Analyzing SNAP Program Impact on Food Consumption (EC344 Project)

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/16

EC344 Semester Project

Professor Rodrigo Schneider

George Emmanuel Kalamotousakis

16-04-2019

IMPACT OF THE SNAP PROGRAM ON FOOD CONSUMPTION

Statement of Responsibility:

“I have not witnessed any wrongdoing, nor have I personally violated any conditions of the

Skidmore Honor Code while taking this examination.”

Signature:

George Emmanuel Kalamotousakis

1

Paraphrase This Document

Executive Summary

Hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition are major public health challenges affecting

many low-income Americans. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) serves

as the US agency to assist low-income sections of the US population towards improving food

security and improving nutrition. SNAP has grown rapidly over the past few years, with the

number of participants increasing by roughly 300% between 2000 to 2015. The dramatic

increase has led to a series of studies being conducted to investigate its impact on recipients’

food consumption habits.

Various researchers have proved that SNAP is highly effective at alleviating food

insecurity and improving nutrition. “SNAP has improved food security and reduced poverty for

millions of Americans” (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015). SNAP has helped “an average

of 45.8 million individuals per month in the year 2015” (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015).

The program has been found to have far-reaching short-term and long-term benefits on

participants from low-income households. A recent study suggests that “The ARRA (American

Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009) led to roughly a 12 percent increase in benefits for the

typical SNAP recipient and lifted roughly 8 percent, or 530,000 households, out of food

insecurity” (U.S. Departmentt of Agriculture, 2019). Food assistance to the low-income earners

“leads to a reduction in hunger rates and improvements in health and academic performance

among beneficiary children” (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019).

The primary aim of the current study was to investigate the impact of receiving SNAP

benefits on weekly household food expenditures. The study used the difference in differences

technique where subjects were studied for the differential impacts of SNAP program benefits on

food expenditure. The study examined the impact of SNAP benefits on food expenditures from

2

2000-2018, using an interaction variable that compares expenditures before 2009 with

expenditures from 2009 to 2018 (after an expansion of SNAP benefits took place). Regression

analysis (using OLS regression) was conducted for purposes of analyzing the data. The study

made use of nutrition survey data available at https://cps.ipums.org/cps/index.shtml.

A key finding of the study is that participation in the SNAP program impacts household

expenditures allocated to food. In general, respondents who received SNAP benefits spent about

$10 less per week on food than households that did not receive SNAP benefits. However,

household food expenditures were about $1.50 higher among respondents who received SNAP

benefits from 2009-2018. This appears to show that people who participate in the SNAP program

end up increasing resource allocation to food expenditure during the time period studied.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 1

Contents 2

Introduction 3

SNAP 4

Eligibility 4

Research Objective 4

Research questions 5

Limitations 5

Methodology 5

Regression Discontinuity Design 5

Assumptions of DID 6

Instruments 7

Data 7

Hypotheses 8

Null Hypothesis 1 8

Alternative Hypothesis 8

Results and Discussion 9

Results 9

Regression Discontinuity 9

Discussion 11

Conclusion 11

References 12

4

Paraphrase This Document

Introduction

The primary objectives of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) are

improvement of food security, reduction of hunger through enabling more access to food,

promoting consumption of healthy diets, and conducting nutrition education among low-income

Americans (Ratcliffe, McKernan, & Zhang, 2011). To realize the department’s objective, some

of the programs designed by USDA include the “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and

the National School Lunch and School Breakfast (School Meals) Programs” (Fraker and

Devaney, 2013).

SNAP is the largest program that assists people and families in the United States who are

suffering from hunger issues. “It offers nutrition assistance to millions of eligible, low-income

individuals and families” who are in need of it and “provides economic benefits to communities”

(U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015). It has “helped more than 40 million Americans” (Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018). SNAP is very well known for the Food Stamp Program

as well. SNAP is funded by the federal government and the different states who use it. The total

cost of SNAP sums up to approximately $70 billion USD per fiscal year (Nord & Prell, 2011).

After the 2009 expansion that occurred “food expenditures increased by 5.4% and food

insecurity declined by 2.2%” (Nord & Prell, 2011).

SNAP benefits can be enjoyed by almost all households with low incomes. Who receives

SNAP benefits is determined by the government and the eligibility criteria are the same across

the nation, although some states can alter specific rules of the program. An example is that in

some states have different qualifications of who can get SNAP depending on the “value of a

vehicle or a household they might own.” In most cases in order to be able to get SNAP one must

5

be making under 1,287 dollars per year. There are also specific “categories of people who are not

eligible for SNAP regardless of how small their income or assets may be” (U.S. Department of

Agriculture, 2015). These categories of people include “strikers, college students, legal

immigrants and illegal immigrants also are not eligible for SNAP” (U.S. Department of

Agriculture, 2015).

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities an “average SNAP recipient

receives $126 a month which equals $4.20 a day or $1.40 per meal” (Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities, 2018). Depending on the specific income of a household SNAP benefits

received are a bit different and offer a more suitable food program which is more appropriate to

it. This means that in some cases poorer households enjoy more benefits than wealthier

households (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018).

Today, the SNAP program is implemented through issuance of monthly benefits to

beneficiaries in the form of Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) which are used when making

purchases at selected stores (Carlson et al., 2017). In 2013 there was an estimated $275 per

benefits for each household per month, that is $133 per person (Schmier, 2015). However, the

program’s implementation and benefits have changed very little over time with just the same

framework adopted approximately 50 years ago being adopted in the program today (Kim,

2015). The foods included in the SNAP program include breads and cereals, fruits and

vegetables, meats, fish and poultry, dairy products, seeds and plants that produce food for

household consumption.

