Postgraduate Medical Education: Clinical Leadership Development Review

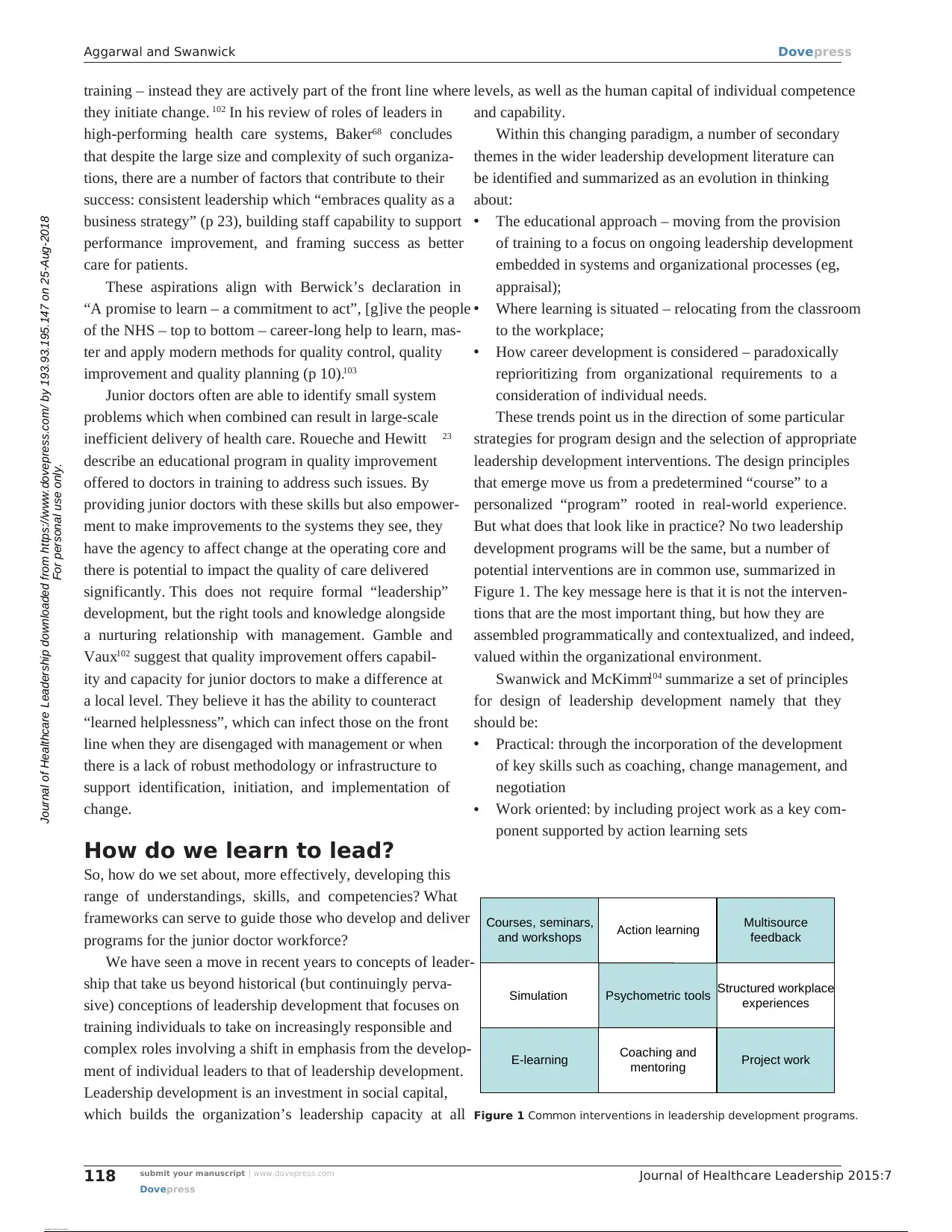

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/20

|14

|13638

|30

Report

AI Summary

This report, drawn from the Journal of Healthcare Leadership, focuses on clinical leadership development within postgraduate medical education and training in the UK National Health Service (NHS). It explores the significance of clinical leadership in improving healthcare quality and efficiency, particularly emphasizing the role of junior doctors as a crucial resource for initiating and championing improvements. The paper reviews various leadership theories and interventions, including competency frameworks and shared learning approaches, highlighting the shift from developing individual leaders to fostering a more inclusive, 'leader-ful' organizational model. It examines the historical context of postgraduate medical training, including the evolution of curricula and the impact of working time regulations. The report underscores the importance of engaging junior doctors in healthcare provision and the need for leadership development to ensure the future generation of healthcare professionals are well-equipped to drive system improvements. The study also considers the challenges and dynamics within healthcare organizations, emphasizing the need for cooperation and support from clinicians at all levels to facilitate meaningful change. The document highlights the evolution of postgraduate medical training and the shift towards emphasizing non-technical skills and generic competencies, including leadership, research, and education.

© 2015 Aggarwal and Swanwick. This work is published by Dove Medical Press Limited, and licensed under Creativ

License. The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Non-commer

permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. Permissions beyond the scope of the Licen

how to request permission may be found at: http://www.dovepress.com/permissions.php

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7 109–122

Journal of Healthcare Leadership Dovepress

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

109

R e v i e w

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S69330

Clinical leadership development in postgradu

medical education and training: policy, strate

and delivery in the UK National Health Servic

Reena Aggarwal1,2

Tim Swanwick2

1women’s Health, whittington Health,

London, UK;2Health education

england, North Central and east

London, London, UK

Correspondence: Reena Aggarwal

women’s Health, whittington Health,

Magdala Avenue, London N19 5NF, UK

Tel +44 7799 664 215

email raggarwal73@doctors.org.uk

Abstract:Achieving high quality health care against a background of continual change,

increasing demand, and shrinking financial resource is a major challenge. However, there is

significant international evidence that when clinicians use their voices and values to engage

with system delivery, operational efficiency and care outcomes are improved. In the UK

National Health Service, the traditional divide between doctors and managers is being bridged,

as clinical leadership is now foregrounded as an important organizational priority. There are

60,000 doctors in postgraduate training (junior doctors) in the UK who provide the majority

of front-line patient care and form an “operating core” of most health care organizations. This

group of doctors is therefore seen as an important resource in initiating, championing, and

delivering improvement in the quality of patient care. This paper provides a brief overview

of leadership theories and constructs that have been used to develop a raft of interventions to

develop leadership capability among junior doctors. We explore some of the approaches used,

including competency frameworks, talent management, shared learning, clinical fellowships,

and quality improvement. A new paradigm is identified as necessary to make a difference at a

local level, which moves learning and leadership away from developing “leaders”, to a more

inclusive model of developing relationships between individuals within organizations. This

shifts the emphasis from the development of a “heroic” individual leader to a more distributed

model, where organizations are “leader-ful” and not just “well led” and leadership is centered

on a shared vision owned by whole teams working on the frontline.

