Gender and Public Space: Examining the Role of Gender Mainstreaming and the Right to City in Urban Planning

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/05

|26

|7671

|438

AI Summary

This article examines the role of gender mainstreaming and the right to city in urban planning, with a focus on creating gender-sensitive public spaces. It discusses key concepts such as equality, social protection, and feminist urbanism, and explores the challenges faced by women in cities. The article also provides recommendations for implementing a gender-sensitive design.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Gender and public space

Name of the student:

Name of the university:

Author note:

Gender and public space

Name of the student:

Name of the university:

Author note:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Table of Contents

1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................2

1.1 Key Concepts.........................................................................................................................3

2. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning....................................................................................4

3. Right to city.................................................................................................................................5

4. Gender and city............................................................................................................................6

4. 1 Creating gender sensitive and women friendly cities...........................................................8

4.2 Gender differences and transport.........................................................................................10

5. Gender and the neighborhood....................................................................................................11

5.1 Gender and parks.................................................................................................................13

7. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................15

7.1 Recommendations of Implementing a Gender-Sensitive Design........................................16

7. 2 Gaps in literature review.....................................................................................................16

References:....................................................................................................................................18

Table of Contents

1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................2

1.1 Key Concepts.........................................................................................................................3

2. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning....................................................................................4

3. Right to city.................................................................................................................................5

4. Gender and city............................................................................................................................6

4. 1 Creating gender sensitive and women friendly cities...........................................................8

4.2 Gender differences and transport.........................................................................................10

5. Gender and the neighborhood....................................................................................................11

5.1 Gender and parks.................................................................................................................13

7. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................15

7.1 Recommendations of Implementing a Gender-Sensitive Design........................................16

7. 2 Gaps in literature review.....................................................................................................16

References:....................................................................................................................................18

2GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

1. Introduction

According to Low and Smith (2013), public space may be defined in simple terms as a

space or place which is open and thus accessible to all people, irrespective of their class, gender,

ethnicity and other such attributes. For instance, public parks, roads or public buildings may be

called examples of public space. The United Nations classified public space as an open area

where all individuals would feel safe from discrimination or any kind of harassment. As a matter

of fact, it can be stated that public places are pivotal in facilitating favorable economic and social

life in the local communities. Public space, and efficient maintenance of it, would lead to

sustainable communities(Baxter 2016).In other words, public spaces may be termed as mutual

resources within a community where individuals can get together to share experiences and create

value.

Campanella (2017) argues that it was urban planning theorist, Jane Jacobs who

revolutionized the concept of urban planning and public space. Jacobs had opined that the

concept of public space must be incorporated into urban policies, owing to the loss of urban

neighborhoods, thus adversely affecting local citizens. Jacobs had based her statements on her

observation of growing crime rates in American cities in the twentieth century. She had pleaded

for safety and safety measures in public space. She had opposed to the idea of an orthodox

urbanism, which she believed was the source of crime(Jacobs 2016). Yet, in the twenty first

century, cities have become all the more vulnerable to threats and violence. Gender inequality,

conflict, drug trafficking are just some of the issues plaguing urban contexts. Thus, it can safely

be asserted that urban planning and public space would have to be critically reviewed. In the

1. Introduction

According to Low and Smith (2013), public space may be defined in simple terms as a

space or place which is open and thus accessible to all people, irrespective of their class, gender,

ethnicity and other such attributes. For instance, public parks, roads or public buildings may be

called examples of public space. The United Nations classified public space as an open area

where all individuals would feel safe from discrimination or any kind of harassment. As a matter

of fact, it can be stated that public places are pivotal in facilitating favorable economic and social

life in the local communities. Public space, and efficient maintenance of it, would lead to

sustainable communities(Baxter 2016).In other words, public spaces may be termed as mutual

resources within a community where individuals can get together to share experiences and create

value.

Campanella (2017) argues that it was urban planning theorist, Jane Jacobs who

revolutionized the concept of urban planning and public space. Jacobs had opined that the

concept of public space must be incorporated into urban policies, owing to the loss of urban

neighborhoods, thus adversely affecting local citizens. Jacobs had based her statements on her

observation of growing crime rates in American cities in the twentieth century. She had pleaded

for safety and safety measures in public space. She had opposed to the idea of an orthodox

urbanism, which she believed was the source of crime(Jacobs 2016). Yet, in the twenty first

century, cities have become all the more vulnerable to threats and violence. Gender inequality,

conflict, drug trafficking are just some of the issues plaguing urban contexts. Thus, it can safely

be asserted that urban planning and public space would have to be critically reviewed. In the

3GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

following sections, the concept of public safety and space will be examined with respect to

gender.

1.1 Key Concepts

One of the key concepts in providing a gender-sensitive public area is equality.

Karamessini and Rubery (2013) defines equality as the state in which men and women have

uniform access to opportunities or resources. The concept allows uniform participation of people

in decision-making and economic activities regardless of their gender. In public spaces, gender

equality involves elimination of oppressive practices such as sexual violence, sex trafficking, and

other oppressive activities(Waylen 2014). According to the United Nations, gender equality

boosts social development in urban areas. Providing girls and women with equal access to health

care, labor market and education is important (Karamessini and Rubery 2013). Developed

nations employ men and women equally in senior leadership positions – this improves the

overall productivity.

Another concept is social protection. According to Barrientos and Hulme (2016), the

concept involves creation of policies which address issues such as exclusion, gender-based

violence, and unemployment. One element of social protection is that it reduces the risks women

and other minority groups undergo. Further, it empowers women and girls to occupy senior

positions in urban leadership and management. There are four functions of social protection;

prevention, promotion, transformation, and protection(Abramovitz 2017).In public space,

protection involves provision of relief and security to women. On the other hand, prevention

entails introduction of lighting in parks. Promotion involves creation of gender-awareness

programs which educate the public on the negative effects of gender-based violence.

Transformation involves empowerment and inclusion of women in urban design (Chopra 2014).

following sections, the concept of public safety and space will be examined with respect to

gender.

1.1 Key Concepts

One of the key concepts in providing a gender-sensitive public area is equality.

Karamessini and Rubery (2013) defines equality as the state in which men and women have

uniform access to opportunities or resources. The concept allows uniform participation of people

in decision-making and economic activities regardless of their gender. In public spaces, gender

equality involves elimination of oppressive practices such as sexual violence, sex trafficking, and

other oppressive activities(Waylen 2014). According to the United Nations, gender equality

boosts social development in urban areas. Providing girls and women with equal access to health

care, labor market and education is important (Karamessini and Rubery 2013). Developed

nations employ men and women equally in senior leadership positions – this improves the

overall productivity.

Another concept is social protection. According to Barrientos and Hulme (2016), the

concept involves creation of policies which address issues such as exclusion, gender-based

violence, and unemployment. One element of social protection is that it reduces the risks women

and other minority groups undergo. Further, it empowers women and girls to occupy senior

positions in urban leadership and management. There are four functions of social protection;

prevention, promotion, transformation, and protection(Abramovitz 2017).In public space,

protection involves provision of relief and security to women. On the other hand, prevention

entails introduction of lighting in parks. Promotion involves creation of gender-awareness

programs which educate the public on the negative effects of gender-based violence.

Transformation involves empowerment and inclusion of women in urban design (Chopra 2014).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

In this way, social protection promotes creation of a gender-sensitive public place. Other

concepts include gender mainstreaming and provision of the right to the city.

2. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning

According to Rawluszko (2018), gender mainstreaming may be defined as application

of gender as a deciding criterion when it comes to the creation and implementation of policies

and regulatory measures. It may also be defined as the way gender differences have different

implications for both men and women, as far as legislations, government programs or planned

policies are concerned (Daly 2015). This theory is based on a pluralistic approach, where the

diversity between the two sexes is highlighted. Alston (2014) argues that gender mainstreaming

plays a vital role in creating boundaries between the two sexes, since gender differences should

technically not affect public policies.

Mukhopadhyay (2014) opines that gender mainstreaming has also paved the way for

inclusive policies that involve women in more prominent roles in urban planning. In urban

planning, several measures have been taken to include the interests of men, along with that of

men, in the creation, designing, implementation and the assessment of existing policies. While

speaking of public space, it is imperative to analyze the existing discrimination between men and

women. Wamsler (2015) argues that most of the public spaces or public facilities that have been

designed as a part of urban planning seem to be more inclined towards men than women. The

implementation of gender mainstreaming in public space requires good organization and

preparation. In fact, prosecution may be recommended for individuals caught discriminating

between people on grounds of sex. In contrast, Rawluszko (2018) proposes the introduction of

an equality based policy with respect to gender. For instance, it states that the number of and the

In this way, social protection promotes creation of a gender-sensitive public place. Other

concepts include gender mainstreaming and provision of the right to the city.

2. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning

According to Rawluszko (2018), gender mainstreaming may be defined as application

of gender as a deciding criterion when it comes to the creation and implementation of policies

and regulatory measures. It may also be defined as the way gender differences have different

implications for both men and women, as far as legislations, government programs or planned

policies are concerned (Daly 2015). This theory is based on a pluralistic approach, where the

diversity between the two sexes is highlighted. Alston (2014) argues that gender mainstreaming

plays a vital role in creating boundaries between the two sexes, since gender differences should

technically not affect public policies.

Mukhopadhyay (2014) opines that gender mainstreaming has also paved the way for

inclusive policies that involve women in more prominent roles in urban planning. In urban

planning, several measures have been taken to include the interests of men, along with that of

men, in the creation, designing, implementation and the assessment of existing policies. While

speaking of public space, it is imperative to analyze the existing discrimination between men and

women. Wamsler (2015) argues that most of the public spaces or public facilities that have been

designed as a part of urban planning seem to be more inclined towards men than women. The

implementation of gender mainstreaming in public space requires good organization and

preparation. In fact, prosecution may be recommended for individuals caught discriminating

between people on grounds of sex. In contrast, Rawluszko (2018) proposes the introduction of

an equality based policy with respect to gender. For instance, it states that the number of and the

5GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

nature of facilities available for men and women should be equally. Similarly, in public spaces

which are expected to be gender neutral, gender sensitive language, pictorial presentations, signs

or symbols and textual documents should be used.

3. Right to city

Iveson (2013) defines the right to city as the innate right of every individual residing in a

city or urban location. Every such individual has the right to the available urban resources and

the facilities it offers, without fear of being victimized, assaulted or discriminated against. Going

by this statement, Beebeejaun (2016) claims that every individual has the right to adapt to the

city and make it their own. It is a precious opportunity bestowed upon city residents, to remake

and reshape the city and the freedom to improve their own neighborhoods and surroundings.

However, this view can be challenged by Purcell (2014), who abides by Lefebvre’s version of

the right to city. According to Lefebvre, the right to city is a radical mode of thinking which has

nothing to do with the sense of belonging or being a part of a political community. Similarly, it

has not related to the legal citizenship of an individual. Instead, the concept of right to city is

based entirely on the fundamental principle of inhabitance. In simple terms, anyone who inhabits

a city would be entitled to access its amenities and resources. Today, global societies are

increasingly appealing for their “right to the city”; that is social justice and equal access to the

urban life (Marcuse 2014). The right to the city exceeds a person’s access to urban resources

such as public transport, parks or toilets. The concept provides for a platform where individuals

can collectively transform an urban area.According to Albers and Gibb(2013), the right to the

city allows individuals to decide how community projects such as hospitals, schools and

transport systems are run.

nature of facilities available for men and women should be equally. Similarly, in public spaces

which are expected to be gender neutral, gender sensitive language, pictorial presentations, signs

or symbols and textual documents should be used.

3. Right to city

Iveson (2013) defines the right to city as the innate right of every individual residing in a

city or urban location. Every such individual has the right to the available urban resources and

the facilities it offers, without fear of being victimized, assaulted or discriminated against. Going

by this statement, Beebeejaun (2016) claims that every individual has the right to adapt to the

city and make it their own. It is a precious opportunity bestowed upon city residents, to remake

and reshape the city and the freedom to improve their own neighborhoods and surroundings.

However, this view can be challenged by Purcell (2014), who abides by Lefebvre’s version of

the right to city. According to Lefebvre, the right to city is a radical mode of thinking which has

nothing to do with the sense of belonging or being a part of a political community. Similarly, it

has not related to the legal citizenship of an individual. Instead, the concept of right to city is

based entirely on the fundamental principle of inhabitance. In simple terms, anyone who inhabits

a city would be entitled to access its amenities and resources. Today, global societies are

increasingly appealing for their “right to the city”; that is social justice and equal access to the

urban life (Marcuse 2014). The right to the city exceeds a person’s access to urban resources

such as public transport, parks or toilets. The concept provides for a platform where individuals

can collectively transform an urban area.According to Albers and Gibb(2013), the right to the

city allows individuals to decide how community projects such as hospitals, schools and

transport systems are run.

6GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

With respect to gender and public space, the concept of feminist urbanism must be

scrutinized. This theory refers to the social movement which deals with women’s limited

exposure and movement in urban public spaces (Heim LaFrombois 2017). As a direct

consequence of certain patriarchal social and political structures, women have largely been

excluded from spheres such as urban planning in most developing countries of Asia and Africa

(Vasconcellos 2014).

Given that the right to city enables every individual (irrespective of their gender) to

transform the city and its urban planning for the greater good, feminism urbanism is a force to be

reckoned with. Women too, like, deserve to have a say in how their city resources are planned

and developed. Masuda (2016) argues that the essence of right to city lies in creating a good,

safe and favorable public space for all. Such a public space would encourage all inhabitants to

engage in a range of activities. It would be wrong to claim that the right to city is merely a cry

for gender equality. On the other hand, it emphasizes on the right to better opportunities for all,

instead of simply freedom. For example, better living facilities would ensure a safe

neighborhood and stable accommodation for women. Women in rural spaces would be able to

access better transportation facilities as well. This would enable them to get better and more well

paying jobs, since they would no longer be restricted to rural areas(Chant and Datu 2015). In

other words, women would be more equipped to partake in various workforces in the city,

including that of urban planning organizations. For instance, in south Asia, a number of women

have shifted from rural to urban areas to explore their scope of employment (Dixon Mueller

2013).

With respect to gender and public space, the concept of feminist urbanism must be

scrutinized. This theory refers to the social movement which deals with women’s limited

exposure and movement in urban public spaces (Heim LaFrombois 2017). As a direct

consequence of certain patriarchal social and political structures, women have largely been

excluded from spheres such as urban planning in most developing countries of Asia and Africa

(Vasconcellos 2014).

