Economics Report: Globalization, Outsourcing, and the US Job Market

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/04

|8

|2098

|23

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the impact of outsourcing on white-collar jobs in the United States, challenging the initial fears of a widespread "job apocalypse" due to offshoring. While globalization and free trade led to increased outsourcing, particularly to countries like India, companies have also faced challenges such as time zone differences, language barriers, and coordination issues, leading some to prefer onshore outsourcing within the US. The report explores the shift of jobs to less expensive locations within the country and the impact of technological advancements and automation on the job market. It examines the evolution of outsourcing, the role of factors beyond labor costs, and the ongoing adaptation of workers, companies, and governments to these changes, concluding that the shift is evolutionary, not revolutionary, and creates new opportunities. The report references an article from The New York Times and other sources to support its findings.

Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Increased globalization and free trade practices led to the evolution of outsourcing as an

effective means for companies to minimize costs and/or maximize profits in a highly

competitive environment (ConnectAmericas). Offshore outsourcing was mainly the

recognition of trade based on comparative advantage. American companies realized the

potential of offshore outsourcing to countries like India which offered huge talent pool with

requisite skillset at a much lower cost (Josephson). Outsourcing allowed American

companies to focus more on their core activities which ultimately resulted in better value for

money products/services aimed at customers.

However, the companies were sometimes fumbling with the economic costs of labor savings

like time zone issues (especially for critical deadline or real-time work), language barriers

resulting in communication hurdles, legal problems as well as coordination issues (The New

York Times). So, this realization led to some companies preferring onshore outsourcing. In

essence, where understanding of the business and/or understanding of the customers’

expectations and experience are critical, the jobs directly related to these areas have been

retained within the economy, albeit, shifting from high-cost places like Manhattan to low-cost

places like Columbus. While it was feared that offshoring would lead to shift of white-collar

jobs to other countries, this did not happen altogether.

Another threat to American job market is the technological advancement and automation

(The New York Times). While technology has resulted in increased offshore freelancing, rise

in artificial intelligence and robotics could lead to more job losses. However, these changes

are all evolutionary, giving enough time to people, companies and government to adapt and

blend into more productive job opportunities.

Increased globalization and free trade practices led to the evolution of outsourcing as an

effective means for companies to minimize costs and/or maximize profits in a highly

competitive environment (ConnectAmericas). Offshore outsourcing was mainly the

recognition of trade based on comparative advantage. American companies realized the

potential of offshore outsourcing to countries like India which offered huge talent pool with

requisite skillset at a much lower cost (Josephson). Outsourcing allowed American

companies to focus more on their core activities which ultimately resulted in better value for

money products/services aimed at customers.

However, the companies were sometimes fumbling with the economic costs of labor savings

like time zone issues (especially for critical deadline or real-time work), language barriers

resulting in communication hurdles, legal problems as well as coordination issues (The New

York Times). So, this realization led to some companies preferring onshore outsourcing. In

essence, where understanding of the business and/or understanding of the customers’

expectations and experience are critical, the jobs directly related to these areas have been

retained within the economy, albeit, shifting from high-cost places like Manhattan to low-cost

places like Columbus. While it was feared that offshoring would lead to shift of white-collar

jobs to other countries, this did not happen altogether.

Another threat to American job market is the technological advancement and automation

(The New York Times). While technology has resulted in increased offshore freelancing, rise

in artificial intelligence and robotics could lead to more job losses. However, these changes

are all evolutionary, giving enough time to people, companies and government to adapt and

blend into more productive job opportunities.

3Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

References

ConnectAmericas. How did the concept of outsourcing begin? 1st Oct 2019. 1st Oct 2019.

<https://connectamericas.com/content/how-did-concept-outsourcing-begin>.

Josephson, Amelia. The Pros and Cons of Outsourcing. 1st Oct 2019. 18th May 2019.

<https://smartasset.com/career/the-pros-and-cons-of-outsourcing>.

