Intra-Professional Dynamics in Translational Health Research

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|8

|9631

|411

Report

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the intra-professional dynamics within translational health research, specifically focusing on the interactions between health services researchers and organization scientists. It uses the context of Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in England to highlight the contestation within social science, where health services researchers seek to elevate their position by emphasizing the practical impact of their research compared to the theory-oriented approach of organization scientists. The study explores how these dynamics influence resource allocation and professional standing within the translational health research domain, addressing the need for understanding how different scientific communities perceive and judge one another. The research questions address the basis of interaction between health services researchers and organization scientists, and how better interactions can be supported to improve disciplinary collaboration.

Intra-professional dynamics in translational health research:

The perspective of social scientists

Graeme Currie*

, Nellie El Enany,Andy Lockett

Warwick Business School,The University of Warwick,Coventry CV4 7AL,United Kingdom

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 May 2013

Received in revised form

18 April 2014

Accepted 27 May 2014

Available online 27 May 2014

Keywords:

Translational health research

Epistemic communities

Social scientists

Professional dynamics

CLAHRC

England

a b s t r a c t

In contrast to previous studies,which focus upon the professionaldynamics of translationalhealth

research between clinician scientists and socialscientists (inter-professionalcontestation),we focus

upon contestation within social science (intra-professionalcontestation).Drawing on the empirical

context of Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in England,we

highlight that although social scientists accept subordination to clinician scientists,health services re-

searchers attempt to enhance their position in translationalhealth research vis-a-vis organisation sci-

entists,whom they perceive as relative newcomers to the research domain.Health services researchers

do so through privileging the practicalimpact of their research,compared to organisation scientists'

orientation towards development of theory,which health services researchers argue is decoupled from

any concern with healthcare improvement.The concern of health services researchers lies with main-

taining existing patterns of resource allocation to support their research endeavours,working alongside

clinician scientists,in translationalhealth research.The response of organisation scientists is one that

might be considered ambivalent,since,unlike health services researchers, they do not rely upon a close

relationship with clinician scientists to carry out research,or more generally,garner resource.

© 2014 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In this paper we draw on the sociology of professions literature

(Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984) to explore the extent to which it is

possible for different epistemic communities within social science

to integrate into,and thrive in the domain of,translational health

research,within which the experimental paradigm occupiesa

hegemonic position.Extant studies have focused on interactions

across epistemic communities ofclinician scientists and social

scientists in translational health research (Albert et al., 2008; Albert

et al.,2009; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).In contrast,we

view the challenge of translational health research from the

perspective of social scientists, a neglected focus of empirical study

(Albert et al.,2008; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).Further,

we treat social scientists as a variegated,epistemic community

(Becher and Trowler,2001), and disaggregate those involved in

translational health research into two distinct epistemic commu-

nities: health services researchersand organisation scientists.

Finally,rather than focussing on the interaction between clinician

scientists and socialscientists (inter-professionaldynamics),we

focus upon interaction between health services researchers and

organisation scientists (intra-professionaldynamics).In so doing,

we adopt a relational perspective across and within epistemic

communities,which enables us to explore the discordance be-

tween social scientists involved in translationalhealth research

about the value of others'research (Albert et al.,2009).

In exploring the discordance between social scientists in

translationalresearch we address the callfor research to under-

stand how different epistemic scientific communities perceive and

judge one another,through consideration of the professionaldy-

namics of the translational health research domain (Albert et al.,

2008,2009; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).As Albert et al.

(2009: 174) state: “in the current move towards inter-disciplinary

research,it is vital to understand how scientists from different

backgrounds and with different degrees of scientific authority

perceive and judge one another”,since this shapes not only their

attitudes towards collaboration,but has material resource conse-

quences.In particular,researchers are asked to consider how sci-

entific epistemic communities attempt to establish a distinct field

of expertise,maintain professional jurisdiction,and consolidate or

enhance status and collective standing as leaders of translational

health research (Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Graeme.currie@wbs.ac.uk (G.Currie).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Social Science & Medicine

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / s o c s c i m e d

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.045

0277-9536/© 2014 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88

The perspective of social scientists

Graeme Currie*

, Nellie El Enany,Andy Lockett

Warwick Business School,The University of Warwick,Coventry CV4 7AL,United Kingdom

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 May 2013

Received in revised form

18 April 2014

Accepted 27 May 2014

Available online 27 May 2014

Keywords:

Translational health research

Epistemic communities

Social scientists

Professional dynamics

CLAHRC

England

a b s t r a c t

In contrast to previous studies,which focus upon the professionaldynamics of translationalhealth

research between clinician scientists and socialscientists (inter-professionalcontestation),we focus

upon contestation within social science (intra-professionalcontestation).Drawing on the empirical

context of Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in England,we

highlight that although social scientists accept subordination to clinician scientists,health services re-

searchers attempt to enhance their position in translationalhealth research vis-a-vis organisation sci-

entists,whom they perceive as relative newcomers to the research domain.Health services researchers

do so through privileging the practicalimpact of their research,compared to organisation scientists'

orientation towards development of theory,which health services researchers argue is decoupled from

any concern with healthcare improvement.The concern of health services researchers lies with main-

taining existing patterns of resource allocation to support their research endeavours,working alongside

clinician scientists,in translationalhealth research.The response of organisation scientists is one that

might be considered ambivalent,since,unlike health services researchers, they do not rely upon a close

relationship with clinician scientists to carry out research,or more generally,garner resource.

© 2014 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In this paper we draw on the sociology of professions literature

(Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984) to explore the extent to which it is

possible for different epistemic communities within social science

to integrate into,and thrive in the domain of,translational health

research,within which the experimental paradigm occupiesa

hegemonic position.Extant studies have focused on interactions

across epistemic communities ofclinician scientists and social

scientists in translational health research (Albert et al., 2008; Albert

et al.,2009; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).In contrast,we

view the challenge of translational health research from the

perspective of social scientists, a neglected focus of empirical study

(Albert et al.,2008; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).Further,

we treat social scientists as a variegated,epistemic community

(Becher and Trowler,2001), and disaggregate those involved in

translational health research into two distinct epistemic commu-

nities: health services researchersand organisation scientists.

Finally,rather than focussing on the interaction between clinician

scientists and socialscientists (inter-professionaldynamics),we

focus upon interaction between health services researchers and

organisation scientists (intra-professionaldynamics).In so doing,

we adopt a relational perspective across and within epistemic

communities,which enables us to explore the discordance be-

tween social scientists involved in translationalhealth research

about the value of others'research (Albert et al.,2009).

In exploring the discordance between social scientists in

translationalresearch we address the callfor research to under-

stand how different epistemic scientific communities perceive and

judge one another,through consideration of the professionaldy-

namics of the translational health research domain (Albert et al.,

2008,2009; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).As Albert et al.

(2009: 174) state: “in the current move towards inter-disciplinary

research,it is vital to understand how scientists from different

backgrounds and with different degrees of scientific authority

perceive and judge one another”,since this shapes not only their

attitudes towards collaboration,but has material resource conse-

quences.In particular,researchers are asked to consider how sci-

entific epistemic communities attempt to establish a distinct field

of expertise,maintain professional jurisdiction,and consolidate or

enhance status and collective standing as leaders of translational

health research (Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012).

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Graeme.currie@wbs.ac.uk (G.Currie).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Social Science & Medicine

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / s o c s c i m e d

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.045

0277-9536/© 2014 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In the remainder of the paper,and based on the above,we

address the following research questions: (i) on what basis,and

with what effect,do health services researchers and organisation

scientists interact (or not) in translational health research? And, (ii)

assuming policymakers are justified in their investment in trans-

lational health research, embedded within which disciplinary

collaboration is necessary,how might better interactions between

health services researchers and organisation scientists be

supported?

2. Conceptual framework

Our study conceives disciplinary and scientific practices as social

institutions (Albert et al., 2009), which are manifested as ‘epistemic

communities’ (Knorr-Cetina, 1999) or ‘academic tribes’ (Becher and

Trowler, 2001). Epistemic communities constitute, “taken-for-

granted ways of thinking about and doing science; e.g.shared as-

sumptions about what ‘good’ science is,what method is best to

generate valid results,how data should be collected and inter-

preted, and what constitutes productive science” (Albertet al.,

2009: 173).

In considering the interaction of epistemic communities within

translationalhealth research,scholars have highlighted that the

experimentalmethod is privileged (Albert et al., 2008, 2009;

Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012),which positions biomed-

ical scientists and clinician scientists at the top of the hierarchy of

epistemic communities involved in translationalhealth research.