Many people across the country believe that SNAP has had positive effects, including

decreasing the hunger rate in the United States (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018).

SNAP had more than 42 million participants in the fiscal year 2017 which amounts to 13% of the

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

American population (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018). More than “68% of SNAP

participants were families with children.” SNAP has benefited also a lot of people who are

currently not in the workforce or are unemployed. SNAP helps the unemployed buy groceries so

they can support their family (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018).

Research Objective

The objective of this study is to examine how the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program influences food consumption among the low-income work force in the United States.

As such, using data from 2000-2018, a regression model is used to examine whether a

relationship exists between receipt of SNAP benefits and weekly household expenditures on food

after the expansion of the SNAP program that happened in 2009. In this particular research 2009

was identified as the cutoff point for performing this experiment. The year 2009 was selected

because that was the year that the expansion happened in the SNAP program and it would be an

ideal cutoff point because results would show clear differences of household expenditures on

food consumption for families that received SNAP before and after that point. Moreover, the

research adopts a DID (difference in differences) design which upon proper design,

implementation and analysis, provides an unbiased estimate of the local treatment effect, making

it approximately as good as a randomized experiment when trying to measure a treatment effect.

Research questions

After addressing the research objective, we hope to answer the following questions:

7

Paraphrase This Document

Is there a difference between the household food expenditures of SNAP beneficiaries and

those who do not receive SNAP benefits?

Does receiving SNAP benefits affect the beneficiaries’ food consumption?

Eligibility for SNAP Benefits

The SNAP program is funded by the federal government and eligibility criteria are

determined by the federal government. For households to be eligible for SNAP benefits, they

must have a monthly income less that 130 percent of the official poverty line. The eligible

households receive SNAP benefits every month. Since 2004, eligible households have benefited

in form of Electronic Benefit Transfer cards, which they can use to purchase food items.

The sample in the data which was used for this study was restricted to a “subsample of

the data with a higher probability of being eligible for participation in the SNAP program. Only

households with gross income below 130% of the poverty line were considered for the analyses”

(Caprio, & Boonsaeng & Zhen & Okrent, 2014). “The calculation of the poverty line was

conducted using the 1998-2009 poverty guidelines issued by the U.S. Department of Health &

Human Services (HHS)” (Caprio, & Boonsaeng & Zhen & Okrent, 2014). The SNAP benefits

are intended to “help improve nutrition among low-income households in the U.S” (Caprio, &

Boonsaeng & Zhen & Okrent, 2014).

.

Limitations

The model used in this study has estimated effects which are only unbiased as long as the

functional form of the relationship between the treatment and outcome is correctly modeled

otherwise the results are prone to bias. Moreover, other treatments might contaminate the chosen

8

t variable if different treatments occur on the same cut-off points of the original assignment

variables.

Limitations that are identified in this research is that the treated group differs from

untreated group in important ways and so interaction is correlated with error. Additionally, there

are time trends such as the expenditures that were already rising faster among the newly eligible

group. In the research conducted something changed at the same time so one can’t tell what is

responsible for the results obtained.

Methodology

Difference in Differences

The difference in differences (DID) design is a statistical analysis technique used in

quantitative research. It tries to emulate the experimental design technique of research. Using the

difference in differences technique, we investigate the differential impact of a treatment on an

experimental group in comparison with the control group in a natural experiment. The impact of

treatment on the response variables is calculated. That is, the average change in the response

variable over time on the experimental group is compared to the average change in the response

variable over time for the control group. In this particular research, they DID method is useful

because the SNAP program changed in 2009. Testing the effects of the SNAP expansion is

similar to studying the results of an experiment by comparing the experimental group – SNAP

recipients after 2009 – to the control group households before 2009.

The essence of this technique of research is that it helps in mitigating some effects of

extraneous variables and bias as a result of group selection. This is because the difference in

differences technique makes use of randomization in the selection of groups and subjects.

However, the difference in differences method may still be subject to some biases, for instance

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

regression bias, reverse causality bias and the omitted variable bias, which I discuss in greater

detail in the “Discussion” section.

To guarantee the accuracy of the DID model, the characteristics of subjects of the

experimental and control groups are expected to remain unchanged over periods. This is because

extraneous factors such as change in subject characteristics over time may adversely compromise

results of the model.

Instruments

For this assignment, the STATA statistical software will be utilized for analysis. To

perform DID in STATA one can use just a normal difference in differences regression model

which in our case will be regressing expenditure against the treatment variable, post-treatment

variable and the interaction variable together and independently to examine their relationship

with expenditure as well as develop a predictive model. After defining all of our variables, our

multiple regression model will be:

Food expendituresit = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑃𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑡t + 𝛽2𝑃𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑡t ∗ (𝑇𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑡𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑖) + 𝛽3Interaction𝑖t +

𝛽4𝑋𝑖𝑡 + 𝛬𝑖 + 𝜖𝑖t

Where a represents a constant/y intercept which are numbers you are going to estimate.

𝛽1 is coefficient which shows the relationship of how much savings change for people who did

not have their food expenditures affected. In addition to this 𝛽2 showed how different were the

treatment and control before the expansion and shows 𝛽3 how much more did the savings of the

treatment group change than the savings of the control group. 𝛽4 represents all the other controls

that you want. Λi in the equation represents the time invariant εi = time variant.