Keywords:National Health Service, junior doctors, quality improvement, management, health

care, leadership, fellowships, mentoring

Introduction

Health care has both scientific and social dimensions and is also the source of immense

political concern. Vast sums of gross domestic product are spent on health,1 the orga-

nization of complex systems of health care provision is difficult, and governments are

increasingly judged on their ability to deliver high value services.2 In the UK, a National

Health Service (NHS) employs over 1.5 million people with a budget of around £115

billion under the supervision of its departments of health. Notwithstanding its size,

the NHS appears to be an effective system. In 2014, a Commonwealth Fund report

concluded that in comparison with the health care systems of ten other countries

(Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden,

Switzerland, and USA), the NHS was the most impressive overall, although lagging

behind on health outcomes.3 By comparison, the USA has the most expensive health

care system, yet ranked last in measures of health outcomes, quality, and efficiency.

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

License. The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Non-commer

permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. Permissions beyond the scope of the Licen

how to request permission may be found at: http://www.dovepress.com/permissions.php

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7 109–122

Journal of Healthcare Leadership Dovepress

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

109

R e v i e w

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S69330

Clinical leadership development in postgradu

medical education and training: policy, strate

and delivery in the UK National Health Servic

Reena Aggarwal1,2

Tim Swanwick2

1women’s Health, whittington Health,

London, UK;2Health education

england, North Central and east

London, London, UK

Correspondence: Reena Aggarwal

women’s Health, whittington Health,

Magdala Avenue, London N19 5NF, UK

Tel +44 7799 664 215

email raggarwal73@doctors.org.uk

Abstract:Achieving high quality health care against a background of continual change,

increasing demand, and shrinking financial resource is a major challenge. However, there is

significant international evidence that when clinicians use their voices and values to engage

with system delivery, operational efficiency and care outcomes are improved. In the UK

National Health Service, the traditional divide between doctors and managers is being bridged,

as clinical leadership is now foregrounded as an important organizational priority. There are

60,000 doctors in postgraduate training (junior doctors) in the UK who provide the majority

of front-line patient care and form an “operating core” of most health care organizations. This

group of doctors is therefore seen as an important resource in initiating, championing, and

delivering improvement in the quality of patient care. This paper provides a brief overview

of leadership theories and constructs that have been used to develop a raft of interventions to

develop leadership capability among junior doctors. We explore some of the approaches used,

including competency frameworks, talent management, shared learning, clinical fellowships,

and quality improvement. A new paradigm is identified as necessary to make a difference at a

local level, which moves learning and leadership away from developing “leaders”, to a more

inclusive model of developing relationships between individuals within organizations. This

shifts the emphasis from the development of a “heroic” individual leader to a more distributed

model, where organizations are “leader-ful” and not just “well led” and leadership is centered

on a shared vision owned by whole teams working on the frontline.

Keywords:National Health Service, junior doctors, quality improvement, management, health

care, leadership, fellowships, mentoring

Introduction

Health care has both scientific and social dimensions and is also the source of immense

political concern. Vast sums of gross domestic product are spent on health,1 the orga-

nization of complex systems of health care provision is difficult, and governments are

increasingly judged on their ability to deliver high value services.2 In the UK, a National

Health Service (NHS) employs over 1.5 million people with a budget of around £115

billion under the supervision of its departments of health. Notwithstanding its size,

the NHS appears to be an effective system. In 2014, a Commonwealth Fund report

concluded that in comparison with the health care systems of ten other countries

(Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden,

Switzerland, and USA), the NHS was the most impressive overall, although lagging

behind on health outcomes.3 By comparison, the USA has the most expensive health

care system, yet ranked last in measures of health outcomes, quality, and efficiency.

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

110

Aggarwal and Swanwick

Despite the UK’s high-ranking, significant shortcomings

exist in the quality and availability of care, as highlighted by

a recent public inquiry by Sir Robert Francis. The “Francis

Report” detailed catastrophic failings in patient care occur-

ring over a number of years in one particular NHS trust. Sig-

nificantly, the report also identified a “learned helplessness”

among medical and nursing staff, resulting in disengagement

of health care professionals from management.4 Subsequent

reviews of other NHS provider organizations have unearthed

similar problems with a focus on targets and efficiency sav-

ings dominating board agendas and organizations losing sight

of the patient. This has been viewed widely as something

that needs fixing, and a significant element in the solution

has been to invite clinicians to engage with system delivery,

to use their voices and values in improving quality and

productivity, while simultaneously controlling the costs of

service provision.4–6

Clinicians, doctors in particular, have considerable influ-

ence in relation to health care expenditure, occupy the moral

high ground of patient advocacy, and have a large measure

of autonomy by virtue of their training and professional

knowledge. Drawing upon the organizational theories of

Mintzberg, health care organizations function as “profes-

sional bureaucracies” in which the continually evolving

expertise of skilled and knowledgeable workers exercises

a high degree of degree of control over the delivery of

services.7 In a professional organization, workers’ autonomy

is regulated by external professional bodies, contrasting

with a “machine bureaucracy”, where the organization itself

designs and enforces standards through strong line manage-

ment structures. Professional bureaucracies create an inverted

power structure, where frontline staff have greater influence

over daily decision-making than those who, through formal

positions of authority, are responsible for managing the ser-

vice.5,8 In such a system, the ability of managers to influence

clinical decision-making is constrained since clinical profes-

sionals form the “operating core” of health organizations,

thereby controlling the means of production.9

According to Ham and Dickenson,10 this has three signifi-

cant implications for health care organizations: key leader-

ship roles are played by professionals; leadership is dispersed

or distributed among staff and not limited to individuals in

formal managerial roles, and the system requires collective

leadership, ie, teams that bring together leaders at different

levels. In understanding the relationships and power dynam-

ics within health care organizations, it becomes evident that

significant clinical change is impossible without the coop-

eration and support of clinicians at all levels. The operating

core of most health care organizations consists of a large

body of doctors in postgraduate training, resolutely engaged

at the front line of patient care. “Junior” doctors, then, are

the perfect tool for initiating, championing, and delivering

change and improvement in the quality of care.

Postgraduate medical training in

the UK

There are around 60,000 junior doctors (In the UK, the term

“junior doctor” is used to describe a qualified doctor who has

yet to be placed on the General Medical Council’s special-

ist or general practice register. Junior doctors are normally

“trainees” enrolled in a postgraduate training program and

work under the supervision of “seniors”, usually registered

consultant specialists or general practitioners) in postgradu-

ate training programs in the UK, with multiple agencies

responsible for different aspects of the training. Setting and

monitoring professional standards is primarily a role of the

General Medical Council and Royal Colleges, funding is

controlled centrally from the relevant Department of Health

and dispersed via various bodies such as Health Education

England or NHS Education for Scotland, and those delivering

the training are situated in a variety of a community, inte-

grated, and hospital settings. Unlike undergraduate students,

postgraduate trainees do not have a university structure to

manage their placements, programs, or the progression of

individuals. Historically therefore, a “deanery” has sat as

“an organization in the middle”, providing an umbrella for

postgraduate medical education and training, controlling the

funding flows, ensuring training is delivered to curricular

specifications, and that quality standards are monitored and

maintained.