The process through which hierarchy is derived is one whereby

certain procedural assessment criteria are applied to evaluate the

science of an epistemic community.Albert et al. (2008, 2009)

describe how the interaction of biomedicalor clinician scientists

and socialscientists is framed by epistemic culture and position

(dominant or subordinate),and differential power to set out what

constituteslegitimate science.The current dominant scientific

criteria in translational health research are primarily atheoretical,

quantitative and hypothesis-driven, whereas social science is more

theoretical,qualitative and interpretive (Albert et al.,2008).The

effect of proceduralassessment criteria about value of science is

one that privileges the epistemic community of clinician scientists,

and renders subordinate the epistemic community ofsocial sci-

entists.Thus,Albert et al.(2008,2009) anticipate that the growth

of social sciences will continue to meet obstacles, derived from the

dominant position of the episteme of biomedicaland clinician

scientists,within the health research field.Reflecting the pessi-

mism of Albert et al.(2008,2009),other academic commentators

report that current attempts to integrate social scientists into the

translational health research domain are encountering significant

difficulties and resistance from clinician scientists (Bernier,2005;

De Villiers, 2005; Grol, 1997; Kislov et al., 2011; Rowley et al.,

2012).

The aforementioned studies focus upon interactions between

biomedical or clinician scientists and social scientists (a matter of

inter-disciplinary contestation),but treat social science as a

monolithic epistemic community.We suggest,however,that in-

teractions within the epistemic community of social scientists are

likely to be rather more dynamic than recognised in extant litera-

ture. In recognition of a gap within social science,as applied to

healthcare,Currie et al.(2012) edited a collection of studies pro-

duced by organisation scientists to draw to the attention of medical

sociologists and health policy academics the value of their work. In

reflecting upon why such integration ofepistemic communities

within social science has been slow to realise,we suggestthat

attention should be focused on the procedural assessment criteria

in framing the intra-disciplinary relations between organisation

scientists and health services researchers in translationalhealth

research.We suggest that the sociology ofprofessions literature

might provide insight into this issue.

The sociology of professions literature suggests thatthe dy-

namics of professional organisation relate to stratification and hi-

erarchy designed to protect or extend jurisdiction through expert

claims about exclusivity of knowledge, in a way that simultaneously

enhances professional status (Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984). Those

in privileged positions in the professional hierarchy (in the case of

translational health research,clinician scientists),may accommo-

date substitution of their labour where they are not competing for

resource. Simply stated, abundance or scarcity of resource is likely

to shape professional dynamics. Competition for resource has been

noted as a significant issue in contestation between scientific

epistemic communities in translationalhealth research (Albert

et al.,2008,2009).The incentive for social scientists to engage in

translationalhealth research is to gain higher status in the field,

exert more influence on health policy,and perhaps most impor-

tantly,to access more resources (Albert et al.,2008).Even where

resource constraints are less significant,however,powerful pro-

fessions may seek to controlthat labour with which it has been

substituted; i.e.a delegation tactic,which renders the substitute

labour subordinate to the powerful profession (Martin et al., 2009).

Thus, perhaps unsurprisingly,when engaging in translational

health research,social scientists are positioned as subordinate to

clinician scientists,meaning that they only have access to limited

financial resource (Albert et al.,2008,2009).How such processes

play out between organisation scientists and health services re-

searchers within the socialscience epistemic community is not

clear,but similar dynamics around knowledge claims and stratifi-

cation are likely to be evident.

3. Data and method

3.1.The empirical case

Our empirical case is CLAHRC,a translationalresearch inter-

vention in the English National Health Service (NHS) (Dzau et al.,

2010),which is one of many such translationalhealth research

interventions evident globally.For example,in the United States,

Veterans'Health Administration's Integrated Health and Research

System (Graham and Tetroe,2009), American Quality Enhance-

ment Research Initiative (www.queri.research.va.gov), and Clinical

Translational Science Centres (Butler,2008); in Canada,the Cana-

dian Health Services Research Foundation (Dussault et al.,2007);

and in the Netherlands,the Dutch Academic Collaborative Centres

for Public Health (Wehrens et al.,2012).

Nine pilot CLAHRCs were established in 2008,funded £100

million by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) forfive

years, with a similar amount of matched funding from participating

universities and healthcare organisations. Recently, further funding

of £120million,again with a similar amount of matched funding

from participating universities and healthcare organisations,was

awarded for 13 CLAHRCs, encompassing continuation of funding for

the earlier pilots,for a further five years from 2014.

The intention of the CLAHRC initiative was promote trans-

lational research to move beyond linear models of translating ac-

ademic evidence into practice (Nutley et al., 2007). In doing so the

nine CLAHRCs were tasked with three key interlocking functions:

(i) conducting high quality applied health research;(ii) imple-

menting the findings from research in clinicalpractice; and (iii)

increasing the capacity of NHS organisations to engage with and

apply research. The nine CLAHRCs are regionally focused, with their

agendas being determined by the partnering organisations and

tailored to healthcare needs in their respective geographical areas.

Whilst mandated by policy, CLAHRCs were regarded by the NIHR as

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e8882

address the following research questions: (i) on what basis,and

with what effect,do health services researchers and organisation

scientists interact (or not) in translational health research? And, (ii)

assuming policymakers are justified in their investment in trans-

lational health research, embedded within which disciplinary

collaboration is necessary,how might better interactions between

health services researchers and organisation scientists be

supported?

2. Conceptual framework

Our study conceives disciplinary and scientific practices as social

institutions (Albert et al., 2009), which are manifested as ‘epistemic

communities’ (Knorr-Cetina, 1999) or ‘academic tribes’ (Becher and

Trowler, 2001). Epistemic communities constitute, “taken-for-

granted ways of thinking about and doing science; e.g.shared as-

sumptions about what ‘good’ science is,what method is best to

generate valid results,how data should be collected and inter-

preted, and what constitutes productive science” (Albertet al.,

2009: 173).

In considering the interaction of epistemic communities within

translationalhealth research,scholars have highlighted that the

experimentalmethod is privileged (Albert et al., 2008, 2009;

Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller,2012),which positions biomed-

ical scientists and clinician scientists at the top of the hierarchy of

epistemic communities involved in translationalhealth research.

The process through which hierarchy is derived is one whereby

certain procedural assessment criteria are applied to evaluate the

science of an epistemic community.Albert et al. (2008, 2009)

describe how the interaction of biomedicalor clinician scientists

and socialscientists is framed by epistemic culture and position

(dominant or subordinate),and differential power to set out what

constituteslegitimate science.The current dominant scientific

criteria in translational health research are primarily atheoretical,

quantitative and hypothesis-driven, whereas social science is more

theoretical,qualitative and interpretive (Albert et al.,2008).The

effect of proceduralassessment criteria about value of science is

one that privileges the epistemic community of clinician scientists,

and renders subordinate the epistemic community ofsocial sci-

entists.Thus,Albert et al.(2008,2009) anticipate that the growth

of social sciences will continue to meet obstacles, derived from the

dominant position of the episteme of biomedicaland clinician

scientists,within the health research field.Reflecting the pessi-

mism of Albert et al.(2008,2009),other academic commentators

report that current attempts to integrate social scientists into the

translational health research domain are encountering significant

difficulties and resistance from clinician scientists (Bernier,2005;

De Villiers, 2005; Grol, 1997; Kislov et al., 2011; Rowley et al.,

2012).

The aforementioned studies focus upon interactions between

biomedical or clinician scientists and social scientists (a matter of

inter-disciplinary contestation),but treat social science as a

monolithic epistemic community.We suggest,however,that in-

teractions within the epistemic community of social scientists are

likely to be rather more dynamic than recognised in extant litera-

ture. In recognition of a gap within social science,as applied to

healthcare,Currie et al.(2012) edited a collection of studies pro-

duced by organisation scientists to draw to the attention of medical

sociologists and health policy academics the value of their work. In

reflecting upon why such integration ofepistemic communities

within social science has been slow to realise,we suggestthat

attention should be focused on the procedural assessment criteria

in framing the intra-disciplinary relations between organisation

scientists and health services researchers in translationalhealth

research.We suggest that the sociology ofprofessions literature

might provide insight into this issue.

The sociology of professions literature suggests thatthe dy-

namics of professional organisation relate to stratification and hi-

erarchy designed to protect or extend jurisdiction through expert

claims about exclusivity of knowledge, in a way that simultaneously

enhances professional status (Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984). Those

in privileged positions in the professional hierarchy (in the case of

translational health research,clinician scientists),may accommo-

date substitution of their labour where they are not competing for

resource. Simply stated, abundance or scarcity of resource is likely

to shape professional dynamics. Competition for resource has been

noted as a significant issue in contestation between scientific

epistemic communities in translationalhealth research (Albert

et al.,2008,2009).The incentive for social scientists to engage in

translationalhealth research is to gain higher status in the field,

exert more influence on health policy,and perhaps most impor-

tantly,to access more resources (Albert et al.,2008).Even where

resource constraints are less significant,however,powerful pro-

fessions may seek to controlthat labour with which it has been

substituted; i.e.a delegation tactic,which renders the substitute

labour subordinate to the powerful profession (Martin et al., 2009).

