Global Economy Analysis: MAE203 Assignment, Trimester 1, 2019

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|7

|1838

|100

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment analyzes the global economy, focusing on the relationship between real GDP growth and unemployment, nominal GDP growth and inflation, and the patterns of inflation and unemployment in Australia. It also explores the factors influencing aggregate expenditure and discusses the impact of supply shocks on an economy, including both short-run and long-run effects. The assignment includes data analysis, graphical representations, and short answer explanations, adhering to the requirements of the MAE203 course, emphasizing data collection, presentation, and analytical skills. Furthermore, it briefly touches upon consumer confidence and the effects of interest rates on investment and consumption. The student utilizes graphs and economic models to explain the concepts and relationships discussed.

International relation & global economy 1

International relation & global economy

Name

Institution

Course

Date

International relation & global economy

Name

Institution

Course

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

International relation & global economy

PART A

Question 2

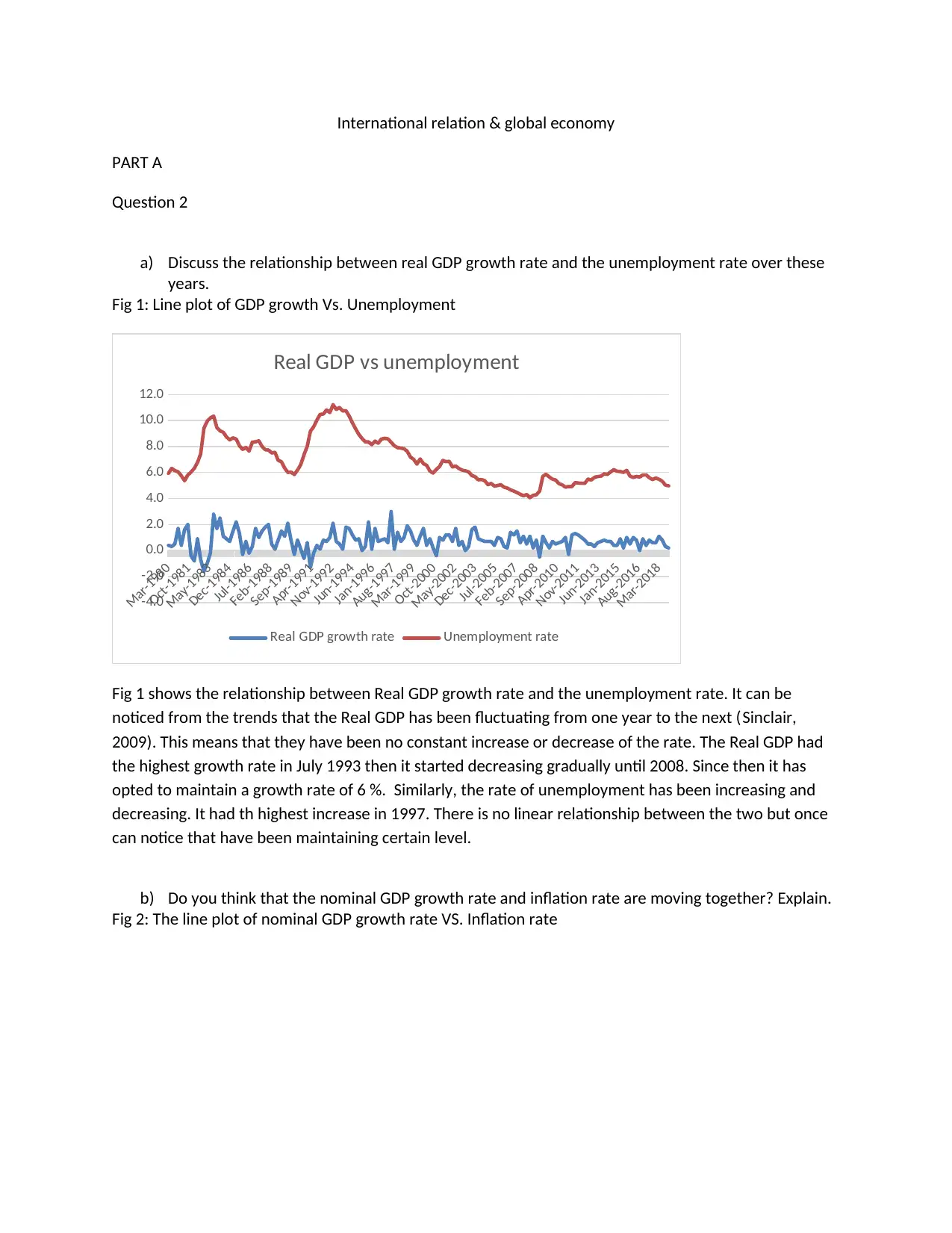

a) Discuss the relationship between real GDP growth rate and the unemployment rate over these

years.

