North-West University: Household Economic Behaviour Models Essay

VerifiedAdded on 2021/09/27

|11

|3249

|96

Essay

AI Summary

This essay, prepared for ECOH 611 at North-West University, delves into household economic behavior, contrasting unitary and collective models. It begins with an introduction to household economics, emphasizing the impact of microeconomic theories on economic outcomes. The essay provides an overview of unitary and collective models, including bargaining, non-cooperative, and cooperative approaches, examining their assumptions and views on intra-household resource distribution, labor supply, and time allocation. It critiques the traditional unitary model from a feminist economics perspective, discussing criticisms and implications. Furthermore, the essay addresses the evolution from unitary to collective models, assessing the implications for policymakers, especially concerning gender inequality. The discussion covers various household decision-making models, including Becker's framework and bargaining models, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. The essay also examines cooperative and non-cooperative models and addresses feminist economists' critiques. Finally, the essay concludes by acknowledging the limitations of economic theories and the ongoing debates that shape economic policy decisions.

Household Economic Behaviour: From unitary to collective models

Microeconomics: ECOH 611

Nickey Mphahlele

STUDENT NUMBER:25416553

Individual Essay 1

H.Com (Economics)

in the

SCHOOL OF ECONOMIC SCIENCES

in the

FACULTY OF ECONOMIC SCIENCES & IT

at the

NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY (VAAL TRIANGLE CAMPUS)

Lectures: Mr. Jacque de Jongh

Month year: 2019/04/19

Microeconomics: ECOH 611

Nickey Mphahlele

STUDENT NUMBER:25416553

Individual Essay 1

H.Com (Economics)

in the

SCHOOL OF ECONOMIC SCIENCES

in the

FACULTY OF ECONOMIC SCIENCES & IT

at the

NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY (VAAL TRIANGLE CAMPUS)

Lectures: Mr. Jacque de Jongh

Month year: 2019/04/19

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

INTRODUCTION

Economic theories from a micro and macro perspective have enormous impact on

policies which significantly determine economic outcomes of countries (Palley,

2008). Schneebaum & Mader (2013), define households simply as a group of

people who live together which microeconomics considers as basic unit of

decision, have played a significant role in structuringeconomies through their

omnipresence as crucial units of both production and consumption (Chiappori,

1997). Pioneered by Becker and Mincer, household economics encapsulates the

economic analysis of decisions made by households (Picard, De Palma & Inoa,

2014). Unitary household economic models and the collective models, which

include bargaining, non-cooperative as well as cooperative models all attempt to

theoretically examine and explain household behaviour in household economics.

Consumer theory of the traditional framework suggest a single utility function of

viewing household which is maximised under budget constraints (Vermeulen,

2002). The traditional view of household behaviour is however challenged by

several authors, who developed ‘collective’ approaches of viewing household

behaviour (McElroy & Horney, 1990; Manser & Brown 1980, McElroy, 1990).

Various approaches of collective household behaviour models share a

fundamental option, namely that households are made up of a group of individuals,

which are characterised by isolated preferences and share collective decision

processes (Chiappori & Bourguignon, 1992). The following discussion pertains to

providing an overview of different household economic models, their assumptions

and views of household behaviour. The specific focus is on how each model

explains intra-household resource distribution, labour supply and allocation of time

between the members of household. Secondly, considering the extensive criticism

by feminist economics paradigm of Becker’s (1965) traditional (unitary) model of

family behaviour and it’s understanding of demand, criticisms and implication of

household traditional model views are also discussed. Furthermore, an

explanation from a feminist economist’s perspective on household behaviour is

provided. Finally, considering the evolving views of household, from unitary and

INTRODUCTION

Economic theories from a micro and macro perspective have enormous impact on

policies which significantly determine economic outcomes of countries (Palley,

2008). Schneebaum & Mader (2013), define households simply as a group of

people who live together which microeconomics considers as basic unit of

decision, have played a significant role in structuringeconomies through their

omnipresence as crucial units of both production and consumption (Chiappori,

1997). Pioneered by Becker and Mincer, household economics encapsulates the

economic analysis of decisions made by households (Picard, De Palma & Inoa,

2014). Unitary household economic models and the collective models, which

include bargaining, non-cooperative as well as cooperative models all attempt to

theoretically examine and explain household behaviour in household economics.

Consumer theory of the traditional framework suggest a single utility function of

viewing household which is maximised under budget constraints (Vermeulen,

2002). The traditional view of household behaviour is however challenged by

several authors, who developed ‘collective’ approaches of viewing household

behaviour (McElroy & Horney, 1990; Manser & Brown 1980, McElroy, 1990).

