Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project duration based on earned value management

VerifiedAdded on 2023/02/01

|9

|10209

|66

AI Summary

This article evaluates the accuracy and timeliness of three deterministic techniques for forecasting project duration based on earned value management. The results indicate that all three techniques are relevant and have the potential to improve project forecasting.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting

approaches for project duration based on earned

value management

Jordy Batseliera, Mario Vanhouckea, b, c,⁎

a Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

b Technology and Operations Management Area, Vlerick Business School, Reep 1, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

c Department of Management Science and Innovation, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingd

Received 15 January 2015; received in revised form 8 April 2015; accepted 14 April 2015

Abstract

In recent years, a variety of novel approaches for fulfilling the important management task of accurately forecasting pro

proposed, with many of them based on the earned value management (EVM) methodology. However, these state-of-the-a

not been adequately tested on a large database, nor has their validity been empirically proven. Therefore, we evaluate the

of three promising deterministic techniques and their mutualcombinations on a real-life projectdatabase.More specifically,two techniques

respectively integrate rework and activity sensitivity in EVM time forecasting as extensions,while a third innovatively calculates schedule

performance from time-based metrics and is appropriately called earned duration management or EDM(t). The results indi

considered techniques are relevant. More concretely, the two EVM extensions exhibit accuracy-enhancing power for differe

EDM(t) performs very similar to the best EVM methods and shows potential to improve them.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Project management; Time forecasting;Earned value management; Earned duration management; Rework; Sensitivity measures;Empiricaldatabase;

Project control

1. Introduction

Being ableto accurately predictthe final duration of

a projectis essentialto good projectmanagement.The

widely-used project control technique of earned value manage-

ment(EVM) providesa basisfor obtainingsuch project

durationforecasts.A presentationof the basicand more

thoroughgoing aspects of the EVM methodology can be found

in several works (Anbari, 2003; Fleming and Koppelman, 2010;

PMI, 2008;Vanhoucke,2010a,2014).The traditionalEVM

time1 forecasting approaches — the planned value metho

(PVM) by Anbari (2003),the earneddurationmethod

(EDM) by Jacob and Kane (2004) and the earned schedule

method (ESM)by Lipke (2003)— have recently been

evaluated by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b) based on

real-life project databaseconstructedby Batselierand

Vanhoucke (2015a).The said empiricalresearch supported

the findingsof the simulation study ofVanhouckeand

Vandevoorde (2007)by also indicating ESM as the most

accurate method.

⁎ Corresponding author at: Faculty of Economics and Business Administration,

Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium. Tel.: + 32 9 264 35

69.

E-mail addresses: jordy.batselier@ugent.be (J. Batselier),

mario.vanhoucke@ugent.be (M. Vanhoucke).

1 Following earlierworks related to this paper(Batselierand Vanhoucke,

2015b;Elshaer,2013;Khamooshiand Golafshani,2014;Vanhoucke and

Vandevoorde, 2007, etc.), the terms “time” and “duration” are intercha

when used in the contextof EVM forecasting(apartfrom linguistic

preferences).

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

0263-7863/00/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx – xxx

JPMA-01764; No of Pages 9

approaches for project duration based on earned

value management

Jordy Batseliera, Mario Vanhouckea, b, c,⁎

a Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

b Technology and Operations Management Area, Vlerick Business School, Reep 1, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

c Department of Management Science and Innovation, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingd

Received 15 January 2015; received in revised form 8 April 2015; accepted 14 April 2015

Abstract

In recent years, a variety of novel approaches for fulfilling the important management task of accurately forecasting pro

proposed, with many of them based on the earned value management (EVM) methodology. However, these state-of-the-a

not been adequately tested on a large database, nor has their validity been empirically proven. Therefore, we evaluate the

of three promising deterministic techniques and their mutualcombinations on a real-life projectdatabase.More specifically,two techniques

respectively integrate rework and activity sensitivity in EVM time forecasting as extensions,while a third innovatively calculates schedule

performance from time-based metrics and is appropriately called earned duration management or EDM(t). The results indi

considered techniques are relevant. More concretely, the two EVM extensions exhibit accuracy-enhancing power for differe

EDM(t) performs very similar to the best EVM methods and shows potential to improve them.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Project management; Time forecasting;Earned value management; Earned duration management; Rework; Sensitivity measures;Empiricaldatabase;

Project control

1. Introduction

Being ableto accurately predictthe final duration of

a projectis essentialto good projectmanagement.The

widely-used project control technique of earned value manage-

ment(EVM) providesa basisfor obtainingsuch project

durationforecasts.A presentationof the basicand more

thoroughgoing aspects of the EVM methodology can be found

in several works (Anbari, 2003; Fleming and Koppelman, 2010;

PMI, 2008;Vanhoucke,2010a,2014).The traditionalEVM

time1 forecasting approaches — the planned value metho

(PVM) by Anbari (2003),the earneddurationmethod

(EDM) by Jacob and Kane (2004) and the earned schedule

method (ESM)by Lipke (2003)— have recently been

evaluated by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b) based on

real-life project databaseconstructedby Batselierand

Vanhoucke (2015a).The said empiricalresearch supported

the findingsof the simulation study ofVanhouckeand

Vandevoorde (2007)by also indicating ESM as the most

accurate method.

⁎ Corresponding author at: Faculty of Economics and Business Administration,

Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium. Tel.: + 32 9 264 35

69.

E-mail addresses: jordy.batselier@ugent.be (J. Batselier),

mario.vanhoucke@ugent.be (M. Vanhoucke).

1 Following earlierworks related to this paper(Batselierand Vanhoucke,

2015b;Elshaer,2013;Khamooshiand Golafshani,2014;Vanhoucke and

Vandevoorde, 2007, etc.), the terms “time” and “duration” are intercha

when used in the contextof EVM forecasting(apartfrom linguistic

preferences).

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

0263-7863/00/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx – xxx

JPMA-01764; No of Pages 9

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

However,a variety of novelEVM-based time forecasting

approaches has been developed in the lastfive years.These

state-of-the-arttechniques can be subdivided into two major

categories,namely deterministic and probabilistic approaches

(Barraza etal., 2004).Deterministic approaches — like the

three traditionalEVM time forecasting methods — yield a

point estimateof the eventualprojectduration,whereas

probabilistic techniquesprovide confidence intervalsand/or

distributions of possible durations.The latter techniques can,

for example,make use of stochastic S-curves,which produce

upper and lower bounds for the range of acceptable outcomes

based on the uncertainty aboutthe predictions (Barraza etal.,

2004).Moreover,an extendingprobabilisticapproachis

provided by thefuzzy methodology,which can overcome

vagueness of data by introducing linguistic terms thatcan be

translated into fuzzy numbers through a membership function

(Naeniet al., 2011).An extensive overview ofthe existing

literature on both deterministic and probabilistic2 approaches is

given by Willemsand Vanhoucke(undersubmission).The

said paper also provides a summary of other recently developed

project forecasting methods, like those based on neural networks

(e.g.Pewdum etal.,2009;Rujirayanyong,2009)and support

vectormachines(e.g. Cheng et al., 2010; Wautersand

Vanhoucke,2014).Although these methods have been proven

useful for making project forecasts, an extensive survey is beyond

the scope of this paper,as the current focus is on deterministic

EVM-based forecasting approaches forprojectduration.More

specifically, three recent and promising techniques are considered.

The logical basic principles on which they build are as follows:

• Lipke (2011) integrates the effectof rework in ESM time

forecasting.

• Elshaer (2013) integrates activity sensitivity information in

ESM time forecasting.

• Khamooshiand Golafshani(2014)introduce earned dura-

tion management or EDM(t)3, where schedule performance

is calculated from metrics expressed in time units (and not in

cost units).

Theselogical basic principlesin fact demonstratethe

relevance ofintroducing the three selected methods.A more

concrete presentation ofthe three techniquesis provided in

Section 2. Moreover, the last two papers in the list above are also

included in the overview of Willems and Vanhoucke (2015), of

course under the category of deterministic approaches.

In the respective papers, all three of the methods are said to

have the potentialto improve the accuracy of the traditional

EVM time forecasting methods. Nevertheless, these assertions

have notyetbeen adequately tested on a large database,nor

has the validity of the considered techniques been empirica

proven.More concretely,Lipke (2011)and Khamooshiand

Golafshani(2014)apply theirtechnique on justone real-life

project, whereas Elshaer (2013) only considers projects gen

by the RanGen project network generator (Demeulemeeste

2003;Vanhouckeet al., 2008)thatwerealready used in

many earlierprojectmanagementstudies(Vandevoorde and

Vanhoucke,2006; Vanhoucke,2010a,2010b,2011,2012;

Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde, 2007).

Moreover, it is not known which one of the three conside

methods — or which combination of the methods — would

the bestresults,overalland in differentstages ofthe project.

Therefore,the goalof this paper is to compare the forecasting

accuracy and timelinessof the three noveltime forecasting

techniques and allof theirmutualcombinations based on the

real-life project data of Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015a). A

recommendations can be made concerning which method

combination of methods — best to use in a certain situation

which future research actionsto take to furtherimprove the

methods' utility.Furthermore,the proposed combination of the

three novel techniques for time forecasting is innovative in

and can therefore also be seen as a contribution of this pap

The remainderof the paperis organized asfollows.In

Section 2, the three considered state-of-the-art time foreca

methods are presented.Section 3 then proposes the methodol-

ogy for evaluating the accuracy and timeliness of these me

on real-lifeprojectdata.Subsequently,the resultsof this

evaluation arepresented and discussed in Section 4.And

finally, in Section 5, conclusions are drawn and suggestions

future research actions are made.

2. Presentation of the three state-of-the-art time forecastin

methods

In this section,the threeconsidered state-of-the-arttime

forecasting methods (Elshaer, 2013; Khamooshi and Golafs

2014;Lipke,2011)are presented in chronologicalorder.The

concerning subsections are assigned a name which reflects

basic principle of the respective method. We restrict oursel

brief explanation ofthe three methods.Although the provided

explanation should suffice forunderstanding the techniques,if

desired,the readercan find more elaborate discussions on the

different methodologies in the originating papers. However

we can present the three novel time forecasting methods —

are all based on EVM — a more general discussion needs to

conducted.

Since earlier studies on EVM forecasting accuracy (Batse

and Vanhoucke,2015b;Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde,2007)

have proven the dominance of ESM over PVM and EDM, the

former method is used as a basis (and benchmark) for all th

novel deterministic approaches.The generic ESM formula for

obtaining the projectduration forecastor estimated time at

completion EAC(t) is given by:

EAC tð Þ ¼ AT þ

PD−ES

P F : ð1Þ

2 In Willems and Vanhoucke (2015), the probabilistic approaches are further

subdivided into stochastic and fuzzy techniques.

