International Journal of Social Psychiatry Impact Factor

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/07

|8

|7638

|19

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

International Journal of

Social Psychiatry

2016, Vol. 62(2) 133 –140

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0020764015607550

isp.sagepub.com

E CAMDEN SCHIZOPH

Introduction

Cross-cultural comparison tests the boundaries of

knowledge and stretches methodological parameters,

highlights important similarities and differences and

promotes institutional and intercultural exchange and

understanding (Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011). This

article looks at these matters in relation to the concept

The social and community opportunities

profile social inclusion measure: Structural

equivalence and differential item

functioning in community mental

health residents in Hong Kong

and the United Kingdom

Peter John Huxley1, Kara Chan2, Marcus Chiu3, Yanni Ma2,

Sarah Gaze4 and Sherrill Evans5

Abstract

Introduction: China’s future major health problem will be the management of chronic diseases – of which

health is a major one. An instrument is needed to measure mental health inclusion outcomes for mental he

in Hong Kong and mainland China as they strive to promote a more inclusive society for their citizens and

disadvantaged groups.

Aim: To report on the analysis of structural equivalence and item differentiation in two mentally unhealthy

healthy sample in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong.

Method: The mental health sample in Hong Kong was made up of non-governmental organisation (NGO) r

meeting the selection/exclusion criteria (being well enough to be interviewed, having a formal psychiatric d

living in the community). A similar sample in the United Kingdom meeting the same selection criteria was o

a community mental health organisation, equivalent to the NGOs in Hong Kong. Exploratory factor analysis

regression were conducted.

Results: The single-variable, self-rated ‘overall social inclusion’ differs significantly between all of the sam

we would expect from previous research, with the healthy population feeling more included than the seriou

illness (SMI) groups. In the exploratory factor analysis, the first two factors explain between a third and hal

variance, and the single variable which enters into all the analyses in the first factor is having friends to vis

the regression models were significant; however, in Hong Kong sample, only one-fifth of the total variance

Conclusion: The structural findings imply that the social and community opportunities profile–Chin

(SCOPE-C) gives similar results when applied to another culture. As only one-fifth of the variance of ‘overal

was explained in the Hong Kong sample, it may be that the instrument needs to be refined using different

items within the structural domains of inclusion.

Keywords

Severe mental illness, social exclusion, health assessment, social policy

1 Centre for Mental Health and Society, School of Social Sciences,

Bangor University, Bangor, Wales

2 School of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon

Tong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Social Work, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences,

National University of Singapore, Singapore

607550 ISP0010.1177/0020764015607550International Journal of Social Psychiatry Huxley et al.

research-article 2015

Original Article

4 School of Medicine, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales

5Independent Consultant, Pembrokeshire, Wales

Corresponding author:

Peter John Huxley, Centre for Mental Health and Society, School of Soc

Sciences, Bangor University, College Road, Bangor, Wales LL57 2DG.

Email: P.Huxley@bangor.ac.uk

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Social Psychiatry

2016, Vol. 62(2) 133 –140

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0020764015607550

isp.sagepub.com

E CAMDEN SCHIZOPH

Introduction

Cross-cultural comparison tests the boundaries of

knowledge and stretches methodological parameters,

highlights important similarities and differences and

promotes institutional and intercultural exchange and

understanding (Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011). This

article looks at these matters in relation to the concept

The social and community opportunities

profile social inclusion measure: Structural

equivalence and differential item

functioning in community mental

health residents in Hong Kong

and the United Kingdom

Peter John Huxley1, Kara Chan2, Marcus Chiu3, Yanni Ma2,

Sarah Gaze4 and Sherrill Evans5

Abstract

Introduction: China’s future major health problem will be the management of chronic diseases – of which

health is a major one. An instrument is needed to measure mental health inclusion outcomes for mental he

in Hong Kong and mainland China as they strive to promote a more inclusive society for their citizens and

disadvantaged groups.

Aim: To report on the analysis of structural equivalence and item differentiation in two mentally unhealthy

healthy sample in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong.

Method: The mental health sample in Hong Kong was made up of non-governmental organisation (NGO) r

meeting the selection/exclusion criteria (being well enough to be interviewed, having a formal psychiatric d

living in the community). A similar sample in the United Kingdom meeting the same selection criteria was o

a community mental health organisation, equivalent to the NGOs in Hong Kong. Exploratory factor analysis

regression were conducted.

Results: The single-variable, self-rated ‘overall social inclusion’ differs significantly between all of the sam

we would expect from previous research, with the healthy population feeling more included than the seriou

illness (SMI) groups. In the exploratory factor analysis, the first two factors explain between a third and hal

variance, and the single variable which enters into all the analyses in the first factor is having friends to vis

the regression models were significant; however, in Hong Kong sample, only one-fifth of the total variance

Conclusion: The structural findings imply that the social and community opportunities profile–Chin

(SCOPE-C) gives similar results when applied to another culture. As only one-fifth of the variance of ‘overal

was explained in the Hong Kong sample, it may be that the instrument needs to be refined using different

items within the structural domains of inclusion.

Keywords

Severe mental illness, social exclusion, health assessment, social policy

1 Centre for Mental Health and Society, School of Social Sciences,

Bangor University, Bangor, Wales

2 School of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon

Tong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Social Work, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences,

National University of Singapore, Singapore

607550 ISP0010.1177/0020764015607550International Journal of Social Psychiatry Huxley et al.

research-article 2015

Original Article

4 School of Medicine, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales

5Independent Consultant, Pembrokeshire, Wales

Corresponding author:

Peter John Huxley, Centre for Mental Health and Society, School of Soc

Sciences, Bangor University, College Road, Bangor, Wales LL57 2DG.

Email: P.Huxley@bangor.ac.uk

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

134 International Journal of Social Psychiatry 62(2)

of social inclusion in the United Kingdom and Hong

Kong (HK).

A considerable amount of the literature about social

inclusion is actually about social exclusion (e.g. Leff &

Warner, 2006), and some treat social inclusion as if it is only

the converse of social exclusion (Wright & Stickley, 2013).

Repper and Perkins (2003) among others take the view that

social exclusion focuses on negatives and deficits, whereas

social inclusion is about affirmative action to address those

factors that lead to exclusion. In the United States, this

change in focus has taken place over the past 10 years

(Boushey, Fremstad, Gragg, & Waller, 2007). Social inclu-

sion has been defined in the European Union (EU) as

A process which ensures that those at risk of poverty and

social exclusion gain the opportunities and resources

necessary to participate fully in economic, social and cultural

life and to enjoy a standard of living and wellbeing that is

considered normal in the society in which they live. It ensures

that they have greater participation in decision-making which

affects their lives and access to their fundamental rights (as

defined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU).

(Council for the European Union, 2003)

The aim of the social inclusion policy in the EU is ‘to pre-

vent and eradicate poverty and exclusion and promote the

integration and participation of all into economic and

social life’ (Commission of the European Communities,

2000). In 2008, Mental Health Europe produced a descrip-

tive report from 27 member states (including Scotland and

Ireland, but not England or Wales) on the outcome of its

work programme on social inclusion for people with men-

tal health problems (Mental Health Europe, 2008)

Curran, Burchardt, Knapp, Mcdaid, and Li (2007) identi-

fied two broad schools of thought in the social inclusion lit-

erature. The first may be called a rights-based approach in

which social inclusion reflects the rights as a member or a

citizen of a particular group, community, society or country.

The second approach starts from the assumption that social

inclusion is the opportunity to participate in key functions or

activities of the society in question. This approach is a

development of the traditional concerns of social science

and especially social policy: measuring poverty and multi-

ple deprivation (Gordon, 2000; Townsend, 1979). Rights-

based conceptions of social inclusion may be particularly

important in the context of mental health, as a denial of

rights and/or access to the means to realise entitlements has

historically been a feature of the treatment of people with

mental illness. Conceptions of social inclusion based on par-

ticipation are also important, however, especially where

comparisons with the general population are sought.

Curran argues that social inclusion is widely agreed to

be

•• Relative to a given society (place and time);

•• Multidimensional (whether those dimensions are

conceived in terms of rights or key activities);

•• Dynamic (because inclusion is a process rather than

a state);

•• Mtilayered (in the sense that its causes operate at

individual, familial, communal, societal and even

global levels).

Cultural contexts

Hong Kong, officially known as Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China,

is a city state with a high degree of autonomy on the south-

ern coast of China at the Pearl River Estuary and the South

China Sea. HK has 7 million inhabitants over a land mass

of over 400 square miles. In all, 94% of the current popula-

tion of HK are ethnic Chinese. A major part of HK’s

Cantonese-speaking majority originated from the neigh-

bouring Canton province (now Guangdong), migrating to

HK during the 1960s. On the whole, HK psychiatry has

been fashioned close to the British model in terms of its

legal framework, guiding theoretical principles, diagnosis

and management of psychiatric disorders and types of ser-

vice delivery (Ungvari & Chiu, 2004). These aspects of

mental health have not changed since 1997, when HK

became a Special Administrative Region of China. From

its inception in 1967, when the first halfway house opened,

community-based residential rehabilitation has mainly

been the task of non-governmental organisation (NGO) in

collaboration with the Department of Social Welfare and

aided by the psychiatric services.