10

Paraphrase This Document

Post is a dummy variable equal to 1 after 2009 which is the cut-off point in our

hypothesis and Interaction is the product of the two other dummy variables. Moreover, 𝛬𝑖 is a

year fixed effect 𝑋𝑖𝑡 is a vector of controls (number of children, family size).

t represents could be years from 2000 until 2018. Sub i = means that is varies across

observations and sub t it means that is varies across time

Food expenditures it which includes sub i + sub t, varies for individuals and time t is the

amount saved by an individual I in year t. If the individual received SNAP benefits or not after

2009.

Post does not vary among individuals, but varies over time, dummy variable equal to 1 if

for years after 2009. Treatment varies for individuals but does not vary over time, a dummy

variable equal to 1 if an individual received SNAP benefits, and 0 if he is not.

Interaction changes through time and for individuals. It is dummy variable to the product

of post and treatment of the dummy variable post and treatment. X varies among people and time

and a only changes individuals. ε which is the Error must have an i because it is individual

component and It changes for individuals in that specific situation.

Furthermore, fixed effects are a way of controlling characteristic about individuals that

do not changed over time and their race, gender do not change as well. Fixed effects are

variables that do no change over time. Location is also very common fixed effect.

The difference in differences technique operates on a set of assumptions, similar to the

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) technique. In addition to the assumptions shared with the OLS

model, DID assumes a parallel trend. The parallel trend assumption requires that in the absence

of treatment, the difference between the experimental and control groups remains constant over

time. Violation of this assumption shall lead to biased estimation of the treatment effect.

11

Data

For this study, I used data from the IPUMS’ Current Population Survey (CPS), which can

be found at https://cps.ipums.org/cps/index.shtml. The website consolidates and harmonizes

census and survey data acquired by the monthly U.S. labor force survey, called the Current

Population Survey (CPS). Each month, the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics

survey approximately 60,000 households across the United States, gathering demographic and

employment data and providing an estimate of the unemployment rate. IPUMS data is available

for free and can be obtained from the website. For this study, I used data on household food

expenditures and food security, which is released in December of each year.

The dataset used for this study contained 2,524,267 observations (of individual

households) and 12 variables. The dependent variable was a self-reported measure of weekly

household food expenditures. The main independent variable was a binary variable that

measured whether or not a household receives SNAP benefits. Other variables included the

respondent’s state of residence, family income, number of children in the household, educational

attainment, and labor force status.

Research Questions/Hypotheses

Over the course of this study, I tested three research questions about the relationship

between receiving SNAP benefits and household food expenditures.

First, I examined the relationship between receiving SNAP benefits and weekly

household food expenditures using basic linear (OLS) regression. Second, I examined the same

relationship using the DID method and an interaction variable that combined the SNAP benefits

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

variable with the time period 2009-2018 (after the 2009 expansion of benefits to jobless

individuals without children). Finally, I examined the effect of controlling for the respondents’

education level and the number of children in the household on the DID estimate.

These research questions can also be framed as the following hypotheses:

1) Null Hypothesis 1

There is no relationship between SNAP and weekly household food expenditures.

Alternative Hypothesis

There is a relationship between SNAP and weekly household food expenditures.

2) Null Hypothesis 2

There is no relationship between the interaction term and weekly household food

expenditures.

Alternative hypothesis

There is a relationship between the interaction term and weekly household food

expenditures.

3) Null Hypothesis 3

Including controls for educational level and number of children in the household has no

significant effect on the relationship between the interaction term and food expenditures.

Alternative Hypothesis

Including controls for educational level and number of children in the household has a

significant effect on the relationship between the interaction term and food expenditures.

