Japanese Linguistic Politeness

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|13

|3611

|282

AI Summary

This article discusses the determinants of linguistic politeness in Japanese, including face wants, societal position, and relationships of participants, social norms, and the immediate context of interaction. It also explores how social differences such as gender and seniority level manifest themselves in polite speech.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Japanese Linguistic Politeness

Name

Course

Word Count:

Name

Course

Word Count:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1

Japanese Linguistic Politeness

Introduction

Linguistic politeness in the Japanese language remains a hot issue since the milestone

study carried out by Brown and Levinson in the years 1978 and 1987. Politeness has been

defined as “complex system for threats’ softening by Brown and Levinson. 1 Whereas Hill et al.

1986 p. 349 described politeness in an increasingly Japanese cultural-particular sense as, “one of

the restraints on the interaction of human with the main purpose being the consideration of the

feelings of other people, establishing mutual comfort levels and rapport promotion. 2 These

authors proposed the universal politeness theory key to which is their main discussion on “face”.

3 Politeness practices in Japanese are determined by various factors. The theories of linguistic

politeness in Japanese has been re-examined in a number of studies. It is held that linguistic

politeness remains an extremely complex matter with such key determinants in different layers.

What are the key determinants of politeness practices in Japanese?

The key determinants include general face wants of subjects; societal position and

relationships of participants, social norms shared by the participants; the

discernment/interpretation of social rules by participants; interaction’s immediate context; and

feasible strategies for interactants to select under the limitations of other concurrently

1 Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. "Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena." In Questions

and politeness: Strategies in social interaction, pp. 56-311. Cambridge University Press, 1978.

2 Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A. and Ogino, T., 1986. Universals of linguistic politeness: Quantitative

evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of pragmatics, 10(3), pp.347-371.

3 Brown, Penelope, Stephen C. Levinson, and Stephen C. Levinson. Politeness: Some universals in language usage.

Vol. 4. Cambridge university press, 1987.

Japanese Linguistic Politeness

Introduction

Linguistic politeness in the Japanese language remains a hot issue since the milestone

study carried out by Brown and Levinson in the years 1978 and 1987. Politeness has been

defined as “complex system for threats’ softening by Brown and Levinson. 1 Whereas Hill et al.

1986 p. 349 described politeness in an increasingly Japanese cultural-particular sense as, “one of

the restraints on the interaction of human with the main purpose being the consideration of the

feelings of other people, establishing mutual comfort levels and rapport promotion. 2 These

authors proposed the universal politeness theory key to which is their main discussion on “face”.

3 Politeness practices in Japanese are determined by various factors. The theories of linguistic

politeness in Japanese has been re-examined in a number of studies. It is held that linguistic

politeness remains an extremely complex matter with such key determinants in different layers.

What are the key determinants of politeness practices in Japanese?

The key determinants include general face wants of subjects; societal position and

relationships of participants, social norms shared by the participants; the

discernment/interpretation of social rules by participants; interaction’s immediate context; and

feasible strategies for interactants to select under the limitations of other concurrently

1 Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. "Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena." In Questions

and politeness: Strategies in social interaction, pp. 56-311. Cambridge University Press, 1978.

2 Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A. and Ogino, T., 1986. Universals of linguistic politeness: Quantitative

evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of pragmatics, 10(3), pp.347-371.

3 Brown, Penelope, Stephen C. Levinson, and Stephen C. Levinson. Politeness: Some universals in language usage.

Vol. 4. Cambridge university press, 1987.

2

functioning factors. It has been observed that the theory of face applies to the Japanese language

and culture. Thus, this theory forms the foundation of politeness. Moreover, facework in fruitful

communication in Japanese is due to a choice by the interlocutor according to normative polite

practices.

The Japanese discernment (wakimae) and acknowledgment of social position alongside

relationship (tachiba) of the subjects form the 2nd layer of determining factors of politeness. This

makes the Japanese speakers to always attend to and attempt to fulfill the other subjects’ face

want that includes both negative and positive face, and, simultaneously, maintaining their

individual positive face but seldom claim their individual negative face specifically when the

interactant has less power alongside in a lower social position in the interaction. 4 Japanese

politeness uniqueness is that Japanese speakers seldom claim their individual negative face

particularly when the interactant has less power and in the lower social position in such an

interaction. The above-mentioned relationships are the key determinants of politeness in

Japanese within the hierarchy alongside the inside-outside system. The interactants must always

choose a correct linguistic form that correctly reflects the position of the speaker within the

systems and real communication context.

Face wants has been affirmed in the literature that just like individuals of other cultures,

speakers in Japanese have faces wants as a key determinant of politeness. Japanese speakers are

aware that they themselves alongside other interlocutors have both negative and positive face

wants. This implies that individuals often want their self-image to remain appreciated and

approved by other people in the community or society. They also need freedom from imposition.

This, therefore, make them behave suitably, both non-verbally and verbally, in accordance with

4 Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave Handbook of

Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

functioning factors. It has been observed that the theory of face applies to the Japanese language

and culture. Thus, this theory forms the foundation of politeness. Moreover, facework in fruitful

communication in Japanese is due to a choice by the interlocutor according to normative polite

practices.

The Japanese discernment (wakimae) and acknowledgment of social position alongside

relationship (tachiba) of the subjects form the 2nd layer of determining factors of politeness. This

makes the Japanese speakers to always attend to and attempt to fulfill the other subjects’ face

want that includes both negative and positive face, and, simultaneously, maintaining their

individual positive face but seldom claim their individual negative face specifically when the

interactant has less power alongside in a lower social position in the interaction. 4 Japanese

politeness uniqueness is that Japanese speakers seldom claim their individual negative face

particularly when the interactant has less power and in the lower social position in such an

interaction. The above-mentioned relationships are the key determinants of politeness in

Japanese within the hierarchy alongside the inside-outside system. The interactants must always

choose a correct linguistic form that correctly reflects the position of the speaker within the

systems and real communication context.

Face wants has been affirmed in the literature that just like individuals of other cultures,

speakers in Japanese have faces wants as a key determinant of politeness. Japanese speakers are

aware that they themselves alongside other interlocutors have both negative and positive face

wants. This implies that individuals often want their self-image to remain appreciated and

approved by other people in the community or society. They also need freedom from imposition.

This, therefore, make them behave suitably, both non-verbally and verbally, in accordance with

4 Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave Handbook of

Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

3

their discernment (wakimae) in comprehending the social place alongside relationship within

social norm (tachiba). The chosen utterances thus reflect their relationships alongside the context

of a given interaction. 5

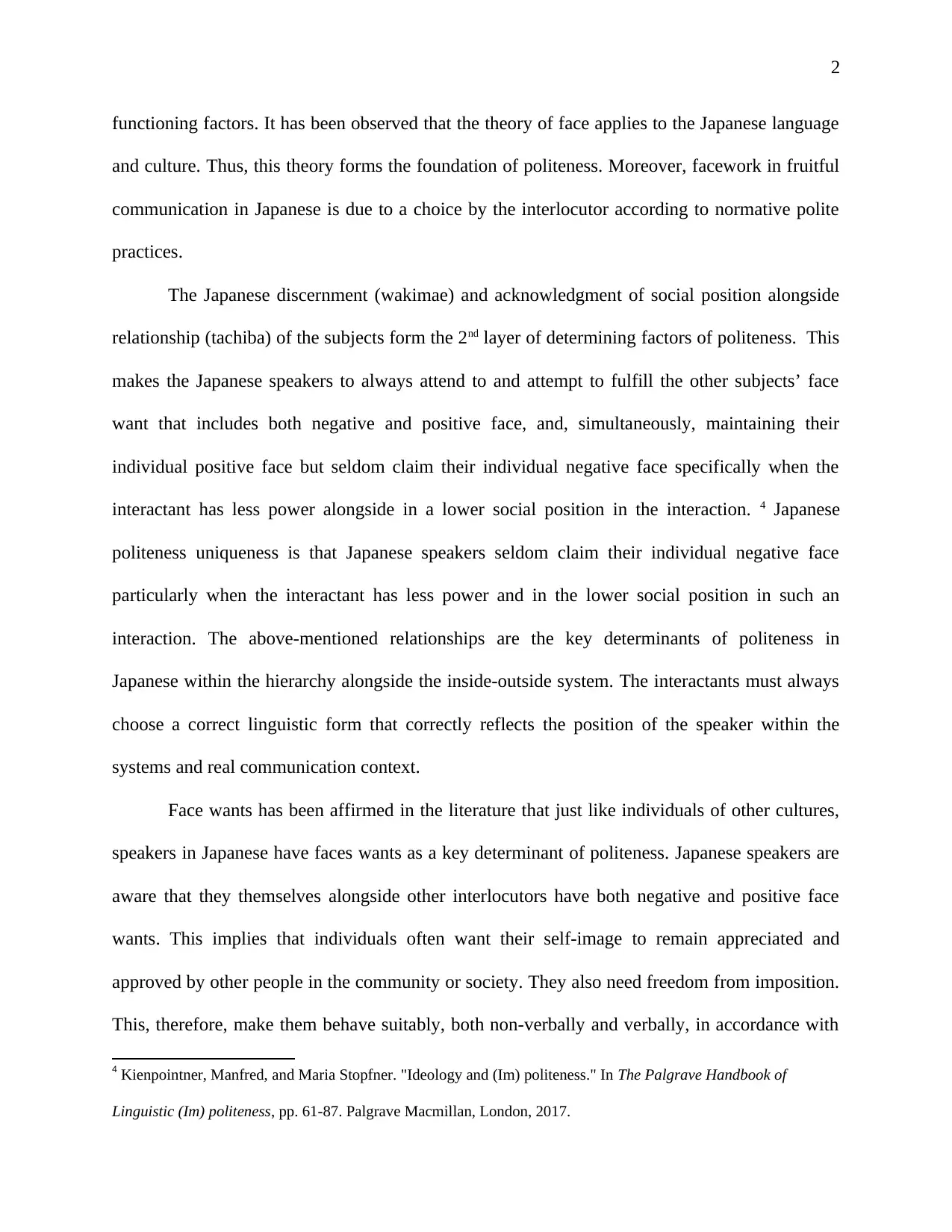

The uniqueness in the Japanese language alongside culture is that the discernment ensure

that every Japanese speaker often tend and attempt to fulfil the face wants of the other participant

which include both negative and positive face and simultaneously maintaining their individual

positive face but seldom claiming their individual negative face especially when the person

interacting has less power and stays in the lower social position in the given interaction. Indeed,

the interactant’s face in the lower social position and that with less power in the interactions

remains usually ignored. 6 The KOOT demonstrate how the face wants determinant influence

politeness. It shows how Asako, Haruko, and Kunikawa Tada, husband to Asako converse with

one another in different means prior and when Tada is battling extreme amnesia following

attempted suicide. This case shows the intention of the 3 speakers when Haruko meets Tada

following the amnesia and needs to re-introduce himself to him thus showing how face wants

determines politeness.

5 Al Abdely, Ammar Abdul-Wahab. "Power And Solidarity In Social Interactions: A Review Of Selected

Studies." Language & Communication 3, No. 1 (2016): 33 44.

6 Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave Handbook of

Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

their discernment (wakimae) in comprehending the social place alongside relationship within

social norm (tachiba). The chosen utterances thus reflect their relationships alongside the context

of a given interaction. 5

The uniqueness in the Japanese language alongside culture is that the discernment ensure

that every Japanese speaker often tend and attempt to fulfil the face wants of the other participant

which include both negative and positive face and simultaneously maintaining their individual

positive face but seldom claiming their individual negative face especially when the person

interacting has less power and stays in the lower social position in the given interaction. Indeed,

the interactant’s face in the lower social position and that with less power in the interactions

remains usually ignored. 6 The KOOT demonstrate how the face wants determinant influence

politeness. It shows how Asako, Haruko, and Kunikawa Tada, husband to Asako converse with

one another in different means prior and when Tada is battling extreme amnesia following

attempted suicide. This case shows the intention of the 3 speakers when Haruko meets Tada

following the amnesia and needs to re-introduce himself to him thus showing how face wants

determines politeness.

5 Al Abdely, Ammar Abdul-Wahab. "Power And Solidarity In Social Interactions: A Review Of Selected

Studies." Language & Communication 3, No. 1 (2016): 33 44.

6 Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave Handbook of

Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4

From the above conversation, it is observed how Tada has spoken down with consistent

to Asako (his wife) and Haruko (wife’s sister) and utilizes “hajimemashite” (how do you do”)

responding to the greeting from Haruko in Turn 2. He, he attaches honorific suffix ‘san’ to the

term ‘imooto’ (younger sister) alongside the honorific prefix ‘O’ to ask about the Haruko’s

occupation ‘shigoto’ (work) in turn five. He raises up Haruko by asserting ‘sugoi’ (great)

regarding her work utilizing the polite form of ‘capula desu’ in turn 7. From this change in

linguistic conduct, it is shown that as a result of Tada’s amnesia, he is unaware of whom he is

really communicating with and hence regards his relationship with other players in interaction

external (Soto). This further demonstrates that Tada wants to uphold/maintain his positive face, a

better self-image; and, for this intention, he selects the polite alongside honorific forms when

reflecting his interpretation of social relationship as he follows the social rules. 7

7 Clark, Paul. “The Genbun-itchi Society and the Drive to “Nationalize” the Japanese Language”. Japan Studies

Review 11 (2007): 99-115

From the above conversation, it is observed how Tada has spoken down with consistent

to Asako (his wife) and Haruko (wife’s sister) and utilizes “hajimemashite” (how do you do”)

responding to the greeting from Haruko in Turn 2. He, he attaches honorific suffix ‘san’ to the

term ‘imooto’ (younger sister) alongside the honorific prefix ‘O’ to ask about the Haruko’s

occupation ‘shigoto’ (work) in turn five. He raises up Haruko by asserting ‘sugoi’ (great)

regarding her work utilizing the polite form of ‘capula desu’ in turn 7. From this change in

linguistic conduct, it is shown that as a result of Tada’s amnesia, he is unaware of whom he is

really communicating with and hence regards his relationship with other players in interaction

external (Soto). This further demonstrates that Tada wants to uphold/maintain his positive face, a

better self-image; and, for this intention, he selects the polite alongside honorific forms when

reflecting his interpretation of social relationship as he follows the social rules. 7

7 Clark, Paul. “The Genbun-itchi Society and the Drive to “Nationalize” the Japanese Language”. Japan Studies

Review 11 (2007): 99-115

5

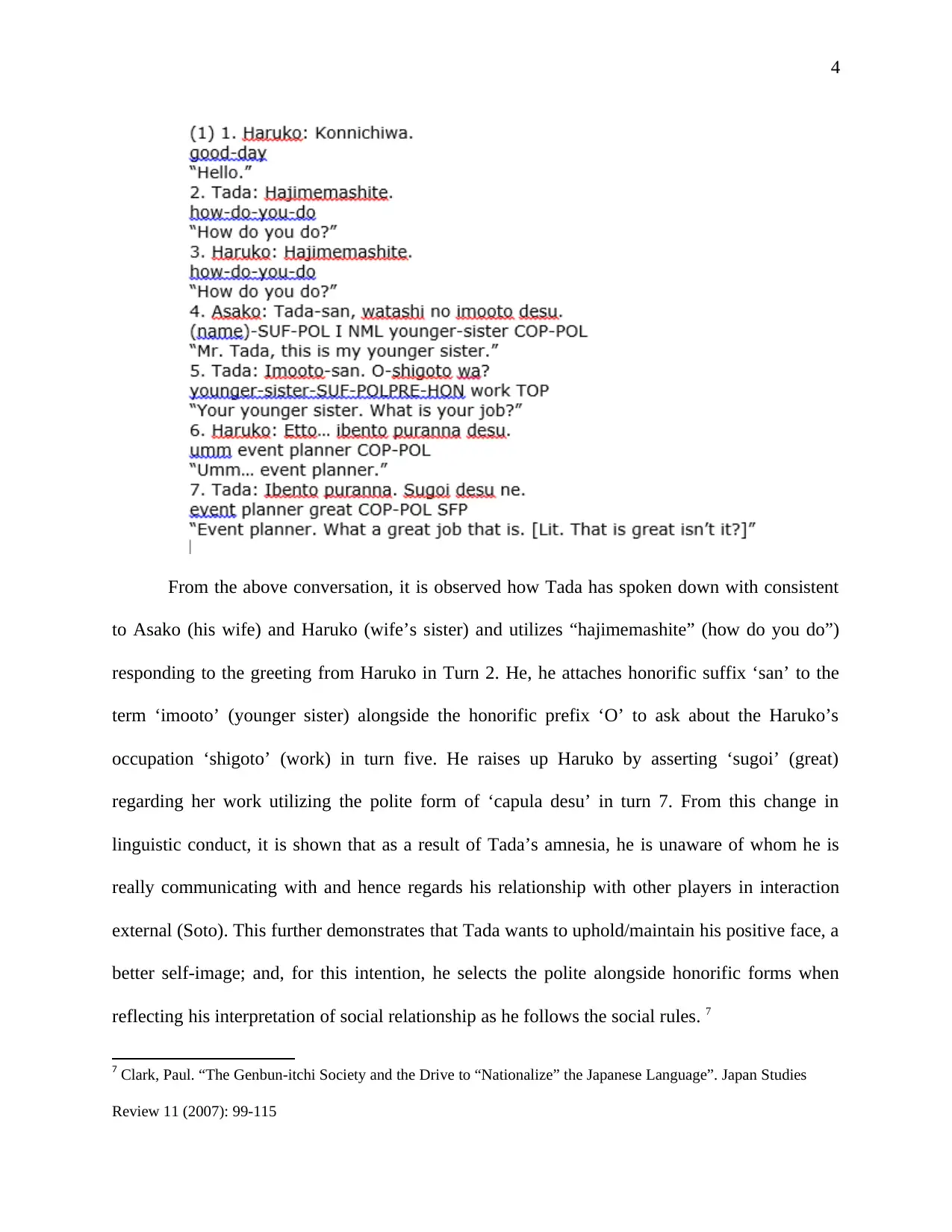

Conversely, the two sisters (Asako and Haruko) accommodate their style of speech to

Tada’s to maintain his negative face, rather than reminding Tada following his utterances in Turn

2 of communicating to his wife alongside sister-in-law and hence “How do you do” remains

improper in this particular setting. Such an accommodation is observable in Turn 3’s greeting

whereby Asuko uses honorific suffix “san” as she addresses her husband, alongside the polite

form of copula as observed in turn four and six. 8 This remains a completely different speech

from the normal style demonstrated below:

As observed overhead, the Asako and Haruko (sisters), talk normally to one another in

plain style/forms (da in turn 1 alongside nai in turn 3 & 4) and usually omit the main sentence

verbal (as seen in turn 1, 2 & 3). Whereas such utterances use the plain form or omitted forms,

8 Manosuthikit, Aree, and Peter I. De Costa. "Ideologizing age in an era of superdiversity: A heritage language

learner practice perspective." Applied Linguistics Review 7, no. 1 (2016): 1-25.

Conversely, the two sisters (Asako and Haruko) accommodate their style of speech to

Tada’s to maintain his negative face, rather than reminding Tada following his utterances in Turn

2 of communicating to his wife alongside sister-in-law and hence “How do you do” remains

improper in this particular setting. Such an accommodation is observable in Turn 3’s greeting

whereby Asuko uses honorific suffix “san” as she addresses her husband, alongside the polite

form of copula as observed in turn four and six. 8 This remains a completely different speech

from the normal style demonstrated below:

As observed overhead, the Asako and Haruko (sisters), talk normally to one another in

plain style/forms (da in turn 1 alongside nai in turn 3 & 4) and usually omit the main sentence

verbal (as seen in turn 1, 2 & 3). Whereas such utterances use the plain form or omitted forms,

8 Manosuthikit, Aree, and Peter I. De Costa. "Ideologizing age in an era of superdiversity: A heritage language

learner practice perspective." Applied Linguistics Review 7, no. 1 (2016): 1-25.

6

they are still polite, as the interactions occur within an inside association (relationship or Uchi).

Moreover, albeit in example (2) Haruko asks about Asako husband’s condition directly and

blames Asako of non-disclosure to her family how severe the condition is till this juncture, she is

never either with intention of or being interpreted by her sister (Asako) as threatening the

negative face of Asako.

This claim is supported by the evidence that the utterances of Haruko indeed creates an

opportunity for Asako to begin an emotional communication with her family. 9 This instance

establishes that the factor determining whether a given utterance forms Face Threatening Act

(FTA) is never its linguistic form but its given communicative function/illocutionary force

alongside the intention of the speaker within social rules/norms. In Example (2), direct questions

in omitted and plain forms remain uttered for the addressee (Asako’s) benefit. Thus, they

function to showcase the deep concern of speaker regarding speaker and addressee’s intention of

sharing hardness and to assist. They further remind the addressee of the inside association

(relationship) between the two interlocutors. Thus, it is needless for face re-dressing act required

as they never FTAs. 10

How do social differences such as gender and seniority level manifest themselves in polite

speech?

A social difference like gender and seniority level manifest themselves in polite speech.

The formation of Japanese etiquette stood substantially determined not only the societal

hierarchy but further Confucianism (Chinese ideals that influenced Japanese culture for a long

time) and religion. Confucianism describes a philosophical and ethical system established by the

9 Gottlieb, Nanette. Kanji politics: Language policy and Japanese script. Routledge, 1995.

10 Masuda, Akihiko. "Zen and Japanese Culture." In Handbook of Zen, Mindfulness, and Behavioral Health, pp. 29-

44. Springer, Cham, 2017.

they are still polite, as the interactions occur within an inside association (relationship or Uchi).

Moreover, albeit in example (2) Haruko asks about Asako husband’s condition directly and

blames Asako of non-disclosure to her family how severe the condition is till this juncture, she is

never either with intention of or being interpreted by her sister (Asako) as threatening the

negative face of Asako.

This claim is supported by the evidence that the utterances of Haruko indeed creates an

opportunity for Asako to begin an emotional communication with her family. 9 This instance

establishes that the factor determining whether a given utterance forms Face Threatening Act

(FTA) is never its linguistic form but its given communicative function/illocutionary force

alongside the intention of the speaker within social rules/norms. In Example (2), direct questions

in omitted and plain forms remain uttered for the addressee (Asako’s) benefit. Thus, they

function to showcase the deep concern of speaker regarding speaker and addressee’s intention of

sharing hardness and to assist. They further remind the addressee of the inside association

(relationship) between the two interlocutors. Thus, it is needless for face re-dressing act required

as they never FTAs. 10

How do social differences such as gender and seniority level manifest themselves in polite

speech?

A social difference like gender and seniority level manifest themselves in polite speech.

The formation of Japanese etiquette stood substantially determined not only the societal

hierarchy but further Confucianism (Chinese ideals that influenced Japanese culture for a long

time) and religion. Confucianism describes a philosophical and ethical system established by the

9 Gottlieb, Nanette. Kanji politics: Language policy and Japanese script. Routledge, 1995.

10 Masuda, Akihiko. "Zen and Japanese Culture." In Handbook of Zen, Mindfulness, and Behavioral Health, pp. 29-

44. Springer, Cham, 2017.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7

Chinese scholar Confucius in the fifth century BCE. Confucianism influenced Japanese

politeness during the Edo era when Neo-Confucianism became the Japanese state’s philosophy

and ruling classes. It is popular that Japanese treat the seniors or elders with special respect. The

speech style and manner in Japan is regarded as being imperative. It is essential to select a

communication style according to status and age of the addressee. The inadequately polite tone

will trigger the negative reaction of interlocutor and extra politeness is perceivable as a desire to

withdraw from the addressee. Thus, it remains imperative to obtain so-called golden mean.

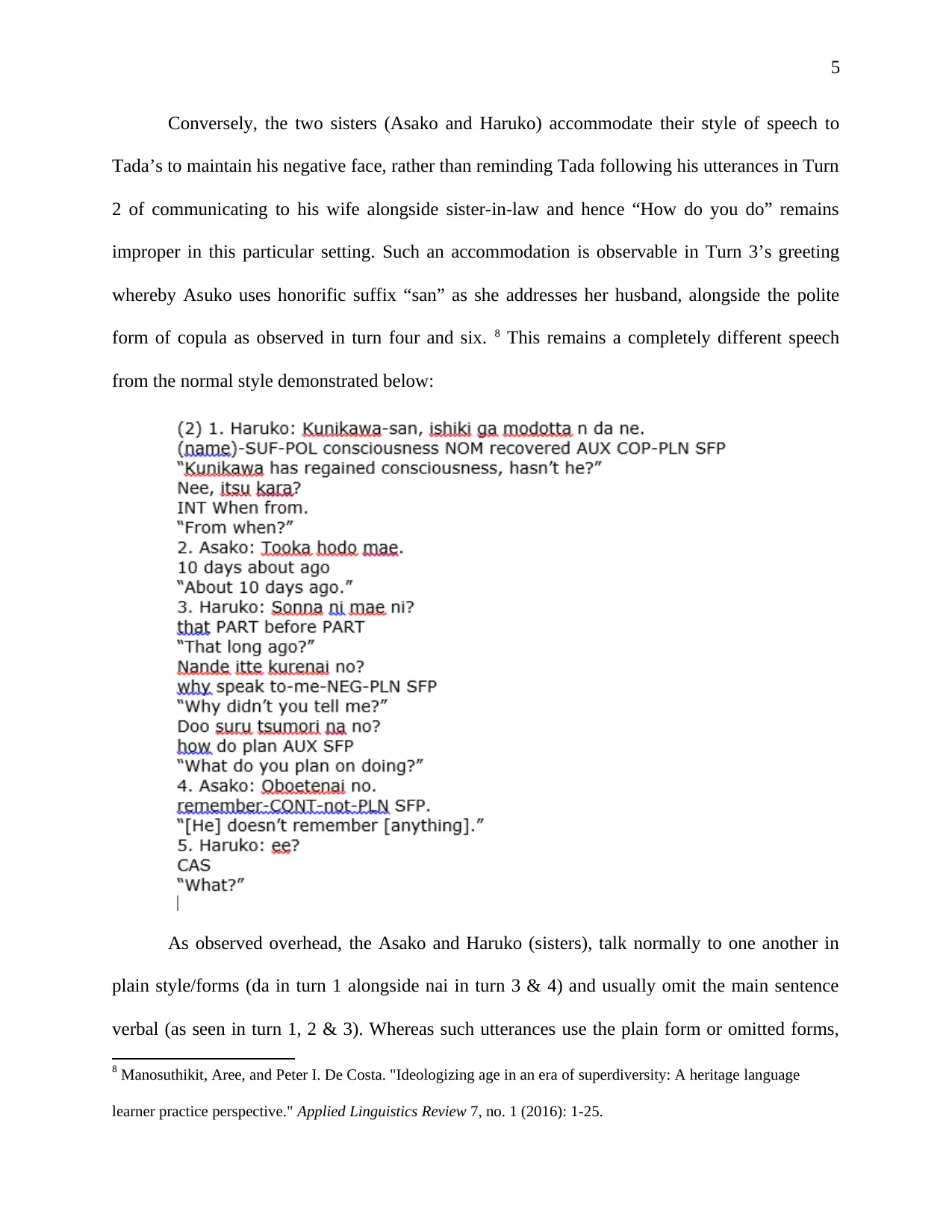

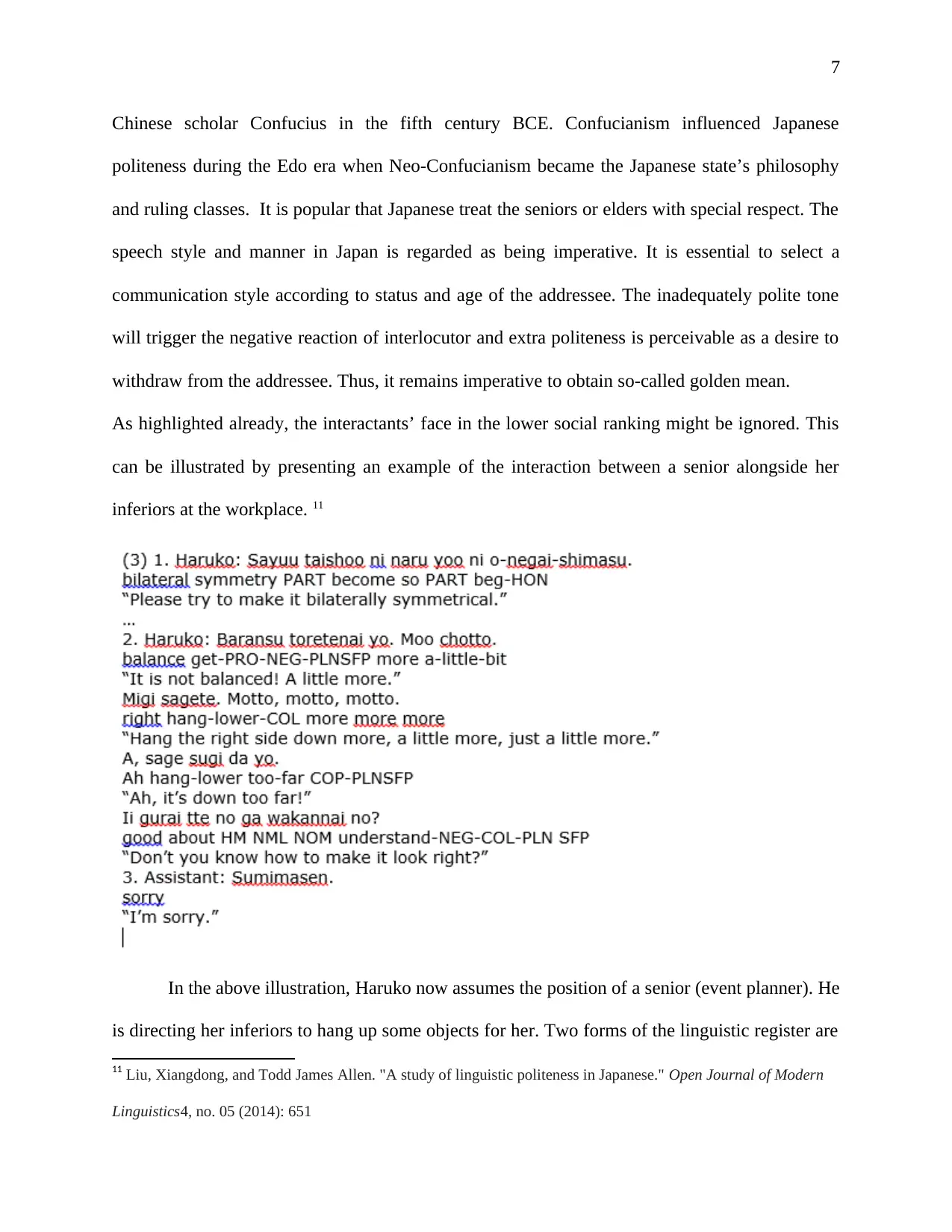

As highlighted already, the interactants’ face in the lower social ranking might be ignored. This

can be illustrated by presenting an example of the interaction between a senior alongside her

inferiors at the workplace. 11

In the above illustration, Haruko now assumes the position of a senior (event planner). He

is directing her inferiors to hang up some objects for her. Two forms of the linguistic register are

11 Liu, Xiangdong, and Todd James Allen. "A study of linguistic politeness in Japanese." Open Journal of Modern

Linguistics4, no. 05 (2014): 651

Chinese scholar Confucius in the fifth century BCE. Confucianism influenced Japanese

politeness during the Edo era when Neo-Confucianism became the Japanese state’s philosophy

and ruling classes. It is popular that Japanese treat the seniors or elders with special respect. The

speech style and manner in Japan is regarded as being imperative. It is essential to select a

communication style according to status and age of the addressee. The inadequately polite tone

will trigger the negative reaction of interlocutor and extra politeness is perceivable as a desire to

withdraw from the addressee. Thus, it remains imperative to obtain so-called golden mean.

As highlighted already, the interactants’ face in the lower social ranking might be ignored. This

can be illustrated by presenting an example of the interaction between a senior alongside her

inferiors at the workplace. 11

In the above illustration, Haruko now assumes the position of a senior (event planner). He

is directing her inferiors to hang up some objects for her. Two forms of the linguistic register are

11 Liu, Xiangdong, and Todd James Allen. "A study of linguistic politeness in Japanese." Open Journal of Modern

Linguistics4, no. 05 (2014): 651

8

displayed when her utterances are deconstructed. Haruko utilizes a humble form of the term,

“please”-(‘o-negai-shimasu’) as highlighted in turn 3 as she issues instructions to her assistant

(inferior), but then he downshifts her style of speech to non-polite one, employing plain form of

copula and verbs that is, “torenai, da and wakannai” alongside sentences that omit main verb

(i.e., the 1st and 2nd lines in turn 2). The use of polite style/form in turn 1 signpost the face

management of the speaker. This helps in nurturing the positive face of her own, and

simultaneously, mitigating her command’s force, which subsequently can maintain the negative

the negative face of the addressee. 12

In a culture of Japanese, it is quite acceptable to use less formal language alongside

conducting less face-saving work when communicating with inferiors. Thus, Haruko (senior) is

permitted by social rules of Japanese culture, to employ plain forms. Haruko thus needs no any

mechanism/strategy for defusing her direct instructions’ impact to save the negative face of

assistants (inferiors). Example 3 thus demonstrates the association between facework and

relationship hierarchy and social norms or rules. 13

The speech of women always appears much polite as opposed to men’s language based

on forms of linguistic such as requests and tag-questions. In communication, females remain

more probably to utilize politeness strategies in their speech as compared to males. Female

speakers always tend not to impose a perspective in their respective speech. Thus, females tend

12 Tanyaovalaksna, Sumeth. "Exploring the relationship between individual cultural values and employee silence."

PhD diss., University of Toronto (Canada), 2016.

13 Ting-Toomey, Stella, and Tenzin Dorjee. "Language, identity, and culture: multiple identity-based

perspectives." The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (2014): 27-45.

displayed when her utterances are deconstructed. Haruko utilizes a humble form of the term,

“please”-(‘o-negai-shimasu’) as highlighted in turn 3 as she issues instructions to her assistant

(inferior), but then he downshifts her style of speech to non-polite one, employing plain form of

copula and verbs that is, “torenai, da and wakannai” alongside sentences that omit main verb

(i.e., the 1st and 2nd lines in turn 2). The use of polite style/form in turn 1 signpost the face

management of the speaker. This helps in nurturing the positive face of her own, and

simultaneously, mitigating her command’s force, which subsequently can maintain the negative

the negative face of the addressee. 12

In a culture of Japanese, it is quite acceptable to use less formal language alongside

conducting less face-saving work when communicating with inferiors. Thus, Haruko (senior) is

permitted by social rules of Japanese culture, to employ plain forms. Haruko thus needs no any

mechanism/strategy for defusing her direct instructions’ impact to save the negative face of

assistants (inferiors). Example 3 thus demonstrates the association between facework and

relationship hierarchy and social norms or rules. 13

The speech of women always appears much polite as opposed to men’s language based

on forms of linguistic such as requests and tag-questions. In communication, females remain

more probably to utilize politeness strategies in their speech as compared to males. Female

speakers always tend not to impose a perspective in their respective speech. Thus, females tend

12 Tanyaovalaksna, Sumeth. "Exploring the relationship between individual cultural values and employee silence."

PhD diss., University of Toronto (Canada), 2016.

13 Ting-Toomey, Stella, and Tenzin Dorjee. "Language, identity, and culture: multiple identity-based

perspectives." The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (2014): 27-45.

9

to use more tag-questions than men as means of a polite statement to avoid forcing agreements or

belief on their addressees. 14

Men and women use tag-questions for different purposes. Women put stress on tag-

questions than men on polite or additional tags for uncertainty expression. Indeed, women tend

to always consider tag-questions as politeness indicator whereas men utilize such questions in

colloquial context for expression uncertainty. In Japanese, the foremost obligation of women is

that they have no master, and must consider the husband as her master and always serve him

with respect. The way of any woman depends on the obedience and towards her husband, the

woman has to remain polite, subservient as well as humble in terms of expression and language.

A woman must never be impatient or disobedient, nor rude or proud. 15

The discrepancy in linguistic is a reflection of the social disparity between men and

women since women’s language ‘submerges a female’s personal identity, by depriving woman

the means to strongly express herself on one hand, and inspiring expressions which show

triviality in subject matter alongside uncertainty about it. Women are thus regarded as inferior to

men and hence must use falling intonation as opposed to rising intonation as a sign to showcase

politeness. Women thus don’t consider themselves as male-equals and hence they are exposed to

believing that men’s rank they are tied to, husbands and fathers, remains their own, and where

the rank of such men stays high, women attempt to distinguish themselves from other fellow

females through expressively formal language. 16

Conclusion

14 de Mooij, Marieke. "Asian Communication." In Human and Mediated Communication around the World, pp.

105-135. Springer, Cham, 2014.

15 Siemund, Peter. Speech Acts and Clause Types: English in a Cross-Linguistic Context. Oxford University Press,

2018.

to use more tag-questions than men as means of a polite statement to avoid forcing agreements or

belief on their addressees. 14

Men and women use tag-questions for different purposes. Women put stress on tag-

questions than men on polite or additional tags for uncertainty expression. Indeed, women tend

to always consider tag-questions as politeness indicator whereas men utilize such questions in

colloquial context for expression uncertainty. In Japanese, the foremost obligation of women is

that they have no master, and must consider the husband as her master and always serve him

with respect. The way of any woman depends on the obedience and towards her husband, the

woman has to remain polite, subservient as well as humble in terms of expression and language.

A woman must never be impatient or disobedient, nor rude or proud. 15

The discrepancy in linguistic is a reflection of the social disparity between men and

women since women’s language ‘submerges a female’s personal identity, by depriving woman

the means to strongly express herself on one hand, and inspiring expressions which show

triviality in subject matter alongside uncertainty about it. Women are thus regarded as inferior to

men and hence must use falling intonation as opposed to rising intonation as a sign to showcase

politeness. Women thus don’t consider themselves as male-equals and hence they are exposed to

believing that men’s rank they are tied to, husbands and fathers, remains their own, and where

the rank of such men stays high, women attempt to distinguish themselves from other fellow

females through expressively formal language. 16

Conclusion

14 de Mooij, Marieke. "Asian Communication." In Human and Mediated Communication around the World, pp.

105-135. Springer, Cham, 2014.

15 Siemund, Peter. Speech Acts and Clause Types: English in a Cross-Linguistic Context. Oxford University Press,

2018.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

10

The examples 1, 2 and 3 discussed overhead demonstrate that Japanese speakers always

attend to face of their own and other people based on their respective discernment in

acknowledging the interactants’ relationship alongside positions. In the absence of consideration

for face, linguistic choice means like the ones demonstrated in examples 1, 2 and 3 cannot be

sufficiently explained. The above three examples are further verifications that linguistic

politeness is accomplished via multiple factors.

To accomplish the wants of a person’s face, it is imperative for a Japanese speaker to

acknowledge the association between interlocutors (for example uchi “inside”, Soto “outside”,

meue “superior”, meshita “inferior”), the interaction’s context alongside the social rules or norms

participants share when communicating. Put differently, without considering all these factors

parallel, no one can elucidate what is impolite or polite, why straight questions regarding the

private life of an individual in plain style/form like the ones illustrated in example 2 above serve

to showcase kindness or intimacy while certain other polite references might be FTA.

Japanese speakers need not act appropriately in accordance with social norms and their

comprehension or discernment of social rules/norms for a successful interaction, because this

remains common with other cultures. The uniqueness of Japanese linguistic lies in their

discernment (wakimae) and acknowledgment of social position alongside relationship (tachiba)

of interactants.

16 Wajdi, Majid, and Paulus Subiyanto. "Equality marker in the language of bali." In Journal of Physics: Conference

Series, vol. 953, no. 1, p. 012065. IOP Publishing, 2018.

The examples 1, 2 and 3 discussed overhead demonstrate that Japanese speakers always

attend to face of their own and other people based on their respective discernment in

acknowledging the interactants’ relationship alongside positions. In the absence of consideration

for face, linguistic choice means like the ones demonstrated in examples 1, 2 and 3 cannot be

sufficiently explained. The above three examples are further verifications that linguistic

politeness is accomplished via multiple factors.

To accomplish the wants of a person’s face, it is imperative for a Japanese speaker to

acknowledge the association between interlocutors (for example uchi “inside”, Soto “outside”,

meue “superior”, meshita “inferior”), the interaction’s context alongside the social rules or norms

participants share when communicating. Put differently, without considering all these factors

parallel, no one can elucidate what is impolite or polite, why straight questions regarding the

private life of an individual in plain style/form like the ones illustrated in example 2 above serve

to showcase kindness or intimacy while certain other polite references might be FTA.

Japanese speakers need not act appropriately in accordance with social norms and their

comprehension or discernment of social rules/norms for a successful interaction, because this

remains common with other cultures. The uniqueness of Japanese linguistic lies in their

discernment (wakimae) and acknowledgment of social position alongside relationship (tachiba)

of interactants.

16 Wajdi, Majid, and Paulus Subiyanto. "Equality marker in the language of bali." In Journal of Physics: Conference

Series, vol. 953, no. 1, p. 012065. IOP Publishing, 2018.

11

References

Al Abdely, Ammar Abdul-Wahab. "Power And Solidarity In Social Interactions: A Review Of

Selected Studies." Language & Communication 3, No. 1 (2016): 33 44.

Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. "Universals in language usage: Politeness

phenomena." In Questions and politeness: Strategies in social interaction, pp. 56-311.

Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Brown, Penelope, Stephen C. Levinson, and Stephen C. Levinson. Politeness: Some universals

in language usage. Vol. 4. Cambridge university press, 1987.

Clark, Paul. “The Genbun-itchi Society and the Drive to “Nationalize” the Japanese Language”.

Japan Studies Review 11 (2007): 99-115

de Mooij, Marieke. "Asian Communication." In Human and Mediated Communication around

the World, pp. 105-135. Springer, Cham, 2014.

Gottlieb, Nanette. Kanji politics: Language policy and Japanese script. Routledge, 1995.

Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A. and Ogino, T., 1986. Universals of linguistic politeness:

Quantitative evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of pragmatics, 10(3),

pp.347-371.

Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave

Handbook of Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

References

Al Abdely, Ammar Abdul-Wahab. "Power And Solidarity In Social Interactions: A Review Of

Selected Studies." Language & Communication 3, No. 1 (2016): 33 44.

Brown, Penelope, and Stephen C. Levinson. "Universals in language usage: Politeness

phenomena." In Questions and politeness: Strategies in social interaction, pp. 56-311.

Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Brown, Penelope, Stephen C. Levinson, and Stephen C. Levinson. Politeness: Some universals

in language usage. Vol. 4. Cambridge university press, 1987.

Clark, Paul. “The Genbun-itchi Society and the Drive to “Nationalize” the Japanese Language”.

Japan Studies Review 11 (2007): 99-115

de Mooij, Marieke. "Asian Communication." In Human and Mediated Communication around

the World, pp. 105-135. Springer, Cham, 2014.

Gottlieb, Nanette. Kanji politics: Language policy and Japanese script. Routledge, 1995.

Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A. and Ogino, T., 1986. Universals of linguistic politeness:

Quantitative evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of pragmatics, 10(3),

pp.347-371.

Kienpointner, Manfred, and Maria Stopfner. "Ideology and (Im) politeness." In The Palgrave

Handbook of Linguistic (Im) politeness, pp. 61-87. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017.

12

Liu, Shuang, Zala Volcic, and Cindy Gallois. Introducing intercultural communication: Global

cultures and contexts. Sage, 2014.

Mackie, Vera C. Japanese children and politeness. Japanese Studies Centre, 1983.

Manosuthikit, Aree, and Peter I. De Costa. "Ideologizing age in an era of superdiversity: A

heritage language learner practice perspective." Applied Linguistics Review 7, no. 1 (2016): 1-25.

Masuda, Akihiko. "Zen and Japanese Culture." In Handbook of Zen, Mindfulness, and

Behavioral Health, pp. 29-44. Springer, Cham, 2017.

Mehra, Payal. Communication Beyond Boundaries. Business Expert Press, 2014.

Siemund, Peter. Speech Acts and Clause Types: English in a Cross-Linguistic Context. Oxford

University Press, 2018.

Takeuchi, Jae DiBello. Dialect Matters: L2 Speakers' Beliefs and Perceptions About Japanese

Dialect. The University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2015.

Tanyaovalaksna, Sumeth. "Exploring the relationship between individual cultural values and

employee silence." PhD diss., University of Toronto (Canada), 2016.

Ting-Toomey, Stella, and Tenzin Dorjee. "Language, identity, and culture: multiple identity-

based perspectives." The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (2014): 27-45.

Wajdi, Majid, and Paulus Subiyanto. "Equality marker in the language of bali." In Journal of

Physics: Conference Series, vol. 953, no. 1, p. 012065. IOP Publishing, 2018.

Liu, Xiangdong, and Todd James Allen. "A study of linguistic politeness in Japanese." Open Journal of

Modern Linguistics4, no. 05 (2014): 651.

Liu, Shuang, Zala Volcic, and Cindy Gallois. Introducing intercultural communication: Global

cultures and contexts. Sage, 2014.

Mackie, Vera C. Japanese children and politeness. Japanese Studies Centre, 1983.

Manosuthikit, Aree, and Peter I. De Costa. "Ideologizing age in an era of superdiversity: A

heritage language learner practice perspective." Applied Linguistics Review 7, no. 1 (2016): 1-25.

Masuda, Akihiko. "Zen and Japanese Culture." In Handbook of Zen, Mindfulness, and

Behavioral Health, pp. 29-44. Springer, Cham, 2017.

Mehra, Payal. Communication Beyond Boundaries. Business Expert Press, 2014.

Siemund, Peter. Speech Acts and Clause Types: English in a Cross-Linguistic Context. Oxford

University Press, 2018.

Takeuchi, Jae DiBello. Dialect Matters: L2 Speakers' Beliefs and Perceptions About Japanese

Dialect. The University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2015.

Tanyaovalaksna, Sumeth. "Exploring the relationship between individual cultural values and

employee silence." PhD diss., University of Toronto (Canada), 2016.

Ting-Toomey, Stella, and Tenzin Dorjee. "Language, identity, and culture: multiple identity-

based perspectives." The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (2014): 27-45.

Wajdi, Majid, and Paulus Subiyanto. "Equality marker in the language of bali." In Journal of

Physics: Conference Series, vol. 953, no. 1, p. 012065. IOP Publishing, 2018.

Liu, Xiangdong, and Todd James Allen. "A study of linguistic politeness in Japanese." Open Journal of

Modern Linguistics4, no. 05 (2014): 651.

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.