Facilitators and Barriers to Minority Blood Donation: A Review

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/17

|9

|8509

|482

Report

AI Summary

This systematic review, published in Nursing Research, examines the facilitators and barriers to blood donation within minority populations in the United States. The study, conducted using various electronic databases, employed a meta-synthesis approach to analyze 15 articles and identify key themes. The findings highlight the complex interplay of factors influencing donation, including the impact of knowing a blood recipient, cultural and religious affiliations, and medical mistrust. The review emphasizes the need for community education and communication to rebuild trust and address the underrepresentation of minorities among blood donors, particularly crucial for individuals with sickle cell disease and thalassemia. The research recommends strategies to increase blood donations within minority communities.

Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/nursingresearchonline by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3gDUFDls0jtTXFtI0IpkQ2pXag2MXLaJbefcaPVF5JxI= on 10/17/2019

Facilitators and Barriers to Minority

Blood Donations

A Systematic Review

Regena Spratling ▼ Raymona H. Lawrence

Background: Minority blood donations have historically been low in the United States; however, increasing the prop

minority blood donations is essential to reducing blood transfusion complications—particularly in African American

cell disease and thalassemia.

Objectives: The research question was as follows: What are the facilitators and barriers to blood donation in minori

Methods: Beginning August 2017, we conducted a literature search using the following electronic databases: CINAH

Full Text, Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological Collection, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Diss

and Theses, and PubMed, which continued through December 2017. Based on primarily descriptive data in the art

(n = 15), the systematic review proceeded as a meta-synthesis. An inductive approach was used to analyze comm

differences, patterns, and themes in the study findings; interpret the findings; and synthesize the findings to gener

knowledge about the phenomena of study.

Results: The themes included (a) knowing a blood recipient; (b) identifying with culture, race/ethnicity, and religiou

and (c) medical mistrust and misunderstanding. All were prominent in the descriptions of minorities on blood dona

as facilitators and barriers.

Discussion: The reviewed studies demonstrated that facilitators and barriers to minority blood donations are comp

concurrently. Community education and communication about blood donation have a positive effect on fellow com

members, including friends and family, in racial and ethnic minorities that are underrepresented among blood don

further suggest the need to rebuild trust among minority communities.

Key Words: blood donors minority groups qualitative research systematic review

Nursing Research, May/June 2019, Vol 68, No 3, 218–226

Minority blood donations have historically been low

in the United States (Yazer et al., 2017). Increasing

the proportion ofminority blood donations is

essential to reducing blood transfusion complications, par-

ticularly in individuals with sickle celldisease (SCD) and

thalassemia, for several reasons (Yazer et al., 2017). First, SCD

and thalassemia disproportionately affect minority racial and

ethnic populations in the United States. For example, SCD

occurs in about 1 in every 500 African American (AA) births,

1 in every 36,000 Hispanic-American births, and 1 in every

100,000 Caucasian births (Hassell,2010).Thalassemia is

prevalent in populations with roots in the Mediterranean,

Middle East,Indian subcontinent,Southeast Asia, and China

(Li, 2017). Second, blood from donors—with similar backg

as the recipients—is more likely to be a close match (Frye

et al., 2014). Unmatched blood can cause potentially seve

transfusion complications. Therefore, there is a critical nee

for blood donations from minorities to improve transfusion

outcomes in minority populations.

Individuals with hemoglobin disorders often need

transfusions—sometimes chronically and sometimes inter

mittently. If exposed to unmatched donor blood, the risk is

alloimmunization: the development of antibodies to the fo

eign red blood cellantigens (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016).Increasing blood donations among minorities can

ensure better access to minor antigen-matched units; how

ever,strategies for promoting donation in these popula-

tions require awareness ofthe unique characteristics of

minority groups and blood donation,as wellas programs

that address facilitators and barriers to minority blood don

tion (Charbonneau & Daigneault, 2016; Frye et al., 2014).

Regena Spratling, PhD, RN, APRN, CPNP, is Associate Professor and Associate

Dean & Chief Academic Officer for Nursing, Georgia State University, School

of Nursing, Byrdine F. Lewis College of Nursing & Health Professions, Atlanta.

Raymona H. Lawrence, DrPH, MPH, MCHES, is Associate Professor, Georgia

Southern University, Jiann Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Community

Health Behavior and Education, Statesboro.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License 4.0 (CCBY-

NC-ND), where it is permissible to download and share the work provided it

is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commer-

cially without permission from the journal.

Copyright © 2019 The Authors. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

DOI: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000355

218 www.nursingresearchonline.com Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3

Facilitators and Barriers to Minority

Blood Donations

A Systematic Review

Regena Spratling ▼ Raymona H. Lawrence

Background: Minority blood donations have historically been low in the United States; however, increasing the prop

minority blood donations is essential to reducing blood transfusion complications—particularly in African American

cell disease and thalassemia.

Objectives: The research question was as follows: What are the facilitators and barriers to blood donation in minori

Methods: Beginning August 2017, we conducted a literature search using the following electronic databases: CINAH

Full Text, Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological Collection, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Diss

and Theses, and PubMed, which continued through December 2017. Based on primarily descriptive data in the art

(n = 15), the systematic review proceeded as a meta-synthesis. An inductive approach was used to analyze comm

differences, patterns, and themes in the study findings; interpret the findings; and synthesize the findings to gener

knowledge about the phenomena of study.

Results: The themes included (a) knowing a blood recipient; (b) identifying with culture, race/ethnicity, and religiou

and (c) medical mistrust and misunderstanding. All were prominent in the descriptions of minorities on blood dona

as facilitators and barriers.

Discussion: The reviewed studies demonstrated that facilitators and barriers to minority blood donations are comp

concurrently. Community education and communication about blood donation have a positive effect on fellow com

members, including friends and family, in racial and ethnic minorities that are underrepresented among blood don

further suggest the need to rebuild trust among minority communities.

Key Words: blood donors minority groups qualitative research systematic review

Nursing Research, May/June 2019, Vol 68, No 3, 218–226

Minority blood donations have historically been low

in the United States (Yazer et al., 2017). Increasing

the proportion ofminority blood donations is

essential to reducing blood transfusion complications, par-

ticularly in individuals with sickle celldisease (SCD) and

thalassemia, for several reasons (Yazer et al., 2017). First, SCD

and thalassemia disproportionately affect minority racial and

ethnic populations in the United States. For example, SCD

occurs in about 1 in every 500 African American (AA) births,

1 in every 36,000 Hispanic-American births, and 1 in every

100,000 Caucasian births (Hassell,2010).Thalassemia is

prevalent in populations with roots in the Mediterranean,

Middle East,Indian subcontinent,Southeast Asia, and China

(Li, 2017). Second, blood from donors—with similar backg

as the recipients—is more likely to be a close match (Frye

et al., 2014). Unmatched blood can cause potentially seve

transfusion complications. Therefore, there is a critical nee

for blood donations from minorities to improve transfusion

outcomes in minority populations.

Individuals with hemoglobin disorders often need

transfusions—sometimes chronically and sometimes inter

mittently. If exposed to unmatched donor blood, the risk is

alloimmunization: the development of antibodies to the fo

eign red blood cellantigens (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016).Increasing blood donations among minorities can

ensure better access to minor antigen-matched units; how

ever,strategies for promoting donation in these popula-

tions require awareness ofthe unique characteristics of

minority groups and blood donation,as wellas programs

that address facilitators and barriers to minority blood don

tion (Charbonneau & Daigneault, 2016; Frye et al., 2014).

Regena Spratling, PhD, RN, APRN, CPNP, is Associate Professor and Associate

Dean & Chief Academic Officer for Nursing, Georgia State University, School

of Nursing, Byrdine F. Lewis College of Nursing & Health Professions, Atlanta.

Raymona H. Lawrence, DrPH, MPH, MCHES, is Associate Professor, Georgia

Southern University, Jiann Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Community

Health Behavior and Education, Statesboro.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License 4.0 (CCBY-

NC-ND), where it is permissible to download and share the work provided it

is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commer-

cially without permission from the journal.

Copyright © 2019 The Authors. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

DOI: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000355

218 www.nursingresearchonline.com Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

goals of this systematic review are to expand the knowledge of

facilitators and barriers to minority blood donation and to

recommend strategies thatwill increase blood donations

within minority communities.

Blood transfusions increase hemoglobin levels,increase

blood flow, improve oxygen delivery to the tissues, and dilute

the abnormal red blood cells containing sickled hemoglobin,

thus increasing the number of circulating normalred blood

cells (Estcourt, Fortin, Hopewell, Trivella, & Wang, 2017). Phe-

notypic incompatibility in blood transfusions results in the de-

velopment of antibodies over time that attack red blood cells,

making subsequent transfusions less effective and increasing the

risk of transfusion complications (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016). These antibodies to antigens, if present in subsequently

transfused blood, will trigger a dangerous hemolytic transfusion

reaction when transfused red blood cells are destroyed by the

immune system (Estcourt et al., 2017).

