Analyzing the Relationship Between KM, Innovation, and Performance

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/28

|15

|14551

|158

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on research published in the Journal of High Technology Management Research, investigates the quantitative relationship between knowledge management (KM), innovation, and organizational performance. The study, using data from 120 Iranian firms, explores how KM activities influence innovation and firm performance, both directly and indirectly. The research model, tested using the Structural Equation Model (SEM) by Partial Least Square (PLS) method, reveals that knowledge creation, integration, and application significantly facilitate innovation and performance. Specifically, knowledge creation impacts innovation speed, quality, and quantity, while innovation quality, knowledge creation, and integration affect overall performance. The findings provide valuable insights for academics and managers in designing KM programs to enhance innovation, efficiency, and profitability. The study also reviews existing literature on KM, organizational innovation, and the dimensions of knowledge, including production, integration, and application, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of High Technology Management Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/hitech

The Relationship Between Knowledge Management and Innovation

Performance

Amirhosein Mardania,⁎, Saghi Nikoosokhanb, Mahmoud Moradib,

Mohammad Doustarb

aFaculty of Management, University of Tehran, Jalal-al-Ahmed, Tehran, Iran

b Department of Management, University of Guilan, Rasht-Tehran Road, Rasht, Iran

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Creation

Knowledge Integration

Innovation Performance

A B S T R A C T

This study examines the quantitative relationship between knowledge management, innovation

and performance.We aim to shed some light on the consequences of Knowledge Management

(KM) activities on firm's innovation and performance.Organizations are unaware ofreal im-

plications of KM.According to the literature review,we develop a research modelshowing a

positive relationship between knowledge management, and performance as well as its impact o

innovation, which in turn contributes to the firm's performance. Using data from 120 firms that

are members of the Iranian Power Syndicate,this modelwas tested empirically.Based on the

StructuralEquation Model(SEM) results by PartialLeastSquare (PLS) method,research hy-

potheses were supported. Results show that KM activities impact innovation and organizational

performance directly, and indirectly through an increase in innovation capability. It is found tha

knowledge creation, knowledge integration, and knowledge application facilitate innovation and

performance.Knowledge creation has more significant effects on innovation speed,innovation

quality,and innovation quantity,whereas innovation quality,knowledge creation,and knowl-

edge integration has more significant effects on performance.Findings presented in this paper

may help academics and managers in designing KM programs to achieve higher innovation,

effectiveness, efficiency, and profitability.

1. Introduction

“The modern corporation,as it acceptsthe challengesof the new knowledge-based economy,will need to evolve into a

knowledge-generating,knowledge-integrating and knowledge protecting organization” (Teece,2000,p. 42). Hence,firms have to

continuously work on their specific capabilities,(e.g.dynamic capabilities) to stay competitive.(Teece & Pisano,1994).Skyrme

(2001) defines Knowledge Management (KM) as ‘the explicit and systematic management of vitalknowledge,and its associated

processes of creation,organizing,diffusion,and exploitation’.From the practice perspective,firms are noticing the importance of

managing knowledge if they want to remain competitive (Zack, 1999), and grow (Salojärvi, Furu, & Sveiby, 2005).

In the era of knowledge-based economy, resources and competencies are expected to be the crucial factors for organization

survive in dynamic and competitive environment (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). After pointing

that knowledge is an alternative to equipment, capital, materials, and labor to become the most important element in productio

Drucker (1993) predicted thatcompetitive advantage in future isdetermined by knowledge resources,or what is known as

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2018.04.002

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: a.mardani@ut.ac.ir (A. Mardani).

Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

1047-8310/ © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

T

Journal of High Technology Management Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/hitech

The Relationship Between Knowledge Management and Innovation

Performance

Amirhosein Mardania,⁎, Saghi Nikoosokhanb, Mahmoud Moradib,

Mohammad Doustarb

aFaculty of Management, University of Tehran, Jalal-al-Ahmed, Tehran, Iran

b Department of Management, University of Guilan, Rasht-Tehran Road, Rasht, Iran

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Creation

Knowledge Integration

Innovation Performance

A B S T R A C T

This study examines the quantitative relationship between knowledge management, innovation

and performance.We aim to shed some light on the consequences of Knowledge Management

(KM) activities on firm's innovation and performance.Organizations are unaware ofreal im-

plications of KM.According to the literature review,we develop a research modelshowing a

positive relationship between knowledge management, and performance as well as its impact o

innovation, which in turn contributes to the firm's performance. Using data from 120 firms that

are members of the Iranian Power Syndicate,this modelwas tested empirically.Based on the

StructuralEquation Model(SEM) results by PartialLeastSquare (PLS) method,research hy-

potheses were supported. Results show that KM activities impact innovation and organizational

performance directly, and indirectly through an increase in innovation capability. It is found tha

knowledge creation, knowledge integration, and knowledge application facilitate innovation and

performance.Knowledge creation has more significant effects on innovation speed,innovation

quality,and innovation quantity,whereas innovation quality,knowledge creation,and knowl-

edge integration has more significant effects on performance.Findings presented in this paper

may help academics and managers in designing KM programs to achieve higher innovation,

effectiveness, efficiency, and profitability.

1. Introduction

“The modern corporation,as it acceptsthe challengesof the new knowledge-based economy,will need to evolve into a

knowledge-generating,knowledge-integrating and knowledge protecting organization” (Teece,2000,p. 42). Hence,firms have to

continuously work on their specific capabilities,(e.g.dynamic capabilities) to stay competitive.(Teece & Pisano,1994).Skyrme

(2001) defines Knowledge Management (KM) as ‘the explicit and systematic management of vitalknowledge,and its associated

processes of creation,organizing,diffusion,and exploitation’.From the practice perspective,firms are noticing the importance of

managing knowledge if they want to remain competitive (Zack, 1999), and grow (Salojärvi, Furu, & Sveiby, 2005).

In the era of knowledge-based economy, resources and competencies are expected to be the crucial factors for organization

survive in dynamic and competitive environment (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). After pointing

that knowledge is an alternative to equipment, capital, materials, and labor to become the most important element in productio

Drucker (1993) predicted thatcompetitive advantage in future isdetermined by knowledge resources,or what is known as

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2018.04.002

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: a.mardani@ut.ac.ir (A. Mardani).

Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

1047-8310/ © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

T

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

knowledge workers.

In the dynamic capabilities approach that roots in the resource-based view of the firm by Penrose (1959),a pivotal role for

strategic management is opened (Kor & Mahoney, 2004). Among the management objectives proposed by this approach, the m

agement of a firm's knowledge resources, with respect to a firm's innovativeness, has increasingly attracted attention over the

decade. An increasing amount of research on innovation and strategic management puts knowledge in the center of interest (D

2005; Davenport, De Long, & Beers, 1997; Grant, 1996; Hall & Andriani, 2002; Hargadon, 1998; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Swa

Newell, Scarbrough, & Hislop, 1999). In the innovation literature, knowledge is discussed as the element of a recombination pro

to generate innovation (Galunic & Rodan, 1998; Grant, 1996). Knowledge has an inherent value to be managed, applied, develo

and exploited. Knowledge can be seen as an asset that raises traditional asset questions to management such as when, how m

what to invest in. As the necessary intangible assets for any organizations, knowledge should be elaborately managed. Conseq

both scholars and practitioners have increasingly paid great attention to an organization's ability to identify, capture, create, sh

accumulate knowledge (Jang, Hong, Bock, & Kim, 2002; Kogut & Zander, 1996; Michailova & Husted, 2003; Nonaka & Takeuchi,

1995).Owing to the particular properties of knowledge,however,knowledge assets require special attention.Knowledge is often

embedded in employees, has features of a public good (Jaffe, 1986, p. 984; Liebeskind, 1997), and can hardly be bought in the

(Hall and Mairesse, 2006, p. 296). Therefore, innovating firms need a sophisticated Knowledge Management (KM) that pays a lo

attention to the special requirements of interactive knowledge, and dimensions of knowledge (creation). Particularly in the eme

distributed organizations,effectiveness is highly dependent on how well knowledge is shared between individuals,teams,and/or

units (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Argote & Ingram, 2000; Huseman & Goodman, 1998;Pentland, 1995). Knowledge sharing behavior

have been argued to contribute to the generation of various organizational capabilities such as innovation, which is vital to a fir

performance (Kogut & Zander, 1996). The importance of KM and its relationship with innovation is widely acknowledged. Howev

it is difficult to draw conclusions from the extant literature about the relationship between effective KM,innovation,and perfor-

mance.Empiricalwork, however,is still in its infancy,and characterized by heterogeneous measurement approaches (Halland

Mairesse, 2006, p. 296). Various studies on technological (ICT-based) (Adamides & Karacapilidis, 2006), human resource (Carte

Scarbrough, 2001), or social aspects (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000) of KM exist, focusing on innovation types in general (Darroc

2005). Despite the importance of these results, approaches that attempt to measure firms'success with innovations achieved through

KM when innovation success is quantified (measured in economic terms such as sales generated) are still scarce. The first step

this gap in the literature is presented in this paper.

