Farming Practices in Clove Tree Based Cropping Systems, Madagascar

VerifiedAdded on 2022/07/05

|21

|9626

|29

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a study conducted in the Fenerive Est district of Madagascar, focusing on the assessment of local knowledge and agricultural practices within clove tree-based cropping systems. The research investigates how farmers, particularly the Bestimisaraka, manage their clove tree plantations and diversify their crops to improve food security. The study explores the influence of both internal and external factors, such as cyclones and price fluctuations, on farmers' decision-making processes regarding their farming systems. The methodology includes surveys, interviews, focus groups, and participatory rural appraisal methods to gather qualitative data. The findings reveal that farmers adopt different cropping systems based on land size, number of clove trees, and other factors, including the need to produce enough rice for their families. The research identifies the socio-economic backgrounds of the farmers, including their age, gender, education level, and land rights, as significant variables influencing their farming practices. The report also analyzes the evolution of clove tree cropping systems, from monocultures to parklands and agroforestry systems, highlighting the importance of local knowledge in adapting to environmental and socio-economic changes.

1

ASSESSMENT OF LOCAL KNOWLEDGE AND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES IN

THE CLOVE TREE BASED CROPPING SYSTEMS IN THE FENERIVE EST

DITRICT, MADAGASCAR

Marta PANCO, SupAgro Montpellier

Abstract

In the study completed on the east coast of Madagascar, farmers rely on the clove tree products

to assure household food security. The Malagasy farmers are changing their farming practices in

the clove crop production and diversifying species to improve their farming systems. The

assessment of different types of knowledge and practices can help to acknowledge the

preferences for a certain type of cropping system. The decision making process is nevertheless

influenced by the internal and external factors, like cyclones and price fluctuations. The research

took place in 2 villages in the Fenerive Est district. The diversity of farming systems practiced in

the villages and parklands especially denotes farmers’ needs for food crops, while the

agroforestry systems can assure a broader range of income.

Key words: agroforestry system, food security, clove tree products, Fenerive Est

Introduction

The clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum) is one of the most important cash crops in the eastern

region of Madagascar and has been cultivated for more than a century (Jahiel, 2011). Originally

from the Molusc Island in Indonesia the clove tree was introduced on the Island Saint Marie of

Madagascar in 1822 by the Society Albran-Carayon-Hugot (Dufornet, 1968). Since its

introduction on the eastern coast of Madagascar in 1900 (Jahiel, 2011) the income generation

from the cloves played an important role for the Bestimisaraka farmers. Cloves not only

contribute to farmers’ livelihoods, but also to the national economical output. Madagascar is the

second biggest producer of cloves and essential oil after Indonesia and the number one exporter

(MCM, 2010; FAO, 2012) providing 7.6 % of global production. The region of Analajirofo,

which in direct translation means “clove trees forest”, achieved a production of 6718 tons in

2011 (FAO, 2012). This production is based on small scale farming where more than 30000 local

farmers exist in the district of Fenerive Est (Ministry of Agriculture, 2012). According to the

previous studies regarding clove tree based cropping systems in Madagascar (Michels et al.,

2011; Penot et al., 2011) the current plantations are issued from the first colonial implantations in

the 1930s and 1960s on the eastern coast. The aging trees and their overexploitation and lack of

replanting between 1960s and 2000s have lead to the alteration of the plantations structure and

function (Penot, 2011), as well as the fall of the production in the latter years (Michels et al,

2011). Their structure evolved from the monocropping systems to parklands and agroforestry

systems (AFS) after ecological hazards (cyclone) and socio-economic risks (price volatility,

human pressure). Monocropping systems are plantations sown with only one crop (the clove

ASSESSMENT OF LOCAL KNOWLEDGE AND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES IN

THE CLOVE TREE BASED CROPPING SYSTEMS IN THE FENERIVE EST

DITRICT, MADAGASCAR

Marta PANCO, SupAgro Montpellier

Abstract

In the study completed on the east coast of Madagascar, farmers rely on the clove tree products

to assure household food security. The Malagasy farmers are changing their farming practices in

the clove crop production and diversifying species to improve their farming systems. The

assessment of different types of knowledge and practices can help to acknowledge the

preferences for a certain type of cropping system. The decision making process is nevertheless

influenced by the internal and external factors, like cyclones and price fluctuations. The research

took place in 2 villages in the Fenerive Est district. The diversity of farming systems practiced in

the villages and parklands especially denotes farmers’ needs for food crops, while the

agroforestry systems can assure a broader range of income.

Key words: agroforestry system, food security, clove tree products, Fenerive Est

Introduction

The clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum) is one of the most important cash crops in the eastern

region of Madagascar and has been cultivated for more than a century (Jahiel, 2011). Originally

from the Molusc Island in Indonesia the clove tree was introduced on the Island Saint Marie of

Madagascar in 1822 by the Society Albran-Carayon-Hugot (Dufornet, 1968). Since its

introduction on the eastern coast of Madagascar in 1900 (Jahiel, 2011) the income generation

from the cloves played an important role for the Bestimisaraka farmers. Cloves not only

contribute to farmers’ livelihoods, but also to the national economical output. Madagascar is the

second biggest producer of cloves and essential oil after Indonesia and the number one exporter

(MCM, 2010; FAO, 2012) providing 7.6 % of global production. The region of Analajirofo,

which in direct translation means “clove trees forest”, achieved a production of 6718 tons in

2011 (FAO, 2012). This production is based on small scale farming where more than 30000 local

farmers exist in the district of Fenerive Est (Ministry of Agriculture, 2012). According to the

previous studies regarding clove tree based cropping systems in Madagascar (Michels et al.,

2011; Penot et al., 2011) the current plantations are issued from the first colonial implantations in

the 1930s and 1960s on the eastern coast. The aging trees and their overexploitation and lack of

replanting between 1960s and 2000s have lead to the alteration of the plantations structure and

function (Penot, 2011), as well as the fall of the production in the latter years (Michels et al,

2011). Their structure evolved from the monocropping systems to parklands and agroforestry

systems (AFS) after ecological hazards (cyclone) and socio-economic risks (price volatility,

human pressure). Monocropping systems are plantations sown with only one crop (the clove

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

tree). Parklands, or “parcs arbores” in French, are defined as associations involving a limited

number of a perennial crop (clove tree) with annual species (rice, cassava, sweet potato)

cultivated and grazed after (De Foresta & Michon, 1999). This cropping system resulting from

ancient clove tree monocrops (Penot et al., 2010), where clove tree canopies are spatially

scattered and permits the intercalation of food crops beneath the tree. Agroforestry systems are

land-use systems with a complex, dense, multi-strata structure comprising many perennial

species on the same land unit (Torquebiau, 2000).

This study is part of a EuropAid EU and African Union project, AFS4FOOD, which aims to

assess cash crops systems and their income contribution to food security of African farmers.

Together the International Center for Agricultural Research and Development (CIRAD) and

Horticultural and Technical Centre of Tamatave (CTHT) sought to gain a better understanding of

farmers’ agricultural knowledge and practices in the clove-tree based farming systems. While,

local knowledge regarding farm management holds a noteworthy role in overall farm

development, the decision making process is nevertheless influenced by the internal and external

factors, like cyclones and price fluctuations. Knowing how local knowledge and practices

influence the choice of the farmers for a farming system will allow analyzing the producers’

livelihood strategies. Therefore, the main research questions of this paper are (1) to identify local

knowledge and farming practices in the clove tree based cropping systems, (2) to analyze the

decision making process for different cropping systems, (3) to determine the driving forces for

each choice, and (4) to assess farmers livelihood strategies.

Materials and methods

Survey area

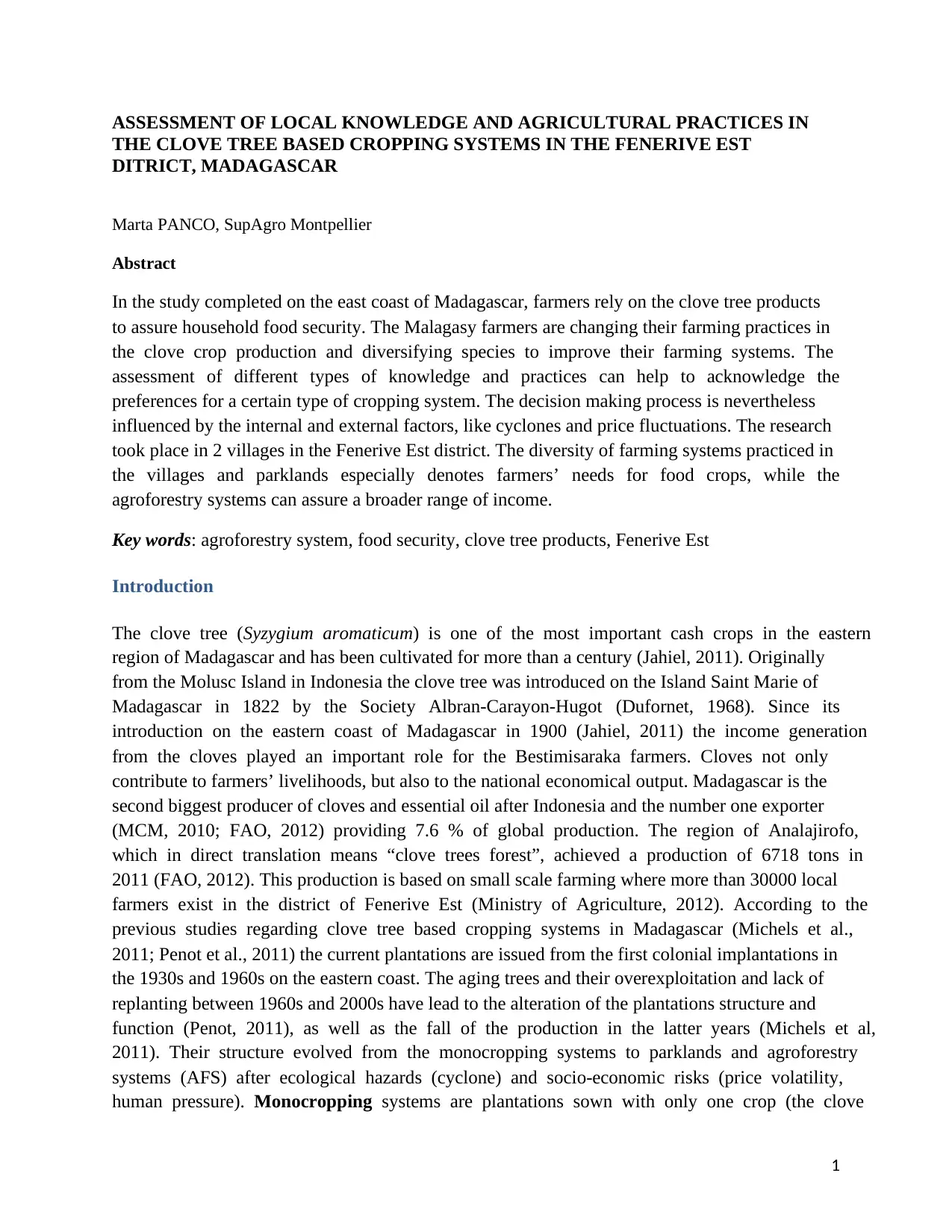

This paper presents the principal findings of the multidisciplinary survey conducted during a 4

month field study in Madagascar. The study was completed with Bestimisaraka farmers from

two communities in the clove-growing area, Fenerive Est district (17°22'50.76''S,

49°24’28.71”E) (Fig. 1). The village sample was based on previous surveys realized by the

CTHT in 2009 and 2010 in communes of Ambodimanga II, the fokontany (a sub-administrative

area compound of 2-3 villages) of Mahavanona, and Ambatohorana, the fokontany

Ambodihazinina. The geographical distance from the main town and markets (10 km and 25km,

respectively) and proximity to the coastline (4 km and 17km) was considered in the sample. The

annual rainfall in the region varies between 180 and 300 days per year, with the monthly average

precipitation from 80 to 160 mm during the wet season (October to April). In the dry season,

from April to September, there is less rainfall and the average temperature is 25°C (FIDA, 2006).