Over the last 10 years, there has been increasing activity

to improve the disability rights and well-being of the

Chinese population, and this has taken place against a very

gradual shift from collectivism to individualism

(Luhrmann, 2014; Steele & Lynch, 2013). Fisher and Jing

(2008) argue that despite strong statements on disability

rights in Chinese legislation since 1990, the independent

living policy falls short of the social inclusion goals

expected from such a policy commitment. They conclude

that minimum income support and the introduction of

social services are slowly addressing the social inclusion

of disabled people in China.

The World Bank has suggested that China’s major

health challenge for the future is the care and treatment of

people with non-communicable chronic physical and men-

tal diseases. In Toward a Healthy and Harmonious Life in

China (Wang, Marquez, & Langenbrunner, 2011), the

World Bank urged China to step up efforts to tackle its ris-

ing tide of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), warning

of not only the social but also the economic consequences

of inaction. NCDs are China’s number 1 health threat, con-

tributing to more than 80% of the country’s 10·3 million

annual deaths and nearly 70% of its total disease burden.

In HK, where social services are considered one of the

most well developed when compared to other parts of

China, the inclusion spirit has never been stronger. In

2011, the Community Investment and Inclusion Fund

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

of social inclusion in the United Kingdom and Hong

Kong (HK).

A considerable amount of the literature about social

inclusion is actually about social exclusion (e.g. Leff &

Warner, 2006), and some treat social inclusion as if it is only

the converse of social exclusion (Wright & Stickley, 2013).

Repper and Perkins (2003) among others take the view that

social exclusion focuses on negatives and deficits, whereas

social inclusion is about affirmative action to address those

factors that lead to exclusion. In the United States, this

change in focus has taken place over the past 10 years

(Boushey, Fremstad, Gragg, & Waller, 2007). Social inclu-

sion has been defined in the European Union (EU) as

A process which ensures that those at risk of poverty and

social exclusion gain the opportunities and resources

necessary to participate fully in economic, social and cultural

life and to enjoy a standard of living and wellbeing that is

considered normal in the society in which they live. It ensures

that they have greater participation in decision-making which

affects their lives and access to their fundamental rights (as

defined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU).

(Council for the European Union, 2003)

The aim of the social inclusion policy in the EU is ‘to pre-

vent and eradicate poverty and exclusion and promote the

integration and participation of all into economic and

social life’ (Commission of the European Communities,

2000). In 2008, Mental Health Europe produced a descrip-

tive report from 27 member states (including Scotland and

Ireland, but not England or Wales) on the outcome of its

work programme on social inclusion for people with men-

tal health problems (Mental Health Europe, 2008)

Curran, Burchardt, Knapp, Mcdaid, and Li (2007) identi-

fied two broad schools of thought in the social inclusion lit-

erature. The first may be called a rights-based approach in

which social inclusion reflects the rights as a member or a

citizen of a particular group, community, society or country.

The second approach starts from the assumption that social

inclusion is the opportunity to participate in key functions or

activities of the society in question. This approach is a

development of the traditional concerns of social science

and especially social policy: measuring poverty and multi-

ple deprivation (Gordon, 2000; Townsend, 1979). Rights-

based conceptions of social inclusion may be particularly

important in the context of mental health, as a denial of

rights and/or access to the means to realise entitlements has

historically been a feature of the treatment of people with

mental illness. Conceptions of social inclusion based on par-

ticipation are also important, however, especially where

comparisons with the general population are sought.

Curran argues that social inclusion is widely agreed to

be

•• Relative to a given society (place and time);

•• Multidimensional (whether those dimensions are

conceived in terms of rights or key activities);

•• Dynamic (because inclusion is a process rather than

a state);

•• Mtilayered (in the sense that its causes operate at

individual, familial, communal, societal and even

global levels).

Cultural contexts

Hong Kong, officially known as Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China,

is a city state with a high degree of autonomy on the south-

ern coast of China at the Pearl River Estuary and the South

China Sea. HK has 7 million inhabitants over a land mass

of over 400 square miles. In all, 94% of the current popula-

tion of HK are ethnic Chinese. A major part of HK’s

Cantonese-speaking majority originated from the neigh-

bouring Canton province (now Guangdong), migrating to

HK during the 1960s. On the whole, HK psychiatry has

been fashioned close to the British model in terms of its

legal framework, guiding theoretical principles, diagnosis

and management of psychiatric disorders and types of ser-

vice delivery (Ungvari & Chiu, 2004). These aspects of

mental health have not changed since 1997, when HK

became a Special Administrative Region of China. From

its inception in 1967, when the first halfway house opened,

community-based residential rehabilitation has mainly

been the task of non-governmental organisation (NGO) in

collaboration with the Department of Social Welfare and

aided by the psychiatric services.

Over the last 10 years, there has been increasing activity

to improve the disability rights and well-being of the

Chinese population, and this has taken place against a very

gradual shift from collectivism to individualism

(Luhrmann, 2014; Steele & Lynch, 2013). Fisher and Jing

(2008) argue that despite strong statements on disability

rights in Chinese legislation since 1990, the independent

living policy falls short of the social inclusion goals

expected from such a policy commitment. They conclude

that minimum income support and the introduction of

social services are slowly addressing the social inclusion

of disabled people in China.

The World Bank has suggested that China’s major

health challenge for the future is the care and treatment of

people with non-communicable chronic physical and men-

tal diseases. In Toward a Healthy and Harmonious Life in

China (Wang, Marquez, & Langenbrunner, 2011), the

World Bank urged China to step up efforts to tackle its ris-

ing tide of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), warning

of not only the social but also the economic consequences

of inaction. NCDs are China’s number 1 health threat, con-

tributing to more than 80% of the country’s 10·3 million

annual deaths and nearly 70% of its total disease burden.

In HK, where social services are considered one of the

most well developed when compared to other parts of

China, the inclusion spirit has never been stronger. In

2011, the Community Investment and Inclusion Fund

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Huxley et al. 135

funded projects to the tune of more than 30 million HK

dollars. Nevertheless, there is a lack of a valid measure to

evaluate the objective of improved social inclusion in HK.

Not only will developing a valid inclusion measure help to

augment the evidence base about the inclusion of ethnic

groups and disabled groups, but it may also be used to

demonstrate the inclusion efficacy of service programmes.

Such a development could have the great potential for pro-

gramme evaluation at local (HK) level and for extended

application to mainland China and other Chinese commu-

nities where inclusion/exclusion issues remain very chal-

lenging (Blaxland, Fisher, & Shang, 2015).

Cross-cultural measurement issues

Interest in cross-cultural measurement issues has grown

rapidly since the turn of the century. Although psycholo-

gists have taken the lead on measurement issues

(Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011), social work research-

ers have recognised the importance of developing cross-

cultural measurement for the profession, especially for

work with minority and immigrant groups (Tran, 2009)

including marginalised Asian immigrants (Willgerodt,

Kataoka-Yahiro, Kim, & Ceria, 2005). Both professions

recognise the same bias and equivalence issues in cross-

cultural measurement (Matsumoto & Van de Vijver,

2011; Tran, 2009).

Issues of equivalence.There are many types of cross-cultural

research. Herdman, Fox-Rushby, and Badia (1998) listed 19

types; others have suggested that there are perhaps as many

as 50 (Johnson, Shavitt, & Holbrook, 2011). Most authors

agree on five or six fundamental ones: these include concep-

tual, item, semantic, operational, metric or measurement

unit, structural and functional equivalence (Berg, Jahnsen,

Holm, & Hussain, 2003; Herdman et al., 1998; Lee & Jung,

2006; Mahler, Jank, Reuschenbach, & Szecsenyi, 2009;

Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011; Streiner & Norman,

2008; Tran, 2009; Van Widenfelt, Treffers, De Beurs, Siebe-

link, & Koudijs, 2005).

In essence, these look at whether the construct is con-

ceptualised in the same way in different cultures, whether

it consists of the same constituent elements and whether its

relation with other constructs is the same. Structure-

oriented studies (such as reported here) focus mainly on

the consistency of relationships among variables and

between measures in more than one culture. Fischer and

Fontaine (2011) distinguish four levels of equivalence:

functional, structural, metric and full score equivalence.

They define structural equivalence as ‘the same underly-

ing dimensions emerge and item responses are not trivially

related to these dimensions in each of the cultural groups’.

