What determines the use of capital budgeting methods?

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/12

|13

|10139

|366

AI Summary

You are required to search at least FIVE (5) journal research articles related to capital budgeting and investment decision. Based on these research articles, you are required to answer the following questions:

1. In what way is the Net Present Value (NPV) consistent with the principle of shareholder wealth maximization? What happens to the value of a firm if a positive NPV is accepted? If a negative NPV project is accepted?

(15 marks)

2. Discuss should capital budgeting decisions be made solely on the basis of a project’s NPV.

(15 marks)

3. Explain how the expectation of changing costs of capital can be incorporated into the capital budgeting decisions.

(15 marks)

4. In most situations, should firms use a constant or a changing project cost of capital. Why or why not?

(15 marks)

Assignment Format for Part B:

a. Use single space and 12-point of Times New Roman font.

b. The assignment should

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

http://www.diva-portal.org

This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of Finance and Economics.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record):

Daunfeldt, S-O., Hartwig, F. (2014)

What determines the use of capital budgeting methods?: Evidence from Swedish listed

companies.

Journal of Finance and Economics, 2(4): 101-112

http://dx.doi.org/10.12691/jfe-2-4-1

Access to the published version may require subscription.

N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:du-12568

This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of Finance and Economics.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record):

Daunfeldt, S-O., Hartwig, F. (2014)

What determines the use of capital budgeting methods?: Evidence from Swedish listed

companies.

Journal of Finance and Economics, 2(4): 101-112

http://dx.doi.org/10.12691/jfe-2-4-1

Access to the published version may require subscription.

N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:du-12568

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Journal of Finance and Economics, 2014, Vol. 2, No. 4, 101-112

Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfe/2/4/1

© Science and Education Publishing

DOI:10.12691/jfe-2-4-1

What Determines the Use of Capital Budgeting Methods?

Evidence from Swedish Listed Companies

Sven-Olov Daunfeldt1,*, Fredrik Hartwig2

1Department of Trade, Industry and Business, HUI Research and Dalarna University, Stockholm and Borlänge, Sweden

2Department of Trade, Industry and Business, Dalarna University, Borlänge, Sweden

*Corresponding author: sven-olov.daunfeldt@hui.se

Received March 11, 2014; Revised March 18, 2014; Accepted March 27, 2014

Abstract Purpose: This paper aims to extend and contribute to prior research on the association between

company characteristics and choice of capital budgeting methods (CBMs). Design/methodology/approach: A

multivariate regression analysis on questionnaire data from 2005 and 2008 is used to study which factors determine

the choice of CBMs in Swedish listed companies. Findings: Our results supported hypotheses that Swedish listed

companies have become more sophisticated over the years (or at least less unsophisticated) which indicates a closing

of the theory-practice gap; that companies with greater leverage used payback more often; and that companies with

stricter debt targets and less management ownership employed accounting rate of return more frequent. Moreover,

larger companies used CBMs more often. Originality/value: The paper contributes to prior research within this

field by being the first Swedish study to examine the association between use of CBMs and as many as twelve

independent variables, including changes over time, by using multivariate regression analysis. The results are

compared to a US and a continental European study.

Keywords: investment decisions, capital budgeting methods, project valuation, Swedish listed companies, CFO,

sophisticated use

Cite This Article: Sven-Olov Daunfeldt, and Fredrik Hartwig, “What Determines the Use of Capital

Budgeting Methods? Evidence from Swedish Listed Companies.” Journal of Finance and Economics, vol. 2, no.

4 (2014): 101-112. doi: 10.12691/jfe-2-4-1.

1. Introduction

Management’s investment decision is pivotal for the

success of any company and over the years a number of

capital budgeting methods have evolved. The capital

budgeting method choice is not arbitrary, and textbooks in

financial management often recommend the net present

value method, while discouraging the use of other

techniques, such as the undiscounted payback method

(Brealey and Myers, 2003; Lumby and Jones, 2003; Smart

et al., 2004; Ross et al., 2005).

We use multivariate regression analysis on

questionnaire data from 2005 and 2008 to study which

factors determine the choice of capital budgeting methods

in Swedish listed companies. Our first question is to what

extent the recommended methods actually are used, i.e., is

there a gap between theory and practice? Second, we

investigate the average total use of capital budgeting

methods. Do Swedish listed companies typically use just

one method, or are two or even more used concurrently?

Third, we examine what factors determine the use of the

methods. For example, does size matter as suggested by

Stanley and Block, (1984), Pike (1988, 1996), Graham

and Harvey (2001), Sandahl and Sjögren (2003), and

Brounen et al. (2004)? The relation between size and

eleven other independent variables and eight capital

budgeting methods are analysed. Finally we compare our

results to studies of U.S. (Graham and Harvey, 2001) and

continental European (Brounen et al., 2004) listed

companies, which used data responding to the same

questionnaire as used here.

Capital budgeting decisions are very important for

financial managers, since they determine the choice of

investment projects that will affect company value. The

use of capital budgeting methods by U.S. and European

listed companies has been studied extensively (e.g.,

besides those already mentioned, Pike, 1988, 1989, 1996;

Pike and Sharp, 1989; Sangster, 1993; Block, 2007;

Hermes et al., 2007). [1] There have also been some

earlier studies of Sweden (Renck, 1966; Tell, 1978; Yard,

1987; Andersson, 1994; Segelod, 1995; Sandahl and

Sjögren, 2003; Holmén and Pramborg, 2009; Hartwig,

2012).

The present study differs in one important respect from

previous similar studies, the majority of which are based

on purely descriptive statistics. [2] Most studies thus

explore only use or non-use, or the frequency of use, of

capital budgeting methods, and not the association

between use and independent variables. When

relationships between use and independent variables have

been studied (e.g., Hartwig, 2012), only descriptive

statistical methods such as correlation analysis and

independent-samples t-tests are utilised, so the results

cannot be interpreted causally [3].

Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfe/2/4/1

© Science and Education Publishing

DOI:10.12691/jfe-2-4-1

What Determines the Use of Capital Budgeting Methods?

Evidence from Swedish Listed Companies

Sven-Olov Daunfeldt1,*, Fredrik Hartwig2

1Department of Trade, Industry and Business, HUI Research and Dalarna University, Stockholm and Borlänge, Sweden

2Department of Trade, Industry and Business, Dalarna University, Borlänge, Sweden

*Corresponding author: sven-olov.daunfeldt@hui.se

Received March 11, 2014; Revised March 18, 2014; Accepted March 27, 2014

Abstract Purpose: This paper aims to extend and contribute to prior research on the association between

company characteristics and choice of capital budgeting methods (CBMs). Design/methodology/approach: A

multivariate regression analysis on questionnaire data from 2005 and 2008 is used to study which factors determine

the choice of CBMs in Swedish listed companies. Findings: Our results supported hypotheses that Swedish listed

companies have become more sophisticated over the years (or at least less unsophisticated) which indicates a closing

of the theory-practice gap; that companies with greater leverage used payback more often; and that companies with

stricter debt targets and less management ownership employed accounting rate of return more frequent. Moreover,

larger companies used CBMs more often. Originality/value: The paper contributes to prior research within this

field by being the first Swedish study to examine the association between use of CBMs and as many as twelve

independent variables, including changes over time, by using multivariate regression analysis. The results are

compared to a US and a continental European study.

Keywords: investment decisions, capital budgeting methods, project valuation, Swedish listed companies, CFO,

sophisticated use

Cite This Article: Sven-Olov Daunfeldt, and Fredrik Hartwig, “What Determines the Use of Capital

Budgeting Methods? Evidence from Swedish Listed Companies.” Journal of Finance and Economics, vol. 2, no.

4 (2014): 101-112. doi: 10.12691/jfe-2-4-1.

1. Introduction

Management’s investment decision is pivotal for the

success of any company and over the years a number of

capital budgeting methods have evolved. The capital

budgeting method choice is not arbitrary, and textbooks in

financial management often recommend the net present

value method, while discouraging the use of other

techniques, such as the undiscounted payback method

(Brealey and Myers, 2003; Lumby and Jones, 2003; Smart

et al., 2004; Ross et al., 2005).

We use multivariate regression analysis on

questionnaire data from 2005 and 2008 to study which

factors determine the choice of capital budgeting methods

in Swedish listed companies. Our first question is to what

extent the recommended methods actually are used, i.e., is

there a gap between theory and practice? Second, we

investigate the average total use of capital budgeting

methods. Do Swedish listed companies typically use just

one method, or are two or even more used concurrently?

Third, we examine what factors determine the use of the

methods. For example, does size matter as suggested by

Stanley and Block, (1984), Pike (1988, 1996), Graham

and Harvey (2001), Sandahl and Sjögren (2003), and

Brounen et al. (2004)? The relation between size and

eleven other independent variables and eight capital

budgeting methods are analysed. Finally we compare our

results to studies of U.S. (Graham and Harvey, 2001) and

continental European (Brounen et al., 2004) listed

companies, which used data responding to the same

questionnaire as used here.

Capital budgeting decisions are very important for

financial managers, since they determine the choice of

investment projects that will affect company value. The

use of capital budgeting methods by U.S. and European

listed companies has been studied extensively (e.g.,

besides those already mentioned, Pike, 1988, 1989, 1996;

Pike and Sharp, 1989; Sangster, 1993; Block, 2007;

Hermes et al., 2007). [1] There have also been some

earlier studies of Sweden (Renck, 1966; Tell, 1978; Yard,

1987; Andersson, 1994; Segelod, 1995; Sandahl and

Sjögren, 2003; Holmén and Pramborg, 2009; Hartwig,

2012).

The present study differs in one important respect from

previous similar studies, the majority of which are based

on purely descriptive statistics. [2] Most studies thus

explore only use or non-use, or the frequency of use, of

capital budgeting methods, and not the association

between use and independent variables. When

relationships between use and independent variables have

been studied (e.g., Hartwig, 2012), only descriptive

statistical methods such as correlation analysis and

independent-samples t-tests are utilised, so the results

cannot be interpreted causally [3].

102 Journal of Finance and Economics

Our results confirm previous findings that larger

companies tend to use capital budgeting methods more

often when deciding on investments. The choice of capital

budgeting methods is also influenced by financial leverage,

growth opportunities, dividend pay-out policies, the

choice of target debt ratio, degree of management

ownership, foreign sales, and the education and other

individual characteristics of the CEO. The total use of

capital budgeting methods is lower in Sweden than in the

U.S. (Graham and Harvey, 2001), and continental Europe

(Brounen et al., 2004).

The next section presents capital budgeting methods

and explains why some of them are recommended by

textbooks and others not. Data and descriptive statistics on

the use of capital budgeting methods in Swedish listed

companies are presented in Section 3. Section 4 then

presents the empirical method and hypotheses to be tested.

Results are presented and discussed in Section 5. Section

6 summarises and draws conclusions.

2. The Use of Capital Budgeting Methods

When evaluating investments, top managers can choose

among many capital budgeting methods, some

recommended in textbooks, others not. In accordance with

Graham and Harvey (2001), we distinguish twelve capital

budgeting methods (Table 1).

Table 1. Capital budgeting methods, recommended or not by

textbooks

Method Recommended or not

a) Net present value (NPV) Recommended

b) Internal rate of return (IRR) Not recommended

c) Annuity Recommended

d) Earnings multiple (P/E) Not recommended

e) Adjusted present value (APV) Recommended

f) Pay-back Not recommended

g) Discounted pay-back Not recommended

h) Profitability index Recommended

i) Accounting rate of return (ARR) Not recommended

j) Sensitivity analysis Recommended

k) Value-at-risk (VAR) Recommended

l) Real options Recommended

Method Recommended or not

a) Net present value (NPV) Recommended

b) Internal rate of return (IRR) Not recommended

c) Annuity Recommended

d) Earnings multiple (P/E) Not recommended

e) Adjusted present value (APV) Recommended

f) Pay-back Not recommended

g) Discounted pay-back Not recommended

h) Profitability index Recommended

i) Accounting rate of return (ARR) Not recommended

j) Sensitivity analysis Recommended

k) Value-at-risk (VAR) Recommended

l) Real options Recommended

As noted, methods such as net present value (NPV) that

discount cash flows, are often recommended in financial

management textbooks. Brealey and Myers (2003), for

example, has a chapter on “why net present value leads to

better investment decisions than other criteria”. NPV is

recommended since it incorporates all cash-flows that the

investment generates as well as the time value of money.

