycotting) and the del

tion of products to punish companies for objectionable behavior (boycotting).

In contemporary times, ethical consumerism has become a routine part of shopping

in many countries,and markets for organic,fair trade,and eco-labeled products have been growing

for overa decade (EcolabelIndex 2014;FairTrade Foundation 2014;FairTrade USA 2012;

Organic Trade Association 2011,2012; Steering Committee of the State-of-Knowledge Assessm

of Standards and Certification 2012).Grocery stores are now littered with products that promise

vironmental protection and, to a lesser extent,the fair treatment of poor farmers and factory worke

Certification ofethicalproduction by non-governmentalorganizations and accompanying labeling

initiatives has blossomed to become a major global effort across many industries.This “transnational

private regulation” (Bartley 2007) is intended to influence production practices across g

chains(Gereffiand Korzeniewicz1994)—somethingthathasproven difficultfor territorially

bounded nation-states (Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson 2006).Although allof this activity has resulted

in less demonstrable change in production practices than advocates have hoped for (B

2015),it is clear that ethical consumerism has become a common way that people are a

influence the “politics of products” (Micheletti2003).Some scholars argue it is analogous to social

movementactivity when the decisions ofmany individualconsumers aggregate up to a kind of

“individualised collective action” (Micheletti 2003).

A considerable amount of research has been devoted to studying the determinants o

erism in the last decade,most of which has been focused at the individual level,and much of which has

used data from a single country (Andorfer 2013; Micheletti and Stolle 2005; Strømsnes

2005).Drawing on comparative work that emphasizes the sociostructural contexts of pol

participation (Huckfeldt 1979; Schofer and Fourcade-Gourinchas 2001),a few important studies have

investigated the importance of context in providing opportunities for and constraints on

erism (Koos 2011,2012;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Stolle and Micheletti2013;Thøgersen 2010).

People do not choose whether to ethically consume in a vacuum; instead, their behavio

characteristics of the regions and countries they live in (Jacobsen and Dulsrud 2007).

These accountssuggestan interactive modelof ethicalconsumerism in which the effectof

individual-levelpredictorsvariesacrosscountry ascountry-levelcharacteristicsvary.To testthis

model,some studies have run cross-level interactions between individual- and country-le

but these analyses have been limited to the European context.As such,the influence ofcontext is

probably underestimated and important interactions between individual- and country-levariables

may be obscured by limited country-level heterogeneity (Thøgersen 2010).This study addresses this

imbalance in existing research by including overa dozen countriesfrom the GlobalSouth and

Eastern Europe,as called forrecently by leading scholarsof ethicalconsumerism (Stolle and

Micheletti2013:271) Because country-levelaffluence is the primary contextualfactor in structuring

opportunities for and constraints on both boycotting and buycotting (Koos 2012),this study exam-

ines interactions between it and the established individual-levelpredictors ofethicalconsumerism.

The most useful theoretical tool for understanding these interactions has been the low-

sis,which states that individual-levelvalues and attitudes are influentialon behavior only when con-

texts render the costs of behavior low.

304 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

products and encouraged boycotting of the latter and the purchase of the former (Glick

In the 1930s, the Nazi party encouraged people to buy from German-only stores and fo

to hang “German Shop” signs in their front windows (Friedman 1996).In South Korea,the origin of

consumer goods,and especially the difference between domestically produced goods and t

in Japan,carry a symbolic importance that people carry with them to the register (Nelson

And, in Turkey, everyday citizens make choices to not purchase Coca-Cola products in

what they see as American cultural and economic imperialism (Sandıkcı and Ekici 2009

sumerism,as these examples show,covers a range ofbehavior including the deliberate purchase of

consumer products to reward companies for positive behavior (buycotting) and the del

tion of products to punish companies for objectionable behavior (boycotting).

In contemporary times, ethical consumerism has become a routine part of shopping

in many countries,and markets for organic,fair trade,and eco-labeled products have been growing

for overa decade (EcolabelIndex 2014;FairTrade Foundation 2014;FairTrade USA 2012;

Organic Trade Association 2011,2012; Steering Committee of the State-of-Knowledge Assessm

of Standards and Certification 2012).Grocery stores are now littered with products that promise

vironmental protection and, to a lesser extent,the fair treatment of poor farmers and factory worke

Certification ofethicalproduction by non-governmentalorganizations and accompanying labeling

initiatives has blossomed to become a major global effort across many industries.This “transnational

private regulation” (Bartley 2007) is intended to influence production practices across g

chains(Gereffiand Korzeniewicz1994)—somethingthathasproven difficultfor territorially

bounded nation-states (Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson 2006).Although allof this activity has resulted

in less demonstrable change in production practices than advocates have hoped for (B

2015),it is clear that ethical consumerism has become a common way that people are a

influence the “politics of products” (Micheletti2003).Some scholars argue it is analogous to social

movementactivity when the decisions ofmany individualconsumers aggregate up to a kind of

“individualised collective action” (Micheletti 2003).

A considerable amount of research has been devoted to studying the determinants o

erism in the last decade,most of which has been focused at the individual level,and much of which has

used data from a single country (Andorfer 2013; Micheletti and Stolle 2005; Strømsnes

2005).Drawing on comparative work that emphasizes the sociostructural contexts of pol

participation (Huckfeldt 1979; Schofer and Fourcade-Gourinchas 2001),a few important studies have

investigated the importance of context in providing opportunities for and constraints on

erism (Koos 2011,2012;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Stolle and Micheletti2013;Thøgersen 2010).

People do not choose whether to ethically consume in a vacuum; instead, their behavio

characteristics of the regions and countries they live in (Jacobsen and Dulsrud 2007).

These accountssuggestan interactive modelof ethicalconsumerism in which the effectof

individual-levelpredictorsvariesacrosscountry ascountry-levelcharacteristicsvary.To testthis

model,some studies have run cross-level interactions between individual- and country-le

but these analyses have been limited to the European context.As such,the influence ofcontext is

probably underestimated and important interactions between individual- and country-levariables

may be obscured by limited country-level heterogeneity (Thøgersen 2010).This study addresses this

imbalance in existing research by including overa dozen countriesfrom the GlobalSouth and

Eastern Europe,as called forrecently by leading scholarsof ethicalconsumerism (Stolle and

Micheletti2013:271) Because country-levelaffluence is the primary contextualfactor in structuring

opportunities for and constraints on both boycotting and buycotting (Koos 2012),this study exam-

ines interactions between it and the established individual-levelpredictors ofethicalconsumerism.

The most useful theoretical tool for understanding these interactions has been the low-

sis,which states that individual-levelvalues and attitudes are influentialon behavior only when con-

texts render the costs of behavior low.

304 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

The inclusion of non-Western countries alerts scholars to the dangers of theoretical

zation and has practicalimplications for the development of ethicalconsumerism beyond the West.

These are important issues as ethical consumerism is both an important type of politic

self and an important pathway to broader political consciousness,especially for marginalized popula-

tions (Stolle and Micheletti2013).The results of this study highlight the importance of interac

modelsof ethicalconsumerism and ofpoliticalparticipation more generally.Generalizing from

single-country models,or even from models that use multicountry aggregated data,can lead to in-

complete or even plainly wrong conclusions about the determinants of participation.

E T H I C A L C O N S U M E R I S M A S P O L I T I C S

Although many scholars have accepted ethical consumerism as a meaningful form of p

ment, others remain skeptical.Critics charge companies with “green-” and “fair-washing” and

icaland environmentally responsible production have become commoditized.Gay Seidman (2007)

has documented a race-to-the-bottom in productcertification and labeling,as companies work to

find the least costly certification that enables them to claim ethical production.In addition to the wa-

tering down of standards, observers see in this process a cynical ploy to appeal to the

of wealthy consumers willing to spend more for conspicuous specialty products,not a plausible way

to significantly alter production practices of polluting or exploitative companies (Goodm

Moreover,ethicalconsumerism often occurs when individuals,alone in grocery store aisles,at-

temptto weigh information presented on confusing ormisleading productlabels (Bostro¨m and

Klintman 2008).It is hard to see how consumers,acting on the basis of such information,can act as

sophisticated regulators of global capitalism; instead, there is evidence that consumer

bels heuristically,as rough guarantees of responsible production (Adams and RaisboroughIn

this attempt to turn consumers into regulators through product information (Schneibe

2008),critics see a dangerous “individualization of responsibility” for collective problem

tinuation ofthe neoliberalturn from governmentto governance (Bevirand Trentmann 2007;

Maniates 2001; Maniates and Meyer 2010).The concern is that consumers,now burdened with the

responsibility for global problems when making purchases (Barnett et al.2011; Sassatelli 2007; Stolle

and Micheletti2013),view their job as done once the purchase is made (Smith 1998).Ethicalcon-

sumerism may lead to the atrophy of collective action if it induces a false sense of poliefficacy

(Szasz 2007).

Furthermore,the goals of corporations are profit and growth not the protection of the e

ment or the rights of workers,and most industries are characterized by intense competition a

pressure (Dauvergne and Lister 2013).In such an environment,good intentions can be swept aside

by competitive pressures from companies thatlack commitmentto ethicalprinciples.As a result,

there isskepticism thatthe capitalistmarketis institutionally suited to delivering socialchange.

Instead,government regulation is seen as the only force strong enough to fundamentall

duction practices; effort expended elsewhere is “frolic and detour” (Reich 2008:14).Ethical consum-

erism as a means of politics appears even more dubious when one considers the size o

for labeled products and the willingness of consumers to pay associated price premiumEven sup-

porters are forced to acknowledge that markets for labeled products are niche and the

suggests a small minority of the population is willing to pay more for guarantees of eth

(Bartley et al. 2015:ch. 2; Hainmueller and Hiscox 2015; Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Seq

One response to these critiques is to acknowledge that ethical consumerism can be

and parochial,butto pointoutthatmuch conventionalparticipation is as well(Schudson 2007;

Willis and Schor 2012).The idea that democratic politics is guided by civic-mindedness whi

sumer behavior is oriented to narrow self-interest does not hold up to scrutiny.Instead,market be-

havior is “utterly saturated” (Malpass et al.2007) with morality (Zelizer 2009) and is embedded

social roles and relationships (Barnett et al.2011; Clarke 2008; Granovetter 1985),while democratic

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective305

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

zation and has practicalimplications for the development of ethicalconsumerism beyond the West.

