PG Program: Inter, Intra, and Transprofessional Practice in Profession

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|7

|6404

|485

Essay

AI Summary

This essay critically evaluates the main themes in professional practice literature, including interprofessional, intraprofessional, and transprofessional practice, and discusses how these concepts apply to the author's professional practice. It also explores a challenging aspect of their professional practice and considers potential solutions to enhance it. The essay references a seven-phase procedure outlined by Jabareen [14], with specific procedures modified according to the nature and requirements of the current study [14]. The author reflects on interprofessional collaboration (IPC) which is a complex and multidimensional process in which different professionals work together to positively impact health care. The work raises some interesting points for discussion, and some personal reflections. However, the essay consists mostly of a collection of abstract generalised statements in need of supporting evidence and referencing in many places. Evidence could be in the form of supporting materials from the course and/or real examples from your practice.

http://informahealthcare.com/dre

ISSN 0963-8288 print/ISSN 1464-5165 online

DisabilRehabil,Early Online:1–7

! 2014 Informa UK Ltd.DOI:10.3109/09638288.2014.918193

EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Interprofessionalcollaboration:development of a tool to enhance

knowledge translation

Emmanuelle Careau1,2

, Nathalie Brie`re3, Nathalie Houle2, Serge Dumont3,4

, Claude Vincent1,2

, and Bonnie Swaine5,6

1Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and SocialIntegration (CIRRIS),Quebec City,Quebec,Canada,2Faculty of Medicine,

Universite´ Laval, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada,3Centre de Sante´ et Services Sociaux de la Vieille-Capitale, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada,4School of

SocialWork,Universite´ Laval,Quebec City,Quebec,Canada,5Schoolof Rehabilitation,Universite´ de Montre´al, Montre´al, Quebec,Canada,and

6Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation of Greater Montreal(CRIR),Quebec City,Quebec,Canada

Abstract

Purpose:Interprofessionalcollaboration (IPC)is a complex and multidimensionalprocess in

which differentprofessionalswork togetherto positively impacthealth care.In order to

enhance the knowledge translation and improve rehabilitation practitioners’knowledge and

skills toward IPC, it is essential to develop a comprehensive tool that illustrates how IPC should

be operationalized in clinicalsettings.Thus,this study aims atdeveloping,validating and

assessing the usefulnessof a comprehensive framework illustrating how the interactional

factors should be operationalized in clinicalsettings to promote good collaboration.Methods:

This article presents a mixed-method approach used to involve rehabilitation stakeholders

(n ¼ 20)in the developmentand validation ofan IPC framework according to a systematic

seven-phase procedure.Results:The final framework shows five types of practices according to

four components:the situation of the client and family, the intention underlying the

collaboration,the interaction between practitioners,and the combining of disciplinary

knowledge.Conclusion:The framework integrates the current scientific knowledge and clinical

experience regarding the conceptualization of IPC.It is considered as a relevant and useful KT

tool to enhance IPC knowledge for various stakeholders,especially in the rehabilitation field.

This comprehensive and contextualized framework could be used in undergraduate and

continuing education initiatives.

ä Implications for Rehabilitation

The framework developed integrates the current scientific knowledge and clinical experience

regarding the conceptualization of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) that is relevant to the

rehabilitation field.

It could be used in undergraduate and continuing education initiatives to help learners

understand the multidimensionaland dynamic nature of IPC.

It could be useful to support practitioners and managers from the rehabilitation field in their

efforts to optimize collaborative practice within their organization.

Keywords

Interprofessionalcollaboration,

interprofessionalrelations,

knowledge translation

History

Received 26 August 2013

Revised 15 April2014

Accepted 22 April2014

Published online 14 May 2014

Introduction

According to a recentreportof the World Health Organization

(WHO) (2010),the developmentof a ‘‘collaborative practice-

ready health workforce’’ is the main determinantof successful

interprofessionalcollaboration (IPC).A ‘‘collaborative practice-

ready health worker’’ is a practitioner ‘‘who has learned how to

work in an interprofessional team and who is competent to do so

(p. 7)’’ [1]. However, consulting the scientific literature, in itself,

does notnecessarily help practitioners understand clearly how

they should interactwith each otherto achieve optimalIPC

practices in a rehabilitation context.Indeed,Reeves et al.(2010)

report on the limited theory about IPC in the literature and writ

that,although all researchers generally accept that IPC improve

health and social care, few have focused on developing underly

empirically-based theory [2].Researchersoften conceptualize

IPC using a three-stage‘‘input–process–output’’architecture

derived from organizationalliteratureon team effectiveness,

mostly emphasizing inputs (determinants) and outputs (results

but ignoringthe system’sconstitution.This ‘‘black box’’

approach may be sufficientfor a simple phenomenon,butIPC

is recognized as complex,multidimensionaland evolving [3,4].

Thus,it is essentialthatrehabilitation practitioners understand

clearly whathappens ‘‘inside the box’’,i.e.how IPC should be

operationalized within different settings and with various client

Address for correspondence:Dr. Emmanuelle Careau,PhD, Center for

InterdisciplinaryResearchin Rehabilitationand Social Integration

(CIRRIS), Quebec City,Quebec,Canada.E-mail:emmanuelle.careau@

rea.ulaval.ca

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

ISSN 0963-8288 print/ISSN 1464-5165 online

DisabilRehabil,Early Online:1–7

! 2014 Informa UK Ltd.DOI:10.3109/09638288.2014.918193

EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Interprofessionalcollaboration:development of a tool to enhance

knowledge translation

Emmanuelle Careau1,2

, Nathalie Brie`re3, Nathalie Houle2, Serge Dumont3,4

, Claude Vincent1,2

, and Bonnie Swaine5,6

1Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and SocialIntegration (CIRRIS),Quebec City,Quebec,Canada,2Faculty of Medicine,

Universite´ Laval, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada,3Centre de Sante´ et Services Sociaux de la Vieille-Capitale, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada,4School of

SocialWork,Universite´ Laval,Quebec City,Quebec,Canada,5Schoolof Rehabilitation,Universite´ de Montre´al, Montre´al, Quebec,Canada,and

6Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation of Greater Montreal(CRIR),Quebec City,Quebec,Canada

Abstract

Purpose:Interprofessionalcollaboration (IPC)is a complex and multidimensionalprocess in

which differentprofessionalswork togetherto positively impacthealth care.In order to

enhance the knowledge translation and improve rehabilitation practitioners’knowledge and

skills toward IPC, it is essential to develop a comprehensive tool that illustrates how IPC should

be operationalized in clinicalsettings.Thus,this study aims atdeveloping,validating and

assessing the usefulnessof a comprehensive framework illustrating how the interactional

factors should be operationalized in clinicalsettings to promote good collaboration.Methods:

This article presents a mixed-method approach used to involve rehabilitation stakeholders

(n ¼ 20)in the developmentand validation ofan IPC framework according to a systematic

seven-phase procedure.Results:The final framework shows five types of practices according to

four components:the situation of the client and family, the intention underlying the

collaboration,the interaction between practitioners,and the combining of disciplinary

knowledge.Conclusion:The framework integrates the current scientific knowledge and clinical

experience regarding the conceptualization of IPC.It is considered as a relevant and useful KT

tool to enhance IPC knowledge for various stakeholders,especially in the rehabilitation field.

This comprehensive and contextualized framework could be used in undergraduate and

continuing education initiatives.

ä Implications for Rehabilitation

The framework developed integrates the current scientific knowledge and clinical experience

regarding the conceptualization of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) that is relevant to the

rehabilitation field.

It could be used in undergraduate and continuing education initiatives to help learners

understand the multidimensionaland dynamic nature of IPC.

It could be useful to support practitioners and managers from the rehabilitation field in their

efforts to optimize collaborative practice within their organization.

Keywords

Interprofessionalcollaboration,

interprofessionalrelations,

knowledge translation

History

Received 26 August 2013

Revised 15 April2014

Accepted 22 April2014

Published online 14 May 2014

Introduction

According to a recentreportof the World Health Organization

(WHO) (2010),the developmentof a ‘‘collaborative practice-

ready health workforce’’ is the main determinantof successful

interprofessionalcollaboration (IPC).A ‘‘collaborative practice-

ready health worker’’ is a practitioner ‘‘who has learned how to

work in an interprofessional team and who is competent to do so

(p. 7)’’ [1]. However, consulting the scientific literature, in itself,

does notnecessarily help practitioners understand clearly how

they should interactwith each otherto achieve optimalIPC

practices in a rehabilitation context.Indeed,Reeves et al.(2010)

report on the limited theory about IPC in the literature and writ

that,although all researchers generally accept that IPC improve

health and social care, few have focused on developing underly

empirically-based theory [2].Researchersoften conceptualize

IPC using a three-stage‘‘input–process–output’’architecture

derived from organizationalliteratureon team effectiveness,

mostly emphasizing inputs (determinants) and outputs (results

but ignoringthe system’sconstitution.This ‘‘black box’’

approach may be sufficientfor a simple phenomenon,butIPC

is recognized as complex,multidimensionaland evolving [3,4].

Thus,it is essentialthatrehabilitation practitioners understand

clearly whathappens ‘‘inside the box’’,i.e.how IPC should be

operationalized within different settings and with various client

Address for correspondence:Dr. Emmanuelle Careau,PhD, Center for

InterdisciplinaryResearchin Rehabilitationand Social Integration

(CIRRIS), Quebec City,Quebec,Canada.E-mail:emmanuelle.careau@

rea.ulaval.ca

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The term IPC is often defined as‘‘the processin which

differentprofessionalgroups work together to positively impact

healthcare. IPC involves a negotiatedagreementbetween

professionals which values the expertise and contributions that

various healthcare professionals bring to patientcare’’ [5,p. 2].

However,the IPC literature yieldsmany surrogate orrelated

concepts.Surrogate concepts include allthe terms thatdefine

the phenomenon,while related concepts include most,butnot

all, of the defining attributes of IPC (i.e.the concept’s essential

characteristics)[6]. Petri (2010) identifiedinterdisciplinary

collaboration,interprofessionalcollaboration,interdisciplinary

team,multidisciplinarycollaboration,interdisciplinaryteam-

work, interdisciplinarypracticeand teamworkas surrogate

concepts for IPC thatare often used interchangeably by authors

[7].Related concepts include team,integrated team,cooperative

work,cooperation,jointpractice,working group [7],teamwork

[8], cooperation,competition,compromise,avoidance,accom-

modation and conflictresolution [9].The problem is thatvery

few authors carefully define these terms,and when definitions

are provided,they are often contradictory.Nevertheless,in the

literature there are severalframeworks thatattemptto identify

the relationsbetweentheseconcepts,and thesegenerally

illustrateIPC processesalong a continuum.Some authors

depictan evolution of professionalautonomy,with autonomous

and parallelpractices atone end and a more integrated practice

at the other. Here, concept-based prefixes as defined by Leathard

[10] (e.g. uni-, multi-, inter-,trans-)are often used.Other

authorsfocuson putting in sequence process-based keywords

such as consultation,coordinationand cooperation[11].

