M&A Strategies, HRM Practices, and Postmerger Integration: A Study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|26

|17781

|191

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the intricate relationship between mergers and acquisitions (M&As), postmerger integration (PMI), and human resource management (HRM) practices. It identifies three generic M&A strategies—annex & assimilate, harvest & protect, and link & promote—and aligns them with corresponding PMI outcomes: absorption, preservation, and symbiosis. Using the ability-motivation-opportunity (AMO) model, the study develops a conceptual framework that elucidates how AMO-enhancing HRM practices can effectively link M&A strategies with PMI outcomes. The report emphasizes the critical role of HRM in executing diverse tasks and strategies, clarifying how firms can configure their M&A-PMI relations for improved success. It highlights that even well-crafted M&A strategies may fall short without suitable AMO-enhancing HRM practices. This analysis offers valuable theoretical and practical contributions, charting a course for future research and application of the M&A-HRM-PMI triad.

Journal of Management

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –26

DOI: 10.1177/0149206315626270

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Linking Merger and Acquisition Strategies

to Postmerger Integration: A Configurational

Perspective of Human Resource Management

Nir N. Brueller

University of Haifa

Abraham Carmeli

Tel Aviv University

Gideon D. Markman

Colorado State University

The extant literature tends to frame mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and postmerger integra-

tion (PMI) as strategies and outcomes, but this framing often leaves their underlying processes

underexplored. We address this gap by redirecting attention to the view that M&As are largely

embedded in social and human practices. Our conceptual study identifies three generic M&A

strategies—annex & assimilate, harvest & protect, and link & promote—and matches them with

three well-known PMI outcomes (i.e., absorption, preservation, and symbiosis, respectively).

Using a configurational perspective and drawing upon the ability-motivation-opportunity

(AMO) model, we develop a conceptual framework that reveals why and how AMO-enhancing

human resource management (HRM) practices can link M&A strategies and PMI outcomes.

Finally, we elaborate on the theoretical and practical contributions and chart a course for

future inquiry and research applications for the M&A-HRM-PMI triad and its processes.

Keywords: merger and acquisition; postmerger integration; strategic human resource man-

agement; M&A-PMI relations; ability-, motivation-, and opportunity-enhancing

HRM practices

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feed-

back, as well as Esther Singer for her editorial comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We acknowledge the

financial support of the Eli Hurvitz Institute of Strategic Management at Tel Aviv University. The authors are listed

in alphabetical order.

Corresponding author: Nir N. Brueller, Faculty of Management, University of Haifa, 119 Abba Khoushy Ave.,

Haifa 31805, Israel.

Email: nbrueller@univ.haifa.ac.il

626270 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206315626270Journal of Management Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices

research-article2015

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –26

DOI: 10.1177/0149206315626270

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Linking Merger and Acquisition Strategies

to Postmerger Integration: A Configurational

Perspective of Human Resource Management

Nir N. Brueller

University of Haifa

Abraham Carmeli

Tel Aviv University

Gideon D. Markman

Colorado State University

The extant literature tends to frame mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and postmerger integra-

tion (PMI) as strategies and outcomes, but this framing often leaves their underlying processes

underexplored. We address this gap by redirecting attention to the view that M&As are largely

embedded in social and human practices. Our conceptual study identifies three generic M&A

strategies—annex & assimilate, harvest & protect, and link & promote—and matches them with

three well-known PMI outcomes (i.e., absorption, preservation, and symbiosis, respectively).

Using a configurational perspective and drawing upon the ability-motivation-opportunity

(AMO) model, we develop a conceptual framework that reveals why and how AMO-enhancing

human resource management (HRM) practices can link M&A strategies and PMI outcomes.

Finally, we elaborate on the theoretical and practical contributions and chart a course for

future inquiry and research applications for the M&A-HRM-PMI triad and its processes.

Keywords: merger and acquisition; postmerger integration; strategic human resource man-

agement; M&A-PMI relations; ability-, motivation-, and opportunity-enhancing

HRM practices

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feed-

back, as well as Esther Singer for her editorial comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We acknowledge the

financial support of the Eli Hurvitz Institute of Strategic Management at Tel Aviv University. The authors are listed

in alphabetical order.

Corresponding author: Nir N. Brueller, Faculty of Management, University of Haifa, 119 Abba Khoushy Ave.,

Haifa 31805, Israel.

Email: nbrueller@univ.haifa.ac.il

626270 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206315626270Journal of Management Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices

research-article2015

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

Firms use mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to accelerate their growth, seize and expand

on valuable capabilities, access assets (e.g., human capital) that are costly to imitate, and

even reduce competition—yet most M&A strategies fail to meet their objectives (Haleblian,

Devers, McNamara, Carpenter, & Davison, 2009). Acknowledging diverse factors that may

contribute to such failure (e.g., financial miscalculations, capability misalignment, and cross-

cultural mismatches), many studies and meta-analyses attribute the poor performance of

M&As to the intricate postmerger integration (PMI) phase (Datta, Pinches, & Narayanan,

1992; King, Dalton, Daily, & Covin, 2004). Indeed, the difficult-to-realize synergies and

destroyed value are among the reasons why M&A scholars are coupling their macrofocused

studies with microprocesses related to PMI (cf. Galpin & Herndon, 2014; Hitt, Harrison,

Ireland, & Best, 1998; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999).