It has been suggested that there has been a misguided

pre-occupation with scales rather than the concepts being

scaled and too much reliance on unsubstantiated claims of

conceptual equivalence between them (Bowden & Fox-

Rushby, 2003). The same issue arises in relation to the

cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life

(HRQOL) instruments (Cheung & Thumboo, 2006). The

approach we take to the question of conceptual equiva-

lence between cultures is universalist rather than absolutist

(Herdman et al., 1998). This approach does not make the

prior assumption that constructs will be the same across

cultures and, consequently, implies a need to establish

whether the concept exists and is interpreted similarly in

the two settings.

The development of social and community

opportunities profile–Chinese version

In previous work, we have reported on the conceptual

equivalence of the concept in the United Kingdom and in

HK (Chan, Evans, Ng, Chiu, & Huxley, 2014). A focus

group study involving concept mapping was conducted in

HK during September to October 2012. The objective of the

study was to investigate how the concepts of social inclu-

sion are understood by HK residents. Seven groups of 61

participants (38 females and 23 males) were interviewed,

including separate groups of non-professional workers at a

service centre, senior centre users, a mixed group of parents

as well as community residents, persons with severe mental

illness, professional social service providers, communica-

tion studies students and social work students. Six major

themes were identified by these groups: (1) material

resources and wealth, (2) work, (3) social (dis)harmony and

diversity, (4) discrimination, (5) communication and (6)

participation in activities. HK respondents gave more prom-

inence to issues of stigma and discrimination than UK

respondents, so further items were introduced into the social

and community opportunities profile–Chinese version

(SCOPE-C). Translation and back translation of the other

SCOPE domains were undertaken as per the research proto-

col. As a result, certain variables within domains were

replaced by HK-specific items and codes based upon the

HK population census questions and coding.

The SCOPE-C was then pilot tested for acceptability

and clarity among a group of professionals and NGO

patients. No further amendments were deemed necessary.

The SCOPE-C was then applied to the sample of NGO

patients at baseline and 2 weeks later to assess test–retest

reliability and then again after 6 months to assess change.

The main mental health sample in HK was made up of

NGO patients meeting the selection/exclusion criteria (see

section ‘Method’). A similar sample in the United Kingdom

meeting the same selection criteria was obtained from a

community mental health organisation, equivalent to the

NGOs in HK. In both samples, the main diagnosis was

psychosis, and individuals were still receiving psychiatric

services while resident in the community. The mental

health samples were collected contemporaneously in late

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

funded projects to the tune of more than 30 million HK

dollars. Nevertheless, there is a lack of a valid measure to

evaluate the objective of improved social inclusion in HK.

Not only will developing a valid inclusion measure help to

augment the evidence base about the inclusion of ethnic

groups and disabled groups, but it may also be used to

demonstrate the inclusion efficacy of service programmes.

Such a development could have the great potential for pro-

gramme evaluation at local (HK) level and for extended

application to mainland China and other Chinese commu-

nities where inclusion/exclusion issues remain very chal-

lenging (Blaxland, Fisher, & Shang, 2015).

Cross-cultural measurement issues

Interest in cross-cultural measurement issues has grown

rapidly since the turn of the century. Although psycholo-

gists have taken the lead on measurement issues

(Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011), social work research-

ers have recognised the importance of developing cross-

cultural measurement for the profession, especially for

work with minority and immigrant groups (Tran, 2009)

including marginalised Asian immigrants (Willgerodt,

Kataoka-Yahiro, Kim, & Ceria, 2005). Both professions

recognise the same bias and equivalence issues in cross-

cultural measurement (Matsumoto & Van de Vijver,

2011; Tran, 2009).

Issues of equivalence.There are many types of cross-cultural

research. Herdman, Fox-Rushby, and Badia (1998) listed 19

types; others have suggested that there are perhaps as many

as 50 (Johnson, Shavitt, & Holbrook, 2011). Most authors

agree on five or six fundamental ones: these include concep-

tual, item, semantic, operational, metric or measurement

unit, structural and functional equivalence (Berg, Jahnsen,

Holm, & Hussain, 2003; Herdman et al., 1998; Lee & Jung,

2006; Mahler, Jank, Reuschenbach, & Szecsenyi, 2009;

Matsumoto & Van de Vijver, 2011; Streiner & Norman,

2008; Tran, 2009; Van Widenfelt, Treffers, De Beurs, Siebe-

link, & Koudijs, 2005).

In essence, these look at whether the construct is con-

ceptualised in the same way in different cultures, whether

it consists of the same constituent elements and whether its

relation with other constructs is the same. Structure-

oriented studies (such as reported here) focus mainly on

the consistency of relationships among variables and

between measures in more than one culture. Fischer and

Fontaine (2011) distinguish four levels of equivalence:

functional, structural, metric and full score equivalence.

They define structural equivalence as ‘the same underly-

ing dimensions emerge and item responses are not trivially

related to these dimensions in each of the cultural groups’.

It has been suggested that there has been a misguided

pre-occupation with scales rather than the concepts being

scaled and too much reliance on unsubstantiated claims of

conceptual equivalence between them (Bowden & Fox-

Rushby, 2003). The same issue arises in relation to the

cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life

(HRQOL) instruments (Cheung & Thumboo, 2006). The

approach we take to the question of conceptual equiva-

lence between cultures is universalist rather than absolutist

(Herdman et al., 1998). This approach does not make the

prior assumption that constructs will be the same across

cultures and, consequently, implies a need to establish

whether the concept exists and is interpreted similarly in

the two settings.

The development of social and community

opportunities profile–Chinese version

In previous work, we have reported on the conceptual

equivalence of the concept in the United Kingdom and in

HK (Chan, Evans, Ng, Chiu, & Huxley, 2014). A focus

group study involving concept mapping was conducted in

HK during September to October 2012. The objective of the

study was to investigate how the concepts of social inclu-

sion are understood by HK residents. Seven groups of 61

participants (38 females and 23 males) were interviewed,

including separate groups of non-professional workers at a

service centre, senior centre users, a mixed group of parents

as well as community residents, persons with severe mental

illness, professional social service providers, communica-

tion studies students and social work students. Six major

themes were identified by these groups: (1) material

resources and wealth, (2) work, (3) social (dis)harmony and

diversity, (4) discrimination, (5) communication and (6)

participation in activities. HK respondents gave more prom-

inence to issues of stigma and discrimination than UK

respondents, so further items were introduced into the social

and community opportunities profile–Chinese version

(SCOPE-C). Translation and back translation of the other

SCOPE domains were undertaken as per the research proto-

col. As a result, certain variables within domains were

replaced by HK-specific items and codes based upon the

HK population census questions and coding.

The SCOPE-C was then pilot tested for acceptability

and clarity among a group of professionals and NGO

patients. No further amendments were deemed necessary.

The SCOPE-C was then applied to the sample of NGO

patients at baseline and 2 weeks later to assess test–retest

reliability and then again after 6 months to assess change.

The main mental health sample in HK was made up of

NGO patients meeting the selection/exclusion criteria (see

section ‘Method’). A similar sample in the United Kingdom

meeting the same selection criteria was obtained from a

community mental health organisation, equivalent to the

NGOs in HK. In both samples, the main diagnosis was

psychosis, and individuals were still receiving psychiatric

services while resident in the community. The mental

health samples were collected contemporaneously in late

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

136 International Journal of Social Psychiatry 62(2)

2013 and early 2014. Previous papers (Chan, Chiu, Evans,

Huxley, & Ng, 2015; Chan, Evans, Chiu, Huxley, & Ng,

2014; Chan et al., 2014; Chan, Huxley, Chiu, Evans, &

Ma, 2015) have reported on the development of the instru-

ment and aspects of validity and reliability:

•• The similarities and shared understanding of the

model of social inclusion in focus group samples in

the United Kingdom and HK;

•• The high reliability and validity of the SCOPE-C in

the HK sample;

•• The relationship between health and the experience

of discrimination and inclusion in the HK sample.

Present study aims

The aim of this article is to report on the analysis of struc-

tural equivalence and item differentiation in two mentally

unhealthy samples and one healthy sample.

Method

Samples

The main SCOPE-C mental health sample in HK was

made up of NGO patients meeting the selection/exclusion

criteria (being well enough to be interviewed, having a for-

mal psychiatric diagnosis and living in the community

under NGO supervision). A similar sample in the United

Kingdom meeting the same selection criteria was obtained

from a community mental health organisation, equivalent

to the NGOs in HK. In both samples, the main diagnosis

was psychosis, and individuals were still receiving psychi-

atric services while resident in the community. The main

healthy population sample in the United Kingdom was col-

lected from SCOPE interviews with individuals in a repre-

sentative sample of households across the United Kingdom

collected in 2011 (Huxley et al., 2011).

Analysis

For an understanding of structural equivalence, exploratory

factor analysis has been advocated and principal components

analysis proposed as a data reduction technique. Using

Procrustean rotation (Fischer & Fontaine, 2011), the factor

structure can be rotated towards the theoretically expected

structure. It is an alternative to confirmatory factor analysis

(CFA) in complex data sets.

