LLM Advanced Legal Skills: Donoghue v Stevenson Case Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/21

|19

|12544

|307

Case Study

AI Summary

This document presents a comprehensive case analysis of Donoghue v Stevenson, a landmark case in negligence law. The analysis begins with a summary of the material facts, legal issues, and the court's decision. It delves into the differences in reasoning between the majority and dissenting judgments, with a critical assessment of Lord Atkin's judgment. The assignment explores the 'neighbour principle', its origins, and its development in the UK and other jurisdictions. Furthermore, it examines the relevance of Donoghue v Stevenson to the environmental problem of oil spills in Nigeria, assessing the effectiveness of the legal principles in regulating the conduct of oil companies. The analysis includes a detailed examination of the legal principles, critical evaluations of the judgments, and application of the law to a contemporary issue, demonstrating a strong understanding of legal research, analysis, and reasoning.

1

LLM International Business Law

LAWS 7100 Advanced Legal Skills

End of module assessment: Case analysis

LLM International Business Law

LAWS 7100 Advanced Legal Skills

End of module assessment: Case analysis

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Instructions:

a) This assessment is weighted 100% towards your final module mark. Please

submit your work on or before the deadline stipulated on the assessment forum.

b) Please read the facts and decision in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 in full.

c) You are then required to answer all the questions numbered 1-9. The word

limit is 4000 words. Please note that there is a maximum 10% leverage to

exceed the word count. However, any words over this threshold will result in a

penalty or in the exceeding wordage not being marked by the moderators.

d) The aim of this assignment is an opportunity for you to demonstrate your

understanding and legal skills in undertaking legal research, undertaking analysis

of legal texts, reasoning skills, presenting research, and very importantly the ability

to reference appropriately using the OSCOLA method.

e) You are required to demonstrate the following learning and skills:

Demonstrate a critical and comprehensive understanding of the

techniques and methods applicable to postgraduate legal research and

legal methodology

Critically evaluate and demonstrate the ability to conceive, design,

implement and adapt a substantial piece of research with scholarly integrity

Demonstrate critical, reflective and advanced intellectual engagement

with difficult issues in law

Analytically integrate knowledge, handle complexity and

formulate judgments with incomplete or limited information

Critically appraise and communicate your conclusions and the knowledge

and rationale underpinning these, to specialist and non-specialist

audiences clearly and unambiguously

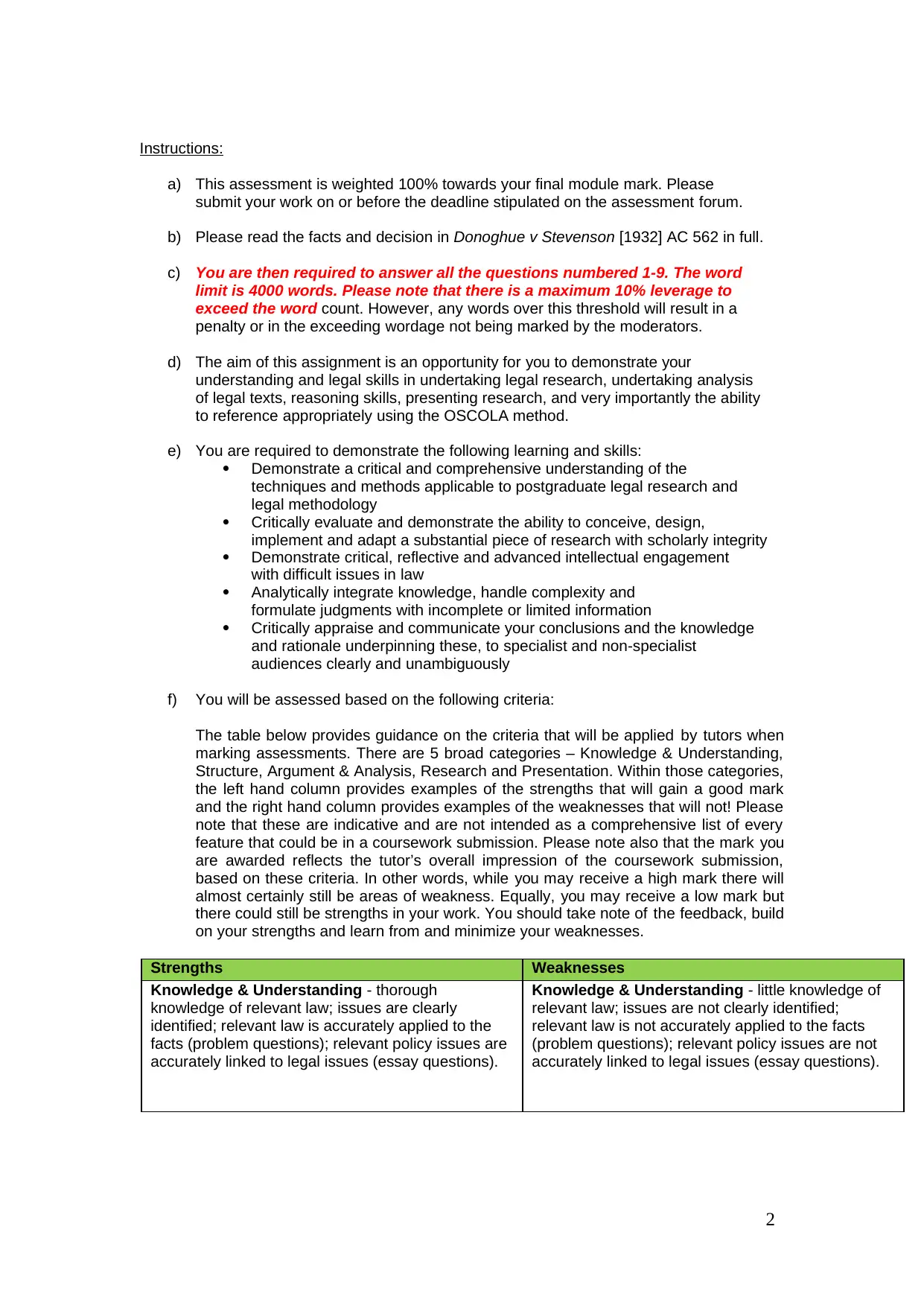

f) You will be assessed based on the following criteria:

The table below provides guidance on the criteria that will be applied by tutors when

marking assessments. There are 5 broad categories – Knowledge & Understanding,

Structure, Argument & Analysis, Research and Presentation. Within those categories,

the left hand column provides examples of the strengths that will gain a good mark

and the right hand column provides examples of the weaknesses that will not! Please

note that these are indicative and are not intended as a comprehensive list of every

feature that could be in a coursework submission. Please note also that the mark you

are awarded reflects the tutor’s overall impression of the coursework submission,

based on these criteria. In other words, while you may receive a high mark there will

almost certainly still be areas of weakness. Equally, you may receive a low mark but

there could still be strengths in your work. You should take note of the feedback, build

on your strengths and learn from and minimize your weaknesses.

Strengths Weaknesses

Knowledge & Understanding - thorough

knowledge of relevant law; issues are clearly

identified; relevant law is accurately applied to the

facts (problem questions); relevant policy issues are

accurately linked to legal issues (essay questions).

Knowledge & Understanding - little knowledge of

relevant law; issues are not clearly identified;

relevant law is not accurately applied to the facts

(problem questions); relevant policy issues are not

accurately linked to legal issues (essay questions).

