HIB2000 Criminology: Analyzing Fear of Crime via Newspaper Reports

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/13

|10

|2648

|214

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the correlation between fear of crime (FOC) and its primary source, newspaper reporting, drawing data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and other scholarly sources. It reviews literature on FOC, emphasizing that while reasonable fear can aid crime prevention, excessive fear can be counterproductive. The report includes a thematic analysis of qualitative data obtained through interviews with individuals from different demographics, focusing on their perceptions of crime and media influence. It also presents a qualitative analysis of Personal Value Crimes (PVC) reported in newspapers to measure fearfulness and sensationalism in reporting styles. The findings indicate that newspaper readership is related to FOC, independent of socioeconomic status, and that newspapers play a significant role in shaping public perception and fear of crime, often through sensationalized reporting. The study concludes that newspapers 'construct' the perception of crime, influencing public fear.

CRIMINOLOGY

INTRODUCTION

The Office of National Statistics (ONS), part of Home Affairs Portfolio is UK’s

national research and knowledge center on crime and justice. The data, research and

policy that reflects in this report have been based on information provided on ONS

website. The policy-relevant research conducted by ONS is of national significance and

is a reliable crime and justice evidence base. This report has also drawn data, both

qualitative and quantitative, from other sources including known scholars and

researchers who bring their viewpoint to the public through mainstream newspapers and

scholarly journals. Views expressed by the author of this report are largely influenced

by these sources and the main purpose of this report is to assess links between Fear of

Crime (FOC) and its most influential source – the newspaper.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Fear of crime (FOC) is a universal phenomenon and is considered as a problem in itself.

A recent Home Office directive notified that, and I quote - 'fear of crime will grow

unless checked. As an issue of social concern, it has to be taken as seriously as ... crime

prevention and reduction.' Unquote (Home Office, 1989: ii) (Williams & Dickinson,

1993). Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) has also argued that although

reasonable fears with relation to crime can be harnessed for fighting the looming threat

of crime, but, ONS emphasis that when such fears grow exponentially and become

unreasonable they tend to become counterproductive responses and create social

problems (Bosworth & Hoyle (ed), 2012). In this context, the research done by Paul

Williams and Julie Dickinson and reported in their research paper titled FEAR OF

CRIME: READ ALL ABOUT IT?: The Relationship between Newspaper Crime

Reporting and Fear of Crime, published in The British Journal of Criminology, Vol.33

No. 1, highlights the same allegation and fears which many other sources have been