Differential item functioning (DIF; item bias) can be

assessed using analysis of variance (Van de Vijver &

Leung, 2011) or logistic regression. These two statistical

techniques were applied to the data.

Results

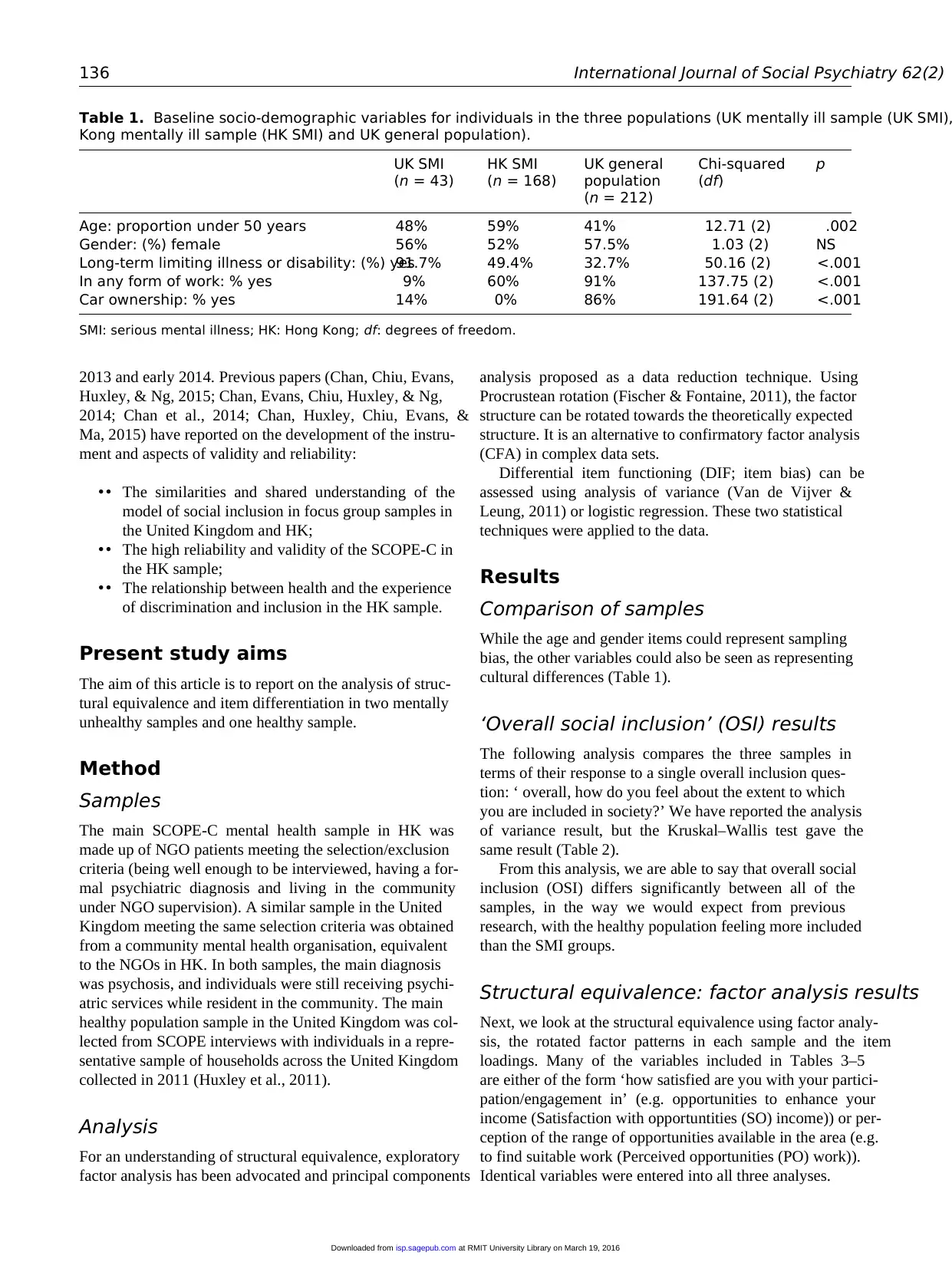

Comparison of samples

While the age and gender items could represent sampling

bias, the other variables could also be seen as representing

cultural differences (Table 1).

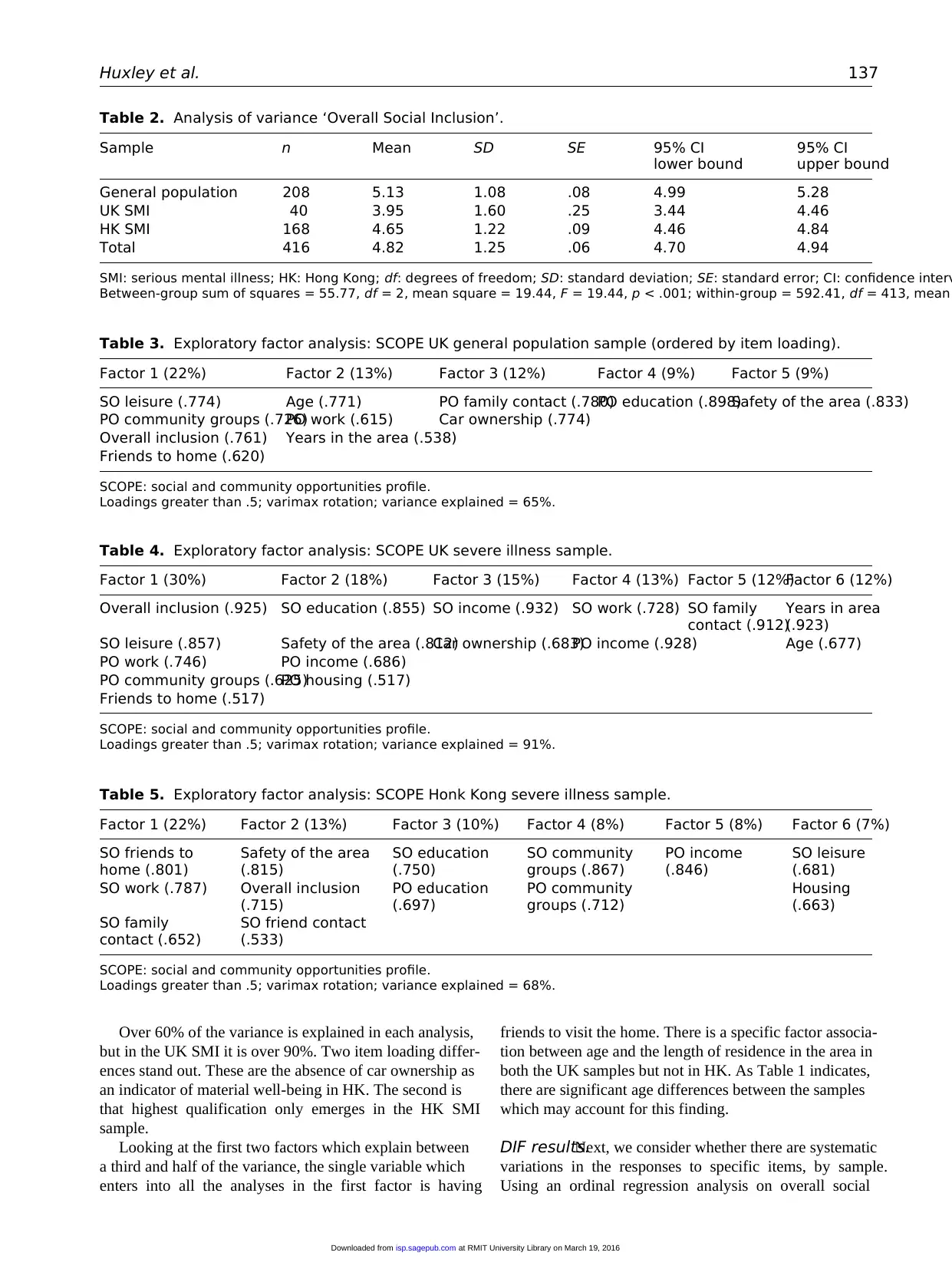

‘Overall social inclusion’ (OSI) results

The following analysis compares the three samples in

terms of their response to a single overall inclusion ques-

tion: ‘ overall, how do you feel about the extent to which

you are included in society?’ We have reported the analysis

of variance result, but the Kruskal–Wallis test gave the

same result (Table 2).

From this analysis, we are able to say that overall social

inclusion (OSI) differs significantly between all of the

samples, in the way we would expect from previous

research, with the healthy population feeling more included

than the SMI groups.

Structural equivalence: factor analysis results

Next, we look at the structural equivalence using factor analy-

sis, the rotated factor patterns in each sample and the item

loadings. Many of the variables included in Tables 3–5

are either of the form ‘how satisfied are you with your partici-

pation/engagement in’ (e.g. opportunities to enhance your

income (Satisfaction with opportuntities (SO) income)) or per-

ception of the range of opportunities available in the area (e.g.

to find suitable work (Perceived opportunities (PO) work)).