Instructions:

a) This assessment is weighted 100% towards your final module mark. Please

submit your work on or before the deadline stipulated on the assessment forum.

b) Please read the facts and decision in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 in full.

c) You are then required to answer all the questions numbered 1-9. The word

limit is 4000 words. Please note that there is a maximum 10% leverage to

exceed the word count. However, any words over this threshold will result in a

penalty or in the exceeding wordage not being marked by the moderators.

d) The aim of this assignment is an opportunity for you to demonstrate your

understanding and legal skills in undertaking legal research, undertaking analysis

of legal texts, reasoning skills, presenting research, and very importantly the ability

to reference appropriately using the OSCOLA method.

e) You are required to demonstrate the following learning and skills:

Demonstrate a critical and comprehensive understanding of the

techniques and methods applicable to postgraduate legal research and

legal methodology

Critically evaluate and demonstrate the ability to conceive, design,

implement and adapt a substantial piece of research with scholarly integrity

Demonstrate critical, reflective and advanced intellectual engagement

with difficult issues in law

Analytically integrate knowledge, handle complexity and

formulate judgments with incomplete or limited information

Critically appraise and communicate your conclusions and the knowledge

and rationale underpinning these, to specialist and non-specialist

audiences clearly and unambiguously

f) You will be assessed based on the following criteria:

The table below provides guidance on the criteria that will be applied by tutors when

marking assessments. There are 5 broad categories – Knowledge & Understanding,

Structure, Argument & Analysis, Research and Presentation. Within those categories,

the left hand column provides examples of the strengths that will gain a good mark

and the right hand column provides examples of the weaknesses that will not! Please

note that these are indicative and are not intended as a comprehensive list of every

feature that could be in a coursework submission. Please note also that the mark you

are awarded reflects the tutor’s overall impression of the coursework submission,

based on these criteria. In other words, while you may receive a high mark there will

almost certainly still be areas of weakness. Equally, you may receive a low mark but

there could still be strengths in your work. You should take note of the feedback, build

on your strengths and learn from and minimize your weaknesses.

Strengths Weaknesses

Knowledge & Understanding - thorough

knowledge of relevant law; issues are clearly

identified; relevant law is accurately applied to the

facts (problem questions); relevant policy issues are

accurately linked to legal issues (essay questions).

Knowledge & Understanding - little knowledge of

relevant law; issues are not clearly identified;

relevant law is not accurately applied to the facts

(problem questions); relevant policy issues are not

accurately linked to legal issues (essay questions).

3

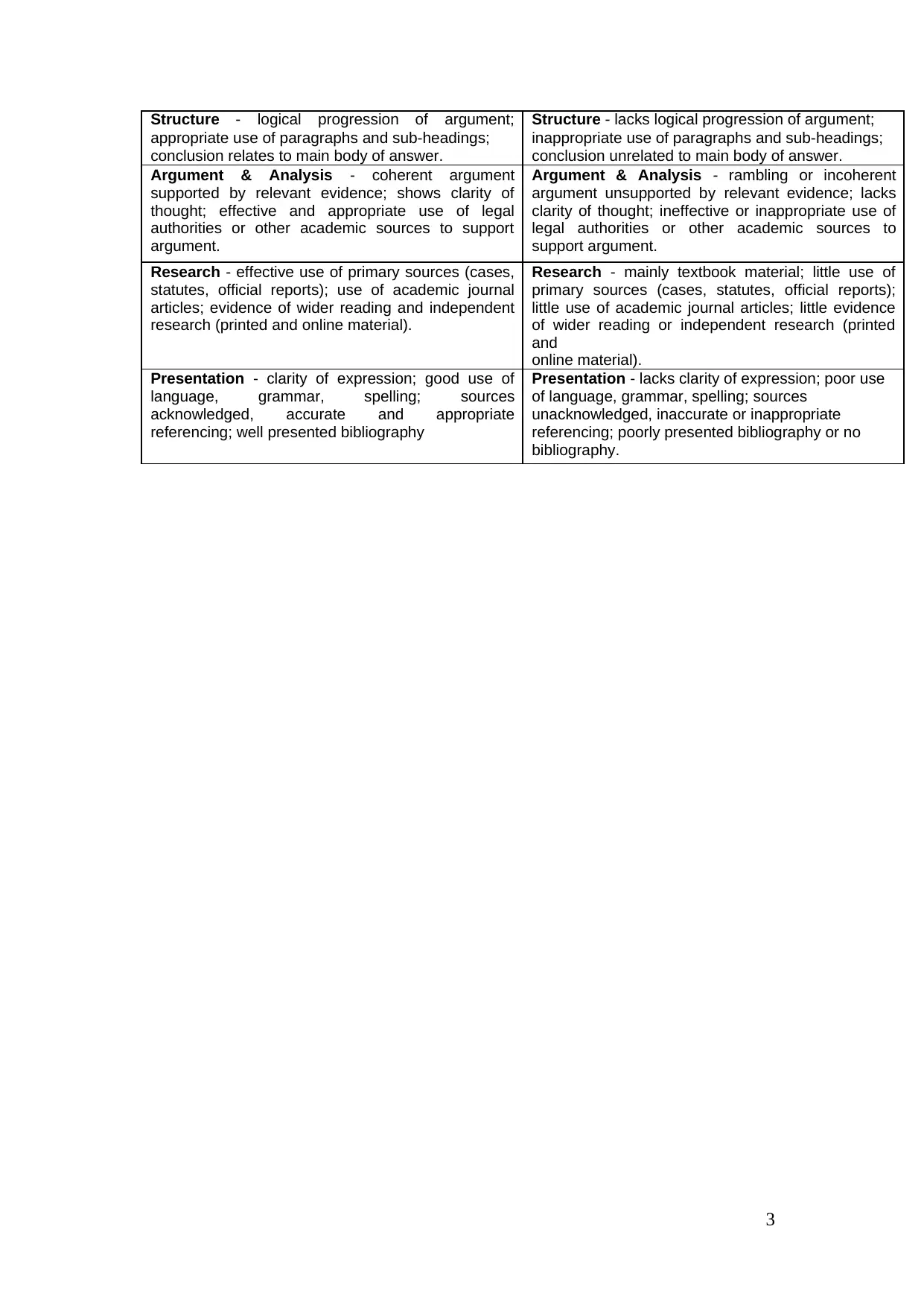

Structure - logical progression of argument;

appropriate use of paragraphs and sub-headings;

conclusion relates to main body of answer.

Structure - lacks logical progression of argument;

inappropriate use of paragraphs and sub-headings;

conclusion unrelated to main body of answer.

Argument & Analysis - coherent argument

supported by relevant evidence; shows clarity of

thought; effective and appropriate use of legal

authorities or other academic sources to support

argument.

Argument & Analysis - rambling or incoherent

argument unsupported by relevant evidence; lacks

clarity of thought; ineffective or inappropriate use of

legal authorities or other academic sources to

support argument.

Research - effective use of primary sources (cases,

statutes, official reports); use of academic journal

articles; evidence of wider reading and independent

research (printed and online material).

Research - mainly textbook material; little use of

primary sources (cases, statutes, official reports);

little use of academic journal articles; little evidence

of wider reading or independent research (printed

and

online material).

Presentation - clarity of expression; good use of

language, grammar, spelling; sources

acknowledged, accurate and appropriate

referencing; well presented bibliography

Presentation - lacks clarity of expression; poor use

of language, grammar, spelling; sources

unacknowledged, inaccurate or inappropriate

referencing; poorly presented bibliography or no

bibliography.

Structure - logical progression of argument;

appropriate use of paragraphs and sub-headings;

conclusion relates to main body of answer.

Structure - lacks logical progression of argument;

inappropriate use of paragraphs and sub-headings;

conclusion unrelated to main body of answer.

Argument & Analysis - coherent argument

supported by relevant evidence; shows clarity of

thought; effective and appropriate use of legal

authorities or other academic sources to support

argument.

Argument & Analysis - rambling or incoherent

argument unsupported by relevant evidence; lacks

clarity of thought; ineffective or inappropriate use of

legal authorities or other academic sources to

support argument.

Research - effective use of primary sources (cases,

statutes, official reports); use of academic journal

articles; evidence of wider reading and independent

research (printed and online material).

Research - mainly textbook material; little use of

primary sources (cases, statutes, official reports);

little use of academic journal articles; little evidence

of wider reading or independent research (printed

and

online material).

Presentation - clarity of expression; good use of

language, grammar, spelling; sources

acknowledged, accurate and appropriate

referencing; well presented bibliography

Presentation - lacks clarity of expression; poor use

of language, grammar, spelling; sources

unacknowledged, inaccurate or inappropriate

referencing; poorly presented bibliography or no

bibliography.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

LLM International Business Law

Advanced Legal Skills Assessment

Instructions:

a) This assessment is weighted 100% towards your final module mark. Please

submit your work on or before the deadline provided on the assessment

forum.

b) Please read the facts and decision in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 in

full and then answer the questions below. Please remember to check all

presentation requirements and include a bibliography.

Questions:

1. What were the material facts of the case?

2. What were the legal issues involved?

3. What was the decision of the court?

4. What were the main differences in reasoning between the majority

judgment(s) and the dissenting judgment(s)? Critically assess the

extent to which Aitkin’s judgement accurately reflects the opinion of the

majority judges.

