Corporate Accounting: Impairment Loss Calculation and Distribution

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|8

|1594

|123

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of impairment loss for cash-generating units within the context of corporate accounting and reporting, referencing AASB 136 standards. It discusses the principles of impairment, emphasizing that assets cannot be carried above their recoverable amount, defined as the higher of fair value less selling costs and value-in-use. The report details the process of identifying impairment indications, conducting annual impairment tests for assets like goodwill, and calculating recoverable amounts. It explains how impairment losses are distributed within cash-generating units, initially reducing goodwill and then other assets on a pro-rata basis, ensuring that carrying values are not reduced below certain thresholds like value-in-use or fair value less disposal costs. A practical example involving a damaged machine illustrates the application of these principles, highlighting scenarios where impairment loss is recognized versus when reassessment of depreciation is more appropriate. The report includes a numerical example demonstrating the calculation and allocation of impairment loss across different assets, including plant, trademark, vehicle, and goodwill, along with the corresponding journal entries. It concludes by emphasizing the importance of proper accounting for impairment losses in accordance with accounting standards.

CORPORATE

ACCOUNTING

AND

REPORTING

PRESENTED BY

TUONG VAN HO

11500083

ACCOUNTING

AND

REPORTING

PRESENTED BY

TUONG VAN HO

11500083

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PART A

Impairment loss for cash-generating units excluding goodwill:

One of the basic impairment principles is that it is not possible to bring forward an

asset above its recoverable amount on the statement of financial position, which is

higher of the fair asset value minus selling cost and value-in-use. Comparison is made

between the carrying and recoverable values of the asset and impairment takes place

when the former exceeds the latter (Bond, Govendir and Wells 2016). The asset is

allocated with impairment during that time with the impairment loss recognised in the

income statement.

Whenever any indication is identified for impairment, the related assets are

tested for review purpose. However, despite the absence of any indication, annual

impairment is conducted for some assets and they include goodwill and other assets

having no physical presence (André, Dionysiou and Tsalavoutas 2018). The

recoverable amount is calculated at the level of individual asset. However, the cash

flows of an asset are independent from those of other assets and most of the assets are

considered for impairment testing and they could be classified under cash-generating

units (Bragg 2017).

“Paragraph 104 of AASB 136” cites that it is necessary for the carrying amount

to be greater than the recoverable amount so that impairment loss could be recognised

for a cash-generating unit. The distribution of impairment loss is made to reduce the

carrying value of the asset of that unit in two chronological orders. Initially, there would

be reduction in goodwill value assigned to the cash-generating unit and secondly, the

Impairment loss for cash-generating units excluding goodwill:

One of the basic impairment principles is that it is not possible to bring forward an

asset above its recoverable amount on the statement of financial position, which is

higher of the fair asset value minus selling cost and value-in-use. Comparison is made

between the carrying and recoverable values of the asset and impairment takes place

when the former exceeds the latter (Bond, Govendir and Wells 2016). The asset is

allocated with impairment during that time with the impairment loss recognised in the

income statement.

Whenever any indication is identified for impairment, the related assets are

tested for review purpose. However, despite the absence of any indication, annual

impairment is conducted for some assets and they include goodwill and other assets

having no physical presence (André, Dionysiou and Tsalavoutas 2018). The

recoverable amount is calculated at the level of individual asset. However, the cash

flows of an asset are independent from those of other assets and most of the assets are

considered for impairment testing and they could be classified under cash-generating

units (Bragg 2017).

“Paragraph 104 of AASB 136” cites that it is necessary for the carrying amount

to be greater than the recoverable amount so that impairment loss could be recognised

for a cash-generating unit. The distribution of impairment loss is made to reduce the

carrying value of the asset of that unit in two chronological orders. Initially, there would

be reduction in goodwill value assigned to the cash-generating unit and secondly, the

other units of the asset in terms of pro-rata depending on the carrying amount of the

assets in the unit would be minimised.