This study aims to examine the relationships between knowledge management activities, innovation, and firm performance

a holistic perspective. According to a survey including 226 experts from 120 enterprises in Iran, which are the members of Irani

power syndicate, this study employed modeling to investigate the research hypotheses within their organizations.

Thus, the following questions may arise: whether Knowledge creation, knowledge integration, knowledge application influen

firm performance directly? What are the key factors affected by knowledge management activities that lead to firm performanc

Does KM, through innovation, have an impact on a firm's success? According to knowledge management literatures, this paper

that Knowledge creation,knowledge integration,and knowledge application not only have positive relationship with firm perfor-

mance directly but also influence innovation speed, quality and quantity that are related to firm performance.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follow:Section 2 presents the literature review for introducing key constructs of our

research. Section 3 develops a research model to depict hypothesized relationships.Section 4 provides research methodology and

data collection. Data analysis and the findings are reported in Section 5. Finally, conclusions, limitations and further research su

gestions are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

Our literature review is centered on our main research question: “Does KM have impacts on a firm's success through innova

Before reviewing studies dealing with the link between KM and the success of innovation activities, we start our literature revie

with papers related to definitions and forms of KM.

2.1. Knowledge Management

Gold, Malhortra,and Segars (2001) examined the issue of effective Knowledge Management (KM) from the perspective of or-

ganizational capabilities. This perspective states that a knowledge infrastructure including technology, structure, and culture al

with a knowledge process architecture ofacquisition,conversion,application,and protection are essentialorganizationalcap-

abilities,or “preconditions” for effective knowledge management.The results provide a basis to understand the competitive pre-

disposition of a firm as it enters a program of KM. Cui, Griffith, and Cavusgil (2005) also mentioned that KM capabilities consist

three interrelated processes: knowledge acquisition, knowledge conversion, and knowledge application (Gold et al., 2001). Kno

edge is not only an important resource of a firm, but it also is a main source of competitive advantage (Gold et al., 2001; Grant,

Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). Therefore, KM capabilities refer to the knowledge management processes that develop, and use knowle

within a firm (Gold et al., 2001).

Several definitions have been around KM (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Coombs & Hull, 1998; Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Nonaka &

Takeuchi, 1995; Probst, Raub, & Romhardt, 1999). Different approaches to KM concentrate on the creation, diffusion, storage, a

application of existing, or new knowledge (e.g. Coombs & Hull, 1998). Wiig (1997) puts his emphasis on the management of ex

knowledge, Wiig states that the purpose of KM is “to maximize the enterprise's knowledge related effectiveness and returns fro

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

13

In the dynamic capabilities approach that roots in the resource-based view of the firm by Penrose (1959),a pivotal role for

strategic management is opened (Kor & Mahoney, 2004). Among the management objectives proposed by this approach, the m

agement of a firm's knowledge resources, with respect to a firm's innovativeness, has increasingly attracted attention over the

decade. An increasing amount of research on innovation and strategic management puts knowledge in the center of interest (D

2005; Davenport, De Long, & Beers, 1997; Grant, 1996; Hall & Andriani, 2002; Hargadon, 1998; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Swa

Newell, Scarbrough, & Hislop, 1999). In the innovation literature, knowledge is discussed as the element of a recombination pro

to generate innovation (Galunic & Rodan, 1998; Grant, 1996). Knowledge has an inherent value to be managed, applied, develo

and exploited. Knowledge can be seen as an asset that raises traditional asset questions to management such as when, how m

what to invest in. As the necessary intangible assets for any organizations, knowledge should be elaborately managed. Conseq

both scholars and practitioners have increasingly paid great attention to an organization's ability to identify, capture, create, sh

accumulate knowledge (Jang, Hong, Bock, & Kim, 2002; Kogut & Zander, 1996; Michailova & Husted, 2003; Nonaka & Takeuchi,

1995).Owing to the particular properties of knowledge,however,knowledge assets require special attention.Knowledge is often

embedded in employees, has features of a public good (Jaffe, 1986, p. 984; Liebeskind, 1997), and can hardly be bought in the

(Hall and Mairesse, 2006, p. 296). Therefore, innovating firms need a sophisticated Knowledge Management (KM) that pays a lo

attention to the special requirements of interactive knowledge, and dimensions of knowledge (creation). Particularly in the eme

distributed organizations,effectiveness is highly dependent on how well knowledge is shared between individuals,teams,and/or

units (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Argote & Ingram, 2000; Huseman & Goodman, 1998;Pentland, 1995). Knowledge sharing behavior

have been argued to contribute to the generation of various organizational capabilities such as innovation, which is vital to a fir

performance (Kogut & Zander, 1996). The importance of KM and its relationship with innovation is widely acknowledged. Howev

it is difficult to draw conclusions from the extant literature about the relationship between effective KM,innovation,and perfor-

mance.Empiricalwork, however,is still in its infancy,and characterized by heterogeneous measurement approaches (Halland

Mairesse, 2006, p. 296). Various studies on technological (ICT-based) (Adamides & Karacapilidis, 2006), human resource (Carte

Scarbrough, 2001), or social aspects (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000) of KM exist, focusing on innovation types in general (Darroc

2005). Despite the importance of these results, approaches that attempt to measure firms'success with innovations achieved through

KM when innovation success is quantified (measured in economic terms such as sales generated) are still scarce. The first step

this gap in the literature is presented in this paper.

This study aims to examine the relationships between knowledge management activities, innovation, and firm performance

a holistic perspective. According to a survey including 226 experts from 120 enterprises in Iran, which are the members of Irani

power syndicate, this study employed modeling to investigate the research hypotheses within their organizations.

Thus, the following questions may arise: whether Knowledge creation, knowledge integration, knowledge application influen

firm performance directly? What are the key factors affected by knowledge management activities that lead to firm performanc

Does KM, through innovation, have an impact on a firm's success? According to knowledge management literatures, this paper

that Knowledge creation,knowledge integration,and knowledge application not only have positive relationship with firm perfor-

mance directly but also influence innovation speed, quality and quantity that are related to firm performance.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follow:Section 2 presents the literature review for introducing key constructs of our

research. Section 3 develops a research model to depict hypothesized relationships.Section 4 provides research methodology and

data collection. Data analysis and the findings are reported in Section 5. Finally, conclusions, limitations and further research su

gestions are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

Our literature review is centered on our main research question: “Does KM have impacts on a firm's success through innova

Before reviewing studies dealing with the link between KM and the success of innovation activities, we start our literature revie

with papers related to definitions and forms of KM.

2.1. Knowledge Management

Gold, Malhortra,and Segars (2001) examined the issue of effective Knowledge Management (KM) from the perspective of or-

ganizational capabilities. This perspective states that a knowledge infrastructure including technology, structure, and culture al

with a knowledge process architecture ofacquisition,conversion,application,and protection are essentialorganizationalcap-

abilities,or “preconditions” for effective knowledge management.The results provide a basis to understand the competitive pre-

disposition of a firm as it enters a program of KM. Cui, Griffith, and Cavusgil (2005) also mentioned that KM capabilities consist

three interrelated processes: knowledge acquisition, knowledge conversion, and knowledge application (Gold et al., 2001). Kno

edge is not only an important resource of a firm, but it also is a main source of competitive advantage (Gold et al., 2001; Grant,

Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). Therefore, KM capabilities refer to the knowledge management processes that develop, and use knowle

within a firm (Gold et al., 2001).

