Knowledge Management, Social Networks, and Innovation: A Deep Dive

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/18

|11

|4910

|38

Essay

AI Summary

This essay delves into the critical interplay between knowledge management (KM), organizational learning (OL), social networks, and innovation within the business context. It begins by establishing the importance of KM and OL for achieving competitive advantage, particularly in today's knowledge economy. The essay then reviews the relevant literature on OL and KM, exploring how social media (SM) and web 2.0 technologies are reshaping the landscape and influencing innovation. An integrated KM framework is proposed and subsequently applied to analyze ConocoPhillips' KM strategy, assessing how social technologies have been utilized to foster knowledge sharing and drive innovation within the organization. The analysis highlights ConocoPhillips' successful implementation of KM practices, emphasizing the significance of collaboration, trust, and the use of platforms like OneWiki to capture, store, and reuse intellectual capital. The essay concludes by summarizing the key findings and implications of KM, social networks, and innovation for organizational success.

Knowledge Management, Social Networks and Innovation

Introduction

Knowledge management (KM) and organisational learning (OL) are two key factors for an

organisation to gain competitive advantage (Plessis, 2007; King et al., 2002; Lesser, 2000; Davenport

and Prusak, 1998; Foss and Pedersen, 2002; Grant, 1996; Spender and Grant, 1996) and drive

innovation. Drucker (1993) noted the rise of the knowledge worker, business value was being

transformed from purely tangible assets, such as goods and services, to include intangible assets

related to ideas and application of information, and resulted in the emergence of the knowledge

economy which is crucial to nurturing innovation (Ahmed and Shepherd, 2010). Fostering efficient

processes for KM and establishing a culture that encourages OL has become a means of competitive

advantage and value for organisations. Given today’s economic climate and an aging population, this

has never before been so critical to the success of an organisation.

This essay will outline the literature on OL and KM and look at how social media (SM) and web 2.0

technologies are influencing the OL and KM landscape, and attempt to address this in the context of

innovation. Section two will put forward an integrated framework for KM, which will be used later to

determine the success of ConocoPhillips’ KM strategy. Section three will evaluate OL, KM and

innovation in the context of ConocoPhillips and assess how social technologies have been used.

Section four will cover the conclusion.

Literature Review

Organisational learning

Learning is a process that involves the application of experience and repetition to transform

processes, tasks or products (Teece, 2007). Experience happens over time and in order to apply it,

available data must be converted into information that is accessible; it is then - through the

application of information - that knowledge is created or acquired (Ackoff, 1989). Thus, OL is a

process that involves knowledge acquisition (or creation), information distribution (or transfer),

information interpretation and organisational memory (Huber, 1991; Dixon, 1992; Slater and Narver,

1995; Goh, 2002). A number of disciplines discuss OL (Easterby-Smith, 1997) and no single framework

or universally accepted definition exists within the literature. However, it is widely agreed that OL

forms the basis for an organisation to develop new knowledge and gain insight from internal and

external experiences or information that has the potential to change behaviour leading to innovation

and increased competitive advantage (Huber, 1991; Senge, 1992; Davenport and Prusak, 1998;

Sørensen and Stuart, 2000; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Slater and Narver, 1995). Through the

learning process and subsequently OL, experience, shared interpretation and collaboration play a

crucial role in enabling organisations to exploit knowledge in order to remain flexible and responsive

to change.

Organisations that are more flexible can react faster to internal changes and external challenges. Hult

et al. (2004) conclude that an organisation’s capacity to innovate and produce solutions to its

business problems correlates with an organisation’s ability to grow and to survive in times of market

turbulence (Tippins and Sohi, 2003; Day, 1994). Brown and Eisenhard (1995) suggest that

Introduction

Knowledge management (KM) and organisational learning (OL) are two key factors for an

organisation to gain competitive advantage (Plessis, 2007; King et al., 2002; Lesser, 2000; Davenport

and Prusak, 1998; Foss and Pedersen, 2002; Grant, 1996; Spender and Grant, 1996) and drive

innovation. Drucker (1993) noted the rise of the knowledge worker, business value was being

transformed from purely tangible assets, such as goods and services, to include intangible assets

related to ideas and application of information, and resulted in the emergence of the knowledge

economy which is crucial to nurturing innovation (Ahmed and Shepherd, 2010). Fostering efficient

processes for KM and establishing a culture that encourages OL has become a means of competitive

advantage and value for organisations. Given today’s economic climate and an aging population, this

has never before been so critical to the success of an organisation.

This essay will outline the literature on OL and KM and look at how social media (SM) and web 2.0

technologies are influencing the OL and KM landscape, and attempt to address this in the context of

innovation. Section two will put forward an integrated framework for KM, which will be used later to

determine the success of ConocoPhillips’ KM strategy. Section three will evaluate OL, KM and

innovation in the context of ConocoPhillips and assess how social technologies have been used.

Section four will cover the conclusion.

Literature Review

Organisational learning

Learning is a process that involves the application of experience and repetition to transform

processes, tasks or products (Teece, 2007). Experience happens over time and in order to apply it,

available data must be converted into information that is accessible; it is then - through the

application of information - that knowledge is created or acquired (Ackoff, 1989). Thus, OL is a

process that involves knowledge acquisition (or creation), information distribution (or transfer),

information interpretation and organisational memory (Huber, 1991; Dixon, 1992; Slater and Narver,

1995; Goh, 2002). A number of disciplines discuss OL (Easterby-Smith, 1997) and no single framework

or universally accepted definition exists within the literature. However, it is widely agreed that OL

forms the basis for an organisation to develop new knowledge and gain insight from internal and

external experiences or information that has the potential to change behaviour leading to innovation

and increased competitive advantage (Huber, 1991; Senge, 1992; Davenport and Prusak, 1998;

Sørensen and Stuart, 2000; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Slater and Narver, 1995). Through the

learning process and subsequently OL, experience, shared interpretation and collaboration play a

crucial role in enabling organisations to exploit knowledge in order to remain flexible and responsive

to change.

Organisations that are more flexible can react faster to internal changes and external challenges. Hult

et al. (2004) conclude that an organisation’s capacity to innovate and produce solutions to its

business problems correlates with an organisation’s ability to grow and to survive in times of market

turbulence (Tippins and Sohi, 2003; Day, 1994). Brown and Eisenhard (1995) suggest that

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

organisations with innovative capacity can exploit new products and market opportunities better

than non-innovative organisations. The literature argues that to innovate within an organisation,

knowledge must be shared (Sørensen and Stuart, 2000; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Hall and

Andriani, 2003). Together this implies that OL leads to developing capabilities that support

innovation (Hurley and Hult, 1998) through knowledge creation and sharing or effective KM, which

can result in learning organisations maintaining an advantage over those that either do not learn or

do not learn as well. KM is, therefore, a major component in supporting OL in realising an

organisation’s innovation potential.

