Comprehensive Report: Managing Across Cultures - Lessons 1-10

VerifiedAdded on 2022/05/05

|16

|6602

|22

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of managing across cultures, exploring the dynamic global context and its impact on business operations. It defines globalization, highlighting its pros and cons, and examines the risks and opportunities associated with emerging markets. The report delves into the concept of stakeholders and the influence of culture on leadership and management, differentiating between transformational and transactional leadership styles. It discusses individualistic versus collectivist cultures, national culture's impact on organizational behavior, and provides definitions of culture. Additionally, the report covers cultural theories, including those of Hofstede and Trompenaars, and analyzes cultural distance and corporate approaches to international business, such as global and multi-domestic companies. It concludes by examining ethnocentric and polycentric views in management, offering a holistic understanding of the complexities of managing across diverse cultural landscapes.

MANAGING ACROSS CULTURES

LESSON 1 – 10

Changing global context

o The business environment in which an organisation operates is characterised by constant

change.

This presents opportunities, threats and challenges. Pre-empting change and then exploiting

suitable opportunities, often global opportunities, is the way firms gain competitive

advantage. However, operating in this changing global context also poses threats and

presents challenges. In particular, it calls for skills in managing people across different

cultures and working with customers, suppliers and strategic partners from diverse cultural

backgrounds.

Deresky (2016) explains how developments and trends within a dramatically changing global

stage present management with a range of challenges including the design and

implementation of global strategies, conducting effective cross-national interactions, and

managing operations in foreign subsidiaries. Deresky (2016) makes the important

observation that “Global companies are faced with varied and dynamic environments in

which they must accurately assess the political, legal, technological, competitive and cultural

factors that shape their strategies and operations. The fate of overseas operations depends

greatly on the international manager’s cultural skills and sensitivity, as well as the ability to

carry out the company’s strategy within the context of the host country’s business

practices.”

WHAT IS GLOBALISATION?

Globalization is the spread of products, technology, information, and jobs across national

borders and cultures. In economic terms, it describes an interdependence of nations

around the globe fostered through free trade.

On the upside, it can raise the standard of living in poor and less developed countries by

providing job opportunity, modernization, and improved access to goods and services. On

the downside, it can destroy job opportunities in more developed and high-wage countries

as the production of goods moves across borders.

Globalization motives are idealistic, as well as opportunistic, but the development of a

global free market has benefited large corporations based in the Western world. Its impact

remains mixed for workers, cultures, and small businesses around the globe, in both

developed and emerging nations.

Find pros and cons

LESSON 1 – 10

Changing global context

o The business environment in which an organisation operates is characterised by constant

change.

This presents opportunities, threats and challenges. Pre-empting change and then exploiting

suitable opportunities, often global opportunities, is the way firms gain competitive

advantage. However, operating in this changing global context also poses threats and

presents challenges. In particular, it calls for skills in managing people across different

cultures and working with customers, suppliers and strategic partners from diverse cultural

backgrounds.

Deresky (2016) explains how developments and trends within a dramatically changing global

stage present management with a range of challenges including the design and

implementation of global strategies, conducting effective cross-national interactions, and

managing operations in foreign subsidiaries. Deresky (2016) makes the important

observation that “Global companies are faced with varied and dynamic environments in

which they must accurately assess the political, legal, technological, competitive and cultural

factors that shape their strategies and operations. The fate of overseas operations depends

greatly on the international manager’s cultural skills and sensitivity, as well as the ability to

carry out the company’s strategy within the context of the host country’s business

practices.”

WHAT IS GLOBALISATION?

Globalization is the spread of products, technology, information, and jobs across national

borders and cultures. In economic terms, it describes an interdependence of nations

around the globe fostered through free trade.

On the upside, it can raise the standard of living in poor and less developed countries by

providing job opportunity, modernization, and improved access to goods and services. On

the downside, it can destroy job opportunities in more developed and high-wage countries

as the production of goods moves across borders.

Globalization motives are idealistic, as well as opportunistic, but the development of a

global free market has benefited large corporations based in the Western world. Its impact

remains mixed for workers, cultures, and small businesses around the globe, in both

developed and emerging nations.

Find pros and cons

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Emerging markets: Risks and opportunities

Opportunities: Access to cheaper labour markets, Access to raw materials, Access to

expanding consumer markets (e.g. China and India in particular), Increased demand for

luxury goods (huge demand in Asia), Tapping into new sources of talent, developing strategic

alliances with local companies, Undertaking joint ventures with innovative emerging MNCs.

Risks: Close relationship between government and business in a number of emerging

markets - challenges the principle of non-state interference in free-market capitalism,

Financial risks. For instance, the potential impact of national inflation levels, currency

stability, sector trends, levels of taxation, and the reporting required by governments, The

potential lack of infrastructure including essential commodities (e.g. water and power

supplies), The potential for war, terrorism or political instability (including piracy and

kidnapping), Censorship and restrictions on information, Getting the marketing wrong,

Cross-cultural management issues. Strategic alliances between Western companies and

firms in emerging markets have tended to be short-lived. Joint ventures in China have often

exposed mutual frustrations between Western and Chinese managers about management

practices, such as HRM.

WHAT IS A STAKEHOLDER?

A stakeholder is a party that has an interest in a company and can either affect or be

affected by the business. The primary stakeholders in a typical corporation are its investors,

employees, customers and suppliers. However, the modern theory of the idea goes beyond

this original notion to include additional stakeholders such as a community, government or

trade association.

Influence of culture on leadership and management

Leadership in an organisation is exhibited at all levels - from leadership of small teams to

leadership as a CEO. At the executive levels, in an increasingly global environment, the

emphasis is on global leadership. And at this level the boundaries between leadership and

management become blurred.

Leadership styles can vary from country to country. A transformational leadership style is

particularly popular in the West and linked with successful companies such as Apple. A

transformational leader is someone who: Creates a vision that inspires and motivates

followers to higher levels of performance and commitment to the organisation.

Demonstrates concern for their followers. Acts as a role model. Challenges the prevailing

culture.

This is in contrast to a transactional leadership style. A transactional leader is someone who

relies on explicit rewards or penalties to motivate people. This is a leadership style often

adopted by countries in East Asia.

Opportunities: Access to cheaper labour markets, Access to raw materials, Access to

expanding consumer markets (e.g. China and India in particular), Increased demand for

luxury goods (huge demand in Asia), Tapping into new sources of talent, developing strategic

alliances with local companies, Undertaking joint ventures with innovative emerging MNCs.

