Initiatives for the Development of Tourism in Tropical Australia Report 2022

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/25

|57

|20782

|20

AI Summary

Critique & Comparison of Two Discussion Papers. WE NEED TO DISCUSS THE TWO DISCUSSION PAPER OF RELATED TO TOURISM. The topic can be tourism in Australia I HAVE ATTACHED MY MARKING RUBRIC I have attached the sample of the discussion paper but we cannot use this

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Initiatives for the

Development of Tourism in

Tropical Australia

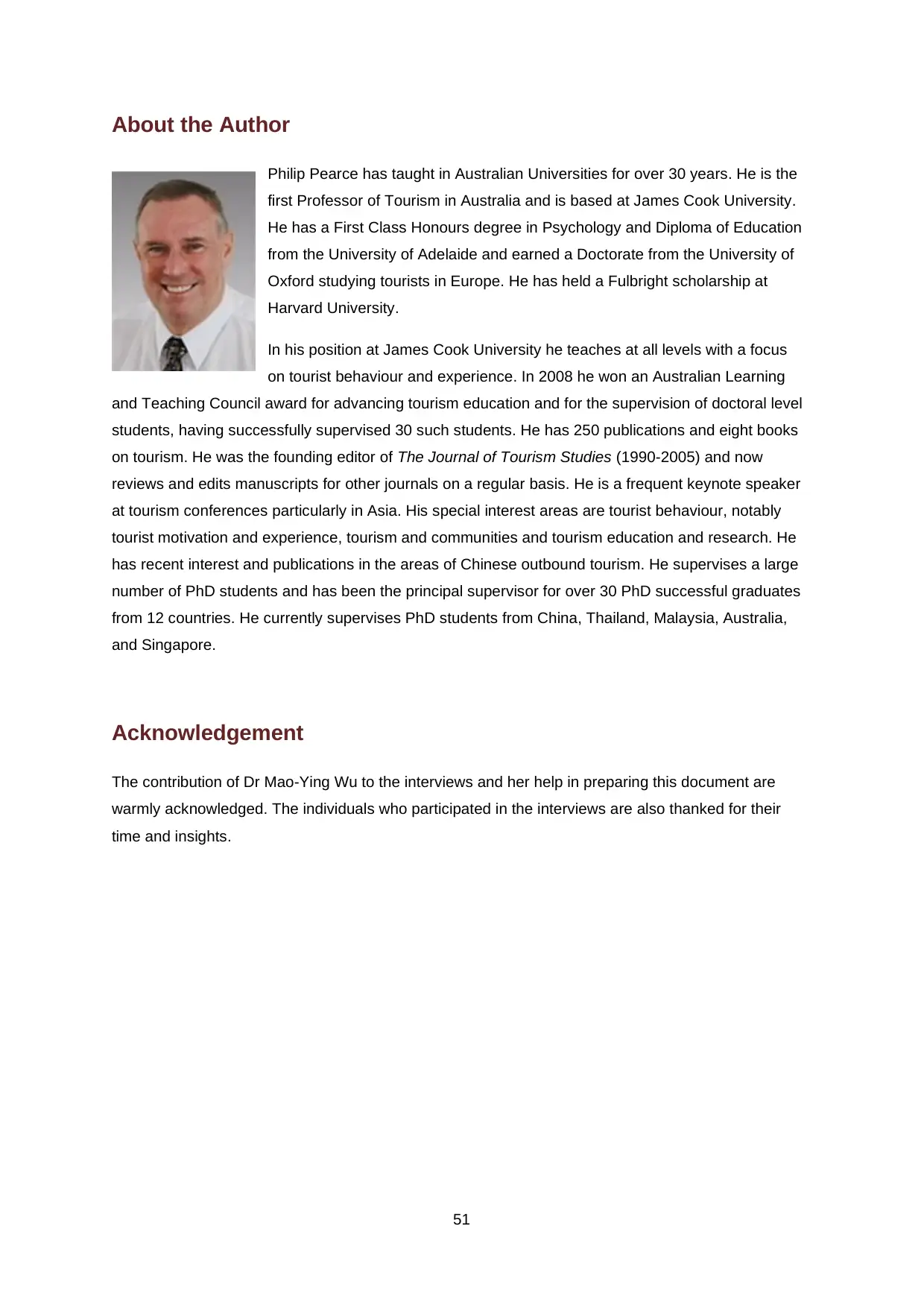

Dr Philip L. Pearce

Foundation Professor of Tourism

School of Business, James Cook University

Development of Tourism in

Tropical Australia

Dr Philip L. Pearce

Foundation Professor of Tourism

School of Business, James Cook University

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Published by The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns

Year of Publication: 2013

ISBN 978-0-99875922-3-1

This discussion paper is licenced under a Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to copy, communicate

and adapt this work, so long as you attribute James Cook University

[The Cairns Institute] and the author.

This report should be cited as: Pearce, P. L. (2013). Initiatives for the

development of tourism in tropical Australia. Cairns: James Cook

University.

This report is part of the Cairns Institute’s Future of Northern Australia

discussion paper series. It also contributes to the Northern Futures

Collaborative Research Network.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the

author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cairns Institute or

James Cook University.

This report is available for download from eprints.jcu.edu.au/29920/

October 2013

Year of Publication: 2013

ISBN 978-0-99875922-3-1

This discussion paper is licenced under a Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to copy, communicate

and adapt this work, so long as you attribute James Cook University

[The Cairns Institute] and the author.

This report should be cited as: Pearce, P. L. (2013). Initiatives for the

development of tourism in tropical Australia. Cairns: James Cook

University.

This report is part of the Cairns Institute’s Future of Northern Australia

discussion paper series. It also contributes to the Northern Futures

Collaborative Research Network.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the

author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cairns Institute or

James Cook University.

This report is available for download from eprints.jcu.edu.au/29920/

October 2013

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. i

Introduction.............................................................................................................................................. 1

An Organising Framework ...................................................................................................................... 1

1. Developing Tourism for Community Well-being.................................................................................. 5

2. Improving Cross-industry Opportunities .............................................................................................. 9

3. Reinforcing the Well Managed Natural Brand................................................................................... 12

4. Boosting Indigenous Opportunities ................................................................................................... 16

5. Incorporating the Slow Tourism Approach ........................................................................................ 20

6. Supporting the Domestic Backbone .................................................................................................. 23

7. Consolidating the International Strategies ........................................................................................ 27

8. Integrating Quality Markers ............................................................................................................... 32

9. Attending to Research Investment .................................................................................................... 35

10. Refreshing Educational, Extension and Career Structures ............................................................ 38

A Community Competition .................................................................................................................... 42

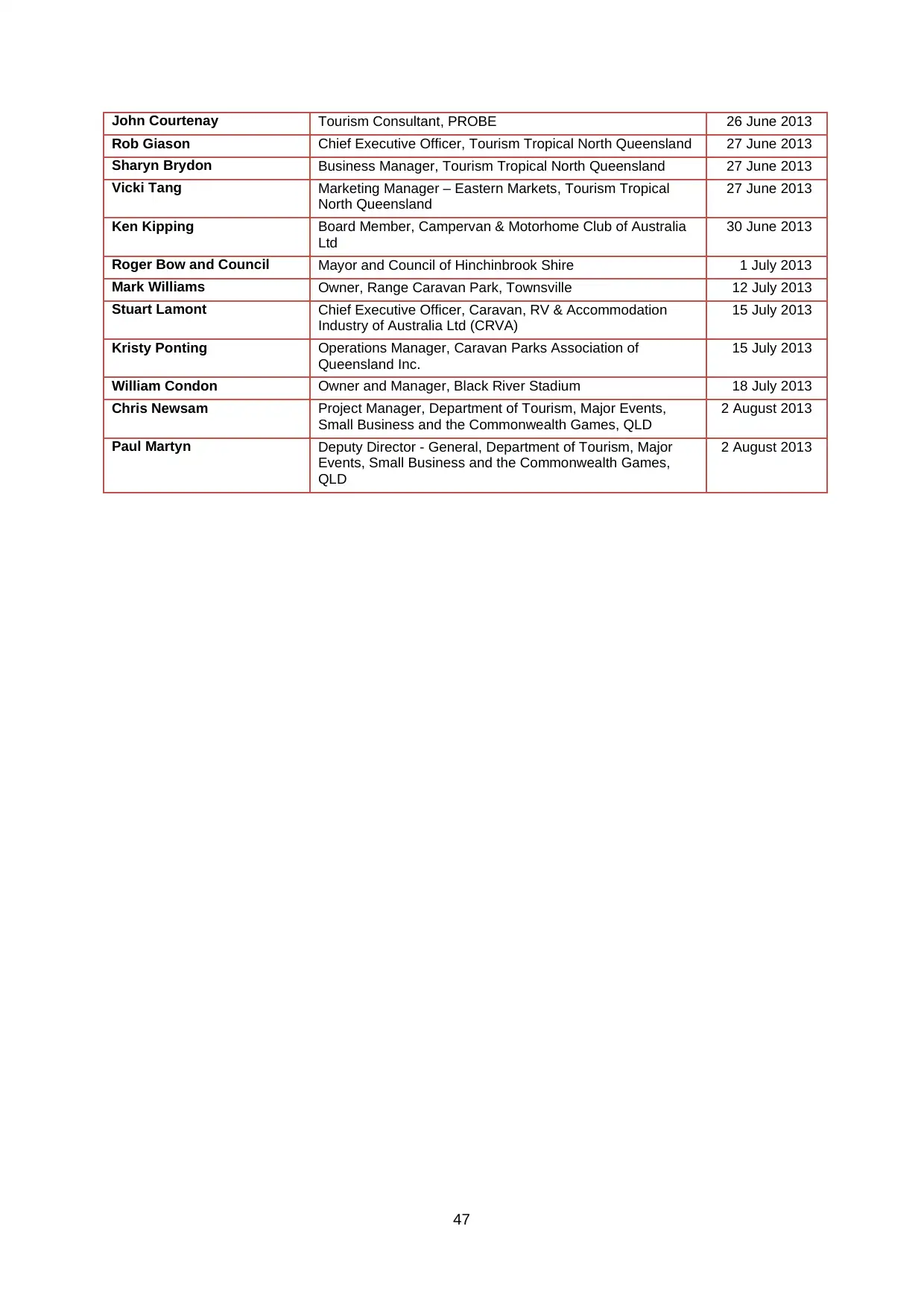

Appendix 1 Personnel and Organisations Consulted in Preparing this Report .................................... 46

Appendix 2 Background to the Tropics and Tourism ............................................................................ 48

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. i

Introduction.............................................................................................................................................. 1

An Organising Framework ...................................................................................................................... 1

1. Developing Tourism for Community Well-being.................................................................................. 5

2. Improving Cross-industry Opportunities .............................................................................................. 9

3. Reinforcing the Well Managed Natural Brand................................................................................... 12

4. Boosting Indigenous Opportunities ................................................................................................... 16

5. Incorporating the Slow Tourism Approach ........................................................................................ 20

6. Supporting the Domestic Backbone .................................................................................................. 23

7. Consolidating the International Strategies ........................................................................................ 27

8. Integrating Quality Markers ............................................................................................................... 32

9. Attending to Research Investment .................................................................................................... 35

10. Refreshing Educational, Extension and Career Structures ............................................................ 38

A Community Competition .................................................................................................................... 42

Appendix 1 Personnel and Organisations Consulted in Preparing this Report .................................... 46