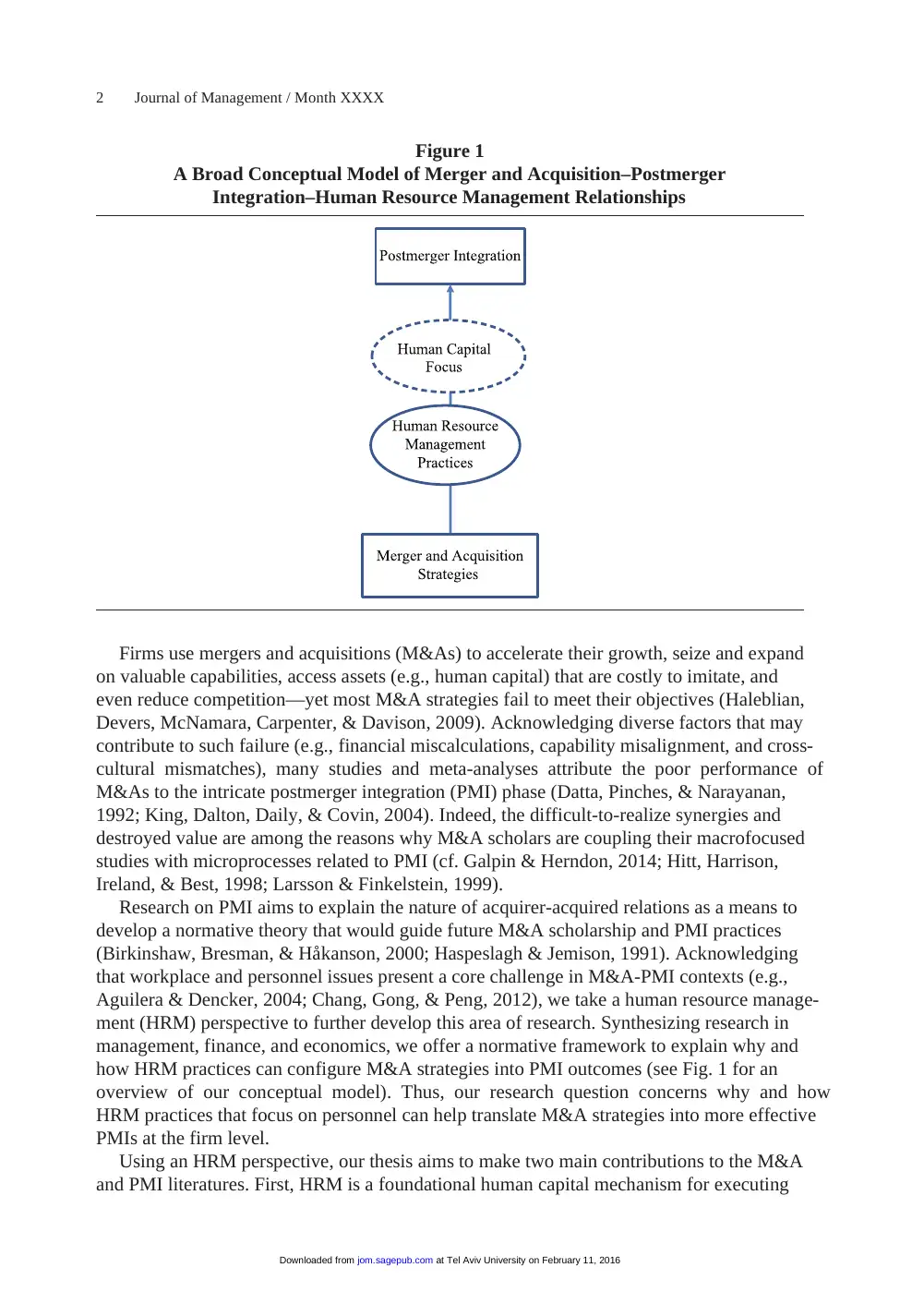

Research on PMI aims to explain the nature of acquirer-acquired relations as a means to

develop a normative theory that would guide future M&A scholarship and PMI practices

(Birkinshaw, Bresman, & Håkanson, 2000; Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991). Acknowledging

that workplace and personnel issues present a core challenge in M&A-PMI contexts (e.g.,

Aguilera & Dencker, 2004; Chang, Gong, & Peng, 2012), we take a human resource manage-

ment (HRM) perspective to further develop this area of research. Synthesizing research in

management, finance, and economics, we offer a normative framework to explain why and

how HRM practices can configure M&A strategies into PMI outcomes (see Fig. 1 for an

overview of our conceptual model). Thus, our research question concerns why and how

HRM practices that focus on personnel can help translate M&A strategies into more effective

PMIs at the firm level.

Using an HRM perspective, our thesis aims to make two main contributions to the M&A

and PMI literatures. First, HRM is a foundational human capital mechanism for executing

Figure 1

A Broad Conceptual Model of Merger and Acquisition–Postmerger

Integration–Human Resource Management Relationships

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Firms use mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to accelerate their growth, seize and expand

on valuable capabilities, access assets (e.g., human capital) that are costly to imitate, and

even reduce competition—yet most M&A strategies fail to meet their objectives (Haleblian,

Devers, McNamara, Carpenter, & Davison, 2009). Acknowledging diverse factors that may

contribute to such failure (e.g., financial miscalculations, capability misalignment, and cross-

cultural mismatches), many studies and meta-analyses attribute the poor performance of

M&As to the intricate postmerger integration (PMI) phase (Datta, Pinches, & Narayanan,

1992; King, Dalton, Daily, & Covin, 2004). Indeed, the difficult-to-realize synergies and

destroyed value are among the reasons why M&A scholars are coupling their macrofocused

studies with microprocesses related to PMI (cf. Galpin & Herndon, 2014; Hitt, Harrison,

Ireland, & Best, 1998; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999).

Research on PMI aims to explain the nature of acquirer-acquired relations as a means to

develop a normative theory that would guide future M&A scholarship and PMI practices

(Birkinshaw, Bresman, & Håkanson, 2000; Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991). Acknowledging

that workplace and personnel issues present a core challenge in M&A-PMI contexts (e.g.,

Aguilera & Dencker, 2004; Chang, Gong, & Peng, 2012), we take a human resource manage-

ment (HRM) perspective to further develop this area of research. Synthesizing research in

management, finance, and economics, we offer a normative framework to explain why and

how HRM practices can configure M&A strategies into PMI outcomes (see Fig. 1 for an

overview of our conceptual model). Thus, our research question concerns why and how

HRM practices that focus on personnel can help translate M&A strategies into more effective

PMIs at the firm level.

Using an HRM perspective, our thesis aims to make two main contributions to the M&A

and PMI literatures. First, HRM is a foundational human capital mechanism for executing

Figure 1

A Broad Conceptual Model of Merger and Acquisition–Postmerger

Integration–Human Resource Management Relationships

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices 3

diverse tasks and strategies. As an organizational infrastructure, HRM harnesses employees’

engagement to perform their jobs, manage resources, and fulfill firm-level objectives. HRM

practices are instrumental in addressing diverse workplace issues (e.g., recruiting, perfor-

mance assessment, job design and rotation, layoffs, and restructuring, to name a few). We

therefore theorize that an organizational infrastructure that aims to compound and extend

human effort is pivotal in M&A-PMI relations. Second, because an HRM perspective pro-

vides a fine-grained context that infuses microlevel processes into macrolevel theoretical

lenses, it should help clarify and explain how firms can match or configure their M&A-PMI

relations.