Fig 1: Line plot of GDP growth Vs. Unemployment

Mar-1980

Oct-1981

May-1983

Dec-1984

Jul-1986

Feb-1988

Sep-1989

Apr-1991

Nov-1992

Jun-1994

Jan-1996

Aug-1997

Mar-1999

Oct-2000

May-2002

Dec-2003

Jul-2005

Feb-2007

Sep-2008

Apr-2010

Nov-2011

Jun-2013

Jan-2015

Aug-2016

Mar-2018

-4.0

-2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

Real GDP vs unemployment

Real GDP growth rate Unemployment rate

Fig 1 shows the relationship between Real GDP growth rate and the unemployment rate. It can be

noticed from the trends that the Real GDP has been fluctuating from one year to the next (Sinclair,

2009). This means that they have been no constant increase or decrease of the rate. The Real GDP had

the highest growth rate in July 1993 then it started decreasing gradually until 2008. Since then it has

opted to maintain a growth rate of 6 %. Similarly, the rate of unemployment has been increasing and

decreasing. It had th highest increase in 1997. There is no linear relationship between the two but once

can notice that have been maintaining certain level.

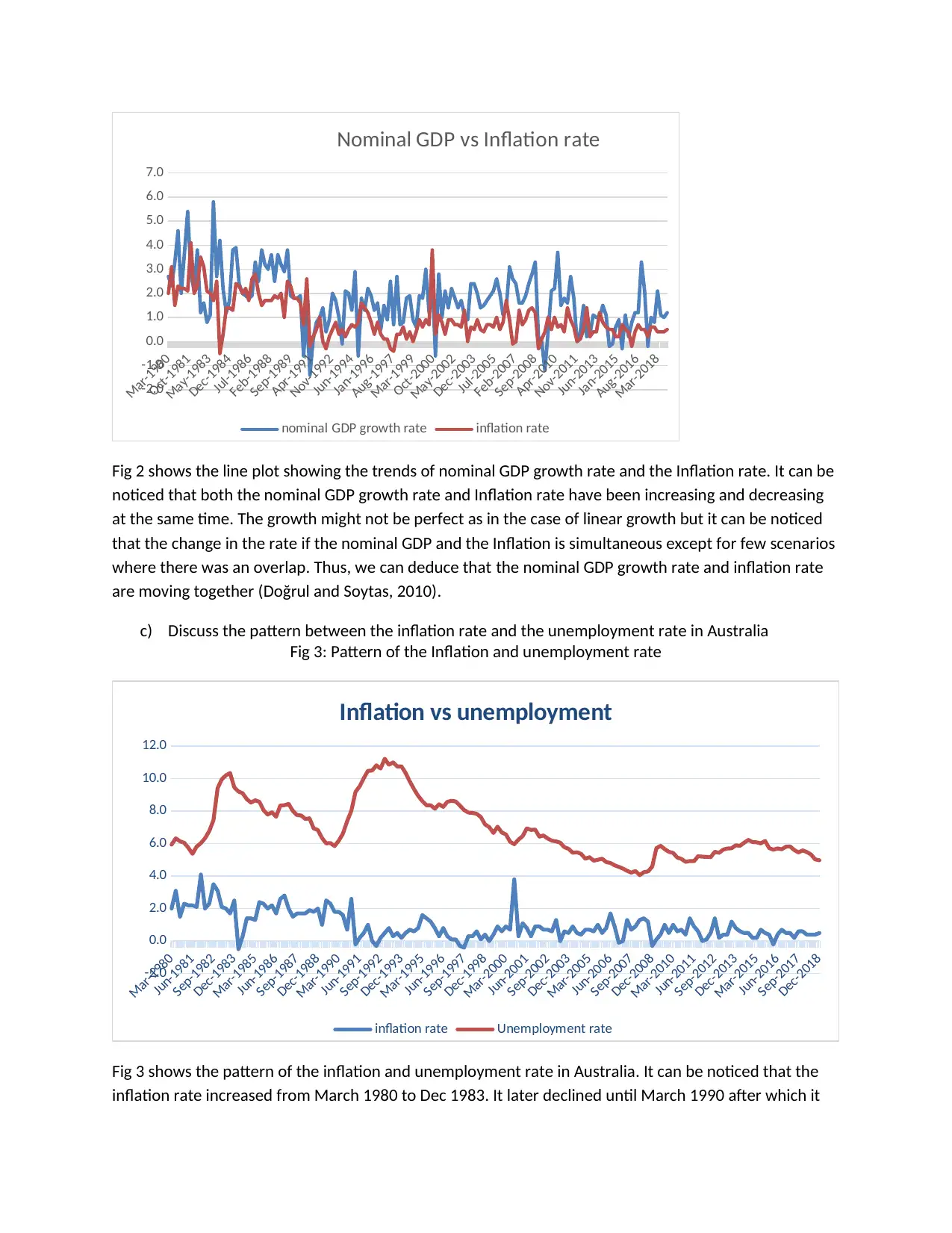

b) Do you think that the nominal GDP growth rate and inflation rate are moving together? Explain.