The landscape in the study area is predominantly characterized by lowland rice and hilly fields

covered with clove trees on the slopes varying from 20-120 m in elevation. The landscape has

been changing since the 1920s with the introduction of clove trees. Mixed clove farming is

tree). Parklands, or “parcs arbores” in French, are defined as associations involving a limited

number of a perennial crop (clove tree) with annual species (rice, cassava, sweet potato)

cultivated and grazed after (De Foresta & Michon, 1999). This cropping system resulting from

ancient clove tree monocrops (Penot et al., 2010), where clove tree canopies are spatially

scattered and permits the intercalation of food crops beneath the tree. Agroforestry systems are

land-use systems with a complex, dense, multi-strata structure comprising many perennial

species on the same land unit (Torquebiau, 2000).

This study is part of a EuropAid EU and African Union project, AFS4FOOD, which aims to

assess cash crops systems and their income contribution to food security of African farmers.

Together the International Center for Agricultural Research and Development (CIRAD) and

Horticultural and Technical Centre of Tamatave (CTHT) sought to gain a better understanding of

farmers’ agricultural knowledge and practices in the clove-tree based farming systems. While,

local knowledge regarding farm management holds a noteworthy role in overall farm

development, the decision making process is nevertheless influenced by the internal and external

factors, like cyclones and price fluctuations. Knowing how local knowledge and practices

influence the choice of the farmers for a farming system will allow analyzing the producers’

livelihood strategies. Therefore, the main research questions of this paper are (1) to identify local

knowledge and farming practices in the clove tree based cropping systems, (2) to analyze the

decision making process for different cropping systems, (3) to determine the driving forces for

each choice, and (4) to assess farmers livelihood strategies.

Materials and methods

Survey area

This paper presents the principal findings of the multidisciplinary survey conducted during a 4

month field study in Madagascar. The study was completed with Bestimisaraka farmers from

two communities in the clove-growing area, Fenerive Est district (17°22'50.76''S,

49°24’28.71”E) (Fig. 1). The village sample was based on previous surveys realized by the

CTHT in 2009 and 2010 in communes of Ambodimanga II, the fokontany (a sub-administrative

area compound of 2-3 villages) of Mahavanona, and Ambatohorana, the fokontany

Ambodihazinina. The geographical distance from the main town and markets (10 km and 25km,

respectively) and proximity to the coastline (4 km and 17km) was considered in the sample. The

annual rainfall in the region varies between 180 and 300 days per year, with the monthly average

precipitation from 80 to 160 mm during the wet season (October to April). In the dry season,

from April to September, there is less rainfall and the average temperature is 25°C (FIDA, 2006).

The landscape in the study area is predominantly characterized by lowland rice and hilly fields

covered with clove trees on the slopes varying from 20-120 m in elevation. The landscape has

been changing since the 1920s with the introduction of clove trees. Mixed clove farming is

3

common and is based on upland rice-cassava intercalated amidst clove trees. Food crops are

grown to meet the subsistence needs of the households, with any surplus sold on the market. The

cash crops (cloves, coffee, litchi and vanilla) contribute to family income, with cloves accounting

for 20-50 % of the cash income (Penot et al., 2011).

Sampling and data collection

The initial sample comprised four of farmers interviewed by an agent of CTHT in the first

village, Mahavanona. The next farmers were selected on the basis of “snowball” (Babbie, 2001)

method where farmers were asked to recommend other clove producers in the village.

Complementary sampling strategy was based on observation of the houses of these producers,

and the identification of wooden households, which, according to villagers symbolize relative

wealth from clove production.

The study employed qualitative collection methods (33 in-depth semi-structured interviews) and

focus group discussions (one in each village). Prior to the main survey, three pilot test of the

interview were taken for evaluation. The interviews were translated from French to Malagasy

and were held either in their homes or on the plots. Lastly, participatory rural appraisal (PRA)

methods were applied to supplement data collection (preference matrix), timeline and mapping

(Mikkelsen, 1995), active participatory observation and transect walks with key informants. PRA

offers the advantage of learning with and from rural people, interacting daily and directly, on the

Figure 1 Clove tree growing area in Madagascar. Source: a) Ministry of Agriculture, 2005; b) Michels, 2010)

common and is based on upland rice-cassava intercalated amidst clove trees. Food crops are

grown to meet the subsistence needs of the households, with any surplus sold on the market. The

cash crops (cloves, coffee, litchi and vanilla) contribute to family income, with cloves accounting

for 20-50 % of the cash income (Penot et al., 2011).

Sampling and data collection

The initial sample comprised four of farmers interviewed by an agent of CTHT in the first

village, Mahavanona. The next farmers were selected on the basis of “snowball” (Babbie, 2001)

method where farmers were asked to recommend other clove producers in the village.

Complementary sampling strategy was based on observation of the houses of these producers,

and the identification of wooden households, which, according to villagers symbolize relative

wealth from clove production.

The study employed qualitative collection methods (33 in-depth semi-structured interviews) and

focus group discussions (one in each village). Prior to the main survey, three pilot test of the

interview were taken for evaluation. The interviews were translated from French to Malagasy

and were held either in their homes or on the plots. Lastly, participatory rural appraisal (PRA)

methods were applied to supplement data collection (preference matrix), timeline and mapping

(Mikkelsen, 1995), active participatory observation and transect walks with key informants. PRA

offers the advantage of learning with and from rural people, interacting daily and directly, on the

Figure 1 Clove tree growing area in Madagascar. Source: a) Ministry of Agriculture, 2005; b) Michels, 2010)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

site (Chambers, 1990). Living in the village for the duration of the study permitted for ongoing

observation and informal discussions, which enhanced the depth of understanding of the local

context and the local social situation.

Trees inventories

The tree population was counted in 27 plots in the two villages. The parcels were measured using

a GPS device and QGIS application to determine the size with precision. Clove trees were

counted on each of the measured plot. In AFS, the other trees species were counted in order to

assess the biodiversity in the systems and their use. The typology of the clove tree based

cropping system identified in Madagascar by the Michels et al. (2011) and Penot et al. (2011)

was used in the survey to characterize the measured plots, the knowledge and use of the crops by

local population. The main uses of the plant species were identified through interviews with local

farmers. The species were then grouped into one of the following classes: edible, medicinal,

timber and other.

Triangulation

All the above methods were triangulated with the literature review realized beforehand and

ending with a final participant workshop to present the preliminary findings. The workshop was

prepared 3 days in advance and set in a “fady” day (a traditional custom where most of the

farmers respect the tradition of not working in the field on certain day). In both communities the

workshop comprised some of the interviewed farmers (even less in the second community where

people had a drawback attitude). During the presentation, they all agreed on the results and

confirmed our interpretation. However, the youth and women were more reticent in speaking up

and being active in the open conversation, limiting the feedback of the information.

Results

The most significant result of the study is the confirmation that local farmers adopt different

types of clove tree based cropping systems depending on factors which weighed more heavily

than knowledge, including land size and number of clove trees per plot. The diversification of

farming systems and the tree density is influenced by many factors (land size and availability,

family size and labour availability), and other farmers’ needs (produce enough rice to sustain

family’s food needs, other expenses). These drive farmers to plant or retain other trees or non-

tree crops to sustain and improve their family’s livelihoods. In this section we present the results

of the farmers’ knowledge and management practices on the clove tree plantations; their impact

on the evolution of clove tree cropping systems and the factors that determine these changes.

Socio-economic background of farmers

site (Chambers, 1990). Living in the village for the duration of the study permitted for ongoing

observation and informal discussions, which enhanced the depth of understanding of the local

context and the local social situation.

Trees inventories

The tree population was counted in 27 plots in the two villages. The parcels were measured using

a GPS device and QGIS application to determine the size with precision. Clove trees were

counted on each of the measured plot. In AFS, the other trees species were counted in order to

assess the biodiversity in the systems and their use. The typology of the clove tree based

cropping system identified in Madagascar by the Michels et al. (2011) and Penot et al. (2011)

was used in the survey to characterize the measured plots, the knowledge and use of the crops by

local population. The main uses of the plant species were identified through interviews with local

farmers. The species were then grouped into one of the following classes: edible, medicinal,

timber and other.

Triangulation

All the above methods were triangulated with the literature review realized beforehand and

ending with a final participant workshop to present the preliminary findings. The workshop was

prepared 3 days in advance and set in a “fady” day (a traditional custom where most of the

farmers respect the tradition of not working in the field on certain day). In both communities the

workshop comprised some of the interviewed farmers (even less in the second community where

people had a drawback attitude). During the presentation, they all agreed on the results and

confirmed our interpretation. However, the youth and women were more reticent in speaking up

and being active in the open conversation, limiting the feedback of the information.

Results

The most significant result of the study is the confirmation that local farmers adopt different

types of clove tree based cropping systems depending on factors which weighed more heavily

than knowledge, including land size and number of clove trees per plot. The diversification of

farming systems and the tree density is influenced by many factors (land size and availability,

family size and labour availability), and other farmers’ needs (produce enough rice to sustain

family’s food needs, other expenses). These drive farmers to plant or retain other trees or non-

tree crops to sustain and improve their family’s livelihoods. In this section we present the results

of the farmers’ knowledge and management practices on the clove tree plantations; their impact

on the evolution of clove tree cropping systems and the factors that determine these changes.

Socio-economic background of farmers

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

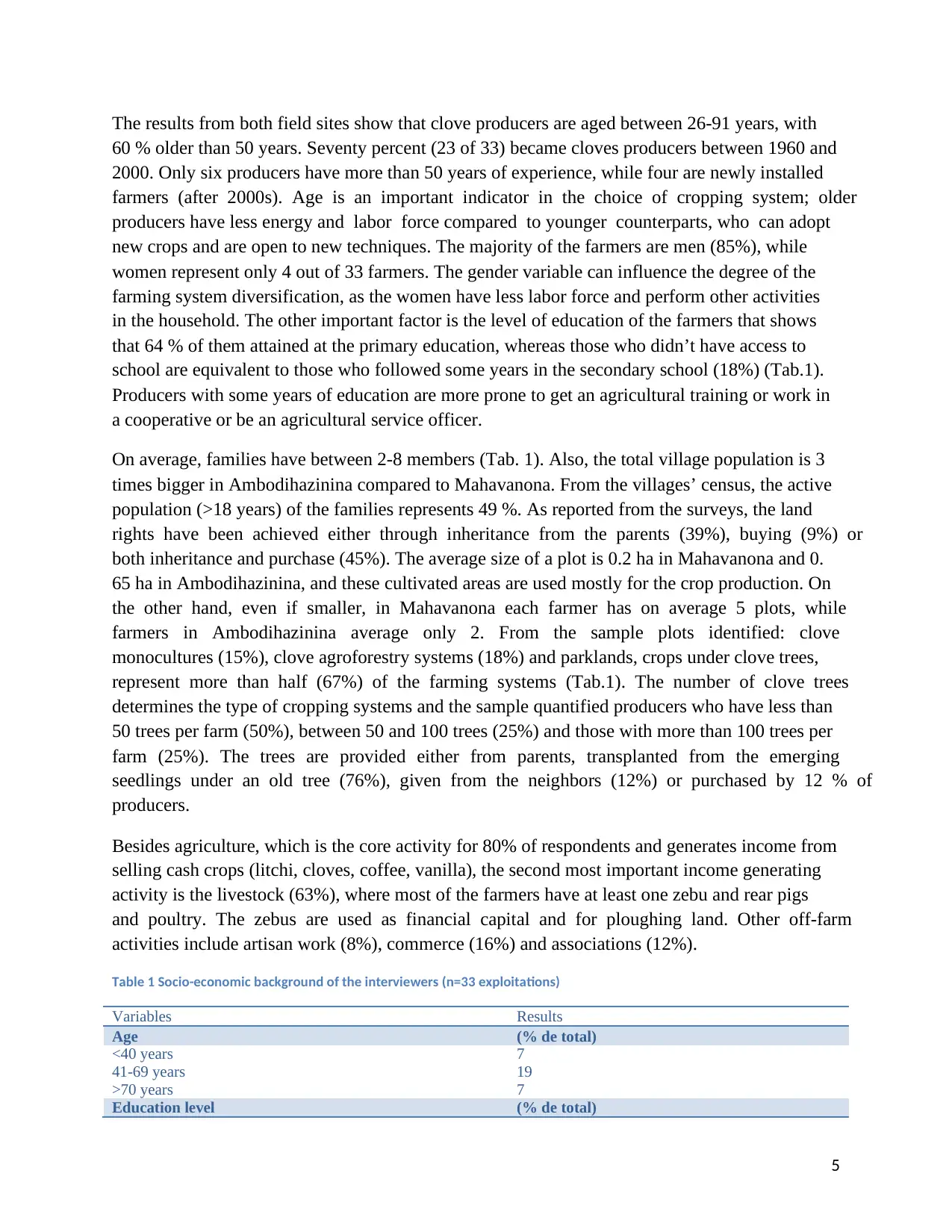

The results from both field sites show that clove producers are aged between 26-91 years, with