Other methods, such as the internal rate of return (IRR)

and pay-back methods are often criticised. IRR can be

misleading when a choice must be made among mutually

exclusive projects, and also because of so-called multiple

rates of return (Ross et al., 2005), yet it is often used

(Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003;

Brounen et al., 2004; Bennouna et al., 2010).

Pay-back methods do not consider the time value of

money, and also ignores cash-flows that occur after the

maximum pay-back time (as defined by management), yet

it is also often used (Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl

and Sjögren, 2003; Brounen et al., 2004; Bennouna et al.,

2010). Discounted pay-back does not ignore the time

value of money, but still ignores cash-flows after the

maximum pay-back point.

The earnings multiple or price/earnings (P/E) method is

a variation on pay-back methods since it calculates how

many years it will take until the initial investment (the

share price) will be paid back by earnings. It considers

earnings instead of cash-flows and only considers one

earnings figure (instead of many), and again does not take

the time value of money into consideration. On the other

hand, this relative valuation method has the advantage of

letting the more or less efficient capital market guide the

decision.

The main disadvantage with ARR is (as the name

suggests) that it uses accounting numbers (instead of cash-

flows) and again does not consider the time value of

money (Ross et al., 2005). Note that management can

affect accounting numbers positively through real actions

even though their actions may have negative effects on

long-term value (Graham et al. (2005).

In principal, sensitivity analysis has no drawbacks, and

should be applied to see whether an investment will still

be profitable if one or more variables are changed.

Another method with no obvious drawbacks is real

options. It has been suggested that the reason why many

projects which look unprofitable at first glance are made

nevertheless is that management explicitly or implicitly

incorporated the possibility of making subsequent

investments (conditioned on the current project) in the

project evaluation.

Value-at-risk (VAR), measuring “…the worst loss over

a target horizon that will not be exceeded with a given

level of confidence” (Jorion, 2006; page viii), is a rather

new method. A disadvantage is that is does not estimate

how bad the loss might be if market conditions turn

abnormal (such as happened widely in 2008-2009).

When the highest net present value per monetary unit of

the initial outlay is calculated, a so-called profitability

index has been established. A potential limitation is that, if

applied carelessly and investment resources are

constrained, it can give bad advice (Brealey and Myers,

2003).

APV adds the value of any financial side-effects of an

investment to NPV, and should in principle have no

drawbacks (Ross et al., 2005). The annuity method is also

Our results confirm previous findings that larger

companies tend to use capital budgeting methods more

often when deciding on investments. The choice of capital

budgeting methods is also influenced by financial leverage,

growth opportunities, dividend pay-out policies, the

choice of target debt ratio, degree of management

ownership, foreign sales, and the education and other

individual characteristics of the CEO. The total use of

capital budgeting methods is lower in Sweden than in the

U.S. (Graham and Harvey, 2001), and continental Europe

(Brounen et al., 2004).

The next section presents capital budgeting methods

and explains why some of them are recommended by

textbooks and others not. Data and descriptive statistics on

the use of capital budgeting methods in Swedish listed

companies are presented in Section 3. Section 4 then

presents the empirical method and hypotheses to be tested.

Results are presented and discussed in Section 5. Section

6 summarises and draws conclusions.

2. The Use of Capital Budgeting Methods

When evaluating investments, top managers can choose

among many capital budgeting methods, some

recommended in textbooks, others not. In accordance with

Graham and Harvey (2001), we distinguish twelve capital

budgeting methods (Table 1).

Table 1. Capital budgeting methods, recommended or not by

textbooks

Method Recommended or not

a) Net present value (NPV) Recommended

b) Internal rate of return (IRR) Not recommended

c) Annuity Recommended

d) Earnings multiple (P/E) Not recommended

e) Adjusted present value (APV) Recommended

f) Pay-back Not recommended

g) Discounted pay-back Not recommended

h) Profitability index Recommended

i) Accounting rate of return (ARR) Not recommended

j) Sensitivity analysis Recommended

k) Value-at-risk (VAR) Recommended

l) Real options Recommended

Method Recommended or not

a) Net present value (NPV) Recommended

b) Internal rate of return (IRR) Not recommended

c) Annuity Recommended

d) Earnings multiple (P/E) Not recommended

e) Adjusted present value (APV) Recommended

f) Pay-back Not recommended

g) Discounted pay-back Not recommended

h) Profitability index Recommended

i) Accounting rate of return (ARR) Not recommended

j) Sensitivity analysis Recommended

k) Value-at-risk (VAR) Recommended

l) Real options Recommended

As noted, methods such as net present value (NPV) that

discount cash flows, are often recommended in financial

management textbooks. Brealey and Myers (2003), for

example, has a chapter on “why net present value leads to

better investment decisions than other criteria”. NPV is

recommended since it incorporates all cash-flows that the

investment generates as well as the time value of money.

Other methods, such as the internal rate of return (IRR)

and pay-back methods are often criticised. IRR can be

misleading when a choice must be made among mutually

exclusive projects, and also because of so-called multiple

rates of return (Ross et al., 2005), yet it is often used

(Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003;

Brounen et al., 2004; Bennouna et al., 2010).

Pay-back methods do not consider the time value of

money, and also ignores cash-flows that occur after the

maximum pay-back time (as defined by management), yet

it is also often used (Graham and Harvey, 2001; Sandahl

and Sjögren, 2003; Brounen et al., 2004; Bennouna et al.,

2010). Discounted pay-back does not ignore the time

value of money, but still ignores cash-flows after the

maximum pay-back point.

The earnings multiple or price/earnings (P/E) method is

a variation on pay-back methods since it calculates how

many years it will take until the initial investment (the

share price) will be paid back by earnings. It considers

earnings instead of cash-flows and only considers one

earnings figure (instead of many), and again does not take

the time value of money into consideration. On the other

hand, this relative valuation method has the advantage of

letting the more or less efficient capital market guide the

decision.

The main disadvantage with ARR is (as the name

suggests) that it uses accounting numbers (instead of cash-

flows) and again does not consider the time value of

money (Ross et al., 2005). Note that management can

affect accounting numbers positively through real actions

even though their actions may have negative effects on

long-term value (Graham et al. (2005).

In principal, sensitivity analysis has no drawbacks, and

should be applied to see whether an investment will still

be profitable if one or more variables are changed.

Another method with no obvious drawbacks is real

options. It has been suggested that the reason why many

projects which look unprofitable at first glance are made

nevertheless is that management explicitly or implicitly

incorporated the possibility of making subsequent

investments (conditioned on the current project) in the

project evaluation.

Value-at-risk (VAR), measuring “…the worst loss over

a target horizon that will not be exceeded with a given

level of confidence” (Jorion, 2006; page viii), is a rather

new method. A disadvantage is that is does not estimate

how bad the loss might be if market conditions turn

abnormal (such as happened widely in 2008-2009).

When the highest net present value per monetary unit of

the initial outlay is calculated, a so-called profitability

index has been established. A potential limitation is that, if

applied carelessly and investment resources are

constrained, it can give bad advice (Brealey and Myers,

2003).

APV adds the value of any financial side-effects of an

investment to NPV, and should in principle have no

drawbacks (Ross et al., 2005). The annuity method is also

Journal of Finance and Economics 103

a variant of NPV. If you know the annuity of an

investment, and how many years it should generate net

cash-inflows or outflows, then you can easily calculate its

NPV by discounting the annuity with the relevant

weighted average cost of capital.

3. Data and Descriptive Statistics

To analyse what determines the choice of capital

budgeting methods in Sweden, a questionnaire (Appendix

1) was sent in 2005 and 2008 to the CFOs of all Swedish

companies listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. To

facilitate a comparison between the surveys, the questions

were the same as used by Graham and Harvey (2001) and

Brounen et al. (2004). [4] If no executive had the title

CFO, then the questionnaire was sent to another senior

executive (controller, treasurer, or CEO) responsible for

financial management.

In 2005, the questionnaire was sent to 244 companies

by postal mail three times, with response deadlines 8

January, 14 March, and 23 May. Non-respondents by the

first deadline were contacted by phone to encourage them

to respond. In the end, 112 questionnaires (45.9%) were

returned. However, seven were not useable and were

dropped, leaving an adjusted response rate of 43.0%.

In 2008, the questionnaire was sent to 249 companies

by postal mail four times, with response deadlines 18

February, 10 March, 3 April, and 16 June. Again, non-

respondents by the first deadline were contacted by phone.

In the end, 92 (36.9%) questionnaires were returned. Four

were not useable, leaving an adjusted response rate of

35.3%. The total adjusted response rate for the two

surveys was thus 39.1%, compared to 9% for Graham and

Harvey (2001) and 5% for Brounen et al. (2004).

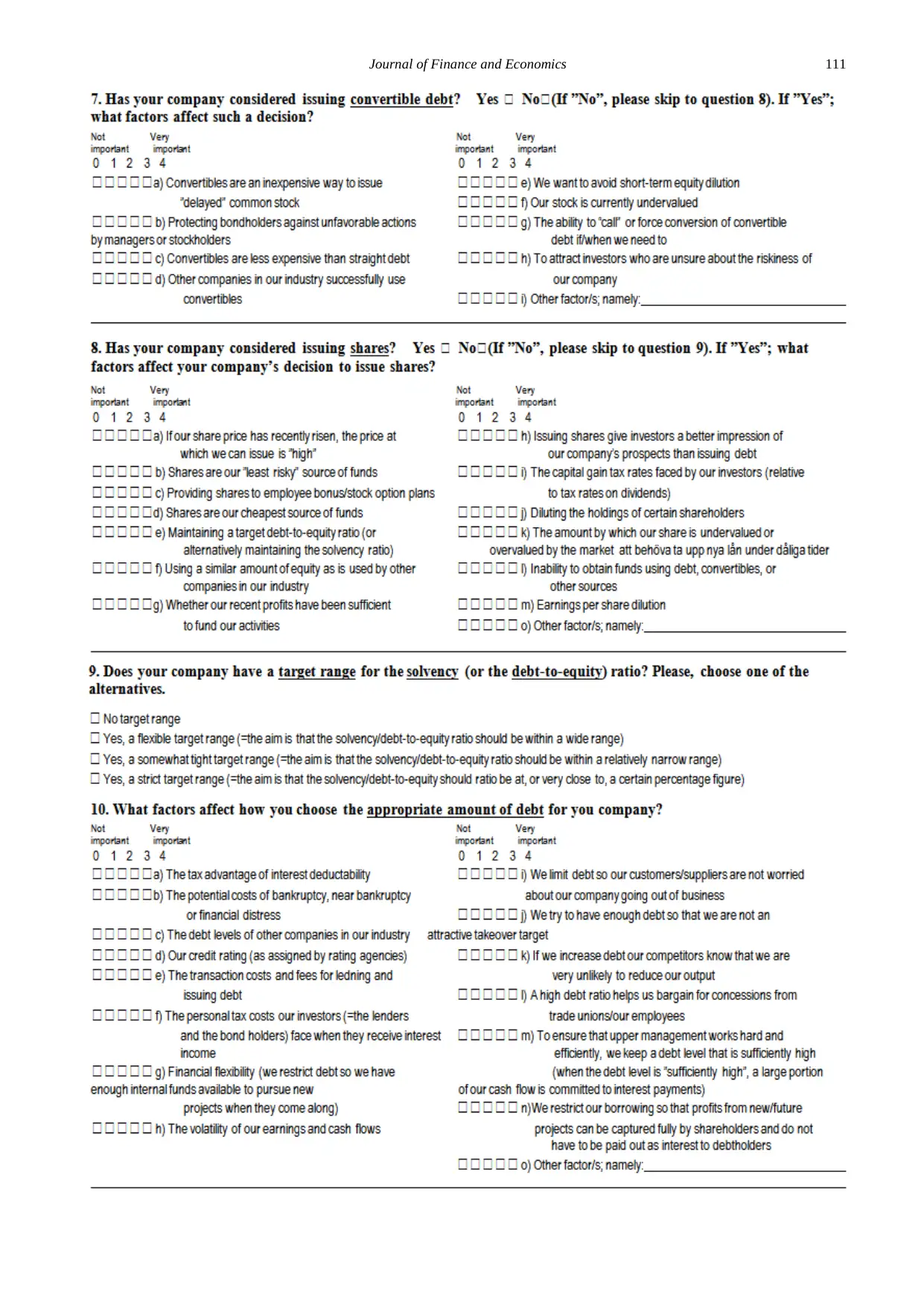

In simple probit analysis of the response rate the

probability of response was statistically significantly

higher for larger companies, and the probability to answer

the survey was higher in 2005 compared to 2008. Industry

classification, P/E-ratio, degree of leverage, and dividend

pay-out level did not have statistically significant effects

on the probability of response (Table A1 in Appendix 2).