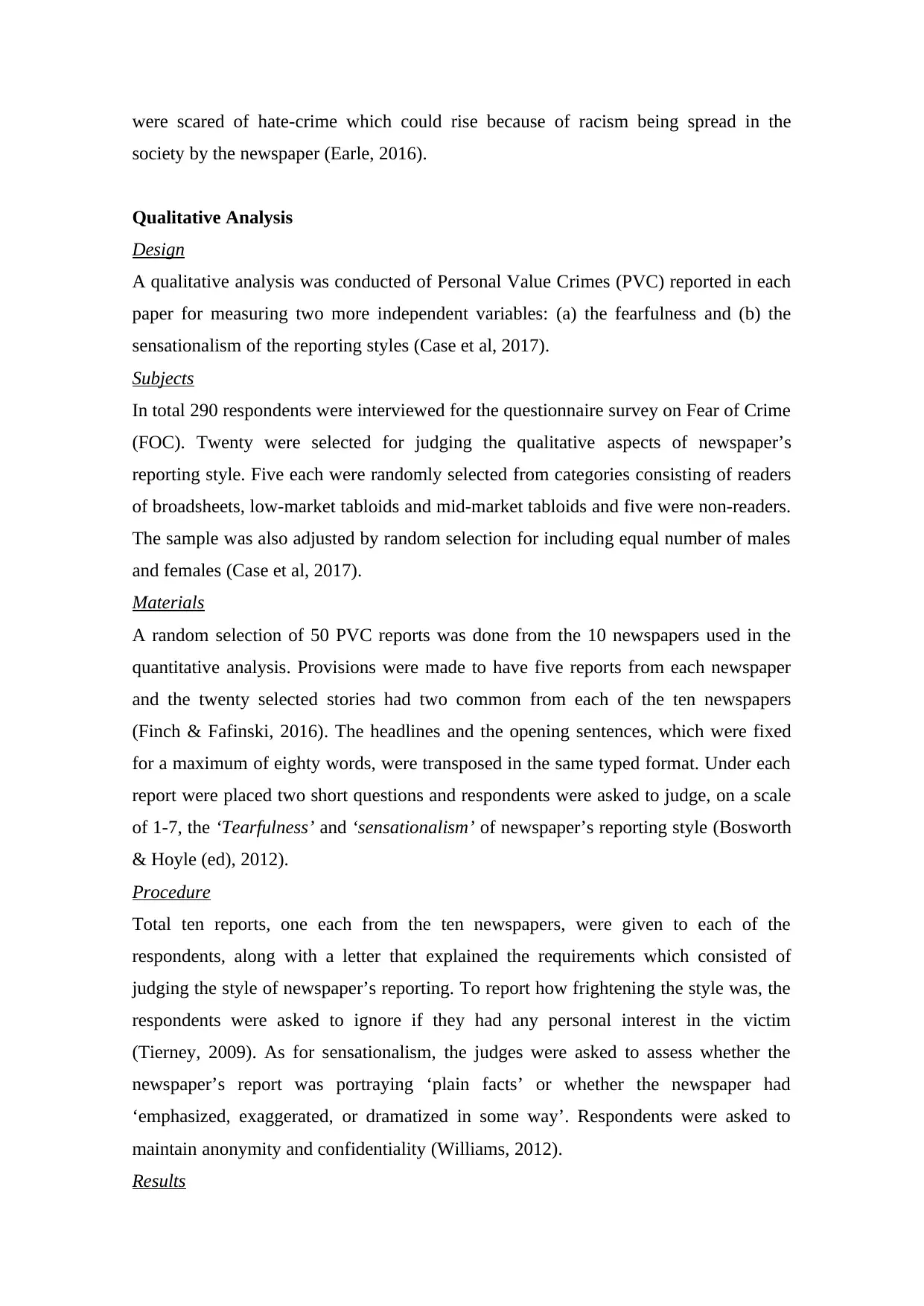

reporting. The fear of crime, including being a victim (See Figure-01 in Appendix), the

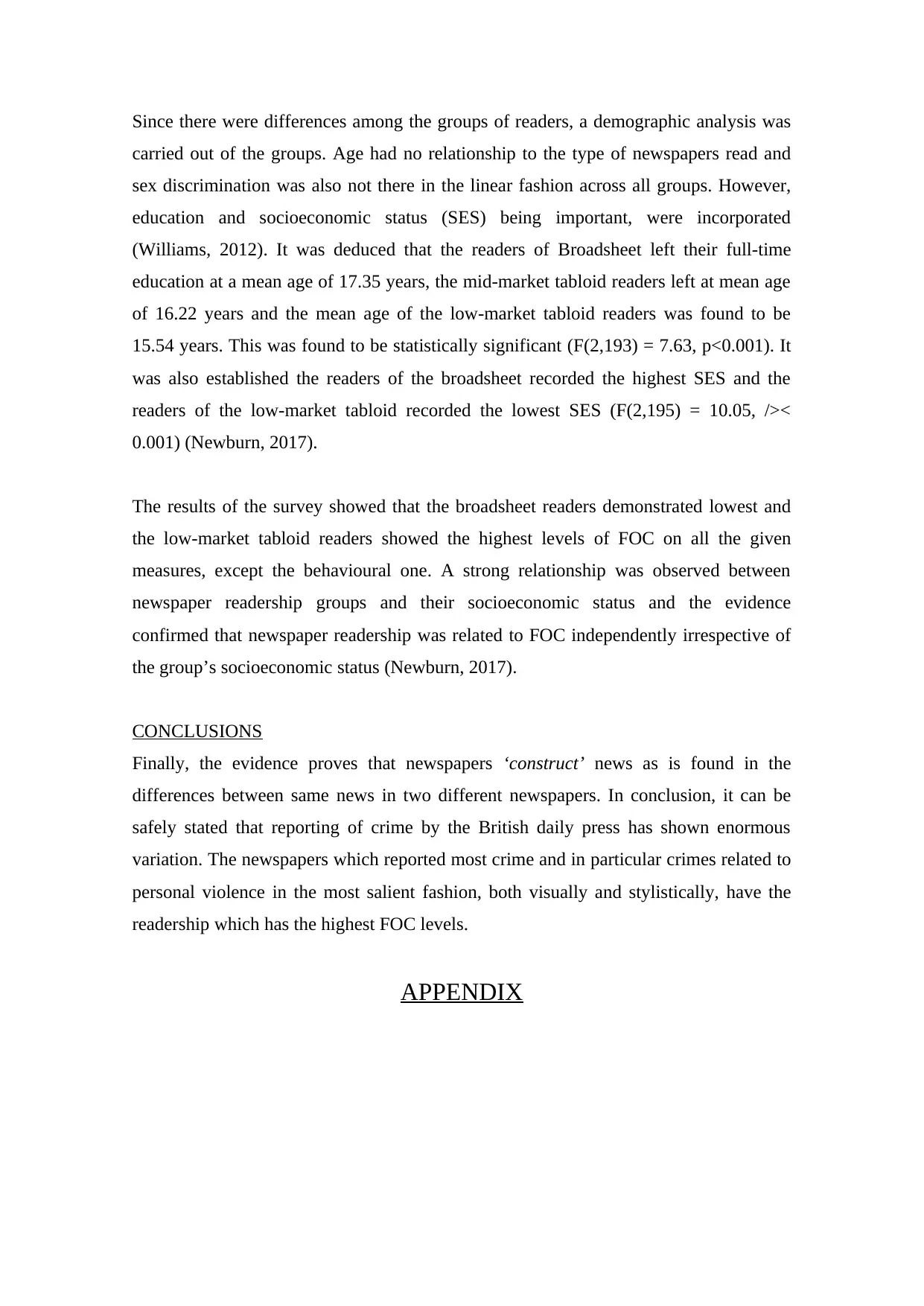

environmental characteristics such as living in an area having a high crime rate (See

