Perceived Fairness, Emotions, and Intention of Fast Food Chain Restaurants Customers in Indonesia

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/24

|26

|13577

|60

AI Summary

This study aims to investigate interrelationships among perceived service fairness, emotions, and behavioral intentions in a fast food chain restaurant context. The study uses purposive sampling and the survey method to generate a sample of 800 respondents from big cities in Indonesia. The data are analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The results show different roles for each fairness perception in relation to peoples’ emotions and behavioral intentions, based on the Mehrabian-Russel model.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

229

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business

Vol. 20, No. 2 (May-August 2018): 229-253

* Corresponding author’s e-mail: hetyvirgo89@gmail.com

ISSN: 1141-1128

http://journal.ugm.ac.id/gamaijb

Perceived Fairness, Emotions, and Intention

of Fast Food Chain Restaurants Customers

in Indonesia

Hety Budiyanti,1* andShine Pintor Siolemba Patiro2

1 State University Makassar, Indonesia

2 Facilitator of HR Development Board Central Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

Abstract: This study aims to investigate interrelationships among perceived service fairne

and behavioral intentions in a fast food chain restaurant context. we use terms that are co

the study of fairness or justice perception. This study uses purposive sampling and the su

generate our sample which consists of 800 respondents from big cities in Indonesia, name

Semarang, Surabaya, Medan, and Makassar. The data are analyzed using Structural Equa

(SEM). The results show different roles for each fairness perception in relation to peoples’

behavioral intentions, based on the Mehrabian-Russel model. Three fairness variables (pri

come fairness and interactional fairness) have positive and significant effects on customer

tions, while, procedural fairness does not influence the formation of a positive emotion. Fu

positive emotion has a positive influence on a customer’s behavioral intention. Data collec

are limited to the context of the restaurant industry, therefore, precaution must be taken

ing these results to other industries. The results of this study can serve as guidelines for m

restaurant industry to develop effective and efficient strategies for ensuring their services

ness and its impact on both customers’ retention rates and the companies’ financial gains.

Keywords:behavioral intention; emotions; service fairness; structural equation mode

JEL classification: C3, M31, M39

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business

Vol. 20, No. 2 (May-August 2018): 229-253

* Corresponding author’s e-mail: hetyvirgo89@gmail.com

ISSN: 1141-1128

http://journal.ugm.ac.id/gamaijb

Perceived Fairness, Emotions, and Intention

of Fast Food Chain Restaurants Customers

in Indonesia

Hety Budiyanti,1* andShine Pintor Siolemba Patiro2

1 State University Makassar, Indonesia

2 Facilitator of HR Development Board Central Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

Abstract: This study aims to investigate interrelationships among perceived service fairne

and behavioral intentions in a fast food chain restaurant context. we use terms that are co

the study of fairness or justice perception. This study uses purposive sampling and the su

generate our sample which consists of 800 respondents from big cities in Indonesia, name

Semarang, Surabaya, Medan, and Makassar. The data are analyzed using Structural Equa

(SEM). The results show different roles for each fairness perception in relation to peoples’

behavioral intentions, based on the Mehrabian-Russel model. Three fairness variables (pri

come fairness and interactional fairness) have positive and significant effects on customer

tions, while, procedural fairness does not influence the formation of a positive emotion. Fu

positive emotion has a positive influence on a customer’s behavioral intention. Data collec

are limited to the context of the restaurant industry, therefore, precaution must be taken

ing these results to other industries. The results of this study can serve as guidelines for m

restaurant industry to develop effective and efficient strategies for ensuring their services

ness and its impact on both customers’ retention rates and the companies’ financial gains.

Keywords:behavioral intention; emotions; service fairness; structural equation mode

JEL classification: C3, M31, M39

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

BudiyantiandPatiro

230

Introduction

Over the last decade, fairness principles

(distributive fairness, procedural fairness, and

interactional fairness) have been applied to

numerous studies such as management, psy-

chology, and organizational attitudes (Azar

and Darvishi 2011; Blader et al. 2013), as

well as legal and political studies (i.e. Zmerli

and Castillo 2015). For example, Azarand

Darvishi (2011) created a measure for

organisational fairness based on the fairness

theory from Folger and Cropanzano (1998),

where they measure organizational fairness

based on fairnesses’ perception. They show

that the use of a different measurement for

organisational fairness will produce a differ-

ent result.

Academics and practitioners’ interest in

conceptualizing service fairness has increased

along with the development of service mar-

keting literature (Aggarwal and Larrick

2012). The studies by Heo and Lee (2011),

Liang et al. (2017), Wang et al. (2018) all show

that when customers are aware of any devia-

tion from the fairness principles, it may trig-

ger a perception of unfairness. Moreover, con-

sumers’ individual characteristics will influ-

ence their perception of fairness depending

on what they experience. In line with these

studies, Aggarwal and Larrick (2012) show

that consumers’ responses toward perceived

interactional fairness are contingent on the

form of their social relationship (communal

and exchange), including the conditon of per-

ceived distributive fairness. Linking its effects

on emotions and attitudes, Smith and Bolton

(2002) argue that customers are involved in

a psychological contract with the service pro-

vider who gratifies their needs and treats them

fairly (Chalmers 2016). When a service pro-

vider neglects fairness when providing a ser-

vice to their customers, it may create a nega-

tive emotion among the customers, which

could lead them to boycott the service pro-

vider, or make public their unpleaseant ex-

perience (Kaura et al. 2015; Liang et al. 2017;

Liu et al. 2017)

For customers, fairness and quality ser-

vice are inseparable points (Sekhon et al.

2016). Fairness is not merely one dimension

of service, rather, it embraces all the dimen-

sions of good quality service (Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Naquin et al. 2015). Giovanis

et al. (2015) and Nikbin et al. (2016) argue

that poor service is not a service that equates

with low quality service, it is a distinct phe-

nomenon. In relation to the quality of ser-

vice, the fairness principle offers a specific

framework to understand the process of a

service’s consumption related to it’s fairness,

and this may be use as a substantial compo-

nent in evaluating the service (Cropanzano

et al. 2008; Heo and Lee 2011). Therefore, it

is worthwhile studying the appropriateness of

fairness as one of the instruments when

evaluating any service (Aggarwal and Larrick

2012).

It has been widely recognized that con-

siderations regarding fairness elicit emotional

responses, particularly, when unfairness oc-

curs (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001;

Barclay et al. 2005) and finally lead to be-

havioral reactions such as complaints, nega-

tive word-of-mouth recommendations, or

support (Adams 1966). Furthermore, despite

previous fairness theory and other studies

having shown that emotion forms a part of

the relationship between experiencing unfair-

ness and wanting to retaliate, there are only a

few studies that have tested the relationship

between fairness, emotion, and behavioral

intention (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001;

Barclay et al. 2005).

230

Introduction

Over the last decade, fairness principles

(distributive fairness, procedural fairness, and

interactional fairness) have been applied to

numerous studies such as management, psy-

chology, and organizational attitudes (Azar

and Darvishi 2011; Blader et al. 2013), as

well as legal and political studies (i.e. Zmerli

and Castillo 2015). For example, Azarand

Darvishi (2011) created a measure for

organisational fairness based on the fairness

theory from Folger and Cropanzano (1998),

where they measure organizational fairness

based on fairnesses’ perception. They show

that the use of a different measurement for

organisational fairness will produce a differ-

ent result.

Academics and practitioners’ interest in

conceptualizing service fairness has increased

along with the development of service mar-

keting literature (Aggarwal and Larrick

2012). The studies by Heo and Lee (2011),

Liang et al. (2017), Wang et al. (2018) all show

that when customers are aware of any devia-

tion from the fairness principles, it may trig-

ger a perception of unfairness. Moreover, con-

sumers’ individual characteristics will influ-

ence their perception of fairness depending

on what they experience. In line with these

studies, Aggarwal and Larrick (2012) show

that consumers’ responses toward perceived

interactional fairness are contingent on the

form of their social relationship (communal

and exchange), including the conditon of per-

ceived distributive fairness. Linking its effects

on emotions and attitudes, Smith and Bolton

(2002) argue that customers are involved in

a psychological contract with the service pro-

vider who gratifies their needs and treats them

fairly (Chalmers 2016). When a service pro-

vider neglects fairness when providing a ser-

vice to their customers, it may create a nega-

tive emotion among the customers, which

could lead them to boycott the service pro-

vider, or make public their unpleaseant ex-

perience (Kaura et al. 2015; Liang et al. 2017;

Liu et al. 2017)

For customers, fairness and quality ser-

vice are inseparable points (Sekhon et al.

2016). Fairness is not merely one dimension

of service, rather, it embraces all the dimen-

sions of good quality service (Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Naquin et al. 2015). Giovanis

et al. (2015) and Nikbin et al. (2016) argue

that poor service is not a service that equates

with low quality service, it is a distinct phe-

nomenon. In relation to the quality of ser-

vice, the fairness principle offers a specific

framework to understand the process of a

service’s consumption related to it’s fairness,

and this may be use as a substantial compo-

nent in evaluating the service (Cropanzano

et al. 2008; Heo and Lee 2011). Therefore, it

is worthwhile studying the appropriateness of

fairness as one of the instruments when

evaluating any service (Aggarwal and Larrick

2012).

It has been widely recognized that con-

siderations regarding fairness elicit emotional

responses, particularly, when unfairness oc-

curs (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001;

Barclay et al. 2005) and finally lead to be-

havioral reactions such as complaints, nega-

tive word-of-mouth recommendations, or

support (Adams 1966). Furthermore, despite

previous fairness theory and other studies

having shown that emotion forms a part of

the relationship between experiencing unfair-

ness and wanting to retaliate, there are only a

few studies that have tested the relationship

between fairness, emotion, and behavioral

intention (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001;

Barclay et al. 2005).

231

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

For example, Cropanzano and Stein

(2009) show that organizational unfairness is

capable of influencing the ocurrence of em-

ployees’ negative emotions, which can lead

to their unethical behavior as a result of the

unfairness they experienced. Tzafrir and

Hareli (2009) conducted a study into the in-

fluence of organizational justice on the for-

mation of employees’ positive and negative

emotions when they receive a promotion.

Their study only focused on two variables of

organizational fairness, which were proce-

dural justice and distributive justice. Reuben

and van Winden (2010) argue that a per-

ceived unfairness by an individual will form

a perceived negative emotion (guilt and hu-

miliation) but has no consequence on the for-

mation of certain behavior. Radke et al.

(2013) studied the irrational behavior carried

out by individuals who experience depression

as a result of perceived unfairness towards

their negative emotions. They employed a

unidimensional fairness concept in their re-

search, aside from the fairness concept, which

comprised of procedural, distributive, and

interactional fairness. A study by Uludag

(2014) on the infuence of fairness toward

verbal and physical aggresion does not fully

explain the measure of the dimension of fair-

ness towards aggresion as a form of negative

emotion. Moreover, the study by Silva and

Caetano (2016) into organizational fairness

across different cultures shows that differ-

ences in the perception of an organization’s

members toward organizational fairness is

related to the culture where the organization

belongs. They state that the consequences that

arise from organizational unfairness are posi-

tive and negative emotions which are ex-

pressed by the employees both verbally and

nonverbally.

According to the previous studies, as

mentioned above, this study concluded that

those studies tended to be conducted in som

type of organizational setting and not in the

area of service hospitality organizations,

such as hotels or restaurants. The fairnes

concept used mostly in those studies is based

on the concept of the equity theory proposed

by Adams (1966); while this study uses t

fairness concept proposed by Seiders and

Berry (1998). Consumers perceive and asses

fairness or unfairness based on the situation

related to the potential of maximizing prof-

its by minimizing personal investment or sac

rifice (Chou et al. 2009). Therefore, accord-

ing to this study, the benefits received by cus

tomers and their sacrifices are related to the

actual context of the fairness theory (distribu

tive fairness, procedural fairness, and inte

actional fairness). Thus, this study hopes to

obtain a better understanding concerning

service’s fairness that captures all the va

ous service contexts based on consumers’

sacrifices and the benefits they receive. Mon

etary and time costs, which are associate

with the experience of customers’ consump-

tion, are consider as constructs representing

sacrifices made by customers, while product

(services non-interactions) and personnel (th

way customers are treated) obtained by cus-

tomers while consuming products or services

are consider as constructs representing cus-

tomers’ benefits.

In order to fill this research gap, thi

study proposes a theoretical model which re-

lates to service fairness, emotion, and behav

ioral intentions, and examines this empirical

in the context of the service industry, espe-

cially for restaurants. The definition of ser-

vice fairness used in this study is the service

fairness perception of customers related t

the service behavior of organizations or com

panies (Namkung and Jang 2010). The back-

ground of this study is the customers of fast-

food chain restaurants in Indonesia. Based o

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

For example, Cropanzano and Stein

(2009) show that organizational unfairness is

capable of influencing the ocurrence of em-

ployees’ negative emotions, which can lead

to their unethical behavior as a result of the

unfairness they experienced. Tzafrir and

Hareli (2009) conducted a study into the in-

fluence of organizational justice on the for-

mation of employees’ positive and negative

emotions when they receive a promotion.