Various approaches of collective household behaviour models share a

fundamental option, namely that households are made up of a group of individuals,

which are characterised by isolated preferences and share collective decision

processes (Chiappori & Bourguignon, 1992). The following discussion pertains to

providing an overview of different household economic models, their assumptions

and views of household behaviour. The specific focus is on how each model

explains intra-household resource distribution, labour supply and allocation of time

between the members of household. Secondly, considering the extensive criticism

by feminist economics paradigm of Becker’s (1965) traditional (unitary) model of

family behaviour and it’s understanding of demand, criticisms and implication of

household traditional model views are also discussed. Furthermore, an

explanation from a feminist economist’s perspective on household behaviour is

provided. Finally, considering the evolving views of household, from unitary and

3

collective models, assessment on major implications for policy makers in light of

the shifts are provided, with a specific focus on addressing gender inequality in

economies around the world.

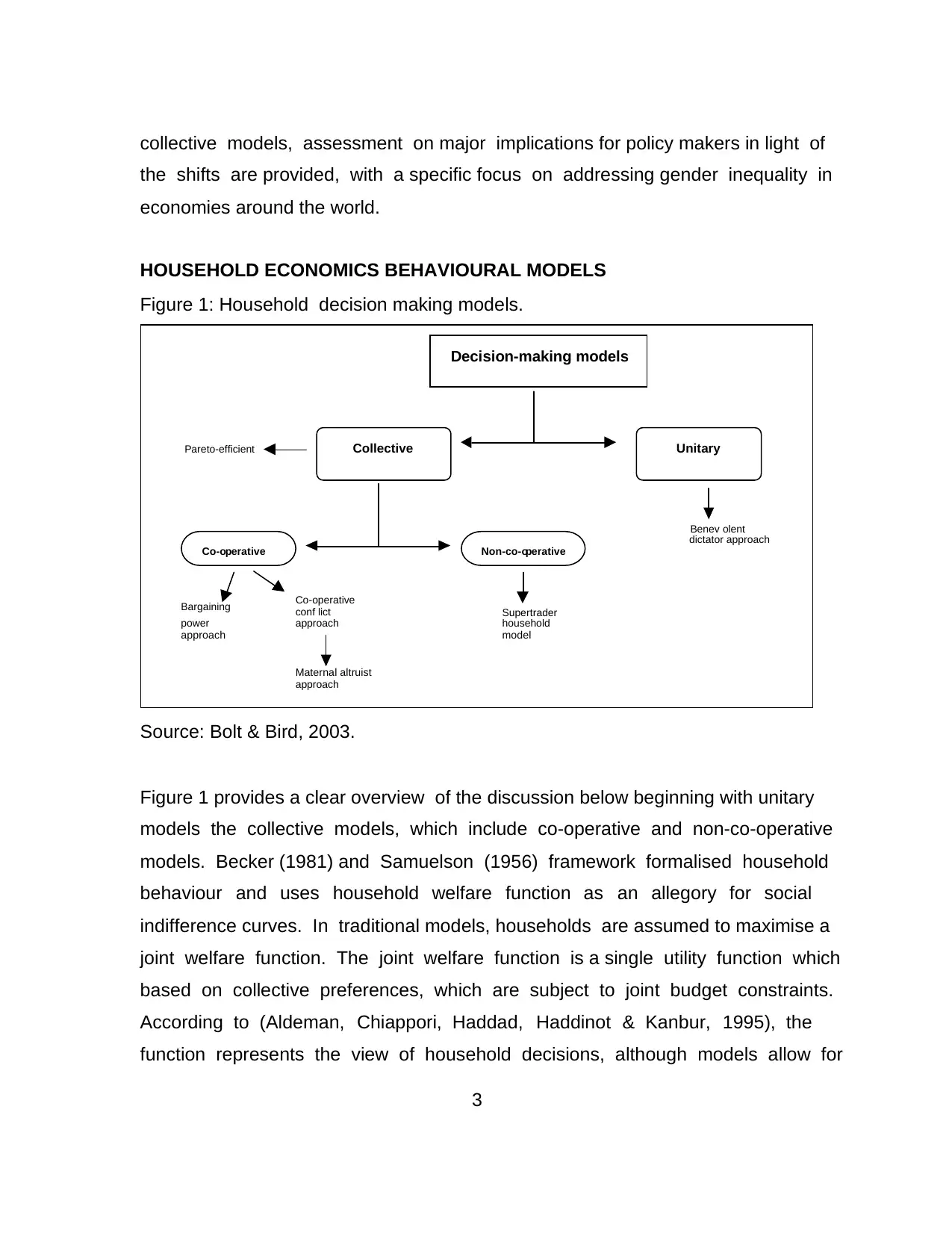

HOUSEHOLD ECONOMICS BEHAVIOURAL MODELS

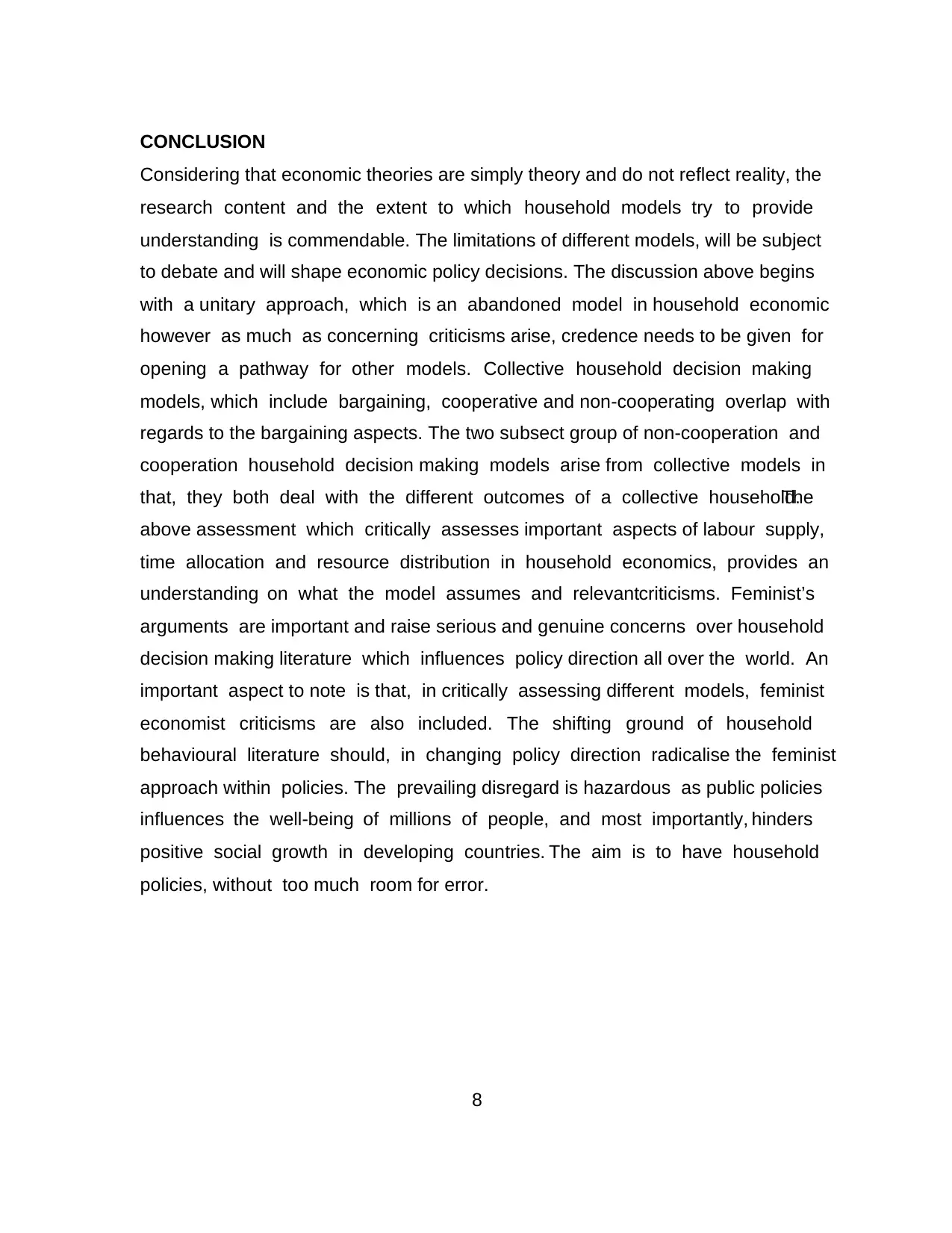

Figure 1: Household decision making models.

Source: Bolt & Bird, 2003.

Figure 1 provides a clear overview of the discussion below beginning with unitary

models the collective models, which include co-operative and non-co-operative

models. Becker (1981) and Samuelson (1956) framework formalised household

behaviour and uses household welfare function as an allegory for social

indifference curves. In traditional models, households are assumed to maximise a

joint welfare function. The joint welfare function is a single utility function which

based on collective preferences, which are subject to joint budget constraints.

According to (Aldeman, Chiappori, Haddad, Haddinot & Kanbur, 1995), the

function represents the view of household decisions, although models allow for

Decision-making models

Collective Unitary

Co-operative Non-co-operative

Pareto-efficient

Bargaining

power

approach

Benev olent

dictator approach

Supertrader

household

model

Co-operative

conf lict

approach

Maternal altruist

approach

collective models, assessment on major implications for policy makers in light of

the shifts are provided, with a specific focus on addressing gender inequality in

economies around the world.

HOUSEHOLD ECONOMICS BEHAVIOURAL MODELS

Figure 1: Household decision making models.

Source: Bolt & Bird, 2003.