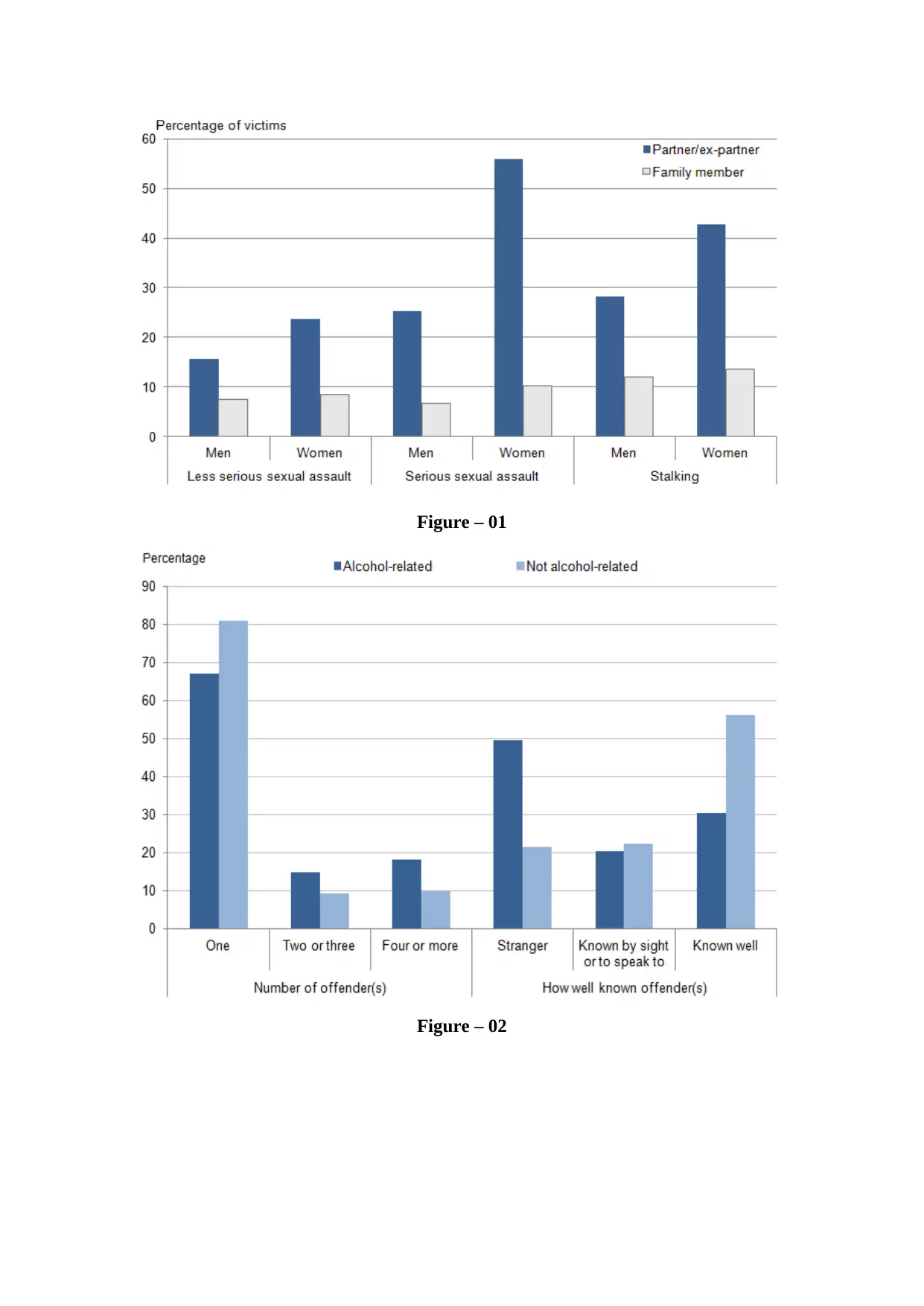

Figure-02 in Appendix) and their physical vulnerability (See Figure-03 in Appendix)

have been well established by Williams & Dickinson (Finch & Fafinski, 2016).

INTRODUCTION

The Office of National Statistics (ONS), part of Home Affairs Portfolio is UK’s

national research and knowledge center on crime and justice. The data, research and

policy that reflects in this report have been based on information provided on ONS

website. The policy-relevant research conducted by ONS is of national significance and

is a reliable crime and justice evidence base. This report has also drawn data, both

qualitative and quantitative, from other sources including known scholars and

researchers who bring their viewpoint to the public through mainstream newspapers and

scholarly journals. Views expressed by the author of this report are largely influenced

by these sources and the main purpose of this report is to assess links between Fear of

Crime (FOC) and its most influential source – the newspaper.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Fear of crime (FOC) is a universal phenomenon and is considered as a problem in itself.

A recent Home Office directive notified that, and I quote - 'fear of crime will grow

unless checked. As an issue of social concern, it has to be taken as seriously as ... crime

prevention and reduction.' Unquote (Home Office, 1989: ii) (Williams & Dickinson,

1993). Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) has also argued that although

reasonable fears with relation to crime can be harnessed for fighting the looming threat

of crime, but, ONS emphasis that when such fears grow exponentially and become

unreasonable they tend to become counterproductive responses and create social

problems (Bosworth & Hoyle (ed), 2012). In this context, the research done by Paul

Williams and Julie Dickinson and reported in their research paper titled FEAR OF

CRIME: READ ALL ABOUT IT?: The Relationship between Newspaper Crime

Reporting and Fear of Crime, published in The British Journal of Criminology, Vol.33

No. 1, highlights the same allegation and fears which many other sources have been

reporting. The fear of crime, including being a victim (See Figure-01 in Appendix), the

environmental characteristics such as living in an area having a high crime rate (See

Figure-02 in Appendix) and their physical vulnerability (See Figure-03 in Appendix)

have been well established by Williams & Dickinson (Finch & Fafinski, 2016).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

But there does exist the other category of people, those who have neither been the

victims and have never witnessed a crime in person. Why do these people get aggrieved

by the reported crimes? How do they experience the catastrophic Fear of Crime?