Fig 2: The line plot of nominal GDP growth rate VS. Inflation rate

PART A

Question 2

a) Discuss the relationship between real GDP growth rate and the unemployment rate over these

years.

Fig 1: Line plot of GDP growth Vs. Unemployment

Mar-1980

Oct-1981

May-1983

Dec-1984

Jul-1986

Feb-1988

Sep-1989

Apr-1991

Nov-1992

Jun-1994

Jan-1996

Aug-1997

Mar-1999

Oct-2000

May-2002

Dec-2003

Jul-2005

Feb-2007

Sep-2008

Apr-2010

Nov-2011

Jun-2013

Jan-2015

Aug-2016

Mar-2018

-4.0

-2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

Real GDP vs unemployment

Real GDP growth rate Unemployment rate

Fig 1 shows the relationship between Real GDP growth rate and the unemployment rate. It can be

noticed from the trends that the Real GDP has been fluctuating from one year to the next (Sinclair,

2009). This means that they have been no constant increase or decrease of the rate. The Real GDP had

the highest growth rate in July 1993 then it started decreasing gradually until 2008. Since then it has

opted to maintain a growth rate of 6 %. Similarly, the rate of unemployment has been increasing and

decreasing. It had th highest increase in 1997. There is no linear relationship between the two but once

can notice that have been maintaining certain level.

b) Do you think that the nominal GDP growth rate and inflation rate are moving together? Explain.

Fig 2: The line plot of nominal GDP growth rate VS. Inflation rate

Mar-1980

Oct-1981

May-1983

Dec-1984

Jul-1986

Feb-1988

Sep-1989

Apr-1991

Nov-1992

Jun-1994

Jan-1996

Aug-1997

Mar-1999

Oct-2000

May-2002

Dec-2003

Jul-2005

Feb-2007

Sep-2008

Apr-2010

Nov-2011

Jun-2013

Jan-2015

Aug-2016

Mar-2018

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

Nominal GDP vs Inflation rate

nominal GDP growth rate inflation rate

Fig 2 shows the line plot showing the trends of nominal GDP growth rate and the Inflation rate. It can be

noticed that both the nominal GDP growth rate and Inflation rate have been increasing and decreasing

at the same time. The growth might not be perfect as in the case of linear growth but it can be noticed

that the change in the rate if the nominal GDP and the Inflation is simultaneous except for few scenarios

where there was an overlap. Thus, we can deduce that the nominal GDP growth rate and inflation rate

are moving together (Doğrul and Soytas, 2010).