Knowledge Management

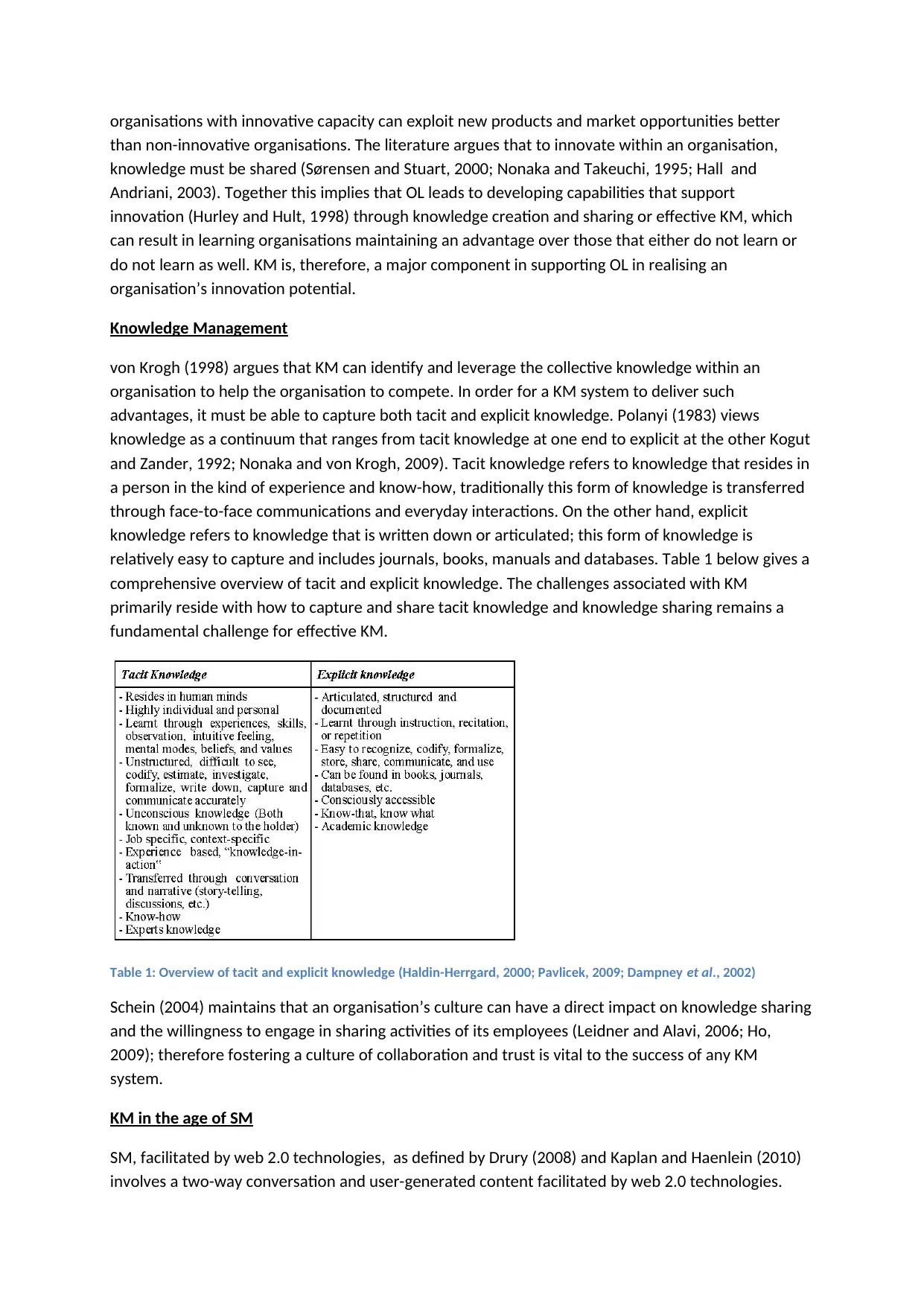

von Krogh (1998) argues that KM can identify and leverage the collective knowledge within an

organisation to help the organisation to compete. In order for a KM system to deliver such

advantages, it must be able to capture both tacit and explicit knowledge. Polanyi (1983) views

knowledge as a continuum that ranges from tacit knowledge at one end to explicit at the other Kogut

and Zander, 1992; Nonaka and von Krogh, 2009). Tacit knowledge refers to knowledge that resides in

a person in the kind of experience and know-how, traditionally this form of knowledge is transferred

through face-to-face communications and everyday interactions. On the other hand, explicit

knowledge refers to knowledge that is written down or articulated; this form of knowledge is

relatively easy to capture and includes journals, books, manuals and databases. Table 1 below gives a

comprehensive overview of tacit and explicit knowledge. The challenges associated with KM

primarily reside with how to capture and share tacit knowledge and knowledge sharing remains a

fundamental challenge for effective KM.

Table 1: Overview of tacit and explicit knowledge (Haldin-Herrgard, 2000; Pavlicek, 2009; Dampney et al., 2002)

Schein (2004) maintains that an organisation’s culture can have a direct impact on knowledge sharing

and the willingness to engage in sharing activities of its employees (Leidner and Alavi, 2006; Ho,

2009); therefore fostering a culture of collaboration and trust is vital to the success of any KM

system.

KM in the age of SM

SM, facilitated by web 2.0 technologies, as defined by Drury (2008) and Kaplan and Haenlein (2010)

involves a two-way conversation and user-generated content facilitated by web 2.0 technologies.

than non-innovative organisations. The literature argues that to innovate within an organisation,

knowledge must be shared (Sørensen and Stuart, 2000; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Hall and

Andriani, 2003). Together this implies that OL leads to developing capabilities that support

innovation (Hurley and Hult, 1998) through knowledge creation and sharing or effective KM, which

can result in learning organisations maintaining an advantage over those that either do not learn or

do not learn as well. KM is, therefore, a major component in supporting OL in realising an

organisation’s innovation potential.

Knowledge Management

von Krogh (1998) argues that KM can identify and leverage the collective knowledge within an

organisation to help the organisation to compete. In order for a KM system to deliver such

advantages, it must be able to capture both tacit and explicit knowledge. Polanyi (1983) views

knowledge as a continuum that ranges from tacit knowledge at one end to explicit at the other Kogut

and Zander, 1992; Nonaka and von Krogh, 2009). Tacit knowledge refers to knowledge that resides in

a person in the kind of experience and know-how, traditionally this form of knowledge is transferred

through face-to-face communications and everyday interactions. On the other hand, explicit

knowledge refers to knowledge that is written down or articulated; this form of knowledge is

relatively easy to capture and includes journals, books, manuals and databases. Table 1 below gives a

comprehensive overview of tacit and explicit knowledge. The challenges associated with KM

primarily reside with how to capture and share tacit knowledge and knowledge sharing remains a

fundamental challenge for effective KM.

Table 1: Overview of tacit and explicit knowledge (Haldin-Herrgard, 2000; Pavlicek, 2009; Dampney et al., 2002)

Schein (2004) maintains that an organisation’s culture can have a direct impact on knowledge sharing

and the willingness to engage in sharing activities of its employees (Leidner and Alavi, 2006; Ho,

2009); therefore fostering a culture of collaboration and trust is vital to the success of any KM

system.

KM in the age of SM

SM, facilitated by web 2.0 technologies, as defined by Drury (2008) and Kaplan and Haenlein (2010)

involves a two-way conversation and user-generated content facilitated by web 2.0 technologies.

Examples include Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Youtube (boyd and Ellison, 2008). SM’s

contributions to innovation have been recognised in the literature (O’Mahony and Ferraro, 2007; von

Hippel and von Krogh, 2003) and it can be seen to represent the evolution of IT systems to handle

tacit knowledge sharing in a two-way dynamic setting (Steininger et al., 2010).

As tacit knowledge sharing occurs primarily through social interaction (Yang and Farn, 2009; Haldin-

Herrgard, 2000; Smith, 2001), and SM does not detract from social interactions in the way other IT

systems do as it provides a suitable substitute for face-to-face communication without significant loss

of knowledge sharing and exchange, there are already reasons to believe that these platforms will

have a positive effect on KM (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Bock et al., 2005; Chow and Chan, 2008; Levy,

2009; Razmerita et al., 2009). This suggests that SM could complement traditional KM leading to the

capture and exploitation of tacit knowledge through social interaction using digital platforms, which

will allow that knowledge to be searchable and persist over time.

Research has shown that weak ties are likely to lead to a greater source of innovation than strong

ties (Hauser et al., 2007) and sites such as Facebook allow users to maintain a larger set of weak ties

(Ellison, et al., 2010) than non-Facebook users. The spaces between ties are called network holes

and are typically bridged by these weak ties and allow social capital to increase (Burt, 2004).This

implies that if an organisation implements a similar network across a global corporation, knowledge

sharing from more distant ties that work in geographically different locations or other divisions can

act as network holes and provide access to previously unknown information. By acting as network

holes, these employees can contribute more to the innovation process than those employees that

work in close cooperation to one another and knowledge can flow through the organisation without

traditional structural constraints.

contributions to innovation have been recognised in the literature (O’Mahony and Ferraro, 2007; von

Hippel and von Krogh, 2003) and it can be seen to represent the evolution of IT systems to handle

tacit knowledge sharing in a two-way dynamic setting (Steininger et al., 2010).

As tacit knowledge sharing occurs primarily through social interaction (Yang and Farn, 2009; Haldin-

Herrgard, 2000; Smith, 2001), and SM does not detract from social interactions in the way other IT

systems do as it provides a suitable substitute for face-to-face communication without significant loss

of knowledge sharing and exchange, there are already reasons to believe that these platforms will

have a positive effect on KM (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Bock et al., 2005; Chow and Chan, 2008; Levy,

2009; Razmerita et al., 2009). This suggests that SM could complement traditional KM leading to the

capture and exploitation of tacit knowledge through social interaction using digital platforms, which

will allow that knowledge to be searchable and persist over time.