Minority blood donors are essential for a diverse supply

of blood because they provide greateraccessto corre-

sponding phenotypes, often rare ones, required for individ-

uals with diseases such as SCD and thalassemia. However,

minorities are historically underrepresented among blood

donors. In the United States, an estimated 11% to 21% of blood

donations are from minority populations based on the National

Blood Collection & Utilization Survey 2011 (U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services,2011).More recent surveys

from eight blood centers in 17 states noted decreasing blood

donations overall and a continued underrepresentation of mi-

nority donors. For example, Black or AA donors constituted

approximately 5% of alldonors from 2006 to 2015 (Yazer

et al., 2017). A decreased proportion of minority blood donors

has also been reported in Canada (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016) and France (Grassineau et al., 2007).

Increasing minority blood donations is a complex public

health issue with several barriers to minority blood donations.

Minorities have reported higher deferralrates and lack of

awareness about the process of blood donation (Frye et al.,

2014). Less than 1% of all donors experience events such as

fainting and fatigue (U.S.Department of Health and Human

Services, 2011); however, despite a relatively low occurrence

of adverse events, fear of these events is a commonly reported

barrier to blood donation among minority populations (Shaz,

Demmons, Hillyer, Jones, & Hillyer, 2009). Barriers to blood

donation also include defermentdue to low hemoglobin,

consisting of almost half (48%) of all deferrals from all poten-

tialdonors in the United States (U.S.Department of Health

and Human Services, 2011). Mobile blood drives remain the

major source (66%) of blood collections in the United States

(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). These

blood drives often recruit minority populations in the commu-

nity, at local churches, and other gatherings, yet a substantial

or sustainable increase in donations from these blood drives

has not been found (Yazer et al., 2017).

The current knowledge on facilitators and barriers to

nority blood donations is limited. Systematic reviews on

donations and blood donors exist,although none address

blood donation issues specific to minorities and none rev

the race/ethnicity of study samples (Bagot, Murray, & Ma

2016; Bednall, Bove, Cheetham, & Murray, 2013; Godin,

Im, Bélanger-Gravel, & Amireault, 2012). In addition, Bed

et al. (2013) reviewed blood donation behavior and inten

and cited the need for research with minorities as they o

port additional barriers to blood donation. The purposes o

systematic review are to examine the facilitators and bar

minority blood donations and recommend strategies to in

donations in the community. Therefore, the following res

question was asked:Whatare the facilitators and barriers to

blood donation in minority populations?

METHODS

Search Strategy

Prior to beginning the systematic review, the principal in

gator (PI) conducted a preliminary search to ensure the a

sence of similar reviews and gain understanding of existi

literature on minority blood donations. We consulted exp

on systematic review and meta-analyses: a librarian with

tise in nursing and health literature and experts on mino

blood donation and blood transfusion complications asso

ated with the hemoglobinopathies of SCD and thalassem

on search approach and terminology and goals of the rev

The systematic review proceeded using Preferred Report

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, and th

search question served as basis for identification,selection,

and appraisal of studies and collection and analysis of da

reviewed studies (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 200

The literature search began in August 2017 using the

tronic databases CINAHL Plus With Full Text, Academic S

Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological Collection,

Cochrane Library,ProQuest Dissertation and Theses,and

PubMed. Search alerts were also initiated for databases t

continued the search through December 2017. There we

no restrictions on publication year, publication type, or a

type. The keywords used in the search included combina

of the following words: blood donation, blood donor, mino

ity, AA, Black, race and ethnicity, and Hispanic or Latino.

The search databases and search combinations are prese

in Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were (a) data-based studies that sample

nority blood donors and minority blood donations or inclu

minorities in description of blood donor samples; (b) data

minority participants on process of blood donation;and (c)

English language. Exclusion criteria were (a) data-based

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 219

facilitators and barriers to minority blood donation and to

recommend strategies thatwill increase blood donations

within minority communities.

Blood transfusions increase hemoglobin levels,increase

blood flow, improve oxygen delivery to the tissues, and dilute

the abnormal red blood cells containing sickled hemoglobin,

thus increasing the number of circulating normalred blood

cells (Estcourt, Fortin, Hopewell, Trivella, & Wang, 2017). Phe-

notypic incompatibility in blood transfusions results in the de-

velopment of antibodies over time that attack red blood cells,

making subsequent transfusions less effective and increasing the

risk of transfusion complications (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016). These antibodies to antigens, if present in subsequently

transfused blood, will trigger a dangerous hemolytic transfusion

reaction when transfused red blood cells are destroyed by the

immune system (Estcourt et al., 2017).

Minority blood donors are essential for a diverse supply

of blood because they provide greateraccessto corre-

sponding phenotypes, often rare ones, required for individ-

uals with diseases such as SCD and thalassemia. However,

minorities are historically underrepresented among blood

donors. In the United States, an estimated 11% to 21% of blood

donations are from minority populations based on the National

Blood Collection & Utilization Survey 2011 (U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services,2011).More recent surveys

from eight blood centers in 17 states noted decreasing blood

donations overall and a continued underrepresentation of mi-

nority donors. For example, Black or AA donors constituted

approximately 5% of alldonors from 2006 to 2015 (Yazer

et al., 2017). A decreased proportion of minority blood donors

has also been reported in Canada (Charbonneau & Daigneault,

2016) and France (Grassineau et al., 2007).

Increasing minority blood donations is a complex public

health issue with several barriers to minority blood donations.

Minorities have reported higher deferralrates and lack of

awareness about the process of blood donation (Frye et al.,

2014). Less than 1% of all donors experience events such as

fainting and fatigue (U.S.Department of Health and Human

Services, 2011); however, despite a relatively low occurrence

of adverse events, fear of these events is a commonly reported

barrier to blood donation among minority populations (Shaz,

Demmons, Hillyer, Jones, & Hillyer, 2009). Barriers to blood

donation also include defermentdue to low hemoglobin,

consisting of almost half (48%) of all deferrals from all poten-

tialdonors in the United States (U.S.Department of Health

and Human Services, 2011). Mobile blood drives remain the

major source (66%) of blood collections in the United States

(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). These

blood drives often recruit minority populations in the commu-

nity, at local churches, and other gatherings, yet a substantial

or sustainable increase in donations from these blood drives

has not been found (Yazer et al., 2017).

The current knowledge on facilitators and barriers to

nority blood donations is limited. Systematic reviews on

donations and blood donors exist,although none address

blood donation issues specific to minorities and none rev

the race/ethnicity of study samples (Bagot, Murray, & Ma

2016; Bednall, Bove, Cheetham, & Murray, 2013; Godin,

Im, Bélanger-Gravel, & Amireault, 2012). In addition, Bed

et al. (2013) reviewed blood donation behavior and inten

and cited the need for research with minorities as they o

port additional barriers to blood donation. The purposes o

systematic review are to examine the facilitators and bar

minority blood donations and recommend strategies to in

donations in the community. Therefore, the following res

question was asked:Whatare the facilitators and barriers to

blood donation in minority populations?

METHODS

Search Strategy

Prior to beginning the systematic review, the principal in

gator (PI) conducted a preliminary search to ensure the a

sence of similar reviews and gain understanding of existi

literature on minority blood donations. We consulted exp

on systematic review and meta-analyses: a librarian with

tise in nursing and health literature and experts on mino

blood donation and blood transfusion complications asso

ated with the hemoglobinopathies of SCD and thalassem

on search approach and terminology and goals of the rev

The systematic review proceeded using Preferred Report

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, and th

search question served as basis for identification,selection,

and appraisal of studies and collection and analysis of da

reviewed studies (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 200

The literature search began in August 2017 using the

tronic databases CINAHL Plus With Full Text, Academic S

Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological Collection,

Cochrane Library,ProQuest Dissertation and Theses,and

PubMed. Search alerts were also initiated for databases t

continued the search through December 2017. There we

no restrictions on publication year, publication type, or a

type. The keywords used in the search included combina

of the following words: blood donation, blood donor, mino

ity, AA, Black, race and ethnicity, and Hispanic or Latino.

The search databases and search combinations are prese

in Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were (a) data-based studies that sample

nority blood donors and minority blood donations or inclu

minorities in description of blood donor samples; (b) data

minority participants on process of blood donation;and (c)

English language. Exclusion criteria were (a) data-based

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 219

on blood donation using blood center or national survey data

and (b) methodologicaland theoreticalstudies.In addition,

in multiple data-based reports of a single study sample, only

one sample was reported with data from each study analyzed.

The title and abstract of each article in the search pool

(n = 1,352) were carefully reviewed by the PI. Initial review fo-

cused on removal of duplicate articles and exclusion of articles

obviously not relevant to search terms (e.g.,animalstudies,

etc.). The resulting pool (n = 545) was further refined by ex-

cluding articles that focused on viral and bacterial infections,

genetic components of bloods, and risk for alloimmunization.