60 % older than 50 years. Seventy percent (23 of 33) became cloves producers between 1960 and

2000. Only six producers have more than 50 years of experience, while four are newly installed

farmers (after 2000s). Age is an important indicator in the choice of cropping system; older

producers have less energy and labor force compared to younger counterparts, who can adopt

new crops and are open to new techniques. The majority of the farmers are men (85%), while

women represent only 4 out of 33 farmers. The gender variable can influence the degree of the

farming system diversification, as the women have less labor force and perform other activities

in the household. The other important factor is the level of education of the farmers that shows

that 64 % of them attained at the primary education, whereas those who didn’t have access to

school are equivalent to those who followed some years in the secondary school (18%) (Tab.1).

Producers with some years of education are more prone to get an agricultural training or work in

a cooperative or be an agricultural service officer.

On average, families have between 2-8 members (Tab. 1). Also, the total village population is 3

times bigger in Ambodihazinina compared to Mahavanona. From the villages’ census, the active

population (>18 years) of the families represents 49 %. As reported from the surveys, the land

rights have been achieved either through inheritance from the parents (39%), buying (9%) or

both inheritance and purchase (45%). The average size of a plot is 0.2 ha in Mahavanona and 0.

65 ha in Ambodihazinina, and these cultivated areas are used mostly for the crop production. On

the other hand, even if smaller, in Mahavanona each farmer has on average 5 plots, while

farmers in Ambodihazinina average only 2. From the sample plots identified: clove

monocultures (15%), clove agroforestry systems (18%) and parklands, crops under clove trees,

represent more than half (67%) of the farming systems (Tab.1). The number of clove trees

determines the type of cropping systems and the sample quantified producers who have less than

50 trees per farm (50%), between 50 and 100 trees (25%) and those with more than 100 trees per

farm (25%). The trees are provided either from parents, transplanted from the emerging

seedlings under an old tree (76%), given from the neighbors (12%) or purchased by 12 % of

producers.

Besides agriculture, which is the core activity for 80% of respondents and generates income from

selling cash crops (litchi, cloves, coffee, vanilla), the second most important income generating

activity is the livestock (63%), where most of the farmers have at least one zebu and rear pigs

and poultry. The zebus are used as financial capital and for ploughing land. Other off-farm

activities include artisan work (8%), commerce (16%) and associations (12%).

Table 1 Socio-economic background of the interviewers (n=33 exploitations)

Variables Results

Age (% de total)

<40 years

41-69 years

>70 years

7

19

7

Education level (% de total)

The results from both field sites show that clove producers are aged between 26-91 years, with

60 % older than 50 years. Seventy percent (23 of 33) became cloves producers between 1960 and

2000. Only six producers have more than 50 years of experience, while four are newly installed

farmers (after 2000s). Age is an important indicator in the choice of cropping system; older

producers have less energy and labor force compared to younger counterparts, who can adopt

new crops and are open to new techniques. The majority of the farmers are men (85%), while

women represent only 4 out of 33 farmers. The gender variable can influence the degree of the

farming system diversification, as the women have less labor force and perform other activities

in the household. The other important factor is the level of education of the farmers that shows

that 64 % of them attained at the primary education, whereas those who didn’t have access to

school are equivalent to those who followed some years in the secondary school (18%) (Tab.1).

Producers with some years of education are more prone to get an agricultural training or work in

a cooperative or be an agricultural service officer.

On average, families have between 2-8 members (Tab. 1). Also, the total village population is 3

times bigger in Ambodihazinina compared to Mahavanona. From the villages’ census, the active

population (>18 years) of the families represents 49 %. As reported from the surveys, the land

rights have been achieved either through inheritance from the parents (39%), buying (9%) or

both inheritance and purchase (45%). The average size of a plot is 0.2 ha in Mahavanona and 0.

65 ha in Ambodihazinina, and these cultivated areas are used mostly for the crop production. On

the other hand, even if smaller, in Mahavanona each farmer has on average 5 plots, while

farmers in Ambodihazinina average only 2. From the sample plots identified: clove

monocultures (15%), clove agroforestry systems (18%) and parklands, crops under clove trees,

represent more than half (67%) of the farming systems (Tab.1). The number of clove trees

determines the type of cropping systems and the sample quantified producers who have less than

50 trees per farm (50%), between 50 and 100 trees (25%) and those with more than 100 trees per

farm (25%). The trees are provided either from parents, transplanted from the emerging

seedlings under an old tree (76%), given from the neighbors (12%) or purchased by 12 % of

producers.

Besides agriculture, which is the core activity for 80% of respondents and generates income from

selling cash crops (litchi, cloves, coffee, vanilla), the second most important income generating

activity is the livestock (63%), where most of the farmers have at least one zebu and rear pigs

and poultry. The zebus are used as financial capital and for ploughing land. Other off-farm

activities include artisan work (8%), commerce (16%) and associations (12%).

Table 1 Socio-economic background of the interviewers (n=33 exploitations)

Variables Results

Age (% de total)

<40 years

41-69 years

>70 years

7

19

7

Education level (% de total)

6

Nothing

Primary school

Secondary school

18

64

18

Household (number)

Average family size

Women

Men

<10 years

18-40 years

>40 years

4,18

2,03

2,15

0,62

2, 03

1, 53

Place of origin (% of total)

Village

Other villages

82

18

Average land surface (% of total)

Average farm land surface (ha)

<0,2

0,21-0,49

>0,5

0,46

51

27

22

Cropping system (% of total)

Monocrops

Parklands

Agroforestry systems

15

67

18

Nr of clove trees (% of total)

<50

50-100

>100

50

25

25

Other activities (% of total)

Artisanal

Livestock

Commerce

Farmers Organisation (PO)

Others (village president, communal counselor, secretary)

8

63

16

12

32

Diversity of cropping systems

Based on the typology of the clove cropping systems in the region and combined with the type of

producers identified in the sample the next farming systems are:

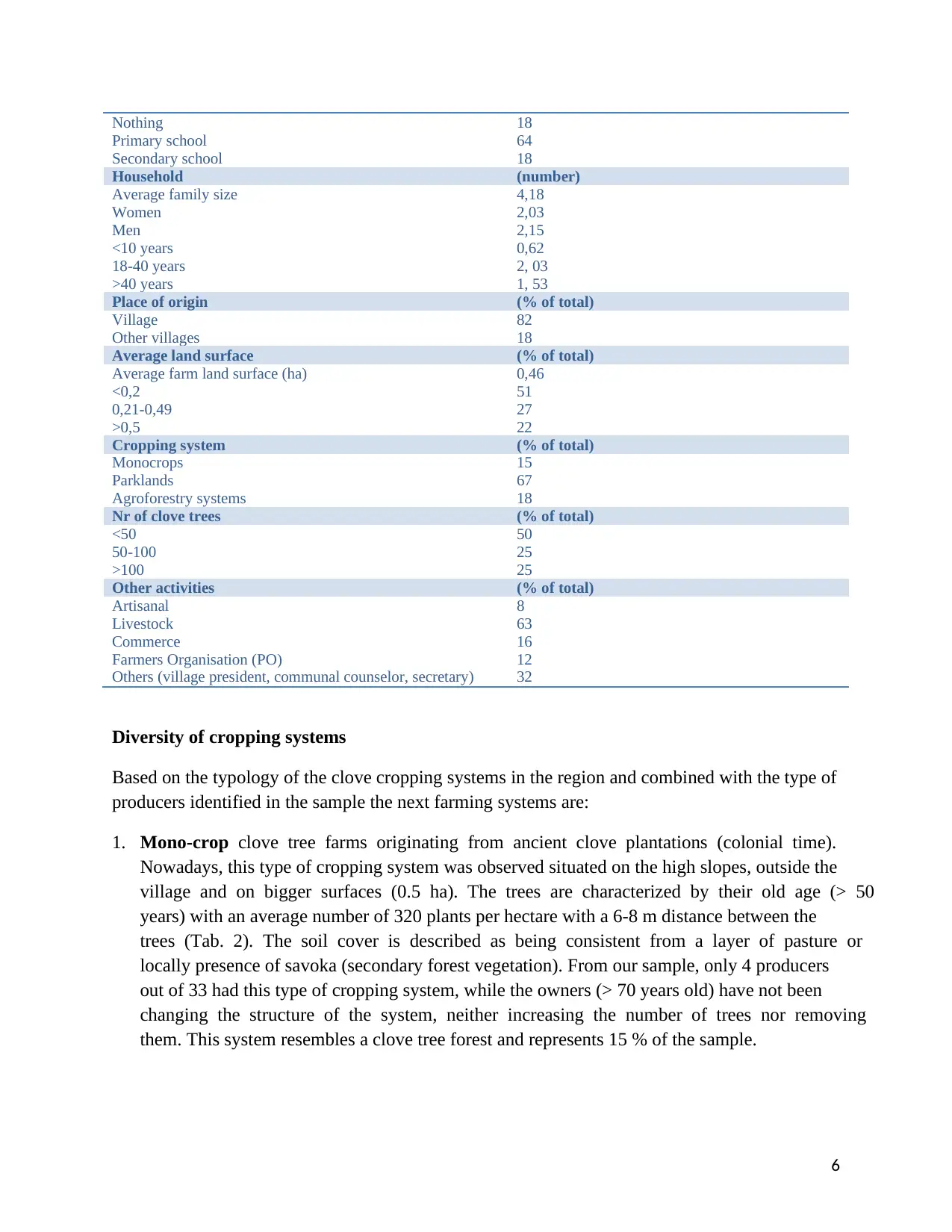

1. Mono-crop clove tree farms originating from ancient clove plantations (colonial time).

Nowadays, this type of cropping system was observed situated on the high slopes, outside the

village and on bigger surfaces (0.5 ha). The trees are characterized by their old age (> 50

years) with an average number of 320 plants per hectare with a 6-8 m distance between the

trees (Tab. 2). The soil cover is described as being consistent from a layer of pasture or

locally presence of savoka (secondary forest vegetation). From our sample, only 4 producers

out of 33 had this type of cropping system, while the owners (> 70 years old) have not been

changing the structure of the system, neither increasing the number of trees nor removing

them. This system resembles a clove tree forest and represents 15 % of the sample.