Appendix 2 Background to the Tropics and Tourism ............................................................................ 48

i

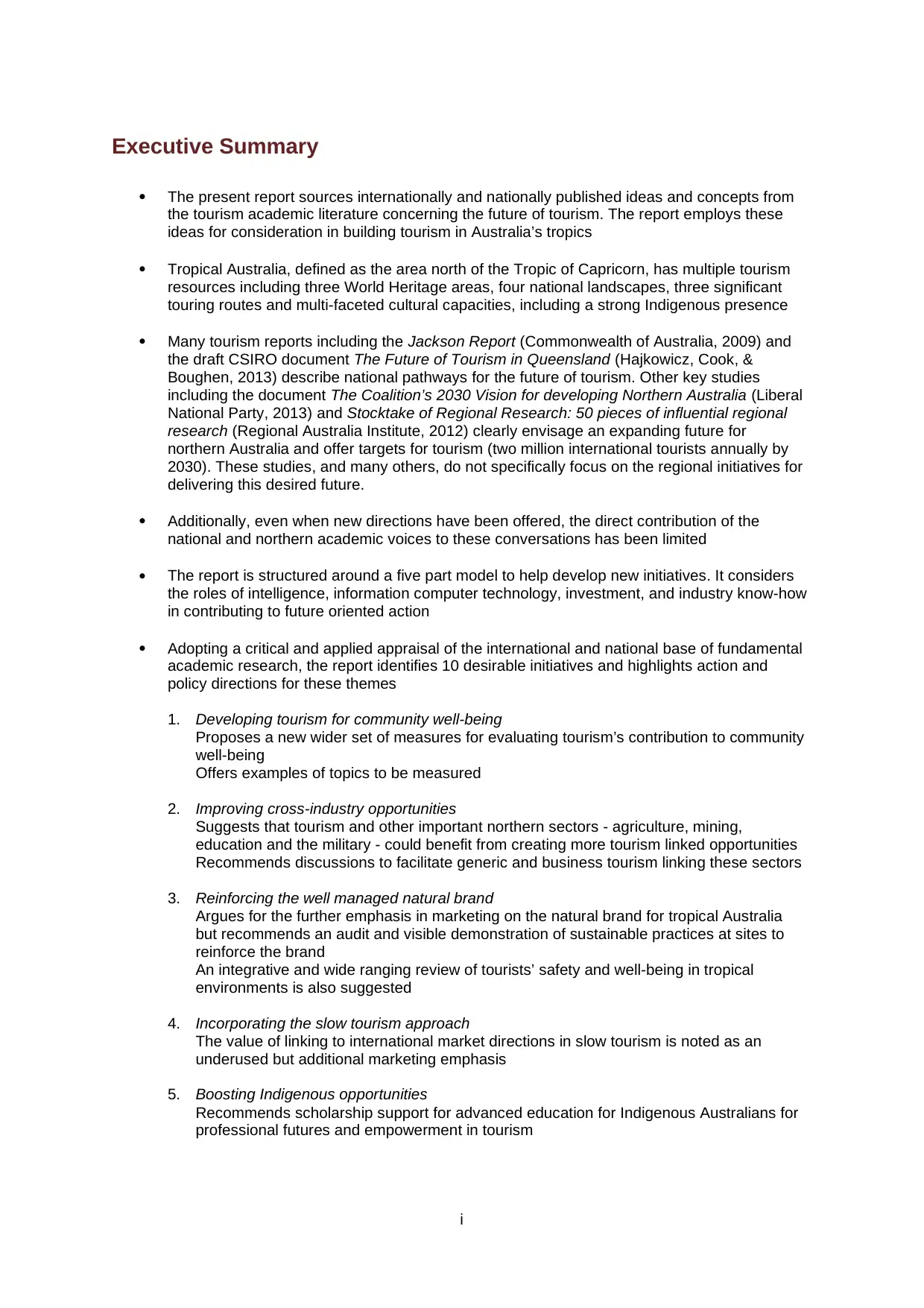

Executive Summary

The present report sources internationally and nationally published ideas and concepts from

the tourism academic literature concerning the future of tourism. The report employs these

ideas for consideration in building tourism in Australia’s tropics

Tropical Australia, defined as the area north of the Tropic of Capricorn, has multiple tourism

resources including three World Heritage areas, four national landscapes, three significant

touring routes and multi-faceted cultural capacities, including a strong Indigenous presence

Many tourism reports including the Jackson Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009) and

the draft CSIRO document The Future of Tourism in Queensland (Hajkowicz, Cook, &

Boughen, 2013) describe national pathways for the future of tourism. Other key studies

including the document The Coalition’s 2030 Vision for developing Northern Australia (Liberal

National Party, 2013) and Stocktake of Regional Research: 50 pieces of influential regional

research (Regional Australia Institute, 2012) clearly envisage an expanding future for

northern Australia and offer targets for tourism (two million international tourists annually by

2030). These studies, and many others, do not specifically focus on the regional initiatives for

delivering this desired future.

Additionally, even when new directions have been offered, the direct contribution of the

national and northern academic voices to these conversations has been limited

The report is structured around a five part model to help develop new initiatives. It considers

the roles of intelligence, information computer technology, investment, and industry know-how

in contributing to future oriented action

Adopting a critical and applied appraisal of the international and national base of fundamental

academic research, the report identifies 10 desirable initiatives and highlights action and

policy directions for these themes

1. Developing tourism for community well-being

Proposes a new wider set of measures for evaluating tourism’s contribution to community

well-being

Offers examples of topics to be measured

2. Improving cross-industry opportunities

Suggests that tourism and other important northern sectors - agriculture, mining,

education and the military - could benefit from creating more tourism linked opportunities

Recommends discussions to facilitate generic and business tourism linking these sectors

3. Reinforcing the well managed natural brand

Argues for the further emphasis in marketing on the natural brand for tropical Australia

but recommends an audit and visible demonstration of sustainable practices at sites to

reinforce the brand

An integrative and wide ranging review of tourists’ safety and well-being in tropical

environments is also suggested

4. Incorporating the slow tourism approach

The value of linking to international market directions in slow tourism is noted as an

underused but additional marketing emphasis

5. Boosting Indigenous opportunities

Recommends scholarship support for advanced education for Indigenous Australians for

professional futures and empowerment in tourism

Executive Summary

The present report sources internationally and nationally published ideas and concepts from

the tourism academic literature concerning the future of tourism. The report employs these

ideas for consideration in building tourism in Australia’s tropics

Tropical Australia, defined as the area north of the Tropic of Capricorn, has multiple tourism

resources including three World Heritage areas, four national landscapes, three significant

touring routes and multi-faceted cultural capacities, including a strong Indigenous presence

Many tourism reports including the Jackson Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009) and

the draft CSIRO document The Future of Tourism in Queensland (Hajkowicz, Cook, &

Boughen, 2013) describe national pathways for the future of tourism. Other key studies

including the document The Coalition’s 2030 Vision for developing Northern Australia (Liberal

National Party, 2013) and Stocktake of Regional Research: 50 pieces of influential regional

research (Regional Australia Institute, 2012) clearly envisage an expanding future for

northern Australia and offer targets for tourism (two million international tourists annually by

2030). These studies, and many others, do not specifically focus on the regional initiatives for

delivering this desired future.

Additionally, even when new directions have been offered, the direct contribution of the

national and northern academic voices to these conversations has been limited

The report is structured around a five part model to help develop new initiatives. It considers

the roles of intelligence, information computer technology, investment, and industry know-how

in contributing to future oriented action

Adopting a critical and applied appraisal of the international and national base of fundamental

academic research, the report identifies 10 desirable initiatives and highlights action and

policy directions for these themes

1. Developing tourism for community well-being

Proposes a new wider set of measures for evaluating tourism’s contribution to community

well-being

Offers examples of topics to be measured

2. Improving cross-industry opportunities

Suggests that tourism and other important northern sectors - agriculture, mining,

education and the military - could benefit from creating more tourism linked opportunities

Recommends discussions to facilitate generic and business tourism linking these sectors

3. Reinforcing the well managed natural brand

Argues for the further emphasis in marketing on the natural brand for tropical Australia

but recommends an audit and visible demonstration of sustainable practices at sites to

reinforce the brand

An integrative and wide ranging review of tourists’ safety and well-being in tropical

environments is also suggested

4. Incorporating the slow tourism approach

The value of linking to international market directions in slow tourism is noted as an

underused but additional marketing emphasis

5. Boosting Indigenous opportunities

Recommends scholarship support for advanced education for Indigenous Australians for

professional futures and empowerment in tourism

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ii

6. Supporting the domestic backbone

Argues for systematic soft and hard infrastructure development to support drive tourism

Recommends a uniform approach to tourism discounts for local regional visitors

Supports the importance of national and international sporting events being located in the

region to boost local and out of region tourists

7. Consolidating the international strategies

Recommends a focus on the young Chinese independent market

Proposes using local voices and endogenous marketing to assure the authenticity of the

experience appeal

8. Integrating quality markers

Proposes exploring the integration and alignment between Australia’s accreditation and

recommendation systems with international approaches

9. Attending to research investment

Notes the funding drought for fundamental and applied research in tourism at the

northern/tropical scale while supporting the efforts of Tourism Research Australia for its

particular role

Proposes explicit restatement in Australian Research Council grant schemes and T-

QUAL grant scheme for research in tourism as a nationally significant priority for funding

Proposes greater interchange between government, industry and academic personnel in

terms of visitor schemes and options similar to international practices in terms of senior

business and government visitors and professors for a week

10. Refreshing educational, career and extension structures

Introduces a potential tourism employment classification scheme which boosts

transferability between tourism, events and leisure roles.

Recommends the development of tourism extension officers, analogous to roles in other

major sectors such as agriculture, to support the delivery of research and advisory