13

Paraphrase This Document

Results and Discussion

Results

Relationship between SNAP and food expenditures

VARIABLE

S

expenditure

s

Standard errors in

parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

snap -9.645***

-0.307

Constant 145.1***

-0.0923

Observations 1,561,308

R-squared 0.001

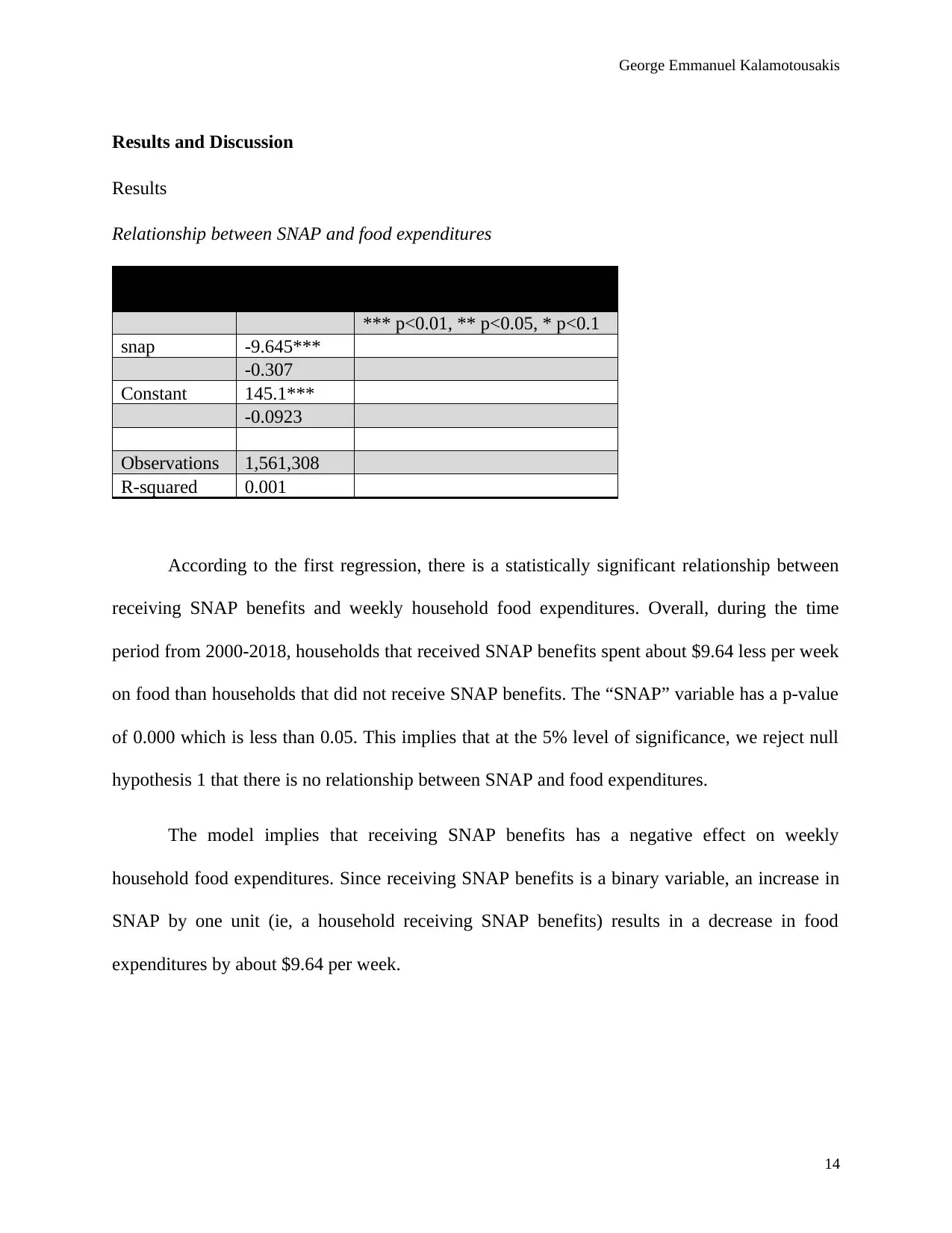

According to the first regression, there is a statistically significant relationship between

receiving SNAP benefits and weekly household food expenditures. Overall, during the time

period from 2000-2018, households that received SNAP benefits spent about $9.64 less per week

on food than households that did not receive SNAP benefits. The “SNAP” variable has a p-value

of 0.000 which is less than 0.05. This implies that at the 5% level of significance, we reject null

hypothesis 1 that there is no relationship between SNAP and food expenditures.

The model implies that receiving SNAP benefits has a negative effect on weekly

household food expenditures. Since receiving SNAP benefits is a binary variable, an increase in

SNAP by one unit (ie, a household receiving SNAP benefits) results in a decrease in food

expenditures by about $9.64 per week.

14

Relationship between interaction variable and expenditure on food, controlling for education