There is broad agreement that the prime purpose of

postgraduate medical training is “… to ensure that special-

ized doctors competently address the medical needs of the

community” (p 3),11 an aim reiterated in a recent report on

the future of postgraduate medical education and training,

The Shape of Training. 12 Indeed, training structures in the

UK have been in evolution since the publication, in the

1990s, of the Calman report.13 Predominantly concerned with

improving specialist hospital training, this report resulted

in the introduction of specialist registrar posts with explicit

curricula, regular assessments of progress, and time-limited

specialist training. Alongside this development was the

implementation of European Working Time Directive –

later, European Working Time Regulations – restricting

junior doctors to a maximum of 58 hours per week by 2004,

with a further reduction to 48 hours by 2009. Many doctors

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

110

Aggarwal and Swanwick

Despite the UK’s high-ranking, significant shortcomings

exist in the quality and availability of care, as highlighted by

a recent public inquiry by Sir Robert Francis. The “Francis

Report” detailed catastrophic failings in patient care occur-

ring over a number of years in one particular NHS trust. Sig-

nificantly, the report also identified a “learned helplessness”

among medical and nursing staff, resulting in disengagement

of health care professionals from management.4 Subsequent

reviews of other NHS provider organizations have unearthed

similar problems with a focus on targets and efficiency sav-

ings dominating board agendas and organizations losing sight

of the patient. This has been viewed widely as something

that needs fixing, and a significant element in the solution

has been to invite clinicians to engage with system delivery,

to use their voices and values in improving quality and

productivity, while simultaneously controlling the costs of

service provision.4–6

Clinicians, doctors in particular, have considerable influ-

ence in relation to health care expenditure, occupy the moral

high ground of patient advocacy, and have a large measure

of autonomy by virtue of their training and professional

knowledge. Drawing upon the organizational theories of

Mintzberg, health care organizations function as “profes-

sional bureaucracies” in which the continually evolving

expertise of skilled and knowledgeable workers exercises

a high degree of degree of control over the delivery of

services.7 In a professional organization, workers’ autonomy

is regulated by external professional bodies, contrasting

with a “machine bureaucracy”, where the organization itself

designs and enforces standards through strong line manage-

ment structures. Professional bureaucracies create an inverted

power structure, where frontline staff have greater influence

over daily decision-making than those who, through formal

positions of authority, are responsible for managing the ser-

vice.5,8 In such a system, the ability of managers to influence

clinical decision-making is constrained since clinical profes-

sionals form the “operating core” of health organizations,

thereby controlling the means of production.9

According to Ham and Dickenson,10 this has three signifi-

cant implications for health care organizations: key leader-

ship roles are played by professionals; leadership is dispersed

or distributed among staff and not limited to individuals in

formal managerial roles, and the system requires collective

leadership, ie, teams that bring together leaders at different

levels. In understanding the relationships and power dynam-

ics within health care organizations, it becomes evident that

significant clinical change is impossible without the coop-

eration and support of clinicians at all levels. The operating

core of most health care organizations consists of a large

body of doctors in postgraduate training, resolutely engaged

at the front line of patient care. “Junior” doctors, then, are

the perfect tool for initiating, championing, and delivering

change and improvement in the quality of care.

Postgraduate medical training in

the UK

There are around 60,000 junior doctors (In the UK, the term

“junior doctor” is used to describe a qualified doctor who has

yet to be placed on the General Medical Council’s special-

ist or general practice register. Junior doctors are normally

“trainees” enrolled in a postgraduate training program and

work under the supervision of “seniors”, usually registered

consultant specialists or general practitioners) in postgradu-

ate training programs in the UK, with multiple agencies

responsible for different aspects of the training. Setting and

monitoring professional standards is primarily a role of the

General Medical Council and Royal Colleges, funding is

controlled centrally from the relevant Department of Health

and dispersed via various bodies such as Health Education

England or NHS Education for Scotland, and those delivering

the training are situated in a variety of a community, inte-

grated, and hospital settings. Unlike undergraduate students,

postgraduate trainees do not have a university structure to

manage their placements, programs, or the progression of

individuals. Historically therefore, a “deanery” has sat as

“an organization in the middle”, providing an umbrella for

postgraduate medical education and training, controlling the

funding flows, ensuring training is delivered to curricular

specifications, and that quality standards are monitored and

maintained.

There is broad agreement that the prime purpose of

postgraduate medical training is “… to ensure that special-

ized doctors competently address the medical needs of the

community” (p 3),11 an aim reiterated in a recent report on

the future of postgraduate medical education and training,

The Shape of Training. 12 Indeed, training structures in the

UK have been in evolution since the publication, in the

1990s, of the Calman report.13 Predominantly concerned with

improving specialist hospital training, this report resulted

in the introduction of specialist registrar posts with explicit

curricula, regular assessments of progress, and time-limited

specialist training. Alongside this development was the

implementation of European Working Time Directive –

later, European Working Time Regulations – restricting

junior doctors to a maximum of 58 hours per week by 2004,

with a further reduction to 48 hours by 2009. Many doctors

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

111

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

traditionally worked much longer hours, and these changes

reduced the degree to which the NHS could rely on doc-

tors in training for service delivery and, correspondingly,

decreased the amount of time doctors would have available

for training.

In order to address these issues, postgraduate training was

further reformed – under the banner of “Modernising Medical

Careers” – predominantly to accelerate the production of

competent specialists. “Modernising Medical Careers” led to

the creation of a 2-year foundation program, followed by basic

specialist training in a broad specialty grouping (eg, core med-

ical training), and then higher specialist training in a specific

specialty (eg, neurology).14 The aim was to provide doctors

with wide initial breadth of training, which would ultimately

be shorter by virtue of a more structured program later on.15

Explicit curricula for each specialty (there are 67 in the UK

with 35 subspecialties) were introduced alongside a wholesale

revision of training standards and accountabilities.

Since then, there has been a gradual shift in curricula

emphases, from the dominance of technocratic expertise to the

foregrounding of “nontechnical skills”.16,17 A range of generic

competencies have found their way into postgraduate medical

education and training, particularly in the areas of leadership,

research, and education. This recognition that doctors are an

integral part of a health care system, rather than isolated and

autonomous clinical professionals, is further underscored by

an increasing focus on quality improvement and population

health, and most recently a rediscovery of the patient at the

heart of care, with attention turning to issues such as coproduc-

tion, patient engagement, and supported self-management.18

With these changes has come the recognition that the

potential of the trainee body (junior doctors), a large sector

of the NHS workforce, is largely untapped. 19 Furthermore,

there is a risk that this future generation of influential health

care professionals may not be adequately engaged with the

“business” of health care provision, with the consequence

that our professional bureaucracy continues to normalize

around professional rather than system drivers.

Why engage junior doctors?