information

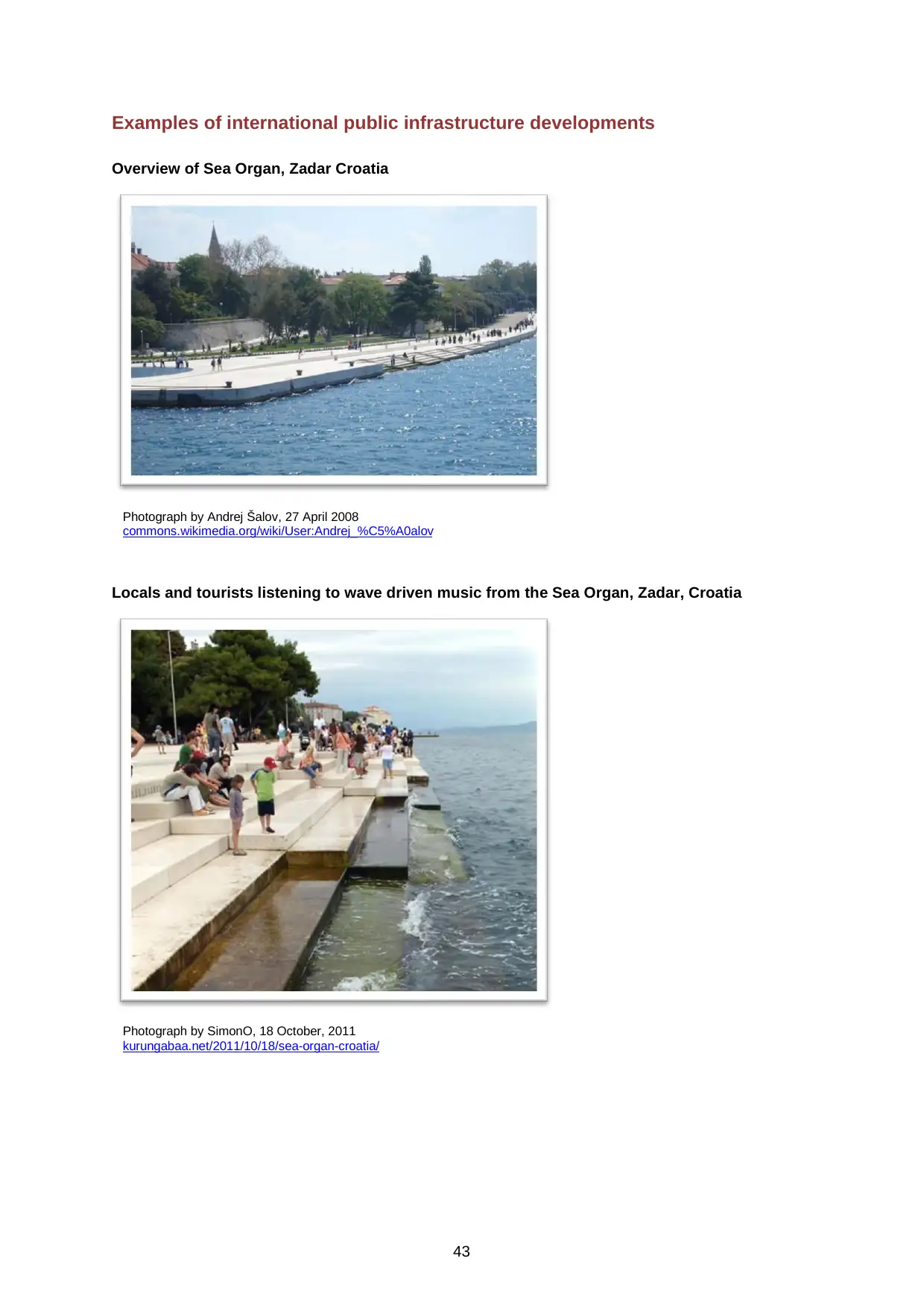

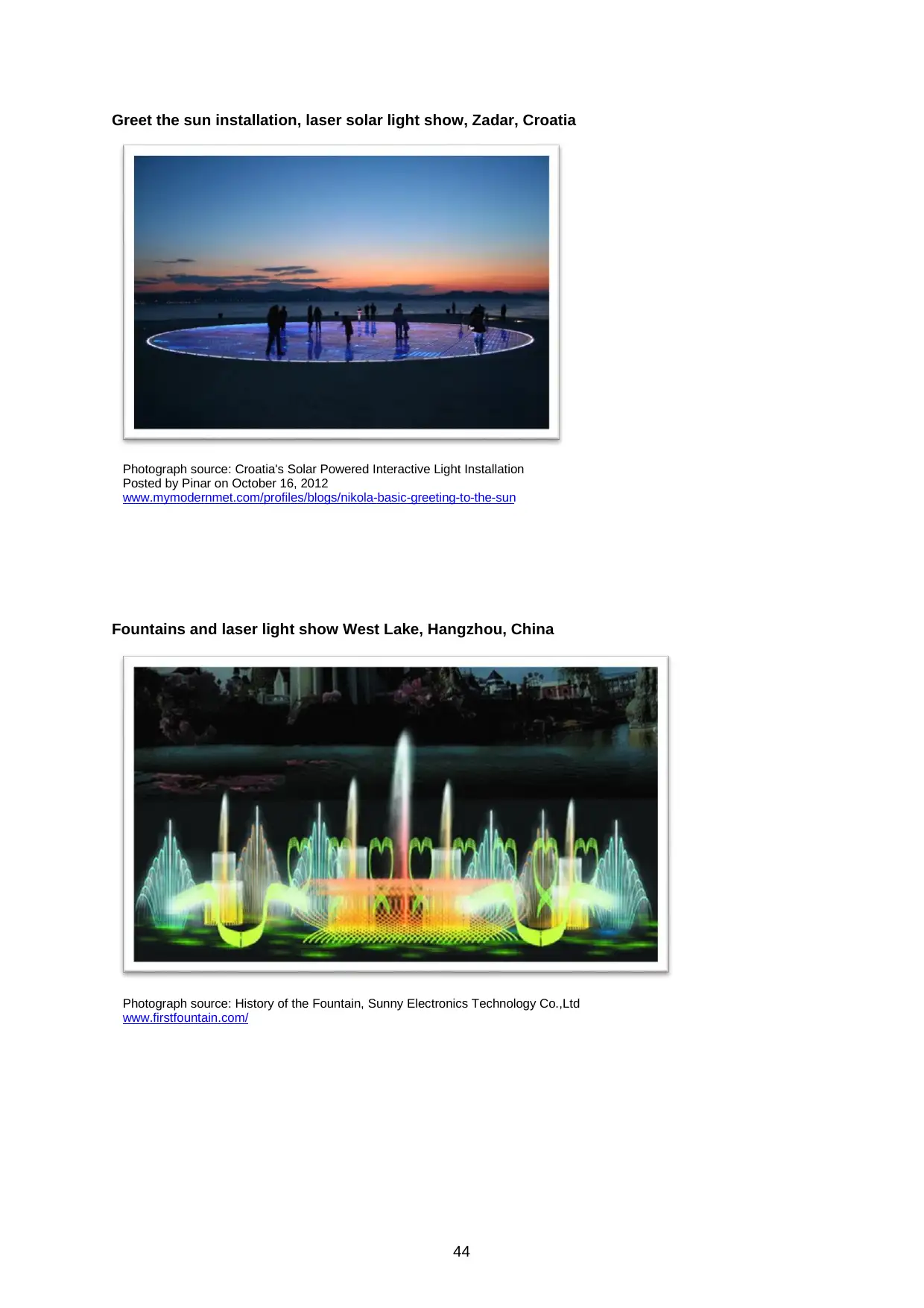

A community based competition for innovative public tropical infrastructure is proposed in the

context of recent global initiatives for tourism.

6. Supporting the domestic backbone

Argues for systematic soft and hard infrastructure development to support drive tourism

Recommends a uniform approach to tourism discounts for local regional visitors

Supports the importance of national and international sporting events being located in the

region to boost local and out of region tourists

7. Consolidating the international strategies

Recommends a focus on the young Chinese independent market

Proposes using local voices and endogenous marketing to assure the authenticity of the

experience appeal

8. Integrating quality markers

Proposes exploring the integration and alignment between Australia’s accreditation and

recommendation systems with international approaches

9. Attending to research investment

Notes the funding drought for fundamental and applied research in tourism at the

northern/tropical scale while supporting the efforts of Tourism Research Australia for its

particular role

Proposes explicit restatement in Australian Research Council grant schemes and T-

QUAL grant scheme for research in tourism as a nationally significant priority for funding

Proposes greater interchange between government, industry and academic personnel in

terms of visitor schemes and options similar to international practices in terms of senior

business and government visitors and professors for a week

10. Refreshing educational, career and extension structures

Introduces a potential tourism employment classification scheme which boosts

transferability between tourism, events and leisure roles.

Recommends the development of tourism extension officers, analogous to roles in other

major sectors such as agriculture, to support the delivery of research and advisory

information

A community based competition for innovative public tropical infrastructure is proposed in the

context of recent global initiatives for tourism.

1

Introduction

This paper seeks to contribute to the discussion of the future options and initiatives for tropical tourism

across northern Australia. The work is conducted through the sponsorship of the Cairns Institute,

James Cook University. The contribution rests firmly on the global and Australian academic tourism

literature. To assist easy readability, the report avoids the dominant academic tradition of citing

numerous references throughout the paper. Only key references are noted in the main body of the

text. A concise reference list is attached at the end of each section.

The paper offers ten issues to consider in the planning and visioning process. These issues are

framed as initiatives assisting the future of a profitable, environmentally aware, and community

supported tropical tourism sector. The approach does not predict or forecast the future but rather

outlines some issues judged to be desirable for developing tropical tourism activity. A community

competition to suggest examples of new public infrastructure as signals for tourism innovation in the

tropics is also proposed.

The paper initially considers the fundamental forces which drive innovation in Australian tourism at

this point in time. The identified forces are Intelligence, Industry capabilities, Information and

computer technologies, and Investment. This classification rests on a 10 year academic review of

strategic issues in the Australian tourism industry (Ruhanen, Mclennan, & Moyle, 2013) and an

understanding of policy and planning processes for destinations (Edgell & Swanson, 2013). Building

on the interplay of these forces, the paper identifies ten initiatives for a “brighter future for life in the

tropics”. This position is consistent with the strategic intent of James Cook University and the Cairns

Institute.

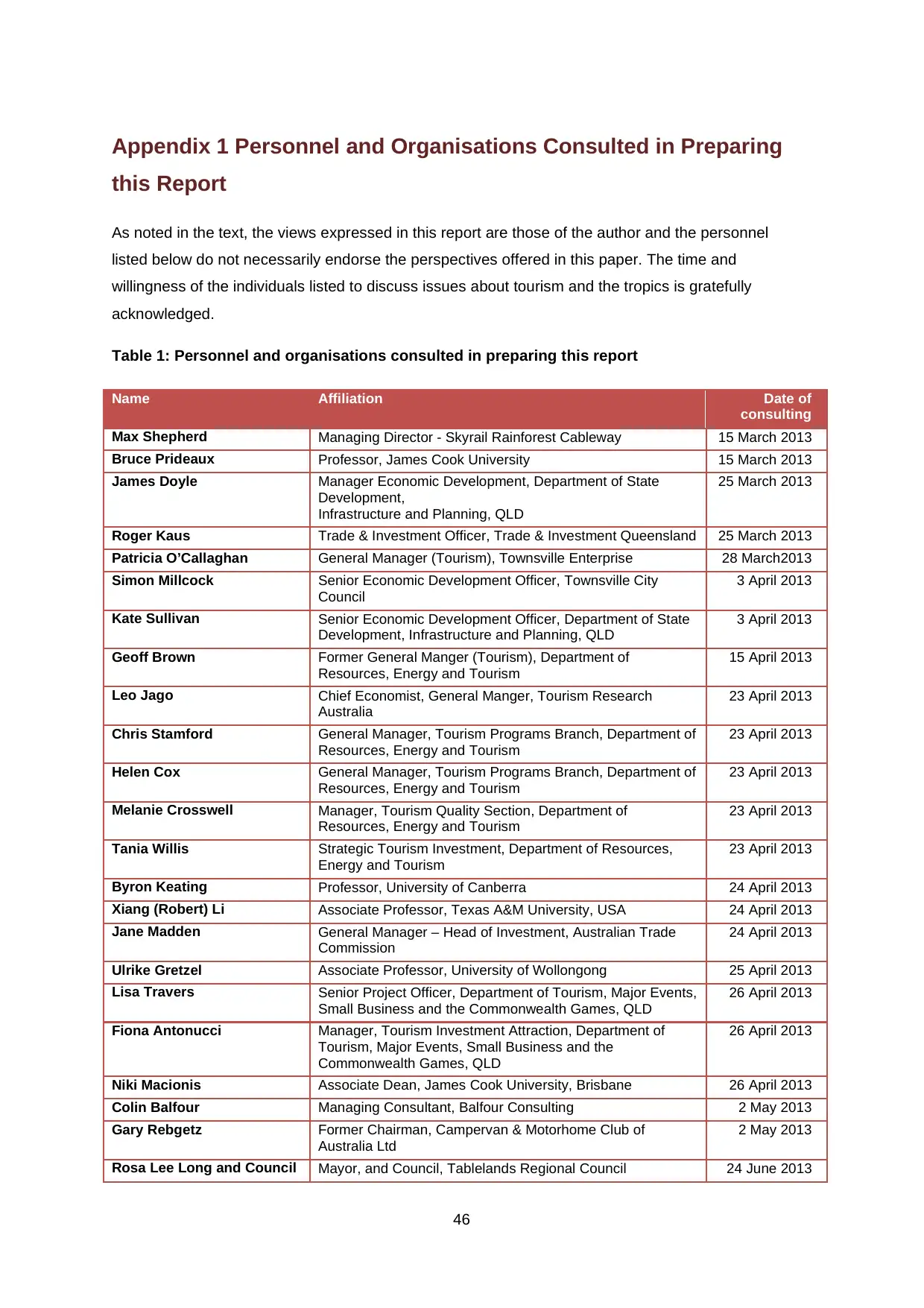

In addition to considering the academic sources, a personal familiarity with current industry and

government issues was developed by meeting a range of key tourism government and business

personnel. The author gratefully acknowledges the time of the individuals and organisations involved

in these meetings. They are listed in Appendix 1. There is no implication that the inclusion of any

individual or organisation in this listing in any way endorses the points made in this paper. Appendix 2

provides introductory notes for those less familiar with the tropics and the role of tourism across this

part of northern Australia.