and number of children in household

VARIABLES expenditures Standard errors in parentheses

-1

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

interaction 1.629***

-0.615

snap -12.48***

-0.449

post 13.46***

-0.188

Constant 139.7***

-0.119

Observations 1561308

R-squared 0.004

15

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

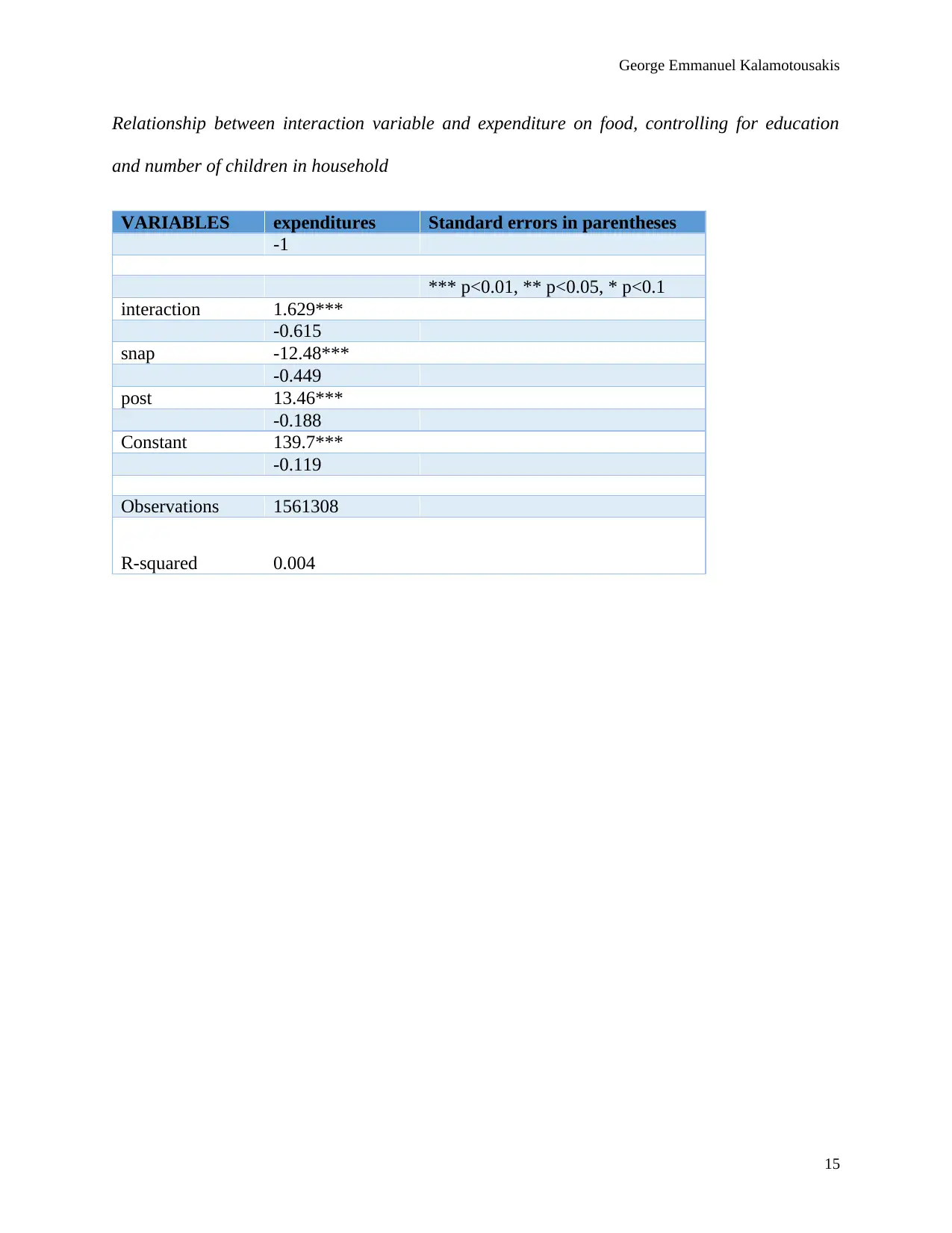

According to the regression in the table above (which tests hypothesis 2), there is a

statistically significant relationship between the interaction variable and weekly household food

expenditures (without including controls for education level and the number of children in the

household). Households that received SNAP benefits during the time period 2009-2018 spent

about $1.63 more per week than other households. The interaction variable has a p-value of

0.008 which is less than 0.05. This implies that at the 5% level of significance, we reject null

hypothesis 2 that there is no relationship between the interaction term and weekly household

food expenditures.