Articles originating from countries outside of the United States

were retained as long as the abstracts were in English. Detailed

review of abstracts excluded summary reports, historicalre-

views, literature reviews, editorials, periodicals, or news briefs

and articles that were not data based.

The remaining 42 full-text articles were reviewed in their

entirety. Of the articles reviewed, 18 articles contained demo-

graphic data from blood centers or “blood banks” and national

surveys.Some articles reported data from blood centers re-

garding the effectiveness of an intervention or program; how-

ever, the data were not linked to participants (e.g., an increase

in blood donations in a blood center was attributed to a pro-

gram without data to indicate that donors were engaged or

participated in program). We excluded articles that focused

on blood centers without data from minority blood donors

on donations.

Of the 24 remaining articles, 5 were qualitative studies, 2

were mixed methods, and 17 were quantitative descriptive.

Eight of the quantitative descriptive articles included qualita-

tive data and descriptions from participants, while 9 contained

quantitative data only.Statisticalmethods are relevantto a

meta-analysis to integrate the results of studies—particularly

intervention studies (Moher et al., 2009). Based on the pri-

marily descriptive data from the articles and the lack of interven-

tion studies, the systematic review proceeded as a descriptive

meta-synthesis (Finfgeld,2003),focusing on the facilitators

and barriers to blood donation in minority populations with

15 articles.

Meta-synthesis is the qualitative aggregation and interpre-

tation of descriptive findings that have been abstracted from

study findings (Finfgeld-Connett,2010).Similar to a meta-

analysis, a meta-synthesis includes a purpose, research ques-

tion, inclusion criteria,study and sample characteristics,

and qualitative data collection and data analysis technique

(Sherwood, 1999). A meta-synthesis examines a broad ph

nomenon (Finfgeld, 2003), such as facilitators and barriers

to blood donations in minority populations.

Data Abstraction

Data were abstracted from 15 articles in the following cate

gories: study design and data analysis methods, sample s

participant race/ethnicity and gender, donor type (nondon

or experienced donor), geographic location (United States

or other country), and community location (e.g., communi

church,college,etc.).Narratives from participants,themes,

and strategies presented were abstracted from the finding

cussions, and conclusions.

Data Analysis

An inductive approach was used to analyze commonalities

ferences,patterns,and themes in study findings;interpret the

findings; and synthesize the findings to generate new kno

about the phenomena of study (Finfgeld, 2003; Paterson,

The findings were categorized and later collapsed into the

(Finfgeld-Connett, 2010). The steps of the thematic analys

cluded (a) translating the findings of each study into them

(b) comparing and contrasting the themes by identifying s

ilarities and differences among themes, and (c) determinin

the key themes and hypothesizing how themes relate to e

other (Paterson, 2001).

In the analysis, each study was reviewed by the PI, and

themes were validated by the PI and the research team w

a total of three members (Paterson, 2001). The research t

had expertise with minority blood donations, minority pop

lations with SCD and thalassemia,research with minorities,

and qualitative methods. Sampling and data analysis deci

were recorded in field notes and an audit trail, and consen

on decisions was achieved among the research team (Finf

Connett, 2010; Paterson, 2001).