Risks: Close relationship between government and business in a number of emerging

markets - challenges the principle of non-state interference in free-market capitalism,

Financial risks. For instance, the potential impact of national inflation levels, currency

stability, sector trends, levels of taxation, and the reporting required by governments, The

potential lack of infrastructure including essential commodities (e.g. water and power

supplies), The potential for war, terrorism or political instability (including piracy and

kidnapping), Censorship and restrictions on information, Getting the marketing wrong,

Cross-cultural management issues. Strategic alliances between Western companies and

firms in emerging markets have tended to be short-lived. Joint ventures in China have often

exposed mutual frustrations between Western and Chinese managers about management

practices, such as HRM.

WHAT IS A STAKEHOLDER?

A stakeholder is a party that has an interest in a company and can either affect or be

affected by the business. The primary stakeholders in a typical corporation are its investors,

employees, customers and suppliers. However, the modern theory of the idea goes beyond

this original notion to include additional stakeholders such as a community, government or

trade association.

Influence of culture on leadership and management

Leadership in an organisation is exhibited at all levels - from leadership of small teams to

leadership as a CEO. At the executive levels, in an increasingly global environment, the

emphasis is on global leadership. And at this level the boundaries between leadership and

management become blurred.

Leadership styles can vary from country to country. A transformational leadership style is

particularly popular in the West and linked with successful companies such as Apple. A

transformational leader is someone who: Creates a vision that inspires and motivates

followers to higher levels of performance and commitment to the organisation.

Demonstrates concern for their followers. Acts as a role model. Challenges the prevailing

culture.

This is in contrast to a transactional leadership style. A transactional leader is someone who

relies on explicit rewards or penalties to motivate people. This is a leadership style often

adopted by countries in East Asia.

Individualistic vs. collectivist cultures

Many of the newly emerging markets are collectivist societies. Here, family ties are

stronger than in Western societies, which place more emphasis on the individual. Loyalty

to work colleagues is an important characteristic of collectivist societies. For instance,

individuals will not blame each other for mistakes. This is in contrast to most Western

societies which tend to be individualistic, where the prioritisation is on the individual over

groups. In the individualistic culture the focus is more on self-achievement whereas in the

collectivist culture the focus is very much on group achievement.

National culture and organisational behaviour

We have already noted one area of difference in organisational behaviour stemming from

culture. In collectivist cultures, employee ties are very strong, and the apportioning of blame

is rare. There are many other behaviours influenced by national culture. In some countries,

in conflict or contentious situations, straight talking (or even blunt talking) is the norm,

whereas in other countries diplomatic talking is the acceptable form. In some countries,

team working is natural, and a consensus-based approach is expected, whereas in other

countries employees like to be told what they should do. Then there are differences in

meeting styles. In some countries, lengthy meetings are to be expected as everyone must

have a say, whereas in other countries strict adherence to the schedule is expected.

Attitudes to the role of women in the workplace are also highly influenced by national

culture, and so are attitudes towards diversity.

Definitions of culture

Culture is something we understand intuitively but often find difficult to define. It is often

explained as ‘how things are done around here’. It is something intangible, and in the

context of national culture, it sets a country apart from others. Each country has its own

unique culture. In the same way, each organisation has its own unique culture, and one of

the factors influencing organisational culture is national culture. Typically, in a multinational

or global corporation, the home country of the corporation has a strong influence on its

culture. But as we have examined in cross-cultural leadership and management, subsidiaries

operating overseas are also influenced by the local context and culture - indeed they should

be for effectiveness. This is often referred to as ‘glocalization’.

Diverse cultures, conflicts and impact on business

International managers must understand the distinguishing characteristics of cultures and

how national culture impacts business behaviour.

A culture is the product of many distinguishing features, such as:

Language; not always one. For example, in Canada, English and French are both spoken and

bi-lingualise is common.

Religion: again, as in language, not always one. For example, in Sri Lanka the main religion is

Buddhism. However, regions within the country are dominated by Hinduism, and there is

also a small Christian and Muslim presence.

Many of the newly emerging markets are collectivist societies. Here, family ties are

stronger than in Western societies, which place more emphasis on the individual. Loyalty

to work colleagues is an important characteristic of collectivist societies. For instance,

individuals will not blame each other for mistakes. This is in contrast to most Western

societies which tend to be individualistic, where the prioritisation is on the individual over

groups. In the individualistic culture the focus is more on self-achievement whereas in the

collectivist culture the focus is very much on group achievement.

National culture and organisational behaviour

We have already noted one area of difference in organisational behaviour stemming from

culture. In collectivist cultures, employee ties are very strong, and the apportioning of blame

is rare. There are many other behaviours influenced by national culture. In some countries,

in conflict or contentious situations, straight talking (or even blunt talking) is the norm,

whereas in other countries diplomatic talking is the acceptable form. In some countries,

team working is natural, and a consensus-based approach is expected, whereas in other

countries employees like to be told what they should do. Then there are differences in

meeting styles. In some countries, lengthy meetings are to be expected as everyone must

have a say, whereas in other countries strict adherence to the schedule is expected.

Attitudes to the role of women in the workplace are also highly influenced by national

culture, and so are attitudes towards diversity.

Definitions of culture

Culture is something we understand intuitively but often find difficult to define. It is often

explained as ‘how things are done around here’. It is something intangible, and in the

context of national culture, it sets a country apart from others. Each country has its own

unique culture. In the same way, each organisation has its own unique culture, and one of

the factors influencing organisational culture is national culture. Typically, in a multinational

or global corporation, the home country of the corporation has a strong influence on its

culture. But as we have examined in cross-cultural leadership and management, subsidiaries

operating overseas are also influenced by the local context and culture - indeed they should

be for effectiveness. This is often referred to as ‘glocalization’.

Diverse cultures, conflicts and impact on business

International managers must understand the distinguishing characteristics of cultures and

how national culture impacts business behaviour.

A culture is the product of many distinguishing features, such as:

Language; not always one. For example, in Canada, English and French are both spoken and

bi-lingualise is common.

Religion: again, as in language, not always one. For example, in Sri Lanka the main religion is

Buddhism. However, regions within the country are dominated by Hinduism, and there is

also a small Christian and Muslim presence.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Ethnic and racial identity: again, as in the previous characteristics, there is often more than

one ethnic/racial grouping. For example, in Singapore, there are Malay, Chinese, Tamil and

European racial groupings. Within these, there are further sub-groupings of ethnicity.

Shared cultural history.