3 Khamooshiand Golafshani(2014) in factuse the abbreviation EDM for

earneddurationmanagement.However,this abbreviationwas already

introduced for the earned duration method of Jacob and Kane (2004). In order

to avoid confusion,we therefore referto earned duration managementby

EDM(t). Furthermore, the suffix (t) also clearly indicates that the technique is

based on time metrics instead of cost metrics.

2 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

approaches has been developed in the lastfive years.These

state-of-the-arttechniques can be subdivided into two major

categories,namely deterministic and probabilistic approaches

(Barraza etal., 2004).Deterministic approaches — like the

three traditionalEVM time forecasting methods — yield a

point estimateof the eventualprojectduration,whereas

probabilistic techniquesprovide confidence intervalsand/or

distributions of possible durations.The latter techniques can,

for example,make use of stochastic S-curves,which produce

upper and lower bounds for the range of acceptable outcomes

based on the uncertainty aboutthe predictions (Barraza etal.,

2004).Moreover,an extendingprobabilisticapproachis

provided by thefuzzy methodology,which can overcome

vagueness of data by introducing linguistic terms thatcan be

translated into fuzzy numbers through a membership function

(Naeniet al., 2011).An extensive overview ofthe existing

literature on both deterministic and probabilistic2 approaches is

given by Willemsand Vanhoucke(undersubmission).The

said paper also provides a summary of other recently developed

project forecasting methods, like those based on neural networks

(e.g.Pewdum etal.,2009;Rujirayanyong,2009)and support

vectormachines(e.g. Cheng et al., 2010; Wautersand

Vanhoucke,2014).Although these methods have been proven

useful for making project forecasts, an extensive survey is beyond

the scope of this paper,as the current focus is on deterministic

EVM-based forecasting approaches forprojectduration.More

specifically, three recent and promising techniques are considered.

The logical basic principles on which they build are as follows:

• Lipke (2011) integrates the effectof rework in ESM time

forecasting.

• Elshaer (2013) integrates activity sensitivity information in

ESM time forecasting.

• Khamooshiand Golafshani(2014)introduce earned dura-

tion management or EDM(t)3, where schedule performance

is calculated from metrics expressed in time units (and not in

cost units).

Theselogical basic principlesin fact demonstratethe

relevance ofintroducing the three selected methods.A more

concrete presentation ofthe three techniquesis provided in

Section 2. Moreover, the last two papers in the list above are also

included in the overview of Willems and Vanhoucke (2015), of

course under the category of deterministic approaches.

In the respective papers, all three of the methods are said to

have the potentialto improve the accuracy of the traditional

EVM time forecasting methods. Nevertheless, these assertions

have notyetbeen adequately tested on a large database,nor

has the validity of the considered techniques been empirica

proven.More concretely,Lipke (2011)and Khamooshiand

Golafshani(2014)apply theirtechnique on justone real-life

project, whereas Elshaer (2013) only considers projects gen

by the RanGen project network generator (Demeulemeeste

2003;Vanhouckeet al., 2008)thatwerealready used in

many earlierprojectmanagementstudies(Vandevoorde and

Vanhoucke,2006; Vanhoucke,2010a,2010b,2011,2012;

Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde, 2007).

Moreover, it is not known which one of the three conside

methods — or which combination of the methods — would

the bestresults,overalland in differentstages ofthe project.

Therefore,the goalof this paper is to compare the forecasting

accuracy and timelinessof the three noveltime forecasting

techniques and allof theirmutualcombinations based on the

real-life project data of Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015a). A

recommendations can be made concerning which method

combination of methods — best to use in a certain situation

which future research actionsto take to furtherimprove the

methods' utility.Furthermore,the proposed combination of the

three novel techniques for time forecasting is innovative in

and can therefore also be seen as a contribution of this pap

The remainderof the paperis organized asfollows.In

Section 2, the three considered state-of-the-art time foreca

methods are presented.Section 3 then proposes the methodol-

ogy for evaluating the accuracy and timeliness of these me

on real-lifeprojectdata.Subsequently,the resultsof this

evaluation arepresented and discussed in Section 4.And

finally, in Section 5, conclusions are drawn and suggestions

future research actions are made.

2. Presentation of the three state-of-the-art time forecastin

methods

In this section,the threeconsidered state-of-the-arttime

forecasting methods (Elshaer, 2013; Khamooshi and Golafs

2014;Lipke,2011)are presented in chronologicalorder.The

concerning subsections are assigned a name which reflects

basic principle of the respective method. We restrict oursel

brief explanation ofthe three methods.Although the provided

explanation should suffice forunderstanding the techniques,if

desired,the readercan find more elaborate discussions on the

different methodologies in the originating papers. However

we can present the three novel time forecasting methods —

are all based on EVM — a more general discussion needs to

conducted.

Since earlier studies on EVM forecasting accuracy (Batse

and Vanhoucke,2015b;Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde,2007)

have proven the dominance of ESM over PVM and EDM, the

former method is used as a basis (and benchmark) for all th

novel deterministic approaches.The generic ESM formula for

obtaining the projectduration forecastor estimated time at

completion EAC(t) is given by:

EAC tð Þ ¼ AT þ

PD−ES

P F : ð1Þ

2 In Willems and Vanhoucke (2015), the probabilistic approaches are further

subdivided into stochastic and fuzzy techniques.

3 Khamooshiand Golafshani(2014) in factuse the abbreviation EDM for

earneddurationmanagement.However,this abbreviationwas already

introduced for the earned duration method of Jacob and Kane (2004). In order

to avoid confusion,we therefore referto earned duration managementby

EDM(t). Furthermore, the suffix (t) also clearly indicates that the technique is

based on time metrics instead of cost metrics.

2 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

AT represents the actual time (at the current tracking period),

PD the planned duration of the project according to the baseline

schedule, and ES the earned schedule (i.e. the time at which the

currentprojectprogressshould actually have been achieved

according to the plan).Furthermore,PF expresses the perfor-

mance factorthatis assumed.Vandevoorde and Vanhoucke

(2006) and Vanhoucke (2010a) provide an extensive overview of

the performance factorsthatcan be applied forEVM time

forecasting. Nevertheless, the most commonly used performance

factors — which will also be considered in this study — are 1

(i.e.it is assumed thatfuture schedule performance willbe as

planned) and the ES-based schedule performance index SPI(t)

(i.e. it is assumed that future schedule performance will be equal

to the current schedule performance; SPI(t) = ES/AT). Whereas

the simulation study ofVanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007)

indicated SPI(t)as the bestperforming performancefactor,

Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b) showed thatsetting PF = 1

produces the mostaccurate time forecasts forthe considered

real-life project data.

Buildingon this basis,a brief discussionof the three

deterministic state-of-the-artmethods for projectduration fore-

casting can now be provided.

2.1. Integrating rework in ESM (Lipke, 2011)

While Lipke etal. (2009)applied statisticalmethodsto

ESM, Lipke (2011)extendsthe techniqueby taking into

account schedule adherence,which can lead to the occurrence

of rework (Lipke, 2004; Vanhoucke, 2010a). More specifically,

the earned value EV is adjusted to the effective earned value

EV(e) through the formula EV(e) = EV − R where R represents

the rework that can be calculated as:

R ¼ 1−PCn e−m 1−PCð Þ 1−pð Þ EV : ð2Þ

PC is the percentage complete of the project(= EV/BAC,

with BAC the budgetat completion) and P is the so-called

p-factor(Lipke, 2004), which expressesthe degreeof

schedule adherence (i.e.P = 1 indicatesperfectschedule

adherence, P = 0 signifies no schedule adherence at all). The

assessmentof the influence of schedule adherence (i.e.the

p-factor) on EVM time forecasting accuracy has already been

the subjectof a few simulation studies (Vanhoucke,2010a,

2013).

The exponents n and m in Eq.(2) are traditionally setto

1 and 0.5,respectively,yielding a nearly lineardecrease of

the rework fraction (i.e.the percentage ofthe work not

performed according to schedule that has to be redone) as the

percentage complete increases (Lipke,2011).The adapted

EV(e) can then be used to calculate ES(e),and through that,

SPI(t)(e) = ES(e)/AT.The targeted projectduration forecast

can then be obtained by substituting ES by ES(e) and using

SPI(t)(e) as a performance factor in the generic ESM formula

(Eq. (1)). Of course,1 can also be used as a performance

factor here.

2.2. Integrating activity sensitivity in ESM (Elshaer, 2013)

Elaborating on the idea of integrating schedule risk ana

(SRA) and EVM as proposed by Vanhoucke (2010a); Vanh

(2010b);Vanhoucke (2011);Vanhoucke (2012); Elshaer (2013)

suggeststo take into accountactivity sensitivity information

(i.e. SRA) for the calculation ofprojectduration forecasts

(i.e. EVM). More specifically, activity-based sensitivity me

are used as weighing parameters for the PV and EV of the

The rationale is that this would lead to a more accurate s

performance by removing or decreasing the negative effe

warning signals caused by non-criticalactivities.The criticality

index CI appeared to yield the best results as a weighing

(Elshaer,2013).Therefore,this activity sensitivity measure —

which can be calculated by performing Monte Carlo simu

based on the activity duration distribution profiles (i.e. tri

distributions which can be either symmetrical or skewed

or to the right, depending on the characteristics of the ac

will be applied here.Moreover,since weighing PV and EV

results in an adjusted ES and SPI(t), the EAC(t) will also c

(see Eq. (1)), both with PF = 1 and PF = SPI(t).

2.3.Calculating schedule performance in time units: EDM

(Khamooshi and Golafshani, 2014)

Khamooshi and Golafshani (2014) argue that time fore

ing with ESM could still yield misleading resultsas the

technique keeps using costs as a proxy to measure sched

performance(i.e. ES is calculated based on EV and PV

values,which are both expressed in costunits).Therefore,

they developed the technique of earned duration manage

or EDM(t),in which schedule and cost performance measu

are completely decoupled.More specifically,the ES metric is

replaced by earned duration ED(t),which is calculated as the

projection of the total earned duration TED (i.e. the sum

earned durations of all the in-progress and completed ac

at AT4) on the total planned duration TPD (i.e.the sum of the

planned durations of all the planned activities at AT acco

to the baseline schedule) instead of the projection of EV

which yields ES. Besides the fact that the calculation of E

based on metrics that are expressed in time units (i.e. TE

TPD) instead of costunits (i.e.EV and PV),it is completely

similar to the calculation of ES. To obtain time forecasts f

the EDM(t) methodology, we apply following formula5:

EAC tð Þ ¼PD

DPI : ð3Þ

This formula is strongly parallelto thatof the traditional

PVM (i.e. PVM-SPI: EAC(t) = PD/SPI),butwith the perfor-

mance factor changed to the duration performance index

4 The earned duration of an in-progress (or completed) activity at AT is

planned baseline duration of thatactivity multiplied by the actualpercentage

complete (or physical progress) of that activity at AT.