The questionnaire made clear that questions regarding

capital investment referred to all non-routine capital

investments accepted or rejected at group/parent-company

level. The reason for this framing was that otherwise, i.e.,

if questions were taken to refer to all investments in the

company (including investments accepted or rejected at

subsidiary level), then the respondents probably would not

be able to give credible answers.

3.1. Dependent Variables

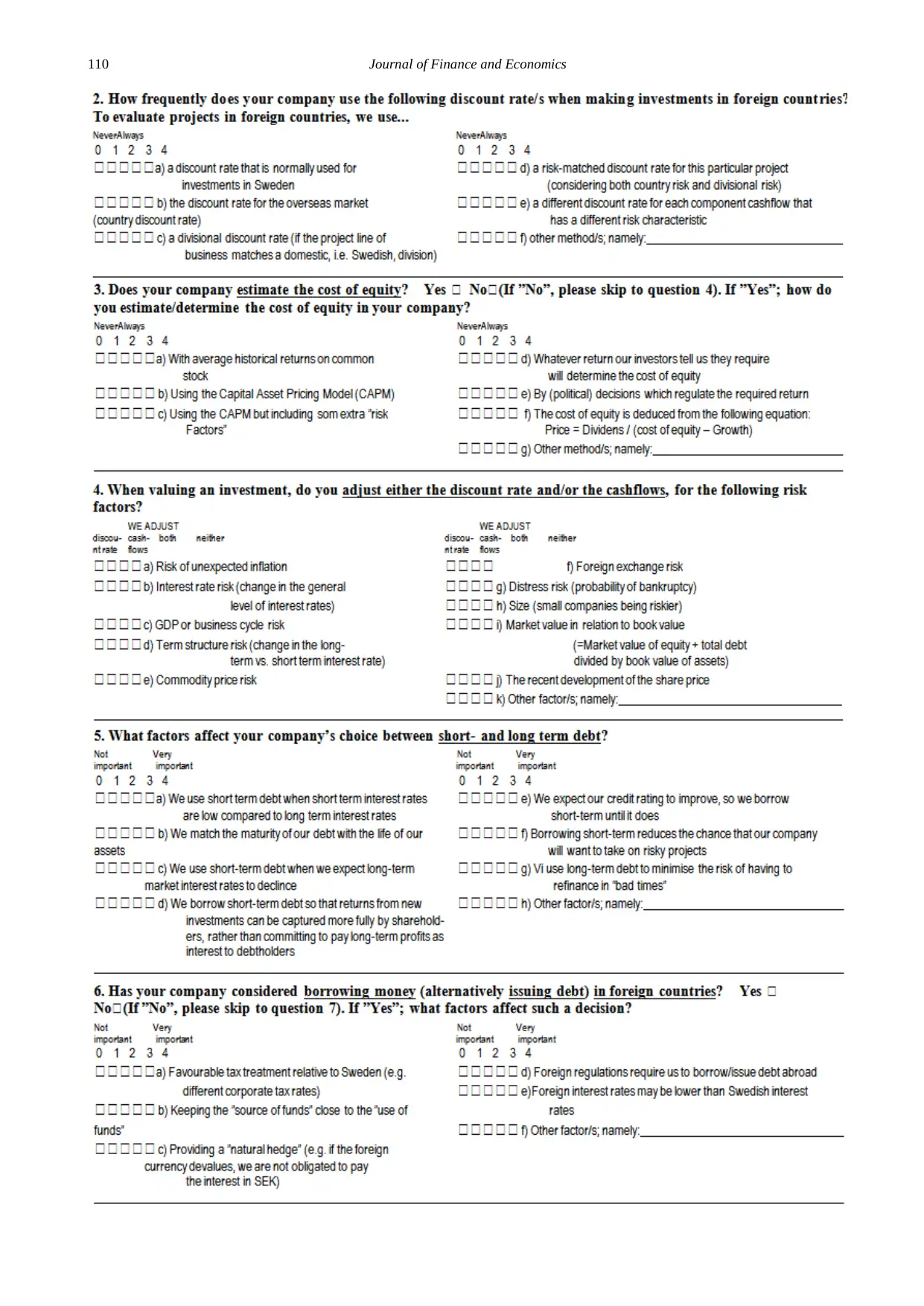

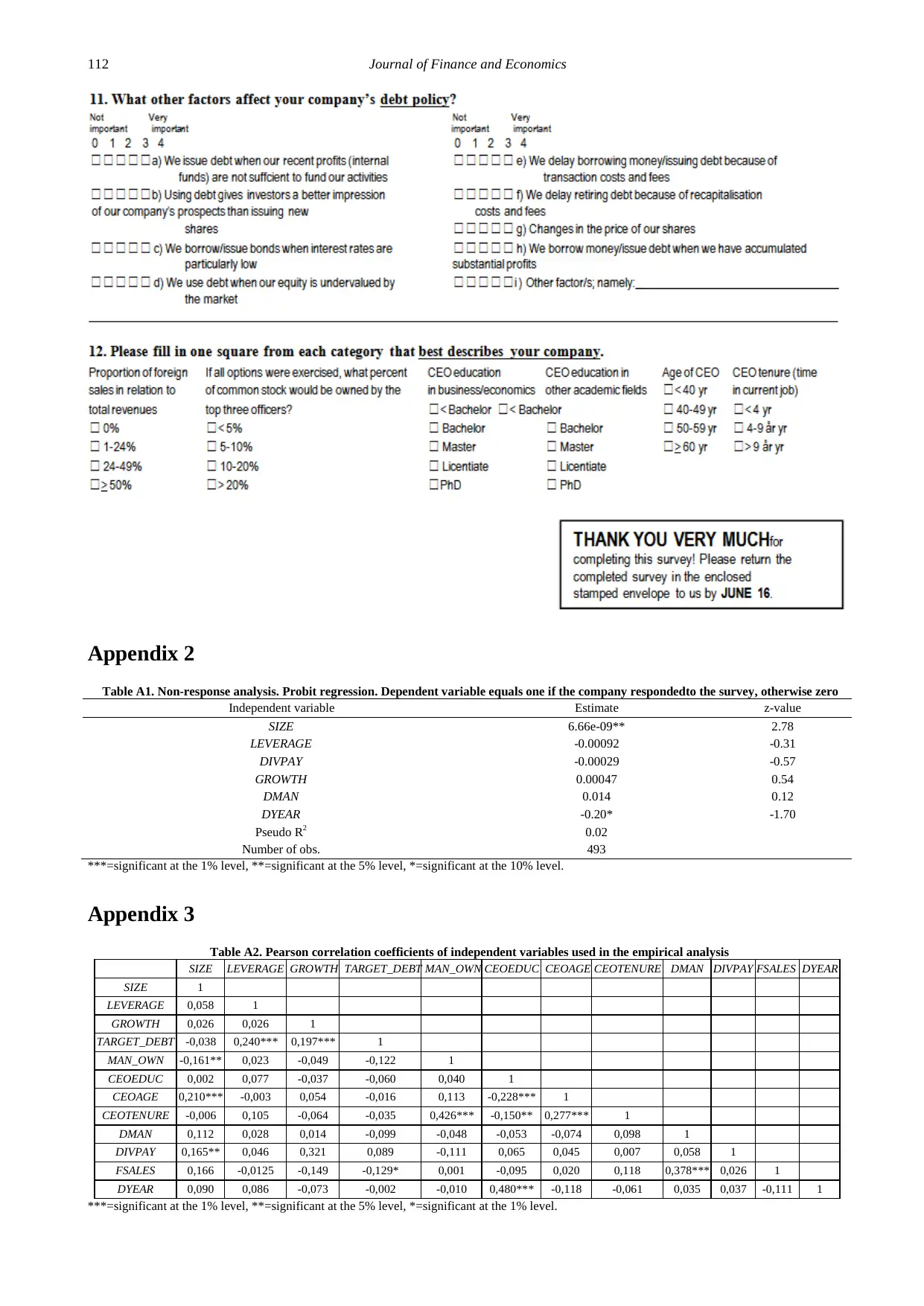

The questionnaire (Appendix 1) consists of three main

questions regarding the use of capital budgeting and cost-

of-capital estimation techniques. [5] Data from question

one, “How often do you use the following capital

budgeting methods (on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 = never

and 4 = always)?”, was used to construct our dependent

variables. The capital budgeting methods asked about

were:

a). Net-present value (NPV)

b). Internal rate of return (IRR)

c). Annuity

d). Earnings multiple

e). The adjusted present value (APV)

f). Pay-back

g). Discounted pay-back

h). Profitability index

i). Accounting rate of return (ARR)

j). Sensitivity analysis

k). Value-at-risk (VAR)

l). Real options

The number and share of respondents reporting that

they occasionally or never use or frequently or always use

each method are reported in Table 2. Annuity, adjusted

present value (APV), value-at-risk, and real options were

far less used than the other methods. We excluded them

from further analysis as not providing sufficient variation

to analyze.

Table 2. Number and proportion of companies that used each capital

budgeting Method never or occasionally (0-2) vs frequently or

always (3-4)

Capital budgeting method 0-2 % 3-4 %

(a) NPV 75 38.86% 118 61.14%

(b) IRR 135 69.95% 58 30.05%

(c) Annuity 187 96.89% 6 3.11%

(d) Earnings multiple approach 139 72.02% 54 27.98%

(e) APV 180 93.26% 13 6.74%

(f) Pay-back 88 45.60% 105 54.40%

(g) Discounted pay-back 160 82.90% 33 17.10%

(h) Profitability index 169 87.56% 24 12.44%

(i) ARR 147 76.17% 46 23.83%

(j) Sensitivity analysis 106 54.92% 87 45.08%

(k) VAR 180 93.26% 13 6.74%

(l) Real options 189 97.93% 4 2,07%

The recommended methods used frequently or always

by the most listed companies in Sweden were the net

present value (61%) and sensitivity analysis (45%), but

not recommended pay-back method was used frequently

or always by 54% of the respondents.

Mean values, standard deviations, and differences in

mean values for the most used capital budgeting methods

in 2005 and 2008 are reported in Table 3. Higher mean

values indicate more extensive use of the method.

