The Gravity Model and Trade Efficiency: A Stochastic Frontier Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|32

|8745

|393

Report

AI Summary

This paper investigates trade efficiency among Eastern and Western European countries using a stochastic frontier analysis of the gravity model. It examines bilateral exports from 17 Western European countries to 10 new member states between 1994 and 2007, a period marked by significant economic transformation. The study constructs a trade frontier representing the maximum possible level of bilateral trade and generates efficiency scores to assess the degree of East-West trade integration. The findings suggest a high degree of trade integration, with new member states achieving approximately two-thirds of their frontier estimates, indicating low trade resistances. The research highlights exceptions to this pattern, identifying countries with the greatest potential for trade expansion. The analysis contributes to the literature by evaluating trade performance against a maximum potential level defined by a stochastic frontier, offering insights into trade dynamics and potential areas for growth.

DISCUSSION PAPERS

IN

ECONOMICS

No. 2013/4 ISSN 1478-9396

THE GRAVITY MODEL AND TRADE

EFFICIENCY: A STOCHASTIC FRONTIER

ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL TRADE

GEETHA RAVISHANKAR

IN

ECONOMICS

No. 2013/4 ISSN 1478-9396

THE GRAVITY MODEL AND TRADE

EFFICIENCY: A STOCHASTIC FRONTIER

ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL TRADE

GEETHA RAVISHANKAR

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

DISCUSSION PAPERS IN ECONOMICS

The economic research undertaken at Nottingham Trent University

covers various fields of economics. But, a large part of it was grouped

into two categories, Applied Economics and Policy and Political

Economy.

This paper is part of the new series, Discussion Papers in

Economics.

Earlier papers in all series can be found at:

http://www.ntu.ac.uk/research/research_at_ntu/academic_schools/nbs

/working_papers.html

Enquiries concerning this or any of our other Discussion Papers should

be addressed to the Editors:

Dr. Marie Stack, Email: marie.stack@ntu.ac.uk

Dr. Dan Wheatley, Email: daniel.wheatley2@ntu.ac.uk

Division of Economics

Nottingham Trent University

Burton Street, Nottingham, NG1 4BU

UNITED KINGDOM.

The economic research undertaken at Nottingham Trent University

covers various fields of economics. But, a large part of it was grouped

into two categories, Applied Economics and Policy and Political

Economy.

This paper is part of the new series, Discussion Papers in

Economics.

Earlier papers in all series can be found at:

http://www.ntu.ac.uk/research/research_at_ntu/academic_schools/nbs

/working_papers.html

Enquiries concerning this or any of our other Discussion Papers should

be addressed to the Editors:

Dr. Marie Stack, Email: marie.stack@ntu.ac.uk

Dr. Dan Wheatley, Email: daniel.wheatley2@ntu.ac.uk

Division of Economics

Nottingham Trent University

Burton Street, Nottingham, NG1 4BU

UNITED KINGDOM.

The Gravity Model and Trade Efficiency:

A Stochastic Frontier Analysis of Potential Trade

ABSTRACT

The opening up process of the eastern European countries is characterised by an

increasing degree of trade integration with their Western neigbouring countries.

Typically, the degree of East West trade integration is assessed by comparing actual trade

volumes with potential trade volumes projected from the gravity model parameters

estimated for a group of countries that best represent normal trade relations. This

approach, however, does not compare trade levels against a maximum level of trade

feasible for the group of eastern European countries. This paper by using a stochastic

frontier specification of the gravity model is able to identify the efficiency of trade

integration relative to maximum potential levels. The findings, based on a panel data set

of bilateral exports from 17 Western European countries to the 10 new member states

over the 1994 2007 period, indicate a high degree of East West trade integration close to

two thirds of frontier estimates, suggesting a low degree of trade resistances.

JEL Classification: C33, F14, F15

Keywords: Gravity model, Potential trade, Efficiency scores

A Stochastic Frontier Analysis of Potential Trade

ABSTRACT

The opening up process of the eastern European countries is characterised by an

increasing degree of trade integration with their Western neigbouring countries.