At the heart of postgraduate medical education is a managed

tension between service and training, with the learner also

as employee.20 Junior doctors rotate frequently between dif-

ferent service providers as part of their training in order to

achieve their competency-based curricula, but also represent

the front line of clinical service delivering, for example,

80% of ward-based activity.21 Due to their transient nature

within organizations, junior doctors are often disconnected

from their employers and viewed as a temporary work-

force providing service. However, this peripatetic group is

exposed to a myriad of different working practices within

a wide range of service providers and have the potential

to disseminate good practice as well the ability to identify

areas for change.22,23

With recognition that today’s junior doctors will be tomor-

row’s clinical leaders, the importance of the development of

management and leadership has been highlighted in many

policy documents, including an independent inquiry into

“Modernising Medical Careers”,

[…] the doctor’s frequent role as the head of the healthcare

team and commander of considerable resources requires

that greater attention is paid to managerial and leadership

skills irrespective of specialism (p 90).21

Many commentators have expressed concern that the

ability of doctors in training to influence change is not

being harnessed and are an underused resource, which if

mobilized could significantly improve quality and safety of

patient care.10,14,19,24 A recent survey of over 1,500 doctors in

training found that 91% had ideas for workplace improve-

ment, but only 11% had been able to implement these. 22,25

This is a waste. Leadership development of this group of

youthful energetic junior doctors should be an essential part

of “improving health, reducing its variation and doing so in

an affordable way” (p 466).26

What is clinical leadership?

As understood in Anglo–American contexts,27 the terms “lead-

ership” and “management” are sometimes used interchange-

ably,28 but within the health care literature they tend to describe

different approaches to how change can be achieved.

Management is sometimes viewed as a pejorative term,

particularly in the public sector, and the discourse of leader-

ship provides a more attractive narrative for professionals,

enabling policymakers to engage professionals into activi-

ties they desire, such as service reform. 29–31 While this may

be seen as a cynical tactic to co-opt professionals into the

organizational arena in order to control their activity,32 it

may also reflect a genuine recognition that to address the

“wicked” problems faced by health and social care organi-

zations, the particular knowledge and insight professionals

bring are crucial for effective negotiation, influence, and

persuasion with a variety of stakeholders in an increasingly

complex system.33

Definitions of leadership are many and contested, but

most commentators agree that leaders motivate, inspire, and

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

111

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

traditionally worked much longer hours, and these changes

reduced the degree to which the NHS could rely on doc-

tors in training for service delivery and, correspondingly,

decreased the amount of time doctors would have available

for training.

In order to address these issues, postgraduate training was

further reformed – under the banner of “Modernising Medical

Careers” – predominantly to accelerate the production of

competent specialists. “Modernising Medical Careers” led to

the creation of a 2-year foundation program, followed by basic

specialist training in a broad specialty grouping (eg, core med-

ical training), and then higher specialist training in a specific

specialty (eg, neurology).14 The aim was to provide doctors

with wide initial breadth of training, which would ultimately

be shorter by virtue of a more structured program later on.15

Explicit curricula for each specialty (there are 67 in the UK

with 35 subspecialties) were introduced alongside a wholesale

revision of training standards and accountabilities.

Since then, there has been a gradual shift in curricula

emphases, from the dominance of technocratic expertise to the

foregrounding of “nontechnical skills”.16,17 A range of generic

competencies have found their way into postgraduate medical

education and training, particularly in the areas of leadership,

research, and education. This recognition that doctors are an

integral part of a health care system, rather than isolated and

autonomous clinical professionals, is further underscored by

an increasing focus on quality improvement and population

health, and most recently a rediscovery of the patient at the

heart of care, with attention turning to issues such as coproduc-

tion, patient engagement, and supported self-management.18

With these changes has come the recognition that the

potential of the trainee body (junior doctors), a large sector

of the NHS workforce, is largely untapped. 19 Furthermore,

there is a risk that this future generation of influential health

care professionals may not be adequately engaged with the

“business” of health care provision, with the consequence

that our professional bureaucracy continues to normalize

around professional rather than system drivers.

Why engage junior doctors?

At the heart of postgraduate medical education is a managed

tension between service and training, with the learner also

as employee.20 Junior doctors rotate frequently between dif-

ferent service providers as part of their training in order to

achieve their competency-based curricula, but also represent

the front line of clinical service delivering, for example,

80% of ward-based activity.21 Due to their transient nature

within organizations, junior doctors are often disconnected

from their employers and viewed as a temporary work-

force providing service. However, this peripatetic group is

exposed to a myriad of different working practices within

a wide range of service providers and have the potential

to disseminate good practice as well the ability to identify

areas for change.22,23

With recognition that today’s junior doctors will be tomor-

row’s clinical leaders, the importance of the development of

management and leadership has been highlighted in many

policy documents, including an independent inquiry into

“Modernising Medical Careers”,

[…] the doctor’s frequent role as the head of the healthcare

team and commander of considerable resources requires

that greater attention is paid to managerial and leadership

skills irrespective of specialism (p 90).21

Many commentators have expressed concern that the

ability of doctors in training to influence change is not

being harnessed and are an underused resource, which if

mobilized could significantly improve quality and safety of

patient care.10,14,19,24 A recent survey of over 1,500 doctors in

training found that 91% had ideas for workplace improve-

ment, but only 11% had been able to implement these. 22,25

This is a waste. Leadership development of this group of

youthful energetic junior doctors should be an essential part

of “improving health, reducing its variation and doing so in

an affordable way” (p 466).26

What is clinical leadership?

As understood in Anglo–American contexts,27 the terms “lead-

ership” and “management” are sometimes used interchange-

ably,28 but within the health care literature they tend to describe

different approaches to how change can be achieved.

Management is sometimes viewed as a pejorative term,

particularly in the public sector, and the discourse of leader-

ship provides a more attractive narrative for professionals,

enabling policymakers to engage professionals into activi-

ties they desire, such as service reform. 29–31 While this may

be seen as a cynical tactic to co-opt professionals into the

organizational arena in order to control their activity,32 it

may also reflect a genuine recognition that to address the

“wicked” problems faced by health and social care organi-

zations, the particular knowledge and insight professionals

bring are crucial for effective negotiation, influence, and

persuasion with a variety of stakeholders in an increasingly

complex system.33

Definitions of leadership are many and contested, but

most commentators agree that leaders motivate, inspire, and

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

112

Aggarwal and Swanwick

align strategy to establish direction for individuals and the

systems in which they work, while managers are process

driven and use problem solving to direct individuals and

resources to achieve goals already established by leader-

ship.1,34,35 As described in an influential report from the

King’s Fund, leadership, management, and administration

are interdependent since … without leadership there can be

no effective management – because the organization will not

know what it is meant to be doing – and without good admin-

istration management can be rendered ineffective (p 1).36

If we accept Mintzberg’s theory that health care organi-

zations exhibit an inverted power structure, a new leadership

paradigm emerges. Those providing front-line service have

significant influence over the operational activities, result-

ing in a range of patient- and population-related outcomes

compared to those who occupy hierarchical positions of

authority. Hence, clinical leadership becomes an inclusive

endeavor. By engaging champions of health care quality

at service-level, behaviors and attitudes on the front line

can be aligned with organizational vision, ensuring that the

needs of the patient are central in the organization’s aims

and delivery. This view of clinical leadership appeals to

clinicians as it frames health care management around the

leadership of change and improvement for the safety and

quality of patient care. It is a discourse that also replaces the

previous one of professionals as the cause of problems in

public service organizations and, crucially, begins to view

them as part of the solution.