5. What is the ‘neighbour principle’? Explain the term ‘neighbour’ and discuss

where the term might be derived from

6. Critically analyse the development of this principle both in the UK and in

other jurisdictions.

7. Read this article regarding the Oil Industry in Nigeria:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/may/30/oil-spills-nigeria-

niger-delta-shell . Explain how the principles of law from Donoghue v

Stevenson might be relevant to this environmental problem and assess

their effectiveness in regulation the conduct of oil companies.

LLM International Business Law

Advanced Legal Skills Assessment

Instructions:

a) This assessment is weighted 100% towards your final module mark. Please

submit your work on or before the deadline provided on the assessment

forum.

b) Please read the facts and decision in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 in

full and then answer the questions below. Please remember to check all

presentation requirements and include a bibliography.

Questions:

1. What were the material facts of the case?

2. What were the legal issues involved?

3. What was the decision of the court?

4. What were the main differences in reasoning between the majority

judgment(s) and the dissenting judgment(s)? Critically assess the

extent to which Aitkin’s judgement accurately reflects the opinion of the

majority judges.

5. What is the ‘neighbour principle’? Explain the term ‘neighbour’ and discuss

where the term might be derived from

6. Critically analyse the development of this principle both in the UK and in

other jurisdictions.

7. Read this article regarding the Oil Industry in Nigeria:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/may/30/oil-spills-nigeria-

niger-delta-shell . Explain how the principles of law from Donoghue v

Stevenson might be relevant to this environmental problem and assess

their effectiveness in regulation the conduct of oil companies.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

*562 M'Alister (or Donoghue) (Pauper) Appellant; v. Stevenson Respondent.

House of Lords HL

Lord Buckmaster, Lord Atkin, Lord Tomlin , Lord Thankerton, and Lord Macmillan.

1932 May 26.

Negligence--Liability of Manufacturer to ultimate Consumer--Article of Food--

Defect likely to cause Injury to Health.

By Scots and English law alike the manufacturer of an article of food, medicine or the

like, sold by him to a distributor in circumstances which prevent the distributor or

the ultimate purchaser or consumer from discovering by inspection any defect, is

under a legal duty to the ultimate purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care

that the article is free from defect likely to cause injury to health:-

So held,by Lord Atkin, Lord Thankerton and Lord Macmillan; Lord Buckmaster and

Lord Tomlin dissenting.

George v. Skivington (1869) L. R. 5 Ex. 1 approved.

Dicta of Brett M.R. in Heaven v. Pender (1883) 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509-11

considered.

Mullen v. Barr & Co., Ld., and M'Gowan v. Barr & Co., Ld., 1929 S. C. 461

overruled.

APPEAL against an interlocutor of the Second Division of the Court of Session in

Scotland recalling an interlocutor of the Lord Ordinary (Lord Moncrieff).

By an action brought in the Court of Session the appellant, who was a shop assistant,

sought to recover damages from the respondent, who was a manufacturer of

aerated waters, for injuries she suffered as a result of consuming part of the

contents of a bottle of ginger-beer which had been manufactured by the

respondent, and which contained the decomposed remains of a snail. The

appellant by her condescendence averred that the bottle of ginger-beer was

purchased for the appellant by a friend in a café at Paisley, which was occupied

by one Minchella; that the bottle was made of dark opaque glass and that the

appellant had no reason to suspect that it contained anything but pure ginger-

beer; that the said Minchella poured some of the ginger-beer out into a tumbler,

and that the appellant drank some of the contents of the tumbler; that her friend

was then proceeding to pour the remainder of the contents of the bottle into the

tumbler when a snail, which *563 was in a state of decomposition, floated out of

the bottle; that as a result of the nauseating sight of the snail in such

circumstances, and in consequence of the impurities in the ginger-beer which

she had already consumed, the appellant suffered from shock and severe gastro-

enteritis. The appellant further averred that the ginger-beer was manufactured

by the respondent to be sold as a drink to the public (including the appellant);

that it was bottled by the respondent and labelled by him with a label bearing his

name; and that the bottles were thereafter sealed with a metal cap by the

respondent.

She further averred that it was the duty of the respondent to provide a system of

working his business which would not allow snails to get into his ginger-beer

bottles, and that it was also his duty to provide an efficient system of inspection

of the bottles before the ginger-beer was filled into them, and that he had failed

*562 M'Alister (or Donoghue) (Pauper) Appellant; v. Stevenson Respondent.

House of Lords HL

Lord Buckmaster, Lord Atkin, Lord Tomlin , Lord Thankerton, and Lord Macmillan.

1932 May 26.

Negligence--Liability of Manufacturer to ultimate Consumer--Article of Food--

Defect likely to cause Injury to Health.

By Scots and English law alike the manufacturer of an article of food, medicine or the

like, sold by him to a distributor in circumstances which prevent the distributor or

the ultimate purchaser or consumer from discovering by inspection any defect, is

under a legal duty to the ultimate purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care

that the article is free from defect likely to cause injury to health:-

So held,by Lord Atkin, Lord Thankerton and Lord Macmillan; Lord Buckmaster and

Lord Tomlin dissenting.

George v. Skivington (1869) L. R. 5 Ex. 1 approved.

Dicta of Brett M.R. in Heaven v. Pender (1883) 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509-11

considered.

Mullen v. Barr & Co., Ld., and M'Gowan v. Barr & Co., Ld., 1929 S. C. 461

overruled.

APPEAL against an interlocutor of the Second Division of the Court of Session in

Scotland recalling an interlocutor of the Lord Ordinary (Lord Moncrieff).

By an action brought in the Court of Session the appellant, who was a shop assistant,

sought to recover damages from the respondent, who was a manufacturer of

aerated waters, for injuries she suffered as a result of consuming part of the

contents of a bottle of ginger-beer which had been manufactured by the

respondent, and which contained the decomposed remains of a snail. The

appellant by her condescendence averred that the bottle of ginger-beer was

purchased for the appellant by a friend in a café at Paisley, which was occupied

by one Minchella; that the bottle was made of dark opaque glass and that the

appellant had no reason to suspect that it contained anything but pure ginger-

beer; that the said Minchella poured some of the ginger-beer out into a tumbler,

and that the appellant drank some of the contents of the tumbler; that her friend

was then proceeding to pour the remainder of the contents of the bottle into the

tumbler when a snail, which *563 was in a state of decomposition, floated out of

the bottle; that as a result of the nauseating sight of the snail in such

circumstances, and in consequence of the impurities in the ginger-beer which

she had already consumed, the appellant suffered from shock and severe gastro-

enteritis. The appellant further averred that the ginger-beer was manufactured

by the respondent to be sold as a drink to the public (including the appellant);

that it was bottled by the respondent and labelled by him with a label bearing his

name; and that the bottles were thereafter sealed with a metal cap by the

respondent.

She further averred that it was the duty of the respondent to provide a system of

working his business which would not allow snails to get into his ginger-beer

bottles, and that it was also his duty to provide an efficient system of inspection

of the bottles before the ginger-beer was filled into them, and that he had failed

6

in both these duties and had so caused the accident.

The respondent objected that these averments were irrelevant and insufficient to

support the conclusions of the summons.

The Lord Ordinary held that the averments disclosed a good cause of action and

allowed a proof.

The Second Division by a majority (the Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Ormidale, and

Lord Anderson; Lord Hunter dissenting) recalled the interlocutor of the Lord

Ordinary and dismissed the action.

1931. Dec. 10, 11. George Morton K.C. (with him W. R. Milligan) (both of the

Scottish Bar) for the appellant. The facts averred by the appellant in her

condescendence disclose a relevant cause of action. In deciding this question

against the appellant the Second Division felt themselves bound by their previous

decision in Mullen v. Barr & Co., Ld. [FN1] It was there held that in determining

the question of the liability of the manufacturer to the consumer there was no

difference between the law of England and the law of Scotland - and this is not

now disputed - and that the question fell to be determined according to the

English authorities, and the majority of the Court (Lord Hunter dissenting) were of

opinion that in England there was a *564 long line of authority opposed to the

appellant's contention. The English authorities are not consistent, and the cases

relied on by the Court of Session differed essentially in their facts from the

present case. No case can be found where in circumstances similar to the present

the Court has held that the manufacturer is under no liability to the consumer.