An Organising Framework

In the discussions undertaken to construct this document there was a recurring theme of the need for

innovation and new initiatives including novel products and experiences in tropical Australia. This

theme was taken as the key issue for the paper but any innovation has to fit within a developmental

vision embracing the multiple goals of profitability, community acceptance and environmental

responsibility. The Coalition’s (now the elected Government’s) 2030 vision for developing Northern

Introduction

This paper seeks to contribute to the discussion of the future options and initiatives for tropical tourism

across northern Australia. The work is conducted through the sponsorship of the Cairns Institute,

James Cook University. The contribution rests firmly on the global and Australian academic tourism

literature. To assist easy readability, the report avoids the dominant academic tradition of citing

numerous references throughout the paper. Only key references are noted in the main body of the

text. A concise reference list is attached at the end of each section.

The paper offers ten issues to consider in the planning and visioning process. These issues are

framed as initiatives assisting the future of a profitable, environmentally aware, and community

supported tropical tourism sector. The approach does not predict or forecast the future but rather

outlines some issues judged to be desirable for developing tropical tourism activity. A community

competition to suggest examples of new public infrastructure as signals for tourism innovation in the

tropics is also proposed.

The paper initially considers the fundamental forces which drive innovation in Australian tourism at

this point in time. The identified forces are Intelligence, Industry capabilities, Information and

computer technologies, and Investment. This classification rests on a 10 year academic review of

strategic issues in the Australian tourism industry (Ruhanen, Mclennan, & Moyle, 2013) and an

understanding of policy and planning processes for destinations (Edgell & Swanson, 2013). Building

on the interplay of these forces, the paper identifies ten initiatives for a “brighter future for life in the

tropics”. This position is consistent with the strategic intent of James Cook University and the Cairns

Institute.

In addition to considering the academic sources, a personal familiarity with current industry and

government issues was developed by meeting a range of key tourism government and business

personnel. The author gratefully acknowledges the time of the individuals and organisations involved

in these meetings. They are listed in Appendix 1. There is no implication that the inclusion of any

individual or organisation in this listing in any way endorses the points made in this paper. Appendix 2

provides introductory notes for those less familiar with the tropics and the role of tourism across this

part of northern Australia.

An Organising Framework

In the discussions undertaken to construct this document there was a recurring theme of the need for

innovation and new initiatives including novel products and experiences in tropical Australia. This

theme was taken as the key issue for the paper but any innovation has to fit within a developmental

vision embracing the multiple goals of profitability, community acceptance and environmental

responsibility. The Coalition’s (now the elected Government’s) 2030 vision for developing Northern

2

Australia written in June 2013 argues for a 2030 goal of two million international visitors annually

(Liberal National Party, 2013). Ways to develop tourism in northern Australia which might assist in

reaching this kind of goal are core to the present paper.

There are demanding goals for new developments which include the all-important ability to have new

projects funded. Additionally, a clear perspective was expressed in many meetings that providing

fresh experiences rather than competing with existing offerings was required. Further, the need to

build tourism in ways seen by the community as desirable was emphasised. All of these points are

also frequently reported in the academic tourism literature (Cohen, 2011; Edgell & Swanson, 2013;

Morrison, 2013).

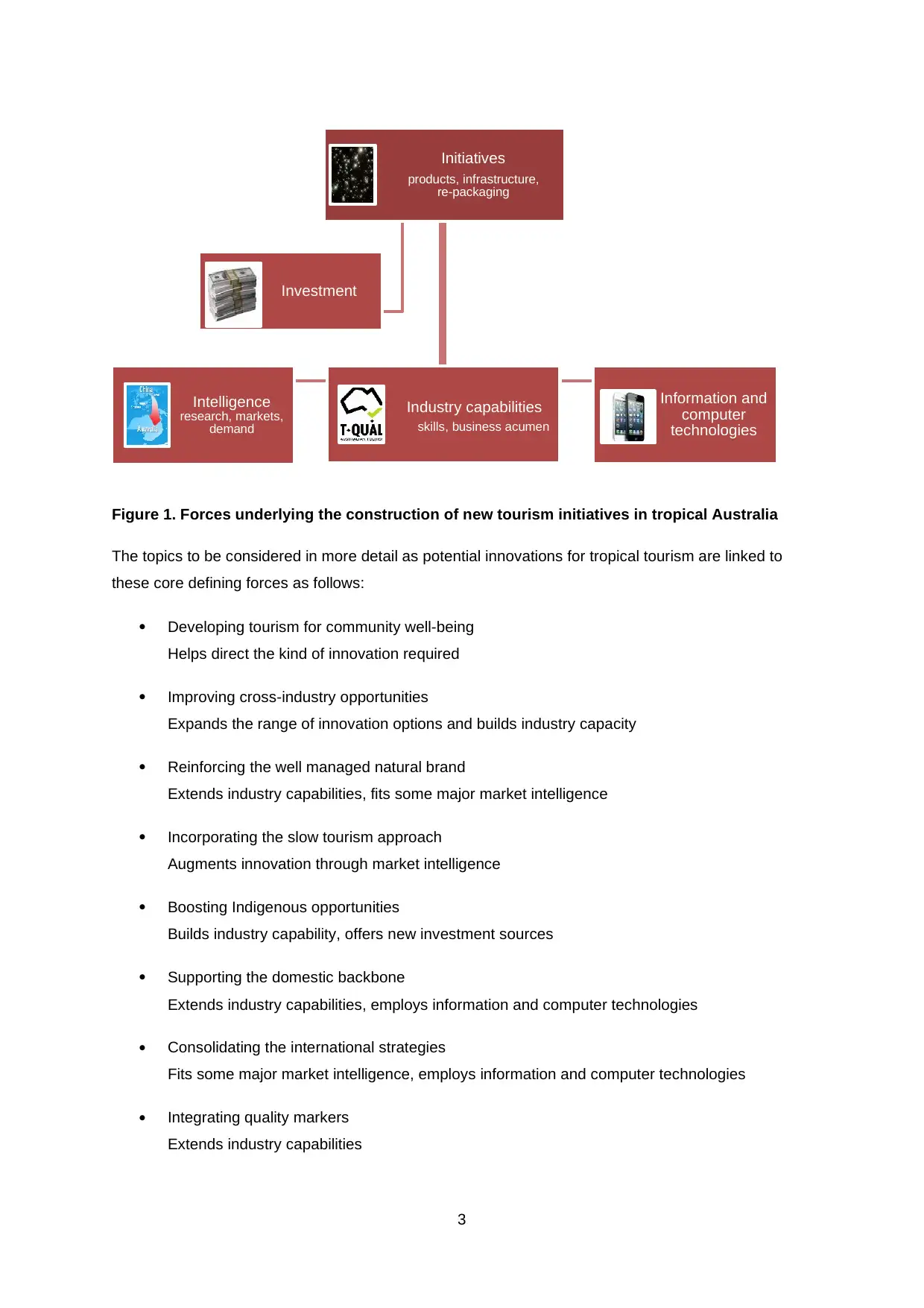

An analysis of the forces shaping innovation can be provided in the tropical tourism context by

classifying the defining forces into the following themes; Intelligence, Industry capabilities, Information

and computer technologies, and Investment. These themes aggregate the list of issues produced in

such documents as the 2013 CSIRO report on The Future of Tourism in Queensland (Hajkowicz, et

al., 2013). The defining forces are succinctly defined as follows:

Intelligence: the sum of the available assessment of market and supply issues led by Tourism

Research Australia but enhanced by consulting and academic analyses. Changes and the trajectory

of new markets and their interests define this component and shape the opportunities for innovation.

Industry capabilities: the level of skills and human resources currently and likely to be available in

the future to meet the predicted demand. This topic includes the issue of education and training and

updating the knowledge base of personnel in different parts of the sector. The quality of experience or

product on offer to the market is subsumed within this category.

Information and computer technologies: digital capacity represents a dynamic tool in tourism in all

phases: pre-trip marketing, onsite management and post-trip reporting. Technology management of

sites and businesses for profitability and sustainability are opportunities for managers and owners at

varied scales.

Investment: Repeated or return investment and new entrants into the tourism sector are required to

compete with the different kinds of tourism in other competitive destinations.

This paper derives a number of issues from the interaction of these core forces. It then summarises

academic directions relevant to these issues.

Australia written in June 2013 argues for a 2030 goal of two million international visitors annually

(Liberal National Party, 2013). Ways to develop tourism in northern Australia which might assist in

reaching this kind of goal are core to the present paper.

There are demanding goals for new developments which include the all-important ability to have new

projects funded. Additionally, a clear perspective was expressed in many meetings that providing

fresh experiences rather than competing with existing offerings was required. Further, the need to

build tourism in ways seen by the community as desirable was emphasised. All of these points are

also frequently reported in the academic tourism literature (Cohen, 2011; Edgell & Swanson, 2013;

Morrison, 2013).

An analysis of the forces shaping innovation can be provided in the tropical tourism context by

classifying the defining forces into the following themes; Intelligence, Industry capabilities, Information

and computer technologies, and Investment. These themes aggregate the list of issues produced in

such documents as the 2013 CSIRO report on The Future of Tourism in Queensland (Hajkowicz, et

al., 2013). The defining forces are succinctly defined as follows:

Intelligence: the sum of the available assessment of market and supply issues led by Tourism

Research Australia but enhanced by consulting and academic analyses. Changes and the trajectory

of new markets and their interests define this component and shape the opportunities for innovation.

Industry capabilities: the level of skills and human resources currently and likely to be available in

the future to meet the predicted demand. This topic includes the issue of education and training and

updating the knowledge base of personnel in different parts of the sector. The quality of experience or

product on offer to the market is subsumed within this category.

Information and computer technologies: digital capacity represents a dynamic tool in tourism in all

phases: pre-trip marketing, onsite management and post-trip reporting. Technology management of

sites and businesses for profitability and sustainability are opportunities for managers and owners at

varied scales.

Investment: Repeated or return investment and new entrants into the tourism sector are required to

compete with the different kinds of tourism in other competitive destinations.