Research has shown that weak ties are likely to lead to a greater source of innovation than strong

ties (Hauser et al., 2007) and sites such as Facebook allow users to maintain a larger set of weak ties

(Ellison, et al., 2010) than non-Facebook users. The spaces between ties are called network holes

and are typically bridged by these weak ties and allow social capital to increase (Burt, 2004).This

implies that if an organisation implements a similar network across a global corporation, knowledge

sharing from more distant ties that work in geographically different locations or other divisions can

act as network holes and provide access to previously unknown information. By acting as network

holes, these employees can contribute more to the innovation process than those employees that

work in close cooperation to one another and knowledge can flow through the organisation without

traditional structural constraints.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

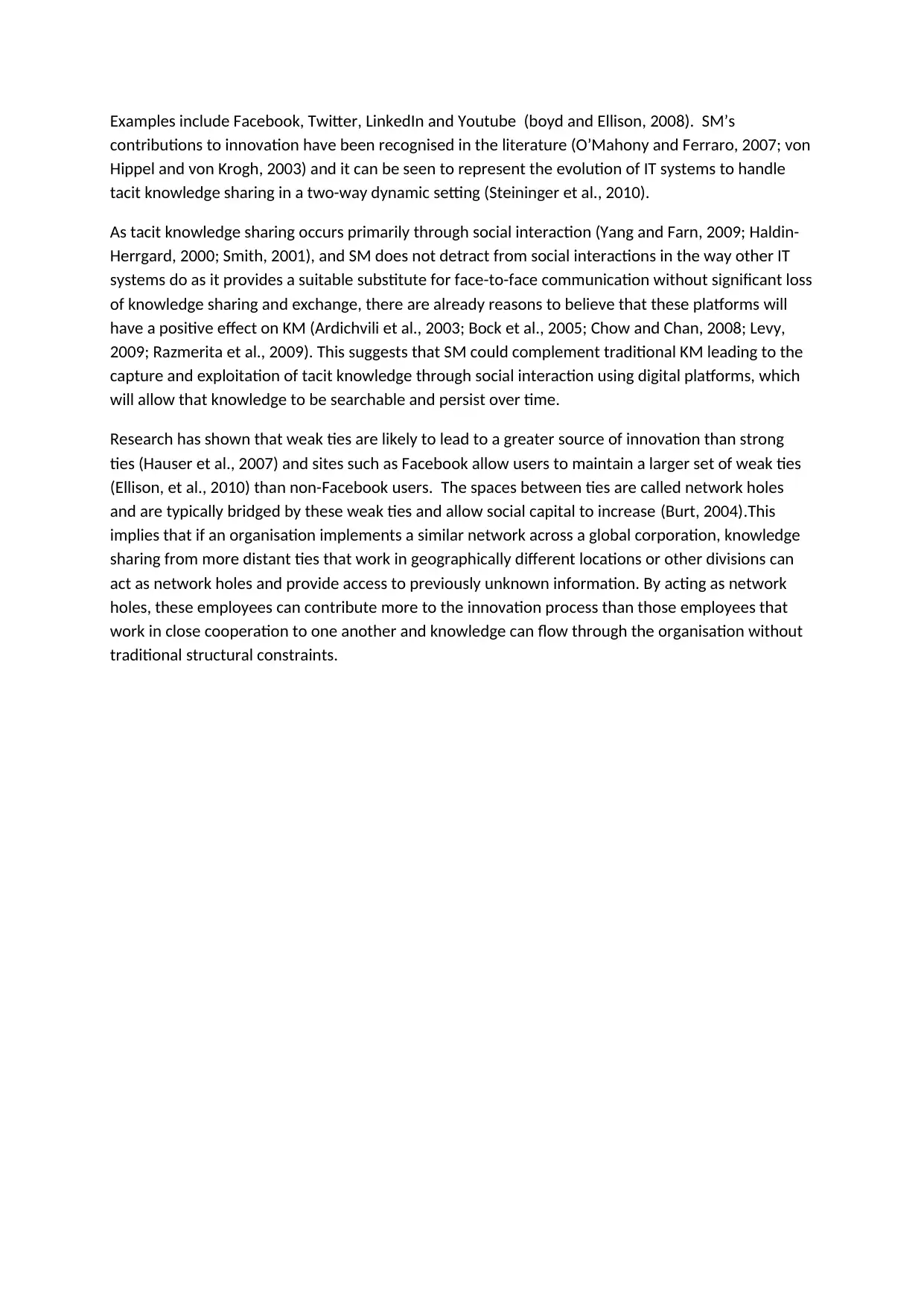

KM model

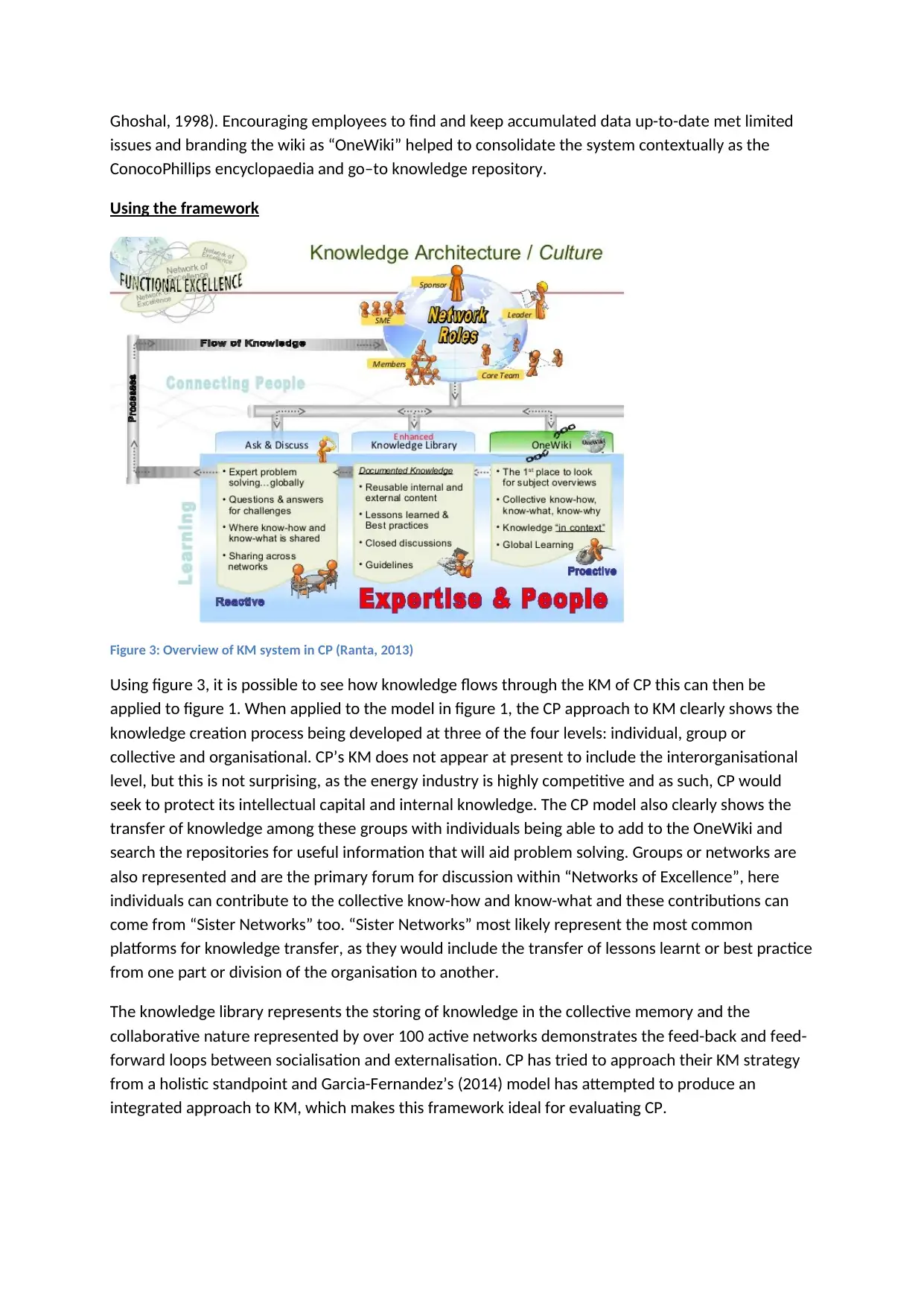

Figure 1: Integrated Knowledge Management model proposed by Garcia-Fernandez (2015)

Figure 1 denotes an integrated approach to knowledge management proposed by Garcia-Fernandez

(2015). The model builds on previous literature that covered the concepts of knowledge creation

(Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Crossan et al., 1999), Knowledge transfer and storage (Nonaka and

Takeuchi, 1995) and the application and use of knowledge (Senge, 1992). The previous models all

offer different perspectives on KM but also have their limitations. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995)

develop knowledge from the viewpoint of creation but do not provide any application, Crossan et al.

(1999) demonstrate knowledge flow through their model but neither offer application or

measurability and Senge (1992) suggests an application but is unable to elucidate where knowledge

actually comes from or how it might be measured when applied to an organisation (Garcia-

Fernandez, 2015). This model attempts to integrate the previous literature into a comprehensive

framework that can be engaged and provide insight to knowledge creation, flow and application that

is measurable.

