Comparative Analysis of Agricultural Subsidy Programs: China & India

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/19

|19

|4746

|66

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a detailed comparative analysis of agricultural subsidy programs in China and India. It begins with an executive summary highlighting the shift in China's policy from taxation to subsidies for farmers, and the lack of household-level surveys to assess the program's impact. The report then delves into case studies of both countries, examining the rationale behind agricultural subsidies and the different approaches taken. In India's case, the report discusses the input subsidies and their unsustainability, advocating for institutional and price reforms. The Chinese case study explores the multi-step implementation of subsidy policies, from the central government to the local level, and the mechanisms for transferring funds to households. The negative impacts of input subsidies are also discussed, including cropping pattern effects, environmental concerns, fiscal effects, and equity issues. The report includes data analysis, such as tables illustrating subsidy awareness and fiscal impacts, and concludes with a summary of key findings. The report underscores the need for a balanced approach to agricultural subsidies to ensure their effectiveness and minimize negative consequences.

INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND ENTERPRISE

By Name

Course

Instructor

Institution

Location

Date

By Name

Course

Instructor

Institution

Location

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The national grain self-sufficiency concern, as well as the rural household incomes,

made China announce its plan of reversing its long-standing policy of subjecting farmers to

taxation in the year 2004. Instead, the government began providing the farmers with subsidies. In

the last five years, the annual records have indicated an increase in the subsidies. Despite the

historic move by the government in regard to the changes of the policies as well as the

implication of the policies of subsidies, there has never been a survey conducted at the household

level to understand the effect of this particular program(Li, Long and Liu 2015).

According to the survey which was conducted in the previous years, there is an indication

that despite the subsidies provision per unit farm area is low as per the budgetary allocation, the

subsidies are higher. Nearly all the producers have been getting them. The revision of the

subsidies is basically given to the contractors and not the tillers(Cui, Peng and Zhu 2015).

In the case of India, the analysis of the input subsidies in agriculture has indicated that

the process has actually outlived its core objective. It has actually become unsustainable. For the

resources to be released in the higher investment programs there is needed for institutional as

well as scale price reforms in India. This will assist in relieving pressure on the subsidies in India

per the terms of Exchequer. Under similar circumstances, it will be making more sense to have

the terms of trade improved for the compliments as well as agriculture through stepping up the

investments which will effectively traduce the subsidies.

Keywords: Agriculture, India, China, and subsidies.

The national grain self-sufficiency concern, as well as the rural household incomes,

made China announce its plan of reversing its long-standing policy of subjecting farmers to

taxation in the year 2004. Instead, the government began providing the farmers with subsidies. In

the last five years, the annual records have indicated an increase in the subsidies. Despite the

historic move by the government in regard to the changes of the policies as well as the

implication of the policies of subsidies, there has never been a survey conducted at the household

level to understand the effect of this particular program(Li, Long and Liu 2015).

According to the survey which was conducted in the previous years, there is an indication

that despite the subsidies provision per unit farm area is low as per the budgetary allocation, the

subsidies are higher. Nearly all the producers have been getting them. The revision of the

subsidies is basically given to the contractors and not the tillers(Cui, Peng and Zhu 2015).

In the case of India, the analysis of the input subsidies in agriculture has indicated that

the process has actually outlived its core objective. It has actually become unsustainable. For the

resources to be released in the higher investment programs there is needed for institutional as

well as scale price reforms in India. This will assist in relieving pressure on the subsidies in India

per the terms of Exchequer. Under similar circumstances, it will be making more sense to have

the terms of trade improved for the compliments as well as agriculture through stepping up the

investments which will effectively traduce the subsidies.

Keywords: Agriculture, India, China, and subsidies.

Introduction

It has been reported widely by observers in about the subject of discontent of the rural

population in China as a result of the heavy taxes and fees prior to the year 2000. The leaders of

the village were expected by the government to facilitate the processes of financing their village

operation budgets as well as local public infrastructure with the fees assessed from the villagers.

The local government in various areas reacted through imposing very heavy taxes on the

farmers. In some cases, there was payment of more than 30% of the total annual earning by

households in the form of taxes and fees(Shaffer, Wolfe and Le 2015).

During this particular period, there was little transfer by the government as a way of

financial support to the rural economy. The entire amount of the subsidies which was being

targeted by the ministry of finance was just 10 million Yuan. This amount of money was actually

small considering the population of China's rural area. The subsidy that was given to agriculture

by the central government was less than 0.007 percent of the agricultural output value. This was

equivalent to 0.1 Yuan per capita. Most of these subsidies went to the local government as well

as enterprises and it is never clear whether farmers benefited from such programs(Latruffe et al

2017).

In India, the issue of subsidies in general and in particular agricultural subsidies have

assumed significant consideration. This has actually happened because of two major reasons.

One of such reasons is the rising burden of the revenue deficit that has been responsible for the

fiscal imbalance in the state as well as central budget in the late 1980s. The neglect of the simple

principles of the economy in the sector contributed their growth processes as well as their due.

It has been reported widely by observers in about the subject of discontent of the rural

population in China as a result of the heavy taxes and fees prior to the year 2000. The leaders of

the village were expected by the government to facilitate the processes of financing their village

operation budgets as well as local public infrastructure with the fees assessed from the villagers.