According to Williams and Dickinson, the perception of these individuals about the

‘crime problem' is based on the indirect sources (Barak, 2009). Williams and Dickinson

have also pointed to newspapers as the most influential indirect source and like many

other scholars referred to in their essay, hold this indirect source responsible for

creating this fear-psychosis in the society (Newburn, 2017). It is indeed the case with

every media, be it audio, audio-visual or print, they are sensationalising the incidents

without going into the merits of it and because the society is relies on them, they are

successful in building their viewership/readership (Earle, 2016).

THEMATIC ANALYSIS

Thematic analysis is considered as the most common form of analysis in qualitative

research. Its purpose is to emphasize examining, pinpointing and recording of patterns

or ‘themes’ within the data (Simpson, Harrison & Martin, 2012).

Main points

ONS data states that crime has fallen on long-term basis, but the short-term basis crimes

are more stable. These include less frequently occurring violent crimes and there figures

are –

22% increase in crimes involving knives or similar sharp instruments.

11% increase in crimes using firearms.

CSEW has also stated that most people do not come across any type of crime. During

the year ended December 2017, CSEW data showed that 8 out of 10 adults were never a

victim of any type of crime.

Overview of Crime

According to CSEW, crime covers a wide range of offences, including the most harmful

type as murder and rape and relatively minor incidents such as criminal damage or petty

theft. Crime is always a hidden phenomenon and the different type of offences occur

under different kind of circumstances, at different frequencies thus demonstrating that

crime cannot be measured in its entirety using a single source (Williams, 2012).

Quality and Methodology

The quarterly releases of CSEW/ONS about crimes taking place in England and Wales

are issued under the guidance of the Home Office. The National Statistics are produced

victims and have never witnessed a crime in person. Why do these people get aggrieved

by the reported crimes? How do they experience the catastrophic Fear of Crime?

According to Williams and Dickinson, the perception of these individuals about the

‘crime problem' is based on the indirect sources (Barak, 2009). Williams and Dickinson

have also pointed to newspapers as the most influential indirect source and like many

other scholars referred to in their essay, hold this indirect source responsible for

creating this fear-psychosis in the society (Newburn, 2017). It is indeed the case with

every media, be it audio, audio-visual or print, they are sensationalising the incidents

without going into the merits of it and because the society is relies on them, they are

successful in building their viewership/readership (Earle, 2016).

THEMATIC ANALYSIS

Thematic analysis is considered as the most common form of analysis in qualitative

research. Its purpose is to emphasize examining, pinpointing and recording of patterns

or ‘themes’ within the data (Simpson, Harrison & Martin, 2012).

Main points

ONS data states that crime has fallen on long-term basis, but the short-term basis crimes

are more stable. These include less frequently occurring violent crimes and there figures

are –

22% increase in crimes involving knives or similar sharp instruments.

11% increase in crimes using firearms.

CSEW has also stated that most people do not come across any type of crime. During

the year ended December 2017, CSEW data showed that 8 out of 10 adults were never a

victim of any type of crime.

Overview of Crime

According to CSEW, crime covers a wide range of offences, including the most harmful

type as murder and rape and relatively minor incidents such as criminal damage or petty

theft. Crime is always a hidden phenomenon and the different type of offences occur

under different kind of circumstances, at different frequencies thus demonstrating that

crime cannot be measured in its entirety using a single source (Williams, 2012).

Quality and Methodology

The quarterly releases of CSEW/ONS about crimes taking place in England and Wales

are issued under the guidance of the Home Office. The National Statistics are produced

keeping in practice the high professional standards set in the Code of Practice for

Statistics.

FINDINGS & DISCUSSION

Fear of Crime

An interview session with a common questionnaire was conducted with three people,

first being a female, ‘A’ aged 53, second being a male, ‘B’ aged 42 and third being a

female ‘C’ aged 45.

“Would you say that you are fearful of crime?” was the first question.

The female were more cautious when alone in a car park or if they were out after sunset

but then believed that it was fate which was more powerful than being cautious. The

male was echoing same sentiments but had a more pragmatic view of the situation in the

society of elderly people. His idea of safety was not to go to places where you do not

feel safe. However, both were fearful of the prevailing circumstances and the surge of

crime in the society. Another common agreement was about the media. Both agreed that

it was the newspapers which were getting judgemental about how people should live

and what they should do and what they should avoid doing (Bosworth & Hoyle (ed),

2012).

The second question was – “You mentioned the media above. Could you say some more

about that?”