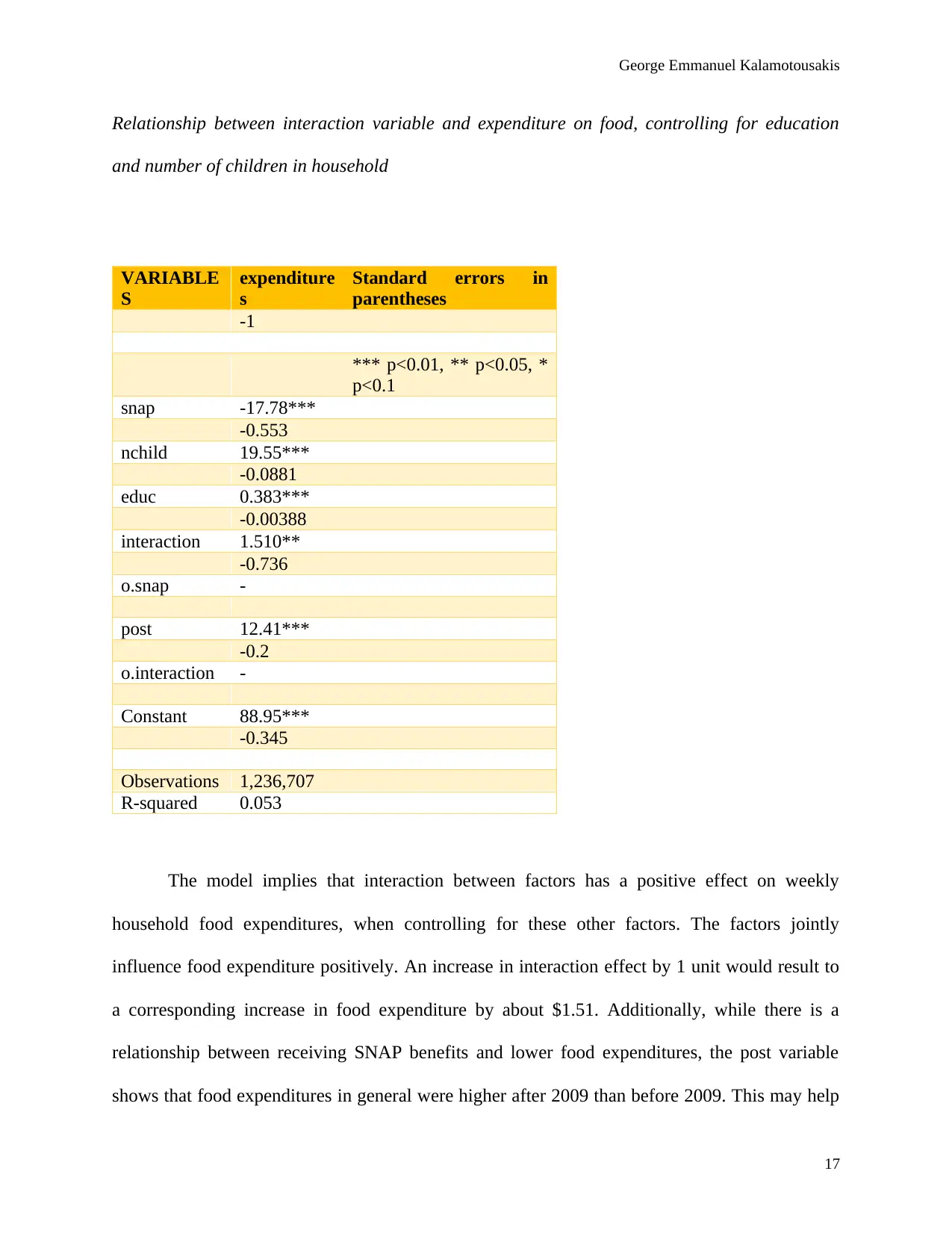

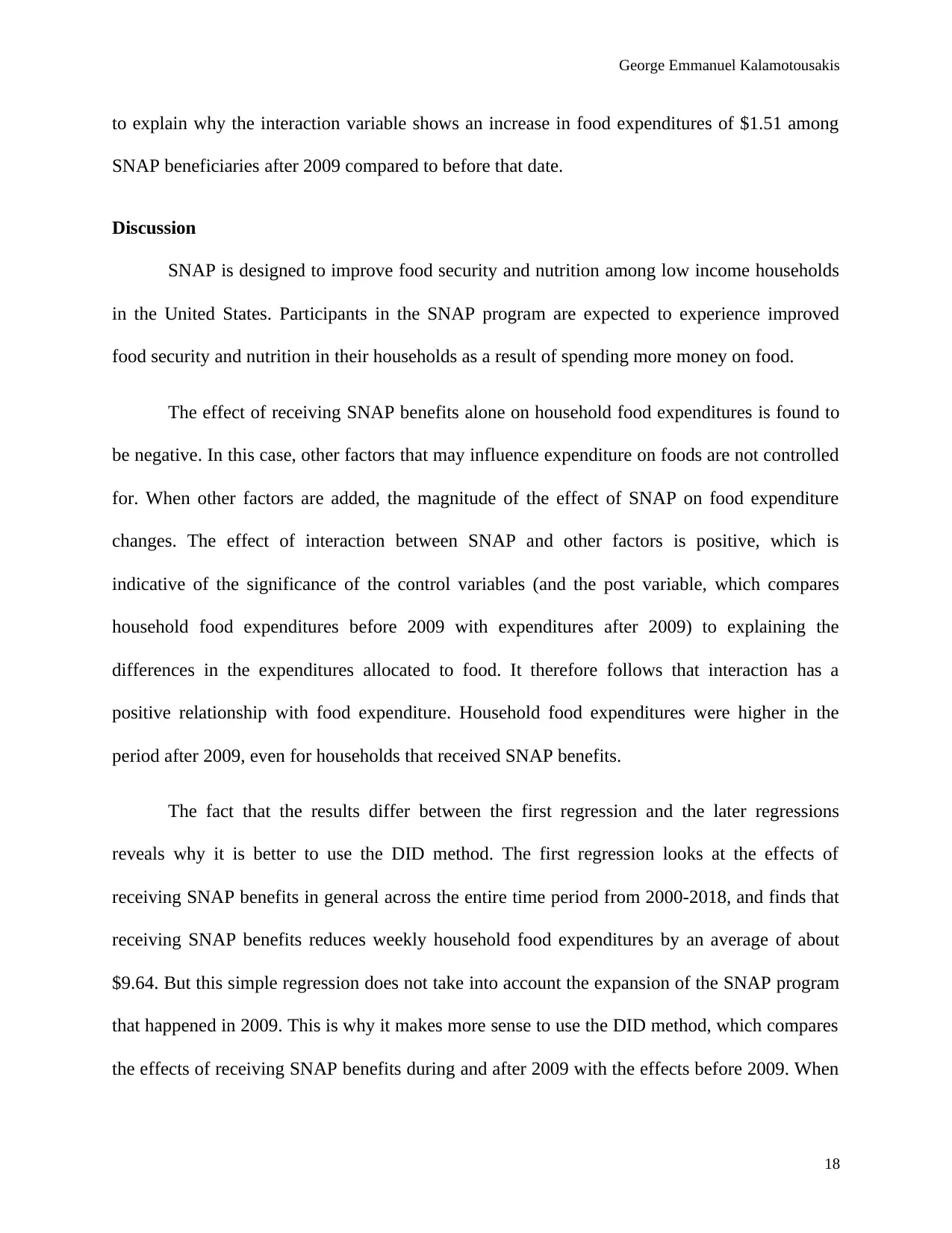

According to the regression in the table below (which tests hypothesis 3), there is a

statistically significant relationship between the interaction variable and weekly household food

expenditures when controlling for education level and the number of children in the household.

Households that received SNAP benefits during the time period 2009-2018 spent about $1.51

more per week than other households. The interaction variable has a p-value of 0.04 which is less

than 0.05, so this result remains statistically significant even after including the controls.

However, these results are slightly different from the previous regression (which did not include

any controls). After controlling for education and the number of children in a household,

receiving SNAP benefits increases weekly expenditures on food.

16

Paraphrase This Document

Relationship between interaction variable and expenditure on food, controlling for education