Identical variables were entered into all three analyses.

Table 1. Baseline socio-demographic variables for individuals in the three populations (UK mentally ill sample (UK SMI),

Kong mentally ill sample (HK SMI) and UK general population).

UK SMI

(n = 43)

HK SMI

(n = 168)

UK general

population

(n = 212)

Chi-squared

(df)

p

Age: proportion under 50 years 48% 59% 41% 12.71 (2) .002

Gender: (%) female 56% 52% 57.5% 1.03 (2) NS

Long-term limiting illness or disability: (%) yes91.7% 49.4% 32.7% 50.16 (2) <.001

In any form of work: % yes 9% 60% 91% 137.75 (2) <.001

Car ownership: % yes 14% 0% 86% 191.64 (2) <.001

SMI: serious mental illness; HK: Hong Kong; df: degrees of freedom.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

2013 and early 2014. Previous papers (Chan, Chiu, Evans,

Huxley, & Ng, 2015; Chan, Evans, Chiu, Huxley, & Ng,

2014; Chan et al., 2014; Chan, Huxley, Chiu, Evans, &

Ma, 2015) have reported on the development of the instru-

ment and aspects of validity and reliability:

•• The similarities and shared understanding of the

model of social inclusion in focus group samples in

the United Kingdom and HK;

•• The high reliability and validity of the SCOPE-C in

the HK sample;

•• The relationship between health and the experience

of discrimination and inclusion in the HK sample.

Present study aims

The aim of this article is to report on the analysis of struc-

tural equivalence and item differentiation in two mentally

unhealthy samples and one healthy sample.

Method

Samples

The main SCOPE-C mental health sample in HK was

made up of NGO patients meeting the selection/exclusion

criteria (being well enough to be interviewed, having a for-

mal psychiatric diagnosis and living in the community

under NGO supervision). A similar sample in the United

Kingdom meeting the same selection criteria was obtained

from a community mental health organisation, equivalent

to the NGOs in HK. In both samples, the main diagnosis

was psychosis, and individuals were still receiving psychi-

atric services while resident in the community. The main

healthy population sample in the United Kingdom was col-

lected from SCOPE interviews with individuals in a repre-

sentative sample of households across the United Kingdom

collected in 2011 (Huxley et al., 2011).

Analysis

For an understanding of structural equivalence, exploratory

factor analysis has been advocated and principal components

analysis proposed as a data reduction technique. Using

Procrustean rotation (Fischer & Fontaine, 2011), the factor

structure can be rotated towards the theoretically expected

structure. It is an alternative to confirmatory factor analysis

(CFA) in complex data sets.

Differential item functioning (DIF; item bias) can be

assessed using analysis of variance (Van de Vijver &

Leung, 2011) or logistic regression. These two statistical

techniques were applied to the data.

Results

Comparison of samples

While the age and gender items could represent sampling

bias, the other variables could also be seen as representing

cultural differences (Table 1).

‘Overall social inclusion’ (OSI) results

The following analysis compares the three samples in

terms of their response to a single overall inclusion ques-

tion: ‘ overall, how do you feel about the extent to which

you are included in society?’ We have reported the analysis

of variance result, but the Kruskal–Wallis test gave the

same result (Table 2).

From this analysis, we are able to say that overall social

inclusion (OSI) differs significantly between all of the

samples, in the way we would expect from previous

research, with the healthy population feeling more included

than the SMI groups.

Structural equivalence: factor analysis results

Next, we look at the structural equivalence using factor analy-

sis, the rotated factor patterns in each sample and the item

loadings. Many of the variables included in Tables 3–5

are either of the form ‘how satisfied are you with your partici-

pation/engagement in’ (e.g. opportunities to enhance your

income (Satisfaction with opportuntities (SO) income)) or per-

ception of the range of opportunities available in the area (e.g.

to find suitable work (Perceived opportunities (PO) work)).

Identical variables were entered into all three analyses.

Table 1. Baseline socio-demographic variables for individuals in the three populations (UK mentally ill sample (UK SMI),

Kong mentally ill sample (HK SMI) and UK general population).

UK SMI

(n = 43)

HK SMI

(n = 168)

UK general

population

(n = 212)

Chi-squared

(df)

p

Age: proportion under 50 years 48% 59% 41% 12.71 (2) .002

Gender: (%) female 56% 52% 57.5% 1.03 (2) NS

Long-term limiting illness or disability: (%) yes91.7% 49.4% 32.7% 50.16 (2) <.001

In any form of work: % yes 9% 60% 91% 137.75 (2) <.001

Car ownership: % yes 14% 0% 86% 191.64 (2) <.001

SMI: serious mental illness; HK: Hong Kong; df: degrees of freedom.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Huxley et al. 137

Over 60% of the variance is explained in each analysis,

but in the UK SMI it is over 90%. Two item loading differ-

ences stand out. These are the absence of car ownership as

an indicator of material well-being in HK. The second is

that highest qualification only emerges in the HK SMI

sample.

Looking at the first two factors which explain between

a third and half of the variance, the single variable which

enters into all the analyses in the first factor is having

friends to visit the home. There is a specific factor associa-

tion between age and the length of residence in the area in

both the UK samples but not in HK. As Table 1 indicates,

there are significant age differences between the samples

which may account for this finding.

DIF results.Next, we consider whether there are systematic

variations in the responses to specific items, by sample.

Using an ordinal regression analysis on overall social

Table 2. Analysis of variance ‘Overall Social Inclusion’.

Sample n Mean SD SE 95% CI

lower bound

95% CI

upper bound

General population 208 5.13 1.08 .08 4.99 5.28

UK SMI 40 3.95 1.60 .25 3.44 4.46

HK SMI 168 4.65 1.22 .09 4.46 4.84

Total 416 4.82 1.25 .06 4.70 4.94

SMI: serious mental illness; HK: Hong Kong; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interv

Between-group sum of squares = 55.77, df = 2, mean square = 19.44, F = 19.44, p < .001; within-group = 592.41, df = 413, mean

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE UK general population sample (ordered by item loading).

Factor 1 (22%) Factor 2 (13%) Factor 3 (12%) Factor 4 (9%) Factor 5 (9%)

SO leisure (.774) Age (.771) PO family contact (.780)PO education (.898)Safety of the area (.833)

PO community groups (.726)PO work (.615) Car ownership (.774)

Overall inclusion (.761) Years in the area (.538)

Friends to home (.620)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 65%.

Table 4. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE UK severe illness sample.

Factor 1 (30%) Factor 2 (18%) Factor 3 (15%) Factor 4 (13%) Factor 5 (12%)Factor 6 (12%)

Overall inclusion (.925) SO education (.855) SO income (.932) SO work (.728) SO family

contact (.912)

Years in area

(.923)

SO leisure (.857) Safety of the area (.812)Car ownership (.683)PO income (.928) Age (.677)

PO work (.746) PO income (.686)

PO community groups (.625)PO housing (.517)

Friends to home (.517)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 91%.

Table 5. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE Honk Kong severe illness sample.

Factor 1 (22%) Factor 2 (13%) Factor 3 (10%) Factor 4 (8%) Factor 5 (8%) Factor 6 (7%)

SO friends to

home (.801)

Safety of the area

(.815)

SO education

(.750)

SO community

groups (.867)

PO income

(.846)

SO leisure

(.681)

SO work (.787) Overall inclusion

(.715)

PO education

(.697)

PO community

groups (.712)

Housing

(.663)

SO family

contact (.652)

SO friend contact

(.533)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 68%.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Over 60% of the variance is explained in each analysis,

but in the UK SMI it is over 90%. Two item loading differ-

ences stand out. These are the absence of car ownership as

an indicator of material well-being in HK. The second is

that highest qualification only emerges in the HK SMI

sample.

Looking at the first two factors which explain between

a third and half of the variance, the single variable which

enters into all the analyses in the first factor is having

friends to visit the home. There is a specific factor associa-

tion between age and the length of residence in the area in

both the UK samples but not in HK. As Table 1 indicates,

there are significant age differences between the samples

which may account for this finding.

DIF results.Next, we consider whether there are systematic

variations in the responses to specific items, by sample.

Using an ordinal regression analysis on overall social

Table 2. Analysis of variance ‘Overall Social Inclusion’.

Sample n Mean SD SE 95% CI

lower bound

95% CI

upper bound

General population 208 5.13 1.08 .08 4.99 5.28

UK SMI 40 3.95 1.60 .25 3.44 4.46

HK SMI 168 4.65 1.22 .09 4.46 4.84

Total 416 4.82 1.25 .06 4.70 4.94

SMI: serious mental illness; HK: Hong Kong; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interv

Between-group sum of squares = 55.77, df = 2, mean square = 19.44, F = 19.44, p < .001; within-group = 592.41, df = 413, mean

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE UK general population sample (ordered by item loading).