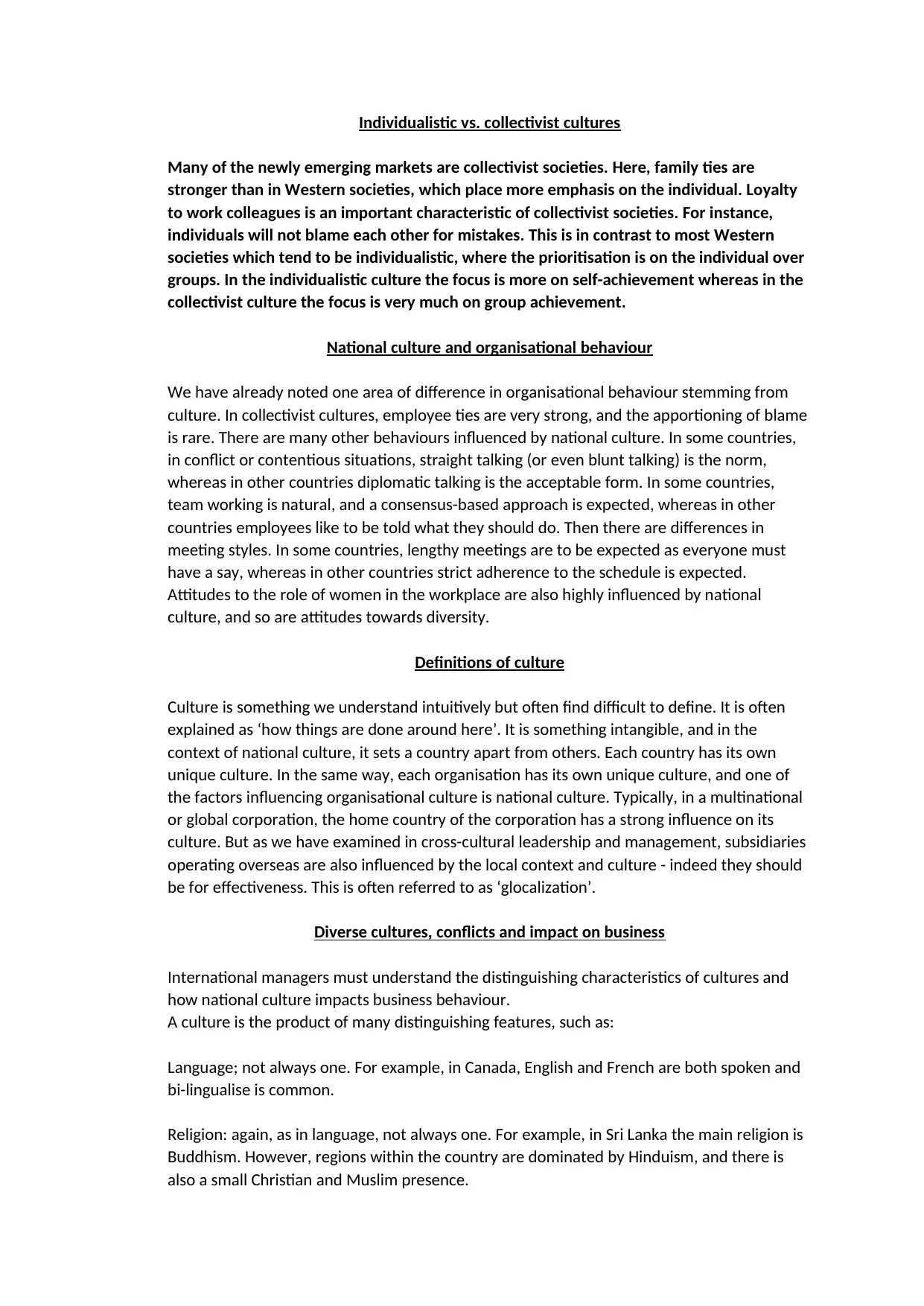

Cultural theories

International managers can underestimate the significance of cultural differences. Gaining a working

knowledge of the cultural variations that impact business and decision-making must be the top

priority of any international manager. Cultural theories can give insights into workplace variations.

We shall examine two theories that contribute to the systematic understanding of the differences.

Hofstede 1980’s:

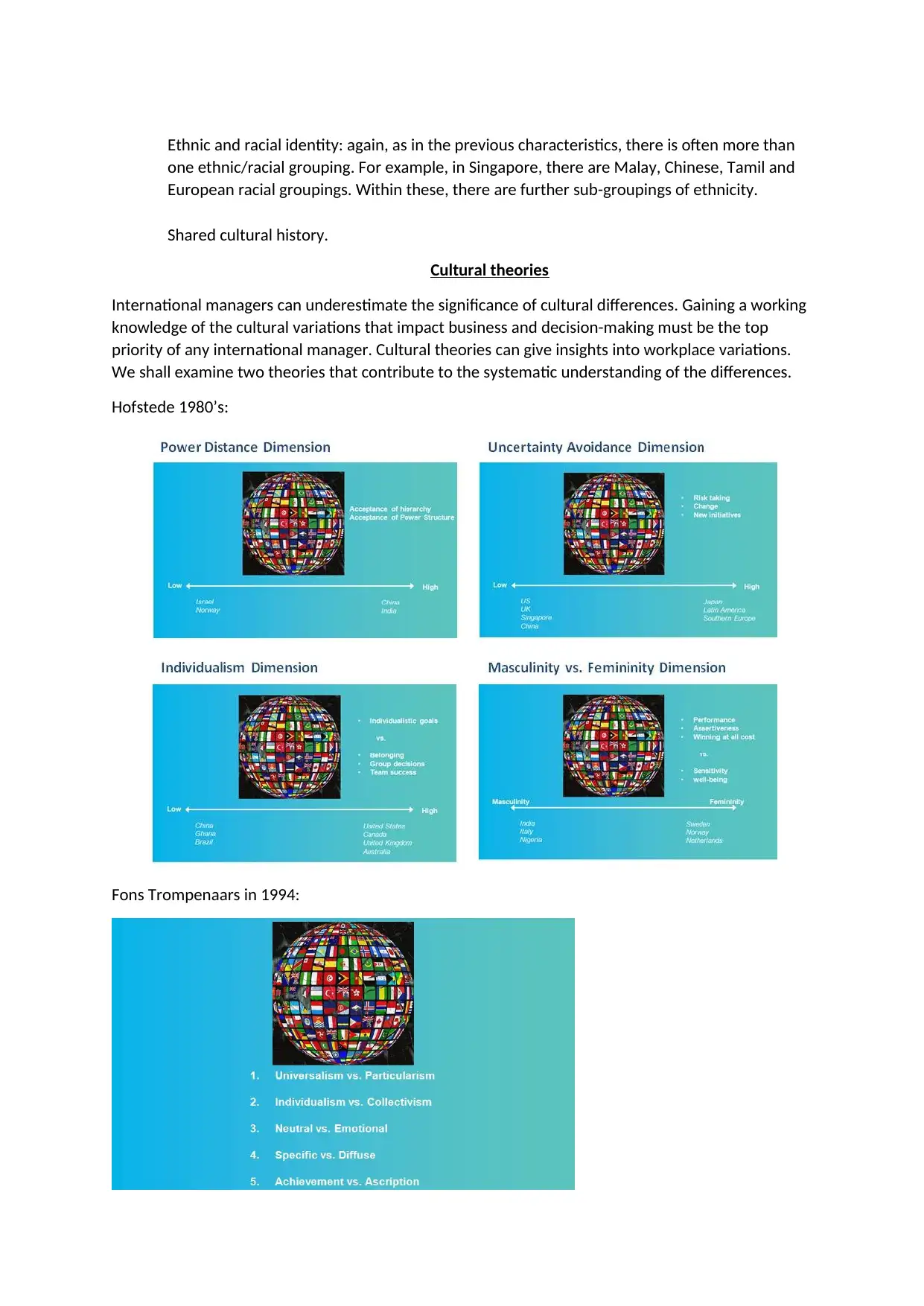

Fons Trompenaars in 1994:

one ethnic/racial grouping. For example, in Singapore, there are Malay, Chinese, Tamil and

European racial groupings. Within these, there are further sub-groupings of ethnicity.

Shared cultural history.

Cultural theories

International managers can underestimate the significance of cultural differences. Gaining a working

knowledge of the cultural variations that impact business and decision-making must be the top

priority of any international manager. Cultural theories can give insights into workplace variations.

We shall examine two theories that contribute to the systematic understanding of the differences.

Hofstede 1980’s:

Fons Trompenaars in 1994:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Ethnocentric, polycentric and geocentric views in management

Cultural distance

We have looked at diverse workplace behaviour, such as individualism vs. collectivism or uncertainty

avoidance, resulting from cultural differences. Now diversity in workplace culture doesn't affect all

companies - simply because they do not actually have offices in overseas locations. However, most

companies today want to engage in international business even if they do not have offices in

overseas locations - they especially want to market their products as widely across the globe as

possible. To this end, consideration of cultural distance is important. Cultural distance is the extent

of the challenge a company faces when selling in overseas markets.

Corporate approaches to international business

At the heart of corporate approaches to international business is understanding on how value is

created through cross-border activities. This requires skills in analysing and critically evaluating the

company's strategy and its competitive environment. Sometimes international business does call for

operating in multiple overseas locations. The organisational issues and the complexity of managing

geographically distributed locations should not be underestimated. The best internationalisation

strategies can fail because the organisation hasn't understood how to internationalise, particularly

from a cultural perspective. An understanding of various organisational forms available to

multinational corporations is essential to find the right match.

Global company: In a global company operation are fully integrated across the different countries in

which it has bases. Working practices and processes will be the same although management styles

may vary for the local culture. A strong unifying corporate culture is usually present, and a strategy

of global marketing assumes all customers are nearly the same - so little or no local variation is

required e.g. Coca-Cola.

Multi-domestic company: Here subsidiaries in foreign countries have a fair level of independence in

product design and production e.g. Colgate in Brazil (special toothpaste). There is a high degree of

localisation with respect to management practices. Decision-making is decentralised and at the

national level because management must be able to respond on a local level.

Changing organisational forms

The organisational form adopted by a company will be influenced by its approach to international

business. If the extent of its international business is confined to just marketing without a local

presence (as in an office) then the approach will be different to a company that operates in a

number of locations with employees on the ground locally. One can also expect a different

organisational structure for a truly global company from that of a multi-domestic company.

Cultural distance

We have looked at diverse workplace behaviour, such as individualism vs. collectivism or uncertainty

avoidance, resulting from cultural differences. Now diversity in workplace culture doesn't affect all

companies - simply because they do not actually have offices in overseas locations. However, most

companies today want to engage in international business even if they do not have offices in

overseas locations - they especially want to market their products as widely across the globe as

possible. To this end, consideration of cultural distance is important. Cultural distance is the extent

of the challenge a company faces when selling in overseas markets.

Corporate approaches to international business

At the heart of corporate approaches to international business is understanding on how value is

created through cross-border activities. This requires skills in analysing and critically evaluating the

company's strategy and its competitive environment. Sometimes international business does call for

operating in multiple overseas locations. The organisational issues and the complexity of managing

geographically distributed locations should not be underestimated. The best internationalisation

strategies can fail because the organisation hasn't understood how to internationalise, particularly

from a cultural perspective. An understanding of various organisational forms available to

multinational corporations is essential to find the right match.

Global company: In a global company operation are fully integrated across the different countries in

which it has bases. Working practices and processes will be the same although management styles

may vary for the local culture. A strong unifying corporate culture is usually present, and a strategy

of global marketing assumes all customers are nearly the same - so little or no local variation is

required e.g. Coca-Cola.

Multi-domestic company: Here subsidiaries in foreign countries have a fair level of independence in

product design and production e.g. Colgate in Brazil (special toothpaste). There is a high degree of

localisation with respect to management practices. Decision-making is decentralised and at the

national level because management must be able to respond on a local level.

Changing organisational forms

The organisational form adopted by a company will be influenced by its approach to international

business. If the extent of its international business is confined to just marketing without a local

presence (as in an office) then the approach will be different to a company that operates in a

number of locations with employees on the ground locally. One can also expect a different

organisational structure for a truly global company from that of a multi-domestic company.

The ethnocentric view

Ethnocentrism is a view of the world through the benchmark of one’s own culture. According to

Deresky (2016) it is the belief held by some companies that their management practices are best,

irrespective of the country in which they are applied. It entirely ignores local or regional culture,

including its ethical and moral values.

In an ethnocentric approach, typically decision-making and control mechanisms are heavily

centralised (i.e. head office controlled) with local operations modelled on those in the home country.

Local staff tend to be at the lower end of the hierarchy with the top end dominated by managers

from the home country. In effect, the structure and culture of the company's home country are

imposed on the local context. When locals are given senior positions, perhaps because there is a skill

shortage and there aren't suitable candidates from the home country, they are expected to reflect

the culture of the company's home country. It should be noted that this approach is not restricted to

Western multinationals. For instance, if you take Wipro, the Indian IT company, the vast majority of

its senior managers in overseas locations are Indian.

The polycentric view

This approach makes a deliberate attempt to overcome one’s own cultural background and

limitations and tries to understand other cultures. It retains core cultural identity but displays

‘openness’ and seeks to adapt its identity to other cultures.