Several definitions have been around KM (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Coombs & Hull, 1998; Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Nonaka &

Takeuchi, 1995; Probst, Raub, & Romhardt, 1999). Different approaches to KM concentrate on the creation, diffusion, storage, a

application of existing, or new knowledge (e.g. Coombs & Hull, 1998). Wiig (1997) puts his emphasis on the management of ex

knowledge, Wiig states that the purpose of KM is “to maximize the enterprise's knowledge related effectiveness and returns fro

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

13

knowledge assets, and to renew them constantly” (Wiig, 1997, p. 2). Davenport and Prusak (1998) stress that KM consists of m

knowledge visible and developing a knowledge-intensive culture. Several studies identified acquisition, identification, developm

diffusion, usage, and repository of knowledge as core KM processes (e.g. Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Probst et al., 1999). Swan, New

Scarbrough, et al. (1999) argue that knowledge exploration and exploitation are the core objectives of KM. KM implementation

be divided into IT-based KM, and human-resource-related KM, as well as process-based approaches (Tidd, Bessant, & Pavitt, 20

IT-based or supply-driven KM emphasizes the need for (easy) access to existing knowledge stored in databases,or elsewhere

(Swan, Newell, Scarbrough,et al., 1999). In contrast, the demand-driven approach is more concerned with facilitating interactive

knowledge sharing, and knowledge creation (Swan, Newell, Scarbrough, et al., 1999).

Although there are still many classifications of KM, this study prefers three Dimensions of knowledge. These dimensions are

follow:

1. Production of Knowledge including knowledge acquisition, and knowledge creation

2. Integration of Knowledge including knowledge storage, and knowledge distribution

3. Application of Knowledge including protection, and use of knowledge

2.2. OrganizationalInnovation

Basically, there are two types of innovation: product and process innovation (Dosi, 1988; Teece, 1989; Utterback & Abernath

1975).These are not mutually preclusive,but depend on each other in a major degree.Process innovations can furthermore be

divided into organization (i.e. new market organization and internal company organization), and technology (i.e. human artifact

Technology can be classified as three entities (Gehlen, 1980, p. 19): instrument, machine, and automaton. This concept of tech

separates us from Johnson (1992, p. 28), among others, where he makes the following statement: “knowledge used in the prod

process is called technology”. This question should be asked from Johnson: what about “tacit knowledge”? If “tacit knowledge”

a part of the technology concept, technology will lose its analytical purpose. This also applies if all explicit knowledge is include

the technology concept.

Innovation can also be seen as incremental(i.e. small step-by step improvements,or continuous innovation),or radical (i.e.

something qualitatively new, or a breakthrough) (Dewar & Dutton, 1986; Ettlie, Bridges, & O'Keffe, 1984; Freeman, 1992; Mans

1968; Mokyr, 1990; Zaltman, Duncan, & Holbek, 1973). Continuous and radical innovation can also be autonomous. One examp

autonomous innovation is “snowboard”.One example of systemic innovation is IBM's OS/2,which presupposed change in other

systems in the value chain.

The growth innovation literature provides many alternative conceptualizations and models for the interpretation of observed

data. An innovation can be a new product or service, a new production process technology, a new structure or administrative sy

or a new plan or program pertaining to organizational members. Therefore, organizational innovation or innovativeness is typic

measured by the rate ofinnovation adoption.A few studies,however,have used other measures to measure organizationalin-

novativeness (Damanpour, 1991). Former research has argued that different types of innovation are necessary for understandi

identifying in organizations.

Among numerous typologies of innovation in the literature, three have gained the most attention. Each centers on a pair of

of innovation: administrative and technical, product and process, and radical and incremental. Wang and Ahmed (2004) identifi

organizational innovation through an extensive literature. These five dimensions are tested from component factors. They are p

innovation, market innovation, process innovation, behavioral innovation, and strategic innovation. Although there are still man

classifications of innovation, this study prefers three aspects of innovation:

1. Innovation speed;

2. Innovation quality; and

3. Innovation quantity.

Innovation speed, which is defined as the time elapsed between initial development, including the conception and definition

innovation, and ultimate commercialization of a new product or services into the marketplace, reflects a firm's capability to acc

erate activities and tasks,build a competitive advantage relative to its competitors within industries with shortened product life

cycles (Allocca & Kessler, 2006; Kessler & Bierly III, 2002; Kessler & Chakrabarti, 1996). Emphasis on innovation speed represen

paradigm shiftfrom traditionalsources ofadvantage to a strategic orientation,specifically suited for today's rapidly changing

business environments.Innovation speed is a crucialelementto compete in the marketand can lead to superior performance.

Empirical studies confirm a positive relationship between speed-to-market and overall new product success (Carbonell & Escud

2010; Carbonell & Rodriguez, 2006; Carbonell & Rodriguez-Escudero, 2009). Since innovation speed is a team embodied and so

complex capability- that cannot be easily developed or imitable by competitors (Slater & Mohr, 2006)- it enables firms to keep i

close touch with customers, and their needs (Tatikonda & Montoya-Weiss, 2001). Furthermore, the increasing rate of competitio

technological developments in the marketplace,and shorter product life cycles force companies to hasten innovation (Heirman &

Clarysse, 2007).

The concept of innovation quality allows us to make a statement regarding the aggregated innovation performance in every

domain within an organization,by comparing the result,being a product,process or service innovation,with the potentialand

considering the process on how these results have been achieved (Haner,2002;Lanjouw & Schankerman,2004).With respect to

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

14

knowledge visible and developing a knowledge-intensive culture. Several studies identified acquisition, identification, developm

diffusion, usage, and repository of knowledge as core KM processes (e.g. Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Probst et al., 1999). Swan, New

Scarbrough, et al. (1999) argue that knowledge exploration and exploitation are the core objectives of KM. KM implementation

be divided into IT-based KM, and human-resource-related KM, as well as process-based approaches (Tidd, Bessant, & Pavitt, 20

IT-based or supply-driven KM emphasizes the need for (easy) access to existing knowledge stored in databases,or elsewhere

(Swan, Newell, Scarbrough,et al., 1999). In contrast, the demand-driven approach is more concerned with facilitating interactive

knowledge sharing, and knowledge creation (Swan, Newell, Scarbrough, et al., 1999).

Although there are still many classifications of KM, this study prefers three Dimensions of knowledge. These dimensions are

follow:

1. Production of Knowledge including knowledge acquisition, and knowledge creation

2. Integration of Knowledge including knowledge storage, and knowledge distribution

3. Application of Knowledge including protection, and use of knowledge

2.2. OrganizationalInnovation

Basically, there are two types of innovation: product and process innovation (Dosi, 1988; Teece, 1989; Utterback & Abernath

1975).These are not mutually preclusive,but depend on each other in a major degree.Process innovations can furthermore be

divided into organization (i.e. new market organization and internal company organization), and technology (i.e. human artifact

Technology can be classified as three entities (Gehlen, 1980, p. 19): instrument, machine, and automaton. This concept of tech

separates us from Johnson (1992, p. 28), among others, where he makes the following statement: “knowledge used in the prod

process is called technology”. This question should be asked from Johnson: what about “tacit knowledge”? If “tacit knowledge”

a part of the technology concept, technology will lose its analytical purpose. This also applies if all explicit knowledge is include

the technology concept.

Innovation can also be seen as incremental(i.e. small step-by step improvements,or continuous innovation),or radical (i.e.

something qualitatively new, or a breakthrough) (Dewar & Dutton, 1986; Ettlie, Bridges, & O'Keffe, 1984; Freeman, 1992; Mans

1968; Mokyr, 1990; Zaltman, Duncan, & Holbek, 1973). Continuous and radical innovation can also be autonomous. One examp

autonomous innovation is “snowboard”.One example of systemic innovation is IBM's OS/2,which presupposed change in other

systems in the value chain.

The growth innovation literature provides many alternative conceptualizations and models for the interpretation of observed

data. An innovation can be a new product or service, a new production process technology, a new structure or administrative sy

or a new plan or program pertaining to organizational members. Therefore, organizational innovation or innovativeness is typic

measured by the rate ofinnovation adoption.A few studies,however,have used other measures to measure organizationalin-

novativeness (Damanpour, 1991). Former research has argued that different types of innovation are necessary for understandi

identifying in organizations.