However,theseframeworksare eitherincompleteor do not

adequately reflectthe currentstateof knowledge.Moreover,

becausethey havenot beendevelopedin order to ensure

effectiveknowledgetranslation(KT) betweenscholarsand

practitioners,it is difficult to use them for an educational

purpose.KT is defined as a dynamic and iterative process that

includes synthesis,dissemination,exchange and ethically-sound

application of knowledge [12].To develop effective educational

strategiesaiming at improvingpractitioners’knowledgeand

skills toward IPC,it is essentialto contextualize the body of

knowledge and tailorthe message and medium to the audience

[13].In this article,we describe a mixed-method approach used

to involve rehabilitationstakeholdersin the development,

validationand usefulnessassessmentof a comprehensive

framework illustrating how IPC should be operationalized in

clinicalsettings to promote good collaboration.

Methods

This initiative was partof a research projectapproved by the

ethicscommittee ofthe Institutde re´adaptation en de´ficience

physique de Que´bec (project #2008-145). To develop and validate

this new KT tool on IPC, we followed a seven-phase

procedure outlined by Jabareen [14],with specific procedures

modified according to the nature and requirements of the current

study [14].

Phase 1:Mapping the selected data sources

The first phase in developing a comprehensive framework is

to map the literatureregardingthe phenomenonbeing

studied [14].Our data sourcesconsisted ofgovernmentaland

institutionalreports, websitesof organizationsdedicated

to interprofessionaleducation/collaborativepractice(IPECP),

and journal articles retrievedfrom the Medline and

CINAHL databases with a search strategy using the keywords

‘‘interprofessionalrelations[MESH]’’; ‘‘interprofessional*’’,

multiprofessional*’’,‘‘transprofessional*’’,‘‘interdisciplinary*’’,

‘‘multidisciplinary*’’,‘‘transdisciplinar*’’1 AND ‘‘concept*’’,

‘‘model*’’, ‘‘theor*’’ ‘‘framework’’, ‘‘continuum’’, ‘‘spectrum’’.

In total,we consulted 60 journal articles,20 reports,20 clinical

guidelines,as wellas severalbooks and theses on IPECP [15].

Three of the authors(E.C., N.H., and N.B.) also attended

internationaland nationalIPECP conferencesoverthe past5

years and engagedin informaldiscussionswith attending

practitioners and scholars to better understand the phenomeno

Phase 2:Extensive reading and categorizing of the

selected data

After examining the data,E.C., N.H., and N.B.discussed their

understanding of the texts and shared information obtained du

the conferences,workshopsand informaldiscussions.They

categorized data according to theirsource (scientific literature,

clinicalguidelines,politicalreports,editorial)and theiruse of

keywords (concept-based,process-based or agency-based) [10].

Phase 3:Identifying and naming concepts

The aim in this phase is ‘‘to read and reread’’ the selected data

orderto ‘‘discover’’concepts[14]. Conceptsrelated to IPC

characteristics were identified in discussion sessions among the

authors.

Phase 4:Deconstructing and categorizing the concepts

Jabareen[14] suggestscreatinga table to ‘‘identify[each

concept’s]main attributes,characteristics,assumptions,and

role’’ (p.54).Then,we categorized the concepts and character-

istics according to ‘‘inputs’’,‘‘process’’ and ‘‘outputs’’,in order

to conserve only those related to processes for our framework.

Phase 5:Integrating concepts and Phase 6:Synthesis,

resynthesis,and making it all make sense

According to Jabareen [14],the aim of the fifth and sixth phase

‘‘is to integrate and group together concepts that have similari

to one new concept’’(p. 54) and to synthesize the remaining

concepts into a comprehensive framework.To do so, the first

author synthesized the results thus far and presented the synth

to the others. This theorization process was iterative and includ

severalcycles of synthesis,discussion and data consultation to

produce an initial framework.

Phase 7:Validating the conceptual framework

Jabareen [14] suggests seeking validation among stakeholders

presenting the framework ata conference,a seminar,or some

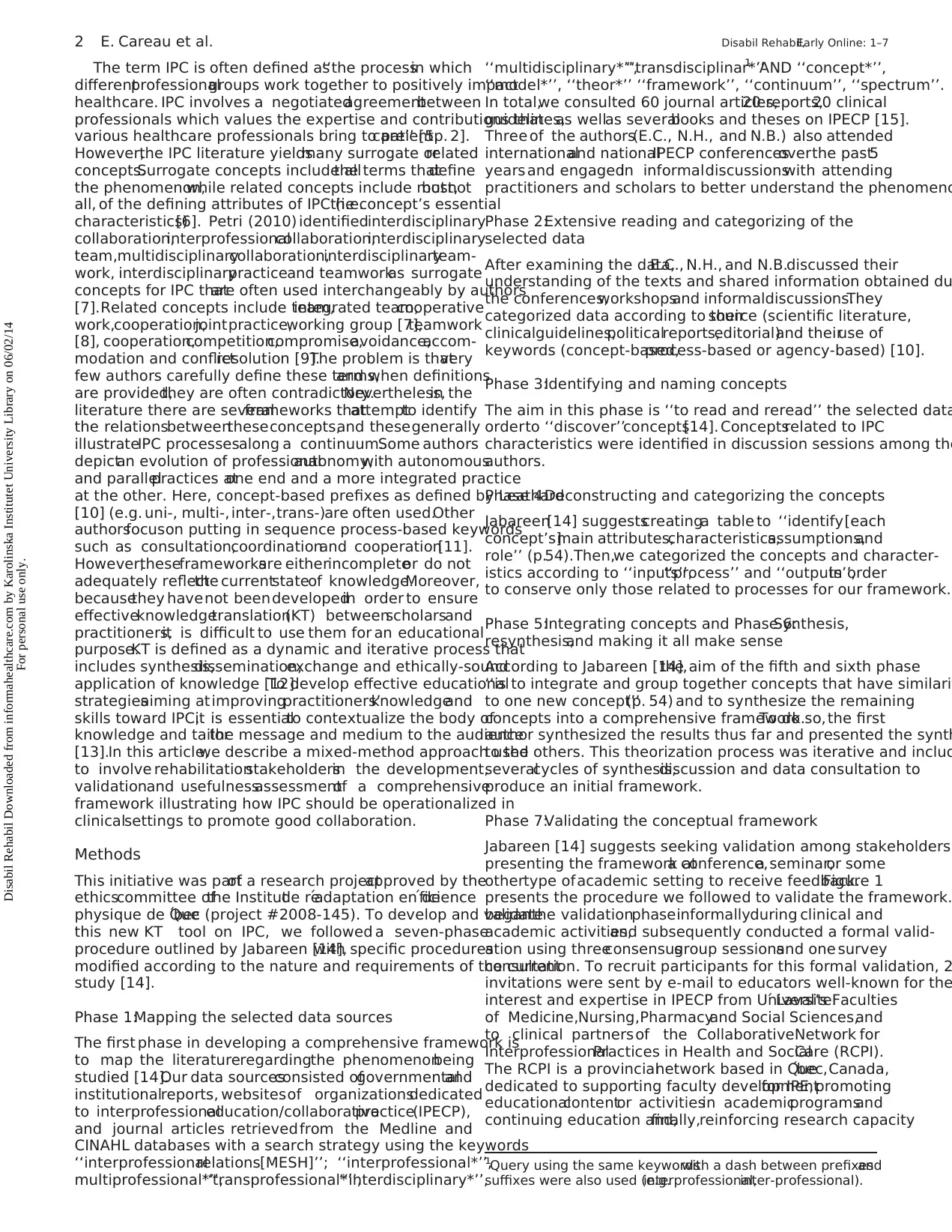

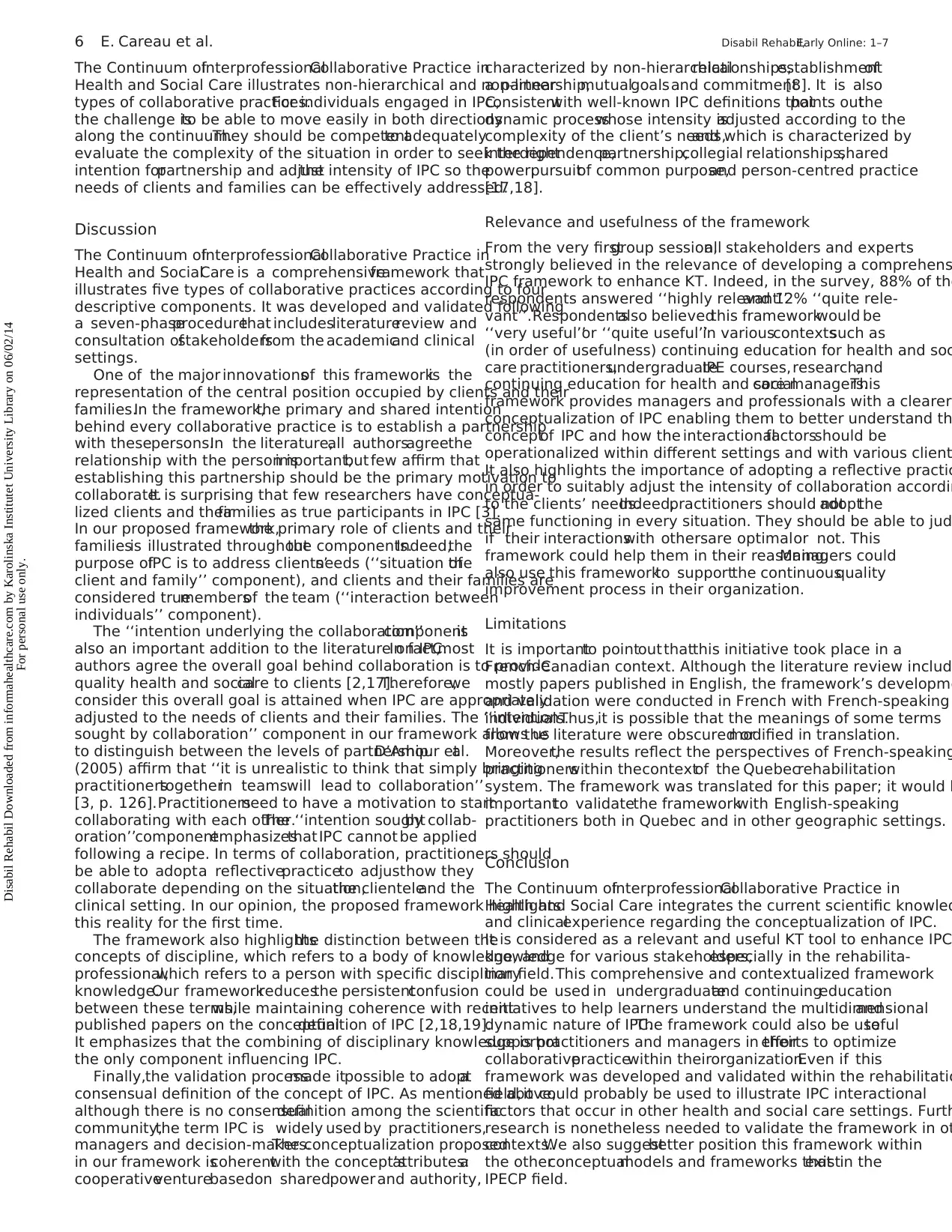

othertype ofacademic setting to receive feedback.Figure 1

presents the procedure we followed to validate the framework.