The approach is the opposite of ethnocentric. The assumption is that local people know what is best

and can inform organisational strategy. Structurally, the organisation is similar to a loose federation

of quasi-independent subsidiaries, and it can be hard to tell that the parent company is foreign.

Decision-making is decentralised and managers in the foreign subsidiaries will almost always be

locals. So local managers who are most knowledgeable about local conditions make decisions locally.

Local structures and business conventions are used.

The geocentric view

A geocentric approach is one in which there is a high degree of adaptation to foreign markets with

little discernible national bias. Haberberg and Rieple (2012) state that in a geocentric approach,

corporate headquarters make decisions on financial planning and control, but human resourcing

decisions are made by local managers - who make these decisions on the basis of the best person for

the job, irrespective of nationality. The local manager himself may be local, from the parent

company's country or from a third country.

A geocentric approach reflects a truly global culture in which subsidiaries work in collaboration with

the corporate head office. In this type of company, annual profits tend to be redistributed globally.

This is in contrast to ethnocentric approaches where profits are repatriated to the ‘home’ country,

or polycentric approaches where they are retained by the subsidiary.

For those companies beginning their journey of internationalisation, we have noted that venturing

first into countries with similar cultures isn't necessarily the best approach. We examined the

importance of understanding cultural distance, particularly in the context of marketing strategies.

For those companies, who do operate out of multiple overseas locations, we considered the

ethnocentric, polycentric and geocentric approaches to management. The next lesson looks at the

role of national culture, language and communication in managing internationally.

Ethnocentrism is a view of the world through the benchmark of one’s own culture. According to

Deresky (2016) it is the belief held by some companies that their management practices are best,

irrespective of the country in which they are applied. It entirely ignores local or regional culture,

including its ethical and moral values.

In an ethnocentric approach, typically decision-making and control mechanisms are heavily

centralised (i.e. head office controlled) with local operations modelled on those in the home country.

Local staff tend to be at the lower end of the hierarchy with the top end dominated by managers

from the home country. In effect, the structure and culture of the company's home country are

imposed on the local context. When locals are given senior positions, perhaps because there is a skill

shortage and there aren't suitable candidates from the home country, they are expected to reflect

the culture of the company's home country. It should be noted that this approach is not restricted to

Western multinationals. For instance, if you take Wipro, the Indian IT company, the vast majority of

its senior managers in overseas locations are Indian.

The polycentric view

This approach makes a deliberate attempt to overcome one’s own cultural background and

limitations and tries to understand other cultures. It retains core cultural identity but displays

‘openness’ and seeks to adapt its identity to other cultures.

The approach is the opposite of ethnocentric. The assumption is that local people know what is best

and can inform organisational strategy. Structurally, the organisation is similar to a loose federation

of quasi-independent subsidiaries, and it can be hard to tell that the parent company is foreign.

Decision-making is decentralised and managers in the foreign subsidiaries will almost always be

locals. So local managers who are most knowledgeable about local conditions make decisions locally.

Local structures and business conventions are used.

The geocentric view

A geocentric approach is one in which there is a high degree of adaptation to foreign markets with

little discernible national bias. Haberberg and Rieple (2012) state that in a geocentric approach,

corporate headquarters make decisions on financial planning and control, but human resourcing

decisions are made by local managers - who make these decisions on the basis of the best person for

the job, irrespective of nationality. The local manager himself may be local, from the parent

company's country or from a third country.

A geocentric approach reflects a truly global culture in which subsidiaries work in collaboration with

the corporate head office. In this type of company, annual profits tend to be redistributed globally.

This is in contrast to ethnocentric approaches where profits are repatriated to the ‘home’ country,

or polycentric approaches where they are retained by the subsidiary.

For those companies beginning their journey of internationalisation, we have noted that venturing

first into countries with similar cultures isn't necessarily the best approach. We examined the

importance of understanding cultural distance, particularly in the context of marketing strategies.

For those companies, who do operate out of multiple overseas locations, we considered the

ethnocentric, polycentric and geocentric approaches to management. The next lesson looks at the

role of national culture, language and communication in managing internationally.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The role of language in culture

Language is the fundamental means of communication between individuals. Not only does it

facilitate social interaction, but it facilitates business. Language is the most fundamental and

discernible difference between cultures.

Language, perception and preference

For anyone who has worked in international business, it is noticeable that the way people think is

similar within a culture - obviously not across all issues but there are distinct similarities in the broad

way of thinking within a culture. For example, moral judgements are often broadly the same from

people of a particular culture.

Language can influence the way an individual, group or community perceives the world, which in

turn influences the way a society interacts with the world. Unconsciously, our language appears to

shape the way we perceive things and the thoughts we express.

Language creates cultural identity and also establishes preferences for people who speak the same

language. Some psychologists suggest that we might be naturally programmed to recognise and

prefer people who share our language, and that this preference develops early in life and continues

for life.

Business language and changing patterns

In today’s globalised business environment, one of the principal challenges confronting all managers

is that the manager will encounter a number of languages. This is due to increasing diversity in the

workforce, even within one country. Deresky (2016) gives some examples to illustrate this point. An

automobile manufacturing plant in Cologne will have assembly-line workers who speak Turkish and

Spanish as well as German. Whilst in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, many of the buyers and

traders are, in fact, Chinese. Furthermore, not all Arabs speak Arabic as their business language. In

Tunisia and Lebanon, French is the language of business.

Deresky (2016) concludes that international managers need either to develop a good command of

the local language or engage competent interpreters.

High-context vs. low-context languages

Hall (1997) first differentiated high-context from low-context languages. We examine the differences

next.

High-context languages are characterised by: Implicit speech: ambiguity is common (e.g. ‘reading

between the lines’) and directness is avoided (may be considered rude)

Body language is important to interpret speech

Precise wording of speech will consider the relationship between participants, the context and the

knowledge of the recipient

Collective group orientation: the speaker will use collective ‘we’ more than an individualistic ‘I’.

Examples of high-context languages are Japanese, Arabic and Chinese.

Language is the fundamental means of communication between individuals. Not only does it

facilitate social interaction, but it facilitates business. Language is the most fundamental and

discernible difference between cultures.

Language, perception and preference

For anyone who has worked in international business, it is noticeable that the way people think is

similar within a culture - obviously not across all issues but there are distinct similarities in the broad

way of thinking within a culture. For example, moral judgements are often broadly the same from

people of a particular culture.

Language can influence the way an individual, group or community perceives the world, which in

turn influences the way a society interacts with the world. Unconsciously, our language appears to

shape the way we perceive things and the thoughts we express.

