Integrative Review: Mental Health Service Users' Experiences of Care

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/07

|12

|10914

|81

Report

AI Summary

This integrative literature review, published in the Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, examines the experiences of mental health service users. The review, conducted by researchers at the University of Limerick, analyzed 34 studies published between 2008 and 2012, focusing on adults aged 18-65. The research explored service users' perspectives on accessing care, building relationships with providers, and the continuity of care within mental health services. Key themes emerged, including the importance of acknowledging mental health problems, fostering relationships, and ensuring continuity of care. The review highlights issues with stigma, poor communication, and the need for a shift in the provider-service user relationship to facilitate genuine engagement and empowerment, particularly in relation to the recovery model. The review emphasizes the critical role of relationships in mental health care and suggests implications for mental health nursing practices.

Mental health service users’ experiences of mental

health care: an integrative literature review

D . N E W M A N 1 M S c B Sc ( H o n s ) R P N,

P . O ’ R E I L LY 2 P h D M A ( Ed ) B Sc ( H o n s ) R G N R N I D ,

S . H . L E E3 P h D M P H E B Sc ( H o n s ) C e r t . E d . R N R M &

C . K E N N E D Y4 P h D B A ( H o n s ) D N R N T R N

1PhD Student,2Head of Department,3Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, and4Professor of Nursing and Midwifery,

Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Keywords:communication, experience,

mental health, mental health service user

and relationships, service providers

Correspondence:

D. Newman

Department Nursing and Midwifery

University of Limerick

Health Science Building

Northbank Campus

Limerick

Ireland

E-mail: daniel.newman@ul.ie

Accepted for publication: 7 January

2015

doi: 10.1111/jpm.12202

Accessible summary

• A number of studies have highlighted issues around the relationship between

service users and providers. The recovery model is predominant in mental heal

as is the recognition of the importance of person-centred practice.The authors

completed an in-depth search of the literature to answer the question: What are

service users’ experiences of the mental health service?

• Three key themes emerged: acknowledging a mental health problem and seeki

help;building relationships through participation in care;and working towards

continuity of care.

• The review adds to the current body of knowledge by providing greater detail in

the importance of relationships between service users and providers and how th

may impact on the delivery of care in the mental health service. The overarchin

theme that emerged was the importance of the relationship between the servic

user and provider as a basis for interaction and support.

• This review has specific implications for mental health nursing. Despite the reco

nition made in policy documents for change, issues with stigma, poor attitudes

communication persist. There is a need for a fundamental shift in the provider–

service user relationship to facilitate true service-user engagement in their care

Abstract

The aim of this integrative literature review was to identify mentalhealth service

users’ experiences of services. The rationale for this review was based on the grow

emphasis and requirements for health services to deliver care and support,which

recognizes the preferences of individuals. Contemporary models of mental health c

strive to promote inclusion and empowerment.This review seeks to add to our

current understanding of how service users experience care and support in order t

determine to what extent the principles of contemporary models of mental health

are embedded in practice. A robust search of Web of Science, the Cochrane Datab

Science Direct, EBSCO host (Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus

Full-Text),PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Social SciencesFull Text and the United

Kingdom and Ireland Reference Centre for data published between 1 January 2008

and 31 December 2012 was completed. The initial search retrieved 272 609 paper

The authors used a staged approach and the application of predetermined inclusio

exclusion criteria, thus the numbers of papers for inclusion were reduced to 34. Da

extraction, quality assessment and thematic analysis were completed for the inclu

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2015, 22, 171–182

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 171

health care: an integrative literature review

D . N E W M A N 1 M S c B Sc ( H o n s ) R P N,

P . O ’ R E I L LY 2 P h D M A ( Ed ) B Sc ( H o n s ) R G N R N I D ,

S . H . L E E3 P h D M P H E B Sc ( H o n s ) C e r t . E d . R N R M &

C . K E N N E D Y4 P h D B A ( H o n s ) D N R N T R N

1PhD Student,2Head of Department,3Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, and4Professor of Nursing and Midwifery,

Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Keywords:communication, experience,

mental health, mental health service user

and relationships, service providers

Correspondence:

D. Newman

Department Nursing and Midwifery

University of Limerick

Health Science Building

Northbank Campus

Limerick

Ireland

E-mail: daniel.newman@ul.ie

Accepted for publication: 7 January

2015

doi: 10.1111/jpm.12202

Accessible summary

• A number of studies have highlighted issues around the relationship between

service users and providers. The recovery model is predominant in mental heal

as is the recognition of the importance of person-centred practice.The authors

completed an in-depth search of the literature to answer the question: What are

service users’ experiences of the mental health service?

• Three key themes emerged: acknowledging a mental health problem and seeki

help;building relationships through participation in care;and working towards

continuity of care.

• The review adds to the current body of knowledge by providing greater detail in

the importance of relationships between service users and providers and how th

may impact on the delivery of care in the mental health service. The overarchin

theme that emerged was the importance of the relationship between the servic

user and provider as a basis for interaction and support.

• This review has specific implications for mental health nursing. Despite the reco

nition made in policy documents for change, issues with stigma, poor attitudes

communication persist. There is a need for a fundamental shift in the provider–

service user relationship to facilitate true service-user engagement in their care

Abstract

The aim of this integrative literature review was to identify mentalhealth service

users’ experiences of services. The rationale for this review was based on the grow

emphasis and requirements for health services to deliver care and support,which

recognizes the preferences of individuals. Contemporary models of mental health c

strive to promote inclusion and empowerment.This review seeks to add to our

current understanding of how service users experience care and support in order t

determine to what extent the principles of contemporary models of mental health

are embedded in practice. A robust search of Web of Science, the Cochrane Datab

Science Direct, EBSCO host (Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus

Full-Text),PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Social SciencesFull Text and the United

Kingdom and Ireland Reference Centre for data published between 1 January 2008

and 31 December 2012 was completed. The initial search retrieved 272 609 paper

The authors used a staged approach and the application of predetermined inclusio

exclusion criteria, thus the numbers of papers for inclusion were reduced to 34. Da

extraction, quality assessment and thematic analysis were completed for the inclu

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2015, 22, 171–182

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 171

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

studies. Satisfaction with the mental health service was moderately good. However

accessing services could be difficult because of a lack of knowledge and the stigma

surrounding mentalhealth.Large surveys document moderate satisfaction ratings;

however,feelings of fear regarding how services function and the lack of treatment

choice remain.The main finding from thisreview is while people may express

satisfaction with mentalhealth services,there are stillissuesaround three main

themes: acknowledging a mental health problem and seeking help; building relation

ship through participation and care;and working towards continuity of care.

Elements of the recovery model appear to be lacking in relation to user involvemen

empowerment and decision making.There is a need for a fundamentalshift in the

contextof the provider–service userrelationship to fully facilitate service users’

engagement in their care.

Introduction

A predominant focus in mental health policy and practice

over the last 20 years has been greater efforts to involve

people in their care planning.Historically,service users’

involvementin their mentalhealth serviceswas limited

(Campbell 2005, Dunne 2006). Understanding the views of

the service user remains essential in contemporary mental

health in order to identify the extent to which a service is

achieving its aims and purpose. The aim of this integrative

review wasto establish whatevidence existsas to the

experiences service users have of mental health services.

Legislationsprotecting service users’rights has been

introduced and implemented in the United Kingdom and

Ireland (Mental Health Act 2007, House of Parliament and

Mental Health Act 2001 Houses of the Oireachtas).

Furthermore, new models or approaches to care have been

advocated including the recovery modelwhich has been

promoted internationally [e.g. MHC (NZ) 1998;

Departmentof Health 2001;MHC (Ireland) 2008].The

main elements of the recovery modelare greater service-

user involvement,modernizing the mentalhealth work-

force, viewing the person beyond the illness,increased

personalization,facilitating choice of treatmentsand

changesto education programmes.The recovery model

seeks to invertthe role ofthe service user from being a

follower to one where they are able to lead,change and

direct their own care (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health

2008). The prominence and importance of patient-centred

care,also identified by Epstein & Street (2011),aimed to

ensure service users’ needs and preferences are respected. A

key aim of patient-centred care is to help service users make

and contribute to, informed decisions about their care.

Research in the early 2000sidentified severalissues

around the relationship between service users and provid-

ers. For example,Dunne (2006)highlighted thatservice

userscontinued to experience poorcommunication and

lack of continuity of care.A preliminary literature search

did not identify a recent review that addressed experiences

acrossmentalhealth services.Therefore,as the debate

regarding theautonomy and rightsof serviceusersin

mentalhealth continues,it is timely to identify whatis

known aboutmentalhealth service users’experiences of

mental health services.

Aim and methods of the review

The aim of this integrative literature review was to identify

how service users experiencemental health services.

Mental health service users are not a homogeneous group

with similar experiences,so the focus ofthis integrative

review was the experiences of adults (18–65 years old) who

accessed and used a mental health service. Reports relating

to specialist services such as homeless services, the utiliza-

tion of mental health laws, detention or involuntary admis-

sion, clinical treatments or reports that outline changes in

work practices in specific areas were excluded as outlined

fully in Table 1. The focus of this review was on database

searchesin order to extract evidencefrom systematic

reviews and primary empirical qualitative and quantitative

studies (Table 1).

An integrative review was undertaken to address the aim

of the review. This approach is increasingly recognized as

appropriate to inform evidence-based practice.The inte-

grative review synthesize findings from a diverse range of

primary experimentaland non-experimentalresearch

methods in order to provide a breadth of perspectives and

a more comprehensive understanding of a healthcare issue

(Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Given the aim was to evaluate

services users’ experiences, an integrative review was con-

sidered to be the appropriatemethod.The approach

reported here reflects key aspects of the systematic review

methodsadvocated by the Cochrane Collaboration and

the Scottish IntercollegiateGuideline Network (SIGN

D Newman et al.

172 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

accessing services could be difficult because of a lack of knowledge and the stigma

surrounding mentalhealth.Large surveys document moderate satisfaction ratings;

however,feelings of fear regarding how services function and the lack of treatment

choice remain.The main finding from thisreview is while people may express

satisfaction with mentalhealth services,there are stillissuesaround three main

themes: acknowledging a mental health problem and seeking help; building relation

ship through participation and care;and working towards continuity of care.

Elements of the recovery model appear to be lacking in relation to user involvemen

empowerment and decision making.There is a need for a fundamentalshift in the

contextof the provider–service userrelationship to fully facilitate service users’

engagement in their care.

Introduction

A predominant focus in mental health policy and practice

over the last 20 years has been greater efforts to involve

people in their care planning.Historically,service users’

involvementin their mentalhealth serviceswas limited

(Campbell 2005, Dunne 2006). Understanding the views of

the service user remains essential in contemporary mental

health in order to identify the extent to which a service is

achieving its aims and purpose. The aim of this integrative

review wasto establish whatevidence existsas to the

experiences service users have of mental health services.