Given that the right to city enables every individual (irrespective of their gender) to

transform the city and its urban planning for the greater good, feminism urbanism is a force to be

reckoned with. Women too, like, deserve to have a say in how their city resources are planned

and developed. Masuda (2016) argues that the essence of right to city lies in creating a good,

safe and favorable public space for all. Such a public space would encourage all inhabitants to

engage in a range of activities. It would be wrong to claim that the right to city is merely a cry

for gender equality. On the other hand, it emphasizes on the right to better opportunities for all,

instead of simply freedom. For example, better living facilities would ensure a safe

neighborhood and stable accommodation for women. Women in rural spaces would be able to

access better transportation facilities as well. This would enable them to get better and more well

paying jobs, since they would no longer be restricted to rural areas(Chant and Datu 2015). In

other words, women would be more equipped to partake in various workforces in the city,

including that of urban planning organizations. For instance, in south Asia, a number of women

have shifted from rural to urban areas to explore their scope of employment (Dixon Mueller

2013).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

4. Gender and city

A city may very well be defined as a geographical area where people of diverse

backgrounds, genders and social strata get together to take part in collected

activities(Marcotuillo and Solecki 2013).To be able to reside freely in a city free of misogyny

and bigotry is the birth right of every woman. Yet, there are numerous issues in urban

planning which plague women. Parker (2016) claims that there is grave imbalance in the way

cities are planned, with respect to gender differences. For instance, a plethora of public facilities

like public toilets seem to exclude women completely from the public space.

As Whitzman (2013) argues, first it would be imperative to understand the ideology

behind sexist cities, and the challenges that a woman faces in such public spaces. He also argues

that a thorough scrutiny of existing urban planning models and renovation of flawed systems be

implemented. Abiding by the theory of the right to the city and space and gender mainstreaming,

it can be said that the public space refers to an oeuvre, or a creative experience of all the

inhabitants in one geographic area. Yet, Lefebvre (2013) argues, the privilege of the “public

space” has largely been reserved for the white heterosexual male. In other words, the very idea

of women entering public space seemed quite atrocious even until a few decades ago. This is

because women had mostly been restricted to private spheres and were unfairly deemed fit for

domestic work only (Landes 2013).

However, Dolores Hayden in 2016 claimed that urban planning underwent a “grand

domestic revolution” in the twentieth century, when for the first time the plight of women

living in cities was highlighted. Majority of the cities are not prepared to address practical needs

of women (Chant 2013). The deeply rooted sexism plays a prominent role in rejection of women

in public spaces such as the park. As such, women avoid parks or crowded street in fear of

4. Gender and city

A city may very well be defined as a geographical area where people of diverse

backgrounds, genders and social strata get together to take part in collected

activities(Marcotuillo and Solecki 2013).To be able to reside freely in a city free of misogyny

and bigotry is the birth right of every woman. Yet, there are numerous issues in urban

planning which plague women. Parker (2016) claims that there is grave imbalance in the way

cities are planned, with respect to gender differences. For instance, a plethora of public facilities

like public toilets seem to exclude women completely from the public space.

As Whitzman (2013) argues, first it would be imperative to understand the ideology

behind sexist cities, and the challenges that a woman faces in such public spaces. He also argues

that a thorough scrutiny of existing urban planning models and renovation of flawed systems be

implemented. Abiding by the theory of the right to the city and space and gender mainstreaming,

it can be said that the public space refers to an oeuvre, or a creative experience of all the

inhabitants in one geographic area. Yet, Lefebvre (2013) argues, the privilege of the “public

space” has largely been reserved for the white heterosexual male. In other words, the very idea

of women entering public space seemed quite atrocious even until a few decades ago. This is

because women had mostly been restricted to private spheres and were unfairly deemed fit for

domestic work only (Landes 2013).

However, Dolores Hayden in 2016 claimed that urban planning underwent a “grand

domestic revolution” in the twentieth century, when for the first time the plight of women

living in cities was highlighted. Majority of the cities are not prepared to address practical needs

of women (Chant 2013). The deeply rooted sexism plays a prominent role in rejection of women

in public spaces such as the park. As such, women avoid parks or crowded street in fear of

8GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

harassment or discrimination. Violation of basic human rights of women and the failure of

the law enforcement to aid women are two of the major challenges that women face in

cities(MacKinnon 2017). Wardale, Pojani and Brown (2018) are of the opinion that sexism in

cities have resulted in zoned cities. In such urban planning, the facilities related to entertainment,

shopping and work are segregated and in distant locations in developing countries like Africa

and some parts of Asia (Taylor and Williams 2013). Also, single women living alone are looked

down upon in certain cities in countries like India and Latin America (Ronald and Nakano

2013).As a consequence, women living and working in these cities find it rather hard to find

affordable accommodation for themselves (Peake 2016). Gender pay inequity is one of the

challenges that women have to face while seeking suitable employment. Lack of education in the

early years is also another factor that prevents women from obtaining well paying jobs in most

third world countries (Kelly 2013).

As Sweet and Ortiz Escalante (2015) claim, urban planning has provided almost

negligible amenities to its female inhabitants, except middle class, married Caucasian women.

Others have limited access to basic urban facilities needed for survival. For instance, for single

working mothers, there are almost no childcare facilities in accessible areas (Taylor and Conger

2017). Similarly, green spaces are unavailable as well. As a matter of fact, women fear to

venture into such parts of the city for fear of crime and violence against them. Sreeerathan and

Van den Bosch (2014) argue that sexual and physical assault is another real threat that women

have to face in cities. In public spaces and in public transportation services, many women are

subjected to violence. In particular, women fear harassment from people who cite their choice of

dressing (Haas & Timmerman 2010). In this case, a comparison may be drawn between Vienna,

which has gender sensitive urban planning and the women in Iran, where gender discrimination

harassment or discrimination. Violation of basic human rights of women and the failure of

the law enforcement to aid women are two of the major challenges that women face in

cities(MacKinnon 2017). Wardale, Pojani and Brown (2018) are of the opinion that sexism in

cities have resulted in zoned cities. In such urban planning, the facilities related to entertainment,

shopping and work are segregated and in distant locations in developing countries like Africa

and some parts of Asia (Taylor and Williams 2013). Also, single women living alone are looked

down upon in certain cities in countries like India and Latin America (Ronald and Nakano

2013).As a consequence, women living and working in these cities find it rather hard to find

affordable accommodation for themselves (Peake 2016). Gender pay inequity is one of the

challenges that women have to face while seeking suitable employment. Lack of education in the

early years is also another factor that prevents women from obtaining well paying jobs in most

third world countries (Kelly 2013).

As Sweet and Ortiz Escalante (2015) claim, urban planning has provided almost

negligible amenities to its female inhabitants, except middle class, married Caucasian women.

Others have limited access to basic urban facilities needed for survival. For instance, for single

working mothers, there are almost no childcare facilities in accessible areas (Taylor and Conger

2017). Similarly, green spaces are unavailable as well. As a matter of fact, women fear to

venture into such parts of the city for fear of crime and violence against them. Sreeerathan and

Van den Bosch (2014) argue that sexual and physical assault is another real threat that women

have to face in cities. In public spaces and in public transportation services, many women are

subjected to violence. In particular, women fear harassment from people who cite their choice of

dressing (Haas & Timmerman 2010). In this case, a comparison may be drawn between Vienna,

which has gender sensitive urban planning and the women in Iran, where gender discrimination

9GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

levels are high. In Vienna, unlike Iran, a gender mainstreaming policy is followed where men

and women are given equal rights and included equally in urban planning. However, in Iran,

women are grossly underrepresented in the governing institutions which deprives them of their

basic rights (Jayachandran 2015). For instance, the transportation facilities available in Iran are

not gender sensitive, which makes them vulnerable to assault and harassment. On the other hand,

in Vienna, parks and other public spaces have been built keeping in mind the unique

requirements of women (Flanagan 2014).