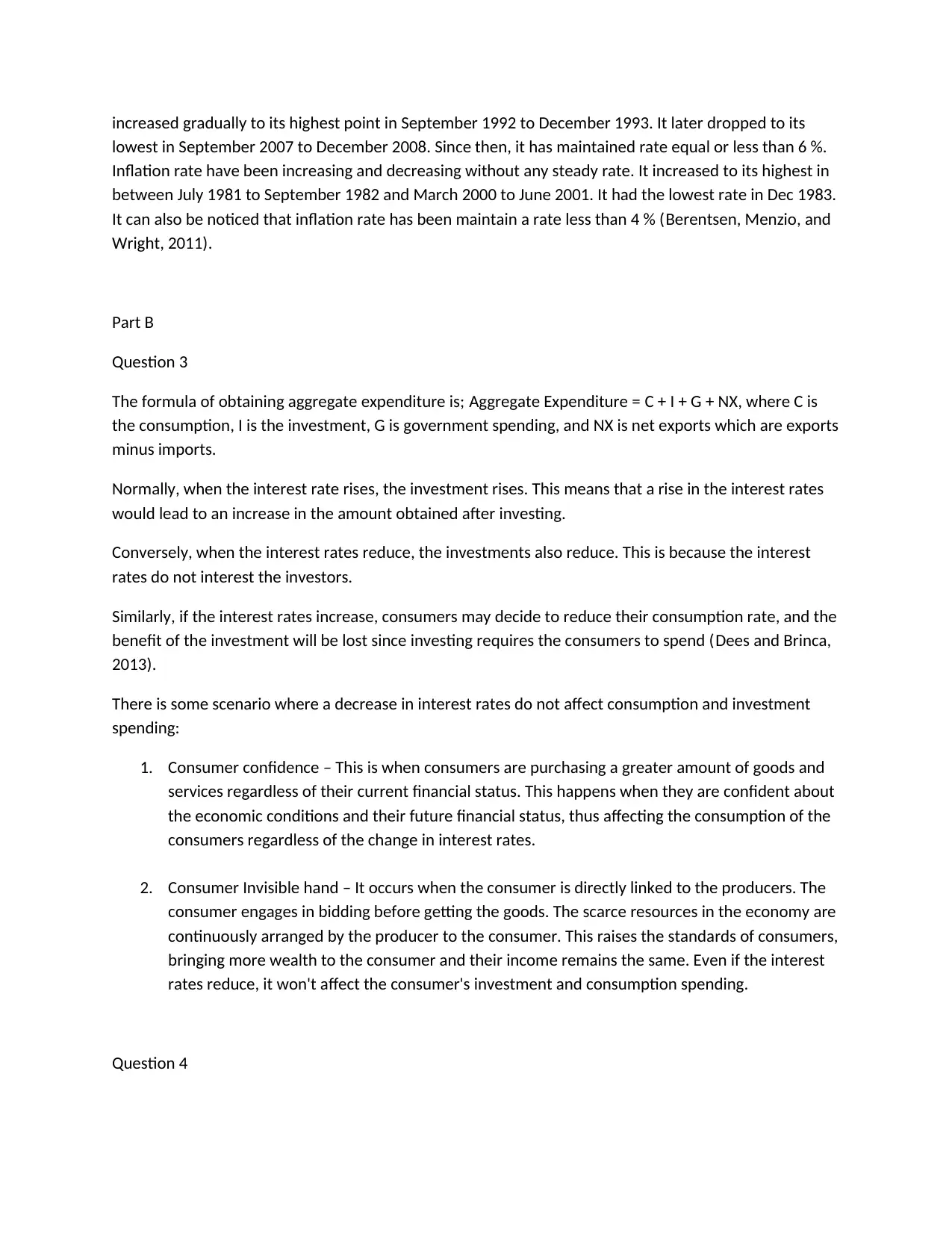

c) Discuss the pattern between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate in Australia

Fig 3: Pattern of the Inflation and unemployment rate

Mar-1980

Jun-1981

Sep-1982

Dec-1983

Mar-1985

Jun-1986

Sep-1987

Dec-1988

Mar-1990

Jun-1991

Sep-1992

Dec-1993

Mar-1995

Jun-1996

Sep-1997

Dec-1998

Mar-2000

Jun-2001

Sep-2002

Dec-2003

Mar-2005

Jun-2006

Sep-2007

Dec-2008

Mar-2010

Jun-2011

Sep-2012

Dec-2013

Mar-2015

Jun-2016

Sep-2017

Dec-2018

-2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

Inflation vs unemployment

inflation rate Unemployment rate

Fig 3 shows the pattern of the inflation and unemployment rate in Australia. It can be noticed that the

inflation rate increased from March 1980 to Dec 1983. It later declined until March 1990 after which it

Oct-1981

May-1983

Dec-1984

Jul-1986

Feb-1988

Sep-1989

Apr-1991

Nov-1992

Jun-1994

Jan-1996

Aug-1997

Mar-1999

Oct-2000

May-2002

Dec-2003

Jul-2005

Feb-2007

Sep-2008

Apr-2010

Nov-2011

Jun-2013

Jan-2015

Aug-2016

Mar-2018

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

Nominal GDP vs Inflation rate

nominal GDP growth rate inflation rate

Fig 2 shows the line plot showing the trends of nominal GDP growth rate and the Inflation rate. It can be

noticed that both the nominal GDP growth rate and Inflation rate have been increasing and decreasing

at the same time. The growth might not be perfect as in the case of linear growth but it can be noticed

that the change in the rate if the nominal GDP and the Inflation is simultaneous except for few scenarios

where there was an overlap. Thus, we can deduce that the nominal GDP growth rate and inflation rate

are moving together (Doğrul and Soytas, 2010).

c) Discuss the pattern between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate in Australia

Fig 3: Pattern of the Inflation and unemployment rate

Mar-1980

Jun-1981

Sep-1982

Dec-1983

Mar-1985

Jun-1986

Sep-1987

Dec-1988

Mar-1990

Jun-1991

Sep-1992

Dec-1993

Mar-1995

Jun-1996

Sep-1997

Dec-1998

Mar-2000

Jun-2001

Sep-2002

Dec-2003

Mar-2005

Jun-2006

Sep-2007

Dec-2008

Mar-2010

Jun-2011

Sep-2012

Dec-2013

Mar-2015

Jun-2016

Sep-2017

Dec-2018

-2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

Inflation vs unemployment

inflation rate Unemployment rate

Fig 3 shows the pattern of the inflation and unemployment rate in Australia. It can be noticed that the

inflation rate increased from March 1980 to Dec 1983. It later declined until March 1990 after which it

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

increased gradually to its highest point in September 1992 to December 1993. It later dropped to its

lowest in September 2007 to December 2008. Since then, it has maintained rate equal or less than 6 %.

Inflation rate have been increasing and decreasing without any steady rate. It increased to its highest in

between July 1981 to September 1982 and March 2000 to June 2001. It had the lowest rate in Dec 1983.

It can also be noticed that inflation rate has been maintain a rate less than 4 % (Berentsen, Menzio, and

Wright, 2011).