Legislationsprotecting service users’rights has been

introduced and implemented in the United Kingdom and

Ireland (Mental Health Act 2007, House of Parliament and

Mental Health Act 2001 Houses of the Oireachtas).

Furthermore, new models or approaches to care have been

advocated including the recovery modelwhich has been

promoted internationally [e.g. MHC (NZ) 1998;

Departmentof Health 2001;MHC (Ireland) 2008].The

main elements of the recovery modelare greater service-

user involvement,modernizing the mentalhealth work-

force, viewing the person beyond the illness,increased

personalization,facilitating choice of treatmentsand

changesto education programmes.The recovery model

seeks to invertthe role ofthe service user from being a

follower to one where they are able to lead,change and

direct their own care (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health

2008). The prominence and importance of patient-centred

care,also identified by Epstein & Street (2011),aimed to

ensure service users’ needs and preferences are respected. A

key aim of patient-centred care is to help service users make

and contribute to, informed decisions about their care.

Research in the early 2000sidentified severalissues

around the relationship between service users and provid-

ers. For example,Dunne (2006)highlighted thatservice

userscontinued to experience poorcommunication and

lack of continuity of care.A preliminary literature search

did not identify a recent review that addressed experiences

acrossmentalhealth services.Therefore,as the debate

regarding theautonomy and rightsof serviceusersin

mentalhealth continues,it is timely to identify whatis

known aboutmentalhealth service users’experiences of

mental health services.

Aim and methods of the review

The aim of this integrative literature review was to identify

how service users experiencemental health services.

Mental health service users are not a homogeneous group

with similar experiences,so the focus ofthis integrative

review was the experiences of adults (18–65 years old) who

accessed and used a mental health service. Reports relating

to specialist services such as homeless services, the utiliza-

tion of mental health laws, detention or involuntary admis-

sion, clinical treatments or reports that outline changes in

work practices in specific areas were excluded as outlined

fully in Table 1. The focus of this review was on database

searchesin order to extract evidencefrom systematic

reviews and primary empirical qualitative and quantitative

studies (Table 1).

An integrative review was undertaken to address the aim

of the review. This approach is increasingly recognized as

appropriate to inform evidence-based practice.The inte-

grative review synthesize findings from a diverse range of

primary experimentaland non-experimentalresearch

methods in order to provide a breadth of perspectives and

a more comprehensive understanding of a healthcare issue

(Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Given the aim was to evaluate

services users’ experiences, an integrative review was con-

sidered to be the appropriatemethod.The approach

reported here reflects key aspects of the systematic review

methodsadvocated by the Cochrane Collaboration and

the Scottish IntercollegiateGuideline Network (SIGN

D Newman et al.

172 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

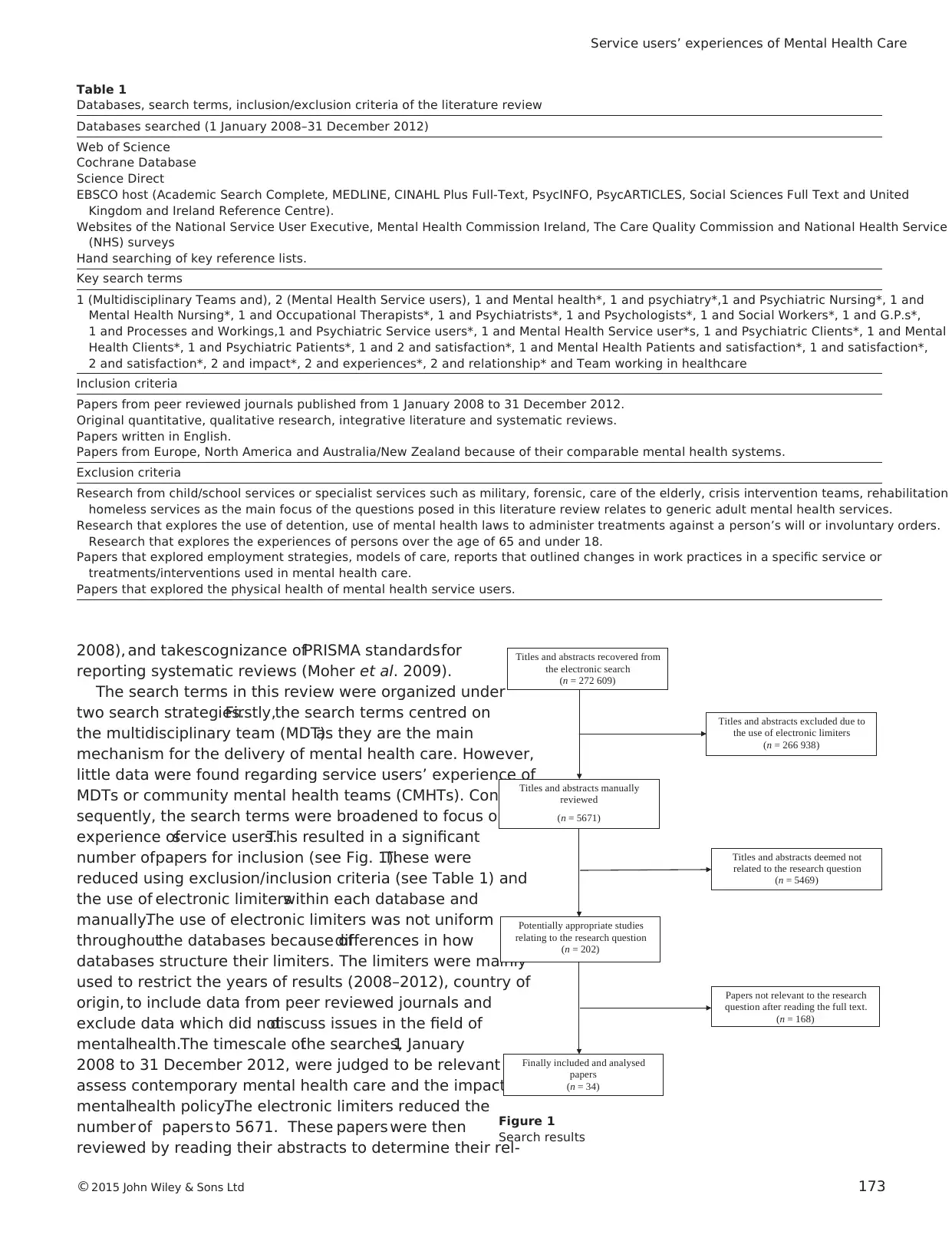

2008), and takescognizance ofPRISMA standardsfor

reporting systematic reviews (Moher et al. 2009).