The female were more critical of the media as they believed that media has no right to

dictate to the women in the society. Their point was valid when they raised the question

– why does it have to be women only who have to be careful? Why don’t men behave in

a civilized manner? Why the blame always rests with the women in the society? The

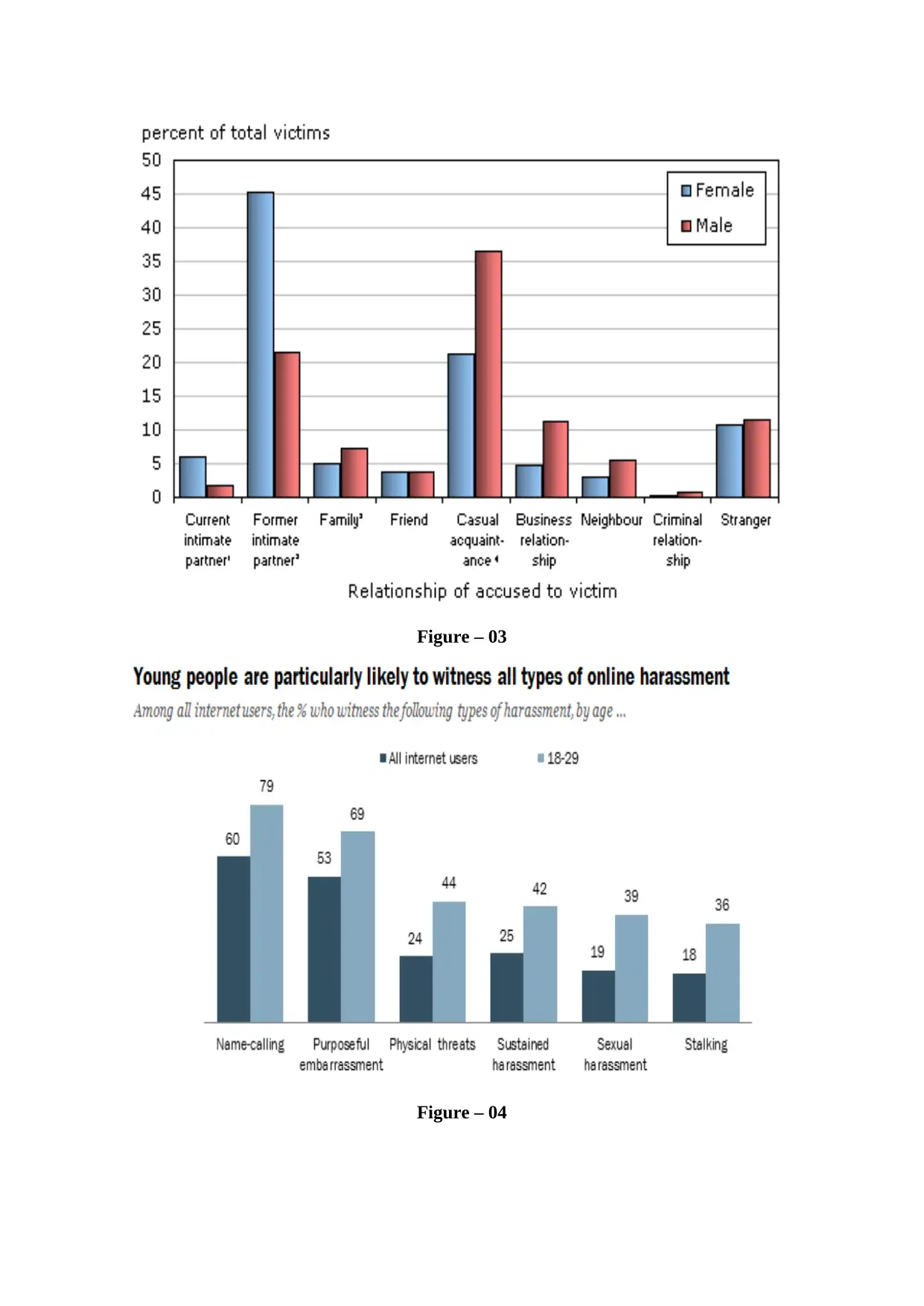

elderly male was kind of sympathetic towards women being made victims (See Figure-

04 in Appendix). Though he cited many stories being circulated in the newspapers about

men being victims of knife-crime. He was not in favour of criminals or against the

victims, but he was aghast at the way all these crime incidents were sensualized in the

newspapers (Finch & Fafinski, 2016).

“Do you think that any other groups may be more fearful of crime than others?” Was

the last question.

Statistics.

FINDINGS & DISCUSSION

Fear of Crime

An interview session with a common questionnaire was conducted with three people,

first being a female, ‘A’ aged 53, second being a male, ‘B’ aged 42 and third being a

female ‘C’ aged 45.

“Would you say that you are fearful of crime?” was the first question.

The female were more cautious when alone in a car park or if they were out after sunset

but then believed that it was fate which was more powerful than being cautious. The

male was echoing same sentiments but had a more pragmatic view of the situation in the

society of elderly people. His idea of safety was not to go to places where you do not

feel safe. However, both were fearful of the prevailing circumstances and the surge of

crime in the society. Another common agreement was about the media. Both agreed that

it was the newspapers which were getting judgemental about how people should live

and what they should do and what they should avoid doing (Bosworth & Hoyle (ed),

2012).

The second question was – “You mentioned the media above. Could you say some more

about that?”

The female were more critical of the media as they believed that media has no right to

dictate to the women in the society. Their point was valid when they raised the question

– why does it have to be women only who have to be careful? Why don’t men behave in

a civilized manner? Why the blame always rests with the women in the society? The

elderly male was kind of sympathetic towards women being made victims (See Figure-

04 in Appendix). Though he cited many stories being circulated in the newspapers about

men being victims of knife-crime. He was not in favour of criminals or against the

victims, but he was aghast at the way all these crime incidents were sensualized in the

newspapers (Finch & Fafinski, 2016).