5 Khamooshi and Golafshani (2014) actually use the notation EDAC for

estimated duration (or time) atcompletion,which is substantially exactly the

same as EAC(t).

3J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

PD the planned duration of the project according to the baseline

schedule, and ES the earned schedule (i.e. the time at which the

currentprojectprogressshould actually have been achieved

according to the plan).Furthermore,PF expresses the perfor-

mance factorthatis assumed.Vandevoorde and Vanhoucke

(2006) and Vanhoucke (2010a) provide an extensive overview of

the performance factorsthatcan be applied forEVM time

forecasting. Nevertheless, the most commonly used performance

factors — which will also be considered in this study — are 1

(i.e.it is assumed thatfuture schedule performance willbe as

planned) and the ES-based schedule performance index SPI(t)

(i.e. it is assumed that future schedule performance will be equal

to the current schedule performance; SPI(t) = ES/AT). Whereas

the simulation study ofVanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007)

indicated SPI(t)as the bestperforming performancefactor,

Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b) showed thatsetting PF = 1

produces the mostaccurate time forecasts forthe considered

real-life project data.

Buildingon this basis,a brief discussionof the three

deterministic state-of-the-artmethods for projectduration fore-

casting can now be provided.

2.1. Integrating rework in ESM (Lipke, 2011)

While Lipke etal. (2009)applied statisticalmethodsto

ESM, Lipke (2011)extendsthe techniqueby taking into

account schedule adherence,which can lead to the occurrence

of rework (Lipke, 2004; Vanhoucke, 2010a). More specifically,

the earned value EV is adjusted to the effective earned value

EV(e) through the formula EV(e) = EV − R where R represents

the rework that can be calculated as:

R ¼ 1−PCn e−m 1−PCð Þ 1−pð Þ EV : ð2Þ

PC is the percentage complete of the project(= EV/BAC,

with BAC the budgetat completion) and P is the so-called

p-factor(Lipke, 2004), which expressesthe degreeof

schedule adherence (i.e.P = 1 indicatesperfectschedule

adherence, P = 0 signifies no schedule adherence at all). The

assessmentof the influence of schedule adherence (i.e.the

p-factor) on EVM time forecasting accuracy has already been

the subjectof a few simulation studies (Vanhoucke,2010a,

2013).

The exponents n and m in Eq.(2) are traditionally setto

1 and 0.5,respectively,yielding a nearly lineardecrease of

the rework fraction (i.e.the percentage ofthe work not

performed according to schedule that has to be redone) as the

percentage complete increases (Lipke,2011).The adapted

EV(e) can then be used to calculate ES(e),and through that,

SPI(t)(e) = ES(e)/AT.The targeted projectduration forecast

can then be obtained by substituting ES by ES(e) and using

SPI(t)(e) as a performance factor in the generic ESM formula

(Eq. (1)). Of course,1 can also be used as a performance

factor here.

2.2. Integrating activity sensitivity in ESM (Elshaer, 2013)

Elaborating on the idea of integrating schedule risk ana

(SRA) and EVM as proposed by Vanhoucke (2010a); Vanh

(2010b);Vanhoucke (2011);Vanhoucke (2012); Elshaer (2013)

suggeststo take into accountactivity sensitivity information

(i.e. SRA) for the calculation ofprojectduration forecasts

(i.e. EVM). More specifically, activity-based sensitivity me

are used as weighing parameters for the PV and EV of the

The rationale is that this would lead to a more accurate s

performance by removing or decreasing the negative effe

warning signals caused by non-criticalactivities.The criticality

index CI appeared to yield the best results as a weighing

(Elshaer,2013).Therefore,this activity sensitivity measure —

which can be calculated by performing Monte Carlo simu

based on the activity duration distribution profiles (i.e. tri

distributions which can be either symmetrical or skewed

or to the right, depending on the characteristics of the ac

will be applied here.Moreover,since weighing PV and EV

results in an adjusted ES and SPI(t), the EAC(t) will also c

(see Eq. (1)), both with PF = 1 and PF = SPI(t).

2.3.Calculating schedule performance in time units: EDM

(Khamooshi and Golafshani, 2014)

Khamooshi and Golafshani (2014) argue that time fore

ing with ESM could still yield misleading resultsas the

technique keeps using costs as a proxy to measure sched

performance(i.e. ES is calculated based on EV and PV

values,which are both expressed in costunits).Therefore,

they developed the technique of earned duration manage

or EDM(t),in which schedule and cost performance measu

are completely decoupled.More specifically,the ES metric is

replaced by earned duration ED(t),which is calculated as the

projection of the total earned duration TED (i.e. the sum

earned durations of all the in-progress and completed ac

at AT4) on the total planned duration TPD (i.e.the sum of the

planned durations of all the planned activities at AT acco

to the baseline schedule) instead of the projection of EV

which yields ES. Besides the fact that the calculation of E

based on metrics that are expressed in time units (i.e. TE

TPD) instead of costunits (i.e.EV and PV),it is completely

similar to the calculation of ES. To obtain time forecasts f

the EDM(t) methodology, we apply following formula5:

EAC tð Þ ¼PD

DPI : ð3Þ

This formula is strongly parallelto thatof the traditional

PVM (i.e. PVM-SPI: EAC(t) = PD/SPI),butwith the perfor-

mance factor changed to the duration performance index

4 The earned duration of an in-progress (or completed) activity at AT is

planned baseline duration of thatactivity multiplied by the actualpercentage

complete (or physical progress) of that activity at AT.

5 Khamooshi and Golafshani (2014) actually use the notation EDAC for

estimated duration (or time) atcompletion,which is substantially exactly the

same as EAC(t).

3J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

which can be calculated very similarto SPI(t)as ED(t)/AT.

Obviously, using a PF = 1 would not be useful when applying

the EDM(t) formulasas proposedby Khamooshiand

Golafshani(2014),since this would simply yield the planned

duration as a forecast (see Eq. (3)).

3. Methodology

Recall that the goal of this paper is to compare the forecasting

accuracy and timeliness ofthe three noveldeterministic time

forecasting techniques and all of their mutual combinations based

on real-life project data. The real-life projects that are used for this

study originate from the database of Batselier and Vanhoucke

(2015a)and are briefly presented in Section 3.1.Section 3.2

then describes the applied forecasting accuracy and timeliness

evaluation approach. Finally, the concrete approach for combin-

ing the three considered state-of-the-art time forecasting methods

is presented in Section 3.3.

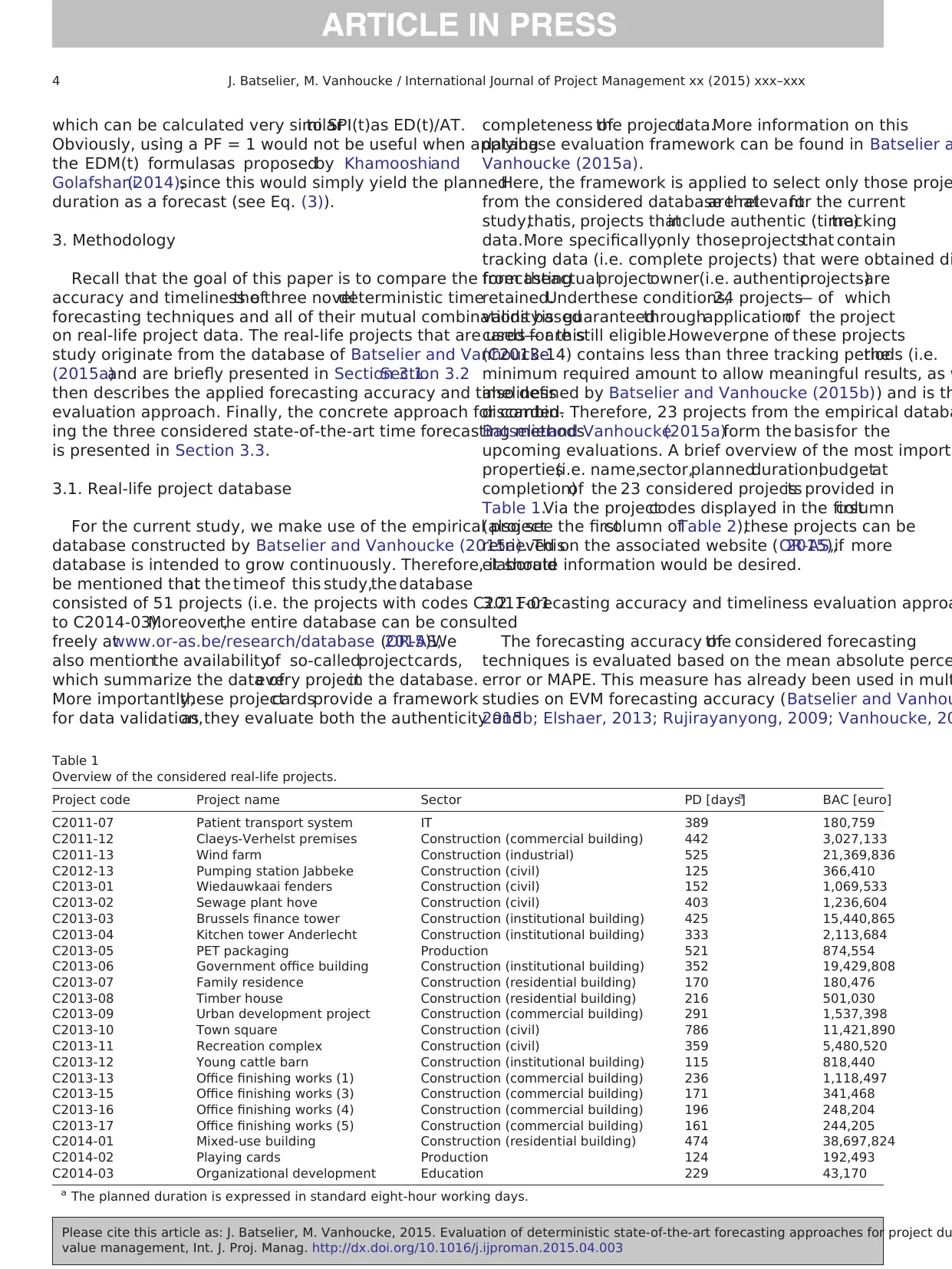

3.1. Real-life project database

For the current study, we make use of the empirical project

database constructed by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015a). This

database is intended to grow continuously. Therefore, it should

be mentioned thatat the timeof this study,the database

consisted of 51 projects (i.e. the projects with codes C2011-01

to C2014-03).Moreover,the entire database can be consulted

freely atwww.or-as.be/research/database (OR-AS,2015).We

also mentionthe availabilityof so-calledprojectcards,

which summarize the data ofevery projectin the database.