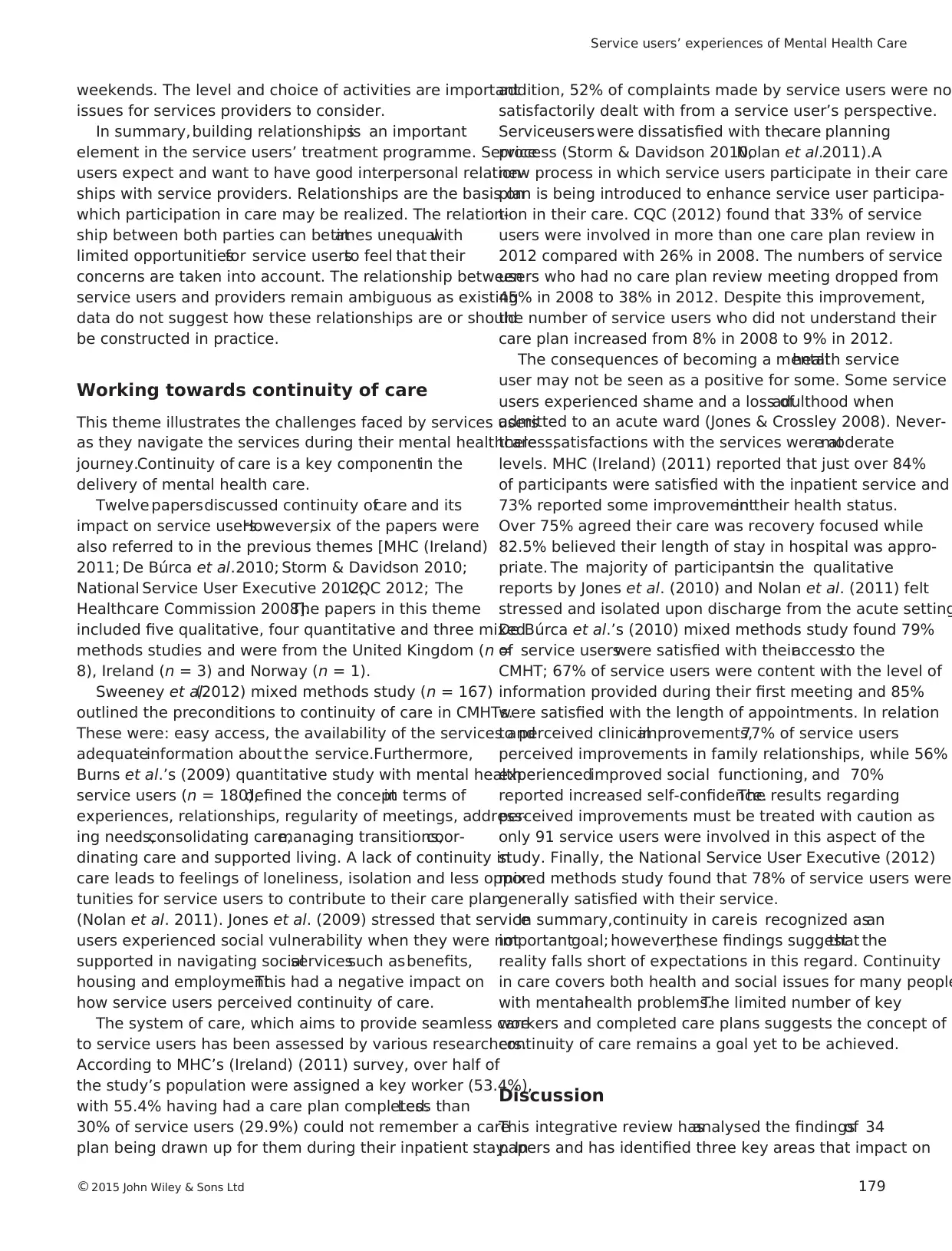

The search terms in this review were organized under

two search strategies.Firstly,the search terms centred on

the multidisciplinary team (MDT)as they are the main

mechanism for the delivery of mental health care. However,

little data were found regarding service users’ experience of

MDTs or community mental health teams (CMHTs). Con-

sequently, the search terms were broadened to focus on the

experience ofservice users.This resulted in a significant

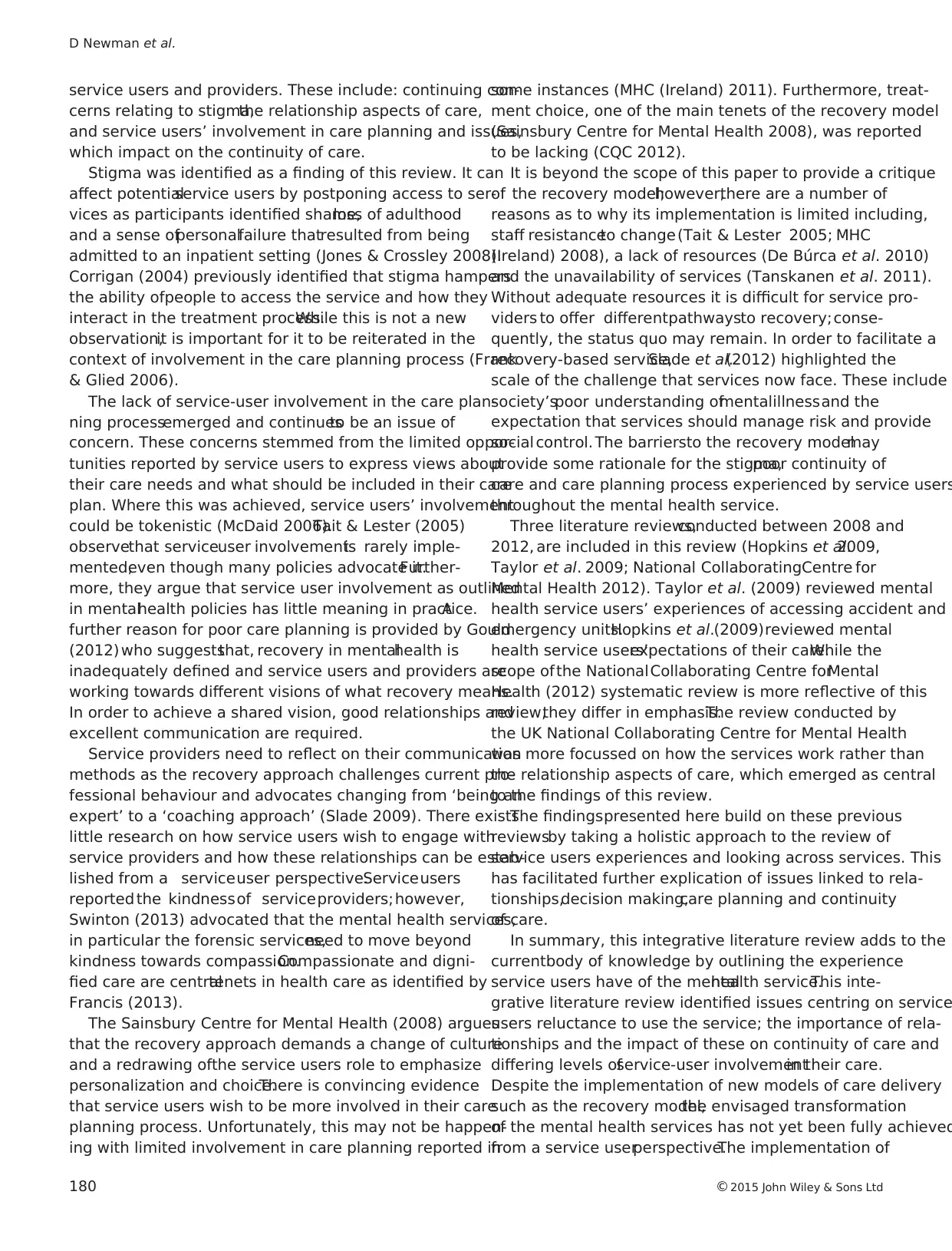

number ofpapers for inclusion (see Fig. 1).These were

reduced using exclusion/inclusion criteria (see Table 1) and

the use of electronic limiterswithin each database and

manually.The use of electronic limiters was not uniform

throughoutthe databases because ofdifferences in how

databases structure their limiters. The limiters were mainly

used to restrict the years of results (2008–2012), country of

origin, to include data from peer reviewed journals and

exclude data which did notdiscuss issues in the field of

mentalhealth.The timescale ofthe searches,1 January

2008 to 31 December 2012, were judged to be relevant to

assess contemporary mental health care and the impact of

mentalhealth policy.The electronic limiters reduced the

number of papers to 5671. These papers were then

reviewed by reading their abstracts to determine their rel-

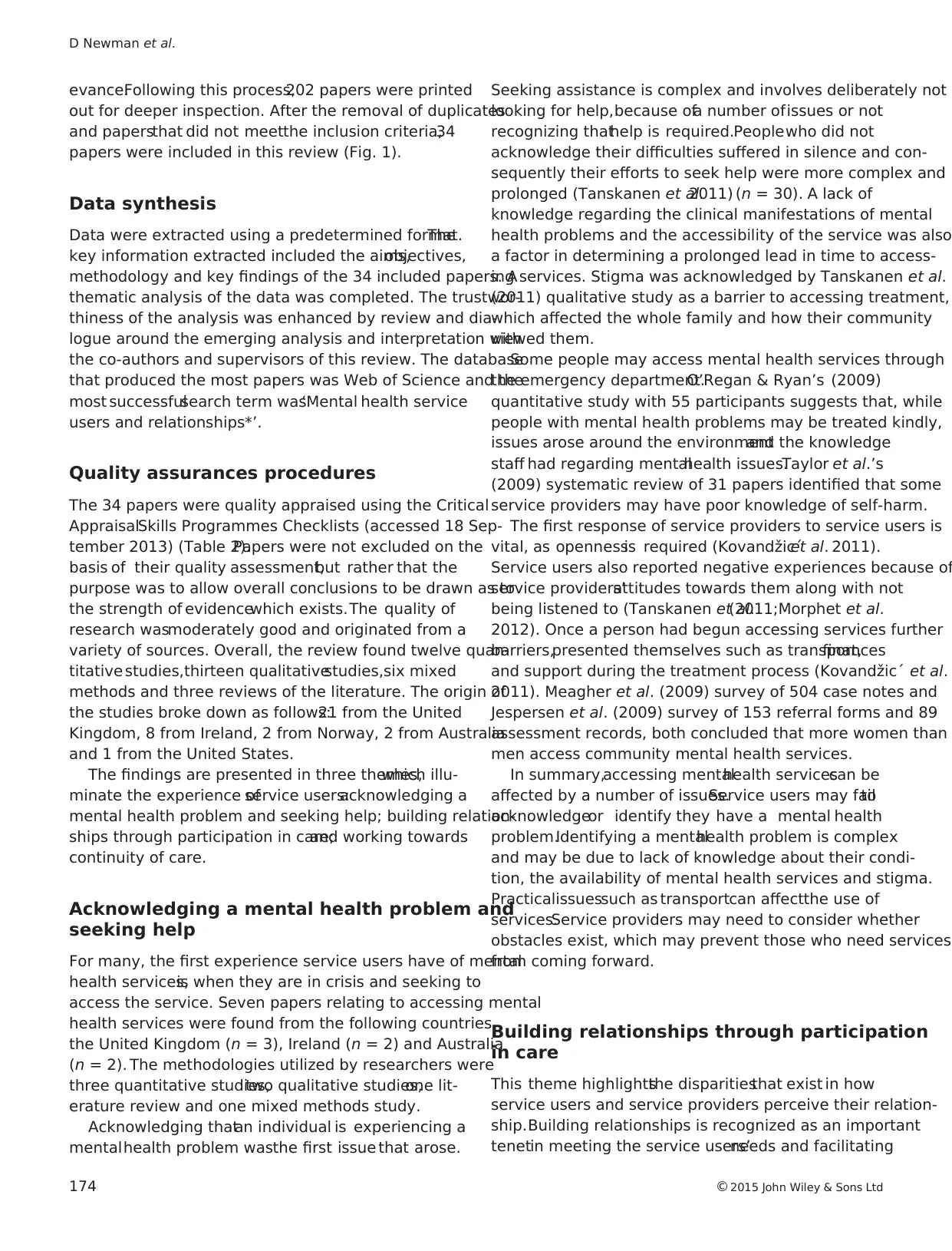

Table 1

Databases, search terms, inclusion/exclusion criteria of the literature review

Databases searched (1 January 2008–31 December 2012)

Web of Science

Cochrane Database

Science Direct

EBSCO host (Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus Full-Text, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Social Sciences Full Text and United

Kingdom and Ireland Reference Centre).

Websites of the National Service User Executive, Mental Health Commission Ireland, The Care Quality Commission and National Health Service

(NHS) surveys

Hand searching of key reference lists.

Key search terms

1 (Multidisciplinary Teams and), 2 (Mental Health Service users), 1 and Mental health*, 1 and psychiatry*,1 and Psychiatric Nursing*, 1 and

Mental Health Nursing*, 1 and Occupational Therapists*, 1 and Psychiatrists*, 1 and Psychologists*, 1 and Social Workers*, 1 and G.P.s*,

1 and Processes and Workings,1 and Psychiatric Service users*, 1 and Mental Health Service user*s, 1 and Psychiatric Clients*, 1 and Mental

Health Clients*, 1 and Psychiatric Patients*, 1 and 2 and satisfaction*, 1 and Mental Health Patients and satisfaction*, 1 and satisfaction*,

2 and satisfaction*, 2 and impact*, 2 and experiences*, 2 and relationship* and Team working in healthcare

Inclusion criteria

Papers from peer reviewed journals published from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2012.

Original quantitative, qualitative research, integrative literature and systematic reviews.

Papers written in English.

Papers from Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand because of their comparable mental health systems.

Exclusion criteria

Research from child/school services or specialist services such as military, forensic, care of the elderly, crisis intervention teams, rehabilitation

homeless services as the main focus of the questions posed in this literature review relates to generic adult mental health services.

Research that explores the use of detention, use of mental health laws to administer treatments against a person’s will or involuntary orders.

Research that explores the experiences of persons over the age of 65 and under 18.

Papers that explored employment strategies, models of care, reports that outlined changes in work practices in a specific service or

treatments/interventions used in mental health care.

Papers that explored the physical health of mental health service users.

Titles and abstracts recovered from

the electronic search

(n = 272 609)

Titles and abstracts excluded due to

the use of electronic limiters

(n = 266 938)

Titles and abstracts manually

reviewed

(n = 5671)

Titles and abstracts deemed not

related to the research question

(n = 5469)

Potentially appropriate studies

relating to the research question

(n = 202)

Papers not relevant to the research

question after reading the full text.

(n = 168)

Finally included and analysed

papers

(n = 34)

Figure 1

Search results

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 173

reporting systematic reviews (Moher et al. 2009).