Leadership models, trends,

and contexts

Swanwick and McKimm35 frame leadership as a social

construct, influenced by the preoccupations, sociopoliti-

cal system, and cultural values of the time. The leadership

theories and models espoused will influence the discourses

adopted and reflect societal views of how systems are or

should be organized. This is clearly crucial when we consider

leadership development, as how leadership is conceptualized

will profoundly influence approaches taken in the name of

its development. In the following sections, we summarize

some of the previous century’s most influential leadership

models and consider what might be needed for a 21st century

health service.

Trait theory

In the first half of the 20th Century, “trait” theories emerged

around the ideal of the “Great Man” proposing that great

leaders (usually men, reflecting the position women had in

society at that time) had a defined collection of personal

attributes, including ability, sociability, motivation, and

dominance. This theory is attractive to doctors given the

weight placed on key personal characteristics in their selec-

tion process, but as Willcocks37 maintains, while many doc-

tors may possess leadership qualities, these are not equally

distributed and some doctors may be able to employ these

in a clinical encounter, but not necessarily in the dynamic

group context of leadership. Literature reviews in the 1970s

failed to consistently identify the personality traits that

distinguish leaders from nonleaders, although one more

recent review has identified a weak positive correlation

between successful leaders and three of the “big five” per-

sonality factors – extroversion, openness to new experience,

and conscientiousness. 38 Additionally, leaders had a weak

negative correlation with neuroticism, but interestingly, no

relationship was found to the extent to which the leader is

agreeable. Another review in the context of school leader-

ship found less emphasis or correlation on these “innate

qualities” with successful leadership. 39

Leadership styles

From the 1950, greater emphasis began to be placed

on leadership styles and behaviors rather than personal

characteristics. In part, this was a reaction to the deficiencies

of the trait approach and its failure to recognize the context

in which leadership occurred. The shift in theory focused

on two aspects – how leaders made decisions and on what

they were focused. Many taxonomies for decision-making

styles developed, but the most famous is perhaps that of

Tannenbaum and Schmidt 40 who describe a continuum of

leadership behavior from autocratic (“do as I say”) to abdi-

catory (“do what you like”). Other styles embraced team

management, where leadership is focused on results or the

people in the organization,41,42 or an authoritative manner

which mobilizes empathetically toward a vision.43 These

styles are attractive for clinicians in leadership roles as they

embrace balancing the needs of patients and team members

within an environment where resources are constrained and

management targets need to be met.

Contingency theories

In order to recognize the complexity and context of different

situations, contingency theories became popular in the 1960s,

the concept being that leaders should adapt their style to the

competence and commitment of followers, using a range of

interventions, such as directing, coaching, supporting, and

delegating. Such an approach requires not only awareness of

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

112

Aggarwal and Swanwick

align strategy to establish direction for individuals and the

systems in which they work, while managers are process

driven and use problem solving to direct individuals and

resources to achieve goals already established by leader-

ship.1,34,35 As described in an influential report from the

King’s Fund, leadership, management, and administration

are interdependent since … without leadership there can be

no effective management – because the organization will not

know what it is meant to be doing – and without good admin-

istration management can be rendered ineffective (p 1).36

If we accept Mintzberg’s theory that health care organi-

zations exhibit an inverted power structure, a new leadership

paradigm emerges. Those providing front-line service have

significant influence over the operational activities, result-

ing in a range of patient- and population-related outcomes

compared to those who occupy hierarchical positions of

authority. Hence, clinical leadership becomes an inclusive

endeavor. By engaging champions of health care quality

at service-level, behaviors and attitudes on the front line

can be aligned with organizational vision, ensuring that the

needs of the patient are central in the organization’s aims

and delivery. This view of clinical leadership appeals to

clinicians as it frames health care management around the

leadership of change and improvement for the safety and

quality of patient care. It is a discourse that also replaces the

previous one of professionals as the cause of problems in

public service organizations and, crucially, begins to view

them as part of the solution.

Leadership models, trends,

and contexts

Swanwick and McKimm35 frame leadership as a social

construct, influenced by the preoccupations, sociopoliti-

cal system, and cultural values of the time. The leadership

theories and models espoused will influence the discourses

adopted and reflect societal views of how systems are or

should be organized. This is clearly crucial when we consider

leadership development, as how leadership is conceptualized

will profoundly influence approaches taken in the name of

its development. In the following sections, we summarize

some of the previous century’s most influential leadership

models and consider what might be needed for a 21st century

health service.

Trait theory

In the first half of the 20th Century, “trait” theories emerged

around the ideal of the “Great Man” proposing that great

leaders (usually men, reflecting the position women had in

society at that time) had a defined collection of personal

attributes, including ability, sociability, motivation, and

dominance. This theory is attractive to doctors given the

weight placed on key personal characteristics in their selec-

tion process, but as Willcocks37 maintains, while many doc-

tors may possess leadership qualities, these are not equally

distributed and some doctors may be able to employ these

in a clinical encounter, but not necessarily in the dynamic

group context of leadership. Literature reviews in the 1970s

failed to consistently identify the personality traits that

distinguish leaders from nonleaders, although one more

recent review has identified a weak positive correlation

between successful leaders and three of the “big five” per-

sonality factors – extroversion, openness to new experience,

and conscientiousness. 38 Additionally, leaders had a weak

negative correlation with neuroticism, but interestingly, no

relationship was found to the extent to which the leader is

agreeable. Another review in the context of school leader-

ship found less emphasis or correlation on these “innate

qualities” with successful leadership. 39

Leadership styles

From the 1950, greater emphasis began to be placed

on leadership styles and behaviors rather than personal

characteristics. In part, this was a reaction to the deficiencies

of the trait approach and its failure to recognize the context

in which leadership occurred. The shift in theory focused

on two aspects – how leaders made decisions and on what

they were focused. Many taxonomies for decision-making

styles developed, but the most famous is perhaps that of

Tannenbaum and Schmidt 40 who describe a continuum of

leadership behavior from autocratic (“do as I say”) to abdi-

catory (“do what you like”). Other styles embraced team

management, where leadership is focused on results or the

people in the organization,41,42 or an authoritative manner

which mobilizes empathetically toward a vision.43 These

styles are attractive for clinicians in leadership roles as they

embrace balancing the needs of patients and team members

within an environment where resources are constrained and

management targets need to be met.