This paper derives a number of issues from the interaction of these core forces. It then summarises

academic directions relevant to these issues.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3

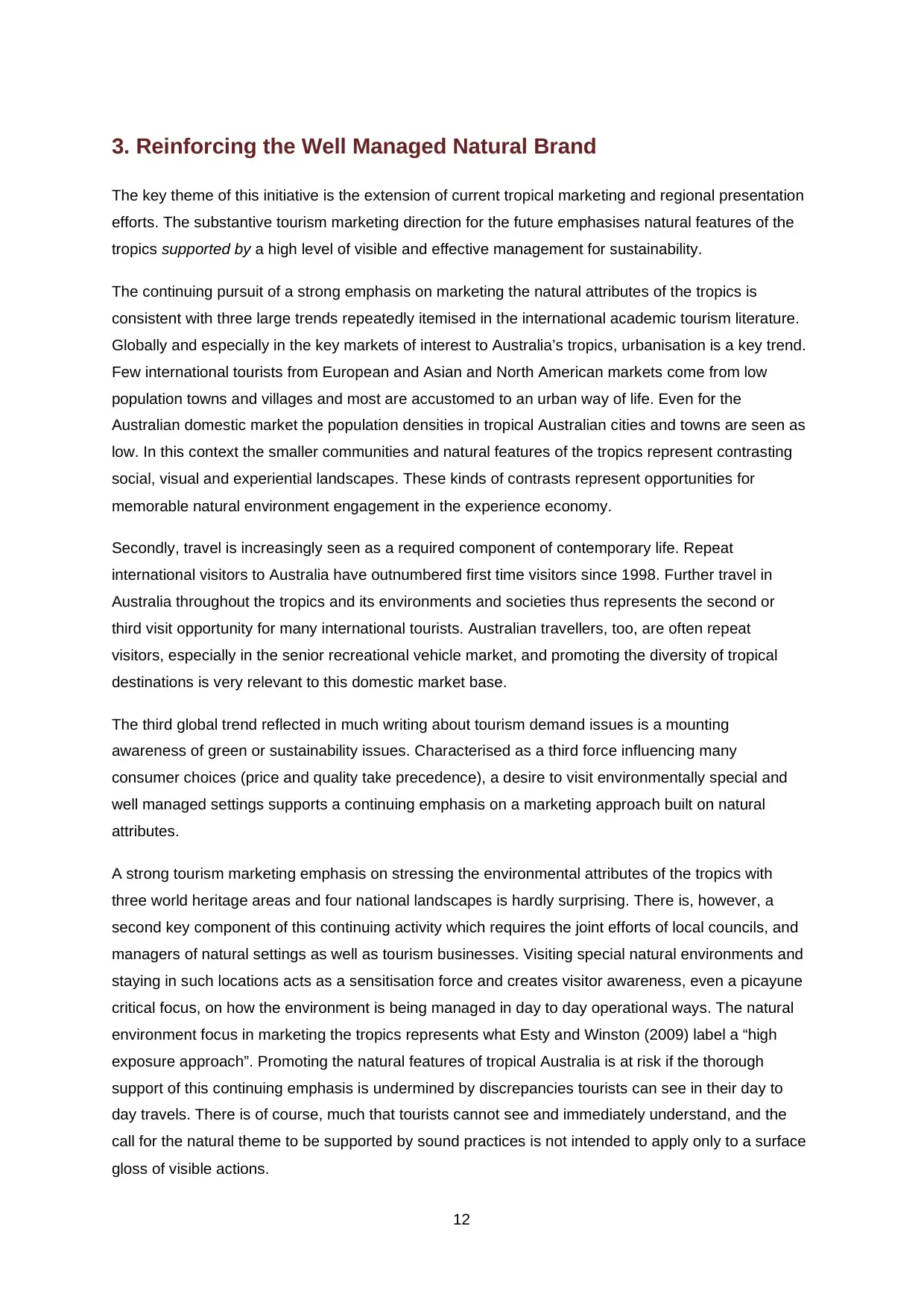

Figure 1. Forces underlying the construction of new tourism initiatives in tropical Australia

The topics to be considered in more detail as potential innovations for tropical tourism are linked to

these core defining forces as follows:

Developing tourism for community well-being

Helps direct the kind of innovation required

Improving cross-industry opportunities

Expands the range of innovation options and builds industry capacity

Reinforcing the well managed natural brand

Extends industry capabilities, fits some major market intelligence

Incorporating the slow tourism approach

Augments innovation through market intelligence

Boosting Indigenous opportunities

Builds industry capability, offers new investment sources

Supporting the domestic backbone

Extends industry capabilities, employs information and computer technologies

Consolidating the international strategies

Fits some major market intelligence, employs information and computer technologies

Integrating quality markers

Extends industry capabilities

Initiatives

products, infrastructure,

re-packaging

Intelligence

research, markets,

demand

Industry capabilities

skills, business acumen

Information and

computer

technologies

Investment

Figure 1. Forces underlying the construction of new tourism initiatives in tropical Australia

The topics to be considered in more detail as potential innovations for tropical tourism are linked to

these core defining forces as follows:

Developing tourism for community well-being

Helps direct the kind of innovation required

Improving cross-industry opportunities

Expands the range of innovation options and builds industry capacity

Reinforcing the well managed natural brand

Extends industry capabilities, fits some major market intelligence

Incorporating the slow tourism approach

Augments innovation through market intelligence

Boosting Indigenous opportunities

Builds industry capability, offers new investment sources

Supporting the domestic backbone

Extends industry capabilities, employs information and computer technologies

Consolidating the international strategies

Fits some major market intelligence, employs information and computer technologies

Integrating quality markers

Extends industry capabilities

Initiatives

products, infrastructure,

re-packaging

Intelligence

research, markets,

demand

Industry capabilities

skills, business acumen

Information and

computer

technologies

Investment

4

Attending to research investment

A focused form of investment

Refreshing educational, career and extension structures

Builds industry capability.

References

Bailey, G., & Jago, L. (2012). State of the industry 2012. Canberra: Tourism Research Australia.

Cohen, E. (2011). The changing faces of contemporary tourism. Folia Touristica, 25(1), 13-19.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2009). The Jackson report on behalf of the steering committee:

Informing national long-term tourism strategy. Canberra: Tourism Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2012). Australia in the Asian century. White paper. Retrieved from

http://asiancentury.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/white-paper/australia-in-the-asian-century-

white-paper.pdf

Edgell, D. L., & Swanson, J. R. (2013). Tourism policy and planning. Yesterday, today, and tomorrow

(2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Hajkowicz, S. A., Cook, H., & Boughen, N. (2013). The future of tourism in Queensland. Global

megatrends creating opportunities and challenges over the coming twenty years. Draft for

comment. Retrieved from http://www.globaleco.com.au/Publications/Megatrends%20-

%20tourism%20CSIRO.pdf

Hjalager, A.-M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1-12.

Liberal National Party. (2013). The Coalition’s 2030 vision for developing northern Australia. June

2013. Retrieved from http://www.liberal.org.au/2030-vision-developing-northern-australia

Mei, X. Y., Arcodia, C., & Ruhanen, L. (2012). Towards tourism innovation: A critical review of public

polices at the national level. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 92-105.

Morrison, A. (2013). Marketing and managing tourism destinations. New York: Routledge.

Regional Australia Institute. (2012). Stocktake of regional research: 50 pieces of influential regional

research. Retrieved from http://www.regionalaustralia.org.au/wp-

content/uploads/2013/07/RAI-Stocktake-of-Regional-Research-50-pieces-of-influential-

research.pdf

Ruhanen, L., Mclennan, C., & Moyle, B. D. (2013). Strategic issues in the Australian tourism industry:

A 10 year analysis of national strategies and plans. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,

18(3), 220-240. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2011.640701

Attending to research investment

A focused form of investment

Refreshing educational, career and extension structures

Builds industry capability.

References

Bailey, G., & Jago, L. (2012). State of the industry 2012. Canberra: Tourism Research Australia.

Cohen, E. (2011). The changing faces of contemporary tourism. Folia Touristica, 25(1), 13-19.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2009). The Jackson report on behalf of the steering committee:

Informing national long-term tourism strategy. Canberra: Tourism Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2012). Australia in the Asian century. White paper. Retrieved from

http://asiancentury.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/white-paper/australia-in-the-asian-century-

white-paper.pdf

Edgell, D. L., & Swanson, J. R. (2013). Tourism policy and planning. Yesterday, today, and tomorrow

(2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Hajkowicz, S. A., Cook, H., & Boughen, N. (2013). The future of tourism in Queensland. Global

megatrends creating opportunities and challenges over the coming twenty years. Draft for

comment. Retrieved from http://www.globaleco.com.au/Publications/Megatrends%20-

%20tourism%20CSIRO.pdf

Hjalager, A.-M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1-12.

Liberal National Party. (2013). The Coalition’s 2030 vision for developing northern Australia. June

2013. Retrieved from http://www.liberal.org.au/2030-vision-developing-northern-australia

Mei, X. Y., Arcodia, C., & Ruhanen, L. (2012). Towards tourism innovation: A critical review of public

polices at the national level. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 92-105.

Morrison, A. (2013). Marketing and managing tourism destinations. New York: Routledge.

Regional Australia Institute. (2012). Stocktake of regional research: 50 pieces of influential regional

research. Retrieved from http://www.regionalaustralia.org.au/wp-

content/uploads/2013/07/RAI-Stocktake-of-Regional-Research-50-pieces-of-influential-

research.pdf

Ruhanen, L., Mclennan, C., & Moyle, B. D. (2013). Strategic issues in the Australian tourism industry:

A 10 year analysis of national strategies and plans. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,

18(3), 220-240. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2011.640701

5

1. Developing Tourism for Community Well-being

The national and international academic literature on the topic of community well-being offers a vision

and a set of measures for studies of the future. The approach recognises the need for tourism to

function successfully in a number of domains to meet the requirements of multiple stakeholders. The

term ‘capital’ is often used in this thorough approach to characterising the well-being of communities.

In this context ‘capital’ essentially means the level or state of the resources, skills or facilities in a

number of important topic areas. The focus includes measures of human (individual), social (including

administrative), cultural, natural, physical (infrastructure) and financial (including economic) capital.

The scale at which the forms of capital are assessed is frequently a region, often analogous to the

scale and size of tourism regions used in tropical Australia. Measures of capital can also exist for a

city, town or local government area. Additionally a large tourism business such an attraction or a

hotel/resort can also be considered in terms of their role in generating these varied forms of capital.

All forms of capital can be seen as augmented or decreased by the type of tourism operating in a

location.

The ideas underpinning community well-being emerged from a growing dissatisfaction with a simple

focus on economic measures of community growth and development. Following the ideas outlined by

Nobel Prize winner A. Sen, and many others, there has been a concerted attempt in academic circles

and by some governments to provide these more holistic appraisals of the quality of life and well-

being in a region or specific area. It can be argued that the future credibility and power of tourism as

perceived in government circles is increasingly being related to more than economic performance and

is beginning to envisage these kinds of capital or wide resource based approaches to community well-

being. It is these issues and the specific measures to asses them which are likely to become the new

Key Performance Themes and Indicators for those who manage tourism and events.

This more holistic approach to assessing the role of tourism and its influences is underpinned by the

continuing evolution of the concerns with sustainability and the impacts of tourism which emerged in

the 1990s. The early approaches to tourism sustainability were strongly oriented towards limiting

damage to natural environments while maintaining tourism profitability. The sustainability concerns

have widened to embrace more fully the social, cultural and organisational health of communities. The

term the ‘quadruple bottom line’ has become the phraseology superseding the earlier triple bottom

line approach of people, planet and profit.