Factor 1 (22%) Factor 2 (13%) Factor 3 (12%) Factor 4 (9%) Factor 5 (9%)

SO leisure (.774) Age (.771) PO family contact (.780)PO education (.898)Safety of the area (.833)

PO community groups (.726)PO work (.615) Car ownership (.774)

Overall inclusion (.761) Years in the area (.538)

Friends to home (.620)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 65%.

Table 4. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE UK severe illness sample.

Factor 1 (30%) Factor 2 (18%) Factor 3 (15%) Factor 4 (13%) Factor 5 (12%)Factor 6 (12%)

Overall inclusion (.925) SO education (.855) SO income (.932) SO work (.728) SO family

contact (.912)

Years in area

(.923)

SO leisure (.857) Safety of the area (.812)Car ownership (.683)PO income (.928) Age (.677)

PO work (.746) PO income (.686)

PO community groups (.625)PO housing (.517)

Friends to home (.517)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 91%.

Table 5. Exploratory factor analysis: SCOPE Honk Kong severe illness sample.

Factor 1 (22%) Factor 2 (13%) Factor 3 (10%) Factor 4 (8%) Factor 5 (8%) Factor 6 (7%)

SO friends to

home (.801)

Safety of the area

(.815)

SO education

(.750)

SO community

groups (.867)

PO income

(.846)

SO leisure

(.681)

SO work (.787) Overall inclusion

(.715)

PO education

(.697)

PO community

groups (.712)

Housing

(.663)

SO family

contact (.652)

SO friend contact

(.533)

SCOPE: social and community opportunities profile.

Loadings greater than .5; varimax rotation; variance explained = 68%.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

138 International Journal of Social Psychiatry 62(2)

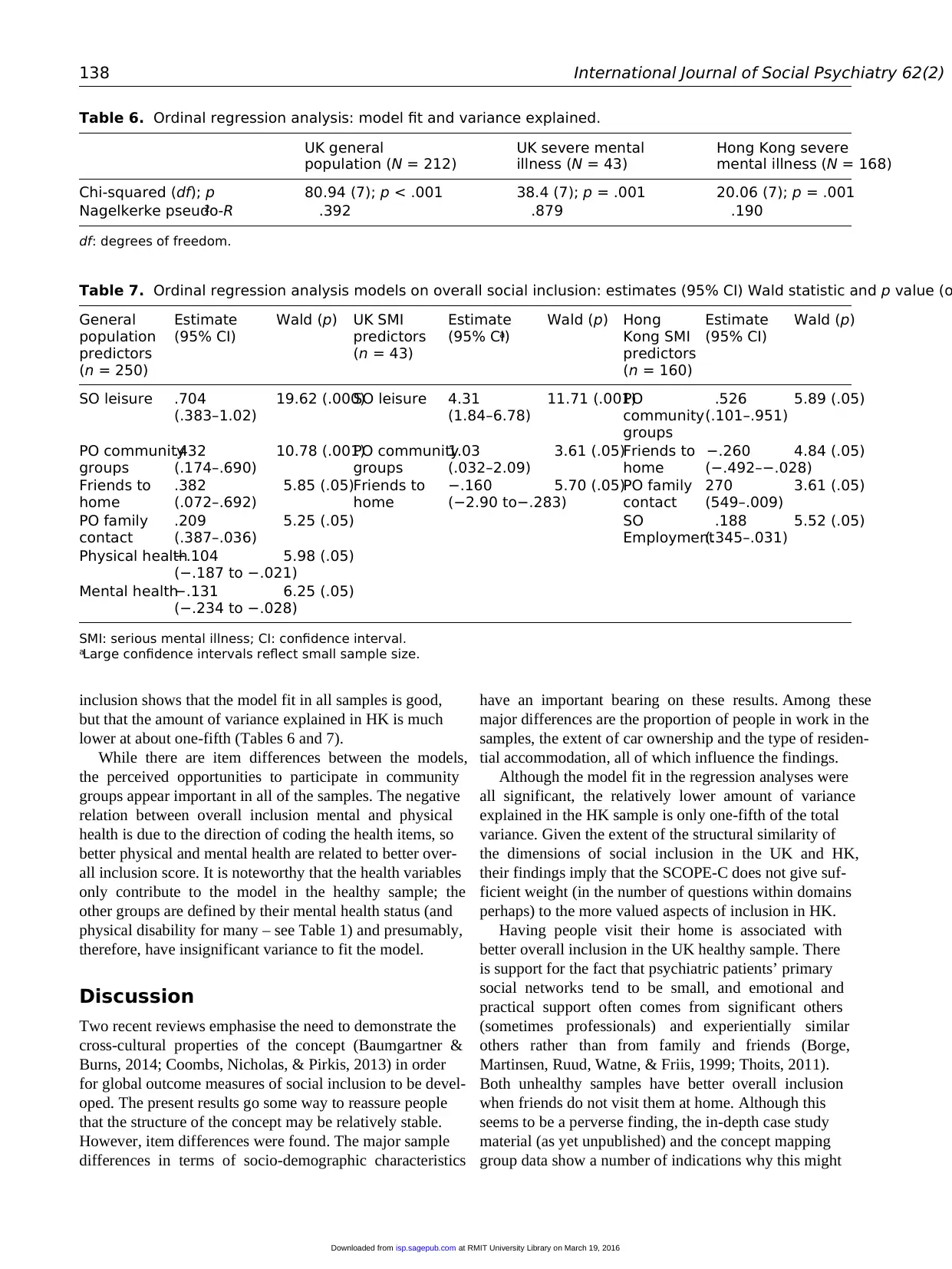

inclusion shows that the model fit in all samples is good,

but that the amount of variance explained in HK is much

lower at about one-fifth (Tables 6 and 7).

While there are item differences between the models,

the perceived opportunities to participate in community

groups appear important in all of the samples. The negative

relation between overall inclusion mental and physical

health is due to the direction of coding the health items, so

better physical and mental health are related to better over-

all inclusion score. It is noteworthy that the health variables

only contribute to the model in the healthy sample; the

other groups are defined by their mental health status (and

physical disability for many – see Table 1) and presumably,

therefore, have insignificant variance to fit the model.

Discussion

Two recent reviews emphasise the need to demonstrate the

cross-cultural properties of the concept (Baumgartner &

Burns, 2014; Coombs, Nicholas, & Pirkis, 2013) in order

for global outcome measures of social inclusion to be devel-

oped. The present results go some way to reassure people

that the structure of the concept may be relatively stable.

However, item differences were found. The major sample

differences in terms of socio-demographic characteristics

have an important bearing on these results. Among these

major differences are the proportion of people in work in the

samples, the extent of car ownership and the type of residen-

tial accommodation, all of which influence the findings.

Although the model fit in the regression analyses were

all significant, the relatively lower amount of variance

explained in the HK sample is only one-fifth of the total

variance. Given the extent of the structural similarity of

the dimensions of social inclusion in the UK and HK,

their findings imply that the SCOPE-C does not give suf-

ficient weight (in the number of questions within domains

perhaps) to the more valued aspects of inclusion in HK.

Having people visit their home is associated with

better overall inclusion in the UK healthy sample. There

is support for the fact that psychiatric patients’ primary

social networks tend to be small, and emotional and

practical support often comes from significant others

(sometimes professionals) and experientially similar

others rather than from family and friends (Borge,

Martinsen, Ruud, Watne, & Friis, 1999; Thoits, 2011).

Both unhealthy samples have better overall inclusion

when friends do not visit them at home. Although this

seems to be a perverse finding, the in-depth case study

material (as yet unpublished) and the concept mapping

group data show a number of indications why this might

Table 6. Ordinal regression analysis: model fit and variance explained.

UK general

population (N = 212)

UK severe mental

illness (N = 43)

Hong Kong severe

mental illness (N = 168)

Chi-squared (df); p 80.94 (7); p < .001 38.4 (7); p = .001 20.06 (7); p = .001

Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 .392 .879 .190

df: degrees of freedom.

Table 7. Ordinal regression analysis models on overall social inclusion: estimates (95% CI) Wald statistic and p value (o

General

population

predictors

(n = 250)

Estimate

(95% CI)

Wald (p) UK SMI

predictors

(n = 43)

Estimate

(95% CI)a

Wald (p) Hong

Kong SMI

predictors

(n = 160)

Estimate

(95% CI)

Wald (p)

SO leisure .704

(.383–1.02)

19.62 (.000)SO leisure 4.31

(1.84–6.78)

11.71 (.001)PO

community

groups

.526

(.101–.951)

5.89 (.05)

PO community

groups

.432

(.174–.690)

10.78 (.001)PO community

groups

1.03

(.032–2.09)

3.61 (.05)Friends to

home

−.260

(−.492–−.028)

4.84 (.05)

Friends to

home

.382

(.072–.692)

5.85 (.05)Friends to

home

−.160

(−2.90 to−.283)

5.70 (.05)PO family

contact

270

(549–.009)

3.61 (.05)

PO family

contact

.209

(.387–.036)

5.25 (.05) SO

Employment

.188

(.345–.031)

5.52 (.05)

Physical health−.104

(−.187 to −.021)

5.98 (.05)

Mental health−.131

(−.234 to −.028)

6.25 (.05)

SMI: serious mental illness; CI: confidence interval.

aLarge confidence intervals reflect small sample size.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

inclusion shows that the model fit in all samples is good,

but that the amount of variance explained in HK is much

lower at about one-fifth (Tables 6 and 7).