The local government in various areas reacted through imposing very heavy taxes on the

farmers. In some cases, there was payment of more than 30% of the total annual earning by

households in the form of taxes and fees(Shaffer, Wolfe and Le 2015).

During this particular period, there was little transfer by the government as a way of

financial support to the rural economy. The entire amount of the subsidies which was being

targeted by the ministry of finance was just 10 million Yuan. This amount of money was actually

small considering the population of China's rural area. The subsidy that was given to agriculture

by the central government was less than 0.007 percent of the agricultural output value. This was

equivalent to 0.1 Yuan per capita. Most of these subsidies went to the local government as well

as enterprises and it is never clear whether farmers benefited from such programs(Latruffe et al

2017).

In India, the issue of subsidies in general and in particular agricultural subsidies have

assumed significant consideration. This has actually happened because of two major reasons.

One of such reasons is the rising burden of the revenue deficit that has been responsible for the

fiscal imbalance in the state as well as central budget in the late 1980s. The neglect of the simple

principles of the economy in the sector contributed their growth processes as well as their due.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

These processes of the growth have relied on the foundation of the increasingly unsustainable

fiscal processes(Xu and Lin 2017).

The burgeoning difficulties of these subsidies have been questioned by the policy-making

authorities who are trying to have the fiscal imbalance corrected. Secondly, this particular issue

about the agricultural subsidies was brought to limelight under the GATT negotiation with

Uruguay. This resulted into a lot of misinformation as well as confusion, particularly in the

initial year of such process’s confusion, was about the establishment of whether Indian

agriculture was fully taxed or subsidized-determination of whether the aggregate support was

positive or negative.

The paper has been organized in various subheadings starting with the case studies of

agricultural subsidies in India, China before analyzing both the positive as well as negative

impacts of the program in these two countries. A conclusive remark is drawn as a summary of

the key points discussed in regard to the subject topic.

Indian case study

The agricultural subsidies are usually rationalized in the overall economic context to the

extent that they play a critical role in the development simulation of any state through the

increase reduction in agriculture, investment as well as employment. The subsidies in the

countries that are developing must be construed to be more instrumental in the promotion of the

risk-taking activities of the framers as opposed to anything else. The advancement of the

subsidies is meant to promote the use of transfer income or new inputs in favor of the community

that practices farming. This is done so as to keep them in parity with those other communities

that are non-agriculturalists.

fiscal processes(Xu and Lin 2017).

The burgeoning difficulties of these subsidies have been questioned by the policy-making

authorities who are trying to have the fiscal imbalance corrected. Secondly, this particular issue

about the agricultural subsidies was brought to limelight under the GATT negotiation with

Uruguay. This resulted into a lot of misinformation as well as confusion, particularly in the

initial year of such process’s confusion, was about the establishment of whether Indian

agriculture was fully taxed or subsidized-determination of whether the aggregate support was

positive or negative.

The paper has been organized in various subheadings starting with the case studies of

agricultural subsidies in India, China before analyzing both the positive as well as negative

impacts of the program in these two countries. A conclusive remark is drawn as a summary of

the key points discussed in regard to the subject topic.

Indian case study

The agricultural subsidies are usually rationalized in the overall economic context to the

extent that they play a critical role in the development simulation of any state through the

increase reduction in agriculture, investment as well as employment. The subsidies in the

countries that are developing must be construed to be more instrumental in the promotion of the

risk-taking activities of the framers as opposed to anything else. The advancement of the

subsidies is meant to promote the use of transfer income or new inputs in favor of the community

that practices farming. This is done so as to keep them in parity with those other communities

that are non-agriculturalists.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In India, there are two ways that have been suggested to be used in the process of

subsidizing agriculture. One of such methods includes the government paying much higher

prices for the products of the agriculture that what the farmers can get under the environment of

the free market. Such higher prices are provided through the insulation of the domestic market

from the economy of the world by applying a very restrictive policy of trade. In the second

option, very crucial inputs like the irrigation water, electricity, fertilizer among others are

supplied to the farmers at prices which are below what would have been offered in the free

markets(Raynolds 2013).

Of these two alternatives that have been mentioned above, there is a preference for the

subsidies on the input is common. This is because the government is capable of deriving its

expenditure by the farming community in the ratio of their input use. The input subsidization

avoids rising of raw materials as well as food prices. This assist in avoiding the applausable

adverse effects on the growing sector of the industries. It is important to note that such an

initiative is never implemented singly but as a combination of both lower as well as higher input

and output prices respectively. India is tinkered with both output and input prices basically to

ensure that the poor are protected.

According to the data available on this program, it is argued by the pioneers that the subsidies

have been found to be efficient only at the initial stages of their adoption. Once the farmers have

become aware of the input availability then there is no need for the same program. Keeping this

particular view, the aim of this particular paper has been to analyze the impacts of such subsidy

programs in India as well as China.

subsidizing agriculture. One of such methods includes the government paying much higher

prices for the products of the agriculture that what the farmers can get under the environment of

the free market. Such higher prices are provided through the insulation of the domestic market

from the economy of the world by applying a very restrictive policy of trade. In the second

option, very crucial inputs like the irrigation water, electricity, fertilizer among others are

supplied to the farmers at prices which are below what would have been offered in the free

markets(Raynolds 2013).

