Analysis of Corporate Governance and CSR Disclosure in US Banks

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/08

|15

|10917

|293

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the relationship between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in the US banking sector, particularly focusing on the post-subprime mortgage crisis period. The study examines the impact of board of directors' characteristics, such as independence, size, and CEO duality, on the quality of CSR disclosure in annual reports of large US commercial banks from 2009 to 2011. Using content analysis, the research finds that board independence and size positively influence CSR disclosure, suggesting that these corporate governance mechanisms, designed to protect shareholder interests, also promote the interests of other stakeholders regarding CSR reporting. Surprisingly, CEO duality also positively affects CSR disclosure, potentially indicating powerful CEOs promoting transparency for their private benefits or due to pressure from stakeholders. The report highlights the importance of CSR reporting for banks' sustainability and the need for effective corporate governance to balance financial and social objectives. The study fills a gap in existing research by focusing on the link between corporate governance and CSR disclosure in the banking sector, emphasizing the significance of annual reports as key documents for stakeholders.

Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility

Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector

Mohammad Issam Jizi• Aly Salama•

Robert Dixon• Rebecca Stratling

Received: 4 February 2013 / Accepted: 14 October 2013

Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract There isa distinctlack of research into the

relationship between corporate governance and corporate

socialresponsibility (CSR)in the banking sector.This

paper fills the gap in the literature by examining the impact

of corporate governance,with particular reference to the

role of board of directors, on the quality of CSR disclosure

in US listed banks’ annual reports after the US sub-prime

mortgage crisis.Using a sample of large US commercial

banks for the period 2009–2011 and controlling for audit

committee characteristics,board meeting frequency,and

banks’profitability,size and risk,we find evidence that

board independence and board size,the two board char-

acteristics usually associated with the protection of share-

holder interests,are positively related to CSR disclosure.

This indicates that,with regard to CSR disclosure,more

independentboards of directors and larger boards are the

internal corporate governance mechanisms which promote

both shareholders’ and other stakeholders’ interests.Con-

trary to our expectations,CEO duality also impacts posi-

tively on CSR disclosure.From an agency-theoretical

viewpoint, this suggests that powerful CEOs may promote

transparency about banks’ CSR activities for their private

benefits. While this could indicate that powerful CEOs are

under particular pressure to appease stakeholders’ concer

thatthey mightabuse theirpowerby providing a high

degree of CSR disclosure,it could also be a sign of man-

agerialrisk aversion ormanagers’privatereputational

concerns.

Keywords Corporate governance CSR disclosure

US Banks Content analysis Financial crisis

Introduction

Financial institutions, in particular banks, have come unde

increasing pressure,since the sub-prime mortgage crisis

and the following creditcrunch to take a more long-term

view of their investors’businessinterestsand to

acknowledge and respond to theirobligations to society

(Matten 2006; Money and Schepers 2007; Gill 2008; Grove

et al. 2011). Due to the extensive negative external effect

poorly managed and controlled bankscan imposeon

society,the perceptionof the firms’ corporatesocial

responsibility (CSR)activities is importantnot only for

investors’and customers’risk assessment,but also for

regulators’ good-will and for the public’s confidence in the

financial system.

Extensive priorresearch suggeststhatCSR reporting

can impact positively on stakeholders’ perceptions of firm

performance,firm value and firm risk,and thereby on

firms’profitability,costof capitaland share price (Gray

et al. 1995b;Simpson and Kohers 2002;Scholtens 2008;

Godfrey et al. 2009; Salama et al. 2011; Ghoul et al. 2011

Cormier etal. 2011;Lourenco etal. 2012).Moreover,as

CSR reporting contributes to the reduction of information

asymmetry between managersand investorsas well as

other stakeholders,comprehensive CSR reporting aids the

M. I. Jizi (&)

Lebanese American University,Business School,Beirut,

Lebanon

e-mail: mohammad.jizi@lau.edu.lb

A. Salama R.Dixon R. Stratling

Durham University,Durham Business School,Durham,UK

e-mail: aly.salama@durham.ac.uk

R. Dixon

e-mail: rob.dixon@durham.ac.uk

R. Stratling

e-mail: rebecca.stratling@durham.ac.uk

123

J Bus Ethics

DOI 10.1007/s10551-013-1929-2

Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector

Mohammad Issam Jizi• Aly Salama•

Robert Dixon• Rebecca Stratling

Received: 4 February 2013 / Accepted: 14 October 2013

Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract There isa distinctlack of research into the

relationship between corporate governance and corporate

socialresponsibility (CSR)in the banking sector.This

paper fills the gap in the literature by examining the impact

of corporate governance,with particular reference to the

role of board of directors, on the quality of CSR disclosure

in US listed banks’ annual reports after the US sub-prime

mortgage crisis.Using a sample of large US commercial

banks for the period 2009–2011 and controlling for audit

committee characteristics,board meeting frequency,and

banks’profitability,size and risk,we find evidence that

board independence and board size,the two board char-

acteristics usually associated with the protection of share-

holder interests,are positively related to CSR disclosure.

This indicates that,with regard to CSR disclosure,more

independentboards of directors and larger boards are the

internal corporate governance mechanisms which promote

both shareholders’ and other stakeholders’ interests.Con-

trary to our expectations,CEO duality also impacts posi-

tively on CSR disclosure.From an agency-theoretical

viewpoint, this suggests that powerful CEOs may promote

transparency about banks’ CSR activities for their private

benefits. While this could indicate that powerful CEOs are

under particular pressure to appease stakeholders’ concer

thatthey mightabuse theirpowerby providing a high

degree of CSR disclosure,it could also be a sign of man-

agerialrisk aversion ormanagers’privatereputational

concerns.

Keywords Corporate governance CSR disclosure

US Banks Content analysis Financial crisis

Introduction

Financial institutions, in particular banks, have come unde

increasing pressure,since the sub-prime mortgage crisis

and the following creditcrunch to take a more long-term

view of their investors’businessinterestsand to

acknowledge and respond to theirobligations to society

(Matten 2006; Money and Schepers 2007; Gill 2008; Grove

et al. 2011). Due to the extensive negative external effect

poorly managed and controlled bankscan imposeon

society,the perceptionof the firms’ corporatesocial

responsibility (CSR)activities is importantnot only for

investors’and customers’risk assessment,but also for

regulators’ good-will and for the public’s confidence in the

financial system.

Extensive priorresearch suggeststhatCSR reporting

can impact positively on stakeholders’ perceptions of firm

performance,firm value and firm risk,and thereby on

firms’profitability,costof capitaland share price (Gray

et al. 1995b;Simpson and Kohers 2002;Scholtens 2008;

Godfrey et al. 2009; Salama et al. 2011; Ghoul et al. 2011

Cormier etal. 2011;Lourenco etal. 2012).Moreover,as

CSR reporting contributes to the reduction of information

asymmetry between managersand investorsas well as

other stakeholders,comprehensive CSR reporting aids the

M. I. Jizi (&)

Lebanese American University,Business School,Beirut,

Lebanon

e-mail: mohammad.jizi@lau.edu.lb

A. Salama R.Dixon R. Stratling

Durham University,Durham Business School,Durham,UK

e-mail: aly.salama@durham.ac.uk

R. Dixon

e-mail: rob.dixon@durham.ac.uk

R. Stratling

e-mail: rebecca.stratling@durham.ac.uk

123

J Bus Ethics

DOI 10.1007/s10551-013-1929-2

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

supervision and controlof managers.Effective boards of

directors are therefore expected to promote CSR reporting

(Jamali et al.2008).

Given the potentialimpactof CSR reporting on firms’

sustainability,there is a surprising dearth of research into

the impactof corporate governance on CSR disclosure.

Existing research mainly concentrates on the influence of

CSR committees on CSR disclosure (Gill2008;Spitzeck

2009;Li et al. 2010;Kolk and Pinkse 2010) and largely

neglects investigating whetherkey characteristics ofthe

board of directors impact on the reporting of CSR-related

issues.As the board ofdirectorsis responsible forthe

developmentof sustainablebusinessstrategiesand the

supervision of the responsible use of the firms’ assets, it is

the board which takes the crucial decisions in relation to a

firm’s CSR policies. If firms engage in CSR activities and

reporting notmerely asa temporary fad orto appease

managers’personalmoralconcerns(Porterand Kramer

2006; Hennigfeld et al. 2006), but to acknowledge societal

concernsand maintain positiverelationshipswith key

stakeholders in order to improve the sustainability of the

business,one would expect that firms with more effective

boards structures will be particularly diligent in providing

information on CSR-related issues.Accordingly,and in

light of increasing public, customer and investor pressures,

corporate governance features,such as board characteris-

tics, which were originally designed mainly to protect

shareholder interests (Fama 1980; Hermalin and Weisbach

1998, 2003), might be effective in encouraging managerial

stewardship for the benefit of a wide range of stakeholders.

Understanding the link between corporate governance,

in particularboard characteristics,and CSR reporting is

importantfor banks,because of their potentialsignificant

negative external effects on society. Since the credit crunch

of 2007–2008, stakeholders’ perceptions of firms’ risk and

performance have become particularly important to banks’

sustainability,since they rely on depositors and govern-

mentagenciesas key sourcesfor funding and liquidity

(Grove etal. 2011;Veronesiand Zingales 2010),and as

investors have become increasingly risk averse (Gemmill

and Keswani2011).However,there is a distinctlack of

empirical research into the relationship between corporate

governance and CSR in the banking sector. This paper fills

the gap in the literature by investigating whether corporate

governance characteristics, in particular key features of the

board of directors,impact on CSR disclosure in US com-

mercial banks’ annual reports, for the period after the credit

crunch of 2007–2008. We use banks’ annual reports, rather

than CSR or corporatesustainabilityreports,because

annual reports are the key documents scrutinised by a wide

rangeof stakeholders(e.g. Toms 2002;Campbelland

Slack 2008). Additionallydisclosureof CSR-related

information in annual reports allows boards to signal their

balance between financial and social objectives (Gray et a

1995a).Unlike previousresearch into CSR disclosure,

which relied on counting relevant words or sentences (e.g

Li et al. 2008;Kothariet al. 2009;Haniffa and Cooke

2005),we use contentanalysis to measure the compre-

hensiveness and quality of disclosed information in banks’

annual reports.The rationale for this is that the quality of

disclosure is more essentialthan the quantity (Hasseldine

et al. 2005;Toms 2002).In line with definitions,frame-

works and methods employed in the mainstream CSR lit-

erature (Gray etal. 1995a,b; Haniffa and Cooke 2005;

Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Scholtens 2008; Holder-Webb

et al.2009), we develop a CSR disclosure measure based

on the contentof four CSR categories—community

involvement,environment,employees,and productand

customer service quality—and score the contentof infor-

mation in each of the categories based on the existence a

comprehensiveness of information disclosed.