“Do you think that any other groups may be more fearful of crime than others?” Was

the last question.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The female were of the view that yes, if one lives in a rough neighbourhood, one has

fears about self and children. But both also agreed that sensationalising the crime

created more fear of crime. The male thought that it was more about living among folks

of your own community for safety. He was of the view that minorities were more

vulnerable and feared the most (Simpson, Harrison & Martin, 2012).

Nothing can be more fearsome than the thought of fear and nothing can be more

heinous than the fear of crime. This is what can be derived from the interviews of four

members of a youth group of which two are male, ‘D’ aged 16 and ‘F’ aged 18 and two

are female, ‘E’ aged 17 and ‘G’ aged 16. A common set of questionnaire was put to all

four, individually and results were recorded from their answers (Newburn, 2017).

“Would you say that the members of your community are fearful of crime?” was the

first question.

There was consensus among all the four and they agreed that living away from one’s

own community does create a sense of being unsafe. It also makes women prone to

crime. Going out after dark was strictly avoided and women preferred moving in

groups. The young males agreed that their elders felt more unsecure and were

apprehensive about the safety of their children with the rising cases of hate-crime

(Newburn, 2017).

“You mentioned the media above. Could you say some more about media influence?”

was the second question.

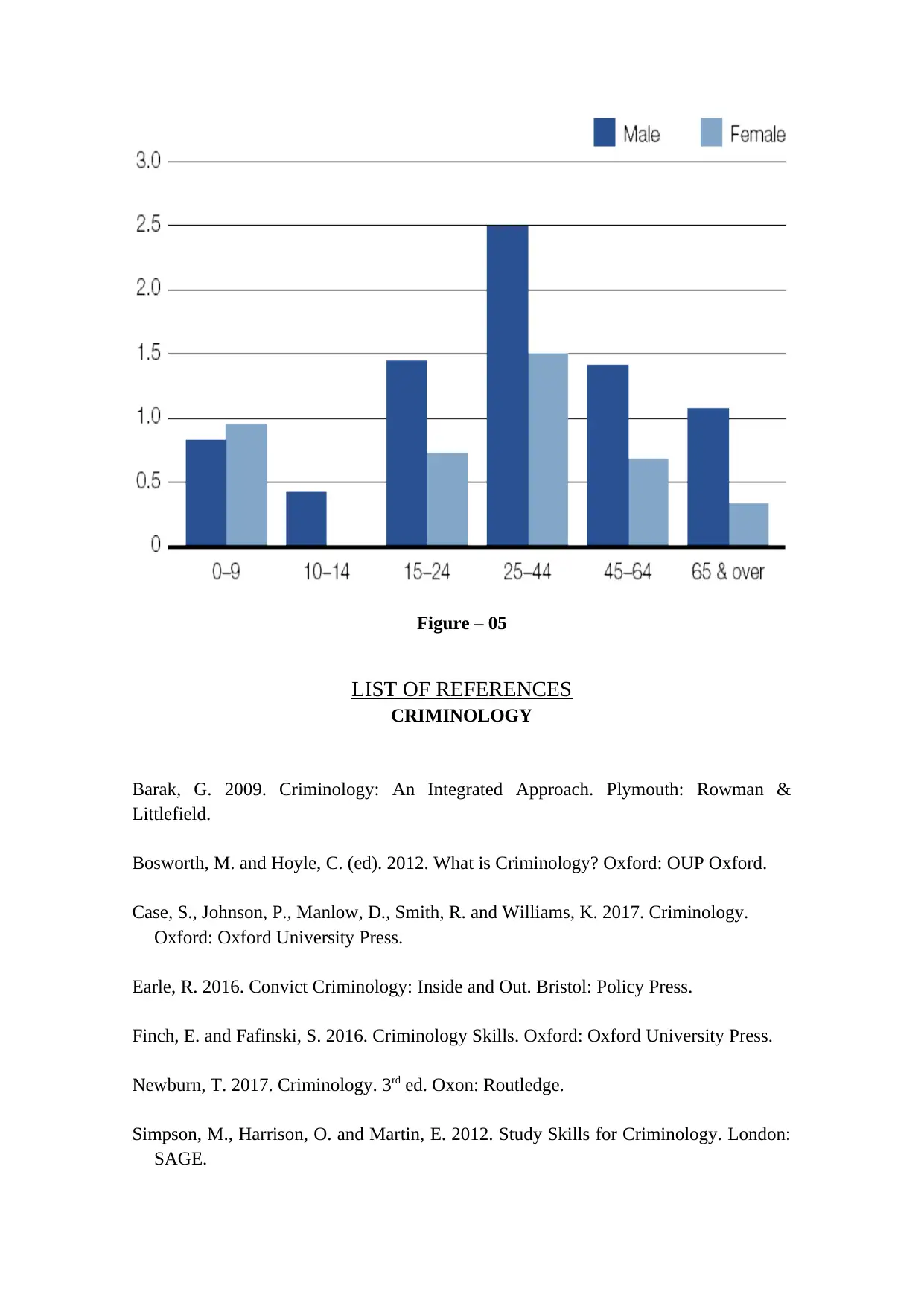

The foursome were equivocal in their view that media was influencing the people with

biased reports. It seems to them that mostly hatred was being promoted by the

newspaper. They also thought that the youth was being distracted by the detective

shows and it was creating a false notion of hero worship among them (See Figure-05 in

Appendix).