Their study only focused on two variables of

organizational fairness, which were proce-

dural justice and distributive justice. Reuben

and van Winden (2010) argue that a per-

ceived unfairness by an individual will form

a perceived negative emotion (guilt and hu-

miliation) but has no consequence on the for-

mation of certain behavior. Radke et al.

(2013) studied the irrational behavior carried

out by individuals who experience depression

as a result of perceived unfairness towards

their negative emotions. They employed a

unidimensional fairness concept in their re-

search, aside from the fairness concept, which

comprised of procedural, distributive, and

interactional fairness. A study by Uludag

(2014) on the infuence of fairness toward

verbal and physical aggresion does not fully

explain the measure of the dimension of fair-

ness towards aggresion as a form of negative

emotion. Moreover, the study by Silva and

Caetano (2016) into organizational fairness

across different cultures shows that differ-

ences in the perception of an organization’s

members toward organizational fairness is

related to the culture where the organization

belongs. They state that the consequences that

arise from organizational unfairness are posi-

tive and negative emotions which are ex-

pressed by the employees both verbally and

nonverbally.

According to the previous studies, as

mentioned above, this study concluded that

those studies tended to be conducted in som

type of organizational setting and not in the

area of service hospitality organizations,

such as hotels or restaurants. The fairnes

concept used mostly in those studies is based

on the concept of the equity theory proposed

by Adams (1966); while this study uses t

fairness concept proposed by Seiders and

Berry (1998). Consumers perceive and asses

fairness or unfairness based on the situation

related to the potential of maximizing prof-

its by minimizing personal investment or sac

rifice (Chou et al. 2009). Therefore, accord-

ing to this study, the benefits received by cus

tomers and their sacrifices are related to the

actual context of the fairness theory (distribu

tive fairness, procedural fairness, and inte

actional fairness). Thus, this study hopes to

obtain a better understanding concerning

service’s fairness that captures all the va

ous service contexts based on consumers’

sacrifices and the benefits they receive. Mon

etary and time costs, which are associate

with the experience of customers’ consump-

tion, are consider as constructs representing

sacrifices made by customers, while product

(services non-interactions) and personnel (th

way customers are treated) obtained by cus-

tomers while consuming products or services

are consider as constructs representing cus-

tomers’ benefits.

In order to fill this research gap, thi

study proposes a theoretical model which re-

lates to service fairness, emotion, and behav

ioral intentions, and examines this empirical

in the context of the service industry, espe-

cially for restaurants. The definition of ser-

vice fairness used in this study is the service

fairness perception of customers related t

the service behavior of organizations or com

panies (Namkung and Jang 2010). The back-

ground of this study is the customers of fast-

food chain restaurants in Indonesia. Based o

BudiyantiandPatiro

232

the data from Euromonitor International: Fast

Food in Indonesia year 2016, there are 7,236

fast-food chain restaurants throughout Indo-

nesia, which are mainly located in the big cit-

ies. According to data from AAFC Kanada,

part of the Ministry of Farming and Agri-

food, in 2015, the fast-food chain industry in

Indonesia is predicted to grow at roughly

around 9.2 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Therefore, it is appropriate to select fast-food

restaurants for our study’s setting.

This study was conducted in the big cit-

ies in Indonesia, such as Jakarta, Semarang,

Surabaya, Medan, and Makassar, where some

of these fast-food chain restaurants are lo-

cated. The selection of research locations is

based on the areas that have high economic

growth and big populations. These fast-food

chain restaurants have always emphasized

they satisfy their customers with the quality

of their service.

Based on the previous discussions, the

main objectives of this study are to deter-

mine the relationship between service fair-

ness, emotions, and behavioral intentions,

and to discern the level of importance of each

dimension of service fairness in the context

of restaurant services, and to provide infor-

mation for fast-food chain restaurant entre-

preneurs to evaluate their service’s qualities

in terms of their service’s fairness.

Literature Review

The Effect of Fairness on Service

Marketing

Fairness is defined as an action which

is deemed appropriate from an individual’s

perception (Aggarwal and Larrick 2012). The

term fairness is often used with regard to the

ability to make unbiased, concrete and spe-

cific judgements about a particular case with-

out referring to one’s own fe elin gs

(Goldenberg et al. 2016; Faullant et al. 2017).

In connection with the marketing of

services, Bagozzi (1975) introduces the con-

cept of fairness/equity into the marketing

exchange theory. He examines the relation-

ship of fairness in the context of dyadic reci-

procity and the equality needed to maintain

the process of ongoing exchanges between

the customer and the marketer. Aggarwal and

Larrick (2012) and Blader et al. (2013) also

discuss the consumers’ perceptions of mar-

keting practices which are unfair, and so have

consequences

Seiders and Berry (1998) summarize

the relevant principles based on three catego-

ries of fairness (procedural, distributive, and

interactional) and show these principles are

appropriate for customers to assess the fair-

ness they have experienced. Aggarwal and

Larrick (2012) and Lee et al. (2013) also

found that three types of fairness are likely

to be relevant for background services, such

as those found in banks, medical facilities,

fast-food restaurants, and luxury restaurants,

and hence these may be used as a basis for

assessment by consumers.

The role of fairness in the context of

the recovery of service failures has also been

the focus of attention in many studies. Ac-

cording to Chou et al. (2009) the role of fair-

ness, in the context of the recovery of ser-

vice failures, is particulary significant for

some service industries, such as hairdressers,

restaurants or cafes, supermarkets, and banks.

By adding a moderating effect of loyalty, Hur

et al. (2014) found that both types of fair-

ness (distributive fairness and procedural fair-

ness), when performing recovery services,

have a significant influence on the reactions

of loyal customers. Although the principles

232

the data from Euromonitor International: Fast

Food in Indonesia year 2016, there are 7,236

fast-food chain restaurants throughout Indo-

nesia, which are mainly located in the big cit-

ies. According to data from AAFC Kanada,

part of the Ministry of Farming and Agri-

food, in 2015, the fast-food chain industry in

Indonesia is predicted to grow at roughly

around 9.2 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Therefore, it is appropriate to select fast-food

restaurants for our study’s setting.

This study was conducted in the big cit-

ies in Indonesia, such as Jakarta, Semarang,

Surabaya, Medan, and Makassar, where some

of these fast-food chain restaurants are lo-

cated. The selection of research locations is

based on the areas that have high economic

growth and big populations. These fast-food

chain restaurants have always emphasized

they satisfy their customers with the quality

of their service.

Based on the previous discussions, the

main objectives of this study are to deter-

mine the relationship between service fair-

ness, emotions, and behavioral intentions,

and to discern the level of importance of each

dimension of service fairness in the context

of restaurant services, and to provide infor-

mation for fast-food chain restaurant entre-

preneurs to evaluate their service’s qualities

in terms of their service’s fairness.

Literature Review

The Effect of Fairness on Service

Marketing

Fairness is defined as an action which

is deemed appropriate from an individual’s

perception (Aggarwal and Larrick 2012). The

term fairness is often used with regard to the

ability to make unbiased, concrete and spe-

cific judgements about a particular case with-

out referring to one’s own fe elin gs

(Goldenberg et al. 2016; Faullant et al. 2017).

In connection with the marketing of

services, Bagozzi (1975) introduces the con-

cept of fairness/equity into the marketing

exchange theory. He examines the relation-

ship of fairness in the context of dyadic reci-

procity and the equality needed to maintain

the process of ongoing exchanges between

the customer and the marketer. Aggarwal and

Larrick (2012) and Blader et al. (2013) also

discuss the consumers’ perceptions of mar-

keting practices which are unfair, and so have

consequences

Seiders and Berry (1998) summarize

the relevant principles based on three catego-

ries of fairness (procedural, distributive, and

interactional) and show these principles are

appropriate for customers to assess the fair-

ness they have experienced. Aggarwal and

Larrick (2012) and Lee et al. (2013) also

found that three types of fairness are likely

to be relevant for background services, such

as those found in banks, medical facilities,

fast-food restaurants, and luxury restaurants,

and hence these may be used as a basis for

assessment by consumers.

The role of fairness in the context of

the recovery of service failures has also been

the focus of attention in many studies. Ac-

cording to Chou et al. (2009) the role of fair-

ness, in the context of the recovery of ser-

vice failures, is particulary significant for

some service industries, such as hairdressers,

restaurants or cafes, supermarkets, and banks.

By adding a moderating effect of loyalty, Hur

et al. (2014) found that both types of fair-

ness (distributive fairness and procedural fair-

ness), when performing recovery services,

have a significant influence on the reactions

of loyal customers. Although the principles

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

233

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

of fairness have provided a better under-

standing concerning the influence of fairness,

especially in the context of service failures

and service recovery, yet other areas of re-

search outside these two contexts are limited

and not well developed.