Figure 1 provides a clear overview of the discussion below beginning with unitary

models the collective models, which include co-operative and non-co-operative

models. Becker (1981) and Samuelson (1956) framework formalised household

behaviour and uses household welfare function as an allegory for social

indifference curves. In traditional models, households are assumed to maximise a

joint welfare function. The joint welfare function is a single utility function which

based on collective preferences, which are subject to joint budget constraints.

According to (Aldeman, Chiappori, Haddad, Haddinot & Kanbur, 1995), the

function represents the view of household decisions, although models allow for

Decision-making models

Collective Unitary

Co-operative Non-co-operative

Pareto-efficient

Bargaining

power

approach

Benev olent

dictator approach

Supertrader

household

model

Co-operative

conf lict

approach

Maternal altruist

approach

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

prices to differ within the household. The single utility approach is however,

rejected by Donni & Molina (2018) and Vermeulen (2002) on a theoretical level,

arguing that the utility theory is purposive of studying individual choices and not

group choices. Formation and dissolution of the household is dependent on

individuals in household being married or divorced (Manser & Brown, 1980). As

the marriage is formed, income of family is assumed to be pooled together in

contribution to overall household (Beninger & Laisney, 2002). Schneebaum &

Mader’s (2013) definition of household, counter argues income pooling

assumption, as people do not need to be family to live together and income is not

shared even when people are family. Working hours of labour supply are based

on, income pooling assumption however the model fails to determine the source

of income (Bloemen, 2010). Dictatorship in the household is a given, as

responsibility of monitoring and sanctioning of those who fall foul of its rules and

to issue information flow and control are determined by one person (Becker, 1991).

Unitary models view of household behaviour is broad in that, it focuses on both

market and non-market activities of households, such as fertility, education of

children and allocation of time. Unitary models however fail to incorporate resource

distribution within household (Alderman et al, 1995). Due to the overall weakness

of the unitary model, alternative non-unitary representation models which focus on

intra-household decision making were adopted post 1980, after universal rejection

of the unitary approach (Donni & Molina 2018).

Collective models also known as bargaining models became popular post 1980 as

they explicitly address the issue of how individual preferences lead to collective

choices and bargaining amongst household members (Alderman et al, 1995). A

bargaining process within the household is assumed to take place as different

members have different preferences (Vermeulen, 2002). The model assumes

Pareto-optimality of allocation, which determines consumption choices and this

assumption also defines collective rationality (Beninger & Laisney, 2002).

Furthermore, the model also assumes that, preferences of individuals are of the

prices to differ within the household. The single utility approach is however,

rejected by Donni & Molina (2018) and Vermeulen (2002) on a theoretical level,

arguing that the utility theory is purposive of studying individual choices and not

group choices. Formation and dissolution of the household is dependent on

individuals in household being married or divorced (Manser & Brown, 1980). As

the marriage is formed, income of family is assumed to be pooled together in

contribution to overall household (Beninger & Laisney, 2002). Schneebaum &

Mader’s (2013) definition of household, counter argues income pooling

assumption, as people do not need to be family to live together and income is not

shared even when people are family. Working hours of labour supply are based

on, income pooling assumption however the model fails to determine the source

of income (Bloemen, 2010). Dictatorship in the household is a given, as

responsibility of monitoring and sanctioning of those who fall foul of its rules and

to issue information flow and control are determined by one person (Becker, 1991).

Unitary models view of household behaviour is broad in that, it focuses on both

market and non-market activities of households, such as fertility, education of

children and allocation of time. Unitary models however fail to incorporate resource

distribution within household (Alderman et al, 1995). Due to the overall weakness

of the unitary model, alternative non-unitary representation models which focus on

intra-household decision making were adopted post 1980, after universal rejection

of the unitary approach (Donni & Molina 2018).

Collective models also known as bargaining models became popular post 1980 as

they explicitly address the issue of how individual preferences lead to collective

choices and bargaining amongst household members (Alderman et al, 1995). A

bargaining process within the household is assumed to take place as different

members have different preferences (Vermeulen, 2002). The model assumes

Pareto-optimality of allocation, which determines consumption choices and this

assumption also defines collective rationality (Beninger & Laisney, 2002).

Furthermore, the model also assumes that, preferences of individuals are of the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

caring type (Bloemen, 2010). The distribution of resources process can be

explained using a two budget process; the first state is that non-labour earnings

are divided amongst household members and second stage is that there are

conditional divisions of income that are determined by individuals that supply

labour (Fortin & Lacroix, 1997). Using the second stage budget process

assumption, Chiappori (1988) shoes that the sharing rule of non-labour earnings

amongst household members. This essentially suggest that, income is quantifiable

and the non-quantifiable aspect of resource distribution can be determined using

a non-parametric statistical approach which has no assumption of resource

distribution. Considering that income is as a result of individuals supplying labour,

Doss (2013) opposed labour supply literature of collective model in that, due to

their higher bargaining power of labour suppliers, participation and non-

participation is dependent on individuals. The criticism is essential in that, it factors

two perspective of co-operative and non-cooperative decision making in

households.