The New York Times. The White-Collar Job Apocalypse That Didn’t Happen . 1st Oct 2019.

27th Sept 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/27/business/economy/jobs-

offshoring.html>.

References

ConnectAmericas. How did the concept of outsourcing begin? 1st Oct 2019. 1st Oct 2019.

<https://connectamericas.com/content/how-did-concept-outsourcing-begin>.

Josephson, Amelia. The Pros and Cons of Outsourcing. 1st Oct 2019. 18th May 2019.

<https://smartasset.com/career/the-pros-and-cons-of-outsourcing>.

The New York Times. The White-Collar Job Apocalypse That Didn’t Happen . 1st Oct 2019.

27th Sept 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/27/business/economy/jobs-

offshoring.html>.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Attached Article

The White-Collar Job Apocalypse That

Didn’t Happen

Economists once warned that office jobs in the United States would soon follow factory jobs

in moving overseas. New research suggests that jobs may be moving to other parts of the

country instead.

Image

More than a decade ago, Ron Kincaid worked in an office where the relocation of its jobs

overseas was openly considered. But he kept that job, and has found others

since.CreditCreditMaddie McGarvey for The New York Times

By Ben Casselman

Attached Article

The White-Collar Job Apocalypse That

Didn’t Happen

Economists once warned that office jobs in the United States would soon follow factory jobs

in moving overseas. New research suggests that jobs may be moving to other parts of the

country instead.

Image

More than a decade ago, Ron Kincaid worked in an office where the relocation of its jobs

overseas was openly considered. But he kept that job, and has found others

since.CreditCreditMaddie McGarvey for The New York Times

By Ben Casselman

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Published Sept. 27, 2019Updated Sept. 29, 2019, 12:14 p.m. ET

o

Ron Kincaid remembers what it was like to worry that his job would be sent

overseas.

Globalization had ravaged American manufacturing, and now, in the first years of the new

century, economists were warning that offshoring — the relocating of work to other countries

— was coming for white-collar jobs like his as well.

For Mr. Kincaid, the evidence seemed close at hand; he overheard conversations through his

boss’s open office door about which foreign contractors should take over which jobs at the

automobile finance company where he worked. He remembers the meeting where an

executive mused that perhaps the whole department could be shipped to India. He wondered

how much notice he would get, and what his severance would be, and how he would tell his

wife.

Mr. Kincaid didn’t need to have that conversation. He kept his job. While he later left the

company, he has remained steadily employed a decade and a half later. And the broader jobs

apocalypse never materialized.

Companies did move millions of office jobs to India, the Philippines and other places where

they could pay workers less. But those job losses were more than balanced by growth

elsewhere in the economy.

A widely covered 2007 study by Alan S. Blinder, a Princeton economist and former Clinton

administration official, estimated that a quarter or more of jobs were vulnerable within the

next decade. But many companies discovered that labor savings were offset by other factors:

time differences, language barriers, legal hurdles and the simple challenge of coordinating

work half a world away. In some cases, companies decided they were better off moving jobs

to less expensive parts of the United States rather than out of the country.

“Where in retrospect I missed the boat is in thinking that the gigantic gap in labor costs

between here and India would push it to India rather than to South Dakota,” Mr. Blinder said

in a recent interview. “There were other aspects of the costs to moving the activities that we

weren’t thinking about very much back then when people were worrying about offshoring.”

In his 2007 paper, Mr. Blinder scored occupations on a 1-to-100 scale based on how easily

they could be sent offshore. Bus drivers and electricians scored near the bottom. There is

pretty much no way to do that work from afar. On the other end of the spectrum were

computer programmers and telemarketers — jobs that in many cases were already being sent

overseas.

In a follow-up paper released Friday, another economist, Adam Ozimek, revisited Mr.

Blinder’s analysis to see what had happened over the past decade. Some job categories that

Published Sept. 27, 2019Updated Sept. 29, 2019, 12:14 p.m. ET

o

Ron Kincaid remembers what it was like to worry that his job would be sent

overseas.