Nothing

Primary school

Secondary school

18

64

18

Household (number)

Average family size

Women

Men

<10 years

18-40 years

>40 years

4,18

2,03

2,15

0,62

2, 03

1, 53

Place of origin (% of total)

Village

Other villages

82

18

Average land surface (% of total)

Average farm land surface (ha)

<0,2

0,21-0,49

>0,5

0,46

51

27

22

Cropping system (% of total)

Monocrops

Parklands

Agroforestry systems

15

67

18

Nr of clove trees (% of total)

<50

50-100

>100

50

25

25

Other activities (% of total)

Artisanal

Livestock

Commerce

Farmers Organisation (PO)

Others (village president, communal counselor, secretary)

8

63

16

12

32

Diversity of cropping systems

Based on the typology of the clove cropping systems in the region and combined with the type of

producers identified in the sample the next farming systems are:

1. Mono-crop clove tree farms originating from ancient clove plantations (colonial time).

Nowadays, this type of cropping system was observed situated on the high slopes, outside the

village and on bigger surfaces (0.5 ha). The trees are characterized by their old age (> 50

years) with an average number of 320 plants per hectare with a 6-8 m distance between the

trees (Tab. 2). The soil cover is described as being consistent from a layer of pasture or

locally presence of savoka (secondary forest vegetation). From our sample, only 4 producers

out of 33 had this type of cropping system, while the owners (> 70 years old) have not been

changing the structure of the system, neither increasing the number of trees nor removing

them. This system resembles a clove tree forest and represents 15 % of the sample.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

2. The parkland cropping system is land where farmers develop annual crops under a clove

tree cover. The main priority of the farmers is to meet the family’s basic food needs. This

cropping system evolved from the monocropping systems of the 1960s have been exposed to

exogenous factors, like cyclones that removed some trees, or human pressure and clove

prices that determined locals to pull out clove trees. As a result, the trees have become

scattered on the agricultural surface with a distance between them from 2 to 12 m and are

spread irregularly on the plot (on average 150 clove trees per hectare) (Tab. 2). There are two

different types of parkland systems: some of the trees are issued from the initial vegetation

from inherited lands with trees aged more than 40 years, this is the type of residual parkland;

and second system is characterized by clove trees planted recently on the hilly landscapes

among the upland rice. The parkland plots have an average surface of 0.31 ha and belong to

different types of producers because of the big share of this type of cropping system (67 %).

The annual crops (rice, sweet potato, cassava or sugar cane) intercalated beneath the canopy

are following a general rotation of 2 years rice, 2 years of cassava intercropped with sweet

potatoes followed by a fallow for 5-6 years, used for animal grazing by the producers who

have zebus. Although the residual parkland belongs to the type of producers over 60 years

old, the second category of younger producers (or newly installed) have showed a more open

attitude to adopt improved techniques and increasing high value cash crops.

3. The clove tree agroforestry system (AFS) in our sample has surfaces range between 0.02

ha- 0.37 ha with a tree density from 100-250 clove trees per hectare (Tab. 2). The main

characteristic is that farmers adopt a diversification strategy (Penot, 2011) and is more

economically efficient, is very divers from farmer to farmer and even within the plots the

diversity of the crops. In our sample, we identified 2 other sub-categories:

- Simple AFS contain 2 main perennial crops covering more than 85% of the sole and

where the clove trees represent 46 % of the association with 38 % coffee and coconut tree

delimiting the plot. In this type belongs only one plot of a farmer.

- Complex agroforestry systems are a combination of clove trees mainly with other fruits

trees (Mangoes, Jack fruits and Coconuts), timber trees. This cropping system is

representing a dense mix of diverse trees, resembling a forest.

Table 2 Characteristics of clove tree cropping systems

Type of cropping system

Variables

Monospecific AFS Parkland

Surface (ha) 0, 49 0, 25 0,31

Nr of plots per producer 3,25 4,22 3,27

Nr of inherited clove trees per plot 32 20 19

Nr of planted clove trees per plot 92 65 41

Source: personal survey (2013)

2. The parkland cropping system is land where farmers develop annual crops under a clove

tree cover. The main priority of the farmers is to meet the family’s basic food needs. This

cropping system evolved from the monocropping systems of the 1960s have been exposed to

exogenous factors, like cyclones that removed some trees, or human pressure and clove

prices that determined locals to pull out clove trees. As a result, the trees have become

scattered on the agricultural surface with a distance between them from 2 to 12 m and are

spread irregularly on the plot (on average 150 clove trees per hectare) (Tab. 2). There are two

different types of parkland systems: some of the trees are issued from the initial vegetation

from inherited lands with trees aged more than 40 years, this is the type of residual parkland;

and second system is characterized by clove trees planted recently on the hilly landscapes

among the upland rice. The parkland plots have an average surface of 0.31 ha and belong to

different types of producers because of the big share of this type of cropping system (67 %).

The annual crops (rice, sweet potato, cassava or sugar cane) intercalated beneath the canopy

are following a general rotation of 2 years rice, 2 years of cassava intercropped with sweet

potatoes followed by a fallow for 5-6 years, used for animal grazing by the producers who

have zebus. Although the residual parkland belongs to the type of producers over 60 years

old, the second category of younger producers (or newly installed) have showed a more open

attitude to adopt improved techniques and increasing high value cash crops.

3. The clove tree agroforestry system (AFS) in our sample has surfaces range between 0.02

ha- 0.37 ha with a tree density from 100-250 clove trees per hectare (Tab. 2). The main

characteristic is that farmers adopt a diversification strategy (Penot, 2011) and is more

economically efficient, is very divers from farmer to farmer and even within the plots the

diversity of the crops. In our sample, we identified 2 other sub-categories:

- Simple AFS contain 2 main perennial crops covering more than 85% of the sole and

where the clove trees represent 46 % of the association with 38 % coffee and coconut tree

delimiting the plot. In this type belongs only one plot of a farmer.

- Complex agroforestry systems are a combination of clove trees mainly with other fruits

trees (Mangoes, Jack fruits and Coconuts), timber trees. This cropping system is

representing a dense mix of diverse trees, resembling a forest.

Table 2 Characteristics of clove tree cropping systems

Type of cropping system

Variables

Monospecific AFS Parkland

Surface (ha) 0, 49 0, 25 0,31

Nr of plots per producer 3,25 4,22 3,27

Nr of inherited clove trees per plot 32 20 19

Nr of planted clove trees per plot 92 65 41

Source: personal survey (2013)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

Nevertheless, the clove tree based cropping systems are so divers that each farmer can have

either one of these typologies or all of them spread on many plots. The limited sample cannot

confirm that the older farmers have only monocrop systems and the younger farmers only AFS

(Fig. 2). In the household survey, as observed in the table above, the monocropping systems have

had a bigger share of the plantation, land size and with a higher number of clove trees per

hectare.

Farmers’ knowledge of clove tree and origins and practices

Following the description of clove tree cropping systems in the area of study two different types

of knowledge and management practices of the clove trees were identified. The local knowledge

appears as an important source of information to understand the change of practices and

landscapes. From the interviews, 79 % of the producers asserted they learned how to plant,

maintain and harvest cloves and leaves from their parents, passed on through orally from

generation to generation. Apart from their parents, this knowledge comes from neighbors (12%)

and one had learned it from his grand-parents (3%). Some of the farmers (6%) did not know the

plant requirements from the beginning (water, soil, shadow and light), nor were they aware of

better and less favorable associations within the plots (annual or perennial crops); these farmers

achieved their knowledge about the clove tree cropping system from personal observation.

This local knowledge appeared together with the spread of clove trees in the villages. The

traditional knowledge, received from the parents or other farmers with more authority, results in

easier adaptations in term of clove tree management. All of the farmers confirmed that they rely

more on the advice of family members and they do not use compost in traditional system

management, which is recommended in the improved plantation (Maistre, 1964, Michels, 2011),

neither the distance between the trees; for example, they do not respect the size of the hole dug to

deposit the compost around the tree, nor the distance.

On the other hand, according to farmers, there is another “innovative” method of plantation,

brought by agricultural extension service of the state government and international organization.

The most important are: Operation Pepper-Coffee-clove (1960s) and Agricultural extension

services (1960s); PPRR and CTHT (2000s)). Producers asserted that this type of formal and

technical information is concerning the practices from creation of the clove tree nursery and tree

management as follows:

• For the nursery: the seeds need to be soaked in the water for 3 days in order to start the

germination process

• For the transplantation of a new seedling: the new place has to be prioritized for weeding

• The creation of the hole should respect the measures: 60*60cm and 1m deep

• Compost application is recommended; and could be a mix of the inversed shallow layer

from the soil surface with the dried leaves and herbs

• Distance to respect between the trees: 7-8 m

• Need for shade for the immaturity period up to 3 years

Nevertheless, the clove tree based cropping systems are so divers that each farmer can have

either one of these typologies or all of them spread on many plots. The limited sample cannot

confirm that the older farmers have only monocrop systems and the younger farmers only AFS

(Fig. 2). In the household survey, as observed in the table above, the monocropping systems have

had a bigger share of the plantation, land size and with a higher number of clove trees per

hectare.

Farmers’ knowledge of clove tree and origins and practices

Following the description of clove tree cropping systems in the area of study two different types

of knowledge and management practices of the clove trees were identified. The local knowledge

appears as an important source of information to understand the change of practices and

landscapes. From the interviews, 79 % of the producers asserted they learned how to plant,

maintain and harvest cloves and leaves from their parents, passed on through orally from

generation to generation. Apart from their parents, this knowledge comes from neighbors (12%)

and one had learned it from his grand-parents (3%). Some of the farmers (6%) did not know the

plant requirements from the beginning (water, soil, shadow and light), nor were they aware of

better and less favorable associations within the plots (annual or perennial crops); these farmers

achieved their knowledge about the clove tree cropping system from personal observation.

This local knowledge appeared together with the spread of clove trees in the villages. The

traditional knowledge, received from the parents or other farmers with more authority, results in

easier adaptations in term of clove tree management. All of the farmers confirmed that they rely

more on the advice of family members and they do not use compost in traditional system

management, which is recommended in the improved plantation (Maistre, 1964, Michels, 2011),

neither the distance between the trees; for example, they do not respect the size of the hole dug to

deposit the compost around the tree, nor the distance.

On the other hand, according to farmers, there is another “innovative” method of plantation,

brought by agricultural extension service of the state government and international organization.

The most important are: Operation Pepper-Coffee-clove (1960s) and Agricultural extension

services (1960s); PPRR and CTHT (2000s)). Producers asserted that this type of formal and

technical information is concerning the practices from creation of the clove tree nursery and tree

management as follows:

• For the nursery: the seeds need to be soaked in the water for 3 days in order to start the

germination process

• For the transplantation of a new seedling: the new place has to be prioritized for weeding

• The creation of the hole should respect the measures: 60*60cm and 1m deep

• Compost application is recommended; and could be a mix of the inversed shallow layer

from the soil surface with the dried leaves and herbs

• Distance to respect between the trees: 7-8 m

• Need for shade for the immaturity period up to 3 years

9

• Mulching of trees with the fallen dry leaves

• Prunning to facilitate the canopy development.

The survey showed that even if 48% of the farmers (16 out of 33) know about the improved

techniques, only 68 % from those who have this knowledge actually applied it on their field due

to the availability of land or time. The labour demand and the time availability for plantation is a

limiting factor for the adaptation of these improved techniques. According to farmers who used

this technique, one man can plant only 20 trees in one day with the improved method compared

to 100 trees with the traditional method. On the other hand, this method has some visible

advantages: clove trees planted grow faster and become productive after 7-8 years compared to

10 years for those planted with the traditional method. From the interviews, farmers received this

type of innovative information after they had already achieved local traditional methods by their

parents or neighbors. Farmers who implemented innovative methods (7 out of 33) are the ones

who are younger (less than 50 years), have still some land available, and have the objective of

improving their livelihoods or have been incited by the national or international development

programs.

In the both villages the share of the type of knowledge differs. More than 70 % of the producers

in the village of Mahavanona, which is closer to the city, have access to the agricultural training

compared to only 29 % of the producers from the remote community. Also, the men are more

likely to benefit from agricultural training than women (only one in the sample).