KM at ConocoPhillips

ConocoPhillips (CP) has taken a holistic approach to KM and has embedded a knowledge sharing

culture throughout the organisations 31,000 strong workforce. CP has been the proud recipient of a

Global Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise (MAKE) award for four consecutive years since 2010. CP

has established an enterprise-wide knowledge sharing team and leverages this across the

organisation to create and encourage the development of consistent processes and technology

enablers for “sister networks” to share common issues and content. CP has fostered a culture of

collaboration and trust towards problem solving, which has been aided by its matrix structure (Riege,

Figure 1: Integrated Knowledge Management model proposed by Garcia-Fernandez (2015)

Figure 1 denotes an integrated approach to knowledge management proposed by Garcia-Fernandez

(2015). The model builds on previous literature that covered the concepts of knowledge creation

(Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Crossan et al., 1999), Knowledge transfer and storage (Nonaka and

Takeuchi, 1995) and the application and use of knowledge (Senge, 1992). The previous models all

offer different perspectives on KM but also have their limitations. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995)

develop knowledge from the viewpoint of creation but do not provide any application, Crossan et al.

(1999) demonstrate knowledge flow through their model but neither offer application or

measurability and Senge (1992) suggests an application but is unable to elucidate where knowledge

actually comes from or how it might be measured when applied to an organisation (Garcia-

Fernandez, 2015). This model attempts to integrate the previous literature into a comprehensive

framework that can be engaged and provide insight to knowledge creation, flow and application that

is measurable.

KM at ConocoPhillips

ConocoPhillips (CP) has taken a holistic approach to KM and has embedded a knowledge sharing

culture throughout the organisations 31,000 strong workforce. CP has been the proud recipient of a

Global Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise (MAKE) award for four consecutive years since 2010. CP

has established an enterprise-wide knowledge sharing team and leverages this across the

organisation to create and encourage the development of consistent processes and technology

enablers for “sister networks” to share common issues and content. CP has fostered a culture of

collaboration and trust towards problem solving, which has been aided by its matrix structure (Riege,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2005). Sponsorship from management and motivating employees through intrinsic benefits has also

encouraged the knowledge-sharing activities within the organisation.

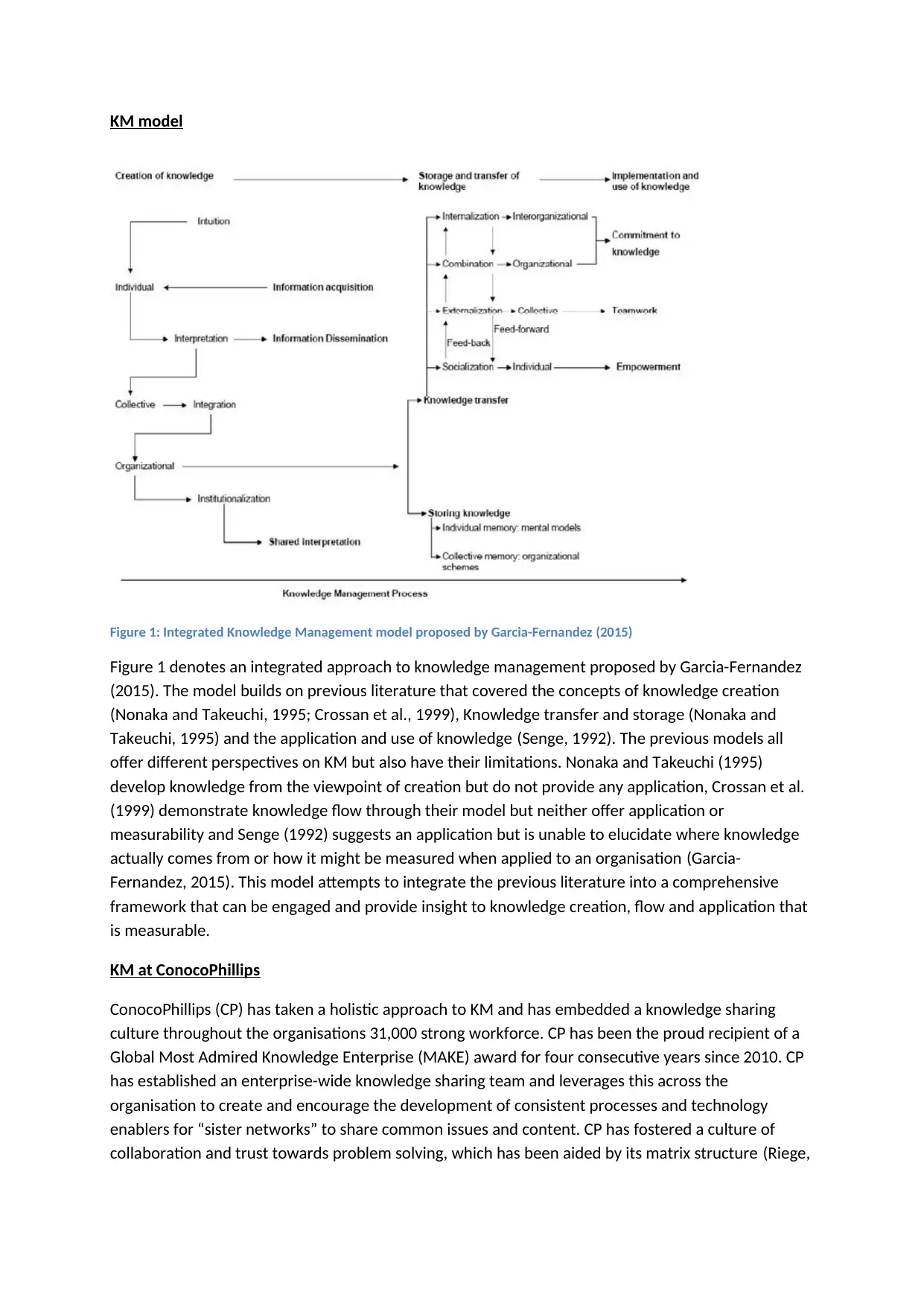

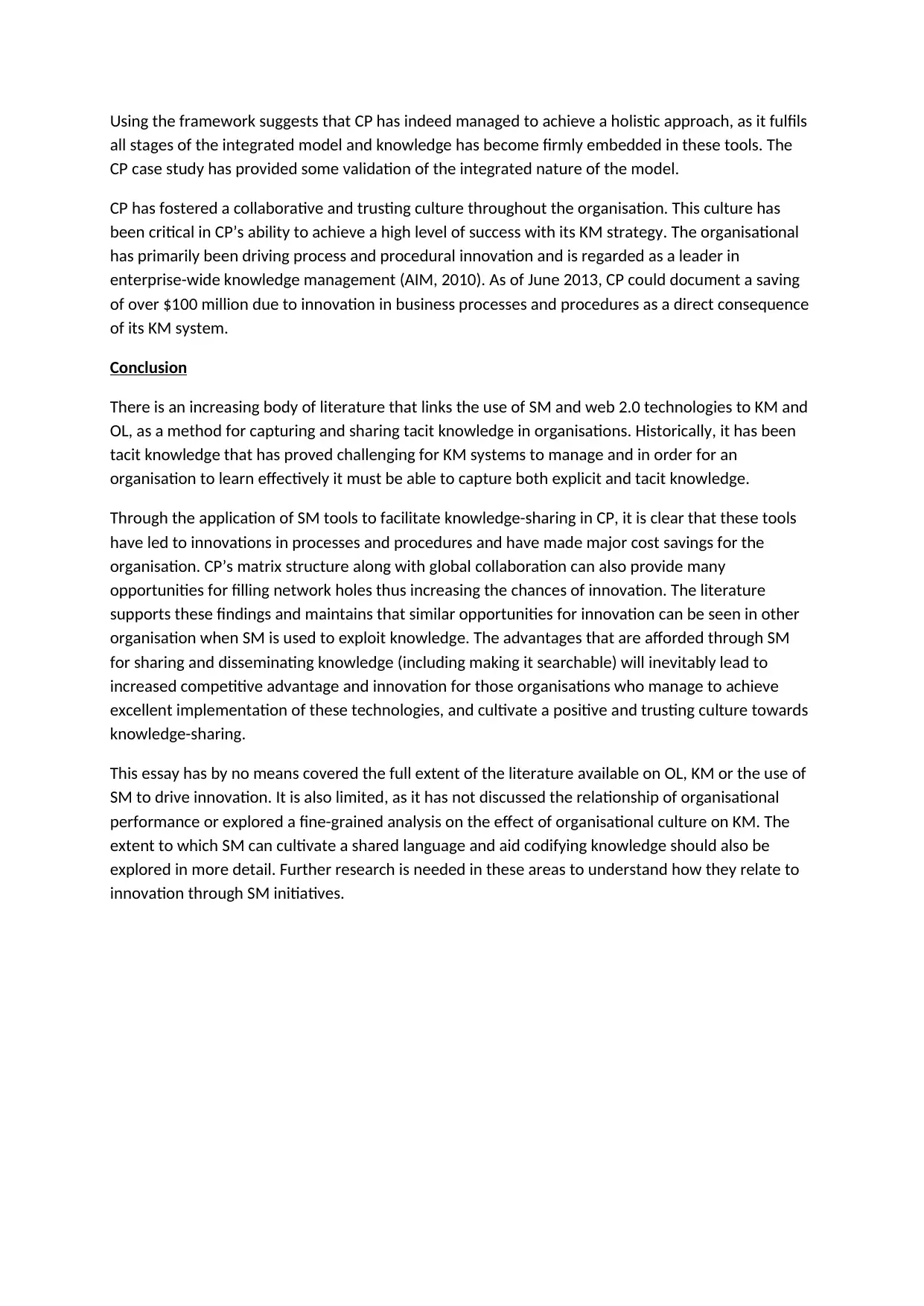

CP’s knowledge management consists of networks of excellence, similar to communities of practice