Due to minimisation of carrying amounts, the treatment would be made in the

form of impairment loss on separate assets and recognition is to be made as per

“Paragraph 60 of AASB 136” (Aasb.gov.au 2018). Moreover, “Paragraph 105 of

AASB 136” denotes that the reduction of the carrying value must not be lower than the

highest of the three available alternatives in order to distribute impairment loss. The

alternatives are mainly value-in-use, fair value less disposal cost and zero.

The amount incurred for impairment loss that could have been distributed

distinctly to the asset requires distribution on pro-rata basis to the other units of the

asset. With reference to “Paragraph 106 of AASB 136”, the recoverable amount could

not be estimated every time for the individual asset of a cash-generating unit. Therefore,

this standard requires random distribution of impairment loss between the assets of the

unit, the only exception is goodwill. This is because there is collaboration among all

classes of assets in cash-generating unit; the only exception is goodwill (Hellman 2016).

In compliance with “Paragraph 107 of AASB 136”, if it is not possible to

ascertain the recoverable amount of a separate asset, there might be occurrence of two

distinct situations. Initially, the asset realises impairment loss, if the carrying value is

greater than the fair value less disposal cost and the results of the distribution

procedures mentioned under “Paragraphs 104 and 105 of AASB 136” (Lobo et al.

2017). Lastly, the asset recognises impairment loss, if no impairment is carried out on

assets in the unit would be minimised.

Due to minimisation of carrying amounts, the treatment would be made in the

form of impairment loss on separate assets and recognition is to be made as per

“Paragraph 60 of AASB 136” (Aasb.gov.au 2018). Moreover, “Paragraph 105 of

AASB 136” denotes that the reduction of the carrying value must not be lower than the

highest of the three available alternatives in order to distribute impairment loss. The

alternatives are mainly value-in-use, fair value less disposal cost and zero.

The amount incurred for impairment loss that could have been distributed

distinctly to the asset requires distribution on pro-rata basis to the other units of the

asset. With reference to “Paragraph 106 of AASB 136”, the recoverable amount could

not be estimated every time for the individual asset of a cash-generating unit. Therefore,

this standard requires random distribution of impairment loss between the assets of the

unit, the only exception is goodwill. This is because there is collaboration among all

classes of assets in cash-generating unit; the only exception is goodwill (Hellman 2016).

In compliance with “Paragraph 107 of AASB 136”, if it is not possible to

ascertain the recoverable amount of a separate asset, there might be occurrence of two

distinct situations. Initially, the asset realises impairment loss, if the carrying value is

greater than the fair value less disposal cost and the results of the distribution

procedures mentioned under “Paragraphs 104 and 105 of AASB 136” (Lobo et al.

2017). Lastly, the asset recognises impairment loss, if no impairment is carried out on

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

the related cash-generating unit. This is only possible if the carrying value of the asset is

lower than its fair value obtained after deducting disposal cost.

An example has been considered, in which a machine has suffered physical

damage; however, it could be used for production purpose, even though its

effectiveness is reduced at the current date. It has been identified that the carrying

value of the machine is lower compared to its fair value less cost of disposal related to

the machine. Furthermore, no independent cash flows are generated from the machine.

The lowest identifiable group of assets including the machine along with deriving cash

inflows that do not have any relationship with other asset groups, is the production line

of the machine. The impairment is not conducted wholly to this line, as indicated by the

machine’s recoverable amount.

In this situation, there might be two distinct assumptions. The initial assumption

states that the budgets or estimations approved on the part of the management imply

the absence of commitment level to substitute the machine. It is not possible to estimate

the recoverable amount of the machine, since the value-in-use of the machine might not

be identical with the fair value less cost of disposal. This could be determined for the

cash-generating unit of the machine (Paugam and Ramond 2015). Hence, impairment

loss is not recognised and it mandates the need for the organisation in reassessing the

depreciation period or the depreciation technique pertaining to the machine. In this

case, shorter depreciation period could be enforced on the part of the organisation or

adopt paid depreciation method. This would help in implying the leftover life of the

machine or the way where there is estimation regarding the consumption of economic

benefits.

lower than its fair value obtained after deducting disposal cost.