4. 1 Creating gender sensitive and women friendly cities

A majority of women seldom feel welcome or safe even in public spaces in the urban

cities. In a large number of cities in the middle east, a woman moving around alone in the city is

considered unvirtuous, which makes them a potential target for harassment. According to a

habitat report by the United Nations, women are afflicted by problems like unstable housing,

inadequate sanitation and gender based violence (Fulu et al. 2013).

As Viswanath (2013) argues, it is important to develop cities and public spaces which are

gender neutral and women friendly –The first aspect that must be considered while creating

women friendly cities would be safety. Clear signage, prioritizing pedestrians, maintenance

of clear sights in public spaces and good lighting are some measures which could reduce

changes of physical harassment and sexual assault against women, as claimed by the author .

Going by the claims of Viswanath (2013), it can be said that improvement of transportation

infrastructure would help in customizing cities according to the needs of women. Women require

public transport as much as men because it is cheap and convenient (Solonem and Toivonen

2013). Public spaces that are under surveillance and are properly lit would make women feel

safer, especially after dark. Renovating existing modes of public transport to make them

levels are high. In Vienna, unlike Iran, a gender mainstreaming policy is followed where men

and women are given equal rights and included equally in urban planning. However, in Iran,

women are grossly underrepresented in the governing institutions which deprives them of their

basic rights (Jayachandran 2015). For instance, the transportation facilities available in Iran are

not gender sensitive, which makes them vulnerable to assault and harassment. On the other hand,

in Vienna, parks and other public spaces have been built keeping in mind the unique

requirements of women (Flanagan 2014).

4. 1 Creating gender sensitive and women friendly cities

A majority of women seldom feel welcome or safe even in public spaces in the urban

cities. In a large number of cities in the middle east, a woman moving around alone in the city is

considered unvirtuous, which makes them a potential target for harassment. According to a

habitat report by the United Nations, women are afflicted by problems like unstable housing,

inadequate sanitation and gender based violence (Fulu et al. 2013).

As Viswanath (2013) argues, it is important to develop cities and public spaces which are

gender neutral and women friendly –The first aspect that must be considered while creating

women friendly cities would be safety. Clear signage, prioritizing pedestrians, maintenance

of clear sights in public spaces and good lighting are some measures which could reduce

changes of physical harassment and sexual assault against women, as claimed by the author .

Going by the claims of Viswanath (2013), it can be said that improvement of transportation

infrastructure would help in customizing cities according to the needs of women. Women require

public transport as much as men because it is cheap and convenient (Solonem and Toivonen

2013). Public spaces that are under surveillance and are properly lit would make women feel

safer, especially after dark. Renovating existing modes of public transport to make them

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

10GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

comfortable for women would ensure that women are able to effectively exercise their “right to

city”. According to Viswanath (2013), well lit bylanes and sidewalks and more routes which

cover busy areas, separate bicycle lanes and other such measures may also be implemented since

it would help women access necessary facilities like stores, groceries or even work.

As Jafry and Sulaiman (2013) argue, that In many countries, architecture and urban

design practices favor individuals who are healthy and economically active. Gender-sensitive

cities based on gender mainstreaming would devise policies on a political level, which would

consider the interests of women in aspects like urban design (Mukhopadhyay 2016). Another

element of gender-sensitive urban planning is provision of municipal services such as water, and

security to urban locations where women reside. In some neighborhoods, the risk of harassment

is high. Provision of better security protects women against the aggressive physical activities

(Horelli 2017).

4.2 Gender differences and transport

It must be admitted that urban environments, including public transportation are not

gender neutral. There are observable differences in the way men and women travel around

urban locations, which is due to gender based hierarchies. According to Levy (2013), more

women than men have domestic responsibilities, but less modes of transport. As a result, a

woman is twice more likely to travel to a variety of places than men who are more likely to

travel to and fro work, without breaks in between. As a matter of fact, at least 42 per cent women

need to make stops during travel as compared to a negligible 30 per cent in the case of men. This

kind of varied use prevents women from being restricted to only one mode of transport in public.

Instead, they require more access to transportation facilities, wider pavements, more lighting and

other such facilities (Akar, Fisher and Namgung 2013).

comfortable for women would ensure that women are able to effectively exercise their “right to

city”. According to Viswanath (2013), well lit bylanes and sidewalks and more routes which

cover busy areas, separate bicycle lanes and other such measures may also be implemented since

it would help women access necessary facilities like stores, groceries or even work.

As Jafry and Sulaiman (2013) argue, that In many countries, architecture and urban

design practices favor individuals who are healthy and economically active. Gender-sensitive

cities based on gender mainstreaming would devise policies on a political level, which would

consider the interests of women in aspects like urban design (Mukhopadhyay 2016). Another

element of gender-sensitive urban planning is provision of municipal services such as water, and

security to urban locations where women reside. In some neighborhoods, the risk of harassment

is high. Provision of better security protects women against the aggressive physical activities

(Horelli 2017).

4.2 Gender differences and transport

It must be admitted that urban environments, including public transportation are not

gender neutral. There are observable differences in the way men and women travel around

urban locations, which is due to gender based hierarchies. According to Levy (2013), more

women than men have domestic responsibilities, but less modes of transport. As a result, a

woman is twice more likely to travel to a variety of places than men who are more likely to

travel to and fro work, without breaks in between. As a matter of fact, at least 42 per cent women

need to make stops during travel as compared to a negligible 30 per cent in the case of men. This

kind of varied use prevents women from being restricted to only one mode of transport in public.

Instead, they require more access to transportation facilities, wider pavements, more lighting and

other such facilities (Akar, Fisher and Namgung 2013).

11GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Another major difference in the way men and women perceive public transport is the

safety factor. Since most public transportation systems across the world fail to provide gender

sensitive measures, the rate of sexual harassment and atrocities against women increase. For

example, women feel extremely unsafe in public spaces like subways, bridges and access paths

(Loukaitou-Sideris 2014). The fear of being stalked, violated, attacked or assaulted has changed

the way most women use public transport. For example, women tend to travel in pairs or groups,

stick to well lit areas and avoid isolated public spaces.

To counter these issues, several measures are being taken by countries around the world

to ensure that public transport is gender neutral and gender sensitive. For example, women only

transportation systems have been implemented in a number of countries like India and some

parts of Asia and in Mexico. A case study of this is in the city of Mexico, where women only

transportation has been implemented – this is known as pink transportation. The case study

claims that the perceived threats to women’s safety are major factors that modifies and affects

travel behavior of women in public (Drunkel Gargia 2013). Women only transportation draws on

the defensible space theory by Oscar Newman. According to Jacobs and Lees (2013), spatial

design, a common concept in public space is directly related to the level of crime. It was

assumed that transportation systems which were entirely operated by women and catered to only

women customers would reduce their fear of travelling in public transport. In short, pink

transportation can be called a design out of fear in urban planning. However, Levanon and

Grusky (2016) argue that gender based segregation has reached an extreme in this century and

use of women only facilities would simply deepen the issue of gender discrimination. Such

women only transportation may further highlight the differences between men and women.

Another major difference in the way men and women perceive public transport is the

safety factor. Since most public transportation systems across the world fail to provide gender

sensitive measures, the rate of sexual harassment and atrocities against women increase. For

example, women feel extremely unsafe in public spaces like subways, bridges and access paths

(Loukaitou-Sideris 2014). The fear of being stalked, violated, attacked or assaulted has changed

the way most women use public transport. For example, women tend to travel in pairs or groups,

stick to well lit areas and avoid isolated public spaces.