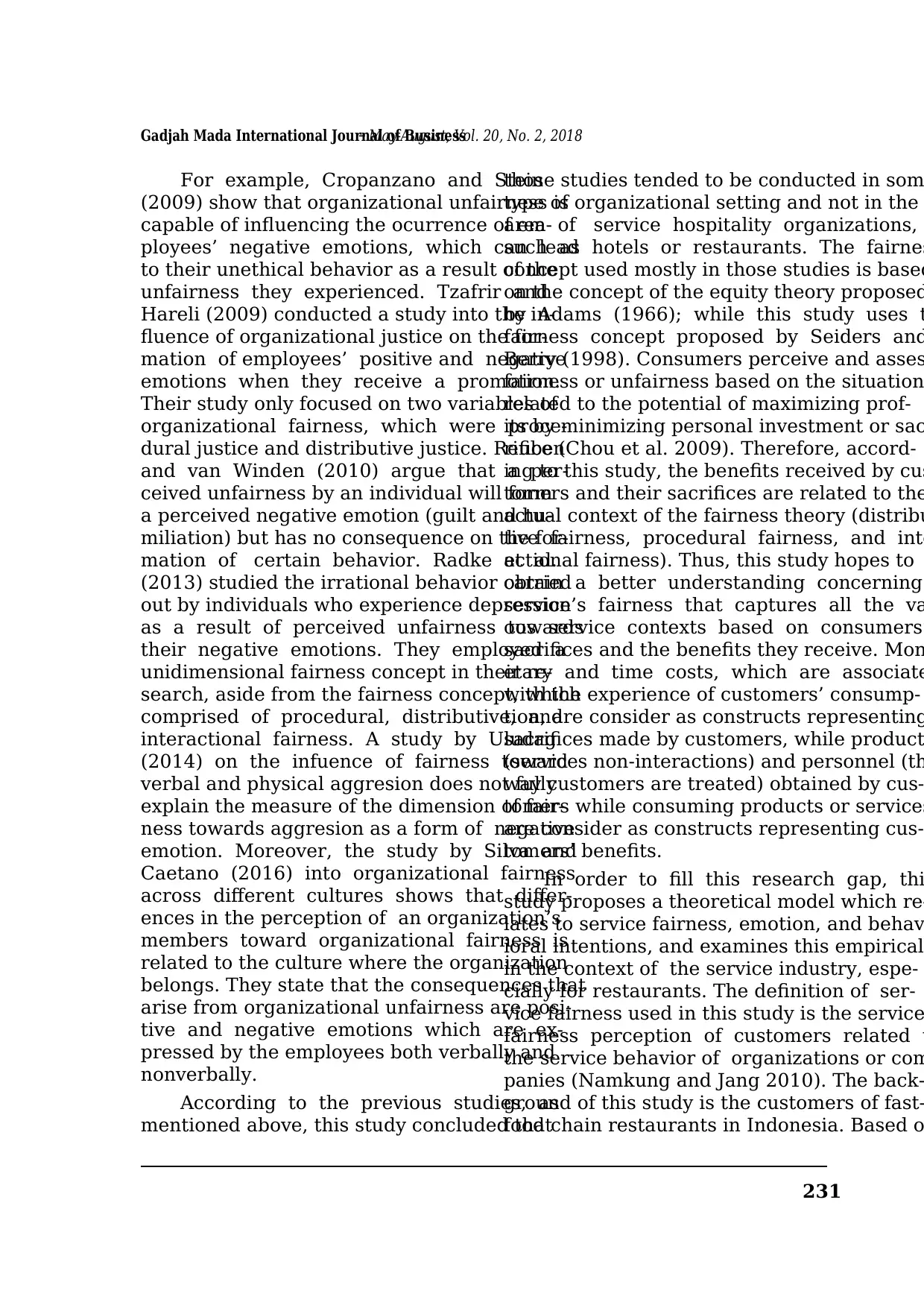

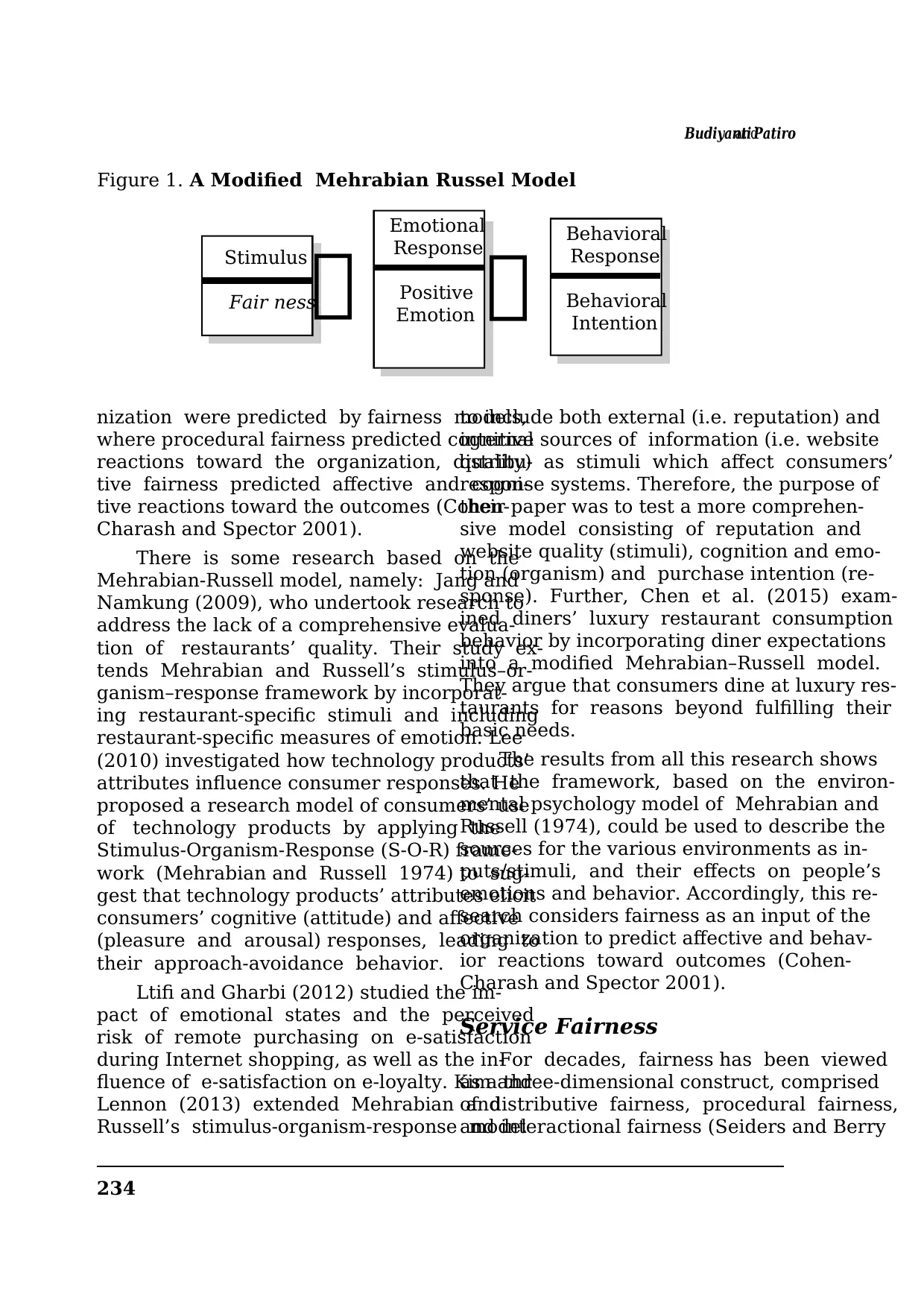

Mehrabian-Russell Model

This study is based on a model devel-

oped by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) for

environmental psychology. They proposed

that environmental stimuli (S) lead to an

emotional reaction (O) which, in turn, drives

consumers’ behavioral response (R), based on

the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R)

paradigm. They posited that consumers have

three emotional states in response to envi-

ronmental stimuli: Pleasure, arousal, and

dominance. According to their study, these

emotional responses result in two contrast-

ing behaviors: Approach or avoidance. Ap-

proach behavior involves a desire to stay,

explore, and affiliate with others in the envi-

ronment, whereas avoidance behavior in-

cludes escaping from the environment and

ignoring any communication attempts from

other people (Jang and Namkung 2009;

Namkung and Jang 2010). Using Mehrabian

and Russell’s model, many studies have been

conducted on the role of environmental

stimuli as a predictor of emotional responses,

such as pleasure or arousal, and as a predic-

tor of consumers’ behavior, such as the ex-

tra-time they spend in a store and their ac-

tual incremental spending (Jang and Namkung

2009).

Based on the Mehrabian-Russell model,

environmental stimuli will affect the individu-

als’ emotions and as a result will affect their

response in the form of approach or avoid-

ance (Namkung and Jang 2010). In their re-

search model, stimuli are the stimuli is lo-

cated externally from people and consist of

various elements of physical atmosphere.

Furthermore, the organism refers to structur

and internal processes which consequently

will intervene in the relationship between the

external stimuli of people and the attitud

being demonstrated or responded to. This

suggests that the impact of the stimuli o

human behavioral intentions is mediated by

emotion.

According to Mehrabian and Russell

(1974), there are three forms of emotion

namely: Pleasure, passion, and power. Fu

thermore, the response to the environment

can be classified as either an approach o

avoidance. Approach behavior includes such

things as: Desire to stay, observe the are

around you, explore the environment, and

communicate with others in the environment

Avoidance behavior is the opposite of ap

proach behavior. Our study applies the mode

of Mehrabian and Russell (1974) and modi-

fies it in accordance with the background of

this research (see Figure 1).

In line with Mehrabian and Russell

(1974), some justice researchers rely on the

social exchange theory to predict relation

tween perceived fairness and its outcome

(Cropanzano et al. 2007; Cropanzano et a

2008; Cropanzano and Stein 2009). The so-

cial exchange theory views organizations

arenas for long-term, mutual social transac-

tions between employees and their organiza-

tion (Cropanzano et al. 2007; Cropanzano et

al. 2008; Cropanzano and Stein 2009). Ju

tice is considered to be an input of the orga-

nization to the exchange relationship and

derives from either (a) the organization or (b

the direct supervisor (Cohen-Charash and

Spector 2001). Futhermore, according to

Cohen-Charash and Spector (2001), attitudi-

nal and affective reactions toward the orga-

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

of fairness have provided a better under-

standing concerning the influence of fairness,

especially in the context of service failures

and service recovery, yet other areas of re-

search outside these two contexts are limited

and not well developed.

Mehrabian-Russell Model

This study is based on a model devel-

oped by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) for

environmental psychology. They proposed

that environmental stimuli (S) lead to an

emotional reaction (O) which, in turn, drives

consumers’ behavioral response (R), based on

the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R)

paradigm. They posited that consumers have

three emotional states in response to envi-

ronmental stimuli: Pleasure, arousal, and

dominance. According to their study, these

emotional responses result in two contrast-

ing behaviors: Approach or avoidance. Ap-

proach behavior involves a desire to stay,

explore, and affiliate with others in the envi-

ronment, whereas avoidance behavior in-

cludes escaping from the environment and

ignoring any communication attempts from

other people (Jang and Namkung 2009;

Namkung and Jang 2010). Using Mehrabian

and Russell’s model, many studies have been

conducted on the role of environmental

stimuli as a predictor of emotional responses,

such as pleasure or arousal, and as a predic-

tor of consumers’ behavior, such as the ex-

tra-time they spend in a store and their ac-

tual incremental spending (Jang and Namkung

2009).

Based on the Mehrabian-Russell model,

environmental stimuli will affect the individu-

als’ emotions and as a result will affect their

response in the form of approach or avoid-

ance (Namkung and Jang 2010). In their re-

search model, stimuli are the stimuli is lo-

cated externally from people and consist of

various elements of physical atmosphere.

Furthermore, the organism refers to structur

and internal processes which consequently

will intervene in the relationship between the

external stimuli of people and the attitud

being demonstrated or responded to. This

suggests that the impact of the stimuli o

human behavioral intentions is mediated by

emotion.

According to Mehrabian and Russell

(1974), there are three forms of emotion

namely: Pleasure, passion, and power. Fu

thermore, the response to the environment

can be classified as either an approach o

avoidance. Approach behavior includes such

things as: Desire to stay, observe the are

around you, explore the environment, and

communicate with others in the environment

Avoidance behavior is the opposite of ap

proach behavior. Our study applies the mode

of Mehrabian and Russell (1974) and modi-

fies it in accordance with the background of

this research (see Figure 1).

In line with Mehrabian and Russell

(1974), some justice researchers rely on the

social exchange theory to predict relation

tween perceived fairness and its outcome

(Cropanzano et al. 2007; Cropanzano et a

2008; Cropanzano and Stein 2009). The so-

cial exchange theory views organizations

arenas for long-term, mutual social transac-

tions between employees and their organiza-

tion (Cropanzano et al. 2007; Cropanzano et

al. 2008; Cropanzano and Stein 2009). Ju

tice is considered to be an input of the orga-

nization to the exchange relationship and

derives from either (a) the organization or (b

the direct supervisor (Cohen-Charash and

Spector 2001). Futhermore, according to

Cohen-Charash and Spector (2001), attitudi-

nal and affective reactions toward the orga-

BudiyantiandPatiro

234

nization were predicted by fairness models,

where procedural fairness predicted cognitive

reactions toward the organization, distribu-

tive fairness predicted affective and cogni-

tive reactions toward the outcomes (Cohen-

Charash and Spector 2001).

There is some research based on the

Mehrabian-Russell model, namely: Jang and

Namkung (2009), who undertook research to

address the lack of a comprehensive evalua-

tion of restaurants’ quality. Their study ex-

tends Mehrabian and Russell’s stimulus–or-

ganism–response framework by incorporat-

ing restaurant-specific stimuli and including

restaurant-specific measures of emotion. Lee

(2010) investigated how technology products’

attributes influence consumer responses. He

proposed a research model of consumers’ use

of technology products by applying the

Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) frame-

work (Mehrabian and Russell 1974) to sug-

gest that technology products’ attributes elicit

consumers’ cognitive (attitude) and affective

(pleasure and arousal) responses, leading to

their approach-avoidance behavior.

Ltifi and Gharbi (2012) studied the im-

pact of emotional states and the perceived

risk of remote purchasing on e-satisfaction

during Internet shopping, as well as the in-

fluence of e-satisfaction on e-loyalty. Kim and

Lennon (2013) extended Mehrabian and

Russell’s stimulus-organism-response model

to include both external (i.e. reputation) and

internal sources of information (i.e. website

quality) as stimuli which affect consumers’

response systems. Therefore, the purpose of

their paper was to test a more comprehen-

sive model consisting of reputation and

website quality (stimuli), cognition and emo-

tion (organism) and purchase intention (re-

sponse). Further, Chen et al. (2015) exam-

ined diners’ luxury restaurant consumption

behavior by incorporating diner expectations

into a modified Mehrabian–Russell model.

They argue that consumers dine at luxury res-

taurants for reasons beyond fulfilling their

basic needs.

The results from all this research shows

that the framework, based on the environ-

mental psychology model of Mehrabian and

Russell (1974), could be used to describe the

sources for the various environments as in-

puts/stimuli, and their effects on people’s

emotions and behavior. Accordingly, this re-

search considers fairness as an input of the

organization to predict affective and behav-

ior reactions toward outcomes (Cohen-

Charash and Spector 2001).