RESULTS

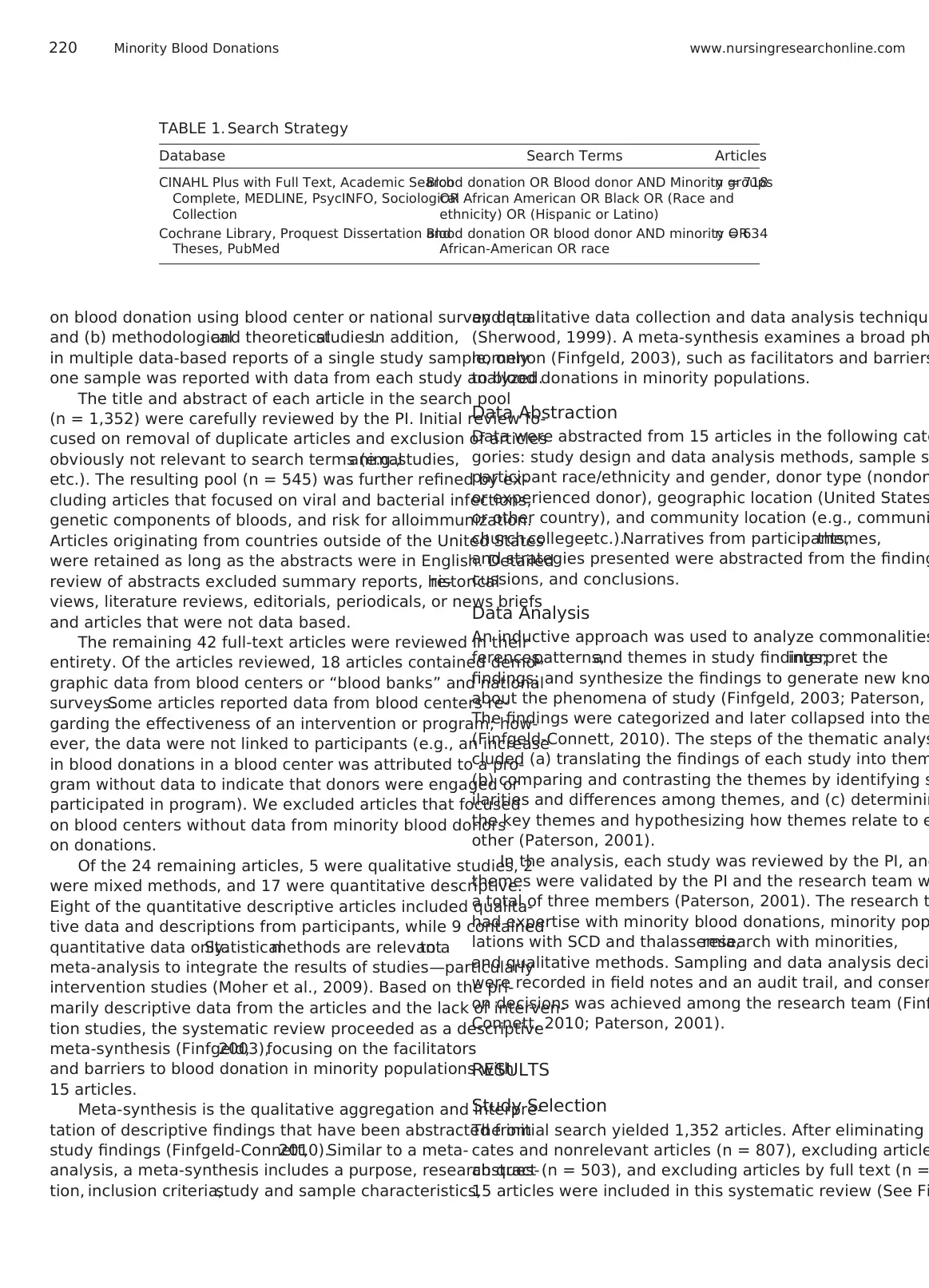

Study Selection

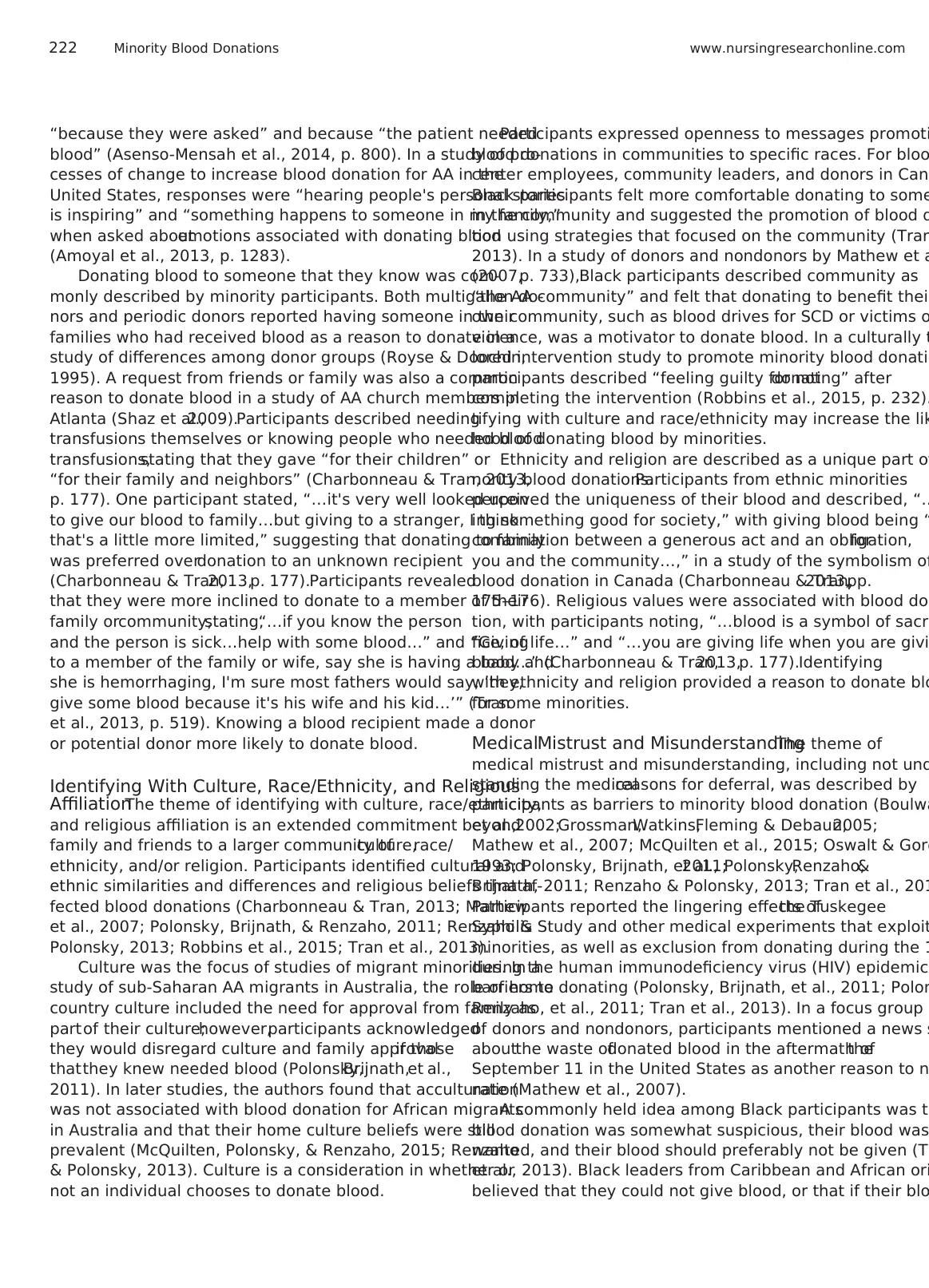

The initial search yielded 1,352 articles. After eliminating

cates and nonrelevant articles (n = 807), excluding article

abstract (n = 503), and excluding articles by full text (n =

15 articles were included in this systematic review (See Fi

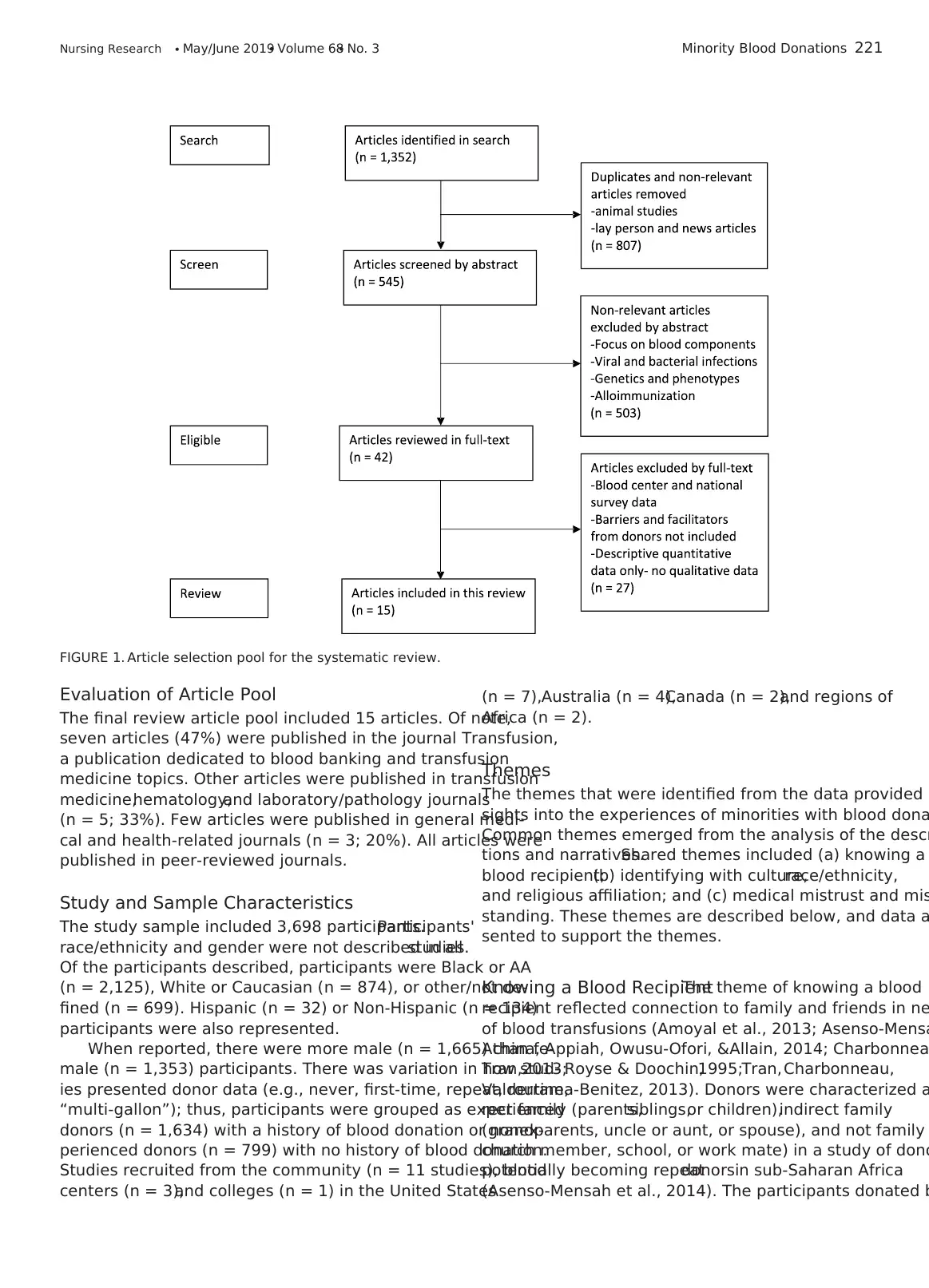

TABLE 1. Search Strategy

Database Search Terms Articles

CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Academic Search

Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological

Collection

Blood donation OR Blood donor AND Minority groups

OR African American OR Black OR (Race and

ethnicity) OR (Hispanic or Latino)

n = 718

Cochrane Library, Proquest Dissertation and

Theses, PubMed

Blood donation OR blood donor AND minority OR

African-American OR race

n = 634

220 Minority Blood Donations www.nursingresearchonline.com

and (b) methodologicaland theoreticalstudies.In addition,

in multiple data-based reports of a single study sample, only

one sample was reported with data from each study analyzed.

The title and abstract of each article in the search pool

(n = 1,352) were carefully reviewed by the PI. Initial review fo-

cused on removal of duplicate articles and exclusion of articles

obviously not relevant to search terms (e.g.,animalstudies,

etc.). The resulting pool (n = 545) was further refined by ex-

cluding articles that focused on viral and bacterial infections,

genetic components of bloods, and risk for alloimmunization.

Articles originating from countries outside of the United States

were retained as long as the abstracts were in English. Detailed

review of abstracts excluded summary reports, historicalre-

views, literature reviews, editorials, periodicals, or news briefs

and articles that were not data based.

The remaining 42 full-text articles were reviewed in their

entirety. Of the articles reviewed, 18 articles contained demo-

graphic data from blood centers or “blood banks” and national

surveys.Some articles reported data from blood centers re-

garding the effectiveness of an intervention or program; how-

ever, the data were not linked to participants (e.g., an increase

in blood donations in a blood center was attributed to a pro-

gram without data to indicate that donors were engaged or

participated in program). We excluded articles that focused

on blood centers without data from minority blood donors

on donations.

Of the 24 remaining articles, 5 were qualitative studies, 2

were mixed methods, and 17 were quantitative descriptive.

Eight of the quantitative descriptive articles included qualita-

tive data and descriptions from participants, while 9 contained

quantitative data only.Statisticalmethods are relevantto a

meta-analysis to integrate the results of studies—particularly

intervention studies (Moher et al., 2009). Based on the pri-

marily descriptive data from the articles and the lack of interven-

tion studies, the systematic review proceeded as a descriptive

meta-synthesis (Finfgeld,2003),focusing on the facilitators

and barriers to blood donation in minority populations with

15 articles.

Meta-synthesis is the qualitative aggregation and interpre-

tation of descriptive findings that have been abstracted from

study findings (Finfgeld-Connett,2010).Similar to a meta-

analysis, a meta-synthesis includes a purpose, research ques-

tion, inclusion criteria,study and sample characteristics,

and qualitative data collection and data analysis technique

(Sherwood, 1999). A meta-synthesis examines a broad ph

nomenon (Finfgeld, 2003), such as facilitators and barriers

to blood donations in minority populations.