Typically, the degree of East West trade integration is assessed by comparing actual trade

volumes with potential trade volumes projected from the gravity model parameters

estimated for a group of countries that best represent normal trade relations. This

approach, however, does not compare trade levels against a maximum level of trade

feasible for the group of eastern European countries. This paper by using a stochastic

frontier specification of the gravity model is able to identify the efficiency of trade

integration relative to maximum potential levels. The findings, based on a panel data set

of bilateral exports from 17 Western European countries to the 10 new member states

over the 1994 2007 period, indicate a high degree of East West trade integration close to

two thirds of frontier estimates, suggesting a low degree of trade resistances.

JEL Classification: C33, F14, F15

Keywords: Gravity model, Potential trade, Efficiency scores

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1. INTRODUCTION

Not unlike the drive to increase trade between the established European Union (EU)

member countries as part of a customs union, the opening up process of the eastern

European countries began with trade integration. Strong bilateral trade links were formed

in advance of formal EU entry. After the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

(CMEA) system1 was dissolved in the early 1990s, a new era of trade expansion was

ushered in, culminating in the Western European countries becoming the main trading

partners for the excommunist countries.

Figure 1 plots each new EU member country’s share of world trade (exports plus

imports) with the Western European countries. By 1994, Western Europe had already

become important trading partners for the group of ten, implying an almost immediate

release of economic ties from the former Soviet Union. Trailing behind its counterparts,

Lithuania was initially the slowest to open up its trade links, but increased its trade shares

by 1.5 times within a decade. Slovakia experienced an even more dramatic reorientation

of trade westwards, rising by two thirds to its peak levels in 2003. Conducting about half

of its trade with the Western countries in 1993, the trade shares for Bulgaria and Romania

depict an almost parallel trend, but with the latter maintaining a ten per cent lead over the

former. Much like Bulgaria’s path, the trade shares for Estonia and Latvia have ended up

like they started albeit with some variation in between. The trade shares for the top four

ranking countries, namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovenia remain

Not unlike the drive to increase trade between the established European Union (EU)

member countries as part of a customs union, the opening up process of the eastern

European countries began with trade integration. Strong bilateral trade links were formed

in advance of formal EU entry. After the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

(CMEA) system1 was dissolved in the early 1990s, a new era of trade expansion was

ushered in, culminating in the Western European countries becoming the main trading

partners for the excommunist countries.

Figure 1 plots each new EU member country’s share of world trade (exports plus

imports) with the Western European countries. By 1994, Western Europe had already

become important trading partners for the group of ten, implying an almost immediate

release of economic ties from the former Soviet Union. Trailing behind its counterparts,

Lithuania was initially the slowest to open up its trade links, but increased its trade shares

by 1.5 times within a decade. Slovakia experienced an even more dramatic reorientation

of trade westwards, rising by two thirds to its peak levels in 2003. Conducting about half

of its trade with the Western countries in 1993, the trade shares for Bulgaria and Romania

depict an almost parallel trend, but with the latter maintaining a ten per cent lead over the

former. Much like Bulgaria’s path, the trade shares for Estonia and Latvia have ended up

like they started albeit with some variation in between. The trade shares for the top four

ranking countries, namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovenia remain

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A two stage gravity approach to projecting East West trade volumes is the usual

route to assessing bilateral trade performance. In the first stage, the gravity model of trade

is estimated for a group of countries that best represent normal trade relations. In its basic

form, the standard gravity equation explains bilateral trade as a function of the economic

size of two countries and the distance between them (Tinbergen 1962; Pöyhönen 1963).

The augmented version additionally includes income per head for both countries and

other trade impeding or trade stimulating factors (Bergstrand 1989).

In the second stage, the gravity model parameters that fit a model of a normal

country’s geographic trade patterns are used to project the expected trade flows in an East

West direction. The trade flows predicted by the model can then be compared with actual

trade flows to assess the likelihood for future expansion or depletion of trade links

between a pair of countries. Whereas a value in excess of unity suggests remaining

potential for trade growth, a value of less than unity suggests trade potential is already

exhausted. In this way, the potential to actual trade ratios are informative as to the degree

of East West trade integration under normal conditions.