Table 3. Mean values, standard deviations, and differences in mean

values for the most used capital budgeting methods in 2005 and 2008

2005 2008

Dependent variable Mean Sd Mean Sd Difference

(a) NPV 2.50 1.38 2.55 1.38 0.05

(b) IRR 1.57 1.58 1.27 1.45 -0.30***

(d) Earnings multiple 1.36 1.61 1.41 1.57 0.05

(f) Pay-back 2.39 1.41 2.20 1.47 -0.19

(g) Discounted pay-back 1.08 1.42 0.74 1.31 -0.34***

(h) Profitability index 0.69 1.26 0.72 1.20 0.03

(i) ARR 1.14 1.55 1.05 1.45 -0.10

(j) Sensitivity analysis 1.92 1.63 2.05 1.53 0.12

Note: *** indicates that the difference is statistically significant at the

1% level.

The differences between 2005 and 2008 are small,

usually not significantly different from zero. The biggest

differences are that IRR and the discounted pay-back

a variant of NPV. If you know the annuity of an

investment, and how many years it should generate net

cash-inflows or outflows, then you can easily calculate its

NPV by discounting the annuity with the relevant

weighted average cost of capital.

3. Data and Descriptive Statistics

To analyse what determines the choice of capital

budgeting methods in Sweden, a questionnaire (Appendix

1) was sent in 2005 and 2008 to the CFOs of all Swedish

companies listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. To

facilitate a comparison between the surveys, the questions

were the same as used by Graham and Harvey (2001) and

Brounen et al. (2004). [4] If no executive had the title

CFO, then the questionnaire was sent to another senior

executive (controller, treasurer, or CEO) responsible for

financial management.

In 2005, the questionnaire was sent to 244 companies

by postal mail three times, with response deadlines 8

January, 14 March, and 23 May. Non-respondents by the

first deadline were contacted by phone to encourage them

to respond. In the end, 112 questionnaires (45.9%) were

returned. However, seven were not useable and were

dropped, leaving an adjusted response rate of 43.0%.

In 2008, the questionnaire was sent to 249 companies

by postal mail four times, with response deadlines 18

February, 10 March, 3 April, and 16 June. Again, non-

respondents by the first deadline were contacted by phone.

In the end, 92 (36.9%) questionnaires were returned. Four

were not useable, leaving an adjusted response rate of

35.3%. The total adjusted response rate for the two

surveys was thus 39.1%, compared to 9% for Graham and

Harvey (2001) and 5% for Brounen et al. (2004).

In simple probit analysis of the response rate the

probability of response was statistically significantly

higher for larger companies, and the probability to answer

the survey was higher in 2005 compared to 2008. Industry

classification, P/E-ratio, degree of leverage, and dividend

pay-out level did not have statistically significant effects

on the probability of response (Table A1 in Appendix 2).

The questionnaire made clear that questions regarding

capital investment referred to all non-routine capital

investments accepted or rejected at group/parent-company

level. The reason for this framing was that otherwise, i.e.,

if questions were taken to refer to all investments in the

company (including investments accepted or rejected at

subsidiary level), then the respondents probably would not

be able to give credible answers.

3.1. Dependent Variables

The questionnaire (Appendix 1) consists of three main

questions regarding the use of capital budgeting and cost-

of-capital estimation techniques. [5] Data from question

one, “How often do you use the following capital

budgeting methods (on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 = never

and 4 = always)?”, was used to construct our dependent

variables. The capital budgeting methods asked about

were:

a). Net-present value (NPV)

b). Internal rate of return (IRR)

c). Annuity

d). Earnings multiple

e). The adjusted present value (APV)

f). Pay-back

g). Discounted pay-back

h). Profitability index

i). Accounting rate of return (ARR)

j). Sensitivity analysis

k). Value-at-risk (VAR)

l). Real options

The number and share of respondents reporting that

they occasionally or never use or frequently or always use

each method are reported in Table 2. Annuity, adjusted

present value (APV), value-at-risk, and real options were

far less used than the other methods. We excluded them

from further analysis as not providing sufficient variation

to analyze.

Table 2. Number and proportion of companies that used each capital

budgeting Method never or occasionally (0-2) vs frequently or

always (3-4)

Capital budgeting method 0-2 % 3-4 %

(a) NPV 75 38.86% 118 61.14%

(b) IRR 135 69.95% 58 30.05%

(c) Annuity 187 96.89% 6 3.11%

(d) Earnings multiple approach 139 72.02% 54 27.98%

(e) APV 180 93.26% 13 6.74%

(f) Pay-back 88 45.60% 105 54.40%

(g) Discounted pay-back 160 82.90% 33 17.10%

(h) Profitability index 169 87.56% 24 12.44%

(i) ARR 147 76.17% 46 23.83%

(j) Sensitivity analysis 106 54.92% 87 45.08%

(k) VAR 180 93.26% 13 6.74%

(l) Real options 189 97.93% 4 2,07%

The recommended methods used frequently or always

by the most listed companies in Sweden were the net

present value (61%) and sensitivity analysis (45%), but

not recommended pay-back method was used frequently

or always by 54% of the respondents.

Mean values, standard deviations, and differences in

mean values for the most used capital budgeting methods

in 2005 and 2008 are reported in Table 3. Higher mean

values indicate more extensive use of the method.

Table 3. Mean values, standard deviations, and differences in mean

values for the most used capital budgeting methods in 2005 and 2008

2005 2008

Dependent variable Mean Sd Mean Sd Difference

(a) NPV 2.50 1.38 2.55 1.38 0.05

(b) IRR 1.57 1.58 1.27 1.45 -0.30***

(d) Earnings multiple 1.36 1.61 1.41 1.57 0.05

(f) Pay-back 2.39 1.41 2.20 1.47 -0.19

(g) Discounted pay-back 1.08 1.42 0.74 1.31 -0.34***

(h) Profitability index 0.69 1.26 0.72 1.20 0.03

(i) ARR 1.14 1.55 1.05 1.45 -0.10

(j) Sensitivity analysis 1.92 1.63 2.05 1.53 0.12

Note: *** indicates that the difference is statistically significant at the

1% level.

The differences between 2005 and 2008 are small,

usually not significantly different from zero. The biggest

differences are that IRR and the discounted pay-back

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

104 Journal of Finance and Economics

(both not recommended) were less used in 2008 than in

2005.

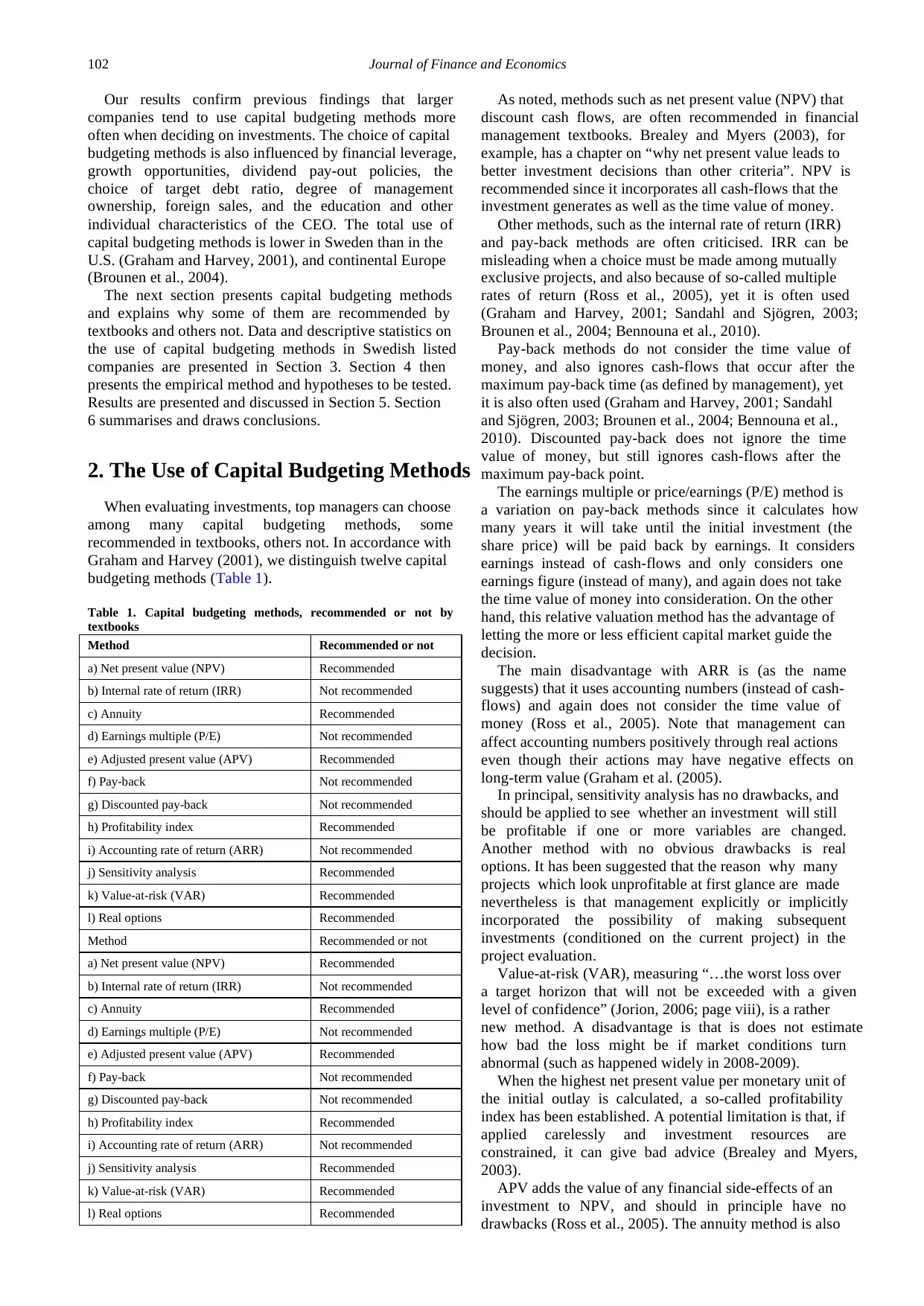

Figure 1 compares the total use of capital budgeting

methods by listed Swedish companies (287%) to U.S.

results (413%, Graham and Harvey, 2001) and continental

European results (308-388%, Brounen et. al, 2004). Total

use was calculated as the sum of column 3 on Table 2, and

was thus much lower in Sweden compared to the U.S. and

continental Europe.

The differences between Sweden and the U.S. or

continental Europe are surprising since our data only is

from listed companies, which should mean more use of

capital budgeting methods (since listed companies are

presumably more sophisticated, gathering more

information before making investments).