More importantly,these projectcardsprovide a framework

for data validation,as they evaluate both the authenticity and

completeness ofthe projectdata.More information on this

database evaluation framework can be found in Batselier a

Vanhoucke (2015a).

Here, the framework is applied to select only those proje

from the considered database thatare relevantfor the current

study,thatis, projects thatinclude authentic (time)tracking

data.More specifically,only thoseprojectsthat contain

tracking data (i.e. complete projects) that were obtained di

from theactualprojectowner(i.e. authenticprojects)are

retained.Underthese conditions,24 projects— of which

validityis guaranteedthroughapplicationof the project

cards— are still eligible.However,one of these projects

(C2013-14) contains less than three tracking periods (i.e.the

minimum required amount to allow meaningful results, as w

also defined by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b)) and is th

discarded. Therefore, 23 projects from the empirical databa

Batselierand Vanhoucke(2015a)form the basisfor the

upcoming evaluations. A brief overview of the most importa

properties(i.e. name,sector,plannedduration,budgetat

completion)of the 23 considered projectsis provided in

Table 1.Via the projectcodes displayed in the firstcolumn

(also see the firstcolumn ofTable 2),these projects can be

retrieved on the associated website (OR-AS,2015),if more

elaborate information would be desired.

3.2. Forecasting accuracy and timeliness evaluation approa

The forecasting accuracy ofthe considered forecasting

techniques is evaluated based on the mean absolute perce

error or MAPE. This measure has already been used in mult

studies on EVM forecasting accuracy (Batselier and Vanhou

2015b; Elshaer, 2013; Rujirayanyong, 2009; Vanhoucke, 20

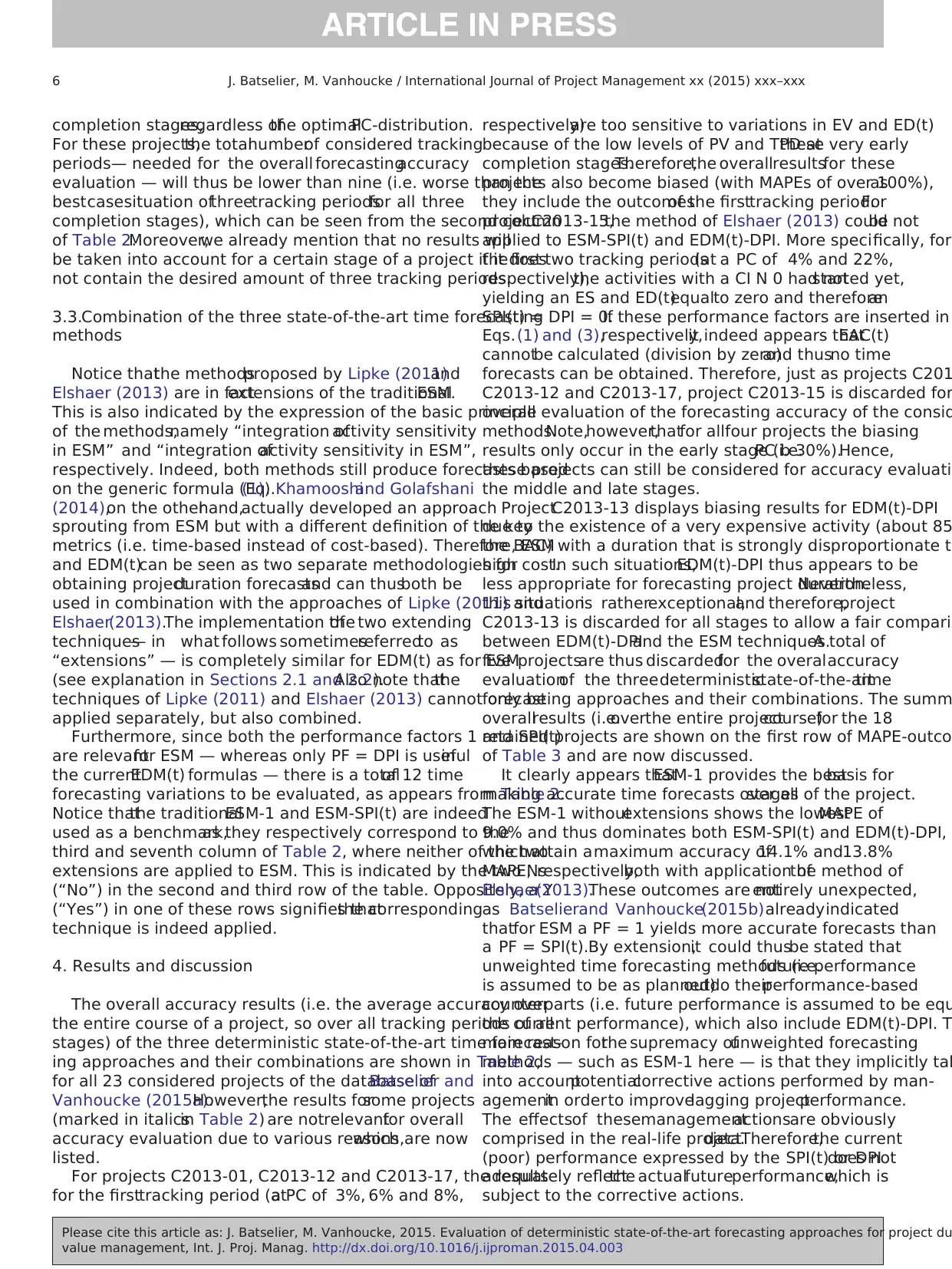

Table 1

Overview of the considered real-life projects.

Project code Project name Sector PD [days]a BAC [euro]

C2011-07 Patient transport system IT 389 180,759

C2011-12 Claeys-Verhelst premises Construction (commercial building) 442 3,027,133

C2011-13 Wind farm Construction (industrial) 525 21,369,836

C2012-13 Pumping station Jabbeke Construction (civil) 125 366,410

C2013-01 Wiedauwkaai fenders Construction (civil) 152 1,069,533

C2013-02 Sewage plant hove Construction (civil) 403 1,236,604

C2013-03 Brussels finance tower Construction (institutional building) 425 15,440,865

C2013-04 Kitchen tower Anderlecht Construction (institutional building) 333 2,113,684

C2013-05 PET packaging Production 521 874,554

C2013-06 Government office building Construction (institutional building) 352 19,429,808

C2013-07 Family residence Construction (residential building) 170 180,476

C2013-08 Timber house Construction (residential building) 216 501,030

C2013-09 Urban development project Construction (commercial building) 291 1,537,398

C2013-10 Town square Construction (civil) 786 11,421,890

C2013-11 Recreation complex Construction (civil) 359 5,480,520

C2013-12 Young cattle barn Construction (institutional building) 115 818,440

C2013-13 Office finishing works (1) Construction (commercial building) 236 1,118,497

C2013-15 Office finishing works (3) Construction (commercial building) 171 341,468

C2013-16 Office finishing works (4) Construction (commercial building) 196 248,204

C2013-17 Office finishing works (5) Construction (commercial building) 161 244,205

C2014-01 Mixed-use building Construction (residential building) 474 38,697,824

C2014-02 Playing cards Production 124 192,493

C2014-03 Organizational development Education 229 43,170

a The planned duration is expressed in standard eight-hour working days.

4 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

Obviously, using a PF = 1 would not be useful when applying

the EDM(t) formulasas proposedby Khamooshiand

Golafshani(2014),since this would simply yield the planned

duration as a forecast (see Eq. (3)).

3. Methodology

Recall that the goal of this paper is to compare the forecasting

accuracy and timeliness ofthe three noveldeterministic time

forecasting techniques and all of their mutual combinations based

on real-life project data. The real-life projects that are used for this

study originate from the database of Batselier and Vanhoucke

(2015a)and are briefly presented in Section 3.1.Section 3.2

then describes the applied forecasting accuracy and timeliness

evaluation approach. Finally, the concrete approach for combin-

ing the three considered state-of-the-art time forecasting methods

is presented in Section 3.3.

3.1. Real-life project database

For the current study, we make use of the empirical project

database constructed by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015a). This

database is intended to grow continuously. Therefore, it should

be mentioned thatat the timeof this study,the database

consisted of 51 projects (i.e. the projects with codes C2011-01

to C2014-03).Moreover,the entire database can be consulted

freely atwww.or-as.be/research/database (OR-AS,2015).We

also mentionthe availabilityof so-calledprojectcards,

which summarize the data ofevery projectin the database.

More importantly,these projectcardsprovide a framework

for data validation,as they evaluate both the authenticity and

completeness ofthe projectdata.More information on this

database evaluation framework can be found in Batselier a

Vanhoucke (2015a).

Here, the framework is applied to select only those proje

from the considered database thatare relevantfor the current

study,thatis, projects thatinclude authentic (time)tracking

data.More specifically,only thoseprojectsthat contain

tracking data (i.e. complete projects) that were obtained di

from theactualprojectowner(i.e. authenticprojects)are

retained.Underthese conditions,24 projects— of which

validityis guaranteedthroughapplicationof the project

cards— are still eligible.However,one of these projects

(C2013-14) contains less than three tracking periods (i.e.the

minimum required amount to allow meaningful results, as w

also defined by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b)) and is th

discarded. Therefore, 23 projects from the empirical databa

Batselierand Vanhoucke(2015a)form the basisfor the

upcoming evaluations. A brief overview of the most importa

properties(i.e. name,sector,plannedduration,budgetat

completion)of the 23 considered projectsis provided in

Table 1.Via the projectcodes displayed in the firstcolumn

(also see the firstcolumn ofTable 2),these projects can be

retrieved on the associated website (OR-AS,2015),if more

elaborate information would be desired.

3.2. Forecasting accuracy and timeliness evaluation approa

The forecasting accuracy ofthe considered forecasting

techniques is evaluated based on the mean absolute perce

error or MAPE. This measure has already been used in mult

studies on EVM forecasting accuracy (Batselier and Vanhou

2015b; Elshaer, 2013; Rujirayanyong, 2009; Vanhoucke, 20

Table 1

Overview of the considered real-life projects.