The two stage approach to trade projections pervades the empirical literature (see,

for example, Baldwin 1994; Gros and Gonciarz 1996; Stack and Pentecost 2010). In

assuming full economic liberalisation, these studies define East West potential trade in

terms of the sample average, usually the Western European countries. In other words, the

mean effects of trade determinants are estimated, implying potential trade is assessed

route to assessing bilateral trade performance. In the first stage, the gravity model of trade

is estimated for a group of countries that best represent normal trade relations. In its basic

form, the standard gravity equation explains bilateral trade as a function of the economic

size of two countries and the distance between them (Tinbergen 1962; Pöyhönen 1963).

The augmented version additionally includes income per head for both countries and

other trade impeding or trade stimulating factors (Bergstrand 1989).

In the second stage, the gravity model parameters that fit a model of a normal

country’s geographic trade patterns are used to project the expected trade flows in an East

West direction. The trade flows predicted by the model can then be compared with actual

trade flows to assess the likelihood for future expansion or depletion of trade links

between a pair of countries. Whereas a value in excess of unity suggests remaining

potential for trade growth, a value of less than unity suggests trade potential is already

exhausted. In this way, the potential to actual trade ratios are informative as to the degree

of East West trade integration under normal conditions.

The two stage approach to trade projections pervades the empirical literature (see,

for example, Baldwin 1994; Gros and Gonciarz 1996; Stack and Pentecost 2010). In

assuming full economic liberalisation, these studies define East West potential trade in

terms of the sample average, usually the Western European countries. In other words, the

mean effects of trade determinants are estimated, implying potential trade is assessed

trade performance against a maximum possible level of potential trade defined by a

stochastic frontier.

This paper assesses potential trade against a maximum level of trade feasible for

the group of 10 new member states (NMS) using a stochastic frontier approach to

estimating the gravity equation. Specifically, a trade frontier representing the maximum

possible level of bilateral trade is constructed for a panel of exports from 17 Western

European countries to the new EU member countries over the 1994 2007 period, covering

the transformation phase from communism to EU accession. The efficiency scores are

then generated from this frontier specification of the gravity model. If two countries

achieve an efficient level of trade, they will operate on the trade frontier and will realise

their maximum trade potential otherwise deviations of observed trade levels from the

trade frontier indicate inefficient levels of trade, implying scope for further trade

expansion. The frontier specification of the gravity model is similar in approach to that

used by Drysdale et al. (2000) who consider China’s trade efficiency, Kalirajan and

Singh (2008) who conduct a comparative analysis of export potential for China and India

and Armstrong et al. (2008) who compare trade performance in East Asia and South

Asia.

The efficiency scores suggest a high degree of East West trade integration, with

each new member state achieving on average two thirds of frontier estimates over the

1994 2007 period. The high efficiency scores indicate a low degree of trade resistances.

stochastic frontier.

This paper assesses potential trade against a maximum level of trade feasible for

the group of 10 new member states (NMS) using a stochastic frontier approach to

estimating the gravity equation. Specifically, a trade frontier representing the maximum

possible level of bilateral trade is constructed for a panel of exports from 17 Western

European countries to the new EU member countries over the 1994 2007 period, covering

the transformation phase from communism to EU accession. The efficiency scores are

then generated from this frontier specification of the gravity model. If two countries

achieve an efficient level of trade, they will operate on the trade frontier and will realise

their maximum trade potential otherwise deviations of observed trade levels from the

trade frontier indicate inefficient levels of trade, implying scope for further trade

expansion. The frontier specification of the gravity model is similar in approach to that

used by Drysdale et al. (2000) who consider China’s trade efficiency, Kalirajan and

Singh (2008) who conduct a comparative analysis of export potential for China and India

and Armstrong et al. (2008) who compare trade performance in East Asia and South

Asia.