Building on the ability-motivation-opportunity (AMO) model (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg,

& Kalleberg, 2000; Blumberg & Pringle, 1982; Chang et al., 2012), we explain how HRM

practices mediate the M&A-PMI relations. We also elaborate on the reasons behind this phe-

nomenon and show how each M&A-HRM-PMI path takes on different functions, follows

distinct logics, and yields specific interdependencies between acquiring and acquired firms.

Interestingly, this configurational approach also clarifies why even well-crafted M&A strate-

gies and well-intended PMIs are unlikely to fully meet their objectives, unless they are

matched—or configured—by suitable AMO-enhancing HRM practices.

To the best of our knowledge, this is a first attempt to clarify why and how HRM practices

mediate the relations between M&A strategies and PMI outcomes. Indeed, past studies

tended to frame acquisitions as events (e.g., the increased use of event-study methodologies),

but the introduction of an HRM lens stresses that M&A-PMI relations are better viewed as

processes through which HRM practices play a critical role—starting with due diligence dur-

ing the predeal stages through the transition phases that bring M&A strategies into PMI

outcomes.

Background Research: M&As, PMI, and HRM

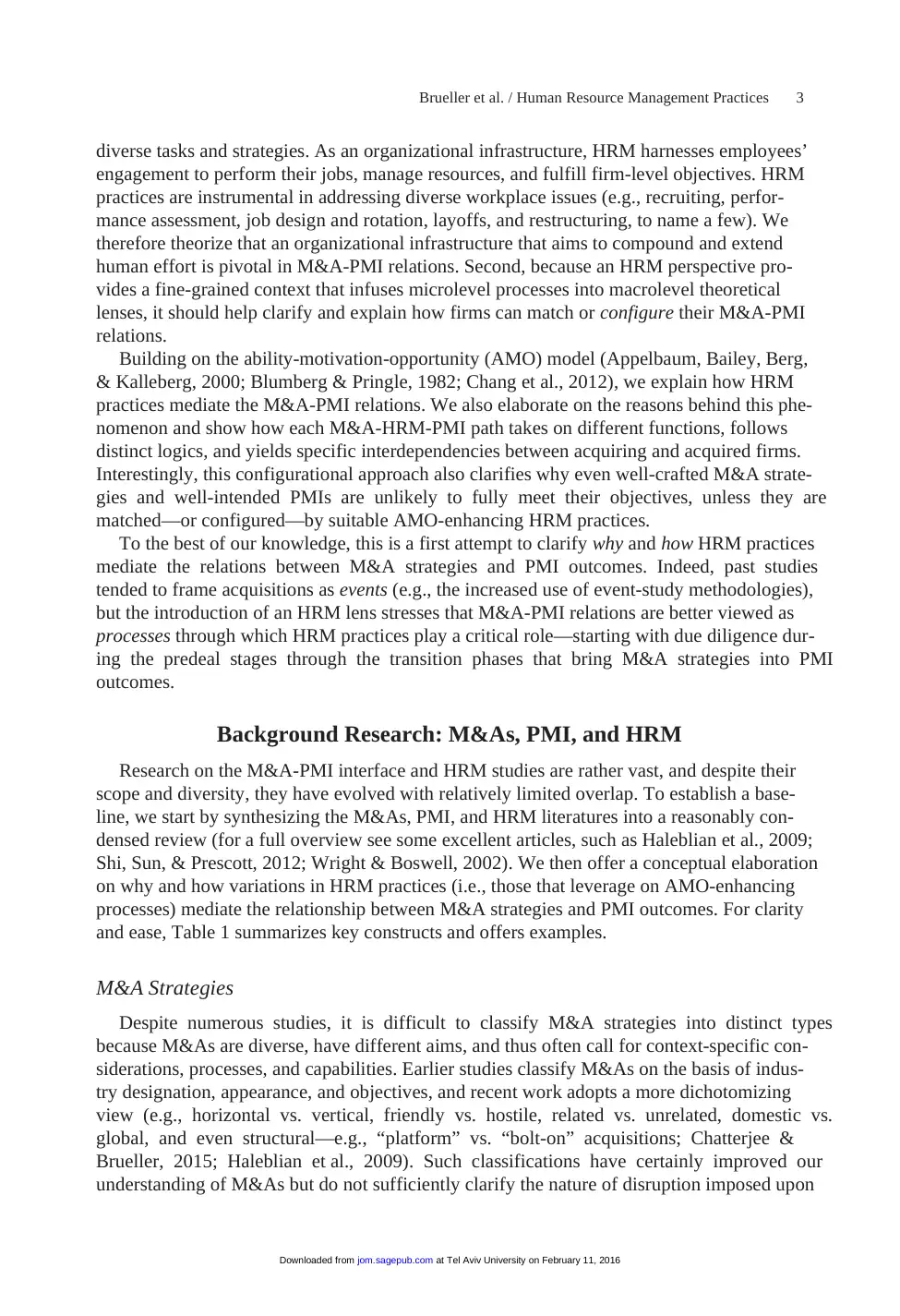

Research on the M&A-PMI interface and HRM studies are rather vast, and despite their

scope and diversity, they have evolved with relatively limited overlap. To establish a base-

line, we start by synthesizing the M&As, PMI, and HRM literatures into a reasonably con-

densed review (for a full overview see some excellent articles, such as Haleblian et al., 2009;

Shi, Sun, & Prescott, 2012; Wright & Boswell, 2002). We then offer a conceptual elaboration

on why and how variations in HRM practices (i.e., those that leverage on AMO-enhancing

processes) mediate the relationship between M&A strategies and PMI outcomes. For clarity

and ease, Table 1 summarizes key constructs and offers examples.