A consideration of community well-being in terms of the forms of capital requires those who think

about, plan and write vision statements relating to tourism to focus not just on but beyond the earlier

treatment of sustainability. A specific treatment of community well-being by Morton and Edwards

(2012) at the local government level in the tropics suggests setting targets for the following themes

which are linked to aspects of capital:

1. Developing Tourism for Community Well-being

The national and international academic literature on the topic of community well-being offers a vision

and a set of measures for studies of the future. The approach recognises the need for tourism to

function successfully in a number of domains to meet the requirements of multiple stakeholders. The

term ‘capital’ is often used in this thorough approach to characterising the well-being of communities.

In this context ‘capital’ essentially means the level or state of the resources, skills or facilities in a

number of important topic areas. The focus includes measures of human (individual), social (including

administrative), cultural, natural, physical (infrastructure) and financial (including economic) capital.

The scale at which the forms of capital are assessed is frequently a region, often analogous to the

scale and size of tourism regions used in tropical Australia. Measures of capital can also exist for a

city, town or local government area. Additionally a large tourism business such an attraction or a

hotel/resort can also be considered in terms of their role in generating these varied forms of capital.

All forms of capital can be seen as augmented or decreased by the type of tourism operating in a

location.

The ideas underpinning community well-being emerged from a growing dissatisfaction with a simple

focus on economic measures of community growth and development. Following the ideas outlined by

Nobel Prize winner A. Sen, and many others, there has been a concerted attempt in academic circles

and by some governments to provide these more holistic appraisals of the quality of life and well-

being in a region or specific area. It can be argued that the future credibility and power of tourism as

perceived in government circles is increasingly being related to more than economic performance and

is beginning to envisage these kinds of capital or wide resource based approaches to community well-

being. It is these issues and the specific measures to asses them which are likely to become the new

Key Performance Themes and Indicators for those who manage tourism and events.

This more holistic approach to assessing the role of tourism and its influences is underpinned by the

continuing evolution of the concerns with sustainability and the impacts of tourism which emerged in

the 1990s. The early approaches to tourism sustainability were strongly oriented towards limiting

damage to natural environments while maintaining tourism profitability. The sustainability concerns

have widened to embrace more fully the social, cultural and organisational health of communities. The

term the ‘quadruple bottom line’ has become the phraseology superseding the earlier triple bottom

line approach of people, planet and profit.

A consideration of community well-being in terms of the forms of capital requires those who think

about, plan and write vision statements relating to tourism to focus not just on but beyond the earlier

treatment of sustainability. A specific treatment of community well-being by Morton and Edwards

(2012) at the local government level in the tropics suggests setting targets for the following themes

which are linked to aspects of capital:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

6

1. Healthy, safe and inclusive communities (human capital, social capital)

2. Culturally rich and vibrant communities (cultural capital)

3. Dynamic resilient local economies (financial capital, social capital)

4. Sustainable built and natural environments (natural capital, physical capital)

5. Democratic and engaged communities (social capital).

These kinds of topics require a re-orientation in the evaluation of tourism. Rather than focusing on

tourism success as measured by visitor arrival numbers, length of stay, expenditure and the

minimisation of negative social and environmental effects, there can be a contemplation of the wide

ranging influence of tourism. The questions become: “What is tourism’s role in contributing to healthy,

safe and inclusive communities?” and, “What is tourism’s role in building culturally rich and vibrant

communities?” and so on. This wider ambit of tourism performance can usefully draw tourism into the

centre of all economic and community development discussions and remove the silo-style appraisals

when tourism is seen as a stand-alone sector with its own measures, problems and outcomes.

There is a rich literature being built in academic texts and filtering into government circles to assess

the performance of regions and the contribution of industries to these kinds of goals. The present

document can simply direct attention to this newer way of thinking about the outcomes and

consequence of tourism and direct those who assess tourism to these new goals and accompanying

measures (see References). To at least sample the flavour of the approach some of the suggested

measures include:

SAMPLE QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

Healthy safe and inclusive communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses influence amenity for young children, young adults, and seniors?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide for people with a physical disability?

How do tourism/tourism/businesses influence or manage safety in tourism areas or activities?

Has tourism/this tourism business helped social interaction within the local community’s public

spaces?

How do tourism/tourism businesses create and manage health issues in their setting?

How do/does tourism/this tourism business create access to the internet?

1. Healthy, safe and inclusive communities (human capital, social capital)

2. Culturally rich and vibrant communities (cultural capital)

3. Dynamic resilient local economies (financial capital, social capital)

4. Sustainable built and natural environments (natural capital, physical capital)

5. Democratic and engaged communities (social capital).

These kinds of topics require a re-orientation in the evaluation of tourism. Rather than focusing on

tourism success as measured by visitor arrival numbers, length of stay, expenditure and the

minimisation of negative social and environmental effects, there can be a contemplation of the wide

ranging influence of tourism. The questions become: “What is tourism’s role in contributing to healthy,

safe and inclusive communities?” and, “What is tourism’s role in building culturally rich and vibrant

communities?” and so on. This wider ambit of tourism performance can usefully draw tourism into the

centre of all economic and community development discussions and remove the silo-style appraisals

when tourism is seen as a stand-alone sector with its own measures, problems and outcomes.

There is a rich literature being built in academic texts and filtering into government circles to assess

the performance of regions and the contribution of industries to these kinds of goals. The present

document can simply direct attention to this newer way of thinking about the outcomes and

consequence of tourism and direct those who assess tourism to these new goals and accompanying

measures (see References). To at least sample the flavour of the approach some of the suggested

measures include:

SAMPLE QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

Healthy safe and inclusive communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses influence amenity for young children, young adults, and seniors?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide for people with a physical disability?

How do tourism/tourism/businesses influence or manage safety in tourism areas or activities?

Has tourism/this tourism business helped social interaction within the local community’s public

spaces?

How do tourism/tourism businesses create and manage health issues in their setting?

How do/does tourism/this tourism business create access to the internet?

7

Culturally rich and vibrant communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for local citizens to effectively engage in:

sport and recreation, art and cultural activities?

How do tourism/tourism businesses welcome people from different cultures?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for employment for people of different

ethnic and social backgrounds?

How do tourism/tourism businesses and especially events energise cultural activities?

Dynamic resilient local economies

What total expenditure in the community is generated by tourists attracted by tourism/tourism

businesses?

How well are tourism/tourism businesses providing a return on investment to maintain financially

viable operations over time?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide job security?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide rates of pay commensurate with the skills and time

expectations of employees?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide training and build careers and incentives for long term

employment?

Sustainable built and natural environments

How do tourism/tourism businesses protect and conserve the natural environment?

How do tourism businesses manage waste, reduce energy consumption and demonstrate good

environmental practices?

How do tourism/tourism businesses affect the liveable built environment?

How do tourism businesses affect private/public transport and public crowding?

Democratic and engaged communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for the community to comment on their

activities?

What are the preferred tourism styles for the community considering expenditure and the influence of

different tourist markets segments across the forms of capital?

How do tourism/tourism businesses contribute to the promotion and image of the region?

Culturally rich and vibrant communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for local citizens to effectively engage in:

sport and recreation, art and cultural activities?

How do tourism/tourism businesses welcome people from different cultures?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for employment for people of different

ethnic and social backgrounds?

How do tourism/tourism businesses and especially events energise cultural activities?

Dynamic resilient local economies

What total expenditure in the community is generated by tourists attracted by tourism/tourism

businesses?

How well are tourism/tourism businesses providing a return on investment to maintain financially

viable operations over time?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide job security?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide rates of pay commensurate with the skills and time

expectations of employees?

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide training and build careers and incentives for long term

employment?

Sustainable built and natural environments

How do tourism/tourism businesses protect and conserve the natural environment?

How do tourism businesses manage waste, reduce energy consumption and demonstrate good

environmental practices?

How do tourism/tourism businesses affect the liveable built environment?

How do tourism businesses affect private/public transport and public crowding?

Democratic and engaged communities

How do tourism/tourism businesses provide opportunities for the community to comment on their

activities?

What are the preferred tourism styles for the community considering expenditure and the influence of

different tourist markets segments across the forms of capital?

How do tourism/tourism businesses contribute to the promotion and image of the region?

8

How do tourism/tourism businesses influence the performance of the local council and its activities?

How do tourism/tourism businesses enact corporate social responsibility in terms of sponsorship and

creating community life?

What roles do tourism/individuals play in the leadership of the community?

References

Bleys, B. (2012). Beyond GDP: Classifying alternative measures for progress. Social Indicators

Research, 109, 355-376.

Brouder, P. (2012). Creative outposts: Tourism's place in rural innovation. Tourism Planning and

Development, 9(4), 383-396.

Costanza, R., Fisher, B., Ali, S., Beer, C., Bond, L., Boumans, R., et al. (2007). Quality of life: An

approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecological

Economics, 61(2-3), 267-276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.023

Gasper, D. (2010). Understanding the diversity of conceptions of well-being and quality of life. The

Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 351-360.

Grzeskowiak, S., Sirgy, M. J., & Widgery, R. (2003). Resident's satisfaction with community services:

Predictors and outcomes. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 33(2), 1-36.

Hagerty, M. R., Cummins, R. A., Ferriss, A. L., Land, K., Michalos, A. C., Peterson, M., et al. (2001).

Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators

Research, 55(1), 1-96.

Johansson, S. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring quality of life for national policy. Social

Indicators Research, 58(1-3), 13-32.

Morton, A., & Edwards, L. (2012). Community wellbeing indicators, survey template for local

government, Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government. Retrieved from

http://www.acelg.org.au/upload/program1/1367468192_LGAQ_ACELG_Community_Wellbein

g_Indicators.pdf

Nussbaum, M., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sirgy, M. (2011). Theoretical perspectives guiding QOL indicator projects. Social Indicators Research,

103(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9692-6

Sirgy, M. J., & Cornwell, T. (2001). Further validation of the Sirgy et al.'s measure of community

quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 56(2), 125-143. doi: 10.1023/A:1012254826324

How do tourism/tourism businesses influence the performance of the local council and its activities?

How do tourism/tourism businesses enact corporate social responsibility in terms of sponsorship and

creating community life?

What roles do tourism/individuals play in the leadership of the community?

References

Bleys, B. (2012). Beyond GDP: Classifying alternative measures for progress. Social Indicators

Research, 109, 355-376.

Brouder, P. (2012). Creative outposts: Tourism's place in rural innovation. Tourism Planning and

Development, 9(4), 383-396.

Costanza, R., Fisher, B., Ali, S., Beer, C., Bond, L., Boumans, R., et al. (2007). Quality of life: An

approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecological

Economics, 61(2-3), 267-276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.023

Gasper, D. (2010). Understanding the diversity of conceptions of well-being and quality of life. The

Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 351-360.

Grzeskowiak, S., Sirgy, M. J., & Widgery, R. (2003). Resident's satisfaction with community services:

Predictors and outcomes. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 33(2), 1-36.

Hagerty, M. R., Cummins, R. A., Ferriss, A. L., Land, K., Michalos, A. C., Peterson, M., et al. (2001).

Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators

Research, 55(1), 1-96.

Johansson, S. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring quality of life for national policy. Social

Indicators Research, 58(1-3), 13-32.