The efficiency scores suggest a high degree of East West trade integration, with

each new member state achieving on average two thirds of frontier estimates over the

1994 2007 period. The high efficiency scores indicate a low degree of trade resistances.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The layout of this paper is as follows. Section 2 sets out the gravity model

specification, distinguishing between the conventional gravity equation and the stochastic

frontier gravity equation. The data sources and the expected coefficient signs are also

given in this section. The results in Section 3 are split between the gravity model

coefficient estimates and the efficiency scores of potential trade. Section 4 concludes.

2. MODEL SPECIFICATION AND DATA

2.1 The Gravity Equation

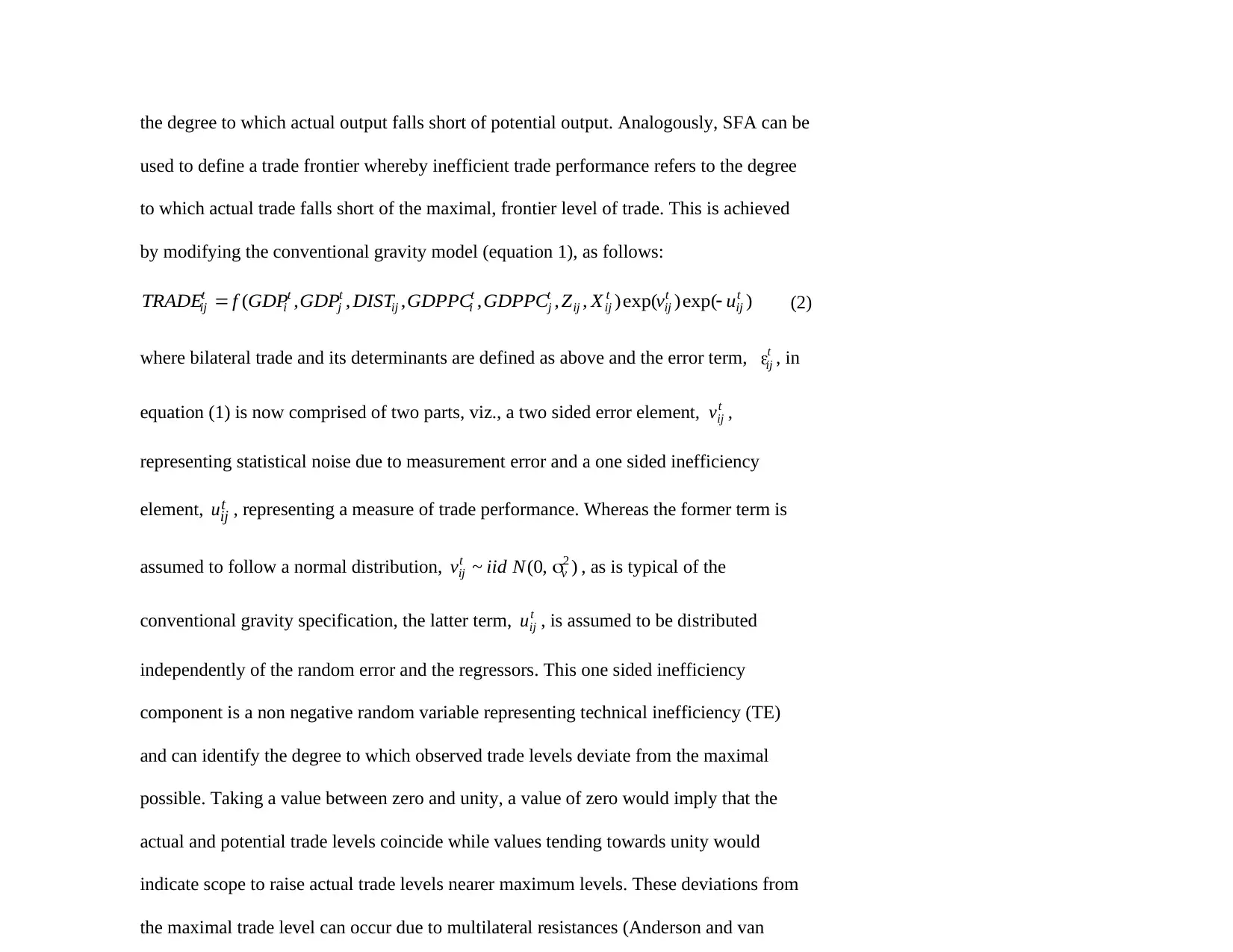

The gravity model specification for calculating trade volumes (Baldwin 1994; Gros and