M&A Strategies

Despite numerous studies, it is difficult to classify M&A strategies into distinct types

because M&As are diverse, have different aims, and thus often call for context-specific con-

siderations, processes, and capabilities. Earlier studies classify M&As on the basis of indus-

try designation, appearance, and objectives, and recent work adopts a more dichotomizing

view (e.g., horizontal vs. vertical, friendly vs. hostile, related vs. unrelated, domestic vs.

global, and even structural—e.g., “platform” vs. “bolt-on” acquisitions; Chatterjee &

Brueller, 2015; Haleblian et al., 2009). Such classifications have certainly improved our

understanding of M&As but do not sufficiently clarify the nature of disruption imposed upon

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

diverse tasks and strategies. As an organizational infrastructure, HRM harnesses employees’

engagement to perform their jobs, manage resources, and fulfill firm-level objectives. HRM

practices are instrumental in addressing diverse workplace issues (e.g., recruiting, perfor-

mance assessment, job design and rotation, layoffs, and restructuring, to name a few). We

therefore theorize that an organizational infrastructure that aims to compound and extend

human effort is pivotal in M&A-PMI relations. Second, because an HRM perspective pro-

vides a fine-grained context that infuses microlevel processes into macrolevel theoretical

lenses, it should help clarify and explain how firms can match or configure their M&A-PMI

relations.

Building on the ability-motivation-opportunity (AMO) model (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg,

& Kalleberg, 2000; Blumberg & Pringle, 1982; Chang et al., 2012), we explain how HRM

practices mediate the M&A-PMI relations. We also elaborate on the reasons behind this phe-

nomenon and show how each M&A-HRM-PMI path takes on different functions, follows

distinct logics, and yields specific interdependencies between acquiring and acquired firms.

Interestingly, this configurational approach also clarifies why even well-crafted M&A strate-

gies and well-intended PMIs are unlikely to fully meet their objectives, unless they are

matched—or configured—by suitable AMO-enhancing HRM practices.

To the best of our knowledge, this is a first attempt to clarify why and how HRM practices

mediate the relations between M&A strategies and PMI outcomes. Indeed, past studies

tended to frame acquisitions as events (e.g., the increased use of event-study methodologies),

but the introduction of an HRM lens stresses that M&A-PMI relations are better viewed as

processes through which HRM practices play a critical role—starting with due diligence dur-

ing the predeal stages through the transition phases that bring M&A strategies into PMI

outcomes.

Background Research: M&As, PMI, and HRM

Research on the M&A-PMI interface and HRM studies are rather vast, and despite their

scope and diversity, they have evolved with relatively limited overlap. To establish a base-

line, we start by synthesizing the M&As, PMI, and HRM literatures into a reasonably con-

densed review (for a full overview see some excellent articles, such as Haleblian et al., 2009;

Shi, Sun, & Prescott, 2012; Wright & Boswell, 2002). We then offer a conceptual elaboration

on why and how variations in HRM practices (i.e., those that leverage on AMO-enhancing

processes) mediate the relationship between M&A strategies and PMI outcomes. For clarity

and ease, Table 1 summarizes key constructs and offers examples.

M&A Strategies

Despite numerous studies, it is difficult to classify M&A strategies into distinct types

because M&As are diverse, have different aims, and thus often call for context-specific con-

siderations, processes, and capabilities. Earlier studies classify M&As on the basis of indus-

try designation, appearance, and objectives, and recent work adopts a more dichotomizing

view (e.g., horizontal vs. vertical, friendly vs. hostile, related vs. unrelated, domestic vs.

global, and even structural—e.g., “platform” vs. “bolt-on” acquisitions; Chatterjee &

Brueller, 2015; Haleblian et al., 2009). Such classifications have certainly improved our

understanding of M&As but do not sufficiently clarify the nature of disruption imposed upon

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

acquisition parties, nor do they elaborate on the changes M&As impress on processes, opera-

tion, and HRM practices.

Following more nascent work, we deviate from a dichotomous view and group M&A

strategies into three main types—annex & assimilate, harvest & protect, and link & promote

acquisitions—chiefly on the basis of operational complexity, implications for PMI, and

HRM needs (Brueller, Carmeli, & Drori, 2014; Galpin & Herndon, 2014; Haleblian et al.,

2009; Koller, Goedhart, & Wessels, 2010). We describe each of the three M&A strategies in

more detail and offer examples shortly. As a preview, the annex & assimilate acquisitions

focus on absorbing targets’ assets, the harvest & protect acquisitions aim to capture and inte-

grate capabilities, and the link & promote acquisitions seek to cocreate boundary-spanning,

interfirm synergistic ties.

Table 1

Merger and Acquisition–Postmerger Integration–Human Resource Management

Relationships: Construct Labels, Functions, Definitions, and Examples

Merger and

Acquisition Strategies Annex & Assimilate Harvest & Protect Link & Promote

Merger and acquisition

goals

Absorbing assets

(primarily tangible) from

targets

Capturing and preserving

intangible assets

(e.g., capabilities,

partnerships) from

targets

Linking self-interest to shared

interest by cocreating

boundary-spanning

opportunities for both firms

as they operate independently

Strategic and

operational

leadership held by

. . .

Acquirer Target holds some

strategic and

operational power, but

acquirer sets the tone

Both targets and acquirers hold

ample strategic power and

operational leadership

PMI Outcomes Absorption Preservation Symbiosis

Examples The merger of United–

Continental Airlines

Cisco’s acquisition of

IronPort and Linksys

EMC’s acquisition of VMware

Autonomy of acquired

target

None (target is dissolved) Moderate and usually

operational and tactical

High and strategic

Relationship power Asymmetrical: All power

held by acquirer

Moderate: Most power

held by acquirer

Symmetrical and synergistic

Interfirm trust Minimal Moderate High

Human Resource

Management

Practices Ability Ability & Motivation

Ability, Motivation, &

Opportunity

Examples Recruitment, selection,

training

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Performance and

development

programs, competitive

pay systems, upward

career mobility

Flexible job designs, cross-

firm engagement programs,

transparent management

Practices designed

to . . .

Enhance personnel skills

and abilities of personnel

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Enhance motivation of

personnel

Empower employee to engage at

higher levels across both firms

Human capital focus Removal of redundancies

and integration of human

capital

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Personnel retention and

capability alignment

Reciprocal empowerment and

cause-based programs that

transcend firm boundaries

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

acquisition parties, nor do they elaborate on the changes M&As impress on processes, opera-

tion, and HRM practices.

