An In-depth Analysis of Health Care Expenditure Growth Drivers

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/16

|14

|3936

|348

Essay

AI Summary

This essay delves into the multifaceted drivers of health care expenditure growth, examining the global landscape of healthcare spending. It explores the significant variations in health expenditure across high-income and resource-poor nations, highlighting the impact of economic development and fiscal policies. The essay analyzes key factors influencing healthcare costs, including income levels, technological advancements, and demographic shifts. It discusses various modeling approaches used to understand healthcare costs, emphasizing the role of per capita GDP and its elasticity. The study also considers the influence of population age structure, technological progress, and health system characteristics on expenditure patterns. Furthermore, it explores the relationship between government funding, social insurance schemes, and external resources, such as Official Development Aid, and their effects on healthcare spending. The essay underscores the need for efficient resource allocation and innovative funding sources to meet the growing demands of healthcare in developed and developing societies. The analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the complex interplay of factors shaping healthcare expenditure, offering valuable insights into global healthcare trends.

Running head: HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author’s Note:

HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author’s Note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

Introduction:

Globally, the quantity of nations spending on health varies greatly. Health expenditure in high-

income countries per capita is over USD 3000 on average, compared with only USD 30 per

capita in resource poor nations. In 2008, per capita health expenditure in 64 nations fell below

USD 100 (Ke, Saksena, & Holly, 2011). The health costs of economic development are also

highly variable. Some nations spend more than 12 per cent of GDP on health and some spend

less than 3 per cent on health. Economists agree that most Western European countries are

currently operating health care systems that cannot be funded at all in future. Moreover, it may

not be far from the future. In general, Europe's fiscal balance and debt levels will be consolidated

in the next ten years. Europe is nearing frightening levels of public debt even if crisis-related

measures and developments are diminished. The European Commission has recently estimated

that by the end of this century, public debt in the EU may amount to up to 120 percent of GDP

(Ke et al., 2011). Only this would have depressing impacts on all kinds of government spending.

As spending rises even more rapidly when baby boom generation reaches medical age quickly,

any account of the future funding of healthcare is read carefully. There is a pressing need to find

methods of more effectively using resources and fresh sources of funding to meet growing

requirements for medical care in Europe and other matured societies with firm models for

finances (e.g. the United States). A comprehensive literature is available in OECD countries

about health expenditure and their development (Baltagi & Moscone, 2010). However, there is

comparatively little proof from developing nations, and the article aims to help fill this gap

through the exploration of information from 143 developing and developing nations. Healthcare

costs have been significantly increased for a long time. In the last two decades, the trend in

spending has continuously increased. For instance, over the last two years, each resident's

Introduction:

Globally, the quantity of nations spending on health varies greatly. Health expenditure in high-

income countries per capita is over USD 3000 on average, compared with only USD 30 per

capita in resource poor nations. In 2008, per capita health expenditure in 64 nations fell below

USD 100 (Ke, Saksena, & Holly, 2011). The health costs of economic development are also

highly variable. Some nations spend more than 12 per cent of GDP on health and some spend

less than 3 per cent on health. Economists agree that most Western European countries are

currently operating health care systems that cannot be funded at all in future. Moreover, it may

not be far from the future. In general, Europe's fiscal balance and debt levels will be consolidated

in the next ten years. Europe is nearing frightening levels of public debt even if crisis-related

measures and developments are diminished. The European Commission has recently estimated

that by the end of this century, public debt in the EU may amount to up to 120 percent of GDP

(Ke et al., 2011). Only this would have depressing impacts on all kinds of government spending.

As spending rises even more rapidly when baby boom generation reaches medical age quickly,

any account of the future funding of healthcare is read carefully. There is a pressing need to find

methods of more effectively using resources and fresh sources of funding to meet growing

requirements for medical care in Europe and other matured societies with firm models for

finances (e.g. the United States). A comprehensive literature is available in OECD countries

about health expenditure and their development (Baltagi & Moscone, 2010). However, there is

comparatively little proof from developing nations, and the article aims to help fill this gap

through the exploration of information from 143 developing and developing nations. Healthcare

costs have been significantly increased for a long time. In the last two decades, the trend in

spending has continuously increased. For instance, over the last two years, each resident's

2HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

healthcare spending in the US has been around $7,600 (Dieleman et al., 2016). It accounted for

approximately 16% of the nation's GDP. In reality, this figure is still the highest in the developed

countries. For instance, new medical technologies, treatments and medications can generate extra

expenditure on healthcare, particularly if they are not substituting or reducing current expenses

for one reason or another (Erixon & Van der Marel, 2011). However, it is not true that these new

or extra expenses explain the greater portion of general health care expenses. For example,

public services expenditure has in the last decades accounted for a steady comparative share of

OECD countries’ overall health care expenses. Indeed, pharmaceutical expenditure has

decreased relatively from 1970, although complete public health expenditure has risen quickly

over the previous 15 years (Erixon & Van der Marel, 2011). True, medical innovations such as

CT scanners have led to increasing healthcare expenses, while the general trend in the rates of

investment and healthcare development does not match the rates shown for general healthcare

expenditure development. In addition, when the expenses of particular components in healthcare

manufacturing are compared across nations, there is a considerable distinction in the degree of

capital contributions to healthcare manufacturing among nations of comparable stage of growth.

Moreover, for an industry of "Baumol disease characteristics," such as healthcare, incomes

should not be sufficient to follow a broad GDP growth trend; health tax revenues should instead

rise beyond the overall GDP trend to cover rising disease expenses (Hartwig, 2011). There are

clear trends for the European nations we studied in lagging productivity rates and greater actual

costs for healthcare.

In addition to a prediction on the scheme in terms of future development opportunities, this essay

will discuss present health care expenses in the world environment.

Discussion:

healthcare spending in the US has been around $7,600 (Dieleman et al., 2016). It accounted for

approximately 16% of the nation's GDP. In reality, this figure is still the highest in the developed

countries. For instance, new medical technologies, treatments and medications can generate extra

expenditure on healthcare, particularly if they are not substituting or reducing current expenses

for one reason or another (Erixon & Van der Marel, 2011). However, it is not true that these new

or extra expenses explain the greater portion of general health care expenses. For example,

public services expenditure has in the last decades accounted for a steady comparative share of

OECD countries’ overall health care expenses. Indeed, pharmaceutical expenditure has

decreased relatively from 1970, although complete public health expenditure has risen quickly

over the previous 15 years (Erixon & Van der Marel, 2011). True, medical innovations such as

CT scanners have led to increasing healthcare expenses, while the general trend in the rates of

investment and healthcare development does not match the rates shown for general healthcare

expenditure development. In addition, when the expenses of particular components in healthcare

manufacturing are compared across nations, there is a considerable distinction in the degree of

capital contributions to healthcare manufacturing among nations of comparable stage of growth.

Moreover, for an industry of "Baumol disease characteristics," such as healthcare, incomes

should not be sufficient to follow a broad GDP growth trend; health tax revenues should instead

rise beyond the overall GDP trend to cover rising disease expenses (Hartwig, 2011). There are

clear trends for the European nations we studied in lagging productivity rates and greater actual

costs for healthcare.

In addition to a prediction on the scheme in terms of future development opportunities, this essay

will discuss present health care expenses in the world environment.

Discussion:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

The literature describes several approaches to modelling healthcare costs. Some studies have

used domestic information while others have used macroeconomic aggregates. The review is

restricted to the latter research because of the scope of the research. Some past books depended

on cross-sectional technology while others used methods for panelling. The latter have been

based on static and dynamic models, often with distinct outcomes.

Income:

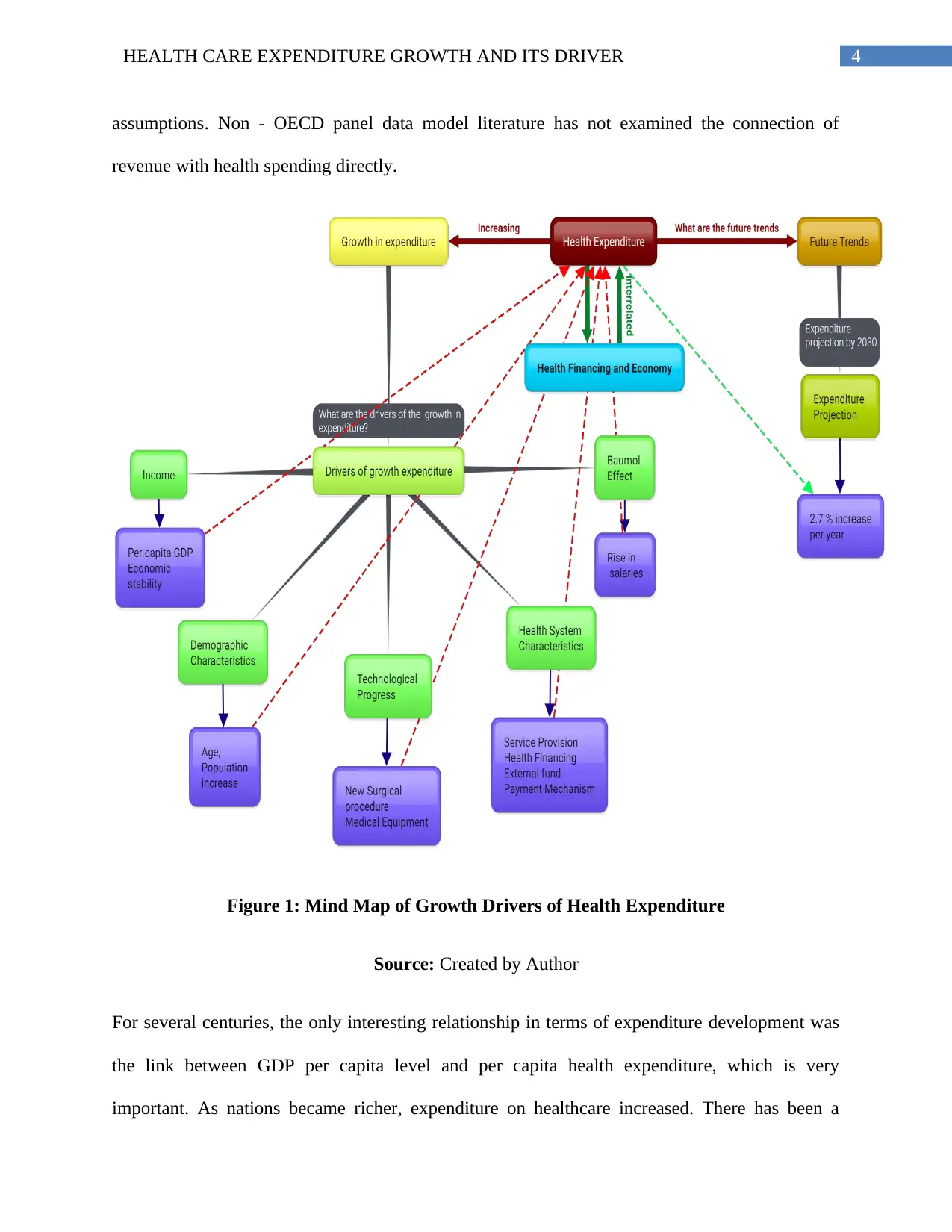

Revenue (per capita GDP) has been recognized as a significant explanation for the difference in

levels of overall health care expenditure and development in different nations. Cross-sectional

regressions of aggregate healthcare per capita GDP spending per capita in literature from OECD

countries have continuously demonstrated a considerably higher revenue elasticity of about 1.20

to 1.50 (Ke et al., 2011). Regressions of aggregate time series for different nations were mostly

comparable but had significant differences among nations. Likewise, a study used cross-sectional

data in 1997 in the worldwide literature and discovered, based on the information included, that

the income elasticity of health spending was between 1.133 and 1.275. OOP revenue elasticity

ranged from 0.884 to 1.033, while public health expenditure ranged from 1.069 to 1.194

(Musgrove et al. 2002). Gaag and Stimac have also used cross-sectional data from 175 nations in

2004 and have shown that the health expenses ' revenue elasticity is 1.09. They also reported the

outcomes by area and discovered that income elasticity in OECD countries ranged from 0.830 in

the Near East to 1.197 (Ke et al., 2011). The panel data accessibility has enabled the panel data

models to be evaluated for various periods of time. In several OECD countries, the income

elasticity based on cross-section data was discovered to be higher than that in line with past

outcomes. The outcome is vulnerable to the selection of the assumptions underlying the model,

however. In addition, certain writers acquired nearly one revenue elasticity under extra

The literature describes several approaches to modelling healthcare costs. Some studies have

used domestic information while others have used macroeconomic aggregates. The review is

restricted to the latter research because of the scope of the research. Some past books depended

on cross-sectional technology while others used methods for panelling. The latter have been

based on static and dynamic models, often with distinct outcomes.