“You mentioned earlier that older people and women are more likely to fear crime. Are

there any other groups who are likely to fear crime more than others?” was the final

question.

The young males agreed that although there was nothing wrong in creating groups of

same-liking persons, there can be clashes because of different viewpoints. The females

fears about self and children. But both also agreed that sensationalising the crime

created more fear of crime. The male thought that it was more about living among folks

of your own community for safety. He was of the view that minorities were more

vulnerable and feared the most (Simpson, Harrison & Martin, 2012).

Nothing can be more fearsome than the thought of fear and nothing can be more

heinous than the fear of crime. This is what can be derived from the interviews of four

members of a youth group of which two are male, ‘D’ aged 16 and ‘F’ aged 18 and two

are female, ‘E’ aged 17 and ‘G’ aged 16. A common set of questionnaire was put to all

four, individually and results were recorded from their answers (Newburn, 2017).

“Would you say that the members of your community are fearful of crime?” was the

first question.

There was consensus among all the four and they agreed that living away from one’s

own community does create a sense of being unsafe. It also makes women prone to

crime. Going out after dark was strictly avoided and women preferred moving in

groups. The young males agreed that their elders felt more unsecure and were

apprehensive about the safety of their children with the rising cases of hate-crime

(Newburn, 2017).

“You mentioned the media above. Could you say some more about media influence?”

was the second question.

The foursome were equivocal in their view that media was influencing the people with

biased reports. It seems to them that mostly hatred was being promoted by the

newspaper. They also thought that the youth was being distracted by the detective

shows and it was creating a false notion of hero worship among them (See Figure-05 in

Appendix).

“You mentioned earlier that older people and women are more likely to fear crime. Are

there any other groups who are likely to fear crime more than others?” was the final

question.

The young males agreed that although there was nothing wrong in creating groups of

same-liking persons, there can be clashes because of different viewpoints. The females

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

were scared of hate-crime which could rise because of racism being spread in the

society by the newspaper (Earle, 2016).

Qualitative Analysis

Design

A qualitative analysis was conducted of Personal Value Crimes (PVC) reported in each

paper for measuring two more independent variables: (a) the fearfulness and (b) the

sensationalism of the reporting styles (Case et al, 2017).

Subjects

In total 290 respondents were interviewed for the questionnaire survey on Fear of Crime

(FOC). Twenty were selected for judging the qualitative aspects of newspaper’s

reporting style. Five each were randomly selected from categories consisting of readers

of broadsheets, low-market tabloids and mid-market tabloids and five were non-readers.

The sample was also adjusted by random selection for including equal number of males

and females (Case et al, 2017).

Materials

A random selection of 50 PVC reports was done from the 10 newspapers used in the

quantitative analysis. Provisions were made to have five reports from each newspaper

and the twenty selected stories had two common from each of the ten newspapers

(Finch & Fafinski, 2016). The headlines and the opening sentences, which were fixed

for a maximum of eighty words, were transposed in the same typed format. Under each

report were placed two short questions and respondents were asked to judge, on a scale

of 1-7, the ‘Tearfulness’ and ‘sensationalism’ of newspaper’s reporting style (Bosworth

& Hoyle (ed), 2012).

Procedure

Total ten reports, one each from the ten newspapers, were given to each of the

respondents, along with a letter that explained the requirements which consisted of

judging the style of newspaper’s reporting. To report how frightening the style was, the

respondents were asked to ignore if they had any personal interest in the victim

(Tierney, 2009). As for sensationalism, the judges were asked to assess whether the

newspaper’s report was portraying ‘plain facts’ or whether the newspaper had

‘emphasized, exaggerated, or dramatized in some way’. Respondents were asked to

maintain anonymity and confidentiality (Williams, 2012).

Results

society by the newspaper (Earle, 2016).

Qualitative Analysis

Design

A qualitative analysis was conducted of Personal Value Crimes (PVC) reported in each

paper for measuring two more independent variables: (a) the fearfulness and (b) the

sensationalism of the reporting styles (Case et al, 2017).

Subjects

In total 290 respondents were interviewed for the questionnaire survey on Fear of Crime

(FOC). Twenty were selected for judging the qualitative aspects of newspaper’s

reporting style. Five each were randomly selected from categories consisting of readers

of broadsheets, low-market tabloids and mid-market tabloids and five were non-readers.

The sample was also adjusted by random selection for including equal number of males

and females (Case et al, 2017).

Materials

A random selection of 50 PVC reports was done from the 10 newspapers used in the

quantitative analysis. Provisions were made to have five reports from each newspaper

and the twenty selected stories had two common from each of the ten newspapers

(Finch & Fafinski, 2016). The headlines and the opening sentences, which were fixed

for a maximum of eighty words, were transposed in the same typed format. Under each

report were placed two short questions and respondents were asked to judge, on a scale

of 1-7, the ‘Tearfulness’ and ‘sensationalism’ of newspaper’s reporting style (Bosworth

& Hoyle (ed), 2012).