These are important issues as ethical consumerism is both an important type of politic

self and an important pathway to broader political consciousness,especially for marginalized popula-

tions (Stolle and Micheletti2013).The results of this study highlight the importance of interac

modelsof ethicalconsumerism and ofpoliticalparticipation more generally.Generalizing from

single-country models,or even from models that use multicountry aggregated data,can lead to in-

complete or even plainly wrong conclusions about the determinants of participation.

E T H I C A L C O N S U M E R I S M A S P O L I T I C S

Although many scholars have accepted ethical consumerism as a meaningful form of p

ment, others remain skeptical.Critics charge companies with “green-” and “fair-washing” and

icaland environmentally responsible production have become commoditized.Gay Seidman (2007)

has documented a race-to-the-bottom in productcertification and labeling,as companies work to

find the least costly certification that enables them to claim ethical production.In addition to the wa-

tering down of standards, observers see in this process a cynical ploy to appeal to the

of wealthy consumers willing to spend more for conspicuous specialty products,not a plausible way

to significantly alter production practices of polluting or exploitative companies (Goodm

Moreover,ethicalconsumerism often occurs when individuals,alone in grocery store aisles,at-

temptto weigh information presented on confusing ormisleading productlabels (Bostro¨m and

Klintman 2008).It is hard to see how consumers,acting on the basis of such information,can act as

sophisticated regulators of global capitalism; instead, there is evidence that consumer

bels heuristically,as rough guarantees of responsible production (Adams and RaisboroughIn

this attempt to turn consumers into regulators through product information (Schneibe

2008),critics see a dangerous “individualization of responsibility” for collective problem

tinuation ofthe neoliberalturn from governmentto governance (Bevirand Trentmann 2007;

Maniates 2001; Maniates and Meyer 2010).The concern is that consumers,now burdened with the

responsibility for global problems when making purchases (Barnett et al.2011; Sassatelli 2007; Stolle

and Micheletti2013),view their job as done once the purchase is made (Smith 1998).Ethicalcon-

sumerism may lead to the atrophy of collective action if it induces a false sense of poliefficacy

(Szasz 2007).

Furthermore,the goals of corporations are profit and growth not the protection of the e

ment or the rights of workers,and most industries are characterized by intense competition a

pressure (Dauvergne and Lister 2013).In such an environment,good intentions can be swept aside

by competitive pressures from companies thatlack commitmentto ethicalprinciples.As a result,

there isskepticism thatthe capitalistmarketis institutionally suited to delivering socialchange.

Instead,government regulation is seen as the only force strong enough to fundamentall

duction practices; effort expended elsewhere is “frolic and detour” (Reich 2008:14).Ethical consum-

erism as a means of politics appears even more dubious when one considers the size o

for labeled products and the willingness of consumers to pay associated price premiumEven sup-

porters are forced to acknowledge that markets for labeled products are niche and the

suggests a small minority of the population is willing to pay more for guarantees of eth

(Bartley et al. 2015:ch. 2; Hainmueller and Hiscox 2015; Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Seq

One response to these critiques is to acknowledge that ethical consumerism can be

and parochial,butto pointoutthatmuch conventionalparticipation is as well(Schudson 2007;

Willis and Schor 2012).The idea that democratic politics is guided by civic-mindedness whi

sumer behavior is oriented to narrow self-interest does not hold up to scrutiny.Instead,market be-

havior is “utterly saturated” (Malpass et al.2007) with morality (Zelizer 2009) and is embedded

social roles and relationships (Barnett et al.2011; Clarke 2008; Granovetter 1985),while democratic

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective305

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

You're viewing a preview

Unlock full access by subscribing today!

politics can be viciously competitive and self-interested.Is voting to keep one’s personaltaxes low

any more civic-minded than purchasing fair trade coffee?

As for concerns that ethical consumerism diverts attention from other types of particthere

is little evidence that it does so.Instead,across small- and large-sample studies the evidence po

clearly in the direction of compatibility between ethical consumerism and other types o

(Clarke et al.2007;Connolly and Prothero 2008;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Stolle,Hooghe,and

Micheletti2005;Willis and Schor 2012) and supports a view ofethicalconsumerism as “one in a

toolkit of [political] actions” (Willis and Schor 2012:166) and an expansion of the partic

ertoire (Micheletti 2003).

Another response is to point out that there are important indirect effects of ethicalconsumerism

that are often overlooked by critics.Clive Barnett and colleagues (2011) show that ethical consu

ism provides organizations with rhetoricalresources to make claims on nation-states;in struggles

with legislatorsand otherstakeholders,the demand forlabeled productsbecomesevidence for

broad-based desire for legislative action.In this way,and in others,ethical consumerism allows multi-

national corporations,transnational governance organizations,and nation-states to engage in politics

in ways that would not be possible if limited to conventional channels (Micheletti 2003)

directeffectis the potentialthatethicalconsumerism has to awaken politicalconsciousness that

would otherwise lie dormant.When consumption is politicized people have fodder for the dev

ment of new political identities (Shaw,Newholm,and Dickinson 2006) as the purchase of products

becomes “proof of the importance of their [political] aspirations” (Sassatelli 2006:221).Ethicalcon-

sumerism acts as a venue for the exploration of new politicalidentities that are subsequently “trans-

lated into rights and then become the basis of political action” (Hilton 2003:315).

These “venues for action” (Micheletti2003) may be especially important for women,racialand

ethnic minorities,and other groups marginalized within conventionalpolitics.Ethicalconsumerism

has amplified the political voice of African Americans during the American Revolution (

the abolitionist movement (Glickman 2004),the Great Depression (Greenberg 1999),and the civil

rights movement (Cohen 2004).Excluded from conventionalpolitics,even unable to cast votes for

representation,women,and especially housewives,have been at the center of many buycott and bo

cott campaigns throughout history (Davies 2001; Hilton 2002; Sassatelli2007).Boycotting has also

been famously recognized as a “weapon ofthe weak” whether itis used by poor Malaysian field-

workers to resist the power of plantation owners (Scott [1985] 2008) or by poor Irish re

with the behavior of English landlords (Friedman 1999).

Beyond the West

Because consumer power has historically been centralized in the developed economies

industrialized world mostof the demand-side focus on ethicalconsumerism has been on Western

Europe and the Anglo offshoots.People with fewer “financialdegrees offreedom” and who live in

countries with economies that provide a low assortment of goods have less opportunity

sume (Koos 2012:40). Why, then, study ethical consumerism beyond the West?

For one, the emergence of significant consumer demand around the world means tha

labeled products,even when such products are more expensive,are no longer limited to the West

(Hobson 2004;Klein 2009;Stolle and Micheletti2013:ch.8). Non-Western countries,across the

spectrum ofaffluence,are now a significantpartof transnationallabeling initiatives such as the

Global Ecolabelling Network (GEN 2014) and rates of ethicalconsumption meet or exceed 10 per-

cent in numerous non-Western countries in the InternationalSocialSurvey Program (ISSP 2004)