Following more nascent work, we deviate from a dichotomous view and group M&A

strategies into three main types—annex & assimilate, harvest & protect, and link & promote

acquisitions—chiefly on the basis of operational complexity, implications for PMI, and

HRM needs (Brueller, Carmeli, & Drori, 2014; Galpin & Herndon, 2014; Haleblian et al.,

2009; Koller, Goedhart, & Wessels, 2010). We describe each of the three M&A strategies in

more detail and offer examples shortly. As a preview, the annex & assimilate acquisitions

focus on absorbing targets’ assets, the harvest & protect acquisitions aim to capture and inte-

grate capabilities, and the link & promote acquisitions seek to cocreate boundary-spanning,

interfirm synergistic ties.

Table 1

Merger and Acquisition–Postmerger Integration–Human Resource Management

Relationships: Construct Labels, Functions, Definitions, and Examples

Merger and

Acquisition Strategies Annex & Assimilate Harvest & Protect Link & Promote

Merger and acquisition

goals

Absorbing assets

(primarily tangible) from

targets

Capturing and preserving

intangible assets

(e.g., capabilities,

partnerships) from

targets

Linking self-interest to shared

interest by cocreating

boundary-spanning

opportunities for both firms

as they operate independently

Strategic and

operational

leadership held by

. . .

Acquirer Target holds some

strategic and

operational power, but

acquirer sets the tone

Both targets and acquirers hold

ample strategic power and

operational leadership

PMI Outcomes Absorption Preservation Symbiosis

Examples The merger of United–

Continental Airlines

Cisco’s acquisition of

IronPort and Linksys

EMC’s acquisition of VMware

Autonomy of acquired

target

None (target is dissolved) Moderate and usually

operational and tactical

High and strategic

Relationship power Asymmetrical: All power

held by acquirer

Moderate: Most power

held by acquirer

Symmetrical and synergistic

Interfirm trust Minimal Moderate High

Human Resource

Management

Practices Ability Ability & Motivation

Ability, Motivation, &

Opportunity

Examples Recruitment, selection,

training

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Performance and

development

programs, competitive

pay systems, upward

career mobility

Flexible job designs, cross-

firm engagement programs,

transparent management

Practices designed

to . . .

Enhance personnel skills

and abilities of personnel

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Enhance motivation of

personnel

Empower employee to engage at

higher levels across both firms

Human capital focus Removal of redundancies

and integration of human

capital

As in left cell, plus: As in left cells, plus:

Personnel retention and

capability alignment

Reciprocal empowerment and

cause-based programs that

transcend firm boundaries

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices 5

Annex & assimilate M&As. These acquisitions consume a target firm in its entirety or

reap core assets while dissolving redundant units, dated assets, and/or unneeded personnel

(Brueller et al., 2014). Acquirers aim to consolidate market power by annexing and digesting

targets’ core assets, and when merging parties are of equal size, their integration increases

in complexity (Chakravarthy & Lorange, 2007). When acquirers are exceptionally large and

targets are relatively small, both integration and digestion are reasonably simple, swift, and

fairly undisruptive. For instance, the global Danish cleaning company, Integrated Service

Solutions, has grown mostly by acquiring small local cleaning firms and quickly assimilat-

ing them (Horovitz, 2004). Integrated Service Solutions does not change itself substantively

but instead applies and enforces its own strategic planning, financial controls, culture, and

HRM systems throughout its absorbed targets (Chakravarthy & Lorange). When acquirers

and targets are large, even if their business models are quite similar—as is often seen in com-

modity industries, such as steel or oil and gas—the homogenization process is appreciably

more complex (e.g., BP’s merger with Arco and Amoco, Exxon with Mobil, and Chevron

with Texaco).

Under the “mergers of equals” scenario—especially where parties are quite sizable, have

a wide customer interface, and seek to combine most of their assets—complexity can quickly

become even more daunting. Consider, for instance, the 2010 merger of United and

Continental Airlines, which required the integration of two global networks, eight major

hubs, and 5,500 daily flights serving nearly 400 destinations. This complexity explains why

5 years later, United continued to grapple with myriad integration problems, including hob-

bled operations, angry passengers, and soured relations with employees. Another example is

the $30 billion merger between Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz that created pharmaceutical com-

pany Novartis. The combined firm opted to craft new strategies, processes, and capabilities

rather than adhere to those of either of its predecessors. The new strategy focused on life

sciences (i.e., nutrition, pharmaceuticals, and agriproducts), while the $7 billion Ciba

Specialty Chemicals business was spun off in 1997. The new processes included structuring

R&D by therapeutics (rather than geographic area) and shifting the firm’s compensation

policy from a system based on seniority to one based on performance across all departments

and managerial levels. These new capabilities entailed the creation of Novartis’ oncology

franchise (cf. Koller et al., 2010).

Thus annex & assimilate acquisitions—especially the mergers of equals—are monumen-

tal undertakings, with far-reaching and long-lingering operational complexities. The process

of homogenizing two firms (or more) into one often necessitates the development of new

strategies, retooled operations, restructured systems, and reorganized business models

(Brueller et al., 2014; Zott, Amit, & Massa, 2011).

Harvest & protect M&As. Acquirers use such M&As to seize new capabilities, processes,

and key personnel in order to expand their product offerings, enhance asset utilization, lever-

age on talent (e.g., improve R&D performance), and gain access to new markets (Puranam,

Singh, & Chaudhuri, 2009). For example, such acquisitions give firms flexibility to reallo-

cate personnel to more productive tasks across functions to fulfill new strategic direction

(Swaminathan, Groening, Mittal, & Thomaz, 2014). In these cases, preserving acquired

capabilities—which are often embedded in personnel—takes precedence over efforts to gain

scale advantage. Firms seeking these M&As can pursue either small or large targets. Small

targets are often startups with capabilities critical for product or technology extension, but

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Annex & assimilate M&As. These acquisitions consume a target firm in its entirety or

reap core assets while dissolving redundant units, dated assets, and/or unneeded personnel

(Brueller et al., 2014). Acquirers aim to consolidate market power by annexing and digesting

targets’ core assets, and when merging parties are of equal size, their integration increases

in complexity (Chakravarthy & Lorange, 2007). When acquirers are exceptionally large and

targets are relatively small, both integration and digestion are reasonably simple, swift, and

fairly undisruptive. For instance, the global Danish cleaning company, Integrated Service

Solutions, has grown mostly by acquiring small local cleaning firms and quickly assimilat-

ing them (Horovitz, 2004). Integrated Service Solutions does not change itself substantively

but instead applies and enforces its own strategic planning, financial controls, culture, and

HRM systems throughout its absorbed targets (Chakravarthy & Lorange). When acquirers

and targets are large, even if their business models are quite similar—as is often seen in com-

modity industries, such as steel or oil and gas—the homogenization process is appreciably

more complex (e.g., BP’s merger with Arco and Amoco, Exxon with Mobil, and Chevron

with Texaco).