Project code Project name Sector PD [days]a BAC [euro]

C2011-07 Patient transport system IT 389 180,759

C2011-12 Claeys-Verhelst premises Construction (commercial building) 442 3,027,133

C2011-13 Wind farm Construction (industrial) 525 21,369,836

C2012-13 Pumping station Jabbeke Construction (civil) 125 366,410

C2013-01 Wiedauwkaai fenders Construction (civil) 152 1,069,533

C2013-02 Sewage plant hove Construction (civil) 403 1,236,604

C2013-03 Brussels finance tower Construction (institutional building) 425 15,440,865

C2013-04 Kitchen tower Anderlecht Construction (institutional building) 333 2,113,684

C2013-05 PET packaging Production 521 874,554

C2013-06 Government office building Construction (institutional building) 352 19,429,808

C2013-07 Family residence Construction (residential building) 170 180,476

C2013-08 Timber house Construction (residential building) 216 501,030

C2013-09 Urban development project Construction (commercial building) 291 1,537,398

C2013-10 Town square Construction (civil) 786 11,421,890

C2013-11 Recreation complex Construction (civil) 359 5,480,520

C2013-12 Young cattle barn Construction (institutional building) 115 818,440

C2013-13 Office finishing works (1) Construction (commercial building) 236 1,118,497

C2013-15 Office finishing works (3) Construction (commercial building) 171 341,468

C2013-16 Office finishing works (4) Construction (commercial building) 196 248,204

C2013-17 Office finishing works (5) Construction (commercial building) 161 244,205

C2014-01 Mixed-use building Construction (residential building) 474 38,697,824

C2014-02 Playing cards Production 124 192,493

C2014-03 Organizational development Education 229 43,170

a The planned duration is expressed in standard eight-hour working days.

4 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde,2007).The MAPE is calculated

according to the following formula:

MAPE ¼1

n

Xn

t¼1

A−Ft

A ð4Þ

where A is the actual final value and Ft the forecasted value at

time t. The time points t = 1,..., n represent the n tracking periods

that were selected for the considered project. More information

on the selection procedure applied forthe tracking periods is

provided in the nextparagraph.Furthermore,Eq. ((4)) can be

particularized for time forecasting by substituting A and Ft by the

actualtotalduration of the project(also referred to as the real

duration RD) and EAC(t), respectively. Logically, the lower the

MAPE for a certain forecasting method, the higher the accuracy

of that method.

Covach etal. (1981)state that,besidesoverallaccuracy

(i.e.the average accuracy over the entire course of a project),

timelinessis also an essentialcriterion forthe assessment

of forecasting methods.Therefore,we perform a stage-wise

comparison of the accuracies of the considered time forecasting

methodsbased on thetimelinessevaluation approach from

Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007). To allow this comparison,

three project completion stages are defined according to the PC:

• 0% ≤ PC b 30%: early stage

• 30% ≤ PC ≤ 70%: middle stage

• 70% b PC ≤ 100%: late stage

The above categorization corresponds to the basic sub

sion made by Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007)and was

also applied by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b).Notice that

the middle stage was assigned a PC-interval that is large

that of the other completion stages.This was done to account

for the fasterprogressnearthe middle ofa projectthatis

typically observed in many situations (Kim and Kim,2014).

By assigning a largerPC-intervalto the middle stage,we

thus increase the probability of having ample tracking pe

situated in this stage. More specifically, we aim at having

from three tracking periods for every completion stage of

project.

Moreover,we attemptto selectthe tracking periods fora

certain completion stage in such a way that their PC-valu

distributed as evenly as possible within the appropriate in

Furthermore, tracking periods with a PC close to the boun

values of the stages are avoided,in order to allow a clear and

distinctive comparison between the stages.More concretely,

for the early stage we try to select three tracking periods

PC of approximately 5%, 15% and 25%, respectively. For

middle stage this becomes 40%,50% and 60%,respectively,

and for the late stage75%, 85% and 95%,respectively.

Obviously,theseoptimalPC-distributionsare not always

readily applicable forthe projects in the employed database

Nevertheless,we always seek to approach them as wellas

possible.

Furthermore,for someof the considered projects,it is

notpossible to find three tracking periods for one (or mor

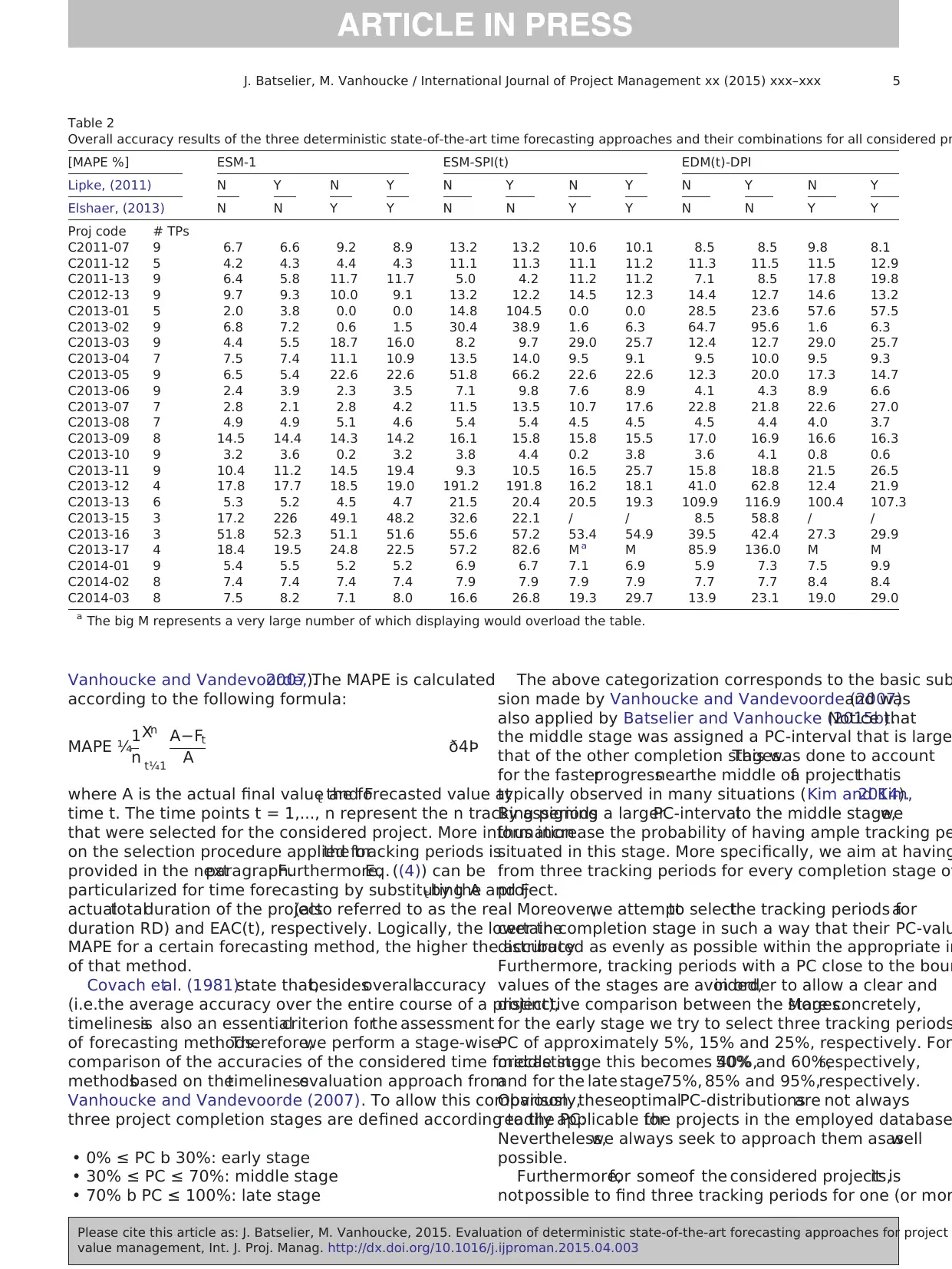

Table 2

Overall accuracy results of the three deterministic state-of-the-art time forecasting approaches and their combinations for all considered pr

[MAPE %] ESM-1 ESM-SPI(t) EDM(t)-DPI

Lipke, (2011) N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y

Elshaer, (2013) N N Y Y N N Y Y N N Y Y

Proj code # TPs

C2011-07 9 6.7 6.6 9.2 8.9 13.2 13.2 10.6 10.1 8.5 8.5 9.8 8.1

C2011-12 5 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.3 11.1 11.3 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.5 11.5 12.9

C2011-13 9 6.4 5.8 11.7 11.7 5.0 4.2 11.2 11.2 7.1 8.5 17.8 19.8

C2012-13 9 9.7 9.3 10.0 9.1 13.2 12.2 14.5 12.3 14.4 12.7 14.6 13.2

C2013-01 5 2.0 3.8 0.0 0.0 14.8 104.5 0.0 0.0 28.5 23.6 57.6 57.5

C2013-02 9 6.8 7.2 0.6 1.5 30.4 38.9 1.6 6.3 64.7 95.6 1.6 6.3

C2013-03 9 4.4 5.5 18.7 16.0 8.2 9.7 29.0 25.7 12.4 12.7 29.0 25.7

C2013-04 7 7.5 7.4 11.1 10.9 13.5 14.0 9.5 9.1 9.5 10.0 9.5 9.3

C2013-05 9 6.5 5.4 22.6 22.6 51.8 66.2 22.6 22.6 12.3 20.0 17.3 14.7

C2013-06 9 2.4 3.9 2.3 3.5 7.1 9.8 7.6 8.9 4.1 4.3 8.9 6.6

C2013-07 7 2.8 2.1 2.8 4.2 11.5 13.5 10.7 17.6 22.8 21.8 22.6 27.0

C2013-08 7 4.9 4.9 5.1 4.6 5.4 5.4 4.5 4.5 4.5 4.4 4.0 3.7

C2013-09 8 14.5 14.4 14.3 14.2 16.1 15.8 15.8 15.5 17.0 16.9 16.6 16.3

C2013-10 9 3.2 3.6 0.2 3.2 3.8 4.4 0.2 3.8 3.6 4.1 0.8 0.6

C2013-11 9 10.4 11.2 14.5 19.4 9.3 10.5 16.5 25.7 15.8 18.8 21.5 26.5

C2013-12 4 17.8 17.7 18.5 19.0 191.2 191.8 16.2 18.1 41.0 62.8 12.4 21.9

C2013-13 6 5.3 5.2 4.5 4.7 21.5 20.4 20.5 19.3 109.9 116.9 100.4 107.3

C2013-15 3 17.2 22.6 49.1 48.2 32.6 22.1 / / 8.5 58.8 / /

C2013-16 3 51.8 52.3 51.1 51.6 55.6 57.2 53.4 54.9 39.5 42.4 27.3 29.9

C2013-17 4 18.4 19.5 24.8 22.5 57.2 82.6 M a M 85.9 136.0 M M

C2014-01 9 5.4 5.5 5.2 5.2 6.9 6.7 7.1 6.9 5.9 7.3 7.5 9.9

C2014-02 8 7.4 7.4 7.4 7.4 7.9 7.9 7.9 7.9 7.7 7.7 8.4 8.4

C2014-03 8 7.5 8.2 7.1 8.0 16.6 26.8 19.3 29.7 13.9 23.1 19.0 29.0

a The big M represents a very large number of which displaying would overload the table.