To counter these issues, several measures are being taken by countries around the world

to ensure that public transport is gender neutral and gender sensitive. For example, women only

transportation systems have been implemented in a number of countries like India and some

parts of Asia and in Mexico. A case study of this is in the city of Mexico, where women only

transportation has been implemented – this is known as pink transportation. The case study

claims that the perceived threats to women’s safety are major factors that modifies and affects

travel behavior of women in public (Drunkel Gargia 2013). Women only transportation draws on

the defensible space theory by Oscar Newman. According to Jacobs and Lees (2013), spatial

design, a common concept in public space is directly related to the level of crime. It was

assumed that transportation systems which were entirely operated by women and catered to only

women customers would reduce their fear of travelling in public transport. In short, pink

transportation can be called a design out of fear in urban planning. However, Levanon and

Grusky (2016) argue that gender based segregation has reached an extreme in this century and

use of women only facilities would simply deepen the issue of gender discrimination. Such

women only transportation may further highlight the differences between men and women.

12GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

5. Gender and the neighborhood

Manolache (2013) is of the opinion that urban cities share a complex relationship with

gender. The planning of most cities, their management, the layout and even their mobility have

affected and altered the way women use the basic neighborhood facilities. As Sweet and Ortiz

Escalante (2015) had argued, most cities are planned in such a way that women are denied equal

access to basic facilities like toilets, grocery stores, pharmacies and so on. For instance, England

(2017) claims that women, more than men, make trips to shops and other such facilities for

groceries, entertainment and so on. Women, on an average, have more chores and daily tasks

than men (Lindsey 2015). As such, they make a number of trips in the course of a day to the

grocery shops, supermarkets, retail stores and so on. Moreover, women are more likely to visit

childcare centers, parks, playschools and other similar urban facilities. However, as Hampton,

Goulet and Albanesius (2015) claim a feminist critique of the concept of everyday life must be

implemented in this case. Cities have also proven to be symbols of freedom for women, where

gender equality can easily be forged. The theory of everyday life and the concept of the right to

city which was introduced by Lefebvre must be reviewed in this aspect. As a matter of fact, the

concepts of gender and feminism and everyday life are intricately linked.

Yet, certain differences persist in the ways men and women use neighborhood facilities.

Moreover, according to Blau (2016), the rates of employment amongst women in developing

cities are quite low, as compared to men. This could be because women usually live in poor,

disadvantaged neighborhoods in the cities, which may be isolated and without access to the

essential facilities (Albanesi and Sahin 2018).

5. Gender and the neighborhood

Manolache (2013) is of the opinion that urban cities share a complex relationship with

gender. The planning of most cities, their management, the layout and even their mobility have

affected and altered the way women use the basic neighborhood facilities. As Sweet and Ortiz

Escalante (2015) had argued, most cities are planned in such a way that women are denied equal

access to basic facilities like toilets, grocery stores, pharmacies and so on. For instance, England

(2017) claims that women, more than men, make trips to shops and other such facilities for

groceries, entertainment and so on. Women, on an average, have more chores and daily tasks

than men (Lindsey 2015). As such, they make a number of trips in the course of a day to the

grocery shops, supermarkets, retail stores and so on. Moreover, women are more likely to visit

childcare centers, parks, playschools and other similar urban facilities. However, as Hampton,

Goulet and Albanesius (2015) claim a feminist critique of the concept of everyday life must be

implemented in this case. Cities have also proven to be symbols of freedom for women, where

gender equality can easily be forged. The theory of everyday life and the concept of the right to

city which was introduced by Lefebvre must be reviewed in this aspect. As a matter of fact, the

concepts of gender and feminism and everyday life are intricately linked.

Yet, certain differences persist in the ways men and women use neighborhood facilities.

Moreover, according to Blau (2016), the rates of employment amongst women in developing

cities are quite low, as compared to men. This could be because women usually live in poor,

disadvantaged neighborhoods in the cities, which may be isolated and without access to the

essential facilities (Albanesi and Sahin 2018).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

13GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

5.1 Gender and parks

A park may be defined as a “green space” within a city where the inhabitants may get

together to spend a leisurely time. As such, a park is one of the most common examples of

public spaces, where men, women and children can relax without fear of crime or violence. With

the population in cities increasing at an alarming rate, there is a growing need to incorporate

more such green spaces as part of the urban planning (Wolch, Byrne and Newell 2014). Yet as

Johnson and Glover (2013) argue, the planning of parks has posed a number of challenges for

women. Women should be freely able to access such parks, with or without company. However,

the threat of assault and violence prevails (Madan and Nalla 2016). The lack of maintenance of

public serviceshas left women vulnerable to the risk of sexual harassment and violence in public

parks. For most women, the mere thought of passing through a park or similar public spaces can

evoke anxiety and stress. There are many factors that shape an individual’s perception of safety

– namely, commitment, belonging and comfort.

Waldheim (2015) argues that there are numerous factors which could contribute to a

woman’s feeling of insecurities and fear in public parks. For example, poor lighting in the

surrounding areas and lack of accessibility to suitable modes of transport is a major challenge.

Poor infrastructure of the parks, along with lack of clear sight, make women targets of

harassment in such areas. Another challenge that women face in parks is the lack of policing.

Most parks lack supervision, which makes it the hub of violent crime (Madan and Nalla 2016).

At night or even during the day, police patrol is absent in and around parks. Moreover, if women

are attacked and they lodge a complaint, the local police are often unwilling to process the

claims (Loughran 2014).

5.1 Gender and parks

A park may be defined as a “green space” within a city where the inhabitants may get

together to spend a leisurely time. As such, a park is one of the most common examples of

public spaces, where men, women and children can relax without fear of crime or violence. With

the population in cities increasing at an alarming rate, there is a growing need to incorporate

more such green spaces as part of the urban planning (Wolch, Byrne and Newell 2014). Yet as

Johnson and Glover (2013) argue, the planning of parks has posed a number of challenges for

women. Women should be freely able to access such parks, with or without company. However,

the threat of assault and violence prevails (Madan and Nalla 2016). The lack of maintenance of

public serviceshas left women vulnerable to the risk of sexual harassment and violence in public

parks. For most women, the mere thought of passing through a park or similar public spaces can

evoke anxiety and stress. There are many factors that shape an individual’s perception of safety

– namely, commitment, belonging and comfort.

Waldheim (2015) argues that there are numerous factors which could contribute to a

woman’s feeling of insecurities and fear in public parks. For example, poor lighting in the

surrounding areas and lack of accessibility to suitable modes of transport is a major challenge.

Poor infrastructure of the parks, along with lack of clear sight, make women targets of

harassment in such areas. Another challenge that women face in parks is the lack of policing.

Most parks lack supervision, which makes it the hub of violent crime (Madan and Nalla 2016).

At night or even during the day, police patrol is absent in and around parks. Moreover, if women

are attacked and they lodge a complaint, the local police are often unwilling to process the

claims (Loughran 2014).

14GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Damyanovic (2013) is of the opinion that gender mainstreaming is the only solution to

reduce the issues faced by women in parks and public faces. Designing and implementing safe

parks for women would recognize the fact that gender differences should have an effect on the

way public space is planned and organized. It also highlights the fact that public parks are indeed

not gender neutral. Instead the kind of design of the public space can potentially impede or

facilitate the safety aspect for girls and women in cities. A case study of this can be seen in

Vienna, Austria where a gender sensitive park has been developed in Einsiedlerpark.This

was chosen as the case study because this park set an example as far as gender sensitive parks

are concerned. The park also presents recommendations for gender sensitive parks and public

spaces and hence it was chosen as a case study. As part of the planning phase, the officials held

sessions with female urban planning experts, sociologists and also took into account the stories

of girls and their concerns. Accordingly, renovations were implemented at the park which

included open and clear common areas where women could roam freely, proper lighting after

dark, appropriate design elements and regular police patrol (Irschik and Kail 2013). The main

purpose of such a park is to ensure that young girls and adult women can freely access parks

without having to live in fear. As a matter of fact, the city of Vienna plans to incorporate several

such parks within the city (Roberts 2016).

A few recommendations can be made with respect to safety for women in public parks

following the example of the case study. Like Einsiedlerpark footpaths and other routes within

the parks must be made clearly visible, with a line of sight to the main streets. A clear route

concept must be followed. Proper lighting should be provided in parks, along with standard

patrolling facilities. According to Flanagan (2014) the situation can be addressed by changing

the park design or introducing policies which address the differences. Changing the park design

Damyanovic (2013) is of the opinion that gender mainstreaming is the only solution to

reduce the issues faced by women in parks and public faces. Designing and implementing safe

parks for women would recognize the fact that gender differences should have an effect on the

way public space is planned and organized. It also highlights the fact that public parks are indeed

not gender neutral. Instead the kind of design of the public space can potentially impede or

facilitate the safety aspect for girls and women in cities. A case study of this can be seen in

Vienna, Austria where a gender sensitive park has been developed in Einsiedlerpark.This

was chosen as the case study because this park set an example as far as gender sensitive parks

are concerned. The park also presents recommendations for gender sensitive parks and public

spaces and hence it was chosen as a case study. As part of the planning phase, the officials held

sessions with female urban planning experts, sociologists and also took into account the stories

of girls and their concerns. Accordingly, renovations were implemented at the park which

included open and clear common areas where women could roam freely, proper lighting after

dark, appropriate design elements and regular police patrol (Irschik and Kail 2013). The main

purpose of such a park is to ensure that young girls and adult women can freely access parks

without having to live in fear. As a matter of fact, the city of Vienna plans to incorporate several

such parks within the city (Roberts 2016).

A few recommendations can be made with respect to safety for women in public parks

following the example of the case study. Like Einsiedlerpark footpaths and other routes within

the parks must be made clearly visible, with a line of sight to the main streets. A clear route

concept must be followed. Proper lighting should be provided in parks, along with standard

patrolling facilities. According to Flanagan (2014) the situation can be addressed by changing

the park design or introducing policies which address the differences. Changing the park design

15GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

and proper maintenance, following the example of Einsiedlerpark, may address safety concerns

common to women. On the other hand, proper programming makes the park area more appealing

to all sexes. The concepts make the park more safe and attractive to women – this leads to an

increase in the number of women visiting the public space for leisure or physical activity. The

basic concept in re-designing existing parks is to create better and safe positions for girls and

women in public spaces.

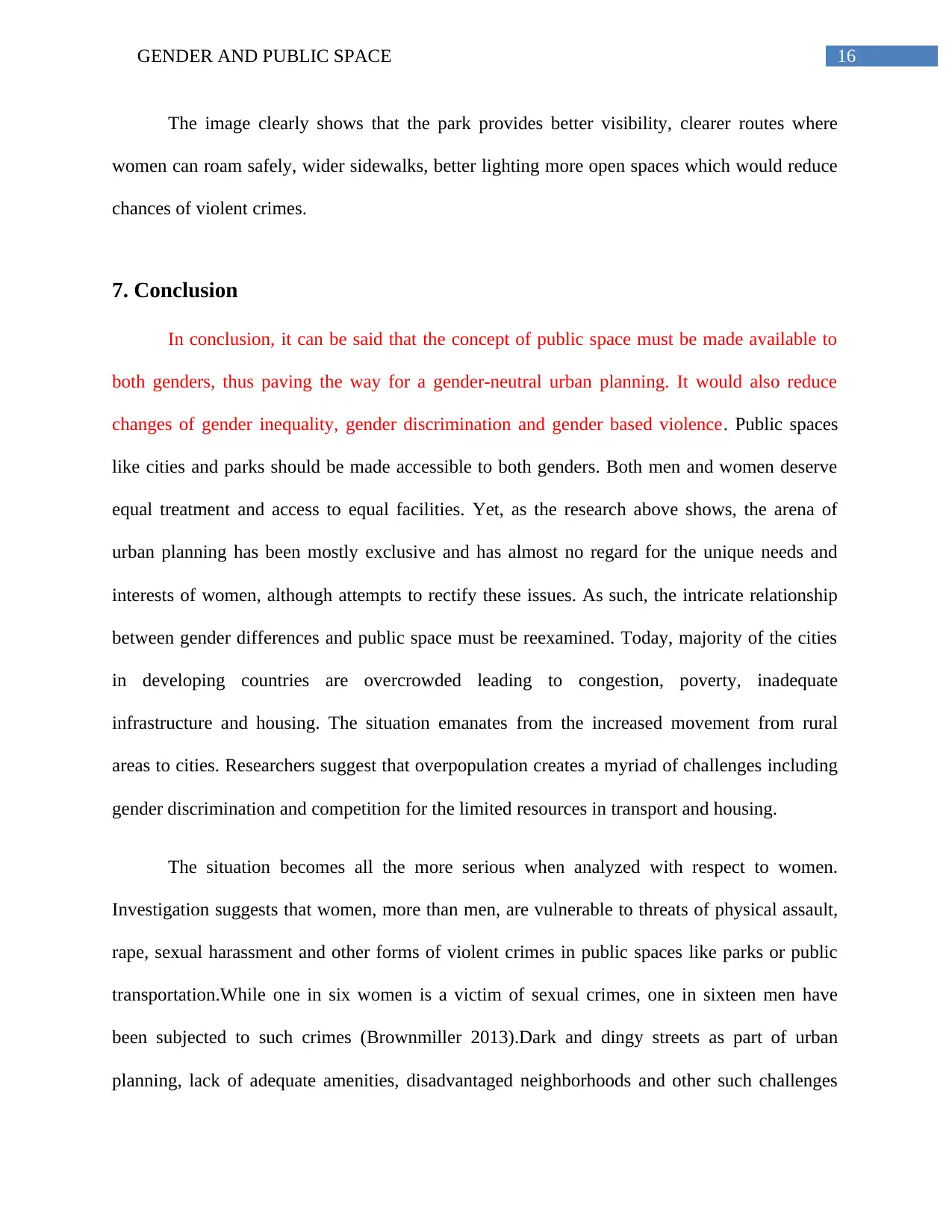

(Figure: Structure of gender sensitive park)

and proper maintenance, following the example of Einsiedlerpark, may address safety concerns

common to women. On the other hand, proper programming makes the park area more appealing

to all sexes. The concepts make the park more safe and attractive to women – this leads to an

increase in the number of women visiting the public space for leisure or physical activity. The

basic concept in re-designing existing parks is to create better and safe positions for girls and

women in public spaces.