Under the “mergers of equals” scenario—especially where parties are quite sizable, have

a wide customer interface, and seek to combine most of their assets—complexity can quickly

become even more daunting. Consider, for instance, the 2010 merger of United and

Continental Airlines, which required the integration of two global networks, eight major

hubs, and 5,500 daily flights serving nearly 400 destinations. This complexity explains why

5 years later, United continued to grapple with myriad integration problems, including hob-

bled operations, angry passengers, and soured relations with employees. Another example is

the $30 billion merger between Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz that created pharmaceutical com-

pany Novartis. The combined firm opted to craft new strategies, processes, and capabilities

rather than adhere to those of either of its predecessors. The new strategy focused on life

sciences (i.e., nutrition, pharmaceuticals, and agriproducts), while the $7 billion Ciba

Specialty Chemicals business was spun off in 1997. The new processes included structuring

R&D by therapeutics (rather than geographic area) and shifting the firm’s compensation

policy from a system based on seniority to one based on performance across all departments

and managerial levels. These new capabilities entailed the creation of Novartis’ oncology

franchise (cf. Koller et al., 2010).

Thus annex & assimilate acquisitions—especially the mergers of equals—are monumen-

tal undertakings, with far-reaching and long-lingering operational complexities. The process

of homogenizing two firms (or more) into one often necessitates the development of new

strategies, retooled operations, restructured systems, and reorganized business models

(Brueller et al., 2014; Zott, Amit, & Massa, 2011).

Harvest & protect M&As. Acquirers use such M&As to seize new capabilities, processes,

and key personnel in order to expand their product offerings, enhance asset utilization, lever-

age on talent (e.g., improve R&D performance), and gain access to new markets (Puranam,

Singh, & Chaudhuri, 2009). For example, such acquisitions give firms flexibility to reallo-

cate personnel to more productive tasks across functions to fulfill new strategic direction

(Swaminathan, Groening, Mittal, & Thomaz, 2014). In these cases, preserving acquired

capabilities—which are often embedded in personnel—takes precedence over efforts to gain

scale advantage. Firms seeking these M&As can pursue either small or large targets. Small

targets are often startups with capabilities critical for product or technology extension, but

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

6 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

their growth is hindered by insufficient capital infrastructure, scale expertise, or managerial

know-how (Brueller, Segev, Ellis, & Carmeli, 2015; King, Slotegraaf, & Kesner, 2008). For

example, small biotech companies typically lack the sales channels, marketing budget, and

ties with physicians, patients, and regulators needed to bring their products to markets (Mark-

man & Waldron, 2014). Larger firms often acquire smaller ventures for their innovation capa-

bilities, which would be more expensive or too slow to develop internally (Puranam et al.).

Because harvest & protect acquisitions focus on seizing, preserving, and realizing capa-

bilities, which are often embedded in personnel, we later explain why these acquisitions

require distinctly more specialized and involved HRM practices (and different human capital

focus) than those needed for the annex & assimilate M&As.

Link & promote M&As. These M&As are particularly unique because rather than focus-

ing on acquiring assets or capabilities, the primary aim is to cocreate boundary-spanning

and interfirm shared value creation that accelerate the growth and strength of both acquiring

and acquired firms (Chakravarthy & Lorange, 2007). Also, instead of grafting capabilities

of a target firm or force-fitting R&D units onto an acquirer’s asset base, the link & promote

acquisitions aim to accelerate interfirm learning and renewal. It is a regenerative, relational

effort where both firms coleverage complementary assets, capabilities, and know-how (Hale-

blian et al., 2009; Kanter, 2009). Thus, these acquisitions require discipline and foresight

to ensure that targets remain operationally and strategically autonomous, independent, and

self-sufficient. Indeed, the alignment of resources between two parties with complementary

competencies is a major operational challenge, but when executed well, it can bring synergis-

tic gains to both parties (Capron, Dussauge, & Mitchell, 1998; King et al., 2008).

When link & promote acquirers protect and promote their targets’ autonomy, both parties

improve knowledge exchange, mutual learning, innovation, and cross-operational agility

(Haleblian et al., 2009; Karim & Mitchell, 2000). For example, EMC’s $635 million acquisi-

tion of VMware, a computer-server software pioneer, allowed EMC to modularize two func-

tions—storage and server virtualization—that were previously incompatible. This loose

postacquisition governance resembles an alliance or a federation and was viewed by

VMware’s CEO as an optimal management structure (Butler, 2015). Naturally, the concepts

of complementarity, boundary spanning, and synergy are not new (Aldrich & Herker, 1977),

but their execution—particularly in M&A-PMI contexts—remains a challenge. As we show

below, however, it can be alleviated by suitable HRM practices.

To recap, annex & assimilate M&As focus on absorbing targets’ assets and dissolving

redundancies, while harvest & protect acquisitions seek to capture and preserve targets’ capa-

bilities—especially unique processes and key personnel. Link & promote M&As are distinct,

as the cogeneration of interfirm ties, regenerative learning, and synergies among business

units means that parties seek shared value creation by maintaining operational autonomy

while working synchronously on boundary-spanning projects and objectives.

PMI

Recognizing that M&As often trigger substantial restructuring, research that traditionally

asked outcome-focused questions, such as “Which acquisition strategy is likely to succeed?”

(Chatterjee, 1986; Chatterjee & Lubatkin, 1990; Lubatkin, 1983, 1987; Porter, 1987; Seth,

1990), began to shift toward process-related questions, such as “What processes and internal

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

their growth is hindered by insufficient capital infrastructure, scale expertise, or managerial

know-how (Brueller, Segev, Ellis, & Carmeli, 2015; King, Slotegraaf, & Kesner, 2008). For

example, small biotech companies typically lack the sales channels, marketing budget, and

ties with physicians, patients, and regulators needed to bring their products to markets (Mark-

man & Waldron, 2014). Larger firms often acquire smaller ventures for their innovation capa-

bilities, which would be more expensive or too slow to develop internally (Puranam et al.).