The Court below has proceeded on the general principle that in an ordinary case

a manufacturer is under no duty to any one with whom he is not in any

contractual relation. To this rule there are two well known exceptions: (1.) where

the article is dangerous per se, and (2.) where the article is dangerous to the

knowledge of the manufacturer, but the appellant submits that the duty owed by

a manufacturer to members of the public is not capable of so strict a limitation,

and that the question whether a duty arises independently of contract depends

upon the circumstances of each particular case. When a manufacturer puts upon

a market an article intended for human consumption in a form which precludes

the possibility of an examination of the article by the retailer or the consumer, he

is liable to the consumer for not taking reasonable care to see that the article is

not injurious to health. In the circumstances of this case the respondent owed a

duty to the appellant to take care that the ginger-beer which he manufactured,

bottled, labelled and sealed (the conditions under which the ginger-beer was put

upon the market being such that it was impossible for the consumer to examine

the contents of the bottles), and which he invited the appellant to buy, contained

nothing which would cause her injury: George v. Skivington [FN2]; and see per

Brett M.R. in Heaven v. Pender [FN3] and per Lord Dunedin in Dominion Natural

Gas Co. v. Collins & Perkins. [FN4] George v. Skivington [FN5]has not always

been favourably commented on, but it has not been overruled, and it has been

referred to by this House without disapproval: Cavalier v. Pope. [FN6] In the

United States the law is laid down in the same way: Thomas v. Winchester. [FN7]

FN1 1929 S. C. 461.

FN2 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN3 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509 et seq.

FN4 [1909] A. C. 640, 646.

FN5 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN6 [1906] A. C. 428, 433.

FN7 (1852) 6 N. Y. 397.

in both these duties and had so caused the accident.

The respondent objected that these averments were irrelevant and insufficient to

support the conclusions of the summons.

The Lord Ordinary held that the averments disclosed a good cause of action and

allowed a proof.

The Second Division by a majority (the Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Ormidale, and

Lord Anderson; Lord Hunter dissenting) recalled the interlocutor of the Lord

Ordinary and dismissed the action.

1931. Dec. 10, 11. George Morton K.C. (with him W. R. Milligan) (both of the

Scottish Bar) for the appellant. The facts averred by the appellant in her

condescendence disclose a relevant cause of action. In deciding this question

against the appellant the Second Division felt themselves bound by their previous

decision in Mullen v. Barr & Co., Ld. [FN1] It was there held that in determining

the question of the liability of the manufacturer to the consumer there was no

difference between the law of England and the law of Scotland - and this is not

now disputed - and that the question fell to be determined according to the

English authorities, and the majority of the Court (Lord Hunter dissenting) were of

opinion that in England there was a *564 long line of authority opposed to the

appellant's contention. The English authorities are not consistent, and the cases

relied on by the Court of Session differed essentially in their facts from the

present case. No case can be found where in circumstances similar to the present

the Court has held that the manufacturer is under no liability to the consumer.

The Court below has proceeded on the general principle that in an ordinary case

a manufacturer is under no duty to any one with whom he is not in any

contractual relation. To this rule there are two well known exceptions: (1.) where

the article is dangerous per se, and (2.) where the article is dangerous to the

knowledge of the manufacturer, but the appellant submits that the duty owed by

a manufacturer to members of the public is not capable of so strict a limitation,

and that the question whether a duty arises independently of contract depends

upon the circumstances of each particular case. When a manufacturer puts upon

a market an article intended for human consumption in a form which precludes

the possibility of an examination of the article by the retailer or the consumer, he

is liable to the consumer for not taking reasonable care to see that the article is

not injurious to health. In the circumstances of this case the respondent owed a

duty to the appellant to take care that the ginger-beer which he manufactured,

bottled, labelled and sealed (the conditions under which the ginger-beer was put

upon the market being such that it was impossible for the consumer to examine

the contents of the bottles), and which he invited the appellant to buy, contained

nothing which would cause her injury: George v. Skivington [FN2]; and see per

Brett M.R. in Heaven v. Pender [FN3] and per Lord Dunedin in Dominion Natural

Gas Co. v. Collins & Perkins. [FN4] George v. Skivington [FN5]has not always

been favourably commented on, but it has not been overruled, and it has been

referred to by this House without disapproval: Cavalier v. Pope. [FN6] In the

United States the law is laid down in the same way: Thomas v. Winchester. [FN7]

FN1 1929 S. C. 461.

FN2 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN3 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509 et seq.

FN4 [1909] A. C. 640, 646.

FN5 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN6 [1906] A. C. 428, 433.

FN7 (1852) 6 N. Y. 397.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

*565 [He also referred to Dixon v. Bell [FN8]; Langridge v. Levy [FN9]; Longmeid

v. Holliday [FN10]; Bates v. Batey & Co., Ld. [FN11]; Weld-Blundell v. Stephens.

[FN12]]

FN8 (1816) 5 M. & S. 198.

FN9 (1837) 2 M. & W. 519; (1838) 4 M. & W. 337.

FN10 (1851) 6 Ex. 761.

FN11 [1913] 3 K. B. 351.

FN12 [1920] A. C. 956, 985.

W. G. Normand, Solicitor-General for Scotland (with him J. L. Clyde (of the

Scottish Bar) and T. Elder Jones (of the English Bar)) for the respondent. In an

ordinary case such as this the manufacturer owes no duty to the consumer apart

from contract. Admittedly the case does not come within either of the recognized

exceptions to the general rule, but it is sought to introduce into the law a third

exception in this particular case - namely, the case of goods intended for human

consumption sold to the public in a form in which investigation is impossible. The

reason now put forward by the appellant was no part of Lord Hunter's dissent in

the previous case; nor is there any hint of any such exception in any reported

case. There is here no suggestion of a trap, and there are no averments to

support it. It is said that people ought not to be allowed to put on the market

food or drink which is deleterious, but is there any real distinction between

articles of food or drink and any other article? In Heaven v. Pender [FN13]Brett

M.R. states the principle of liability too widely, and in Le Lievre v. Gould [FN14]

that principle is to a great extent whittled away by the Master of the Rolls himself

and by A. L. Smith L.J. The true ground was that founded on by Cotton and Bowen

L.JJ. in Heaven v. Pender. [FN15] In Blacker v. Lake & Elliot, Ld. [FN16] both

Hamilton and Lush JJ. treat George v. Skivington [FN17]as overruled. Hamilton J.

states the principle to be that the breach of the defendant's contract with A. to

use care and skill in the manufacture of an article does not per se give any cause

of action to B. if he is injured by reason of the article proving defective, and he

regards George v. Skivington [FN18], so far as it proceeds on duty to the ultimate

user, as inconsistent with Winterbottom v. Wright. [FN19] *566 [Counsel also

referred to Pollock on Torts, 13th ed., pp. 570, 571, and Beven on Negligence,

4th ed., vol. i., p. 49.] In England the law has taken a definite direction, which

tends away from the success of the appellant.

FN13 11 Q. B. D. 503.

FN14 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491.

FN15 11 Q. B. D. 503.

FN16 (1912) 106 L. T. 533.

FN17 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN18 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN19 (1842) 10 M. & W. 109.

George Morton K.C. replied.

The House took time for consideration. 1932. May 26.

LORD BUCKMASTER (read by LORD TOMLIN). My Lords, the facts of this case are

simple. On August 26, 1928, the appellant drank a bottle of ginger-beer,

manufactured by the respondent, which a friend had bought from a retailer and

given to her.

…

…

…

*565 [He also referred to Dixon v. Bell [FN8]; Langridge v. Levy [FN9]; Longmeid

v. Holliday [FN10]; Bates v. Batey & Co., Ld. [FN11]; Weld-Blundell v. Stephens.

[FN12]]

FN8 (1816) 5 M. & S. 198.

FN9 (1837) 2 M. & W. 519; (1838) 4 M. & W. 337.

FN10 (1851) 6 Ex. 761.

FN11 [1913] 3 K. B. 351.

FN12 [1920] A. C. 956, 985.