(Figure: Structure of gender sensitive park)

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

16GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

The image clearly shows that the park provides better visibility, clearer routes where

women can roam safely, wider sidewalks, better lighting more open spaces which would reduce

chances of violent crimes.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that the concept of public space must be made available to

both genders, thus paving the way for a gender-neutral urban planning. It would also reduce

changes of gender inequality, gender discrimination and gender based violence. Public spaces

like cities and parks should be made accessible to both genders. Both men and women deserve

equal treatment and access to equal facilities. Yet, as the research above shows, the arena of

urban planning has been mostly exclusive and has almost no regard for the unique needs and

interests of women, although attempts to rectify these issues. As such, the intricate relationship

between gender differences and public space must be reexamined. Today, majority of the cities

in developing countries are overcrowded leading to congestion, poverty, inadequate

infrastructure and housing. The situation emanates from the increased movement from rural

areas to cities. Researchers suggest that overpopulation creates a myriad of challenges including

gender discrimination and competition for the limited resources in transport and housing.

The situation becomes all the more serious when analyzed with respect to women.

Investigation suggests that women, more than men, are vulnerable to threats of physical assault,

rape, sexual harassment and other forms of violent crimes in public spaces like parks or public

transportation.While one in six women is a victim of sexual crimes, one in sixteen men have

been subjected to such crimes (Brownmiller 2013).Dark and dingy streets as part of urban

planning, lack of adequate amenities, disadvantaged neighborhoods and other such challenges

The image clearly shows that the park provides better visibility, clearer routes where

women can roam safely, wider sidewalks, better lighting more open spaces which would reduce

chances of violent crimes.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that the concept of public space must be made available to

both genders, thus paving the way for a gender-neutral urban planning. It would also reduce

changes of gender inequality, gender discrimination and gender based violence. Public spaces

like cities and parks should be made accessible to both genders. Both men and women deserve

equal treatment and access to equal facilities. Yet, as the research above shows, the arena of

urban planning has been mostly exclusive and has almost no regard for the unique needs and

interests of women, although attempts to rectify these issues. As such, the intricate relationship

between gender differences and public space must be reexamined. Today, majority of the cities

in developing countries are overcrowded leading to congestion, poverty, inadequate

infrastructure and housing. The situation emanates from the increased movement from rural

areas to cities. Researchers suggest that overpopulation creates a myriad of challenges including

gender discrimination and competition for the limited resources in transport and housing.

The situation becomes all the more serious when analyzed with respect to women.

Investigation suggests that women, more than men, are vulnerable to threats of physical assault,

rape, sexual harassment and other forms of violent crimes in public spaces like parks or public

transportation.While one in six women is a victim of sexual crimes, one in sixteen men have

been subjected to such crimes (Brownmiller 2013).Dark and dingy streets as part of urban

planning, lack of adequate amenities, disadvantaged neighborhoods and other such challenges

17GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

pose a serious threat to the safety of women. As a result, there is a growing awareness to

incorporate gender mainstreaming as part of urban planning. As part of gender mainstreaming,

governing bodies would take into consideration the interests of both sexes while drawing urban

policies and programs. The research above also presents two case studies, which provide

recommendations on ways of implementing gender sensitive parks and transportation facilities.

7.1 Recommendations of Implementing a Gender-Sensitive Design

Creation of a specialized gender department in all urban institutions. The agency should

set the tone and direction of addressing gender issues. In this way, local authorities can

promote equalityin all activities.

Designs for gender sensitive public spaces should be devised by the urban planning

institutions. In other words, cities should be made more women friendly, as the research

above shows. This can be done by including provisions with respect to bicycling

infrastructure, construction of wider sidewalks and clearer routes, installation of

surveillance cameras in remote and isolated regions, easy accessibility to every day needs

like pharmacies, medical facilities, groceries and entertainment, well lit cities along with

the adequate support of law enforcement (Chant 2013).

Empowerment of women through education and awareness programs (Hall 2013).

Women should be made aware of the rise of gender mainstreaming and their role in

urban planning. The challenges faced by women across the world should be highlighted

and measures to counter them should be provided. Women need to be aware of their

basic right to the city and urban facilities and the fact that they have a say in how policies

and urban planning systems are formulated.

pose a serious threat to the safety of women. As a result, there is a growing awareness to

incorporate gender mainstreaming as part of urban planning. As part of gender mainstreaming,

governing bodies would take into consideration the interests of both sexes while drawing urban

policies and programs. The research above also presents two case studies, which provide

recommendations on ways of implementing gender sensitive parks and transportation facilities.

7.1 Recommendations of Implementing a Gender-Sensitive Design

Creation of a specialized gender department in all urban institutions. The agency should

set the tone and direction of addressing gender issues. In this way, local authorities can

promote equalityin all activities.

Designs for gender sensitive public spaces should be devised by the urban planning

institutions. In other words, cities should be made more women friendly, as the research

above shows. This can be done by including provisions with respect to bicycling

infrastructure, construction of wider sidewalks and clearer routes, installation of

surveillance cameras in remote and isolated regions, easy accessibility to every day needs

like pharmacies, medical facilities, groceries and entertainment, well lit cities along with

the adequate support of law enforcement (Chant 2013).

Empowerment of women through education and awareness programs (Hall 2013).

Women should be made aware of the rise of gender mainstreaming and their role in

urban planning. The challenges faced by women across the world should be highlighted

and measures to counter them should be provided. Women need to be aware of their

basic right to the city and urban facilities and the fact that they have a say in how policies

and urban planning systems are formulated.

18GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

7. 2 Gaps in literature review

A few major gaps have been identified after a review of literature pertaining to the

subject. For example, there is very little research which provides recommendations and

suggestions for gender sensitive public spaces. Gender mainstreaming has been studied in great

detail, and research has been provided on how to provide men and women with equal voice with

respect to matters that concern them. However, the representation of women in urban planning

issues have been almost negligible. Also, the concept of gender sensitive public spaces like parks

and transportation facilities is a relatively new concept and has only been implemented in a few

cities like Vienna so far. As a result, there is almost negligible research on the urban planning

concepts applied in such gender sensitive public spaces, which could have served as examples

for other cities around the world.

References:

Aalbers, M.B. and Gibb, K., 2014. Housing and the right to the city: introduction to the special

issue.

Abramovitz, M., 2017. Regulating the lives of women: Social welfare policy from colonial times

to the present. Routledge.

Akar, G., Fischer, N. and Namgung, M., 2013. Bicycling choice and gender case study: The

Ohio State University. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 7(5), pp.347-365.

Albanesi, S. and Şahin, A., 2018. The gender unemployment gap. Review of Economic

Dynamics, 30, pp.47-67.

7. 2 Gaps in literature review

A few major gaps have been identified after a review of literature pertaining to the

subject. For example, there is very little research which provides recommendations and

suggestions for gender sensitive public spaces. Gender mainstreaming has been studied in great

detail, and research has been provided on how to provide men and women with equal voice with

respect to matters that concern them. However, the representation of women in urban planning

issues have been almost negligible. Also, the concept of gender sensitive public spaces like parks

and transportation facilities is a relatively new concept and has only been implemented in a few

cities like Vienna so far. As a result, there is almost negligible research on the urban planning

concepts applied in such gender sensitive public spaces, which could have served as examples

for other cities around the world.

References:

Aalbers, M.B. and Gibb, K., 2014. Housing and the right to the city: introduction to the special

issue.

Abramovitz, M., 2017. Regulating the lives of women: Social welfare policy from colonial times

to the present. Routledge.

Akar, G., Fischer, N. and Namgung, M., 2013. Bicycling choice and gender case study: The

Ohio State University. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 7(5), pp.347-365.

Albanesi, S. and Şahin, A., 2018. The gender unemployment gap. Review of Economic

Dynamics, 30, pp.47-67.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

19GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Alston, M., 2014, November. Gender mainstreaming and climate change. In Women's Studies

International Forum (Vol. 47, pp. 287-294). Pergamon.