Service Fairness

For decades, fairness has been viewed

as a three-dimensional construct, comprised

of distributive fairness, procedural fairness,

and interactional fairness (Seiders and Berry

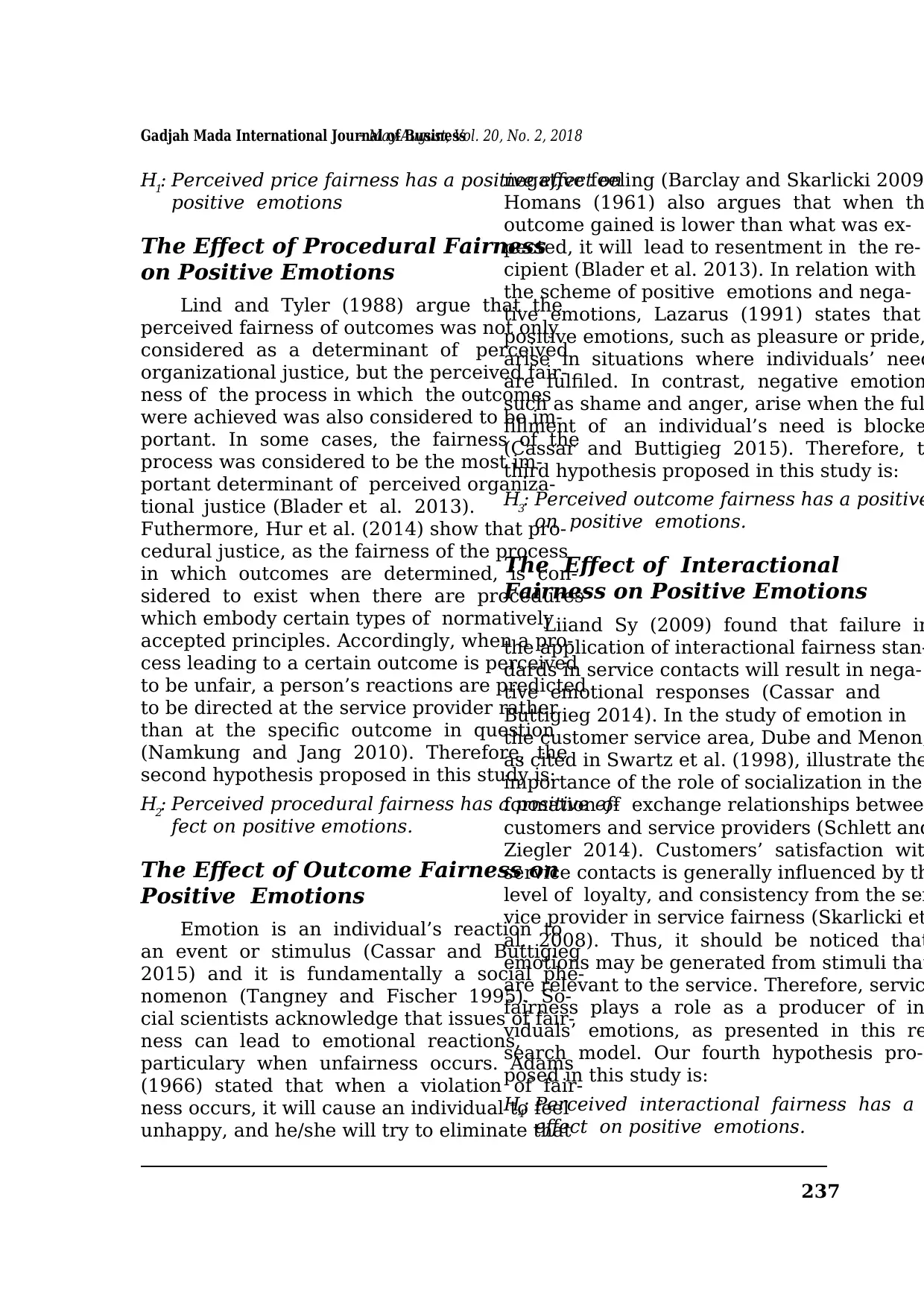

Emotional

Response

Positive

Emotion

Behavioral

Response

Behavioral

Intention

Stimulus

Fair ness

Figure 1. A Modified Mehrabian Russel Model

234

nization were predicted by fairness models,

where procedural fairness predicted cognitive

reactions toward the organization, distribu-

tive fairness predicted affective and cogni-

tive reactions toward the outcomes (Cohen-

Charash and Spector 2001).

There is some research based on the

Mehrabian-Russell model, namely: Jang and

Namkung (2009), who undertook research to

address the lack of a comprehensive evalua-

tion of restaurants’ quality. Their study ex-

tends Mehrabian and Russell’s stimulus–or-

ganism–response framework by incorporat-

ing restaurant-specific stimuli and including

restaurant-specific measures of emotion. Lee

(2010) investigated how technology products’

attributes influence consumer responses. He

proposed a research model of consumers’ use

of technology products by applying the

Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) frame-

work (Mehrabian and Russell 1974) to sug-

gest that technology products’ attributes elicit

consumers’ cognitive (attitude) and affective

(pleasure and arousal) responses, leading to

their approach-avoidance behavior.

Ltifi and Gharbi (2012) studied the im-

pact of emotional states and the perceived

risk of remote purchasing on e-satisfaction

during Internet shopping, as well as the in-

fluence of e-satisfaction on e-loyalty. Kim and

Lennon (2013) extended Mehrabian and

Russell’s stimulus-organism-response model

to include both external (i.e. reputation) and

internal sources of information (i.e. website

quality) as stimuli which affect consumers’

response systems. Therefore, the purpose of

their paper was to test a more comprehen-

sive model consisting of reputation and

website quality (stimuli), cognition and emo-

tion (organism) and purchase intention (re-

sponse). Further, Chen et al. (2015) exam-

ined diners’ luxury restaurant consumption

behavior by incorporating diner expectations

into a modified Mehrabian–Russell model.

They argue that consumers dine at luxury res-

taurants for reasons beyond fulfilling their

basic needs.

The results from all this research shows

that the framework, based on the environ-

mental psychology model of Mehrabian and

Russell (1974), could be used to describe the

sources for the various environments as in-

puts/stimuli, and their effects on people’s

emotions and behavior. Accordingly, this re-

search considers fairness as an input of the

organization to predict affective and behav-

ior reactions toward outcomes (Cohen-

Charash and Spector 2001).

Service Fairness

For decades, fairness has been viewed

as a three-dimensional construct, comprised

of distributive fairness, procedural fairness,

and interactional fairness (Seiders and Berry

Emotional

Response

Positive

Emotion

Behavioral

Response

Behavioral

Intention

Stimulus

Fair ness

Figure 1. A Modified Mehrabian Russel Model

235

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

1998; Cropanzano et al. 2008; Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Hur et al. 2014). Although the

principles of fairness developed in social psy-

chology may be useful in the contexts for

which they are developed, they may have

limitations when applied to specific con-

sumption situations. For example, Deutsch

(1985) criticizes the measurement capabili-

ties of the original theory of fairness, because

it is difficult for consumers to assess the in-

put and output values at the same time. Chou

et al. (2009) in their study also argued that

when equity is accounted for in the process

of changing inputs into outputs, with a cer-

tain outcome for a customer, it will create

problems with the operationalization of fair-

ness itself. Since there are conflicting views

about the dimensions of fairness, a consen-

sus is growing that the perception of fairness

is a dependent context, which is not only ap-

propriate for the service failure situation, but

it may also be applied in other situations

(Azar and Darvishi 2011; Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Blader et al. 2013).

According to Seiders and Berry (1998),

restaurant patrons who are dissatisfied with

the food served to them, due to its poor qual-

ity, which they believe is not equivalent with

the price they are paying, will question the

distributive fairness of the transaction. If

these patrons are kept waiting for a table de-

spite having a reservation, and also for food

and beverage service (once seated), they will

question the procedural fairness. Moreover,

if they experience insulting treatment or a

disrespectful attitude from the service staff,

they will also question the interactional fair-

ness. From the perspective of the customers’

sacrifice in consuming the product or service,

the price to be paid (price fairness) and time

spent (procedural fairness) are substantial

factors (Seiders and Berry 1998). In general,

price will appear in any situation, and in par-

ticular it is the magnitude of the econom

costs sacrificed in any transactions. Thus,

price fairness is defined as the customers

assessment of the difference between wha

they expect to receive and what they actually

receive (Kahneman et al. 1986). That is, con-

sumers generally have internal standards set

for the actual price, and compliance with

these standards will be verified when a judg-

ment is made as to whether it is equitable or

not.

The perception of fairness is the judg-

ment of whether or not customers accept an

outcome and/or a transaction process as be-

ing reasonable, acceptable, and just (Heo an

Lee 2011; Su et al. 2015; Su et al. 2016). Sin

assessments of price fairness are subjective

some studies have focused on consumers’

perceptions regarding relative prices (Haw

and Bearden 2006; Gielissen et al. 2008; Xia

et al. 2004). A study by Homburg et al. (2014

shows that the price stated in the menu may

be assessed differently by a customer, depen

ing on the stimulus (stimuli) provided by the

restaurant. Daskalopoulou (2008) found evi-

dence that a price’s fairness perception i

based on the acceptance level of the ind

vidual and the prevailing social standards. Th

concept of price in this study is different from

the concept of price from previous studies,

which stated that prices are fixed and abso-

lute (Kukar-Kinney et al. 2007). Thus, to

expand the understanding of consumers’ per

ceptions of prices’ fairness, this study pro

poses that the definition of price fairness is

the assessment of the overall consumers’

price based on a comparison between the

actual price and the acceptable price, accord

ing to social standards and conformance lev-

els (Homburg et al. 2014).

As one of the aspects of customers’

sacrifices, time is viewed as a limited resourc

(Croonen 2010; Liang et al. 2017; Chun et

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

1998; Cropanzano et al. 2008; Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Hur et al. 2014). Although the

principles of fairness developed in social psy-

chology may be useful in the contexts for

which they are developed, they may have

limitations when applied to specific con-

sumption situations. For example, Deutsch

(1985) criticizes the measurement capabili-

ties of the original theory of fairness, because

it is difficult for consumers to assess the in-

put and output values at the same time. Chou

et al. (2009) in their study also argued that

when equity is accounted for in the process

of changing inputs into outputs, with a cer-

tain outcome for a customer, it will create

problems with the operationalization of fair-

ness itself. Since there are conflicting views

about the dimensions of fairness, a consen-

sus is growing that the perception of fairness

is a dependent context, which is not only ap-

propriate for the service failure situation, but

it may also be applied in other situations

(Azar and Darvishi 2011; Aggarwal and

Larrick 2012; Blader et al. 2013).

According to Seiders and Berry (1998),

restaurant patrons who are dissatisfied with

the food served to them, due to its poor qual-

ity, which they believe is not equivalent with

the price they are paying, will question the

distributive fairness of the transaction. If

these patrons are kept waiting for a table de-

spite having a reservation, and also for food

and beverage service (once seated), they will

question the procedural fairness. Moreover,

if they experience insulting treatment or a

disrespectful attitude from the service staff,

they will also question the interactional fair-

ness. From the perspective of the customers’

sacrifice in consuming the product or service,

the price to be paid (price fairness) and time

spent (procedural fairness) are substantial

factors (Seiders and Berry 1998). In general,

price will appear in any situation, and in par-

ticular it is the magnitude of the econom

costs sacrificed in any transactions. Thus,

price fairness is defined as the customers

assessment of the difference between wha

they expect to receive and what they actually

receive (Kahneman et al. 1986). That is, con-

sumers generally have internal standards set

for the actual price, and compliance with

these standards will be verified when a judg-

ment is made as to whether it is equitable or

not.

The perception of fairness is the judg-

ment of whether or not customers accept an

outcome and/or a transaction process as be-

ing reasonable, acceptable, and just (Heo an

Lee 2011; Su et al. 2015; Su et al. 2016). Sin

assessments of price fairness are subjective

some studies have focused on consumers’

perceptions regarding relative prices (Haw

and Bearden 2006; Gielissen et al. 2008; Xia

et al. 2004). A study by Homburg et al. (2014

shows that the price stated in the menu may

be assessed differently by a customer, depen

ing on the stimulus (stimuli) provided by the

restaurant. Daskalopoulou (2008) found evi-

dence that a price’s fairness perception i

based on the acceptance level of the ind

vidual and the prevailing social standards. Th

concept of price in this study is different from

the concept of price from previous studies,

which stated that prices are fixed and abso-

lute (Kukar-Kinney et al. 2007). Thus, to

expand the understanding of consumers’ per

ceptions of prices’ fairness, this study pro

poses that the definition of price fairness is

the assessment of the overall consumers’

price based on a comparison between the

actual price and the acceptable price, accord

ing to social standards and conformance lev-

els (Homburg et al. 2014).

As one of the aspects of customers’

sacrifices, time is viewed as a limited resourc

(Croonen 2010; Liang et al. 2017; Chun et

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

BudiyantiandPatiro

236

al. 2018). Customers’ evaluations toward the

waiting process are not only altered objec-

tively but also subjectively (Azarand Darvishi

2011). When there are two customers who

assess time differently, but who are kept wait-

ing for the same duration, they will differ in

paying for the services they receieved (Blader

et al. 2013). In restaurants, the waiting time

derives from conditions which require extra

time, such as service preparation (i.e. how to

serve the food) or a level of demand beyond

the system’s capacity (i.e. customers arrive

when the requirement for service already ex-

ceeds the providers ability to accomodate it).

Thus, with regard to this discussion, the con-

cept of procedural fairness can be defined as

the accuracy of time and the efficiency of

the service system as a part of the custom-

ers’ sacrifice, since waiting time and delayed

service are categorized as drawbacks.

On its relationship with the benefits

perceived by customers, studies into fairness

show that fairness behavior, as demonstrated

by the service provider, is not only impor-

tant for the instrumental aspect, but also im-

portant for the relational aspe ct

(Namasivayam2004; Croonen 2010;

Azarand Darvishi 2011). Thus, service evalu-

ations by customers do not only come from

fairness, regarding the tangible outcome of

fairness, but also from the intagible outcome

of fairness, which is interactional fairness

(Hur et al. 2014). According to Gronroos

(2007) providing exceptional products and

service is one of the main interests of the

service business. However, he argues that

fairness regarding the perceived outcome of

fairness will affect the emotions of the cus-

tomers, and their behavioral intentions.