An example has been considered, in which a machine has suffered physical

damage; however, it could be used for production purpose, even though its

effectiveness is reduced at the current date. It has been identified that the carrying

value of the machine is lower compared to its fair value less cost of disposal related to

the machine. Furthermore, no independent cash flows are generated from the machine.

The lowest identifiable group of assets including the machine along with deriving cash

inflows that do not have any relationship with other asset groups, is the production line

of the machine. The impairment is not conducted wholly to this line, as indicated by the

machine’s recoverable amount.

In this situation, there might be two distinct assumptions. The initial assumption

states that the budgets or estimations approved on the part of the management imply

the absence of commitment level to substitute the machine. It is not possible to estimate

the recoverable amount of the machine, since the value-in-use of the machine might not

be identical with the fair value less cost of disposal. This could be determined for the

cash-generating unit of the machine (Paugam and Ramond 2015). Hence, impairment

loss is not recognised and it mandates the need for the organisation in reassessing the

depreciation period or the depreciation technique pertaining to the machine. In this

case, shorter depreciation period could be enforced on the part of the organisation or

adopt paid depreciation method. This would help in implying the leftover life of the

machine or the way where there is estimation regarding the consumption of economic

benefits.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Secondly, it is assumed that the budgets or estimations sanctioned on the part of

the management signify its commitment to substitute the machine by selling the same in

future. The cash flows generated from the continuous use of the machine are estimated

to be not much until it is disposed. This makes it difficult to determine the recoverable

amount of the machine. Therefore, no consideration is made to the cash-generating unit

where the machine belongs, more specifically, the production line. Since the fair value

obtained after deduction of the disposal cost of the machine is smaller compared to the

carrying value, the machine recognises impairment loss (Paugam and Ramond 2015).

From the above evaluation, it is clearly found that whenever an impairment loss

takes place in a cash-generating unit, the distribution of loss is made across all the

assets in the unit depending on pro-rata. However, this does not take into account the

value of goodwill. The loss is relative to the total carrying value of the cash-generating

unit of the organisation. Finally, the accounting losses are conducted in the similar

manner like those for the separate or distinct assets.

the management signify its commitment to substitute the machine by selling the same in

future. The cash flows generated from the continuous use of the machine are estimated

to be not much until it is disposed. This makes it difficult to determine the recoverable

amount of the machine. Therefore, no consideration is made to the cash-generating unit

where the machine belongs, more specifically, the production line. Since the fair value

obtained after deduction of the disposal cost of the machine is smaller compared to the

carrying value, the machine recognises impairment loss (Paugam and Ramond 2015).

From the above evaluation, it is clearly found that whenever an impairment loss

takes place in a cash-generating unit, the distribution of loss is made across all the

assets in the unit depending on pro-rata. However, this does not take into account the

value of goodwill. The loss is relative to the total carrying value of the cash-generating

unit of the organisation. Finally, the accounting losses are conducted in the similar

manner like those for the separate or distinct assets.