Barrientos, A. and Hulme, D. eds., 2016. Social protection for the poor and poorest: Concepts,

policies and politics. Springer.

Baxter, J. ed., 2016. Speaking out: The female voice in public contexts. Springer.

Beebeejaun, Y., 2017. Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. Journal of Urban

Affairs, 39(3), pp.323-334.

Blau, F.D., 2016. Gender, inequality, and wages. OUP Catalogue.

Brownmiller, S., 2013. Against our will: Men, women and rape. Open Road Media.

Campanella, T.J., 2017. Jane Jacobs and the death and life of American planning.

In Reconsidering Jane Jacobs (pp. 149-168). Routledge.

Chant, S. and Datu, K., 2015. Women in cities: Prosperity or poverty? A need for multi-

dimensional and multi-spatial analysis. In The City in Urban Poverty (pp. 39-63). Palgrave

Macmillan, London.

Chant, S., 2013. Cities through a “gender lens”: a golden “urban age” for women in the global

South?. Environment and Urbanisation, 25(1), pp. 9 – 29

Coates, J., 2015. Women, men and language: A sociolinguistic account of gender differences in

language. Routledge.

Daly, M., 2015. Gender Mainstreaming in Theory and Practice. Social Politics, 13(1), p. 433–

450.

Alston, M., 2014, November. Gender mainstreaming and climate change. In Women's Studies

International Forum (Vol. 47, pp. 287-294). Pergamon.

Barrientos, A. and Hulme, D. eds., 2016. Social protection for the poor and poorest: Concepts,

policies and politics. Springer.

Baxter, J. ed., 2016. Speaking out: The female voice in public contexts. Springer.

Beebeejaun, Y., 2017. Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. Journal of Urban

Affairs, 39(3), pp.323-334.

Blau, F.D., 2016. Gender, inequality, and wages. OUP Catalogue.

Brownmiller, S., 2013. Against our will: Men, women and rape. Open Road Media.

Campanella, T.J., 2017. Jane Jacobs and the death and life of American planning.

In Reconsidering Jane Jacobs (pp. 149-168). Routledge.

Chant, S. and Datu, K., 2015. Women in cities: Prosperity or poverty? A need for multi-

dimensional and multi-spatial analysis. In The City in Urban Poverty (pp. 39-63). Palgrave

Macmillan, London.

Chant, S., 2013. Cities through a “gender lens”: a golden “urban age” for women in the global

South?. Environment and Urbanisation, 25(1), pp. 9 – 29

Coates, J., 2015. Women, men and language: A sociolinguistic account of gender differences in

language. Routledge.

Daly, M., 2015. Gender Mainstreaming in Theory and Practice. Social Politics, 13(1), p. 433–

450.

20GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Dixon-Mueller, R.B., 2013. Rural women at work: Strategies for development in South Asia.

RFF Press.

Dunckel-Graglia, A., 2013. Women-only transportation: How “pink” public transportation

changes public perception of women’s mobility. Journal of Public Transportation, 16(2), p.5.

England, P., 2017. Households, employment, and gender: A social, economic, and demographic

view. Routledge.

Flanagan, M., 2014. Private needs, public space: public toilets provision in the Anglo-

Atlanticpatriarchal city: London, Dublin, Toronto and Chicago. Urban History, 41(2), pp. 265-

290.

Fulu, E., Warner, X., Miedema, S., Jewkes, R., Roselli, T. and Lang, J., 2013. Why Do Some

Men Use Violence Against Women and how Can We Prevent It?: Quantitative Findings from the

United Nations Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok:

UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and UNV.

Haas, S., and Timmerman, G., 2010. Sexual harassment in the context of double male

dominance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19(6), pp. 717-734.

Hall, C.M., 2013. Women and empowerment: Strategies for increasing autonomy. Routledge.

Hampton, K.N., Goulet, L.S. and Albanesius, G., 2015. Change in the social life of urban public

spaces: The rise of mobile phones and women, and the decline of aloneness over 30 years. Urban

Studies, 52(8), pp.1489-1504.

Heim LaFrombois, M., 2017. Blind spots and pop-up spots: A feminist exploration into the

discourses of do-it-yourself (DIY) urbanism. Urban Studies, 54(2), pp.421-436.

Dixon-Mueller, R.B., 2013. Rural women at work: Strategies for development in South Asia.

RFF Press.

Dunckel-Graglia, A., 2013. Women-only transportation: How “pink” public transportation

changes public perception of women’s mobility. Journal of Public Transportation, 16(2), p.5.

England, P., 2017. Households, employment, and gender: A social, economic, and demographic

view. Routledge.

Flanagan, M., 2014. Private needs, public space: public toilets provision in the Anglo-

Atlanticpatriarchal city: London, Dublin, Toronto and Chicago. Urban History, 41(2), pp. 265-

290.

Fulu, E., Warner, X., Miedema, S., Jewkes, R., Roselli, T. and Lang, J., 2013. Why Do Some

Men Use Violence Against Women and how Can We Prevent It?: Quantitative Findings from the

United Nations Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok:

UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and UNV.

Haas, S., and Timmerman, G., 2010. Sexual harassment in the context of double male

dominance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19(6), pp. 717-734.

Hall, C.M., 2013. Women and empowerment: Strategies for increasing autonomy. Routledge.

Hampton, K.N., Goulet, L.S. and Albanesius, G., 2015. Change in the social life of urban public

spaces: The rise of mobile phones and women, and the decline of aloneness over 30 years. Urban

Studies, 52(8), pp.1489-1504.

Heim LaFrombois, M., 2017. Blind spots and pop-up spots: A feminist exploration into the

discourses of do-it-yourself (DIY) urbanism. Urban Studies, 54(2), pp.421-436.

21GENDER AND PUBLIC SPACE

Horelli, L., 2017. Engendering urban planning in different contexts – successes, constraints and

consequences. European Planning Studies, 25(10), pp. 1779-1796.

Irschik, E. and Kail, E., 2013. Vienna: progress towards a fair shared city. Fair Shared Cities:

The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe, pp.292-329.

Iveson, K., 2013. Cities within the city: Do‐it‐yourself urbanism and the right to the

city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), pp.941-956.

Jacobs, J., 2016. The economy of cities. Vintage.

Jacobs, J.M. and Lees, L., 2013. Defensible Space on the Move: Revisiting the Urban Geography

of A lice C oleman. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), pp.1559-

1583.

Jafry, T., and Sulaiman, R., 2013. Gender-Sensitive Approaches to Extension Programme

Design. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 19(5), pp. 469-485. Available

Jayachandran, S., 2015. The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. economics, 7(1),

pp.63-88.

Johnson, A.J. and Glover, T.D., 2013. Understanding urban public space in a leisure

context. Leisure Sciences, 35(2), pp.190-197.

Karamessini, M. and Rubery, J. eds., 2013. Women and austerity: The economic crisis and the

future for gender equality (Vol. 11). Routledge.

Kelly, G., 2013. Women's access to education in the Third World: myths and realities. Acker, ed,

pp.81-89.

Horelli, L., 2017. Engendering urban planning in different contexts – successes, constraints and

consequences. European Planning Studies, 25(10), pp. 1779-1796.

Irschik, E. and Kail, E., 2013. Vienna: progress towards a fair shared city. Fair Shared Cities:

The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe, pp.292-329.

Iveson, K., 2013. Cities within the city: Do‐it‐yourself urbanism and the right to the

city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), pp.941-956.

Jacobs, J., 2016. The economy of cities. Vintage.