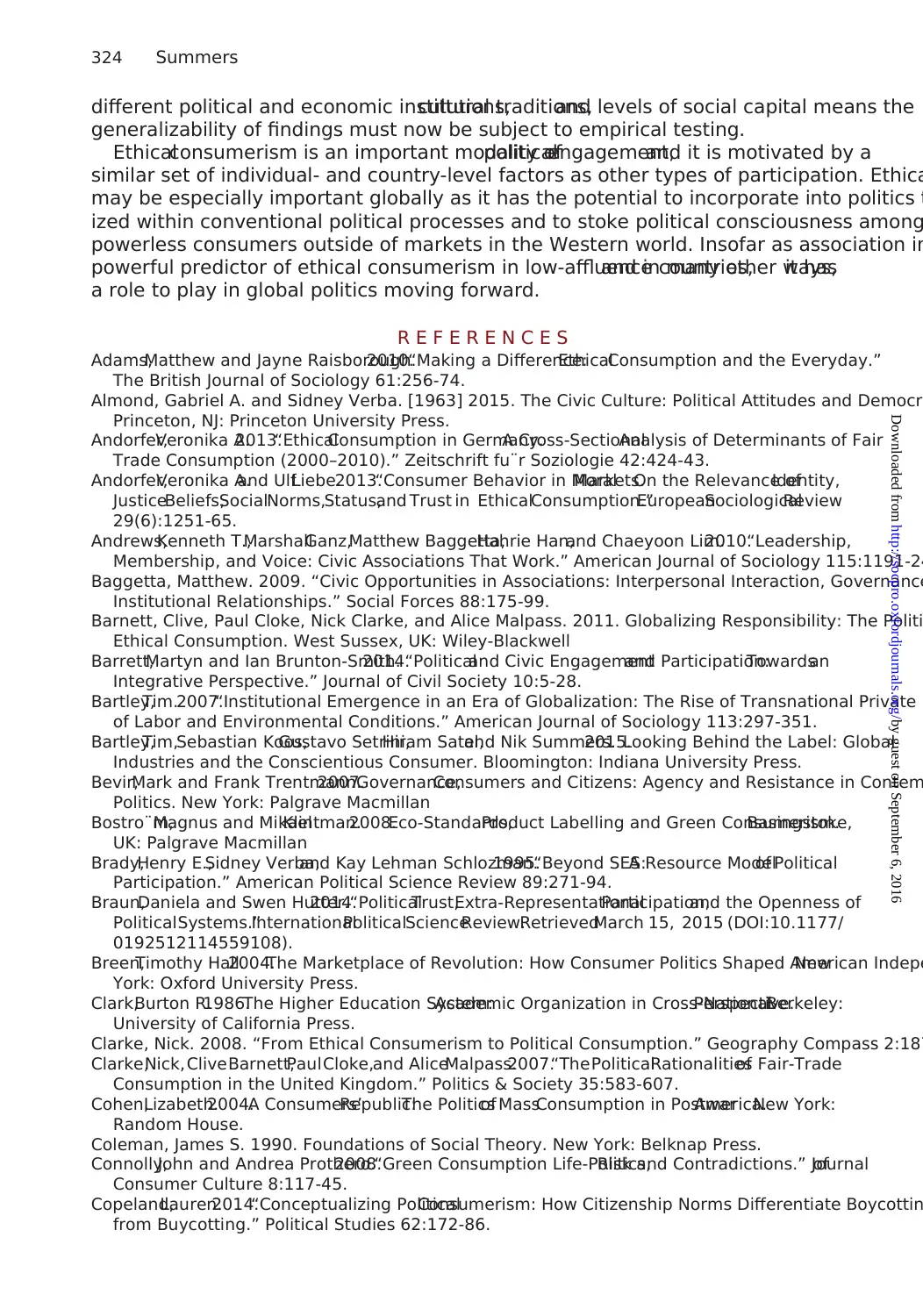

sample,as displayed in Figure 1.Moreover,some forms ofethicalconsumerism are low cost.One

can engage in ethicalconsumerism simply by consciously rejecting one of two similarly price

natives in favor of the other,as occurs in cases of politically motivated brand rejection (Sandık

Ekici 2009).

306 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

any more civic-minded than purchasing fair trade coffee?

As for concerns that ethical consumerism diverts attention from other types of particthere

is little evidence that it does so.Instead,across small- and large-sample studies the evidence po

clearly in the direction of compatibility between ethical consumerism and other types o

(Clarke et al.2007;Connolly and Prothero 2008;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Stolle,Hooghe,and

Micheletti2005;Willis and Schor 2012) and supports a view ofethicalconsumerism as “one in a

toolkit of [political] actions” (Willis and Schor 2012:166) and an expansion of the partic

ertoire (Micheletti 2003).

Another response is to point out that there are important indirect effects of ethicalconsumerism

that are often overlooked by critics.Clive Barnett and colleagues (2011) show that ethical consu

ism provides organizations with rhetoricalresources to make claims on nation-states;in struggles

with legislatorsand otherstakeholders,the demand forlabeled productsbecomesevidence for

broad-based desire for legislative action.In this way,and in others,ethical consumerism allows multi-

national corporations,transnational governance organizations,and nation-states to engage in politics

in ways that would not be possible if limited to conventional channels (Micheletti 2003)

directeffectis the potentialthatethicalconsumerism has to awaken politicalconsciousness that

would otherwise lie dormant.When consumption is politicized people have fodder for the dev

ment of new political identities (Shaw,Newholm,and Dickinson 2006) as the purchase of products

becomes “proof of the importance of their [political] aspirations” (Sassatelli 2006:221).Ethicalcon-

sumerism acts as a venue for the exploration of new politicalidentities that are subsequently “trans-

lated into rights and then become the basis of political action” (Hilton 2003:315).

These “venues for action” (Micheletti2003) may be especially important for women,racialand

ethnic minorities,and other groups marginalized within conventionalpolitics.Ethicalconsumerism

has amplified the political voice of African Americans during the American Revolution (

the abolitionist movement (Glickman 2004),the Great Depression (Greenberg 1999),and the civil

rights movement (Cohen 2004).Excluded from conventionalpolitics,even unable to cast votes for

representation,women,and especially housewives,have been at the center of many buycott and bo

cott campaigns throughout history (Davies 2001; Hilton 2002; Sassatelli2007).Boycotting has also

been famously recognized as a “weapon ofthe weak” whether itis used by poor Malaysian field-

workers to resist the power of plantation owners (Scott [1985] 2008) or by poor Irish re

with the behavior of English landlords (Friedman 1999).

Beyond the West

Because consumer power has historically been centralized in the developed economies

industrialized world mostof the demand-side focus on ethicalconsumerism has been on Western

Europe and the Anglo offshoots.People with fewer “financialdegrees offreedom” and who live in

countries with economies that provide a low assortment of goods have less opportunity

sume (Koos 2012:40). Why, then, study ethical consumerism beyond the West?

For one, the emergence of significant consumer demand around the world means tha

labeled products,even when such products are more expensive,are no longer limited to the West

(Hobson 2004;Klein 2009;Stolle and Micheletti2013:ch.8). Non-Western countries,across the

spectrum ofaffluence,are now a significantpartof transnationallabeling initiatives such as the