Figure 1. The total stated use of capital budgeting techniques in Swedish

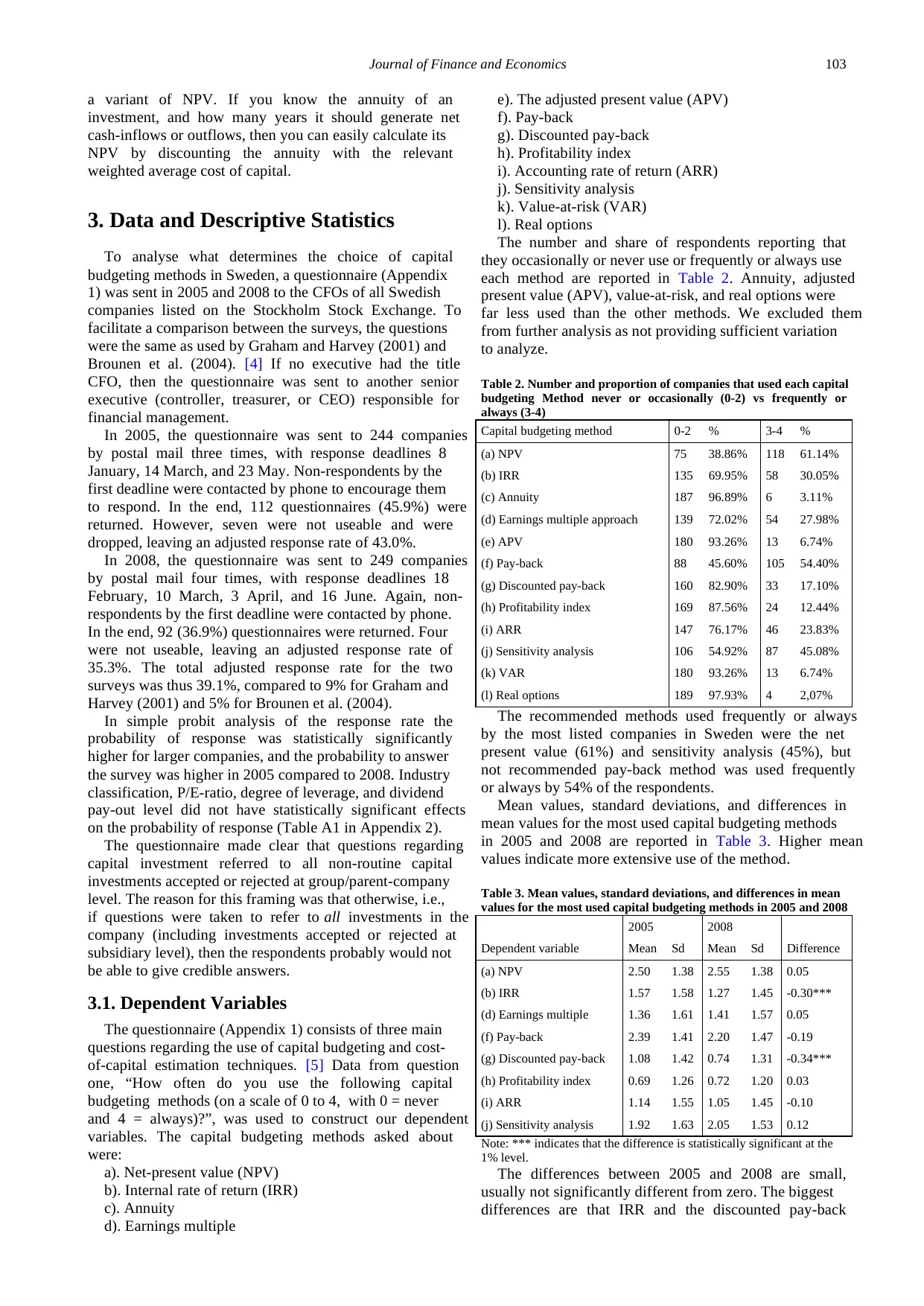

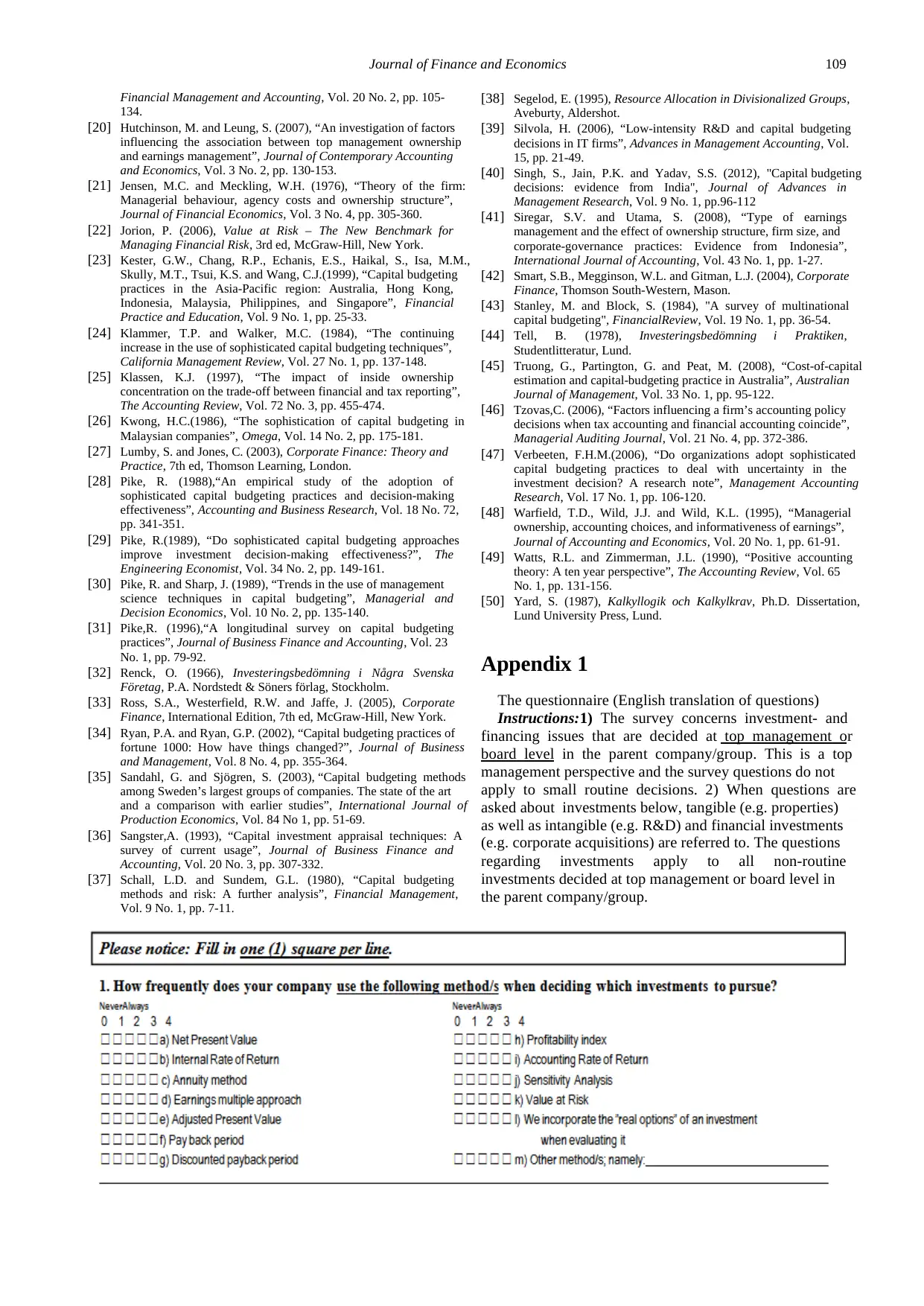

Figure 2 compares use of each method across countries.

A recommended method that is very uncommon in

Sweden compared to the U.S. and continental Europe is

incorporation of real options. But other recommended

methods such as NPV and sensitivity analysis were used

more frequently by Swedish listed companies than by

most continental European ones.

Figure 2. The stated use of different capital budgeting techniques in Swedish companies compared to companies in the US and continental Europe

3.2. Independent variables

We use information on company size, company

leverage, growth opportunities, dividend payout levels,

industry classification (manufacturing or not), target debt

ratio, proportion of foreign sales, proportion of shares

owned by the management, changes over time (a year

dummy), as well as the age, educational attainment and

the tenure of the CEO to analyze which variables

influence the reported use of capital budgeting methods.

Definitions, means, and standard deviations are presented

in Table 4. The variables included are further discussed in

Section 4.

Data on target debt-ratio, proportion of foreign sales,

proportion of shares owned by management, and

characteristics of the CEO are obtained from the

questionnaire, while data on company size, growth

opportunities, leverage, industry classification, and

dividend payments come from Datastream. [6] Data was

intentionally obtained from Datastream for 2004 and 2007

to prevent a possible endogeneity problem, since previous

year's values are predetermined.

(both not recommended) were less used in 2008 than in

2005.

Figure 1 compares the total use of capital budgeting

methods by listed Swedish companies (287%) to U.S.

results (413%, Graham and Harvey, 2001) and continental

European results (308-388%, Brounen et. al, 2004). Total

use was calculated as the sum of column 3 on Table 2, and

was thus much lower in Sweden compared to the U.S. and

continental Europe.

The differences between Sweden and the U.S. or

continental Europe are surprising since our data only is

from listed companies, which should mean more use of

capital budgeting methods (since listed companies are

presumably more sophisticated, gathering more

information before making investments).

Figure 1. The total stated use of capital budgeting techniques in Swedish

Figure 2 compares use of each method across countries.

A recommended method that is very uncommon in

Sweden compared to the U.S. and continental Europe is

incorporation of real options. But other recommended

methods such as NPV and sensitivity analysis were used

more frequently by Swedish listed companies than by

most continental European ones.

Figure 2. The stated use of different capital budgeting techniques in Swedish companies compared to companies in the US and continental Europe

3.2. Independent variables

We use information on company size, company

leverage, growth opportunities, dividend payout levels,

industry classification (manufacturing or not), target debt

ratio, proportion of foreign sales, proportion of shares

owned by the management, changes over time (a year

dummy), as well as the age, educational attainment and

the tenure of the CEO to analyze which variables

influence the reported use of capital budgeting methods.

Definitions, means, and standard deviations are presented

in Table 4. The variables included are further discussed in

Section 4.

Data on target debt-ratio, proportion of foreign sales,

proportion of shares owned by management, and

characteristics of the CEO are obtained from the

questionnaire, while data on company size, growth

opportunities, leverage, industry classification, and

dividend payments come from Datastream. [6] Data was

intentionally obtained from Datastream for 2004 and 2007

to prevent a possible endogeneity problem, since previous

year's values are predetermined.

Journal of Finance and Economics 105

Company size is approximated by revenues adjusted for

inflation using the Swedish Consumer Price Index

published by Statistics Sweden. Growth opportunities are

proxied by the price-earnings (P/E) ratio because high

P/E-ratios are thought to mean that the capital market

expects the company to have high future growth, and

leverage is measured by the debt-to-asset ratio. Even

though it may be the CFO who chooses the capital

budgeting method, questions regarding the CEO were

asked since the CFO is seen as the CEO’s agent.