Actors and structures in knowledge development and farming practices

Since the colonial era and until the independence of Madagascar (1896-1960), the colonial

administration put pressure on the farmers to pay the taxes which served to indirectly influence

the decisions taken by new farmers. From the focus-group discussion with the oldest producers,

in that period the local government aimed at improving farmers’ income through the theoretical

(information about crops and how to plant) and technical support offered to the locals (seedling

distribution and training). This pressure was pushing farmers to intensify their cash crop

production (planting in a monocrop systems), incited by the government’s free distribution of the

clove seedlings in the communities.

According to results from the participatory timeline in the 1920s and 1930s the parents of the

current farmers migrated to the Island Saint Marie to harvest the cloves on the colonial

plantations. They brought back the seeds and created their own clove nurseries following the

example from the colonial fields. The 1st generation of planters represents the most important

actors who transmit to the next generation their land, knowledge. They have encouraged to plant

giving to their successors the plants grown underneath their clove trees.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the 2 nd generation of planters (8 of 33 interviewed farmers) achieved

their knowledge initially from the parents. According to these farmers, they have benefited from

agricultural “supervisors” in Ambodihazinina who come from the Ministry of Agriculture and

live in the village to provide technical and practical farmer training. Besides, two other farmers

from Mahavanona worked for the agricultural extension service in Fenerive Est between 1963-

• Mulching of trees with the fallen dry leaves

• Prunning to facilitate the canopy development.

The survey showed that even if 48% of the farmers (16 out of 33) know about the improved

techniques, only 68 % from those who have this knowledge actually applied it on their field due

to the availability of land or time. The labour demand and the time availability for plantation is a

limiting factor for the adaptation of these improved techniques. According to farmers who used

this technique, one man can plant only 20 trees in one day with the improved method compared

to 100 trees with the traditional method. On the other hand, this method has some visible

advantages: clove trees planted grow faster and become productive after 7-8 years compared to

10 years for those planted with the traditional method. From the interviews, farmers received this

type of innovative information after they had already achieved local traditional methods by their

parents or neighbors. Farmers who implemented innovative methods (7 out of 33) are the ones

who are younger (less than 50 years), have still some land available, and have the objective of

improving their livelihoods or have been incited by the national or international development

programs.

In the both villages the share of the type of knowledge differs. More than 70 % of the producers

in the village of Mahavanona, which is closer to the city, have access to the agricultural training

compared to only 29 % of the producers from the remote community. Also, the men are more

likely to benefit from agricultural training than women (only one in the sample).

Actors and structures in knowledge development and farming practices

Since the colonial era and until the independence of Madagascar (1896-1960), the colonial

administration put pressure on the farmers to pay the taxes which served to indirectly influence

the decisions taken by new farmers. From the focus-group discussion with the oldest producers,

in that period the local government aimed at improving farmers’ income through the theoretical

(information about crops and how to plant) and technical support offered to the locals (seedling

distribution and training). This pressure was pushing farmers to intensify their cash crop

production (planting in a monocrop systems), incited by the government’s free distribution of the

clove seedlings in the communities.

According to results from the participatory timeline in the 1920s and 1930s the parents of the

current farmers migrated to the Island Saint Marie to harvest the cloves on the colonial

plantations. They brought back the seeds and created their own clove nurseries following the

example from the colonial fields. The 1st generation of planters represents the most important

actors who transmit to the next generation their land, knowledge. They have encouraged to plant

giving to their successors the plants grown underneath their clove trees.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the 2 nd generation of planters (8 of 33 interviewed farmers) achieved

their knowledge initially from the parents. According to these farmers, they have benefited from

agricultural “supervisors” in Ambodihazinina who come from the Ministry of Agriculture and

live in the village to provide technical and practical farmer training. Besides, two other farmers

from Mahavanona worked for the agricultural extension service in Fenerive Est between 1963-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

1973 to prepare clove seedlings in the nursery and as technical agent. These qualified workers

were responsible for sharing the theoretical knowledge through community workshops and

offered technical support showing examples on their own fields. This contributed to a higher

degree of confidence in new farmers to effectively implement this type of clove farming system.

The transfer process from “farmer to farmer” has a bigger impact on the clove plantation,

particularly because of the confidence in their peers.

Between 1960s and 1990s many events had an impact on the clove production. Political

instability together with the periodic declines of outputs, ascribed in part for the instability of

prices and production, steered local farmers to find other ways to complement their revenues.

The 3 rd generation of producers, installed in this period lacked a presence or dissemination of

specialised information. Their knowledge comes from the parents, but less incitation from the

state to plant clove tree farms.

Lately (starting from 1990) in the study area it is observed a resurgence of the formal specialised

knowledge and practices coming from different public and private (NGOs and cooperatives). In

this period, new installed farmers (48%) start achieving improved techniques, either through

agricultural training or interacting with different stakeholders.

Another more innovative way of transmitting the knowledge is the mass-media channel where

farmers receive information via radio (about the weather conditions and crop management),

printed leaflets (for clove tree management practices) or agricultural journals. Nevertheless, the

access that farmers have to this information is limited by the remote location of some producers

and access to electricity. Due to lack of electricity network and time to listen to radio programs

in the remote areas the producers have a lower impact on the information access. Even if they

have access to radio, the information can be limited in dispersion by the availability of time, as a

producer says: “the farmers are working on the field and cannot always hear the radio

programmes”. Another limiting factor can be the distribution of journals or leaflets to the farmers

who have no schooling (9%).