Thus, perhaps unsurprisingly,when engaging in translational

health research,social scientists are positioned as subordinate to

clinician scientists,meaning that they only have access to limited

financial resource (Albert et al.,2008,2009).How such processes

play out between organisation scientists and health services re-

searchers within the socialscience epistemic community is not

clear,but similar dynamics around knowledge claims and stratifi-

cation are likely to be evident.

3. Data and method

3.1.The empirical case

Our empirical case is CLAHRC,a translationalresearch inter-

vention in the English National Health Service (NHS) (Dzau et al.,

2010),which is one of many such translationalhealth research

interventions evident globally.For example,in the United States,

Veterans'Health Administration's Integrated Health and Research

System (Graham and Tetroe,2009), American Quality Enhance-

ment Research Initiative (www.queri.research.va.gov), and Clinical

Translational Science Centres (Butler,2008); in Canada,the Cana-

dian Health Services Research Foundation (Dussault et al.,2007);

and in the Netherlands,the Dutch Academic Collaborative Centres

for Public Health (Wehrens et al.,2012).

Nine pilot CLAHRCs were established in 2008,funded £100

million by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) forfive

years, with a similar amount of matched funding from participating

universities and healthcare organisations. Recently, further funding

of £120million,again with a similar amount of matched funding

from participating universities and healthcare organisations,was

awarded for 13 CLAHRCs, encompassing continuation of funding for

the earlier pilots,for a further five years from 2014.

The intention of the CLAHRC initiative was promote trans-

lational research to move beyond linear models of translating ac-

ademic evidence into practice (Nutley et al., 2007). In doing so the

nine CLAHRCs were tasked with three key interlocking functions:

(i) conducting high quality applied health research;(ii) imple-

menting the findings from research in clinicalpractice; and (iii)

increasing the capacity of NHS organisations to engage with and

apply research. The nine CLAHRCs are regionally focused, with their

agendas being determined by the partnering organisations and

tailored to healthcare needs in their respective geographical areas.

Whilst mandated by policy, CLAHRCs were regarded by the NIHR as

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e8882

experimentalin nature during their inception,with considerable

variation allowed for their structures and processes. Social sciences

were variably integrated into CLAHRC plans,with some involving

input from health services researchers located in or near to medical

schools,and others involving input from organisation scientists in

business schools;academic research and clinicalpractice were

blended in different ways; and there were differences in the disease

emphasis ofCLAHRCs,although all nine CLAHRCs focused upon

translational health research around long-term conditions.

Regarding the constituent epistemic communities upon whom

we focus within CLAHRC,we asked our respondents to self-define

themselvesas clinician scientists,1 health services researchers,

organisation scientists,NHS managers,and clinical practitioners.

We corroborated their self-definitions with our own assessment of

which epistemic community towards which they orientate (in all

cases,we agreed with the self-definition). We recognise,however,

that our categorisation is rather crude,and operates as a heuristic

device to aid theoretical analysis. Some academics, as discussed in

our empirical presentation,are not easily categorised and present

themselves as ‘hybrid’academics thatcross the boundaries of

epistemic communities.

Regarding the authors'own position, we are located in the

category oforganisation scientists,located in a business school

(although at least one of us might characterise himself/herself as

‘hybrid').We remained reflexive in our analysis to mediate any

partiality in analysis; e.g.analysis was presented to CLAHRC Di-

rectors (clinician scientists), other audiences where health services

researchers and clinician scientists were present. In support of our

impartial stance,we highlight analysis within the manuscript is

somewhat critical of our own community; e.g. as theoretically

driven with little concern for practical impact, as just chasing

research funding wherever its source and focus.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

We employed a longitudinal research strategy over a period of

three years to analyse interactions between constituent epistemic

communities of CLAHRC.Ethics approvalwas sought and gained

prior to commencing research (Research Ethics Committee refer-

ence: 10/H0402/6 Leicestershire,Northamptonshire and Rutland

Research Ethics Committee 2).CLAHRC Data presented in this

article is mainly drawn from 174 qualitative interviews carried out

between 2009 and 2012,encompassing a first,exploratory phase

across all 9 CLAHRCs (104 interviews), followed by a second phase

of data collection across four in-depth comparative cases (Cases B,

C, D, G: 70 interviews). Details of the interviewees are presented in

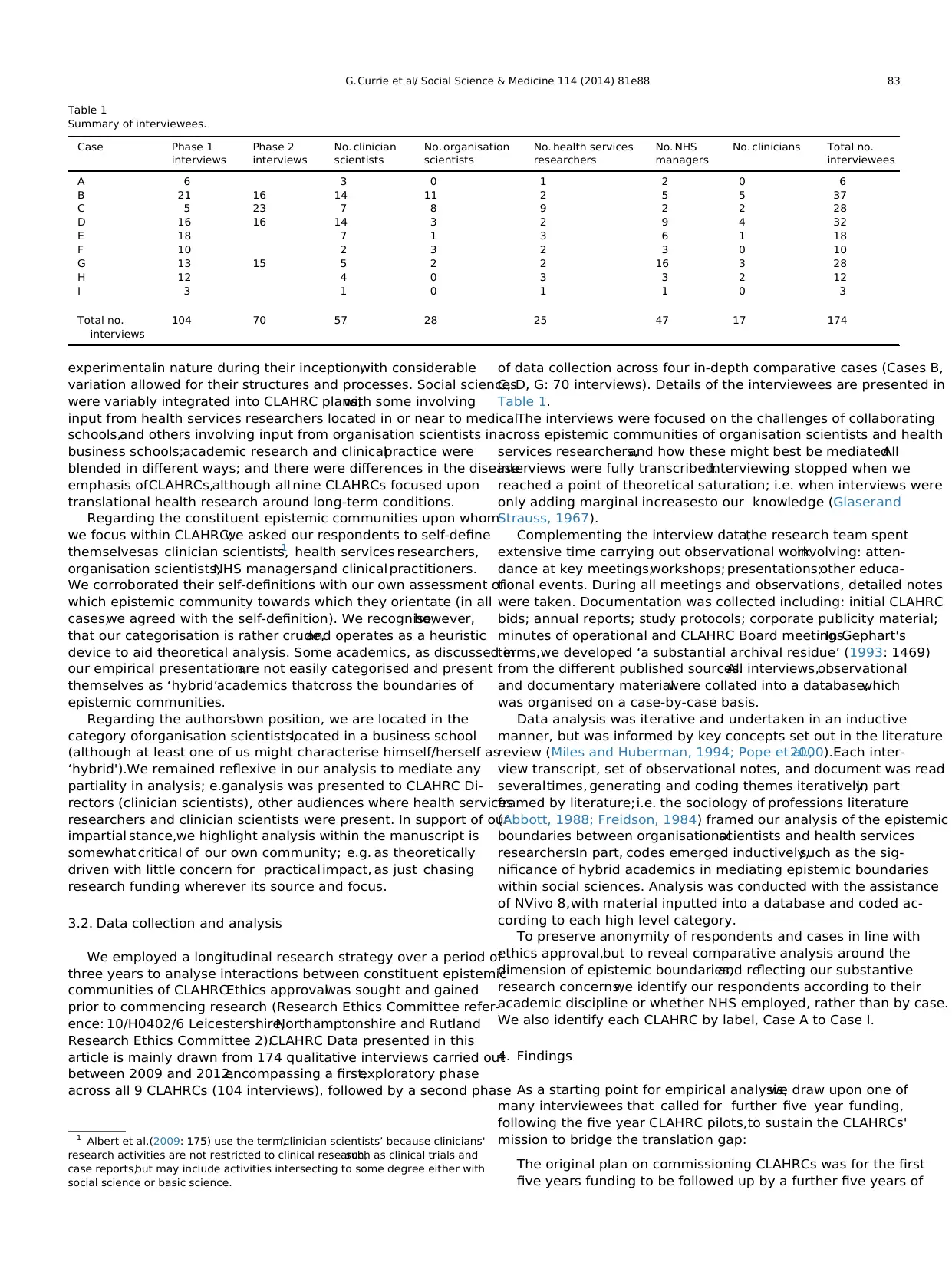

Table 1.

The interviews were focused on the challenges of collaborating

across epistemic communities of organisation scientists and health

services researchers,and how these might best be mediated.All

interviews were fully transcribed.Interviewing stopped when we

reached a point of theoretical saturation; i.e. when interviews were

only adding marginal increasesto our knowledge (Glaserand

Strauss, 1967).

Complementing the interview data,the research team spent

extensive time carrying out observational work,involving: atten-

dance at key meetings;workshops; presentations;other educa-

tional events. During all meetings and observations, detailed notes

were taken. Documentation was collected including: initial CLAHRC

bids; annual reports; study protocols; corporate publicity material;

minutes of operational and CLAHRC Board meetings.In Gephart's

terms,we developed ‘a substantial archival residue’ (1993: 1469)

from the different published sources.All interviews,observational

and documentary materialwere collated into a database,which

was organised on a case-by-case basis.