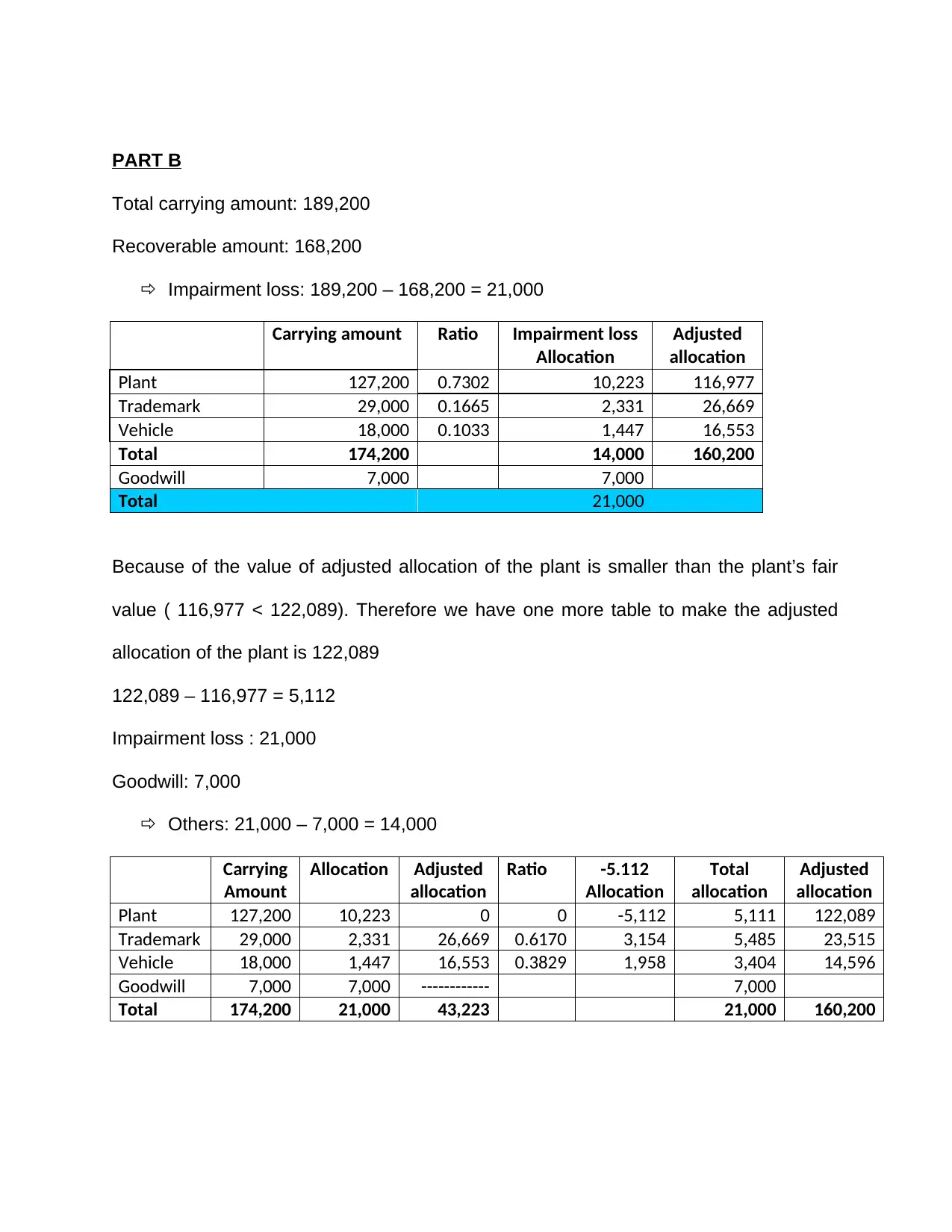

PART B

Total carrying amount: 189,200

Recoverable amount: 168,200

Impairment loss: 189,200 – 168,200 = 21,000

Carrying amount Ratio Impairment loss

Allocation

Adjusted

allocation

Plant 127,200 0.7302 10,223 116,977

Trademark 29,000 0.1665 2,331 26,669

Vehicle 18,000 0.1033 1,447 16,553

Total 174,200 14,000 160,200

Goodwill 7,000 7,000

Total 21,000

Because of the value of adjusted allocation of the plant is smaller than the plant’s fair

value ( 116,977 < 122,089). Therefore we have one more table to make the adjusted

allocation of the plant is 122,089

122,089 – 116,977 = 5,112

Impairment loss : 21,000

Goodwill: 7,000

Others: 21,000 – 7,000 = 14,000

Carrying

Amount

Allocation Adjusted

allocation

Ratio -5.112

Allocation

Total

allocation

Adjusted

allocation

Plant 127,200 10,223 0 0 -5,112 5,111 122,089

Trademark 29,000 2,331 26,669 0.6170 3,154 5,485 23,515

Vehicle 18,000 1,447 16,553 0.3829 1,958 3,404 14,596

Goodwill 7,000 7,000 ------------ 7,000

Total 174,200 21,000 43,223 21,000 160,200

Total carrying amount: 189,200

Recoverable amount: 168,200

Impairment loss: 189,200 – 168,200 = 21,000

Carrying amount Ratio Impairment loss

Allocation

Adjusted

allocation

Plant 127,200 0.7302 10,223 116,977

Trademark 29,000 0.1665 2,331 26,669

Vehicle 18,000 0.1033 1,447 16,553

Total 174,200 14,000 160,200

Goodwill 7,000 7,000

Total 21,000

Because of the value of adjusted allocation of the plant is smaller than the plant’s fair