Bargaining models views intra household resource distribution as an outcome of

bargaining process (Schneebaum & Mader, 2013). Household members, are

individualistically viewed as separate agents that have their own utility function and

preferences. Labour suppliers that have access to economic resources (labour and

non-labour) are a critical aspect of member’s bargaining power they determine the

allocation of time and resources (McElroy, 1990). Bargaining perspective allow for

either male of female dominance over the distribution of resources, established by

habits or social norms versus the results of outcomes which are determined by

bargaining and contestation (Manser & Brown, 1980). This assumption allows for

criticism from feminist views of bargaining models as policies that do not consider

male dominance can perpetuate the norm in societies if policy makers do not

explicitly deal with this. The model assumes Pareto efficiency as it is a subset of

collective model discussed above (Apps & Rees, 1997). Bargaining of the model

takes place over, consumption, production, labour, ownership decision making,

caring type (Bloemen, 2010). The distribution of resources process can be

explained using a two budget process; the first state is that non-labour earnings

are divided amongst household members and second stage is that there are

conditional divisions of income that are determined by individuals that supply

labour (Fortin & Lacroix, 1997). Using the second stage budget process

assumption, Chiappori (1988) shoes that the sharing rule of non-labour earnings

amongst household members. This essentially suggest that, income is quantifiable

and the non-quantifiable aspect of resource distribution can be determined using

a non-parametric statistical approach which has no assumption of resource

distribution. Considering that income is as a result of individuals supplying labour,

Doss (2013) opposed labour supply literature of collective model in that, due to

their higher bargaining power of labour suppliers, participation and non-

participation is dependent on individuals. The criticism is essential in that, it factors

two perspective of co-operative and non-cooperative decision making in

households.

Bargaining models views intra household resource distribution as an outcome of

bargaining process (Schneebaum & Mader, 2013). Household members, are

individualistically viewed as separate agents that have their own utility function and

preferences. Labour suppliers that have access to economic resources (labour and

non-labour) are a critical aspect of member’s bargaining power they determine the

allocation of time and resources (McElroy, 1990). Bargaining perspective allow for

either male of female dominance over the distribution of resources, established by

habits or social norms versus the results of outcomes which are determined by

bargaining and contestation (Manser & Brown, 1980). This assumption allows for

criticism from feminist views of bargaining models as policies that do not consider

male dominance can perpetuate the norm in societies if policy makers do not

explicitly deal with this. The model assumes Pareto efficiency as it is a subset of

collective model discussed above (Apps & Rees, 1997). Bargaining of the model

takes place over, consumption, production, labour, ownership decision making,

6

women’s wellbeing and children’s outcome (Doss, 2013). As mentioned above, an

outside option is considered a threat point which can either be that there is a utility

of either remaining single or getting divorced (Manser & Brown, 1980). Intra-

household spousal conflict of interest and preferences are assumed to be resolved

using the Nash bargaining solution to resolve their differences (Lundberg & Pollak,

1993). The benefits that arise from using bargaining power models is that there is

room left to analyse the importance of gender in making household decisions and

gives guidance for implication of public policies (Lundberg & Pollak, 2008).

However, there is a complexity to developing policies around the model as it

requires extensive research on demographics, gender dynamics, social roles and

social problems of households.

Cooperative models use Nash-bargaining model of marriage which treat intra

household behaviour of marriage as a cooperative game in which the members of

the household have their own utility function. Individuals are assumed to have free

choice whether to be involved in the household or not, with the key factor being

the utility decisions (Chiappori & Bourguignon, 1991). There are two key decision

making models; firstly, being the bargaining power process in that as people push

for their preferences, if agreement is not reached (determined by the cost of

compromising) individuals might break up from the household or ensue division of

household asset. Secondly being that, once a household is formed, decisions in

the household become bias in who would lose or gain from the separation of the

household (Alderman, 1995).

Non-cooperation may arise without explicit agreements such as divorce in the

household in labour supply, resource distribution and allocation of time. Assurance

of Pareto -optimality can arise in both cooperative and non-cooperative bargaining

models as couple can agree to not agree within the marriage and still stay together

(Manser & Brown, 1980). Non-cooperative models have also been developed to

capture the possibility of different preferences and utility functions (Schneebaum

& Mader, 2013). They are less common in literature, however,Schneebaum &

women’s wellbeing and children’s outcome (Doss, 2013). As mentioned above, an

outside option is considered a threat point which can either be that there is a utility

of either remaining single or getting divorced (Manser & Brown, 1980). Intra-

household spousal conflict of interest and preferences are assumed to be resolved

using the Nash bargaining solution to resolve their differences (Lundberg & Pollak,

1993). The benefits that arise from using bargaining power models is that there is

room left to analyse the importance of gender in making household decisions and

gives guidance for implication of public policies (Lundberg & Pollak, 2008).