Morton, A., & Edwards, L. (2012). Community wellbeing indicators, survey template for local

government, Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government. Retrieved from

http://www.acelg.org.au/upload/program1/1367468192_LGAQ_ACELG_Community_Wellbein

g_Indicators.pdf

Nussbaum, M., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sirgy, M. (2011). Theoretical perspectives guiding QOL indicator projects. Social Indicators Research,

103(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9692-6

Sirgy, M. J., & Cornwell, T. (2001). Further validation of the Sirgy et al.'s measure of community

quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 56(2), 125-143. doi: 10.1023/A:1012254826324

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

9

2. Improving Cross-industry Opportunities

Both nationally and internationally, the classification of tourism as a sector by governments is highly

variable. Sometimes tourism is co-located in departments dealing with arts, culture and sport, while

on other occasions it is a part of the resources sector with links to mining, forestry and agriculture. At

the present time at the national level there is the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism while

at the state level in Queensland the sector resides in the Department of Tourism, Major Events, Small

Business and the Commonwealth Games. In the Northern Territory it is the Department of Tourism

and Major Events, and in Western Australia tourism is not specifically profiled in any departmental

title. Such variable classification underlines a potential for tourism to be more closely interwoven with

other main economic and cultural industries.

There can be creative possibilities in recognising the diversity of opportunities when sectors are

aligned in their interests of making money, building brand loyalty and providing mutual support. There

is also the important potential for some tourists to see investment possibilities in a region following

these sector based tours and experiences. Three kinds of linkages between tourism and other key

economic and cultural sectors can be identified.

There is the potential to jointly attract international and domestic tourists using more co-

operative marketing approaches.

There is a rich and largely untapped opportunity to create tourism experiences around the

operation of other economic and cultural sectors.

There is the potential for administrative sharing of resources and strategies for investment

and efficient sector management.

In tropical and northern Australia four major sectors can be considered as offering special

opportunities for closer integration with tourism using the three kinds of linkages specified. These

sectors are farming/agriculture, mining, education, and public sector management for sustainability.

These opportunities may all be seen as having both a leisure and business tourism component.

Labels do exist for these tourism categories as follows: agritourism, heritage and industrial tourism,

educational tourism, and the less well-known civic familiarisation tours. While rich possibilities can be

spelled out for all these cross industry opportunities, the links with the farming/agricultural sector can

serve to illustrate these kinds of multiple joint initiatives.

Agricultural sector activity can be the basis of organising general interest tours for a broad market

segment or highly specific technical tours for those with special interests. There is a particular set of

international opportunities here for study tours from Asian famers as well as those from India, and

North and South America. The tours may mix types of agricultural and farming operations or be

focused on one kind of production (beef, dairy, sugar, pineapples, sugar and so on). There are also

2. Improving Cross-industry Opportunities

Both nationally and internationally, the classification of tourism as a sector by governments is highly

variable. Sometimes tourism is co-located in departments dealing with arts, culture and sport, while

on other occasions it is a part of the resources sector with links to mining, forestry and agriculture. At

the present time at the national level there is the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism while

at the state level in Queensland the sector resides in the Department of Tourism, Major Events, Small

Business and the Commonwealth Games. In the Northern Territory it is the Department of Tourism

and Major Events, and in Western Australia tourism is not specifically profiled in any departmental

title. Such variable classification underlines a potential for tourism to be more closely interwoven with

other main economic and cultural industries.

There can be creative possibilities in recognising the diversity of opportunities when sectors are

aligned in their interests of making money, building brand loyalty and providing mutual support. There

is also the important potential for some tourists to see investment possibilities in a region following

these sector based tours and experiences. Three kinds of linkages between tourism and other key

economic and cultural sectors can be identified.

There is the potential to jointly attract international and domestic tourists using more co-

operative marketing approaches.

There is a rich and largely untapped opportunity to create tourism experiences around the

operation of other economic and cultural sectors.

There is the potential for administrative sharing of resources and strategies for investment

and efficient sector management.

In tropical and northern Australia four major sectors can be considered as offering special

opportunities for closer integration with tourism using the three kinds of linkages specified. These

sectors are farming/agriculture, mining, education, and public sector management for sustainability.

These opportunities may all be seen as having both a leisure and business tourism component.

Labels do exist for these tourism categories as follows: agritourism, heritage and industrial tourism,

educational tourism, and the less well-known civic familiarisation tours. While rich possibilities can be

spelled out for all these cross industry opportunities, the links with the farming/agricultural sector can

serve to illustrate these kinds of multiple joint initiatives.

Agricultural sector activity can be the basis of organising general interest tours for a broad market

segment or highly specific technical tours for those with special interests. There is a particular set of

international opportunities here for study tours from Asian famers as well as those from India, and

North and South America. The tours may mix types of agricultural and farming operations or be

focused on one kind of production (beef, dairy, sugar, pineapples, sugar and so on). There are also

10

substantial opportunities to have informed public education and interest guided tours of these rural

sector activities. In some cases the sampling of products and the purchase of souvenirs or discounted

items from the production source can be incorporated in tours and day long visits. Accommodation

options are also possible in the agricultural/farming sector and the existing farm tourism and rural

retreat business can be expanded into both the budget market such as the provision of caravan and

low cost accommodation sites through to luxury retreats. Some of these ideas were captured in the

academic literature some time ago using terms such as ‘sideline tourism’. The approach is reinforced

by other themes mentioned in this document including slow tourism and reinforcing the natural brand

of the region.

There is a lack of structured tourism opportunities in these crossover spaces. There is some existing

development in the agri-tourism space. Coffee, tea, and cheese/chocolate focused sites and

experiences are available. There is some museum based tourist activity for the sugar and dairy

industries in northern Queensland. There are, however, limited opportunities to visit or understand

mining sites or production processes. The opportunities which do exist are historical or heritage

based. Similarly, there is no systematic tour or way to visit university campuses, yet arguably there is

much public and special interest in the campuses at Darwin, Townsville and Cairns. Despite a well-

recognised and often praised management regime, there are no technical and professional tours of

the management agencies, functions and operations pertaining to the World Heritage sites and

natural landscapes. Similarly there are very limited tourist experiences interpreting and explaining the

defence force presence in northern Australia.

All these kinds of activities have to be created afresh on each occasion. The organisation machinery

for visitor experiences, both at the broad public and professional interest levels do not exist in tropical

Australia. By way of contrast the wine industry in southern Australia has a well-developed visitor

profile and technical tours for professionals. Internationally, visitor centres at and tours of universities

are also well-developed tourist experiences. Mine tours in Mt Isa and Broome represent two of the

limited opportunities to appreciate the scale of Australia’s operations in this sector. The limitations of

the current product and experience offerings in this cross-over space among industry sectors is

especially well confirmed by the point that no tours of the mining, agricultural and farming sector can

be purchased in such pivotal regional centres as Charters Towers, Atherton, Mareeba, Ingham or

Kununurra.

The initiative to build cross sector opportunities can be facilitated in multiple ways. As a start-up

activity public relations and government personnel from different sectors - mining, agriculture,

education, environmental management, and tourism could convene to examine opportunities for

cooperation. A detailed assessment of what kinds of tourist demand exists and what kinds of

opportunities could be developed represent a part of this agenda. There might be possibilities for the

creation of new positions or additional job roles from these discussions. Further items on the meeting

agenda for such cooperative activity could include facilitating the promotion of technical tour

opportunities, planning itineraries of tour groups, and providing language and logistical support,

substantial opportunities to have informed public education and interest guided tours of these rural

sector activities. In some cases the sampling of products and the purchase of souvenirs or discounted

items from the production source can be incorporated in tours and day long visits. Accommodation

options are also possible in the agricultural/farming sector and the existing farm tourism and rural

retreat business can be expanded into both the budget market such as the provision of caravan and

low cost accommodation sites through to luxury retreats. Some of these ideas were captured in the

academic literature some time ago using terms such as ‘sideline tourism’. The approach is reinforced

by other themes mentioned in this document including slow tourism and reinforcing the natural brand

of the region.

There is a lack of structured tourism opportunities in these crossover spaces. There is some existing

development in the agri-tourism space. Coffee, tea, and cheese/chocolate focused sites and

experiences are available. There is some museum based tourist activity for the sugar and dairy

industries in northern Queensland. There are, however, limited opportunities to visit or understand

mining sites or production processes. The opportunities which do exist are historical or heritage

based. Similarly, there is no systematic tour or way to visit university campuses, yet arguably there is

much public and special interest in the campuses at Darwin, Townsville and Cairns. Despite a well-

recognised and often praised management regime, there are no technical and professional tours of

the management agencies, functions and operations pertaining to the World Heritage sites and

natural landscapes. Similarly there are very limited tourist experiences interpreting and explaining the

defence force presence in northern Australia.

All these kinds of activities have to be created afresh on each occasion. The organisation machinery

for visitor experiences, both at the broad public and professional interest levels do not exist in tropical

Australia. By way of contrast the wine industry in southern Australia has a well-developed visitor

profile and technical tours for professionals. Internationally, visitor centres at and tours of universities

are also well-developed tourist experiences. Mine tours in Mt Isa and Broome represent two of the

limited opportunities to appreciate the scale of Australia’s operations in this sector. The limitations of

the current product and experience offerings in this cross-over space among industry sectors is

especially well confirmed by the point that no tours of the mining, agricultural and farming sector can

be purchased in such pivotal regional centres as Charters Towers, Atherton, Mareeba, Ingham or

Kununurra.

The initiative to build cross sector opportunities can be facilitated in multiple ways. As a start-up

activity public relations and government personnel from different sectors - mining, agriculture,

education, environmental management, and tourism could convene to examine opportunities for

cooperation. A detailed assessment of what kinds of tourist demand exists and what kinds of

opportunities could be developed represent a part of this agenda. There might be possibilities for the

creation of new positions or additional job roles from these discussions. Further items on the meeting

agenda for such cooperative activity could include facilitating the promotion of technical tour

opportunities, planning itineraries of tour groups, and providing language and logistical support,

11

including attending to occupational health and safety issues. There is also a clear link to creating

conferences and bidding for meetings and events associated with these tour groups.

References

Buultjens, J., Brereton, D., Memmott, P., Reser, J., Thomson, L., & O'Rourke, T. (2010). The mining

sector and indigenous tourism development in Weipa, Queensland. Tourism Management,

31(5), 597-606. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.009

Cox, L. J., & Fox, M. (1991). Agriculturally based leisure attractions. Journal of Tourism Studies, 2(2),

18-27.

Getz, D. (2007). Event studies theory, research and policy for planned events. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Getz, D., Carlsen, J., & Morrison, A. (2004). The family business in tourism and hospitality.

Wallingford: CABI.

Gil Arroyo, C., Barbieri, C., & Rozier Rich, S. (2013). Defining agritourism: A comparative study of

stakeholders' perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tourism Management, 37, 39-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.007

Kelly, I. (1997). Study tours: A model for ‘benign’ tourism? Journal of Tourism Studies, 8(1), 42-51.

Kelly, I., & Dixon, W. (1991). Sideline tourism. Journal of Tourism Studies, 2(1), 21-28.

Morrison, A. M., Pearce, P. L., Moscardo, G., Nadkarni, N., & O'Leary, J. T. (1996). Specialist

accommodation: Definitions, markets served, and roles in tourism development. Journal of

Travel Research, 35(1), 18-26.

Tew, C., & Barbieri, C. (2012). The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective.

Tourism Management, 33(1), 215-224. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.005

White, L. (2013). Sugarcane and the sugar train: Linking tradition, trade, and tourism in the tropical

north Queensland. In L. Jolliffe (Ed.), Sugar heritage and tourism in transition (pp. 175-188).