beganthe validationphaseinformallyduring clinical and

academic activities,and subsequently conducted a formal valid-

ation using threeconsensusgroup sessionsand one survey

consultation. To recruit participants for this formal validation, 2

invitations were sent by e-mail to educators well-known for the

interest and expertise in IPECP from Universite´ Laval’s Faculties

of Medicine,Nursing,Pharmacyand Social Sciences,and

to clinical partners of the CollaborativeNetwork for

InterprofessionalPractices in Health and SocialCare (RCPI).

The RCPI is a provincialnetwork based in Que´bec,Canada,

dedicated to supporting faculty developmentfor IPE,promoting

educationalcontentor activitiesin academicprogramsand

continuing education and,finally,reinforcing research capacity

1Query using the same keywordswith a dash between prefixesand

suffixes were also used (e.g.interprofessional,inter-professional).

2 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

differentprofessionalgroups work together to positively impact

healthcare. IPC involves a negotiatedagreementbetween

professionals which values the expertise and contributions that

various healthcare professionals bring to patientcare’’ [5,p. 2].

However,the IPC literature yieldsmany surrogate orrelated

concepts.Surrogate concepts include allthe terms thatdefine

the phenomenon,while related concepts include most,butnot

all, of the defining attributes of IPC (i.e.the concept’s essential

characteristics)[6]. Petri (2010) identifiedinterdisciplinary

collaboration,interprofessionalcollaboration,interdisciplinary

team,multidisciplinarycollaboration,interdisciplinaryteam-

work, interdisciplinarypracticeand teamworkas surrogate

concepts for IPC thatare often used interchangeably by authors

[7].Related concepts include team,integrated team,cooperative

work,cooperation,jointpractice,working group [7],teamwork

[8], cooperation,competition,compromise,avoidance,accom-

modation and conflictresolution [9].The problem is thatvery

few authors carefully define these terms,and when definitions

are provided,they are often contradictory.Nevertheless,in the

literature there are severalframeworks thatattemptto identify

the relationsbetweentheseconcepts,and thesegenerally

illustrateIPC processesalong a continuum.Some authors

depictan evolution of professionalautonomy,with autonomous

and parallelpractices atone end and a more integrated practice

at the other. Here, concept-based prefixes as defined by Leathard

[10] (e.g. uni-, multi-, inter-,trans-)are often used.Other

authorsfocuson putting in sequence process-based keywords

such as consultation,coordinationand cooperation[11].

However,theseframeworksare eitherincompleteor do not

adequately reflectthe currentstateof knowledge.Moreover,

becausethey havenot beendevelopedin order to ensure

effectiveknowledgetranslation(KT) betweenscholarsand

practitioners,it is difficult to use them for an educational

purpose.KT is defined as a dynamic and iterative process that

includes synthesis,dissemination,exchange and ethically-sound

application of knowledge [12].To develop effective educational

strategiesaiming at improvingpractitioners’knowledgeand

skills toward IPC,it is essentialto contextualize the body of

knowledge and tailorthe message and medium to the audience

[13].In this article,we describe a mixed-method approach used

to involve rehabilitationstakeholdersin the development,

validationand usefulnessassessmentof a comprehensive

framework illustrating how IPC should be operationalized in

clinicalsettings to promote good collaboration.

Methods

This initiative was partof a research projectapproved by the

ethicscommittee ofthe Institutde re´adaptation en de´ficience

physique de Que´bec (project #2008-145). To develop and validate

this new KT tool on IPC, we followed a seven-phase

procedure outlined by Jabareen [14],with specific procedures

modified according to the nature and requirements of the current

study [14].

Phase 1:Mapping the selected data sources

The first phase in developing a comprehensive framework is

to map the literatureregardingthe phenomenonbeing

studied [14].Our data sourcesconsisted ofgovernmentaland

institutionalreports, websitesof organizationsdedicated

to interprofessionaleducation/collaborativepractice(IPECP),

and journal articles retrievedfrom the Medline and

CINAHL databases with a search strategy using the keywords

‘‘interprofessionalrelations[MESH]’’; ‘‘interprofessional*’’,

multiprofessional*’’,‘‘transprofessional*’’,‘‘interdisciplinary*’’,

‘‘multidisciplinary*’’,‘‘transdisciplinar*’’1 AND ‘‘concept*’’,

‘‘model*’’, ‘‘theor*’’ ‘‘framework’’, ‘‘continuum’’, ‘‘spectrum’’.

In total,we consulted 60 journal articles,20 reports,20 clinical

guidelines,as wellas severalbooks and theses on IPECP [15].

Three of the authors(E.C., N.H., and N.B.) also attended

internationaland nationalIPECP conferencesoverthe past5

years and engagedin informaldiscussionswith attending

practitioners and scholars to better understand the phenomeno

Phase 2:Extensive reading and categorizing of the

selected data

After examining the data,E.C., N.H., and N.B.discussed their

understanding of the texts and shared information obtained du

the conferences,workshopsand informaldiscussions.They

categorized data according to theirsource (scientific literature,

clinicalguidelines,politicalreports,editorial)and theiruse of

keywords (concept-based,process-based or agency-based) [10].

Phase 3:Identifying and naming concepts

The aim in this phase is ‘‘to read and reread’’ the selected data

orderto ‘‘discover’’concepts[14]. Conceptsrelated to IPC

characteristics were identified in discussion sessions among the

authors.

Phase 4:Deconstructing and categorizing the concepts

Jabareen[14] suggestscreatinga table to ‘‘identify[each

concept’s]main attributes,characteristics,assumptions,and

role’’ (p.54).Then,we categorized the concepts and character-

istics according to ‘‘inputs’’,‘‘process’’ and ‘‘outputs’’,in order

to conserve only those related to processes for our framework.

Phase 5:Integrating concepts and Phase 6:Synthesis,

resynthesis,and making it all make sense

According to Jabareen [14],the aim of the fifth and sixth phase

‘‘is to integrate and group together concepts that have similari

to one new concept’’(p. 54) and to synthesize the remaining

concepts into a comprehensive framework.To do so, the first

author synthesized the results thus far and presented the synth

to the others. This theorization process was iterative and includ

severalcycles of synthesis,discussion and data consultation to

produce an initial framework.

Phase 7:Validating the conceptual framework

Jabareen [14] suggests seeking validation among stakeholders

presenting the framework ata conference,a seminar,or some

othertype ofacademic setting to receive feedback.Figure 1

presents the procedure we followed to validate the framework.

beganthe validationphaseinformallyduring clinical and

academic activities,and subsequently conducted a formal valid-

ation using threeconsensusgroup sessionsand one survey

consultation. To recruit participants for this formal validation, 2

invitations were sent by e-mail to educators well-known for the

interest and expertise in IPECP from Universite´ Laval’s Faculties

of Medicine,Nursing,Pharmacyand Social Sciences,and

to clinical partners of the CollaborativeNetwork for

InterprofessionalPractices in Health and SocialCare (RCPI).

The RCPI is a provincialnetwork based in Que´bec,Canada,

dedicated to supporting faculty developmentfor IPE,promoting

educationalcontentor activitiesin academicprogramsand

continuing education and,finally,reinforcing research capacity

1Query using the same keywordswith a dash between prefixesand

suffixes were also used (e.g.interprofessional,inter-professional).

2 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

and KT on IPECP. Targeted experts and stakeholders had either a

scientificknowledgeof IPC or expertisein how IPC is

experienceddaily in clinical settings.At eachstep of the

validation process, invitations were sent to all the targeted experts

and stakeholders, but the number who were able to attend differed

at each step.Experts’ and stakeholders’ occupations and discip-

linary backgrounds are provided in Table 1.

For the informalvalidation,the initialframework (Figure 2)

was presented,between 2009 and 2010,at seven clinical IPECP

sessionsin four hospitals,two rehabilitation centres,and one

youthcentre.Between 10and 30 healthcaremanagersand

practitioners attended each session. We also presented it six times

within a mandatory IPE undergraduate course at Universite´ Laval,

involving each time between 200 and 500 students from different

disciplines.These activities provided informalfeedback on the

framework’s clarity from the perspective of healthcare managers,

practitioners,students,educators and researchers.During these

activities,questions and comments were noted and then used,

during several discussion sessions among the authors, to refine

framework.

For the formalvalidation,a firstconsensus group session of

14 IPECP expertsand stakeholdersmoderated by the fourth

author(S.D.) was organized to discussthe currentstateof

knowledge on concepts related to IPC and to identify participan

agreement and disagreement with each of the initial framework

components (Figure 2). Then, a survey with four sections was s

by e-mailto the above-mentioned 25 experts and stakeholders.