The search terms in this review were organized under

two search strategies.Firstly,the search terms centred on

the multidisciplinary team (MDT)as they are the main

mechanism for the delivery of mental health care. However,

little data were found regarding service users’ experience of

MDTs or community mental health teams (CMHTs). Con-

sequently, the search terms were broadened to focus on the

experience ofservice users.This resulted in a significant

number ofpapers for inclusion (see Fig. 1).These were

reduced using exclusion/inclusion criteria (see Table 1) and

the use of electronic limiterswithin each database and

manually.The use of electronic limiters was not uniform

throughoutthe databases because ofdifferences in how

databases structure their limiters. The limiters were mainly

used to restrict the years of results (2008–2012), country of

origin, to include data from peer reviewed journals and

exclude data which did notdiscuss issues in the field of

mentalhealth.The timescale ofthe searches,1 January

2008 to 31 December 2012, were judged to be relevant to

assess contemporary mental health care and the impact of

mentalhealth policy.The electronic limiters reduced the

number of papers to 5671. These papers were then

reviewed by reading their abstracts to determine their rel-

Table 1

Databases, search terms, inclusion/exclusion criteria of the literature review

Databases searched (1 January 2008–31 December 2012)

Web of Science

Cochrane Database

Science Direct

EBSCO host (Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus Full-Text, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Social Sciences Full Text and United

Kingdom and Ireland Reference Centre).

Websites of the National Service User Executive, Mental Health Commission Ireland, The Care Quality Commission and National Health Service

(NHS) surveys

Hand searching of key reference lists.

Key search terms

1 (Multidisciplinary Teams and), 2 (Mental Health Service users), 1 and Mental health*, 1 and psychiatry*,1 and Psychiatric Nursing*, 1 and

Mental Health Nursing*, 1 and Occupational Therapists*, 1 and Psychiatrists*, 1 and Psychologists*, 1 and Social Workers*, 1 and G.P.s*,

1 and Processes and Workings,1 and Psychiatric Service users*, 1 and Mental Health Service user*s, 1 and Psychiatric Clients*, 1 and Mental

Health Clients*, 1 and Psychiatric Patients*, 1 and 2 and satisfaction*, 1 and Mental Health Patients and satisfaction*, 1 and satisfaction*,

2 and satisfaction*, 2 and impact*, 2 and experiences*, 2 and relationship* and Team working in healthcare

Inclusion criteria

Papers from peer reviewed journals published from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2012.

Original quantitative, qualitative research, integrative literature and systematic reviews.

Papers written in English.

Papers from Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand because of their comparable mental health systems.

Exclusion criteria

Research from child/school services or specialist services such as military, forensic, care of the elderly, crisis intervention teams, rehabilitation

homeless services as the main focus of the questions posed in this literature review relates to generic adult mental health services.

Research that explores the use of detention, use of mental health laws to administer treatments against a person’s will or involuntary orders.

Research that explores the experiences of persons over the age of 65 and under 18.

Papers that explored employment strategies, models of care, reports that outlined changes in work practices in a specific service or

treatments/interventions used in mental health care.

Papers that explored the physical health of mental health service users.

Titles and abstracts recovered from

the electronic search

(n = 272 609)

Titles and abstracts excluded due to

the use of electronic limiters

(n = 266 938)

Titles and abstracts manually

reviewed

(n = 5671)

Titles and abstracts deemed not

related to the research question

(n = 5469)

Potentially appropriate studies

relating to the research question

(n = 202)

Papers not relevant to the research

question after reading the full text.

(n = 168)

Finally included and analysed

papers

(n = 34)

Figure 1

Search results

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 173

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

evance.Following this process,202 papers were printed

out for deeper inspection. After the removal of duplicates

and papersthat did not meetthe inclusion criteria,34

papers were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Data synthesis

Data were extracted using a predetermined format.The

key information extracted included the aims,objectives,

methodology and key findings of the 34 included papers. A

thematic analysis of the data was completed. The trustwor-

thiness of the analysis was enhanced by review and dia-

logue around the emerging analysis and interpretation with

the co-authors and supervisors of this review. The database

that produced the most papers was Web of Science and the

most successfulsearch term was‘Mental health service

users and relationships*’.

Quality assurances procedures

The 34 papers were quality appraised using the Critical

AppraisalSkills Programmes Checklists (accessed 18 Sep-

tember 2013) (Table 2).Papers were not excluded on the

basis of their quality assessment,but rather that the

purpose was to allow overall conclusions to be drawn as to

the strength of evidencewhich exists.The quality of

research wasmoderately good and originated from a

variety of sources. Overall, the review found twelve quan-

titative studies,thirteen qualitativestudies,six mixed

methods and three reviews of the literature. The origin of

the studies broke down as follows:21 from the United

Kingdom, 8 from Ireland, 2 from Norway, 2 from Australia

and 1 from the United States.

The findings are presented in three themes,which illu-

minate the experience ofservice users:acknowledging a

mental health problem and seeking help; building relation-

ships through participation in care;and working towards

continuity of care.

Acknowledging a mental health problem and

seeking help

For many, the first experience service users have of mental

health services,is when they are in crisis and seeking to

access the service. Seven papers relating to accessing mental

health services were found from the following countries,

the United Kingdom (n = 3), Ireland (n = 2) and Australia

(n = 2). The methodologies utilized by researchers were

three quantitative studies,two qualitative studies,one lit-

erature review and one mixed methods study.

Acknowledging thatan individual is experiencing a

mentalhealth problem wasthe first issue that arose.

Seeking assistance is complex and involves deliberately not

looking for help,because ofa number ofissues or not

recognizing thathelp is required.Peoplewho did not

acknowledge their difficulties suffered in silence and con-

sequently their efforts to seek help were more complex and

prolonged (Tanskanen et al.2011) (n = 30). A lack of

knowledge regarding the clinical manifestations of mental

health problems and the accessibility of the service was also

a factor in determining a prolonged lead in time to access-

ing services. Stigma was acknowledged by Tanskanen et al.

(2011) qualitative study as a barrier to accessing treatment,

which affected the whole family and how their community

viewed them.

Some people may access mental health services through

the emergency department.O’Regan & Ryan’s (2009)

quantitative study with 55 participants suggests that, while

people with mental health problems may be treated kindly,

issues arose around the environmentand the knowledge

staff had regarding mentalhealth issues.Taylor et al.’s

(2009) systematic review of 31 papers identified that some

service providers may have poor knowledge of self-harm.

The first response of service providers to service users is

vital, as opennessis required (Kovandžic´et al. 2011).

Service users also reported negative experiences because of

service providers’attitudes towards them along with not

being listened to (Tanskanen et al.(2011;Morphet et al.

2012). Once a person had begun accessing services further

barriers,presented themselves such as transport,finances

and support during the treatment process (Kovandžic´ et al.

2011). Meagher et al. (2009) survey of 504 case notes and

Jespersen et al. (2009) survey of 153 referral forms and 89

assessment records, both concluded that more women than

men access community mental health services.

In summary,accessing mentalhealth servicescan be

affected by a number of issues.Service users may failto

acknowledgeor identify they have a mental health

problem.Identifying a mentalhealth problem is complex

and may be due to lack of knowledge about their condi-

tion, the availability of mental health services and stigma.

Practicalissuessuch as transportcan affectthe use of

services.Service providers may need to consider whether

obstacles exist, which may prevent those who need services

from coming forward.

Building relationships through participation

in care

This theme highlightsthe disparitiesthat exist in how

service users and service providers perceive their relation-

ship.Building relationships is recognized as an important

tenetin meeting the service users’needs and facilitating

D Newman et al.

174 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

out for deeper inspection. After the removal of duplicates

and papersthat did not meetthe inclusion criteria,34

papers were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Data synthesis

Data were extracted using a predetermined format.The

key information extracted included the aims,objectives,

methodology and key findings of the 34 included papers. A

thematic analysis of the data was completed. The trustwor-

thiness of the analysis was enhanced by review and dia-

logue around the emerging analysis and interpretation with

the co-authors and supervisors of this review. The database

that produced the most papers was Web of Science and the

most successfulsearch term was‘Mental health service

users and relationships*’.

Quality assurances procedures

The 34 papers were quality appraised using the Critical

AppraisalSkills Programmes Checklists (accessed 18 Sep-

tember 2013) (Table 2).Papers were not excluded on the

basis of their quality assessment,but rather that the

purpose was to allow overall conclusions to be drawn as to

the strength of evidencewhich exists.The quality of

research wasmoderately good and originated from a

variety of sources. Overall, the review found twelve quan-

titative studies,thirteen qualitativestudies,six mixed

methods and three reviews of the literature. The origin of

the studies broke down as follows:21 from the United

Kingdom, 8 from Ireland, 2 from Norway, 2 from Australia

and 1 from the United States.

The findings are presented in three themes,which illu-

minate the experience ofservice users:acknowledging a

mental health problem and seeking help; building relation-

ships through participation in care;and working towards

continuity of care.

Acknowledging a mental health problem and

seeking help

For many, the first experience service users have of mental

health services,is when they are in crisis and seeking to

access the service. Seven papers relating to accessing mental

health services were found from the following countries,

the United Kingdom (n = 3), Ireland (n = 2) and Australia

(n = 2). The methodologies utilized by researchers were

three quantitative studies,two qualitative studies,one lit-

erature review and one mixed methods study.

Acknowledging thatan individual is experiencing a

mentalhealth problem wasthe first issue that arose.

Seeking assistance is complex and involves deliberately not

looking for help,because ofa number ofissues or not

recognizing thathelp is required.Peoplewho did not

acknowledge their difficulties suffered in silence and con-

sequently their efforts to seek help were more complex and

prolonged (Tanskanen et al.2011) (n = 30). A lack of

knowledge regarding the clinical manifestations of mental

health problems and the accessibility of the service was also

a factor in determining a prolonged lead in time to access-

ing services. Stigma was acknowledged by Tanskanen et al.

(2011) qualitative study as a barrier to accessing treatment,

which affected the whole family and how their community

viewed them.

Some people may access mental health services through

the emergency department.O’Regan & Ryan’s (2009)

quantitative study with 55 participants suggests that, while

people with mental health problems may be treated kindly,

issues arose around the environmentand the knowledge

staff had regarding mentalhealth issues.Taylor et al.’s

(2009) systematic review of 31 papers identified that some

service providers may have poor knowledge of self-harm.

The first response of service providers to service users is

vital, as opennessis required (Kovandžic´et al. 2011).

Service users also reported negative experiences because of

service providers’attitudes towards them along with not

being listened to (Tanskanen et al.(2011;Morphet et al.

2012). Once a person had begun accessing services further

barriers,presented themselves such as transport,finances

and support during the treatment process (Kovandžic´ et al.

2011). Meagher et al. (2009) survey of 504 case notes and

Jespersen et al. (2009) survey of 153 referral forms and 89

assessment records, both concluded that more women than

men access community mental health services.

In summary,accessing mentalhealth servicescan be

affected by a number of issues.Service users may failto

acknowledgeor identify they have a mental health

problem.Identifying a mentalhealth problem is complex

and may be due to lack of knowledge about their condi-

tion, the availability of mental health services and stigma.

Practicalissuessuch as transportcan affectthe use of

services.Service providers may need to consider whether

obstacles exist, which may prevent those who need services

from coming forward.

Building relationships through participation

in care

This theme highlightsthe disparitiesthat exist in how

service users and service providers perceive their relation-

ship.Building relationships is recognized as an important

tenetin meeting the service users’needs and facilitating

D Newman et al.