Of these two alternatives that have been mentioned above, there is a preference for the

subsidies on the input is common. This is because the government is capable of deriving its

expenditure by the farming community in the ratio of their input use. The input subsidization

avoids rising of raw materials as well as food prices. This assist in avoiding the applausable

adverse effects on the growing sector of the industries. It is important to note that such an

initiative is never implemented singly but as a combination of both lower as well as higher input

and output prices respectively. India is tinkered with both output and input prices basically to

ensure that the poor are protected.

According to the data available on this program, it is argued by the pioneers that the subsidies

have been found to be efficient only at the initial stages of their adoption. Once the farmers have

become aware of the input availability then there is no need for the same program. Keeping this

particular view, the aim of this particular paper has been to analyze the impacts of such subsidy

programs in India as well as China.

China Case studies

One of the difficulties in understanding the effects or the impacts of the subsidies in

China is the varying steps in the implementation of the policies. This is because the policies

move from the central government down to the level of grassroots. According to this particular

policy, the implementation of the policy of budget allocation is done at three steps(Kazukauskas,

Newman, and Sauer 2014). The first step involves the determination of the entire budget which

is allocated for the input subsidies as well as grain for the whole country which is usually done

on the basis of the province by province. This determination is usually done by the state council.

On this basis, the province which has the highest grain production index is liable to more

subsidies. At the beginning of the year, there is an announcement concerning the total amount

which will later be implemented by the ministry of the finance commonly known as MOF(Li,

Long and Liu 2015).

At the province level, there is the implementation of step two. At every province, the

department of finance at the province level will follow the same criteria or use a similar

approach. The account will be set up with the centrally provided subsidy transfers. The total

amount will then be divided among the counties but on the basis of the production of the grain

per county. The last step involves the implementation of these particular programs at the county

level. The local financial bureaus have a specific task of determining the criterion or the standard

by which the subsidy will be passed from one household to the next. Despite the fact that there is

a suggestion from one of the MOF policies that the amount allocated to each and every

household be dependent on the area coverage of each household as per grain planting, the policy

also allows the local authorities to decide on the best way to implement it.

One of the difficulties in understanding the effects or the impacts of the subsidies in

China is the varying steps in the implementation of the policies. This is because the policies

move from the central government down to the level of grassroots. According to this particular

policy, the implementation of the policy of budget allocation is done at three steps(Kazukauskas,

Newman, and Sauer 2014). The first step involves the determination of the entire budget which

is allocated for the input subsidies as well as grain for the whole country which is usually done

on the basis of the province by province. This determination is usually done by the state council.

On this basis, the province which has the highest grain production index is liable to more

subsidies. At the beginning of the year, there is an announcement concerning the total amount

which will later be implemented by the ministry of the finance commonly known as MOF(Li,

Long and Liu 2015).

At the province level, there is the implementation of step two. At every province, the

department of finance at the province level will follow the same criteria or use a similar

approach. The account will be set up with the centrally provided subsidy transfers. The total

amount will then be divided among the counties but on the basis of the production of the grain

per county. The last step involves the implementation of these particular programs at the county

level. The local financial bureaus have a specific task of determining the criterion or the standard

by which the subsidy will be passed from one household to the next. Despite the fact that there is

a suggestion from one of the MOF policies that the amount allocated to each and every

household be dependent on the area coverage of each household as per grain planting, the policy

also allows the local authorities to decide on the best way to implement it.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Subsidies transfer to each household