Data Abstraction

Data were abstracted from 15 articles in the following cate

gories: study design and data analysis methods, sample s

participant race/ethnicity and gender, donor type (nondon

or experienced donor), geographic location (United States

or other country), and community location (e.g., communi

church,college,etc.).Narratives from participants,themes,

and strategies presented were abstracted from the finding

cussions, and conclusions.

Data Analysis

An inductive approach was used to analyze commonalities

ferences,patterns,and themes in study findings;interpret the

findings; and synthesize the findings to generate new kno

about the phenomena of study (Finfgeld, 2003; Paterson,

The findings were categorized and later collapsed into the

(Finfgeld-Connett, 2010). The steps of the thematic analys

cluded (a) translating the findings of each study into them

(b) comparing and contrasting the themes by identifying s

ilarities and differences among themes, and (c) determinin

the key themes and hypothesizing how themes relate to e

other (Paterson, 2001).

In the analysis, each study was reviewed by the PI, and

themes were validated by the PI and the research team w

a total of three members (Paterson, 2001). The research t

had expertise with minority blood donations, minority pop

lations with SCD and thalassemia,research with minorities,

and qualitative methods. Sampling and data analysis deci

were recorded in field notes and an audit trail, and consen

on decisions was achieved among the research team (Finf

Connett, 2010; Paterson, 2001).

RESULTS

Study Selection

The initial search yielded 1,352 articles. After eliminating

cates and nonrelevant articles (n = 807), excluding article

abstract (n = 503), and excluding articles by full text (n =

15 articles were included in this systematic review (See Fi

TABLE 1. Search Strategy

Database Search Terms Articles

CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Academic Search

Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Sociological

Collection

Blood donation OR Blood donor AND Minority groups

OR African American OR Black OR (Race and

ethnicity) OR (Hispanic or Latino)

n = 718

Cochrane Library, Proquest Dissertation and

Theses, PubMed

Blood donation OR blood donor AND minority OR

African-American OR race

n = 634

220 Minority Blood Donations www.nursingresearchonline.com

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Evaluation of Article Pool

The final review article pool included 15 articles. Of note,

seven articles (47%) were published in the journal Transfusion,

a publication dedicated to blood banking and transfusion

medicine topics. Other articles were published in transfusion

medicine,hematology,and laboratory/pathology journals

(n = 5; 33%). Few articles were published in general medi-

cal and health-related journals (n = 3; 20%). All articles were

published in peer-reviewed journals.

Study and Sample Characteristics

The study sample included 3,698 participants.Participants'

race/ethnicity and gender were not described in allstudies.

Of the participants described, participants were Black or AA

(n = 2,125), White or Caucasian (n = 874), or other/not de-

fined (n = 699). Hispanic (n = 32) or Non-Hispanic (n = 134)

participants were also represented.

When reported, there were more male (n = 1,665) than fe-

male (n = 1,353) participants. There was variation in how stud-

ies presented donor data (e.g., never, first-time, repeat, routine,

“multi-gallon”); thus, participants were grouped as experienced

donors (n = 1,634) with a history of blood donation or nonex-

perienced donors (n = 799) with no history of blood donation.

Studies recruited from the community (n = 11 studies), blood

centers (n = 3),and colleges (n = 1) in the United States

(n = 7),Australia (n = 4),Canada (n = 2),and regions of

Africa (n = 2).

Themes

The themes that were identified from the data provided i

sights into the experiences of minorities with blood dona

Common themes emerged from the analysis of the descr

tions and narratives.Shared themes included (a) knowing a

blood recipient;(b) identifying with culture,race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation; and (c) medical mistrust and mis

standing. These themes are described below, and data a

sented to support the themes.

Knowing a Blood RecipientThe theme of knowing a blood

recipient reflected connection to family and friends in ne

of blood transfusions (Amoyal et al., 2013; Asenso-Mensa

Achina, Appiah, Owusu-Ofori, &Allain, 2014; Charbonnea

Tran,2013;Royse & Doochin,1995;Tran,Charbonneau,

Valderrama-Benitez, 2013). Donors were characterized a

rect family (parents,siblings,or children),indirect family

(grandparents, uncle or aunt, or spouse), and not family

church member, school, or work mate) in a study of dono

potentially becoming repeatdonorsin sub-Saharan Africa

(Asenso-Mensah et al., 2014). The participants donated b

FIGURE 1. Article selection pool for the systematic review.

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 221

The final review article pool included 15 articles. Of note,

seven articles (47%) were published in the journal Transfusion,

a publication dedicated to blood banking and transfusion

medicine topics. Other articles were published in transfusion

medicine,hematology,and laboratory/pathology journals

(n = 5; 33%). Few articles were published in general medi-

cal and health-related journals (n = 3; 20%). All articles were

published in peer-reviewed journals.

Study and Sample Characteristics

The study sample included 3,698 participants.Participants'

race/ethnicity and gender were not described in allstudies.

Of the participants described, participants were Black or AA

(n = 2,125), White or Caucasian (n = 874), or other/not de-

fined (n = 699). Hispanic (n = 32) or Non-Hispanic (n = 134)

participants were also represented.

When reported, there were more male (n = 1,665) than fe-

male (n = 1,353) participants. There was variation in how stud-

ies presented donor data (e.g., never, first-time, repeat, routine,

“multi-gallon”); thus, participants were grouped as experienced

donors (n = 1,634) with a history of blood donation or nonex-

perienced donors (n = 799) with no history of blood donation.

Studies recruited from the community (n = 11 studies), blood

centers (n = 3),and colleges (n = 1) in the United States

(n = 7),Australia (n = 4),Canada (n = 2),and regions of

Africa (n = 2).

Themes

The themes that were identified from the data provided i

sights into the experiences of minorities with blood dona

Common themes emerged from the analysis of the descr

tions and narratives.Shared themes included (a) knowing a

blood recipient;(b) identifying with culture,race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation; and (c) medical mistrust and mis

standing. These themes are described below, and data a

sented to support the themes.

Knowing a Blood RecipientThe theme of knowing a blood

recipient reflected connection to family and friends in ne

of blood transfusions (Amoyal et al., 2013; Asenso-Mensa

Achina, Appiah, Owusu-Ofori, &Allain, 2014; Charbonnea

Tran,2013;Royse & Doochin,1995;Tran,Charbonneau,

Valderrama-Benitez, 2013). Donors were characterized a

rect family (parents,siblings,or children),indirect family

(grandparents, uncle or aunt, or spouse), and not family

church member, school, or work mate) in a study of dono

potentially becoming repeatdonorsin sub-Saharan Africa

(Asenso-Mensah et al., 2014). The participants donated b

FIGURE 1. Article selection pool for the systematic review.

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 221

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

“because they were asked” and because “the patient needed

blood” (Asenso-Mensah et al., 2014, p. 800). In a study of pro-

cesses of change to increase blood donation for AA in the

United States, responses were “hearing people's personal stories

is inspiring” and “something happens to someone in my family,”

when asked aboutemotions associated with donating blood

(Amoyal et al., 2013, p. 1283).

Donating blood to someone that they know was com-

monly described by minority participants. Both multigallon do-

nors and periodic donors reported having someone in their

families who had received blood as a reason to donate in a

study of differences among donor groups (Royse & Doochin,

1995). A request from friends or family was also a common

reason to donate blood in a study of AA church members in

Atlanta (Shaz et al.,2009).Participants described needing

transfusions themselves or knowing people who needed blood

transfusions,stating that they gave “for their children” or

“for their family and neighbors” (Charbonneau & Tran, 2013,

p. 177). One participant stated, “…it's very well looked upon

to give our blood to family…but giving to a stranger, I think

that's a little more limited,” suggesting that donating to family

was preferred overdonation to an unknown recipient

(Charbonneau & Tran,2013,p. 177).Participants revealed

that they were more inclined to donate to a member of their

family orcommunity,stating,“…if you know the person

and the person is sick…help with some blood…” and “Giving

to a member of the family or wife, say she is having a baby and

she is hemorrhaging, I'm sure most fathers would say, ‘hey,

give some blood because it's his wife and his kid…’” (Tran

et al., 2013, p. 519). Knowing a blood recipient made a donor

or potential donor more likely to donate blood.

Identifying With Culture, Race/Ethnicity, and Religious

AffiliationThe theme of identifying with culture, race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation is an extended commitment beyond

family and friends to a larger community ofculture,race/

ethnicity, and/or religion. Participants identified cultural and

ethnic similarities and differences and religious beliefs that af-

fected blood donations (Charbonneau & Tran, 2013; Mathew

et al., 2007; Polonsky, Brijnath, & Renzaho, 2011; Renzaho &

Polonsky, 2013; Robbins et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2013).