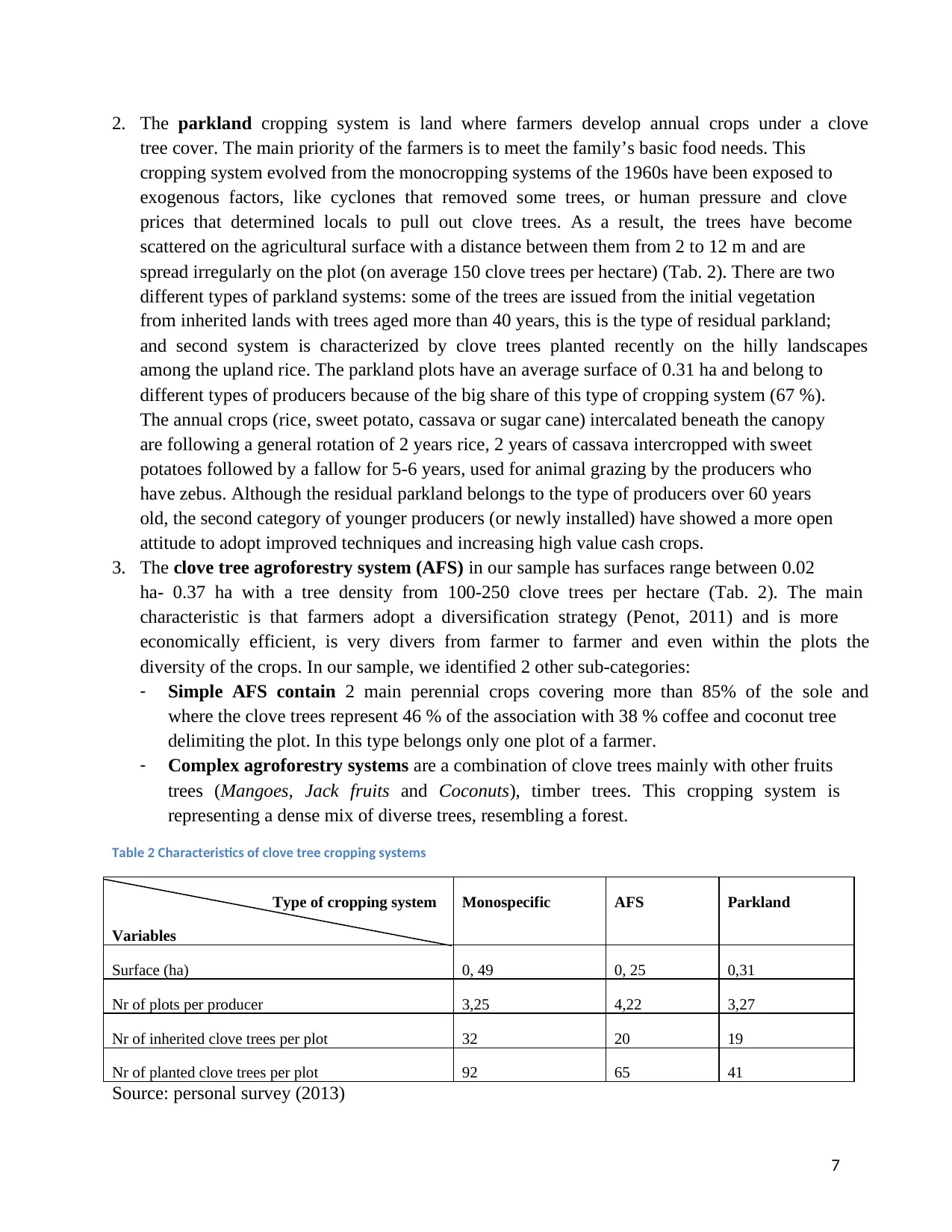

Time dimension in the knowledge system

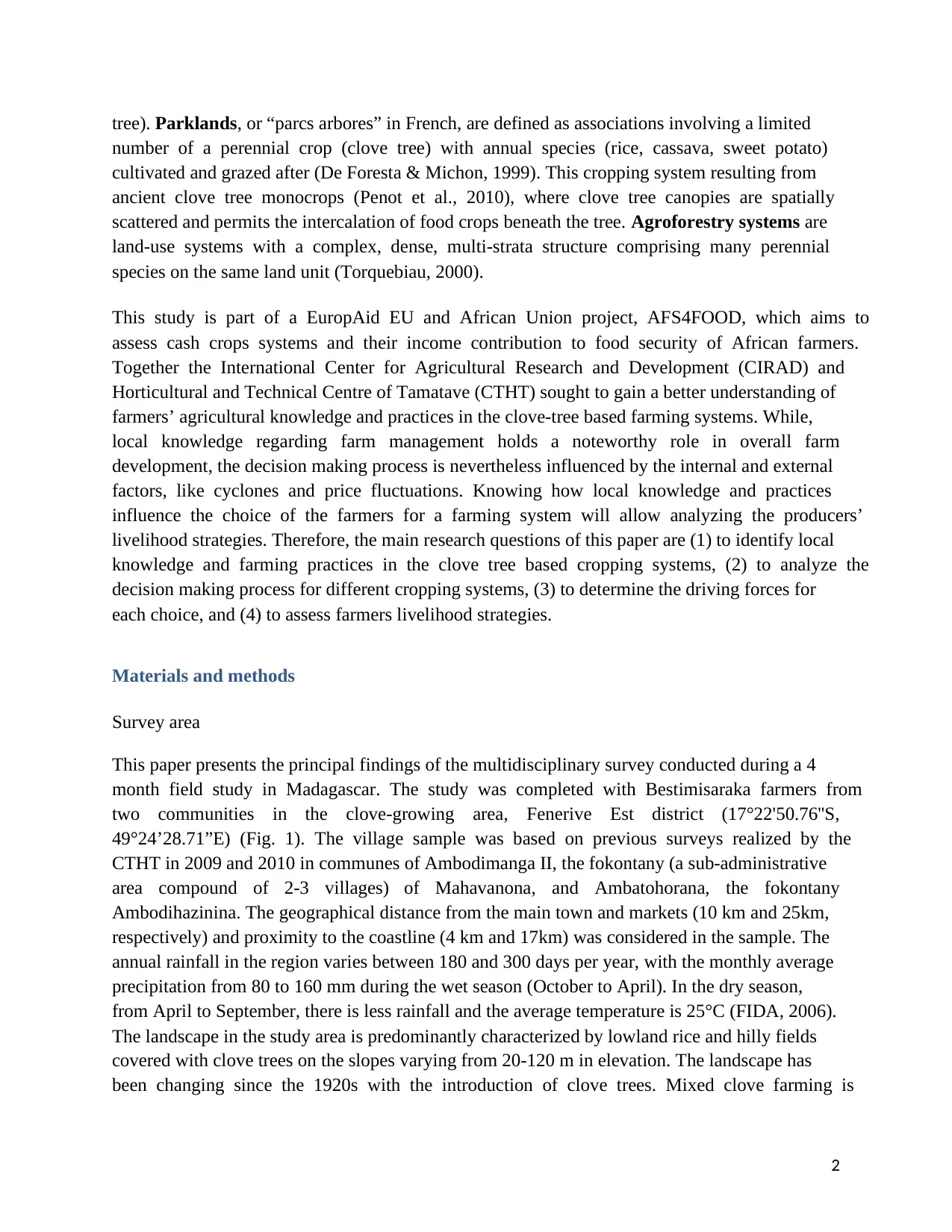

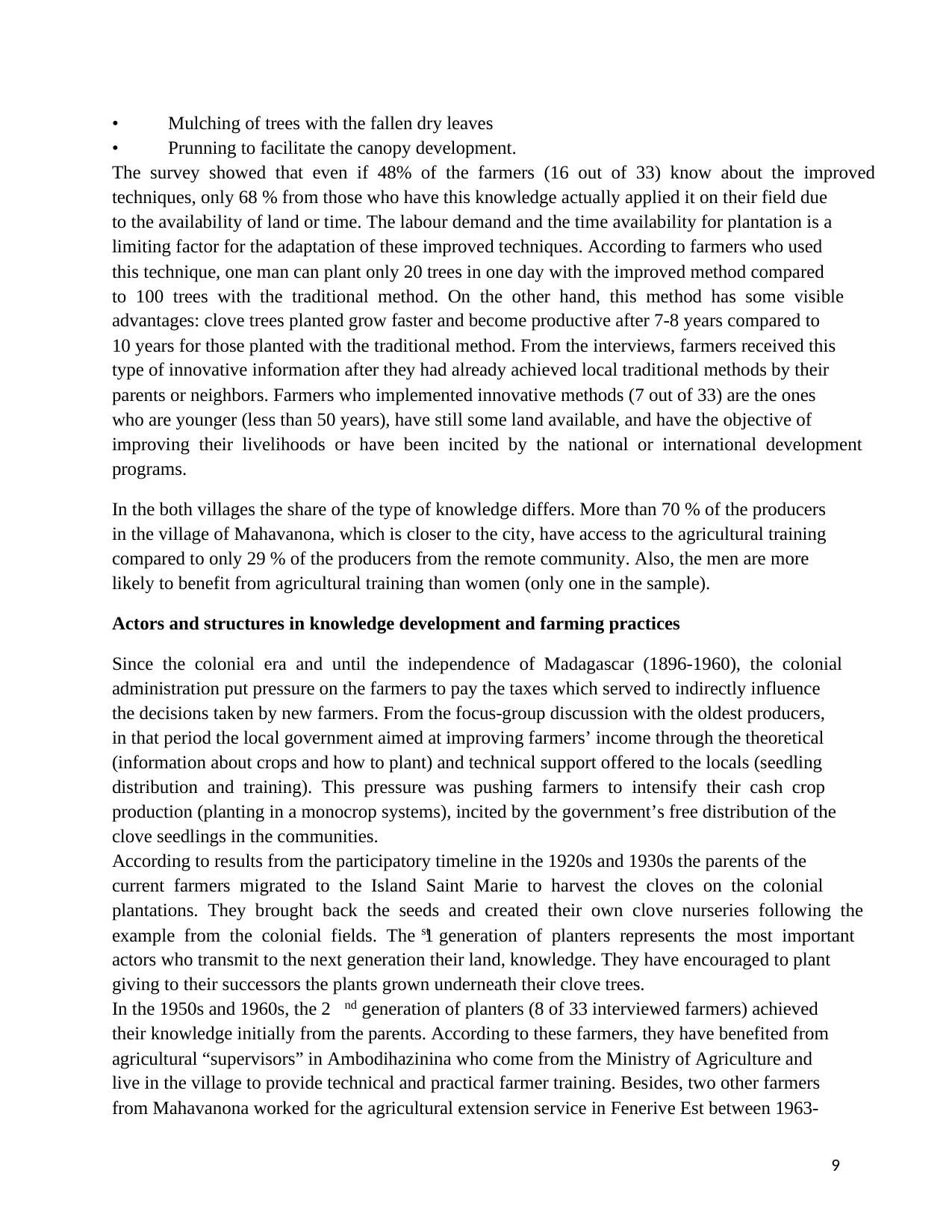

As observed in the following

figure the interaction of different

development stakeholders with the

local producers had an impact on

the rate of clove tree plantation in

the study area, corresponding to

the periods of stronger agricultural

support (Fig. 2).

Analyzing the evolution of the

clove tree plantations (Fig. 2), the

drop of number of tree planted is

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

1960-1970

1970-1980

1980-1990

1990-2000

2000-2011

The dynamic of clove tree plantation in 1960-2011

MAHAVANONA

AMBODIHAZININA

Figure 2 The evolution of clove tree plantations in the studied villages

1973 to prepare clove seedlings in the nursery and as technical agent. These qualified workers

were responsible for sharing the theoretical knowledge through community workshops and

offered technical support showing examples on their own fields. This contributed to a higher

degree of confidence in new farmers to effectively implement this type of clove farming system.

The transfer process from “farmer to farmer” has a bigger impact on the clove plantation,

particularly because of the confidence in their peers.

Between 1960s and 1990s many events had an impact on the clove production. Political

instability together with the periodic declines of outputs, ascribed in part for the instability of

prices and production, steered local farmers to find other ways to complement their revenues.

The 3 rd generation of producers, installed in this period lacked a presence or dissemination of

specialised information. Their knowledge comes from the parents, but less incitation from the

state to plant clove tree farms.

Lately (starting from 1990) in the study area it is observed a resurgence of the formal specialised

knowledge and practices coming from different public and private (NGOs and cooperatives). In

this period, new installed farmers (48%) start achieving improved techniques, either through

agricultural training or interacting with different stakeholders.

Another more innovative way of transmitting the knowledge is the mass-media channel where

farmers receive information via radio (about the weather conditions and crop management),

printed leaflets (for clove tree management practices) or agricultural journals. Nevertheless, the

access that farmers have to this information is limited by the remote location of some producers

and access to electricity. Due to lack of electricity network and time to listen to radio programs

in the remote areas the producers have a lower impact on the information access. Even if they

have access to radio, the information can be limited in dispersion by the availability of time, as a

producer says: “the farmers are working on the field and cannot always hear the radio

programmes”. Another limiting factor can be the distribution of journals or leaflets to the farmers

who have no schooling (9%).

Time dimension in the knowledge system

As observed in the following

figure the interaction of different

development stakeholders with the

local producers had an impact on

the rate of clove tree plantation in

the study area, corresponding to

the periods of stronger agricultural

support (Fig. 2).

Analyzing the evolution of the

clove tree plantations (Fig. 2), the

drop of number of tree planted is

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

1960-1970

1970-1980

1980-1990

1990-2000

2000-2011

The dynamic of clove tree plantation in 1960-2011

MAHAVANONA

AMBODIHAZININA

Figure 2 The evolution of clove tree plantations in the studied villages

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

associated with the application of the recommended techniques together with the distribution of

free seedlings. Nonetheless, the village close to the market and city has more access to vegetal

material compared to the remote areas due to the road infrastructure.