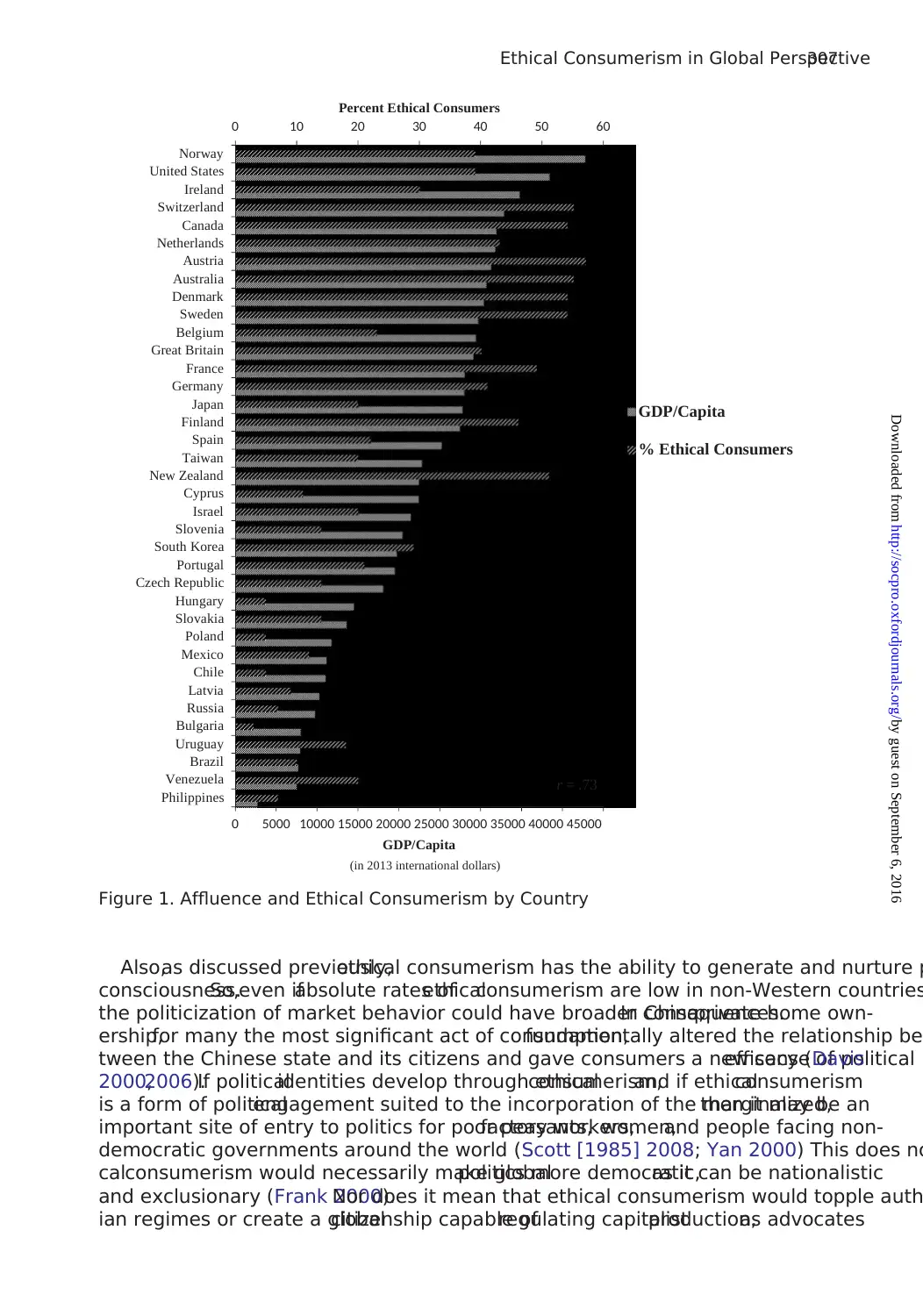

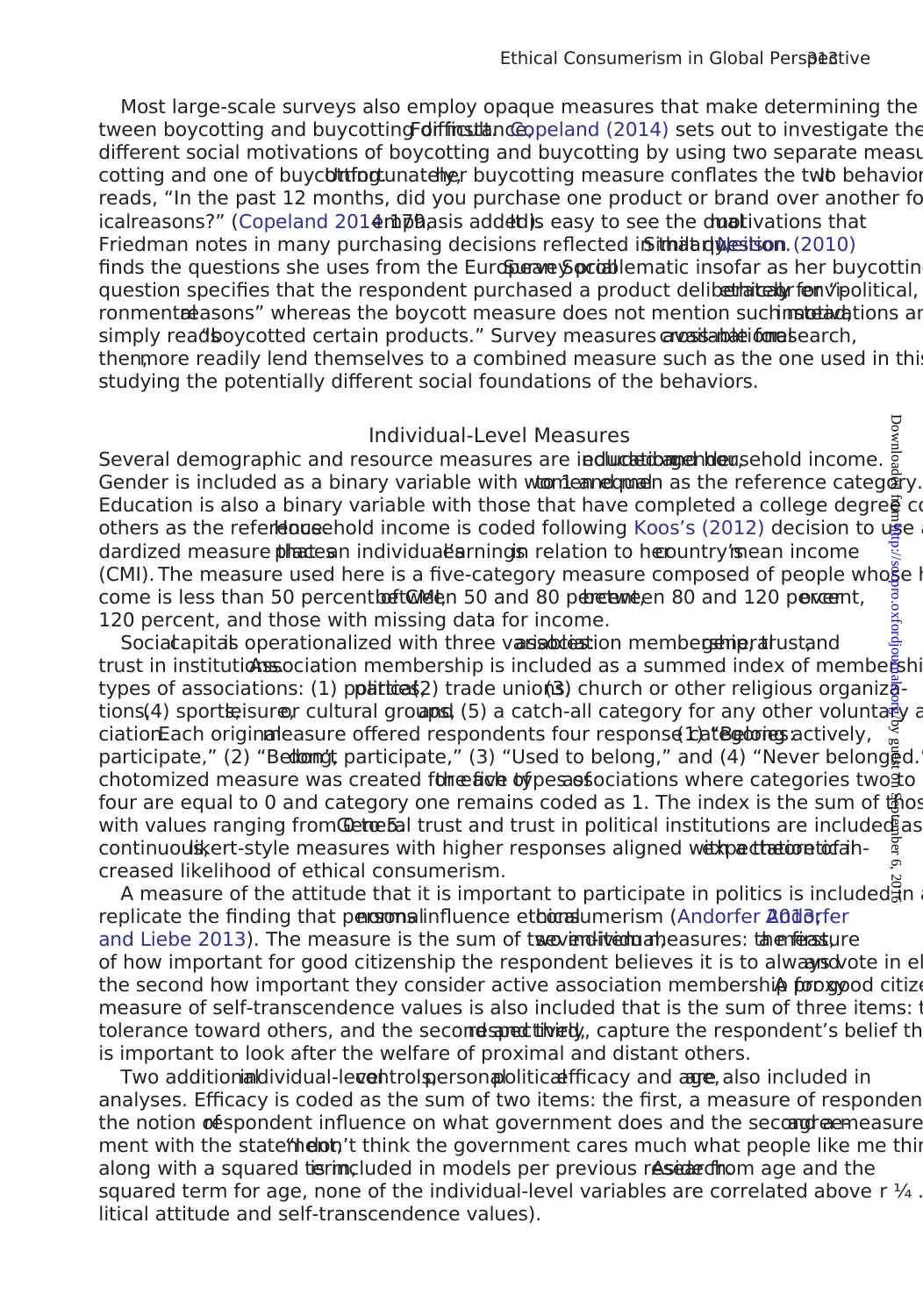

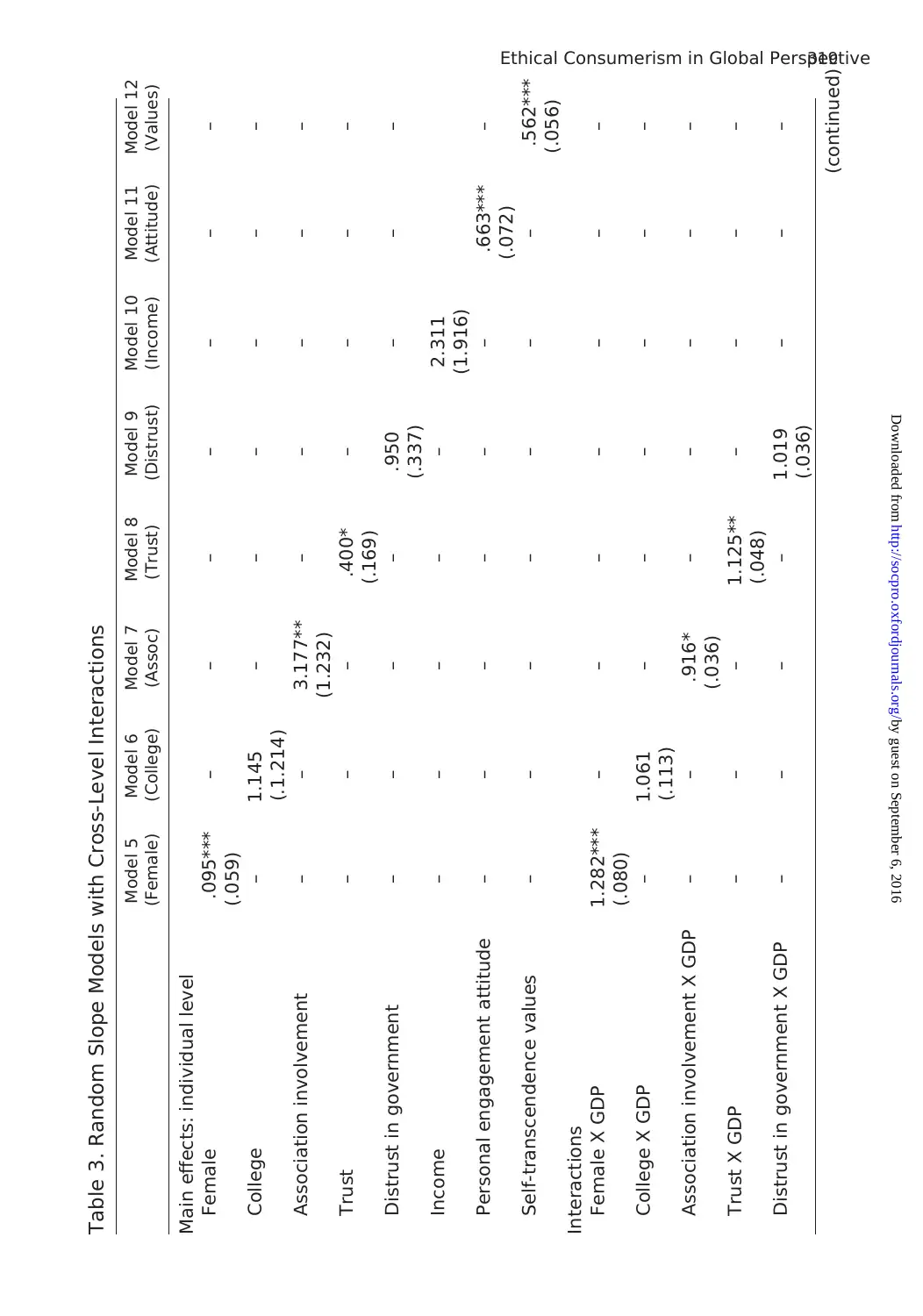

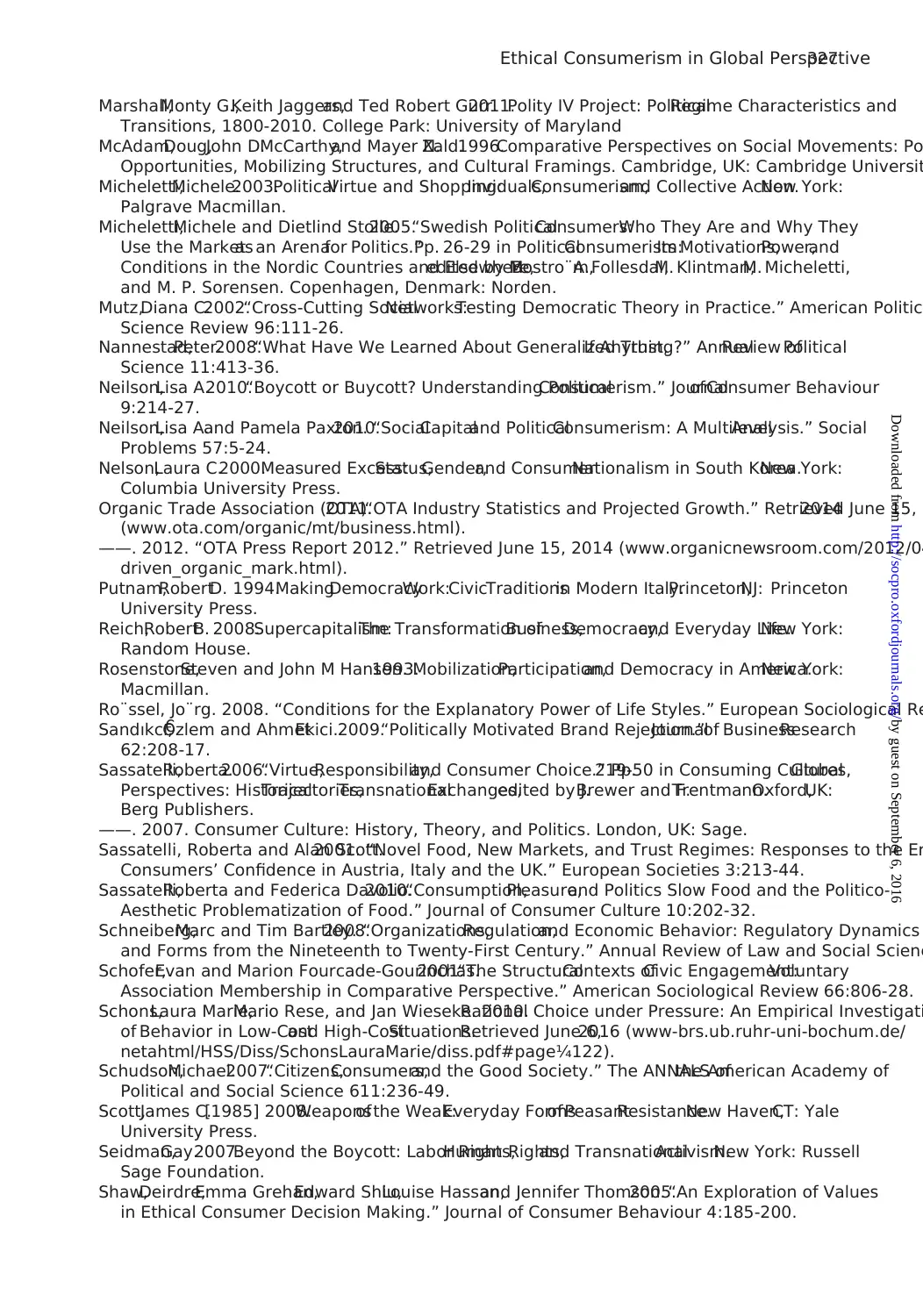

Global Ecolabelling Network (GEN 2014) and rates of ethicalconsumption meet or exceed 10 per-

cent in numerous non-Western countries in the InternationalSocialSurvey Program (ISSP 2004)

sample,as displayed in Figure 1.Moreover,some forms ofethicalconsumerism are low cost.One

can engage in ethicalconsumerism simply by consciously rejecting one of two similarly price

natives in favor of the other,as occurs in cases of politically motivated brand rejection (Sandık

Ekici 2009).