Gonciarz 1996; Nilsson 2000) is typically of the following form:

t

j

t

iij

t

j

t

i

t

ij GDPPCGDPPCDISTGDPGDPTRADE 543210

t

ij

K

k

t

ijk

G

g

ijg XZ 11

(1)

where t

ijTRADE are the bilateral trade flows between countries i and j over a given

time period t ; t

iGDP and t

jGDP denote the economic size of both countries; ijDIST is

the geographic distance between their economic centres; and t

iGDPPC and t

jGDPPC are

the respective countries’ per capita income levels capturing factor endowments in the

exporting country and consumption patterns in the importing country. Equation (1) also

includes a vector of time invariant explanatory variables, ijZ ; a vector of time varying

specification, distinguishing between the conventional gravity equation and the stochastic

frontier gravity equation. The data sources and the expected coefficient signs are also

given in this section. The results in Section 3 are split between the gravity model

coefficient estimates and the efficiency scores of potential trade. Section 4 concludes.

2. MODEL SPECIFICATION AND DATA

2.1 The Gravity Equation

The gravity model specification for calculating trade volumes (Baldwin 1994; Gros and

Gonciarz 1996; Nilsson 2000) is typically of the following form:

t

j

t

iij

t

j

t

i

t

ij GDPPCGDPPCDISTGDPGDPTRADE 543210

t

ij

K

k

t

ijk

G

g

ijg XZ 11

(1)

where t

ijTRADE are the bilateral trade flows between countries i and j over a given

time period t ; t

iGDP and t

jGDP denote the economic size of both countries; ijDIST is

the geographic distance between their economic centres; and t

iGDPPC and t

jGDPPC are

the respective countries’ per capita income levels capturing factor endowments in the

exporting country and consumption patterns in the importing country. Equation (1) also

includes a vector of time invariant explanatory variables, ijZ ; a vector of time varying

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

trade is defined relative to the sample average rather than in terms of a maximum level

feasible for a given pair of trading partners. Measuring trade potential against mean

predicted values can be problematic because the predictive ability of the gravity model

declines as the year of the inserted values increasingly deviates from the sample average. 2

Under the stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) approach, the gravity equation of

trade determinants identifies the trade frontier. The resulting frontier levels of trade, i.e.

the maximum possible level of trade for a given bilateral trading pair, is impacted by a

random error term which can be positive or negative thereby allowing the stochastic

frontier trade level to vary about the deterministic part of the gravity equation. Observed

trade levels can then be compared against this frontier level of trade for each bilateral

trading pair to assess the scope for trade expansion. The next section provides a detailed

exposition of this approach.

2.2 The Gravity Equation estimated using Stochastic Frontier Analysis

Developed independently by Aigner et al. (1977) and Meeusen and van den Broeck

(1977), stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) has been used extensively in the assessment of

firm performance. In its traditional application, SFA specifies a production frontier

representing the maximum output that can be produced from a given level of inputs.

Fully efficient firms operate on the frontier such that observed and frontier levels of

output coincide, while (technically) inefficient firms operate at a point within the frontier,

signifying a shortfall between the observed and the maximum possible levels of output.

feasible for a given pair of trading partners. Measuring trade potential against mean

predicted values can be problematic because the predictive ability of the gravity model

declines as the year of the inserted values increasingly deviates from the sample average. 2

Under the stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) approach, the gravity equation of

trade determinants identifies the trade frontier. The resulting frontier levels of trade, i.e.

the maximum possible level of trade for a given bilateral trading pair, is impacted by a

random error term which can be positive or negative thereby allowing the stochastic

frontier trade level to vary about the deterministic part of the gravity equation. Observed

trade levels can then be compared against this frontier level of trade for each bilateral

trading pair to assess the scope for trade expansion. The next section provides a detailed

exposition of this approach.