However, there is a complexity to developing policies around the model as it

requires extensive research on demographics, gender dynamics, social roles and

social problems of households.

Cooperative models use Nash-bargaining model of marriage which treat intra

household behaviour of marriage as a cooperative game in which the members of

the household have their own utility function. Individuals are assumed to have free

choice whether to be involved in the household or not, with the key factor being

the utility decisions (Chiappori & Bourguignon, 1991). There are two key decision

making models; firstly, being the bargaining power process in that as people push

for their preferences, if agreement is not reached (determined by the cost of

compromising) individuals might break up from the household or ensue division of

household asset. Secondly being that, once a household is formed, decisions in

the household become bias in who would lose or gain from the separation of the

household (Alderman, 1995).

Non-cooperation may arise without explicit agreements such as divorce in the

household in labour supply, resource distribution and allocation of time. Assurance

of Pareto -optimality can arise in both cooperative and non-cooperative bargaining

models as couple can agree to not agree within the marriage and still stay together

(Manser & Brown, 1980). Non-cooperative models have also been developed to

capture the possibility of different preferences and utility functions (Schneebaum

& Mader, 2013). They are less common in literature, however,Schneebaum &

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

Mader (2013) suggest that Becker’s Supertrader household model (Becker, 1981)

can be useful in understanding non-cooperative models. Becker’s Supertrader

model relies on the assumption that individuals are not allowed to enter into

enforceable contracts which are binding, with each other and that the individuals

are not limited by social norms which other models are limited by. Time allocation,

labour supply and resource distribution are factors which are used to bargain with

each other, using implicit prices to determine resource distribution. Furthermore,

individual’s actions are conditional on other’s actions and thus the non-cooperative

model does not assume useful elements of time allocation, labour and resource

distribution, they are determined by interactions.

Bergmann (1995) a feminist economist, raises a concern of the household

economic models are fatally simplistic and to an extend misleading, as they have

not helped to solve, issues surrounding children. According to Bergmann (1995),

Gary Becker’s unitary model was developed to analyse economic growth and

markets. The empirical testing method is what Bergmann is concerned with as

Becker’s (1973) analysis is tested using females as subordinates of males and do

not consider the closely related bonds of equal partner parents, single parent

families, same-sex partners and other bonds which confines the focus of study.

Woolley (1996), in compared Bergmann’s criticism of collective models concludes

that she does not endorse a total rejection as there is a way that feminist economist

can apply them in some way or another. However, Woolley’s (1996) argument

does not deal with the useful arguments of collective approach and thus gives

credence Bergmann’s (1995) criticism as she deals with useful elements (Katz,

1997). In 1987, 25.2% of Rwanda households were female headed (Agarwal,

1997) which begs the question that, persistency side-lining women in policies and

not giving them preference as they are historically disadvantaged would result in

25.2% effect of Rwanda women being excluded economically and in social

assistance.

Mader (2013) suggest that Becker’s Supertrader household model (Becker, 1981)

can be useful in understanding non-cooperative models. Becker’s Supertrader

model relies on the assumption that individuals are not allowed to enter into

enforceable contracts which are binding, with each other and that the individuals

are not limited by social norms which other models are limited by. Time allocation,

labour supply and resource distribution are factors which are used to bargain with

each other, using implicit prices to determine resource distribution. Furthermore,

individual’s actions are conditional on other’s actions and thus the non-cooperative

model does not assume useful elements of time allocation, labour and resource

distribution, they are determined by interactions.

Bergmann (1995) a feminist economist, raises a concern of the household

economic models are fatally simplistic and to an extend misleading, as they have

not helped to solve, issues surrounding children. According to Bergmann (1995),

Gary Becker’s unitary model was developed to analyse economic growth and

markets. The empirical testing method is what Bergmann is concerned with as

Becker’s (1973) analysis is tested using females as subordinates of males and do

not consider the closely related bonds of equal partner parents, single parent

families, same-sex partners and other bonds which confines the focus of study.