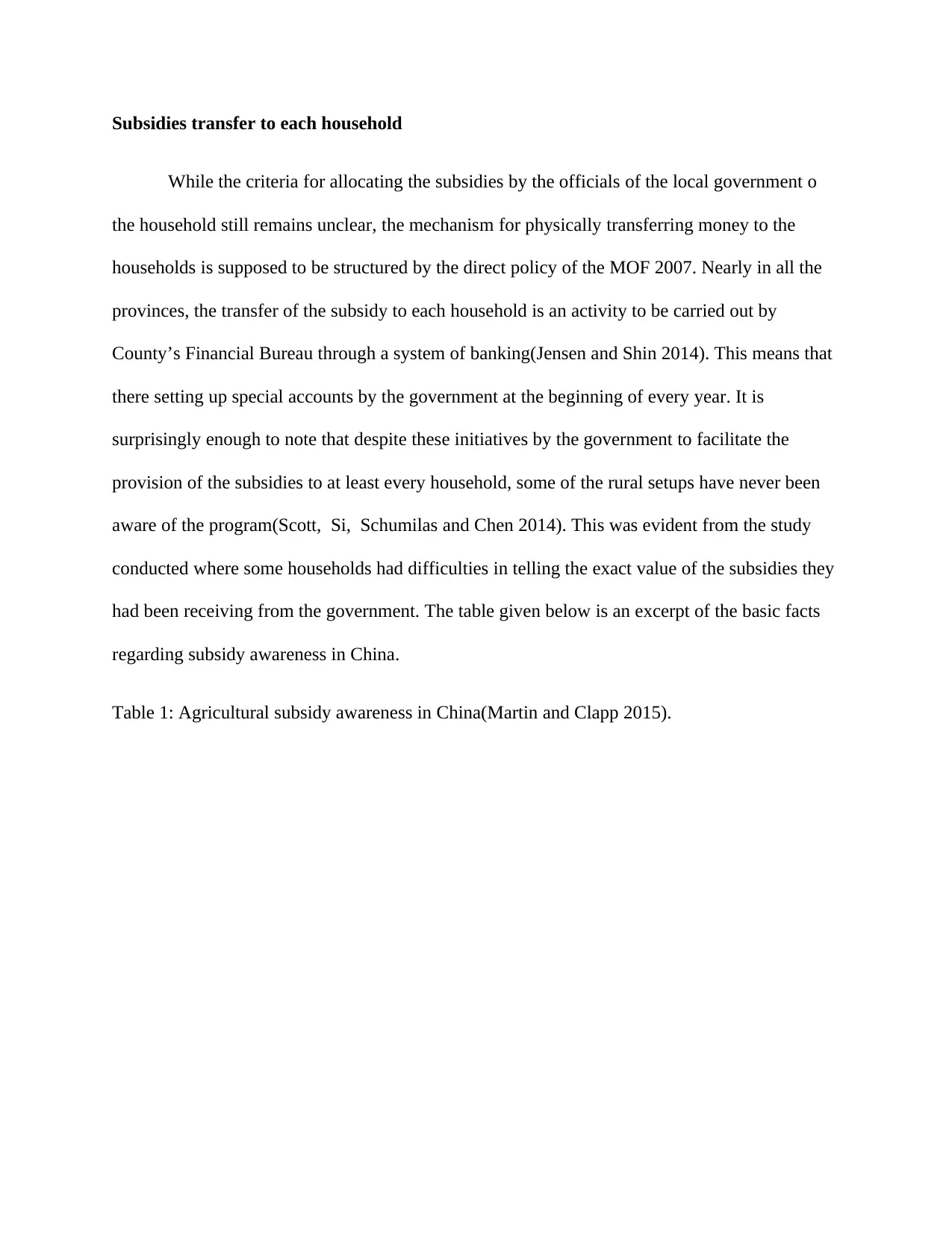

While the criteria for allocating the subsidies by the officials of the local government o

the household still remains unclear, the mechanism for physically transferring money to the

households is supposed to be structured by the direct policy of the MOF 2007. Nearly in all the

provinces, the transfer of the subsidy to each household is an activity to be carried out by

County’s Financial Bureau through a system of banking(Jensen and Shin 2014). This means that

there setting up special accounts by the government at the beginning of every year. It is

surprisingly enough to note that despite these initiatives by the government to facilitate the

provision of the subsidies to at least every household, some of the rural setups have never been

aware of the program(Scott, Si, Schumilas and Chen 2014). This was evident from the study

conducted where some households had difficulties in telling the exact value of the subsidies they

had been receiving from the government. The table given below is an excerpt of the basic facts

regarding subsidy awareness in China.

Table 1: Agricultural subsidy awareness in China(Martin and Clapp 2015).

While the criteria for allocating the subsidies by the officials of the local government o

the household still remains unclear, the mechanism for physically transferring money to the

households is supposed to be structured by the direct policy of the MOF 2007. Nearly in all the

provinces, the transfer of the subsidy to each household is an activity to be carried out by

County’s Financial Bureau through a system of banking(Jensen and Shin 2014). This means that

there setting up special accounts by the government at the beginning of every year. It is

surprisingly enough to note that despite these initiatives by the government to facilitate the

provision of the subsidies to at least every household, some of the rural setups have never been

aware of the program(Scott, Si, Schumilas and Chen 2014). This was evident from the study

conducted where some households had difficulties in telling the exact value of the subsidies they

had been receiving from the government. The table given below is an excerpt of the basic facts

regarding subsidy awareness in China.

Table 1: Agricultural subsidy awareness in China(Martin and Clapp 2015).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Negative Impact of input subsidies

Input subsidies have a lot of effects on the economy which can be categorized into cropping

pattern effect, environmental effect, fiscal effect, equity effect and effect on new industries or

technology as discussed below(Li, Banik, Tang and Wu 2014).