While there are item differences between the models,

the perceived opportunities to participate in community

groups appear important in all of the samples. The negative

relation between overall inclusion mental and physical

health is due to the direction of coding the health items, so

better physical and mental health are related to better over-

all inclusion score. It is noteworthy that the health variables

only contribute to the model in the healthy sample; the

other groups are defined by their mental health status (and

physical disability for many – see Table 1) and presumably,

therefore, have insignificant variance to fit the model.

Discussion

Two recent reviews emphasise the need to demonstrate the

cross-cultural properties of the concept (Baumgartner &

Burns, 2014; Coombs, Nicholas, & Pirkis, 2013) in order

for global outcome measures of social inclusion to be devel-

oped. The present results go some way to reassure people

that the structure of the concept may be relatively stable.

However, item differences were found. The major sample

differences in terms of socio-demographic characteristics

have an important bearing on these results. Among these

major differences are the proportion of people in work in the

samples, the extent of car ownership and the type of residen-

tial accommodation, all of which influence the findings.

Although the model fit in the regression analyses were

all significant, the relatively lower amount of variance

explained in the HK sample is only one-fifth of the total

variance. Given the extent of the structural similarity of

the dimensions of social inclusion in the UK and HK,

their findings imply that the SCOPE-C does not give suf-

ficient weight (in the number of questions within domains

perhaps) to the more valued aspects of inclusion in HK.

Having people visit their home is associated with

better overall inclusion in the UK healthy sample. There

is support for the fact that psychiatric patients’ primary

social networks tend to be small, and emotional and

practical support often comes from significant others

(sometimes professionals) and experientially similar

others rather than from family and friends (Borge,

Martinsen, Ruud, Watne, & Friis, 1999; Thoits, 2011).

Both unhealthy samples have better overall inclusion

when friends do not visit them at home. Although this

seems to be a perverse finding, the in-depth case study

material (as yet unpublished) and the concept mapping

group data show a number of indications why this might

Table 6. Ordinal regression analysis: model fit and variance explained.

UK general

population (N = 212)

UK severe mental

illness (N = 43)

Hong Kong severe

mental illness (N = 168)

Chi-squared (df); p 80.94 (7); p < .001 38.4 (7); p = .001 20.06 (7); p = .001

Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 .392 .879 .190

df: degrees of freedom.

Table 7. Ordinal regression analysis models on overall social inclusion: estimates (95% CI) Wald statistic and p value (o

General

population

predictors

(n = 250)

Estimate

(95% CI)

Wald (p) UK SMI

predictors

(n = 43)

Estimate

(95% CI)a

Wald (p) Hong

Kong SMI

predictors

(n = 160)

Estimate

(95% CI)

Wald (p)

SO leisure .704

(.383–1.02)

19.62 (.000)SO leisure 4.31

(1.84–6.78)

11.71 (.001)PO

community

groups

.526

(.101–.951)

5.89 (.05)

PO community

groups

.432

(.174–.690)

10.78 (.001)PO community

groups

1.03

(.032–2.09)

3.61 (.05)Friends to

home

−.260

(−.492–−.028)

4.84 (.05)

Friends to

home

.382

(.072–.692)

5.85 (.05)Friends to

home

−.160

(−2.90 to−.283)

5.70 (.05)PO family

contact

270

(549–.009)

3.61 (.05)

PO family

contact

.209

(.387–.036)

5.25 (.05) SO

Employment

.188

(.345–.031)

5.52 (.05)

Physical health−.104

(−.187 to −.021)

5.98 (.05)

Mental health−.131

(−.234 to −.028)

6.25 (.05)

SMI: serious mental illness; CI: confidence interval.

aLarge confidence intervals reflect small sample size.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Huxley et al. 139

be the case. First, patients in group home settings in HK

and United Kingdom are encouraged to go out to social-

ise, rather than stay at home all day. In HK, and to a

lesser extent in the United Kingdom, homes are often

small and not especially welcoming. In addition, some

of the housing locations are themselves a factor in that

they are often in deprived neighbourhoods and tower

blocks which the patient feel is stigmatising, and they

would rather socialise away from home at work or in

community groups.

There are no car owners in the HK sample, and this is a

reflection of the cost of purchasing a car in HK and of the

living arrangements in high-rise apartment blocks and close

proximity to family members, and the ease of transport

around the city and the lowest level of car ownership of any

major global conurbation (Cullinane 2002; Cullinane &

Cullinane, 2003). However, in the United Kingdom, car

ownership is more necessary and has been used previously

as a proxy indicator of material wealth and does have a

bearing on inclusion, especially in rural areas. Another

indicator of material well-being needs to be substituted for

or added to car ownership for SCOPE-C, for example, the

size of the space available per family member might be a

better indicator of material advantage in HK. Although we

amended some of the SCOPE objective questions to make

them consistent with the wording of the HK census, we

may have to add more questions or revise existing ones in

order to explain more of the variance of overall inclusion.

Conclusion

SCOPE is one of very few direct measures of social inclu-

sion (Baumgartner & Burns, 2014) and has been singled

out as one of only two measures worthy of further develop-

ment work (Coombs et al., 2013). The need for a global

cross-cultural measure that has been developed and tested

in diverse settings has been reiterated recently (Baumgartner

& Burns, 2014).

The lower amount of variance explained in the HK

sample suggests that improvements can be made to capture

more of the variance of overall inclusion. This will be the

subject of further data gathering and qualitative analysis

from detailed case studies and a feedback event for NGO

managers and workers, plus a re-consideration of the con-

cept mapping data. Evidently, an instrument developed to

measure the particular circumstances of one disability

group in one culture is more likely to explain a large

amount of the variance of local responses. When re-located

into another culture, although the structure of domains of

inclusion remains similar, the power to explain overall

inclusion ratings seems to be diminishing.

China’s future major health problem is going to be the

management of chronic diseases (of which mental health

is a major one) in community settings (World Health

Organization (WHO), 2008). A suitably modified SCOPE-C

may be used by mental health services in HK and mainland

China as they strive to promote a more inclusive society for

their citizens and particular disadvantaged groups.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Economic & Social Research Council

(Project no.: ES/K005227/1). We are thankful to the NGOs who

facilitate our contact with the voluntary participants who took

part in the study. These NGOs include Baptist Oi Kwan Social

Services, Caritas Hong Kong, Fu Hong Society, Stewards Social

Services, The Mental Health Association of Hong Kong, and The

Society of Rehabilitation and Crime Prevention.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This project was funded by Economic & Social Research Council

(Project no.: ES/K005227/1).

References

Baumgartner, J. N., & Burns, J. K. (2014). Measuring social

inclusion – A key outcome in global mental health.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 354–364.

doi:10.1093/ije/dyt224

Berg, M., Jahnsen, R., Holm, I., & Hussain, A. (2003). Translation of

a multi-disciplinary assessment – Procedures to achieve func-

tional equivalence. Advances in Physiotherapy, 5(2), 57–66.

Blaxland, M., Fisher, K. R., & Shang, X. (2015). Transitional

and developmental challenges for Chinese social policy.

Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 9, 1–2. doi:10.1111/

aswp.12047

Borge, L., Martinsen, E. W., Ruud, T., Watne, O., & Friis, S.

(1999). Quality of life, loneliness, and social contact among

long-term psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 50,

81–84. doi:10.1176/ps.50.1.81

Boushey, H., Fremstad, S., Gragg, R., & Waller, M. (2007).

Social inclusion for the USA: Advocating the use of the con-

cept in the USA. Available at: www.inclusionist.org/files/

socialinclusionusa.pdf

Bowden, A., & Fox-Rushby, J. A. (2003). A systematic and criti-

cal review of the process of translation and adaptation of

generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa,

Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America.

Social Science & Medicine, 57, 1289–1306.

Chan, K., Chiu, M., Evans, S., Huxley, P. J., & Ng, Y. L.

(2015b). Application of SCOPE-C to measure social inclu-

sion among mental health services users in Hong Kong.

Community Mental Health Journal. Advance online publi-

cation. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9907-z

Chan, K., Evans, S., Chiu, M., Huxley, P. J., & Ng, Y. L. (2014a).