5J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

according to the following formula:

MAPE ¼1

n

Xn

t¼1

A−Ft

A ð4Þ

where A is the actual final value and Ft the forecasted value at

time t. The time points t = 1,..., n represent the n tracking periods

that were selected for the considered project. More information

on the selection procedure applied forthe tracking periods is

provided in the nextparagraph.Furthermore,Eq. ((4)) can be

particularized for time forecasting by substituting A and Ft by the

actualtotalduration of the project(also referred to as the real

duration RD) and EAC(t), respectively. Logically, the lower the

MAPE for a certain forecasting method, the higher the accuracy

of that method.

Covach etal. (1981)state that,besidesoverallaccuracy

(i.e.the average accuracy over the entire course of a project),

timelinessis also an essentialcriterion forthe assessment

of forecasting methods.Therefore,we perform a stage-wise

comparison of the accuracies of the considered time forecasting

methodsbased on thetimelinessevaluation approach from

Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007). To allow this comparison,

three project completion stages are defined according to the PC:

• 0% ≤ PC b 30%: early stage

• 30% ≤ PC ≤ 70%: middle stage

• 70% b PC ≤ 100%: late stage

The above categorization corresponds to the basic sub

sion made by Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde (2007)and was

also applied by Batselier and Vanhoucke (2015b).Notice that

the middle stage was assigned a PC-interval that is large

that of the other completion stages.This was done to account

for the fasterprogressnearthe middle ofa projectthatis

typically observed in many situations (Kim and Kim,2014).

By assigning a largerPC-intervalto the middle stage,we

thus increase the probability of having ample tracking pe

situated in this stage. More specifically, we aim at having

from three tracking periods for every completion stage of

project.

Moreover,we attemptto selectthe tracking periods fora

certain completion stage in such a way that their PC-valu

distributed as evenly as possible within the appropriate in

Furthermore, tracking periods with a PC close to the boun

values of the stages are avoided,in order to allow a clear and

distinctive comparison between the stages.More concretely,

for the early stage we try to select three tracking periods

PC of approximately 5%, 15% and 25%, respectively. For

middle stage this becomes 40%,50% and 60%,respectively,

and for the late stage75%, 85% and 95%,respectively.

Obviously,theseoptimalPC-distributionsare not always

readily applicable forthe projects in the employed database

Nevertheless,we always seek to approach them as wellas

possible.

Furthermore,for someof the considered projects,it is

notpossible to find three tracking periods for one (or mor

Table 2

Overall accuracy results of the three deterministic state-of-the-art time forecasting approaches and their combinations for all considered pr

[MAPE %] ESM-1 ESM-SPI(t) EDM(t)-DPI

Lipke, (2011) N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y

Elshaer, (2013) N N Y Y N N Y Y N N Y Y

Proj code # TPs

C2011-07 9 6.7 6.6 9.2 8.9 13.2 13.2 10.6 10.1 8.5 8.5 9.8 8.1

C2011-12 5 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.3 11.1 11.3 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.5 11.5 12.9

C2011-13 9 6.4 5.8 11.7 11.7 5.0 4.2 11.2 11.2 7.1 8.5 17.8 19.8

C2012-13 9 9.7 9.3 10.0 9.1 13.2 12.2 14.5 12.3 14.4 12.7 14.6 13.2

C2013-01 5 2.0 3.8 0.0 0.0 14.8 104.5 0.0 0.0 28.5 23.6 57.6 57.5

C2013-02 9 6.8 7.2 0.6 1.5 30.4 38.9 1.6 6.3 64.7 95.6 1.6 6.3

C2013-03 9 4.4 5.5 18.7 16.0 8.2 9.7 29.0 25.7 12.4 12.7 29.0 25.7

C2013-04 7 7.5 7.4 11.1 10.9 13.5 14.0 9.5 9.1 9.5 10.0 9.5 9.3

C2013-05 9 6.5 5.4 22.6 22.6 51.8 66.2 22.6 22.6 12.3 20.0 17.3 14.7

C2013-06 9 2.4 3.9 2.3 3.5 7.1 9.8 7.6 8.9 4.1 4.3 8.9 6.6

C2013-07 7 2.8 2.1 2.8 4.2 11.5 13.5 10.7 17.6 22.8 21.8 22.6 27.0

C2013-08 7 4.9 4.9 5.1 4.6 5.4 5.4 4.5 4.5 4.5 4.4 4.0 3.7

C2013-09 8 14.5 14.4 14.3 14.2 16.1 15.8 15.8 15.5 17.0 16.9 16.6 16.3

C2013-10 9 3.2 3.6 0.2 3.2 3.8 4.4 0.2 3.8 3.6 4.1 0.8 0.6

C2013-11 9 10.4 11.2 14.5 19.4 9.3 10.5 16.5 25.7 15.8 18.8 21.5 26.5

C2013-12 4 17.8 17.7 18.5 19.0 191.2 191.8 16.2 18.1 41.0 62.8 12.4 21.9

C2013-13 6 5.3 5.2 4.5 4.7 21.5 20.4 20.5 19.3 109.9 116.9 100.4 107.3

C2013-15 3 17.2 22.6 49.1 48.2 32.6 22.1 / / 8.5 58.8 / /

C2013-16 3 51.8 52.3 51.1 51.6 55.6 57.2 53.4 54.9 39.5 42.4 27.3 29.9

C2013-17 4 18.4 19.5 24.8 22.5 57.2 82.6 M a M 85.9 136.0 M M

C2014-01 9 5.4 5.5 5.2 5.2 6.9 6.7 7.1 6.9 5.9 7.3 7.5 9.9

C2014-02 8 7.4 7.4 7.4 7.4 7.9 7.9 7.9 7.9 7.7 7.7 8.4 8.4

C2014-03 8 7.5 8.2 7.1 8.0 16.6 26.8 19.3 29.7 13.9 23.1 19.0 29.0

a The big M represents a very large number of which displaying would overload the table.

5J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

completion stages,regardless ofthe optimalPC-distribution.

For these projects,the totalnumberof considered tracking

periods— needed for the overall forecastingaccuracy

evaluation — will thus be lower than nine (i.e. worse than the

bestcasesituation ofthreetracking periodsfor all three

completion stages), which can be seen from the second column

of Table 2.Moreover,we already mention that no results will

be taken into account for a certain stage of a project if it does

not contain the desired amount of three tracking periods.

3.3.Combination of the three state-of-the-art time forecasting

methods

Notice thatthe methodsproposed by Lipke (2011)and

Elshaer (2013) are in factextensions of the traditionalESM.

This is also indicated by the expression of the basic principle

of the methods,namely “integration ofactivity sensitivity

in ESM” and “integration ofactivity sensitivity in ESM”,

respectively. Indeed, both methods still produce forecasts based

on the generic formula (Eq.(1)).Khamooshiand Golafshani

(2014),on the otherhand,actually developed an approach

sprouting from ESM but with a different definition of the key

metrics (i.e. time-based instead of cost-based). Therefore, ESM

and EDM(t)can be seen as two separate methodologies for

obtaining projectduration forecastsand can thusboth be

used in combination with the approaches of Lipke (2011) and

Elshaer(2013).The implementation ofthe two extending

techniques— in what follows sometimesreferredto as

“extensions” — is completely similar for EDM(t) as for ESM

(see explanation in Sections 2.1 and 2.2).Also note thatthe

techniques of Lipke (2011) and Elshaer (2013) cannot only be

applied separately, but also combined.

Furthermore, since both the performance factors 1 and SPI(t)

are relevantfor ESM — whereas only PF = DPI is usefulin

the currentEDM(t) formulas — there is a totalof 12 time

forecasting variations to be evaluated, as appears from Table 2.

Notice thatthe traditionalESM-1 and ESM-SPI(t) are indeed

used as a benchmark,as they respectively correspond to the

third and seventh column of Table 2, where neither of the two

extensions are applied to ESM. This is indicated by the two Ns

(“No”) in the second and third row of the table. Oppositely, a Y

(“Yes”) in one of these rows signifies thatthe corresponding

technique is indeed applied.