Direct Fiscal Effect

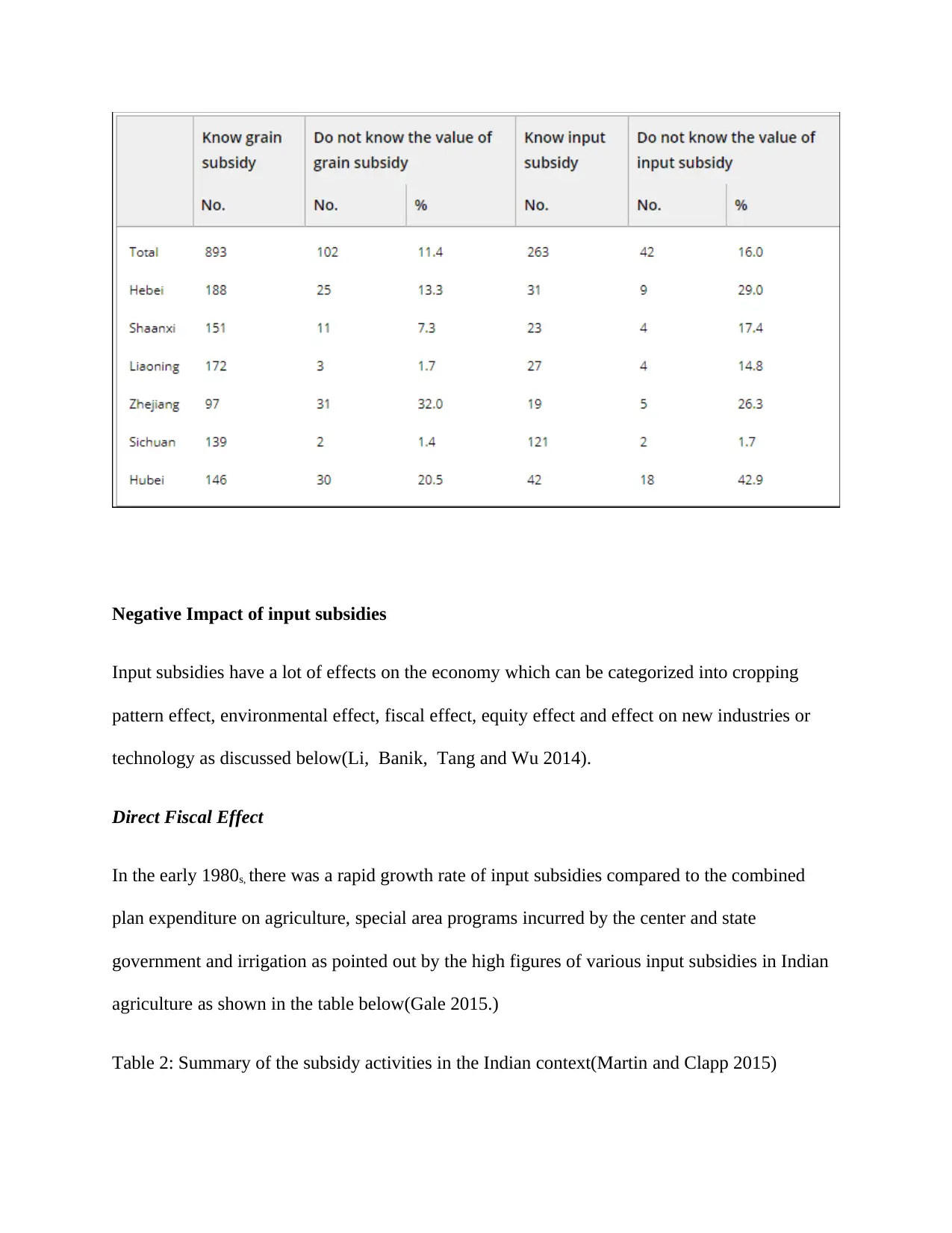

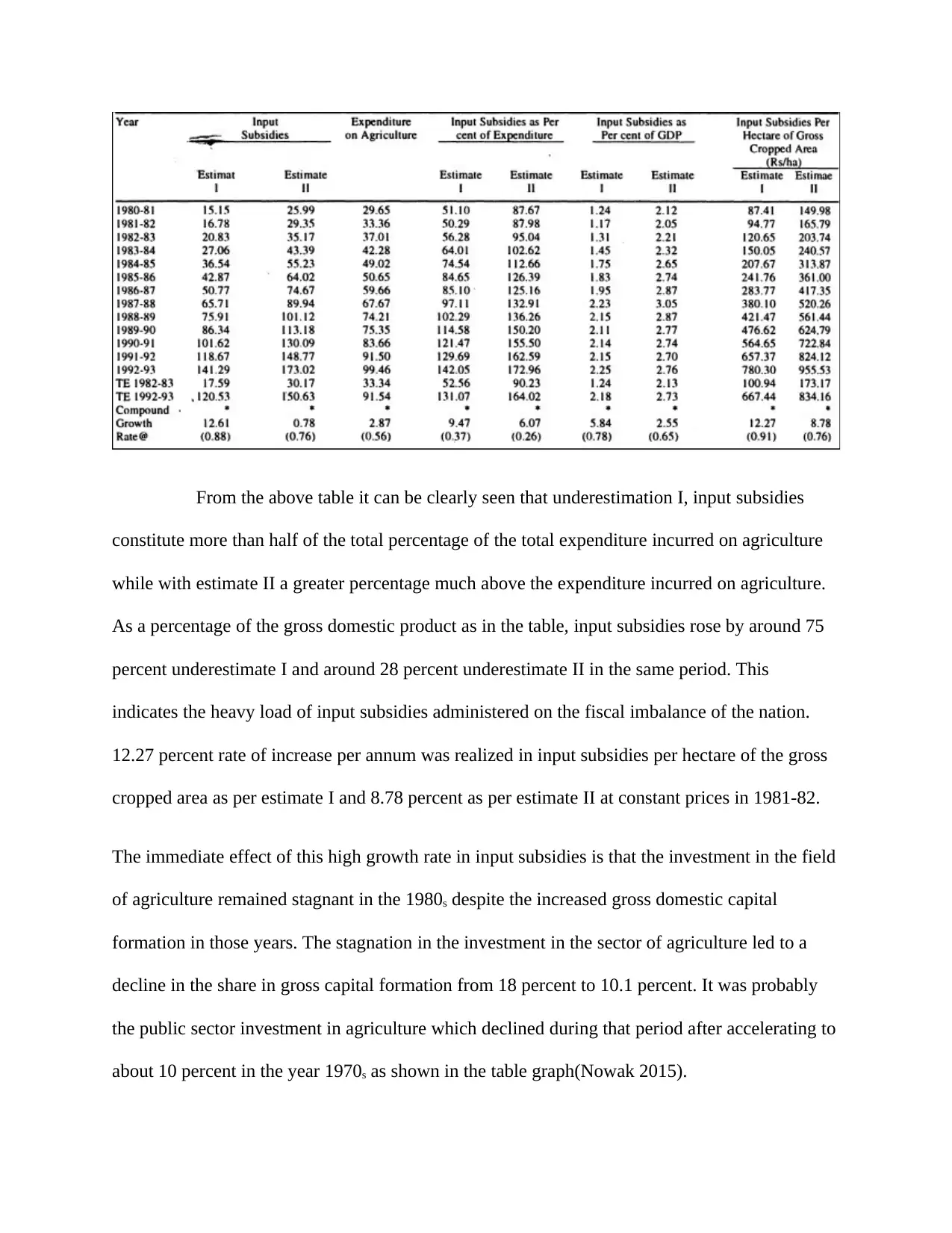

In the early 1980s, there was a rapid growth rate of input subsidies compared to the combined

plan expenditure on agriculture, special area programs incurred by the center and state

government and irrigation as pointed out by the high figures of various input subsidies in Indian

agriculture as shown in the table below(Gale 2015.)

Table 2: Summary of the subsidy activities in the Indian context(Martin and Clapp 2015)

Input subsidies have a lot of effects on the economy which can be categorized into cropping

pattern effect, environmental effect, fiscal effect, equity effect and effect on new industries or

technology as discussed below(Li, Banik, Tang and Wu 2014).

Direct Fiscal Effect

In the early 1980s, there was a rapid growth rate of input subsidies compared to the combined

plan expenditure on agriculture, special area programs incurred by the center and state

government and irrigation as pointed out by the high figures of various input subsidies in Indian

agriculture as shown in the table below(Gale 2015.)

Table 2: Summary of the subsidy activities in the Indian context(Martin and Clapp 2015)

From the above table it can be clearly seen that underestimation I, input subsidies

constitute more than half of the total percentage of the total expenditure incurred on agriculture

while with estimate II a greater percentage much above the expenditure incurred on agriculture.

As a percentage of the gross domestic product as in the table, input subsidies rose by around 75

percent underestimate I and around 28 percent underestimate II in the same period. This

indicates the heavy load of input subsidies administered on the fiscal imbalance of the nation.

12.27 percent rate of increase per annum was realized in input subsidies per hectare of the gross

cropped area as per estimate I and 8.78 percent as per estimate II at constant prices in 1981-82.