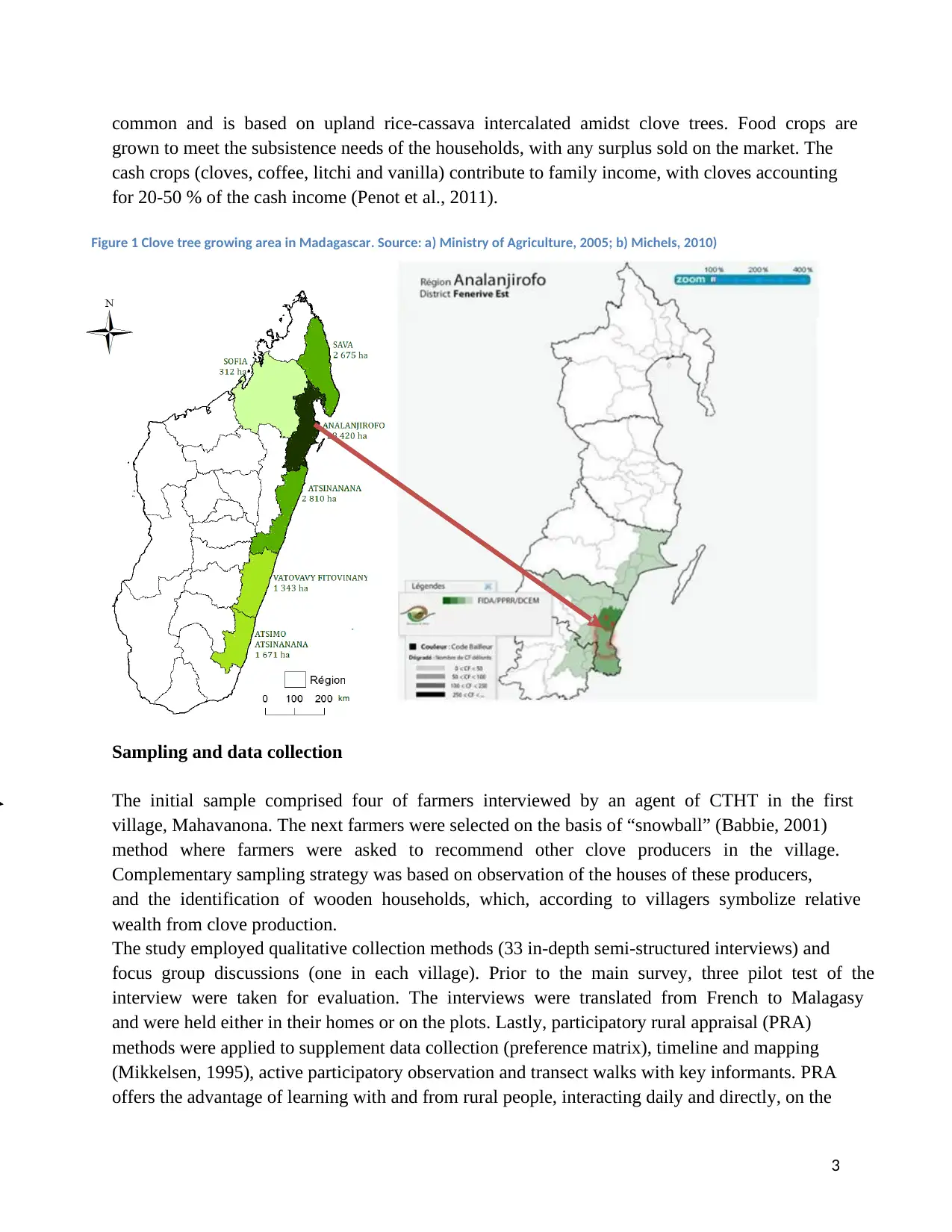

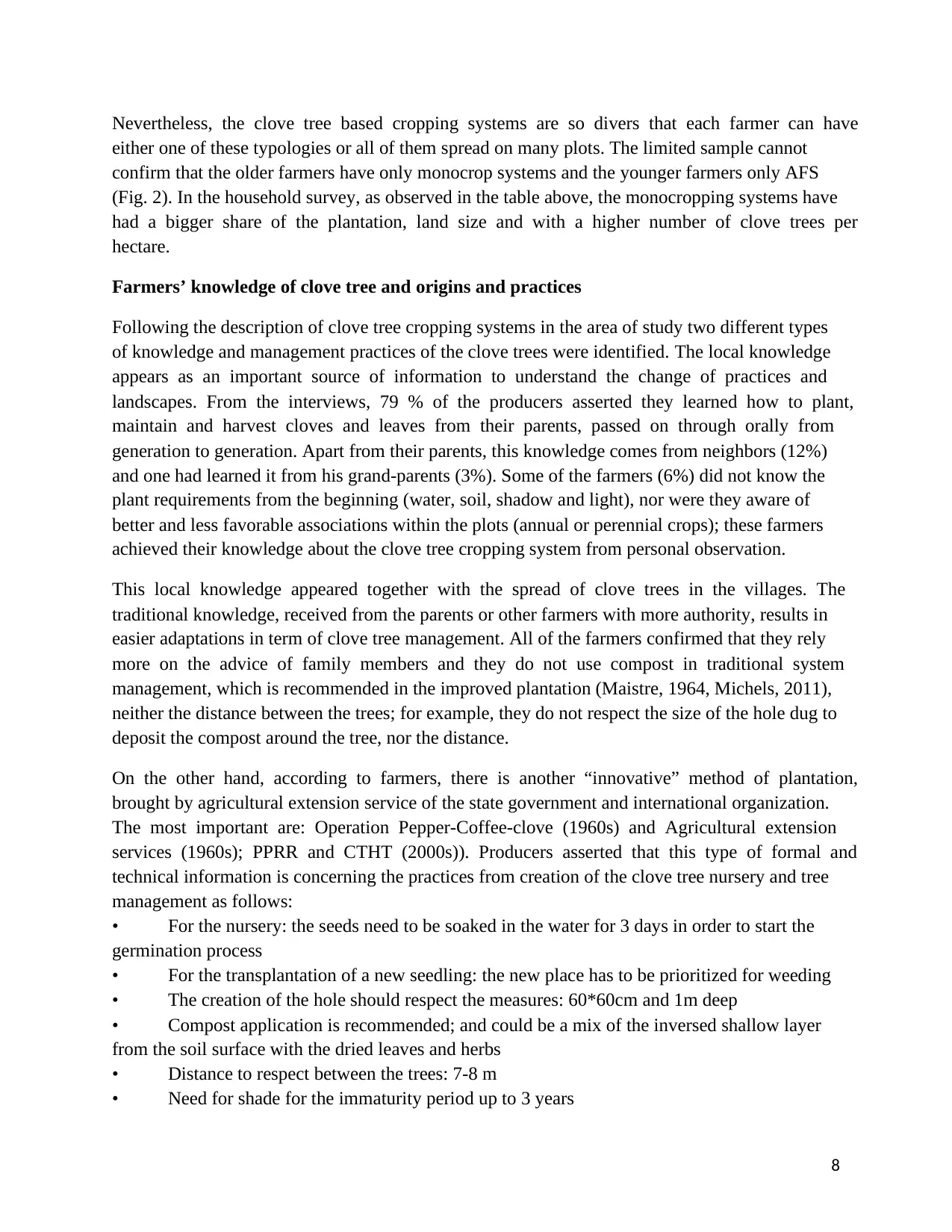

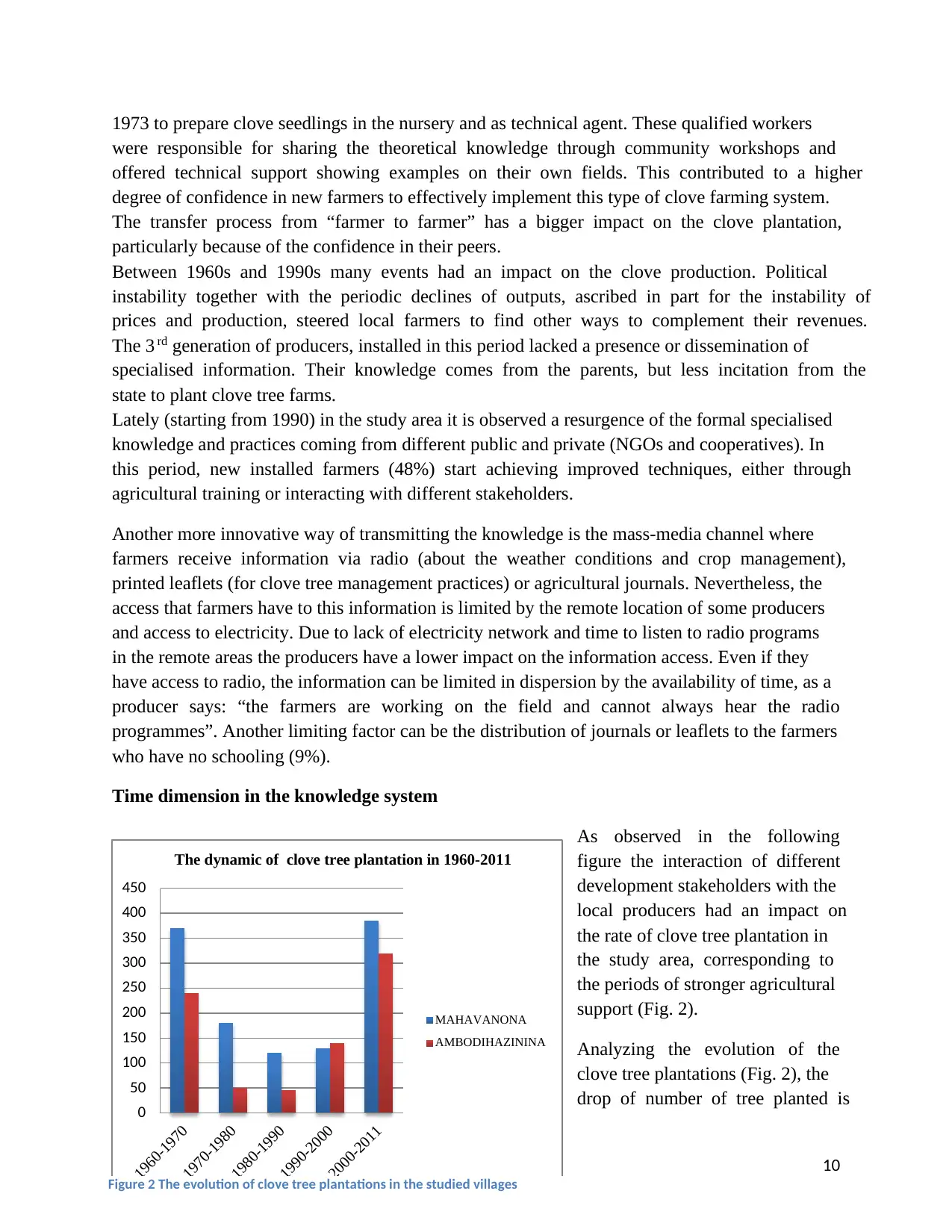

Also, with time farmers with more experience (more than 50 years) who achieved local and

formal knowledge have a higher numbers of clove trees (Fig. 3). From the interviews, most of

the clove trees belong to the producers aged around 50 years, who achieved the land from the

parents with the inherited trees. They can vary from 10-200 trees per plot and per farmer.

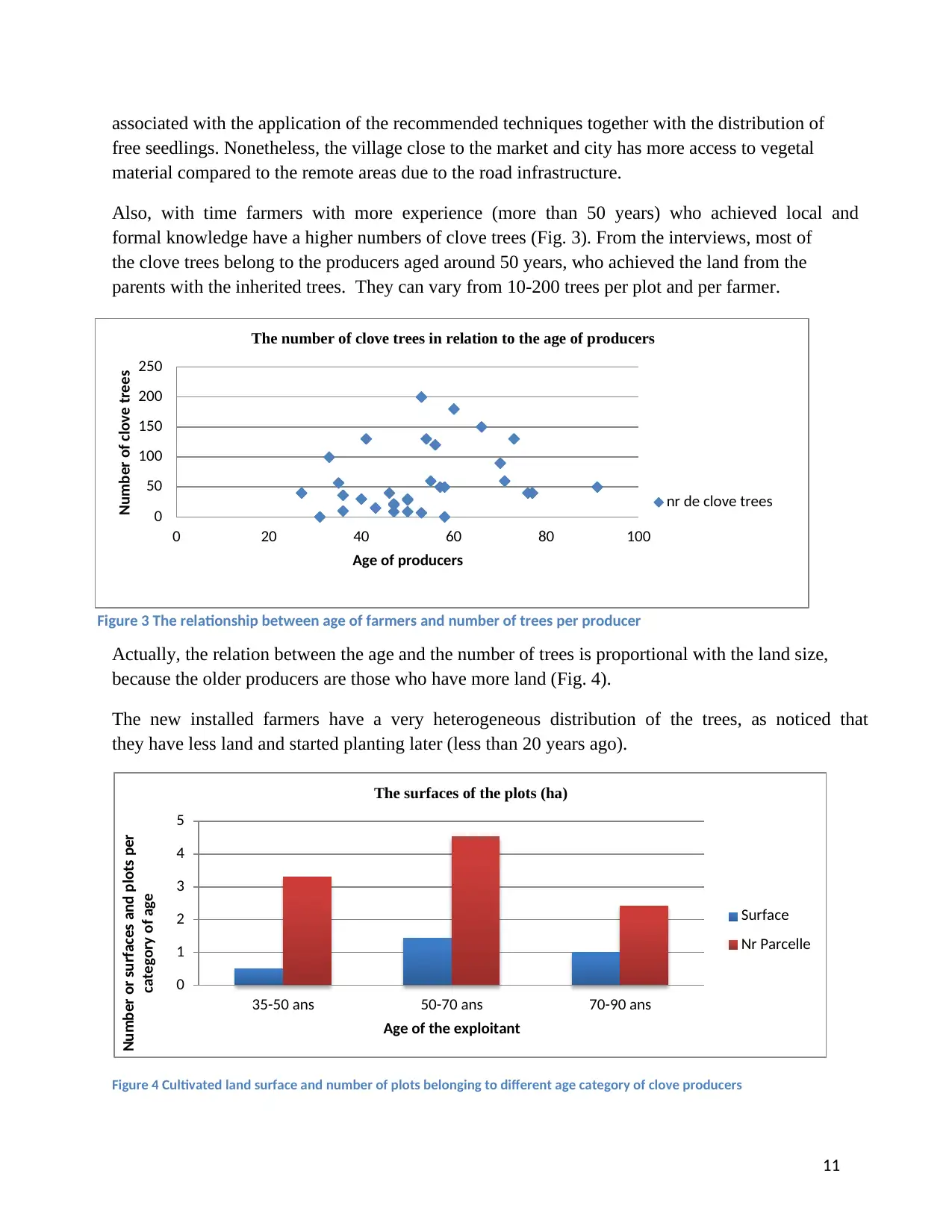

Actually, the relation between the age and the number of trees is proportional with the land size,

because the older producers are those who have more land (Fig. 4).

The new installed farmers have a very heterogeneous distribution of the trees, as noticed that

they have less land and started planting later (less than 20 years ago).

Figure 4 Cultivated land surface and number of plots belonging to different age category of clove producers

0

1

2

3

4

5

35-50 ans 50-70 ans 70-90 ans

Number or surfaces and plots per

category of age

Age of the exploitant

The surfaces of the plots (ha)

Surface

Nr Parcelle

0

50

100

150

200

250

0 20 40 60 80 100

Number of clove trees

Age of producers

The number of clove trees in relation to the age of producers

nr de clove trees

Figure 3 The relationship between age of farmers and number of trees per producer

associated with the application of the recommended techniques together with the distribution of

free seedlings. Nonetheless, the village close to the market and city has more access to vegetal

material compared to the remote areas due to the road infrastructure.

Also, with time farmers with more experience (more than 50 years) who achieved local and

formal knowledge have a higher numbers of clove trees (Fig. 3). From the interviews, most of

the clove trees belong to the producers aged around 50 years, who achieved the land from the

parents with the inherited trees. They can vary from 10-200 trees per plot and per farmer.

Actually, the relation between the age and the number of trees is proportional with the land size,

because the older producers are those who have more land (Fig. 4).