(Ardichvili et al., 2003) along with a wiki platform that enables proactive knowledge sharing and

problem solving, a knowledge library and an “ask and discuss” forum for more reactive, on the go,

problem solving. As of 2013 the CP community consisted of 105+ enterprise-wide technical expertise

networks of excellence, each with 100 – 800+ members (Ranta, 2013). The organisation could

document over 130,000 instances of peer-to-peer global collaboration from 2006 to 2013, all of

which are key sources of business value. Ranta (2013) explains that the focus has been on knowledge

capture and its re-use to overcome demographic and geographic challenges and has resulted in over

$100 million in documented savings for CP. CP’s approach to developing an effective KM strategy is

outlined in figure 1. It demonstrates how the organisation has differentiated between the formal and

informal processes involved in knowledge sharing to foster a more collaborative culture.

Figure 2: CP's KM strategy approach (Ranta, 2013)

In 2010, CP introduced OneWiki and the ability to close discussion items to its knowledge-sharing

portal. These features leveraged web 2.0 technologies to enhance the knowledge-sharing network.

The “closed discussion” feature allowed knowledge that would otherwise have been lost due to aging

on the network to gain a second lease of life. By officially closing the discussion, the thread is

converted into a lessons learned document, using web 2.0 technology, and transferred over to the

knowledge library where it becomes fully searchable and accessible to others. CP notes that this

approach has created a more fruitful and efficient means of capturing, storing, accessing and reusing

intellectual capital than other more traditional and costly methods (AIM, 2010).

The OneWiki involves many networks, teams and workgroups and provides CP with a natural forum

for capturing insight and wisdom (AIM, 2010). This knowledge is then converted into numerous

searchable lessons learned and best practices within its knowledge library. As the Wiki concept was

already familiar to the majority of employees, the benefits this type of collaborative platform were

already known, so implementation was smooth. By using a wiki, it also stimulated the development

of a common language that helps to increase the likelihood of sharing even more (Nahapiet and

encouraged the knowledge-sharing activities within the organisation.

CP’s knowledge management consists of networks of excellence, similar to communities of practice

(Ardichvili et al., 2003) along with a wiki platform that enables proactive knowledge sharing and

problem solving, a knowledge library and an “ask and discuss” forum for more reactive, on the go,

problem solving. As of 2013 the CP community consisted of 105+ enterprise-wide technical expertise

networks of excellence, each with 100 – 800+ members (Ranta, 2013). The organisation could

document over 130,000 instances of peer-to-peer global collaboration from 2006 to 2013, all of

which are key sources of business value. Ranta (2013) explains that the focus has been on knowledge

capture and its re-use to overcome demographic and geographic challenges and has resulted in over

$100 million in documented savings for CP. CP’s approach to developing an effective KM strategy is

outlined in figure 1. It demonstrates how the organisation has differentiated between the formal and

informal processes involved in knowledge sharing to foster a more collaborative culture.

Figure 2: CP's KM strategy approach (Ranta, 2013)

In 2010, CP introduced OneWiki and the ability to close discussion items to its knowledge-sharing

portal. These features leveraged web 2.0 technologies to enhance the knowledge-sharing network.

The “closed discussion” feature allowed knowledge that would otherwise have been lost due to aging

on the network to gain a second lease of life. By officially closing the discussion, the thread is

converted into a lessons learned document, using web 2.0 technology, and transferred over to the

knowledge library where it becomes fully searchable and accessible to others. CP notes that this

approach has created a more fruitful and efficient means of capturing, storing, accessing and reusing

intellectual capital than other more traditional and costly methods (AIM, 2010).

The OneWiki involves many networks, teams and workgroups and provides CP with a natural forum

for capturing insight and wisdom (AIM, 2010). This knowledge is then converted into numerous

searchable lessons learned and best practices within its knowledge library. As the Wiki concept was

already familiar to the majority of employees, the benefits this type of collaborative platform were

already known, so implementation was smooth. By using a wiki, it also stimulated the development

of a common language that helps to increase the likelihood of sharing even more (Nahapiet and

Ghoshal, 1998). Encouraging employees to find and keep accumulated data up-to-date met limited

issues and branding the wiki as “OneWiki” helped to consolidate the system contextually as the

ConocoPhillips encyclopaedia and go–to knowledge repository.