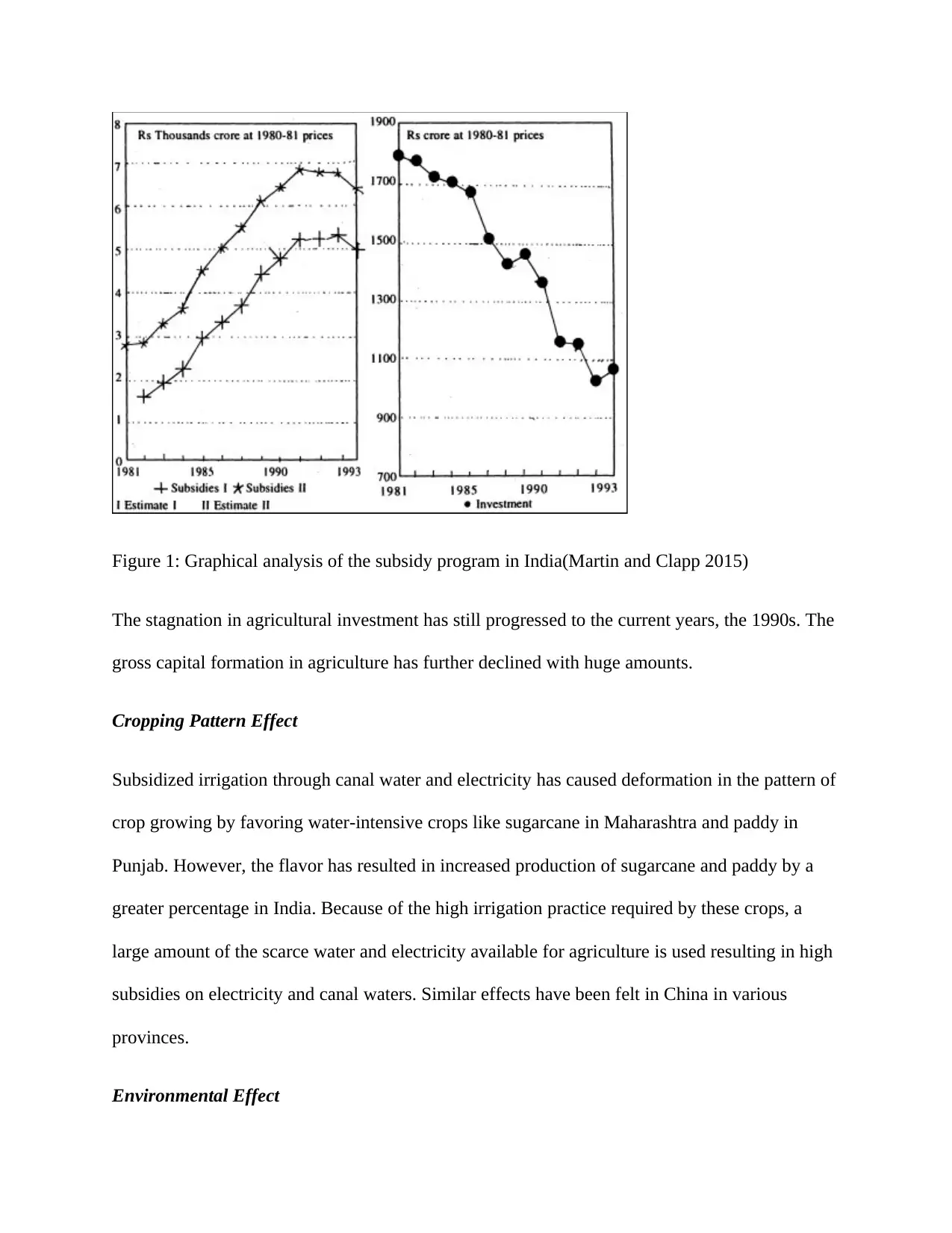

The immediate effect of this high growth rate in input subsidies is that the investment in the field

of agriculture remained stagnant in the 1980s despite the increased gross domestic capital

formation in those years. The stagnation in the investment in the sector of agriculture led to a

decline in the share in gross capital formation from 18 percent to 10.1 percent. It was probably

the public sector investment in agriculture which declined during that period after accelerating to

about 10 percent in the year 1970s as shown in the table graph(Nowak 2015).

constitute more than half of the total percentage of the total expenditure incurred on agriculture

while with estimate II a greater percentage much above the expenditure incurred on agriculture.

As a percentage of the gross domestic product as in the table, input subsidies rose by around 75

percent underestimate I and around 28 percent underestimate II in the same period. This

indicates the heavy load of input subsidies administered on the fiscal imbalance of the nation.

12.27 percent rate of increase per annum was realized in input subsidies per hectare of the gross

cropped area as per estimate I and 8.78 percent as per estimate II at constant prices in 1981-82.

The immediate effect of this high growth rate in input subsidies is that the investment in the field

of agriculture remained stagnant in the 1980s despite the increased gross domestic capital

formation in those years. The stagnation in the investment in the sector of agriculture led to a

decline in the share in gross capital formation from 18 percent to 10.1 percent. It was probably

the public sector investment in agriculture which declined during that period after accelerating to

about 10 percent in the year 1970s as shown in the table graph(Nowak 2015).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure 1: Graphical analysis of the subsidy program in India(Martin and Clapp 2015)

The stagnation in agricultural investment has still progressed to the current years, the 1990s. The

gross capital formation in agriculture has further declined with huge amounts.

Cropping Pattern Effect

Subsidized irrigation through canal water and electricity has caused deformation in the pattern of

crop growing by favoring water-intensive crops like sugarcane in Maharashtra and paddy in

Punjab. However, the flavor has resulted in increased production of sugarcane and paddy by a

greater percentage in India. Because of the high irrigation practice required by these crops, a

large amount of the scarce water and electricity available for agriculture is used resulting in high

subsidies on electricity and canal waters. Similar effects have been felt in China in various

provinces.

Environmental Effect

The stagnation in agricultural investment has still progressed to the current years, the 1990s. The

gross capital formation in agriculture has further declined with huge amounts.

Cropping Pattern Effect

Subsidized irrigation through canal water and electricity has caused deformation in the pattern of

crop growing by favoring water-intensive crops like sugarcane in Maharashtra and paddy in

Punjab. However, the flavor has resulted in increased production of sugarcane and paddy by a

greater percentage in India. Because of the high irrigation practice required by these crops, a

large amount of the scarce water and electricity available for agriculture is used resulting in high

subsidies on electricity and canal waters. Similar effects have been felt in China in various

provinces.

Environmental Effect

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

High input subsidies promote environmental degradation and unsustainable growth. The

subsidy on electricity and canal waters has resulted in excessive irrigation causing waterlogging

and salinity in some areas overdraft and depletion of groundwater in other areas. There are signs

of spread of salinity, reduced water table, and an increased level of fluorides in water as a result

of subsidy. As pointed out by some explorers, the water table in Punjab is declining at a higher

rate estimated to be around 0.3 to 0.5 meter per annum. A scholar who keenly observed this rapid

rate of decline in water level stated that if it continues at the same pace, large parts of Gujarat

may succumb to the forces of desertification(Patil et al 2014).

Subsidy in agriculture has also resulted in excessive fertilizer application adversely affecting the

environment. In Punjab, though a lot of fertilizers were not used, large quantities of nitrogen

were used instead for growing rice and wheat which reached above the recommended levels of

PAU. When nitrogen is used in this large amount some remain unutilized in the soil eventually

contributing to the groundwater pollution(Huang, Wang and Rozelle 2013). In areas which

prove to be less productive, farmers tend to apply a lot of fertilizer rather than managing

fertilizer and other inputs more efficiently.