306 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Also,as discussed previously,ethical consumerism has the ability to generate and nurture p

consciousness.So,even ifabsolute rates ofethicalconsumerism are low in non-Western countries

the politicization of market behavior could have broader consequences.In China,private home own-

ership,for many the most significant act of consumption,fundamentally altered the relationship be

tween the Chinese state and its citizens and gave consumers a new sense of politicalefficacy (Davis

2000,2006).If politicalidentities develop through ethicalconsumerism,and if ethicalconsumerism

is a form of politicalengagement suited to the incorporation of the marginalized,then it may be an

important site of entry to politics for poor peasants,factory workers,women,and people facing non-

democratic governments around the world (Scott [1985] 2008; Yan 2000) This does no

calconsumerism would necessarily make globalpolitics more democratic,as it can be nationalistic

and exclusionary (Frank 2000).Nor does it mean that ethical consumerism would topple auth

ian regimes or create a globalcitizenship capable ofregulating capitalistproduction,as advocates

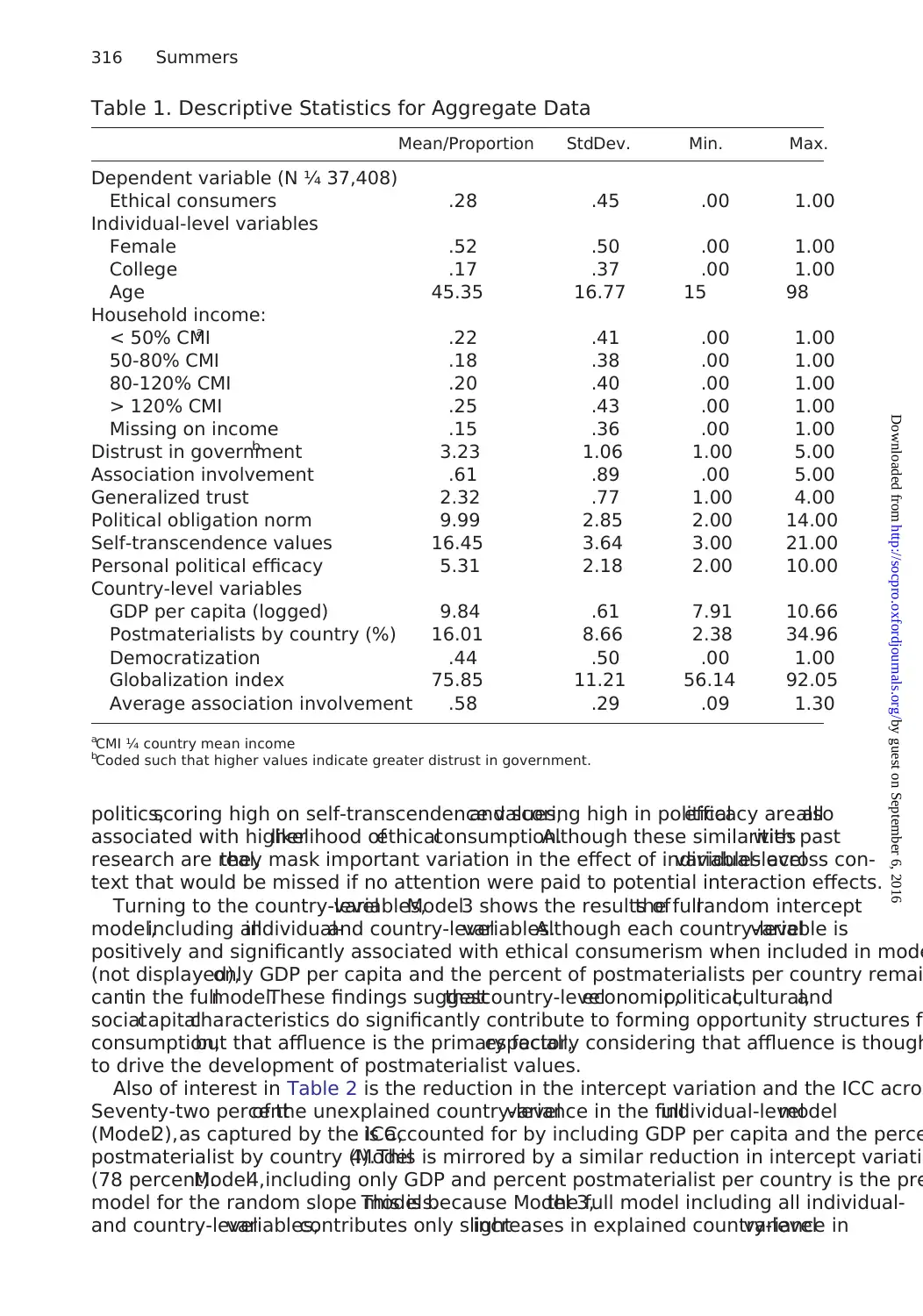

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 40000 45000

Philippines

Venezuela

Brazil

Uruguay

Bulgaria

Russia

Latvia

Chile

Mexico

Poland

Slovakia

Hungary

Czech Republic

Portugal

South Korea

Slovenia

Israel

Cyprus

New Zealand

Taiwan

Spain

Finland

Japan

Germany

France

Great Britain

Belgium

Sweden

Denmark

Australia

Austria

Netherlands

Canada

Switzerland

Ireland

United States

Norway

Percent Ethical Consumers

GDP/Capita

GDP/Capita

% Ethical Consumers

r = .73

(in 2013 international dollars)

Figure 1. Affluence and Ethical Consumerism by Country

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective307

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

consciousness.So,even ifabsolute rates ofethicalconsumerism are low in non-Western countries

the politicization of market behavior could have broader consequences.In China,private home own-

ership,for many the most significant act of consumption,fundamentally altered the relationship be

tween the Chinese state and its citizens and gave consumers a new sense of politicalefficacy (Davis

2000,2006).If politicalidentities develop through ethicalconsumerism,and if ethicalconsumerism

is a form of politicalengagement suited to the incorporation of the marginalized,then it may be an

important site of entry to politics for poor peasants,factory workers,women,and people facing non-

democratic governments around the world (Scott [1985] 2008; Yan 2000) This does no

calconsumerism would necessarily make globalpolitics more democratic,as it can be nationalistic

and exclusionary (Frank 2000).Nor does it mean that ethical consumerism would topple auth

ian regimes or create a globalcitizenship capable ofregulating capitalistproduction,as advocates

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 40000 45000

Philippines

Venezuela

Brazil

Uruguay

Bulgaria

Russia

Latvia

Chile

Mexico

Poland

Slovakia

Hungary

Czech Republic

Portugal

South Korea

Slovenia

Israel

Cyprus

New Zealand

Taiwan

Spain

Finland

Japan

Germany

France

Great Britain

Belgium

Sweden

Denmark

Australia

Austria

Netherlands

Canada

Switzerland

Ireland

United States

Norway

Percent Ethical Consumers

GDP/Capita

GDP/Capita

% Ethical Consumers

r = .73

(in 2013 international dollars)

Figure 1. Affluence and Ethical Consumerism by Country

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective307

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

hope.But if ethicalconsumerism is another pathway to political consciousness and participaes-

pecially for those marginalized within global political processes, then it is an expansion

repertoire for those that most need it.

P R E D I C T O R S O F E T H I C A L C O N S U M E R I S M

The empirical focus of this article is testing the interactive nature of the individual- and

determinants of ethical consumerism. At the individual level, ethical consumerism is m

mographic characteristics,resources such as income and education,social capital,and “motivational”

factors such as values,norms,and attitudes.At the contextuallevel,country-levelaffluence is espe-

cially powerfulbut other macro factors are important as well,including additionaleconomic charac-

teristics,politicalstructures,culture,and socialcapital.Together,these contextualforces represent

the opportunity structures (McAdam,McCarthy,and Zald 1996) for ethical consumerism that pow

erfully shape individual-level behavior.

Individual-Level Predictors

Demographic Characteristics

Most studies find that women ethically consume at higher rates than men (Ferrer and F

Forno and Ceccarini 2006; Koos 2012; Micheletti and Stolle 2005; Neilson and Paxton 2

and Micheletti 2006, 2013; Strømsnes 2005; Tobiasen 2005; Yates 2011). Although this

attributed to the idea that women shop more,there is evidence that the gender effect persists ev

when amount ofshopping is controlled for (Michelettiand Stolle 2005).More likely explanations

are that women tend to be involved at higher rates in voluntary associations,such as animalrights

groups,that prime people for ethicalconsumerism or that women are more likely to hold attitud

and values consistent with the protection of the environment or labor rights (Stolle and

2006).Ethical consumerism may also be more attractive to women than more conventio

politics for severalreasons,including that it lacks a hierarchicalparticipatory structure and member-

ship requirements(Marien,Hooghe,and Quintelier2010;Stolle and Hooghe 2011;Stolle and

Micheletti 2006).Age has also been included in most previous studies,though typically as a control

variable without much in the way of interpretation.