2.2 The Gravity Equation estimated using Stochastic Frontier Analysis

Developed independently by Aigner et al. (1977) and Meeusen and van den Broeck

(1977), stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) has been used extensively in the assessment of

firm performance. In its traditional application, SFA specifies a production frontier

representing the maximum output that can be produced from a given level of inputs.

Fully efficient firms operate on the frontier such that observed and frontier levels of

output coincide, while (technically) inefficient firms operate at a point within the frontier,

signifying a shortfall between the observed and the maximum possible levels of output.

the degree to which actual output falls short of potential output. Analogously, SFA can be

used to define a trade frontier whereby inefficient trade performance refers to the degree

to which actual trade falls short of the maximal, frontier level of trade. This is achieved

by modifying the conventional gravity model (equation 1), as follows:

)exp()exp(),,,,,,( t

ij

t

ij

t

ijij

t

j

t

iij

t

j

t

i

t

ij uvXZGDPPCGDPPCDISTGDPGDPfTRADE (2)

where bilateral trade and its determinants are defined as above and the error term, t

ij , in

equation (1) is now comprised of two parts, viz., a two sided error element, t

ijv ,

representing statistical noise due to measurement error and a one sided inefficiency

element, t

iju , representing a measure of trade performance. Whereas the former term is

assumed to follow a normal distribution, ),0(~ 2

v

t

ij Niidv , as is typical of the

conventional gravity specification, the latter term, t

iju , is assumed to be distributed

independently of the random error and the regressors. This one sided inefficiency

component is a non negative random variable representing technical inefficiency (TE)

and can identify the degree to which observed trade levels deviate from the maximal

possible. Taking a value between zero and unity, a value of zero would imply that the

actual and potential trade levels coincide while values tending towards unity would

indicate scope to raise actual trade levels nearer maximum levels. These deviations from

the maximal trade level can occur due to multilateral resistances (Anderson and van

used to define a trade frontier whereby inefficient trade performance refers to the degree

to which actual trade falls short of the maximal, frontier level of trade. This is achieved

by modifying the conventional gravity model (equation 1), as follows:

)exp()exp(),,,,,,( t

ij

t

ij

t

ijij

t

j

t

iij

t

j

t

i

t

ij uvXZGDPPCGDPPCDISTGDPGDPfTRADE (2)

where bilateral trade and its determinants are defined as above and the error term, t

ij , in

equation (1) is now comprised of two parts, viz., a two sided error element, t

ijv ,

representing statistical noise due to measurement error and a one sided inefficiency

element, t

iju , representing a measure of trade performance. Whereas the former term is

assumed to follow a normal distribution, ),0(~ 2

v

t

ij Niidv , as is typical of the

conventional gravity specification, the latter term, t

iju , is assumed to be distributed

independently of the random error and the regressors. This one sided inefficiency

component is a non negative random variable representing technical inefficiency (TE)

and can identify the degree to which observed trade levels deviate from the maximal

possible. Taking a value between zero and unity, a value of zero would imply that the

actual and potential trade levels coincide while values tending towards unity would

indicate scope to raise actual trade levels nearer maximum levels. These deviations from

the maximal trade level can occur due to multilateral resistances (Anderson and van

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Following Aigner et al. (1977), equation (2) is operationalised as a pooled frontier wherein the

parameter values are obtained by maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). Along with the gravity model

parameters, estimates for the variance of the composed error term, 222

uv , and the ratio of the

standard deviation of the inefficiency component to the standard deviation of the random error component,

vu , are also generated. The latter assesses the degree of inefficiency relative to the random error

and when statistically significant, justifies the use of the SFA approach. A further test for the presence of

technical efficiency in the model is undertaken via a one sided likelihood ratio (LR) test of the null

hypothesis, 0: 2

0 uH , against the alternative, 02

0 u:H . Failure to reject the null hypothesis

leads to the SFA model to reduce to an OLS model.