Furthermore, in restaurants there are

some human intearctions. Lee et al. (2013)

and Hur et al. (2014) define a service con-

tact as a period of time where customers di-

rectly interact with the service. The service

contact is the critical moment of truth when

customers often attain unforgettable impres-

sions concerning a business (Lee et al. 2013;

Hur et al. 2014). This condition only lasts

for a few minutes, and may satisfy the cus-

tomers, or frustrate them (Liang and Zhang

2011). Therefore, interactional fairness in this

study refers to the interest and respect shown

by service providers to customers, and as a

result, customers will feel that they are

treated fairly during the interaction (Aggarwal

and Larrick 2012). Thus, in general, our study

develops a model of fairness services con-

sisting of four variables of fairness, namely:

Price fairness, procedural fairness, outcome

fairness, and interactional fairness, all of

which will be tested empirically in the con-

text of restaurant service, specifically fast-

food chain restaurants.

The Effect of Price Fairness on

Positive Emotions

Positive and negative emotions felt dur-

ing the process of fairness may be character-

ized in various ways; they may stand alone

(positive or negative) or as a whole (positive

and negative); or they are experienced or ex-

pressed (Heo and Lee 2011; Lee et al. 2013).

Some studies of fairness also use the emo-

tional approach in isolation, which shows that

the perception of price unfairness is associ-

ated with feelings of disappointment or an-

ger (Xia et al. 2004; Xiaand Monroe 2010).

Similarly, in the study of social fairness, the

effect of procedural fairness on separated

emotional responses describes emotions of

happiness in the form of happiness, joy, and

feelings of pride, along with emotions of sad-

ness in the form of disappointment, anger,

and frustration (Barclay et al. 2005; Blader

et al. 2013). Based on the descriptions above,

the first hypothesis proposed in this study is:

236

al. 2018). Customers’ evaluations toward the

waiting process are not only altered objec-

tively but also subjectively (Azarand Darvishi

2011). When there are two customers who

assess time differently, but who are kept wait-

ing for the same duration, they will differ in

paying for the services they receieved (Blader

et al. 2013). In restaurants, the waiting time

derives from conditions which require extra

time, such as service preparation (i.e. how to

serve the food) or a level of demand beyond

the system’s capacity (i.e. customers arrive

when the requirement for service already ex-

ceeds the providers ability to accomodate it).

Thus, with regard to this discussion, the con-

cept of procedural fairness can be defined as

the accuracy of time and the efficiency of

the service system as a part of the custom-

ers’ sacrifice, since waiting time and delayed

service are categorized as drawbacks.

On its relationship with the benefits

perceived by customers, studies into fairness

show that fairness behavior, as demonstrated

by the service provider, is not only impor-

tant for the instrumental aspect, but also im-

portant for the relational aspe ct

(Namasivayam2004; Croonen 2010;

Azarand Darvishi 2011). Thus, service evalu-

ations by customers do not only come from

fairness, regarding the tangible outcome of

fairness, but also from the intagible outcome

of fairness, which is interactional fairness

(Hur et al. 2014). According to Gronroos

(2007) providing exceptional products and

service is one of the main interests of the

service business. However, he argues that

fairness regarding the perceived outcome of

fairness will affect the emotions of the cus-

tomers, and their behavioral intentions.

Furthermore, in restaurants there are

some human intearctions. Lee et al. (2013)

and Hur et al. (2014) define a service con-

tact as a period of time where customers di-

rectly interact with the service. The service

contact is the critical moment of truth when

customers often attain unforgettable impres-

sions concerning a business (Lee et al. 2013;

Hur et al. 2014). This condition only lasts

for a few minutes, and may satisfy the cus-

tomers, or frustrate them (Liang and Zhang

2011). Therefore, interactional fairness in this

study refers to the interest and respect shown

by service providers to customers, and as a

result, customers will feel that they are

treated fairly during the interaction (Aggarwal

and Larrick 2012). Thus, in general, our study

develops a model of fairness services con-

sisting of four variables of fairness, namely:

Price fairness, procedural fairness, outcome

fairness, and interactional fairness, all of

which will be tested empirically in the con-

text of restaurant service, specifically fast-

food chain restaurants.

The Effect of Price Fairness on

Positive Emotions

Positive and negative emotions felt dur-

ing the process of fairness may be character-

ized in various ways; they may stand alone

(positive or negative) or as a whole (positive

and negative); or they are experienced or ex-

pressed (Heo and Lee 2011; Lee et al. 2013).

Some studies of fairness also use the emo-

tional approach in isolation, which shows that

the perception of price unfairness is associ-

ated with feelings of disappointment or an-

ger (Xia et al. 2004; Xiaand Monroe 2010).

Similarly, in the study of social fairness, the

effect of procedural fairness on separated

emotional responses describes emotions of

happiness in the form of happiness, joy, and

feelings of pride, along with emotions of sad-

ness in the form of disappointment, anger,

and frustration (Barclay et al. 2005; Blader

et al. 2013). Based on the descriptions above,

the first hypothesis proposed in this study is:

237

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

H1: Perceived price fairness has a positive effect on

positive emotions

The Effect of Procedural Fairness

on Positive Emotions

Lind and Tyler (1988) argue that the

perceived fairness of outcomes was not only

considered as a determinant of perceived

organizational justice, but the perceived fair-

ness of the process in which the outcomes

were achieved was also considered to be im-

portant. In some cases, the fairness of the

process was considered to be the most im-

portant determinant of perceived organiza-

tional justice (Blader et al. 2013).

Futhermore, Hur et al. (2014) show that pro-

cedural justice, as the fairness of the process

in which outcomes are determined, is con-

sidered to exist when there are procedures

which embody certain types of normatively

accepted principles. Accordingly, when a pro-

cess leading to a certain outcome is perceived

to be unfair, a person’s reactions are predicted

to be directed at the service provider rather

than at the specific outcome in question

(Namkung and Jang 2010). Therefore, the

second hypothesis proposed in this study is:

H2: Perceived procedural fairness has a positive ef-

fect on positive emotions.

The Effect of Outcome Fairness on

Positive Emotions

Emotion is an individual’s reaction to

an event or stimulus (Cassar and Buttigieg

2015) and it is fundamentally a social phe-

nomenon (Tangney and Fischer 1995). So-

cial scientists acknowledge that issues of fair-

ness can lead to emotional reactions,

particulary when unfairness occurs. Adams

(1966) stated that when a violation of fair-

ness occurs, it will cause an individual to feel

unhappy, and he/she will try to eliminate that

negative feeling (Barclay and Skarlicki 2009

Homans (1961) also argues that when th

outcome gained is lower than what was ex-

pected, it will lead to resentment in the re-

cipient (Blader et al. 2013). In relation with

the scheme of positive emotions and nega-

tive emotions, Lazarus (1991) states that

positive emotions, such as pleasure or pride,

arise in situations where individuals’ need

are fulfiled. In contrast, negative emotion

such as shame and anger, arise when the ful

fillment of an individual’s need is blocke

(Cassar and Buttigieg 2015). Therefore, t

third hypothesis proposed in this study is:

H3: Perceived outcome fairness has a positive

on positive emotions.

The Effect of Interactional

Fairness on Positive Emotions

Liiand Sy (2009) found that failure in

the application of interactional fairness stan-

dards in service contacts will result in nega-

tive emotional responses (Cassar and

Buttigieg 2014). In the study of emotion in

the customer service area, Dube and Menon,

as cited in Swartz et al. (1998), illustrate the

importance of the role of socialization in the

formation of exchange relationships betwee

customers and service providers (Schlett and

Ziegler 2014). Customers’ satisfaction wit

service contacts is generally influenced by th

level of loyalty, and consistency from the ser

vice provider in service fairness (Skarlicki et

al. 2008). Thus, it should be noticed that

emotions may be generated from stimuli that

are relevant to the service. Therefore, servic

fairness plays a role as a producer of in

viduals’ emotions, as presented in this re

search model. Our fourth hypothesis pro-

posed in this study is:

H4: Perceived interactional fairness has a

effect on positive emotions.

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

H1: Perceived price fairness has a positive effect on

positive emotions

The Effect of Procedural Fairness

on Positive Emotions

Lind and Tyler (1988) argue that the

perceived fairness of outcomes was not only

considered as a determinant of perceived

organizational justice, but the perceived fair-

ness of the process in which the outcomes

were achieved was also considered to be im-

portant. In some cases, the fairness of the

process was considered to be the most im-

portant determinant of perceived organiza-

tional justice (Blader et al. 2013).

Futhermore, Hur et al. (2014) show that pro-

cedural justice, as the fairness of the process

in which outcomes are determined, is con-

sidered to exist when there are procedures

which embody certain types of normatively

accepted principles. Accordingly, when a pro-

cess leading to a certain outcome is perceived

to be unfair, a person’s reactions are predicted

to be directed at the service provider rather

than at the specific outcome in question

(Namkung and Jang 2010). Therefore, the

second hypothesis proposed in this study is:

H2: Perceived procedural fairness has a positive ef-

fect on positive emotions.

The Effect of Outcome Fairness on

Positive Emotions

Emotion is an individual’s reaction to

an event or stimulus (Cassar and Buttigieg

2015) and it is fundamentally a social phe-

nomenon (Tangney and Fischer 1995). So-

cial scientists acknowledge that issues of fair-

ness can lead to emotional reactions,

particulary when unfairness occurs. Adams

(1966) stated that when a violation of fair-

ness occurs, it will cause an individual to feel

unhappy, and he/she will try to eliminate that

negative feeling (Barclay and Skarlicki 2009

Homans (1961) also argues that when th

outcome gained is lower than what was ex-

pected, it will lead to resentment in the re-

cipient (Blader et al. 2013). In relation with

the scheme of positive emotions and nega-

tive emotions, Lazarus (1991) states that

positive emotions, such as pleasure or pride,

arise in situations where individuals’ need

are fulfiled. In contrast, negative emotion

such as shame and anger, arise when the ful

fillment of an individual’s need is blocke

(Cassar and Buttigieg 2015). Therefore, t

third hypothesis proposed in this study is:

H3: Perceived outcome fairness has a positive

on positive emotions.

The Effect of Interactional

Fairness on Positive Emotions

Liiand Sy (2009) found that failure in

the application of interactional fairness stan-

dards in service contacts will result in nega-

tive emotional responses (Cassar and

Buttigieg 2014). In the study of emotion in

the customer service area, Dube and Menon,

as cited in Swartz et al. (1998), illustrate the

importance of the role of socialization in the

formation of exchange relationships betwee

customers and service providers (Schlett and

Ziegler 2014). Customers’ satisfaction wit

service contacts is generally influenced by th

level of loyalty, and consistency from the ser

vice provider in service fairness (Skarlicki et

al. 2008). Thus, it should be noticed that

emotions may be generated from stimuli that

are relevant to the service. Therefore, servic

fairness plays a role as a producer of in

viduals’ emotions, as presented in this re

search model. Our fourth hypothesis pro-

posed in this study is:

H4: Perceived interactional fairness has a

effect on positive emotions.

BudiyantiandPatiro

238

Behavioral Intention

Modification of the relationship be-

tween a stimulus and its emotional response

will lead to consumer behavior. Zaltman et

al., as cited in Hunt (1978), examined con-

sumers’ behavior when faced with unfair

marketing practices at different stages,

namely at the stage prior to purchase; the time

of purchase; and the time after the purchase

(Skarlicki et al. 2008). Their study shows that

an increase in the awareness of unfair prac-

tices and fraud will increase the tendency of

consumers to complain (Skarlicki et al. 2008).

White et al. (2012) proposed a model of con-

sumers’ complaint behavior and concluded

that perceived fairness influenced the con-

sumers grumbling, word-of-mouth opinion,

and patronage behavior. The patronage be-

havior is measure with the intention to stay

and intention to deliver positive opinions of

the products to family, friends, and colleagues.

This behavior have the ability to predict con-

sumer purchase behavior and Customer’s fair-

ness perceptions are key driver of this be-

havior (White et al. 2012). Behavioral inten-

tion is defined as the rate at which individu-

als consciously want to display or not display

certain behaviors in the future (Tzafrirand

Hareli 2009; Fishbeinand Ajzen 2010; White

et al. 2012). Therefore, the intention to be-

have is a proxy for certain behaviors

(Fishbein and Ajzen 2010). Thus, this study

also applied the intention to behave as a con-

struct of the perceived result, where the in-

tention to behave is influence by positive

emotions.