The new installed farmers have a very heterogeneous distribution of the trees, as noticed that

they have less land and started planting later (less than 20 years ago).

Figure 4 Cultivated land surface and number of plots belonging to different age category of clove producers

0

1

2

3

4

5

35-50 ans 50-70 ans 70-90 ans

Number or surfaces and plots per

category of age

Age of the exploitant

The surfaces of the plots (ha)

Surface

Nr Parcelle

0

50

100

150

200

250

0 20 40 60 80 100

Number of clove trees

Age of producers

The number of clove trees in relation to the age of producers

nr de clove trees

Figure 3 The relationship between age of farmers and number of trees per producer

12

Nevertheless, the age of the producers is not always a key indicator for the knowledge. The

interaction with agricultural extension service is determinant for the type of knowledge. But the

land ownership and surface have the most important role in the choice of the cropping systems.

Historical evolution of tree diversity in clove systems

From the free walks on the fields it was observed in some AFS the association of clove and

coffee trees in sequential arrangements within the plots, issued from the same period as

monocropping systems (colonial period). Coffee (C. Canephora) was introduced in the region

before clove trees (1900s) (Ramilison, 1985) as participants of the timeline exercise confirmed.

Monocropped plantations of coffee were damaged by a fungus attack in the early 1930s by

« Hemileia vastarix » (Ramilison, 1985). Old coffee trees were replaced with clove trees.

Though, in the households’ surveys the AFS (18% of our sample) appear to be more recent

cropping system from the period that farmers started to diversify after 1980s.

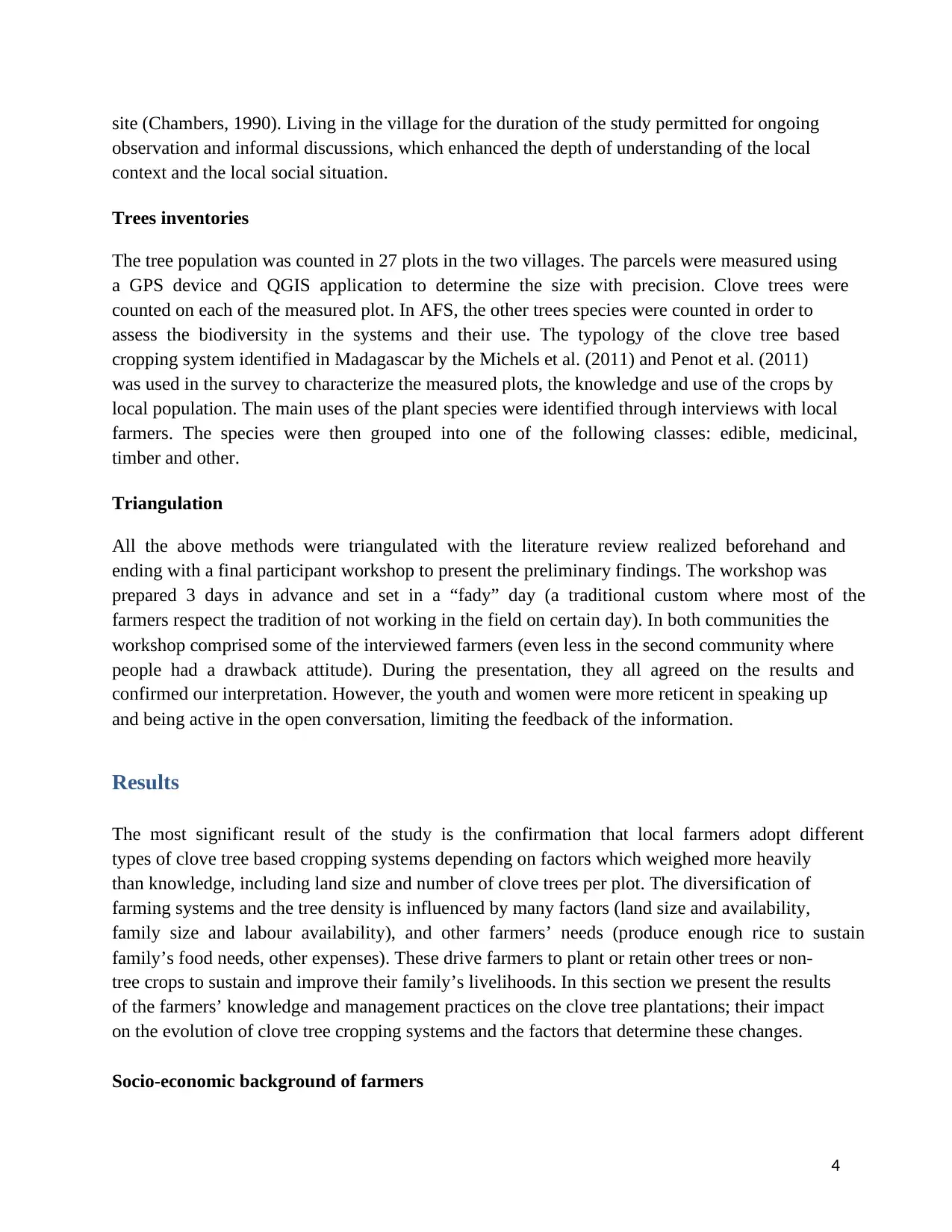

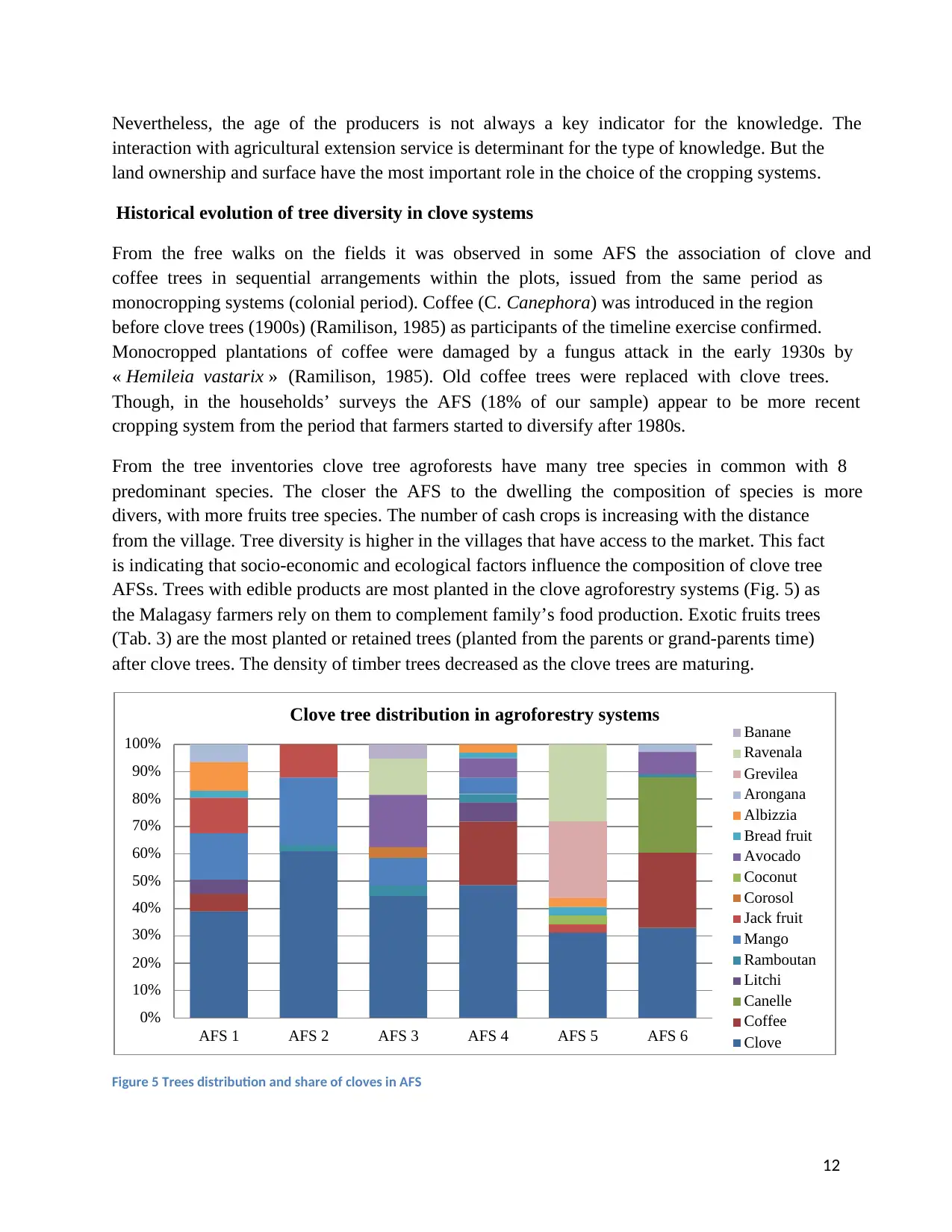

From the tree inventories clove tree agroforests have many tree species in common with 8

predominant species. The closer the AFS to the dwelling the composition of species is more

divers, with more fruits tree species. The number of cash crops is increasing with the distance

from the village. Tree diversity is higher in the villages that have access to the market. This fact

is indicating that socio-economic and ecological factors influence the composition of clove tree

AFSs. Trees with edible products are most planted in the clove agroforestry systems (Fig. 5) as

the Malagasy farmers rely on them to complement family’s food production. Exotic fruits trees

(Tab. 3) are the most planted or retained trees (planted from the parents or grand-parents time)

after clove trees. The density of timber trees decreased as the clove trees are maturing.

Figure 5 Trees distribution and share of cloves in AFS

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

AFS 1 AFS 2 AFS 3 AFS 4 AFS 5 AFS 6

Clove tree distribution in agroforestry systems Banane

Ravenala

Grevilea

Arongana

Albizzia

Bread fruit

Avocado

Coconut

Corosol

Jack fruit

Mango

Ramboutan

Litchi

Canelle

Coffee

Clove

Nevertheless, the age of the producers is not always a key indicator for the knowledge. The

interaction with agricultural extension service is determinant for the type of knowledge. But the

land ownership and surface have the most important role in the choice of the cropping systems.

Historical evolution of tree diversity in clove systems

From the free walks on the fields it was observed in some AFS the association of clove and

coffee trees in sequential arrangements within the plots, issued from the same period as

monocropping systems (colonial period). Coffee (C. Canephora) was introduced in the region

before clove trees (1900s) (Ramilison, 1985) as participants of the timeline exercise confirmed.

Monocropped plantations of coffee were damaged by a fungus attack in the early 1930s by

« Hemileia vastarix » (Ramilison, 1985). Old coffee trees were replaced with clove trees.

Though, in the households’ surveys the AFS (18% of our sample) appear to be more recent

cropping system from the period that farmers started to diversify after 1980s.

From the tree inventories clove tree agroforests have many tree species in common with 8

predominant species. The closer the AFS to the dwelling the composition of species is more

divers, with more fruits tree species. The number of cash crops is increasing with the distance

from the village. Tree diversity is higher in the villages that have access to the market. This fact

is indicating that socio-economic and ecological factors influence the composition of clove tree

AFSs. Trees with edible products are most planted in the clove agroforestry systems (Fig. 5) as

the Malagasy farmers rely on them to complement family’s food production. Exotic fruits trees

(Tab. 3) are the most planted or retained trees (planted from the parents or grand-parents time)

after clove trees. The density of timber trees decreased as the clove trees are maturing.

Figure 5 Trees distribution and share of cloves in AFS

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

AFS 1 AFS 2 AFS 3 AFS 4 AFS 5 AFS 6

Clove tree distribution in agroforestry systems Banane

Ravenala

Grevilea

Arongana

Albizzia

Bread fruit

Avocado

Coconut

Corosol

Jack fruit

Mango

Ramboutan

Litchi

Canelle

Coffee

Clove

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 21

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.