In the first section, the framework was presented and the ration

for each component was carefully explained.The second section

gathered information aboutthe respondent’s profile.The third

section,with 13 questions (open-ended and four-pointscales),

documentedthe respondent’sopinion on the relevanceof

developing a new IPC framework and the usefulnessof the

proposedframeworkin various contexts(e.g. undergraduate

IPECP courses,researchand IPECP training for healthcare

practitionersand managers).The fourth section,aimed at

measuring the level of the respondents’ agreement with differe

aspects of the framework, comprised 40 questions using a 4-po

scale (totally agree to totally disagree),two yes/no dichotomous

questions, and three open-ended questions. After each questio

space for additional comments was provided.Respondents could

answer the survey using word processing software and return i

email to the RCPI’s coordinator, or they could print it, complete

by hand,and return it by postal mail to the RCPI office.Finally,

two moreconsensusgroup sessions,involving 11 and nine

participants each,were organized to discuss the survey results,

reach consensus on a final version of the framework, and discu

its perceived usefulness in various settings.

Results

After extensive reading and discussions,three ofthe authors

(E.C., N.H. and N.B) categorized the concepts and characteristic

of IPC processes into six components:the contextthatbrings

practitionersto collaboratetogether,the objectivesof the

partnership,the typesof interactionbetweenmembers,the

integration ofdisciplinary knowledge,the modalities used,and

the competencies for IPC.They also concluded thatthe import-

anceof clientsand theirfamilies(referring broadly to both

relatives and otherloved ones)had to be emphasized in each

component.They decidedthat a continuum wasthe most

appropriate way to illustrate clearly the dynamic nature of IPC

processes.Indeed,most of the concepts and characteristics from

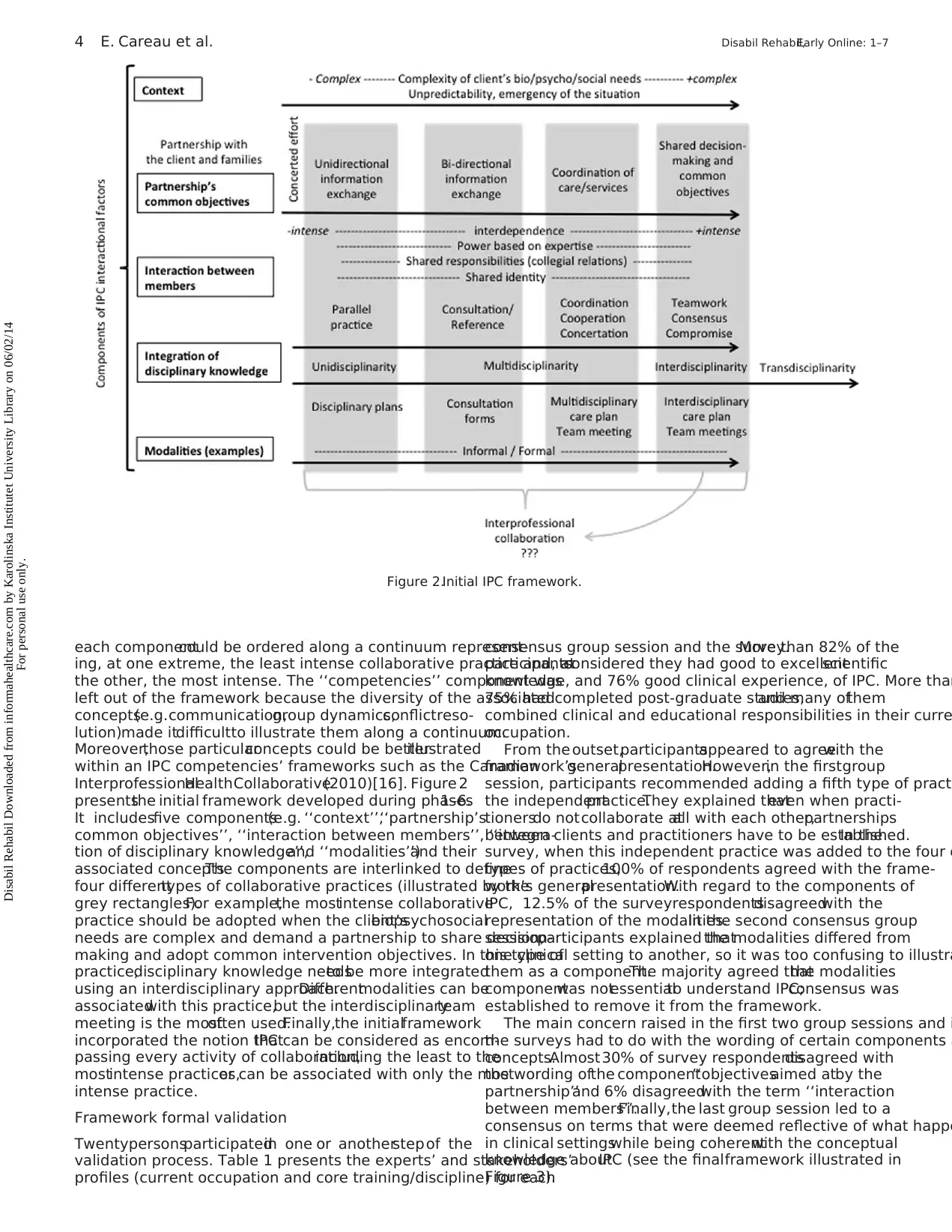

Table 1.Profiles ofexperts and stakeholders who participated in the

framework’s validation.

Group

session 1

Group

session 2

Group

session 3 Survey

Occupationa

Healthcare practitioner 3 2 1 6

Professor/Researcher 6 4 4 6

IPE teacher 2 1 1 1

Ph.D.student 1 1 0 1

Manager 1 2 1 2

Practical training supervisor 2 2 2 2

Patient representative 0 0 0 1

IPC/IPE consultant 1 1 1 1

Discipline

Occupational therapy 0 0 0 1

Kinesiology 0 0 0 1

Medicine 1 1 2 3

Pharmacy 0 1 1 1

Physical therapy 2 1 0 4

Psychology 3 2 2 4

Industrial relations 0 1 0 1

Nursing 2 1 0 1

Social work 2 2 2 1

Nutrition 1 0 0 0

TOTAL 11 9 7 17

aParticipants could choose more than one occupation.

Use in IPE clinical sessions

+

Consensus group session 1

(n=11)

Inial framework

(presented in the Results secon, Fig. 1)

Final framework

(presented in the Results secon, Fig. 3)

Use in IPE undergraduate

courses

+

Electronic survey

(n=17)

+

+

Consensus group session 2

(n=9)

+

+

Consensus group session 3

(n=7)

Informal validation Formal validation

Figure 1.Detailed framework validation procedure.

DOI: 10.3109/09638288.2014.918193 Interprofessional collaboration framework3

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

scientificknowledgeof IPC or expertisein how IPC is

experienceddaily in clinical settings.At eachstep of the

validation process, invitations were sent to all the targeted experts

and stakeholders, but the number who were able to attend differed

at each step.Experts’ and stakeholders’ occupations and discip-

linary backgrounds are provided in Table 1.

For the informalvalidation,the initialframework (Figure 2)

was presented,between 2009 and 2010,at seven clinical IPECP

sessionsin four hospitals,two rehabilitation centres,and one

youthcentre.Between 10and 30 healthcaremanagersand

practitioners attended each session. We also presented it six times

within a mandatory IPE undergraduate course at Universite´ Laval,

involving each time between 200 and 500 students from different

disciplines.These activities provided informalfeedback on the

framework’s clarity from the perspective of healthcare managers,

practitioners,students,educators and researchers.During these

activities,questions and comments were noted and then used,

during several discussion sessions among the authors, to refine

framework.

For the formalvalidation,a firstconsensus group session of

14 IPECP expertsand stakeholdersmoderated by the fourth

author(S.D.) was organized to discussthe currentstateof

knowledge on concepts related to IPC and to identify participan

agreement and disagreement with each of the initial framework

components (Figure 2). Then, a survey with four sections was s

by e-mailto the above-mentioned 25 experts and stakeholders.

In the first section, the framework was presented and the ration

for each component was carefully explained.The second section

gathered information aboutthe respondent’s profile.The third

section,with 13 questions (open-ended and four-pointscales),

documentedthe respondent’sopinion on the relevanceof

developing a new IPC framework and the usefulnessof the

proposedframeworkin various contexts(e.g. undergraduate

IPECP courses,researchand IPECP training for healthcare

practitionersand managers).The fourth section,aimed at

measuring the level of the respondents’ agreement with differe

aspects of the framework, comprised 40 questions using a 4-po

scale (totally agree to totally disagree),two yes/no dichotomous

questions, and three open-ended questions. After each questio

space for additional comments was provided.Respondents could

answer the survey using word processing software and return i

email to the RCPI’s coordinator, or they could print it, complete

by hand,and return it by postal mail to the RCPI office.Finally,

two moreconsensusgroup sessions,involving 11 and nine

participants each,were organized to discuss the survey results,

reach consensus on a final version of the framework, and discu

its perceived usefulness in various settings.

Results

After extensive reading and discussions,three ofthe authors

(E.C., N.H. and N.B) categorized the concepts and characteristic

of IPC processes into six components:the contextthatbrings

practitionersto collaboratetogether,the objectivesof the

partnership,the typesof interactionbetweenmembers,the

integration ofdisciplinary knowledge,the modalities used,and

the competencies for IPC.They also concluded thatthe import-

anceof clientsand theirfamilies(referring broadly to both

relatives and otherloved ones)had to be emphasized in each

component.They decidedthat a continuum wasthe most

appropriate way to illustrate clearly the dynamic nature of IPC

processes.Indeed,most of the concepts and characteristics from

Table 1.Profiles ofexperts and stakeholders who participated in the

framework’s validation.

Group

session 1

Group

session 2

Group

session 3 Survey

Occupationa

Healthcare practitioner 3 2 1 6

Professor/Researcher 6 4 4 6

IPE teacher 2 1 1 1

Ph.D.student 1 1 0 1

Manager 1 2 1 2

Practical training supervisor 2 2 2 2

Patient representative 0 0 0 1

IPC/IPE consultant 1 1 1 1

Discipline

Occupational therapy 0 0 0 1

Kinesiology 0 0 0 1

Medicine 1 1 2 3

Pharmacy 0 1 1 1

Physical therapy 2 1 0 4

Psychology 3 2 2 4

Industrial relations 0 1 0 1

Nursing 2 1 0 1

Social work 2 2 2 1

Nutrition 1 0 0 0

TOTAL 11 9 7 17

aParticipants could choose more than one occupation.

Use in IPE clinical sessions

+

Consensus group session 1

(n=11)

Inial framework

(presented in the Results secon, Fig. 1)

Final framework

(presented in the Results secon, Fig. 3)

Use in IPE undergraduate

courses

+

Electronic survey

(n=17)

+

+

Consensus group session 2

(n=9)

+

+

Consensus group session 3

(n=7)

Informal validation Formal validation

Figure 1.Detailed framework validation procedure.