Following parameter estimation, the point estimates of inefficiency can then be obtained as the

mean of the conditional distribution of u given (Jondrow et al. 1982):

2

2

)~(

exp

)~(2

1

)(

),(

)(

u

f

uf

uf

vv

)(

)(

)(

v

t

ij

v

t

ij

v

t

ij

t

ij

t

ij z

z

zuE

(3)

where uv

t

ij

t

ijz 2

and (.) and (.) are the standard normal density and cumulative

distribution functions, respectively. The technical efficiency (TE) estimates for each country pair are then

determined as )exp( t

ij

t

ij uTE .

The full model specification of trade determinants between the Western European countries and

the new EU member states is specified as follows:

tttt COLLOCKDGDPPCDISTGDPGDPEXP

parameter values are obtained by maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). Along with the gravity model

parameters, estimates for the variance of the composed error term, 222

uv , and the ratio of the

standard deviation of the inefficiency component to the standard deviation of the random error component,

vu , are also generated. The latter assesses the degree of inefficiency relative to the random error

and when statistically significant, justifies the use of the SFA approach. A further test for the presence of

technical efficiency in the model is undertaken via a one sided likelihood ratio (LR) test of the null

hypothesis, 0: 2

0 uH , against the alternative, 02

0 u:H . Failure to reject the null hypothesis

leads to the SFA model to reduce to an OLS model.

Following parameter estimation, the point estimates of inefficiency can then be obtained as the

mean of the conditional distribution of u given (Jondrow et al. 1982):

2

2

)~(

exp

)~(2

1

)(

),(

)(

u

f

uf

uf

vv

)(

)(

)(

v

t

ij

v

t

ij

v

t

ij

t

ij

t

ij z

z

zuE

(3)

where uv

t

ij

t

ijz 2

and (.) and (.) are the standard normal density and cumulative

distribution functions, respectively. The technical efficiency (TE) estimates for each country pair are then

determined as )exp( t

ij

t

ij uTE .

The full model specification of trade determinants between the Western European countries and

the new EU member states is specified as follows:

tttt COLLOCKDGDPPCDISTGDPGDPEXP

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

relative terms as the absolute difference in the logged values of GDP per capita income levels,

tj

t

i

t

ij GDPPClnGDPPClnDGDPPC , as a proxy for differences in consumption patterns. The

vector of time invariant explanatory variables, ijZ , comprises a binary coded dummy for landlocked

countries, jLOCK , and a dummy denoting common colonial ties, ijCOL , as an indicator for institutional

proximity. The vector of time varying explanatory variables, t

ijX , refers to the real exchange rate for both

countries, t

iRER and t

jRER , to capture currency price movements. Two additional dummies account for

the EU accession of eight new member states in 2004, t

ijEU 04 , and the later accession of Bulgaria and

Romania in 2007, t

ijEU 07 . All non dummy variables in equation (4) are estimated in logarithmic form.

In its basic form, the standard gravity equation posits that bilateral trade increases with national

income and declines with the distance between them. 4 Larger countries tend to trade more, consistent with

the conduct of much of intraindustry trade between the advanced countries (Helpman and Krugman 1985),

hence the GDP coefficients for both countries should be positively signed. Countries located within close

proximity incur lower transport costs which boosts trade, implying the distance coefficient, ijDIST , should

be negatively signed.

In the augmented version of the gravity model, the separate roles for per capita

income identified by Bergstrand (1989) are merged by Gruber and Vernon (1970) into

the per capita income differential as an indirect way of testing the Linder (1961)

hypothesis. Although Linder presented no formal model, the demand based theory

suggests that if an importing country’s aggregated preferences for goods are similar to an

tj

t

i

t

ij GDPPClnGDPPClnDGDPPC , as a proxy for differences in consumption patterns. The

vector of time invariant explanatory variables, ijZ , comprises a binary coded dummy for landlocked

countries, jLOCK , and a dummy denoting common colonial ties, ijCOL , as an indicator for institutional

proximity. The vector of time varying explanatory variables, t

ijX , refers to the real exchange rate for both

countries, t

iRER and t

jRER , to capture currency price movements. Two additional dummies account for

the EU accession of eight new member states in 2004, t

ijEU 04 , and the later accession of Bulgaria and

Romania in 2007, t

ijEU 07 . All non dummy variables in equation (4) are estimated in logarithmic form.