Income:

Revenue (per capita GDP) has been recognized as a significant explanation for the difference in

levels of overall health care expenditure and development in different nations. Cross-sectional

regressions of aggregate healthcare per capita GDP spending per capita in literature from OECD

countries have continuously demonstrated a considerably higher revenue elasticity of about 1.20

to 1.50 (Ke et al., 2011). Regressions of aggregate time series for different nations were mostly

comparable but had significant differences among nations. Likewise, a study used cross-sectional

data in 1997 in the worldwide literature and discovered, based on the information included, that

the income elasticity of health spending was between 1.133 and 1.275. OOP revenue elasticity

ranged from 0.884 to 1.033, while public health expenditure ranged from 1.069 to 1.194

(Musgrove et al. 2002). Gaag and Stimac have also used cross-sectional data from 175 nations in

2004 and have shown that the health expenses ' revenue elasticity is 1.09. They also reported the

outcomes by area and discovered that income elasticity in OECD countries ranged from 0.830 in

the Near East to 1.197 (Ke et al., 2011). The panel data accessibility has enabled the panel data

models to be evaluated for various periods of time. In several OECD countries, the income

elasticity based on cross-section data was discovered to be higher than that in line with past

outcomes. The outcome is vulnerable to the selection of the assumptions underlying the model,

however. In addition, certain writers acquired nearly one revenue elasticity under extra

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

assumptions. Non - OECD panel data model literature has not examined the connection of

revenue with health spending directly.

Figure 1: Mind Map of Growth Drivers of Health Expenditure

Source: Created by Author

For several centuries, the only interesting relationship in terms of expenditure development was

the link between GDP per capita level and per capita health expenditure, which is very

important. As nations became richer, expenditure on healthcare increased. There has been a

assumptions. Non - OECD panel data model literature has not examined the connection of

revenue with health spending directly.

Figure 1: Mind Map of Growth Drivers of Health Expenditure

Source: Created by Author

For several centuries, the only interesting relationship in terms of expenditure development was

the link between GDP per capita level and per capita health expenditure, which is very

important. As nations became richer, expenditure on healthcare increased. There has been a

5HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

considerably higher interest in understanding health expenditure beyond GDP and welfare

development over the last decade (Ke et al., 2011). However, it is reasonable to say that this

study is still in its infancy and lacks credible information in specific for quantitative research.

At this point, it is worth noting that the above literature focuses primarily on the direct impact of

GDP on healthcare costs. Indeed, the inverse cause, where GDP is a function of health spending,

has also a theoretical foundation, as was described in, for instance at Erdil and Yetkiner (Erdil &

Yetkiner 2009). One way to consider this inverse impact is to treat health together with education

as another element of human capital. The GDP is based on healthcare expenditure by at

minimum two mechanisms. First, if spending on healthcare can be seen as an investment in the

human capital and because an accumulation of human capital is a key cause of economic growth,

an increase in spending on healthcare should eventually bring about greater GDP. Secondly,

increased health care expenditure in conjunction with efficient health intervention improves the

supply of work and productivity, eventually increasing GDP (Ke et al., 2011).

Therefore, there can be and needs to be a concurrent causality in both directions. If GDP and

health care costs simultaneously determine each other, their connection has an issue of

endogeneity. If this occurs, then conventional methods of estimation that assume that GDP is

exogenous will generate inconsistent parameter estimates. But even if the causalities exist in both

directions, it seems logical to expect that it does not happen instantly, but with a delay of time.

For this reason, the Granger-causality test seems to be the best way to determine the possible

direction of causality between health care expenses and GDP. Their research shows that Granger

is significantly bi-directional in 46 nations. The pattern relies on the country's GDP level in cases

where there is a unique causality. Their analyses show that one-way causation generally extends

between GDP and health expenditure in nations with low and medium income, whilst the

considerably higher interest in understanding health expenditure beyond GDP and welfare

development over the last decade (Ke et al., 2011). However, it is reasonable to say that this

study is still in its infancy and lacks credible information in specific for quantitative research.

At this point, it is worth noting that the above literature focuses primarily on the direct impact of

GDP on healthcare costs. Indeed, the inverse cause, where GDP is a function of health spending,

has also a theoretical foundation, as was described in, for instance at Erdil and Yetkiner (Erdil &

Yetkiner 2009). One way to consider this inverse impact is to treat health together with education

as another element of human capital. The GDP is based on healthcare expenditure by at

minimum two mechanisms. First, if spending on healthcare can be seen as an investment in the

human capital and because an accumulation of human capital is a key cause of economic growth,

an increase in spending on healthcare should eventually bring about greater GDP. Secondly,

increased health care expenditure in conjunction with efficient health intervention improves the

supply of work and productivity, eventually increasing GDP (Ke et al., 2011).