Contingency theories

In order to recognize the complexity and context of different

situations, contingency theories became popular in the 1960s,

the concept being that leaders should adapt their style to the

competence and commitment of followers, using a range of

interventions, such as directing, coaching, supporting, and

delegating. Such an approach requires not only awareness of

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

113

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

these styles of leadership, but also the recognition of when a

particular approach is required with appropriate enactment.

A criticism of contingency theories is that they are highly

dependent upon who defines the situation in question.44

Transformational leadership

In the 1980s, a new paradigm of transformational leadership

emerged, arising in part from the recognition that previous

leadership approaches failed to account for the fact that envi-

ronments are subject to continual change.45 Existing models

tended to be transactional and managerial in nature, which

were useful to plan and organize at times of stability, but inad-

equate when describing how to lead people or organizations

through periods of significant change. In the transformational

model, leaders release human potential through empower-

ment and development of followers. Leaders articulate the

values and direction of an organization, work of individuals

within the organization is aligned to the achievement of these

long-term goals, and followers are nurtured thereby strength-

ening organizational culture and engendering a commitment

to move toward a shared envisioned future.

One of the problems with a transformational leadership

approach is the tendency toward the veneration of indi-

vidual leaders as “tsars”. This led in the 1990s to a wave

of charismatic individuals sweeping into “turnaround”

failing organizations using their dominant personality and

self-confidence to influence others, while exhibiting strong

role modeling, extolling high expectations, and articulat-

ing ideological goals. As a complete antithesis, servant

leadership offers a quieter stewardship approach where

leaders facilitate growth and development, and serve the

needs of the community by persuasion rather than coercion

with empathetic listening and encouragement to collective

action.46 Nevertheless, “heroic” transformational leadership

has proven to be an enduring model, being incorporated into

many public sector frameworks including the UK’s NHS

Healthcare Leadership Model. 47

Distributed leadership

This “post heroic” model considers leadership not to

reside in one individual but instead the focus is on “…

organisational relations, connectedness, interventions into

the organization system, changing organization practices

and processes” (p 6). 48 Boundaries to leadership are open,

encompassing multiple individuals whose expertise is dis-

tributed across professional and organizational boundaries,

building upon social capital for innovation, collaboration, and

improved outcomes.49,50 Leadership shifts from the focus on

individual qualities of a leader at the top of an organization

to the process of leadership within an organization. It offers

the exciting opportunity where leadership development is not

about creating more leaders, but systems where leadership

is everyone’s responsibility and enabled by a diverse range

of groups and individuals. 23 Distributed leadership moves

beyond the lonely model of heroic leadership to a shared,

adaptive, and collaborative approach that forces leaders to

focus on systems of care and not just organizational delivery

of results through followership.

So what is it then about the clinical context that influ-

ences the way we might think about “clinical leadership”,

and medical leadership specifically. As we have discussed,

health systems are complex. They have range of aims

and objectives (not simple profit/loss) controlled through

professional networks often with an absence of direct line

management or contractual control, with colleagues who

may have completely different sets of accountabilities and

who often are situated in completely different organizations.

Health and social care systems in the UK are also incredibly

diverse in terms of the culture, ethnicity, sex, and educational

background of its workforce.

Evidence from a study of 13 organizations shows that

a team structure working on a basis of trust will create

“a mutually reinforcing circle of benefits” (p 370). 51 This

supports the view that a top-down approach of leadership is

doomed to fail in a complex and uncertain environment. The

distributed leadership model enables local decision-making

by individuals, who guided by organizational vision, values,

and strategic intent do not then need excessive hierarchical

structures. This approach shifts away from a focus on indi-

vidual leadership characteristics or styles to a process of

“engagement”, where the mobilization, commitment, and

alignment of front line staff create a culture of leadership

within an organization.36,50

But is this enough? Health care is increasingly deliv-

ered by organizations working together, across the tradi-

tional boundaries of health and social care toward a set of

shared objectives. This requires leadership that not only is

distributed vertically within individual organizations, but

horizontally across whole health care systems, where the

leadership, at any one moment, might be taken by anyone,

from anywhere. This requires an even more sophisticated

approach and in a series of review publications by the

Kings Fund, a consensus is building that such a chal-

lenging environment requires leadership that is not only

distributed, but also collective, collaborative, and, above

all, compassionate. 52

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

113

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

these styles of leadership, but also the recognition of when a

particular approach is required with appropriate enactment.

A criticism of contingency theories is that they are highly

dependent upon who defines the situation in question.44

Transformational leadership

In the 1980s, a new paradigm of transformational leadership

emerged, arising in part from the recognition that previous

leadership approaches failed to account for the fact that envi-

ronments are subject to continual change.45 Existing models

tended to be transactional and managerial in nature, which

were useful to plan and organize at times of stability, but inad-

equate when describing how to lead people or organizations

through periods of significant change. In the transformational

model, leaders release human potential through empower-

ment and development of followers. Leaders articulate the

values and direction of an organization, work of individuals

within the organization is aligned to the achievement of these

long-term goals, and followers are nurtured thereby strength-

ening organizational culture and engendering a commitment

to move toward a shared envisioned future.

One of the problems with a transformational leadership

approach is the tendency toward the veneration of indi-

vidual leaders as “tsars”. This led in the 1990s to a wave

of charismatic individuals sweeping into “turnaround”

failing organizations using their dominant personality and

self-confidence to influence others, while exhibiting strong

role modeling, extolling high expectations, and articulat-

ing ideological goals. As a complete antithesis, servant

leadership offers a quieter stewardship approach where

leaders facilitate growth and development, and serve the

needs of the community by persuasion rather than coercion

with empathetic listening and encouragement to collective

action.46 Nevertheless, “heroic” transformational leadership

has proven to be an enduring model, being incorporated into

many public sector frameworks including the UK’s NHS

Healthcare Leadership Model. 47

Distributed leadership

This “post heroic” model considers leadership not to

reside in one individual but instead the focus is on “…

organisational relations, connectedness, interventions into

the organization system, changing organization practices

and processes” (p 6). 48 Boundaries to leadership are open,

encompassing multiple individuals whose expertise is dis-

tributed across professional and organizational boundaries,

building upon social capital for innovation, collaboration, and

improved outcomes.49,50 Leadership shifts from the focus on

individual qualities of a leader at the top of an organization

to the process of leadership within an organization. It offers

the exciting opportunity where leadership development is not

about creating more leaders, but systems where leadership

is everyone’s responsibility and enabled by a diverse range

of groups and individuals. 23 Distributed leadership moves

beyond the lonely model of heroic leadership to a shared,

adaptive, and collaborative approach that forces leaders to

focus on systems of care and not just organizational delivery

of results through followership.

So what is it then about the clinical context that influ-

ences the way we might think about “clinical leadership”,

and medical leadership specifically. As we have discussed,

health systems are complex. They have range of aims

and objectives (not simple profit/loss) controlled through

professional networks often with an absence of direct line

management or contractual control, with colleagues who

may have completely different sets of accountabilities and

who often are situated in completely different organizations.