Language creates cultural identity and also establishes preferences for people who speak the same

language. Some psychologists suggest that we might be naturally programmed to recognise and

prefer people who share our language, and that this preference develops early in life and continues

for life.

Business language and changing patterns

In today’s globalised business environment, one of the principal challenges confronting all managers

is that the manager will encounter a number of languages. This is due to increasing diversity in the

workforce, even within one country. Deresky (2016) gives some examples to illustrate this point. An

automobile manufacturing plant in Cologne will have assembly-line workers who speak Turkish and

Spanish as well as German. Whilst in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, many of the buyers and

traders are, in fact, Chinese. Furthermore, not all Arabs speak Arabic as their business language. In

Tunisia and Lebanon, French is the language of business.

Deresky (2016) concludes that international managers need either to develop a good command of

the local language or engage competent interpreters.

High-context vs. low-context languages

Hall (1997) first differentiated high-context from low-context languages. We examine the differences

next.

High-context languages are characterised by: Implicit speech: ambiguity is common (e.g. ‘reading

between the lines’) and directness is avoided (may be considered rude)

Body language is important to interpret speech

Precise wording of speech will consider the relationship between participants, the context and the

knowledge of the recipient

Collective group orientation: the speaker will use collective ‘we’ more than an individualistic ‘I’.

Examples of high-context languages are Japanese, Arabic and Chinese.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Low-context languages are characterised by:

Explicit speech: the aim is to be clearly understood whatever the context and whoever the recipient

Individual orientation: there will be more references to ‘I’ to indicate individualism and specific

responsibilities.

Examples of low-context languages are German, French, English and the Nordic languages.

Non-verbal communication

Communication is about more than the spoken and written word. A significant amount of our

communication is actually non-verbal. Every day, we respond to thousands of non-verbal cues and

behaviours. These include facial expressions, gestures, postures, eye gaze, and tone of voice.

Whenever me meet someone we process information about how they dress (smart, casual, scruffy

and so on), what they look like (e.g. hairstyle, facial features, height and build), and how they react

to us (e.g. handshake - is it firm?). Typically, as much as 60 per cent of communication is non-verbal.

PROXEMICS

An important aspect of body language, and something which the international manager needs to get

to grips with, is the concept of proxemics. Proxemics is the theory of using measurable distance and

space to make people feel comfortable and/or more relaxed while interacting with them. Proxemics

encompasses personal territory and physical territory.

Communication styles

According to Deresky (2016) cultural variety in communication styles is the result of a combination

of several factors, not just language and non-verbal communication. The factors are:

Attitudes: attitudes underpin the way people behave and the way they communication (both

sending and receiving messages). The international manager needs to avoid stereotyping and

instead learn how and why people behave differently.

Social organisation: reflects differences in group identity which may be tribal, regional or national.

Thought patterns: how people’s reason varies across cultures.

Role: different cultures have different views on the role of a manager.

Language: written and spoken languages can vary within as well as between countries.

Non-verbal communication: people communicate behaviour without having to speak.

Cross-cultural relationship development as well as collaboration and negotiation is strengthened

when the communication style of the particular culture is understood.

Defining ethical standards across the organisation

The approach adopted by the most ethical global organisations is to bring together the various

country managers regularly for open communication and collaboration in defining ethics and values.

These are then embodied in a business code of conduct for enforcement globally. There must be

representation across the diversity of cultures that makes up the organisation in these meetings.

Issues are debated and the organisation defines global ethical standards that address fundamental

issues of morality, integrity and fairness. The organisation must be able to identify those issues that

are not really fundamental ethical issues but issues concerning cultural norms - issues where local

Explicit speech: the aim is to be clearly understood whatever the context and whoever the recipient

Individual orientation: there will be more references to ‘I’ to indicate individualism and specific

responsibilities.

Examples of low-context languages are German, French, English and the Nordic languages.

Non-verbal communication

Communication is about more than the spoken and written word. A significant amount of our

communication is actually non-verbal. Every day, we respond to thousands of non-verbal cues and

behaviours. These include facial expressions, gestures, postures, eye gaze, and tone of voice.

Whenever me meet someone we process information about how they dress (smart, casual, scruffy

and so on), what they look like (e.g. hairstyle, facial features, height and build), and how they react

to us (e.g. handshake - is it firm?). Typically, as much as 60 per cent of communication is non-verbal.

PROXEMICS

An important aspect of body language, and something which the international manager needs to get

to grips with, is the concept of proxemics. Proxemics is the theory of using measurable distance and

space to make people feel comfortable and/or more relaxed while interacting with them. Proxemics

encompasses personal territory and physical territory.

Communication styles

According to Deresky (2016) cultural variety in communication styles is the result of a combination

of several factors, not just language and non-verbal communication. The factors are:

Attitudes: attitudes underpin the way people behave and the way they communication (both

sending and receiving messages). The international manager needs to avoid stereotyping and

instead learn how and why people behave differently.

Social organisation: reflects differences in group identity which may be tribal, regional or national.

Thought patterns: how people’s reason varies across cultures.

Role: different cultures have different views on the role of a manager.

Language: written and spoken languages can vary within as well as between countries.

Non-verbal communication: people communicate behaviour without having to speak.

Cross-cultural relationship development as well as collaboration and negotiation is strengthened

when the communication style of the particular culture is understood.

Defining ethical standards across the organisation

The approach adopted by the most ethical global organisations is to bring together the various

country managers regularly for open communication and collaboration in defining ethics and values.

These are then embodied in a business code of conduct for enforcement globally. There must be

representation across the diversity of cultures that makes up the organisation in these meetings.

Issues are debated and the organisation defines global ethical standards that address fundamental

issues of morality, integrity and fairness. The organisation must be able to identify those issues that

are not really fundamental ethical issues but issues concerning cultural norms - issues where local

decisions are called for. Global fundamental norms must be distinguished from cultural-specific

norms. The reality is that foreign ethical models and frameworks will be opposed if they are imposed

without consideration to local situations and cultural variations.

Global growth strategies

The corporate and competitive strategies of multinationals tend to be focused on growing the

business. The biggest growth opportunities are often outside of their home countries, particularly in

emerging markets. However, companies that look to grow markets overseas should do so after a

rigorous market assessment and must continually appraise the market, because the environment

can change rapidly. Many companies have failed spectacularly in their overseas ventures.

Global growth through marketing in new geographies doesn't always require a physical presence -

especially for consumer goods. Today e-commerce gives unrivalled and global reach and it is far

cheaper to market products through a website (and efficient logistics) than locating overseas.