174 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

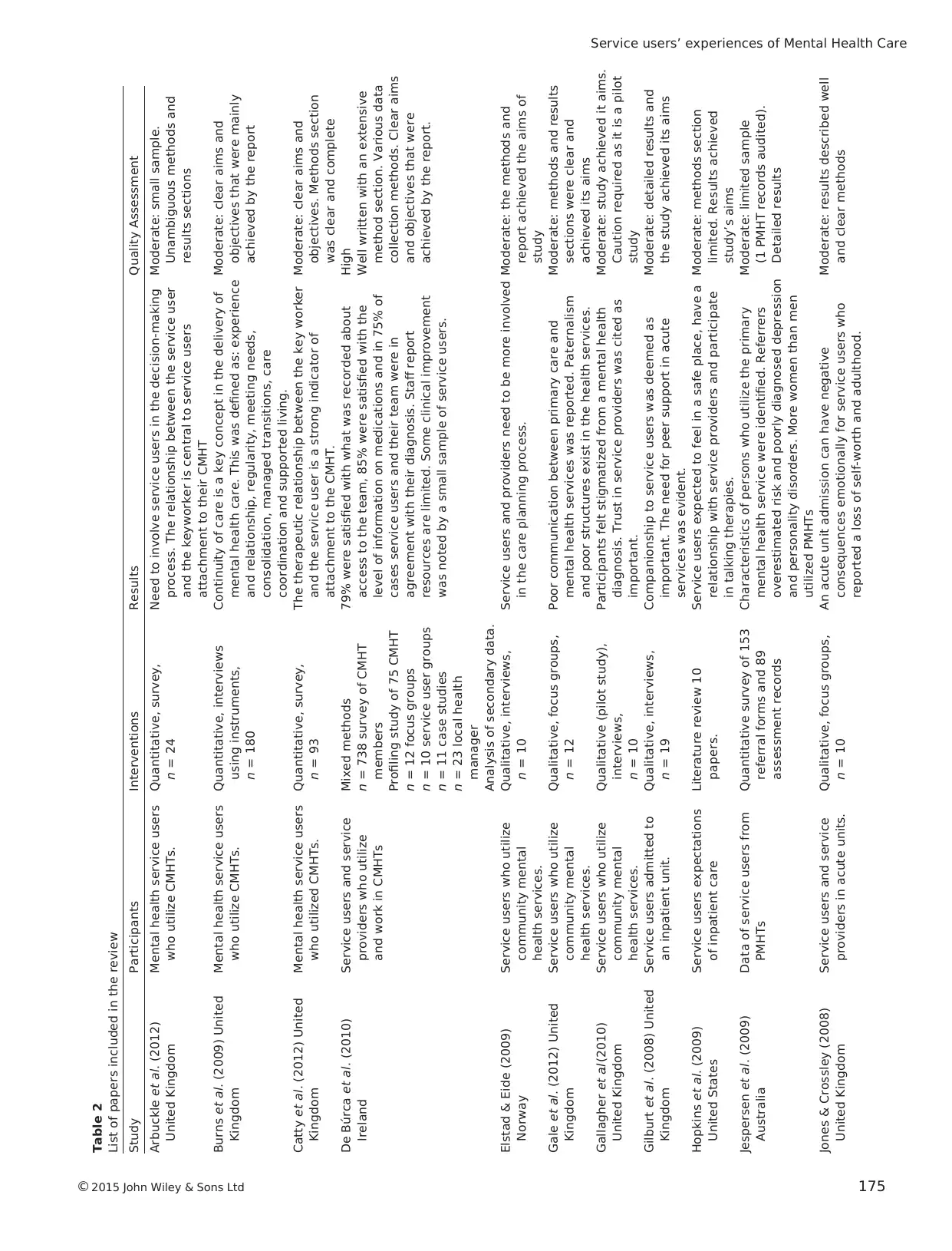

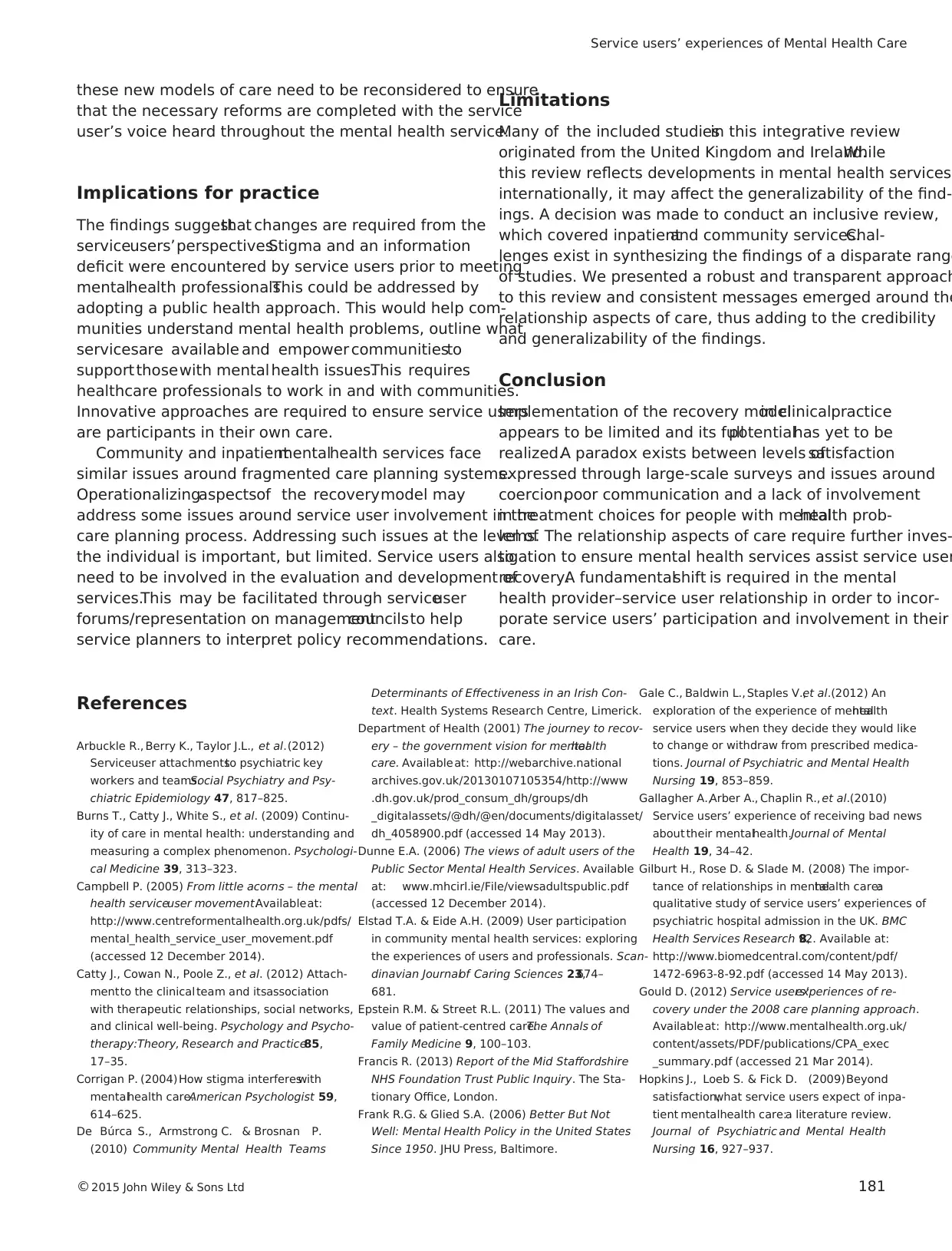

Table 2

List of papers included in the review

Study Participants Interventions Results Quality Assessment

Arbuckle et al. (2012)

United Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilize CMHTs.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 24

Need to involve service users in the decision-making

process. The relationship between the service user

and the keyworker is central to service users

attachment to their CMHT

Moderate: small sample.

Unambiguous methods and

results sections

Burns et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilize CMHTs.

Quantitative, interviews

using instruments,

n = 180

Continuity of care is a key concept in the delivery of

mental health care. This was defined as: experience

and relationship, regularity, meeting needs,

consolidation, managed transitions, care

coordination and supported living.

Moderate: clear aims and

objectives that were mainly

achieved by the report

Catty et al. (2012) United

Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilized CMHTs.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 93

The therapeutic relationship between the key worker

and the service user is a strong indicator of

attachment to the CMHT.

Moderate: clear aims and

objectives. Methods section

was clear and complete

De Búrca et al. (2010)

Ireland

Service users and service

providers who utilize

and work in CMHTs

Mixed methods

n = 738 survey of CMHT

members

Profiling study of 75 CMHT

n = 12 focus groups

n = 10 service user groups

n = 11 case studies

n = 23 local health

manager

Analysis of secondary data.

79% were satisfied with what was recorded about

access to the team, 85% were satisfied with the

level of information on medications and in 75% of

cases service users and their team were in

agreement with their diagnosis. Staff report

resources are limited. Some clinical improvement

was noted by a small sample of service users.

High

Well written with an extensive

method section. Various data

collection methods. Clear aims

and objectives that were

achieved by the report.

Elstad & Eide (2009)

Norway

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 10

Service users and providers need to be more involved

in the care planning process.

Moderate: the methods and

report achieved the aims of

study

Gale et al. (2012) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative, focus groups,

n = 12

Poor communication between primary care and

mental health services was reported. Paternalism

and poor structures exist in the health services.

Moderate: methods and results

sections were clear and

achieved its aims

Gallagher et al. (2010)

United Kingdom

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative (pilot study),

interviews,

n = 10

Participants felt stigmatized from a mental health

diagnosis. Trust in service providers was cited as

important.

Moderate: study achieved it aims.

Caution required as it is a pilot

study

Gilburt et al. (2008) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

an inpatient unit.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 19

Companionship to service users was deemed as

important. The need for peer support in acute

services was evident.

Moderate: detailed results and

the study achieved its aims

Hopkins et al. (2009)

United States

Service users expectations

of inpatient care

Literature review 10

papers.

Service users expected to feel in a safe place, have a

relationship with service providers and participate

in talking therapies.

Moderate: methods section

limited. Results achieved

study’s aims

Jespersen et al. (2009)

Australia

Data of service users from

PMHTs

Quantitative survey of 153

referral forms and 89

assessment records

Characteristics of persons who utilize the primary

mental health service were identified. Referrers

overestimated risk and poorly diagnosed depression

and personality disorders. More women than men

utilized PMHTs

Moderate: limited sample

(1 PMHT records audited).

Detailed results

Jones & Crossley (2008)

United Kingdom

Service users and service

providers in acute units.

Qualitative, focus groups,

n = 10

An acute unit admission can have negative

consequences emotionally for service users who

reported a loss of self-worth and adulthood.