DOI: 10.3109/09638288.2014.918193 Interprofessional collaboration framework3

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

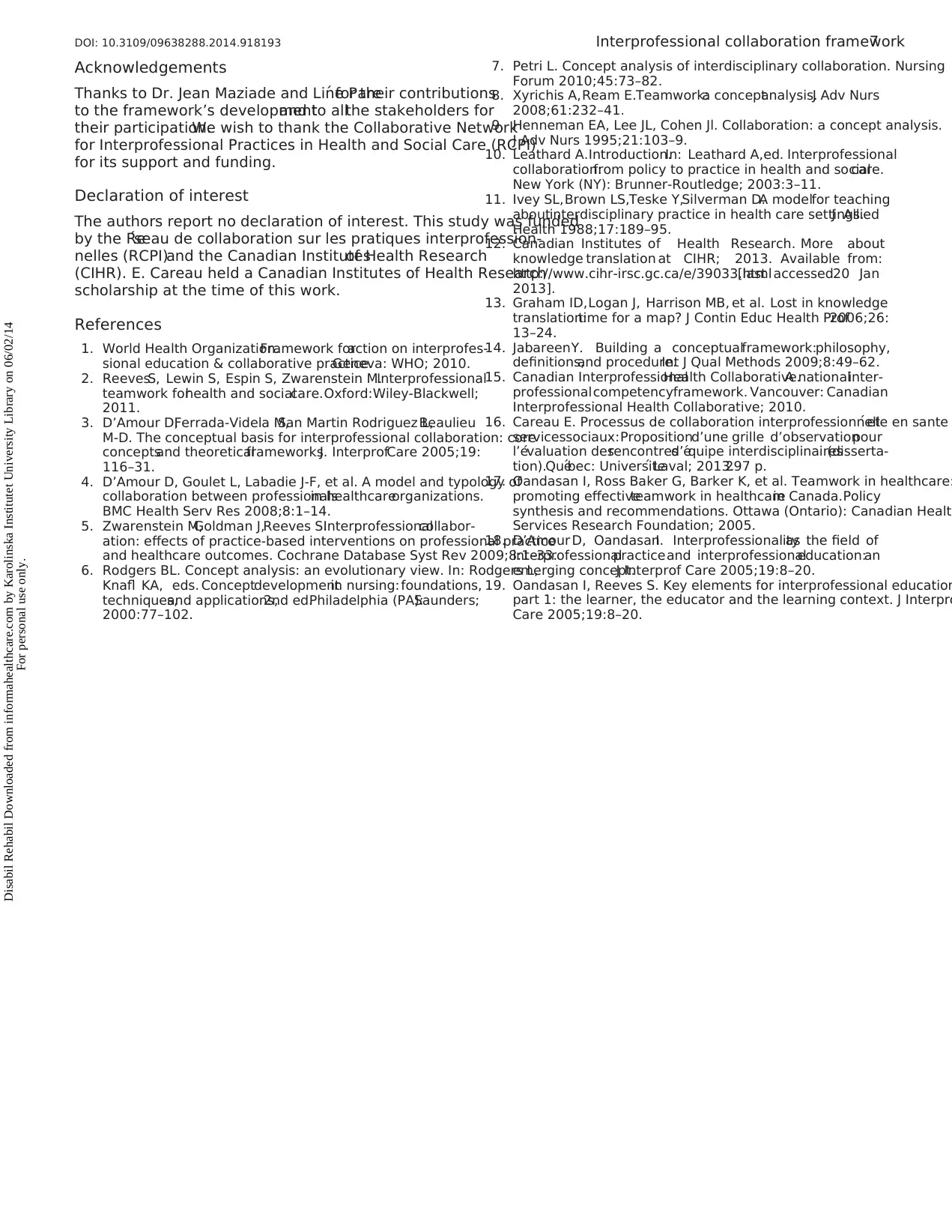

each componentcould be ordered along a continuum represent-

ing, at one extreme, the least intense collaborative practice and, at

the other, the most intense. The ‘‘competencies’’ component was

left out of the framework because the diversity of the associated

concepts(e.g.communication,group dynamics,conflictreso-

lution)made itdifficultto illustrate them along a continuum.

Moreover,those particularconcepts could be betterillustrated

within an IPC competencies’ frameworks such as the Canadian

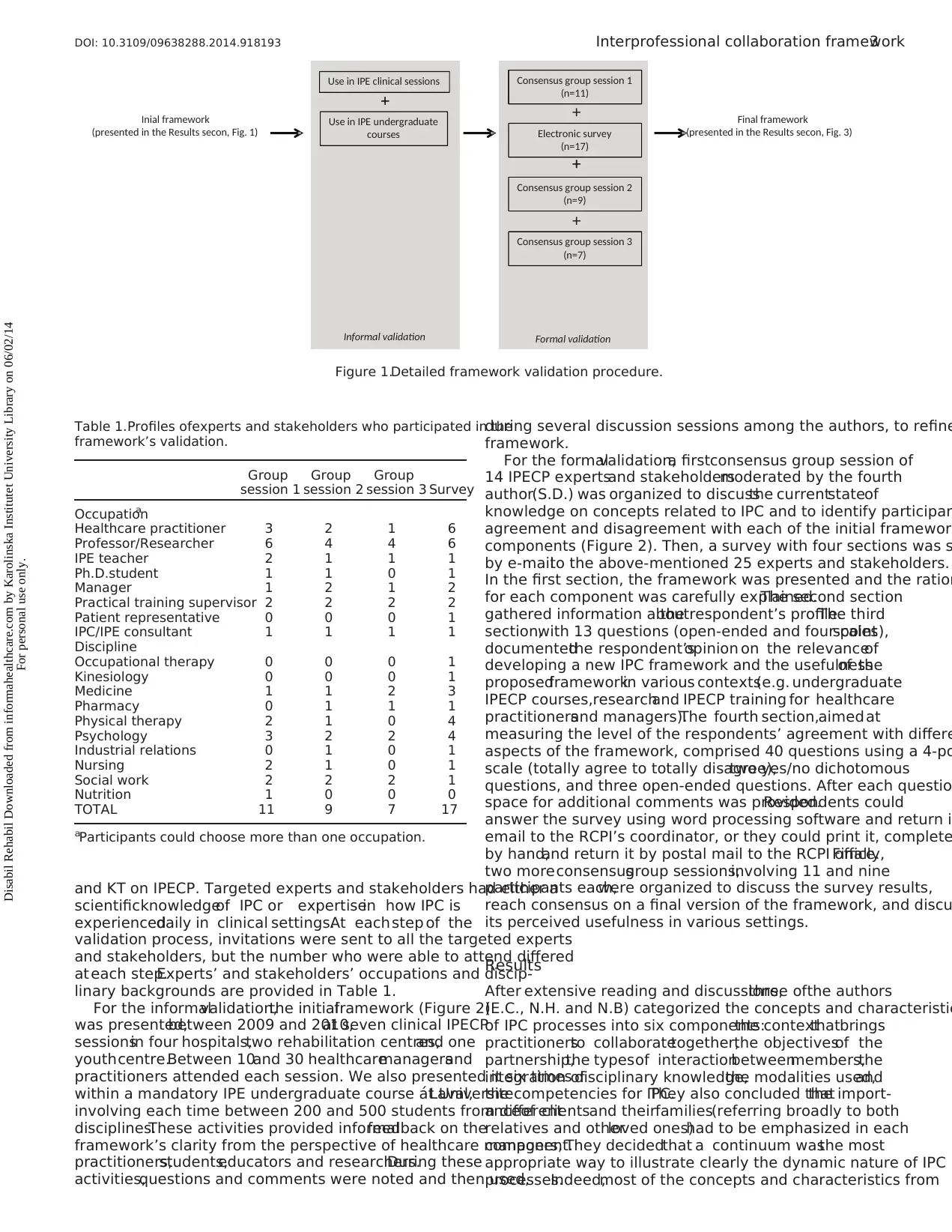

InterprofessionalHealthCollaborative(2010)[16]. Figure 2

presentsthe initial framework developed during phases1–6.

It includesfive components(e.g. ‘‘context’’,‘‘partnership’s

common objectives’’, ‘‘interaction between members’’, ‘‘integra-

tion of disciplinary knowledge’’,and ‘‘modalities’’)and their

associated concepts.The components are interlinked to define

four differenttypes of collaborative practices (illustrated by the

grey rectangles).For example,the mostintense collaborative

practice should be adopted when the client’sbiopsychosocial

needs are complex and demand a partnership to share decision-

making and adopt common intervention objectives. In this type of

practice,disciplinary knowledge needsto be more integrated

using an interdisciplinary approach.Differentmodalities can be

associatedwith this practice,but the interdisciplinaryteam

meeting is the mostoften used.Finally,the initialframework

incorporated the notion thatIPC can be considered as encom-

passing every activity of collaboration,including the least to the

mostintense practices,or can be associated with only the most

intense practice.

Framework formal validation

Twentypersonsparticipatedin one or anotherstep of the

validation process. Table 1 presents the experts’ and stakeholders’

profiles (current occupation and core training/discipline) for each

consensus group session and the survey.More than 82% of the

participantsconsidered they had good to excellentscientific

knowledge, and 76% good clinical experience, of IPC. More than

75% had completed post-graduate studies,and many ofthem

combined clinical and educational responsibilities in their curre

occupation.

From the outset,participantsappeared to agreewith the

framework’sgeneralpresentation.However,in the firstgroup

session, participants recommended adding a fifth type of pract

the independentpractice.They explained thateven when practi-

tionersdo notcollaborate atall with each other,partnerships

between clients and practitioners have to be established.In the

survey, when this independent practice was added to the four o

types of practices,100% of respondents agreed with the frame-

work’s generalpresentation.With regard to the components of

IPC, 12.5% of the surveyrespondentsdisagreedwith the

representation of the modalities.In the second consensus group

session,participants explained thatthe modalities differed from

one clinical setting to another, so it was too confusing to illustra

them as a component.The majority agreed thatthe modalities

componentwas notessentialto understand IPC;consensus was

established to remove it from the framework.