W. G. Normand, Solicitor-General for Scotland (with him J. L. Clyde (of the

Scottish Bar) and T. Elder Jones (of the English Bar)) for the respondent. In an

ordinary case such as this the manufacturer owes no duty to the consumer apart

from contract. Admittedly the case does not come within either of the recognized

exceptions to the general rule, but it is sought to introduce into the law a third

exception in this particular case - namely, the case of goods intended for human

consumption sold to the public in a form in which investigation is impossible. The

reason now put forward by the appellant was no part of Lord Hunter's dissent in

the previous case; nor is there any hint of any such exception in any reported

case. There is here no suggestion of a trap, and there are no averments to

support it. It is said that people ought not to be allowed to put on the market

food or drink which is deleterious, but is there any real distinction between

articles of food or drink and any other article? In Heaven v. Pender [FN13]Brett

M.R. states the principle of liability too widely, and in Le Lievre v. Gould [FN14]

that principle is to a great extent whittled away by the Master of the Rolls himself

and by A. L. Smith L.J. The true ground was that founded on by Cotton and Bowen

L.JJ. in Heaven v. Pender. [FN15] In Blacker v. Lake & Elliot, Ld. [FN16] both

Hamilton and Lush JJ. treat George v. Skivington [FN17]as overruled. Hamilton J.

states the principle to be that the breach of the defendant's contract with A. to

use care and skill in the manufacture of an article does not per se give any cause

of action to B. if he is injured by reason of the article proving defective, and he

regards George v. Skivington [FN18], so far as it proceeds on duty to the ultimate

user, as inconsistent with Winterbottom v. Wright. [FN19] *566 [Counsel also

referred to Pollock on Torts, 13th ed., pp. 570, 571, and Beven on Negligence,

4th ed., vol. i., p. 49.] In England the law has taken a definite direction, which

tends away from the success of the appellant.

FN13 11 Q. B. D. 503.

FN14 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491.

FN15 11 Q. B. D. 503.

FN16 (1912) 106 L. T. 533.

FN17 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN18 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN19 (1842) 10 M. & W. 109.

George Morton K.C. replied.

The House took time for consideration. 1932. May 26.

LORD BUCKMASTER (read by LORD TOMLIN). My Lords, the facts of this case are

simple. On August 26, 1928, the appellant drank a bottle of ginger-beer,

manufactured by the respondent, which a friend had bought from a retailer and

given to her.

…

…

…

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

LORD ATKIN.

My Lords, the sole question for determination in this case is legal: Do the

averments made by the pursuer in her pleading, if true, disclose a cause of

action? I need not restate the particular facts. The question is whether the

manufacturer of an article of drink sold by him to a distributor, in circumstances

which prevent the distributor or the ultimate purchaser or consumer from

discovering by inspection any defect, is under any legal duty to the ultimate

purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care that the article *579 is free from

defect likely to cause injury to health. I do not think a more important problem

has occupied your Lordships in your judicial capacity: important both because of

its bearing on public health and because of the practical test which it applies to

the system under which it arises. The case has to be determined in accordance

with Scots law; but it has been a matter of agreement between the experienced

counsel who argued this case, and it appears to be the basis of the judgments of

the learned judges of the Court of Session, that for the purposes of determining

this problem the laws of Scotland and of England are the same. I speak with little

authority on this point, but my own research, such as it is, satisfies me that the

principles of the law of Scotland on such a question as the present are identical

with those of English law; and I discuss the issue on that footing. The law of both

countries appears to be that in order to support an action for damages for

negligence the complainant has to show that he has been injured by the breach

of a duty owed to him in the circumstances by the defendant to take reasonable

care to avoid such injury. In the present case we are not concerned with the

breach of the duty; if a duty exists, that would be a question of fact which is

sufficiently averred and for present purposes must be assumed. We are solely

concerned with the question whether, as a matter of law in the circumstances

alleged, the defender owed any duty to the pursuer to take care.

It is remarkable how difficult it is to find in the English authorities statements of

general application defining the relations between parties that give rise to the

duty. The Courts are concerned with the particular relations which come before

them in actual litigation, and it is sufficient to say whether the duty exists in

those circumstances. The result is that the Courts have been engaged upon an

elaborate classification of duties as they exist in respect of property, whether real

or personal, with further divisions as to ownership, occupation or control, and

distinctions based on the particular relations of the one side or the other,

whether manufacturer, salesman or landlord, customer, tenant, stranger, and so

on. *580 In this way it can be ascertained at any time whether the law

recognizes a duty, but only where the case can be referred to some particular

species which has been examined and classified. And yet the duty which is

common to all the cases where liability is established must logically be based

upon some element common to the cases where it is found to exist. To seek a

complete logical definition of the general principle is probably to go beyond the

function of the judge, for the more general the definition the more likely it is to

omit essentials or to introduce non- essentials. The attempt was made by Brett

M.R. in Heaven v. Pender [FN79], in a definition to which I will later refer. As

framed, it was demonstrably too wide, though it appears to me, if properly

limited, to be capable of affording a valuable practical guide.

FN79 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

At present I content myself with pointing out that in English law there must be,

and is, some general conception of relations giving rise to a duty of care, of which

the particular cases found in the books are but instances. The liability for

negligence, whether you style it such or treat it as in other systems as a species

of "culpa," is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral

wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. But acts or omissions which any

LORD ATKIN.

My Lords, the sole question for determination in this case is legal: Do the

averments made by the pursuer in her pleading, if true, disclose a cause of

action? I need not restate the particular facts. The question is whether the

manufacturer of an article of drink sold by him to a distributor, in circumstances

which prevent the distributor or the ultimate purchaser or consumer from

discovering by inspection any defect, is under any legal duty to the ultimate

purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care that the article *579 is free from

defect likely to cause injury to health. I do not think a more important problem

has occupied your Lordships in your judicial capacity: important both because of

its bearing on public health and because of the practical test which it applies to

the system under which it arises. The case has to be determined in accordance

with Scots law; but it has been a matter of agreement between the experienced

counsel who argued this case, and it appears to be the basis of the judgments of

the learned judges of the Court of Session, that for the purposes of determining

this problem the laws of Scotland and of England are the same. I speak with little

authority on this point, but my own research, such as it is, satisfies me that the

principles of the law of Scotland on such a question as the present are identical

with those of English law; and I discuss the issue on that footing. The law of both

countries appears to be that in order to support an action for damages for

negligence the complainant has to show that he has been injured by the breach

of a duty owed to him in the circumstances by the defendant to take reasonable

care to avoid such injury. In the present case we are not concerned with the

breach of the duty; if a duty exists, that would be a question of fact which is

sufficiently averred and for present purposes must be assumed. We are solely

concerned with the question whether, as a matter of law in the circumstances

alleged, the defender owed any duty to the pursuer to take care.

It is remarkable how difficult it is to find in the English authorities statements of

general application defining the relations between parties that give rise to the

duty. The Courts are concerned with the particular relations which come before

them in actual litigation, and it is sufficient to say whether the duty exists in

those circumstances. The result is that the Courts have been engaged upon an

elaborate classification of duties as they exist in respect of property, whether real

or personal, with further divisions as to ownership, occupation or control, and

distinctions based on the particular relations of the one side or the other,

whether manufacturer, salesman or landlord, customer, tenant, stranger, and so

on. *580 In this way it can be ascertained at any time whether the law

recognizes a duty, but only where the case can be referred to some particular

species which has been examined and classified. And yet the duty which is

common to all the cases where liability is established must logically be based

upon some element common to the cases where it is found to exist. To seek a

complete logical definition of the general principle is probably to go beyond the

function of the judge, for the more general the definition the more likely it is to

omit essentials or to introduce non- essentials. The attempt was made by Brett

M.R. in Heaven v. Pender [FN79], in a definition to which I will later refer. As

framed, it was demonstrably too wide, though it appears to me, if properly

limited, to be capable of affording a valuable practical guide.

FN79 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

At present I content myself with pointing out that in English law there must be,

and is, some general conception of relations giving rise to a duty of care, of which

the particular cases found in the books are but instances. The liability for

negligence, whether you style it such or treat it as in other systems as a species

of "culpa," is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral

wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. But acts or omissions which any

9

moral code would censure cannot in a practical world be treated so as to give a

right to every person injured by them to demand relief. In this way rules of law

arise which limit the range of complainants and the extent of their remedy. The

rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure

your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a

restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which

you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then,

in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be - persons who are so closely

and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in

contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or

omissions which are called in question. This appears to me to be the doctrine of

Heaven v. Pender [FN80], *581 as laid down by Lord Esher (then Brett M.R.)

when it is limited by the notion of proximity introduced by Lord Esher himself and

A. L. Smith L.J. in Le Lievre v. Gould. [FN81] Lord Esher says: "That case

established that, under certain circumstances, one man may owe a duty to

another, even though there is no contract between them. If one man is near to

another, or is near to the property of another, a duty lies upon him not to do that

which may cause a personal injury to that other, or may injure his property." So

A. L. Smith L.J.: "The decision of Heaven v. Pender [FN82]was founded upon the

principle, that a duty to take due care did arise when the person or property of

one was in such proximity to the person or property of another that, if due care

was not taken, damage might be done by the one to the other." I think that this

sufficiently states the truth if proximity be not confined to mere physical

proximity, but be used, as I think it was intended, to extend to such close and

direct relations that the act complained of directly affects a person whom the

person alleged to be bound to take care would know would be directly affected

by his careless act.