Among numerous typologies of innovation in the literature, three have gained the most attention. Each centers on a pair of

of innovation: administrative and technical, product and process, and radical and incremental. Wang and Ahmed (2004) identifi

organizational innovation through an extensive literature. These five dimensions are tested from component factors. They are p

innovation, market innovation, process innovation, behavioral innovation, and strategic innovation. Although there are still man

classifications of innovation, this study prefers three aspects of innovation:

1. Innovation speed;

2. Innovation quality; and

3. Innovation quantity.

Innovation speed, which is defined as the time elapsed between initial development, including the conception and definition

innovation, and ultimate commercialization of a new product or services into the marketplace, reflects a firm's capability to acc

erate activities and tasks,build a competitive advantage relative to its competitors within industries with shortened product life

cycles (Allocca & Kessler, 2006; Kessler & Bierly III, 2002; Kessler & Chakrabarti, 1996). Emphasis on innovation speed represen

paradigm shiftfrom traditionalsources ofadvantage to a strategic orientation,specifically suited for today's rapidly changing

business environments.Innovation speed is a crucialelementto compete in the marketand can lead to superior performance.

Empirical studies confirm a positive relationship between speed-to-market and overall new product success (Carbonell & Escud

2010; Carbonell & Rodriguez, 2006; Carbonell & Rodriguez-Escudero, 2009). Since innovation speed is a team embodied and so

complex capability- that cannot be easily developed or imitable by competitors (Slater & Mohr, 2006)- it enables firms to keep i

close touch with customers, and their needs (Tatikonda & Montoya-Weiss, 2001). Furthermore, the increasing rate of competitio

technological developments in the marketplace,and shorter product life cycles force companies to hasten innovation (Heirman &

Clarysse, 2007).

The concept of innovation quality allows us to make a statement regarding the aggregated innovation performance in every

domain within an organization,by comparing the result,being a product,process or service innovation,with the potentialand

considering the process on how these results have been achieved (Haner,2002;Lanjouw & Schankerman,2004).With respect to

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

14

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

products or services, innovation quality may be defined through variables such as effectiveness, features, reliability, timing, cos

complexity,innovation degree,value to the customer,and more.Similar are the things with respectto the process domain of

innovation quality. Although innovation quality is one of the most important factors for the company that applies innovation stra

to compete in the market,determining it might be faced with more challenges due to the increased complexity,the difficulty to

identify catalysts,and the need to integrate measurements on so-called soft issues(e.g.relative citation ratio,citation-weighted

patents, science linkage, scope of innovations, and so on) (Lahiri, 2010; Ng, 2009; Tseng & Wu, 2007).

Quantity innovation is defined as the number of new or improved products and services launched to the market that are sup

to the average of the industry. It also is defined as the number of new or improved processes that are superior to the average o

industry.

Organizational interest in KM is stimulated by the possibility of subsequent benefits such as increased creativity, and innova

in products and services (Darroch, 2005; Moffett, McAdam, & Parkinson, 2002). In fact, knowledge contributes to producing crea

thoughts and generating innovation (Borghini,2005). That is why innovation is seen as the area ofgreatestpayoff from KM

(Majchrzak, Cooper, & Neece, 2004).

2.3. Knowledge Management and Innovative Success

Looking at the relationship between KM and innovation activities we first draw on Schumpeter. According to him, innovation

the result of a recombination of conceptual and physical materials that were previously in existence (Schumpeter, 1935). In oth

words, innovation is the combination of a firm's existing knowledge assets to create new knowledge. Therefore, the primary tas

the innovating firm is to reconfigure existing knowledge assets and resources,and to examine new knowledge (Galunic & Rodan,

1998; Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Both exploration and exploitation of knowledge have been shown to contribute t

innovativeness of firms,and to its competitive advantage (Hall & Andriani,2002;Levinthal & March,1993;March, 1991;Swan,

Newell, Scarbrough, et al., 1999). Various studies focus on the role of KM in the innovation process. The results found by Liao an

Chuang (2006) support the vitalrole of KM in knowledge processing capability and in turn,in speed and activity of innovation.

Huergo (2006) provides evidence to support the positive role of technology management in success of firm innovations. A diffe

approach is applied by Yang (2005). He assumes that moderating effects of marketing and manufacturing competencies, know

acquisition, knowledge dissemination,knowledge integration,and knowledge innovation improve new product performance.This

finding is supported by Brockman and Morgan (2003).They argue thatthe KM tools such as “use ofinnovative information”,

“efficient information gathering” and “shared interpretation” improve the performance and innovativeness of new products.With

regard to specialfocus on “demand-driven”,or “collaborative” KM methods,theoreticalconsiderations provide ambiguous argu-

ments. Alavi and Leidner (2001) argue that excessively close ties in a knowledge-sharing community may limit knowledge crea

due to redundant information. On the other hand, Brown and Duguid (1991) and Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) make the

that a shared knowledge base increases knowledge creation within the community.Empiricalcase study evidence shows mixed

results as well. Findings of Darroch et al. are a good example. Darroch (2005) confirms the positive role of knowledge dissemina

on innovation success, while Darroch and McNaughton (2002) do not find any significant effects. Another aspect of the link betw

KM and innovation is how different types of innovation are affected by KM. According to Darroch and McNaughton (2002) differe

types of innovation require different resources and hence a differentiated KM strategy. They investigate the effects of KM on th

types of innovation. According to their findings different KM activities are important for different types of innovative success. He

we expect that KM acts differently on different type of innovation success, as well as speed, quality, and quantity innovation su

3. Consequences of KM and Innovation Success

3.1. Effects of KM on innovation

The innovative efforts include discovery, experimentation, and development of new technologies, new products and/or servi

new production processes,and new organizationalstructures.Innovation is about implementing ideas (Borghini,2005).The Lit-

erature (Daft, 1982; Damanpour & Evan, 1984) describes innovation as internally acquired element, new structure or administr

system,policy, new plan or program,new production process,and product,or service to a company.Innovation process highly

depends on knowledge (Gloet & Terziovski,2004),specially tacit knowledge (Leonard & Sensiper,1998). Transforming general

knowledge into specific knowledge,new and valuable knowledge is created and converted into products,services,and processes

(Choy,Yew, & Lin, 2006).Studies on knowledge creation by Nonaka consider knowledge as a main requisite for innovation and

competitiveness (Nonaka,1994).A KM system that expands the creativity envelope is thought to improve the innovation process

through quicker access and trend of new knowledge (Majchrzak et al., 2004). Also, effective KM is a critical success factor to launch

new products. In this sense, this paper supports that one of the factors influencing innovation capacity in organizations is know

and its management. Darroch (2005) provides empirical evidence to support the view that a firm with a capability in KM is also

to be more innovative. Also, Massey, Montoya-Weiss, and O'Driscoll (2002) tell the story of a real company that implemented a

strategy,and enhanced innovation process and performance.Swan,Newell, and Robertson (1999) also compared the impact on

innovation in different KM programs implemented in two organizations.

Thus,a close link between the organization's knowledge and its capacity to innovate exists (Borghini,2005).A few empirical

research has specifically addressed antecedents and consequences of the production, Integration, and Application of Knowledg

innovation,and performance.The management of knowledge is frequently identified as an important antecedent of innovation.

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

15

complexity,innovation degree,value to the customer,and more.Similar are the things with respectto the process domain of

innovation quality. Although innovation quality is one of the most important factors for the company that applies innovation stra

to compete in the market,determining it might be faced with more challenges due to the increased complexity,the difficulty to

identify catalysts,and the need to integrate measurements on so-called soft issues(e.g.relative citation ratio,citation-weighted

patents, science linkage, scope of innovations, and so on) (Lahiri, 2010; Ng, 2009; Tseng & Wu, 2007).

Quantity innovation is defined as the number of new or improved products and services launched to the market that are sup

to the average of the industry. It also is defined as the number of new or improved processes that are superior to the average o

industry.

Organizational interest in KM is stimulated by the possibility of subsequent benefits such as increased creativity, and innova

in products and services (Darroch, 2005; Moffett, McAdam, & Parkinson, 2002). In fact, knowledge contributes to producing crea

thoughts and generating innovation (Borghini,2005). That is why innovation is seen as the area ofgreatestpayoff from KM

(Majchrzak, Cooper, & Neece, 2004).

2.3. Knowledge Management and Innovative Success

Looking at the relationship between KM and innovation activities we first draw on Schumpeter. According to him, innovation

the result of a recombination of conceptual and physical materials that were previously in existence (Schumpeter, 1935). In oth

words, innovation is the combination of a firm's existing knowledge assets to create new knowledge. Therefore, the primary tas

the innovating firm is to reconfigure existing knowledge assets and resources,and to examine new knowledge (Galunic & Rodan,

1998; Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Both exploration and exploitation of knowledge have been shown to contribute t

innovativeness of firms,and to its competitive advantage (Hall & Andriani,2002;Levinthal & March,1993;March, 1991;Swan,

Newell, Scarbrough, et al., 1999). Various studies focus on the role of KM in the innovation process. The results found by Liao an

Chuang (2006) support the vitalrole of KM in knowledge processing capability and in turn,in speed and activity of innovation.