value ( 116,977 < 122,089). Therefore we have one more table to make the adjusted

allocation of the plant is 122,089

122,089 – 116,977 = 5,112

Impairment loss : 21,000

Goodwill: 7,000

Others: 21,000 – 7,000 = 14,000

Carrying

Amount

Allocation Adjusted

allocation

Ratio -5.112

Allocation

Total

allocation

Adjusted

allocation

Plant 127,200 10,223 0 0 -5,112 5,111 122,089

Trademark 29,000 2,331 26,669 0.6170 3,154 5,485 23,515

Vehicle 18,000 1,447 16,553 0.3829 1,958 3,404 14,596

Goodwill 7,000 7,000 ------------ 7,000

Total 174,200 21,000 43,223 21,000 160,200

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

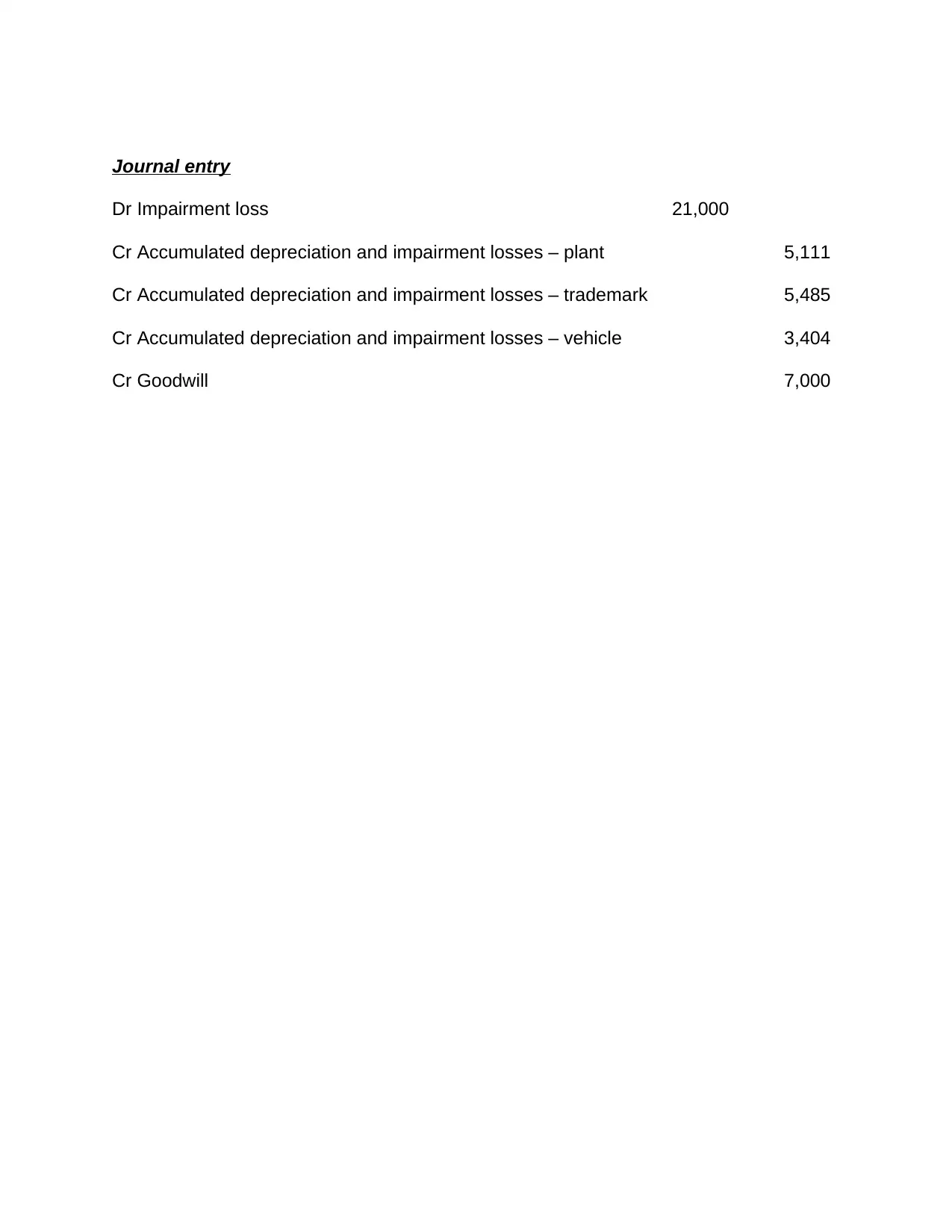

Journal entry

Dr Impairment loss 21,000

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – plant 5,111

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – trademark 5,485

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – vehicle 3,404

Cr Goodwill 7,000

Dr Impairment loss 21,000

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – plant 5,111

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – trademark 5,485

Cr Accumulated depreciation and impairment losses – vehicle 3,404

Cr Goodwill 7,000

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

References:

Aasb.gov.au., 2018. [online] Available at:

http://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content105/c9/AASB136_07-04_COMPjun09_01-

10.pdf [Accessed 18 May 2018].

André, P., Dionysiou, D. and Tsalavoutas, I., 2018. Mandated disclosures under IAS 36

Impairment of Assets and IAS 38 Intangible Assets: value relevance and impact on

analysts’ forecasts. Applied Economics, 50(7), pp.707-725.

Bond, D., Govendir, B. and Wells, P., 2016. An evaluation of asset impairment

decisions by Australian firms and whether this was impacted by AASB 136.

Bragg, S.M., 2017. Fixed Asset Accounting. AccountingTools LLC.

Hellman, N., 2016. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation. Journal