Data analysis was iterative and undertaken in an inductive

manner, but was informed by key concepts set out in the literature

review (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Pope et al.,2000).Each inter-

view transcript, set of observational notes, and document was read

severaltimes, generating and coding themes iteratively,in part

framed by literature;i.e. the sociology of professions literature

(Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984) framed our analysis of the epistemic

boundaries between organisationalscientists and health services

researchers.In part, codes emerged inductively,such as the sig-

nificance of hybrid academics in mediating epistemic boundaries

within social sciences. Analysis was conducted with the assistance

of NVivo 8,with material inputted into a database and coded ac-

cording to each high level category.

To preserve anonymity of respondents and cases in line with

ethics approval,but to reveal comparative analysis around the

dimension of epistemic boundaries,and reflecting our substantive

research concerns,we identify our respondents according to their

academic discipline or whether NHS employed, rather than by case.

We also identify each CLAHRC by label, Case A to Case I.

4. Findings

As a starting point for empirical analysis,we draw upon one of

many interviewees that called for further five year funding,

following the five year CLAHRC pilots,to sustain the CLAHRCs'

mission to bridge the translation gap:

The original plan on commissioning CLAHRCs was for the first

five years funding to be followed up by a further five years of

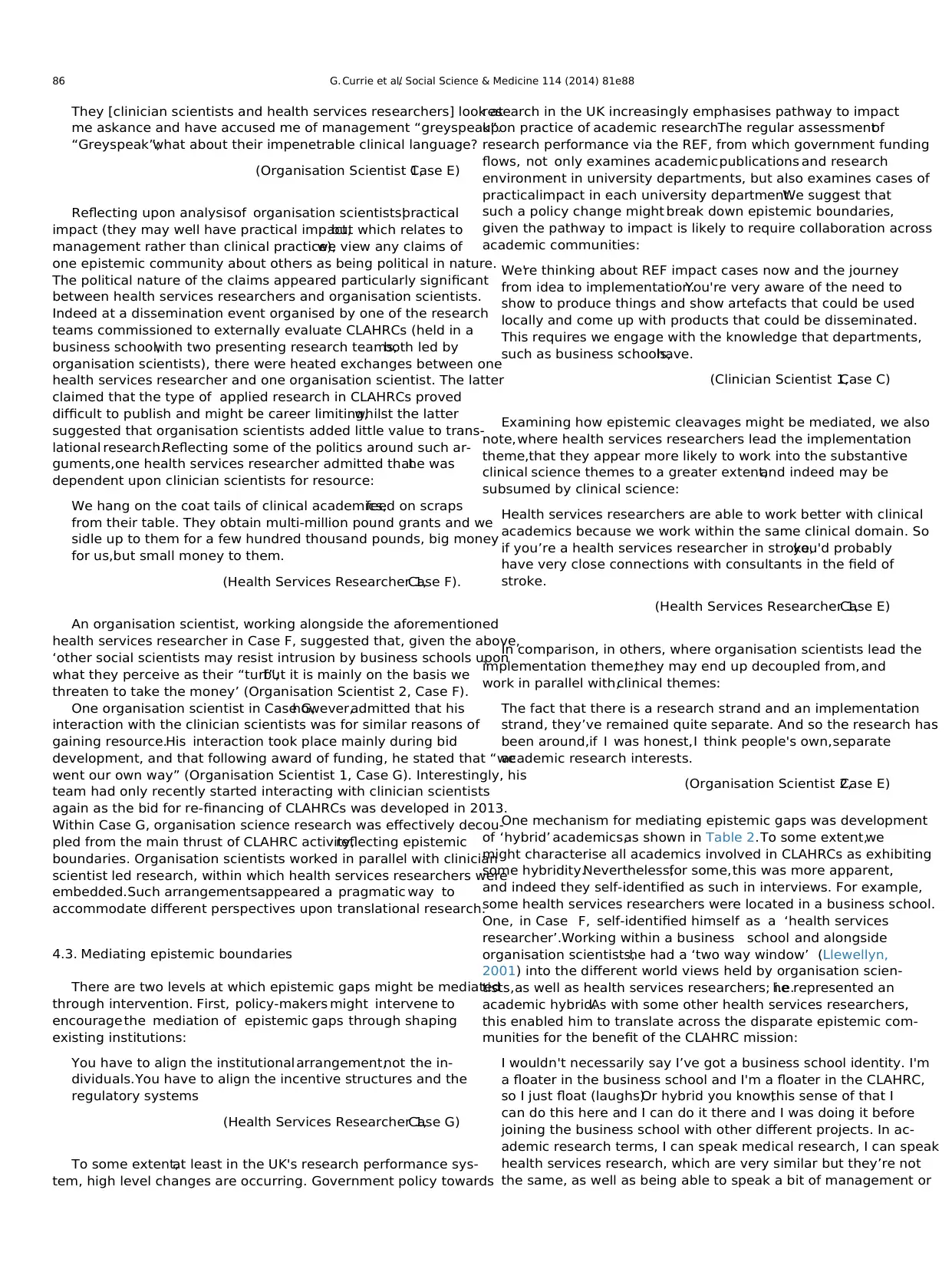

Table 1

Summary of interviewees.

Case Phase 1

interviews

Phase 2

interviews

No. clinician

scientists

No. organisation

scientists

No. health services

researchers

No. NHS

managers

No. clinicians Total no.

interviewees

A 6 3 0 1 2 0 6

B 21 16 14 11 2 5 5 37

C 5 23 7 8 9 2 2 28

D 16 16 14 3 2 9 4 32

E 18 7 1 3 6 1 18

F 10 2 3 2 3 0 10

G 13 15 5 2 2 16 3 28

H 12 4 0 3 3 2 12

I 3 1 0 1 1 0 3

Total no.

interviews

104 70 57 28 25 47 17 174

1 Albert et al.(2009: 175) use the term,‘clinician scientists’ because clinicians'

research activities are not restricted to clinical research,such as clinical trials and

case reports,but may include activities intersecting to some degree either with

social science or basic science.

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88 83

variation allowed for their structures and processes. Social sciences

were variably integrated into CLAHRC plans,with some involving

input from health services researchers located in or near to medical

schools,and others involving input from organisation scientists in

business schools;academic research and clinicalpractice were

blended in different ways; and there were differences in the disease

emphasis ofCLAHRCs,although all nine CLAHRCs focused upon

translational health research around long-term conditions.

Regarding the constituent epistemic communities upon whom

we focus within CLAHRC,we asked our respondents to self-define

themselvesas clinician scientists,1 health services researchers,

organisation scientists,NHS managers,and clinical practitioners.

We corroborated their self-definitions with our own assessment of

which epistemic community towards which they orientate (in all

cases,we agreed with the self-definition). We recognise,however,

that our categorisation is rather crude,and operates as a heuristic

device to aid theoretical analysis. Some academics, as discussed in

our empirical presentation,are not easily categorised and present

themselves as ‘hybrid’academics thatcross the boundaries of

epistemic communities.

Regarding the authors'own position, we are located in the

category oforganisation scientists,located in a business school

(although at least one of us might characterise himself/herself as

‘hybrid').We remained reflexive in our analysis to mediate any

partiality in analysis; e.g.analysis was presented to CLAHRC Di-

rectors (clinician scientists), other audiences where health services

researchers and clinician scientists were present. In support of our

impartial stance,we highlight analysis within the manuscript is

somewhat critical of our own community; e.g. as theoretically

driven with little concern for practical impact, as just chasing

research funding wherever its source and focus.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

We employed a longitudinal research strategy over a period of

three years to analyse interactions between constituent epistemic

communities of CLAHRC.Ethics approvalwas sought and gained

prior to commencing research (Research Ethics Committee refer-

ence: 10/H0402/6 Leicestershire,Northamptonshire and Rutland

Research Ethics Committee 2).CLAHRC Data presented in this

article is mainly drawn from 174 qualitative interviews carried out

between 2009 and 2012,encompassing a first,exploratory phase

across all 9 CLAHRCs (104 interviews), followed by a second phase

of data collection across four in-depth comparative cases (Cases B,

C, D, G: 70 interviews). Details of the interviewees are presented in

Table 1.

The interviews were focused on the challenges of collaborating

across epistemic communities of organisation scientists and health

services researchers,and how these might best be mediated.All

interviews were fully transcribed.Interviewing stopped when we

reached a point of theoretical saturation; i.e. when interviews were

only adding marginal increasesto our knowledge (Glaserand

Strauss, 1967).