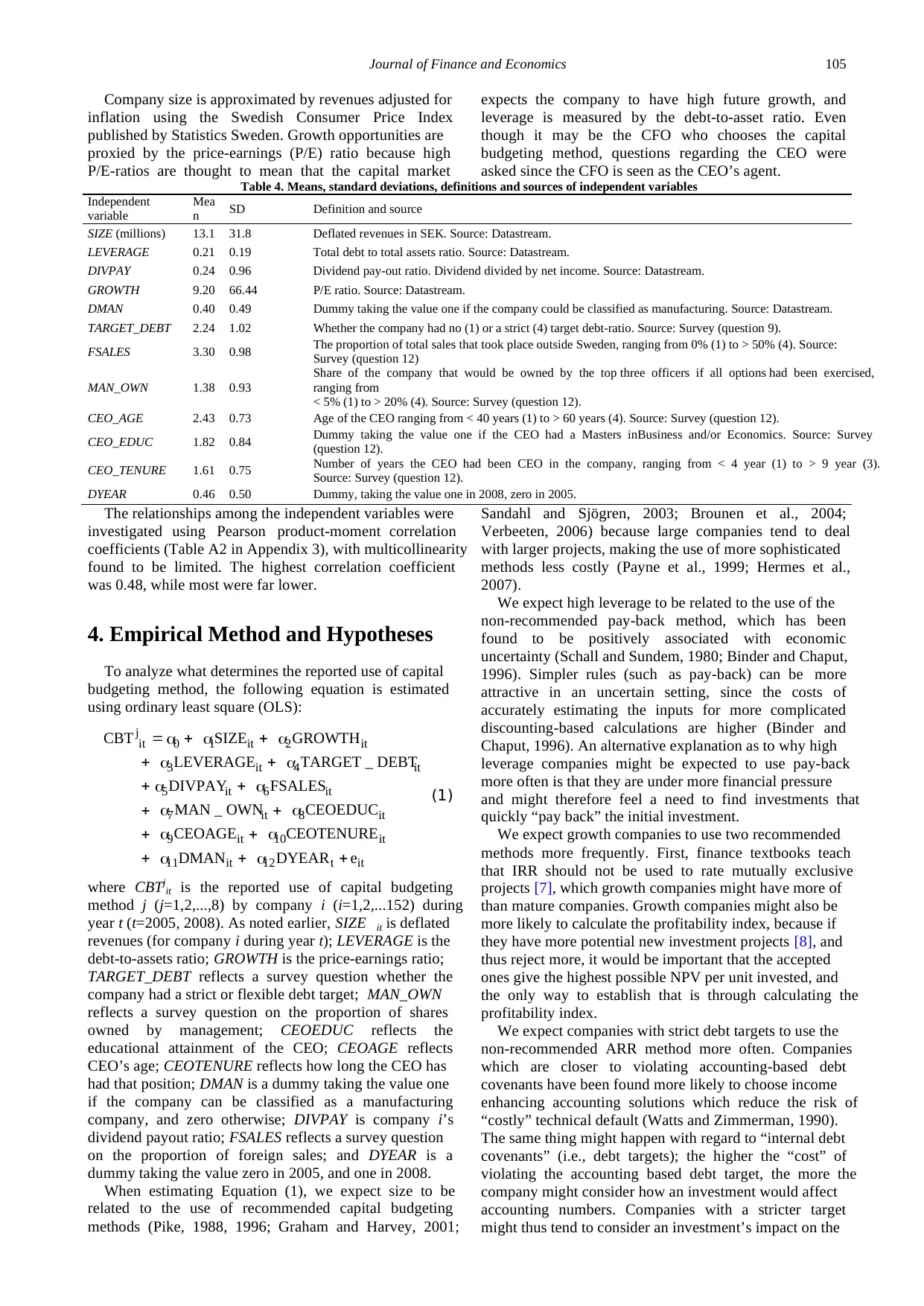

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, definitions and sources of independent variables

Independent

variable

Mea

n SD Definition and source

SIZE (millions) 13.1 31.8 Deflated revenues in SEK. Source: Datastream.

LEVERAGE 0.21 0.19 Total debt to total assets ratio. Source: Datastream.

DIVPAY 0.24 0.96 Dividend pay-out ratio. Dividend divided by net income. Source: Datastream.

GROWTH 9.20 66.44 P/E ratio. Source: Datastream.

DMAN 0.40 0.49 Dummy taking the value one if the company could be classified as manufacturing. Source: Datastream.

TARGET_DEBT 2.24 1.02 Whether the company had no (1) or a strict (4) target debt-ratio. Source: Survey (question 9).

FSALES 3.30 0.98 The proportion of total sales that took place outside Sweden, ranging from 0% (1) to > 50% (4). Source:

Survey (question 12)

MAN_OWN 1.38 0.93

Share of the company that would be owned by the top three officers if all options had been exercised,

ranging from

< 5% (1) to > 20% (4). Source: Survey (question 12).

CEO_AGE 2.43 0.73 Age of the CEO ranging from < 40 years (1) to > 60 years (4). Source: Survey (question 12).

CEO_EDUC 1.82 0.84 Dummy taking the value one if the CEO had a Masters inBusiness and/or Economics. Source: Survey

(question 12).

CEO_TENURE 1.61 0.75 Number of years the CEO had been CEO in the company, ranging from < 4 year (1) to > 9 year (3).

Source: Survey (question 12).

DYEAR 0.46 0.50 Dummy, taking the value one in 2008, zero in 2005.

The relationships among the independent variables were

investigated using Pearson product-moment correlation

coefficients (Table A2 in Appendix 3), with multicollinearity

found to be limited. The highest correlation coefficient

was 0.48, while most were far lower.

4. Empirical Method and Hypotheses

To analyze what determines the reported use of capital

budgeting method, the following equation is estimated

using ordinary least square (OLS):

jit 0 1 it 2 it

3 it 4 it

5 it 6 it

7 it 8 it

9 it 10 it

11 it 12 t it

CBT SIZE GROWTH

LEVERAGE TARGET _ DEBT

DIVPAY FSALES

MAN _ OWN CEOEDUC

CEOAGE CEOTENURE

DMAN DYEAR e

α α α

α α

α α

α α

α α

α α

= + +

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ + +

(1)

where CBTjit is the reported use of capital budgeting

method j (j=1,2,...,8) by company i (i=1,2,...152) during

year t (t=2005, 2008). As noted earlier, SIZE it is deflated

revenues (for company i during year t); LEVERAGE is the

debt-to-assets ratio; GROWTH is the price-earnings ratio;

TARGET_DEBT reflects a survey question whether the

company had a strict or flexible debt target; MAN_OWN

reflects a survey question on the proportion of shares

owned by management; CEOEDUC reflects the

educational attainment of the CEO; CEOAGE reflects

CEO’s age; CEOTENURE reflects how long the CEO has

had that position; DMAN is a dummy taking the value one

if the company can be classified as a manufacturing

company, and zero otherwise; DIVPAY is company i’s

dividend payout ratio; FSALES reflects a survey question

on the proportion of foreign sales; and DYEAR is a

dummy taking the value zero in 2005, and one in 2008.

When estimating Equation (1), we expect size to be

related to the use of recommended capital budgeting

methods (Pike, 1988, 1996; Graham and Harvey, 2001;

Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003; Brounen et al., 2004;

Verbeeten, 2006) because large companies tend to deal

with larger projects, making the use of more sophisticated

methods less costly (Payne et al., 1999; Hermes et al.,

2007).

We expect high leverage to be related to the use of the

non-recommended pay-back method, which has been

found to be positively associated with economic

uncertainty (Schall and Sundem, 1980; Binder and Chaput,

1996). Simpler rules (such as pay-back) can be more

attractive in an uncertain setting, since the costs of

accurately estimating the inputs for more complicated

discounting-based calculations are higher (Binder and

Chaput, 1996). An alternative explanation as to why high

leverage companies might be expected to use pay-back

more often is that they are under more financial pressure

and might therefore feel a need to find investments that

quickly “pay back” the initial investment.

We expect growth companies to use two recommended

methods more frequently. First, finance textbooks teach

that IRR should not be used to rate mutually exclusive

projects [7], which growth companies might have more of

than mature companies. Growth companies might also be

more likely to calculate the profitability index, because if

they have more potential new investment projects [8], and

thus reject more, it would be important that the accepted

ones give the highest possible NPV per unit invested, and

the only way to establish that is through calculating the

profitability index.

We expect companies with strict debt targets to use the

non-recommended ARR method more often. Companies

which are closer to violating accounting-based debt

covenants have been found more likely to choose income

enhancing accounting solutions which reduce the risk of

“costly” technical default (Watts and Zimmerman, 1990).

The same thing might happen with regard to “internal debt

covenants” (i.e., debt targets); the higher the “cost” of

violating the accounting based debt target, the more the

company might consider how an investment would affect

accounting numbers. Companies with a stricter target

might thus tend to consider an investment’s impact on the

Company size is approximated by revenues adjusted for

inflation using the Swedish Consumer Price Index

published by Statistics Sweden. Growth opportunities are

proxied by the price-earnings (P/E) ratio because high

P/E-ratios are thought to mean that the capital market

expects the company to have high future growth, and

leverage is measured by the debt-to-asset ratio. Even

though it may be the CFO who chooses the capital

budgeting method, questions regarding the CEO were

asked since the CFO is seen as the CEO’s agent.

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, definitions and sources of independent variables

Independent

variable

Mea

n SD Definition and source

SIZE (millions) 13.1 31.8 Deflated revenues in SEK. Source: Datastream.

LEVERAGE 0.21 0.19 Total debt to total assets ratio. Source: Datastream.

DIVPAY 0.24 0.96 Dividend pay-out ratio. Dividend divided by net income. Source: Datastream.

GROWTH 9.20 66.44 P/E ratio. Source: Datastream.

DMAN 0.40 0.49 Dummy taking the value one if the company could be classified as manufacturing. Source: Datastream.

TARGET_DEBT 2.24 1.02 Whether the company had no (1) or a strict (4) target debt-ratio. Source: Survey (question 9).

FSALES 3.30 0.98 The proportion of total sales that took place outside Sweden, ranging from 0% (1) to > 50% (4). Source:

Survey (question 12)

MAN_OWN 1.38 0.93

Share of the company that would be owned by the top three officers if all options had been exercised,

ranging from

< 5% (1) to > 20% (4). Source: Survey (question 12).

CEO_AGE 2.43 0.73 Age of the CEO ranging from < 40 years (1) to > 60 years (4). Source: Survey (question 12).

CEO_EDUC 1.82 0.84 Dummy taking the value one if the CEO had a Masters inBusiness and/or Economics. Source: Survey

(question 12).

CEO_TENURE 1.61 0.75 Number of years the CEO had been CEO in the company, ranging from < 4 year (1) to > 9 year (3).

Source: Survey (question 12).

DYEAR 0.46 0.50 Dummy, taking the value one in 2008, zero in 2005.

The relationships among the independent variables were

investigated using Pearson product-moment correlation

coefficients (Table A2 in Appendix 3), with multicollinearity

found to be limited. The highest correlation coefficient

was 0.48, while most were far lower.

4. Empirical Method and Hypotheses

To analyze what determines the reported use of capital

budgeting method, the following equation is estimated

using ordinary least square (OLS):

jit 0 1 it 2 it

3 it 4 it

5 it 6 it

7 it 8 it

9 it 10 it

11 it 12 t it

CBT SIZE GROWTH

LEVERAGE TARGET _ DEBT

DIVPAY FSALES

MAN _ OWN CEOEDUC

CEOAGE CEOTENURE

DMAN DYEAR e

α α α

α α

α α

α α

α α

α α

= + +

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ + +

(1)

where CBTjit is the reported use of capital budgeting

method j (j=1,2,...,8) by company i (i=1,2,...152) during

year t (t=2005, 2008). As noted earlier, SIZE it is deflated

revenues (for company i during year t); LEVERAGE is the

debt-to-assets ratio; GROWTH is the price-earnings ratio;

TARGET_DEBT reflects a survey question whether the

company had a strict or flexible debt target; MAN_OWN

reflects a survey question on the proportion of shares

owned by management; CEOEDUC reflects the

educational attainment of the CEO; CEOAGE reflects

CEO’s age; CEOTENURE reflects how long the CEO has

had that position; DMAN is a dummy taking the value one

if the company can be classified as a manufacturing

company, and zero otherwise; DIVPAY is company i’s

dividend payout ratio; FSALES reflects a survey question

on the proportion of foreign sales; and DYEAR is a

dummy taking the value zero in 2005, and one in 2008.

When estimating Equation (1), we expect size to be

related to the use of recommended capital budgeting

methods (Pike, 1988, 1996; Graham and Harvey, 2001;

Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003; Brounen et al., 2004;

Verbeeten, 2006) because large companies tend to deal

with larger projects, making the use of more sophisticated

methods less costly (Payne et al., 1999; Hermes et al.,

2007).

We expect high leverage to be related to the use of the

non-recommended pay-back method, which has been

found to be positively associated with economic

uncertainty (Schall and Sundem, 1980; Binder and Chaput,

1996). Simpler rules (such as pay-back) can be more

attractive in an uncertain setting, since the costs of

accurately estimating the inputs for more complicated

discounting-based calculations are higher (Binder and

Chaput, 1996). An alternative explanation as to why high

leverage companies might be expected to use pay-back

more often is that they are under more financial pressure

and might therefore feel a need to find investments that

quickly “pay back” the initial investment.

We expect growth companies to use two recommended

methods more frequently. First, finance textbooks teach

that IRR should not be used to rate mutually exclusive

projects [7], which growth companies might have more of

than mature companies. Growth companies might also be

more likely to calculate the profitability index, because if

they have more potential new investment projects [8], and

thus reject more, it would be important that the accepted

ones give the highest possible NPV per unit invested, and

the only way to establish that is through calculating the

profitability index.