Relationship between health, experience of discrimination,

and social inclusion among mental health service users in

Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 124(1), 127–139.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

be the case. First, patients in group home settings in HK

and United Kingdom are encouraged to go out to social-

ise, rather than stay at home all day. In HK, and to a

lesser extent in the United Kingdom, homes are often

small and not especially welcoming. In addition, some

of the housing locations are themselves a factor in that

they are often in deprived neighbourhoods and tower

blocks which the patient feel is stigmatising, and they

would rather socialise away from home at work or in

community groups.

There are no car owners in the HK sample, and this is a

reflection of the cost of purchasing a car in HK and of the

living arrangements in high-rise apartment blocks and close

proximity to family members, and the ease of transport

around the city and the lowest level of car ownership of any

major global conurbation (Cullinane 2002; Cullinane &

Cullinane, 2003). However, in the United Kingdom, car

ownership is more necessary and has been used previously

as a proxy indicator of material wealth and does have a

bearing on inclusion, especially in rural areas. Another

indicator of material well-being needs to be substituted for

or added to car ownership for SCOPE-C, for example, the

size of the space available per family member might be a

better indicator of material advantage in HK. Although we

amended some of the SCOPE objective questions to make

them consistent with the wording of the HK census, we

may have to add more questions or revise existing ones in

order to explain more of the variance of overall inclusion.

Conclusion

SCOPE is one of very few direct measures of social inclu-

sion (Baumgartner & Burns, 2014) and has been singled

out as one of only two measures worthy of further develop-

ment work (Coombs et al., 2013). The need for a global

cross-cultural measure that has been developed and tested

in diverse settings has been reiterated recently (Baumgartner

& Burns, 2014).

The lower amount of variance explained in the HK

sample suggests that improvements can be made to capture

more of the variance of overall inclusion. This will be the

subject of further data gathering and qualitative analysis

from detailed case studies and a feedback event for NGO

managers and workers, plus a re-consideration of the con-

cept mapping data. Evidently, an instrument developed to

measure the particular circumstances of one disability

group in one culture is more likely to explain a large

amount of the variance of local responses. When re-located

into another culture, although the structure of domains of

inclusion remains similar, the power to explain overall

inclusion ratings seems to be diminishing.

China’s future major health problem is going to be the

management of chronic diseases (of which mental health

is a major one) in community settings (World Health

Organization (WHO), 2008). A suitably modified SCOPE-C

may be used by mental health services in HK and mainland

China as they strive to promote a more inclusive society for

their citizens and particular disadvantaged groups.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Economic & Social Research Council

(Project no.: ES/K005227/1). We are thankful to the NGOs who

facilitate our contact with the voluntary participants who took

part in the study. These NGOs include Baptist Oi Kwan Social

Services, Caritas Hong Kong, Fu Hong Society, Stewards Social

Services, The Mental Health Association of Hong Kong, and The

Society of Rehabilitation and Crime Prevention.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This project was funded by Economic & Social Research Council

(Project no.: ES/K005227/1).

References

Baumgartner, J. N., & Burns, J. K. (2014). Measuring social

inclusion – A key outcome in global mental health.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 354–364.

doi:10.1093/ije/dyt224

Berg, M., Jahnsen, R., Holm, I., & Hussain, A. (2003). Translation of

a multi-disciplinary assessment – Procedures to achieve func-

tional equivalence. Advances in Physiotherapy, 5(2), 57–66.

Blaxland, M., Fisher, K. R., & Shang, X. (2015). Transitional

and developmental challenges for Chinese social policy.

Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 9, 1–2. doi:10.1111/

aswp.12047

Borge, L., Martinsen, E. W., Ruud, T., Watne, O., & Friis, S.

(1999). Quality of life, loneliness, and social contact among

long-term psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 50,

81–84. doi:10.1176/ps.50.1.81

Boushey, H., Fremstad, S., Gragg, R., & Waller, M. (2007).

Social inclusion for the USA: Advocating the use of the con-

cept in the USA. Available at: www.inclusionist.org/files/

socialinclusionusa.pdf

Bowden, A., & Fox-Rushby, J. A. (2003). A systematic and criti-

cal review of the process of translation and adaptation of

generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa,

Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America.

Social Science & Medicine, 57, 1289–1306.

Chan, K., Chiu, M., Evans, S., Huxley, P. J., & Ng, Y. L.

(2015b). Application of SCOPE-C to measure social inclu-

sion among mental health services users in Hong Kong.

Community Mental Health Journal. Advance online publi-

cation. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9907-z

Chan, K., Evans, S., Chiu, M., Huxley, P. J., & Ng, Y. L. (2014a).

Relationship between health, experience of discrimination,

and social inclusion among mental health service users in

Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 124(1), 127–139.

at RMIT University Library on March 19, 2016isp.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

140 International Journal of Social Psychiatry 62(2)

Chan, K., Evans, S., Ng, Y. L., Chiu, M., & Huxley, P. (2014b).

A concept mapping study on social inclusion in Hong Kong.

Social Indicators Research, 119, 121–137.

Chan, K., Huxley, P. J., Chiu, M., Evans, S., & Ma, Y. (2015a).

Social inclusion and health conditions among Chinese

immigrants in Hong Kong and the United Kingdom: An

exploratory study. Social Indicators Research. Advance

online publication. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0910-0

Cheung, Y. B., & Thumboo, J. (2006). Developing health-related

quality-of-life instruments for use in Asia: The issues.

Pharmacoeconomics, 24, 643–650.

Commission of the European Communities. (2000). Social pol-

icy agenda: Communication from the Commission to the

Council, the European Parliament, the economic and social

committee and the committee of the regions. Brussels,

Belgium: Author.

Coombs, T., Nicholas, A., & Pirkis, J. (2013). A review of social

inclusion measures. The Australian and New Zealand Journal

of Psychiatry, 47, 906–919. doi:10.1177/0004867413491161

Council for the European Union. (2003). Joint report by the

Commission and the Council on social inclusion. Brussels,

Belgium: Author.

Cullinane, S. (2002). The relationship between car ownership

and public transport provision: A case study of Hong Kong.

Transport Policy, 9, 29–39.

Cullinane, S., & Cullinane, C. (2003). Car dependence in a

public transport dominated city: Evidence from Hong

Kong. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and

Environment, 8, 129–138.

Curran, C., Burchardt, T., Knapp, M., Mcdaid, D., & Li, B.

(2007). Changes in multidisciplinary systematic reviewing:

A study on social exclusion and mental health policy. Social

Policy and Administration, 1, 289–312.

Fischer, R., & Fontaine, J. R. J. (2011). Methods for investigating

structural equivalence. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. Van de

Vijver (Eds.), Cross cultural research methods in psychol-

ogy (pp. 179–215). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Fisher, K., & Jing, L. (2008). Chinese disability independent liv-

ing policy. Disability and Society, 23, 171–185.

Gordon, D. (2000). Breadline Europe: The measurement of pov-

erty. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Herdman, M., Fox-Rushby, J., & Badia, X. (1998). A model of

equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments:

The universalist approach. Quality of Life Research, 7, 323–335.

Huxley, P., Evans, S., Madge, S., Webber, M., Burchardt,

T., McDaid, D., & Knapp, M. (2012). Development of a

social inclusion index to capture subjective and objective

life domains (Phase II): Psychometric development study.

Health Technology Assessment, 16, iii–vii, ix–xii, 1–241.

doi:10.3310/hta16010

Johnson, T. P., Shavitt, S., & Holbrook, A. L. (2011). Survey

response styles across cultures. In D. Matsumoto & F. J.

R. Van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross cultural research methods

in psychology (pp. 130–178). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Lee, J. W., & Jung, D. Y. (2006). Measurement issues across

different cultures. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing,

36, 1295–1300.

Leff, J., & Warner, R. (2006). Social inclusion of people with

mental illness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Luhrmann, T. M. (2014, December 15). Wheat people vs. rice

people – Association for Psychological Science. International

New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.psychologicals-

cience.org/index.php/news/wheat-people-vs-rice-people.html

Mahler, C., Jank, S., Reuschenbach, B., & Szecsenyi, J. (2009).

‘Let’s quickly translate this questionnaire’ – Guidelines for

translation and implementation of English-language assess-

ment instruments. Pflegewissenschaft, 13(1), 5–12.

Matsumoto, D., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (Eds.). (2011). Cross-

cultural research methods in psychology. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Mental Health Europe. (2008). From exclusion to inclusion:

The way forward to promoting social inclusion of people

with mental health problems in Europe. Brussels, Belgium:

Mental Health Europe.

Repper, J., & Perkins, R. (2003). Social inclusion and recov-

ery: A model for mental health practice. London, England:

Baillière Tindall.

Steele, G., & Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in

China: Individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-

being during China’s economic and social transformation.

Social Indicators Research, 114, 441–451.

Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. R. (2008). Health measurement

scales: A practical guide to their development and use (4th

ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support

to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 52, 145–161. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom.

Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Tran, T. V. (2009). Developing cross cultural measurement.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ungvari, G., & Chiu, H. F. K. (2004). The state of psychiatry