Woolley (1996), in compared Bergmann’s criticism of collective models concludes

that she does not endorse a total rejection as there is a way that feminist economist

can apply them in some way or another. However, Woolley’s (1996) argument

does not deal with the useful arguments of collective approach and thus gives

credence Bergmann’s (1995) criticism as she deals with useful elements (Katz,

1997). In 1987, 25.2% of Rwanda households were female headed (Agarwal,

1997) which begs the question that, persistency side-lining women in policies and

not giving them preference as they are historically disadvantaged would result in

25.2% effect of Rwanda women being excluded economically and in social

assistance.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

CONCLUSION

Considering that economic theories are simply theory and do not reflect reality, the

research content and the extent to which household models try to provide

understanding is commendable. The limitations of different models, will be subject

to debate and will shape economic policy decisions. The discussion above begins

with a unitary approach, which is an abandoned model in household economic

however as much as concerning criticisms arise, credence needs to be given for

opening a pathway for other models. Collective household decision making

models, which include bargaining, cooperative and non-cooperating overlap with

regards to the bargaining aspects. The two subsect group of non-cooperation and

cooperation household decision making models arise from collective models in

that, they both deal with the different outcomes of a collective household.The

above assessment which critically assesses important aspects of labour supply,

time allocation and resource distribution in household economics, provides an

understanding on what the model assumes and relevantcriticisms. Feminist’s

arguments are important and raise serious and genuine concerns over household

decision making literature which influences policy direction all over the world. An

important aspect to note is that, in critically assessing different models, feminist

economist criticisms are also included. The shifting ground of household

behavioural literature should, in changing policy direction radicalise the feminist

approach within policies. The prevailing disregard is hazardous as public policies

influences the well-being of millions of people, and most importantly, hinders

positive social growth in developing countries. The aim is to have household

policies, without too much room for error.

CONCLUSION

Considering that economic theories are simply theory and do not reflect reality, the

research content and the extent to which household models try to provide

understanding is commendable. The limitations of different models, will be subject

to debate and will shape economic policy decisions. The discussion above begins

with a unitary approach, which is an abandoned model in household economic

however as much as concerning criticisms arise, credence needs to be given for

opening a pathway for other models. Collective household decision making

models, which include bargaining, cooperative and non-cooperating overlap with

regards to the bargaining aspects. The two subsect group of non-cooperation and

cooperation household decision making models arise from collective models in

that, they both deal with the different outcomes of a collective household.The

above assessment which critically assesses important aspects of labour supply,

time allocation and resource distribution in household economics, provides an

understanding on what the model assumes and relevantcriticisms. Feminist’s

arguments are important and raise serious and genuine concerns over household

decision making literature which influences policy direction all over the world. An

important aspect to note is that, in critically assessing different models, feminist

economist criticisms are also included. The shifting ground of household

behavioural literature should, in changing policy direction radicalise the feminist

approach within policies. The prevailing disregard is hazardous as public policies

influences the well-being of millions of people, and most importantly, hinders

positive social growth in developing countries. The aim is to have household

policies, without too much room for error.

9

REFERENCES

Alderman, H., Chiappori, P.A., Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J. & Kanbur, R. 1995.

Unitary versus collective models of the household: is it time to shift the burden of

proof?. The World Bank Research Observer, 10(1):1-19.

Agarwal, B. 1997. ''Bargaining'' and gender relations: Within and beyond the

household. Feminist economics, 3(1):1-51.

Apps, P.F., and Rees, R. 1997. Collective labour supply and household

production. Journal of political Economy, 105(1):178-190.

Becker, G.S. 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal,

75(299):493-517.

Becker, G.S. 1981. Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market

place. Economica, 48(189):1-15.

Beninger D.& Laisney, F. 2002. Comparison between unitary and collective

models of household labor supply with taxation. ZEW Discussion Paper, No. 02-

65. Mannheim: ZEW.

Bergmann, B. 1995. Becker's theory of the family: Preposterous

conclusions. Feminist economics, 1(1):141-150.

Bloemen, H. 2010. Income taxation in an empirical collective household labour

supply model with discrete hours. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, No. 101-

3. Amsterdam

Bolt, V.J. & Bird, K. 2003. The intrahousehold disadvantages framework: A

framework for the analysis of intra-household difference and inequality. Chronic

Poverty Research Centre Working Paper, No. 32. IZA Institute of Labour

Economics

Chiappori, P.A. 1988. Nash-bargained household’s decisions: a

comment. International Economic Review, 29(4):791-796.

Chiappori, P.A. and Bourguignon, F. 1992. Collective models of household

behaviour: an introduction. European Economic Review, 36(2-3):355-364.

Chiappori, P.A. 1997. Introducing household production in collective models of

labour supply. Journal of Political Economy, 105(1):191-209.

REFERENCES

Alderman, H., Chiappori, P.A., Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J. & Kanbur, R. 1995.

Unitary versus collective models of the household: is it time to shift the burden of

proof?. The World Bank Research Observer, 10(1):1-19.

Agarwal, B. 1997. ''Bargaining'' and gender relations: Within and beyond the

household. Feminist economics, 3(1):1-51.

Apps, P.F., and Rees, R. 1997. Collective labour supply and household

production. Journal of political Economy, 105(1):178-190.

Becker, G.S. 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal,

75(299):493-517.