Complementing the interview data,the research team spent

extensive time carrying out observational work,involving: atten-

dance at key meetings;workshops; presentations;other educa-

tional events. During all meetings and observations, detailed notes

were taken. Documentation was collected including: initial CLAHRC

bids; annual reports; study protocols; corporate publicity material;

minutes of operational and CLAHRC Board meetings.In Gephart's

terms,we developed ‘a substantial archival residue’ (1993: 1469)

from the different published sources.All interviews,observational

and documentary materialwere collated into a database,which

was organised on a case-by-case basis.

Data analysis was iterative and undertaken in an inductive

manner, but was informed by key concepts set out in the literature

review (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Pope et al.,2000).Each inter-

view transcript, set of observational notes, and document was read

severaltimes, generating and coding themes iteratively,in part

framed by literature;i.e. the sociology of professions literature

(Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 1984) framed our analysis of the epistemic

boundaries between organisationalscientists and health services

researchers.In part, codes emerged inductively,such as the sig-

nificance of hybrid academics in mediating epistemic boundaries

within social sciences. Analysis was conducted with the assistance

of NVivo 8,with material inputted into a database and coded ac-

cording to each high level category.

To preserve anonymity of respondents and cases in line with

ethics approval,but to reveal comparative analysis around the

dimension of epistemic boundaries,and reflecting our substantive

research concerns,we identify our respondents according to their

academic discipline or whether NHS employed, rather than by case.

We also identify each CLAHRC by label, Case A to Case I.

4. Findings

As a starting point for empirical analysis,we draw upon one of

many interviewees that called for further five year funding,

following the five year CLAHRC pilots,to sustain the CLAHRCs'

mission to bridge the translation gap:

The original plan on commissioning CLAHRCs was for the first

five years funding to be followed up by a further five years of

Table 1

Summary of interviewees.

Case Phase 1

interviews

Phase 2

interviews

No. clinician

scientists

No. organisation

scientists

No. health services

researchers

No. NHS

managers

No. clinicians Total no.

interviewees

A 6 3 0 1 2 0 6

B 21 16 14 11 2 5 5 37

C 5 23 7 8 9 2 2 28

D 16 16 14 3 2 9 4 32

E 18 7 1 3 6 1 18

F 10 2 3 2 3 0 10

G 13 15 5 2 2 16 3 28

H 12 4 0 3 3 2 12

I 3 1 0 1 1 0 3

Total no.

interviews

104 70 57 28 25 47 17 174

1 Albert et al.(2009: 175) use the term,‘clinician scientists’ because clinicians'

research activities are not restricted to clinical research,such as clinical trials and

case reports,but may include activities intersecting to some degree either with

social science or basic science.

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88 83

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

funding. In all honesty, we need that. We took a long time to get

going and the CLAHRC journey needs to continue,not just for

capacity building purposes,but because success has been vari-

able.For every clinicalstudy that has bridged the translation

gap, another has failed. In large part the academic side has failed

to get their act together around improvement science.

(NHS Manager 1, Case B)

Regarding our theoreticalconcerns,the last sentence in the

quote above is particularly interesting in highlighting the ‘failure’

within the academic community itselfto cohere around trans-

lational health research. Following such assertions, we examine the

epistemic gap within the academic community itself,between

organisation scientistsand health services researchers,and in

which clinician scientists are implicated.