Moderate: results described well

and clear methods

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 175

List of papers included in the review

Study Participants Interventions Results Quality Assessment

Arbuckle et al. (2012)

United Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilize CMHTs.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 24

Need to involve service users in the decision-making

process. The relationship between the service user

and the keyworker is central to service users

attachment to their CMHT

Moderate: small sample.

Unambiguous methods and

results sections

Burns et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilize CMHTs.

Quantitative, interviews

using instruments,

n = 180

Continuity of care is a key concept in the delivery of

mental health care. This was defined as: experience

and relationship, regularity, meeting needs,

consolidation, managed transitions, care

coordination and supported living.

Moderate: clear aims and

objectives that were mainly

achieved by the report

Catty et al. (2012) United

Kingdom

Mental health service users

who utilized CMHTs.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 93

The therapeutic relationship between the key worker

and the service user is a strong indicator of

attachment to the CMHT.

Moderate: clear aims and

objectives. Methods section

was clear and complete

De Búrca et al. (2010)

Ireland

Service users and service

providers who utilize

and work in CMHTs

Mixed methods

n = 738 survey of CMHT

members

Profiling study of 75 CMHT

n = 12 focus groups

n = 10 service user groups

n = 11 case studies

n = 23 local health

manager

Analysis of secondary data.

79% were satisfied with what was recorded about

access to the team, 85% were satisfied with the

level of information on medications and in 75% of

cases service users and their team were in

agreement with their diagnosis. Staff report

resources are limited. Some clinical improvement

was noted by a small sample of service users.

High

Well written with an extensive

method section. Various data

collection methods. Clear aims

and objectives that were

achieved by the report.

Elstad & Eide (2009)

Norway

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 10

Service users and providers need to be more involved

in the care planning process.

Moderate: the methods and

report achieved the aims of

study

Gale et al. (2012) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative, focus groups,

n = 12

Poor communication between primary care and

mental health services was reported. Paternalism

and poor structures exist in the health services.

Moderate: methods and results

sections were clear and

achieved its aims

Gallagher et al. (2010)

United Kingdom

Service users who utilize

community mental

health services.

Qualitative (pilot study),

interviews,

n = 10

Participants felt stigmatized from a mental health

diagnosis. Trust in service providers was cited as

important.

Moderate: study achieved it aims.

Caution required as it is a pilot

study

Gilburt et al. (2008) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

an inpatient unit.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 19

Companionship to service users was deemed as

important. The need for peer support in acute

services was evident.

Moderate: detailed results and

the study achieved its aims

Hopkins et al. (2009)

United States

Service users expectations

of inpatient care

Literature review 10

papers.

Service users expected to feel in a safe place, have a

relationship with service providers and participate

in talking therapies.

Moderate: methods section

limited. Results achieved

study’s aims

Jespersen et al. (2009)

Australia

Data of service users from

PMHTs

Quantitative survey of 153

referral forms and 89

assessment records

Characteristics of persons who utilize the primary

mental health service were identified. Referrers

overestimated risk and poorly diagnosed depression

and personality disorders. More women than men

utilized PMHTs

Moderate: limited sample

(1 PMHT records audited).

Detailed results

Jones & Crossley (2008)

United Kingdom

Service users and service

providers in acute units.

Qualitative, focus groups,

n = 10

An acute unit admission can have negative

consequences emotionally for service users who

reported a loss of self-worth and adulthood.

Moderate: results described well

and clear methods

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 175

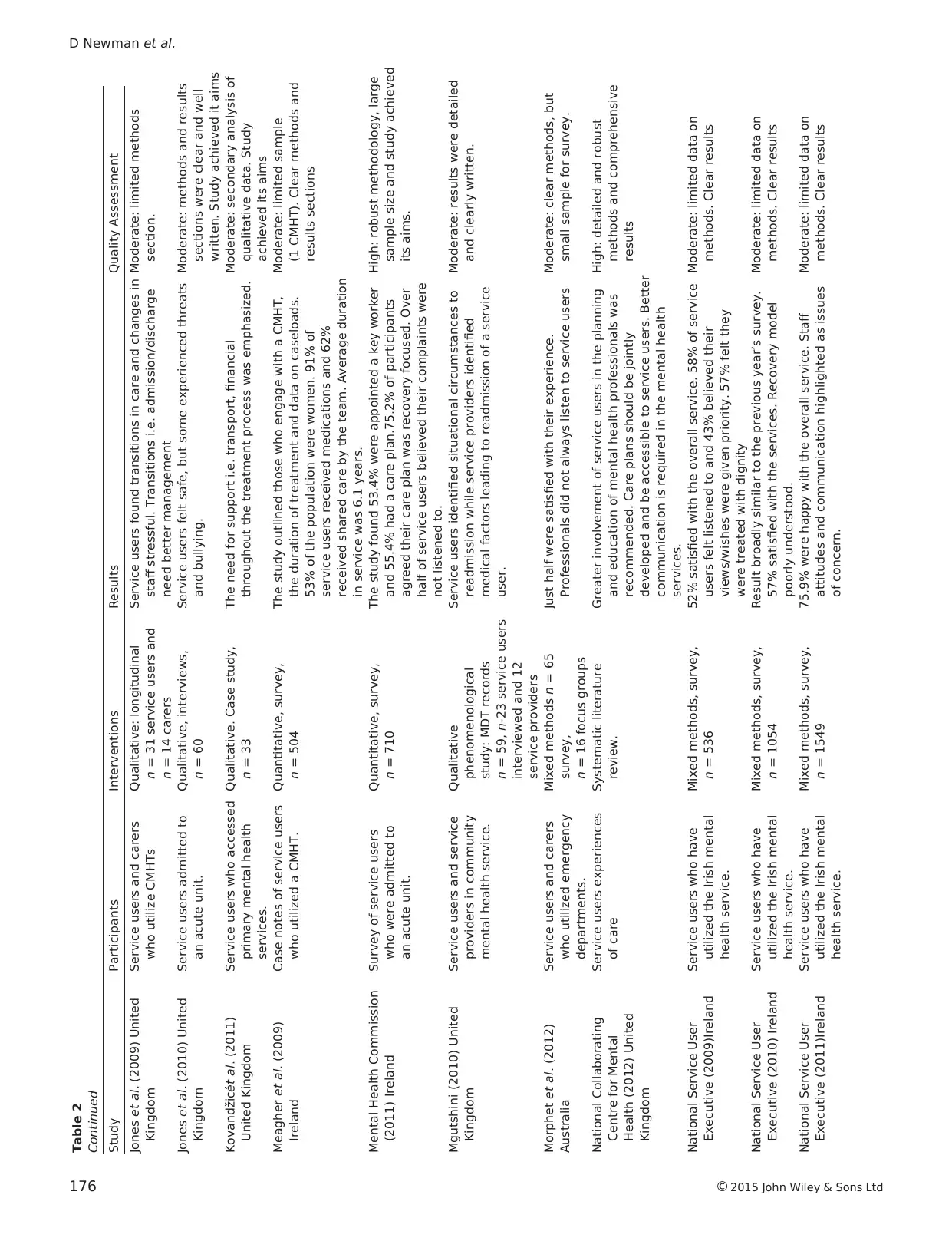

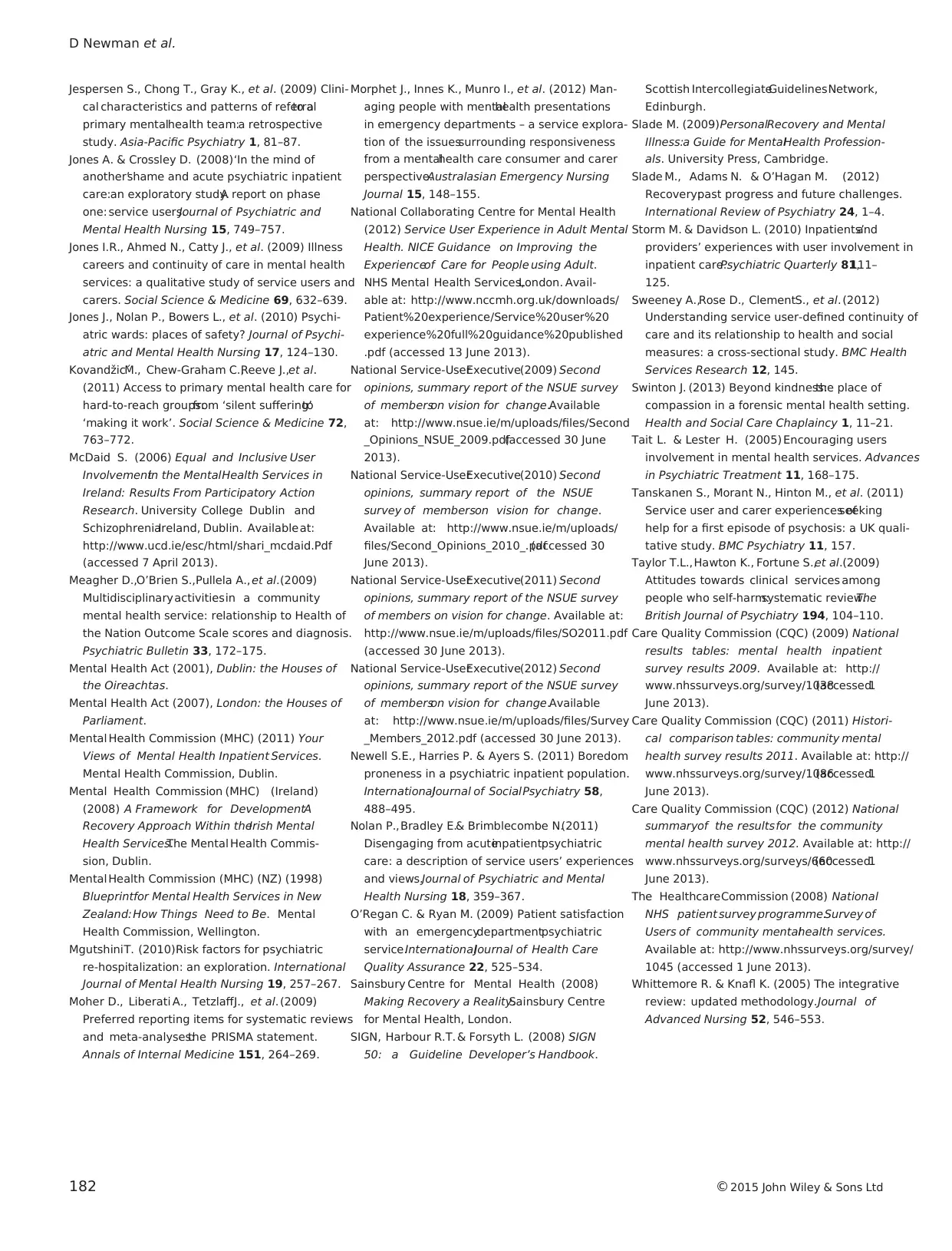

Table 2

Continued

Study Participants Interventions Results Quality Assessment

Jones et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Service users and carers

who utilize CMHTs

Qualitative: longitudinal

n = 31 service users and

n = 14 carers

Service users found transitions in care and changes in

staff stressful. Transitions i.e. admission/discharge

need better management

Moderate: limited methods

section.