Because harvest & protect acquisitions focus on seizing, preserving, and realizing capa-

bilities, which are often embedded in personnel, we later explain why these acquisitions

require distinctly more specialized and involved HRM practices (and different human capital

focus) than those needed for the annex & assimilate M&As.

Link & promote M&As. These M&As are particularly unique because rather than focus-

ing on acquiring assets or capabilities, the primary aim is to cocreate boundary-spanning

and interfirm shared value creation that accelerate the growth and strength of both acquiring

and acquired firms (Chakravarthy & Lorange, 2007). Also, instead of grafting capabilities

of a target firm or force-fitting R&D units onto an acquirer’s asset base, the link & promote

acquisitions aim to accelerate interfirm learning and renewal. It is a regenerative, relational

effort where both firms coleverage complementary assets, capabilities, and know-how (Hale-

blian et al., 2009; Kanter, 2009). Thus, these acquisitions require discipline and foresight

to ensure that targets remain operationally and strategically autonomous, independent, and

self-sufficient. Indeed, the alignment of resources between two parties with complementary

competencies is a major operational challenge, but when executed well, it can bring synergis-

tic gains to both parties (Capron, Dussauge, & Mitchell, 1998; King et al., 2008).

When link & promote acquirers protect and promote their targets’ autonomy, both parties

improve knowledge exchange, mutual learning, innovation, and cross-operational agility

(Haleblian et al., 2009; Karim & Mitchell, 2000). For example, EMC’s $635 million acquisi-

tion of VMware, a computer-server software pioneer, allowed EMC to modularize two func-

tions—storage and server virtualization—that were previously incompatible. This loose

postacquisition governance resembles an alliance or a federation and was viewed by

VMware’s CEO as an optimal management structure (Butler, 2015). Naturally, the concepts

of complementarity, boundary spanning, and synergy are not new (Aldrich & Herker, 1977),

but their execution—particularly in M&A-PMI contexts—remains a challenge. As we show

below, however, it can be alleviated by suitable HRM practices.

To recap, annex & assimilate M&As focus on absorbing targets’ assets and dissolving

redundancies, while harvest & protect acquisitions seek to capture and preserve targets’ capa-

bilities—especially unique processes and key personnel. Link & promote M&As are distinct,

as the cogeneration of interfirm ties, regenerative learning, and synergies among business

units means that parties seek shared value creation by maintaining operational autonomy

while working synchronously on boundary-spanning projects and objectives.

PMI

Recognizing that M&As often trigger substantial restructuring, research that traditionally

asked outcome-focused questions, such as “Which acquisition strategy is likely to succeed?”

(Chatterjee, 1986; Chatterjee & Lubatkin, 1990; Lubatkin, 1983, 1987; Porter, 1987; Seth,

1990), began to shift toward process-related questions, such as “What processes and internal

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices 7

infrastructures might facilitate capability transfer, cross-firm learning, new value creation,

and synergistic gains?” (Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999; Pablo,

1994). The conceptualization of PMI as M&A-derived outcomes stimulated diverse studies

(e.g., Cording, Christman, & King, 2008; Haleblian et al., 2009; Zollo & Singh, 2004), many

of which build on Haspeslagh and Jemison’s popular framework.

Extending earlier studies, Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991) argued that PMIs are marked

by two dimensions: acquirer-target interdependence and target’s autonomy. Then, by plot-

ting the two dimensions into a two-by-two matrix, they identified four main PMI outcomes:

absorption, preservation, symbiosis, and holding (Galpin & Herndon, 2014). PMI absorption

is most suitable when interdependence is high and a target’s assets are insensitive to complete

digestion. Acquirers should seek the PMI preservation when interdependence is low but a

target autonomy is critical (e.g., to preserve capabilities) and seek PMI symbiosis when both

interdependence and target’s autonomy are high. The PMI holding entails no integration per

se, and it accounts for less than 10% of all deals. Therefore, following other M&A studies,

we henceforth focus on the first three PMIs: absorption, preservation, and symbiosis (cf.

Brueller et al., 2014; Ellis, 2004; Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988; Schweiger, 2002).

An important takeaway from PMI research is its conceptual evolution. Initially, PMIs

were underdefined, but Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (1991) introduction of the acquirer-target

interdependence and target’s autonomy dimensions allowed scholars to define PMIs with

greater precision. Indeed, the integration processes associated with absorption, preservation,

and symbiosis differ quite profoundly.

HRM and Human Capital

Going beyond administrative tasks, such as labor relations, payroll, and compliance,

HRM focuses on diverse issues pertaining to workforce management (Lepak & Snell, 2002),

and we suggest that discussion of personnel and HRM should coincide with strategic choices.

Indeed, abundant research corroborates that HRM can improve organizational processes and

effectiveness (e.g., B. E. Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, 2006;

Huselid, 1995; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Wright, Dunford, & Snell, 2001; Wright, Gardner,

Moynihan, & Allen, 2005). Furthermore, years of scholarly effort to unpack various employ-

ment architectures have led to the development of several HRM taxonomies depicting how

organizations convert human capital into organizational outcomes (cf. Delaney & Huselid,

1996; Guest, 1997; Huselid; Ichniowski, Shaw, & Prennushi, 1997; Jackson, Schuler, &

Jiang, 2014; Lepak & Snell).

This rich literature is summarized in numerous review articles (cf. B. E. Becker &

Huselid, 1998; Delery & Shaw, 2001; Jiang, Takeuchi, & Lepak, 2013). To remain within

reasonable bounds, we briefly elaborate on one area of HRM research that is especially

germane to the M&A-PMI interface—namely, the AMO (ability-motivation-opportunity)

model. As recapped by Jiang, Lepak, Hu, and Baer’s (2012) meta-analysis based on 116

articles (featuring 120 samples representing a total of 31,463 organizations), ability- or

skill-enhancing HRM practices include selection and hiring (Ahmad & Schroeder, 2003),

training (Akhtar, Ding, & Ge, 2008; Appleyard & Brown, 2001; Armstrong, Flood, Guthrie,

Liu, Mac-Gurtain, & Mkamwa, 2010), staffing and recruiting (Bartrajn, Stanton, Leggat,

Gasimir, & Fraser, 2007; Batt, Colvin, & Keefe, 2002), and development practices (Collins

& Smith, 2006). Motivation-enhancing HRM practices focus primarily on personnel

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

infrastructures might facilitate capability transfer, cross-firm learning, new value creation,

and synergistic gains?” (Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999; Pablo,

1994). The conceptualization of PMI as M&A-derived outcomes stimulated diverse studies

(e.g., Cording, Christman, & King, 2008; Haleblian et al., 2009; Zollo & Singh, 2004), many

of which build on Haspeslagh and Jemison’s popular framework.