The main concern raised in the first two group sessions and i

the surveys had to do with the wording of certain components a

concepts.Almost30% of survey respondentsdisagreed with

the wording ofthe component‘‘objectivesaimed atby the

partnership’’and 6% disagreedwith the term ‘‘interaction

between members’’.Finally,the last group session led to a

consensus on terms that were deemed reflective of what happe

in clinical settingswhile being coherentwith the conceptual

knowledge aboutIPC (see the finalframework illustrated in

Figure 3).

Figure 2.Initial IPC framework.

4 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

ing, at one extreme, the least intense collaborative practice and, at

the other, the most intense. The ‘‘competencies’’ component was

left out of the framework because the diversity of the associated

concepts(e.g.communication,group dynamics,conflictreso-

lution)made itdifficultto illustrate them along a continuum.

Moreover,those particularconcepts could be betterillustrated

within an IPC competencies’ frameworks such as the Canadian

InterprofessionalHealthCollaborative(2010)[16]. Figure 2

presentsthe initial framework developed during phases1–6.

It includesfive components(e.g. ‘‘context’’,‘‘partnership’s

common objectives’’, ‘‘interaction between members’’, ‘‘integra-

tion of disciplinary knowledge’’,and ‘‘modalities’’)and their

associated concepts.The components are interlinked to define

four differenttypes of collaborative practices (illustrated by the

grey rectangles).For example,the mostintense collaborative

practice should be adopted when the client’sbiopsychosocial

needs are complex and demand a partnership to share decision-

making and adopt common intervention objectives. In this type of

practice,disciplinary knowledge needsto be more integrated

using an interdisciplinary approach.Differentmodalities can be

associatedwith this practice,but the interdisciplinaryteam

meeting is the mostoften used.Finally,the initialframework

incorporated the notion thatIPC can be considered as encom-

passing every activity of collaboration,including the least to the

mostintense practices,or can be associated with only the most

intense practice.

Framework formal validation

Twentypersonsparticipatedin one or anotherstep of the

validation process. Table 1 presents the experts’ and stakeholders’

profiles (current occupation and core training/discipline) for each

consensus group session and the survey.More than 82% of the

participantsconsidered they had good to excellentscientific

knowledge, and 76% good clinical experience, of IPC. More than

75% had completed post-graduate studies,and many ofthem

combined clinical and educational responsibilities in their curre

occupation.

From the outset,participantsappeared to agreewith the

framework’sgeneralpresentation.However,in the firstgroup

session, participants recommended adding a fifth type of pract

the independentpractice.They explained thateven when practi-

tionersdo notcollaborate atall with each other,partnerships

between clients and practitioners have to be established.In the

survey, when this independent practice was added to the four o

types of practices,100% of respondents agreed with the frame-

work’s generalpresentation.With regard to the components of

IPC, 12.5% of the surveyrespondentsdisagreedwith the

representation of the modalities.In the second consensus group

session,participants explained thatthe modalities differed from

one clinical setting to another, so it was too confusing to illustra

them as a component.The majority agreed thatthe modalities

componentwas notessentialto understand IPC;consensus was

established to remove it from the framework.

The main concern raised in the first two group sessions and i

the surveys had to do with the wording of certain components a

concepts.Almost30% of survey respondentsdisagreed with

the wording ofthe component‘‘objectivesaimed atby the

partnership’’and 6% disagreedwith the term ‘‘interaction

between members’’.Finally,the last group session led to a

consensus on terms that were deemed reflective of what happe

in clinical settingswhile being coherentwith the conceptual

knowledge aboutIPC (see the finalframework illustrated in

Figure 3).

Figure 2.Initial IPC framework.

4 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Anothermajorconcern was the theorization ofthe concept

‘‘interprofessionalcollaboration’’.In the survey,88.2% of

respondents said they were familiar with this term,butthey all

had differentdefinitionsof the concept.We observed in the

subsequentgroup sessions thatthe definitions used were clearly

influenced by the culture of the participant’s discipline and work

place. After discussing the different points of view and comparing

them to definitions found in the literature, participants agreed that

the common goal of practitioners getting involved in IPC was to

provide quality health and socialcare.To do this,practitioners

adopt different types of IPC, so that the intensity of the interaction

between clients,families and practitioners is adjusted depending

on the complexity of the situation.

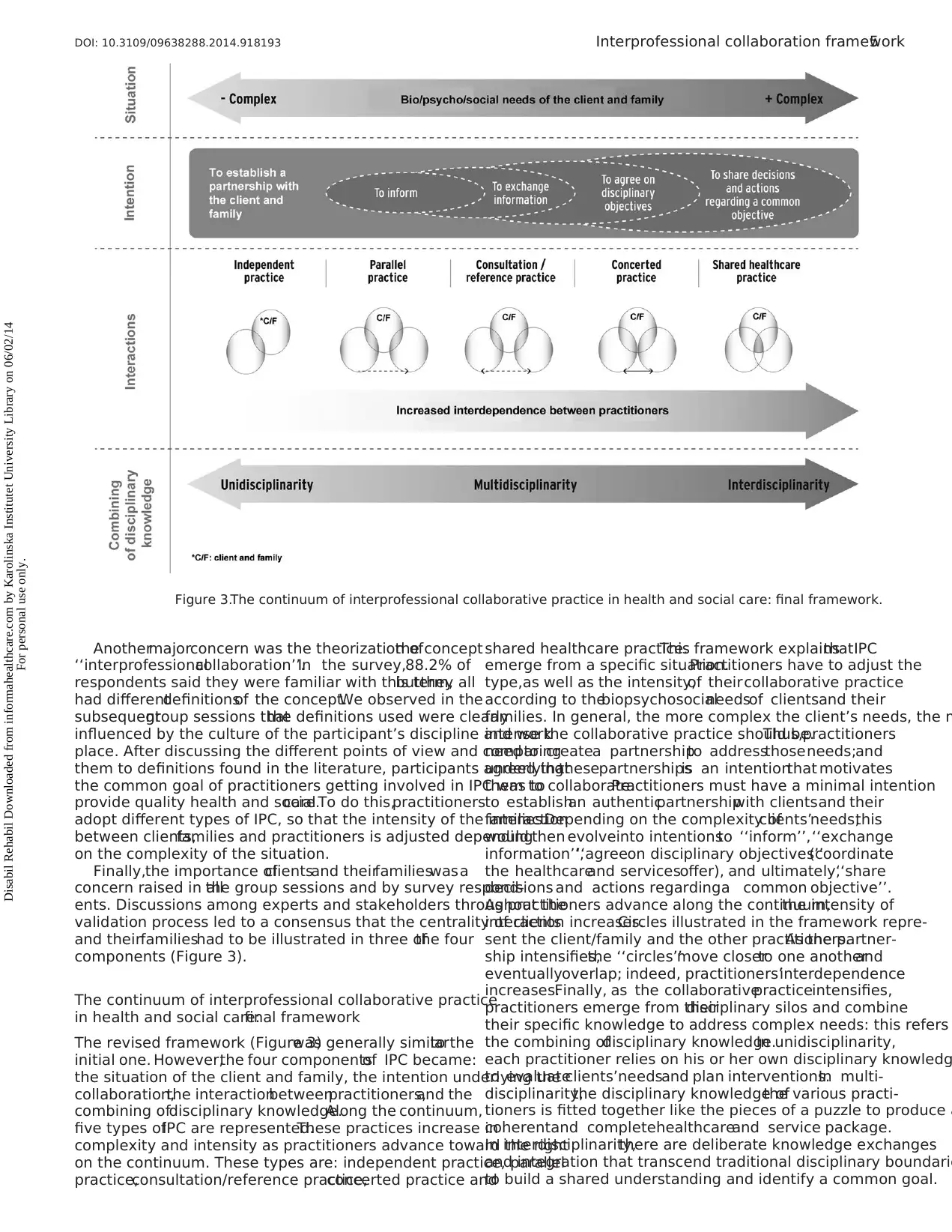

Finally,the importance ofclientsand theirfamilieswasa

concern raised in allthe group sessions and by survey respond-

ents. Discussions among experts and stakeholders throughout the

validation process led to a consensus that the centrality of clients

and theirfamilieshad to be illustrated in three ofthe four

components (Figure 3).

The continuum of interprofessional collaborative practice

in health and social care:final framework

The revised framework (Figure 3)was generally similarto the

initial one. However,the four componentsof IPC became:

the situation of the client and family, the intention underlying the

collaboration,the interactionbetweenpractitioners,and the

combining ofdisciplinary knowledge.Along the continuum,

five types ofIPC are represented.These practices increase in

complexity and intensity as practitioners advance toward the right

on the continuum. These types are: independent practice, parallel

practice,consultation/reference practice,concerted practice and

shared healthcare practice.This framework explainsthatIPC

emerge from a specific situation.Practitioners have to adjust the

type,as well as the intensity,of theircollaborative practice

according to thebiopsychosocialneedsof clientsand their

families. In general, the more complex the client’s needs, the m

intense the collaborative practice should be.Thus,practitioners

need to createa partnershipto addressthoseneeds;and

underlyingthesepartnershipsis an intentionthat motivates

them to collaborate.Practitioners must have a minimal intention

to establishan authenticpartnershipwith clientsand their

families.Depending on the complexity ofclients’needs,this

would then evolveinto intentionsto ‘‘inform’’,‘‘exchange

information’’,‘‘agreeon disciplinary objectives’’(coordinate

the healthcareand servicesoffer), and ultimately,‘‘share

decisions and actions regardinga common objective’’.

As practitioners advance along the continuum,the intensity of

interaction increases.Circles illustrated in the framework repre-

sent the client/family and the other practitioners.As the partner-

ship intensifies,the ‘‘circles’’move closerto one anotherand

eventuallyoverlap; indeed, practitioners’interdependence

increases.Finally, as the collaborativepracticeintensifies,

practitioners emerge from theirdisciplinary silos and combine

their specific knowledge to address complex needs: this refers

the combining ofdisciplinary knowledge.In unidisciplinarity,

each practitioner relies on his or her own disciplinary knowledg

to evaluateclients’needsand plan interventions.In multi-

disciplinarity,the disciplinary knowledge ofthe various practi-

tioners is fitted together like the pieces of a puzzle to produce a

coherentand completehealthcareand service package.

In interdisciplinarity,there are deliberate knowledge exchanges

and integration that transcend traditional disciplinary boundarie

to build a shared understanding and identify a common goal.

Figure 3.The continuum of interprofessional collaborative practice in health and social care: final framework.