Therefore, there can be and needs to be a concurrent causality in both directions. If GDP and

health care costs simultaneously determine each other, their connection has an issue of

endogeneity. If this occurs, then conventional methods of estimation that assume that GDP is

exogenous will generate inconsistent parameter estimates. But even if the causalities exist in both

directions, it seems logical to expect that it does not happen instantly, but with a delay of time.

For this reason, the Granger-causality test seems to be the best way to determine the possible

direction of causality between health care expenses and GDP. Their research shows that Granger

is significantly bi-directional in 46 nations. The pattern relies on the country's GDP level in cases

where there is a unique causality. Their analyses show that one-way causation generally extends

between GDP and health expenditure in nations with low and medium income, whilst the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

opposite goes with nations with elevated revenue. In comparison, the Hartwig assessment of

Granger-causality in a panel of 21 OECD countries found no proof to show that per capita GDP

development is caused by health expenditure (Hartwig 2008). If Granger causality's other

direction is tested, the findings actually support the hypothesis that GDP determine health

expenses with a favourable indication.

Population age structure:

Sometimes the epidemiological need is also integrated by multiple proxies as a covariant. HIV

seroprevalence was used as a proxy by Lu et al. and discovered that there had been no important

link to GDP overall public health expenditures (Lu et al. 2010). The rates of maternal mortality

in African nations, Murthy and Okunade discovered, are not associated with health expenses

(Murthy & Okunade, 2009).

Technological progress:

Progress in technology is also a main driver of health spending. The impact with each of the

other drivers is strongly linked. As the riches of a country rises, medical technology

developments usually increase the range of health care facilities, but are cost-effective. By

expanding life expectancy and altering morbidity patterns, new techniques affect demographic

change. The inefficient use of new techniques can, however, also boost health expenditure

without improving health conditions (Chandra and Skinner, 2012). Progress in technology was

seen as a major driver of health care. Several proxies are used according to the sort of model

under account for modifications in medical treatment technology. The surgical procedures and

the amount of particular medical devices and life expectance and infant death are examples of

such proxies in cross-section research. Studies have found that the amount and development of

opposite goes with nations with elevated revenue. In comparison, the Hartwig assessment of

Granger-causality in a panel of 21 OECD countries found no proof to show that per capita GDP

development is caused by health expenditure (Hartwig 2008). If Granger causality's other

direction is tested, the findings actually support the hypothesis that GDP determine health

expenses with a favourable indication.

Population age structure:

Sometimes the epidemiological need is also integrated by multiple proxies as a covariant. HIV

seroprevalence was used as a proxy by Lu et al. and discovered that there had been no important

link to GDP overall public health expenditures (Lu et al. 2010). The rates of maternal mortality

in African nations, Murthy and Okunade discovered, are not associated with health expenses

(Murthy & Okunade, 2009).

Technological progress:

Progress in technology is also a main driver of health spending. The impact with each of the

other drivers is strongly linked. As the riches of a country rises, medical technology

developments usually increase the range of health care facilities, but are cost-effective. By

expanding life expectancy and altering morbidity patterns, new techniques affect demographic

change. The inefficient use of new techniques can, however, also boost health expenditure

without improving health conditions (Chandra and Skinner, 2012). Progress in technology was

seen as a major driver of health care. Several proxies are used according to the sort of model

under account for modifications in medical treatment technology. The surgical procedures and

the amount of particular medical devices and life expectance and infant death are examples of

such proxies in cross-section research. Studies have found that the amount and development of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

health expenditure were key to technological advances and variations in medical practice.

Technological progress was not regarded as a covariate by literature from non-OECD nations,

mostly because of an absence of credible technological progress information (Ke et al., 2011).