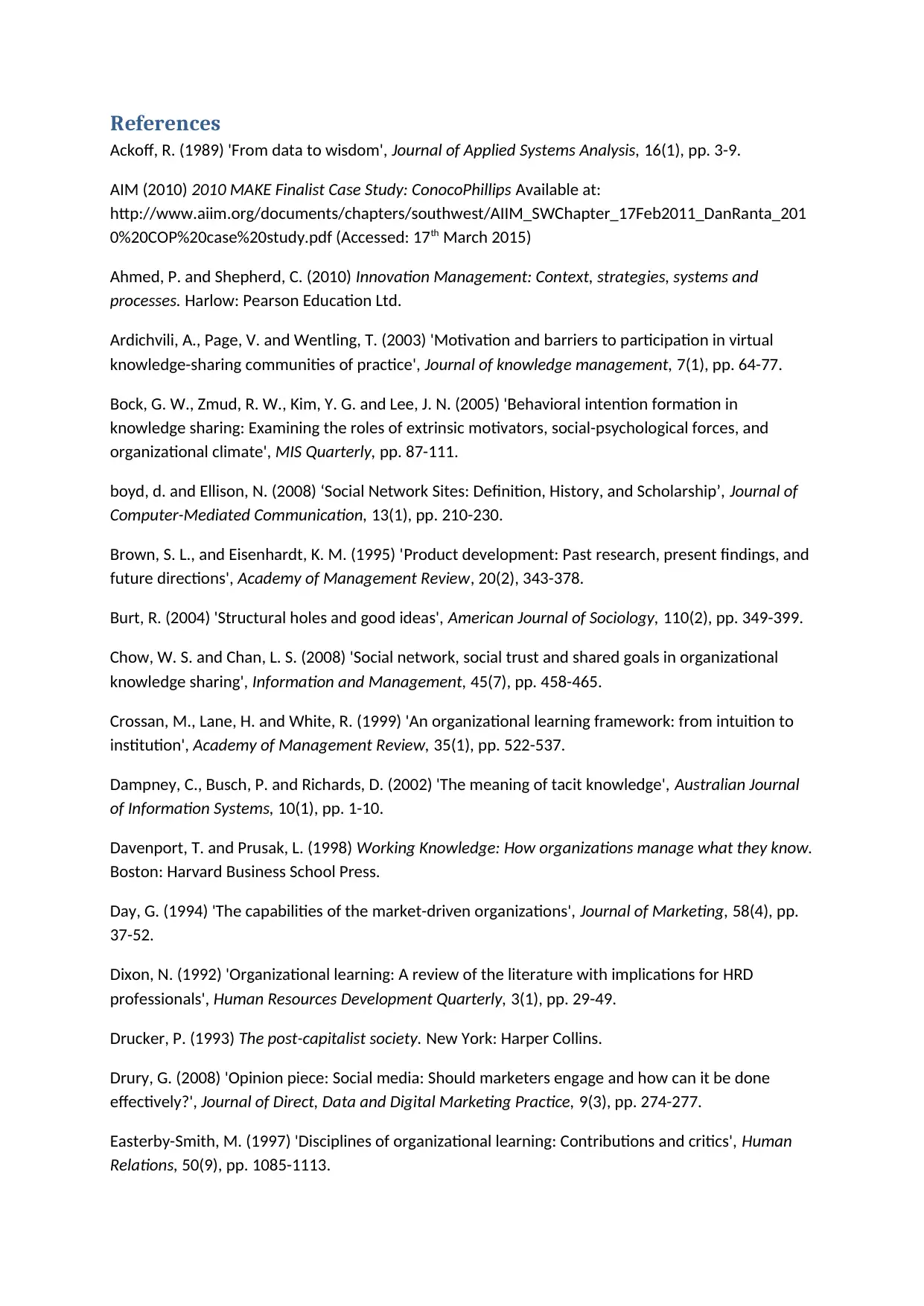

Using the framework

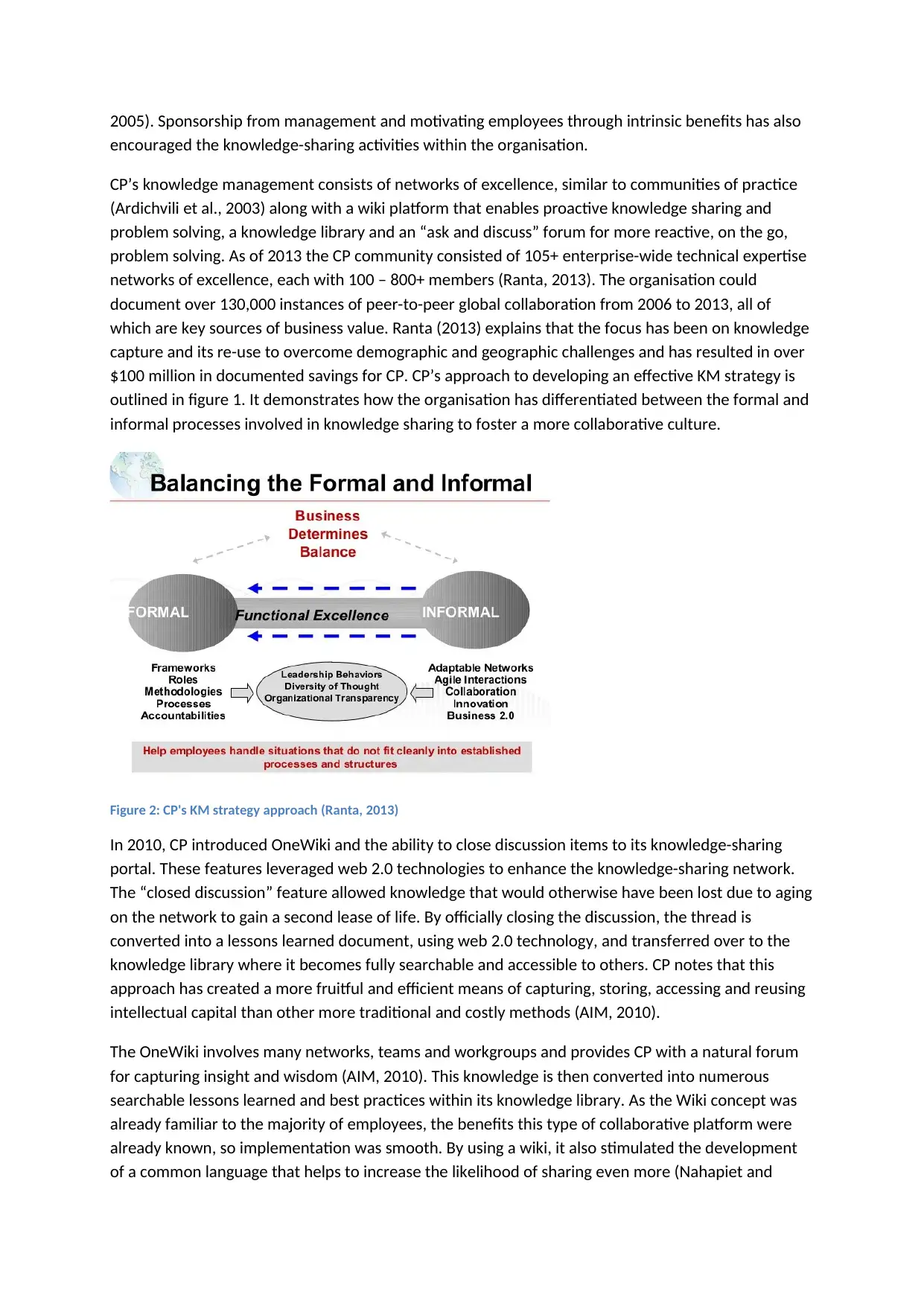

Figure 3: Overview of KM system in CP (Ranta, 2013)

Using figure 3, it is possible to see how knowledge flows through the KM of CP this can then be

applied to figure 1. When applied to the model in figure 1, the CP approach to KM clearly shows the

knowledge creation process being developed at three of the four levels: individual, group or

collective and organisational. CP’s KM does not appear at present to include the interorganisational

level, but this is not surprising, as the energy industry is highly competitive and as such, CP would

seek to protect its intellectual capital and internal knowledge. The CP model also clearly shows the

transfer of knowledge among these groups with individuals being able to add to the OneWiki and

search the repositories for useful information that will aid problem solving. Groups or networks are

also represented and are the primary forum for discussion within “Networks of Excellence”, here

individuals can contribute to the collective know-how and know-what and these contributions can

come from “Sister Networks” too. “Sister Networks” most likely represent the most common

platforms for knowledge transfer, as they would include the transfer of lessons learnt or best practice

from one part or division of the organisation to another.

The knowledge library represents the storing of knowledge in the collective memory and the

collaborative nature represented by over 100 active networks demonstrates the feed-back and feed-

forward loops between socialisation and externalisation. CP has tried to approach their KM strategy

from a holistic standpoint and Garcia-Fernandez’s (2014) model has attempted to produce an

integrated approach to KM, which makes this framework ideal for evaluating CP.

issues and branding the wiki as “OneWiki” helped to consolidate the system contextually as the

ConocoPhillips encyclopaedia and go–to knowledge repository.

Using the framework

Figure 3: Overview of KM system in CP (Ranta, 2013)

Using figure 3, it is possible to see how knowledge flows through the KM of CP this can then be

applied to figure 1. When applied to the model in figure 1, the CP approach to KM clearly shows the

knowledge creation process being developed at three of the four levels: individual, group or

collective and organisational. CP’s KM does not appear at present to include the interorganisational

level, but this is not surprising, as the energy industry is highly competitive and as such, CP would

seek to protect its intellectual capital and internal knowledge. The CP model also clearly shows the

transfer of knowledge among these groups with individuals being able to add to the OneWiki and

search the repositories for useful information that will aid problem solving. Groups or networks are

also represented and are the primary forum for discussion within “Networks of Excellence”, here

individuals can contribute to the collective know-how and know-what and these contributions can

come from “Sister Networks” too. “Sister Networks” most likely represent the most common

platforms for knowledge transfer, as they would include the transfer of lessons learnt or best practice

from one part or division of the organisation to another.

The knowledge library represents the storing of knowledge in the collective memory and the

collaborative nature represented by over 100 active networks demonstrates the feed-back and feed-

forward loops between socialisation and externalisation. CP has tried to approach their KM strategy

from a holistic standpoint and Garcia-Fernandez’s (2014) model has attempted to produce an

integrated approach to KM, which makes this framework ideal for evaluating CP.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Using the framework suggests that CP has indeed managed to achieve a holistic approach, as it fulfils

all stages of the integrated model and knowledge has become firmly embedded in these tools. The

CP case study has provided some validation of the integrated nature of the model.

CP has fostered a collaborative and trusting culture throughout the organisation. This culture has

been critical in CP’s ability to achieve a high level of success with its KM strategy. The organisational

has primarily been driving process and procedural innovation and is regarded as a leader in

enterprise-wide knowledge management (AIM, 2010). As of June 2013, CP could document a saving

of over $100 million due to innovation in business processes and procedures as a direct consequence

of its KM system.

Conclusion

There is an increasing body of literature that links the use of SM and web 2.0 technologies to KM and

OL, as a method for capturing and sharing tacit knowledge in organisations. Historically, it has been

tacit knowledge that has proved challenging for KM systems to manage and in order for an

organisation to learn effectively it must be able to capture both explicit and tacit knowledge.

Through the application of SM tools to facilitate knowledge-sharing in CP, it is clear that these tools

have led to innovations in processes and procedures and have made major cost savings for the

organisation. CP’s matrix structure along with global collaboration can also provide many

opportunities for filling network holes thus increasing the chances of innovation. The literature

supports these findings and maintains that similar opportunities for innovation can be seen in other

organisation when SM is used to exploit knowledge. The advantages that are afforded through SM

for sharing and disseminating knowledge (including making it searchable) will inevitably lead to

increased competitive advantage and innovation for those organisations who manage to achieve

excellent implementation of these technologies, and cultivate a positive and trusting culture towards

knowledge-sharing.