Jones et al. (2010) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

an acute unit.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 60

Service users felt safe, but some experienced threats

and bullying.

Moderate: methods and results

sections were clear and well

written. Study achieved it aims

Kovandžic´et al. (2011)

United Kingdom

Service users who accessed

primary mental health

services.

Qualitative. Case study,

n = 33

The need for support i.e. transport, financial

throughout the treatment process was emphasized.

Moderate: secondary analysis of

qualitative data. Study

achieved its aims

Meagher et al. (2009)

Ireland

Case notes of service users

who utilized a CMHT.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 504

The study outlined those who engage with a CMHT,

the duration of treatment and data on caseloads.

53% of the population were women. 91% of

service users received medications and 62%

received shared care by the team. Average duration

in service was 6.1 years.

Moderate: limited sample

(1 CMHT). Clear methods and

results sections

Mental Health Commission

(2011) Ireland

Survey of service users

who were admitted to

an acute unit.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 710

The study found 53.4% were appointed a key worker

and 55.4% had a care plan.75.2% of participants

agreed their care plan was recovery focused. Over

half of service users believed their complaints were

not listened to.

High: robust methodology, large

sample size and study achieved

its aims.

Mgutshini (2010) United

Kingdom

Service users and service

providers in community

mental health service.

Qualitative

phenomenological

study: MDT records

n = 59, n-23 service users

interviewed and 12

service providers

Service users identified situational circumstances to

readmission while service providers identified

medical factors leading to readmission of a service

user.

Moderate: results were detailed

and clearly written.

Morphet et al. (2012)

Australia

Service users and carers

who utilized emergency

departments.

Mixed methods n = 65

survey,

n = 16 focus groups

Just half were satisfied with their experience.

Professionals did not always listen to service users

Moderate: clear methods, but

small sample for survey.

National Collaborating

Centre for Mental

Health (2012) United

Kingdom

Service users experiences

of care

Systematic literature

review.

Greater involvement of service users in the planning

and education of mental health professionals was

recommended. Care plans should be jointly

developed and be accessible to service users. Better

communication is required in the mental health

services.

High: detailed and robust

methods and comprehensive

results

National Service User

Executive (2009)Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 536

52% satisfied with the overall service. 58% of service

users felt listened to and 43% believed their

views/wishes were given priority. 57% felt they

were treated with dignity

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

National Service User

Executive (2010) Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 1054

Result broadly similar to the previous year’s survey.

57% satisfied with the services. Recovery model

poorly understood.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

National Service User

Executive (2011)Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 1549

75.9% were happy with the overall service. Staff

attitudes and communication highlighted as issues

of concern.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

D Newman et al.

176 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Continued

Study Participants Interventions Results Quality Assessment

Jones et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Service users and carers

who utilize CMHTs

Qualitative: longitudinal

n = 31 service users and

n = 14 carers

Service users found transitions in care and changes in

staff stressful. Transitions i.e. admission/discharge

need better management

Moderate: limited methods

section.

Jones et al. (2010) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

an acute unit.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 60

Service users felt safe, but some experienced threats

and bullying.

Moderate: methods and results

sections were clear and well

written. Study achieved it aims

Kovandžic´et al. (2011)

United Kingdom

Service users who accessed

primary mental health

services.

Qualitative. Case study,

n = 33

The need for support i.e. transport, financial

throughout the treatment process was emphasized.

Moderate: secondary analysis of

qualitative data. Study

achieved its aims

Meagher et al. (2009)

Ireland

Case notes of service users

who utilized a CMHT.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 504

The study outlined those who engage with a CMHT,

the duration of treatment and data on caseloads.

53% of the population were women. 91% of

service users received medications and 62%

received shared care by the team. Average duration

in service was 6.1 years.

Moderate: limited sample

(1 CMHT). Clear methods and

results sections

Mental Health Commission

(2011) Ireland

Survey of service users

who were admitted to

an acute unit.

Quantitative, survey,

n = 710

The study found 53.4% were appointed a key worker

and 55.4% had a care plan.75.2% of participants

agreed their care plan was recovery focused. Over

half of service users believed their complaints were

not listened to.

High: robust methodology, large

sample size and study achieved

its aims.

Mgutshini (2010) United

Kingdom

Service users and service

providers in community

mental health service.

Qualitative

phenomenological

study: MDT records

n = 59, n-23 service users

interviewed and 12

service providers

Service users identified situational circumstances to

readmission while service providers identified

medical factors leading to readmission of a service

user.

Moderate: results were detailed

and clearly written.

Morphet et al. (2012)

Australia

Service users and carers

who utilized emergency

departments.

Mixed methods n = 65

survey,

n = 16 focus groups

Just half were satisfied with their experience.

Professionals did not always listen to service users

Moderate: clear methods, but

small sample for survey.

National Collaborating

Centre for Mental

Health (2012) United

Kingdom

Service users experiences

of care

Systematic literature

review.

Greater involvement of service users in the planning

and education of mental health professionals was

recommended. Care plans should be jointly

developed and be accessible to service users. Better

communication is required in the mental health

services.

High: detailed and robust

methods and comprehensive

results

National Service User

Executive (2009)Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 536

52% satisfied with the overall service. 58% of service

users felt listened to and 43% believed their

views/wishes were given priority. 57% felt they

were treated with dignity

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

National Service User

Executive (2010) Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 1054

Result broadly similar to the previous year’s survey.

57% satisfied with the services. Recovery model

poorly understood.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

National Service User

Executive (2011)Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods, survey,

n = 1549

75.9% were happy with the overall service. Staff

attitudes and communication highlighted as issues

of concern.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

D Newman et al.

176 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

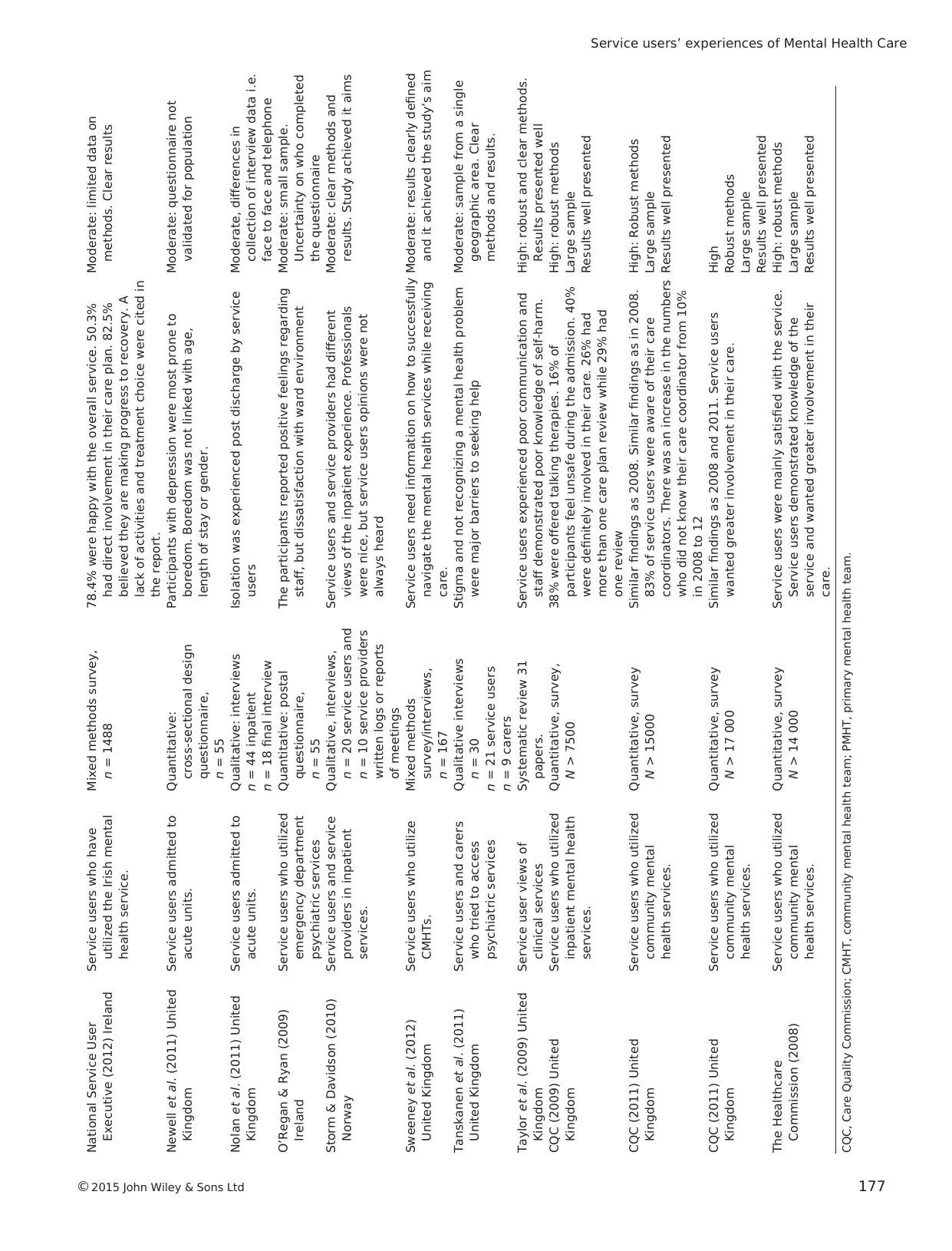

National Service User

Executive (2012) Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods survey,

n = 1488

78.4% were happy with the overall service. 50.3%

had direct involvement in their care plan. 82.5%

believed they are making progress to recovery. A

lack of activities and treatment choice were cited in

the report.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

Newell et al. (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

acute units.

Quantitative:

cross-sectional design

questionnaire,

n = 55

Participants with depression were most prone to

boredom. Boredom was not linked with age,

length of stay or gender.

Moderate: questionnaire not

validated for population

Nolan et al. (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

acute units.

Qualitative: interviews

n = 44 inpatient

n = 18 final interview

Isolation was experienced post discharge by service

users

Moderate, differences in

collection of interview data i.e.

face to face and telephone

O’Regan & Ryan (2009)

Ireland

Service users who utilized

emergency department

psychiatric services

Quantitative: postal

questionnaire,

n = 55

The participants reported positive feelings regarding

staff, but dissatisfaction with ward environment

Moderate: small sample.

Uncertainty on who completed

the questionnaire

Storm & Davidson (2010)

Norway

Service users and service

providers in inpatient

services.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 20 service users and

n = 10 service providers

written logs or reports

of meetings

Service users and service providers had different

views of the inpatient experience. Professionals

were nice, but service users opinions were not

always heard

Moderate: clear methods and

results. Study achieved it aims

Sweeney et al. (2012)

United Kingdom

Service users who utilize

CMHTs.

Mixed methods

survey/interviews,

n = 167

Service users need information on how to successfully

navigate the mental health services while receiving

care.