Huergo (2006) provides evidence to support the positive role of technology management in success of firm innovations. A diffe

approach is applied by Yang (2005). He assumes that moderating effects of marketing and manufacturing competencies, know

acquisition, knowledge dissemination,knowledge integration,and knowledge innovation improve new product performance.This

finding is supported by Brockman and Morgan (2003).They argue thatthe KM tools such as “use ofinnovative information”,

“efficient information gathering” and “shared interpretation” improve the performance and innovativeness of new products.With

regard to specialfocus on “demand-driven”,or “collaborative” KM methods,theoreticalconsiderations provide ambiguous argu-

ments. Alavi and Leidner (2001) argue that excessively close ties in a knowledge-sharing community may limit knowledge crea

due to redundant information. On the other hand, Brown and Duguid (1991) and Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) make the

that a shared knowledge base increases knowledge creation within the community.Empiricalcase study evidence shows mixed

results as well. Findings of Darroch et al. are a good example. Darroch (2005) confirms the positive role of knowledge dissemina

on innovation success, while Darroch and McNaughton (2002) do not find any significant effects. Another aspect of the link betw

KM and innovation is how different types of innovation are affected by KM. According to Darroch and McNaughton (2002) differe

types of innovation require different resources and hence a differentiated KM strategy. They investigate the effects of KM on th

types of innovation. According to their findings different KM activities are important for different types of innovative success. He

we expect that KM acts differently on different type of innovation success, as well as speed, quality, and quantity innovation su

3. Consequences of KM and Innovation Success

3.1. Effects of KM on innovation

The innovative efforts include discovery, experimentation, and development of new technologies, new products and/or servi

new production processes,and new organizationalstructures.Innovation is about implementing ideas (Borghini,2005).The Lit-

erature (Daft, 1982; Damanpour & Evan, 1984) describes innovation as internally acquired element, new structure or administr

system,policy, new plan or program,new production process,and product,or service to a company.Innovation process highly

depends on knowledge (Gloet & Terziovski,2004),specially tacit knowledge (Leonard & Sensiper,1998). Transforming general

knowledge into specific knowledge,new and valuable knowledge is created and converted into products,services,and processes

(Choy,Yew, & Lin, 2006).Studies on knowledge creation by Nonaka consider knowledge as a main requisite for innovation and

competitiveness (Nonaka,1994).A KM system that expands the creativity envelope is thought to improve the innovation process

through quicker access and trend of new knowledge (Majchrzak et al., 2004). Also, effective KM is a critical success factor to launch

new products. In this sense, this paper supports that one of the factors influencing innovation capacity in organizations is know

and its management. Darroch (2005) provides empirical evidence to support the view that a firm with a capability in KM is also

to be more innovative. Also, Massey, Montoya-Weiss, and O'Driscoll (2002) tell the story of a real company that implemented a

strategy,and enhanced innovation process and performance.Swan,Newell, and Robertson (1999) also compared the impact on

innovation in different KM programs implemented in two organizations.

Thus,a close link between the organization's knowledge and its capacity to innovate exists (Borghini,2005).A few empirical

research has specifically addressed antecedents and consequences of the production, Integration, and Application of Knowledg

innovation,and performance.The management of knowledge is frequently identified as an important antecedent of innovation.

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

15

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Effective KM is presented in the literature as a method for improving innovation and performance. We obtained the result that K

processes positively affect innovation. Therefore, it is fair to conclude that KM process and innovation are closely related. Thus,

posit the followings:

H1. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H2. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H3. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H4. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H5. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H6. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H7. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

H8. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

H9. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

3.2. KM Effects on Organizational Performance

Prior conceptualresearch state thatKM can improve corporate performance and competitiveness (Civi,2000; DeTienne &

Jackson, 2001; Holsapple & Jones, 2004, 2005). KM programs are successful as corporate performance is improved. Therefore, i

essentialto measure KM contributions to performance (Tseng,2008),especially when there is no conclusive research on the re-

lationship between the production,Integration,Application of knowledge and firm performance (Yang,2010).Corporate perfor-

mance is a multidimensional concept and accounts for firm's position regarding to competitors. A comprehensive view of corpo

performance not only considers the financial perspective, but also others aspects that allow monitoring value creation. Based o

view some methodologies have been developed. The most popular methodology is the Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1

Some studies recognize the impact of strategic KM on different dimensions of corporate performance (McKeen, Zack, & Singh, 2

Nevertheless,most of them focus on hard financialoutcomes (e.g.cost,profit, etc.) to evaluate KM (Vaccaro,Parente,& Veloso,

2010), while ignoring soft non-financial outcomes such as operating costs, shorten lead-time, and differentiate products (Sher &

2004); developing new services (Storey & Kahn, 2010); improving its ability to attract, train, develop, and retain employee (Tho

& Keithley, 2002); and improving coordination efforts (Wu & Lin, 2009). since diverse dimensions of performance are affected b

strategy, K M system performance should combine financial and nonfinancial measures (Tseng, 2008; Wu & Lin, 2009). We sug

that the impact of KM strategy on firm performance should be better studied by analyzing different dimensions of corporate pe

formance.Three dimensions will be employed to measure KM contributions to corporate performance:(1) financialperformance

including market performance (profitability, growth and customer satisfaction); (2) process performance, which refers to quality

efficiency;and (3) internalperformance,which relates to individualcapabilities (employees'qualification,satisfaction and crea-

tivity). Thus, this study proposes:

H10. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H11. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H12. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

3.3. Innovation Effects on OrganizationalPerformance

Innovation is recognized as a significant enabler for firms to create value and sustain competitive advantage in the increasin

complex and rapidly changing environment (Bilton & Cummings, 2009; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). In general, innovation n

only makes full use of existing resources,improve efficiency and potential value,but also brings new intangible assets into orga-

nization.Firms with greater innovativeness willbe more successfulin responding to customers'needs,and in developing new

capabilities that allow them to achieve better performance or superior profitability (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002; Sadikog

Zehir, 2010). Innovation is critical to achieve operationalefficiency aswell as raising service quality (Hsueh & Tu, 2004;

Parasuraman,2010). Accordingly,scholars paid more attention to the effects on firm performance (Clifton,Keast,Pickernell,&

Senior, 2010;Jenny, 2005; Liao, Wang, Chuang, Shih, & Liu, 2010; Vaccaro et al., 2010).

As time-based competition has become an important concern for contemporary business organizations,more firms recognized

that quick response of their competitors to new product development is posing a critical competitive threat. Therefore, they att

to introduce new products, services, or processes more quickly (Boyd & Bresser, 2008; Smith, 2011). Robinson (1990) demonst

that over a broad cross-section of industries, firms that stressed innovation speed could increase their market share. When a fir

faster than its competitors in developing, producing and selling new products, it is able to make market segments in association

service quality and operating efficiency.That is because knowledge contained in these innovations is notreadily available to

competitors (Liao et al., 2010). Therefore, innovation speed guarantees quicker response to environment by launching new pro

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

16

processes positively affect innovation. Therefore, it is fair to conclude that KM process and innovation are closely related. Thus,

posit the followings:

H1. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H2. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H3. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on speed innovation.

H4. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H5. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H6. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quality innovation.

H7. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

H8. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

H9. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on quantity innovation.