That this is the sense in which nearness of "proximity " was intended by Lord

Esher is obvious from his own illustration in Heaven v. Pender [FN83] of the

application of his doctrine to the sale of goods. "This " (i.e., the rule he has just

formulated) "includes the case of goods, etc., supplied to be used immediately

by a particular person or persons, or one of a class of persons, where it would be

obvious to the person supplying, if he thought, that the goods would in all

probability be used at once by such persons before a reasonable opportunity for

discovering any defect which might exist, and where the thing supplied would be

of such a nature that a neglect of ordinary care or skill as to its condition or the

manner of supplying it would probably cause danger to the person or property of

the person for whose use it was supplied, and who was about to use it. It would

exclude a case in which the goods are supplied under circumstances in which it

would be a chance by whom they would be used *582 or whether they would be

used or not, or whether they would be used before there would probably be

means of observing any defect, or where the goods would be of such a nature

that a want of care or skill as to their condition or the manner of supplying them

would not probably produce danger of injury to person or property." I draw

particular attention to the fact that Lord Esher emphasizes the necessity of goods

having to be "used immediately" and "used at once before a reasonable

opportunity of inspection. " This is obviously to exclude the possibility of goods

having their condition altered by lapse of time, and to call attention to the

proximate relationship, which may be too remote where inspection even of the

person using, certainly of an intermediate person, may reasonably be interposed.

With this necessary qualification of proximate relationship as explained in Le

Lievre v. Gould [FN84], I think the judgment of Lord Esher expresses the law of

England; without the qualification, I think the majority of the Court in Heaven v.

Pender [FN85]were justified in thinking the principle was expressed in too

general terms. There will no doubt arise cases where it will be difficult to

determine whether the contemplated relationship is so close that the duty arises.

But in the class of case now before the Court I cannot conceive any difficulty to

arise. A manufacturer puts up an article of food in a container which he knows

will be

moral code would censure cannot in a practical world be treated so as to give a

right to every person injured by them to demand relief. In this way rules of law

arise which limit the range of complainants and the extent of their remedy. The

rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure

your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a

restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which

you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then,

in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be - persons who are so closely

and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in

contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or

omissions which are called in question. This appears to me to be the doctrine of

Heaven v. Pender [FN80], *581 as laid down by Lord Esher (then Brett M.R.)

when it is limited by the notion of proximity introduced by Lord Esher himself and

A. L. Smith L.J. in Le Lievre v. Gould. [FN81] Lord Esher says: "That case

established that, under certain circumstances, one man may owe a duty to

another, even though there is no contract between them. If one man is near to

another, or is near to the property of another, a duty lies upon him not to do that

which may cause a personal injury to that other, or may injure his property." So

A. L. Smith L.J.: "The decision of Heaven v. Pender [FN82]was founded upon the

principle, that a duty to take due care did arise when the person or property of

one was in such proximity to the person or property of another that, if due care

was not taken, damage might be done by the one to the other." I think that this

sufficiently states the truth if proximity be not confined to mere physical

proximity, but be used, as I think it was intended, to extend to such close and

direct relations that the act complained of directly affects a person whom the

person alleged to be bound to take care would know would be directly affected

by his careless act.

That this is the sense in which nearness of "proximity " was intended by Lord

Esher is obvious from his own illustration in Heaven v. Pender [FN83] of the

application of his doctrine to the sale of goods. "This " (i.e., the rule he has just

formulated) "includes the case of goods, etc., supplied to be used immediately

by a particular person or persons, or one of a class of persons, where it would be

obvious to the person supplying, if he thought, that the goods would in all

probability be used at once by such persons before a reasonable opportunity for

discovering any defect which might exist, and where the thing supplied would be

of such a nature that a neglect of ordinary care or skill as to its condition or the

manner of supplying it would probably cause danger to the person or property of

the person for whose use it was supplied, and who was about to use it. It would

exclude a case in which the goods are supplied under circumstances in which it

would be a chance by whom they would be used *582 or whether they would be

used or not, or whether they would be used before there would probably be

means of observing any defect, or where the goods would be of such a nature

that a want of care or skill as to their condition or the manner of supplying them

would not probably produce danger of injury to person or property." I draw

particular attention to the fact that Lord Esher emphasizes the necessity of goods

having to be "used immediately" and "used at once before a reasonable

opportunity of inspection. " This is obviously to exclude the possibility of goods

having their condition altered by lapse of time, and to call attention to the

proximate relationship, which may be too remote where inspection even of the

person using, certainly of an intermediate person, may reasonably be interposed.

With this necessary qualification of proximate relationship as explained in Le

Lievre v. Gould [FN84], I think the judgment of Lord Esher expresses the law of

England; without the qualification, I think the majority of the Court in Heaven v.

Pender [FN85]were justified in thinking the principle was expressed in too

general terms. There will no doubt arise cases where it will be difficult to

determine whether the contemplated relationship is so close that the duty arises.

But in the class of case now before the Court I cannot conceive any difficulty to

arise. A manufacturer puts up an article of food in a container which he knows

will be

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

opened by the actual consumer. There can be no inspection by any purchaser

and no reasonable preliminary inspection by the consumer. Negligently, in the

course of preparation, he allows the contents to be mixed with poison. It is said

that the law of England and Scotland is that the poisoned consumer has no

remedy against the negligent manufacturer. If this were the result of the

authorities, I should consider the result a grave defect in the law, and so contrary

to principle that I should hesitate long before following any decision to that effect

which had not the authority of this House. I would point out that, in the assumed

state of the authorities, not only would the consumer have no remedy against

the *583 manufacturer, he would have none against any one else, for in the

circumstances alleged there would be no evidence of negligence against any one

other than the manufacturer; and, except in the case of a consumer who was

also a purchaser, no contract and no warranty of fitness, and in the case of the

purchase of a specific article under its patent or trade name, which might well be

the case in the purchase of some articles of food or drink, no warranty protecting

even the purchaser-consumer. There are other instances than of articles of food

and drink where goods are sold intended to be used immediately by the

consumer, such as many forms of goods sold for cleaning purposes, where the

same liability must exist. The doctrine supported by the decision below would not

only deny a remedy to the consumer who was injured by consuming bottled beer

or chocolates poisoned by the negligence of the manufacturer, but also to the

user of what should be a harmless proprietary medicine, an ointment, a soap, a

cleaning fluid or cleaning powder. I confine myself to articles of common

household use, where every one, including the manufacturer, knows that the

articles will be used by other persons than the actual ultimate purchaser -

namely, by members of his family and his servants, and in some cases his

guests. I do not think so in of our jurisprudence as to suppose that its principles

are so remote from the ordinary needs of civilized society and the ordinary

claims it makes upon its members as to deny a legal remedy where there is so

obviously a social wrong.

FN80 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

FN81 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491, 497, 504.

FN82 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

FN83 11 Q. B. D. 503, 510.

FN84 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491.

FN85 11 Q. B. D. 503.

It will be found, I think, on examination that there is no case in which the

circumstances have been such as I have just suggested where the liability has

been negatived. There are numerous cases, where the relations were much more

remote, where the duty has been held not to exist. There are also dicta in such

cases which go further than was necessary for the determination of the particular

issues, which have caused the difficulty experienced by the Courts below. I

venture to say that in the branch of the law which deals with civil wrongs,

dependent in England at any rate entirely upon the application by judges of

general principles also *584 formulated by judges, it is of particular importance to

guard against the danger of stating propositions of law in wider terms than is

necessary, lest essential factors be omitted in the wider survey and the inherent

adaptability of English law be unduly restricted. For this reason it is very

necessary in considering reported cases in the law of torts that the actual decision

alone should carry authority, proper weight, of course, being given to the dicta of

the judges.