Our findings suggest that board independence and boar

size positively affectCSR disclosure by large US banks.

This indicates that, possibly due to the increasing realisati

of the long-term benefits ofCSR, corporate governance

mechanisms that were chiefly designed to protect minorit

shareholderinterestsmightalso encouragemanagerial

stewardship for the benefitof all stakeholders.However,

contrary to our expectations, Chief Executive Officer (CEO

duality,also,appears to be positively related to CSR dis-

closure.We are unable to identify whetherstakeholders

benefit from the ability of powerful CEOs to pursue private

interests by engaging in CSR activities and CSR reporting,

or whether the market pressures and public scrutiny force

powerful CEOs to engage in CSR disclosure as a means of

allaying fears that they might exploit their position.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows.The

next section providesa discussion ofthe relationship

between corporate governance and CSR disclosure. This is

followed by the hypotheses development.Afterwards,we

discussour research design,in termsof sampledata,

measurement of variables and the model, before we prese

the results and their analysis. The conclusion is given in th

final section.

Corporate Governance and CSR

According to the World Bank, ‘CSR is the commitment of

businesses to contribute to sustainable economic develop

ment by working with employees,their families,the local

community and society atlarge to improve their lives in

waysthatare good forbusinessand for development’

(Starks 2009,p. 465).

CSR can have both financialand strategic advantages

for firms. By engaging in social activities and reporting on

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

directors are therefore expected to promote CSR reporting

(Jamali et al.2008).

Given the potentialimpactof CSR reporting on firms’

sustainability,there is a surprising dearth of research into

the impactof corporate governance on CSR disclosure.

Existing research mainly concentrates on the influence of

CSR committees on CSR disclosure (Gill2008;Spitzeck

2009;Li et al. 2010;Kolk and Pinkse 2010) and largely

neglects investigating whetherkey characteristics ofthe

board of directors impact on the reporting of CSR-related

issues.As the board ofdirectorsis responsible forthe

developmentof sustainablebusinessstrategiesand the

supervision of the responsible use of the firms’ assets, it is

the board which takes the crucial decisions in relation to a

firm’s CSR policies. If firms engage in CSR activities and

reporting notmerely asa temporary fad orto appease

managers’personalmoralconcerns(Porterand Kramer

2006; Hennigfeld et al. 2006), but to acknowledge societal

concernsand maintain positiverelationshipswith key

stakeholders in order to improve the sustainability of the

business,one would expect that firms with more effective

boards structures will be particularly diligent in providing

information on CSR-related issues.Accordingly,and in

light of increasing public, customer and investor pressures,

corporate governance features,such as board characteris-

tics, which were originally designed mainly to protect

shareholder interests (Fama 1980; Hermalin and Weisbach

1998, 2003), might be effective in encouraging managerial

stewardship for the benefit of a wide range of stakeholders.

Understanding the link between corporate governance,

in particularboard characteristics,and CSR reporting is

importantfor banks,because of their potentialsignificant

negative external effects on society. Since the credit crunch

of 2007–2008, stakeholders’ perceptions of firms’ risk and

performance have become particularly important to banks’

sustainability,since they rely on depositors and govern-

mentagenciesas key sourcesfor funding and liquidity

(Grove etal. 2011;Veronesiand Zingales 2010),and as

investors have become increasingly risk averse (Gemmill

and Keswani2011).However,there is a distinctlack of

empirical research into the relationship between corporate

governance and CSR in the banking sector. This paper fills

the gap in the literature by investigating whether corporate

governance characteristics, in particular key features of the

board of directors,impact on CSR disclosure in US com-

mercial banks’ annual reports, for the period after the credit

crunch of 2007–2008. We use banks’ annual reports, rather

than CSR or corporatesustainabilityreports,because

annual reports are the key documents scrutinised by a wide

rangeof stakeholders(e.g. Toms 2002;Campbelland

Slack 2008). Additionallydisclosureof CSR-related

information in annual reports allows boards to signal their

balance between financial and social objectives (Gray et a

1995a).Unlike previousresearch into CSR disclosure,

which relied on counting relevant words or sentences (e.g

Li et al. 2008;Kothariet al. 2009;Haniffa and Cooke

2005),we use contentanalysis to measure the compre-

hensiveness and quality of disclosed information in banks’

annual reports.The rationale for this is that the quality of

disclosure is more essentialthan the quantity (Hasseldine

et al. 2005;Toms 2002).In line with definitions,frame-

works and methods employed in the mainstream CSR lit-

erature (Gray etal. 1995a,b; Haniffa and Cooke 2005;

Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Scholtens 2008; Holder-Webb

et al.2009), we develop a CSR disclosure measure based

on the contentof four CSR categories—community

involvement,environment,employees,and productand

customer service quality—and score the contentof infor-

mation in each of the categories based on the existence a

comprehensiveness of information disclosed.

Our findings suggest that board independence and boar

size positively affectCSR disclosure by large US banks.

This indicates that, possibly due to the increasing realisati

of the long-term benefits ofCSR, corporate governance

mechanisms that were chiefly designed to protect minorit

shareholderinterestsmightalso encouragemanagerial

stewardship for the benefitof all stakeholders.However,

contrary to our expectations, Chief Executive Officer (CEO

duality,also,appears to be positively related to CSR dis-

closure.We are unable to identify whetherstakeholders

benefit from the ability of powerful CEOs to pursue private

interests by engaging in CSR activities and CSR reporting,

or whether the market pressures and public scrutiny force

powerful CEOs to engage in CSR disclosure as a means of

allaying fears that they might exploit their position.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows.The

next section providesa discussion ofthe relationship

between corporate governance and CSR disclosure. This is

followed by the hypotheses development.Afterwards,we

discussour research design,in termsof sampledata,

measurement of variables and the model, before we prese

the results and their analysis. The conclusion is given in th

final section.

Corporate Governance and CSR

According to the World Bank, ‘CSR is the commitment of

businesses to contribute to sustainable economic develop

ment by working with employees,their families,the local

community and society atlarge to improve their lives in

waysthatare good forbusinessand for development’

(Starks 2009,p. 465).

CSR can have both financialand strategic advantages

for firms. By engaging in social activities and reporting on

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

CSR, firms develop the trust and goodwill of stakeholders,

which can providethem withcompetitiveadvantages

(Aguilera etal. 2006;Money and Schepers2007;Gill

2008; Kolk and Pinkse 2010). Research suggests that CSR

reporting promotes firms’ image and enhances their repu-

tation, (Gray et al. 1995b; Li et al. 2010; Vanhamme et al.

2012)as relationships with stakeholders are based on a

positive exchange of benefits (Bear etal. 2010).Socially

responsible firms tend to experience greater brand loyalty

(Mackenzie2007),customersatisfaction and employee

commitment (Matten 2006). CSR engagement also reduces

the risk thatfirms’ performance is negatively affected by

labourdisputes,productsafety scandalsand consumer

fraud (Waddock and Graves1997).Accordingly,firms

which are perceived to have high CSR standards are sub-

jectto lowerfirm specific risks due to lowercash flow

variability (Salama et al.2011).

As CSR engagement and CSR reporting can impact on

firms’risks and profitability,investors increasingly con-

sider firms’ social behaviour in their investment decisions

(Simpson and Kohers 2002;Aguilera etal. 2006;Matten

2006).Research by Ghoul et al.(2011) on US firms indi-

cates that investment in employee relations, environmental

policiesand CSR productstrategieshelpslowerfirms’

costs of capital.Investors,therefore,increasingly require

boards and managers to engage in CSR and report on this

engagement (Scholtens 2008; Kolk and Pinkse 2010).

However,firms’ engagementin CSR is notmerely of

interestto long-term profitmaximisingshareholders.

Firms’ dependenceon otherstakeholdersand on the

frameworks and resources provided by civil society means

that there is a reciprocal expectation that firms ‘balance the

multiplicity of stakeholder interests’ and ‘are responsible to

society asa whole’ (van Marrewijk 2003,pp. 96–97).

Expectationsabout firms’ social responsibilitiesare,

therefore,affected by their potential impact on stakehold-

ers and civic society.This is one of the reasonswhy

industries,which can impose significantnegative external

effects on society, such as the financial service sector, tend

to be comparatively tightly regulated and scrutinised.The

huge negative external effects failing banks in the US and

Europe recently imposed on society are the driving force

behind attempts by national and international regulators to

improvebanking standardsand explain why theCSR

activitiesof bankshavecomeunderincreased public

scrutiny (Grove et al.2011).

While governments have the responsibility to set regu-

latory frameworks for the operation of firms at national and

internationallevel,it is the board ofdirectors,which is

ultimately responsible for the developmentof sustainable

business strategies and the oversightof managers’ use of

the firms’ resources (OECD 1999). Both at national and at

firm-level,‘good corporate governance’is expected ‘to

ensure that corporations take into account the interests of

wide range of constituencies, as well as of the communitie

within which they operate,and that their boardsare

accountable to the company and the shareholders’ (OECD

1999, p. 5). However, with regard to firms’ engagement in

CSR, there is so farlittle research into whether‘good’

corporate governance at board level has any impact (e.g.

and Harjoto 2011). This is of particular concern, given the

potentialconflictsof interestamong shareholders,other

stakeholders and the public atlarge.As mostfirm-level

corporate governance mechanisms were originally devel-

oped to protect shareholder interests (Fama 1980),it is by

no meansa foregone conclusion that‘good’ corporate

governanceis also beneficialto the interestsof other

stakeholders and civic society.

Hypotheses Development

In situations where goods,labour and capitalmarkets are

not perfectly competitive,agency theory suggeststhat

managers might be able and willing to abuse their power t

exploit the firms’ shareholders as well as other stakeholde

(Hermalin and Weisbach 1998; Haniffa and Cooke 2002).

In such circumstances, when external corporate governan

fails, internalcorporate governance mechanisms,in par-

ticular boards of directors, are expected to play a key role

in supervising managersand holding them to account

(Fama 1980; Hermalin and Weisbach 2003; Li et al. 2008;

Guest2009).While directors in non-financialcompanies

are usually expected to oversee managers predominantly

the interestof shareholders,financialservices regulation

extendsthe fiduciarydutiesof directorsof banksto

depositorsand regulators(Pathanand Skully 2010),

although the election of the directors remains the purview

of shareholders.

The way that boards discharge their duty of supervision

and control depends not only on their fiduciary duties,but

also on their membership and organisation.For example,

Pathan’s (2009) research on large US bank holding com-

panies indicates that between 1997 and 2004,CEO power

and board structure were related to banks’ risk taking. The

findings do not only show that board characteristics,such

as board independence and CEO duality,can impacton

firm behaviour;butthey also demonstrate the importance

of differencesin stakeholderinterests.The pre-credit

crunch study indicates thatstrong,independentboards of

directors successfully put pressure on banks’ managemen

to increase risk taking for the short-term benefit of share-

holders and the detrimentof depositors,bondholders and

risk-averse CEOs.By contrast,banks with strong CEOs

tended to have a lower risk profile, as managers were able

to accommodatetheir personalinclinationfor risk-

Evidence from the US Banking Sector

123

which can providethem withcompetitiveadvantages

(Aguilera etal. 2006;Money and Schepers2007;Gill

2008; Kolk and Pinkse 2010). Research suggests that CSR

reporting promotes firms’ image and enhances their repu-

tation, (Gray et al. 1995b; Li et al. 2010; Vanhamme et al.

2012)as relationships with stakeholders are based on a

positive exchange of benefits (Bear etal. 2010).Socially

responsible firms tend to experience greater brand loyalty

(Mackenzie2007),customersatisfaction and employee

commitment (Matten 2006). CSR engagement also reduces

the risk thatfirms’ performance is negatively affected by

labourdisputes,productsafety scandalsand consumer

fraud (Waddock and Graves1997).Accordingly,firms

which are perceived to have high CSR standards are sub-

jectto lowerfirm specific risks due to lowercash flow

variability (Salama et al.2011).

As CSR engagement and CSR reporting can impact on

firms’risks and profitability,investors increasingly con-

sider firms’ social behaviour in their investment decisions

(Simpson and Kohers 2002;Aguilera etal. 2006;Matten

2006).Research by Ghoul et al.(2011) on US firms indi-

cates that investment in employee relations, environmental

policiesand CSR productstrategieshelpslowerfirms’

costs of capital.Investors,therefore,increasingly require

boards and managers to engage in CSR and report on this

engagement (Scholtens 2008; Kolk and Pinkse 2010).

However,firms’ engagementin CSR is notmerely of

interestto long-term profitmaximisingshareholders.

Firms’ dependenceon otherstakeholdersand on the

frameworks and resources provided by civil society means

that there is a reciprocal expectation that firms ‘balance the

multiplicity of stakeholder interests’ and ‘are responsible to

society asa whole’ (van Marrewijk 2003,pp. 96–97).

Expectationsabout firms’ social responsibilitiesare,

therefore,affected by their potential impact on stakehold-

ers and civic society.This is one of the reasonswhy

industries,which can impose significantnegative external

effects on society, such as the financial service sector, tend

to be comparatively tightly regulated and scrutinised.The

huge negative external effects failing banks in the US and

Europe recently imposed on society are the driving force

behind attempts by national and international regulators to

improvebanking standardsand explain why theCSR

activitiesof bankshavecomeunderincreased public

scrutiny (Grove et al.2011).

While governments have the responsibility to set regu-

latory frameworks for the operation of firms at national and

internationallevel,it is the board ofdirectors,which is

ultimately responsible for the developmentof sustainable

business strategies and the oversightof managers’ use of

the firms’ resources (OECD 1999). Both at national and at

firm-level,‘good corporate governance’is expected ‘to

ensure that corporations take into account the interests of

wide range of constituencies, as well as of the communitie

within which they operate,and that their boardsare

accountable to the company and the shareholders’ (OECD

1999, p. 5). However, with regard to firms’ engagement in

CSR, there is so farlittle research into whether‘good’

corporate governance at board level has any impact (e.g.

and Harjoto 2011). This is of particular concern, given the

potentialconflictsof interestamong shareholders,other

stakeholders and the public atlarge.As mostfirm-level

corporate governance mechanisms were originally devel-

oped to protect shareholder interests (Fama 1980),it is by

no meansa foregone conclusion that‘good’ corporate

governanceis also beneficialto the interestsof other

stakeholders and civic society.

Hypotheses Development

In situations where goods,labour and capitalmarkets are

not perfectly competitive,agency theory suggeststhat

managers might be able and willing to abuse their power t

exploit the firms’ shareholders as well as other stakeholde

(Hermalin and Weisbach 1998; Haniffa and Cooke 2002).

In such circumstances, when external corporate governan

fails, internalcorporate governance mechanisms,in par-

ticular boards of directors, are expected to play a key role

in supervising managersand holding them to account

(Fama 1980; Hermalin and Weisbach 2003; Li et al. 2008;

Guest2009).While directors in non-financialcompanies

are usually expected to oversee managers predominantly

the interestof shareholders,financialservices regulation

extendsthe fiduciarydutiesof directorsof banksto

depositorsand regulators(Pathanand Skully 2010),

although the election of the directors remains the purview

of shareholders.

The way that boards discharge their duty of supervision

and control depends not only on their fiduciary duties,but

also on their membership and organisation.For example,

Pathan’s (2009) research on large US bank holding com-

panies indicates that between 1997 and 2004,CEO power

and board structure were related to banks’ risk taking. The

findings do not only show that board characteristics,such

as board independence and CEO duality,can impacton

firm behaviour;butthey also demonstrate the importance

of differencesin stakeholderinterests.The pre-credit

crunch study indicates thatstrong,independentboards of

directors successfully put pressure on banks’ managemen

to increase risk taking for the short-term benefit of share-

holders and the detrimentof depositors,bondholders and

risk-averse CEOs.By contrast,banks with strong CEOs

tended to have a lower risk profile, as managers were able

to accommodatetheir personalinclinationfor risk-

Evidence from the US Banking Sector

123

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

aversion,which incidentally also benefitted otherstake-

holders such as depositors and bondholders.

In the context of CSR disclosure, differences in interests

of managers,shareholders and other stakeholders are also

likely to play a role in how corporate governance structures

affect firm behaviour.However,in this case,as discussed

earlier, it appears that shareholders’ and other stakeholders’

interests might be more closely aligned.

Board Independence

From an agency theoreticalperspective,boardswith a

high proportion of independentdirectors are presumed to

be moreeffectivein monitoring and controlling man-

agement.They are, therefore,expectedto be more

successfulin directing managementtowardslong-term

firm valueenhancing activitiesand a high degreeof

transparency.Independentdirectorsare supposed to be

able to assess managementperformance more objectively

than executivedirectors,as they are less closely

involvedin the developmentof firm strategiesand

businesspolicies.In addition,independentdirectorsare

less dependenton the CEO’s goodwillthan executive

directorsand affiliatednon-executivedirectorswith

business links to the firm.Therefore,a higher proportion

of independentdirectors on the board is expected to lead

to bettermonitoring and controlof management(John

and Senbet1998; Ahmed et al. 2006; Cheng and

Courtenay 2006).

Moreover,independentnon-executive directors’ remu-

neration is not tied to the firm’s financial performance and

growth,unlike the remuneration of top executives and the

businessprospectsof affiliated non-executive directors.

Consequently, independent directors are expected to be less

focussed on short-term financialperformance targets and

more interested in measures which enhance firms’long-

term sustainability,such as engaging in and reporting on

CSR (Ibrahim et al. 2003). Banks with independent boards

are, therefore, expected to display a greater engagement in

CSR and CSR reporting (Jamaliet al. 2008;Arora and

Dharwadkar 2011).

Indeed,empiricalresearch suggeststhatindependent

directors are more supportive of firms’ investment in CSR

activities(Johnson and Greening 1999)and pay more

attention to the perception of the firm’s social impact than

executive or affiliated non-executive directors.Moreover,

prior studies indicate thatboards of directors with a high

proportion ofindependentdirectorstend to facilitate a

comparatively high degree of transparency and voluntary

disclosure (Cheng and Courtenay 2006;Patelliand Pren-

cipe 2007;Donnelly and Mulcahy 2008;Li et al. 2008;

Chau and Gray 2010).This suggeststhatindependent

directorsare likely to supportthe disclosureof CSR

activitiesto reduceinformationasymmetrybetween

insiders and outsiders.This leads to our first hypothesis.

H1 A higher degree of board independence is positively

related to CSR disclosure.

Board Size

Considering group dynamics,smallerboardsare often

expected to be more effective at monitoring and controllin

management than larger boards.Due to their limited size,

they are expected to benefitfrom more efficientcommu-

nication and coordination,as well as higherlevelsof

commitment and accountability of individual board mem-

bers (Ahmed et al.2006; Dey 2008).

However,the drawback ofsmallboardsis thatthe

workload of individualmembers tends to be high,which

mightlimitthe monitoring ability of the board (John and

Senbet 1998). Moreover, smaller boards can draw on a les

diversified range of expertise than larger boards, which ca

impact on the quality of the advice and monitoring offered

(Guest 2009).

Empiricalresearch suggeststhatboard size isdeter-

mined by a variety of factors including industry,firm size

and the complexity of the firm’s business (Krishnan and

Visvanathan 2009;Pathan 2009).As commercialbanks

are complex organisations that are subject to wide-rangin

regulation (Grove etal. 2011),we expectthatin this

context,workload considerationsare of ultimate impor-

tance.Hence,we expectthatlarger boards willbe better

able to directmanagementto engage in CSR activities

and to effectively communicate theirsocialperformance

to the bank’sstakeholders.This leadsto our second

hypothesis.

H2 Board size is positively related to CSR disclosure.

CEO Duality

Agency theory suggeststhatmanagers’private interests

are likely to impact on the degree to which they engage in

CSR activities and CSR disclosure.In this context,CEO

duality can be seen both as a sign and an instrumentof

managerialpower.CEOs are more likely to be appointed

as chairs ofthe boards ofdirectors ifthey have a suc-

cessfultrack record or if they controla large proportion

of the firm’s shares(Hermalinand Weisbach1998).

Moreover,as chairs of boards of directors have the ability

to setthe board’s agenda and influence the information

provided to the other board members,CEOs who also act

as chairs can hide crucialinformation more easily from

other,in particularnon-executive,directors (Haniffa and

Cooke 2002;Li et al. 2008;Krishnan and Visvanathan

2009).Being chairmightalso enable CEOs to influence

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

holders such as depositors and bondholders.

In the context of CSR disclosure, differences in interests

of managers,shareholders and other stakeholders are also

likely to play a role in how corporate governance structures

affect firm behaviour.However,in this case,as discussed

earlier, it appears that shareholders’ and other stakeholders’

interests might be more closely aligned.

Board Independence

From an agency theoreticalperspective,boardswith a

high proportion of independentdirectors are presumed to

be moreeffectivein monitoring and controlling man-

agement.They are, therefore,expectedto be more

successfulin directing managementtowardslong-term

firm valueenhancing activitiesand a high degreeof

transparency.Independentdirectorsare supposed to be

able to assess managementperformance more objectively

than executivedirectors,as they are less closely

involvedin the developmentof firm strategiesand

businesspolicies.In addition,independentdirectorsare

less dependenton the CEO’s goodwillthan executive

directorsand affiliatednon-executivedirectorswith

business links to the firm.Therefore,a higher proportion

of independentdirectors on the board is expected to lead

to bettermonitoring and controlof management(John

and Senbet1998; Ahmed et al. 2006; Cheng and

Courtenay 2006).

Moreover,independentnon-executive directors’ remu-

neration is not tied to the firm’s financial performance and

growth,unlike the remuneration of top executives and the

businessprospectsof affiliated non-executive directors.

Consequently, independent directors are expected to be less

focussed on short-term financialperformance targets and

more interested in measures which enhance firms’long-

term sustainability,such as engaging in and reporting on

CSR (Ibrahim et al. 2003). Banks with independent boards

are, therefore, expected to display a greater engagement in

CSR and CSR reporting (Jamaliet al. 2008;Arora and

Dharwadkar 2011).

Indeed,empiricalresearch suggeststhatindependent

directors are more supportive of firms’ investment in CSR

activities(Johnson and Greening 1999)and pay more

attention to the perception of the firm’s social impact than

executive or affiliated non-executive directors.Moreover,

prior studies indicate thatboards of directors with a high

proportion ofindependentdirectorstend to facilitate a

comparatively high degree of transparency and voluntary

disclosure (Cheng and Courtenay 2006;Patelliand Pren-

cipe 2007;Donnelly and Mulcahy 2008;Li et al. 2008;

Chau and Gray 2010).This suggeststhatindependent

directorsare likely to supportthe disclosureof CSR

activitiesto reduceinformationasymmetrybetween

insiders and outsiders.This leads to our first hypothesis.

H1 A higher degree of board independence is positively

related to CSR disclosure.

Board Size

Considering group dynamics,smallerboardsare often

expected to be more effective at monitoring and controllin

management than larger boards.Due to their limited size,

they are expected to benefitfrom more efficientcommu-

nication and coordination,as well as higherlevelsof

commitment and accountability of individual board mem-

bers (Ahmed et al.2006; Dey 2008).

However,the drawback ofsmallboardsis thatthe

workload of individualmembers tends to be high,which

mightlimitthe monitoring ability of the board (John and

Senbet 1998). Moreover, smaller boards can draw on a les

diversified range of expertise than larger boards, which ca

impact on the quality of the advice and monitoring offered

(Guest 2009).

Empiricalresearch suggeststhatboard size isdeter-

mined by a variety of factors including industry,firm size

and the complexity of the firm’s business (Krishnan and

Visvanathan 2009;Pathan 2009).As commercialbanks

are complex organisations that are subject to wide-rangin

regulation (Grove etal. 2011),we expectthatin this

context,workload considerationsare of ultimate impor-

tance.Hence,we expectthatlarger boards willbe better

able to directmanagementto engage in CSR activities

and to effectively communicate theirsocialperformance

to the bank’sstakeholders.This leadsto our second

hypothesis.

H2 Board size is positively related to CSR disclosure.

CEO Duality

Agency theory suggeststhatmanagers’private interests

are likely to impact on the degree to which they engage in

CSR activities and CSR disclosure.In this context,CEO

duality can be seen both as a sign and an instrumentof

managerialpower.CEOs are more likely to be appointed

as chairs ofthe boards ofdirectors ifthey have a suc-

cessfultrack record or if they controla large proportion

of the firm’s shares(Hermalinand Weisbach1998).

Moreover,as chairs of boards of directors have the ability

to setthe board’s agenda and influence the information

provided to the other board members,CEOs who also act

as chairs can hide crucialinformation more easily from

other,in particularnon-executive,directors (Haniffa and

Cooke 2002;Li et al. 2008;Krishnan and Visvanathan

2009).Being chairmightalso enable CEOs to influence

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

board appointments in theirfavour(Haniffa and Cooke

2002).Therefore,non-executive directors mightbe more

likely to acceptmanagerialdecisions againsttheirbetter

judgement,because they try to avoid confrontations with

powerful CEOs,for example,to retain their places on the

board (Dey 2008). Empirical research suggests that boards

of directors’attentionto monitoringare negatively

affected by CEO duality (Tuggle etal. 2010),as is the

level of voluntarydisclosure(Donnellyand Mulcahy

2008;Chau and Gray 2010).

As previously discussed,while it is often assumed

thatbank CEOs are less risk happy than their diversified

shareholders,changesin banks’executive remuneration

mighthave changed this.Empiricalstudies suggestthat

executive remuneration in US holding banks has become

increasingly risk sensitive,which hasencouraged man-

agersto take more risks in orderto maximisetheir

short-term pay.Research by Baiand Elyasiani(2013)

shows thatbetween 1992 and 2008,the risk sensitivity

of CEO pay in US bank holding companiesincreased

significantly,and thatthis is related to an increase in

bank risk.Similarly,research by Hagendorffand Va-

llascas (2011)finds thatbetween 1993 and 2007,CEOs

of US banksincreasinglyengagedin risky business

transactions,as the proportion ofequity-based pay in

their performancecontractsrose. This suggeststhat

managers’ typicalinclination to limittheirrisk exposure

to protecttheirhuman capitalhas been eroded by the

structureof their executivepay packages.As CSR

engagementand disclosuretend to reducefirms’ risk

profiles(Simpsonand Kohers 2002;Scholtens2008;

Salamaet al. 2011;Ghoul et al. 2011),CEOs might

view CSR reporting asdetrimentalto maximising their

remuneration.

Moreover,if powerfulCEOs are able to use CSR to

furthertheirown interests and moralconvictions,rather

than the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders;

they are likely to be reluctantto provide comprehensive,

high quality disclosure of CSR activities.Since the provi-

sion of information increases the effectiveness of external

controlnotonly by informed investors,financialanalysts

and the business press (Healy and Palepu 2001;Li et al.

2008;Beyeret al. 2010),but also by otherkey stake-

holders, and the public, powerful CEOs are expected to use

theirinfluence to curtailvoluntary disclosure,including

CSR disclosure.

Given the developmentof executive remuneration in

banks during the last 15 years and the ability of CEOs, who

also actas chairs of the boards of directors,to influence

board behaviour,we expect that:

H3 CEO duality is negatively related to CSR disclosure.

Research Design

Sample

The paper seeks to investigate whether CSR reporting in

annualreports of US listed nationalcommercialbanks is

related to the firms’ corporate governance in the wake of

the financialcrisis of 2007–2008.We,therefore,examine

the CSR disclosuresin US nationalcommercialbanks’

annualreports from 2009 to 2011.In orderto focus on

financial institutions which provide similar services and are

subjectto the same regulationsand disclosure require-

ments,we exclude creditunions,saving institutions and

centralreserve depositories from our considerations.This

leaves us with a sample of193 banks with totalassets

varying from $48 million to $2223 billion.To ensure that

banks have a similar level of regulatory scrutiny and publi

visibility,we furtherrefine oursample by excluding all

banks which recorded less than $1 billion in total assets in

2009.The initial sample selected according to the defined

criteria consisted of107 US listed nationalcommercial

banks per-year.

The CSR data were collected from banks’ 2009,2010

and 2011 annualreports.The data on board composition

and activity were also collected from the banks’annual

reports, as well as related proxy statements. Financial dat

were collected from the Thomson One Banker database

and,if necessary,from the banks’ 10-K forms and web-

sites. If one or more of the variables were not found in the

mentioneddata sources,the correspondingbank was

omitted from the sample. This left us with 98 observations

for 2009, 97 observations for 2010 and 96 observations fo

2011.

Measuring CSR Disclosure

In line with previous research,this paper focuses on self-

reported information on CSR provided by the firms in their

annualreports (Gray etal. 1995b).The information con-

tained in the annual report is under much more control of

the CEO and the board of directors, than information by th

press or interest groups which many CSR ratings agencies

rely on (Johnson and Greening 1999;Barnea and Rubin

2010;Bear et al. 2010;Jo and Harjoto 2011).This is

importantgiven ourresearch questions.Moreover,com-

pared with specialised CSR reports, annual reports tend to

have a much wider readership among shareholders,stake-

holders and information intermediaries,such as financial

analysts and credit rating agencies. Finally, the majority o

the content of annual reports tends to be audited,whereas

auditing ofCSR reports tends to be much more limited

Evidence from the US Banking Sector

123

2002).Therefore,non-executive directors mightbe more

likely to acceptmanagerialdecisions againsttheirbetter

judgement,because they try to avoid confrontations with

powerful CEOs,for example,to retain their places on the

board (Dey 2008). Empirical research suggests that boards

of directors’attentionto monitoringare negatively

affected by CEO duality (Tuggle etal. 2010),as is the

level of voluntarydisclosure(Donnellyand Mulcahy

2008;Chau and Gray 2010).

As previously discussed,while it is often assumed

thatbank CEOs are less risk happy than their diversified

shareholders,changesin banks’executive remuneration

mighthave changed this.Empiricalstudies suggestthat

executive remuneration in US holding banks has become

increasingly risk sensitive,which hasencouraged man-

agersto take more risks in orderto maximisetheir

short-term pay.Research by Baiand Elyasiani(2013)

shows thatbetween 1992 and 2008,the risk sensitivity

of CEO pay in US bank holding companiesincreased

significantly,and thatthis is related to an increase in

bank risk.Similarly,research by Hagendorffand Va-

llascas (2011)finds thatbetween 1993 and 2007,CEOs

of US banksincreasinglyengagedin risky business

transactions,as the proportion ofequity-based pay in

their performancecontractsrose. This suggeststhat

managers’ typicalinclination to limittheirrisk exposure

to protecttheirhuman capitalhas been eroded by the

structureof their executivepay packages.As CSR

engagementand disclosuretend to reducefirms’ risk

profiles(Simpsonand Kohers 2002;Scholtens2008;

Salamaet al. 2011;Ghoul et al. 2011),CEOs might

view CSR reporting asdetrimentalto maximising their

remuneration.

Moreover,if powerfulCEOs are able to use CSR to

furthertheirown interests and moralconvictions,rather

than the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders;

they are likely to be reluctantto provide comprehensive,

high quality disclosure of CSR activities.Since the provi-

sion of information increases the effectiveness of external

controlnotonly by informed investors,financialanalysts

and the business press (Healy and Palepu 2001;Li et al.

2008;Beyeret al. 2010),but also by otherkey stake-

holders, and the public, powerful CEOs are expected to use

theirinfluence to curtailvoluntary disclosure,including

CSR disclosure.

Given the developmentof executive remuneration in

banks during the last 15 years and the ability of CEOs, who

also actas chairs of the boards of directors,to influence

board behaviour,we expect that:

H3 CEO duality is negatively related to CSR disclosure.

Research Design

Sample

The paper seeks to investigate whether CSR reporting in

annualreports of US listed nationalcommercialbanks is

related to the firms’ corporate governance in the wake of

the financialcrisis of 2007–2008.We,therefore,examine

the CSR disclosuresin US nationalcommercialbanks’

annualreports from 2009 to 2011.In orderto focus on

financial institutions which provide similar services and are

subjectto the same regulationsand disclosure require-

ments,we exclude creditunions,saving institutions and

centralreserve depositories from our considerations.This

leaves us with a sample of193 banks with totalassets

varying from $48 million to $2223 billion.To ensure that

banks have a similar level of regulatory scrutiny and publi

visibility,we furtherrefine oursample by excluding all

banks which recorded less than $1 billion in total assets in

2009.The initial sample selected according to the defined

criteria consisted of107 US listed nationalcommercial

banks per-year.

The CSR data were collected from banks’ 2009,2010

and 2011 annualreports.The data on board composition

and activity were also collected from the banks’annual

reports, as well as related proxy statements. Financial dat

were collected from the Thomson One Banker database

and,if necessary,from the banks’ 10-K forms and web-

sites. If one or more of the variables were not found in the

mentioneddata sources,the correspondingbank was

omitted from the sample. This left us with 98 observations

for 2009, 97 observations for 2010 and 96 observations fo

2011.

Measuring CSR Disclosure

In line with previous research,this paper focuses on self-

reported information on CSR provided by the firms in their

annualreports (Gray etal. 1995b).The information con-

tained in the annual report is under much more control of

the CEO and the board of directors, than information by th

press or interest groups which many CSR ratings agencies

rely on (Johnson and Greening 1999;Barnea and Rubin

2010;Bear et al. 2010;Jo and Harjoto 2011).This is

importantgiven ourresearch questions.Moreover,com-

pared with specialised CSR reports, annual reports tend to

have a much wider readership among shareholders,stake-

holders and information intermediaries,such as financial

analysts and credit rating agencies. Finally, the majority o

the content of annual reports tends to be audited,whereas

auditing ofCSR reports tends to be much more limited

Evidence from the US Banking Sector

123

(Pflugrath etal. 2011;Perego and Kolk 2012).This sug-

gests that the CSR information provided in annual reports

has a greater reliability than that published in CSR reports.

Previous studies which aimed atevaluating CSR dis-

closure have tended to use two main approaches. The first

is to use CSR ratings provided by CSR rating agencies

(Johnson and Greening 1999; Barnea and Rubin 2010; Bear

et al.2010).We reject this option as the underlying ratio-

nale for the ratings tends notonly to remain obscure,but

also affected by information disclosed by the firm.The

second approach is to measure the disclosure content using

word or page counts (Liet al. 2008;Kothariet al. 2009;

Haniffa and Cooke 2005).However,such quantity scores

say little aboutthe quality and comprehensiveness of the

disclosure (Hasseldine etal. 2005).If, as previously dis-

cussed, CEOs might be incentivized to use CSR disclosure

to maximise media coverage, while at the same time trying

to limitstakeholderscrutiny oftheirpolicies,measuring

the quality and comprehensiveness rather than the quantity

of CSR disclosure is particularly important.

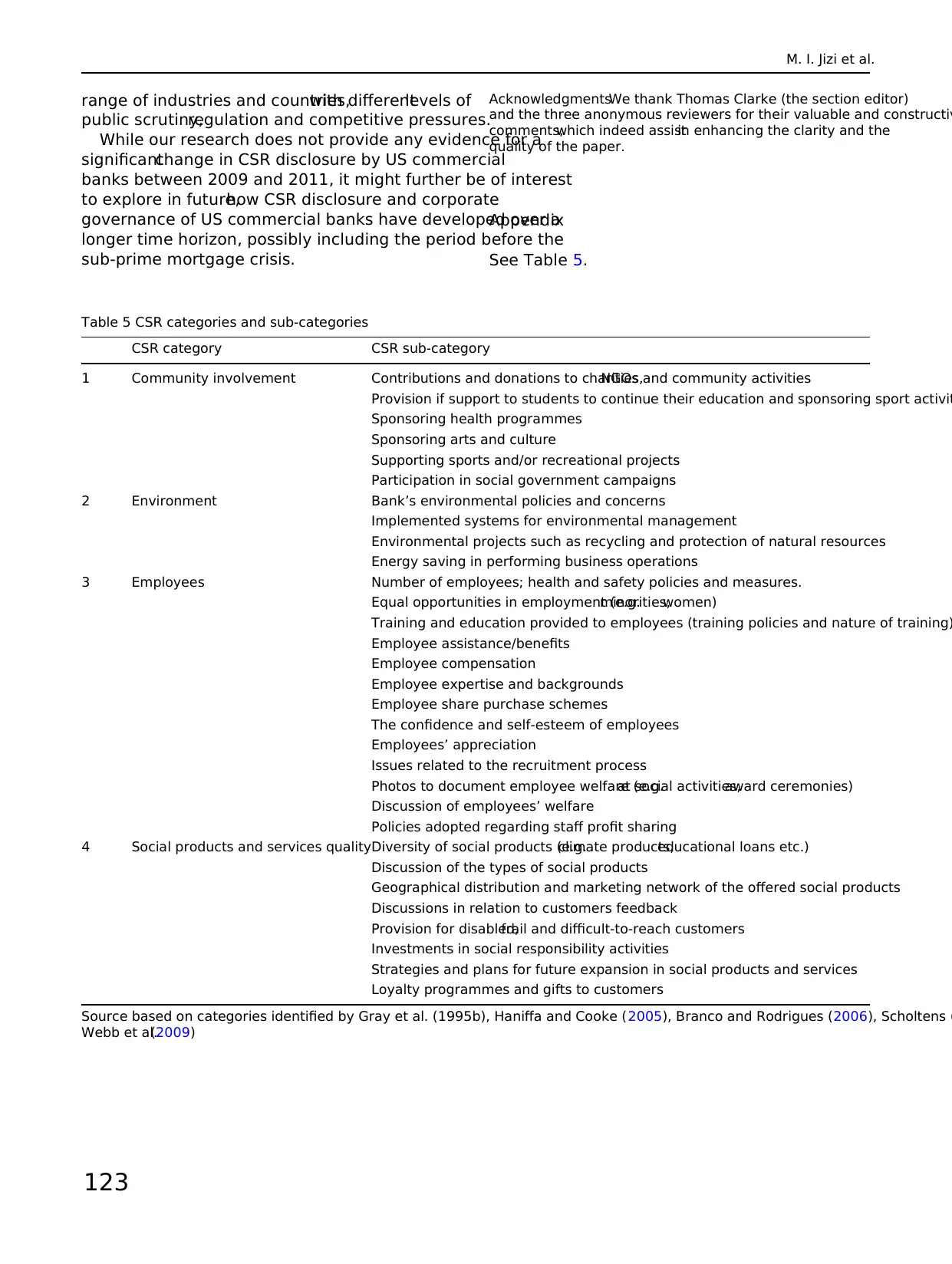

Therefore,in line with the guidance provided by Gray

et al. (1995a),we constructa CSR disclosure measure

based on the definitions,frameworksand methods

employed in the mainstream CSR literature.We examine

the contentof fourCSR categories:community involve-

ment,environment,employees,and product and customer

service quality (Gray etal. 1995b;Haniffa and Cooke

2005; Branco and Rodrigues2006; Scholtens2008;

Holder-Webb et al.2009).

The content of information on the four CSR categories is

assessed using scores based on the existence and compre-

hensiveness of information disclosed in each category (see

appendix Table 5).Each CSR category is rated from zero

to three according to the richness of information disclosed.

One additionalpointis given per category if quantitative

figures are disclosed and another point if comparative fig-

ures are disclosed.Therefore,a maximum offive points

can be assigned to each category and twenty points as a

totalscorefor CSR disclosurequality.The disclosure

measure (CSRDS) is the ratio of points awarded over the

maximum points a bank could achieve.

CSRDS ¼ X points ofcommunity;environment;ð

employees and product &

customer services categoriesÞ =20

The reliability and consistency of coding is crucial in the

application of content analysis to ensure that the assigned

scores are reproducible and reliable.Although reliability

testing cannot provide full assurance of scoring objectivity

(Linsley etal. 2006),Kripendroff’salpha iscommonly

used to assess the level of agreement between two or more

coders (Newson and Deggan 2002; Hasseldine et al. 2005;

Holder-Webb et al. 2009). Previous studies tend to sugges

that alpha valuesof 75 % or aboveare considered

generallyacceptable(Hasseldineet al. 2005;Holder-

Webb et al.2009).

To ensure the reliability of the assigned CSR disclosure

scores,a randomly selectedsampleof twenty annual

reportswas selected.The corresponding annualreports

were provided to two independent coders. The coders wer

informedaboutthe scoringprocedureand were then

required to assess the CSR contentof the annualreports

and allocate relevantscores.The scores provided by the

two independent coders along with the score computed by

one of the authors were used to testthe scoring process

reliability.The results of the testwere satisfactory as the

Krippendorff’s alpha for inter-coding agreement showed a

value of 80 %.

Control Variables

To avoid model misspecification, we control for additional

variables, which might also impact on CSR disclosure. As

CSR reporting is largely voluntary disclosure,we expect

that corporate governance structures,which impact on the

provision and quality ofvoluntary disclosure,will also

affect CSR disclosure.In this context,agency theory sug-

gests that effective audit committees are likely to improve

the reliability of corporate reporting and thereby to reduce

information asymmetry between managementand outside

investorsand otherstakeholders(McMullen 1996).The

effectiveness ofauditcommittees is likely to depend on

their size and expertise. Due to the scope and complexity

the tasks of audit committees,larger audit committees are

expected to be more effective and to put more pressure o

managers to disclose information voluntarily to increase

transparency (Li et al. 2008; Goh 2009). This is especially

relevant to banks, which conduct particularly complex and

risky business operations (Laeven and Levine 2009; Patha

2009). The literature on voluntary disclosure and disclosur

quality also suggests thatauditcommittee members with

financialexpertise tend to have a positive impacton the

extent and reliability of corporate reporting (Be´dard et al.

2004;Karamanou and Vafeas 2005;Hoitash and Hoitash

2009). Although it appears unlikely that the understanding

of audit committee members of CSR-related information is

linked to theirfinancialexpertise,we suggestthatsuch

members mighthave a more positive attitude to informa-

tion disclosure in general.

According to Lee etal. (2004),the numberof audit

committee and board meetingsmightbe a measure of

diligenceand, therefore,board and audit committee

effectiveness. With regard to corporate reporting, Kent an

Stewart’s (2008) research indicates thatthe frequency of

board and audit committee meetings is positively related

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

gests that the CSR information provided in annual reports

has a greater reliability than that published in CSR reports.

Previous studies which aimed atevaluating CSR dis-

closure have tended to use two main approaches. The first

is to use CSR ratings provided by CSR rating agencies

(Johnson and Greening 1999; Barnea and Rubin 2010; Bear

et al.2010).We reject this option as the underlying ratio-

nale for the ratings tends notonly to remain obscure,but

also affected by information disclosed by the firm.The

second approach is to measure the disclosure content using

word or page counts (Liet al. 2008;Kothariet al. 2009;

Haniffa and Cooke 2005).However,such quantity scores

say little aboutthe quality and comprehensiveness of the

disclosure (Hasseldine etal. 2005).If, as previously dis-

cussed, CEOs might be incentivized to use CSR disclosure

to maximise media coverage, while at the same time trying

to limitstakeholderscrutiny oftheirpolicies,measuring

the quality and comprehensiveness rather than the quantity

of CSR disclosure is particularly important.

Therefore,in line with the guidance provided by Gray

et al. (1995a),we constructa CSR disclosure measure

based on the definitions,frameworksand methods

employed in the mainstream CSR literature.We examine

the contentof fourCSR categories:community involve-

ment,environment,employees,and product and customer

service quality (Gray etal. 1995b;Haniffa and Cooke

2005; Branco and Rodrigues2006; Scholtens2008;

Holder-Webb et al.2009).

The content of information on the four CSR categories is

assessed using scores based on the existence and compre-

hensiveness of information disclosed in each category (see

appendix Table 5).Each CSR category is rated from zero

to three according to the richness of information disclosed.

One additionalpointis given per category if quantitative

figures are disclosed and another point if comparative fig-

ures are disclosed.Therefore,a maximum offive points

can be assigned to each category and twenty points as a

totalscorefor CSR disclosurequality.The disclosure

measure (CSRDS) is the ratio of points awarded over the

maximum points a bank could achieve.

CSRDS ¼ X points ofcommunity;environment;ð

employees and product &

customer services categoriesÞ =20

The reliability and consistency of coding is crucial in the

application of content analysis to ensure that the assigned

scores are reproducible and reliable.Although reliability

testing cannot provide full assurance of scoring objectivity

(Linsley etal. 2006),Kripendroff’salpha iscommonly

used to assess the level of agreement between two or more

coders (Newson and Deggan 2002; Hasseldine et al. 2005;

Holder-Webb et al. 2009). Previous studies tend to sugges

that alpha valuesof 75 % or aboveare considered

generallyacceptable(Hasseldineet al. 2005;Holder-

Webb et al.2009).

To ensure the reliability of the assigned CSR disclosure

scores,a randomly selectedsampleof twenty annual

reportswas selected.The corresponding annualreports

were provided to two independent coders. The coders wer

informedaboutthe scoringprocedureand were then

required to assess the CSR contentof the annualreports

and allocate relevantscores.The scores provided by the

two independent coders along with the score computed by

one of the authors were used to testthe scoring process

reliability.The results of the testwere satisfactory as the

Krippendorff’s alpha for inter-coding agreement showed a

value of 80 %.

Control Variables

To avoid model misspecification, we control for additional

variables, which might also impact on CSR disclosure. As

CSR reporting is largely voluntary disclosure,we expect

that corporate governance structures,which impact on the

provision and quality ofvoluntary disclosure,will also

affect CSR disclosure.In this context,agency theory sug-

gests that effective audit committees are likely to improve

the reliability of corporate reporting and thereby to reduce

information asymmetry between managementand outside

investorsand otherstakeholders(McMullen 1996).The

effectiveness ofauditcommittees is likely to depend on

their size and expertise. Due to the scope and complexity

the tasks of audit committees,larger audit committees are

expected to be more effective and to put more pressure o

managers to disclose information voluntarily to increase

transparency (Li et al. 2008; Goh 2009). This is especially

relevant to banks, which conduct particularly complex and

risky business operations (Laeven and Levine 2009; Patha

2009). The literature on voluntary disclosure and disclosur

quality also suggests thatauditcommittee members with

financialexpertise tend to have a positive impacton the

extent and reliability of corporate reporting (Be´dard et al.

2004;Karamanou and Vafeas 2005;Hoitash and Hoitash

2009). Although it appears unlikely that the understanding

of audit committee members of CSR-related information is

linked to theirfinancialexpertise,we suggestthatsuch

members mighthave a more positive attitude to informa-

tion disclosure in general.

According to Lee etal. (2004),the numberof audit

committee and board meetingsmightbe a measure of

diligenceand, therefore,board and audit committee

effectiveness. With regard to corporate reporting, Kent an

Stewart’s (2008) research indicates thatthe frequency of

board and audit committee meetings is positively related

M. I. Jizi et al.

123

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

voluntary disclosure. Thus, we control for board and audit

committee meeting frequency.

Managers of firms who perform wellfinancially might

have spare resources under their control, which can be used

to engage more actively in CSR and CSR reporting to

placate stakeholders orpursue managerialinterests.It is

therefore essentialto controlfor firms’financialperfor-

mance (Haniffa and Cooke 2002,2005;Lim etal. 2007;

Arora and Dharwadkar 2011).

The need ofmanagersof highly leveraged firmsto

generate and retain cash to service the debtmightreduce

their ability to fund CSR and CSR reporting (Reverte 2009;

Barnea and Rubin 2010).We therefore controlfor firm

leverage.While empirical research by Haniffa and Cooke

(2002, 2005) and Reverte (2009) has found no indication of

a relationship between leverage and CSR disclosure,Bar-

nea and Rubin’s (2010) research suggests a negative rela-

tionship between leverage and CSR disclosure.

As managers mightuse CSR disclosure to impacton

stakeholders’perceptionsof firm risk, we controlfor

banks’ systematic risks.Prior empirical research indicates

thatfirm risk tends to be positively related to CSR dis-

closure (Deegan and Gordon 1996; Jo and Harjoto 2011).

Large firms have greater impacton communities than

smallerfirms (Barnea and Rubin 2010).Consequently,

large firms tend to be more exposed to the influence of

powerful stakeholder groups representing employees,cus-

tomers, investors, public authorities, etc., are likely to face

tighter regulatory requirements,and tend to be subjectto

greater public scrutiny (Reverte 2009;Barnea and Rubin

2010). Therefore, firm size is likely to influence the amount

of CSR disclosure needed to address the concerns of var-

ious stakeholder groups (Branco and Rodrigues 2006).As

our sampleconsistsof largeUS nationalcommercial

banks,the study uses a relative rather than absolute mea-

sure to controlfor bank size (De Haan and Poghosyan

2012; Holder-Webb et al.2009).

The Model

To test the hypotheses,the Model (1.2) is set out below.

CSRDSt ¼ a þ b1BSt þ b 2BIt þ b 3DUALt þ b 4ACSt

þ b 5ACFEt þ b 6BMt þ b 7ACMt þ b 8ROAt

þ b 9Levt þ b 10SIZEt þ b 11BETAt þ e

where CSRDS CSR disclosure score measured as the ratio

of disclosure contentpoints overthe maximum score a

bank can achieve,BS board sizeas measured by the

number of board members,BI board independence mea-

sured by the number of independent directors over the total

number of board members,DUAL chair/CEO duality: 0 if

the CEO is not acting as the chair of the board of directors;

1, otherwise,ACS auditcommittee size measured by the

number of members on the auditcommittee,ACFE audit

committee financialexpertise measured by the number of

financial experts on the audit committee,BM board meet-

ings measured by the number of board meetings per year

ACM audit committee meetings measured by the number

audit committeemeetingsper year, ROA profitability

measured by netincome overtotalassets,LEV leverage

measured by totaldebtover assets,SIZE bank’ssize

measured by calculating the distance of each bank’s log

total assets from the sample mean,scaled by the log total

assets’ standard deviation,BETA Bank’s risk measured by

systematic risk,a the intercept,b1…. Bn the regression

coefficients,t period indicator,e9 the error term

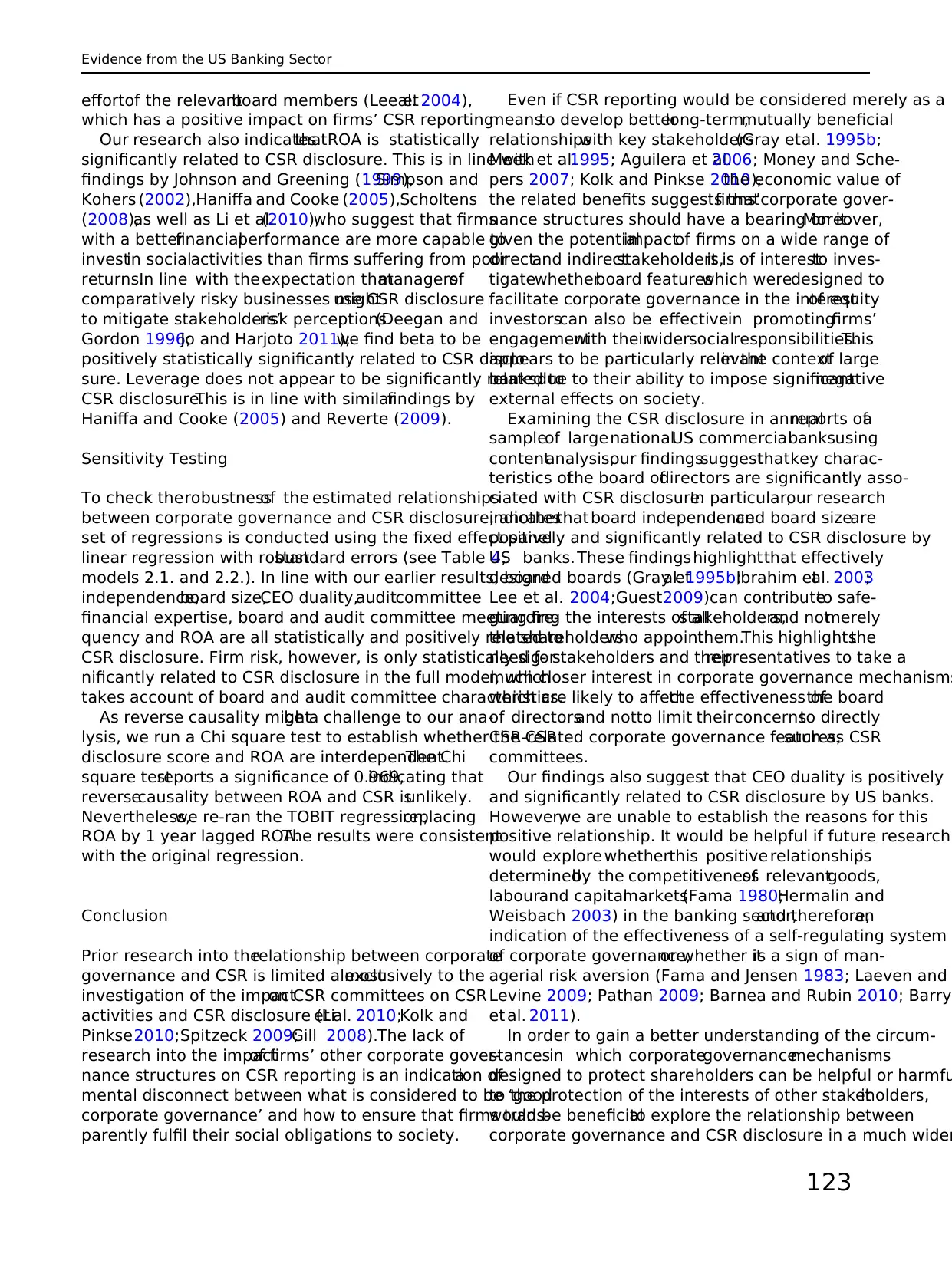

Results and Discussion

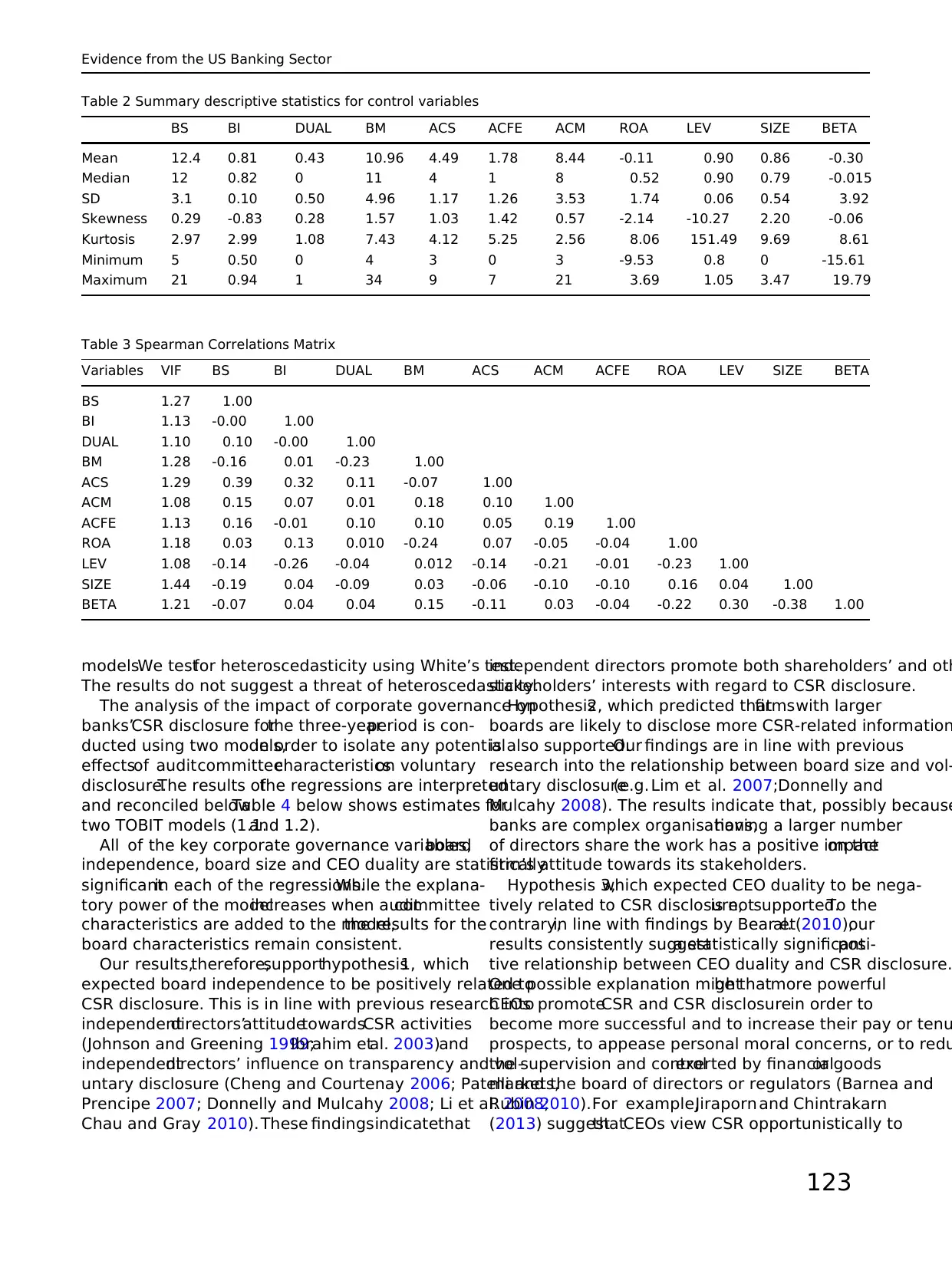

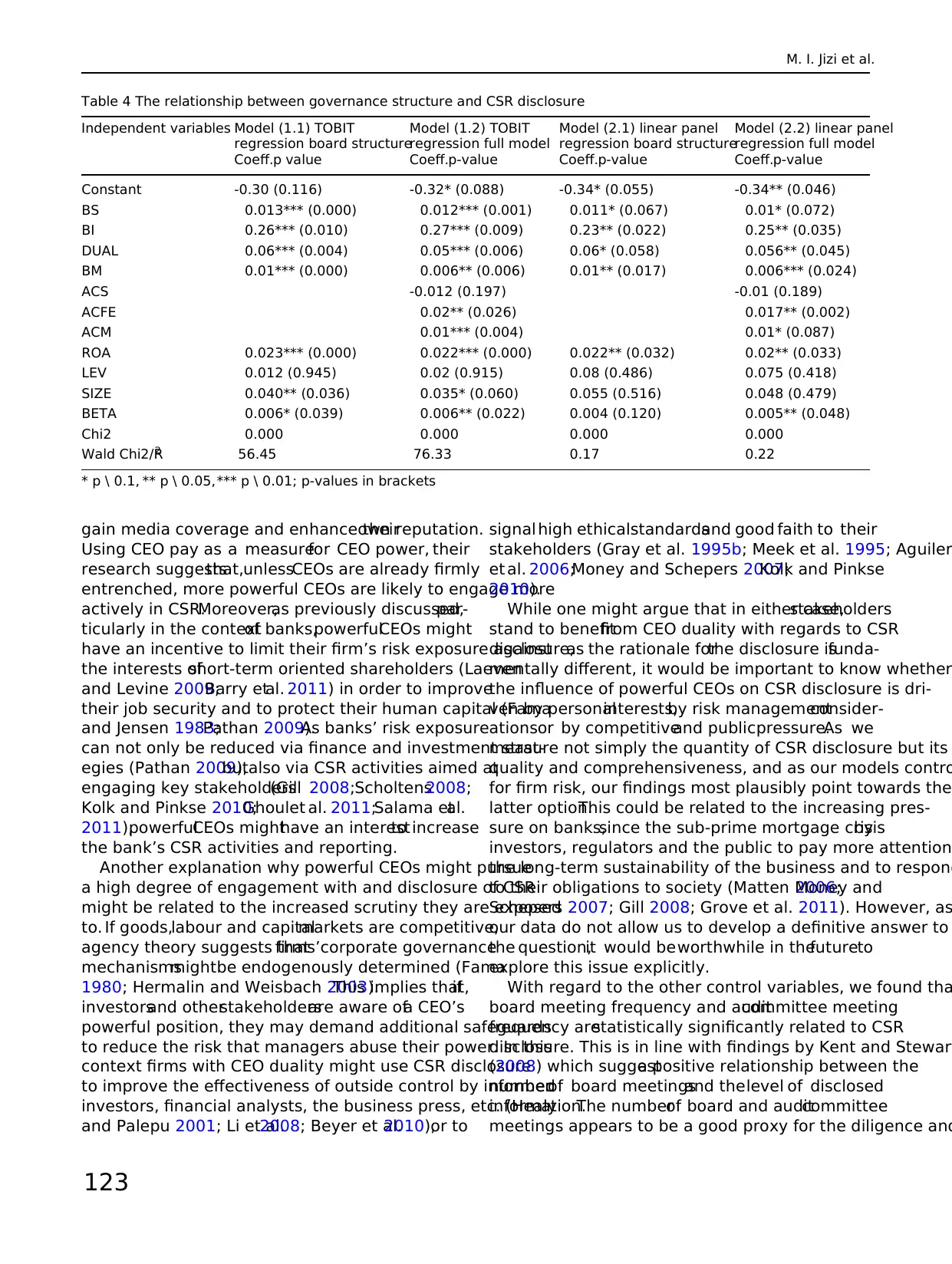

Descriptive Statistics

CSR Disclosures

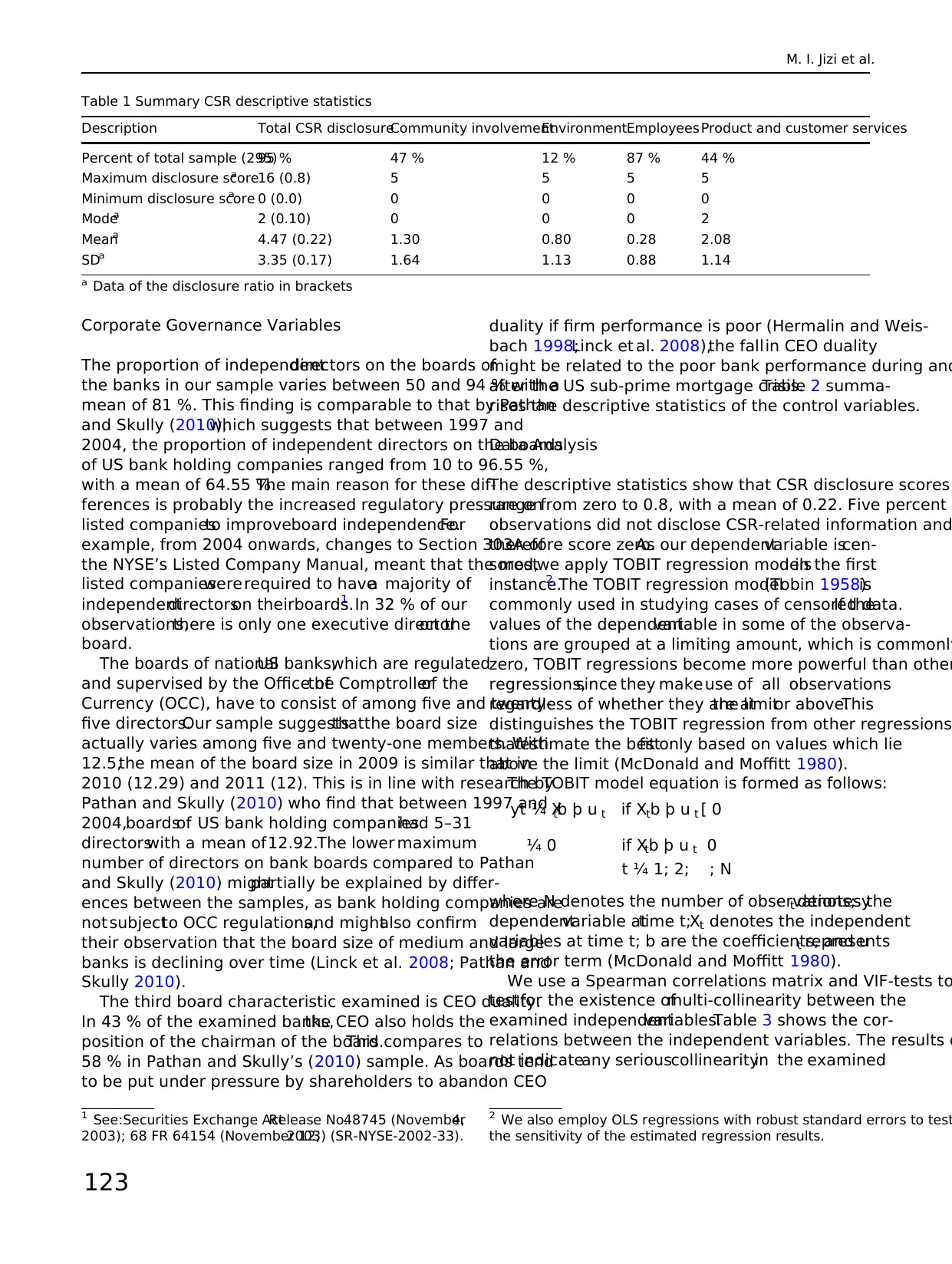

Banks disclose CSR with differentintensity and vary in

their focus among the four identified CSR categories.The

percentage ofbanksthatdisclose CSR in theirannual

reports increases from 93 % in 2009 to 97 % in 2010 and

2011.The mean of the aggregate disclosure score is 4.47

points(i.e. a ratio measure of0.22),and the standard

deviation is 3.35.The highest CSR disclosure score is 16

points out of 20 (i.e.0.8) across the four CSR categories.

The majority ofthe examined banks’annualreports

(87 %) disclosed information related to their staff.This is

in line with Branco and Rodrigues’ (2006) contention that

banksare particularly motivated to disclose CSR infor-

mation in relation to employees,since they are essential

assets for banks and impact on investors’ assessment of t

firms.

Forty-seven percent(47 %)of the examined annual

reports disclosedinformationrelated to community

involvement.A similar proportionof annualreports

(44 %)disclosed information on socialproducts,service

quality and customersatisfaction.Only twelvepercent

(12 %)of the annualreportsexamined disclosed infor-

mation related to environmentalprojects and initiatives.

Table 1 summarises the descriptive statistics for the CSR

disclosures.

Between 2009 and 2010,we found a slightincrease in

the disclosureof CSR relevantcontentin the annual

reports,as well as a rise in the number of banks that dis-

closed CSR-related information in theirannualreports.

However,both disclosure levels and the number of banks

disclosing CSR-related information remained largely the

same between 2010 and 2011.

Evidence from the US Banking Sector

123

committee meeting frequency.

Managers of firms who perform wellfinancially might

have spare resources under their control, which can be used

to engage more actively in CSR and CSR reporting to

placate stakeholders orpursue managerialinterests.It is

therefore essentialto controlfor firms’financialperfor-

mance (Haniffa and Cooke 2002,2005;Lim etal. 2007;

Arora and Dharwadkar 2011).

The need ofmanagersof highly leveraged firmsto

generate and retain cash to service the debtmightreduce

their ability to fund CSR and CSR reporting (Reverte 2009;

Barnea and Rubin 2010).We therefore controlfor firm

leverage.While empirical research by Haniffa and Cooke

(2002, 2005) and Reverte (2009) has found no indication of

a relationship between leverage and CSR disclosure,Bar-

nea and Rubin’s (2010) research suggests a negative rela-

tionship between leverage and CSR disclosure.

As managers mightuse CSR disclosure to impacton

stakeholders’perceptionsof firm risk, we controlfor

banks’ systematic risks.Prior empirical research indicates

thatfirm risk tends to be positively related to CSR dis-

closure (Deegan and Gordon 1996; Jo and Harjoto 2011).

Large firms have greater impacton communities than

smallerfirms (Barnea and Rubin 2010).Consequently,

large firms tend to be more exposed to the influence of

powerful stakeholder groups representing employees,cus-

tomers, investors, public authorities, etc., are likely to face

tighter regulatory requirements,and tend to be subjectto

greater public scrutiny (Reverte 2009;Barnea and Rubin

2010). Therefore, firm size is likely to influence the amount

of CSR disclosure needed to address the concerns of var-

ious stakeholder groups (Branco and Rodrigues 2006).As

our sampleconsistsof largeUS nationalcommercial

banks,the study uses a relative rather than absolute mea-

sure to controlfor bank size (De Haan and Poghosyan

2012; Holder-Webb et al.2009).

The Model

To test the hypotheses,the Model (1.2) is set out below.

CSRDSt ¼ a þ b1BSt þ b 2BIt þ b 3DUALt þ b 4ACSt

þ b 5ACFEt þ b 6BMt þ b 7ACMt þ b 8ROAt

þ b 9Levt þ b 10SIZEt þ b 11BETAt þ e

where CSRDS CSR disclosure score measured as the ratio

of disclosure contentpoints overthe maximum score a

bank can achieve,BS board sizeas measured by the

number of board members,BI board independence mea-

sured by the number of independent directors over the total

number of board members,DUAL chair/CEO duality: 0 if

the CEO is not acting as the chair of the board of directors;

1, otherwise,ACS auditcommittee size measured by the

number of members on the auditcommittee,ACFE audit

committee financialexpertise measured by the number of

financial experts on the audit committee,BM board meet-

ings measured by the number of board meetings per year

ACM audit committee meetings measured by the number

audit committeemeetingsper year, ROA profitability

measured by netincome overtotalassets,LEV leverage

measured by totaldebtover assets,SIZE bank’ssize

measured by calculating the distance of each bank’s log

total assets from the sample mean,scaled by the log total

assets’ standard deviation,BETA Bank’s risk measured by

systematic risk,a the intercept,b1…. Bn the regression

coefficients,t period indicator,e9 the error term

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Statistics

CSR Disclosures

Banks disclose CSR with differentintensity and vary in

their focus among the four identified CSR categories.The

percentage ofbanksthatdisclose CSR in theirannual

reports increases from 93 % in 2009 to 97 % in 2010 and

2011.The mean of the aggregate disclosure score is 4.47

points(i.e. a ratio measure of0.22),and the standard

deviation is 3.35.The highest CSR disclosure score is 16

points out of 20 (i.e.0.8) across the four CSR categories.

The majority ofthe examined banks’annualreports

(87 %) disclosed information related to their staff.This is

in line with Branco and Rodrigues’ (2006) contention that

banksare particularly motivated to disclose CSR infor-

mation in relation to employees,since they are essential

assets for banks and impact on investors’ assessment of t

firms.

Forty-seven percent(47 %)of the examined annual

reports disclosedinformationrelated to community

involvement.A similar proportionof annualreports

(44 %)disclosed information on socialproducts,service

quality and customersatisfaction.Only twelvepercent

(12 %)of the annualreportsexamined disclosed infor-

mation related to environmentalprojects and initiatives.

Table 1 summarises the descriptive statistics for the CSR

disclosures.