and number of children in household

VARIABLE

S

expenditure

s

Standard errors in

parentheses

-1

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, *

p<0.1

snap -17.78***

-0.553

nchild 19.55***

-0.0881

educ 0.383***

-0.00388

interaction 1.510**

-0.736

o.snap -

post 12.41***

-0.2

o.interaction -

Constant 88.95***

-0.345

Observations 1,236,707

R-squared 0.053

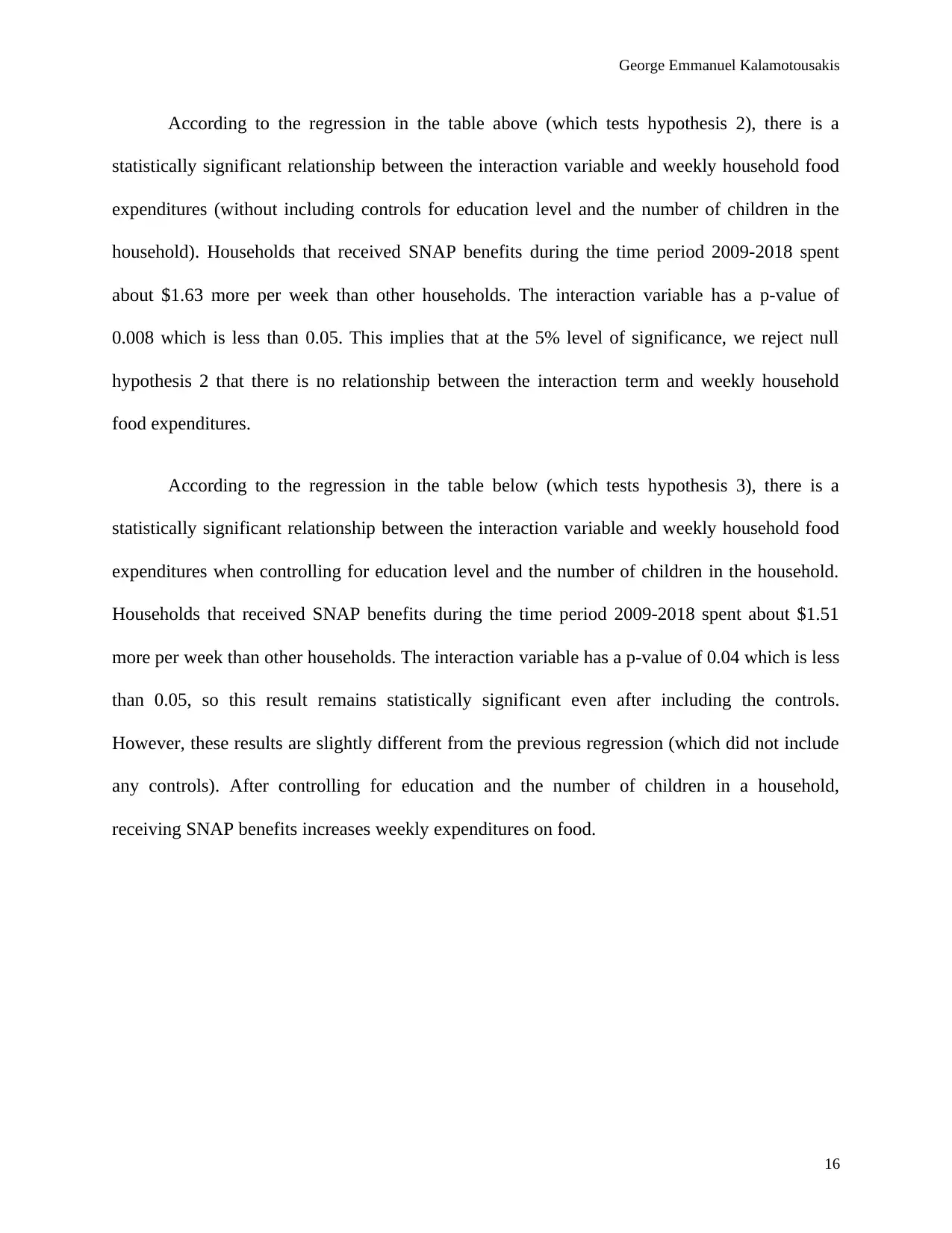

The model implies that interaction between factors has a positive effect on weekly

household food expenditures, when controlling for these other factors. The factors jointly

influence food expenditure positively. An increase in interaction effect by 1 unit would result to

a corresponding increase in food expenditure by about $1.51. Additionally, while there is a

relationship between receiving SNAP benefits and lower food expenditures, the post variable

shows that food expenditures in general were higher after 2009 than before 2009. This may help

17

to explain why the interaction variable shows an increase in food expenditures of $1.51 among

SNAP beneficiaries after 2009 compared to before that date.

Discussion

SNAP is designed to improve food security and nutrition among low income households

in the United States. Participants in the SNAP program are expected to experience improved

food security and nutrition in their households as a result of spending more money on food.

The effect of receiving SNAP benefits alone on household food expenditures is found to

be negative. In this case, other factors that may influence expenditure on foods are not controlled

for. When other factors are added, the magnitude of the effect of SNAP on food expenditure

changes. The effect of interaction between SNAP and other factors is positive, which is

indicative of the significance of the control variables (and the post variable, which compares

household food expenditures before 2009 with expenditures after 2009) to explaining the

differences in the expenditures allocated to food. It therefore follows that interaction has a

positive relationship with food expenditure. Household food expenditures were higher in the

period after 2009, even for households that received SNAP benefits.

The fact that the results differ between the first regression and the later regressions

reveals why it is better to use the DID method. The first regression looks at the effects of

receiving SNAP benefits in general across the entire time period from 2000-2018, and finds that

receiving SNAP benefits reduces weekly household food expenditures by an average of about

$9.64. But this simple regression does not take into account the expansion of the SNAP program

that happened in 2009. This is why it makes more sense to use the DID method, which compares

the effects of receiving SNAP benefits during and after 2009 with the effects before 2009. When

18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

we include the interaction term, we see that receiving SNAP benefits actually increases weekly

household food expenditures by about $1.51 (when controlling for other factors).