Part B

Question 3

The formula of obtaining aggregate expenditure is; Aggregate Expenditure = C + I + G + NX, where C is

the consumption, I is the investment, G is government spending, and NX is net exports which are exports

minus imports.

Normally, when the interest rate rises, the investment rises. This means that a rise in the interest rates

would lead to an increase in the amount obtained after investing.

Conversely, when the interest rates reduce, the investments also reduce. This is because the interest

rates do not interest the investors.

Similarly, if the interest rates increase, consumers may decide to reduce their consumption rate, and the

benefit of the investment will be lost since investing requires the consumers to spend (Dees and Brinca,

2013).

There is some scenario where a decrease in interest rates do not affect consumption and investment

spending:

1. Consumer confidence – This is when consumers are purchasing a greater amount of goods and

services regardless of their current financial status. This happens when they are confident about

the economic conditions and their future financial status, thus affecting the consumption of the

consumers regardless of the change in interest rates.

2. Consumer Invisible hand – It occurs when the consumer is directly linked to the producers. The

consumer engages in bidding before getting the goods. The scarce resources in the economy are

continuously arranged by the producer to the consumer. This raises the standards of consumers,

bringing more wealth to the consumer and their income remains the same. Even if the interest

rates reduce, it won't affect the consumer's investment and consumption spending.

Question 4

lowest in September 2007 to December 2008. Since then, it has maintained rate equal or less than 6 %.

Inflation rate have been increasing and decreasing without any steady rate. It increased to its highest in

between July 1981 to September 1982 and March 2000 to June 2001. It had the lowest rate in Dec 1983.

It can also be noticed that inflation rate has been maintain a rate less than 4 % (Berentsen, Menzio, and

Wright, 2011).

Part B

Question 3

The formula of obtaining aggregate expenditure is; Aggregate Expenditure = C + I + G + NX, where C is

the consumption, I is the investment, G is government spending, and NX is net exports which are exports

minus imports.

Normally, when the interest rate rises, the investment rises. This means that a rise in the interest rates

would lead to an increase in the amount obtained after investing.

Conversely, when the interest rates reduce, the investments also reduce. This is because the interest

rates do not interest the investors.

Similarly, if the interest rates increase, consumers may decide to reduce their consumption rate, and the

benefit of the investment will be lost since investing requires the consumers to spend (Dees and Brinca,

2013).

There is some scenario where a decrease in interest rates do not affect consumption and investment

spending:

1. Consumer confidence – This is when consumers are purchasing a greater amount of goods and

services regardless of their current financial status. This happens when they are confident about

the economic conditions and their future financial status, thus affecting the consumption of the

consumers regardless of the change in interest rates.

2. Consumer Invisible hand – It occurs when the consumer is directly linked to the producers. The

consumer engages in bidding before getting the goods. The scarce resources in the economy are

continuously arranged by the producer to the consumer. This raises the standards of consumers,

bringing more wealth to the consumer and their income remains the same. Even if the interest

rates reduce, it won't affect the consumer's investment and consumption spending.