Health system characteristics:

Very few empirical studies have shown that the extent to which public funding for health care

spending is related to the degree of spending for health. In nations in OECD and in Eastern

European and Central Asian (ECA) nations (A. Wagstaff & Bank 2009), differences in spending

for health were considered between tax based and social insurance schemes. The OECD research

discovered that per capita health spending in nations where a social insurance system exists was

greater. The ECA research indicated that public health spending per capita in nations with social

insurance was greater than in nations that rely exclusively on general taxation. The connection

between external resources and domestic health expenditure in developing nations has recently

shown great interest. Gaag and Stimac discovered that while health-specific Official

Development Aid (ODA) has no important effect on complete health expenditure, health-specific

ODA has an elasticity of 0.138 compared to public health spending. Lu et al 2010 discovered a

favourable connection between health ODA channelling through the non-governmental industry

and overall public health expenditure, while it discovered an adverse correlation as channelled

through the governmental industry (Lu et al. 2010). Fee-for-service systems were generally more

expensive than capitation systems on average. In a research from the ECA nations, an increase in

government and private healthcare spending was connected with a change from funding clinics

to payment fees or patient payment systems via budgets. The ratio of hospital spending to

complete health care expenses is also strongly linked to health spending. The total supply of

doctors may have a positive effect on health expenditure. However, the Murthy and Okunade

health expenditure were key to technological advances and variations in medical practice.

Technological progress was not regarded as a covariate by literature from non-OECD nations,

mostly because of an absence of credible technological progress information (Ke et al., 2011).

Health system characteristics:

Very few empirical studies have shown that the extent to which public funding for health care

spending is related to the degree of spending for health. In nations in OECD and in Eastern

European and Central Asian (ECA) nations (A. Wagstaff & Bank 2009), differences in spending

for health were considered between tax based and social insurance schemes. The OECD research

discovered that per capita health spending in nations where a social insurance system exists was

greater. The ECA research indicated that public health spending per capita in nations with social

insurance was greater than in nations that rely exclusively on general taxation. The connection

between external resources and domestic health expenditure in developing nations has recently

shown great interest. Gaag and Stimac discovered that while health-specific Official

Development Aid (ODA) has no important effect on complete health expenditure, health-specific

ODA has an elasticity of 0.138 compared to public health spending. Lu et al 2010 discovered a

favourable connection between health ODA channelling through the non-governmental industry

and overall public health expenditure, while it discovered an adverse correlation as channelled

through the governmental industry (Lu et al. 2010). Fee-for-service systems were generally more

expensive than capitation systems on average. In a research from the ECA nations, an increase in

government and private healthcare spending was connected with a change from funding clinics

to payment fees or patient payment systems via budgets. The ratio of hospital spending to

complete health care expenses is also strongly linked to health spending. The total supply of

doctors may have a positive effect on health expenditure. However, the Murthy and Okunade

8HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

study of African countries found no relationship between the density of doctors and health

expenditure (Murthy & A. Okunade 2009).

Baumol effect:

The Baumol impact is that certain services tend to raise their comparative prices against other

products and services in the economy, reflecting the adverse productivity differential and wage

equalization across industries. In specific, health services prices will increase compared with

other prices because in high-productivity sectors salaries must maintain up with salaries. The

share of health care spending in GDP is expected to grow over time with price inelastic demand

(Hartwig 2008). Therefore, but not necessarily at their level, the Baumol effect can also be

significant in terms of increasing healthcare expenses, although it seems natural that the

healthcare expenses, which are a labour intensive good, in high salary economies will become

greater. However, it seems logical to ignore the Baumol effect as a phenomenon that primarily

impacts advanced economies in development studies.

Important explanatory variables for overall healthcare expenditure level and increase are: per

capita GDP, technological progress and variations in healthcare practice, as well as features of

the health systems. Recent studies acknowledge the significance of features of the health system

such as parameters for health funding, payment systems and provision of services. However, due

to information accessibility, the capacity to test these variables is restricted. This means that

certain significant factors may be missing from the assessment and therefore the econometric

findings should be interpreted carefully. Also, although incomes are strongly linked to health

care expenses, it is not evident what the conclusion is about income elasticity. While most

surveys tend to demonstrate that the elasticity of the revenue is higher than one, some trials

study of African countries found no relationship between the density of doctors and health

expenditure (Murthy & A. Okunade 2009).

Baumol effect:

The Baumol impact is that certain services tend to raise their comparative prices against other

products and services in the economy, reflecting the adverse productivity differential and wage

equalization across industries. In specific, health services prices will increase compared with

other prices because in high-productivity sectors salaries must maintain up with salaries. The

share of health care spending in GDP is expected to grow over time with price inelastic demand

(Hartwig 2008). Therefore, but not necessarily at their level, the Baumol effect can also be

significant in terms of increasing healthcare expenses, although it seems natural that the

healthcare expenses, which are a labour intensive good, in high salary economies will become

greater. However, it seems logical to ignore the Baumol effect as a phenomenon that primarily

impacts advanced economies in development studies.