Health and social care systems in the UK are also incredibly

diverse in terms of the culture, ethnicity, sex, and educational

background of its workforce.

Evidence from a study of 13 organizations shows that

a team structure working on a basis of trust will create

“a mutually reinforcing circle of benefits” (p 370). 51 This

supports the view that a top-down approach of leadership is

doomed to fail in a complex and uncertain environment. The

distributed leadership model enables local decision-making

by individuals, who guided by organizational vision, values,

and strategic intent do not then need excessive hierarchical

structures. This approach shifts away from a focus on indi-

vidual leadership characteristics or styles to a process of

“engagement”, where the mobilization, commitment, and

alignment of front line staff create a culture of leadership

within an organization.36,50

But is this enough? Health care is increasingly deliv-

ered by organizations working together, across the tradi-

tional boundaries of health and social care toward a set of

shared objectives. This requires leadership that not only is

distributed vertically within individual organizations, but

horizontally across whole health care systems, where the

leadership, at any one moment, might be taken by anyone,

from anywhere. This requires an even more sophisticated

approach and in a series of review publications by the

Kings Fund, a consensus is building that such a chal-

lenging environment requires leadership that is not only

distributed, but also collective, collaborative, and, above

all, compassionate. 52

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

114

Aggarwal and Swanwick

Does clinical leadership make a

difference?

Effective leadership is an important component of success-

ful health care organizations,53,54 whereas lack of leadership

can be associated with organizational failure.4,55 Veronesi

et al56 suggest clinical leaders influence health care system

outcomes since they have the expert knowledge of the core

business of health services and a deeper awareness of what

patient care involves … [to] make better informed decisions

regarding service design and resource allocation.

Forbes et al57 describe “role design” for clinician manag-

ers, who, instead of replicating the role of hospital managers,

use their unique voice to focus on clinical priorities.

There is a growing literature on the benefit of clinicians

in management and evidence that high-performing medical

groups build relationships with managers, with an emphasis

on clinical quality.58,59 Clinicians in senior management roles

tend to enhance operational outcomes for hospitals and orga-

nizations perform significantly better than those with lower

levels of clinician participation.60–63 A review conducted by

the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges in the UK concluded

that chief executive officers from high-performing institutions

engaged clinicians in dialogue and joint problem solving.64

Goodall65 demonstrates that hospital quality scores are 25%

higher in physician-headed hospitals compared to those with

chief executive officers from nonmedical backgrounds. More

recently, research undertaken by Veronesi et al56 in the UK

tentatively suggested that the “share of doctors” on the board

made most difference, and this relationship became less robust

when other health professionals were involved at board level.

This chimes with Dorgan et al 6 who investigated organiza-

tions across seven countries and suggested that having higher

proportions of medically qualified managers results in more

effective management practices.

It can be difficult to quantify the exact impact of clini-

cal leadership on service quality; however, studies do exist

which suggest improvements in various domains. A study

of hospitals in Michigan found that by using bed occupancy

rates and market share as performance measures and by

excluding clinical leaders from strategic decisions resulted

in lower hospital performance.66 Keroack et al67 ranked

health care institutions using a composite index of qual-

ity and safety that was developed to incorporate domains

identified as attributes of an ideal health care system. High

performance scores for organizations were associated with

organizational leadership that prioritized patients, focused

on quality and safety, used clear systems of accountability,

sought continual improvement as evidenced by results, and

emphasized collaboration between different staff groups

to make use of their varied expertise. Commissioned by

the King’s Fund to inform the leadership commission,

Baker68 used case studies to identify factors accounting

for success in high-performing systems; again, clinical

leadership that prioritized patients, quality and safety,

and that promoted collaborative working between differ-

ent professional groups was consistently present in all of

these institutions.

Barriers to clinical leadership

development

It becomes increasingly clear that clinical leadership is a cen-

tral ingredient to improve the quality of health care.36,69 It is

an essential component to align process redesign for business

operations and quality assurance, with clinical agendas per-

taining to patient care, service development, and professional

development for high quality services. Yet, despite the wealth

of evidence concerning the importance of clinical leadership

in health care organizations, it remains a variable constituent

of health systems. Darzi70 concluded in the NHS Next Stage

Review that “leadership has been the neglected element of the

[health service] reforms of recent years” (p 66). A report by

the King’s Fund again highlighted the failure of the NHS to

engage doctors in management and leadership and that “man-

agement and leadership needs to be shared between managers

and clinicians and equally valued by both” (p xi).36

The evidence for this lack of engagement highlights three

factors that prevent clinical leadership from being embraced:

reluctance of doctors to enter into management, weak incen-

tives for leadership activities, and the lack of provision of

training or nurturing mechanisms for young clinicians wish-

ing to engage with this aspect of health care provision.

Ham8 recognizes that change is incremental, slow, and

painstaking work, which can be at odds with policymakers

and taxpayers who want to see quick results. There is a mis-

match between those introducing the bottom-up incremental

changes for effective and enduring service improvement

compared to the expectations of policymakers who want “big

bang reforms” (p 2).8 Clinicians are used to the immediacy

of delivering patient care and are reticent to shift their focus

to leadership, where rewards are longer term and often not

easily defined.71 Among doctors, the emphasis through-

out training is on “individual action and accountability”

(p 483), and they often cannot conceive how leadership can

be relevant to patient care.72 Doctors also face consider-

able pressure to meet clinical targets, and a recent British

Medical Association review found a consistent barrier for

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

114

Aggarwal and Swanwick

Does clinical leadership make a

difference?

Effective leadership is an important component of success-

ful health care organizations,53,54 whereas lack of leadership

can be associated with organizational failure.4,55 Veronesi

et al56 suggest clinical leaders influence health care system

outcomes since they have the expert knowledge of the core

business of health services and a deeper awareness of what

patient care involves … [to] make better informed decisions

regarding service design and resource allocation.

Forbes et al57 describe “role design” for clinician manag-

ers, who, instead of replicating the role of hospital managers,

use their unique voice to focus on clinical priorities.

There is a growing literature on the benefit of clinicians

in management and evidence that high-performing medical

groups build relationships with managers, with an emphasis

on clinical quality.58,59 Clinicians in senior management roles

tend to enhance operational outcomes for hospitals and orga-

nizations perform significantly better than those with lower

levels of clinician participation.60–63 A review conducted by

the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges in the UK concluded

that chief executive officers from high-performing institutions

engaged clinicians in dialogue and joint problem solving.64

Goodall65 demonstrates that hospital quality scores are 25%

higher in physician-headed hospitals compared to those with

chief executive officers from nonmedical backgrounds. More

recently, research undertaken by Veronesi et al56 in the UK

tentatively suggested that the “share of doctors” on the board

made most difference, and this relationship became less robust

when other health professionals were involved at board level.

This chimes with Dorgan et al 6 who investigated organiza-

tions across seven countries and suggested that having higher

proportions of medically qualified managers results in more

effective management practices.