Procedure

Total ten reports, one each from the ten newspapers, were given to each of the

respondents, along with a letter that explained the requirements which consisted of

judging the style of newspaper’s reporting. To report how frightening the style was, the

respondents were asked to ignore if they had any personal interest in the victim

(Tierney, 2009). As for sensationalism, the judges were asked to assess whether the

newspaper’s report was portraying ‘plain facts’ or whether the newspaper had

‘emphasized, exaggerated, or dramatized in some way’. Respondents were asked to

maintain anonymity and confidentiality (Williams, 2012).

Results

Since there were differences among the groups of readers, a demographic analysis was

carried out of the groups. Age had no relationship to the type of newspapers read and

sex discrimination was also not there in the linear fashion across all groups. However,

education and socioeconomic status (SES) being important, were incorporated

(Williams, 2012). It was deduced that the readers of Broadsheet left their full-time

education at a mean age of 17.35 years, the mid-market tabloid readers left at mean age

of 16.22 years and the mean age of the low-market tabloid readers was found to be

15.54 years. This was found to be statistically significant (F(2,193) = 7.63, p<0.001). It

was also established the readers of the broadsheet recorded the highest SES and the

readers of the low-market tabloid recorded the lowest SES (F(2,195) = 10.05, /><

0.001) (Newburn, 2017).

The results of the survey showed that the broadsheet readers demonstrated lowest and

the low-market tabloid readers showed the highest levels of FOC on all the given

measures, except the behavioural one. A strong relationship was observed between

newspaper readership groups and their socioeconomic status and the evidence

confirmed that newspaper readership was related to FOC independently irrespective of

the group’s socioeconomic status (Newburn, 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

Finally, the evidence proves that newspapers ‘construct’ news as is found in the

differences between same news in two different newspapers. In conclusion, it can be

safely stated that reporting of crime by the British daily press has shown enormous

variation. The newspapers which reported most crime and in particular crimes related to

personal violence in the most salient fashion, both visually and stylistically, have the

readership which has the highest FOC levels.

APPENDIX

carried out of the groups. Age had no relationship to the type of newspapers read and

sex discrimination was also not there in the linear fashion across all groups. However,

education and socioeconomic status (SES) being important, were incorporated

(Williams, 2012). It was deduced that the readers of Broadsheet left their full-time

education at a mean age of 17.35 years, the mid-market tabloid readers left at mean age

of 16.22 years and the mean age of the low-market tabloid readers was found to be

15.54 years. This was found to be statistically significant (F(2,193) = 7.63, p<0.001). It

was also established the readers of the broadsheet recorded the highest SES and the

readers of the low-market tabloid recorded the lowest SES (F(2,195) = 10.05, /><

0.001) (Newburn, 2017).

The results of the survey showed that the broadsheet readers demonstrated lowest and

the low-market tabloid readers showed the highest levels of FOC on all the given

measures, except the behavioural one. A strong relationship was observed between

newspaper readership groups and their socioeconomic status and the evidence

confirmed that newspaper readership was related to FOC independently irrespective of

the group’s socioeconomic status (Newburn, 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

Finally, the evidence proves that newspapers ‘construct’ news as is found in the

differences between same news in two different newspapers. In conclusion, it can be

safely stated that reporting of crime by the British daily press has shown enormous

variation. The newspapers which reported most crime and in particular crimes related to

personal violence in the most salient fashion, both visually and stylistically, have the

readership which has the highest FOC levels.

APPENDIX

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure – 01

Figure – 02

Figure – 02

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Figure – 03

Figure – 04

Figure – 04

Figure – 05

LIST OF REFERENCES

CRIMINOLOGY

Barak, G. 2009. Criminology: An Integrated Approach. Plymouth: Rowman &

Littlefield.

Bosworth, M. and Hoyle, C. (ed). 2012. What is Criminology? Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Case, S., Johnson, P., Manlow, D., Smith, R. and Williams, K. 2017. Criminology.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Earle, R. 2016. Convict Criminology: Inside and Out. Bristol: Policy Press.

Finch, E. and Fafinski, S. 2016. Criminology Skills. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newburn, T. 2017. Criminology. 3rd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

Simpson, M., Harrison, O. and Martin, E. 2012. Study Skills for Criminology. London:

SAGE.

LIST OF REFERENCES

CRIMINOLOGY

Barak, G. 2009. Criminology: An Integrated Approach. Plymouth: Rowman &

Littlefield.

Bosworth, M. and Hoyle, C. (ed). 2012. What is Criminology? Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Case, S., Johnson, P., Manlow, D., Smith, R. and Williams, K. 2017. Criminology.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Earle, R. 2016. Convict Criminology: Inside and Out. Bristol: Policy Press.

Finch, E. and Fafinski, S. 2016. Criminology Skills. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newburn, T. 2017. Criminology. 3rd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

Simpson, M., Harrison, O. and Martin, E. 2012. Study Skills for Criminology. London:

SAGE.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Tierney, J. 2009. Key Perspectives In Criminology. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education

(UK).

Williams, K.S. 2012. Textbook on Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, P. and Dickinson, J. 1993. FEAR OF CRIME: READ ALL ABOUT IT: The

Relationship between Newspaper Crime Reporting and Fear of Crime. The British

Journal of Criminology, Vol.33 No. 1.

(UK).

Williams, K.S. 2012. Textbook on Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, P. and Dickinson, J. 1993. FEAR OF CRIME: READ ALL ABOUT IT: The

Relationship between Newspaper Crime Reporting and Fear of Crime. The British

Journal of Criminology, Vol.33 No. 1.

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.