Resources for Participation

Education is the most consistent individual-levelpredictor of ethicalconsumerism (see studies cited

above for gender finding).This is not surprising given the overwhelming and positive associat

education with other types of political participation (Kam and Palmer 2008; Rosenstone

1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995) and is typically explained through a simple r

(Brady,Verba,and Schlozman 1995) that argues education provides people with cognitiveinforma-

tional,and motivational resources to act.Understanding the politics of products and sorting throu

the claims made on product labels can be daunting tasks,and education provides people with the

skills to complete them.Education may also provide people with the requisite culturalcapitalto

know how to use their consumption decisions to signalsuperior socialstatus and,thus,it may con-

tribute to class-based,symbolic exclusion (Andorfer 2013;Johnston 2008;Johnston and Baumann

2010).

Results for household income have been uneven.Sebastian Koos (2012) argues this inconsistenc

is a result of the conflation of boycotting and buycotting and demonstrates that income

predictor ofbuycotting but not boycotting when they are disaggregated,using data from the 2003

European SocialSurvey (ESS).Lauren Copeland (2014),however,using data from the United

States,obtains different results when disaggregating the behavior even further.She finds that income

is not usefulin distinguishing boycotters or buycotters from those that do not ethically co

while itis usefulin distinguishing “dualcotters” from “nocotters.” To furthercomplicate matters,

308 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

pecially for those marginalized within global political processes, then it is an expansion

repertoire for those that most need it.

P R E D I C T O R S O F E T H I C A L C O N S U M E R I S M

The empirical focus of this article is testing the interactive nature of the individual- and

determinants of ethical consumerism. At the individual level, ethical consumerism is m

mographic characteristics,resources such as income and education,social capital,and “motivational”

factors such as values,norms,and attitudes.At the contextuallevel,country-levelaffluence is espe-

cially powerfulbut other macro factors are important as well,including additionaleconomic charac-

teristics,politicalstructures,culture,and socialcapital.Together,these contextualforces represent

the opportunity structures (McAdam,McCarthy,and Zald 1996) for ethical consumerism that pow

erfully shape individual-level behavior.

Individual-Level Predictors

Demographic Characteristics

Most studies find that women ethically consume at higher rates than men (Ferrer and F

Forno and Ceccarini 2006; Koos 2012; Micheletti and Stolle 2005; Neilson and Paxton 2

and Micheletti 2006, 2013; Strømsnes 2005; Tobiasen 2005; Yates 2011). Although this

attributed to the idea that women shop more,there is evidence that the gender effect persists ev

when amount ofshopping is controlled for (Michelettiand Stolle 2005).More likely explanations

are that women tend to be involved at higher rates in voluntary associations,such as animalrights

groups,that prime people for ethicalconsumerism or that women are more likely to hold attitud

and values consistent with the protection of the environment or labor rights (Stolle and

2006).Ethical consumerism may also be more attractive to women than more conventio

politics for severalreasons,including that it lacks a hierarchicalparticipatory structure and member-

ship requirements(Marien,Hooghe,and Quintelier2010;Stolle and Hooghe 2011;Stolle and

Micheletti 2006).Age has also been included in most previous studies,though typically as a control

variable without much in the way of interpretation.

Resources for Participation

Education is the most consistent individual-levelpredictor of ethicalconsumerism (see studies cited

above for gender finding).This is not surprising given the overwhelming and positive associat

education with other types of political participation (Kam and Palmer 2008; Rosenstone

1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995) and is typically explained through a simple r

(Brady,Verba,and Schlozman 1995) that argues education provides people with cognitiveinforma-

tional,and motivational resources to act.Understanding the politics of products and sorting throu

the claims made on product labels can be daunting tasks,and education provides people with the

skills to complete them.Education may also provide people with the requisite culturalcapitalto

know how to use their consumption decisions to signalsuperior socialstatus and,thus,it may con-

tribute to class-based,symbolic exclusion (Andorfer 2013;Johnston 2008;Johnston and Baumann

2010).

Results for household income have been uneven.Sebastian Koos (2012) argues this inconsistenc

is a result of the conflation of boycotting and buycotting and demonstrates that income

predictor ofbuycotting but not boycotting when they are disaggregated,using data from the 2003

European SocialSurvey (ESS).Lauren Copeland (2014),however,using data from the United

States,obtains different results when disaggregating the behavior even further.She finds that income

is not usefulin distinguishing boycotters or buycotters from those that do not ethically co

while itis usefulin distinguishing “dualcotters” from “nocotters.” To furthercomplicate matters,

308 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

You're viewing a preview

Unlock full access by subscribing today!

Lisa A.Neilson (2010),using ESS data,finds that income is useful in distinguishing boycotters,buy-

cotters,and dualcottersfrom nocotters.More research isneeded to untangle thiscomplicated

relationship.

Social Capital

Membership in voluntary associations,whether explicitly political or not,is predictive of political par-

ticipation ofvarious types (Almond and Verba [1963] 2015;Leighley 1995;Verba and Nie 1972)

and thisrelationship holdsfor ethicalconsumerism (Neilson 2010;Neilson and Paxton 2010).

Associations increase interest in political matters (Andrews et al.2010),generate feelings of trust and

reciprocity (Fukuyama 1995; Putnam 1994),and provide opportunities for the development of ci

skills that facilitate engagement (Baggetta 2009). With respect to ethical consumerism

volvement supplies people with information to make consumption decisions and motiv

on that information (Neilson and Paxton 2010).Associations increase access to information by in

creasing the number of weak ties that people have—relationships that are particularly

transmission of novel information (Granovetter 1985; Mutz 2002; Neilson 2010; Warde

also increase normative pressure to act (Andrews et al.2010; Clarke et al.2007) by exposing people

to visible consumption norms and sanctions tied to norm violation (Neilson and Paxton

General trust is thought to increase rates of ethical consumerism as it creates an ex

iprocity and alleviates concerns people have thatothers willfree ride on their efforts (Nannestad

2008).Trust in political institutions is expected to be negatively correlated with ethical c

because if people believe in the efficacy of conventional politics they may be less likel

politicalenergies toward the market (Stolle et al.2005).Cross-nationalresearch finds evidence in

support of both of these expectations (Koos 2012; Neilson and Paxton 2010).

MotivationalFactors: Values,Norms,and Attitudes

Values, norms, and attitudes are viewed as “motivational” factors that are crucial to u

decision to ethically consume (Andorfer 2013;Andorfer and Liebe 2013;Koos 2012;Shaw etal.

2005;Sunderer and Ro¨ssel2012).Ronald Inglehart’s (1990,1997) work on postmaterialism has

been especially prominent here, as scholars have found strong evidence that postmat

influential predictors of ethical consumerism (Stolle et al.2005).As societies develop economically a

macro-levelvalue shift from materialism to postmaterialism occurs,quality of life issues such as hu-

man rights gain prominence,and people become more likely to ethically consume as a resultOther

values are important as well,including solidarity and concern for the environment (Andorfer 2

independence and equality (Shaw et al.2005),and self-transcendence (Koos 2012).More proximal

to ethical consumerism itself,holding positive attitudes toward fair trade and feeling a person

gation to help through one’spurchasesare also importantpredictorsof ethicalconsumerism

(Andorfer 2013; Andorfer and Liebe 2013; Sunderer and Ro¨ssel 2012).

Contextual Predictors

Scholars of ethical consumerism have recently applied insights from the opportunity s

ture (McAdam et al.1996) to describe how characteristics of countries and regions constra

able individual-levelethicalconsumption (Koos 2011,2012;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Thøgersen

2010; Wahlstro¨m and Peterson 2006).The idea is quite simple: individual-levelconsumption deci-

sions occur within contexts that powerfully shape resource distributions,opportunities to ethically

consume,and cultures ofconsumption and politicalengagement.Economic,political,and cultural

characteristics have all been identified as important, as well as contextual social capita

Economic characteristics are thoughtto be especially importantfor providing households with

enough resources to ethically consume and enough opportunities to do so.More specifically,impor-

tant economic factors include retailing and price structures,the supply oflabeled goods,aggregate

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective309

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

cotters,and dualcottersfrom nocotters.More research isneeded to untangle thiscomplicated

relationship.

Social Capital

Membership in voluntary associations,whether explicitly political or not,is predictive of political par-

ticipation ofvarious types (Almond and Verba [1963] 2015;Leighley 1995;Verba and Nie 1972)

and thisrelationship holdsfor ethicalconsumerism (Neilson 2010;Neilson and Paxton 2010).

Associations increase interest in political matters (Andrews et al.2010),generate feelings of trust and

reciprocity (Fukuyama 1995; Putnam 1994),and provide opportunities for the development of ci

skills that facilitate engagement (Baggetta 2009). With respect to ethical consumerism

volvement supplies people with information to make consumption decisions and motiv

on that information (Neilson and Paxton 2010).Associations increase access to information by in

creasing the number of weak ties that people have—relationships that are particularly

transmission of novel information (Granovetter 1985; Mutz 2002; Neilson 2010; Warde

also increase normative pressure to act (Andrews et al.2010; Clarke et al.2007) by exposing people

to visible consumption norms and sanctions tied to norm violation (Neilson and Paxton

General trust is thought to increase rates of ethical consumerism as it creates an ex

iprocity and alleviates concerns people have thatothers willfree ride on their efforts (Nannestad

2008).Trust in political institutions is expected to be negatively correlated with ethical c

because if people believe in the efficacy of conventional politics they may be less likel

politicalenergies toward the market (Stolle et al.2005).Cross-nationalresearch finds evidence in

support of both of these expectations (Koos 2012; Neilson and Paxton 2010).

MotivationalFactors: Values,Norms,and Attitudes

Values, norms, and attitudes are viewed as “motivational” factors that are crucial to u

decision to ethically consume (Andorfer 2013;Andorfer and Liebe 2013;Koos 2012;Shaw etal.