4. Results and discussion

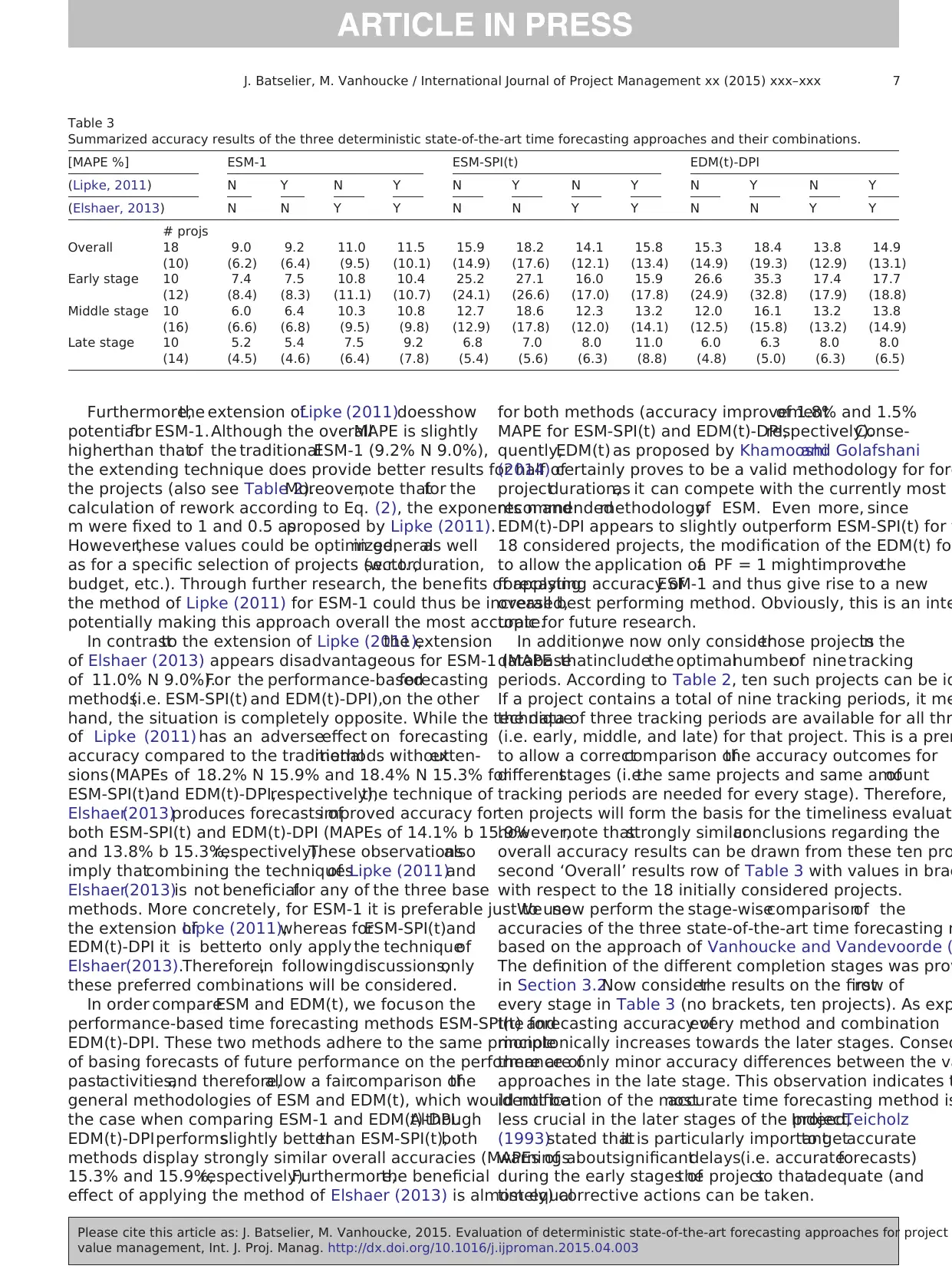

The overall accuracy results (i.e. the average accuracy over

the entire course of a project, so over all tracking periods of all

stages) of the three deterministic state-of-the-art time forecast-

ing approaches and their combinations are shown in Table 2,

for all 23 considered projects of the database ofBatselier and

Vanhoucke (2015a).However,the results forsome projects

(marked in italicsin Table 2) are notrelevantfor overall

accuracy evaluation due to various reasons,which are now

listed.

For projects C2013-01, C2013-12 and C2013-17, the results

for the firsttracking period (ata PC of 3%, 6% and 8%,

respectively)are too sensitive to variations in EV and ED(t)

because of the low levels of PV and TPD atthese very early

completion stages.Therefore,the overallresultsfor these

projects also become biased (with MAPEs of over 100%),as

they include the outcomesof the firsttracking period.For

projectC2013-15,the method of Elshaer (2013) could notbe

applied to ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI. More specifically, for

the first two tracking periods(at a PC of 4% and 22%,

respectively),the activities with a CI N 0 had notstarted yet,

yielding an ES and ED(t)equalto zero and thereforean

SPI(t) = DPI = 0.If these performance factors are inserted in

Eqs.(1) and (3),respectively,it indeed appears thatEAC(t)

cannotbe calculated (division by zero)and thusno time

forecasts can be obtained. Therefore, just as projects C201

C2013-12 and C2013-17, project C2013-15 is discarded for

overall evaluation of the forecasting accuracy of the consid

methods.Note,however,thatfor allfour projects the biasing

results only occur in the early stage (i.e.PC b 30%).Hence,

these projects can still be considered for accuracy evaluati

the middle and late stages.

ProjectC2013-13 displays biasing results for EDM(t)-DPI

due to the existence of a very expensive activity (about 85

the BAC) with a duration that is strongly disproportionate to

high cost.In such situations,EDM(t)-DPI thus appears to be

less appropriate for forecasting project duration.Nevertheless,

this situationis ratherexceptional,and therefore,project

C2013-13 is discarded for all stages to allow a fair comparis

between EDM(t)-DPIand the ESM techniques.A total of

five projectsare thus discardedfor the overalaccuracy

evaluationof the threedeterministicstate-of-the-arttime

forecasting approaches and their combinations. The summ

overallresults (i.e.overthe entire projectcourse)for the 18

retained projects are shown on the first row of MAPE-outco

of Table 3 and are now discussed.

It clearly appears thatESM-1 provides the bestbasis for

making accurate time forecasts over allstages of the project.

The ESM-1 withoutextensions shows the lowestMAPE of

9.0% and thus dominates both ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI,

which attain amaximum accuracy of14.1% and13.8%

MAPE, respectively,both with application ofthe method of

Elshaer(2013).These outcomes are notentirely unexpected,

as Batselierand Vanhoucke(2015b)alreadyindicated

thatfor ESM a PF = 1 yields more accurate forecasts than

a PF = SPI(t).By extension,it could thusbe stated that

unweighted time forecasting methods (i.e.future performance

is assumed to be as planned)outdo theirperformance-based

counterparts (i.e. future performance is assumed to be equ

the current performance), which also include EDM(t)-DPI. T

main reason forthe supremacy ofunweighted forecasting

methods — such as ESM-1 here — is that they implicitly tak

into accountpotentialcorrective actions performed by man-

agementin orderto improvelagging projectperformance.

The effectsof thesemanagementactionsare obviously

comprised in the real-life projectdata.Therefore,the current

(poor) performance expressed by the SPI(t) or DPIdoes not

adequately reflectthe actualfutureperformance,which is

subject to the corrective actions.

6 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

For these projects,the totalnumberof considered tracking

periods— needed for the overall forecastingaccuracy

evaluation — will thus be lower than nine (i.e. worse than the

bestcasesituation ofthreetracking periodsfor all three

completion stages), which can be seen from the second column

of Table 2.Moreover,we already mention that no results will

be taken into account for a certain stage of a project if it does

not contain the desired amount of three tracking periods.

3.3.Combination of the three state-of-the-art time forecasting

methods

Notice thatthe methodsproposed by Lipke (2011)and

Elshaer (2013) are in factextensions of the traditionalESM.

This is also indicated by the expression of the basic principle

of the methods,namely “integration ofactivity sensitivity

in ESM” and “integration ofactivity sensitivity in ESM”,

respectively. Indeed, both methods still produce forecasts based

on the generic formula (Eq.(1)).Khamooshiand Golafshani

(2014),on the otherhand,actually developed an approach

sprouting from ESM but with a different definition of the key

metrics (i.e. time-based instead of cost-based). Therefore, ESM

and EDM(t)can be seen as two separate methodologies for

obtaining projectduration forecastsand can thusboth be

used in combination with the approaches of Lipke (2011) and

Elshaer(2013).The implementation ofthe two extending

techniques— in what follows sometimesreferredto as

“extensions” — is completely similar for EDM(t) as for ESM

(see explanation in Sections 2.1 and 2.2).Also note thatthe

techniques of Lipke (2011) and Elshaer (2013) cannot only be

applied separately, but also combined.

Furthermore, since both the performance factors 1 and SPI(t)

are relevantfor ESM — whereas only PF = DPI is usefulin

the currentEDM(t) formulas — there is a totalof 12 time

forecasting variations to be evaluated, as appears from Table 2.

Notice thatthe traditionalESM-1 and ESM-SPI(t) are indeed

used as a benchmark,as they respectively correspond to the

third and seventh column of Table 2, where neither of the two

extensions are applied to ESM. This is indicated by the two Ns

(“No”) in the second and third row of the table. Oppositely, a Y

(“Yes”) in one of these rows signifies thatthe corresponding

technique is indeed applied.

4. Results and discussion

The overall accuracy results (i.e. the average accuracy over

the entire course of a project, so over all tracking periods of all

stages) of the three deterministic state-of-the-art time forecast-

ing approaches and their combinations are shown in Table 2,

for all 23 considered projects of the database ofBatselier and

Vanhoucke (2015a).However,the results forsome projects

(marked in italicsin Table 2) are notrelevantfor overall

accuracy evaluation due to various reasons,which are now

listed.

For projects C2013-01, C2013-12 and C2013-17, the results

for the firsttracking period (ata PC of 3%, 6% and 8%,

respectively)are too sensitive to variations in EV and ED(t)

because of the low levels of PV and TPD atthese very early

completion stages.Therefore,the overallresultsfor these

projects also become biased (with MAPEs of over 100%),as

they include the outcomesof the firsttracking period.For

projectC2013-15,the method of Elshaer (2013) could notbe

applied to ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI. More specifically, for

the first two tracking periods(at a PC of 4% and 22%,

respectively),the activities with a CI N 0 had notstarted yet,

yielding an ES and ED(t)equalto zero and thereforean

SPI(t) = DPI = 0.If these performance factors are inserted in

Eqs.(1) and (3),respectively,it indeed appears thatEAC(t)

cannotbe calculated (division by zero)and thusno time

forecasts can be obtained. Therefore, just as projects C201

C2013-12 and C2013-17, project C2013-15 is discarded for

overall evaluation of the forecasting accuracy of the consid

methods.Note,however,thatfor allfour projects the biasing

results only occur in the early stage (i.e.PC b 30%).Hence,

these projects can still be considered for accuracy evaluati

the middle and late stages.

ProjectC2013-13 displays biasing results for EDM(t)-DPI

due to the existence of a very expensive activity (about 85

the BAC) with a duration that is strongly disproportionate to

high cost.In such situations,EDM(t)-DPI thus appears to be

less appropriate for forecasting project duration.Nevertheless,

this situationis ratherexceptional,and therefore,project

C2013-13 is discarded for all stages to allow a fair comparis

between EDM(t)-DPIand the ESM techniques.A total of

five projectsare thus discardedfor the overalaccuracy

evaluationof the threedeterministicstate-of-the-arttime

forecasting approaches and their combinations. The summ

overallresults (i.e.overthe entire projectcourse)for the 18

retained projects are shown on the first row of MAPE-outco

of Table 3 and are now discussed.

It clearly appears thatESM-1 provides the bestbasis for

making accurate time forecasts over allstages of the project.

The ESM-1 withoutextensions shows the lowestMAPE of

9.0% and thus dominates both ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI,

which attain amaximum accuracy of14.1% and13.8%

MAPE, respectively,both with application ofthe method of

Elshaer(2013).These outcomes are notentirely unexpected,

as Batselierand Vanhoucke(2015b)alreadyindicated

thatfor ESM a PF = 1 yields more accurate forecasts than

a PF = SPI(t).By extension,it could thusbe stated that

unweighted time forecasting methods (i.e.future performance

is assumed to be as planned)outdo theirperformance-based

counterparts (i.e. future performance is assumed to be equ

the current performance), which also include EDM(t)-DPI. T

main reason forthe supremacy ofunweighted forecasting

methods — such as ESM-1 here — is that they implicitly tak

into accountpotentialcorrective actions performed by man-

agementin orderto improvelagging projectperformance.