Moderate: results clearly defined

and it achieved the study’s aim

Tanskanen et al. (2011)

United Kingdom

Service users and carers

who tried to access

psychiatric services

Qualitative interviews

n = 30

n = 21 service users

n = 9 carers

Stigma and not recognizing a mental health problem

were major barriers to seeking help

Moderate: sample from a single

geographic area. Clear

methods and results.

Taylor et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Service user views of

clinical services

Systematic review 31

papers.

Service users experienced poor communication and

staff demonstrated poor knowledge of self-harm.

High: robust and clear methods.

Results presented well

CQC (2009) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

inpatient mental health

services.

Quantitative, survey,

N > 7500

38% were offered talking therapies. 16% of

participants feel unsafe during the admission. 40%

were definitely involved in their care. 26% had

more than one care plan review while 29% had

one review

High: robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 15000

Similar findings as 2008. Similar findings as in 2008.

83% of service users were aware of their care

coordinators. There was an increase in the numbers

who did not know their care coordinator from 10%

in 2008 to 12

High: Robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 17 000

Similar findings as 2008 and 2011. Service users

wanted greater involvement in their care.

High

Robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

The Healthcare

Commission (2008)

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 14 000

Service users were mainly satisfied with the service.

Service users demonstrated knowledge of the

service and wanted greater involvement in their

care.

High: robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC, Care Quality Commission; CMHT, community mental health team; PMHT, primary mental health team.

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 177

Executive (2012) Ireland

Service users who have

utilized the Irish mental

health service.

Mixed methods survey,

n = 1488

78.4% were happy with the overall service. 50.3%

had direct involvement in their care plan. 82.5%

believed they are making progress to recovery. A

lack of activities and treatment choice were cited in

the report.

Moderate: limited data on

methods. Clear results

Newell et al. (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

acute units.

Quantitative:

cross-sectional design

questionnaire,

n = 55

Participants with depression were most prone to

boredom. Boredom was not linked with age,

length of stay or gender.

Moderate: questionnaire not

validated for population

Nolan et al. (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users admitted to

acute units.

Qualitative: interviews

n = 44 inpatient

n = 18 final interview

Isolation was experienced post discharge by service

users

Moderate, differences in

collection of interview data i.e.

face to face and telephone

O’Regan & Ryan (2009)

Ireland

Service users who utilized

emergency department

psychiatric services

Quantitative: postal

questionnaire,

n = 55

The participants reported positive feelings regarding

staff, but dissatisfaction with ward environment

Moderate: small sample.

Uncertainty on who completed

the questionnaire

Storm & Davidson (2010)

Norway

Service users and service

providers in inpatient

services.

Qualitative, interviews,

n = 20 service users and

n = 10 service providers

written logs or reports

of meetings

Service users and service providers had different

views of the inpatient experience. Professionals

were nice, but service users opinions were not

always heard

Moderate: clear methods and

results. Study achieved it aims

Sweeney et al. (2012)

United Kingdom

Service users who utilize

CMHTs.

Mixed methods

survey/interviews,

n = 167

Service users need information on how to successfully

navigate the mental health services while receiving

care.

Moderate: results clearly defined

and it achieved the study’s aim

Tanskanen et al. (2011)

United Kingdom

Service users and carers

who tried to access

psychiatric services

Qualitative interviews

n = 30

n = 21 service users

n = 9 carers

Stigma and not recognizing a mental health problem

were major barriers to seeking help

Moderate: sample from a single

geographic area. Clear

methods and results.

Taylor et al. (2009) United

Kingdom

Service user views of

clinical services

Systematic review 31

papers.

Service users experienced poor communication and

staff demonstrated poor knowledge of self-harm.

High: robust and clear methods.

Results presented well

CQC (2009) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

inpatient mental health

services.

Quantitative, survey,

N > 7500

38% were offered talking therapies. 16% of

participants feel unsafe during the admission. 40%

were definitely involved in their care. 26% had

more than one care plan review while 29% had

one review

High: robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 15000

Similar findings as 2008. Similar findings as in 2008.

83% of service users were aware of their care

coordinators. There was an increase in the numbers

who did not know their care coordinator from 10%

in 2008 to 12

High: Robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC (2011) United

Kingdom

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 17 000

Similar findings as 2008 and 2011. Service users

wanted greater involvement in their care.

High

Robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

The Healthcare

Commission (2008)

Service users who utilized

community mental

health services.

Quantitative, survey

N > 14 000

Service users were mainly satisfied with the service.

Service users demonstrated knowledge of the

service and wanted greater involvement in their

care.

High: robust methods

Large sample

Results well presented

CQC, Care Quality Commission; CMHT, community mental health team; PMHT, primary mental health team.

Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care

©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 177

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

participation in their care. Furthermore, the theme illumi-

nates the difficulties and barriers in facilitating this process.

Twenty-one studies from a range of countries identified

issuesaround relationshipsbetween serviceusers and

service providers (United Kingdom n = 12,Ireland n = 6,

United States n = 1, and Norway n = 2). Of the 21 studies,

8 were quantitative, 6 qualitative, 5 mixed methods and 2

were literature reviews.

Commonly,studiesreported on the importanceof

building relationshipsbetween service usersand service

providers in order to meet service users’ needs

and expectations (Arbuckle et al. 2012 n = 24, Catty et al.

2012 n = 93, Gale et al. 2012 n = 12, National

Collaborating Centre for MentalHealth 2012).Hopkins

et al. (2009),in their review of 10 studies,found that

therapeutic relationships were notalways evidentwithin

mental health settings. Being valued and connected to staff

and peerswas an importantcomponentof the service

users treatmentprogramme(Hopkins et al. 2009). In

addition,Arbuckle et al.(2012)and Catty et al.(2012)

found that the relationship between a service user and a

key worker was centralto service users’connection with

their CMHT.

Service users expressed difficulties in building relation-

ships with service providers,and this can be limiting to

their participation in theircare. The difficultiesranged

from unsupported attitudes ofservice providers to inad-

equatecommunication abouttheir treatment(National

Service User Executive 2009,2010,2011,2012).Within

the inpatient settings,relationships between service users

and service providers were driven by power and lack of

choice.In a study conducted in the United Kingdom,

Gilburt et al.(2008)interviewed patients (n = 19)who

highlighted thatsome staff may use coercion.Service

users reported that fear was an element of their relation-

ship with staff.Other concerns expressed by the patients

were limited information on medication, lack of choice of

treatment,restricted freedom and violence on the ward.

Threats and coercion were cited as influenceswhich

inhibited the service users’role in the decision-making

process (Storm & Davidson 2010).In another qualitative

study, participants expressed the need to trust service pro-

viderswhen providing new information such asa new

mentalhealth diagnosis (Gallagher et al.2010).

Nevertheless, a majority of participants (57%) felt their

psychiatrist listened to them, while 48% of participants felt

that nurses always listened to them according to the Care

Quality Commission (CQC)inpatientquantitative study

(CQC 2009). Engagement can be difficult as service users

and service providers can have differing viewpoints.An

example of this disparity was demonstrated in Mgutshini’s

(2010) qualitative study. From the service providers’ view-

point,rehospitalization was centred on medicalproblems

such as non-concordanceto medication,while service

users’concerns were focused on the psychosocialfactors

that they experienced prior to readmission.

However,some service users reported positive experi-

ences. For example, half of the respondents in the National

Service User Executive (2012) survey felt that service pro-

viders’ attitudes were changing. Of those, 60% felt that staff

attitudes were changing for the better while 36% stated the

shift in attitudes was a mix of positive and negative. Service

users have become more aware of the structure of commu-

nity services and are increasingly engaging with them, for

example in 2008, the CQC reported that 74% of respond-

ents knew their Care Coordinator, while 85% were aware

of their Care Coordinator in 2012. MHC (Ireland) (2011)

reported that 81% of participants had access to a member

of staff at all times, and 87% of participants reported that

they trusted their healthcare team.

The CQC and the HealthcareCommission annual

surveys ofCMHTs on inpatient services showed greater

serviceuser involvementin the care planning process.

These surveyshad substantialnumbersof participants

(2008 N > 14 000, 2009 N = 7500, 2011 N > 15 000, 2012

N > 17 000). CQC (2009) inpatient survey found that 34%

of participants stated they were involved in the decisions

about their care, while 40% reported they were involved to

some extentin the decision-making processand 27%

responded ‘no’to the question.In addition,CQC (2012)

CMHT survey found that54% of service users believed

their views were taken into account during their treatment,

and 43% of service users acknowledged their goals were

included in theircare plan.In contrast,participantsin

Storm & Davidson’s (2010) Norwegian qualitative study

reported their input in the decision-making process were

not taken into consideration although the service providers

showed kindness in their care.In the Irish context,De

Búrca et al.(2010) reported 64% of service users under-

stood and were satisfied with their care plan while 75% of

service users were aware oftheir treatmentreview.The

qualitative study by Elstad & Eide (2009) with 10 partici-

pants outlined the need for service users to be fully involved

in the care planning process.

Activitiesas part of the treatmentprogramme were

sometimes limited. Newell et al. (2011) quantitative study

(n = 55),found thatboredom in acute psychiatric units

plays a significant part of the inpatient experience. Partici-

pants questioned how therapeutic the activities were, while

others described an obligation to join in ward-based activ-

ities (Storm & Davidson 2010).Additionally,the CQC’s

inpatient survey (CQC 2009) identified that 24% of par-

ticipantsbelieved there were enough activitiesavailable

during weekdays;however,thesewere reduced during

D Newman et al.

178 ©2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

nates the difficulties and barriers in facilitating this process.

Twenty-one studies from a range of countries identified

issuesaround relationshipsbetween serviceusers and

service providers (United Kingdom n = 12,Ireland n = 6,

United States n = 1, and Norway n = 2). Of the 21 studies,

8 were quantitative, 6 qualitative, 5 mixed methods and 2

were literature reviews.

Commonly,studiesreported on the importanceof

building relationshipsbetween service usersand service

providers in order to meet service users’ needs

and expectations (Arbuckle et al. 2012 n = 24, Catty et al.

2012 n = 93, Gale et al. 2012 n = 12, National

Collaborating Centre for MentalHealth 2012).Hopkins

et al. (2009),in their review of 10 studies,found that

therapeutic relationships were notalways evidentwithin

mental health settings. Being valued and connected to staff

and peerswas an importantcomponentof the service

users treatmentprogramme(Hopkins et al. 2009). In

addition,Arbuckle et al.(2012)and Catty et al.(2012)

found that the relationship between a service user and a

key worker was centralto service users’connection with

their CMHT.

Service users expressed difficulties in building relation-

ships with service providers,and this can be limiting to

their participation in theircare. The difficultiesranged

from unsupported attitudes ofservice providers to inad-

equatecommunication abouttheir treatment(National

Service User Executive 2009,2010,2011,2012).Within

the inpatient settings,relationships between service users

and service providers were driven by power and lack of