3.2. KM Effects on Organizational Performance

Prior conceptualresearch state thatKM can improve corporate performance and competitiveness (Civi,2000; DeTienne &

Jackson, 2001; Holsapple & Jones, 2004, 2005). KM programs are successful as corporate performance is improved. Therefore, i

essentialto measure KM contributions to performance (Tseng,2008),especially when there is no conclusive research on the re-

lationship between the production,Integration,Application of knowledge and firm performance (Yang,2010).Corporate perfor-

mance is a multidimensional concept and accounts for firm's position regarding to competitors. A comprehensive view of corpo

performance not only considers the financial perspective, but also others aspects that allow monitoring value creation. Based o

view some methodologies have been developed. The most popular methodology is the Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1

Some studies recognize the impact of strategic KM on different dimensions of corporate performance (McKeen, Zack, & Singh, 2

Nevertheless,most of them focus on hard financialoutcomes (e.g.cost,profit, etc.) to evaluate KM (Vaccaro,Parente,& Veloso,

2010), while ignoring soft non-financial outcomes such as operating costs, shorten lead-time, and differentiate products (Sher &

2004); developing new services (Storey & Kahn, 2010); improving its ability to attract, train, develop, and retain employee (Tho

& Keithley, 2002); and improving coordination efforts (Wu & Lin, 2009). since diverse dimensions of performance are affected b

strategy, K M system performance should combine financial and nonfinancial measures (Tseng, 2008; Wu & Lin, 2009). We sug

that the impact of KM strategy on firm performance should be better studied by analyzing different dimensions of corporate pe

formance.Three dimensions will be employed to measure KM contributions to corporate performance:(1) financialperformance

including market performance (profitability, growth and customer satisfaction); (2) process performance, which refers to quality

efficiency;and (3) internalperformance,which relates to individualcapabilities (employees'qualification,satisfaction and crea-

tivity). Thus, this study proposes:

H10. The production of knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H11. The Integration of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H12. The Application of Knowledge has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

3.3. Innovation Effects on OrganizationalPerformance

Innovation is recognized as a significant enabler for firms to create value and sustain competitive advantage in the increasin

complex and rapidly changing environment (Bilton & Cummings, 2009; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). In general, innovation n

only makes full use of existing resources,improve efficiency and potential value,but also brings new intangible assets into orga-

nization.Firms with greater innovativeness willbe more successfulin responding to customers'needs,and in developing new

capabilities that allow them to achieve better performance or superior profitability (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002; Sadikog

Zehir, 2010). Innovation is critical to achieve operationalefficiency aswell as raising service quality (Hsueh & Tu, 2004;

Parasuraman,2010). Accordingly,scholars paid more attention to the effects on firm performance (Clifton,Keast,Pickernell,&

Senior, 2010;Jenny, 2005; Liao, Wang, Chuang, Shih, & Liu, 2010; Vaccaro et al., 2010).

As time-based competition has become an important concern for contemporary business organizations,more firms recognized

that quick response of their competitors to new product development is posing a critical competitive threat. Therefore, they att

to introduce new products, services, or processes more quickly (Boyd & Bresser, 2008; Smith, 2011). Robinson (1990) demonst

that over a broad cross-section of industries, firms that stressed innovation speed could increase their market share. When a fir

faster than its competitors in developing, producing and selling new products, it is able to make market segments in association

service quality and operating efficiency.That is because knowledge contained in these innovations is notreadily available to

competitors (Liao et al., 2010). Therefore, innovation speed guarantees quicker response to environment by launching new pro

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

16

with lower times and costs,which eventually improves firm performance (Tidd,Bessant,& Pavitt, 2005).Innovation quality is

another key factor influencing firm performance.A high quality of innovation is adopting numerous new products,processes or

practices across a broad cross-section of organizational activities. It requires firms to create synergies among these multiple ac

domains.Such synergies should be created in a way that is inimitable,encourages newness and contributes to competitiveness.

Organizations benefit from increased ideas. Innovative R&D would be more effective in achieving firm performance goals (Bren

2001; Singh, 2008).

Quantity innovation which is defined as the number of new or improved products, services and process launched to the mar

superior to the average in your industry. In fact, knowledge contributes to producing creative thoughts and generating innovati

(Borghini,2005).That is why innovation is seen as the area of greatest payoff from KM (Majchrzak et al.,2004).Although the

relationships between innovation and firm performance have been discussed,few researches consider the specific effects ofin-

novation speed, quality, and quality on firm's performance. So this paper proposes the hypotheses as follow:

H13. Speed innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H14. Quality innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H15. Quantity innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Construct operationalization

To test the research model,a survey was conducted by companies that are members of Iranian Power Syndicate.A structured

questionnaire consisting of close-ended questions was developed. Pretest for the instrument was examined by 6 practitioners (

senior managers, senior experts of five companies), and 5 academics. The questionnaire was localized for Iran. The seven-point

scale ranging from “1” (totally disagree) to “7” (totally agree) was employed in the questionnaire.The question items for the

constructs are listed in Appendix A.

The variables of this research are measured using multi-item scales, tested in previous studies. The producing of knowledge

is based on Fong and Choi (2009). A range of studies (Fong & Choi, 2009) were used to determine the item scale of the knowled

integration. The Application of Knowledge is measured based on Fong and Choi (2009). Innovation speed was measured using fi

items reflecting firm quickness to generate novel ideas, new product launching, new product development, new processes, and

problem solving compared to key competitors.A few studies used similar measures to operationalizefirm's response speed to

competitive actions (Chen & Hambrick, 1995; Liao et al., 2010). The measurement of innovation quality was developed from Ha

(2002) and Lahiri (2010). Five items reflect the newness and creativity of new ideas, products, processes, practices, and manag

of certain company. Quality Innovation scale is based on Lee and Choi (2003). Finally, performance measures are based on Qui

Rohrbaugh (1983), Hoque and James (2000), and Choi and Lee (2002, 2003).

4.2. Data Collection

This study examined a sample of 120 firms that are the members of Iranian Power Syndicate.These firms varied in size and

industry.The sample has several advantages.First, production,integration,and application of Knowledge in knowledge intensive

firms plays a crucial role in facilitating innovation (e.g. designing new products or services in this highly competitive arena). Sec

today's dynamic economy depends on the developmentof innovation.This property makes firms to examine the link between

innovation and performance. Data were collected from CEO, senior manager, expert, and senior expert as the key informant du

their knowledge of the firm,access to strategic information,and familiarity with the environment.Informants were promised to

obtain a summary of the results if they were interested in this study. 226 questionnaire were collected.

5. Results

5.1. Results of reliability and validity

Using SPSS and PLS,we conducted a StructuralEquation Model(SEM) to evaluate the overallmeasurement model,and per

construct. Measurement model shows high reliability and validity of the scales (Table 1). Concerning reliability, Cronbach's alph

Eigen value and Dillon-Goldstein's Rho are above 0.7 level recommended by the literature (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 20

To evaluate the validity of measurement model, convergent validity and discriminant validity were assessed. Convergent validi

the degree to which, factors that are supposed to measure a single construct, confirm each other. We tested convergent validit

recommended by other studies. Except the Integration of Knowledge (which was 0.42), the average variance extracted is above

the minimum value proposed by Fornelland Larcker (1981).As it is seen in Table 1,the results show that our modelmeets the

convergent validity criteria.

Discriminant validity is the degree to which, factors that are supposed to measure a specific construct do not predict concep

unrelated criteria (Kline, 2010). We used Fornell and Larcker's approach to assess discriminant validity. In this approach, the AV

per construct should be higher than the squared correlation between the construct, and any of the other constructs. Table 1 ind

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

17

another key factor influencing firm performance.A high quality of innovation is adopting numerous new products,processes or

practices across a broad cross-section of organizational activities. It requires firms to create synergies among these multiple ac

domains.Such synergies should be created in a way that is inimitable,encourages newness and contributes to competitiveness.

Organizations benefit from increased ideas. Innovative R&D would be more effective in achieving firm performance goals (Bren

2001; Singh, 2008).

Quantity innovation which is defined as the number of new or improved products, services and process launched to the mar

superior to the average in your industry. In fact, knowledge contributes to producing creative thoughts and generating innovati

(Borghini,2005).That is why innovation is seen as the area of greatest payoff from KM (Majchrzak et al.,2004).Although the

relationships between innovation and firm performance have been discussed,few researches consider the specific effects ofin-

novation speed, quality, and quality on firm's performance. So this paper proposes the hypotheses as follow:

H13. Speed innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H14. Quality innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

H15. Quantity innovation has a direct and significant effect on organizational performance.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Construct operationalization

To test the research model,a survey was conducted by companies that are members of Iranian Power Syndicate.A structured

questionnaire consisting of close-ended questions was developed. Pretest for the instrument was examined by 6 practitioners (

senior managers, senior experts of five companies), and 5 academics. The questionnaire was localized for Iran. The seven-point

scale ranging from “1” (totally disagree) to “7” (totally agree) was employed in the questionnaire.The question items for the

constructs are listed in Appendix A.