This essay has by no means covered the full extent of the literature available on OL, KM or the use of

SM to drive innovation. It is also limited, as it has not discussed the relationship of organisational

performance or explored a fine-grained analysis on the effect of organisational culture on KM. The

extent to which SM can cultivate a shared language and aid codifying knowledge should also be

explored in more detail. Further research is needed in these areas to understand how they relate to

innovation through SM initiatives.

all stages of the integrated model and knowledge has become firmly embedded in these tools. The

CP case study has provided some validation of the integrated nature of the model.

CP has fostered a collaborative and trusting culture throughout the organisation. This culture has

been critical in CP’s ability to achieve a high level of success with its KM strategy. The organisational

has primarily been driving process and procedural innovation and is regarded as a leader in

enterprise-wide knowledge management (AIM, 2010). As of June 2013, CP could document a saving

of over $100 million due to innovation in business processes and procedures as a direct consequence

of its KM system.

Conclusion

There is an increasing body of literature that links the use of SM and web 2.0 technologies to KM and

OL, as a method for capturing and sharing tacit knowledge in organisations. Historically, it has been

tacit knowledge that has proved challenging for KM systems to manage and in order for an

organisation to learn effectively it must be able to capture both explicit and tacit knowledge.

Through the application of SM tools to facilitate knowledge-sharing in CP, it is clear that these tools

have led to innovations in processes and procedures and have made major cost savings for the

organisation. CP’s matrix structure along with global collaboration can also provide many

opportunities for filling network holes thus increasing the chances of innovation. The literature

supports these findings and maintains that similar opportunities for innovation can be seen in other

organisation when SM is used to exploit knowledge. The advantages that are afforded through SM

for sharing and disseminating knowledge (including making it searchable) will inevitably lead to

increased competitive advantage and innovation for those organisations who manage to achieve

excellent implementation of these technologies, and cultivate a positive and trusting culture towards

knowledge-sharing.

This essay has by no means covered the full extent of the literature available on OL, KM or the use of

SM to drive innovation. It is also limited, as it has not discussed the relationship of organisational

performance or explored a fine-grained analysis on the effect of organisational culture on KM. The

extent to which SM can cultivate a shared language and aid codifying knowledge should also be

explored in more detail. Further research is needed in these areas to understand how they relate to

innovation through SM initiatives.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

References

Ackoff, R. (1989) 'From data to wisdom', Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 16(1), pp. 3-9.

AIM (2010) 2010 MAKE Finalist Case Study: ConocoPhillips Available at:

http://www.aiim.org/documents/chapters/southwest/AIIM_SWChapter_17Feb2011_DanRanta_201

0%20COP%20case%20study.pdf (Accessed: 17th March 2015)

Ahmed, P. and Shepherd, C. (2010) Innovation Management: Context, strategies, systems and

processes. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Ardichvili, A., Page, V. and Wentling, T. (2003) 'Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual

knowledge-sharing communities of practice', Journal of knowledge management, 7(1), pp. 64-77.

Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G. and Lee, J. N. (2005) 'Behavioral intention formation in

knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and

organizational climate', MIS Quarterly, pp. 87-111.

boyd, d. and Ellison, N. (2008) ‘Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship’, Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), pp. 210-230.

Brown, S. L., and Eisenhardt, K. M. (1995) 'Product development: Past research, present findings, and

future directions', Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 343-378.

Burt, R. (2004) 'Structural holes and good ideas', American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), pp. 349-399.

Chow, W. S. and Chan, L. S. (2008) 'Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational

knowledge sharing', Information and Management, 45(7), pp. 458-465.

Crossan, M., Lane, H. and White, R. (1999) 'An organizational learning framework: from intuition to

institution', Academy of Management Review, 35(1), pp. 522-537.

Dampney, C., Busch, P. and Richards, D. (2002) 'The meaning of tacit knowledge', Australian Journal

of Information Systems, 10(1), pp. 1-10.

Davenport, T. and Prusak, L. (1998) Working Knowledge: How organizations manage what they know.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Day, G. (1994) 'The capabilities of the market-driven organizations', Journal of Marketing, 58(4), pp.

37-52.

Dixon, N. (1992) 'Organizational learning: A review of the literature with implications for HRD

professionals', Human Resources Development Quarterly, 3(1), pp. 29-49.

Drucker, P. (1993) The post-capitalist society. New York: Harper Collins.

Drury, G. (2008) 'Opinion piece: Social media: Should marketers engage and how can it be done

effectively?', Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3), pp. 274-277.

Easterby-Smith, M. (1997) 'Disciplines of organizational learning: Contributions and critics', Human

Relations, 50(9), pp. 1085-1113.

Ackoff, R. (1989) 'From data to wisdom', Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 16(1), pp. 3-9.

AIM (2010) 2010 MAKE Finalist Case Study: ConocoPhillips Available at:

http://www.aiim.org/documents/chapters/southwest/AIIM_SWChapter_17Feb2011_DanRanta_201

0%20COP%20case%20study.pdf (Accessed: 17th March 2015)

Ahmed, P. and Shepherd, C. (2010) Innovation Management: Context, strategies, systems and

processes. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Ardichvili, A., Page, V. and Wentling, T. (2003) 'Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual

knowledge-sharing communities of practice', Journal of knowledge management, 7(1), pp. 64-77.

Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G. and Lee, J. N. (2005) 'Behavioral intention formation in

knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and

organizational climate', MIS Quarterly, pp. 87-111.

boyd, d. and Ellison, N. (2008) ‘Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship’, Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), pp. 210-230.

Brown, S. L., and Eisenhardt, K. M. (1995) 'Product development: Past research, present findings, and

future directions', Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 343-378.

Burt, R. (2004) 'Structural holes and good ideas', American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), pp. 349-399.

Chow, W. S. and Chan, L. S. (2008) 'Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational

knowledge sharing', Information and Management, 45(7), pp. 458-465.

Crossan, M., Lane, H. and White, R. (1999) 'An organizational learning framework: from intuition to

institution', Academy of Management Review, 35(1), pp. 522-537.

Dampney, C., Busch, P. and Richards, D. (2002) 'The meaning of tacit knowledge', Australian Journal

of Information Systems, 10(1), pp. 1-10.

Davenport, T. and Prusak, L. (1998) Working Knowledge: How organizations manage what they know.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Day, G. (1994) 'The capabilities of the market-driven organizations', Journal of Marketing, 58(4), pp.

37-52.

Dixon, N. (1992) 'Organizational learning: A review of the literature with implications for HRD

professionals', Human Resources Development Quarterly, 3(1), pp. 29-49.

Drucker, P. (1993) The post-capitalist society. New York: Harper Collins.

Drury, G. (2008) 'Opinion piece: Social media: Should marketers engage and how can it be done

effectively?', Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3), pp. 274-277.

Easterby-Smith, M. (1997) 'Disciplines of organizational learning: Contributions and critics', Human

Relations, 50(9), pp. 1085-1113.

Ellison, N., Lampe, C., Steinfield, C. and Vitak, J. (2010) 'With a little help from my friends: How Social

network sites affect Social Capital Processes', in Z. Papacharissi (ed.) A Networked self: Identity,

community, and culture on social network sites. New York: Routledge, pp. 124-145.

Foss, N. and Pedersen, T. (2002) 'Transferring knowledge in MNCs: The role of sources of subsidiary

knowledge and organizational context', Journal of International Management, 8(1), pp. 49-67.

Fugate, B., Stank, T. and Mentzer, J. (2009) 'Linking improved knowledge management to operational

and organizational performance', Journal of Operations Management, 27(3), pp. 247-264.

Garcia-Fernandez, M. (2015) 'How to measure knowledge management: dimensions and model',

VINE, 45(1), pp. 107-125.

Goh, S. (2002) 'Managing effective knowledge transfer: an integrative framework and some practice

implications', Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(1), pp. 23-30.

Grant, R. (1996) 'Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm', Strategic Management Journal,

17(S2), pp. 109-122.

Haldin-Herrgard, T. (2000) 'Difficulties in diffusion of tacit knowledge in organizations', Journal of

Intellectual Capital, 1(4), pp. 357-365.

Hall, R. and Andriani, P. (2003) 'Managing knowledge associated with innovation', Journal of Business

Research, 56(2), pp. 145-152.

Hauser, C., Tappeiner, G. and and Walde, J. (2007) 'The learning region: the impact of social capital

and weak ties on innovation', Regional Studies, 41(1), pp. 75-88.

Ho, C. (2009) 'The relationship between knowledge management enablers and performance'

Industrial Management and Data Systems, 109(1), pp. 98-117.

Huber, G. (1991) 'Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures',

Organization Science, 22(4), pp. 88-115.

Hurley, R. and Hult, G. (1998) 'Innovation, market orientation and organisational learning: an

integration and empirical examination', The Journal of Marketing, pp. 42-54.

Kaplan, A. and Haenlein, M. (2010) 'Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of

Social Media', Business Horizons, 53(1), pp. 59-68.