Globalization had ravaged American manufacturing, and now, in the first years of the new

century, economists were warning that offshoring — the relocating of work to other countries

— was coming for white-collar jobs like his as well.

For Mr. Kincaid, the evidence seemed close at hand; he overheard conversations through his

boss’s open office door about which foreign contractors should take over which jobs at the

automobile finance company where he worked. He remembers the meeting where an

executive mused that perhaps the whole department could be shipped to India. He wondered

how much notice he would get, and what his severance would be, and how he would tell his

wife.

Mr. Kincaid didn’t need to have that conversation. He kept his job. While he later left the

company, he has remained steadily employed a decade and a half later. And the broader jobs

apocalypse never materialized.

Companies did move millions of office jobs to India, the Philippines and other places where

they could pay workers less. But those job losses were more than balanced by growth

elsewhere in the economy.

A widely covered 2007 study by Alan S. Blinder, a Princeton economist and former Clinton

administration official, estimated that a quarter or more of jobs were vulnerable within the

next decade. But many companies discovered that labor savings were offset by other factors:

time differences, language barriers, legal hurdles and the simple challenge of coordinating

work half a world away. In some cases, companies decided they were better off moving jobs

to less expensive parts of the United States rather than out of the country.

“Where in retrospect I missed the boat is in thinking that the gigantic gap in labor costs

between here and India would push it to India rather than to South Dakota,” Mr. Blinder said

in a recent interview. “There were other aspects of the costs to moving the activities that we

weren’t thinking about very much back then when people were worrying about offshoring.”

In his 2007 paper, Mr. Blinder scored occupations on a 1-to-100 scale based on how easily

they could be sent offshore. Bus drivers and electricians scored near the bottom. There is

pretty much no way to do that work from afar. On the other end of the spectrum were

computer programmers and telemarketers — jobs that in many cases were already being sent

overseas.

In a follow-up paper released Friday, another economist, Adam Ozimek, revisited Mr.

Blinder’s analysis to see what had happened over the past decade. Some job categories that