Culture was the focus of studies of migrant minorities. In a

study of sub-Saharan AA migrants in Australia, the role of home

country culture included the need for approval from family as

partof their culture;however,participants acknowledged

they would disregard culture and family approvalif those

thatthey knew needed blood (Polonsky,Brijnath,et al.,

2011). In later studies, the authors found that acculturation

was not associated with blood donation for African migrants

in Australia and that their home culture beliefs were still

prevalent (McQuilten, Polonsky, & Renzaho, 2015; Renzaho

& Polonsky, 2013). Culture is a consideration in whether or

not an individual chooses to donate blood.

Participants expressed openness to messages promoti

blood donations in communities to specific races. For bloo

center employees, community leaders, and donors in Can

Black participants felt more comfortable donating to some

in the community and suggested the promotion of blood d

tion using strategies that focused on the community (Tran

2013). In a study of donors and nondonors by Mathew et a

(2007,p. 733),Black participants described community as

“the AA community” and felt that donating to benefit their

own community, such as blood drives for SCD or victims o

violence, was a motivator to donate blood. In a culturally t

lored intervention study to promote minority blood donatio

participants described “feeling guilty for notdonating” after

completing the intervention (Robbins et al., 2015, p. 232).

tifying with culture and race/ethnicity may increase the lik

hood of donating blood by minorities.

Ethnicity and religion are described as a unique part of

nority blood donations.Participants from ethnic minorities

perceived the uniqueness of their blood and described, “…

ing something good for society,” with giving blood being “

combination between a generous act and an obligation,for

you and the community…,” in a study of the symbolism of

blood donation in Canada (Charbonneau & Tran,2013,pp.

175–176). Religious values were associated with blood don

tion, with participants noting, “…blood is a symbol of sacri

fice, of life…” and “…you are giving life when you are givi

blood…” (Charbonneau & Tran,2013,p. 177).Identifying

with ethnicity and religion provided a reason to donate blo

for some minorities.

MedicalMistrust and MisunderstandingThe theme of

medical mistrust and misunderstanding, including not und

standing the medicalreasons for deferral, was described by

participants as barriers to minority blood donation (Boulwa

et al.,2002;Grossman,Watkins,Fleming & Debaun,2005;

Mathew et al., 2007; McQuilten et al., 2015; Oswalt & Gord

1993; Polonsky, Brijnath, et al.,2011;Polonsky,Renzaho,&

Brijnath, 2011; Renzaho & Polonsky, 2013; Tran et al., 201

Participants reported the lingering effects ofthe Tuskegee

Syphilis Study and other medical experiments that exploit

minorities, as well as exclusion from donating during the 1

during the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic

barriers to donating (Polonsky, Brijnath, et al., 2011; Polon

Renzaho, et al., 2011; Tran et al., 2013). In a focus group s

of donors and nondonors, participants mentioned a news s

aboutthe waste ofdonated blood in the aftermath ofthe

September 11 in the United States as another reason to n

nate (Mathew et al., 2007).

A commonly held idea among Black participants was th

blood donation was somewhat suspicious, their blood was

wanted, and their blood should preferably not be given (Tr

et al., 2013). Black leaders from Caribbean and African ori

believed that they could not give blood, or that if their blo

222 Minority Blood Donations www.nursingresearchonline.com

blood” (Asenso-Mensah et al., 2014, p. 800). In a study of pro-

cesses of change to increase blood donation for AA in the

United States, responses were “hearing people's personal stories

is inspiring” and “something happens to someone in my family,”

when asked aboutemotions associated with donating blood

(Amoyal et al., 2013, p. 1283).

Donating blood to someone that they know was com-

monly described by minority participants. Both multigallon do-

nors and periodic donors reported having someone in their

families who had received blood as a reason to donate in a

study of differences among donor groups (Royse & Doochin,

1995). A request from friends or family was also a common

reason to donate blood in a study of AA church members in

Atlanta (Shaz et al.,2009).Participants described needing

transfusions themselves or knowing people who needed blood

transfusions,stating that they gave “for their children” or

“for their family and neighbors” (Charbonneau & Tran, 2013,

p. 177). One participant stated, “…it's very well looked upon

to give our blood to family…but giving to a stranger, I think

that's a little more limited,” suggesting that donating to family

was preferred overdonation to an unknown recipient

(Charbonneau & Tran,2013,p. 177).Participants revealed

that they were more inclined to donate to a member of their

family orcommunity,stating,“…if you know the person

and the person is sick…help with some blood…” and “Giving

to a member of the family or wife, say she is having a baby and

she is hemorrhaging, I'm sure most fathers would say, ‘hey,

give some blood because it's his wife and his kid…’” (Tran

et al., 2013, p. 519). Knowing a blood recipient made a donor

or potential donor more likely to donate blood.

Identifying With Culture, Race/Ethnicity, and Religious

AffiliationThe theme of identifying with culture, race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation is an extended commitment beyond

family and friends to a larger community ofculture,race/

ethnicity, and/or religion. Participants identified cultural and

ethnic similarities and differences and religious beliefs that af-

fected blood donations (Charbonneau & Tran, 2013; Mathew

et al., 2007; Polonsky, Brijnath, & Renzaho, 2011; Renzaho &

Polonsky, 2013; Robbins et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2013).

Culture was the focus of studies of migrant minorities. In a

study of sub-Saharan AA migrants in Australia, the role of home

country culture included the need for approval from family as

partof their culture;however,participants acknowledged

they would disregard culture and family approvalif those

thatthey knew needed blood (Polonsky,Brijnath,et al.,

2011). In later studies, the authors found that acculturation

was not associated with blood donation for African migrants

in Australia and that their home culture beliefs were still

prevalent (McQuilten, Polonsky, & Renzaho, 2015; Renzaho

& Polonsky, 2013). Culture is a consideration in whether or

not an individual chooses to donate blood.

Participants expressed openness to messages promoti

blood donations in communities to specific races. For bloo

center employees, community leaders, and donors in Can

Black participants felt more comfortable donating to some

in the community and suggested the promotion of blood d

tion using strategies that focused on the community (Tran

2013). In a study of donors and nondonors by Mathew et a

(2007,p. 733),Black participants described community as

“the AA community” and felt that donating to benefit their

own community, such as blood drives for SCD or victims o

violence, was a motivator to donate blood. In a culturally t

lored intervention study to promote minority blood donatio

participants described “feeling guilty for notdonating” after

completing the intervention (Robbins et al., 2015, p. 232).

tifying with culture and race/ethnicity may increase the lik

hood of donating blood by minorities.

Ethnicity and religion are described as a unique part of

nority blood donations.Participants from ethnic minorities

perceived the uniqueness of their blood and described, “…

ing something good for society,” with giving blood being “

combination between a generous act and an obligation,for

you and the community…,” in a study of the symbolism of

blood donation in Canada (Charbonneau & Tran,2013,pp.

175–176). Religious values were associated with blood don

tion, with participants noting, “…blood is a symbol of sacri

fice, of life…” and “…you are giving life when you are givi

blood…” (Charbonneau & Tran,2013,p. 177).Identifying

with ethnicity and religion provided a reason to donate blo

for some minorities.

MedicalMistrust and MisunderstandingThe theme of

medical mistrust and misunderstanding, including not und

standing the medicalreasons for deferral, was described by

participants as barriers to minority blood donation (Boulwa

et al.,2002;Grossman,Watkins,Fleming & Debaun,2005;

Mathew et al., 2007; McQuilten et al., 2015; Oswalt & Gord

1993; Polonsky, Brijnath, et al.,2011;Polonsky,Renzaho,&

Brijnath, 2011; Renzaho & Polonsky, 2013; Tran et al., 201

Participants reported the lingering effects ofthe Tuskegee

Syphilis Study and other medical experiments that exploit

minorities, as well as exclusion from donating during the 1

during the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic

barriers to donating (Polonsky, Brijnath, et al., 2011; Polon

Renzaho, et al., 2011; Tran et al., 2013). In a focus group s

of donors and nondonors, participants mentioned a news s

aboutthe waste ofdonated blood in the aftermath ofthe

September 11 in the United States as another reason to n

nate (Mathew et al., 2007).

A commonly held idea among Black participants was th

blood donation was somewhat suspicious, their blood was

wanted, and their blood should preferably not be given (Tr

et al., 2013). Black leaders from Caribbean and African ori

believed that they could not give blood, or that if their blo

222 Minority Blood Donations www.nursingresearchonline.com

donation was accepted,the blood would later be discarded

(Tran et al., 2013). Participants in Australia who were migrants

from sub-Saharan Africa also questioned whether their blood

was wanted and used (Polonsky, Brijnath, et al., 2011). Partic-

ipants felt that their blood would be excluded based on their

race and the perception thatthey have a disease,stating,

“You can give blood…but you're African, you can't, because

the people are afraid of you.You might have AIDS…” and

“They think you are HIV-positive so,as a result,you are

rejected outright. Even if you volunteer to go, they wouldn't

take you,they wouldn'tacceptit…” (Polonsky,Brijnath,

et al., 2011, p. 340; Polonsky, Renzaho et al., 2011, p. 1815).