Important explanatory variables for overall healthcare expenditure level and increase are: per

capita GDP, technological progress and variations in healthcare practice, as well as features of

the health systems. Recent studies acknowledge the significance of features of the health system

such as parameters for health funding, payment systems and provision of services. However, due

to information accessibility, the capacity to test these variables is restricted. This means that

certain significant factors may be missing from the assessment and therefore the econometric

findings should be interpreted carefully. Also, although incomes are strongly linked to health

care expenses, it is not evident what the conclusion is about income elasticity. While most

surveys tend to demonstrate that the elasticity of the revenue is higher than one, some trials

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

indicate that it is less than one. The results for revenue elasticity are in reality susceptible to the

selection of the underlying assumptions and the information used for estimating the model. It's

an empirical problem therefore.

Future trend and health expenditure projection:

Health expenditure for all OECD countries will continue to develop in the medium term. In the

lack of significant policy modifications, health expenditure per capita is expected to grow

slightly lower than it has done in the past, averaging 2.7 percent per year across the OECD from

2015-2030 (Lorenzoni, Marino, Morgan, & James, 2030). Health expenditure is expected to

output GDP in many situations and in a "base" situation to reach 10.2% on average.

Expenditures could reach up to 10.8% if cost containment strategies are ineffective and

increasing health systems expectations are not adequately managed (a scenario for' cost stress').

The development of health spending is anticipated to be slower with improved productivity and

efficient health promotion policies, although its GDP share is still predicted to rise to 9.6 percent

by 2030 (Lorenzoni et al., 2030). These numbers compare to 8.8% of GDP in 2015. In every

OECD nation, health spending as a share of GDP should rise, with major expectations in the

United States primarily due to population growth and coverage rises. The public health

expenditure is expected to increase slightly quicker than complete health expenditures, leading in

a 74.2 per cent increase to 77.4 percent in 2030. These findings are generally compatible with the

degree to which expenditure growth is achieved, although other cross-country projections model

public instead of complete health expenditure. The demographic impact in the basic situation

raises health spending by an OECD average of 0.7 percent per year. The predicted development

amounts to a quarter. Note that the demographic impact includes a 1.1-percent growth "pure age"

impact (Lorenzoni et al., 2030). This is tempered by a degree of reduction in morbidity that

indicate that it is less than one. The results for revenue elasticity are in reality susceptible to the

selection of the underlying assumptions and the information used for estimating the model. It's

an empirical problem therefore.

Future trend and health expenditure projection:

Health expenditure for all OECD countries will continue to develop in the medium term. In the

lack of significant policy modifications, health expenditure per capita is expected to grow

slightly lower than it has done in the past, averaging 2.7 percent per year across the OECD from

2015-2030 (Lorenzoni, Marino, Morgan, & James, 2030). Health expenditure is expected to

output GDP in many situations and in a "base" situation to reach 10.2% on average.

Expenditures could reach up to 10.8% if cost containment strategies are ineffective and

increasing health systems expectations are not adequately managed (a scenario for' cost stress').

The development of health spending is anticipated to be slower with improved productivity and

efficient health promotion policies, although its GDP share is still predicted to rise to 9.6 percent

by 2030 (Lorenzoni et al., 2030). These numbers compare to 8.8% of GDP in 2015. In every

OECD nation, health spending as a share of GDP should rise, with major expectations in the

United States primarily due to population growth and coverage rises. The public health

expenditure is expected to increase slightly quicker than complete health expenditures, leading in

a 74.2 per cent increase to 77.4 percent in 2030. These findings are generally compatible with the

degree to which expenditure growth is achieved, although other cross-country projections model

public instead of complete health expenditure. The demographic impact in the basic situation

raises health spending by an OECD average of 0.7 percent per year. The predicted development

amounts to a quarter. Note that the demographic impact includes a 1.1-percent growth "pure age"

impact (Lorenzoni et al., 2030). This is tempered by a degree of reduction in morbidity that

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

reduces the development of expenditure by 0.3 percent. Revenues are the main drivers, which

increase development by 1.5 per cent –equal to half the annual development in health

expenditure. Productivity limitations (the Baumol effect), which amounts to about one eighth of

the general development in expenditure, boost annual health expenditure by 0.4 per cent. Time-

specific impacts also boost the average annual health expenditures by 0.4 percent (Hartwig,

2008).