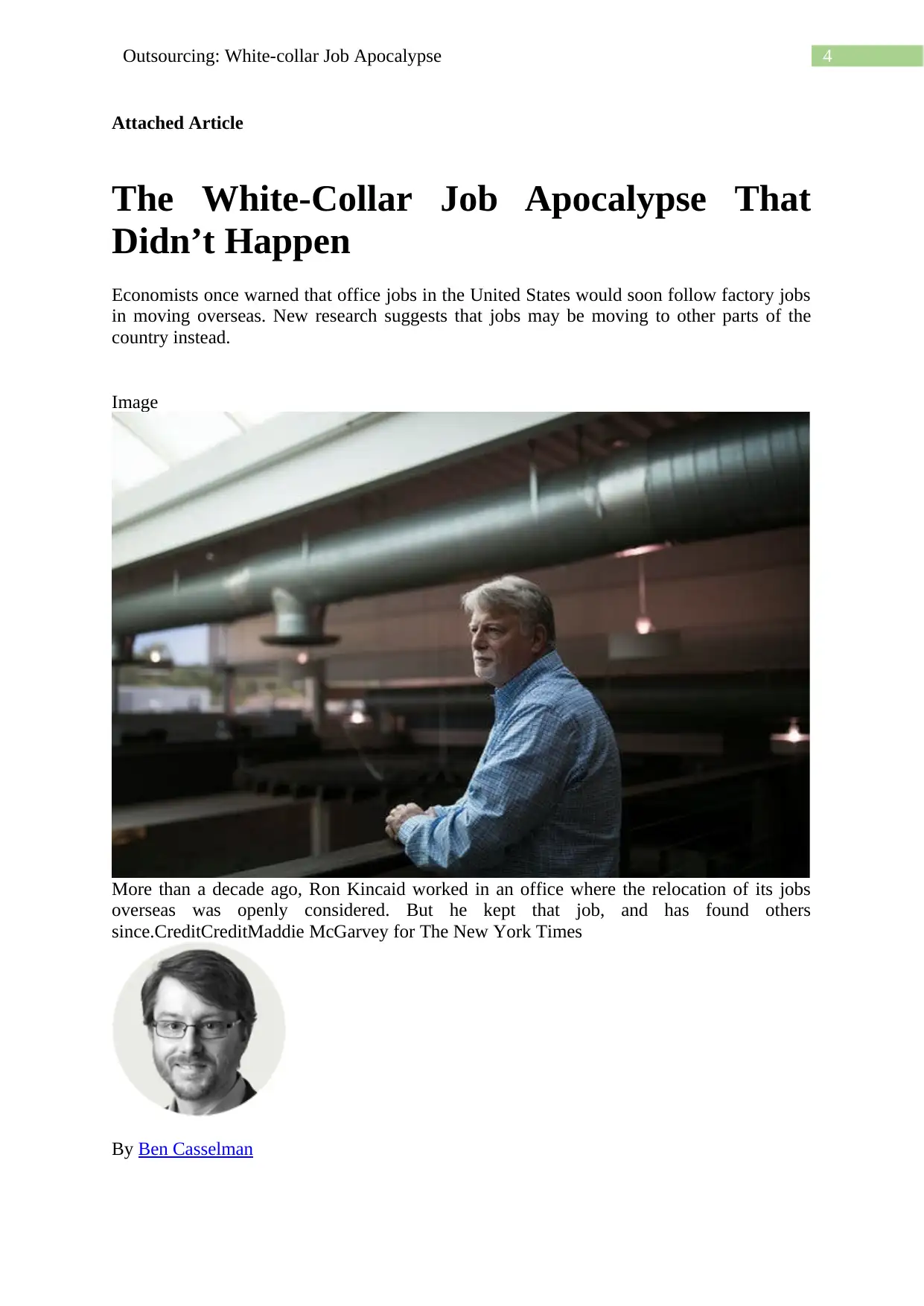

6Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

Mr. Blinder identified as vulnerable, like data-entry workers, have seen a decline in United

States employment. But the ranks of others, like actuaries, have continued to grow.

Image

Mr. Kincaid is now a software engineer at Nexient in Columbus, Ohio. The company cites

the fact that its employees are all in the United States and can easily collaborate as a selling

point with clients.CreditMaddie McGarvey for The New York Times

Over all, of the 26 occupations that Mr. Blinder identified as “highly offshorable” and for

which Mr. Ozimek had data, 15 have added jobs over the past decade and 11 have cut them.

Altogether, those occupations have eliminated fewer than 200,000 jobs over 10 years, hardly

the millions that many feared. A second tier of jobs — which Mr. Blinder labeled

“offshorable” — has actually added more than 1.5 million jobs.

But Mr. Blinder didn’t miss the mark entirely, said Mr. Ozimek, who is chief economist at

Upwork, an online platform for hiring freelancers. The new study found that in the jobs that

Mr. Blinder identified as easily offshored, a growing share of workers were now working

from home. Mr. Ozimek said he suspected that many more were working in satellite offices

or for outside contractors, rather than at a company’s main location. In other words,

technology like cloud computing and videoconferencing has enabled these jobs to be done

remotely, just not quite as remotely as Mr. Blinder and many others assumed.

One telling example is call centers. Telemarketing jobs have declined sharply in the United

States since 2007, as much of the work was sent overseas. But the number of customer

service representatives has continued to grow.

Mr. Blinder identified as vulnerable, like data-entry workers, have seen a decline in United

States employment. But the ranks of others, like actuaries, have continued to grow.