The effectsof thesemanagementactionsare obviously

comprised in the real-life projectdata.Therefore,the current

(poor) performance expressed by the SPI(t) or DPIdoes not

adequately reflectthe actualfutureperformance,which is

subject to the corrective actions.

6 J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project du

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

Furthermore,the extension ofLipke (2011)doesshow

potentialfor ESM-1.Although the overallMAPE is slightly

higherthan thatof the traditionalESM-1 (9.2% N 9.0%),

the extending technique does provide better results for half of

the projects (also see Table 2).Moreover,note thatfor the

calculation of rework according to Eq. (2), the exponents n and

m were fixed to 1 and 0.5 asproposed by Lipke (2011).

However,these values could be optimized,in generalas well

as for a specific selection of projects (w.r.t.sector,duration,

budget, etc.). Through further research, the benefits of applying

the method of Lipke (2011) for ESM-1 could thus be increased,

potentially making this approach overall the most accurate.

In contrastto the extension of Lipke (2011),the extension

of Elshaer (2013) appears disadvantageous for ESM-1 (MAPE

of 11.0% N 9.0%).For the performance-basedforecasting

methods(i.e. ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI),on the other

hand, the situation is completely opposite. While the technique

of Lipke (2011) has an adverseeffect on forecasting

accuracy compared to the traditionalmethods withoutexten-

sions(MAPEs of 18.2% N 15.9% and 18.4% N 15.3% for

ESM-SPI(t)and EDM(t)-DPI,respectively),the technique of

Elshaer(2013)produces forecasts ofimproved accuracy for

both ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI (MAPEs of 14.1% b 15.9%

and 13.8% b 15.3%,respectively).These observationsalso

imply thatcombining the techniquesof Lipke (2011)and

Elshaer(2013)is not beneficialfor any of the three base

methods. More concretely, for ESM-1 it is preferable just to use

the extension ofLipke (2011),whereas forESM-SPI(t)and

EDM(t)-DPI it is betterto only apply the techniqueof

Elshaer(2013).Therefore,in followingdiscussions,only

these preferred combinations will be considered.

In order compareESM and EDM(t), we focuson the

performance-based time forecasting methods ESM-SPI(t) and

EDM(t)-DPI. These two methods adhere to the same principle

of basing forecasts of future performance on the performance of

pastactivities,and therefore,allow a faircomparison ofthe

general methodologies of ESM and EDM(t), which would not be

the case when comparing ESM-1 and EDM(t)-DPI.Although

EDM(t)-DPIperformsslightly betterthan ESM-SPI(t),both

methods display strongly similar overall accuracies (MAPEs of

15.3% and 15.9%,respectively).Furthermore,the beneficial

effect of applying the method of Elshaer (2013) is almost equal

for both methods (accuracy improvementof 1.8% and 1.5%

MAPE for ESM-SPI(t) and EDM(t)-DPI,respectively).Conse-

quently,EDM(t) as proposed by Khamooshiand Golafshani

(2014) certainly proves to be a valid methodology for fore

projectduration,as it can compete with the currently most

recommendedmethodologyof ESM. Even more, since

EDM(t)-DPI appears to slightly outperform ESM-SPI(t) for t

18 considered projects, the modification of the EDM(t) fo

to allow the application ofa PF = 1 mightimprovethe

forecasting accuracy ofESM-1 and thus give rise to a new

overall best performing method. Obviously, this is an inte

topic for future research.

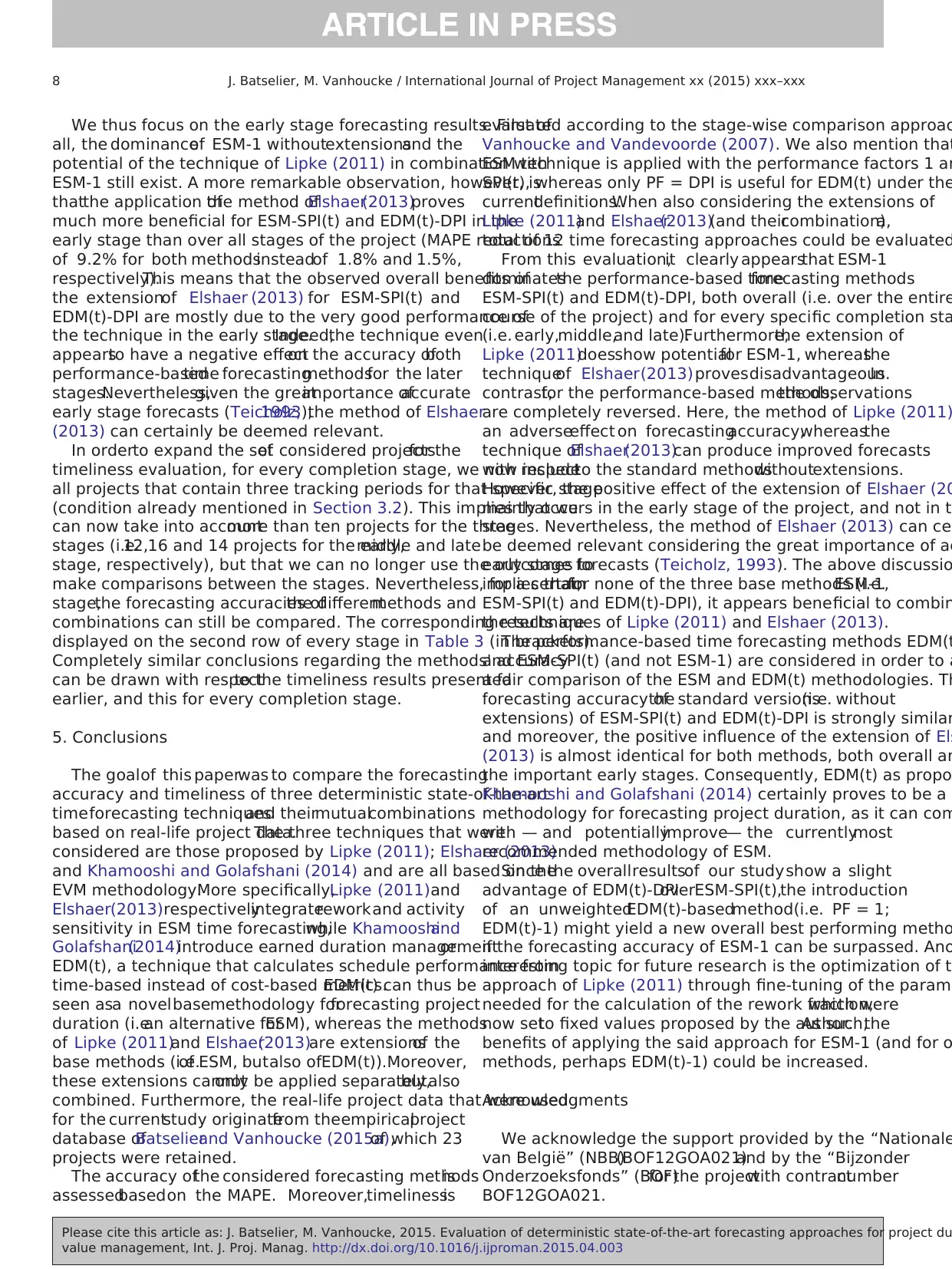

In addition,we now only considerthose projectsin the

databasethatincludethe optimalnumberof nine tracking

periods. According to Table 2, ten such projects can be id

If a project contains a total of nine tracking periods, it me

the data of three tracking periods are available for all thr

(i.e. early, middle, and late) for that project. This is a prer

to allow a correctcomparison ofthe accuracy outcomes for

differentstages (i.e.the same projects and same amountof

tracking periods are needed for every stage). Therefore,

ten projects will form the basis for the timeliness evaluat

however,note thatstrongly similarconclusions regarding the

overall accuracy results can be drawn from these ten pro

second ‘Overall’ results row of Table 3 with values in brac

with respect to the 18 initially considered projects.

We now perform the stage-wisecomparisonof the

accuracies of the three state-of-the-art time forecasting m

based on the approach of Vanhoucke and Vandevoorde (

The definition of the different completion stages was prov

in Section 3.2.Now considerthe results on the firstrow of

every stage in Table 3 (no brackets, ten projects). As exp

the forecasting accuracy ofevery method and combination

monotonically increases towards the later stages. Conseq

there are only minor accuracy differences between the va

approaches in the late stage. This observation indicates t

identification of the mostaccurate time forecasting method is

less crucial in the later stages of the project.Indeed,Teicholz

(1993)stated thatit is particularly importantto getaccurate

warningsaboutsignificantdelays(i.e. accurateforecasts)

during the early stages ofthe projectso thatadequate (and

timely) corrective actions can be taken.

Table 3

Summarized accuracy results of the three deterministic state-of-the-art time forecasting approaches and their combinations.

[MAPE %] ESM-1 ESM-SPI(t) EDM(t)-DPI

(Lipke, 2011) N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y N Y

(Elshaer, 2013) N N Y Y N N Y Y N N Y Y

# projs

Overall 18 9.0 9.2 11.0 11.5 15.9 18.2 14.1 15.8 15.3 18.4 13.8 14.9

(10) (6.2) (6.4) (9.5) (10.1) (14.9) (17.6) (12.1) (13.4) (14.9) (19.3) (12.9) (13.1)

Early stage 10 7.4 7.5 10.8 10.4 25.2 27.1 16.0 15.9 26.6 35.3 17.4 17.7

(12) (8.4) (8.3) (11.1) (10.7) (24.1) (26.6) (17.0) (17.8) (24.9) (32.8) (17.9) (18.8)

Middle stage 10 6.0 6.4 10.3 10.8 12.7 18.6 12.3 13.2 12.0 16.1 13.2 13.8

(16) (6.6) (6.8) (9.5) (9.8) (12.9) (17.8) (12.0) (14.1) (12.5) (15.8) (13.2) (14.9)

Late stage 10 5.2 5.4 7.5 9.2 6.8 7.0 8.0 11.0 6.0 6.3 8.0 8.0

(14) (4.5) (4.6) (6.4) (7.8) (5.4) (5.6) (6.3) (8.8) (4.8) (5.0) (6.3) (6.5)

7J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke / International Journal of Project Management xx (2015) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: J. Batselier, M. Vanhoucke, 2015. Evaluation of deterministic state-of-the-art forecasting approaches for project

value management, Int. J. Proj. Manag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.04.003

potentialfor ESM-1.Although the overallMAPE is slightly

higherthan thatof the traditionalESM-1 (9.2% N 9.0%),