2005;Sunderer and Ro¨ssel2012).Ronald Inglehart’s (1990,1997) work on postmaterialism has

been especially prominent here, as scholars have found strong evidence that postmat

influential predictors of ethical consumerism (Stolle et al.2005).As societies develop economically a

macro-levelvalue shift from materialism to postmaterialism occurs,quality of life issues such as hu-

man rights gain prominence,and people become more likely to ethically consume as a resultOther

values are important as well,including solidarity and concern for the environment (Andorfer 2

independence and equality (Shaw et al.2005),and self-transcendence (Koos 2012).More proximal

to ethical consumerism itself,holding positive attitudes toward fair trade and feeling a person

gation to help through one’spurchasesare also importantpredictorsof ethicalconsumerism

(Andorfer 2013; Andorfer and Liebe 2013; Sunderer and Ro¨ssel 2012).

Contextual Predictors

Scholars of ethical consumerism have recently applied insights from the opportunity s

ture (McAdam et al.1996) to describe how characteristics of countries and regions constra

able individual-levelethicalconsumption (Koos 2011,2012;Neilson and Paxton 2010;Thøgersen

2010; Wahlstro¨m and Peterson 2006).The idea is quite simple: individual-levelconsumption deci-

sions occur within contexts that powerfully shape resource distributions,opportunities to ethically

consume,and cultures ofconsumption and politicalengagement.Economic,political,and cultural

characteristics have all been identified as important, as well as contextual social capita

Economic characteristics are thoughtto be especially importantfor providing households with

enough resources to ethically consume and enough opportunities to do so.More specifically,impor-

tant economic factors include retailing and price structures,the supply oflabeled goods,aggregate

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective309

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

demand for products, and affluence (Koos 2012; Thøgersen 2010). Country-level afflue

proxy for level of economic development and is important in influencing many other as

tion’s economic structure.Moreover,affluence raises the financialposition ofall households in a

country relative to similarly positioned households in less-affluent countries,thereby increasing the

freedom people have with which to make purchasing decisions.Politicalcharacteristics are believed

to influence how citizens engage in politicaland civic life by institutionally encouraging some typ

of engagement and discouraging others.For instance,polities with strong,centralized states discour-

ageassociation membership relativeto less“statist”politicalsystems(Schoferand Fourcade-

Gourinchas2001).Importantpoliticalfactorsfor ethicalconsumerism include the institutional

characteristics of the state,the character of associational life in a country,the nature of regulation rel-

evant to ethicalconsumerism,and the levelof state-involvement in labeling schemes (Koos 2012

Thøgersen 2010). Globalization has also been included in previous studies in political, eand

cultural varieties and is thought to increase ethical consumerism since it is often theori

ing conventional political institutions (Koos 2012).

Cultures of consumption and production vary across region and country and these cu

patterns ofethicalconsumption.For instance,the purchase oflabeled products may be depressed

around the Mediterranean in part because of the historicalfocus on the protection of localand au-

thentic cuisines instead of organic or fair trade consumption (Grasseni2003; Sassatelliand Davolio

2010; Sassatelli and Scott 2001). Shared norms and values at the contextual level,such as postmateri-

alism or buying green,also influence patterns of ethicalconsumerism at the individuallevelby en-

couraging compliance and imposing sanctions on norm violators.For example,the poor are often

stigmatized for eating “fast food” and shamed for their eating habits (Guthman 2007).Lastly,macro-

level social capital is important in influencing individual patterns of ethical consumerismIndividuals

in high-socialcapitalsocieties are more likely to ethically consume because they have great

to information and more motivation to act as a result of access to more trusting and int

networks. Neilson and Pamela Paxton (2010) find that regional-level generalized trust i

itively associated with ethical consumerism.

I N T E R A C T I O N S B E T W E E N I N D I V I D U A L - L E V E L A N D

C O U N T R Y - L E V E L V A R I A B L E S

Because socialcontext powerfully shapes patterns of ethicalconsumerism even among the relatively

homogenous countries of Europe,the introduction of non-European countries could mean subs

tial differences in the explanatory significance of individual-level predictors.Studies so far have unani-

mously confirmed the positive association between education and ethical consumerismbut there is a

wide variety of educationalsystems around the world (Clark 1986).Does the finding for education

hold up when non-Western and poor countries are included? The same could be asked

lightof variation in gendernorms(Hunter,Hatch,and Johnson 2004;Iversen and Rosenbluth

2006), or for any of the other individual-level variables.

Unfortunately,there are currently more questions than answers or even articulated hyp

Existing accounts of ethicalconsumerism imply the presence of interaction effects,but infrequently

elaborate expectations with any specificity.Veronika A.Andorfer (2013),in advocating theoretical

synthesis through a macro-micro-macro model (Coleman 1990),highlights the need for “bridge the-

ories” to specify how macro contexts influence micro behavior.The most developed expectations for

interaction that exist in the literature come from the “low-cost hypothesis,” an influent

of rational choice theory that focuses rather specifically on values and attitudes.

The foundation of the low-cost hypothesis is a rational choice model of human behav

with the premise that people are utility maximizers and that they make decisions based

costs of actions (Liebe and Preisendo¨rfer 2010).In short,people choose behaviors that yield them

the greatestutility atthe lowestcost.This “narrow” understanding ofhuman behavior has been

310 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

proxy for level of economic development and is important in influencing many other as

tion’s economic structure.Moreover,affluence raises the financialposition ofall households in a

country relative to similarly positioned households in less-affluent countries,thereby increasing the

freedom people have with which to make purchasing decisions.Politicalcharacteristics are believed

to influence how citizens engage in politicaland civic life by institutionally encouraging some typ

of engagement and discouraging others.For instance,polities with strong,centralized states discour-

ageassociation membership relativeto less“statist”politicalsystems(Schoferand Fourcade-

Gourinchas2001).Importantpoliticalfactorsfor ethicalconsumerism include the institutional

characteristics of the state,the character of associational life in a country,the nature of regulation rel-

evant to ethicalconsumerism,and the levelof state-involvement in labeling schemes (Koos 2012

Thøgersen 2010). Globalization has also been included in previous studies in political, eand

cultural varieties and is thought to increase ethical consumerism since it is often theori

ing conventional political institutions (Koos 2012).

Cultures of consumption and production vary across region and country and these cu

patterns ofethicalconsumption.For instance,the purchase oflabeled products may be depressed

around the Mediterranean in part because of the historicalfocus on the protection of localand au-

thentic cuisines instead of organic or fair trade consumption (Grasseni2003; Sassatelliand Davolio

2010; Sassatelli and Scott 2001). Shared norms and values at the contextual level,such as postmateri-

alism or buying green,also influence patterns of ethicalconsumerism at the individuallevelby en-

couraging compliance and imposing sanctions on norm violators.For example,the poor are often

stigmatized for eating “fast food” and shamed for their eating habits (Guthman 2007).Lastly,macro-

level social capital is important in influencing individual patterns of ethical consumerismIndividuals

in high-socialcapitalsocieties are more likely to ethically consume because they have great

to information and more motivation to act as a result of access to more trusting and int

networks. Neilson and Pamela Paxton (2010) find that regional-level generalized trust i

itively associated with ethical consumerism.

I N T E R A C T I O N S B E T W E E N I N D I V I D U A L - L E V E L A N D

C O U N T R Y - L E V E L V A R I A B L E S

Because socialcontext powerfully shapes patterns of ethicalconsumerism even among the relatively

homogenous countries of Europe,the introduction of non-European countries could mean subs

tial differences in the explanatory significance of individual-level predictors.Studies so far have unani-

mously confirmed the positive association between education and ethical consumerismbut there is a

wide variety of educationalsystems around the world (Clark 1986).Does the finding for education

hold up when non-Western and poor countries are included? The same could be asked

lightof variation in gendernorms(Hunter,Hatch,and Johnson 2004;Iversen and Rosenbluth

2006), or for any of the other individual-level variables.

Unfortunately,there are currently more questions than answers or even articulated hyp

Existing accounts of ethicalconsumerism imply the presence of interaction effects,but infrequently

elaborate expectations with any specificity.Veronika A.Andorfer (2013),in advocating theoretical

synthesis through a macro-micro-macro model (Coleman 1990),highlights the need for “bridge the-

ories” to specify how macro contexts influence micro behavior.The most developed expectations for

interaction that exist in the literature come from the “low-cost hypothesis,” an influent

of rational choice theory that focuses rather specifically on values and attitudes.

The foundation of the low-cost hypothesis is a rational choice model of human behav

with the premise that people are utility maximizers and that they make decisions based

costs of actions (Liebe and Preisendo¨rfer 2010).In short,people choose behaviors that yield them

the greatestutility atthe lowestcost.This “narrow” understanding ofhuman behavior has been

310 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

augmented by “wider” models,which add cultural and social variables to the economic formal

narrow accounts.With respect to low-cost approaches,these additions have come mostly in a focus

on how supra-individual contexts raise and lower the costs of behaviors and,thus,constitute a “struc-

ture of opportunity” for individual action (Ro¨ssel 2008) and “boundary conditions” for

of attitudes and values on behavior (Guagnano, Stern, and Dietz 1995).

According to this model,as externalcontexts raise the costs of a behavior,individual-levelvalues

and attitudes become less important in explaining that behavior; only in low-cost situa

matter.In very high-cost situations,in fact,economic considerations become “dominant decision

teria” (Diekmann and Preisendo¨rfer 2003:446) and “psychological characteristics” of

come almost irrelevant . . . Economics becomes essentially autonomous” (Schons, Resand Wieseke

2010:126).In low-cost situations that represent little threat to an individual’s material we“it

is easierfor actorsto transform theirattitudesinto corresponding behavior”(Diekmann and

Preisendo¨rfer 2003:443).Evidence in support of the low-cost hypothesis has been found in li

research (Ro¨ssel2008),studies ofenvironmentalconcern (Diekmann and Preisendo¨rfer 2003),in-

cluding recycling behavior (Derksen and Gartrell 1993; Guagnano,Stern,and Dietz 1995),criminol-

ogy (Kroneberg,Heintze,and Mehlkop 2010),and in experimentalgame scenarios involving real

money in high stakes situations (Schons etal.2010).With respectto ethicalconsumerism,Koos

(2012) finds that self-transcendence values,which are closely related to postmaterialist values,are

more influential in low-cost contexts, as expected.