Image

Mr. Kincaid is now a software engineer at Nexient in Columbus, Ohio. The company cites

the fact that its employees are all in the United States and can easily collaborate as a selling

point with clients.CreditMaddie McGarvey for The New York Times

Over all, of the 26 occupations that Mr. Blinder identified as “highly offshorable” and for

which Mr. Ozimek had data, 15 have added jobs over the past decade and 11 have cut them.

Altogether, those occupations have eliminated fewer than 200,000 jobs over 10 years, hardly

the millions that many feared. A second tier of jobs — which Mr. Blinder labeled

“offshorable” — has actually added more than 1.5 million jobs.

But Mr. Blinder didn’t miss the mark entirely, said Mr. Ozimek, who is chief economist at

Upwork, an online platform for hiring freelancers. The new study found that in the jobs that

Mr. Blinder identified as easily offshored, a growing share of workers were now working

from home. Mr. Ozimek said he suspected that many more were working in satellite offices

or for outside contractors, rather than at a company’s main location. In other words,

technology like cloud computing and videoconferencing has enabled these jobs to be done

remotely, just not quite as remotely as Mr. Blinder and many others assumed.

One telling example is call centers. Telemarketing jobs have declined sharply in the United

States since 2007, as much of the work was sent overseas. But the number of customer

service representatives has continued to grow.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

The two occupations may seem similar. But the different employment trend may reflect both

cultural and logistical differences. Telemarketers are essentially selling products and often

working from a script. Customer service and other call-center work like tech support often

require a more nuanced understanding of the customer experience.

Deb Thorpe, senior vice president for operations for Kelly Services, a staffing company, said

that rather than move customer service jobs abroad, many companies were trying to find cost

efficiencies by putting offices in less expensive parts of the country or letting workers take

calls from home.

“The call center business in the U.S. is still pretty healthy,” Ms. Thorpe said.

Mr. Kincaid, now 59 and living in Columbus, Ohio, has seen all those patterns up close.

Shortly after his own near miss with offshoring, he was hired by another American company

to manage a team of programmers in India. It didn’t go smoothly: The Indian workers were

skilled, but the time difference and the distance made it hard to collaborate. He eventually

told the company that it would be better to bring the work home.

“I can share my screen with them, but I can’t, in real time, sit with them while they’re

making the mistakes and show them where they’re making the mistakes,” he said.

Mr. Kincaid’s current employer, Nexient, develops software for companies on a contract

basis — work that is a prime candidate for outsourcing. But all of Nexient’s employees are in

the United States, which the company uses as a selling point with its clients.

Mark Orttung, Nexient’s chief executive, said that offshoring worked fine for certain types of

work, such as short-term projects, but less well on projects where requirements change over

time and collaboration is more important. American workers can also have an edge on

projects that require them to understand the specifics of the business: how the American

health care system works, for example, or what customers expect from a particular brand.

“When we work with a large retailer, most of our employees probably shop at that retailer,”

Mr. Orttung said.

Nexient is based in the San Francisco Bay Area, but most of its employees are in Columbus

or in Ann Arbor, Mich. Both are college towns, with plenty of young graduates with technical

skills. They are in or near metropolitan areas with big companies that are sources of more

experienced workers. And they are much cheaper places to live than Silicon Valley.

A growing number of companies are shifting operations to cities like Columbus, said Susan

Lund, who has studied the future of work for the McKinsey Global Institute, the consulting

firm’s think tank. No American location can compete directly with India on labor costs, she

said, but shifting jobs elsewhere in the country can narrow the gap.

“The companies that started the offshoring trend were largely based in Manhattan or the West

Coast, in the very high-cost places, and they realized that, hey, there are a lot of other places

in the U.S.,” she said.

The two occupations may seem similar. But the different employment trend may reflect both

cultural and logistical differences. Telemarketers are essentially selling products and often

working from a script. Customer service and other call-center work like tech support often

require a more nuanced understanding of the customer experience.