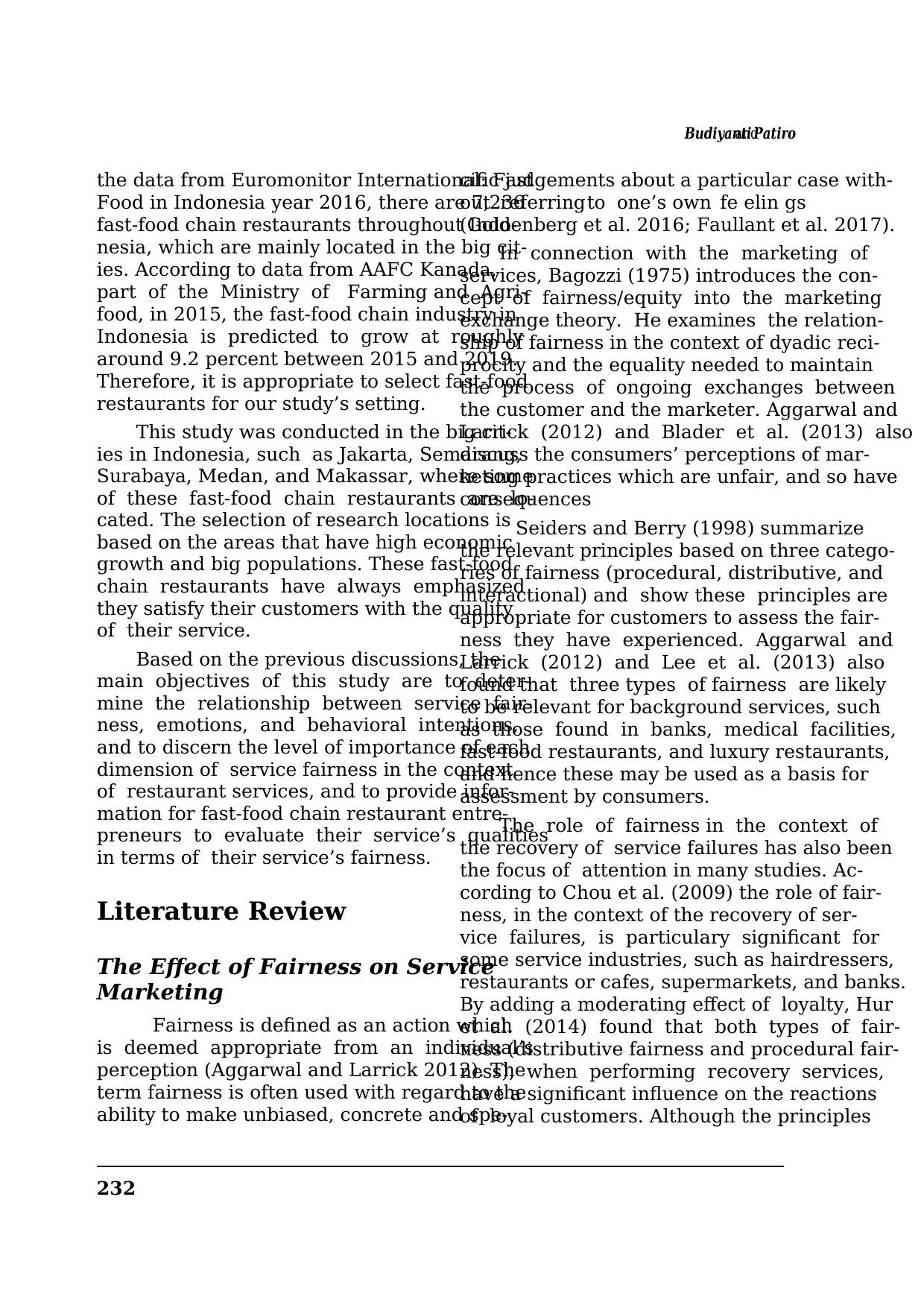

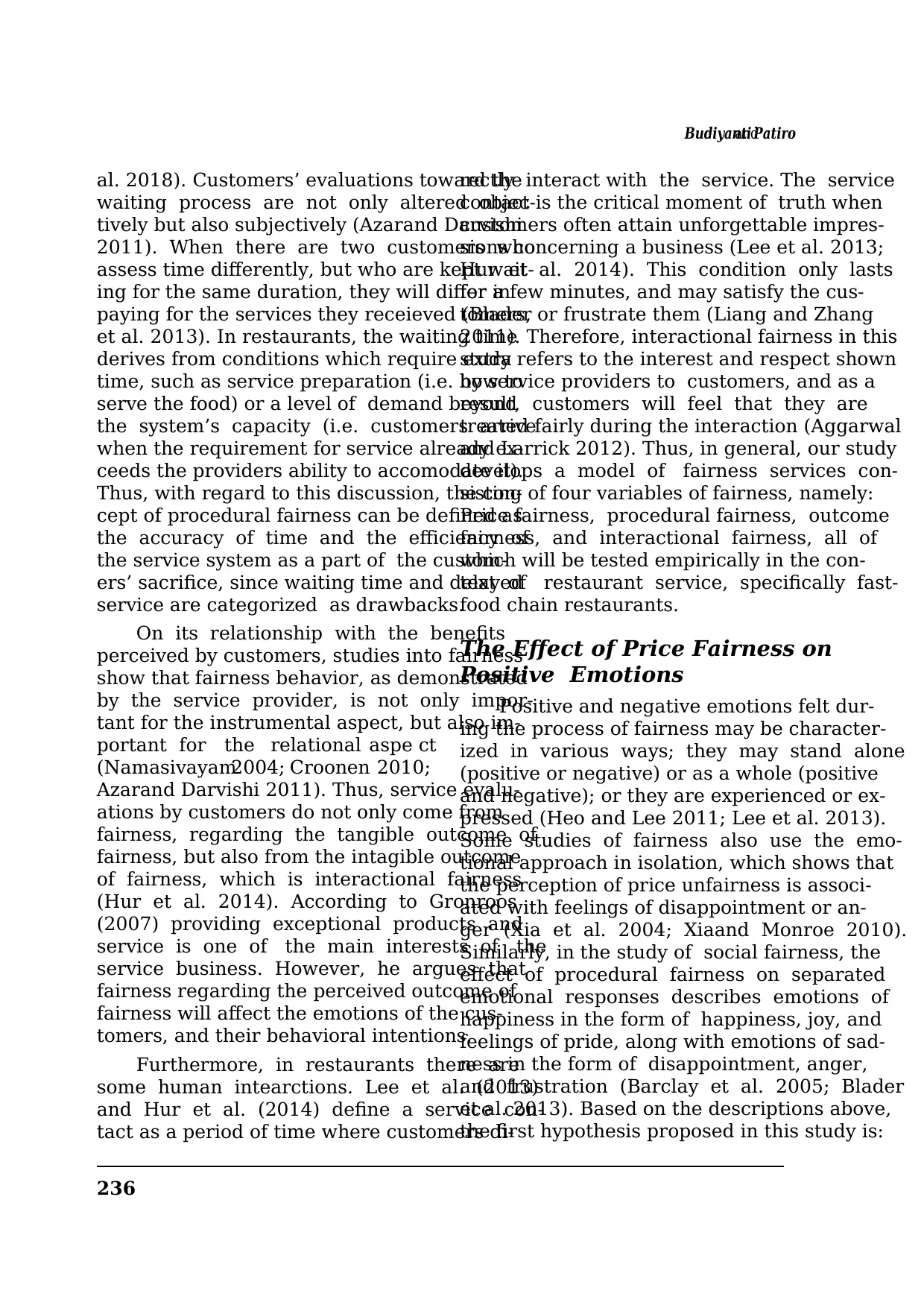

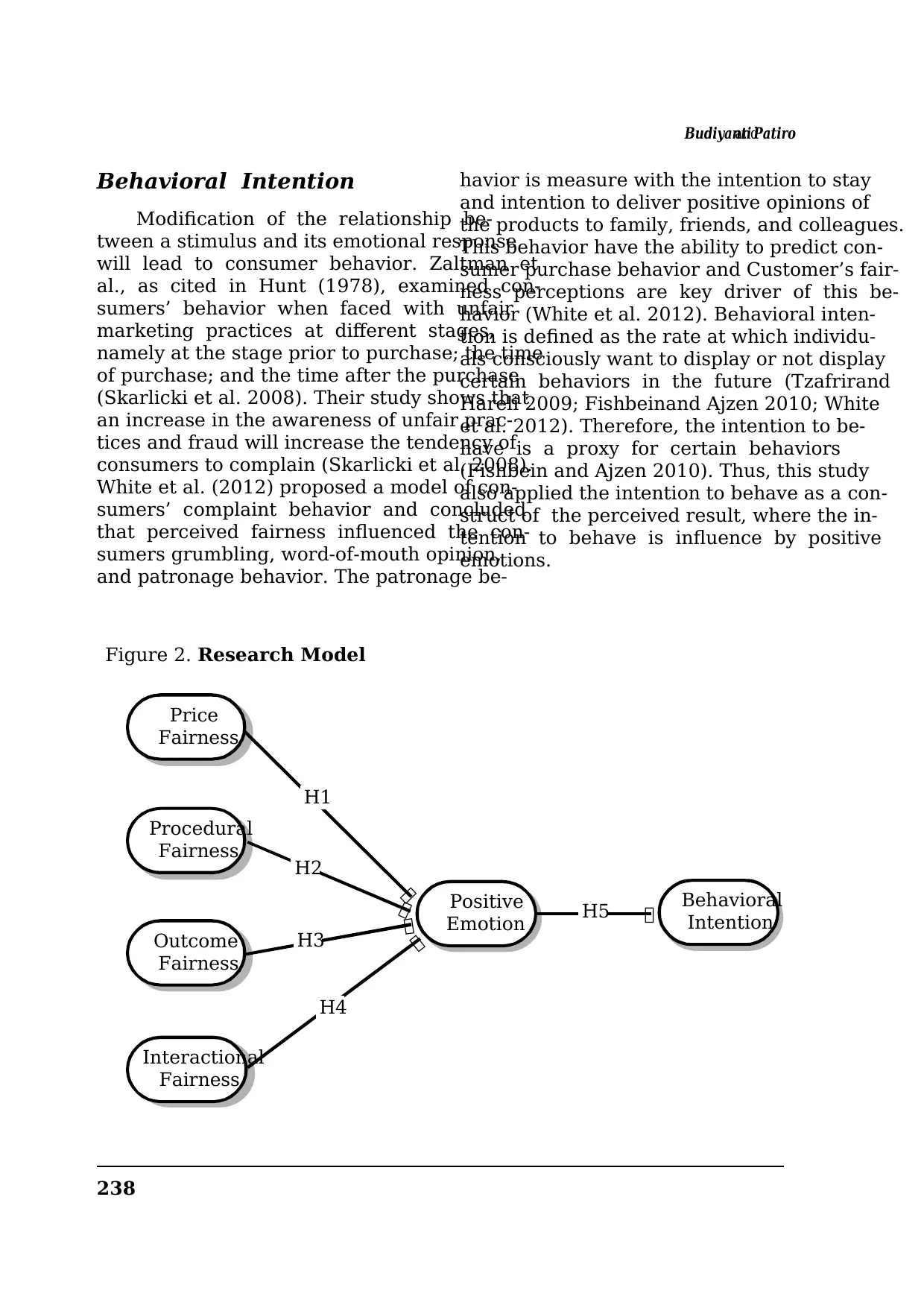

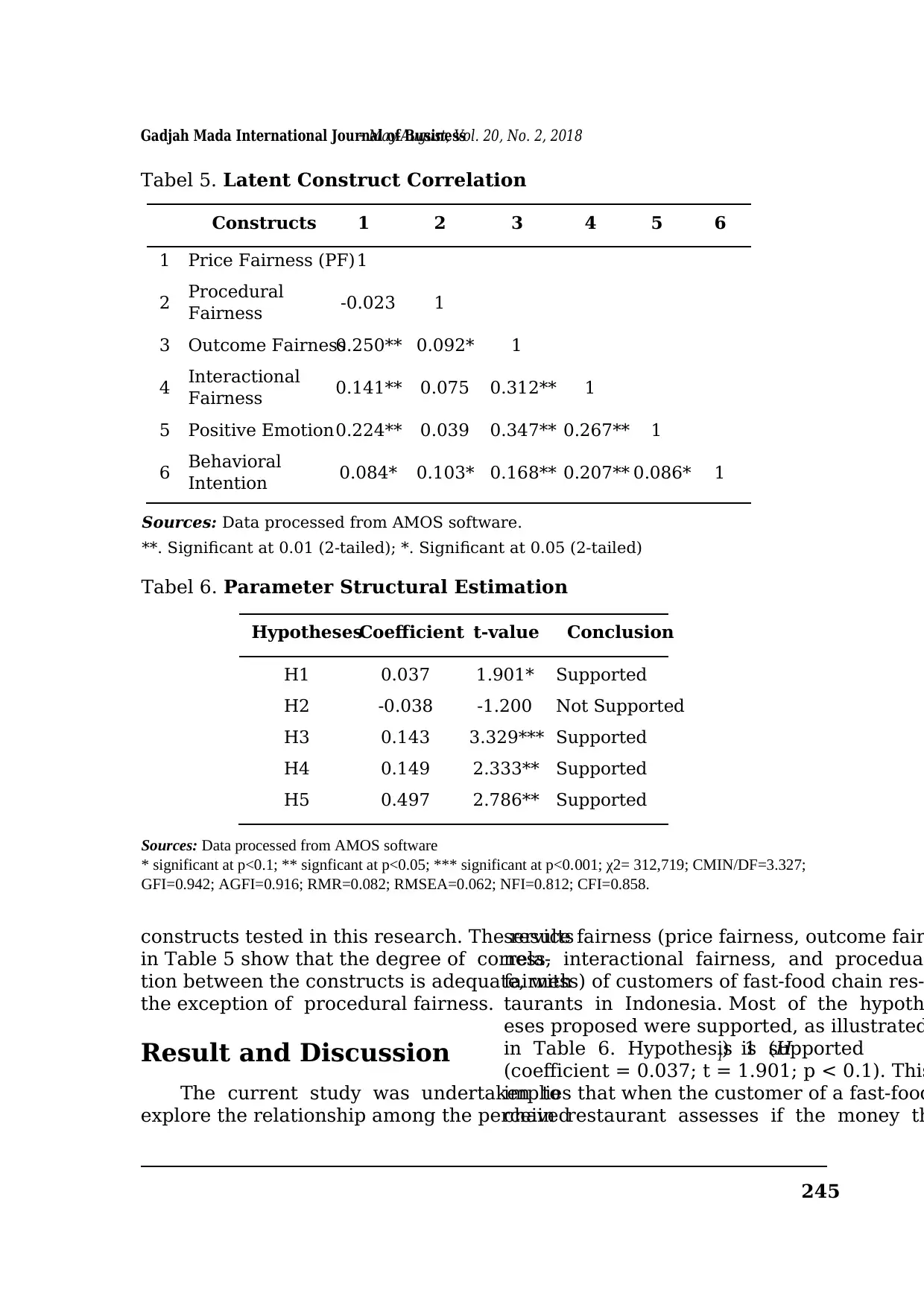

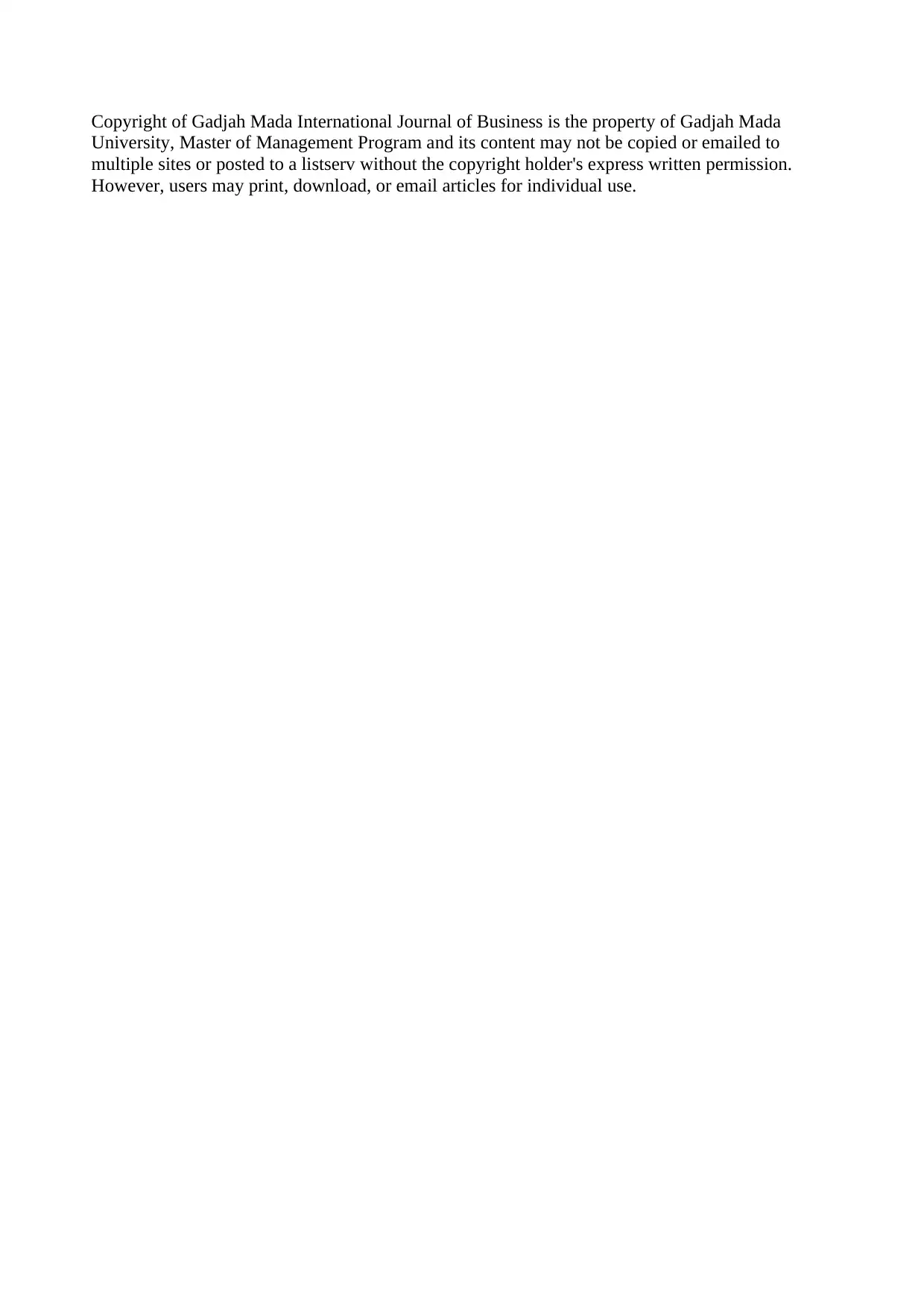

Figure 2. Research Model

Procedural

Fairness

Price

Fairness

Outcome

Fairness

Interactional

Fairness

Positive

Emotion

Behavioral

Intention

H1

H2

H3

H4

H5

238

Behavioral Intention

Modification of the relationship be-

tween a stimulus and its emotional response

will lead to consumer behavior. Zaltman et

al., as cited in Hunt (1978), examined con-

sumers’ behavior when faced with unfair

marketing practices at different stages,

namely at the stage prior to purchase; the time

of purchase; and the time after the purchase

(Skarlicki et al. 2008). Their study shows that

an increase in the awareness of unfair prac-

tices and fraud will increase the tendency of

consumers to complain (Skarlicki et al. 2008).

White et al. (2012) proposed a model of con-

sumers’ complaint behavior and concluded

that perceived fairness influenced the con-

sumers grumbling, word-of-mouth opinion,

and patronage behavior. The patronage be-

havior is measure with the intention to stay

and intention to deliver positive opinions of

the products to family, friends, and colleagues.

This behavior have the ability to predict con-

sumer purchase behavior and Customer’s fair-

ness perceptions are key driver of this be-

havior (White et al. 2012). Behavioral inten-

tion is defined as the rate at which individu-

als consciously want to display or not display

certain behaviors in the future (Tzafrirand

Hareli 2009; Fishbeinand Ajzen 2010; White

et al. 2012). Therefore, the intention to be-

have is a proxy for certain behaviors

(Fishbein and Ajzen 2010). Thus, this study

also applied the intention to behave as a con-

struct of the perceived result, where the in-