It can be difficult to quantify the exact impact of clini-

cal leadership on service quality; however, studies do exist

which suggest improvements in various domains. A study

of hospitals in Michigan found that by using bed occupancy

rates and market share as performance measures and by

excluding clinical leaders from strategic decisions resulted

in lower hospital performance.66 Keroack et al67 ranked

health care institutions using a composite index of qual-

ity and safety that was developed to incorporate domains

identified as attributes of an ideal health care system. High

performance scores for organizations were associated with

organizational leadership that prioritized patients, focused

on quality and safety, used clear systems of accountability,

sought continual improvement as evidenced by results, and

emphasized collaboration between different staff groups

to make use of their varied expertise. Commissioned by

the King’s Fund to inform the leadership commission,

Baker68 used case studies to identify factors accounting

for success in high-performing systems; again, clinical

leadership that prioritized patients, quality and safety,

and that promoted collaborative working between differ-

ent professional groups was consistently present in all of

these institutions.

Barriers to clinical leadership

development

It becomes increasingly clear that clinical leadership is a cen-

tral ingredient to improve the quality of health care.36,69 It is

an essential component to align process redesign for business

operations and quality assurance, with clinical agendas per-

taining to patient care, service development, and professional

development for high quality services. Yet, despite the wealth

of evidence concerning the importance of clinical leadership

in health care organizations, it remains a variable constituent

of health systems. Darzi70 concluded in the NHS Next Stage

Review that “leadership has been the neglected element of the

[health service] reforms of recent years” (p 66). A report by

the King’s Fund again highlighted the failure of the NHS to

engage doctors in management and leadership and that “man-

agement and leadership needs to be shared between managers

and clinicians and equally valued by both” (p xi).36

The evidence for this lack of engagement highlights three

factors that prevent clinical leadership from being embraced:

reluctance of doctors to enter into management, weak incen-

tives for leadership activities, and the lack of provision of

training or nurturing mechanisms for young clinicians wish-

ing to engage with this aspect of health care provision.

Ham8 recognizes that change is incremental, slow, and

painstaking work, which can be at odds with policymakers

and taxpayers who want to see quick results. There is a mis-

match between those introducing the bottom-up incremental

changes for effective and enduring service improvement

compared to the expectations of policymakers who want “big

bang reforms” (p 2).8 Clinicians are used to the immediacy

of delivering patient care and are reticent to shift their focus

to leadership, where rewards are longer term and often not

easily defined.71 Among doctors, the emphasis through-

out training is on “individual action and accountability”

(p 483), and they often cannot conceive how leadership can

be relevant to patient care.72 Doctors also face consider-

able pressure to meet clinical targets, and a recent British

Medical Association review found a consistent barrier for

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2015:7 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

115

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

engagement in leadership to be a lack of time and resources

to meet clinical priorities.73 So, time away from patient care

to concentrate on management and leadership is perceived

as a distraction unless doctors have robust evidence for the

value of such activities.

Despite the recent foregrounding of clinicians in manage-

ment and the emergence of a new definition of the medical

professional, tribalism and an ingrained distrust of doctors

entering the management sphere persists. Clinicians function

in an era of evidence-based practice and can have entrenched

views about the credibility and value of leadership. Degeling

et al74 accept that clinical leaders are well placed to take

forward NHS reforms, but find reluctance among medical

managers to question the perceived dominance of medicine in

clinical settings, thus making collective working difficult. On

the other side, a culture of “antimanagerialism” exists where

clinical leader colleagues are described as having gone “over

to the dark side”.71,75,76

Mintzberg77 (p 199) believes that clinicians and clinical

leaders fail to understand the role of professional manag-

ers, perceiving them as servants in the system as opposed

to powerful allies, seated at “the locus of uncertainty” and

able to influence the power afforded to clinicians within the

organization. Edmonstone78 is brutal in chastising clinicians

for working in uniprofessional silos, which he claims prevents

effective and safe delivery of health care. He offers an alter-

native where effective organizations have models of service

delivery based upon supportive team structures, learning

from mistakes, and instigation of service change.

Alongside these issues, incentives for entering into such

activities are weak. There is no predefined career structure

for service leadership, with promotion and remuneration

linked to clinical activities as opposed to participation in

management. Measurement of quality of care is imperfect

and rudimentary; therefore, it is not possible to reward those

who build the best services unlike those who receive financial

accolades for clinical or research activity. Moreover, tradi-

tional role models for clinicians are individuals who excel in

the practice of their profession and not organizational leaders.

Leadership is not viewed as equivalent to research, where

participation in the latter results in career advancement,

prestige, influence, promotion, and financial reward.2

For learners in the health care professions, there has been

little provision for clinical leadership development in the

past, with training and education in this area being largely

absent from core curricula. However, this is changing. The

undergraduate curricula developed by the Nursing and

Midwifery Council (2010) and the General Medical Council

(2009) have started to reflect the need for clinical leadership

development in the preregistration workforce, and all post-

graduate curricula now contain intended learning outcomes

in the area of leadership and management. But embedding a

leadership competency framework into professional curricula

is merely a start.79

The bulk of the professional workforce are already active

in the NHS and often represent the front line of service,

whom Swanwick19 states “have the capability, energy, and

enthusiasm to transform the NHS” (p 117). In Denmark, an

explicit aim to increase the number of doctors stepping into

leadership roles has shifted the culture to not only impact

medical behavior and curricula, but also form the basis of

appointment criteria.80 Danish postgraduate doctors receive

mandatory leadership training based upon the CanMEDS

roles framework,81 and after consultant appointment, they

are expected to participate in leadership development

programs.10 A similar robust program of systematic leader-

ship development utilizing CanMEDS is also evident in the

Netherlands.10

In their extensive review of theoretical and empirical

literature of leadership and leadership development, Day

et al82 conclude that while leadership is something that all

organizations value, they are much less interested in which

theory or model is the “right” approach, instead they want to

know how to develop leaders and leadership as effectively and

efficiently as possible. In the next section of this paper, we

provide a review of some of the leadership interventions for

junior doctors that have been utilized in the UK and attempt

to identify the hallmarks of effective leadership development

in this context.

Leadership development of junior

doctors in the UK

Against this backdrop of evidence for the impact of clinical

leadership and the significant issues surrounding its prac-

tice, a raft of interventions has been deployed in an effort to

engage young clinicians in leadership activities. Leadership

development interventions in common use range from one-

day workshops, short courses, experiential programs to

postgraduate masters and doctoral awards. A number of these

approaches are now explored in more depth.

Competency frameworks

In early 2000, the NHS in England commissioned Hay Group

management consultancy to identify a core set of leader-

ship qualities associated with success at chief executive and

executive director levels, which lead to the production of

Journal of Healthcare Leadership downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 193.93.195.147 on 25-Aug-2018

For personal use only.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress

Dovepress

115

Leadership development in postgraduate medical education and trainin

engagement in leadership to be a lack of time and resources

to meet clinical priorities.73 So, time away from patient care

to concentrate on management and leadership is perceived