In later studies,medicalmistrustwas negatively associated

with knowledge aboutblood donation (McQuilten etal.,

2015; Renzaho & Polonsky, 2013). Thus, medical mistrust is

an important barrier to minority blood donation.

Medicalmisunderstanding,including unclear explana-

tions to donors ofmedicalreasons for deferrals given by

healthcare providers, were cited as barriers to minority blood

donations.Lapsed donors incorrectly viewed themselves as

permanently deferred for temporary deferrals such as low

hemoglobin (Mathew et al., 2007). A participant in a study

of minorities in Canada described, “As a young adult, [she

was] refused without further explanations…was once more

rejected…the nurse took some time to explain her exclu-

sion…the nurse reminded [her] not to take this rejection per-

sonally, even pleading with her to attempt to donate at a later

date…” (Tran et al., 2013, p. 519). Participants reported being

deferred for reasons that were not made clear to them: “They

are supposed to spellout the characteristics of people that

can give blood,otherwise Iwill justgo and telleveryone,

‘You can't donate blood’…” which may result in misinforma-

tion in the community (Polonsky,Brijnath,et al., 2011,

p. 339). The existing medical mistrust, combined with misun-

derstanding by potential blood donors, reduces the likelihood

of minority blood donations.

DISCUSSION

The reviewed studies demonstrate that facilitators and barriers

to minority blood donations are complex and exist concur-

rently. Facilitators include knowing a blood recipient and iden-

tifying with culture,race/ethnicity,and religious affiliation.

Barriers include medical mistrust and misunderstanding. Strat-

egies can be developed from knowledge of these facilitators

and barriers to guide future research, education,and policy

on minority blood donations.

Knowing a blood recipient—most often family and friends—

was often the reason for minority donors to give blood. Donor

perspectives of knowing a recipient have been studied in liv-

ing kidney donors (Agerskov, Ludvigsen, Bistrup, & Pedersen,

2016). Kidney donations were primarily for family members.

Donors were very attentive to the needs of the recipients—

not just their own care after the procedure.Ultimately,the

donation led to a greater connection and perception of cl

ness between donor and recipient (Agerskov et al., 2016

strengthened relationship between donorsand recipients

may extend to minority blood donors and recipients.

The theme of knowing a blood recipient offers strateg

to facilitate minority blood donation through engagemen

family and friends. Minority blood donors verbalized that

were more likely to donate blood to someone they know

needed a blood transfusion. Thus, blood recipients may b

to accessing and engaging potentialdonors.Existing educa-

tional materials used for donors can be given to recipient

distribute to family and friends who may be potential don

Strategies that recruit recipients,and subsequently educate

and empower them to engage minority donors, can facili

minority blood donations.

Experiences ofidentifying with culture,race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation enhanced donation among donor

desiring to benefit the community and donors with simila

experiences and beliefs. In a review, culture and religion

fluenced whether ethnic minority women participated in

cervical cancer screening (Chan & So, 2017). Ethnicity an

ligion were successfully incorporated into health promoti

interventions for ethnic minority groups in a study of hea

researchers and promoters (Liu et al., 2016). Identifying

culture, race/ethnicity, and religious affiliation can influen

health behaviors and can promote minority blood donors

benefit the health of others.

As a theme, identifying with culture, race/ethnicity, a

religious affiliation provides insights for strategies that m

hance donation. Strategies that engage members of the

munity as champions or recruiters can be used to facilita

potential minority donors in the community. These cham

can be present at community events (e.g., health fairs, b

drives,and festivals) and community centers (e.g.,churches,

schools, and senior centers). In addition, similar to engag

blood recipients to recruitfamily and friends,community

champions can distribute educationalmaterials to other

potential minority blood donors.

Medical mistrust and misunderstanding deterred min

ties from donating blood. A systematic review of qualitat

studies highlighted fear of experimentation and intrusive

of screening methods as unique among AA men with colo

screening (Adams, Richmond, Corbie-Smith, & Powell, 20

Mistrust at the provider and organizationalleveldecreased

participation in screenings (Adams et al., 2017). Participa

were unsure of their decisions, needed guidance and sup

from healthcare providers, and expressed feelings of mis

standing, judgment, and medical abandonment in a syste

review of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver pe

tives on end-of-life care in chronic kidney disease (Tong

2014).Knowledge and guidance from trusted providers ar

necessary to encourage blood donations and enhance do

experiences for the future.

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 223

(Tran et al., 2013). Participants in Australia who were migrants

from sub-Saharan Africa also questioned whether their blood

was wanted and used (Polonsky, Brijnath, et al., 2011). Partic-

ipants felt that their blood would be excluded based on their

race and the perception thatthey have a disease,stating,

“You can give blood…but you're African, you can't, because

the people are afraid of you.You might have AIDS…” and

“They think you are HIV-positive so,as a result,you are

rejected outright. Even if you volunteer to go, they wouldn't

take you,they wouldn'tacceptit…” (Polonsky,Brijnath,

et al., 2011, p. 340; Polonsky, Renzaho et al., 2011, p. 1815).

In later studies,medicalmistrustwas negatively associated

with knowledge aboutblood donation (McQuilten etal.,

2015; Renzaho & Polonsky, 2013). Thus, medical mistrust is

an important barrier to minority blood donation.

Medicalmisunderstanding,including unclear explana-

tions to donors ofmedicalreasons for deferrals given by

healthcare providers, were cited as barriers to minority blood

donations.Lapsed donors incorrectly viewed themselves as

permanently deferred for temporary deferrals such as low

hemoglobin (Mathew et al., 2007). A participant in a study

of minorities in Canada described, “As a young adult, [she

was] refused without further explanations…was once more

rejected…the nurse took some time to explain her exclu-

sion…the nurse reminded [her] not to take this rejection per-

sonally, even pleading with her to attempt to donate at a later

date…” (Tran et al., 2013, p. 519). Participants reported being

deferred for reasons that were not made clear to them: “They

are supposed to spellout the characteristics of people that

can give blood,otherwise Iwill justgo and telleveryone,

‘You can't donate blood’…” which may result in misinforma-

tion in the community (Polonsky,Brijnath,et al., 2011,

p. 339). The existing medical mistrust, combined with misun-

derstanding by potential blood donors, reduces the likelihood

of minority blood donations.

DISCUSSION

The reviewed studies demonstrate that facilitators and barriers

to minority blood donations are complex and exist concur-

rently. Facilitators include knowing a blood recipient and iden-

tifying with culture,race/ethnicity,and religious affiliation.

Barriers include medical mistrust and misunderstanding. Strat-

egies can be developed from knowledge of these facilitators

and barriers to guide future research, education,and policy

on minority blood donations.

Knowing a blood recipient—most often family and friends—

was often the reason for minority donors to give blood. Donor

perspectives of knowing a recipient have been studied in liv-

ing kidney donors (Agerskov, Ludvigsen, Bistrup, & Pedersen,

2016). Kidney donations were primarily for family members.

Donors were very attentive to the needs of the recipients—

not just their own care after the procedure.Ultimately,the

donation led to a greater connection and perception of cl

ness between donor and recipient (Agerskov et al., 2016

strengthened relationship between donorsand recipients

may extend to minority blood donors and recipients.

The theme of knowing a blood recipient offers strateg

to facilitate minority blood donation through engagemen

family and friends. Minority blood donors verbalized that

were more likely to donate blood to someone they know

needed a blood transfusion. Thus, blood recipients may b

to accessing and engaging potentialdonors.Existing educa-

tional materials used for donors can be given to recipient

distribute to family and friends who may be potential don

Strategies that recruit recipients,and subsequently educate

and empower them to engage minority donors, can facili

minority blood donations.

Experiences ofidentifying with culture,race/ethnicity,

and religious affiliation enhanced donation among donor

desiring to benefit the community and donors with simila

experiences and beliefs. In a review, culture and religion

fluenced whether ethnic minority women participated in

cervical cancer screening (Chan & So, 2017). Ethnicity an

ligion were successfully incorporated into health promoti

interventions for ethnic minority groups in a study of hea

researchers and promoters (Liu et al., 2016). Identifying

culture, race/ethnicity, and religious affiliation can influen

health behaviors and can promote minority blood donors

benefit the health of others.

As a theme, identifying with culture, race/ethnicity, a

religious affiliation provides insights for strategies that m

hance donation. Strategies that engage members of the

munity as champions or recruiters can be used to facilita

potential minority donors in the community. These cham

can be present at community events (e.g., health fairs, b

drives,and festivals) and community centers (e.g.,churches,

schools, and senior centers). In addition, similar to engag

blood recipients to recruitfamily and friends,community

champions can distribute educationalmaterials to other

potential minority blood donors.