tention to behave is influence by positive

emotions.

Figure 2. Research Model

Procedural

Fairness

Price

Fairness

Outcome

Fairness

Interactional

Fairness

Positive

Emotion

Behavioral

Intention

H1

H2

H3

H4

H5

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

239

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

Emotions’ Influence on

Behavioral Intention

Numerous studies have shown that af-

fection is a significant factor in consumer

behavior (Yang and Chang 2008; Tzafrir and

Hareli 2009). The underlying concept of this

theory is people often make judgments con-

cerning external events based on their affec-

tive reactions that arise at that time. There-

fore, they use affection as the basis of their

assessment when they assess something they

like and are feeling happy (Williamson and

Williams 2011). Positive emotions (such as

joy, excitment, and happiness) have been rec-

ognized to have a consistent effect on an

individual’s behavior (Jangand Namkung

2009). When positive emotions are consis-

tent during service contacts, the expectation

is to be able to deliver a good experience for

the consumer (Tu 2004). Associated with

perceived fairness, people will use positive

emotions to evaluate their assessment of their

preferred service company (Nguyenand

Klaus 2013). Furthermore, they will be will-

ing to spread a positive opinion of the com-

pany by word-of-mouth to other people or to

re-visit their preferred service company

(Nguyen and Klaus 2013). As stated by

Adams (1966), the negative feelings result-

ing from unfairness are an emotional state-

ment to restore the sense of fairness (Jangand

Namkung 2009; Namkung and Jang 2010).

Thus, the fifth hypothesis proposed by this

study is:

H5: Positive emotions have a positive influence on

the customer’s behavioral intentions.

The hypotheses in this study can be visual-

ized as in Figure 2.