Equity Impact

Input subsidies have raised equity questions as to who are the beneficiaries of these

subsidies and if they are promoting regional equity. The decision to continue with input subsidies

on the grounds of their distributive effects appears to be invalid(Huang and Rozelle 2015). For

instance, in case of fertilizer estimation shows that around 52 percent of the budget subsidy goes

to the farmers while the remaining percentage may be seen to go to the fertilizer industry or the

industry that supplies the fertilizer industry with materials. For the case of irrigation, the bulk of

subsidy on electricity and canal waters has resulted in excessive irrigation causing waterlogging

and salinity in some areas overdraft and depletion of groundwater in other areas. There are signs

of spread of salinity, reduced water table, and an increased level of fluorides in water as a result

of subsidy. As pointed out by some explorers, the water table in Punjab is declining at a higher

rate estimated to be around 0.3 to 0.5 meter per annum. A scholar who keenly observed this rapid

rate of decline in water level stated that if it continues at the same pace, large parts of Gujarat

may succumb to the forces of desertification(Patil et al 2014).

Subsidy in agriculture has also resulted in excessive fertilizer application adversely affecting the

environment. In Punjab, though a lot of fertilizers were not used, large quantities of nitrogen

were used instead for growing rice and wheat which reached above the recommended levels of

PAU. When nitrogen is used in this large amount some remain unutilized in the soil eventually

contributing to the groundwater pollution(Huang, Wang and Rozelle 2013). In areas which

prove to be less productive, farmers tend to apply a lot of fertilizer rather than managing

fertilizer and other inputs more efficiently.

Equity Impact

Input subsidies have raised equity questions as to who are the beneficiaries of these

subsidies and if they are promoting regional equity. The decision to continue with input subsidies

on the grounds of their distributive effects appears to be invalid(Huang and Rozelle 2015). For

instance, in case of fertilizer estimation shows that around 52 percent of the budget subsidy goes

to the farmers while the remaining percentage may be seen to go to the fertilizer industry or the

industry that supplies the fertilizer industry with materials. For the case of irrigation, the bulk of

input subsidy has been experienced in the irrigated areas in agricultural growth with the impact

not only being inter-crop parity but also inter-region and inter-class equity(Martin and Clapp

2015).

A researcher found that the most share of input subsidy came as a result of fewer well-

developed and well-watered regions(Li, Ou, and Chen 2014). This has led to the neglect of

unfavorable areas which should be given priority in the strategy of development due to the

widespread of poverty in those areas. In regard to the distribution of subsidies among different

categories of farms, it can be concluded that large farmers contribute to the greater part of input

subsidy effects while in relation to the share in the total cropped area it is revealed that the small

farmers have the greater share in the subsidies(Narayanan 2014).

Impact on Technology or New Industries

In cases where the input price does not reflect their scarcity value, farmers may find it

difficult to adopt methods which can make more efficient use of scarce resources. The rise in

subsidies in such cases will facilitate the inefficiencies which inhibit water or energy saving

devices discouraging industries which could have manufactured these devices. High rise in

subsidies in fertilizer and irrigation has made seed-water-fertilizer technology relatively more

attractive than bio-technology slowing down the potential growth in biotechnology. Subsidies on

chemical fertilizers restrict the use of manures and bio-fertilizers. A dry farming area also

remains unattractive due to cheap irrigation water in those areas(Zhang, Oya and Ye 2015).

The above discussions show how subsidies have interfered with resources which could

be used in the creation of productive potentials indicating that it has crowded the productive

investments in agriculture. Continued subsidies have also distorted the production baskets of the

not only being inter-crop parity but also inter-region and inter-class equity(Martin and Clapp

2015).

A researcher found that the most share of input subsidy came as a result of fewer well-

developed and well-watered regions(Li, Ou, and Chen 2014). This has led to the neglect of

unfavorable areas which should be given priority in the strategy of development due to the

widespread of poverty in those areas. In regard to the distribution of subsidies among different

categories of farms, it can be concluded that large farmers contribute to the greater part of input

subsidy effects while in relation to the share in the total cropped area it is revealed that the small

farmers have the greater share in the subsidies(Narayanan 2014).

Impact on Technology or New Industries

In cases where the input price does not reflect their scarcity value, farmers may find it

difficult to adopt methods which can make more efficient use of scarce resources. The rise in

subsidies in such cases will facilitate the inefficiencies which inhibit water or energy saving

devices discouraging industries which could have manufactured these devices. High rise in

subsidies in fertilizer and irrigation has made seed-water-fertilizer technology relatively more

attractive than bio-technology slowing down the potential growth in biotechnology. Subsidies on

chemical fertilizers restrict the use of manures and bio-fertilizers. A dry farming area also

remains unattractive due to cheap irrigation water in those areas(Zhang, Oya and Ye 2015).

The above discussions show how subsidies have interfered with resources which could

be used in the creation of productive potentials indicating that it has crowded the productive

investments in agriculture. Continued subsidies have also distorted the production baskets of the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.