Medical mistrust and misunderstanding deterred min

ties from donating blood. A systematic review of qualitat

studies highlighted fear of experimentation and intrusive

of screening methods as unique among AA men with colo

screening (Adams, Richmond, Corbie-Smith, & Powell, 20

Mistrust at the provider and organizationalleveldecreased

participation in screenings (Adams et al., 2017). Participa

were unsure of their decisions, needed guidance and sup

from healthcare providers, and expressed feelings of mis

standing, judgment, and medical abandonment in a syste

review of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver pe

tives on end-of-life care in chronic kidney disease (Tong

2014).Knowledge and guidance from trusted providers ar

necessary to encourage blood donations and enhance do

experiences for the future.

Nursing Research • May/June 2019• Volume 68• No. 3 Minority Blood Donations 223

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The theme of medicalmistrust and misunderstanding

presents a significant, longstanding barrier for minority blood

donations; however, strategies that reduce this barrier and in-

crease trust and knowledge can increase donations. The direct

engagement of the community using educationalmaterials,

community educators, and addressing any lingering issues with

trust and previous experiences should be a routine strategy.

Participants described consistent issues and historicalevents.

These topics must be the focus of conversations with potential

donors. Blood recipients and champions in communities can

also increase trust and knowledge.

Recommendations for Research, Practice, Policy, and

Education

This study confirms the need for community education and

communication about blood donation and its positive effect

on fellow community members, including friends and family,

in racial and ethnic minorities that are underrepresented among

blood donors. It further suggests the need to rebuild trust among

minority communities.

Future research should include theory-based, quantitative,

and intervention studies in minority populations. The emerg-

ing use of theoretical frameworks shows promise in study de-

velopment and provides a basis for future studies for minority

blood donations.The TranstheoreticalModel(Prochaska &

DiClemente,1983) and Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen,

1991) are well-established theories thathave been used in

public health and other disciplines to describe an individual's

behavior. Both are suitable to study the behaviors of blood

donors, including minorities. Assimilation Theory (Gordon,

1964) and Culture Fusion Theory (Kramer, 2000) focus on

culture and are well-suited for studies with underrepresented

minority blood donors. In addition, studies on blood donors

and blood donations should include minority participants—

whether the study itself is focused on minorities—and data

should be presented to reflect any differences in minority

perceptions and outcomes. A single web-based intervention

study found in the review was conducted in the United States

(Robbins et al., 2015). There is a need for well-developed inter-

vention studies that focus on minority populations.

Blood donations are a specialized area of clinical practice

with specific approaches to donors and donation protocols.

Healthcare providers who do not practice in this area may have

limited knowledge of blood donation protocols and may be fur-

ther limited with no personal experience as a donor, therefore

limiting the ability to engage donors and promote donations

in minority populations.Meta-synthesis findings can lead to

the development of clinical protocols (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010),

and findings from this review emphasize the need for tai-

lored approaches and protocols for minority blood donors.

The findings from meta-synthesis studies can also facilitate

development of healthcare policy (Finfgeld-Connett,2010).

Policy on U.S. blood donations should focus on national efforts

to engage minority blood donors and use advocates and

stakeholders in the community to enhance grassroots effo

(Singleton & Spratling, 2018). Studies conducted outside o

United States primarily focused on blood donations among

grantminorities,racialand ethnic disparities,and barriers to

blood donations imposed on migrants.This illustrates the

need to address policies that affect the ability to donate b

by minorities.

Of note, this review found frequent recurrence of spec

authors and research teams,indicating that few researchers

are focusing on this much-needed area of research. In add

the majority of articles were published in journals focused

transfusions and blood disorders, leaving a knowledge gap

nursing, medical, public health, and other general health l

ature. Dissemination of knowledge on minority blood dono

and blood donations is needed in a variety of journals targ

many disciplines and healthcare providers.Lay information

should also be developed for and dispersed to potential do

and minority communities.

Limitations

This systematic review was limited by varied data and me

across studies. The authors adhered to rigorous data abstr

tion and analysis, but the variation in studies may have lim

the review. The focus of the review was studies on minorit

blood donations; however, there were studies that include

both minority and nonminority populations.The data pre-

sented from these studies may not have exclusively prese

or separated minority participant data.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review adds to the growing body of literat

on minority blood donations, expanding knowledge of faci

tors and barriers and recommending strategies to increase

nority blood donations in the community.Previous studies,

including systematic reviews, have presented isolated find

on minority blood donations. This systematic review and m

synthesis analyzed and summarized the findings from a sa

of descriptive studies to present overarching themes from

studies and subsequently present strategies to facilitate a

decrease barriers to minority blood donations.

Accepted for publication October 19, 2018.

The research reported in this publication was supported by Cooperati

Agreement 5 NU58 DD001138-03, funded by the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC). The content is solely the responsibility

the authors and do not necessarily represent the officialviews of the

CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

The authors would like to thank Ashley Singleton, MPH, research asso

the Georgia Health Policy Center at Georgia State University, for her a

and support of this work.

Corresponding author: Regena Spratling, PhD, RN, APRN, CPNP, Georg

State University School of Nursing, P.O. Box 4019, Atlanta, GA 30302-

(e-mail: rspratling@gsu.edu).

224 Minority Blood Donations www.nursingresearchonline.com

presents a significant, longstanding barrier for minority blood

donations; however, strategies that reduce this barrier and in-

crease trust and knowledge can increase donations. The direct

engagement of the community using educationalmaterials,

community educators, and addressing any lingering issues with

trust and previous experiences should be a routine strategy.

Participants described consistent issues and historicalevents.

These topics must be the focus of conversations with potential

donors. Blood recipients and champions in communities can

also increase trust and knowledge.

Recommendations for Research, Practice, Policy, and

Education

This study confirms the need for community education and

communication about blood donation and its positive effect

on fellow community members, including friends and family,

in racial and ethnic minorities that are underrepresented among

blood donors. It further suggests the need to rebuild trust among

minority communities.

Future research should include theory-based, quantitative,

and intervention studies in minority populations. The emerg-

ing use of theoretical frameworks shows promise in study de-

velopment and provides a basis for future studies for minority

blood donations.The TranstheoreticalModel(Prochaska &

DiClemente,1983) and Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen,

1991) are well-established theories thathave been used in

public health and other disciplines to describe an individual's

behavior. Both are suitable to study the behaviors of blood

donors, including minorities. Assimilation Theory (Gordon,

1964) and Culture Fusion Theory (Kramer, 2000) focus on

culture and are well-suited for studies with underrepresented

minority blood donors. In addition, studies on blood donors

and blood donations should include minority participants—

whether the study itself is focused on minorities—and data

should be presented to reflect any differences in minority

perceptions and outcomes. A single web-based intervention

study found in the review was conducted in the United States

(Robbins et al., 2015). There is a need for well-developed inter-

vention studies that focus on minority populations.

Blood donations are a specialized area of clinical practice

with specific approaches to donors and donation protocols.

Healthcare providers who do not practice in this area may have

limited knowledge of blood donation protocols and may be fur-

ther limited with no personal experience as a donor, therefore

limiting the ability to engage donors and promote donations

in minority populations.Meta-synthesis findings can lead to

the development of clinical protocols (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010),

and findings from this review emphasize the need for tai-

lored approaches and protocols for minority blood donors.

The findings from meta-synthesis studies can also facilitate

development of healthcare policy (Finfgeld-Connett,2010).

Policy on U.S. blood donations should focus on national efforts

to engage minority blood donors and use advocates and

stakeholders in the community to enhance grassroots effo

(Singleton & Spratling, 2018). Studies conducted outside o

United States primarily focused on blood donations among

grantminorities,racialand ethnic disparities,and barriers to

blood donations imposed on migrants.This illustrates the

need to address policies that affect the ability to donate b

by minorities.

Of note, this review found frequent recurrence of spec

authors and research teams,indicating that few researchers

are focusing on this much-needed area of research. In add

the majority of articles were published in journals focused

transfusions and blood disorders, leaving a knowledge gap

nursing, medical, public health, and other general health l

ature. Dissemination of knowledge on minority blood dono

and blood donations is needed in a variety of journals targ

many disciplines and healthcare providers.Lay information

should also be developed for and dispersed to potential do

and minority communities.

Limitations

This systematic review was limited by varied data and me

across studies. The authors adhered to rigorous data abstr

tion and analysis, but the variation in studies may have lim

the review. The focus of the review was studies on minorit

blood donations; however, there were studies that include

both minority and nonminority populations.The data pre-

sented from these studies may not have exclusively prese

or separated minority participant data.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review adds to the growing body of literat

on minority blood donations, expanding knowledge of faci

tors and barriers and recommending strategies to increase

nority blood donations in the community.Previous studies,

including systematic reviews, have presented isolated find

on minority blood donations. This systematic review and m