The variables of this research are measured using multi-item scales, tested in previous studies. The producing of knowledge

is based on Fong and Choi (2009). A range of studies (Fong & Choi, 2009) were used to determine the item scale of the knowled

integration. The Application of Knowledge is measured based on Fong and Choi (2009). Innovation speed was measured using fi

items reflecting firm quickness to generate novel ideas, new product launching, new product development, new processes, and

problem solving compared to key competitors.A few studies used similar measures to operationalizefirm's response speed to

competitive actions (Chen & Hambrick, 1995; Liao et al., 2010). The measurement of innovation quality was developed from Ha

(2002) and Lahiri (2010). Five items reflect the newness and creativity of new ideas, products, processes, practices, and manag

of certain company. Quality Innovation scale is based on Lee and Choi (2003). Finally, performance measures are based on Qui

Rohrbaugh (1983), Hoque and James (2000), and Choi and Lee (2002, 2003).

4.2. Data Collection

This study examined a sample of 120 firms that are the members of Iranian Power Syndicate.These firms varied in size and

industry.The sample has several advantages.First, production,integration,and application of Knowledge in knowledge intensive

firms plays a crucial role in facilitating innovation (e.g. designing new products or services in this highly competitive arena). Sec

today's dynamic economy depends on the developmentof innovation.This property makes firms to examine the link between

innovation and performance. Data were collected from CEO, senior manager, expert, and senior expert as the key informant du

their knowledge of the firm,access to strategic information,and familiarity with the environment.Informants were promised to

obtain a summary of the results if they were interested in this study. 226 questionnaire were collected.

5. Results

5.1. Results of reliability and validity

Using SPSS and PLS,we conducted a StructuralEquation Model(SEM) to evaluate the overallmeasurement model,and per

construct. Measurement model shows high reliability and validity of the scales (Table 1). Concerning reliability, Cronbach's alph

Eigen value and Dillon-Goldstein's Rho are above 0.7 level recommended by the literature (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 20

To evaluate the validity of measurement model, convergent validity and discriminant validity were assessed. Convergent validi

the degree to which, factors that are supposed to measure a single construct, confirm each other. We tested convergent validit

recommended by other studies. Except the Integration of Knowledge (which was 0.42), the average variance extracted is above

the minimum value proposed by Fornelland Larcker (1981).As it is seen in Table 1,the results show that our modelmeets the

convergent validity criteria.

Discriminant validity is the degree to which, factors that are supposed to measure a specific construct do not predict concep

unrelated criteria (Kline, 2010). We used Fornell and Larcker's approach to assess discriminant validity. In this approach, the AV

per construct should be higher than the squared correlation between the construct, and any of the other constructs. Table 1 ind

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

17

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

that the measurement model has satisfactory discriminant validity.

5.2. The evaluation of structural model

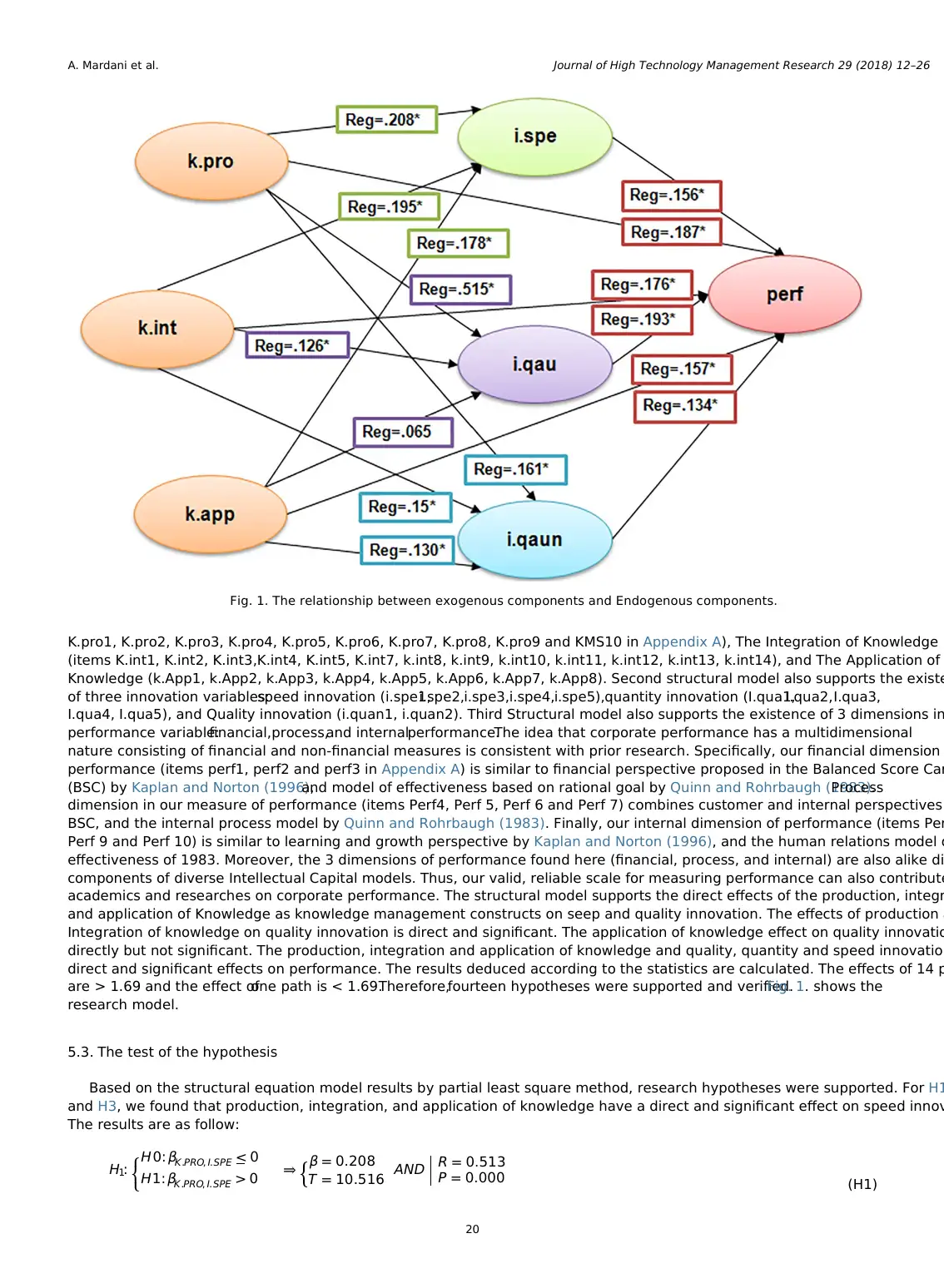

Structural model (Table 2) supports the existence of Knowledge Management Dimensions: The production of knowledge (ite

Table 1

The results of reliability and validity basis on the scale measure the constructs in the conceptual model.

Critical ratio (CR) Standard error loadings perf i.qaun i.qau i.spe k.app k.int k.pro variables Constructs

13.191 0.048 0.634 0.452 0.324 0.448 0.285 0.529 0.529 0.634 k.pro1 Production of

knowledge15.098 0.042 0.636 0.470 0.307 0.490 0.364 0.369 0.453 0.636 k.pro2

16.331 0.043 0.699 0.500 0.228 0.401 0.414 0.471 0.592 0.699 k.pro3

11.288 0.057 0.645 0.433 0.131 0.372 0.304 0.437 0.452 0.645 k.pro4

22.280 0.035 0.788 0.546 0.297 0.490 0.378 0.510 0.557 0.788 k.pro5

21.683 0.035 0.754 0.566 0.293 0.486 0.396 0.446 0.519 0.754 k.pro6

24.054 0.031 0.752 0.523 0.240 0.474 0.376 0.516 0.530 0.752 k.pro7

29.813 0.028 0.825 0.552 0.284 0.527 0.414 0.554 0.592 0.825 k.pro8

19.931 0.039 0.768 0.545 0.390 0.562 0.437 0.533 0.589 0.768 k.pro9

16.776 0.042 0.705 0.478 0.272 0.410 0.286 0.494 0.577 0.705 k.pro10

9.830 0.064 0.626 0.428 0.180 0.361 0.276 0.516 0.626 0.562 k.int1 Integration of