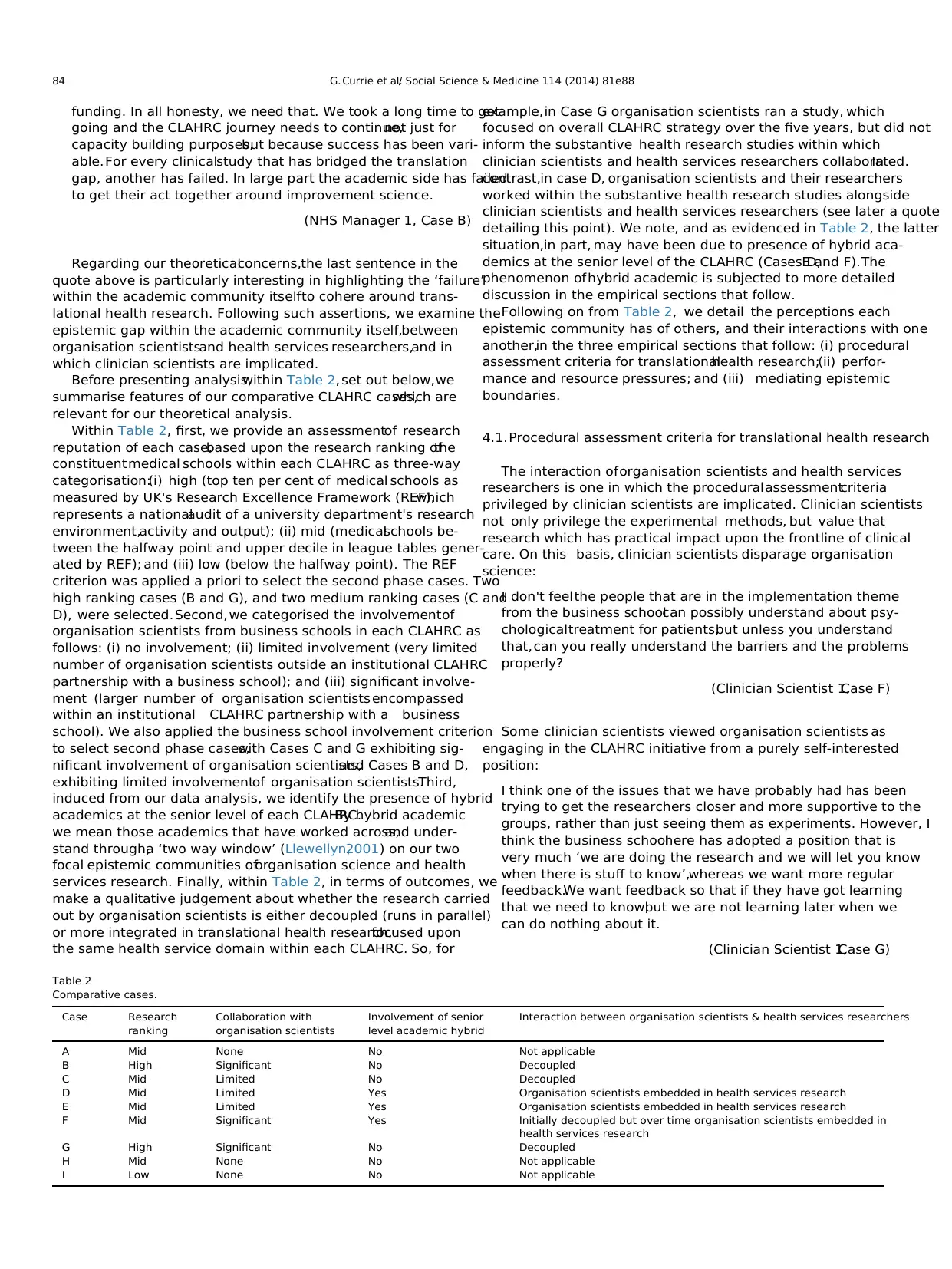

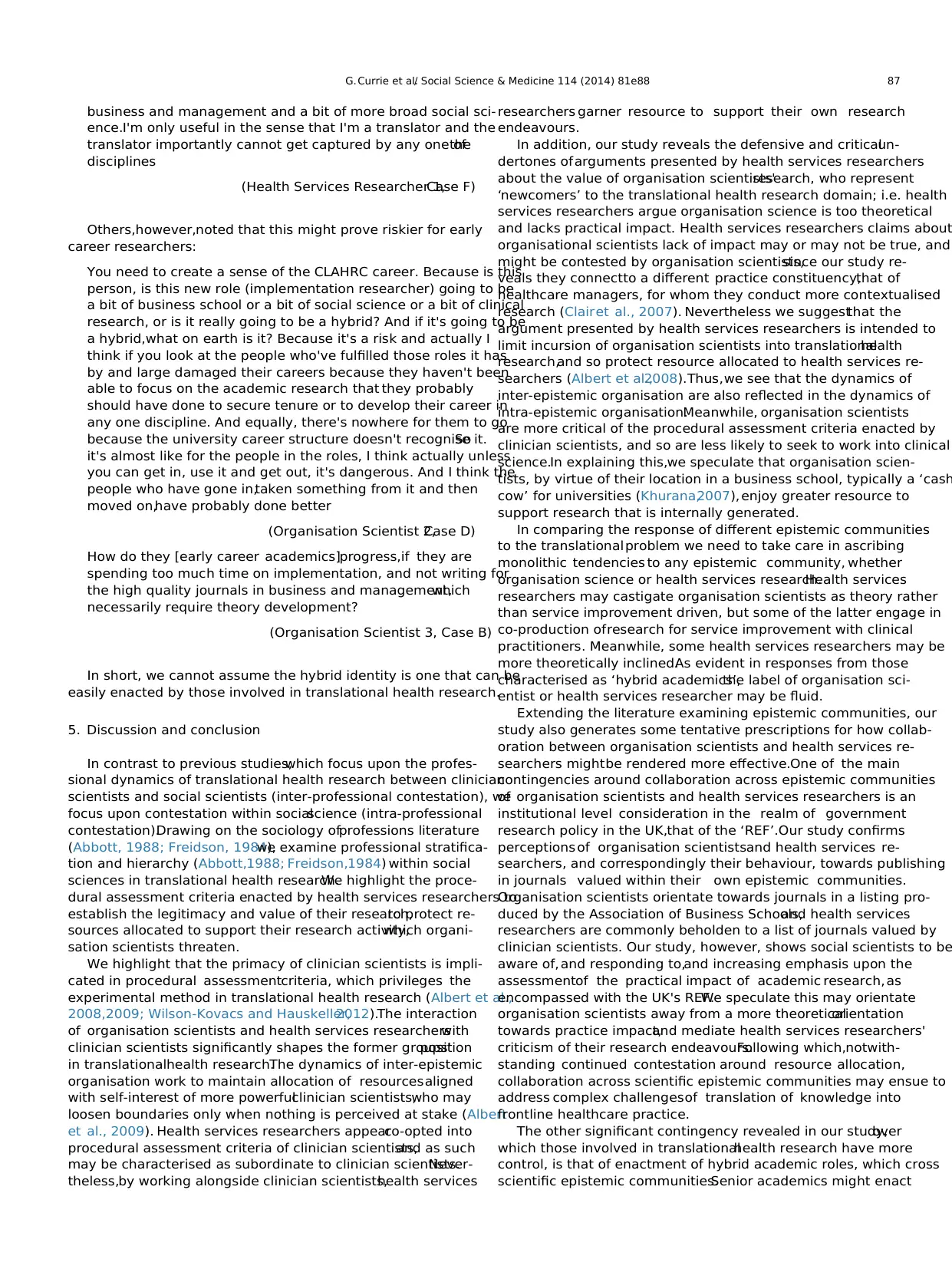

Before presenting analysis,within Table 2, set out below,we

summarise features of our comparative CLAHRC cases,which are

relevant for our theoretical analysis.

Within Table 2, first, we provide an assessmentof research

reputation of each case,based upon the research ranking ofthe

constituentmedical schools within each CLAHRC as three-way

categorisation:(i) high (top ten per cent of medical schools as

measured by UK's Research Excellence Framework (REF),which

represents a nationalaudit of a university department's research

environment,activity and output); (ii) mid (medicalschools be-

tween the halfway point and upper decile in league tables gener-

ated by REF); and (iii) low (below the halfway point). The REF

criterion was applied a priori to select the second phase cases. Two

high ranking cases (B and G), and two medium ranking cases (C and

D), were selected. Second,we categorised the involvementof

organisation scientists from business schools in each CLAHRC as

follows: (i) no involvement; (ii) limited involvement (very limited

number of organisation scientists outside an institutional CLAHRC

partnership with a business school); and (iii) significant involve-

ment (larger number of organisation scientists encompassed

within an institutional CLAHRC partnership with a business

school). We also applied the business school involvement criterion

to select second phase cases,with Cases C and G exhibiting sig-

nificant involvement of organisation scientists,and Cases B and D,

exhibiting limited involvementof organisation scientists.Third,

induced from our data analysis, we identify the presence of hybrid

academics at the senior level of each CLAHRC.By hybrid academic

we mean those academics that have worked across,and under-

stand through,a ‘two way window’ (Llewellyn,2001) on our two

focal epistemic communities oforganisation science and health

services research. Finally, within Table 2, in terms of outcomes, we

make a qualitative judgement about whether the research carried

out by organisation scientists is either decoupled (runs in parallel)

or more integrated in translational health research,focused upon

the same health service domain within each CLAHRC. So, for

example,in Case G organisation scientists ran a study, which

focused on overall CLAHRC strategy over the five years, but did not

inform the substantive health research studies within which

clinician scientists and health services researchers collaborated.In

contrast,in case D, organisation scientists and their researchers

worked within the substantive health research studies alongside

clinician scientists and health services researchers (see later a quote

detailing this point). We note, and as evidenced in Table 2, the latter

situation,in part, may have been due to presence of hybrid aca-

demics at the senior level of the CLAHRC (Cases D,E and F).The

phenomenon of hybrid academic is subjected to more detailed

discussion in the empirical sections that follow.

Following on from Table 2, we detail the perceptions each

epistemic community has of others, and their interactions with one

another,in the three empirical sections that follow: (i) procedural

assessment criteria for translationalhealth research;(ii) perfor-

mance and resource pressures; and (iii) mediating epistemic

boundaries.

4.1.Procedural assessment criteria for translational health research

The interaction oforganisation scientists and health services

researchers is one in which the proceduralassessmentcriteria

privileged by clinician scientists are implicated. Clinician scientists

not only privilege the experimental methods, but value that

research which has practical impact upon the frontline of clinical

care. On this basis, clinician scientists disparage organisation

science:

I don't feelthe people that are in the implementation theme

from the business schoolcan possibly understand about psy-

chologicaltreatment for patients,but unless you understand

that,can you really understand the barriers and the problems

properly?

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case F)

Some clinician scientists viewed organisation scientists as

engaging in the CLAHRC initiative from a purely self-interested

position:

I think one of the issues that we have probably had has been

trying to get the researchers closer and more supportive to the

groups, rather than just seeing them as experiments. However, I

think the business schoolhere has adopted a position that is

very much ‘we are doing the research and we will let you know

when there is stuff to know’,whereas we want more regular

feedback.We want feedback so that if they have got learning

that we need to know,but we are not learning later when we

can do nothing about it.

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case G)

Table 2

Comparative cases.

Case Research

ranking

Collaboration with

organisation scientists

Involvement of senior

level academic hybrid

Interaction between organisation scientists & health services researchers

A Mid None No Not applicable

B High Significant No Decoupled

C Mid Limited No Decoupled

D Mid Limited Yes Organisation scientists embedded in health services research

E Mid Limited Yes Organisation scientists embedded in health services research

F Mid Significant Yes Initially decoupled but over time organisation scientists embedded in

health services research

G High Significant No Decoupled

H Mid None No Not applicable

I Low None No Not applicable

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e8884

going and the CLAHRC journey needs to continue,not just for

capacity building purposes,but because success has been vari-

able.For every clinicalstudy that has bridged the translation

gap, another has failed. In large part the academic side has failed

to get their act together around improvement science.

(NHS Manager 1, Case B)

Regarding our theoreticalconcerns,the last sentence in the

quote above is particularly interesting in highlighting the ‘failure’

within the academic community itselfto cohere around trans-

lational health research. Following such assertions, we examine the

epistemic gap within the academic community itself,between

organisation scientistsand health services researchers,and in

which clinician scientists are implicated.

Before presenting analysis,within Table 2, set out below,we

summarise features of our comparative CLAHRC cases,which are

relevant for our theoretical analysis.

Within Table 2, first, we provide an assessmentof research

reputation of each case,based upon the research ranking ofthe

constituentmedical schools within each CLAHRC as three-way

categorisation:(i) high (top ten per cent of medical schools as

measured by UK's Research Excellence Framework (REF),which

represents a nationalaudit of a university department's research

environment,activity and output); (ii) mid (medicalschools be-

tween the halfway point and upper decile in league tables gener-

ated by REF); and (iii) low (below the halfway point). The REF

criterion was applied a priori to select the second phase cases. Two

high ranking cases (B and G), and two medium ranking cases (C and

D), were selected. Second,we categorised the involvementof

organisation scientists from business schools in each CLAHRC as

follows: (i) no involvement; (ii) limited involvement (very limited

number of organisation scientists outside an institutional CLAHRC

partnership with a business school); and (iii) significant involve-

ment (larger number of organisation scientists encompassed

within an institutional CLAHRC partnership with a business

school). We also applied the business school involvement criterion

to select second phase cases,with Cases C and G exhibiting sig-

nificant involvement of organisation scientists,and Cases B and D,

exhibiting limited involvementof organisation scientists.Third,

induced from our data analysis, we identify the presence of hybrid

academics at the senior level of each CLAHRC.By hybrid academic

we mean those academics that have worked across,and under-

stand through,a ‘two way window’ (Llewellyn,2001) on our two

focal epistemic communities oforganisation science and health

services research. Finally, within Table 2, in terms of outcomes, we

make a qualitative judgement about whether the research carried

out by organisation scientists is either decoupled (runs in parallel)

or more integrated in translational health research,focused upon

the same health service domain within each CLAHRC. So, for

example,in Case G organisation scientists ran a study, which

focused on overall CLAHRC strategy over the five years, but did not

inform the substantive health research studies within which

clinician scientists and health services researchers collaborated.In

contrast,in case D, organisation scientists and their researchers

worked within the substantive health research studies alongside

clinician scientists and health services researchers (see later a quote

detailing this point). We note, and as evidenced in Table 2, the latter

situation,in part, may have been due to presence of hybrid aca-

demics at the senior level of the CLAHRC (Cases D,E and F).The

phenomenon of hybrid academic is subjected to more detailed

discussion in the empirical sections that follow.