DOI: 10.3109/09638288.2014.918193 Interprofessional collaboration framework5

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

‘‘interprofessionalcollaboration’’.In the survey,88.2% of

respondents said they were familiar with this term,butthey all

had differentdefinitionsof the concept.We observed in the

subsequentgroup sessions thatthe definitions used were clearly

influenced by the culture of the participant’s discipline and work

place. After discussing the different points of view and comparing

them to definitions found in the literature, participants agreed that

the common goal of practitioners getting involved in IPC was to

provide quality health and socialcare.To do this,practitioners

adopt different types of IPC, so that the intensity of the interaction

between clients,families and practitioners is adjusted depending

on the complexity of the situation.

Finally,the importance ofclientsand theirfamilieswasa

concern raised in allthe group sessions and by survey respond-

ents. Discussions among experts and stakeholders throughout the

validation process led to a consensus that the centrality of clients

and theirfamilieshad to be illustrated in three ofthe four

components (Figure 3).

The continuum of interprofessional collaborative practice

in health and social care:final framework

The revised framework (Figure 3)was generally similarto the

initial one. However,the four componentsof IPC became:

the situation of the client and family, the intention underlying the

collaboration,the interactionbetweenpractitioners,and the

combining ofdisciplinary knowledge.Along the continuum,

five types ofIPC are represented.These practices increase in

complexity and intensity as practitioners advance toward the right

on the continuum. These types are: independent practice, parallel

practice,consultation/reference practice,concerted practice and

shared healthcare practice.This framework explainsthatIPC

emerge from a specific situation.Practitioners have to adjust the

type,as well as the intensity,of theircollaborative practice

according to thebiopsychosocialneedsof clientsand their

families. In general, the more complex the client’s needs, the m

intense the collaborative practice should be.Thus,practitioners

need to createa partnershipto addressthoseneeds;and

underlyingthesepartnershipsis an intentionthat motivates

them to collaborate.Practitioners must have a minimal intention

to establishan authenticpartnershipwith clientsand their

families.Depending on the complexity ofclients’needs,this

would then evolveinto intentionsto ‘‘inform’’,‘‘exchange

information’’,‘‘agreeon disciplinary objectives’’(coordinate

the healthcareand servicesoffer), and ultimately,‘‘share

decisions and actions regardinga common objective’’.

As practitioners advance along the continuum,the intensity of

interaction increases.Circles illustrated in the framework repre-

sent the client/family and the other practitioners.As the partner-

ship intensifies,the ‘‘circles’’move closerto one anotherand

eventuallyoverlap; indeed, practitioners’interdependence

increases.Finally, as the collaborativepracticeintensifies,

practitioners emerge from theirdisciplinary silos and combine

their specific knowledge to address complex needs: this refers

the combining ofdisciplinary knowledge.In unidisciplinarity,

each practitioner relies on his or her own disciplinary knowledg

to evaluateclients’needsand plan interventions.In multi-

disciplinarity,the disciplinary knowledge ofthe various practi-

tioners is fitted together like the pieces of a puzzle to produce a

coherentand completehealthcareand service package.

In interdisciplinarity,there are deliberate knowledge exchanges

and integration that transcend traditional disciplinary boundarie

to build a shared understanding and identify a common goal.

Figure 3.The continuum of interprofessional collaborative practice in health and social care: final framework.

DOI: 10.3109/09638288.2014.918193 Interprofessional collaboration framework5

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

The Continuum ofInterprofessionalCollaborative Practice in

Health and Social Care illustrates non-hierarchical and non-linear

types of collaborative practices.For individuals engaged in IPC,

the challenge isto be able to move easily in both directions

along the continuum.They should be competentto adequately

evaluate the complexity of the situation in order to seek the right

intention forpartnership and adjustthe intensity of IPC so the

needs of clients and families can be effectively addressed.

Discussion

The Continuum ofInterprofessionalCollaborative Practice in

Health and SocialCare is a comprehensiveframework that

illustrates five types of collaborative practices according to four

descriptive components. It was developed and validated following

a seven-phaseprocedurethat includesliteraturereview and

consultation ofstakeholdersfrom the academicand clinical

settings.

One of the major innovationsof this frameworkis the

representation of the central position occupied by clients and their

families.In the framework,the primary and shared intention

behind every collaborative practice is to establish a partnership

with thesepersons.In the literature,all authorsagreethe

relationship with the person isimportant,but few affirm that

establishing this partnership should be the primary motivation to

collaborate.It is surprising that few researchers have conceptua-

lized clients and theirfamilies as true participants in IPC [3].

In our proposed framework,the primary role of clients and their

familiesis illustrated throughoutthe components.Indeed,the

purpose ofIPC is to address clients’needs (‘‘situation ofthe

client and family’’ component), and clients and their families are

considered truemembersof the team (‘‘interaction between

individuals’’ component).

The ‘‘intention underlying the collaboration’’componentis

also an important addition to the literature on IPC.In fact,most

authors agree the overall goal behind collaboration is to provide

quality health and socialcare to clients [2,17].Therefore,we

consider this overall goal is attained when IPC are appropriately

adjusted to the needs of clients and their families. The ‘‘intention

sought by collaboration’’ component in our framework allows us

to distinguish between the levels of partnership.D’Amour etal.

(2005) affirm that ‘‘it is unrealistic to think that simply bringing

practitionerstogetherin teamswill lead to collaboration’’

[3, p. 126].Practitionersneed to have a motivation to start

collaborating with each other.The ‘‘intention soughtby collab-

oration’’componentemphasizesthatIPC cannot be applied

following a recipe. In terms of collaboration, practitioners should

be able to adopta reflectivepracticeto adjusthow they

collaborate depending on the situation,the clienteleand the

clinical setting. In our opinion, the proposed framework highlights

this reality for the first time.

The framework also highlightsthe distinction between the

concepts of discipline, which refers to a body of knowledge, and

professional,which refers to a person with specific disciplinary

knowledge.Our frameworkreducesthe persistentconfusion

between these terms,while maintaining coherence with recent

published papers on the conceptualdefinition of IPC [2,18,19].

It emphasizes that the combining of disciplinary knowledge is not

the only component influencing IPC.

Finally,the validation processmade itpossible to adopta

consensual definition of the concept of IPC. As mentioned above,

although there is no consensualdefinition among the scientific

community,the term IPC is widely used by practitioners,

managers and decision-makers.The conceptualization proposed

in our framework iscoherentwith the concept’sattributes:a

cooperativeventurebasedon sharedpower and authority,

characterized by non-hierarchicalrelationships,establishmentof

a partnership,mutualgoalsand commitment[8]. It is also

consistentwith well-known IPC definitions thatpoints outthe

dynamic processwhose intensity isadjusted according to the

complexity of the client’s needs,and which is characterized by

interdependence,partnership,collegial relationships,shared

power,pursuitof common purpose,and person-centred practice

[17,18].

Relevance and usefulness of the framework

From the very firstgroup session,all stakeholders and experts

strongly believed in the relevance of developing a comprehens

IPC framework to enhance KT. Indeed, in the survey, 88% of the

respondents answered ‘‘highly relevant’’and 12% ‘‘quite rele-

vant’’.Respondentsalso believedthis frameworkwould be

‘‘very useful’’or ‘‘quite useful’’in variouscontextssuch as

(in order of usefulness) continuing education for health and soc

care practitioners,undergraduateIPE courses,research,and

continuing education for health and socialcare managers.This

framework provides managers and professionals with a clearer

conceptualization of IPC enabling them to better understand th

conceptof IPC and how the interactionalfactorsshould be

operationalized within different settings and with various client

It also highlights the importance of adopting a reflective practic

in order to suitably adjust the intensity of collaboration accordin

to the clients’ needs.Indeed,practitioners should notadoptthe

same functioning in every situation. They should be able to jud

if their interactionswith othersare optimalor not. This

framework could help them in their reasoning.Managers could

also use this frameworkto supportthe continuousquality

improvement process in their organization.

Limitations

It is importantto pointout thatthis initiative took place in a

French-Canadian context. Although the literature review includ

mostly papers published in English, the framework’s developme

and validation were conducted in French with French-speaking

individuals.Thus,it is possible that the meanings of some terms

from the literature were obscured ormodified in translation.

Moreover,the results reflect the perspectives of French-speaking

practitionerswithin thecontextof the Quebecrehabilitation

system. The framework was translated for this paper; it would b

importantto validatethe frameworkwith English-speaking

practitioners both in Quebec and in other geographic settings.

Conclusion

The Continuum ofInterprofessionalCollaborative Practice in

Health and Social Care integrates the current scientific knowled

and clinicalexperience regarding the conceptualization of IPC.

It is considered as a relevant and useful KT tool to enhance IPC

knowledge for various stakeholders,especially in the rehabilita-

tion field.This comprehensive and contextualized framework

could be used in undergraduateand continuingeducation

initiatives to help learners understand the multidimensionaland

dynamic nature of IPC.The framework could also be usefulto

supportpractitioners and managers in theirefforts to optimize

collaborativepracticewithin theirorganization.Even if this

framework was developed and validated within the rehabilitatio

field, it could probably be used to illustrate IPC interactional

factors that occur in other health and social care settings. Furth

research is nonetheless needed to validate the framework in ot

contexts.We also suggestbetter position this framework within

the otherconceptualmodels and frameworks thatexistin the

IPECP field.

6 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

Health and Social Care illustrates non-hierarchical and non-linear

types of collaborative practices.For individuals engaged in IPC,

the challenge isto be able to move easily in both directions

along the continuum.They should be competentto adequately

evaluate the complexity of the situation in order to seek the right

intention forpartnership and adjustthe intensity of IPC so the

needs of clients and families can be effectively addressed.

Discussion

The Continuum ofInterprofessionalCollaborative Practice in

Health and SocialCare is a comprehensiveframework that

illustrates five types of collaborative practices according to four

descriptive components. It was developed and validated following

a seven-phaseprocedurethat includesliteraturereview and

consultation ofstakeholdersfrom the academicand clinical

settings.

One of the major innovationsof this frameworkis the

representation of the central position occupied by clients and their

families.In the framework,the primary and shared intention

behind every collaborative practice is to establish a partnership

with thesepersons.In the literature,all authorsagreethe

relationship with the person isimportant,but few affirm that

establishing this partnership should be the primary motivation to

collaborate.It is surprising that few researchers have conceptua-

lized clients and theirfamilies as true participants in IPC [3].

In our proposed framework,the primary role of clients and their

familiesis illustrated throughoutthe components.Indeed,the

purpose ofIPC is to address clients’needs (‘‘situation ofthe

client and family’’ component), and clients and their families are

considered truemembersof the team (‘‘interaction between

individuals’’ component).