Global growth is also achieved in other ways, particularly when a company is looking to acquire new

capabilities. For example through:

Mergers and acquisitions

Strategic alliances and joint ventures

Innovation.

Global collaboration in innovation

Innovation is increasingly a source of competitive advantage particularly in some sectors such as the

technology and pharmaceutical sectors. It is also the case that innovation increasingly straddles

multiple disciplines. Therefore, no single company, however large, has the breadth of competencies

to undertake such complex innovations. Companies therefore look to form external linkages to

integrate their resources and collaborate in innovation. The creation of the strategic innovation

network in itself can be innovative and often gives competitive advantage over rivals.

Combining and integrating knowledge and capabilities from diverse organisations to innovate is now

a strategy adopted by high-performing global companies. They companies are pursuing exploration

strategies by looking for ideas from outside, through strategic networks. Innovation partners would

include start-ups, suppliers, distributors, academia and even governments. It is a management

strategy adopted in many industry sectors by leading innovators.

The power of team working

Even in large global organisations, empowered teams in flat organisational structures are seen as a

means of overcoming the heavy bag and baggage of rules and bureaucracy which are so counter-

productive to creativity. The free-flowing nature of teams and its informality is ideal for creativity,

experimentation and learning - all of which are precursors for success in today's competitive global

environment. Teams outperform even the smartest of individuals acting alone. There is energy,

excitement, dynamism, creativity and collective learning in well-functioning teams - people

collaborate, building on the diverse contributions of others and come up with innovative ways of

doing things. However, the biggest benefits of teams arise when diverse, empowered teams are put

together. Diversity appears to trigger creativity, outstanding ideas and, often, ground-breaking

solutions. Empowerment is able to deliver creativity, speed and agility in fast changing markets

because teams operate largely autonomously.

norms. The reality is that foreign ethical models and frameworks will be opposed if they are imposed

without consideration to local situations and cultural variations.

Global growth strategies

The corporate and competitive strategies of multinationals tend to be focused on growing the

business. The biggest growth opportunities are often outside of their home countries, particularly in

emerging markets. However, companies that look to grow markets overseas should do so after a

rigorous market assessment and must continually appraise the market, because the environment

can change rapidly. Many companies have failed spectacularly in their overseas ventures.

Global growth through marketing in new geographies doesn't always require a physical presence -

especially for consumer goods. Today e-commerce gives unrivalled and global reach and it is far

cheaper to market products through a website (and efficient logistics) than locating overseas.

Global growth is also achieved in other ways, particularly when a company is looking to acquire new

capabilities. For example through:

Mergers and acquisitions

Strategic alliances and joint ventures

Innovation.

Global collaboration in innovation

Innovation is increasingly a source of competitive advantage particularly in some sectors such as the

technology and pharmaceutical sectors. It is also the case that innovation increasingly straddles

multiple disciplines. Therefore, no single company, however large, has the breadth of competencies

to undertake such complex innovations. Companies therefore look to form external linkages to

integrate their resources and collaborate in innovation. The creation of the strategic innovation

network in itself can be innovative and often gives competitive advantage over rivals.

Combining and integrating knowledge and capabilities from diverse organisations to innovate is now

a strategy adopted by high-performing global companies. They companies are pursuing exploration

strategies by looking for ideas from outside, through strategic networks. Innovation partners would

include start-ups, suppliers, distributors, academia and even governments. It is a management

strategy adopted in many industry sectors by leading innovators.

The power of team working

Even in large global organisations, empowered teams in flat organisational structures are seen as a

means of overcoming the heavy bag and baggage of rules and bureaucracy which are so counter-

productive to creativity. The free-flowing nature of teams and its informality is ideal for creativity,

experimentation and learning - all of which are precursors for success in today's competitive global

environment. Teams outperform even the smartest of individuals acting alone. There is energy,

excitement, dynamism, creativity and collective learning in well-functioning teams - people

collaborate, building on the diverse contributions of others and come up with innovative ways of

doing things. However, the biggest benefits of teams arise when diverse, empowered teams are put

together. Diversity appears to trigger creativity, outstanding ideas and, often, ground-breaking

solutions. Empowerment is able to deliver creativity, speed and agility in fast changing markets

because teams operate largely autonomously.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Characteristics of individuals in cross-cultural teams

Respect and leverage team differences

The value of cross-cultural and, in general, diverse teams is the multiple perspectives it brings

together. As a manager or team leader, respect these differing cultural perspectives. Indeed,

encourage team conversations that offer radical new insights or cultural perspectives. Leverage

team differences. Diversity and empowerment lead to creativity, speed and agility.

Managing conflict for creativity

The key to turning conflict into creativity appears to be getting away from a win-lose mentality.

Explain what this means, particularly in a cross-cultural team working context?

The author identifies five areas of conflict:

Different interpretations of facts or information

Lack of clear goals

Unclear processes or procedures

Low trust or broken relationships

Diverging values.

Team identity and bonding

Managers and team leaders must set the right environment to achieve team identity, bonding and

cohesion by: Facilitating people coming on board the team,facilitating people getting on with tasks,

organising for action and Facilitating evaluation and reflection.

Respect and leverage team differences

The value of cross-cultural and, in general, diverse teams is the multiple perspectives it brings

together. As a manager or team leader, respect these differing cultural perspectives. Indeed,

encourage team conversations that offer radical new insights or cultural perspectives. Leverage

team differences. Diversity and empowerment lead to creativity, speed and agility.

Managing conflict for creativity

The key to turning conflict into creativity appears to be getting away from a win-lose mentality.

Explain what this means, particularly in a cross-cultural team working context?

The author identifies five areas of conflict:

Different interpretations of facts or information

Lack of clear goals

Unclear processes or procedures

Low trust or broken relationships

Diverging values.

Team identity and bonding

Managers and team leaders must set the right environment to achieve team identity, bonding and

cohesion by: Facilitating people coming on board the team,facilitating people getting on with tasks,

organising for action and Facilitating evaluation and reflection.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Differing motivating factors

Ritchie and Martin (1999) identify 12 motivational drivers that are more pertinent to the

contemporary environment:

Interest

Achievement

Recognition

Self-development

Variety and change

Creativity

Power and Influence

Social contact

Money and tangible rewards

Structure

Relationships

Physical conditions.

Virtual and geographically distributed teams

Today with global and cross-cultural teams being commonplace, team members can be distributed

across a number of time zones (San Francisco to Paris to Bangalore to Beijing to Perth) under the

management of one leader. The leader may not see his/her team members frequently. Team

members themselves may not get to meet face-to-face. In these situations, team identity and

bonding are particularly important.