Question 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

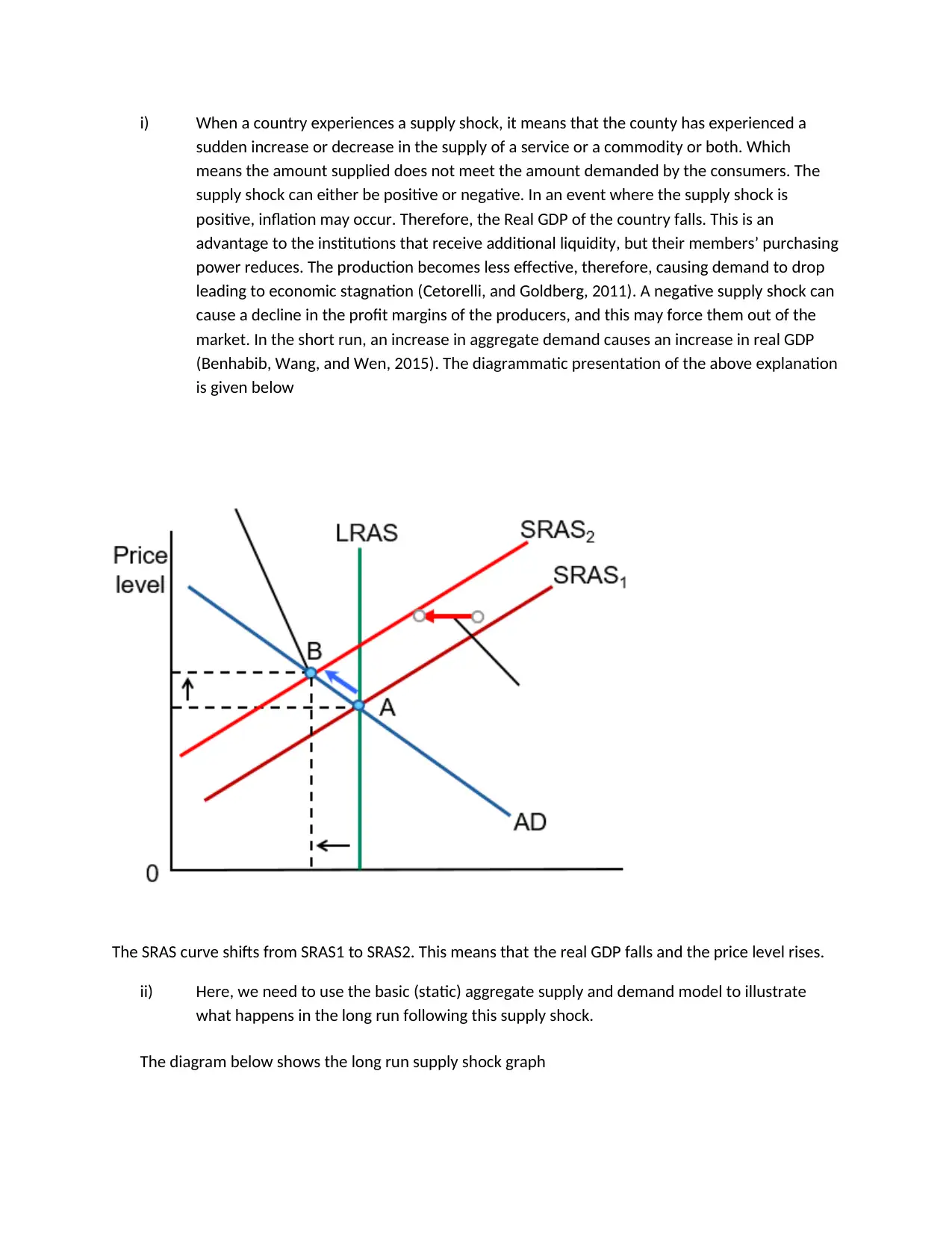

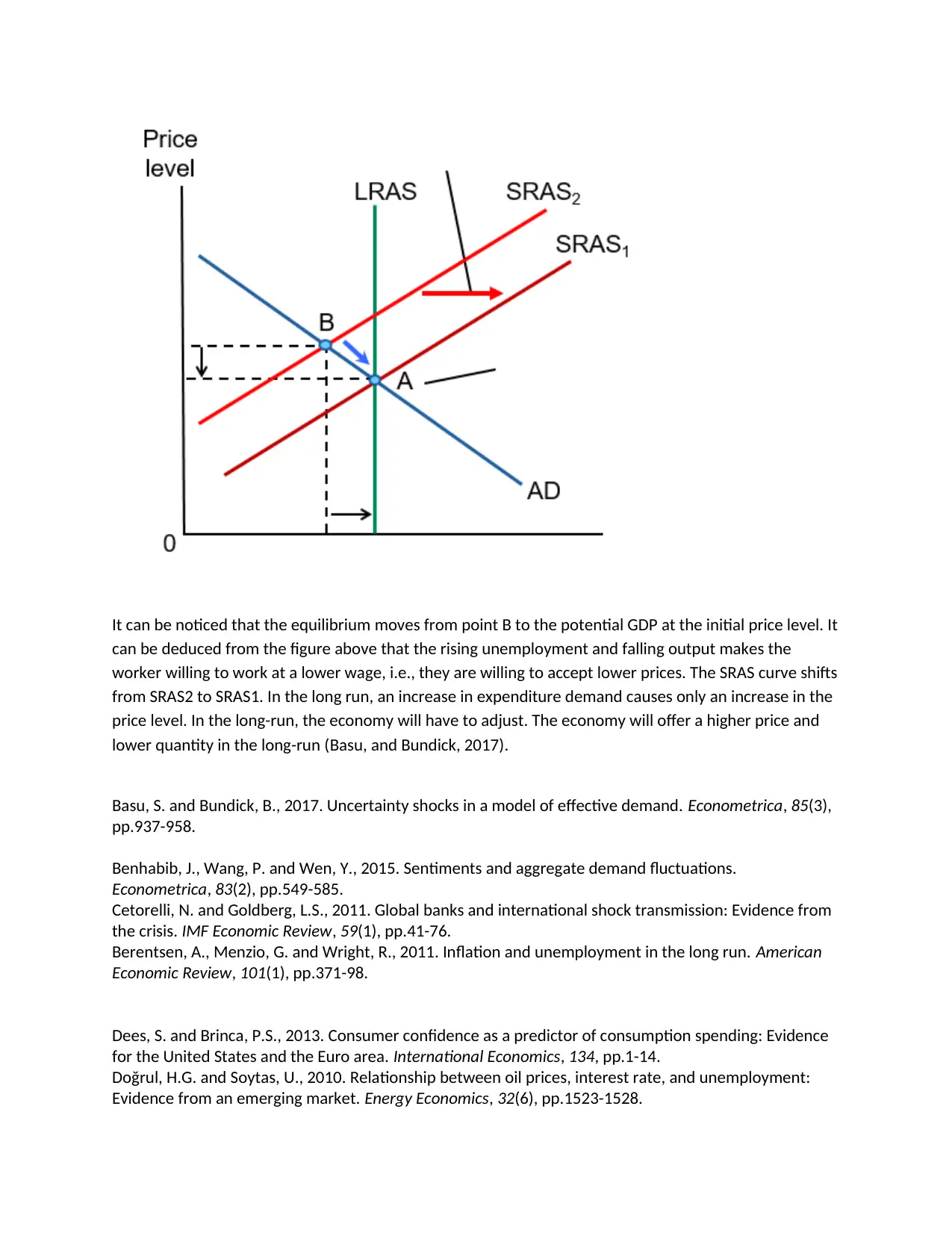

i) When a country experiences a supply shock, it means that the county has experienced a

sudden increase or decrease in the supply of a service or a commodity or both. Which

means the amount supplied does not meet the amount demanded by the consumers. The

supply shock can either be positive or negative. In an event where the supply shock is

positive, inflation may occur. Therefore, the Real GDP of the country falls. This is an

advantage to the institutions that receive additional liquidity, but their members’ purchasing

power reduces. The production becomes less effective, therefore, causing demand to drop

leading to economic stagnation (Cetorelli, and Goldberg, 2011). A negative supply shock can

cause a decline in the profit margins of the producers, and this may force them out of the

market. In the short run, an increase in aggregate demand causes an increase in real GDP

(Benhabib, Wang, and Wen, 2015). The diagrammatic presentation of the above explanation

is given below

The SRAS curve shifts from SRAS1 to SRAS2. This means that the real GDP falls and the price level rises.

ii) Here, we need to use the basic (static) aggregate supply and demand model to illustrate

what happens in the long run following this supply shock.

The diagram below shows the long run supply shock graph

sudden increase or decrease in the supply of a service or a commodity or both. Which

means the amount supplied does not meet the amount demanded by the consumers. The

supply shock can either be positive or negative. In an event where the supply shock is

positive, inflation may occur. Therefore, the Real GDP of the country falls. This is an

advantage to the institutions that receive additional liquidity, but their members’ purchasing

power reduces. The production becomes less effective, therefore, causing demand to drop

leading to economic stagnation (Cetorelli, and Goldberg, 2011). A negative supply shock can

cause a decline in the profit margins of the producers, and this may force them out of the

market. In the short run, an increase in aggregate demand causes an increase in real GDP

(Benhabib, Wang, and Wen, 2015). The diagrammatic presentation of the above explanation

is given below

The SRAS curve shifts from SRAS1 to SRAS2. This means that the real GDP falls and the price level rises.

ii) Here, we need to use the basic (static) aggregate supply and demand model to illustrate

what happens in the long run following this supply shock.