Methods

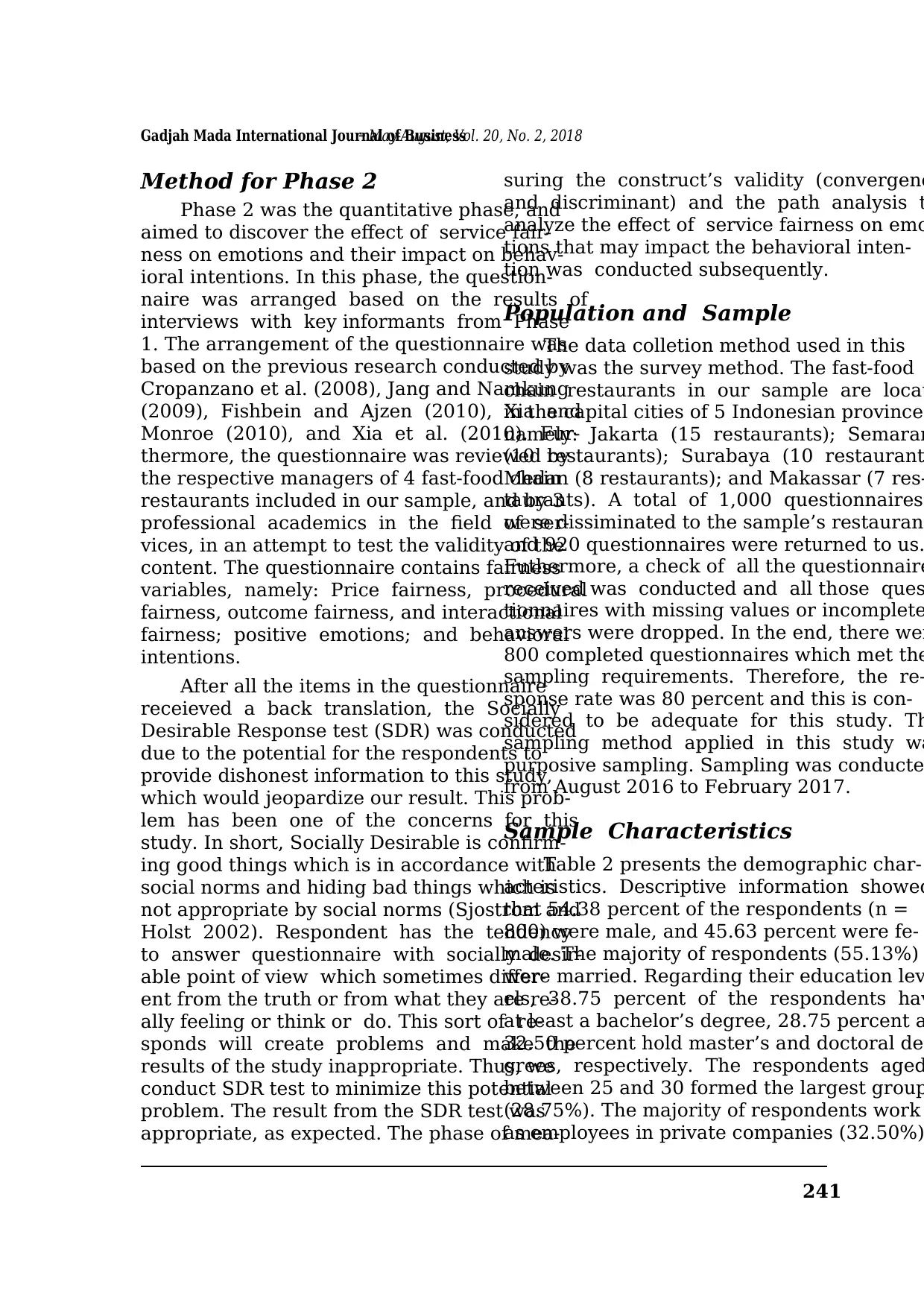

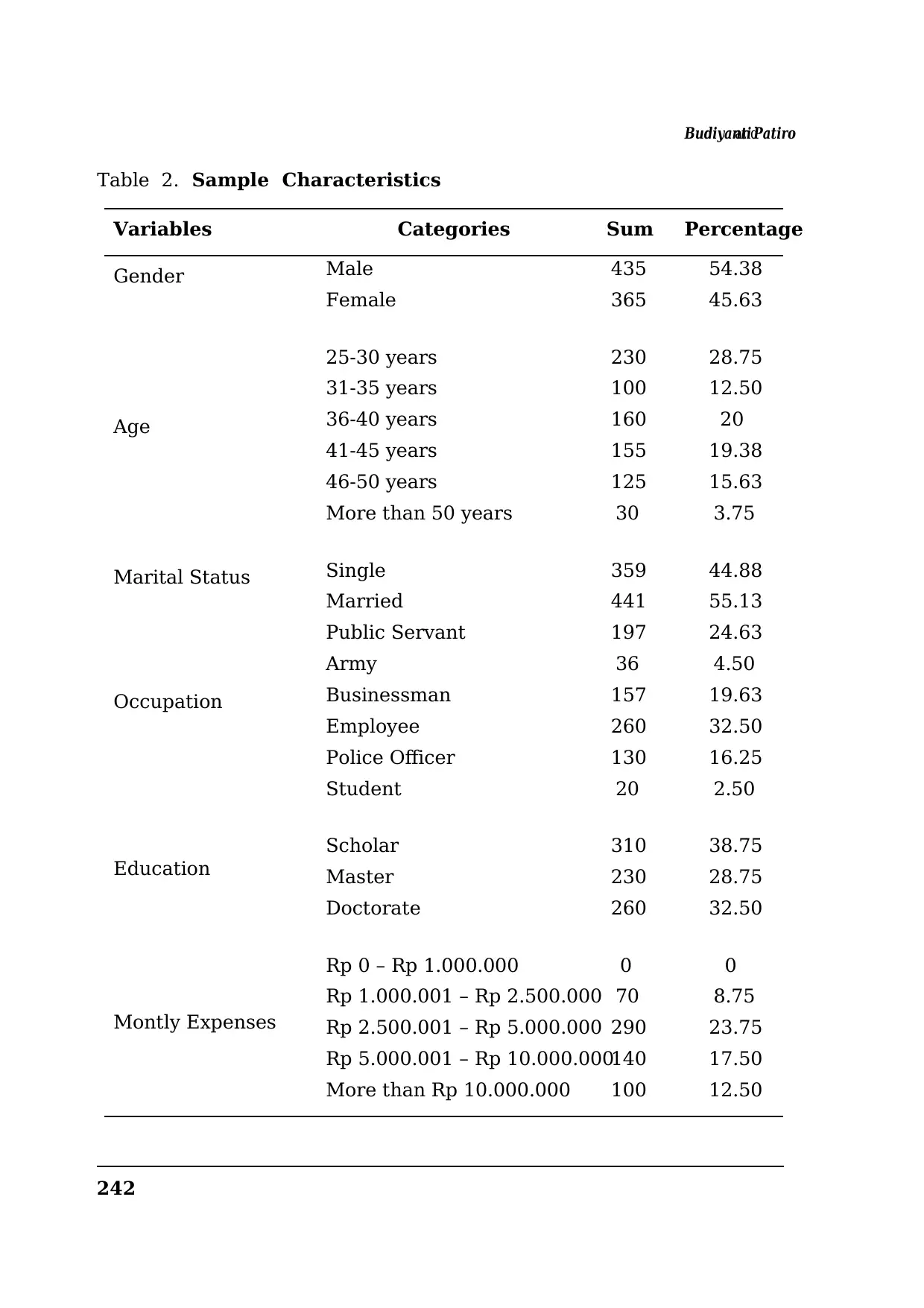

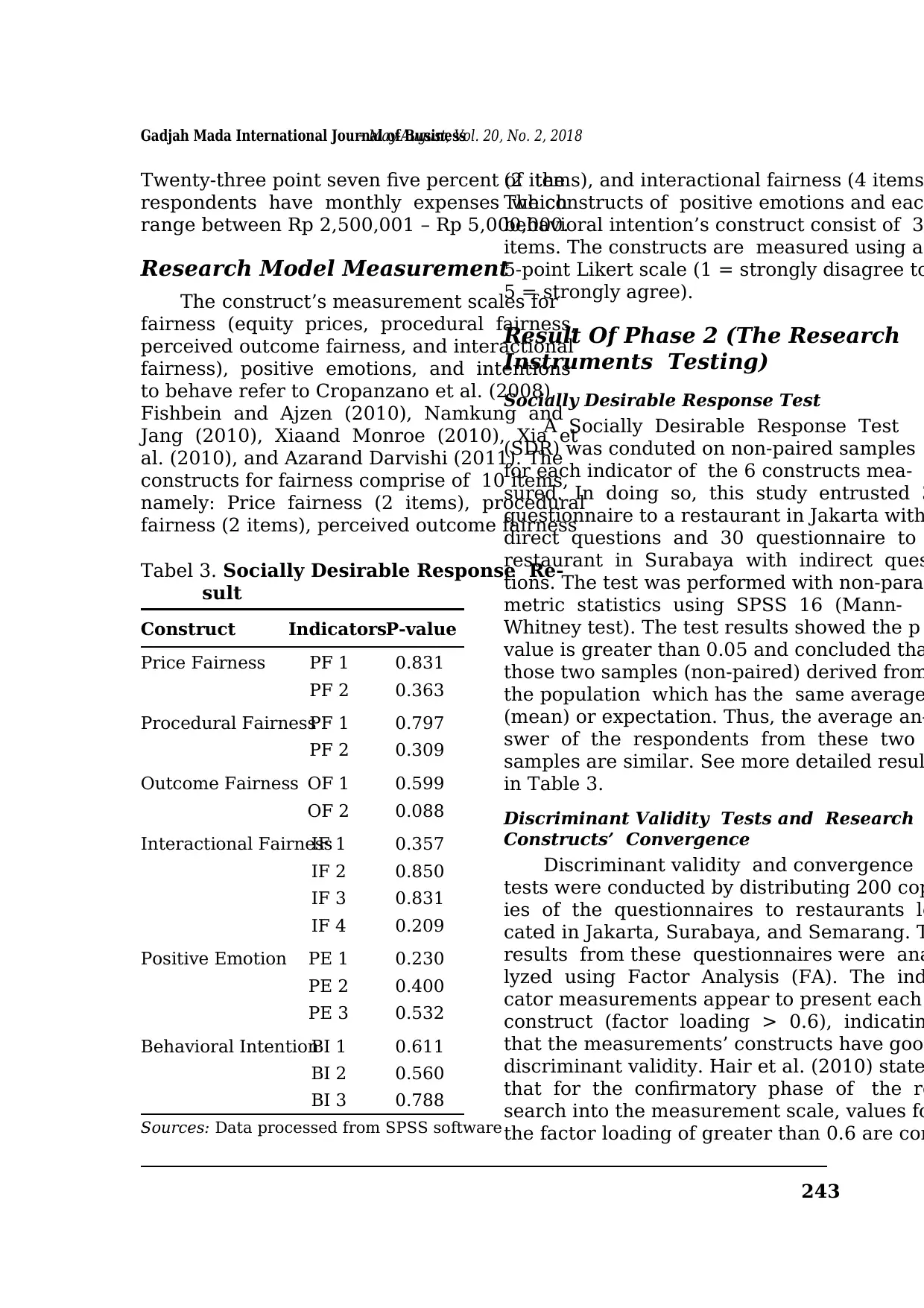

Method of Phase 1

This study consists of two phases,

namely: Phase 1 which is the qualitative

phase, and Phase 2 the quantitative phas

In Phase 1, the researchers conduct an e

planatory study. This stage aims to determin

the form of the percieved fairness felt b

customers of fast-food chain retaurants, and

the positive emotions that are formed when

someone perceives the fairness, and their

behavioral intention in the future related to

their preference for fast-food chain restau

rants.

The first step was to conduct a prelimi-

nary interview with customers of fast-food

chain restaurants located in the capital cities

of 2 Indonesian provinces, namely Jakarta (3

restaurants) and Surabaya (2 restaurants). T

number of customers selected for these ini-

tial interviews were 15 customers from each

restaurant. The determination of the custom

ers to be interviewed at this stage was based

on the following considerations: (1) They

were eating in the restaurant; and (2) they w

willing to engage in the research. In addition

to these preliminary interviews, the custom-

ers were also asked to write down on a piece

of paper how often they ate there, what im-

pressions they have regarding the service pr

vided when they are eating at the restaurant

and why they chose to eat at that restaurant.

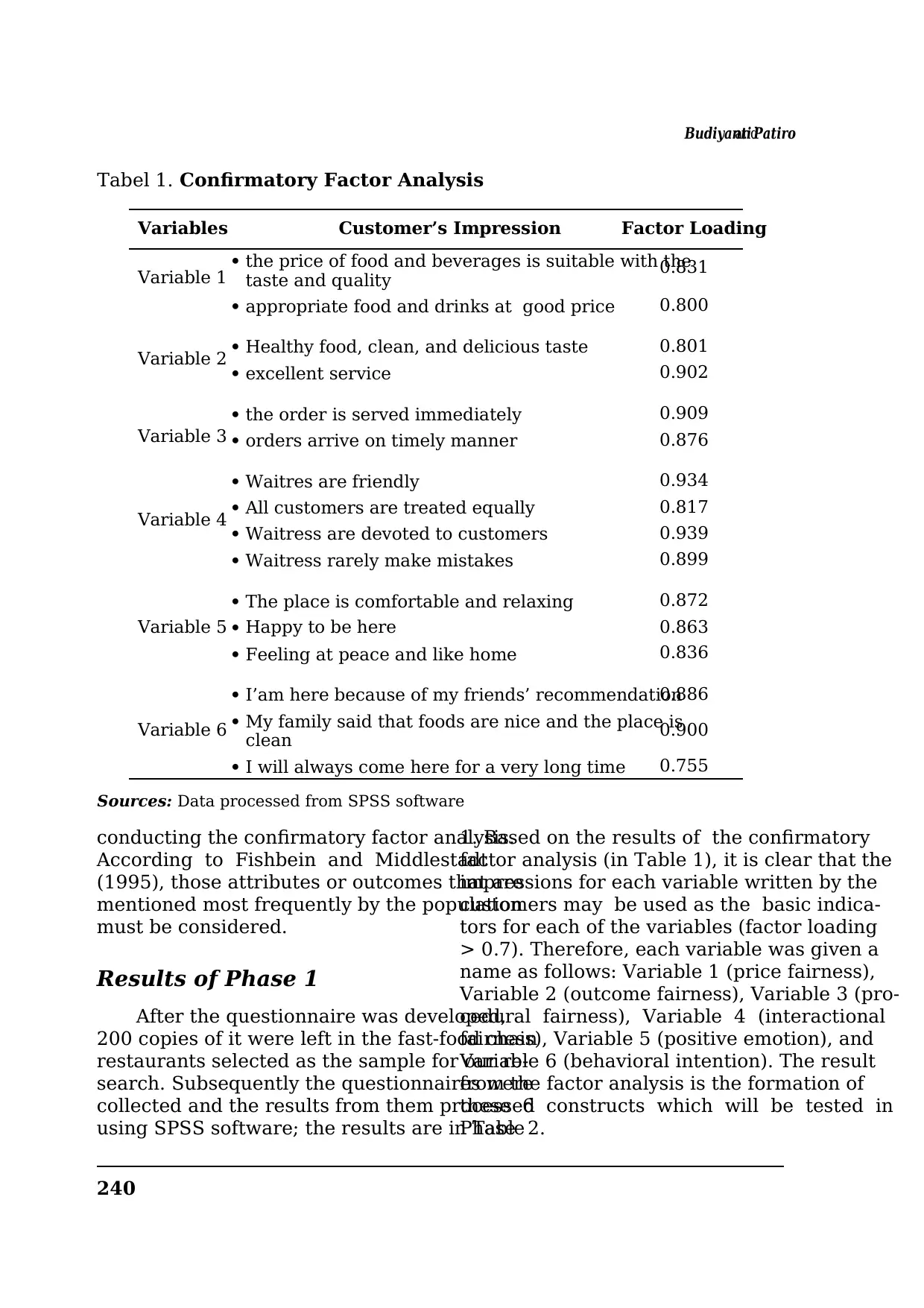

From these interviews, the items men-

tioned by at least 10 percent of the respon-

dents (Fishbein and Middlestadt 1995) were

considered to be essential factors in the de-

velopment of a questionnaire to be use for

Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business– May-August, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2018

Emotions’ Influence on

Behavioral Intention

Numerous studies have shown that af-

fection is a significant factor in consumer

behavior (Yang and Chang 2008; Tzafrir and

Hareli 2009). The underlying concept of this

theory is people often make judgments con-

cerning external events based on their affec-

tive reactions that arise at that time. There-

fore, they use affection as the basis of their

assessment when they assess something they

like and are feeling happy (Williamson and

Williams 2011). Positive emotions (such as

joy, excitment, and happiness) have been rec-

ognized to have a consistent effect on an

individual’s behavior (Jangand Namkung

2009). When positive emotions are consis-

tent during service contacts, the expectation

is to be able to deliver a good experience for

the consumer (Tu 2004). Associated with

perceived fairness, people will use positive

emotions to evaluate their assessment of their

preferred service company (Nguyenand

Klaus 2013). Furthermore, they will be will-

ing to spread a positive opinion of the com-

pany by word-of-mouth to other people or to

re-visit their preferred service company

(Nguyen and Klaus 2013). As stated by

Adams (1966), the negative feelings result-

ing from unfairness are an emotional state-

ment to restore the sense of fairness (Jangand

Namkung 2009; Namkung and Jang 2010).

Thus, the fifth hypothesis proposed by this

study is:

H5: Positive emotions have a positive influence on

the customer’s behavioral intentions.

The hypotheses in this study can be visual-

ized as in Figure 2.

Methods