In my opinion several decided cases support the view that in such a case as the

present the manufacturer owes a duty to the consumer to be careful. A direct

authority is George v. Skivington. [FN86] That was a decision on a demurrer to a

declaration which averred that the defendant professed to sell a hairwash made

opened by the actual consumer. There can be no inspection by any purchaser

and no reasonable preliminary inspection by the consumer. Negligently, in the

course of preparation, he allows the contents to be mixed with poison. It is said

that the law of England and Scotland is that the poisoned consumer has no

remedy against the negligent manufacturer. If this were the result of the

authorities, I should consider the result a grave defect in the law, and so contrary

to principle that I should hesitate long before following any decision to that effect

which had not the authority of this House. I would point out that, in the assumed

state of the authorities, not only would the consumer have no remedy against

the *583 manufacturer, he would have none against any one else, for in the

circumstances alleged there would be no evidence of negligence against any one

other than the manufacturer; and, except in the case of a consumer who was

also a purchaser, no contract and no warranty of fitness, and in the case of the

purchase of a specific article under its patent or trade name, which might well be

the case in the purchase of some articles of food or drink, no warranty protecting

even the purchaser-consumer. There are other instances than of articles of food

and drink where goods are sold intended to be used immediately by the

consumer, such as many forms of goods sold for cleaning purposes, where the

same liability must exist. The doctrine supported by the decision below would not

only deny a remedy to the consumer who was injured by consuming bottled beer

or chocolates poisoned by the negligence of the manufacturer, but also to the

user of what should be a harmless proprietary medicine, an ointment, a soap, a

cleaning fluid or cleaning powder. I confine myself to articles of common

household use, where every one, including the manufacturer, knows that the

articles will be used by other persons than the actual ultimate purchaser -

namely, by members of his family and his servants, and in some cases his

guests. I do not think so in of our jurisprudence as to suppose that its principles

are so remote from the ordinary needs of civilized society and the ordinary

claims it makes upon its members as to deny a legal remedy where there is so

obviously a social wrong.

FN80 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

FN81 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491, 497, 504.

FN82 11 Q. B. D. 503, 509.

FN83 11 Q. B. D. 503, 510.

FN84 [1893] 1 Q. B. 491.

FN85 11 Q. B. D. 503.

It will be found, I think, on examination that there is no case in which the

circumstances have been such as I have just suggested where the liability has

been negatived. There are numerous cases, where the relations were much more

remote, where the duty has been held not to exist. There are also dicta in such

cases which go further than was necessary for the determination of the particular

issues, which have caused the difficulty experienced by the Courts below. I

venture to say that in the branch of the law which deals with civil wrongs,

dependent in England at any rate entirely upon the application by judges of

general principles also *584 formulated by judges, it is of particular importance to

guard against the danger of stating propositions of law in wider terms than is

necessary, lest essential factors be omitted in the wider survey and the inherent

adaptability of English law be unduly restricted. For this reason it is very

necessary in considering reported cases in the law of torts that the actual decision

alone should carry authority, proper weight, of course, being given to the dicta of

the judges.

In my opinion several decided cases support the view that in such a case as the

present the manufacturer owes a duty to the consumer to be careful. A direct

authority is George v. Skivington. [FN86] That was a decision on a demurrer to a

declaration which averred that the defendant professed to sell a hairwash made

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

by himself, and that the plaintiff Joseph George bought a bottle, to be used by his

wife, the plaintiff Emma George, as the defendant then knew, and that the

defendant had so negligently conducted himself in preparing and selling the

hairwash that it was unfit for use, whereby the female plaintiff was injured. Kelly

C.B. said that there was no question of warranty, but whether the chemist was

liable in an action on the case for unskilfulness and negligence in the

manufacture of it. "Unquestionably there was such a duty towards the purchaser,

and it extends, in my judgment, to the person for whose use the vendor knew the

compound was purchased." Pigott and Cleasby BB. put their judgments on the

same ground. I venture to think that Cotton L.J., in Heaven v. Pender [FN87],

misinterprets Cleasby B.'s judgment in the reference to Langridge v. Levy. [FN88]

Cleasby B. appears to me to make it plain that in his opinion the duty to take

reasonable care can be substituted for the duty which existed in Langridge v.

Levy [FN89] not to defraud. It is worth noticing that George v. Skivington

[FN90]was referred to by Cleasby B. himself, sitting as a member of the Court of

Exchequer Chamber in Francis v. Cockrell [FN91], and was recognized by him as

based on an ordinary duty to take care. It was also affirmed by Brett M.R. *585 in

Cunnington v. Great Northern Ry. Co. [FN92], decided on July 2 at a date

between the argument and the judgment in Heaven v. Pender [FN93], though, as

in that case the Court negatived any breach of duty, the expression of opinion is

not authoritative. The existence of the duty contended for is also supported by

Hawkins v. Smith [FN94], where a dock labourer in the employ of the dock

company was injured by a defective sack which had been hired by the

consignees from the defendant, who knew the use to which it was to be put, and

had been provided by the consignees for the use of the dock company, who had

been employed by them to unload the ship on the dock company's premises. The

Divisional Court, Day and Lawrance JJ., held the defendant liable for negligence.

Similarly, in Elliott v. Hall [FN95], the defendants, colliery owners, consigned coal

to the plaintiff's employers, coal merchants, in a truck hired by the defendants

from a wagon company. The plaintiff was injured in the course of unloading the

coal by reason of the defective condition of the truck, and was held by a

Divisional Court, Grove and A. L. Smith JJ., entitled to recover on the ground of

the defendants' breach of duty to see that the truck was not in a dangerous

condition. It is to be noticed that in neither case was the defective chattel in the

defendants' occupation, possession or control, or on their premises, while in the

latter case it was not even their property. It is sometimes said that the liability in

these cases depends upon an invitation by the defendant to the plaintiff to use

his chattel. I do not find the decisions expressed to be based upon this ground,

but rather upon the knowledge that the plaintiff in the course of the

contemplated use of the chattel would use it; and the supposed invitation

appears to me to be in many cases a fiction, and merely a form of expressing the

direct relation between supplier and user which gives rise to the duty to take

care. A very recent case which has the authority of this House is Oliver v. Saddler

& Co. [FN96]In that case a firm *586 of stevedores employed to unload a cargo

of maize in bags provided the rope slings by which the cargo was raised to the

ship's deck by their own men using the ship's tackle, and then transported to the

dockside by the shore porters, of whom the plaintiff was one. The porters relied

on examination by the stevedores and had themselves no opportunity of

examination. In these circumstances this House, reversing the decision of the

First Division, held that there was a duty owed by the stevedore company to the

porters to see that the slings were fit for use, and restored the judgment of the

Lord Ordinary, Lord Morison, in favour of the pursuer. I find no trace of the

doctrine of invitation in the opinions expressed in this House, of which mine was

one: the decision was based upon the fact that the direct relations established,

especially the circumstance that the injured porter had no opportunity of

independent examination, gave rise to a duty to be careful.

by himself, and that the plaintiff Joseph George bought a bottle, to be used by his

wife, the plaintiff Emma George, as the defendant then knew, and that the

defendant had so negligently conducted himself in preparing and selling the

hairwash that it was unfit for use, whereby the female plaintiff was injured. Kelly

C.B. said that there was no question of warranty, but whether the chemist was

liable in an action on the case for unskilfulness and negligence in the

manufacture of it. "Unquestionably there was such a duty towards the purchaser,

and it extends, in my judgment, to the person for whose use the vendor knew the

compound was purchased." Pigott and Cleasby BB. put their judgments on the

same ground. I venture to think that Cotton L.J., in Heaven v. Pender [FN87],

misinterprets Cleasby B.'s judgment in the reference to Langridge v. Levy. [FN88]

Cleasby B. appears to me to make it plain that in his opinion the duty to take

reasonable care can be substituted for the duty which existed in Langridge v.