Technology is the cornerstone of communication across team members who are dispersed across

distributed locations. Teams, where communication and collaboration is enabled principally by

technology, are referred to as virtual teams.

Members of the virtual team may be drawn from the same organisation or from several different

collaborating organisations. They adopt project management practices for discipline and rigour in

working.

Global Human Resource Management (HRM)

Given the global nature of more and more companies today, the term international HRM (IHRM) is

often used to describe HRM strategies, policies and practices. The use of this term is an

acknowledgement of the complexities of operating in different countries. Not only must differences

in employment law be considered but also differences in custom and practice (i.e. local culture). The

latter is crucial because much of the knowledge about HRM comes from the US and it is often

assumed that this knowledge is widely applicable to other countries and regions.

Brewster and Mayrhofer (2013) stress that multinational corporations that wish to manage HRM

effectively across different countries need to understand the different national cultures they are

dealing with and their HRM policies need to be informed accordingly by this knowledge.

Ritchie and Martin (1999) identify 12 motivational drivers that are more pertinent to the

contemporary environment:

Interest

Achievement

Recognition

Self-development

Variety and change

Creativity

Power and Influence

Social contact

Money and tangible rewards

Structure

Relationships

Physical conditions.

Virtual and geographically distributed teams

Today with global and cross-cultural teams being commonplace, team members can be distributed

across a number of time zones (San Francisco to Paris to Bangalore to Beijing to Perth) under the

management of one leader. The leader may not see his/her team members frequently. Team

members themselves may not get to meet face-to-face. In these situations, team identity and

bonding are particularly important.

Technology is the cornerstone of communication across team members who are dispersed across

distributed locations. Teams, where communication and collaboration is enabled principally by

technology, are referred to as virtual teams.

Members of the virtual team may be drawn from the same organisation or from several different

collaborating organisations. They adopt project management practices for discipline and rigour in

working.

Global Human Resource Management (HRM)

Given the global nature of more and more companies today, the term international HRM (IHRM) is

often used to describe HRM strategies, policies and practices. The use of this term is an

acknowledgement of the complexities of operating in different countries. Not only must differences

in employment law be considered but also differences in custom and practice (i.e. local culture). The

latter is crucial because much of the knowledge about HRM comes from the US and it is often

assumed that this knowledge is widely applicable to other countries and regions.

Brewster and Mayrhofer (2013) stress that multinational corporations that wish to manage HRM

effectively across different countries need to understand the different national cultures they are

dealing with and their HRM policies need to be informed accordingly by this knowledge.

Global changes and existing organisational structures are making the work of the global HRM

function more complicated. In HRM, organisations must develop organisational structures that find

the right global-local balance so that they are effective in attracting the right people to meet

country-specific business objectives, such as identifying local acquisition opportunities or building

brands in the country, whilst aligning with global strategy.

The strategic focus of HRM

HRM has a strategic focus and there must tight alignment between HRM practices and corporate

strategy. HRM must support the corporate strategy in areas such as talent management or

development of core competencies.

The importance of strategic alignment is now widely accepted in Western multinationals although

the situation is less clear cut in a number of emerging markets where HRM principles are still in their

infancy.

So, what does strategic alignment refer to? It comprises two elements:

Vertical strategic alignment: Vertical strategic alignment is the process by which HR strategy, policies

and plans are aligned with an organisation’s strategic goals and objectives - in direct support of

corporate strategy.

Horizontal strategic alignment. Horizontal strategic alignment is the process by which functional

strategies, policies, plans and practices are aligned (or integrated) with each other. So, as an

example, what happens in recruitment and selection must be compatible with what happens in

learning and development - to develop targeted core competencies, for instance.

Global staffing and talent management

Global staffing is one of the principal concerns of the global HRM function. Staffing embraces all

aspects of HRM:

Roles are required (i.e. HR planning)

Hiring the right people to fill roles (i.e. recruitment and selection)

Induction, training and development of people (i.e. learning and development)

Performance management

Retention of talent and reward management.

Talent management and manager limitations

Although senior managers may appreciate the competitive value of talented employees, they are

often limited in their know-how on how best to acquire, utilise and develop talent. With the

pressures of running a business and delivering business results often in tough environments,

managers can easily become insular with narrow focus. Too many do not keep up to date with

developments in HR practices. To respond to an increasingly competitive global environment,

managers must continuously evaluate and embrace best practices in talent acquisition and talent

development. They need to adopt a mindset that understands that the new reality is that to gain

competitive advantage an organisation has to tap into a global talent pool. However, altering

managerial frames is difficult as it involves challenging some of the basic assumptions driving

management behaviour.

function more complicated. In HRM, organisations must develop organisational structures that find

the right global-local balance so that they are effective in attracting the right people to meet

country-specific business objectives, such as identifying local acquisition opportunities or building

brands in the country, whilst aligning with global strategy.

The strategic focus of HRM

HRM has a strategic focus and there must tight alignment between HRM practices and corporate

strategy. HRM must support the corporate strategy in areas such as talent management or

development of core competencies.

The importance of strategic alignment is now widely accepted in Western multinationals although

the situation is less clear cut in a number of emerging markets where HRM principles are still in their

infancy.

So, what does strategic alignment refer to? It comprises two elements:

Vertical strategic alignment: Vertical strategic alignment is the process by which HR strategy, policies

and plans are aligned with an organisation’s strategic goals and objectives - in direct support of

corporate strategy.

Horizontal strategic alignment. Horizontal strategic alignment is the process by which functional

strategies, policies, plans and practices are aligned (or integrated) with each other. So, as an

example, what happens in recruitment and selection must be compatible with what happens in

learning and development - to develop targeted core competencies, for instance.

Global staffing and talent management

Global staffing is one of the principal concerns of the global HRM function. Staffing embraces all

aspects of HRM:

Roles are required (i.e. HR planning)

Hiring the right people to fill roles (i.e. recruitment and selection)

Induction, training and development of people (i.e. learning and development)

Performance management

Retention of talent and reward management.

Talent management and manager limitations

Although senior managers may appreciate the competitive value of talented employees, they are

often limited in their know-how on how best to acquire, utilise and develop talent. With the

pressures of running a business and delivering business results often in tough environments,

managers can easily become insular with narrow focus. Too many do not keep up to date with

developments in HR practices. To respond to an increasingly competitive global environment,

managers must continuously evaluate and embrace best practices in talent acquisition and talent

development. They need to adopt a mindset that understands that the new reality is that to gain

competitive advantage an organisation has to tap into a global talent pool. However, altering

managerial frames is difficult as it involves challenging some of the basic assumptions driving

management behaviour.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 16

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.