Still, this study has several limitations. For one thing, an increase of $1.51 may not seem

like much. However, this depends on what a given household’s typical weekly food expenditures

are. An increase in spending of $1.51 is much more significant for a poor household that only

spends $40 or $50 per week on food, and in that case receiving SNAP benefits may make a

difference to that family’s nutrition. So, the effect of such an increase depends on how much a

household was spending on food before receiving SNAP benefits.

Additionally, just because household food expenditures are slightly higher does not mean

that the SNAP program has necessarily achieved its goals. For example, maybe people still aren’t

eating nutritious food for some reason. Further research will be necessary to determine what

types of people SNAP recipients are buying and whether or not receiving SNAP benefits leads to

an increase in nutrition and overall health.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to examine the impact of the SNAP program on weekly

household food expenditures. Among participants in the SNAP program after 2009, receiving

SNAP benefits is found to increase household expenditures allocated to food by about $1.51 per

week. Participation in the SNAP program increases food expenditure share by about 15% and it

is also increases utility share by about 5% according to the United States Department of

Agriculture (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015). Food expenditure is “data set that measures

the U.S. food system, quantifying the value of food acquired in the United States by type of

19

Paraphrase This Document

product, outlet, and purchaser” (United States Department of Agriculture, 2019). Utility share is

the “share of total household expenditure (as a proxy of income) spent on food which indicates

that the poorer and more vulnerable a household, the larger the share of household income spent

on food” (Data4Diets, 2014).

The results of this study contribute to past research and existing literature on the impacts

of SNAP participation on food expenditures. This study did not, however, investigate the impact

that participation in the SNAP program has on household spending on non-food commodities.

Research ought to be done on this as some non-food commodities such as medication help

improve nutrition.

A better analysis of the impacts of SNAP participation on food security and nutrition

could be arrived at given some innovations. First, while SNAP is a national program, studying its

effects in individual states would provide greater insights into its strengths and weaknesses.

Since different states have different industries and natural resources, as well as different levels of

poverty, unemployment, and education, it would be useful to study the effects of a program like

SNAP on a state or even local level. Finally, nutritional awareness ought to be conducted in

order to have more people participating in the SNAP program, which may help researchers study

the impact of the program in the future.

20

References

Carlson, A., Lino, M., Juan, W., Hanson, K., and Basiotis, P. (2017). Thrifty Food Plan.

Retrieved from:

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/FoodPlans/MiscPubs/TFP2006Report.pdf

Caprio, C. E., Boonsaeng, T., Zhen, C., & Okrent, A. M. (2014). The Effect of

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program on Food and Nonfood Spending Among

Low-Income Households. Retrieved April 03, 2019, from

https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/170650/files/AAEApaper_SNAP_Bounds.pdf

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018). The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program (SNAP). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from

https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/policybasics-foodstamps.pdf

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018, February 26). Chart Book: SNAP Helps

Struggling Families Put Food on the Table. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from

https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/chart-book-snap-helps-struggling-

families-put-food-on-the-table

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018, December 03). A Closer Look at Who

Benefits from SNAP: State-by-State Fact Sheets. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from

https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-closer-look-at-who-benefits-from-snap-

state-by-state-fact-sheets#Alabama

Data4Diets. (2016). Household food expenditure share % of total spending. Retrieved

April 03, 2019, from https://inddex.nutrition.tufts.edu/data4diets/indicator/household-

food-expenditure-share

Eligibility.com. (2019, February 22). Food Stamps Eligibility - SNAP Program

Eligibility Help. Retrieved April 03, 2019, from https://eligibility.com/food-stamps

Fraker, T. & Devaney, B. (2013). The Effect of Food Stamps on Food Expenditures: An

Assessment of Findings from the Nationwide Food Consumption Survey. 71(1), pp. 124-

130. DOI: DOI: 10.2307/1241778

Hoynes, H., McGranahan, L., Schanzenbach, K. & Diane. A. (2014). SNAP and Food

Consumption. Five Decades of Food Stamps, 3(2), pp 2-17.

Kim, K. (2015). Three Essays on the Impact of Government Assistance Programs on

Economic Behaviors of Vulnerable Households. Family and Economic Issues, 30(4),

pp.357-371

21

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Nord, M., & Prell, M. (2011, April). Food Security Improved Following the 2009 ARRA

Increase in SNAP Benefits. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=44839

Piana, V. (2014). Consumer Theory: The Neoclassical Model and Its Opposite

Evolutionary Alternative. Economics, 4(1), pp. 1-7.

Rosenbaum, D. (2013). The Relationship Between SNAP and Work Among Low-Income

Households. Policy Priorities, 1(4).

Ruth, M. & Cheryll, R. (2017). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Nutrition

and Food Access. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780128044452

Senal, W. Reimer, J. & West, T. (2015). How Does the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program Affect the U.S. Economy? Agricultural and Resource

Economics Review, 4(3), pp. 233-252. DOI: /10.1017/S1068280500005049

Ratcliffe, C., McKernan, S. & Zhang, S. (2011). How Much Does the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity? Agricultural Economics, 93(4),

pp. 1082–1098.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2019). LONG-TERM BENEFITS OF THE

SUPPLEMENTAL NUTRITION ASSISTANCE PROGRAM. (2015, December).

Retrieved March 24, 2019, from

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/

SNAP_report_final_nonembargo.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture. (2019). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program (SNAP). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from

https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

United States Department of Agriculture. (2019). Food Expenditure Series. Retrieved

April 03, 2019, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-expenditure-series/

Verick, S. & Islam, I. (2010). The Great Recession of 2008-2009: Causes, Consequences

and Policy Responses. Employment Analysis and Research, 1(4934), pp. 236-251.

22

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.