In its basic form, the standard gravity equation posits that bilateral trade increases with national

income and declines with the distance between them. 4 Larger countries tend to trade more, consistent with

the conduct of much of intraindustry trade between the advanced countries (Helpman and Krugman 1985),

hence the GDP coefficients for both countries should be positively signed. Countries located within close

proximity incur lower transport costs which boosts trade, implying the distance coefficient, ijDIST , should

be negatively signed.

In the augmented version of the gravity model, the separate roles for per capita

income identified by Bergstrand (1989) are merged by Gruber and Vernon (1970) into

the per capita income differential as an indirect way of testing the Linder (1961)

hypothesis. Although Linder presented no formal model, the demand based theory

suggests that if an importing country’s aggregated preferences for goods are similar to an

negative coefficient for the per capita income differential, t

ijDGDPPC , suggesting trade

is positively related to consumers with similar per capita incomes and therefore having

similar consumption patterns, indicates support for the Linder hypothesis. On the other

hand, a positive coefficient will ensue if trade is driven more by differing per capita

incomes consistent with the Heckscher Ohlin model (1919, 1933) of relative factor

abundance.

The dummies included in equation (4) are equal to unity if the new member countries are

landlocked, jLOCK , or if the EU countries share a history of colonial ties, ijCOL . Opposing trade

effects are expected for the respective dummy coefficients. As the overland costs of transporting goods

tends to be higher than shipping costs, landlocked countries located in the heart of Europe tend to be

disadvantaged in trade terms because of their geographical position. In contrast, past governance of another

country can boost present economic links because a coloniser may well have contributed to the state of the

institutions of the colonised.

Motivated by the gravity model derived by Bergstrand (1985), which explicitly includes an

exchange rate index to account for location dependent trade costs, the real exchange rate for both countries,

t

iRER and tjRER , is included to capture the trade effect of currency price movements. Micco et al.

(2003) include the RER for both countries against the US dollar to control for valuation effects, arguing

that a depreciation of the US dollar exchange rate can lower the US dollar value of intra eurozone trade.

The real exchange rate can also be interpreted as a measure of national competitiveness. An increase in the

US real exchange rate (implying a depreciation of the US dollar) improves price competitiveness with

consequential beneficial effects on US exports in foreign markets, but with detrimental effects on US

ijDGDPPC , suggesting trade

is positively related to consumers with similar per capita incomes and therefore having

similar consumption patterns, indicates support for the Linder hypothesis. On the other

hand, a positive coefficient will ensue if trade is driven more by differing per capita

incomes consistent with the Heckscher Ohlin model (1919, 1933) of relative factor

abundance.

The dummies included in equation (4) are equal to unity if the new member countries are

landlocked, jLOCK , or if the EU countries share a history of colonial ties, ijCOL . Opposing trade

effects are expected for the respective dummy coefficients. As the overland costs of transporting goods

tends to be higher than shipping costs, landlocked countries located in the heart of Europe tend to be

disadvantaged in trade terms because of their geographical position. In contrast, past governance of another

country can boost present economic links because a coloniser may well have contributed to the state of the

institutions of the colonised.

Motivated by the gravity model derived by Bergstrand (1985), which explicitly includes an

exchange rate index to account for location dependent trade costs, the real exchange rate for both countries,

t

iRER and tjRER , is included to capture the trade effect of currency price movements. Micco et al.

(2003) include the RER for both countries against the US dollar to control for valuation effects, arguing

that a depreciation of the US dollar exchange rate can lower the US dollar value of intra eurozone trade.

The real exchange rate can also be interpreted as a measure of national competitiveness. An increase in the

US real exchange rate (implying a depreciation of the US dollar) improves price competitiveness with

consequential beneficial effects on US exports in foreign markets, but with detrimental effects on US

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 32

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.