King, W., Marks, P. and McCoy, S. (2002) 'The most important issues in knowledge management',

Communications of the ACM, 45(9), pp. 93-97.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992) 'Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication

of technology', Organization Science, 18(1), pp. 39-54.

Leidner, D. and Alavi, M. (2006) 'The role of culture in knowledge management: a case study of two

global firms', International Journal of e-Collaboration, 2(1), pp. 17-40.

Lesser, E. (2000) Knowledge and Social Capital: Foundations and Applications. USA: Butterworth

Heinemann.

network sites affect Social Capital Processes', in Z. Papacharissi (ed.) A Networked self: Identity,

community, and culture on social network sites. New York: Routledge, pp. 124-145.

Foss, N. and Pedersen, T. (2002) 'Transferring knowledge in MNCs: The role of sources of subsidiary

knowledge and organizational context', Journal of International Management, 8(1), pp. 49-67.

Fugate, B., Stank, T. and Mentzer, J. (2009) 'Linking improved knowledge management to operational

and organizational performance', Journal of Operations Management, 27(3), pp. 247-264.

Garcia-Fernandez, M. (2015) 'How to measure knowledge management: dimensions and model',

VINE, 45(1), pp. 107-125.

Goh, S. (2002) 'Managing effective knowledge transfer: an integrative framework and some practice

implications', Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(1), pp. 23-30.

Grant, R. (1996) 'Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm', Strategic Management Journal,

17(S2), pp. 109-122.

Haldin-Herrgard, T. (2000) 'Difficulties in diffusion of tacit knowledge in organizations', Journal of

Intellectual Capital, 1(4), pp. 357-365.

Hall, R. and Andriani, P. (2003) 'Managing knowledge associated with innovation', Journal of Business

Research, 56(2), pp. 145-152.

Hauser, C., Tappeiner, G. and and Walde, J. (2007) 'The learning region: the impact of social capital

and weak ties on innovation', Regional Studies, 41(1), pp. 75-88.

Ho, C. (2009) 'The relationship between knowledge management enablers and performance'

Industrial Management and Data Systems, 109(1), pp. 98-117.

Huber, G. (1991) 'Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures',

Organization Science, 22(4), pp. 88-115.

Hurley, R. and Hult, G. (1998) 'Innovation, market orientation and organisational learning: an

integration and empirical examination', The Journal of Marketing, pp. 42-54.

Kaplan, A. and Haenlein, M. (2010) 'Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of

Social Media', Business Horizons, 53(1), pp. 59-68.

King, W., Marks, P. and McCoy, S. (2002) 'The most important issues in knowledge management',

Communications of the ACM, 45(9), pp. 93-97.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992) 'Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication

of technology', Organization Science, 18(1), pp. 39-54.

Leidner, D. and Alavi, M. (2006) 'The role of culture in knowledge management: a case study of two

global firms', International Journal of e-Collaboration, 2(1), pp. 17-40.

Lesser, E. (2000) Knowledge and Social Capital: Foundations and Applications. USA: Butterworth

Heinemann.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Levy, M. (2009) 'Web 2.0 implications on knowledge management', Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13(1), pp.120-134

O'Mahony, S. and Ferraro, F. (2007) 'The emergence of governance in an open source community',

The Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), pp. 1079-1106

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998) 'Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational

advantage', Academy of management review, 23(2), pp. 242-266.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The knowledge-creating company. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Nonaka, I. and von Krogh, G. (2009) 'Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and

advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory', Organization Science, 20(3), pp. 635-652.

Pavlicek, A. (2009) The challenges of tacit knowledge sharing in a Wiki system. Czech, 17th

Interdisciplinary Information and Management Talks (IDIMT).

Plessis, M. (2007) 'The role of knowledge management in innovation', Journal of Knowledge

Management, 11(4), pp. 20-29.

Polanyi, M. (1983) The Tacit Dimension. Gloucester: Peter Smith.

Ranta, D. (2013) Power of Connections at ConocoPhillips Available at:

http://www.slideshare.net/SIKM/dan-ranta-power-of-connections-at-conocophillips (Accessed: 17th

March 2015)

Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K. and Sudzina, F. (2009) 'Personal knowledge management: the role of web

2.0 tools for managing knowledge at individual and organizational level', Online Information Review,

33(6), pp. 1021-1039

Riege, A. (2005) 'Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers managers must consider', Journal of

knowledge management, 9(3), pp. 18-35.

Schein, E. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Senge, P. (1992) The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. 1st ed. New

York: Century Business.

Slater, S. and Narver, J. (1995) 'Market orientation and the learning organization', Journal of

Marketing, 59(3), pp. 63-74.

Smith, E. (2001) 'The role of tacit and explicit knowledge in the workplace', Journal of Knowledge

Management, 5(4), pp. 311-321.

Spender, J. and Grant, R. (1996) 'Knowledge and the firm: Overview', Strategic Management Journal,

17(S2), pp. 5-9.

Steininger, K., Ruckel, D., Dannerer, E. and Roithmayr, F. (2010) 'Healthcare knowledge transfer

through a web 2.0 portal: An Austrian approach', International Journal of Healthcare Technology and

Management, 11(1), pp. 13-30.

Management, 13(1), pp.120-134

O'Mahony, S. and Ferraro, F. (2007) 'The emergence of governance in an open source community',

The Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), pp. 1079-1106

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998) 'Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational

advantage', Academy of management review, 23(2), pp. 242-266.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The knowledge-creating company. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Nonaka, I. and von Krogh, G. (2009) 'Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and

advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory', Organization Science, 20(3), pp. 635-652.

Pavlicek, A. (2009) The challenges of tacit knowledge sharing in a Wiki system. Czech, 17th

Interdisciplinary Information and Management Talks (IDIMT).

Plessis, M. (2007) 'The role of knowledge management in innovation', Journal of Knowledge

Management, 11(4), pp. 20-29.

Polanyi, M. (1983) The Tacit Dimension. Gloucester: Peter Smith.

Ranta, D. (2013) Power of Connections at ConocoPhillips Available at:

http://www.slideshare.net/SIKM/dan-ranta-power-of-connections-at-conocophillips (Accessed: 17th

March 2015)

Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K. and Sudzina, F. (2009) 'Personal knowledge management: the role of web

2.0 tools for managing knowledge at individual and organizational level', Online Information Review,

33(6), pp. 1021-1039

Riege, A. (2005) 'Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers managers must consider', Journal of

knowledge management, 9(3), pp. 18-35.

Schein, E. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Senge, P. (1992) The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. 1st ed. New

York: Century Business.

Slater, S. and Narver, J. (1995) 'Market orientation and the learning organization', Journal of

Marketing, 59(3), pp. 63-74.

Smith, E. (2001) 'The role of tacit and explicit knowledge in the workplace', Journal of Knowledge

Management, 5(4), pp. 311-321.

Spender, J. and Grant, R. (1996) 'Knowledge and the firm: Overview', Strategic Management Journal,

17(S2), pp. 5-9.

Steininger, K., Ruckel, D., Dannerer, E. and Roithmayr, F. (2010) 'Healthcare knowledge transfer

through a web 2.0 portal: An Austrian approach', International Journal of Healthcare Technology and

Management, 11(1), pp. 13-30.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Sørensen, J. and Stuart, T. (2000) 'Aging, obsolescence, and organizational innovation', Administrative

Science Quarterly, 45(1), pp. 81-112.

Teece, D. (2007) 'Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable)

enterprise performance', Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), pp. 1319-1350.

Tippins, M. and Sohi, R. (2003) 'IT competency and firm performance: is organisational learning a

missing link?', Strategic Management Journal, 24(8), pp. 745-761.

von Hippel, E. and von Krogh, G. (2003) 'Open source software and the "private-collective"

innovation model: Issues for organisation science', Organization Science, 14(2), pp. 209-223

von Krogh, G. (1998) 'Care in knowledge creation', California Management Review, 40(3), pp. 133-

154.

Yang, S. and Farn, C. (2009) 'Social capital, behavioural control, and tacit knowledge sharing - A multi-

informant design', International Journal of Information Management, 29(3), pp. 210-218.

Science Quarterly, 45(1), pp. 81-112.

Teece, D. (2007) 'Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable)

enterprise performance', Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), pp. 1319-1350.

Tippins, M. and Sohi, R. (2003) 'IT competency and firm performance: is organisational learning a

missing link?', Strategic Management Journal, 24(8), pp. 745-761.

von Hippel, E. and von Krogh, G. (2003) 'Open source software and the "private-collective"

innovation model: Issues for organisation science', Organization Science, 14(2), pp. 209-223

von Krogh, G. (1998) 'Care in knowledge creation', California Management Review, 40(3), pp. 133-

154.

Yang, S. and Farn, C. (2009) 'Social capital, behavioural control, and tacit knowledge sharing - A multi-

informant design', International Journal of Information Management, 29(3), pp. 210-218.

1 out of 11