Following on from Table 2, we detail the perceptions each

epistemic community has of others, and their interactions with one

another,in the three empirical sections that follow: (i) procedural

assessment criteria for translationalhealth research;(ii) perfor-

mance and resource pressures; and (iii) mediating epistemic

boundaries.

4.1.Procedural assessment criteria for translational health research

The interaction oforganisation scientists and health services

researchers is one in which the proceduralassessmentcriteria

privileged by clinician scientists are implicated. Clinician scientists

not only privilege the experimental methods, but value that

research which has practical impact upon the frontline of clinical

care. On this basis, clinician scientists disparage organisation

science:

I don't feelthe people that are in the implementation theme

from the business schoolcan possibly understand about psy-

chologicaltreatment for patients,but unless you understand

that,can you really understand the barriers and the problems

properly?

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case F)

Some clinician scientists viewed organisation scientists as

engaging in the CLAHRC initiative from a purely self-interested

position:

I think one of the issues that we have probably had has been

trying to get the researchers closer and more supportive to the

groups, rather than just seeing them as experiments. However, I

think the business schoolhere has adopted a position that is

very much ‘we are doing the research and we will let you know

when there is stuff to know’,whereas we want more regular

feedback.We want feedback so that if they have got learning

that we need to know,but we are not learning later when we

can do nothing about it.

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case G)

Table 2

Comparative cases.

Case Research

ranking

Collaboration with

organisation scientists

Involvement of senior

level academic hybrid

Interaction between organisation scientists & health services researchers

A Mid None No Not applicable

B High Significant No Decoupled

C Mid Limited No Decoupled

D Mid Limited Yes Organisation scientists embedded in health services research

E Mid Limited Yes Organisation scientists embedded in health services research

F Mid Significant Yes Initially decoupled but over time organisation scientists embedded in

health services research

G High Significant No Decoupled

H Mid None No Not applicable

I Low None No Not applicable

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e8884

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The response of organisation scientists is ambivalent towards

criticism by clinician scientists.Indeed they might be seen to dis-

tance themselves from the research endeavours of clinician scien-

tists through orientating towards a distinct procedural assessment

criteria,which privileges more theoretical research:

I think they (clinician scientists)expected thatthe business

school might facilitate their work,rather than come up with

work of their own. However, we want to understand the

organisational processes around knowledge sharing, not

necessarily to push along their research […] they don't under-

stand this area of scholarship […] I really don't feel understood

by the clinical community.What we want to do is to concep-

tualise and generate theory,rather than tell them how they

should do it.

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case B)

At the same time,organisation scientists criticise those experi-

mental methods privileged by clinician scientists,with the latter

seeking to defend their expertise:

It does annoy me how [the respondent is focussing upon orga-

nisation scientists at this point in the interview], social sciences

come along and criticise randomised controltrials, which is

something they don't know a lot about. So they come along and

say blah,blah,blah,about randomised control trials and I just

know they are talking rubbish.They don't understand what

randomised controltrials do. I feel that the current sway of

those (social) sciences is undervaluing clinicalscience and is

likely, if we continue to do that it is likely to drive away and

offend an awful lot of clinical researchers.

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case D)

In contrast,unlike organisation scientists,whilst they may not

enact experimental methods, health services researchers take their

cue from clinician scientists in privileging impact upon the front-

line of clinical delivery, something they claim their own research is

set up to realise:

I see the NHS as a place to do research. For me personally I see it

as a place to make a difference to patient care and I think that

does come from my roots you know, that I actually want to be in

there doing it and the research is part and parcel of that. I don't

just want to go in and do it at a distance you know,observe or

contribute at a distance,develop new theoreticalinsights but

then don't have a commitment to then apply what they know in

a very practical way to make a difference.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case E)

But, health services researchers claim that organisation scien-

tists are not set up to realise such practical impact. Health services

researchers commented upon opportunistic behaviourof some

organisation scientists working in business schools:

They don't engage with the health service audience because

they’re engaged in developing esoteric theory first and fore-

most, for academic business and managementjournals. The

health service is just a case study,whereas for me, I guess

traditionally I would have been the opposite because I'm trying

to fix healthcare problems. If all the funding for health services

research dried up,business and managementwouldn't care,

they'd move on to wherever the next funding would be.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case I)

However,our study suggests the practical impact of organisa-

tion scientists may lie less in the domain of clinical delivery,and

more in the domain of healthcare management.The practice

epistemic community to which organisation scientists relate is that

of NHS managers. Indeed, organisation scientistsperceived a

greater receptivity towards their translational research from NHS

managers, as compared to other scientific epistemic communities:

When I go along to present leadership or knowledge manage-

ment at one of our healthcare partners, I am guaranteed a much

more favourable reception from their managers than from my

clinical science collaborators.

(Organisation Scientist 2,Case F)

Notwithstanding those organisation scientists more orientated

towards theory generation,some were concerned to draw health-

care practitioners into their research,and consider the organisa-

tional and managerialimplications associated with translational

health research:

I think the words should be knowledge exchange,not knowl-

edge transfer.I am being rather pedantic because knowledge

transfer infers that we,the clever people in the university who

are doing research,know the answers and you the silly practi-

tioners who are out there doing it need to learn from us and I

don't accept that. I think what I would say is we are not driven

by the practitioners,but we are engaging the practitioners.

(Organisation Scientist 2,Case C)

In the next empirical section, we consider further why tensions

exist between organisation scientists and health services

researchers.

4.2. Performance and resource pressures

Decoupling of,rather than collaborative,research across the

epistemic communities of organisationalscientists and health

services researcherswas, in part, a consequenceof coercive

pressures:

We serve the REF.And even if you have clinical academics and

social science academics, we serve different REF panels, so that

pushes us in certain directions towards peer-reviewed

publications.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case F)

Being pushed in a particular publication trajectory appeared

very significant for organisation scientists:

We are bound by an institutionalised list of journals, developed

by Association of Business Schools. These are graded from high,

four star, to low quality, no or one star. In this respect, we are a

bit more constrained than others.I could publish in the top

clinical journal and it wouldn't count in a business school.

Health services researchers,meanwhile,seem more able to

publish in clinical journals,but these seem the lower quality

ones as judged by clinical academics

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case B).

The more coercive influences that caused epistemic commu-

nities to diverge were buttressed by normative forces. Each

epistemic community viewed the language of the others as opaque:

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88 85

criticism by clinician scientists.Indeed they might be seen to dis-

tance themselves from the research endeavours of clinician scien-

tists through orientating towards a distinct procedural assessment

criteria,which privileges more theoretical research:

I think they (clinician scientists)expected thatthe business

school might facilitate their work,rather than come up with

work of their own. However, we want to understand the

organisational processes around knowledge sharing, not

necessarily to push along their research […] they don't under-

stand this area of scholarship […] I really don't feel understood

by the clinical community.What we want to do is to concep-

tualise and generate theory,rather than tell them how they

should do it.

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case B)

At the same time,organisation scientists criticise those experi-

mental methods privileged by clinician scientists,with the latter

seeking to defend their expertise:

It does annoy me how [the respondent is focussing upon orga-

nisation scientists at this point in the interview], social sciences

come along and criticise randomised controltrials, which is

something they don't know a lot about. So they come along and

say blah,blah,blah,about randomised control trials and I just

know they are talking rubbish.They don't understand what

randomised controltrials do. I feel that the current sway of

those (social) sciences is undervaluing clinicalscience and is

likely, if we continue to do that it is likely to drive away and

offend an awful lot of clinical researchers.

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case D)

In contrast,unlike organisation scientists,whilst they may not

enact experimental methods, health services researchers take their

cue from clinician scientists in privileging impact upon the front-

line of clinical delivery, something they claim their own research is

set up to realise:

I see the NHS as a place to do research. For me personally I see it

as a place to make a difference to patient care and I think that

does come from my roots you know, that I actually want to be in

there doing it and the research is part and parcel of that. I don't

just want to go in and do it at a distance you know,observe or

contribute at a distance,develop new theoreticalinsights but

then don't have a commitment to then apply what they know in

a very practical way to make a difference.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case E)

But, health services researchers claim that organisation scien-

tists are not set up to realise such practical impact. Health services

researchers commented upon opportunistic behaviourof some

organisation scientists working in business schools:

They don't engage with the health service audience because

they’re engaged in developing esoteric theory first and fore-

most, for academic business and managementjournals. The

health service is just a case study,whereas for me, I guess

traditionally I would have been the opposite because I'm trying

to fix healthcare problems. If all the funding for health services

research dried up,business and managementwouldn't care,

they'd move on to wherever the next funding would be.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case I)

However,our study suggests the practical impact of organisa-

tion scientists may lie less in the domain of clinical delivery,and

more in the domain of healthcare management.The practice

epistemic community to which organisation scientists relate is that

of NHS managers. Indeed, organisation scientistsperceived a

greater receptivity towards their translational research from NHS

managers, as compared to other scientific epistemic communities:

When I go along to present leadership or knowledge manage-

ment at one of our healthcare partners, I am guaranteed a much

more favourable reception from their managers than from my

clinical science collaborators.

(Organisation Scientist 2,Case F)

Notwithstanding those organisation scientists more orientated

towards theory generation,some were concerned to draw health-

care practitioners into their research,and consider the organisa-

tional and managerialimplications associated with translational

health research:

I think the words should be knowledge exchange,not knowl-

edge transfer.I am being rather pedantic because knowledge

transfer infers that we,the clever people in the university who

are doing research,know the answers and you the silly practi-

tioners who are out there doing it need to learn from us and I

don't accept that. I think what I would say is we are not driven

by the practitioners,but we are engaging the practitioners.

(Organisation Scientist 2,Case C)

In the next empirical section, we consider further why tensions

exist between organisation scientists and health services

researchers.

4.2. Performance and resource pressures

Decoupling of,rather than collaborative,research across the

epistemic communities of organisationalscientists and health

services researcherswas, in part, a consequenceof coercive

pressures:

We serve the REF.And even if you have clinical academics and

social science academics, we serve different REF panels, so that

pushes us in certain directions towards peer-reviewed

publications.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case F)

Being pushed in a particular publication trajectory appeared

very significant for organisation scientists:

We are bound by an institutionalised list of journals, developed

by Association of Business Schools. These are graded from high,

four star, to low quality, no or one star. In this respect, we are a

bit more constrained than others.I could publish in the top

clinical journal and it wouldn't count in a business school.

Health services researchers,meanwhile,seem more able to

publish in clinical journals,but these seem the lower quality

ones as judged by clinical academics

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case B).

The more coercive influences that caused epistemic commu-

nities to diverge were buttressed by normative forces. Each

epistemic community viewed the language of the others as opaque:

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e88 85

They [clinician scientists and health services researchers] look at

me askance and have accused me of management “greyspeak”.

“Greyspeak”,what about their impenetrable clinical language?

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case E)

Reflecting upon analysisof organisation scientists'practical

impact (they may well have practical impact,but which relates to

management rather than clinical practice),we view any claims of

one epistemic community about others as being political in nature.

The political nature of the claims appeared particularly significant

between health services researchers and organisation scientists.

Indeed at a dissemination event organised by one of the research

teams commissioned to externally evaluate CLAHRCs (held in a

business school,with two presenting research teams,both led by

organisation scientists), there were heated exchanges between one

health services researcher and one organisation scientist. The latter

claimed that the type of applied research in CLAHRCs proved

difficult to publish and might be career limiting,whilst the latter

suggested that organisation scientists added little value to trans-

lational research.Reflecting some of the politics around such ar-

guments,one health services researcher admitted thathe was

dependent upon clinician scientists for resource:

We hang on the coat tails of clinical academics,feed on scraps

from their table. They obtain multi-million pound grants and we

sidle up to them for a few hundred thousand pounds, big money

for us,but small money to them.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case F).

An organisation scientist, working alongside the aforementioned

health services researcher in Case F, suggested that, given the above,

‘other social scientists may resist intrusion by business schools upon

what they perceive as their “turf”,but it is mainly on the basis we

threaten to take the money’ (Organisation Scientist 2, Case F).

One organisation scientist in Case G,however,admitted that his

interaction with the clinician scientists was for similar reasons of

gaining resource.His interaction took place mainly during bid

development, and that following award of funding, he stated that “we

went our own way” (Organisation Scientist 1, Case G). Interestingly, his

team had only recently started interacting with clinician scientists

again as the bid for re-financing of CLAHRCs was developed in 2013.

Within Case G, organisation science research was effectively decou-

pled from the main thrust of CLAHRC activity,reflecting epistemic

boundaries. Organisation scientists worked in parallel with clinician

scientist led research, within which health services researchers were

embedded.Such arrangementsappeared a pragmatic way to

accommodate different perspectives upon translational research.

4.3. Mediating epistemic boundaries

There are two levels at which epistemic gaps might be mediated

through intervention. First, policy-makers might intervene to

encourage the mediation of epistemic gaps through shaping

existing institutions:

You have to align the institutional arrangement,not the in-

dividuals.You have to align the incentive structures and the

regulatory systems

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case G)

To some extent,at least in the UK's research performance sys-

tem, high level changes are occurring. Government policy towards

research in the UK increasingly emphasises pathway to impact

upon practice of academic research.The regular assessmentof

research performance via the REF, from which government funding

flows, not only examines academicpublications and research

environment in university departments, but also examines cases of

practicalimpact in each university department.We suggest that

such a policy change might break down epistemic boundaries,

given the pathway to impact is likely to require collaboration across

academic communities:

We're thinking about REF impact cases now and the journey

from idea to implementation.You're very aware of the need to

show to produce things and show artefacts that could be used

locally and come up with products that could be disseminated.

This requires we engage with the knowledge that departments,

such as business schools,have.

(Clinician Scientist 1,Case C)

Examining how epistemic cleavages might be mediated, we also

note,where health services researchers lead the implementation

theme,that they appear more likely to work into the substantive

clinical science themes to a greater extent,and indeed may be

subsumed by clinical science:

Health services researchers are able to work better with clinical

academics because we work within the same clinical domain. So

if you’re a health services researcher in stroke,you'd probably

have very close connections with consultants in the field of

stroke.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case E)

In comparison, in others, where organisation scientists lead the

implementation theme,they may end up decoupled from,and

work in parallel with,clinical themes:

The fact that there is a research strand and an implementation

strand, they’ve remained quite separate. And so the research has

been around,if I was honest,I think people's own,separate

academic research interests.

(Organisation Scientist 2,Case E)

One mechanism for mediating epistemic gaps was development

of ‘hybrid’ academics,as shown in Table 2.To some extent,we

might characterise all academics involved in CLAHRCs as exhibiting

some hybridity.Nevertheless,for some,this was more apparent,

and indeed they self-identified as such in interviews. For example,

some health services researchers were located in a business school.

One, in Case F, self-identified himself as a ‘health services

researcher’.Working within a business school and alongside

organisation scientists,he had a ‘two way window’ (Llewellyn,

2001) into the different world views held by organisation scien-

tists,as well as health services researchers; i.e.he represented an

academic hybrid.As with some other health services researchers,

this enabled him to translate across the disparate epistemic com-

munities for the benefit of the CLAHRC mission:

I wouldn't necessarily say I’ve got a business school identity. I'm

a floater in the business school and I'm a floater in the CLAHRC,

so I just float (laughs).Or hybrid you know,this sense of that I

can do this here and I can do it there and I was doing it before

joining the business school with other different projects. In ac-

ademic research terms, I can speak medical research, I can speak

health services research, which are very similar but they’re not

the same, as well as being able to speak a bit of management or

G. Currie et al./ Social Science & Medicine 114 (2014) 81e8886

me askance and have accused me of management “greyspeak”.

“Greyspeak”,what about their impenetrable clinical language?

(Organisation Scientist 1,Case E)

Reflecting upon analysisof organisation scientists'practical

impact (they may well have practical impact,but which relates to

management rather than clinical practice),we view any claims of

one epistemic community about others as being political in nature.

The political nature of the claims appeared particularly significant

between health services researchers and organisation scientists.

Indeed at a dissemination event organised by one of the research

teams commissioned to externally evaluate CLAHRCs (held in a

business school,with two presenting research teams,both led by

organisation scientists), there were heated exchanges between one

health services researcher and one organisation scientist. The latter

claimed that the type of applied research in CLAHRCs proved

difficult to publish and might be career limiting,whilst the latter

suggested that organisation scientists added little value to trans-

lational research.Reflecting some of the politics around such ar-

guments,one health services researcher admitted thathe was

dependent upon clinician scientists for resource:

We hang on the coat tails of clinical academics,feed on scraps

from their table. They obtain multi-million pound grants and we

sidle up to them for a few hundred thousand pounds, big money

for us,but small money to them.

(Health Services Researcher 1,Case F).

An organisation scientist, working alongside the aforementioned

health services researcher in Case F, suggested that, given the above,

‘other social scientists may resist intrusion by business schools upon

what they perceive as their “turf”,but it is mainly on the basis we

threaten to take the money’ (Organisation Scientist 2, Case F).

One organisation scientist in Case G,however,admitted that his