We expect companies with strict debt targets to use the

non-recommended ARR method more often. Companies

which are closer to violating accounting-based debt

covenants have been found more likely to choose income

enhancing accounting solutions which reduce the risk of

“costly” technical default (Watts and Zimmerman, 1990).

The same thing might happen with regard to “internal debt

covenants” (i.e., debt targets); the higher the “cost” of

violating the accounting based debt target, the more the

company might consider how an investment would affect

accounting numbers. Companies with a stricter target

might thus tend to consider an investment’s impact on the

106 Journal of Finance and Economics

accounting debt-ratio to a higher extent (so that the target

debt-ratio is not “violated”). The accounting rate of return

indicates how an investment is expected to affect the debt

ratio, and could therefore be employed more extensively

in strict debt-target companies.

We expect companies with greater management

ownership to use recommended methods more often.

Ownership structure can have an impact on managerial

decisions and company performance (Warfield et al., 1995;

Klassen, 1997), and companies with greater managerial

ownership have been found to be less likely to experience

financial distress (Donker et al., 2009), perhaps because

managers then have more to lose if the company goes

bankrupt. Management ownership may thus reduce

management opportunism and increase use of

recommended capital budgeting methods.

On the other hand, with greater separation of ownership

(principals) and management (agents) incentives can arise

for managers to pursue non-value maximising behaviour

(Jensen and Meckling, 1976). To remedy this, contracts

often stipulate that management’s remuneration should be

based on accounting numbers. Top managers’ discretion

over both business activities and accounting choices

makes it possible for them to manage earnings upwards, to

maximise their own bonus payments (Healy, 1985).

Managers can thus take either accounting actions or

realactions to manage earnings or other accounting

figures (Dechow and Skinner, 2000). [9] Managers

focused on meeting accounting figures might reject a

profitable investment (with positive NPV) if the calculated

accounting rate of return is too low. [10] Graham et al.

(2005) showed that top management was willing to

sacrifice long-term value just to meet accounting targets.

[11] We believe that this focus on accounting numbers is

more profound in companies with low levels of

management ownership, and we therefore expect that

management owned companies use ARR less frequent.

We expect more educated and younger CEOs to use

recommended methods (Hermes et al., 2007), with which

they might be more familiar and to which they might be

more open. We also expect new CEOs to use more

“socially acceptable” (often recommended methods),

whereas CEOs with more company-specific experience

might be more relaxed and choose simpler methods,

perhaps viewing them as “good enough”. But more

experienced CEOs might choose more recommended

methods if taught their value by experience.

There might also be industry-specific differences when

it comes to the use of methods. We expect manufacturing

companies to use more recommended methods because

they are often larger, more capital intensive with higher

sunk costs.

We expect that companies with a higher dividend

payout ratio use profitability index calculations methods

less often because (apart from expectations about future

positive cash flows and profits) a higher dividend payout

indicates that the company is liquid, making capital

rationing less likely.

We expect a positive relation between foreign sales,

presumably reflecting a higher proportion of foreign

investments, with attendent currency and political risks,

and use of sensitivity analysis. Moreover, we expect that

foreign sales is positively associated with the pay-back

method. [12] Holmén and Pramborg (2009) documented

that the use of the payback method increases with political

risk. The suggested reason for the observed positive

relation (between political risk and the pay-back method)

is that political risk is difficult to estimate (i.e. rendering

high deliberation costs).

Finally, we expect more use of recommended methods

in 2008 than in 2005, because the use of capital budgeting

methods has become more sophisticated over time

(Klammer and Walker, 1984; Pike, 1996; Ryan and Ryan,

2002; Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003;Singh et al., 2012;

Bennouna et al., 2010).

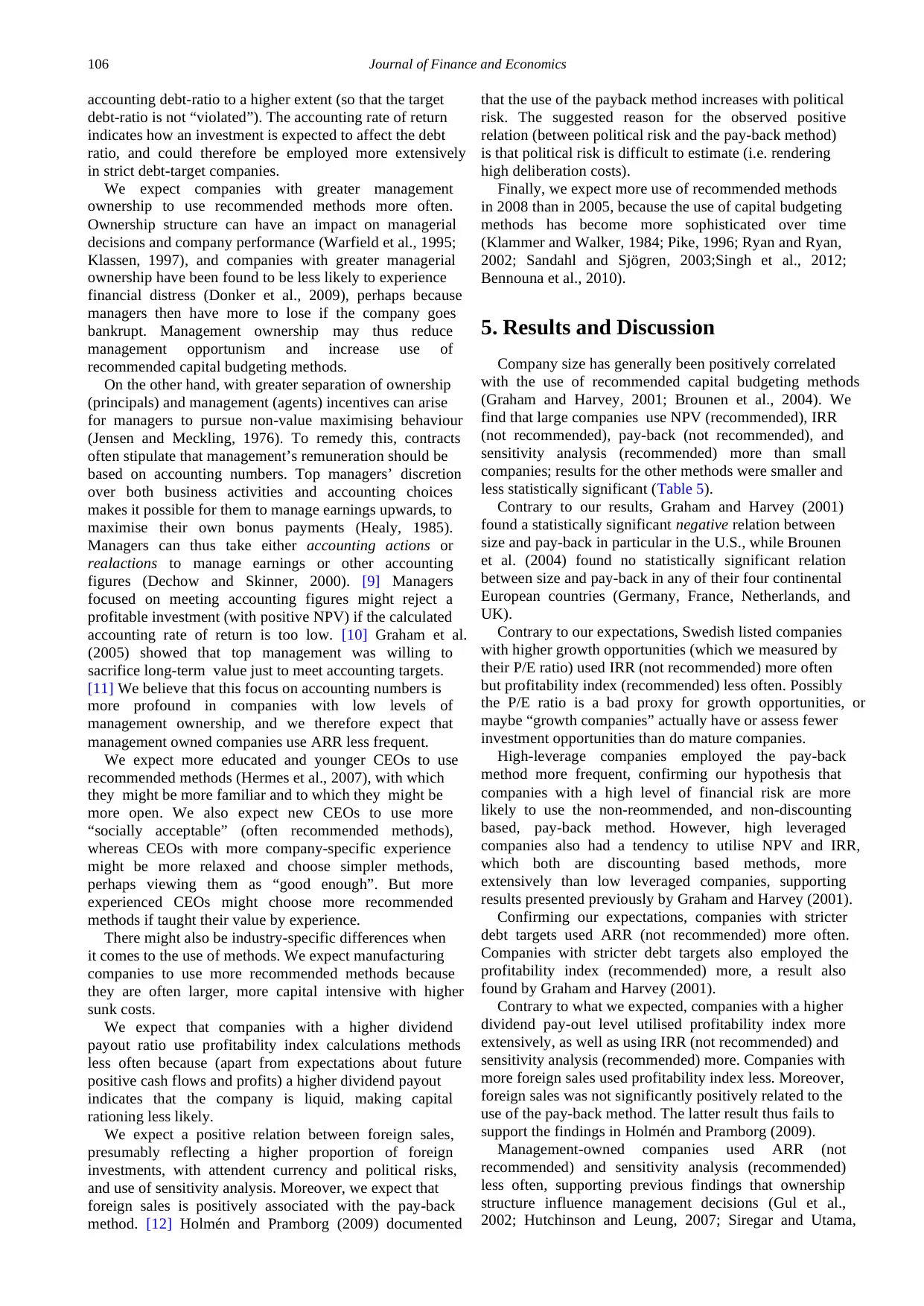

5. Results and Discussion

Company size has generally been positively correlated

with the use of recommended capital budgeting methods

(Graham and Harvey, 2001; Brounen et al., 2004). We

find that large companies use NPV (recommended), IRR

(not recommended), pay-back (not recommended), and

sensitivity analysis (recommended) more than small

companies; results for the other methods were smaller and

less statistically significant (Table 5).

Contrary to our results, Graham and Harvey (2001)

found a statistically significant negative relation between

size and pay-back in particular in the U.S., while Brounen

et al. (2004) found no statistically significant relation

between size and pay-back in any of their four continental

European countries (Germany, France, Netherlands, and

UK).

Contrary to our expectations, Swedish listed companies

with higher growth opportunities (which we measured by

their P/E ratio) used IRR (not recommended) more often

but profitability index (recommended) less often. Possibly

the P/E ratio is a bad proxy for growth opportunities, or

maybe “growth companies” actually have or assess fewer

investment opportunities than do mature companies.

High-leverage companies employed the pay-back

method more frequent, confirming our hypothesis that

companies with a high level of financial risk are more

likely to use the non-reommended, and non-discounting

based, pay-back method. However, high leveraged

companies also had a tendency to utilise NPV and IRR,

which both are discounting based methods, more

extensively than low leveraged companies, supporting

results presented previously by Graham and Harvey (2001).

Confirming our expectations, companies with stricter

debt targets used ARR (not recommended) more often.

Companies with stricter debt targets also employed the

profitability index (recommended) more, a result also

found by Graham and Harvey (2001).

Contrary to what we expected, companies with a higher

dividend pay-out level utilised profitability index more

extensively, as well as using IRR (not recommended) and

sensitivity analysis (recommended) more. Companies with

more foreign sales used profitability index less. Moreover,

foreign sales was not significantly positively related to the

use of the pay-back method. The latter result thus fails to

support the findings in Holmén and Pramborg (2009).

Management-owned companies used ARR (not

recommended) and sensitivity analysis (recommended)

less often, supporting previous findings that ownership

structure influence management decisions (Gul et al.,

2002; Hutchinson and Leung, 2007; Siregar and Utama,

accounting debt-ratio to a higher extent (so that the target

debt-ratio is not “violated”). The accounting rate of return

indicates how an investment is expected to affect the debt

ratio, and could therefore be employed more extensively

in strict debt-target companies.

We expect companies with greater management

ownership to use recommended methods more often.

Ownership structure can have an impact on managerial

decisions and company performance (Warfield et al., 1995;

Klassen, 1997), and companies with greater managerial

ownership have been found to be less likely to experience

financial distress (Donker et al., 2009), perhaps because

managers then have more to lose if the company goes

bankrupt. Management ownership may thus reduce

management opportunism and increase use of

recommended capital budgeting methods.

On the other hand, with greater separation of ownership

(principals) and management (agents) incentives can arise

for managers to pursue non-value maximising behaviour

(Jensen and Meckling, 1976). To remedy this, contracts

often stipulate that management’s remuneration should be

based on accounting numbers. Top managers’ discretion

over both business activities and accounting choices

makes it possible for them to manage earnings upwards, to

maximise their own bonus payments (Healy, 1985).

Managers can thus take either accounting actions or

realactions to manage earnings or other accounting

figures (Dechow and Skinner, 2000). [9] Managers

focused on meeting accounting figures might reject a

profitable investment (with positive NPV) if the calculated

accounting rate of return is too low. [10] Graham et al.

(2005) showed that top management was willing to

sacrifice long-term value just to meet accounting targets.

[11] We believe that this focus on accounting numbers is

more profound in companies with low levels of

management ownership, and we therefore expect that

management owned companies use ARR less frequent.

We expect more educated and younger CEOs to use

recommended methods (Hermes et al., 2007), with which

they might be more familiar and to which they might be

more open. We also expect new CEOs to use more

“socially acceptable” (often recommended methods),

whereas CEOs with more company-specific experience

might be more relaxed and choose simpler methods,

perhaps viewing them as “good enough”. But more

experienced CEOs might choose more recommended

methods if taught their value by experience.

There might also be industry-specific differences when

it comes to the use of methods. We expect manufacturing

companies to use more recommended methods because

they are often larger, more capital intensive with higher

sunk costs.

We expect that companies with a higher dividend

payout ratio use profitability index calculations methods

less often because (apart from expectations about future

positive cash flows and profits) a higher dividend payout

indicates that the company is liquid, making capital

rationing less likely.