of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 27, pp.13-25.

Lobo, G.J., Paugam, L., Zhang, D. and Casta, J.F., 2017. The effect of joint auditor pair

composition on audit quality: Evidence from impairment tests. Contemporary

Accounting Research, 34(1), pp.118-153.

Paugam, L. and Ramond, O., 2015. Effect of Impairment‐Testing Disclosures on the

Cost of Equity Capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 42(5-6), pp.583-618.

Viana, L., Moreira, J.A. and Alves, P., 2017. Accounting for Public-Private

Partnerships. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and

Governance, pp.1-16.

Aasb.gov.au., 2018. [online] Available at:

http://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content105/c9/AASB136_07-04_COMPjun09_01-

10.pdf [Accessed 18 May 2018].

André, P., Dionysiou, D. and Tsalavoutas, I., 2018. Mandated disclosures under IAS 36

Impairment of Assets and IAS 38 Intangible Assets: value relevance and impact on

analysts’ forecasts. Applied Economics, 50(7), pp.707-725.

Bond, D., Govendir, B. and Wells, P., 2016. An evaluation of asset impairment

decisions by Australian firms and whether this was impacted by AASB 136.

Bragg, S.M., 2017. Fixed Asset Accounting. AccountingTools LLC.

Hellman, N., 2016. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation. Journal

of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 27, pp.13-25.

Lobo, G.J., Paugam, L., Zhang, D. and Casta, J.F., 2017. The effect of joint auditor pair

composition on audit quality: Evidence from impairment tests. Contemporary

Accounting Research, 34(1), pp.118-153.

Paugam, L. and Ramond, O., 2015. Effect of Impairment‐Testing Disclosures on the

Cost of Equity Capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 42(5-6), pp.583-618.

Viana, L., Moreira, J.A. and Alves, P., 2017. Accounting for Public-Private

Partnerships. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and

Governance, pp.1-16.

1 out of 8

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.