Knowledge8.575 0.067 0.576 0.382 0.291 0.361 0.301 0.370 0.576 0.431 k.int2

9.246 0.066 0.610 0.321 0.239 0.279 0.201 0.498 0.610 0.357 k.int3

10.700 0.053 0.568 0.378 0.186 0.266 0.258 0.376 0.568 0.376 k.int4

9.785 0.063 0.612 0.472 0.199 0.314 0.231 0.469 0.612 0.468 k.int5

9.229 0.061 0.560 0.399 0.154 0.290 0.261 0.459 0.560 0.496 k.int6

15.855 0.046 0.737 0.531 0.281 0.506 0.486 0.564 0.737 0.639 k.int7

16.138 0.042 0.683 0.448 0.332 0.373 0.294 0.554 0.683 0.459 k.int8

10.128 0.059 0.597 0.258 0.235 0.236 0.176 0.486 0.597 0.346 k.int9

17.054 0.040 0.679 0.399 0.216 0.301 0.268 0.541 0.679 0.480 k.int10

19.649 0.038 0.742 0.508 0.301 0.426 0.381 0.614 0.742 0.576 k.int11

15.280 0.044 0.666 0.463 0.322 0.391 0.345 0.504 0.666 0.540 k.int12

22.984 0.033 0.760 0.489 0.262 0.418 0.395 0.619 0.760 0.534 k.int13

13.732 0.044 0.610 0.444 0.227 0.384 0.342 0.514 0.610 0.467 k.int14

11.794 0.060 0.709 0.307 0.158 0.231 0.231 0.709 0.543 0.397 k.App1 Application of

Knowledge12.095 0.057 0.691 0.303 0.206 0.266 0.237 0.691 0.506 0.350 k.App2

12.177 0.051 0.624 0.433 0.105 0.379 0.280 0.624 0.504 0.490 k.App3

19.352 0.040 0.774 0.375 0.268 0.331 0.330 0.774 0.639 0.451 k.App4

35.643 0.023 0.828 0.532 0.289 0.455 0.399 0.828 0.648 0.511 k.App5

12.766 0.052 0.659 0.466 0.246 0.345 0.265 0.659 0.516 0.473 k.App6

14.733 0.046 0.680 0.502 0.226 0.464 0.343 0.680 0.612 0.625 k.App7

13.081 0.052 0.675 0.455 0.275 0.480 0.385 0.675 0.485 0.581 k.App8

21.691 0.035 0.767 0.463 0.324 0.576 0.767 0.319 0.365 0.373 i.spe1 Innovation speed

33.936 0.025 0.834 0.507 0.568 0.634 0.834 0.317 0.344 0.390 i.spe2

25.202 0.032 0.798 0.422 0.453 0.572 0.798 0.283 0.321 0.331 i.spe3

22.023 0.035 0.763 0.405 0.358 0.528 0.763 0.385 0.441 0.455 i.spe4

16.407 0.043 0.713 0.464 0.253 0.556 0.713 0.390 0.389 0.429 i.spe5

16.014 0.045 0.721 0.500 0.351 0.721 0.581 0.413 0.407 0.447 I.qua1 Innovation quality

16.127 0.045 0.728 0.452 0.454 0.728 0.600 0.293 0.314 0.400 I.qua2

19.598 0.039 0.758 0.525 0.470 0.758 0.592 0.368 0.382 0.418 I.qua3

19.838 0.038 0.757 0.541 0.384 0.757 0.521 0.398 0.419 0.475 I.qua4

20.103 0.039 0.787 0.647 0.336 0.787 0.524 0.443 0.510 0.628 I.qua5

45.965 0.020 0.925 0.477 0.925 0.458 0.461 0.297 0.348 0.316 i.quan1 Innovation quantity

31.304 0.028 0.885 0.431 0.885 0.484 0.451 0.280 0.353 0.411 i.quan2

22.720 0.032 0.723 0.723 0.444 0.617 0.510 0.406 0.475 0.523 perf1 Performance

14.303 0.047 0.668 0.668 0.319 0.437 0.423 0.334 0.394 0.407 perf2

19.575 0.041 0.804 0.804 0.351 0.546 0.429 0.445 0.476 0.557 perf3

16.692 0.045 0.744 0.744 0.440 0.541 0.472 0.400 0.456 0.512 perf4

17.988 0.038 0.692 0.692 0.308 0.529 0.386 0.461 0.526 0.535 perf5

16.252 0.043 0.703 0.703 0.431 0.494 0.343 0.437 0.495 0.485 perf6

25.253 0.030 0.766 0.766 0.301 0.493 0.423 0.419 0.484 0.538 perf7

17.539 0.041 0.713 0.713 0.266 0.460 0.408 0.500 0.532 0.574 perf8

17.252 0.037 0.639 0.639 0.339 0.481 0.303 0.339 0.348 0.367 perf9

16.456 0.040 0.662 0.662 0.437 0.593 0.450 0.456 0.498 0.457 perf10

The results (AVE) are > 0.50, except the integration of

knowledge which is 0.42

0.508 0.820 0.563 0.602 0.501 0.420 0.523 Convergent validity

The results (AVE) are more than the correlation coefficients

between constructs

0.713 0.906 0.750 0.776 0.708 0.648 0.723 Discriminant validity

Results are > 0.70 0.892 0.779 0.809 0.834 0.856 0.893 0.896 Cronbach's alpha

Results are > 0.70 0.913 0.903 0.868 0.884 0.891 0.911 0.915 Dillon-Goldstein's Rho

Bold indicates high numbers of discriminant validity.

A. Mardani et al. Journal of High Technology Management Research 29 (2018) 12–26

18

5.2. The evaluation of structural model

Structural model (Table 2) supports the existence of Knowledge Management Dimensions: The production of knowledge (ite

Table 1

The results of reliability and validity basis on the scale measure the constructs in the conceptual model.

Critical ratio (CR) Standard error loadings perf i.qaun i.qau i.spe k.app k.int k.pro variables Constructs

13.191 0.048 0.634 0.452 0.324 0.448 0.285 0.529 0.529 0.634 k.pro1 Production of

knowledge15.098 0.042 0.636 0.470 0.307 0.490 0.364 0.369 0.453 0.636 k.pro2

16.331 0.043 0.699 0.500 0.228 0.401 0.414 0.471 0.592 0.699 k.pro3

11.288 0.057 0.645 0.433 0.131 0.372 0.304 0.437 0.452 0.645 k.pro4

22.280 0.035 0.788 0.546 0.297 0.490 0.378 0.510 0.557 0.788 k.pro5

21.683 0.035 0.754 0.566 0.293 0.486 0.396 0.446 0.519 0.754 k.pro6

24.054 0.031 0.752 0.523 0.240 0.474 0.376 0.516 0.530 0.752 k.pro7

29.813 0.028 0.825 0.552 0.284 0.527 0.414 0.554 0.592 0.825 k.pro8

19.931 0.039 0.768 0.545 0.390 0.562 0.437 0.533 0.589 0.768 k.pro9

16.776 0.042 0.705 0.478 0.272 0.410 0.286 0.494 0.577 0.705 k.pro10

9.830 0.064 0.626 0.428 0.180 0.361 0.276 0.516 0.626 0.562 k.int1 Integration of

Knowledge8.575 0.067 0.576 0.382 0.291 0.361 0.301 0.370 0.576 0.431 k.int2

9.246 0.066 0.610 0.321 0.239 0.279 0.201 0.498 0.610 0.357 k.int3

10.700 0.053 0.568 0.378 0.186 0.266 0.258 0.376 0.568 0.376 k.int4

9.785 0.063 0.612 0.472 0.199 0.314 0.231 0.469 0.612 0.468 k.int5

9.229 0.061 0.560 0.399 0.154 0.290 0.261 0.459 0.560 0.496 k.int6

15.855 0.046 0.737 0.531 0.281 0.506 0.486 0.564 0.737 0.639 k.int7

16.138 0.042 0.683 0.448 0.332 0.373 0.294 0.554 0.683 0.459 k.int8

10.128 0.059 0.597 0.258 0.235 0.236 0.176 0.486 0.597 0.346 k.int9

17.054 0.040 0.679 0.399 0.216 0.301 0.268 0.541 0.679 0.480 k.int10

19.649 0.038 0.742 0.508 0.301 0.426 0.381 0.614 0.742 0.576 k.int11

15.280 0.044 0.666 0.463 0.322 0.391 0.345 0.504 0.666 0.540 k.int12

22.984 0.033 0.760 0.489 0.262 0.418 0.395 0.619 0.760 0.534 k.int13

13.732 0.044 0.610 0.444 0.227 0.384 0.342 0.514 0.610 0.467 k.int14

11.794 0.060 0.709 0.307 0.158 0.231 0.231 0.709 0.543 0.397 k.App1 Application of

Knowledge12.095 0.057 0.691 0.303 0.206 0.266 0.237 0.691 0.506 0.350 k.App2