We expect a positive relation between foreign sales,

presumably reflecting a higher proportion of foreign

investments, with attendent currency and political risks,

and use of sensitivity analysis. Moreover, we expect that

foreign sales is positively associated with the pay-back

method. [12] Holmén and Pramborg (2009) documented

that the use of the payback method increases with political

risk. The suggested reason for the observed positive

relation (between political risk and the pay-back method)

is that political risk is difficult to estimate (i.e. rendering

high deliberation costs).

Finally, we expect more use of recommended methods

in 2008 than in 2005, because the use of capital budgeting

methods has become more sophisticated over time

(Klammer and Walker, 1984; Pike, 1996; Ryan and Ryan,

2002; Sandahl and Sjögren, 2003;Singh et al., 2012;

Bennouna et al., 2010).

5. Results and Discussion

Company size has generally been positively correlated

with the use of recommended capital budgeting methods

(Graham and Harvey, 2001; Brounen et al., 2004). We

find that large companies use NPV (recommended), IRR

(not recommended), pay-back (not recommended), and

sensitivity analysis (recommended) more than small

companies; results for the other methods were smaller and

less statistically significant (Table 5).

Contrary to our results, Graham and Harvey (2001)

found a statistically significant negative relation between

size and pay-back in particular in the U.S., while Brounen

et al. (2004) found no statistically significant relation

between size and pay-back in any of their four continental

European countries (Germany, France, Netherlands, and

UK).

Contrary to our expectations, Swedish listed companies

with higher growth opportunities (which we measured by

their P/E ratio) used IRR (not recommended) more often

but profitability index (recommended) less often. Possibly

the P/E ratio is a bad proxy for growth opportunities, or

maybe “growth companies” actually have or assess fewer

investment opportunities than do mature companies.

High-leverage companies employed the pay-back

method more frequent, confirming our hypothesis that

companies with a high level of financial risk are more

likely to use the non-reommended, and non-discounting

based, pay-back method. However, high leveraged

companies also had a tendency to utilise NPV and IRR,

which both are discounting based methods, more

extensively than low leveraged companies, supporting

results presented previously by Graham and Harvey (2001).

Confirming our expectations, companies with stricter

debt targets used ARR (not recommended) more often.

Companies with stricter debt targets also employed the

profitability index (recommended) more, a result also

found by Graham and Harvey (2001).

Contrary to what we expected, companies with a higher

dividend pay-out level utilised profitability index more

extensively, as well as using IRR (not recommended) and

sensitivity analysis (recommended) more. Companies with

more foreign sales used profitability index less. Moreover,

foreign sales was not significantly positively related to the

use of the pay-back method. The latter result thus fails to

support the findings in Holmén and Pramborg (2009).

Management-owned companies used ARR (not

recommended) and sensitivity analysis (recommended)

less often, supporting previous findings that ownership

structure influence management decisions (Gul et al.,

2002; Hutchinson and Leung, 2007; Siregar and Utama,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Journal of Finance and Economics 107

2008). Management-owned companies might use ARR

because of greater goal-congruence between agent and

principal, with owners more interested in the economic

than accounting returns of an investment. There may also

be other (preferred) communicative and monitoring tools

than formal accounting numbers in companies with high

management (Eng and Mak, 2003), making an investment’s

impact on accounting rate of return not as important.

Table 5. Estimation results

Variable (a) NPV (b) IRR (d) EM (f) PB (g) DPB (h) PI (i) ARR (j) SA

SIZE Coef. 0,00598** 0,00975*** 0,00261 0,00623* 0,00131 -0,00146 -0,00172 0,00742**

t-value 2.28 2.72 0.85 1.94 0.38 -0.75 -0.46 2.61

GROWTH Coef. 0,0033 0,0034** -0,0004 0,0010 0,0015 -0,0021*** 0,0016 0,0022

t-value 1.64 2.00 -0.27 1.06 1.12 -2.76 1.59 1.28

LEVERAGE Coef. 1,15* 1,52** -0,34 1,37** 0,59 -0,11 0,45 0,34

t-value 1.78 2.32 -0.48 2.16 0.89 -0.17 0.61 0.49

TARGET_DEBT Coef. 0,02 0,13 0,00 0,12 -0,06 0,16* 0,30** 0,11

t-value 0.17 1.12 0.04 1.06 -0.60 1.69 2.45 0.89

DIVPAY Coef. -0,12 -0,35*** -0,04 -0,01 -0,19 0,13* 0,05 -0,20*

t-value -1.13 -3.40 -0.24 -0.15 -1.08 1.73 0.41 -1.88

FSALES Coef. 0,06 0,06 -0,05 0,18 0,30 -0,27** -0,09 0,20

t-value 0.54 0.49 -0.32 1.41 0.28 -2.16 -0.70 1.41

MAN_OWN Coef. -0,03 -0,04 -0,24 -0,06 -0,11 0,03 -0,26** -0,33**

t-value -0.18 -0.25 -1.59 -0.45 -0.76 0.30 -2.16 -2.04

CEO_EDUC Coef. 0,01 0,36** 0,22 0,17 0,29** -0,09 0,17 0,25

t-value 0.08 2.34 1.28 1.04 2.14 -0.46 1.09 1.42

CEO_AGE Coef. -0,04 -0,04 -0,13 -0,13 0,11 -0,05 0,34* -0,32*

t-value -0.22 -0.22 -0.63 -0.79 0.67 -0.32 1.95 -1.68

CEO_TENURE Coef. -0,07 0,25 0,05 0,11 0,08 -0,10 -0,13 0,33*

t-value -0.37 1.43 0.25 0.63 0.49 -0.72 -0.80 1.78

DMAN Coef. -0,18 0,25 -0,47* 0,14 0,25 -0,47** -0,13 -0,14

t-value -0.73 1.08 -1.69 0.59 1.11 -2.37 -0.59 -0.51

DYEAR Coef. -0,13 -0,82*** -0,31 -0,41 -0,64*** -0,05 -0,23 -0,33

t-value -0.54 -3.23 -1.08 -1.55 -2.77 -0.24 -0.91 -1.18

CONSTANT Coef. 2,38*** 0,14 2,16** 1,154 0,32 1,88 0,28 1,52*

t-value 3.61 0.17 2.43 1.56 0.50 3.07 0.38 1.80

R2 0.08 0.19 0.08 0.10 0.08 0.15 0.15 0.12

The reduced use of sensitivity analysis (recommended)

by management-owned companies could be interpreted as

contradicting the argument that owner-managers would

tend to use more sophisticated methods. But it could also

be that non-owner managers estimate how sensitive ARR

(rather than, say NPV) is to changes in the assumptions

(thus not necessarily leading to increased shareholder

value). And it could be that non-owner managers make

ARR estimations “internally” (to see how the accounting

numbers are affected), but show NPV-based sensitivity

analyses to other executives/board members to legitimise

their investment choice (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975; Gray

et al., 1996).

As expected, older CEOs used the accounting rate of

return (not recommended) more often, but sensitivity

analysis (recommended) less. On the other hand, CEOs

with long tenure used sensitivity analysis more often.

Contrary to expectations, more educated CEOs used both

IRR (not recommended) and discounted pay-back (not

recommended) more. A positive association between CEO

education and use of IRR has also been found in the U.S.

(Graham and Harvey, 2001), and the Netherlands,

Germany and France, though not in the UK (Brounen et al.

2004).

Confirming our expectations, manufacturing companies

used earnings multiple approach (not recommended) less,

but also used profitability index (recommended) less,

contradicting our expectations. Finally, IRR (not

recommended) and discounted pay-back (not recommended)

were used less often in 2008 than in 2005. Thus, the use of

recommended methods may not have increased, but the use

of non-recommended methods seems to have decreased.

6. Summary and Conclusions

We analysed what determined the use of capital

budgeting methods in Swedish listed companies in 2005

and 2008. Data on the use of capital budgeting methods

were obtained from a survey sent out to all Swedish

companies listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. The

survey is a replica of that used by Graham and Harvey

(2001) and Brounen et al. (2004).

Previous studies have found size to be positively

correlated with the use of some capital budgeting methods.

However, most of these studies were based on descriptive

methods such as correlation analysis and independent

sample t-tests, which are not sufficient to establish

causality. Using multivariate regression analysis, we

found that large companies used net present value

(recommended), internal rate of return (not recommended),

pay-back (not recommended), and sensitivity analysis

(recommended) more than small companies.

Other company-specific variables that seemed to

influence the choice of method were growth opportunities

of the company, leverage, the dividend pay-out ratio,

target debt ratio, the degree of management ownership,

foreign sales, industry and individual characteristics of the

CEO. Our results supported hypotheses that Swedish

listed companies have become more sophisticated over the

years (or at least less unsophisticated); that companies

with greater leverage used payback more; and that

companies with stricter debt targets and less management

ownership employed ARR more.

Surprisingly, companies with more educated CEOs

used non-recommended methods such as IRR and

discounted pay-back more than others. Possibly it is the

characteristics of the CFO (not the CEO) that influence

the choice of capital budgeting methods, which is thus a

topic for further study.

2008). Management-owned companies might use ARR

because of greater goal-congruence between agent and

principal, with owners more interested in the economic

than accounting returns of an investment. There may also

be other (preferred) communicative and monitoring tools

than formal accounting numbers in companies with high

management (Eng and Mak, 2003), making an investment’s

impact on accounting rate of return not as important.

Table 5. Estimation results

Variable (a) NPV (b) IRR (d) EM (f) PB (g) DPB (h) PI (i) ARR (j) SA

SIZE Coef. 0,00598** 0,00975*** 0,00261 0,00623* 0,00131 -0,00146 -0,00172 0,00742**

t-value 2.28 2.72 0.85 1.94 0.38 -0.75 -0.46 2.61

GROWTH Coef. 0,0033 0,0034** -0,0004 0,0010 0,0015 -0,0021*** 0,0016 0,0022

t-value 1.64 2.00 -0.27 1.06 1.12 -2.76 1.59 1.28

LEVERAGE Coef. 1,15* 1,52** -0,34 1,37** 0,59 -0,11 0,45 0,34

t-value 1.78 2.32 -0.48 2.16 0.89 -0.17 0.61 0.49

TARGET_DEBT Coef. 0,02 0,13 0,00 0,12 -0,06 0,16* 0,30** 0,11

t-value 0.17 1.12 0.04 1.06 -0.60 1.69 2.45 0.89

DIVPAY Coef. -0,12 -0,35*** -0,04 -0,01 -0,19 0,13* 0,05 -0,20*

t-value -1.13 -3.40 -0.24 -0.15 -1.08 1.73 0.41 -1.88

FSALES Coef. 0,06 0,06 -0,05 0,18 0,30 -0,27** -0,09 0,20

t-value 0.54 0.49 -0.32 1.41 0.28 -2.16 -0.70 1.41

MAN_OWN Coef. -0,03 -0,04 -0,24 -0,06 -0,11 0,03 -0,26** -0,33**

t-value -0.18 -0.25 -1.59 -0.45 -0.76 0.30 -2.16 -2.04

CEO_EDUC Coef. 0,01 0,36** 0,22 0,17 0,29** -0,09 0,17 0,25

t-value 0.08 2.34 1.28 1.04 2.14 -0.46 1.09 1.42

CEO_AGE Coef. -0,04 -0,04 -0,13 -0,13 0,11 -0,05 0,34* -0,32*

t-value -0.22 -0.22 -0.63 -0.79 0.67 -0.32 1.95 -1.68

CEO_TENURE Coef. -0,07 0,25 0,05 0,11 0,08 -0,10 -0,13 0,33*

t-value -0.37 1.43 0.25 0.63 0.49 -0.72 -0.80 1.78

DMAN Coef. -0,18 0,25 -0,47* 0,14 0,25 -0,47** -0,13 -0,14