The diagram below shows the long run supply shock graph

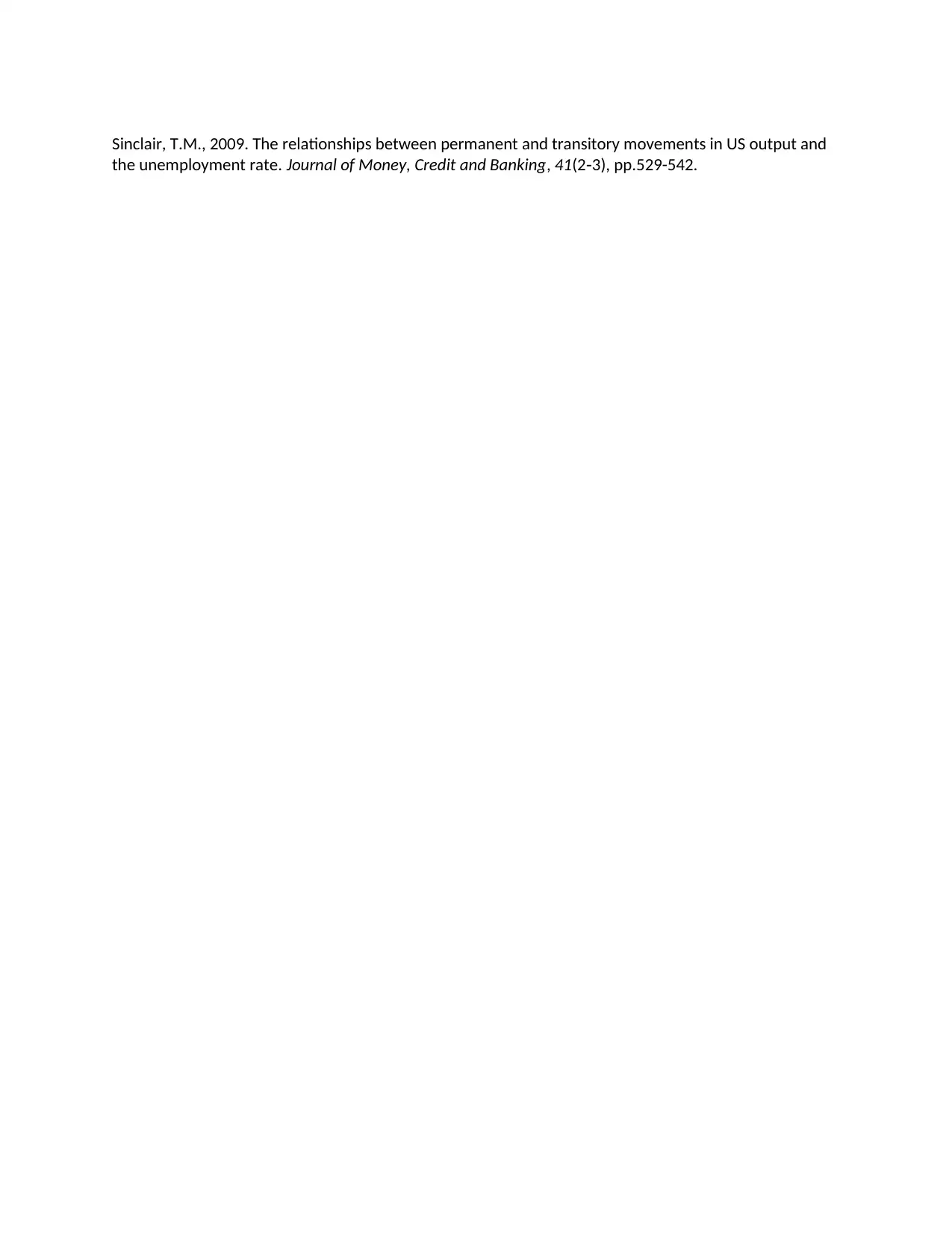

It can be noticed that the equilibrium moves from point B to the potential GDP at the initial price level. It

can be deduced from the figure above that the rising unemployment and falling output makes the

worker willing to work at a lower wage, i.e., they are willing to accept lower prices. The SRAS curve shifts

from SRAS2 to SRAS1. In the long run, an increase in expenditure demand causes only an increase in the

price level. In the long-run, the economy will have to adjust. The economy will offer a higher price and

lower quantity in the long-run (Basu, and Bundick, 2017).

Basu, S. and Bundick, B., 2017. Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand. Econometrica, 85(3),

pp.937-958.

Benhabib, J., Wang, P. and Wen, Y., 2015. Sentiments and aggregate demand fluctuations.

Econometrica, 83(2), pp.549-585.

Cetorelli, N. and Goldberg, L.S., 2011. Global banks and international shock transmission: Evidence from

the crisis. IMF Economic Review, 59(1), pp.41-76.

Berentsen, A., Menzio, G. and Wright, R., 2011. Inflation and unemployment in the long run. American

Economic Review, 101(1), pp.371-98.

Dees, S. and Brinca, P.S., 2013. Consumer confidence as a predictor of consumption spending: Evidence

for the United States and the Euro area. International Economics, 134, pp.1-14.

Doğrul, H.G. and Soytas, U., 2010. Relationship between oil prices, interest rate, and unemployment:

Evidence from an emerging market. Energy Economics, 32(6), pp.1523-1528.

can be deduced from the figure above that the rising unemployment and falling output makes the

worker willing to work at a lower wage, i.e., they are willing to accept lower prices. The SRAS curve shifts

from SRAS2 to SRAS1. In the long run, an increase in expenditure demand causes only an increase in the

price level. In the long-run, the economy will have to adjust. The economy will offer a higher price and

lower quantity in the long-run (Basu, and Bundick, 2017).

Basu, S. and Bundick, B., 2017. Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand. Econometrica, 85(3),

pp.937-958.

Benhabib, J., Wang, P. and Wen, Y., 2015. Sentiments and aggregate demand fluctuations.

Econometrica, 83(2), pp.549-585.

Cetorelli, N. and Goldberg, L.S., 2011. Global banks and international shock transmission: Evidence from

the crisis. IMF Economic Review, 59(1), pp.41-76.

Berentsen, A., Menzio, G. and Wright, R., 2011. Inflation and unemployment in the long run. American

Economic Review, 101(1), pp.371-98.

Dees, S. and Brinca, P.S., 2013. Consumer confidence as a predictor of consumption spending: Evidence

for the United States and the Euro area. International Economics, 134, pp.1-14.

Doğrul, H.G. and Soytas, U., 2010. Relationship between oil prices, interest rate, and unemployment:

Evidence from an emerging market. Energy Economics, 32(6), pp.1523-1528.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Sinclair, T.M., 2009. The relationships between permanent and transitory movements in US output and

the unemployment rate. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 41(2 3), pp.529-542.‐

the unemployment rate. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 41(2 3), pp.529-542.‐

1 out of 7

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.