Deb Thorpe, senior vice president for operations for Kelly Services, a staffing company, said

that rather than move customer service jobs abroad, many companies were trying to find cost

efficiencies by putting offices in less expensive parts of the country or letting workers take

calls from home.

“The call center business in the U.S. is still pretty healthy,” Ms. Thorpe said.

Mr. Kincaid, now 59 and living in Columbus, Ohio, has seen all those patterns up close.

Shortly after his own near miss with offshoring, he was hired by another American company

to manage a team of programmers in India. It didn’t go smoothly: The Indian workers were

skilled, but the time difference and the distance made it hard to collaborate. He eventually

told the company that it would be better to bring the work home.

“I can share my screen with them, but I can’t, in real time, sit with them while they’re

making the mistakes and show them where they’re making the mistakes,” he said.

Mr. Kincaid’s current employer, Nexient, develops software for companies on a contract

basis — work that is a prime candidate for outsourcing. But all of Nexient’s employees are in

the United States, which the company uses as a selling point with its clients.

Mark Orttung, Nexient’s chief executive, said that offshoring worked fine for certain types of

work, such as short-term projects, but less well on projects where requirements change over

time and collaboration is more important. American workers can also have an edge on

projects that require them to understand the specifics of the business: how the American

health care system works, for example, or what customers expect from a particular brand.

“When we work with a large retailer, most of our employees probably shop at that retailer,”

Mr. Orttung said.

Nexient is based in the San Francisco Bay Area, but most of its employees are in Columbus

or in Ann Arbor, Mich. Both are college towns, with plenty of young graduates with technical

skills. They are in or near metropolitan areas with big companies that are sources of more

experienced workers. And they are much cheaper places to live than Silicon Valley.

A growing number of companies are shifting operations to cities like Columbus, said Susan

Lund, who has studied the future of work for the McKinsey Global Institute, the consulting

firm’s think tank. No American location can compete directly with India on labor costs, she

said, but shifting jobs elsewhere in the country can narrow the gap.

“The companies that started the offshoring trend were largely based in Manhattan or the West

Coast, in the very high-cost places, and they realized that, hey, there are a lot of other places

in the U.S.,” she said.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8Outsourcing: White-collar Job Apocalypse

The evolving thinking on offshoring could carry lessons for another much-discussed threat:

automation. In recent years, economists and technology experts have warned that rapid

improvements in artificial intelligence, robotics and related fields could endanger a huge

share of jobs — often using terms that echo the offshoring debates.

Ms. Lund said she saw parallels between offshoring and automation: Both trends threaten one

set of jobs but should make the overall American economy more productive, creating new job

opportunities, albeit ones requiring different skills. And she said the pace of change should

allow workers, companies and governments to adapt.

“The lesson is, change is evolutionary, not revolutionary,” Ms. Lund said. “There’s not mass

movement of jobs anywhere. And because it’s a slow change, it gives people and companies

a chance to adjust so we never saw the mass exodus of jobs to India.”

Ben Casselman writes about economics, with a particular focus on stories involving data. He

previously reported for FiveThirtyEight and The Wall Street Journal.

The evolving thinking on offshoring could carry lessons for another much-discussed threat:

automation. In recent years, economists and technology experts have warned that rapid

improvements in artificial intelligence, robotics and related fields could endanger a huge

share of jobs — often using terms that echo the offshoring debates.

Ms. Lund said she saw parallels between offshoring and automation: Both trends threaten one

set of jobs but should make the overall American economy more productive, creating new job

opportunities, albeit ones requiring different skills. And she said the pace of change should

allow workers, companies and governments to adapt.

“The lesson is, change is evolutionary, not revolutionary,” Ms. Lund said. “There’s not mass

movement of jobs anywhere. And because it’s a slow change, it gives people and companies

a chance to adjust so we never saw the mass exodus of jobs to India.”

Ben Casselman writes about economics, with a particular focus on stories involving data. He

previously reported for FiveThirtyEight and The Wall Street Journal.

1 out of 8

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.