Bristol: Channel View Publication.

including attending to occupational health and safety issues. There is also a clear link to creating

conferences and bidding for meetings and events associated with these tour groups.

References

Buultjens, J., Brereton, D., Memmott, P., Reser, J., Thomson, L., & O'Rourke, T. (2010). The mining

sector and indigenous tourism development in Weipa, Queensland. Tourism Management,

31(5), 597-606. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.009

Cox, L. J., & Fox, M. (1991). Agriculturally based leisure attractions. Journal of Tourism Studies, 2(2),

18-27.

Getz, D. (2007). Event studies theory, research and policy for planned events. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Getz, D., Carlsen, J., & Morrison, A. (2004). The family business in tourism and hospitality.

Wallingford: CABI.

Gil Arroyo, C., Barbieri, C., & Rozier Rich, S. (2013). Defining agritourism: A comparative study of

stakeholders' perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tourism Management, 37, 39-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.007

Kelly, I. (1997). Study tours: A model for ‘benign’ tourism? Journal of Tourism Studies, 8(1), 42-51.

Kelly, I., & Dixon, W. (1991). Sideline tourism. Journal of Tourism Studies, 2(1), 21-28.

Morrison, A. M., Pearce, P. L., Moscardo, G., Nadkarni, N., & O'Leary, J. T. (1996). Specialist

accommodation: Definitions, markets served, and roles in tourism development. Journal of

Travel Research, 35(1), 18-26.

Tew, C., & Barbieri, C. (2012). The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective.

Tourism Management, 33(1), 215-224. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.005

White, L. (2013). Sugarcane and the sugar train: Linking tradition, trade, and tourism in the tropical

north Queensland. In L. Jolliffe (Ed.), Sugar heritage and tourism in transition (pp. 175-188).

Bristol: Channel View Publication.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

12

3. Reinforcing the Well Managed Natural Brand

The key theme of this initiative is the extension of current tropical marketing and regional presentation

efforts. The substantive tourism marketing direction for the future emphasises natural features of the

tropics supported by a high level of visible and effective management for sustainability.

The continuing pursuit of a strong emphasis on marketing the natural attributes of the tropics is

consistent with three large trends repeatedly itemised in the international academic tourism literature.

Globally and especially in the key markets of interest to Australia’s tropics, urbanisation is a key trend.

Few international tourists from European and Asian and North American markets come from low

population towns and villages and most are accustomed to an urban way of life. Even for the

Australian domestic market the population densities in tropical Australian cities and towns are seen as

low. In this context the smaller communities and natural features of the tropics represent contrasting

social, visual and experiential landscapes. These kinds of contrasts represent opportunities for

memorable natural environment engagement in the experience economy.

Secondly, travel is increasingly seen as a required component of contemporary life. Repeat

international visitors to Australia have outnumbered first time visitors since 1998. Further travel in

Australia throughout the tropics and its environments and societies thus represents the second or

third visit opportunity for many international tourists. Australian travellers, too, are often repeat

visitors, especially in the senior recreational vehicle market, and promoting the diversity of tropical

destinations is very relevant to this domestic market base.

The third global trend reflected in much writing about tourism demand issues is a mounting

awareness of green or sustainability issues. Characterised as a third force influencing many

consumer choices (price and quality take precedence), a desire to visit environmentally special and

well managed settings supports a continuing emphasis on a marketing approach built on natural

attributes.

A strong tourism marketing emphasis on stressing the environmental attributes of the tropics with

three world heritage areas and four national landscapes is hardly surprising. There is, however, a

second key component of this continuing activity which requires the joint efforts of local councils, and

managers of natural settings as well as tourism businesses. Visiting special natural environments and

staying in such locations acts as a sensitisation force and creates visitor awareness, even a picayune

critical focus, on how the environment is being managed in day to day operational ways. The natural

environment focus in marketing the tropics represents what Esty and Winston (2009) label a “high

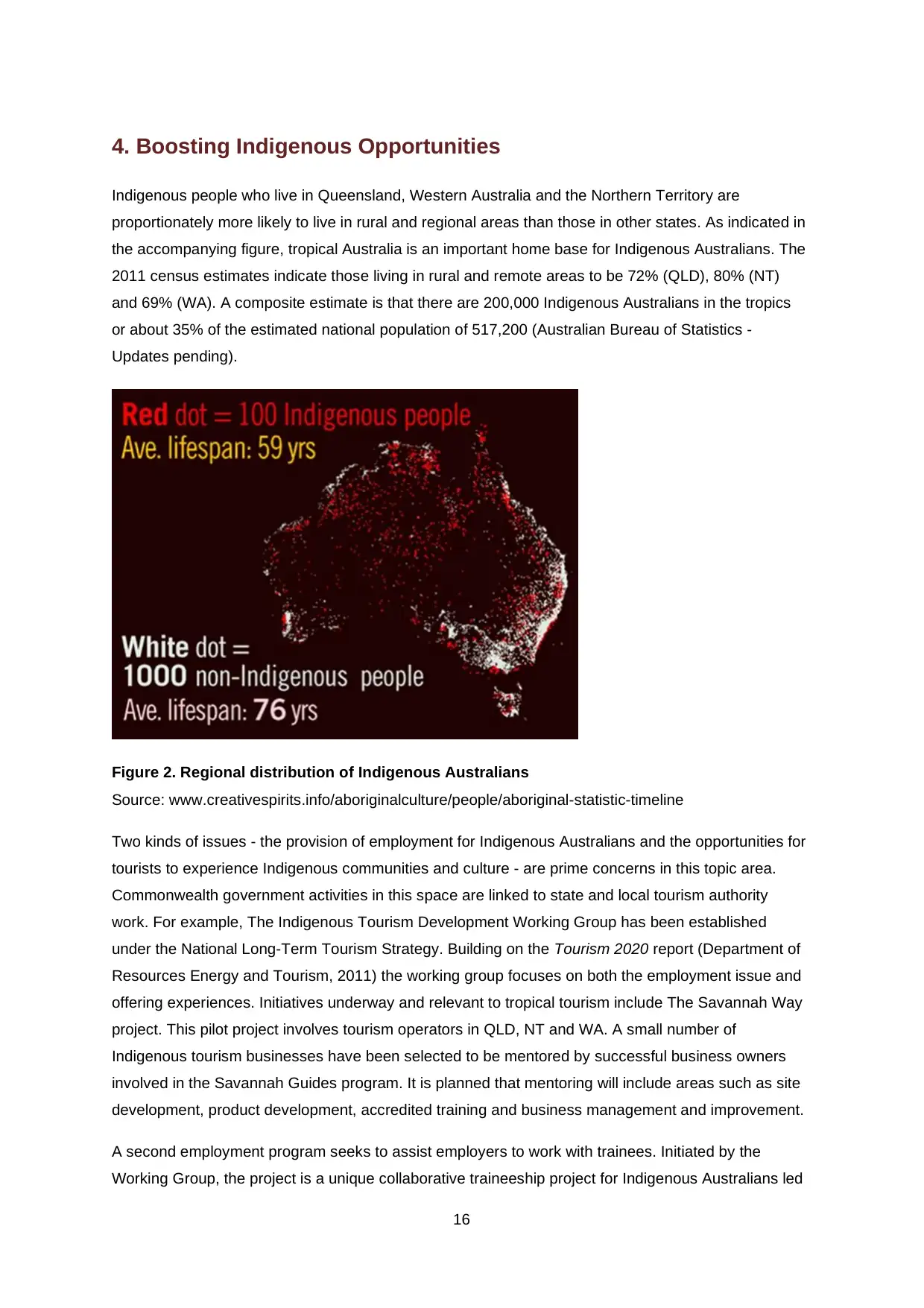

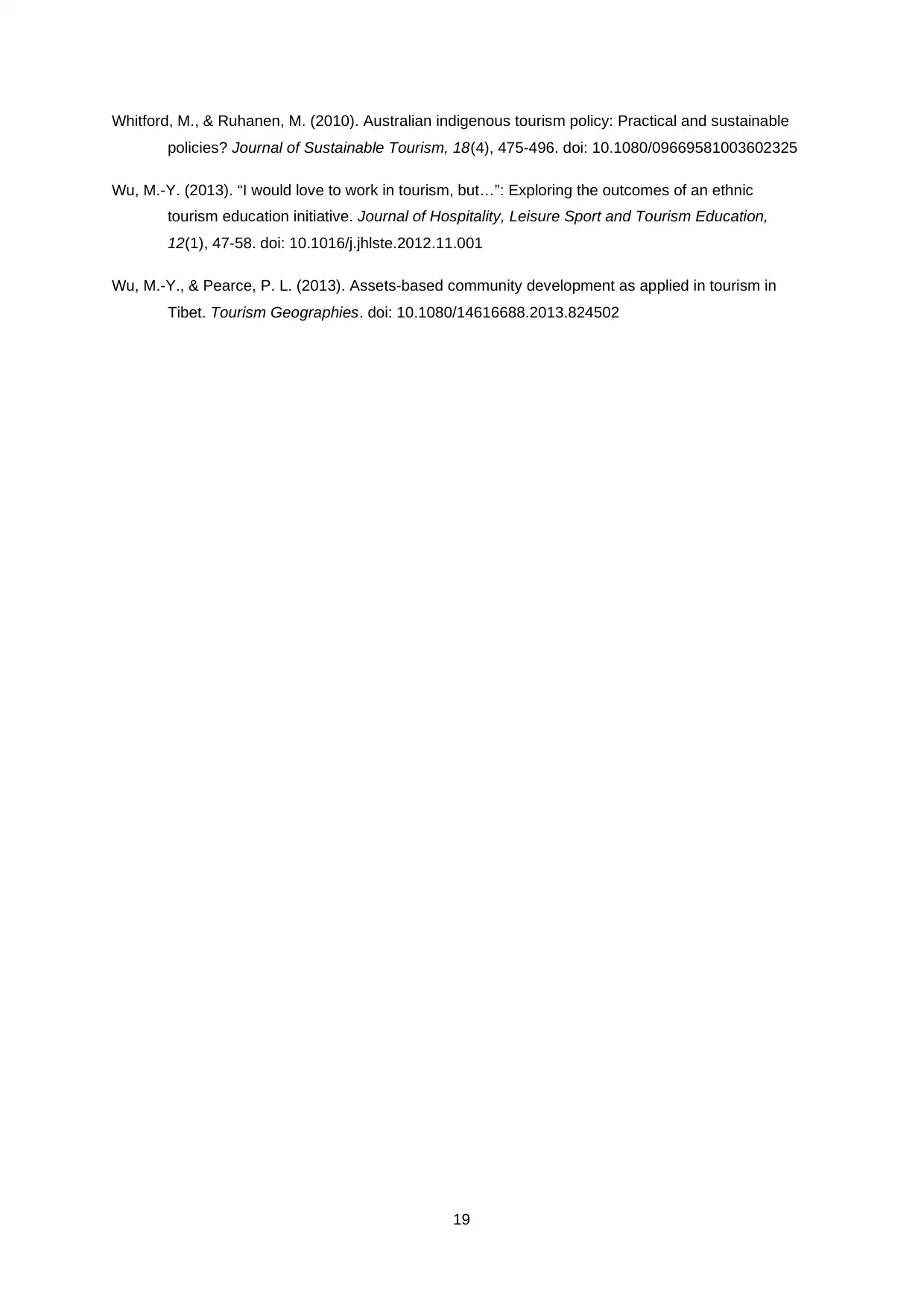

exposure approach”. Promoting the natural features of tropical Australia is at risk if the thorough