Becker, G.S. 1981. Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market

place. Economica, 48(189):1-15.

Beninger D.& Laisney, F. 2002. Comparison between unitary and collective

models of household labor supply with taxation. ZEW Discussion Paper, No. 02-

65. Mannheim: ZEW.

Bergmann, B. 1995. Becker's theory of the family: Preposterous

conclusions. Feminist economics, 1(1):141-150.

Bloemen, H. 2010. Income taxation in an empirical collective household labour

supply model with discrete hours. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, No. 101-

3. Amsterdam

Bolt, V.J. & Bird, K. 2003. The intrahousehold disadvantages framework: A

framework for the analysis of intra-household difference and inequality. Chronic

Poverty Research Centre Working Paper, No. 32. IZA Institute of Labour

Economics

Chiappori, P.A. 1988. Nash-bargained household’s decisions: a

comment. International Economic Review, 29(4):791-796.

Chiappori, P.A. and Bourguignon, F. 1992. Collective models of household

behaviour: an introduction. European Economic Review, 36(2-3):355-364.

Chiappori, P.A. 1997. Introducing household production in collective models of

labour supply. Journal of Political Economy, 105(1):191-209.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Donni, O. & Molina, J.A. 2018. Household collective models: Three decades of

theoretical contributions and empirical evidence. IZA Discussion Paper, No.

11915. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labour.

Doss, C. 2013. Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing

countries. The World Bank Research Observer, 28(1):52-78.

Fortin, B. & Lacroix, G. 1997. A test of the unitary and collective models of

household labour supply. The Economic Journal, 107(443):933-955.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification

error. Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society, (1):153-161.

Katz, E. 1997. The intra-household economics of voice and exit. Feminist

economics, 3(3):25-46.

Lundberg, S. & Pollak, R.A. 1993. Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage

market. Journal of political Economy, 101(6):988-1010.

Manser, M. & Brown, M. 1980. Marriage and household decision-making: A

bargaining analysis. International economic review, (1).31-44.

McElroy, M.B. & Horney, M.J. 1990. Nash-bargained household decisions:

reply. International Economic Review, 237-242.

McElroy, M.B. 1990. The empirical content of Nash-bargained household

behaviour. Journal of human resources, 1(1-2):559-583.

Palley, T.I. 2018. Three globalizations, not two: rethinking the history and

economics of trade and globalization, FFM Working paper, No. 18.

Picard, N., De Palma, A. & Inoa, I. 2014. Intra-household decision models of

residential and job location. Paris: French National Centre for Scientific

Research.

Samuelson, P.A. 1956. Social indifference curves. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 70(1):1-22.

Schneebaum, A. & Mader, K. 2013. The gendered nature of intra-household

decision making in and across Europe. Working Paper, No. 157. Vienna: Vienna

University of Economics and Business.

Donni, O. & Molina, J.A. 2018. Household collective models: Three decades of

theoretical contributions and empirical evidence. IZA Discussion Paper, No.

11915. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labour.

Doss, C. 2013. Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing

countries. The World Bank Research Observer, 28(1):52-78.

Fortin, B. & Lacroix, G. 1997. A test of the unitary and collective models of

household labour supply. The Economic Journal, 107(443):933-955.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification

error. Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society, (1):153-161.

Katz, E. 1997. The intra-household economics of voice and exit. Feminist

economics, 3(3):25-46.

Lundberg, S. & Pollak, R.A. 1993. Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage

market. Journal of political Economy, 101(6):988-1010.

Manser, M. & Brown, M. 1980. Marriage and household decision-making: A

bargaining analysis. International economic review, (1).31-44.

McElroy, M.B. & Horney, M.J. 1990. Nash-bargained household decisions:

reply. International Economic Review, 237-242.

McElroy, M.B. 1990. The empirical content of Nash-bargained household

behaviour. Journal of human resources, 1(1-2):559-583.

Palley, T.I. 2018. Three globalizations, not two: rethinking the history and

economics of trade and globalization, FFM Working paper, No. 18.

Picard, N., De Palma, A. & Inoa, I. 2014. Intra-household decision models of

residential and job location. Paris: French National Centre for Scientific

Research.

Samuelson, P.A. 1956. Social indifference curves. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 70(1):1-22.

Schneebaum, A. & Mader, K. 2013. The gendered nature of intra-household

decision making in and across Europe. Working Paper, No. 157. Vienna: Vienna

University of Economics and Business.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

Vermeulen, F., 2002. Collective household models: principles and main

results. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16(4):533-564.

Woolley, F. 1996. Getting the better of Becker. Feminist Economics, 2(1):114-

120.

Vermeulen, F., 2002. Collective household models: principles and main

results. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16(4):533-564.

Woolley, F. 1996. Getting the better of Becker. Feminist Economics, 2(1):114-

120.

1 out of 11

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.