Conclusion:

The assessment of healthcare expenditure is essential for focusing on how healthcare expenditure

should be regulated. The increasing cost of health care is very important because of the fact that

the biggest expenditure is a comparatively tiny number of individuals. The system needs

adjustments and complete reorganization and is skewed in health care. Although current national

health expenditure has created more questions than answers, the system's future needs cannot be

ignored. Consequently, it is essential to have a healthcare system that reasonably accommodates

all actors. Nonetheless, a balance has been created with less fragile and pragmatic changes

between implementing a formidable health care plan and protecting egoistic political interests.

However, an appealing health system can still be achieved that can be funded from other sources.

The steady growth in healthcare expenses is a challenge for most industrialized countries. The

expenditure on nominal healthcare is growing not only, but also the share of GDP and

government spending is growing. In nations such as Germany, if policy does not change,

healthcare spending can expect to amount to more than 20 per cent of GDP for 15 or 20 years.

Although there is no such sharp rise in other nations, issues arise enough for us to examine

closely why healthcare expenses are rising and how healthcare can utilize resources in the future

more effectively. However, this is not in the interests of policy makers. In recent years, the major

reduces the development of expenditure by 0.3 percent. Revenues are the main drivers, which

increase development by 1.5 per cent –equal to half the annual development in health

expenditure. Productivity limitations (the Baumol effect), which amounts to about one eighth of

the general development in expenditure, boost annual health expenditure by 0.4 per cent. Time-

specific impacts also boost the average annual health expenditures by 0.4 percent (Hartwig,

2008).

Conclusion:

The assessment of healthcare expenditure is essential for focusing on how healthcare expenditure

should be regulated. The increasing cost of health care is very important because of the fact that

the biggest expenditure is a comparatively tiny number of individuals. The system needs

adjustments and complete reorganization and is skewed in health care. Although current national

health expenditure has created more questions than answers, the system's future needs cannot be

ignored. Consequently, it is essential to have a healthcare system that reasonably accommodates

all actors. Nonetheless, a balance has been created with less fragile and pragmatic changes

between implementing a formidable health care plan and protecting egoistic political interests.

However, an appealing health system can still be achieved that can be funded from other sources.

The steady growth in healthcare expenses is a challenge for most industrialized countries. The

expenditure on nominal healthcare is growing not only, but also the share of GDP and

government spending is growing. In nations such as Germany, if policy does not change,

healthcare spending can expect to amount to more than 20 per cent of GDP for 15 or 20 years.

Although there is no such sharp rise in other nations, issues arise enough for us to examine

closely why healthcare expenses are rising and how healthcare can utilize resources in the future

more effectively. However, this is not in the interests of policy makers. In recent years, the major

11HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE GROWTH AND ITS DRIVER

approach has been to contain rises in health care expenditures to make public health accessible.

The concept of reducing spending development through the rationing of models that do not

sacrifice the quality of health care services is rather encouraging policymakers with so-called

cost-containment prospects. This is not a sustainable approach. Cost containment can have

marginal impacts only if such strategies go on along present lines by addressing fresh and extra

health care expenditure and not the bulk of total health service expenditure. In the health

industry, the government should instead tackle the inefficiencies. This would not only help to

contain rises in costs; it could also enhance the competitiveness and development of the health

industry. Projections of health spending demonstrate both cost containment policies ' potential

and restrictions. This is because people want better healthcare and technological advances extend

the range of healthcare that can be achieved. The challenge consists of how nations can further

push the borders of what healthcare systems can deliver to maximize value for money in a

financially sustainable way.

approach has been to contain rises in health care expenditures to make public health accessible.

The concept of reducing spending development through the rationing of models that do not

sacrifice the quality of health care services is rather encouraging policymakers with so-called

cost-containment prospects. This is not a sustainable approach. Cost containment can have

marginal impacts only if such strategies go on along present lines by addressing fresh and extra

health care expenditure and not the bulk of total health service expenditure. In the health

industry, the government should instead tackle the inefficiencies. This would not only help to

contain rises in costs; it could also enhance the competitiveness and development of the health

industry. Projections of health spending demonstrate both cost containment policies ' potential

and restrictions. This is because people want better healthcare and technological advances extend

the range of healthcare that can be achieved. The challenge consists of how nations can further

push the borders of what healthcare systems can deliver to maximize value for money in a

financially sustainable way.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.