The ‘‘intention underlying the collaboration’’componentis

also an important addition to the literature on IPC.In fact,most

authors agree the overall goal behind collaboration is to provide

quality health and socialcare to clients [2,17].Therefore,we

consider this overall goal is attained when IPC are appropriately

adjusted to the needs of clients and their families. The ‘‘intention

sought by collaboration’’ component in our framework allows us

to distinguish between the levels of partnership.D’Amour etal.

(2005) affirm that ‘‘it is unrealistic to think that simply bringing

practitionerstogetherin teamswill lead to collaboration’’

[3, p. 126].Practitionersneed to have a motivation to start

collaborating with each other.The ‘‘intention soughtby collab-

oration’’componentemphasizesthatIPC cannot be applied

following a recipe. In terms of collaboration, practitioners should

be able to adopta reflectivepracticeto adjusthow they

collaborate depending on the situation,the clienteleand the

clinical setting. In our opinion, the proposed framework highlights

this reality for the first time.

The framework also highlightsthe distinction between the

concepts of discipline, which refers to a body of knowledge, and

professional,which refers to a person with specific disciplinary

knowledge.Our frameworkreducesthe persistentconfusion

between these terms,while maintaining coherence with recent

published papers on the conceptualdefinition of IPC [2,18,19].

It emphasizes that the combining of disciplinary knowledge is not

the only component influencing IPC.

Finally,the validation processmade itpossible to adopta

consensual definition of the concept of IPC. As mentioned above,

although there is no consensualdefinition among the scientific

community,the term IPC is widely used by practitioners,

managers and decision-makers.The conceptualization proposed

in our framework iscoherentwith the concept’sattributes:a

cooperativeventurebasedon sharedpower and authority,

characterized by non-hierarchicalrelationships,establishmentof

a partnership,mutualgoalsand commitment[8]. It is also

consistentwith well-known IPC definitions thatpoints outthe

dynamic processwhose intensity isadjusted according to the

complexity of the client’s needs,and which is characterized by

interdependence,partnership,collegial relationships,shared

power,pursuitof common purpose,and person-centred practice

[17,18].

Relevance and usefulness of the framework

From the very firstgroup session,all stakeholders and experts

strongly believed in the relevance of developing a comprehens

IPC framework to enhance KT. Indeed, in the survey, 88% of the

respondents answered ‘‘highly relevant’’and 12% ‘‘quite rele-

vant’’.Respondentsalso believedthis frameworkwould be

‘‘very useful’’or ‘‘quite useful’’in variouscontextssuch as

(in order of usefulness) continuing education for health and soc

care practitioners,undergraduateIPE courses,research,and

continuing education for health and socialcare managers.This

framework provides managers and professionals with a clearer

conceptualization of IPC enabling them to better understand th

conceptof IPC and how the interactionalfactorsshould be

operationalized within different settings and with various client

It also highlights the importance of adopting a reflective practic

in order to suitably adjust the intensity of collaboration accordin

to the clients’ needs.Indeed,practitioners should notadoptthe

same functioning in every situation. They should be able to jud

if their interactionswith othersare optimalor not. This

framework could help them in their reasoning.Managers could

also use this frameworkto supportthe continuousquality

improvement process in their organization.

Limitations

It is importantto pointout thatthis initiative took place in a

French-Canadian context. Although the literature review includ

mostly papers published in English, the framework’s developme

and validation were conducted in French with French-speaking

individuals.Thus,it is possible that the meanings of some terms

from the literature were obscured ormodified in translation.

Moreover,the results reflect the perspectives of French-speaking

practitionerswithin thecontextof the Quebecrehabilitation

system. The framework was translated for this paper; it would b

importantto validatethe frameworkwith English-speaking

practitioners both in Quebec and in other geographic settings.

Conclusion

The Continuum ofInterprofessionalCollaborative Practice in

Health and Social Care integrates the current scientific knowled

and clinicalexperience regarding the conceptualization of IPC.

It is considered as a relevant and useful KT tool to enhance IPC

knowledge for various stakeholders,especially in the rehabilita-

tion field.This comprehensive and contextualized framework

could be used in undergraduateand continuingeducation

initiatives to help learners understand the multidimensionaland

dynamic nature of IPC.The framework could also be usefulto

supportpractitioners and managers in theirefforts to optimize

collaborativepracticewithin theirorganization.Even if this

framework was developed and validated within the rehabilitatio

field, it could probably be used to illustrate IPC interactional

factors that occur in other health and social care settings. Furth

research is nonetheless needed to validate the framework in ot

contexts.We also suggestbetter position this framework within

the otherconceptualmodels and frameworks thatexistin the

IPECP field.

6 E. Careau et al. Disabil Rehabil,Early Online: 1–7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Jean Maziade and Line Pare´ for their contributions

to the framework’s developmentand to allthe stakeholders for

their participation.We wish to thank the Collaborative Network

for Interprofessional Practices in Health and Social Care (RCPI)

for its support and funding.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declaration of interest. This study was funded

by the Re´seau de collaboration sur les pratiques interprofession-

nelles (RCPI)and the Canadian Institutesof Health Research

(CIHR). E. Careau held a Canadian Institutes of Health Research

scholarship at the time of this work.

References

1. World Health Organization.Framework foraction on interprofes-

sional education & collaborative practice.Geneva: WHO; 2010.

2. ReevesS, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M.Interprofessional

teamwork forhealth and socialcare.Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell;

2011.

3. D’Amour D,Ferrada-Videla M,San Martin Rodriguez L,Beaulieu

M-D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core

conceptsand theoreticalframeworks.J InterprofCare 2005;19:

116–31.

4. D’Amour D, Goulet L, Labadie J-F, et al. A model and typology of

collaboration between professionalsin healthcareorganizations.

BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:1–14.

5. Zwarenstein M,Goldman J,Reeves S.Interprofessionalcollabor-

ation: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice

and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;8:1–33.

6. Rodgers BL. Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Rodgers L,

Knafl KA, eds. Conceptdevelopmentin nursing: foundations,

techniques,and applications,2nd ed.Philadelphia (PA):Saunders;

2000:77–102.

7. Petri L. Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration. Nursing

Forum 2010;45:73–82.

8. Xyrichis A,Ream E.Teamwork:a conceptanalysis.J Adv Nurs

2008;61:232–41.

9. Henneman EA, Lee JL, Cohen Jl. Collaboration: a concept analysis.

J Adv Nurs 1995;21:103–9.

10. Leathard A.Introduction.In: Leathard A,ed. Interprofessional

collaboration:from policy to practice in health and socialcare.

New York (NY): Brunner-Routledge; 2003:3–11.

11. Ivey SL,Brown LS,Teske Y,Silverman D.A modelfor teaching

aboutinterdisciplinary practice in health care settings.J Allied

Health 1988;17:189–95.

12. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. More about

knowledge translation at CIHR; 2013. Available from:

http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/39033.html[last accessed20 Jan

2013].

13. Graham ID,Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge

translation:time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof2006;26:

13–24.

14. JabareenY. Building a conceptualframework:philosophy,

definitions,and procedure.Int J Qual Methods 2009;8:49–62.

15. Canadian InterprofessionalHealth Collaborative.A nationalinter-

professionalcompetencyframework. Vancouver: Canadian

Interprofessional Health Collaborative; 2010.

16. Careau E. Processus de collaboration interprofessionnelle en sante´ et

servicessociaux:Propositiond’une grille d’observationpour

l’e´valuation desrencontresd’e´quipe interdisciplinaires(disserta-

tion).Que´bec: Universite´ Laval; 2013.297 p.

17. Oandasan I, Ross Baker G, Barker K, et al. Teamwork in healthcare:

promoting effectiveteamwork in healthcarein Canada.Policy

synthesis and recommendations. Ottawa (Ontario): Canadian Healt

Services Research Foundation; 2005.

18. D’Amour D, OandasanI. Interprofessionalityas the field of

interprofessionalpracticeand interprofessionaleducation:an

emerging concept.J Interprof Care 2005;19:8–20.

19. Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education

part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interpro

Care 2005;19:8–20.

DOI: 10.3109/09638288.2014.918193 Interprofessional collaboration framework7

Disabil Rehabil Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Karolinska Institutet University Library on 06/02/14

For personal use only.

Thanks to Dr. Jean Maziade and Line Pare´ for their contributions

to the framework’s developmentand to allthe stakeholders for

their participation.We wish to thank the Collaborative Network

for Interprofessional Practices in Health and Social Care (RCPI)

for its support and funding.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declaration of interest. This study was funded

by the Re´seau de collaboration sur les pratiques interprofession-

nelles (RCPI)and the Canadian Institutesof Health Research

(CIHR). E. Careau held a Canadian Institutes of Health Research

scholarship at the time of this work.

References

1. World Health Organization.Framework foraction on interprofes-

sional education & collaborative practice.Geneva: WHO; 2010.

2. ReevesS, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M.Interprofessional

teamwork forhealth and socialcare.Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell;

2011.

3. D’Amour D,Ferrada-Videla M,San Martin Rodriguez L,Beaulieu

M-D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core

conceptsand theoreticalframeworks.J InterprofCare 2005;19:

116–31.

4. D’Amour D, Goulet L, Labadie J-F, et al. A model and typology of

collaboration between professionalsin healthcareorganizations.

BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:1–14.

5. Zwarenstein M,Goldman J,Reeves S.Interprofessionalcollabor-

ation: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice

and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;8:1–33.

6. Rodgers BL. Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Rodgers L,

Knafl KA, eds. Conceptdevelopmentin nursing: foundations,

techniques,and applications,2nd ed.Philadelphia (PA):Saunders;

2000:77–102.

7. Petri L. Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration. Nursing

Forum 2010;45:73–82.

8. Xyrichis A,Ream E.Teamwork:a conceptanalysis.J Adv Nurs

2008;61:232–41.

9. Henneman EA, Lee JL, Cohen Jl. Collaboration: a concept analysis.

J Adv Nurs 1995;21:103–9.

10. Leathard A.Introduction.In: Leathard A,ed. Interprofessional

collaboration:from policy to practice in health and socialcare.

New York (NY): Brunner-Routledge; 2003:3–11.

11. Ivey SL,Brown LS,Teske Y,Silverman D.A modelfor teaching

aboutinterdisciplinary practice in health care settings.J Allied

Health 1988;17:189–95.

12. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. More about

knowledge translation at CIHR; 2013. Available from:

http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/39033.html[last accessed20 Jan

2013].

13. Graham ID,Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge