Journal of Business Research: Luxury Consumption Study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|8

|9839

|187

Report

AI Summary

This research article, published in the Journal of Business Research, investigates the multifaceted nature of conspicuous luxury consumption. It moves beyond the traditional focus on status seeking to explore how individual differences, such as self-concept orientation, susceptibility to normative influence, and need for uniqueness, shape consumer behavior. The study develops and empirically confirms a model that identifies two distinct patterns of conspicuous luxury consumption: bandwagon and snob effects. It highlights the role of self-concept in regulating these patterns and emphasizes the importance of understanding these psychological constructs for developing effective marketing strategies. The research contributes to the literature by offering a more nuanced understanding of luxury consumption, moving away from a monolithic conception to include sub-variants and providing valuable insights for managers seeking to tailor strategies to different consumer segments.

Explaining variation in conspicuous luxury consumption: An individual

differences' perspective☆

Minas N. Kastanakisa,

⁎, George Balabanisb

a ESCP Europe, 527 Finchley Road, London NW3 7BG, United Kingdom

b Cass Business School, City University London, 106 Bunhill Row, London EC1 8TZ, United Kingdom

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 March 2014

Received in revised form 1 April 2014

Accepted 30 April 2014

Available online 15 May 2014

Keywords:

Conspicuous consumption

Luxury

Self-concept

Status

Bandwagon and snob effects

This article examines the impact of various individual differences on consumers' propensity to engage in tw

distinct forms of conspicuous (publicly observable) luxury consumption behavior.Status seeking is an

established driver, but other managerially relevant drivers can also explain conspicuous consumption of lux

The study develops and empirically confirms a conceptual model that shows that bandwagon and snobbish

buying patterns underlie the more generic conspicuous consumption of luxuries. In addition to status seekin

the self-concept orientation regulates which of these two patterns is more prominent. Both susceptibility to

normative influence and need for uniqueness mediate the in fluence of self-concept. The modeled psycholog

constructs explain a large part of the variance in conspicuous luxury consumption patterns and can be used

input in the development of marketing strategies.

© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Acquiring and conspicuously displaying luxuries is an important

part of many modern lifestyles in both affluent Western societies and

the developing world (Bian & Forsythe, 2010; Ko & Megehee, 2010; Li,

Li, & Kambele, 2010; Zhan & Yanqun, 2010). Luxury consumers include

a new base of younger, well-paid, and spendthrift people claiming their

stake in the high life (Silverstein & Fiske, 2003). Luxury brands' evolu-

tionary trajectory in the marketplace mirrors these changes. The once

elitist luxury consumption is now available to the masses, adding com-

plexity to its public aspects (Bearden & Etzel, 1982). Such complexity

challenges not only the adequacy of the status-seeking motive (Han,

Nunes,& Drèze,2010; Nelissen & Meijers,2011; Rucker & Galinsky,

2008) in explaining luxury consumption but also the perpetuated

view that luxury consumption is a homogeneous behavior.

Empirical observations from practitioner-oriented research confirm

these developments by suggesting that consumers of luxury pursue a

diversity of goals.For example,some consumers “rather than signal

[ing] their wealth with the latest Rolex or Prada bag, … seek a one-off,

custom-made product that no one else will ever own” (Reddy, 2008,

p. 64). However, for the majority of luxury brands, “the bulk of their

business lies in the mass market demand” (Reddy, 2008, p. 67), creatin

new segments of luxuries and consumers.

Consequently,luxury markets are more heterogeneous than the

status-driven literature suggests. This notion has important repercus-

sions for scholars and practitioners. Indeed, research on conspicuous

consumption calls for deeper examination of the characteristics of

luxury consumers (Wilcox, Kim, & Sen, 2009). Focusing exclusively on

status as a motivation for conspicuous luxury consumption leaves out

a substantial amount of status-conferring capacity luxury products,

including both highly exclusive luxuries (Van Gorp, Hoffmann, &

Coste-Maniere, 2012; Woodside, 2012) and widely available, popular

luxuries.These are reflective of the variation in buyers' motives and

consumption patterns. Therefore, examining the conspicuous consump-

tion of luxuries more holistically is imperative.

The purpose of this research is to empirically identify and test two

types of conspicuous luxury consumption—namely,bandwagon and

snob—and the antecedents underlying consumers' engagement in the

bandwagon or snobbery type of luxury buying behavior. In particular,

the focus is on luxury consumption not as homogeneous behavior but

as multi-dimensional heterogeneous behavior. This study also identifies

the individual-level characteristics that encourage these consumption

behavior variants. From this standpoint, the study conceptualizes and

tests a model of conspicuous luxury consumption on survey data.

The findings reveal that consumption of luxury is a multi-faceted

behavior, driven by a wide variety of factors, in addition to the long-

established motivation ofstatus attainment.This research makes

several contributions. First, by jointly testing two ostensibly antithetical

Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

☆ The authors thank RussellBelk and Mario Pandelaere for their comments on a

previous draft. The authors are responsible for all limitations and errors.

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 77 8959 7031.

E-mail addresses: mkastanakis@escpeurope.eu (M.N. Kastanakis),

g.balabanis@city.ac.uk (G. Balabanis).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.024

0148-2963/© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

differences' perspective☆

Minas N. Kastanakisa,

⁎, George Balabanisb

a ESCP Europe, 527 Finchley Road, London NW3 7BG, United Kingdom

b Cass Business School, City University London, 106 Bunhill Row, London EC1 8TZ, United Kingdom

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 March 2014

Received in revised form 1 April 2014

Accepted 30 April 2014

Available online 15 May 2014

Keywords:

Conspicuous consumption

Luxury

Self-concept

Status

Bandwagon and snob effects

This article examines the impact of various individual differences on consumers' propensity to engage in tw

distinct forms of conspicuous (publicly observable) luxury consumption behavior.Status seeking is an

established driver, but other managerially relevant drivers can also explain conspicuous consumption of lux

The study develops and empirically confirms a conceptual model that shows that bandwagon and snobbish

buying patterns underlie the more generic conspicuous consumption of luxuries. In addition to status seekin

the self-concept orientation regulates which of these two patterns is more prominent. Both susceptibility to

normative influence and need for uniqueness mediate the in fluence of self-concept. The modeled psycholog

constructs explain a large part of the variance in conspicuous luxury consumption patterns and can be used

input in the development of marketing strategies.

© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Acquiring and conspicuously displaying luxuries is an important

part of many modern lifestyles in both affluent Western societies and

the developing world (Bian & Forsythe, 2010; Ko & Megehee, 2010; Li,

Li, & Kambele, 2010; Zhan & Yanqun, 2010). Luxury consumers include

a new base of younger, well-paid, and spendthrift people claiming their

stake in the high life (Silverstein & Fiske, 2003). Luxury brands' evolu-

tionary trajectory in the marketplace mirrors these changes. The once

elitist luxury consumption is now available to the masses, adding com-

plexity to its public aspects (Bearden & Etzel, 1982). Such complexity

challenges not only the adequacy of the status-seeking motive (Han,

Nunes,& Drèze,2010; Nelissen & Meijers,2011; Rucker & Galinsky,

2008) in explaining luxury consumption but also the perpetuated

view that luxury consumption is a homogeneous behavior.

Empirical observations from practitioner-oriented research confirm

these developments by suggesting that consumers of luxury pursue a

diversity of goals.For example,some consumers “rather than signal

[ing] their wealth with the latest Rolex or Prada bag, … seek a one-off,

custom-made product that no one else will ever own” (Reddy, 2008,

p. 64). However, for the majority of luxury brands, “the bulk of their

business lies in the mass market demand” (Reddy, 2008, p. 67), creatin

new segments of luxuries and consumers.

Consequently,luxury markets are more heterogeneous than the

status-driven literature suggests. This notion has important repercus-

sions for scholars and practitioners. Indeed, research on conspicuous

consumption calls for deeper examination of the characteristics of

luxury consumers (Wilcox, Kim, & Sen, 2009). Focusing exclusively on

status as a motivation for conspicuous luxury consumption leaves out

a substantial amount of status-conferring capacity luxury products,

including both highly exclusive luxuries (Van Gorp, Hoffmann, &

Coste-Maniere, 2012; Woodside, 2012) and widely available, popular

luxuries.These are reflective of the variation in buyers' motives and

consumption patterns. Therefore, examining the conspicuous consump-

tion of luxuries more holistically is imperative.

The purpose of this research is to empirically identify and test two

types of conspicuous luxury consumption—namely,bandwagon and

snob—and the antecedents underlying consumers' engagement in the

bandwagon or snobbery type of luxury buying behavior. In particular,

the focus is on luxury consumption not as homogeneous behavior but

as multi-dimensional heterogeneous behavior. This study also identifies

the individual-level characteristics that encourage these consumption

behavior variants. From this standpoint, the study conceptualizes and

tests a model of conspicuous luxury consumption on survey data.

The findings reveal that consumption of luxury is a multi-faceted

behavior, driven by a wide variety of factors, in addition to the long-

established motivation ofstatus attainment.This research makes

several contributions. First, by jointly testing two ostensibly antithetical

Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

☆ The authors thank RussellBelk and Mario Pandelaere for their comments on a

previous draft. The authors are responsible for all limitations and errors.

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 77 8959 7031.

E-mail addresses: mkastanakis@escpeurope.eu (M.N. Kastanakis),

g.balabanis@city.ac.uk (G. Balabanis).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.024

0148-2963/© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

facets of conspicuous luxury consumption and their shared antecedents,

this study extends the evolving literature on luxury and conspicuous

consumption by moving away from a monolithic conception of luxury

to include sub-variants. Second, it helps managers develop elaborate

strategies to suit each of the snobbish and bandwagon consumption

patterns.

2. Theoretical background

Research in economics conceptualizes distinct conspicuous con-

sumption patterns depending on a good's quantity in a market. Extend-

ing Veblen's (1899) invidious comparison and pecuniary emulation,

Leibenstein (1950) develops a mathematical explanation for external

effects on utility of any generalproduct.Leibenstein (1950,p. 189)

defines the bandwagon effect as “the extent to which the demand for

a commodity is increased due to the fact that others are also consuming

the same commodity” and describes the snob effect as “the extent to

which the demand for a consumer's good is decreased owing to the

fact that others are also consuming the same commodity.” Not explicitly

mentioned in this definition is that the demand decreases among snobs

but not among overall consumers. Leibenstein mentions associative and

dissociative motives but does not propose specific antecedents and his

analysis does not move beyond the mathematics.

Recent work consists of mostly conceptual or mathematical model-

ing and focuses on snobbish and conformist patterns in the demand

for luxuries (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Corneo & Jeanne, 1997; Ireland,

1994). However, none of these studies examine individual consumers

and their proclivity toward conspicuous consumption. Thus, although

economic models are useful in modeling such phenomena, they offer

limited guidance for managers because they do not identify specific,

controllable variables related to individual consumers.

Conversely, the consumer behavior literature generally views luxury

consumption as a homogeneous behavior where the key driver is the

status symbolism. Accordingly, research defines luxuries as goods such

that their mere use or display confers prestige or status to the owner

apart from any functionalutility (Grossman & Shapiro,1988; Han

et al., 2010) and provides insightful analyses of the relationship

between status and luxury under several different conditions (Han

et al., 2010; Nelissen & Meijers,2011; Nunes,Drèze,& Han, 2011;

Rucker & Galinsky, 2008). Nevertheless, extant research tends both to

overemphasize the status antecedent and to assume homogeneity in

consumption behavior, thus overlooking theoretical work in economics

and empirically oriented market reports that suggest a more complex

phenomenon.Enhancing this perspective,the next section presents

arguments for re-conceptualizing luxury consumption as a broader

behavior.

3. Re-conceptualizing luxury consumption

The traditional luxury sector's value (i.e., European firms with a long

heritage) is $302 billion worldwide and expected to reach $376 billion

by 2017 (King, 2013), up from a mere $20 billion in 1985 (Barry,

2010). Including new luxury products from contemporary firms in

various premium categories raises the value of the global luxury market

to $1 trillion (Truong, 2010). Reflective of this variation is the

emergence of conglomerate groups (LVMH,Richemont,PPR, Gucci)

with stretched portfolios of different brands in both scarcer and mass-

luxury markets. For example, the LVMH group owns exclusive brands,

such as Berluti (founded in 1895),and popular ones,such as Mark

Jacobs (founded in 1984).

This variation between traditional and new luxuries leads scholars to

disagree on a precise typology of luxury brands (Dion & Arnould, 2011).

In view of the difficulty in concretely classifying luxuries, the focus here

is on how and why people buy and consume different types of luxuries.

In addition to their utility in conferring status (Nelissen & Meijers,

2011), some luxury brands are valued for their scarcity, while others

are preferred because of their popularity (Amaldoss & Jain,2008).

Going beyond mathematical or product-centered marketing studies,

this study analyzes the influence of the self and other antecedent traits

on luxury consumption. The main focus is on luxury brands' capability

of creating assimilation to (i.e., bandwagon consumption) or contrast

with (i.e., snob consumption) other consumers (Mussweiler, Rüter, &

Epstude, 2004). In addition, the study moves from a monolithic concep-

tion of luxury to include sub-variants, such as snobbish and conformist

consumption patterns.Owing to their highly symbolic properties

(Wiedmann, Hennigs, & Siebels, 2009), luxuries can create a sense of

affiliation to or differentiation from other consumers. Consumers use

the vast assortmentof luxury brands on the market in relational

patterns,creating assimilation to the kinds ofpeople who display

them. A minority uses scarce, new, or unknown luxuries in contrast-

creating patterns, creating distance from other consumers.

Individual differences play a major role in determining consumer

preferences for relational versus contrast-creating brands. Relational

traits,such as an inter-dependent self-concept and susceptibility to

normative influence, drive bandwagon luxury consumption and pro-

mote an assimilation goal.Conversely,dissociative traits,such as an

independent self-concept and need for uniqueness, drive snob luxury

consumption and promote a contrast goal. As more people gain access

to luxury, understanding the subtle individual differences that differen-

tiate consumers is imperative.Such insights can inform the existing

socio-economic analyses (leaders vs. followers, snobs vs. conformists)

revolving around status. Table 1 summarizes these ideas that contribute

to the literature by integrating several previously unconnected streams

of research and by adding new elements.The ensuing analysis adds

depth by shedding new light on the complexity of previous research.

4. Model development

A two-step iterative process served to identify the most relevant

antecedents of conspicuous luxury consumption. First, a synthesis of

the pertinent literature helped determine a set ofantecedents to

bandwagon and snob consumption. Second, in-depth interviews with

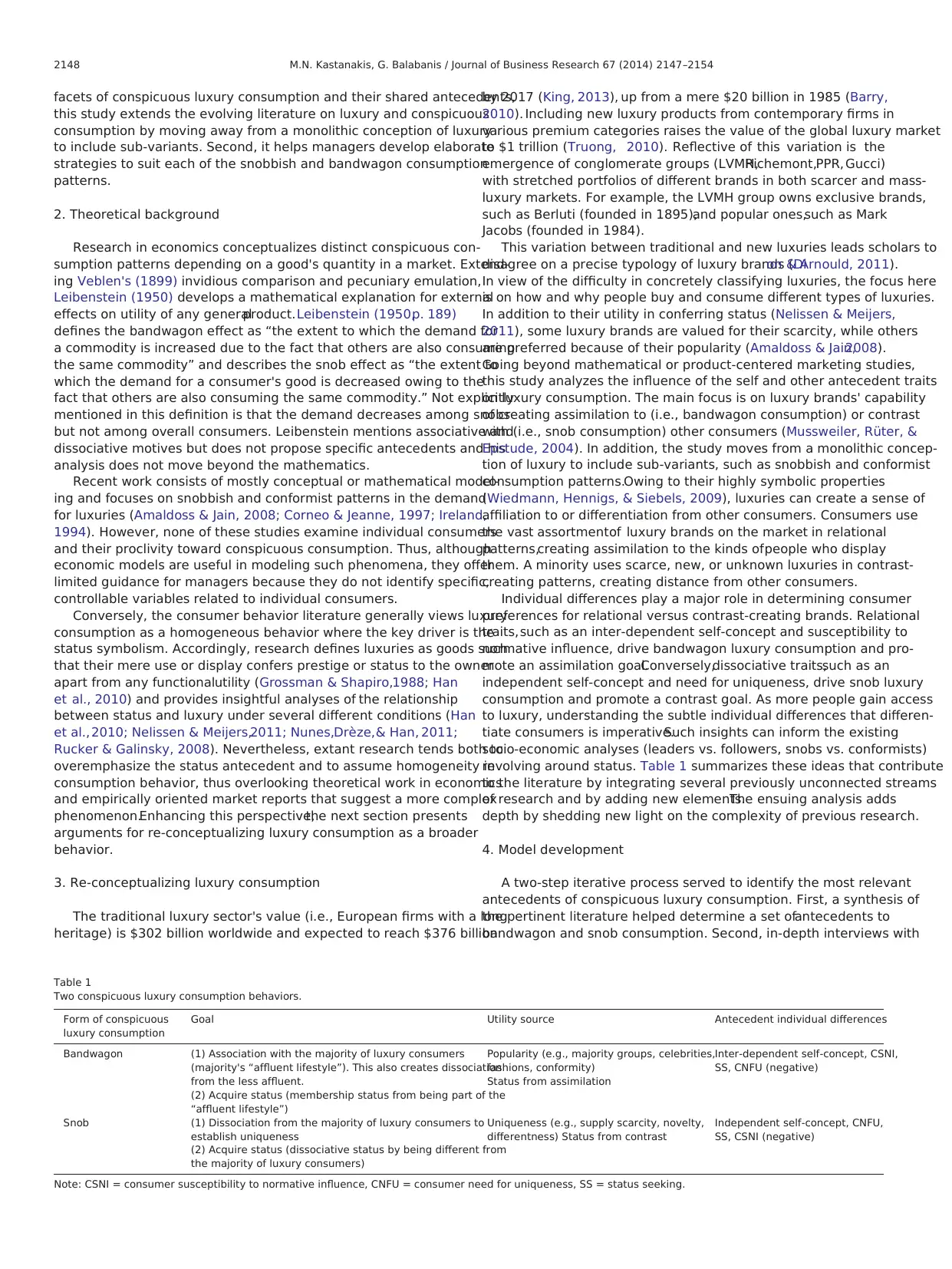

Table 1

Two conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors.

Form of conspicuous

luxury consumption

Goal Utility source Antecedent individual differences

Bandwagon (1) Association with the majority of luxury consumers

(majority's “affluent lifestyle”). This also creates dissociation

from the less affluent.

Popularity (e.g., majority groups, celebrities,

fashions, conformity)

Status from assimilation

Inter-dependent self-concept, CSNI,

SS, CNFU (negative)

(2) Acquire status (membership status from being part of the

“affluent lifestyle”)

Snob (1) Dissociation from the majority of luxury consumers to

establish uniqueness

Uniqueness (e.g., supply scarcity, novelty,

differentness) Status from contrast

Independent self-concept, CNFU,

SS, CSNI (negative)

(2) Acquire status (dissociative status by being different from

the majority of luxury consumers)

Note: CSNI = consumer susceptibility to normative influence, CNFU = consumer need for uniqueness, SS = status seeking.

2148 M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

this study extends the evolving literature on luxury and conspicuous

consumption by moving away from a monolithic conception of luxury

to include sub-variants. Second, it helps managers develop elaborate

strategies to suit each of the snobbish and bandwagon consumption

patterns.

2. Theoretical background

Research in economics conceptualizes distinct conspicuous con-

sumption patterns depending on a good's quantity in a market. Extend-

ing Veblen's (1899) invidious comparison and pecuniary emulation,

Leibenstein (1950) develops a mathematical explanation for external

effects on utility of any generalproduct.Leibenstein (1950,p. 189)

defines the bandwagon effect as “the extent to which the demand for

a commodity is increased due to the fact that others are also consuming

the same commodity” and describes the snob effect as “the extent to

which the demand for a consumer's good is decreased owing to the

fact that others are also consuming the same commodity.” Not explicitly

mentioned in this definition is that the demand decreases among snobs

but not among overall consumers. Leibenstein mentions associative and

dissociative motives but does not propose specific antecedents and his

analysis does not move beyond the mathematics.

Recent work consists of mostly conceptual or mathematical model-

ing and focuses on snobbish and conformist patterns in the demand

for luxuries (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Corneo & Jeanne, 1997; Ireland,

1994). However, none of these studies examine individual consumers

and their proclivity toward conspicuous consumption. Thus, although

economic models are useful in modeling such phenomena, they offer

limited guidance for managers because they do not identify specific,

controllable variables related to individual consumers.

Conversely, the consumer behavior literature generally views luxury

consumption as a homogeneous behavior where the key driver is the

status symbolism. Accordingly, research defines luxuries as goods such

that their mere use or display confers prestige or status to the owner

apart from any functionalutility (Grossman & Shapiro,1988; Han

et al., 2010) and provides insightful analyses of the relationship

between status and luxury under several different conditions (Han

et al., 2010; Nelissen & Meijers,2011; Nunes,Drèze,& Han, 2011;

Rucker & Galinsky, 2008). Nevertheless, extant research tends both to

overemphasize the status antecedent and to assume homogeneity in

consumption behavior, thus overlooking theoretical work in economics

and empirically oriented market reports that suggest a more complex

phenomenon.Enhancing this perspective,the next section presents

arguments for re-conceptualizing luxury consumption as a broader

behavior.

3. Re-conceptualizing luxury consumption

The traditional luxury sector's value (i.e., European firms with a long

heritage) is $302 billion worldwide and expected to reach $376 billion

by 2017 (King, 2013), up from a mere $20 billion in 1985 (Barry,

2010). Including new luxury products from contemporary firms in

various premium categories raises the value of the global luxury market

to $1 trillion (Truong, 2010). Reflective of this variation is the

emergence of conglomerate groups (LVMH,Richemont,PPR, Gucci)

with stretched portfolios of different brands in both scarcer and mass-

luxury markets. For example, the LVMH group owns exclusive brands,

such as Berluti (founded in 1895),and popular ones,such as Mark

Jacobs (founded in 1984).

This variation between traditional and new luxuries leads scholars to

disagree on a precise typology of luxury brands (Dion & Arnould, 2011).

In view of the difficulty in concretely classifying luxuries, the focus here

is on how and why people buy and consume different types of luxuries.

In addition to their utility in conferring status (Nelissen & Meijers,

2011), some luxury brands are valued for their scarcity, while others

are preferred because of their popularity (Amaldoss & Jain,2008).

Going beyond mathematical or product-centered marketing studies,

this study analyzes the influence of the self and other antecedent traits

on luxury consumption. The main focus is on luxury brands' capability

of creating assimilation to (i.e., bandwagon consumption) or contrast

with (i.e., snob consumption) other consumers (Mussweiler, Rüter, &

Epstude, 2004). In addition, the study moves from a monolithic concep-

tion of luxury to include sub-variants, such as snobbish and conformist

consumption patterns.Owing to their highly symbolic properties

(Wiedmann, Hennigs, & Siebels, 2009), luxuries can create a sense of

affiliation to or differentiation from other consumers. Consumers use

the vast assortmentof luxury brands on the market in relational

patterns,creating assimilation to the kinds ofpeople who display

them. A minority uses scarce, new, or unknown luxuries in contrast-

creating patterns, creating distance from other consumers.

Individual differences play a major role in determining consumer

preferences for relational versus contrast-creating brands. Relational

traits,such as an inter-dependent self-concept and susceptibility to

normative influence, drive bandwagon luxury consumption and pro-

mote an assimilation goal.Conversely,dissociative traits,such as an

independent self-concept and need for uniqueness, drive snob luxury

consumption and promote a contrast goal. As more people gain access

to luxury, understanding the subtle individual differences that differen-

tiate consumers is imperative.Such insights can inform the existing

socio-economic analyses (leaders vs. followers, snobs vs. conformists)

revolving around status. Table 1 summarizes these ideas that contribute

to the literature by integrating several previously unconnected streams

of research and by adding new elements.The ensuing analysis adds

depth by shedding new light on the complexity of previous research.

4. Model development

A two-step iterative process served to identify the most relevant

antecedents of conspicuous luxury consumption. First, a synthesis of

the pertinent literature helped determine a set ofantecedents to

bandwagon and snob consumption. Second, in-depth interviews with

Table 1

Two conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors.

Form of conspicuous

luxury consumption

Goal Utility source Antecedent individual differences

Bandwagon (1) Association with the majority of luxury consumers

(majority's “affluent lifestyle”). This also creates dissociation

from the less affluent.

Popularity (e.g., majority groups, celebrities,

fashions, conformity)

Status from assimilation

Inter-dependent self-concept, CSNI,

SS, CNFU (negative)

(2) Acquire status (membership status from being part of the

“affluent lifestyle”)

Snob (1) Dissociation from the majority of luxury consumers to

establish uniqueness

Uniqueness (e.g., supply scarcity, novelty,

differentness) Status from contrast

Independent self-concept, CNFU,

SS, CSNI (negative)

(2) Acquire status (dissociative status by being different from

the majority of luxury consumers)

Note: CSNI = consumer susceptibility to normative influence, CNFU = consumer need for uniqueness, SS = status seeking.

2148 M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

six senior marketing managers of luxury brands were conducted to

(1) gain a spontaneous, freely elicited perspective on the bandwagon/

snobbish luxury consumer and (2) provide practical insights into the

antecedents identified. The findings enabled a further literature search

for relevant concepts, while screening out others. The resultant model

was presented to the interviewees for additional refinement.From

this process,the consumer self-concept orientation,need for status,

and two mediating traits (consumer susceptibility to normative influ-

ence [CSNI] and consumer need for uniqueness [CNFU]) emerged as

most relevant to the conspicuous consumption of luxuries.

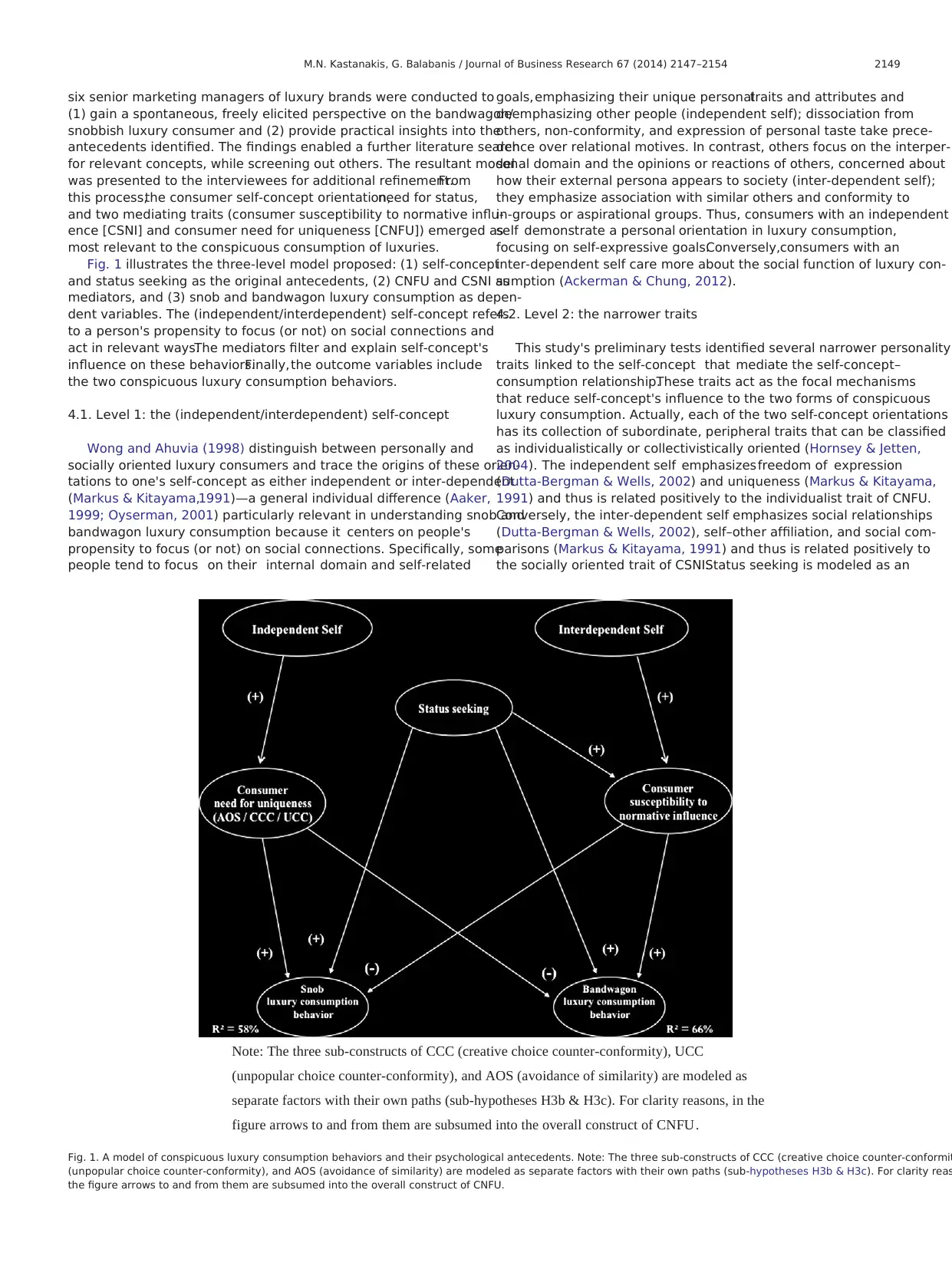

Fig. 1 illustrates the three-level model proposed: (1) self-concept

and status seeking as the original antecedents, (2) CNFU and CSNI as

mediators, and (3) snob and bandwagon luxury consumption as depen-

dent variables. The (independent/interdependent) self-concept refers

to a person's propensity to focus (or not) on social connections and

act in relevant ways.The mediators filter and explain self-concept's

influence on these behaviors.Finally,the outcome variables include

the two conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors.

4.1. Level 1: the (independent/interdependent) self-concept

Wong and Ahuvia (1998) distinguish between personally and

socially oriented luxury consumers and trace the origins of these orien-

tations to one's self-concept as either independent or inter-dependent

(Markus & Kitayama,1991)—a general individual difference (Aaker,

1999; Oyserman, 2001) particularly relevant in understanding snob and

bandwagon luxury consumption because it centers on people's

propensity to focus (or not) on social connections. Specifically, some

people tend to focus on their internal domain and self-related

goals,emphasizing their unique personaltraits and attributes and

deemphasizing other people (independent self); dissociation from

others, non-conformity, and expression of personal taste take prece-

dence over relational motives. In contrast, others focus on the interper-

sonal domain and the opinions or reactions of others, concerned about

how their external persona appears to society (inter-dependent self);

they emphasize association with similar others and conformity to

in-groups or aspirational groups. Thus, consumers with an independent

self demonstrate a personal orientation in luxury consumption,

focusing on self-expressive goals.Conversely,consumers with an

inter-dependent self care more about the social function of luxury con-

sumption (Ackerman & Chung, 2012).

4.2. Level 2: the narrower traits

This study's preliminary tests identified several narrower personality

traits linked to the self-concept that mediate the self-concept–

consumption relationship.These traits act as the focal mechanisms

that reduce self-concept's influence to the two forms of conspicuous

luxury consumption. Actually, each of the two self-concept orientations

has its collection of subordinate, peripheral traits that can be classified

as individualistically or collectivistically oriented (Hornsey & Jetten,

2004). The independent self emphasizesfreedom of expression

(Dutta-Bergman & Wells, 2002) and uniqueness (Markus & Kitayama,

1991) and thus is related positively to the individualist trait of CNFU.

Conversely, the inter-dependent self emphasizes social relationships

(Dutta-Bergman & Wells, 2002), self–other affiliation, and social com-

parisons (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) and thus is related positively to

the socially oriented trait of CSNI.Status seeking is modeled as an

Note: The three sub-constructs of CCC (creative choice counter-conformity), UCC

(unpopular choice counter-conformity), and AOS (avoidance of similarity) are modeled as

separate factors with their own paths (sub-hypotheses H3b & H3c). For clarity reasons, in the

figure arrows to and from them are subsumed into the overall construct of CNFU .

Fig. 1. A model of conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors and their psychological antecedents. Note: The three sub-constructs of CCC (creative choice counter-conformit

(unpopular choice counter-conformity), and AOS (avoidance of similarity) are modeled as separate factors with their own paths (sub-hypotheses H3b & H3c). For clarity reas

the figure arrows to and from them are subsumed into the overall construct of CNFU.

2149M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

(1) gain a spontaneous, freely elicited perspective on the bandwagon/

snobbish luxury consumer and (2) provide practical insights into the

antecedents identified. The findings enabled a further literature search

for relevant concepts, while screening out others. The resultant model

was presented to the interviewees for additional refinement.From

this process,the consumer self-concept orientation,need for status,

and two mediating traits (consumer susceptibility to normative influ-

ence [CSNI] and consumer need for uniqueness [CNFU]) emerged as

most relevant to the conspicuous consumption of luxuries.

Fig. 1 illustrates the three-level model proposed: (1) self-concept

and status seeking as the original antecedents, (2) CNFU and CSNI as

mediators, and (3) snob and bandwagon luxury consumption as depen-

dent variables. The (independent/interdependent) self-concept refers

to a person's propensity to focus (or not) on social connections and

act in relevant ways.The mediators filter and explain self-concept's

influence on these behaviors.Finally,the outcome variables include

the two conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors.

4.1. Level 1: the (independent/interdependent) self-concept

Wong and Ahuvia (1998) distinguish between personally and

socially oriented luxury consumers and trace the origins of these orien-

tations to one's self-concept as either independent or inter-dependent

(Markus & Kitayama,1991)—a general individual difference (Aaker,

1999; Oyserman, 2001) particularly relevant in understanding snob and

bandwagon luxury consumption because it centers on people's

propensity to focus (or not) on social connections. Specifically, some

people tend to focus on their internal domain and self-related

goals,emphasizing their unique personaltraits and attributes and

deemphasizing other people (independent self); dissociation from

others, non-conformity, and expression of personal taste take prece-

dence over relational motives. In contrast, others focus on the interper-

sonal domain and the opinions or reactions of others, concerned about

how their external persona appears to society (inter-dependent self);

they emphasize association with similar others and conformity to

in-groups or aspirational groups. Thus, consumers with an independent

self demonstrate a personal orientation in luxury consumption,

focusing on self-expressive goals.Conversely,consumers with an

inter-dependent self care more about the social function of luxury con-

sumption (Ackerman & Chung, 2012).

4.2. Level 2: the narrower traits

This study's preliminary tests identified several narrower personality

traits linked to the self-concept that mediate the self-concept–

consumption relationship.These traits act as the focal mechanisms

that reduce self-concept's influence to the two forms of conspicuous

luxury consumption. Actually, each of the two self-concept orientations

has its collection of subordinate, peripheral traits that can be classified

as individualistically or collectivistically oriented (Hornsey & Jetten,

2004). The independent self emphasizesfreedom of expression

(Dutta-Bergman & Wells, 2002) and uniqueness (Markus & Kitayama,

1991) and thus is related positively to the individualist trait of CNFU.

Conversely, the inter-dependent self emphasizes social relationships

(Dutta-Bergman & Wells, 2002), self–other affiliation, and social com-

parisons (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) and thus is related positively to

the socially oriented trait of CSNI.Status seeking is modeled as an

Note: The three sub-constructs of CCC (creative choice counter-conformity), UCC

(unpopular choice counter-conformity), and AOS (avoidance of similarity) are modeled as

separate factors with their own paths (sub-hypotheses H3b & H3c). For clarity reasons, in the

figure arrows to and from them are subsumed into the overall construct of CNFU .

Fig. 1. A model of conspicuous luxury consumption behaviors and their psychological antecedents. Note: The three sub-constructs of CCC (creative choice counter-conformit

(unpopular choice counter-conformity), and AOS (avoidance of similarity) are modeled as separate factors with their own paths (sub-hypotheses H3b & H3c). For clarity reas

the figure arrows to and from them are subsumed into the overall construct of CNFU.

2149M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

exogenous variable, pertaining to all forms of luxury consumption, and

not as a trait focal to the self.

4.3. Level 3: the outcome variables

4.3.1. Bandwagon consumption

Bandwagon consumption occurs when consumers buy certain

categories of luxuries because of their popularity. Popularity serves as

a heuristic (e.g.,popularity = correctness,social approval) because

the majority's numericaldominance conveys the correctness of its

position and is difficult to ignore (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Bandwagon

behavior,with its macro-level origins in majority consumer groups,

celebrities,and fashions (Amaldoss & Jain,2008; Ko,Chun,Song,&

Kim, 2013; Leibenstein, 1950; Vigneron & Johnson, 1999), centers on

goods that carry social approval because these signify success,and

membership in relevant status groups (Belk, 1988). The popularity of

these status groups and the goods they consume serve as signals to

the general public (Han et al.,2010) and trigger further demand for

these luxuries. The behavior of other buyers is especially important in

the case of bandwagon consumption because luxury value is reinforced

and co-created from the complex interactions between the various

social groups,including customers and brand communities (Tynan,

McKechnie, & Chhuon, 2010). In the proposed model, the inter-

dependent self-concept and CSNIcapture the influence ofothers'

behavior on bandwagon consumers (Table 1).Inter-dependent and

norm-obedient consumers observe the luxury consumption by the

majority and jump on the bandwagon.

4.3.2. Snob consumption

In sharp contrast, snob consumption occurs when certain consumers

cease buying a luxury good when many other people begin owning it.

Popularity destroys utility for this group,and demand declines. Such

relative scarcity serves as a heuristic (e.g., scarcity = demonstration of

uniqueness, assertion of independence) that reinforces a luxury good's

desirability to this segment (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Snobbish behav-

ior (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Leibenstein, 1950) favors a luxury's natural,

production, or supply-born scarcity—that is, products that are uncom-

mon, new, exclusive, or not well-known and thus not adopted by the

majority—or connoisseurship requirements beyond the tastes of the

general public (Berger & Ward,2010).The behavior of other luxury

consumers is important in the context of snob consumption because

others destroy luxury value by increasing a good's consumption;

conversely,value is enhanced when the majority does not prefer

the good. In the present model, the anti-conformist nature of the ante-

cedent traits (i.e., the independent self-concept and CNFU) captures

the importance of others' behavior for snobs (Table 1). Although

snobs also care about status, they express this preference alongside a

preference for non-conformity to dissociate themselves from the

mainstream.

5. Hypotheses

The framework in Fig. 1 depicts the hypothesized links among

the key constructs. To avoid redundancies, the focus is on mediating

traits and centers the hypotheses on their relationships to the self

(antecedent) and the two consumption behaviors (consequences).

5.1. Status seeking

Many consumers of luxury goods are status seekers (Han et al.,

2010). Although luxury consumption comprises two variant behaviors

rooted in different antecedents, status seeking is the common denomi-

nator. According to Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn (1999, p. 42), status

seeking defines people who “strive to improve their social standing

through the conspicuous consumption of consumer products that con-

fer and symbolize status both for the individualand surrounding

significant others.”Luxuries confer status (Hanet al., 2010), and thus

consumers acquire,own, use,and display them both to present an

image of what they are like or want to be like (Sirgy, 1985) and to bring

about the kinds of social relationships they desire.Status seekers—

“people who are continually straining to surround themselves with

visible evidence ofthe superior rank they are claiming” (Packard,

1959,p. 5)—use luxuries to support such rank claims (Grossman &

Shapiro, 1988).

With the proliferation of luxuries, however, the ability of heteroge-

neous luxury brands to confer status and the amount or audience

of that status changes.Although status drives luxury consumption,

bandwagon consumers have different status needs than snobs.For

bandwagoners, the good's popularity delivers status, through associa-

tion with or membership in the right status groups (Lascu & Zinkhan,

1999). Brands that are not popular with or unknown to the general,

aspirational public cannot function as effective associative signals of

affluent lifestyles (neither as dissociative signals with less affluent life-

styles). Conversely,well-known and popular luxuries satisfy the

majority's appetite to identify with the rich. Thus, for bandwagoners,

explicit signals of recognition (Berger & Ward, 2010), such as popular

luxury goods,confer status of being associated with the right status

groups (and dissociated from non-status groups).

H1a. Status seeking relates positively to the propensity to engage in

bandwagon consumption of luxury products.

Conversely, snobs have different target audiences and qualitatively

different needs for status because of their independent self. The more

people use a good to claim status, the less status that particular good

confers to snobs.Because uniqueness,non-conformity,and scarcity

matter the most to snobs, popular goods become undesirable and are

viewed as destroying status value.In contrast with the bandwagon

mass, snobs prefer new, exclusive, uncommon, or less-known, unpopu-

lar luxuries. These goods deliver status to snobs through dissociation and

by reestablishing the positional nature of status in the form of scarce and

unique choices appreciated by similar like-minded significant others.

H1b. Status seeking relates positively to the propensity to engage in

snob consumption of luxury products.

5.2. CSNI

This study posits that CSNI is attributable to an inter-dependent self-

concept and reinforces bandwagon luxury consumption. CSNI reflects

“the need to identify or enhance one's image with significant others

through the acquisition and use of products and brands,[and] the

willingness to conform to the expectations of others regarding purchase

decisions” (Bearden, Netemeyer, & Teel, 1989, p. 474). Normative influ-

ences are particularly important for symbolic products such as luxuries,

especially for public consumption (Bearden & Etzel, 1982). Consumers

with greater-than-average susceptibility to norms are prone to using

luxury brands that make a good impression because of value-

expressive and utilitarian normative influence (Park & Lessig, 1977).

Conforming to norms enhances their inter-dependentself in two

ways: value-expressive influence operates through their desire to

enhance their inter-dependent self-image by associating with their

aspirational reference groups; utilitarian influence operates by

complying with expectations of significant others to achieve rewards

or avoid punishments. Consumption of popular luxuries satisfies these

two routes (Lascu & Zinkhan, 1999) because they are recognizable by

the majority, serving as explicit signals of association with the wealthy

(Han et al., 2010). The self is extended (Belk, 1988) to include

these symbolic markers of group membership,and thus the (inter-

dependent) self is enhanced through relational bandwagon luxury con-

sumption; CSNI mediates this process. In addition, CSNI inhibits people

2150 M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

not as a trait focal to the self.

4.3. Level 3: the outcome variables

4.3.1. Bandwagon consumption

Bandwagon consumption occurs when consumers buy certain

categories of luxuries because of their popularity. Popularity serves as

a heuristic (e.g.,popularity = correctness,social approval) because

the majority's numericaldominance conveys the correctness of its

position and is difficult to ignore (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Bandwagon

behavior,with its macro-level origins in majority consumer groups,

celebrities,and fashions (Amaldoss & Jain,2008; Ko,Chun,Song,&

Kim, 2013; Leibenstein, 1950; Vigneron & Johnson, 1999), centers on

goods that carry social approval because these signify success,and

membership in relevant status groups (Belk, 1988). The popularity of

these status groups and the goods they consume serve as signals to

the general public (Han et al.,2010) and trigger further demand for

these luxuries. The behavior of other buyers is especially important in

the case of bandwagon consumption because luxury value is reinforced

and co-created from the complex interactions between the various

social groups,including customers and brand communities (Tynan,

McKechnie, & Chhuon, 2010). In the proposed model, the inter-

dependent self-concept and CSNIcapture the influence ofothers'

behavior on bandwagon consumers (Table 1).Inter-dependent and

norm-obedient consumers observe the luxury consumption by the

majority and jump on the bandwagon.

4.3.2. Snob consumption

In sharp contrast, snob consumption occurs when certain consumers

cease buying a luxury good when many other people begin owning it.

Popularity destroys utility for this group,and demand declines. Such

relative scarcity serves as a heuristic (e.g., scarcity = demonstration of

uniqueness, assertion of independence) that reinforces a luxury good's

desirability to this segment (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Snobbish behav-

ior (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Leibenstein, 1950) favors a luxury's natural,

production, or supply-born scarcity—that is, products that are uncom-

mon, new, exclusive, or not well-known and thus not adopted by the

majority—or connoisseurship requirements beyond the tastes of the

general public (Berger & Ward,2010).The behavior of other luxury

consumers is important in the context of snob consumption because

others destroy luxury value by increasing a good's consumption;

conversely,value is enhanced when the majority does not prefer

the good. In the present model, the anti-conformist nature of the ante-

cedent traits (i.e., the independent self-concept and CNFU) captures

the importance of others' behavior for snobs (Table 1). Although

snobs also care about status, they express this preference alongside a

preference for non-conformity to dissociate themselves from the

mainstream.

5. Hypotheses

The framework in Fig. 1 depicts the hypothesized links among

the key constructs. To avoid redundancies, the focus is on mediating

traits and centers the hypotheses on their relationships to the self

(antecedent) and the two consumption behaviors (consequences).

5.1. Status seeking

Many consumers of luxury goods are status seekers (Han et al.,

2010). Although luxury consumption comprises two variant behaviors

rooted in different antecedents, status seeking is the common denomi-

nator. According to Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn (1999, p. 42), status

seeking defines people who “strive to improve their social standing

through the conspicuous consumption of consumer products that con-

fer and symbolize status both for the individualand surrounding

significant others.”Luxuries confer status (Hanet al., 2010), and thus

consumers acquire,own, use,and display them both to present an

image of what they are like or want to be like (Sirgy, 1985) and to bring

about the kinds of social relationships they desire.Status seekers—

“people who are continually straining to surround themselves with

visible evidence ofthe superior rank they are claiming” (Packard,

1959,p. 5)—use luxuries to support such rank claims (Grossman &

Shapiro, 1988).

With the proliferation of luxuries, however, the ability of heteroge-

neous luxury brands to confer status and the amount or audience

of that status changes.Although status drives luxury consumption,

bandwagon consumers have different status needs than snobs.For

bandwagoners, the good's popularity delivers status, through associa-

tion with or membership in the right status groups (Lascu & Zinkhan,

1999). Brands that are not popular with or unknown to the general,

aspirational public cannot function as effective associative signals of

affluent lifestyles (neither as dissociative signals with less affluent life-

styles). Conversely,well-known and popular luxuries satisfy the

majority's appetite to identify with the rich. Thus, for bandwagoners,

explicit signals of recognition (Berger & Ward, 2010), such as popular

luxury goods,confer status of being associated with the right status

groups (and dissociated from non-status groups).

H1a. Status seeking relates positively to the propensity to engage in

bandwagon consumption of luxury products.

Conversely, snobs have different target audiences and qualitatively

different needs for status because of their independent self. The more

people use a good to claim status, the less status that particular good

confers to snobs.Because uniqueness,non-conformity,and scarcity

matter the most to snobs, popular goods become undesirable and are

viewed as destroying status value.In contrast with the bandwagon

mass, snobs prefer new, exclusive, uncommon, or less-known, unpopu-

lar luxuries. These goods deliver status to snobs through dissociation and

by reestablishing the positional nature of status in the form of scarce and

unique choices appreciated by similar like-minded significant others.

H1b. Status seeking relates positively to the propensity to engage in

snob consumption of luxury products.

5.2. CSNI

This study posits that CSNI is attributable to an inter-dependent self-

concept and reinforces bandwagon luxury consumption. CSNI reflects

“the need to identify or enhance one's image with significant others

through the acquisition and use of products and brands,[and] the

willingness to conform to the expectations of others regarding purchase

decisions” (Bearden, Netemeyer, & Teel, 1989, p. 474). Normative influ-

ences are particularly important for symbolic products such as luxuries,

especially for public consumption (Bearden & Etzel, 1982). Consumers

with greater-than-average susceptibility to norms are prone to using

luxury brands that make a good impression because of value-

expressive and utilitarian normative influence (Park & Lessig, 1977).

Conforming to norms enhances their inter-dependentself in two

ways: value-expressive influence operates through their desire to

enhance their inter-dependent self-image by associating with their

aspirational reference groups; utilitarian influence operates by

complying with expectations of significant others to achieve rewards

or avoid punishments. Consumption of popular luxuries satisfies these

two routes (Lascu & Zinkhan, 1999) because they are recognizable by

the majority, serving as explicit signals of association with the wealthy

(Han et al., 2010). The self is extended (Belk, 1988) to include

these symbolic markers of group membership,and thus the (inter-

dependent) self is enhanced through relational bandwagon luxury con-

sumption; CSNI mediates this process. In addition, CSNI inhibits people

2150 M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

from consuming the types of luxuries that are less popular, scarce, or not

recognizable (i.e., snob luxury consumption).

H2a. The inter-dependent self-concept relates positively to CSNI.

H2b. CSNI relates positively to the propensity to engage in bandwagon

luxury consumption.

H2c. CSNI relates negatively to the propensity to engage in snob luxury

consumption.

5.3. CNFU

This study suggests that CNFU is attributable to an independent

self-conceptand reinforces consumption ofless popular luxuries.

CNFU represents “the trait of pursuing differentness relative to

others through the acquisition, utilization, and disposition of consumer

goods for the purpose of developing and enhancing one's self-image and

social image” (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001, p. 52). CNFU has three

dimensions: (1) creative choice counter-conformity (CCC)—consumers

seek social differentness but still make selections that others consider

good choices; (2) unpopular choice counter-conformity (UCC) —the

consumption of products and brands that deviate from group norms

and may risk social disapproval; and (3) avoidance of similarity (AOS)—

consumers lose interest in or discontinue use ofpossessions that

become commonplace to reestablish differentness.Consumers seek

distinctive luxury products to dissociate themselves from the herd

and enhance their (independent) self-concept through dissociation

from majority groups (Leibenstein,1950). Their independent self-

concept discourages the relational type of bandwagon luxury consump-

tion while encouraging the consumption ofless popular, new, or

unknown luxury brands to establish their differentness; CNFU

mediates and reinforces this process. In addition, CNFU inhibits

people from consuming popular luxuries (bandwagon luxury con-

sumption) because these cannot fulfillthe desired non-conformist

signaling role.

H3a. The independent self-concept relates positively to CNFU.

H3b. CNFU (all three facets) relates positively to the propensity to

engage in snob luxury consumption.

H3c. CNFU (all three facets) relates negatively to the propensity to

engage in bandwagon luxury consumption.

5.4. CSNI and status

Status seeking has a direct relationship to CSNI. Status is a complex

construct whose sources of value can be traced to several personally

and socially meaningful elements, including recognition and esteem

from like-minded groups (Mason, 1984). Research acknowledges the

relationship between status and susceptibility to norms; Phillips and

Zuckerman (2001) demonstrate that status seeking leads to increased

conformity to norms for actors who feel status-insecure and aspire to

secure their position in high-valued groups.Thus, susceptibility to

normative influence is partly rooted in a status attainment goal from

status-prone consumers.To gain status, they must demonstrate

conformity to the norms defining membership in their target group:

H4. Status seeking relates positively to CSNI.

6. Method

6.1. Design and procedure

A drop-and-collect survey was used to collect data from a probability

sample of 431 actual consumers of luxury goods in London. A

multi-stage cluster sampling design with respondents from areas

representing average and higher-than-average income areas was

used. Respondents were qualified by screening questions that ensured

that they were consumers of luxuries. Of the respondents, 47.3% were

men and 53.7% women,ranging from 18 to 82 years (M = 36.5),

mostly university educated with yearly income from £41,000 to

£60,000.

Respondents completed the questionnaire starting from the

dependent variables that appeared before the trait sections in the

survey.Specifically,they rated how likely they were to purchase/

use these products, assuming that money is no object. In line

with prior research (Dubois & Paternault, 1995), this assumption

intended to create a free-choice environment based on individual

variable effects only by eliminating possible financial bias. Then,

respondents completed the trait sections and demographic/control

measures.

Drop-and-collect surveys produce response rates up to 90% (Loveloc

Stiff, Cullwick, & Kaufman, 1976). 625 questionnaires were distributed a

various days of the week to obtain a broad representation. On week-

days,distribution occurred in the evening to reduce non-response

error (when most people are home),and on weekends, distribution

took place during the entire day.In total, 431 usable surveys were

returned (69% response).

6.2. Measures

Self-concept orientation was measured with Singelis's (1994) scale

(example items include “I am comfortable with being singled out for

praise or rewards” and “If someone who is close to me fails,I feel

responsible”), status seeking with Eastman et al.'s (1999) status con-

sumption scale (“I would buy a product just because it has status”),

CSNI with Bearden et al.'s (1989) scale (“I rarely buy the latest fashion

until I am sure my friends approve of them”),and CNFU with Ruvio,

Shoham, and Brencic (2008) (“I dislike products or brands that are cus-

tomarily bought by everyone”).CNFU was modeled as three factors

(CCC, UCC, and AOS) to better capture how each dimension contributes

to the results.

Because no measures exist for snob/bandwagon consumption,a

scale was developed for the purpose of the study, with concrete descrip

tions of popular/scarce luxury products (contingent on the behavior of

other luxury consumers). Following (1) theoretical considerations on

snob and bandwagon consumption (Amaldoss & Jain,2008; Corneo

& Jeanne,1997; Leibenstein,1950; Vigneron & Johnson,1999) and

(2) discussions with expert judges (senior managers with lengthy expe-

rience in various luxury industries), a scale with indicators describing

scarce/unpopular watches was developed for the snob effect, and one

with indicators describing popular watches was created for the band-

wagon effect (descriptions of luxury watches were used following

established research practices—De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002; Hudders &

Pandelaere, 2011—and experts' advice). Specifically, according to extan

literature and calibration by experts,the criteria for inclusion of the

products in the scale were various factors related to both the supply

and demand side (i.e., limited supply/production or limited consumer

preference for the snob effect, such as a luxury watch “that only a few

people own,” “is of limited production,” or “is recognized by a small

circle of people”; higher production volume or larger/widespread con-

sumer preference for the bandwagon effect,such as “a very popular

and fashionable luxury watch,” “worn by many celebrities,” and “chosen

by most people”).

An extensive pretesting procedure was followed: three marketing

academics and six managers of luxuries qualitatively evaluated the

initial pool of items. Several focus groups and interviews further refined

the scales,using behavior coding and cognitive pretesting.Finally,

the questionnaire was pilot-tested on a convenience sample of 103

respondents.

2151M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

recognizable (i.e., snob luxury consumption).

H2a. The inter-dependent self-concept relates positively to CSNI.

H2b. CSNI relates positively to the propensity to engage in bandwagon

luxury consumption.

H2c. CSNI relates negatively to the propensity to engage in snob luxury

consumption.

5.3. CNFU

This study suggests that CNFU is attributable to an independent

self-conceptand reinforces consumption ofless popular luxuries.

CNFU represents “the trait of pursuing differentness relative to

others through the acquisition, utilization, and disposition of consumer

goods for the purpose of developing and enhancing one's self-image and

social image” (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001, p. 52). CNFU has three

dimensions: (1) creative choice counter-conformity (CCC)—consumers

seek social differentness but still make selections that others consider

good choices; (2) unpopular choice counter-conformity (UCC) —the

consumption of products and brands that deviate from group norms

and may risk social disapproval; and (3) avoidance of similarity (AOS)—

consumers lose interest in or discontinue use ofpossessions that

become commonplace to reestablish differentness.Consumers seek

distinctive luxury products to dissociate themselves from the herd

and enhance their (independent) self-concept through dissociation

from majority groups (Leibenstein,1950). Their independent self-

concept discourages the relational type of bandwagon luxury consump-

tion while encouraging the consumption ofless popular, new, or

unknown luxury brands to establish their differentness; CNFU

mediates and reinforces this process. In addition, CNFU inhibits

people from consuming popular luxuries (bandwagon luxury con-

sumption) because these cannot fulfillthe desired non-conformist

signaling role.

H3a. The independent self-concept relates positively to CNFU.

H3b. CNFU (all three facets) relates positively to the propensity to

engage in snob luxury consumption.

H3c. CNFU (all three facets) relates negatively to the propensity to

engage in bandwagon luxury consumption.

5.4. CSNI and status

Status seeking has a direct relationship to CSNI. Status is a complex

construct whose sources of value can be traced to several personally

and socially meaningful elements, including recognition and esteem

from like-minded groups (Mason, 1984). Research acknowledges the

relationship between status and susceptibility to norms; Phillips and

Zuckerman (2001) demonstrate that status seeking leads to increased

conformity to norms for actors who feel status-insecure and aspire to

secure their position in high-valued groups.Thus, susceptibility to

normative influence is partly rooted in a status attainment goal from

status-prone consumers.To gain status, they must demonstrate

conformity to the norms defining membership in their target group:

H4. Status seeking relates positively to CSNI.

6. Method

6.1. Design and procedure

A drop-and-collect survey was used to collect data from a probability

sample of 431 actual consumers of luxury goods in London. A

multi-stage cluster sampling design with respondents from areas

representing average and higher-than-average income areas was

used. Respondents were qualified by screening questions that ensured

that they were consumers of luxuries. Of the respondents, 47.3% were

men and 53.7% women,ranging from 18 to 82 years (M = 36.5),

mostly university educated with yearly income from £41,000 to

£60,000.

Respondents completed the questionnaire starting from the

dependent variables that appeared before the trait sections in the

survey.Specifically,they rated how likely they were to purchase/

use these products, assuming that money is no object. In line

with prior research (Dubois & Paternault, 1995), this assumption

intended to create a free-choice environment based on individual

variable effects only by eliminating possible financial bias. Then,

respondents completed the trait sections and demographic/control

measures.

Drop-and-collect surveys produce response rates up to 90% (Loveloc

Stiff, Cullwick, & Kaufman, 1976). 625 questionnaires were distributed a

various days of the week to obtain a broad representation. On week-

days,distribution occurred in the evening to reduce non-response

error (when most people are home),and on weekends, distribution

took place during the entire day.In total, 431 usable surveys were

returned (69% response).

6.2. Measures

Self-concept orientation was measured with Singelis's (1994) scale

(example items include “I am comfortable with being singled out for

praise or rewards” and “If someone who is close to me fails,I feel

responsible”), status seeking with Eastman et al.'s (1999) status con-

sumption scale (“I would buy a product just because it has status”),

CSNI with Bearden et al.'s (1989) scale (“I rarely buy the latest fashion

until I am sure my friends approve of them”),and CNFU with Ruvio,

Shoham, and Brencic (2008) (“I dislike products or brands that are cus-

tomarily bought by everyone”).CNFU was modeled as three factors

(CCC, UCC, and AOS) to better capture how each dimension contributes

to the results.

Because no measures exist for snob/bandwagon consumption,a

scale was developed for the purpose of the study, with concrete descrip

tions of popular/scarce luxury products (contingent on the behavior of

other luxury consumers). Following (1) theoretical considerations on

snob and bandwagon consumption (Amaldoss & Jain,2008; Corneo

& Jeanne,1997; Leibenstein,1950; Vigneron & Johnson,1999) and

(2) discussions with expert judges (senior managers with lengthy expe-

rience in various luxury industries), a scale with indicators describing

scarce/unpopular watches was developed for the snob effect, and one

with indicators describing popular watches was created for the band-

wagon effect (descriptions of luxury watches were used following

established research practices—De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002; Hudders &

Pandelaere, 2011—and experts' advice). Specifically, according to extan

literature and calibration by experts,the criteria for inclusion of the

products in the scale were various factors related to both the supply

and demand side (i.e., limited supply/production or limited consumer

preference for the snob effect, such as a luxury watch “that only a few

people own,” “is of limited production,” or “is recognized by a small

circle of people”; higher production volume or larger/widespread con-

sumer preference for the bandwagon effect,such as “a very popular

and fashionable luxury watch,” “worn by many celebrities,” and “chosen

by most people”).

An extensive pretesting procedure was followed: three marketing

academics and six managers of luxuries qualitatively evaluated the

initial pool of items. Several focus groups and interviews further refined

the scales,using behavior coding and cognitive pretesting.Finally,

the questionnaire was pilot-tested on a convenience sample of 103

respondents.

2151M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

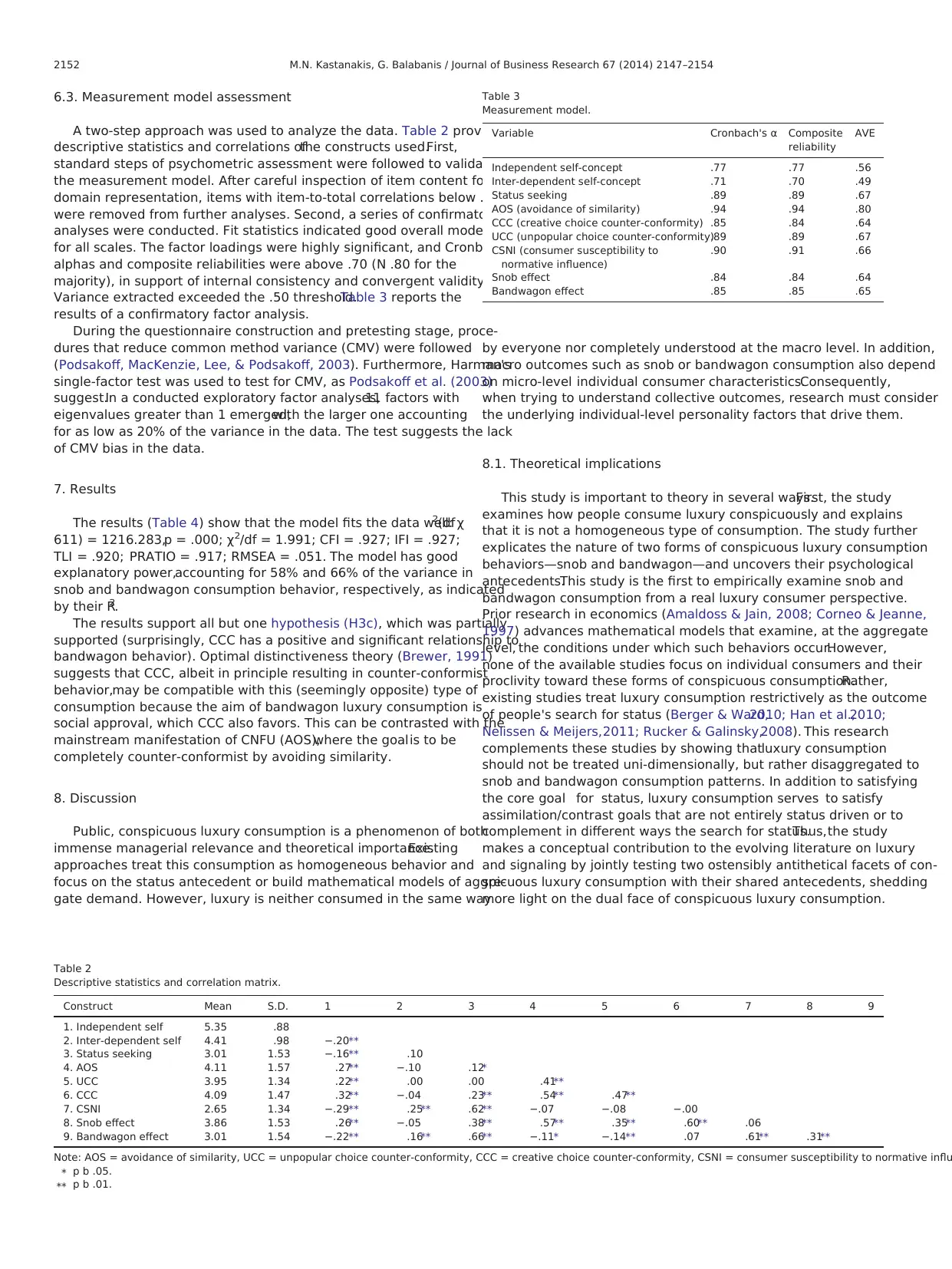

6.3. Measurement model assessment

A two-step approach was used to analyze the data. Table 2 provides

descriptive statistics and correlations ofthe constructs used.First,

standard steps of psychometric assessment were followed to validate

the measurement model. After careful inspection of item content for

domain representation, items with item-to-total correlations below .40

were removed from further analyses. Second, a series of confirmatory

analyses were conducted. Fit statistics indicated good overall model fit

for all scales. The factor loadings were highly significant, and Cronbach's

alphas and composite reliabilities were above .70 (N .80 for the

majority), in support of internal consistency and convergent validity.

Variance extracted exceeded the .50 threshold.Table 3 reports the

results of a confirmatory factor analysis.

During the questionnaire construction and pretesting stage, proce-

dures that reduce common method variance (CMV) were followed

(Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Furthermore, Harman's

single-factor test was used to test for CMV, as Podsakoff et al. (2003)

suggest.In a conducted exploratory factor analyses,11 factors with

eigenvalues greater than 1 emerged,with the larger one accounting

for as low as 20% of the variance in the data. The test suggests the lack

of CMV bias in the data.

7. Results

The results (Table 4) show that the model fits the data well: χ2(df

611) = 1216.283,p = .000; χ 2/df = 1.991; CFI = .927; IFI = .927;

TLI = .920; PRATIO = .917; RMSEA = .051. The model has good

explanatory power,accounting for 58% and 66% of the variance in

snob and bandwagon consumption behavior, respectively, as indicated

by their R2.

The results support all but one hypothesis (H3c), which was partially

supported (surprisingly, CCC has a positive and significant relationship to

bandwagon behavior). Optimal distinctiveness theory (Brewer, 1991)

suggests that CCC, albeit in principle resulting in counter-conformist

behavior,may be compatible with this (seemingly opposite) type of

consumption because the aim of bandwagon luxury consumption is

social approval, which CCC also favors. This can be contrasted with the

mainstream manifestation of CNFU (AOS),where the goalis to be

completely counter-conformist by avoiding similarity.

8. Discussion

Public, conspicuous luxury consumption is a phenomenon of both

immense managerial relevance and theoretical importance.Existing

approaches treat this consumption as homogeneous behavior and

focus on the status antecedent or build mathematical models of aggre-

gate demand. However, luxury is neither consumed in the same way

by everyone nor completely understood at the macro level. In addition,

macro outcomes such as snob or bandwagon consumption also depend

on micro-level individual consumer characteristics.Consequently,

when trying to understand collective outcomes, research must consider

the underlying individual-level personality factors that drive them.

8.1. Theoretical implications

This study is important to theory in several ways.First, the study

examines how people consume luxury conspicuously and explains

that it is not a homogeneous type of consumption. The study further

explicates the nature of two forms of conspicuous luxury consumption

behaviors—snob and bandwagon—and uncovers their psychological

antecedents.This study is the first to empirically examine snob and

bandwagon consumption from a real luxury consumer perspective.

Prior research in economics (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Corneo & Jeanne,

1997) advances mathematical models that examine, at the aggregate

level, the conditions under which such behaviors occur.However,

none of the available studies focus on individual consumers and their

proclivity toward these forms of conspicuous consumption.Rather,

existing studies treat luxury consumption restrictively as the outcome

of people's search for status (Berger & Ward,2010; Han et al.,2010;

Nelissen & Meijers,2011; Rucker & Galinsky,2008). This research

complements these studies by showing thatluxury consumption

should not be treated uni-dimensionally, but rather disaggregated to

snob and bandwagon consumption patterns. In addition to satisfying

the core goal for status, luxury consumption serves to satisfy

assimilation/contrast goals that are not entirely status driven or to

complement in different ways the search for status.Thus,the study

makes a conceptual contribution to the evolving literature on luxury

and signaling by jointly testing two ostensibly antithetical facets of con-

spicuous luxury consumption with their shared antecedents, shedding

more light on the dual face of conspicuous luxury consumption.

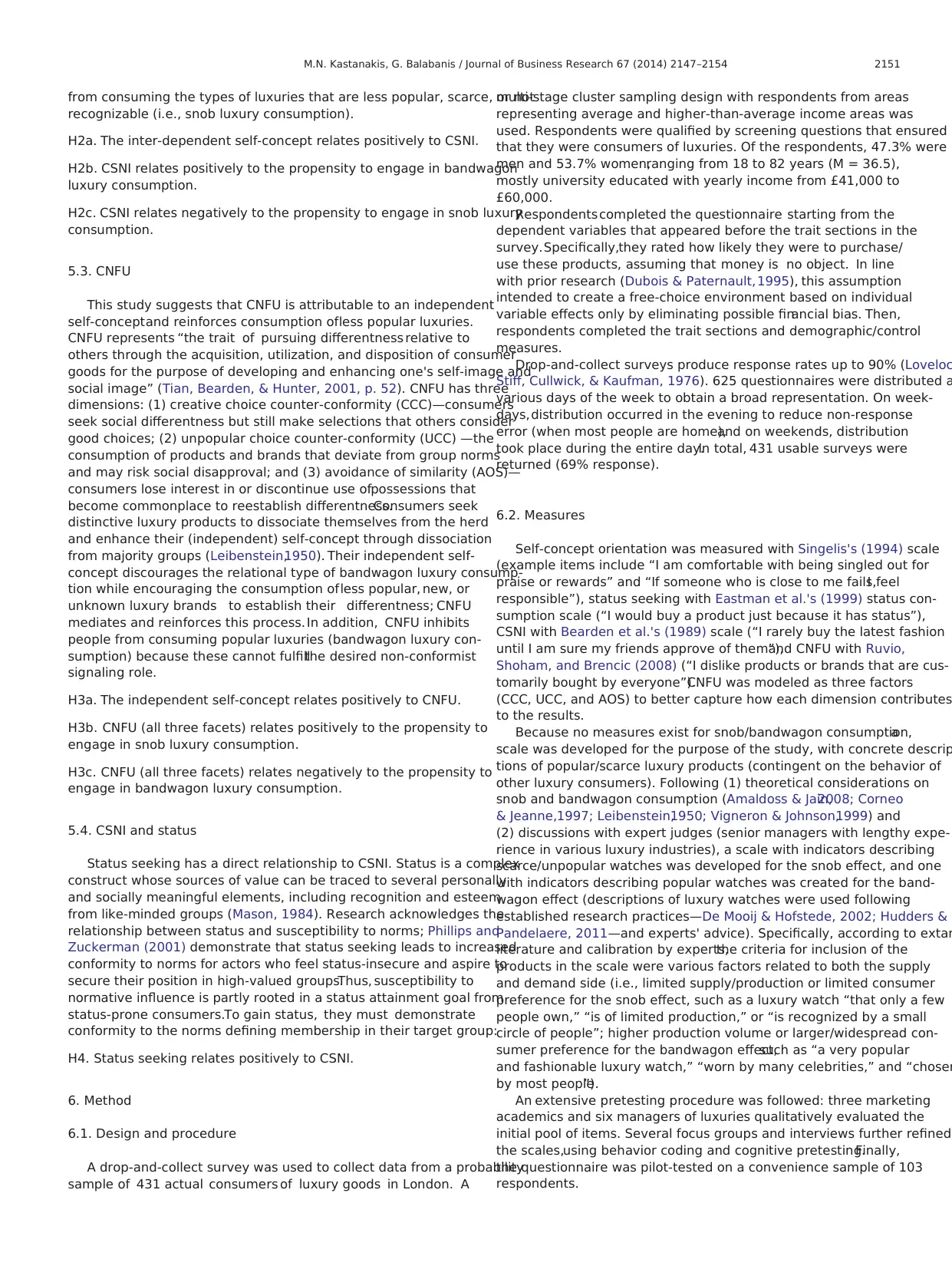

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Construct Mean S.D. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1. Independent self 5.35 .88

2. Inter-dependent self 4.41 .98 −.20⁎⁎

3. Status seeking 3.01 1.53 −.16⁎⁎ .10

4. AOS 4.11 1.57 .27⁎⁎ −.10 .12⁎

5. UCC 3.95 1.34 .22⁎⁎ .00 .00 .41⁎⁎

6. CCC 4.09 1.47 .32⁎⁎ −.04 .23⁎⁎ .54⁎⁎ .47⁎⁎

7. CSNI 2.65 1.34 −.29⁎⁎ .25⁎⁎ .62⁎⁎ −.07 −.08 −.00

8. Snob effect 3.86 1.53 .26⁎⁎ −.05 .38⁎⁎ .57⁎⁎ .35⁎⁎ .60⁎⁎ .06

9. Bandwagon effect 3.01 1.54 −.22⁎⁎ .16⁎⁎ .66⁎⁎ −.11⁎ −.14⁎⁎ .07 .61⁎⁎ .31⁎⁎

Note: AOS = avoidance of similarity, UCC = unpopular choice counter-conformity, CCC = creative choice counter-conformity, CSNI = consumer susceptibility to normative influ

⁎ p b .05.

⁎⁎ p b .01.

Table 3

Measurement model.

Variable Cronbach's α Composite

reliability

AVE

Independent self-concept .77 .77 .56

Inter-dependent self-concept .71 .70 .49

Status seeking .89 .89 .67

AOS (avoidance of similarity) .94 .94 .80

CCC (creative choice counter-conformity) .85 .84 .64

UCC (unpopular choice counter-conformity).89 .89 .67

CSNI (consumer susceptibility to

normative influence)

.90 .91 .66

Snob effect .84 .84 .64

Bandwagon effect .85 .85 .65

2152 M.N. Kastanakis, G. Balabanis / Journal of Business Research 67 (2014) 2147–2154

A two-step approach was used to analyze the data. Table 2 provides

descriptive statistics and correlations ofthe constructs used.First,

standard steps of psychometric assessment were followed to validate

the measurement model. After careful inspection of item content for

domain representation, items with item-to-total correlations below .40

were removed from further analyses. Second, a series of confirmatory

analyses were conducted. Fit statistics indicated good overall model fit

for all scales. The factor loadings were highly significant, and Cronbach's

alphas and composite reliabilities were above .70 (N .80 for the

majority), in support of internal consistency and convergent validity.

Variance extracted exceeded the .50 threshold.Table 3 reports the

results of a confirmatory factor analysis.

During the questionnaire construction and pretesting stage, proce-

dures that reduce common method variance (CMV) were followed

(Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Furthermore, Harman's

single-factor test was used to test for CMV, as Podsakoff et al. (2003)

suggest.In a conducted exploratory factor analyses,11 factors with

eigenvalues greater than 1 emerged,with the larger one accounting

for as low as 20% of the variance in the data. The test suggests the lack

of CMV bias in the data.

7. Results

The results (Table 4) show that the model fits the data well: χ2(df

611) = 1216.283,p = .000; χ 2/df = 1.991; CFI = .927; IFI = .927;

TLI = .920; PRATIO = .917; RMSEA = .051. The model has good

explanatory power,accounting for 58% and 66% of the variance in

snob and bandwagon consumption behavior, respectively, as indicated

by their R2.

The results support all but one hypothesis (H3c), which was partially

supported (surprisingly, CCC has a positive and significant relationship to

bandwagon behavior). Optimal distinctiveness theory (Brewer, 1991)

suggests that CCC, albeit in principle resulting in counter-conformist

behavior,may be compatible with this (seemingly opposite) type of

consumption because the aim of bandwagon luxury consumption is

social approval, which CCC also favors. This can be contrasted with the

mainstream manifestation of CNFU (AOS),where the goalis to be

completely counter-conformist by avoiding similarity.

8. Discussion

Public, conspicuous luxury consumption is a phenomenon of both

immense managerial relevance and theoretical importance.Existing

approaches treat this consumption as homogeneous behavior and

focus on the status antecedent or build mathematical models of aggre-

gate demand. However, luxury is neither consumed in the same way

by everyone nor completely understood at the macro level. In addition,

macro outcomes such as snob or bandwagon consumption also depend

on micro-level individual consumer characteristics.Consequently,