Levy [FN89] not to defraud. It is worth noticing that George v. Skivington

[FN90]was referred to by Cleasby B. himself, sitting as a member of the Court of

Exchequer Chamber in Francis v. Cockrell [FN91], and was recognized by him as

based on an ordinary duty to take care. It was also affirmed by Brett M.R. *585 in

Cunnington v. Great Northern Ry. Co. [FN92], decided on July 2 at a date

between the argument and the judgment in Heaven v. Pender [FN93], though, as

in that case the Court negatived any breach of duty, the expression of opinion is

not authoritative. The existence of the duty contended for is also supported by

Hawkins v. Smith [FN94], where a dock labourer in the employ of the dock

company was injured by a defective sack which had been hired by the

consignees from the defendant, who knew the use to which it was to be put, and

had been provided by the consignees for the use of the dock company, who had

been employed by them to unload the ship on the dock company's premises. The

Divisional Court, Day and Lawrance JJ., held the defendant liable for negligence.

Similarly, in Elliott v. Hall [FN95], the defendants, colliery owners, consigned coal

to the plaintiff's employers, coal merchants, in a truck hired by the defendants

from a wagon company. The plaintiff was injured in the course of unloading the

coal by reason of the defective condition of the truck, and was held by a

Divisional Court, Grove and A. L. Smith JJ., entitled to recover on the ground of

the defendants' breach of duty to see that the truck was not in a dangerous

condition. It is to be noticed that in neither case was the defective chattel in the

defendants' occupation, possession or control, or on their premises, while in the

latter case it was not even their property. It is sometimes said that the liability in

these cases depends upon an invitation by the defendant to the plaintiff to use

his chattel. I do not find the decisions expressed to be based upon this ground,

but rather upon the knowledge that the plaintiff in the course of the

contemplated use of the chattel would use it; and the supposed invitation

appears to me to be in many cases a fiction, and merely a form of expressing the

direct relation between supplier and user which gives rise to the duty to take

care. A very recent case which has the authority of this House is Oliver v. Saddler

& Co. [FN96]In that case a firm *586 of stevedores employed to unload a cargo

of maize in bags provided the rope slings by which the cargo was raised to the

ship's deck by their own men using the ship's tackle, and then transported to the

dockside by the shore porters, of whom the plaintiff was one. The porters relied

on examination by the stevedores and had themselves no opportunity of

examination. In these circumstances this House, reversing the decision of the

First Division, held that there was a duty owed by the stevedore company to the

porters to see that the slings were fit for use, and restored the judgment of the

Lord Ordinary, Lord Morison, in favour of the pursuer. I find no trace of the

doctrine of invitation in the opinions expressed in this House, of which mine was

one: the decision was based upon the fact that the direct relations established,

especially the circumstance that the injured porter had no opportunity of

independent examination, gave rise to a duty to be careful.

12

FN86 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN87 11 Q. B. D. 517.

FN88 4 M. & W. 337.

FN89 4 M. & W. 337.

FN90 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN91 L. R. 5 Q. B. 501, 515.

FN92 (1883) 49 L. T. 392.

FN93 11 Q. B. D. 517.

FN94 (1896) 12 Times L. R. 532.

FN95 (1885) 15 Q. B. D. 315.

FN96 [1929] A. C. 584.

I should not omit in this review of cases the decision in Grote v. Chester and

Holyhead Ry. [FN97] That was an action on the case in which it was alleged that

the defendants had constructed a bridge over the Dee on their railway and had

licensed the use of the bridge to the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway to carry

passengers over it, and had so negligently constructed the bridge that the

plaintiff, a passenger of the last named railway, had been injured by the falling of

the bridge. At the trial before Vaughan Williams J. the judge had directed the jury

that the plaintiff was entitled to recover if the bridge was not constructed with

reasonable care and skill. On a motion for a new trial the Attorney-General (Sir

John Jervis) contended that there was misdirection, for the defendants were only

liable for negligence, and the jury might have understood that there was an

absolute liability. The Court of Exchequer, after consulting the trial judge as to his

direction, refused the rule. This case is said by Kelly C.B., in Francis v. Cockrell

[FN98] in the Exchequer Chamber, to have been decided upon an implied

contract with every person lawfully using the bridge that it was *587 reasonably

fit for the purpose. I can find no trace of such a ground in the pleading or in the

argument or judgment. It is true that the defendants were the owners and

occupiers of the bridge. The law as to the liability to invitees and licensees had

not then been developed. The case is interesting, because it is a simple action on

the case for negligence, and the Court upheld the duty to persons using the

bridge to take reasonable care that the bridge was safe.

FN97 (1848) 2 Ex. 251.

FN98 L. R. 5 Q. B. 505.

It now becomes necessary to consider the cases which have been referred to in

the Courts below as laying down the proposition that no duty to take care is owed

to the consumer in such a case as this.

In Dixon v. Bell [FN99], the defendant had left a loaded gun at his lodgings and

sent his servant, a mulatto girl aged about thirteen or fourteen, for the gun,

asking the landlord to remove the priming and give it her. The landlord did

remove the priming and gave it to the girl, who later levelled it at the plaintiff's

small son, drew the trigger and injured the boy. The action was in case for

negligently entrusting the young servant with the gun. The jury at the trial before

Lord Ellenborough had returned a verdict for the plaintiff. A motion by Sir William

Garrow (Attorney-General) for a new trial was dismissed by the Court, Lord

Ellenborough and Bayley J., the former remarking that it was incumbent on the

defendant, who by charging the gun had made it capable of doing mischief, to

render it safe and innoxious.

FN99 5 M. & S. 198.

In Langridge v. Levy [FN100] the action was in case, and the declaration alleged

that the defendant, by falsely and fraudulently warranting a gun to have been

made by Nock and to be a good, safe, and secure gun, sold the gun to the

FN86 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN87 11 Q. B. D. 517.

FN88 4 M. & W. 337.

FN89 4 M. & W. 337.

FN90 L. R. 5 Ex. 1.

FN91 L. R. 5 Q. B. 501, 515.

FN92 (1883) 49 L. T. 392.

FN93 11 Q. B. D. 517.

FN94 (1896) 12 Times L. R. 532.

FN95 (1885) 15 Q. B. D. 315.

FN96 [1929] A. C. 584.

I should not omit in this review of cases the decision in Grote v. Chester and

Holyhead Ry. [FN97] That was an action on the case in which it was alleged that

the defendants had constructed a bridge over the Dee on their railway and had

licensed the use of the bridge to the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway to carry

passengers over it, and had so negligently constructed the bridge that the

plaintiff, a passenger of the last named railway, had been injured by the falling of

the bridge. At the trial before Vaughan Williams J. the judge had directed the jury

that the plaintiff was entitled to recover if the bridge was not constructed with

reasonable care and skill. On a motion for a new trial the Attorney-General (Sir

John Jervis) contended that there was misdirection, for the defendants were only

liable for negligence, and the jury might have understood that there was an

absolute liability. The Court of Exchequer, after consulting the trial judge as to his

direction, refused the rule. This case is said by Kelly C.B., in Francis v. Cockrell

[FN98] in the Exchequer Chamber, to have been decided upon an implied

contract with every person lawfully using the bridge that it was *587 reasonably

fit for the purpose. I can find no trace of such a ground in the pleading or in the

argument or judgment. It is true that the defendants were the owners and

occupiers of the bridge. The law as to the liability to invitees and licensees had

not then been developed. The case is interesting, because it is a simple action on

the case for negligence, and the Court upheld the duty to persons using the

bridge to take reasonable care that the bridge was safe.

FN97 (1848) 2 Ex. 251.

FN98 L. R. 5 Q. B. 505.

It now becomes necessary to consider the cases which have been referred to in

the Courts below as laying down the proposition that no duty to take care is owed

to the consumer in such a case as this.

In Dixon v. Bell [FN99], the defendant had left a loaded gun at his lodgings and

sent his servant, a mulatto girl aged about thirteen or fourteen, for the gun,

asking the landlord to remove the priming and give it her. The landlord did

remove the priming and gave it to the girl, who later levelled it at the plaintiff's

small son, drew the trigger and injured the boy. The action was in case for

negligently entrusting the young servant with the gun. The jury at the trial before

Lord Ellenborough had returned a verdict for the plaintiff. A motion by Sir William

Garrow (Attorney-General) for a new trial was dismissed by the Court, Lord

Ellenborough and Bayley J., the former remarking that it was incumbent on the

defendant, who by charging the gun had made it capable of doing mischief, to

render it safe and innoxious.

FN99 5 M. & S. 198.

In Langridge v. Levy [FN100] the action was in case, and the declaration alleged

that the defendant, by falsely and fraudulently warranting a gun to have been