Low-cost theories lead to the following hypothesis: The influence of individual-level a

values willbe greater in low-cost (high-affluence) countries.In other words,there willbe a positive

interaction effect between individual-level attitudes and values and country-level afflu

There is less guidance for what to expect in the way of interactions between countryafflu-

ence and other individual-levelvariables such as gender or education.The low-cost hypothesis does

not clearly specify how individual-leveldemographic characteristics or resources might interact

contextual costs,beyond the general sense that very high-cost contexts reduce all non-eco

siderations to insignificance.Linda Derksen and John Gartrell’s (1993) study of recycling beha

Alberta,Canada,providesa partialexception to this.Working from a broader,and lesssocial-

psychological,understanding of the low-cost approach,they argue that social contexts raise or lowe

the effort that individuals need to expend to engage in specific behaviors and that ind

iables other than attitudes and values might also become more influentialin low-cost situations as a

result.As such,they expected to find interaction effects between age,education,income,and job

prestige with belonging to a blue-box household (their low-cost condition),even though multicolli-

nearity prevented them from testing all of their expectations.

Moving beyond the low-costhypothesis,studies have examined cross-levelinteractions between

contextualopportunity structures and non-electoralpoliticalparticipation (Braun and Hutter 2014;

Marien et al. 2010; Vrablıkova 2013) and attempts at general, multilevel, theoretical in

cently been made (Barrett and Brunton-Smith 2014).However,ethical consumerism has not been in-

cluded in these studies in a significant way.Indeed,Katerina Vrablıkova (2013:10) explicitly mentio

the lack of theoreticalexpectations for ethicalconsumerism as a reason for not including ethicalcon-

sumerism measures in her cross-levelanalyses.In addition to providing an expanded test of the low

cost hypothesis,then,this study willprovide a broad exploratory analysis of the interactions be

individual-level predictors of ethical consumerism and country-level affluence and, thethe first test

of whether the individual-levelmodelof ethicalconsumerism developed in the West is generaliza

outside of that context. The theoretical implications of these findings are discussed in

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The InternationalSocialSurvey Program’s (ISSP) 2004 citizenship module supplies the indiv

leveldata for this study.The ISSP is one of the largest (totalN ¼ 52,550 across 38 countries) and

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective311

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

narrow accounts.With respect to low-cost approaches,these additions have come mostly in a focus

on how supra-individual contexts raise and lower the costs of behaviors and,thus,constitute a “struc-

ture of opportunity” for individual action (Ro¨ssel 2008) and “boundary conditions” for

of attitudes and values on behavior (Guagnano, Stern, and Dietz 1995).

According to this model,as externalcontexts raise the costs of a behavior,individual-levelvalues

and attitudes become less important in explaining that behavior; only in low-cost situa

matter.In very high-cost situations,in fact,economic considerations become “dominant decision

teria” (Diekmann and Preisendo¨rfer 2003:446) and “psychological characteristics” of

come almost irrelevant . . . Economics becomes essentially autonomous” (Schons, Resand Wieseke

2010:126).In low-cost situations that represent little threat to an individual’s material we“it

is easierfor actorsto transform theirattitudesinto corresponding behavior”(Diekmann and

Preisendo¨rfer 2003:443).Evidence in support of the low-cost hypothesis has been found in li

research (Ro¨ssel2008),studies ofenvironmentalconcern (Diekmann and Preisendo¨rfer 2003),in-

cluding recycling behavior (Derksen and Gartrell 1993; Guagnano,Stern,and Dietz 1995),criminol-

ogy (Kroneberg,Heintze,and Mehlkop 2010),and in experimentalgame scenarios involving real

money in high stakes situations (Schons etal.2010).With respectto ethicalconsumerism,Koos

(2012) finds that self-transcendence values,which are closely related to postmaterialist values,are

more influential in low-cost contexts, as expected.

Low-cost theories lead to the following hypothesis: The influence of individual-level a

values willbe greater in low-cost (high-affluence) countries.In other words,there willbe a positive

interaction effect between individual-level attitudes and values and country-level afflu

There is less guidance for what to expect in the way of interactions between countryafflu-

ence and other individual-levelvariables such as gender or education.The low-cost hypothesis does

not clearly specify how individual-leveldemographic characteristics or resources might interact

contextual costs,beyond the general sense that very high-cost contexts reduce all non-eco

siderations to insignificance.Linda Derksen and John Gartrell’s (1993) study of recycling beha

Alberta,Canada,providesa partialexception to this.Working from a broader,and lesssocial-

psychological,understanding of the low-cost approach,they argue that social contexts raise or lowe

the effort that individuals need to expend to engage in specific behaviors and that ind

iables other than attitudes and values might also become more influentialin low-cost situations as a

result.As such,they expected to find interaction effects between age,education,income,and job

prestige with belonging to a blue-box household (their low-cost condition),even though multicolli-

nearity prevented them from testing all of their expectations.

Moving beyond the low-costhypothesis,studies have examined cross-levelinteractions between

contextualopportunity structures and non-electoralpoliticalparticipation (Braun and Hutter 2014;

Marien et al. 2010; Vrablıkova 2013) and attempts at general, multilevel, theoretical in

cently been made (Barrett and Brunton-Smith 2014).However,ethical consumerism has not been in-

cluded in these studies in a significant way.Indeed,Katerina Vrablıkova (2013:10) explicitly mentio

the lack of theoreticalexpectations for ethicalconsumerism as a reason for not including ethicalcon-

sumerism measures in her cross-levelanalyses.In addition to providing an expanded test of the low

cost hypothesis,then,this study willprovide a broad exploratory analysis of the interactions be

individual-level predictors of ethical consumerism and country-level affluence and, thethe first test

of whether the individual-levelmodelof ethicalconsumerism developed in the West is generaliza

outside of that context. The theoretical implications of these findings are discussed in

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The InternationalSocialSurvey Program’s (ISSP) 2004 citizenship module supplies the indiv

leveldata for this study.The ISSP is one of the largest (totalN ¼ 52,550 across 38 countries) and

Ethical Consumerism in Global Perspective311

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

You're viewing a preview

Unlock full access by subscribing today!

most respected sources of data for performing cross-nationalanalyses,especially when non-Western

nations are of interest.As of 2004,more than a dozen non-Western countries supplied data to

ISSP,including countries in Eastern Europe,Asia,and Latin America.This allows for the analysis of

individual-level data from a much wider array of countries than previously studied by sc

cal consumerism.All models presented in the text were run using data from 36 countries w

estimation sample of N ¼ 37,408,with 29 percent missing data.See Figure 1 for a list of the coun-

tries included in the final estimation sample.Taiwan is presented in Figure 1 for illustrative purpos

but is not included in final analyses because of missing data on country-level measuresKey analyses

were also run after using several strategies to reduce missing data, including running m

forming multiple imputation of missing values using chained equations; results were ro

strategies.Also included in my analyses are country-level measures obtained from severaIn

addition to specifications discussed in the text,alternative specifications were tested for most var

ables. Results were robust to specification unless otherwise noted.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable used in this study is a self-reported measure ofethicalconsumerism.The

measure comes from a series of questions about political participation that begin with t

Here are some different forms of political and social action that people can take.Please indicate,

for each one,whether you: (1) Have done it in the past year; (2) Have done it in the mor

tant past; (3) Have not done it but might do it; and (4) Have not done it and would ne

The wording of the ethical consumerism item is “Boycotted,or deliberately bought,certain products

for political,ethicalor environmentalreasons” (ISSP 2004).Categories (1) and (2) were collapsed

to create a dichotomized measure with people that report any history of ethical consum

as 1 and those that have not ethically consumed coded as 0.

This measure contains both boycotting and buycotting and,thus,is conceptualized as a general

“ethicalization” of marketplace decisions.Although there is some evidence that boycotting and bu

ting are distinct enough from one another to be motivated by a different set of factors

Neilson 2010;Yates 2011) severalstudies analyze dependent variables that combine the two (

and Fraile 2006; Neilson and Paxton 2010; Stolle et al.2005; Stolle and Micheletti 2013) and there ar

methodological and theoretical reasons to question strong arguments for their separati

Theoretically,Monroe Friedman (1996,1999) has argued that boycotting and buycotting are

ten two sides of the same coin,something that even those that argue for treating them separa

knowledge (Neilson 2010:218).For instance,Friedman (1999) discusses efforts by labor unions t

encourage people to purchase products with a union label.Implicit in those efforts is a rejection,or

boycott,of products without the label.Often the designation of a decision or behavior as boycot

or buycotting comes down to a point of emphasis. As he says:

Thus, for example, a proposed consumer boycott by Americans of Japanese goods m

fined as a consumer buycott of American goods,the change of emphasis from the negative to

the positive reassures Americans that they are being asked to act patriotically rather

vinistically (p. 445).

Similarly,the decision of where to purchase lunch might involve a simultaneous rejection

tized fast food in favor of the deliberate purchase of “good” food supplied by the local f

(Guthman 2008; Johnston,Szabo,and Rodney 2011).It is not clear whether such behavior should

be classified as boycotting,buycotting,or both.Furthermore,and perhaps more to the point,it is not

clear how people responding to survey questions think such behavior should be categoIt is

clear, though, that such behavior is an “ethicalization” of market behavior.

312 Summers

by guest on September 6, 2016http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

nations are of interest.As of 2004,more than a dozen non-Western countries supplied data to