Extending earlier studies, Haspeslagh and Jemison (1991) argued that PMIs are marked

by two dimensions: acquirer-target interdependence and target’s autonomy. Then, by plot-

ting the two dimensions into a two-by-two matrix, they identified four main PMI outcomes:

absorption, preservation, symbiosis, and holding (Galpin & Herndon, 2014). PMI absorption

is most suitable when interdependence is high and a target’s assets are insensitive to complete

digestion. Acquirers should seek the PMI preservation when interdependence is low but a

target autonomy is critical (e.g., to preserve capabilities) and seek PMI symbiosis when both

interdependence and target’s autonomy are high. The PMI holding entails no integration per

se, and it accounts for less than 10% of all deals. Therefore, following other M&A studies,

we henceforth focus on the first three PMIs: absorption, preservation, and symbiosis (cf.

Brueller et al., 2014; Ellis, 2004; Nahavandi & Malekzadeh, 1988; Schweiger, 2002).

An important takeaway from PMI research is its conceptual evolution. Initially, PMIs

were underdefined, but Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (1991) introduction of the acquirer-target

interdependence and target’s autonomy dimensions allowed scholars to define PMIs with

greater precision. Indeed, the integration processes associated with absorption, preservation,

and symbiosis differ quite profoundly.

HRM and Human Capital

Going beyond administrative tasks, such as labor relations, payroll, and compliance,

HRM focuses on diverse issues pertaining to workforce management (Lepak & Snell, 2002),

and we suggest that discussion of personnel and HRM should coincide with strategic choices.

Indeed, abundant research corroborates that HRM can improve organizational processes and

effectiveness (e.g., B. E. Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, 2006;

Huselid, 1995; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Wright, Dunford, & Snell, 2001; Wright, Gardner,

Moynihan, & Allen, 2005). Furthermore, years of scholarly effort to unpack various employ-

ment architectures have led to the development of several HRM taxonomies depicting how

organizations convert human capital into organizational outcomes (cf. Delaney & Huselid,

1996; Guest, 1997; Huselid; Ichniowski, Shaw, & Prennushi, 1997; Jackson, Schuler, &

Jiang, 2014; Lepak & Snell).

This rich literature is summarized in numerous review articles (cf. B. E. Becker &

Huselid, 1998; Delery & Shaw, 2001; Jiang, Takeuchi, & Lepak, 2013). To remain within

reasonable bounds, we briefly elaborate on one area of HRM research that is especially

germane to the M&A-PMI interface—namely, the AMO (ability-motivation-opportunity)

model. As recapped by Jiang, Lepak, Hu, and Baer’s (2012) meta-analysis based on 116

articles (featuring 120 samples representing a total of 31,463 organizations), ability- or

skill-enhancing HRM practices include selection and hiring (Ahmad & Schroeder, 2003),

training (Akhtar, Ding, & Ge, 2008; Appleyard & Brown, 2001; Armstrong, Flood, Guthrie,

Liu, Mac-Gurtain, & Mkamwa, 2010), staffing and recruiting (Bartrajn, Stanton, Leggat,

Gasimir, & Fraser, 2007; Batt, Colvin, & Keefe, 2002), and development practices (Collins

& Smith, 2006). Motivation-enhancing HRM practices focus primarily on personnel

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

retention and capability alignment through the aid of compensation systems (Bartrajn et al.;

Batt & Colvin, 2011), career-enhancing practices (Beltran-Martin, Roca-Puig, Escrig-Tena,

& Bou-Llusar, 2008), and performance and development programs (Yang & Lin, 2009).

And finally, opportunity-enhancing HRM practices form opportunity-spawning contexts

and infrastructures through commitment, empowerment, and cause-based programs where

personnel can further develop and accelerate organizational learning. Such practices might

entail decentralized structures and information-sharing protocols (Katou & Budhwar, 2006);

empowerment, engagement, and networking programs (Cabello-Medina, Lopez-Cabrales,

& Valle-Cabrera, 2011); grievance and voice mechanisms (Delaney & Huselid, 1996); and

rotational assignments, to name a few.

Evidence shows that AMO-enhancing HRM practices improve diverse firm-level out-

comes, such as processes, operations, and financial performance (cf. Appelbaum et al., 2000;

Bailey, Berg, & Sandy, 2001; Batt & Colvin, 2011; Batt et al., 2002; Boxall & Purcell, 2008;

Delery & Shaw, 2001; Gardner, Wright, & Moynihan, 2011; Gerhart, 2007; Huselid, 1995;

Jiang et al., 2012; Katz, Kochan, & Weber, 1985; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Lepak, Liao,

Chung, & Harden, 2006; Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, 2009; Subramony, 2009). Our assess-

ment of this scholarship is that AMO-enhancing HRM practices are a strong organizational

modality to address the economic, social, and operational complexities that M&As demand

and PMIs create.

Increasingly, several HRM studies focus on human capital—for example, personnel

knowledge, skills, ability, creativity, intelligence, judgment, and wisdom that produce indi-

vidual and/or organizational value (cf. B. E. Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Carmeli & Schaubroeck,

2005; Nyberg & Wright, 2015; Wright, Coff, & Moliterno, 2014). We view human capital as

a means to convert personnel-level capacity and effort into organizational-level outcomes.

For example, boundary-spanning effort and firm wealth creation are increased when different

human capital types are combined and matched by or configured with cospecialized organi-

zational resources and capabilities (Mahoney & Kor, 2015). Building on such scholarship

and the view that microprocesses and macro-outcomes create opportunities to address meso-

level processes (Cappelli & Scherer, 1991; Nyberg & Wright), we theorize that understand-

ing human capital at the individual level—and matching and configuring those with

organizational capabilities—can shed light on firm-level processes and outcomes.

Specifically, we blend micro- and macroviews and evince that HRM practices that tap into

and leverage on human capital can catapult M&A strategies into PMI outcomes (Nyberg,

Moliterno, Hale, & Lepak, 2014; Ployhart, Nyberg, Reilly, & Maltarich, 2014).

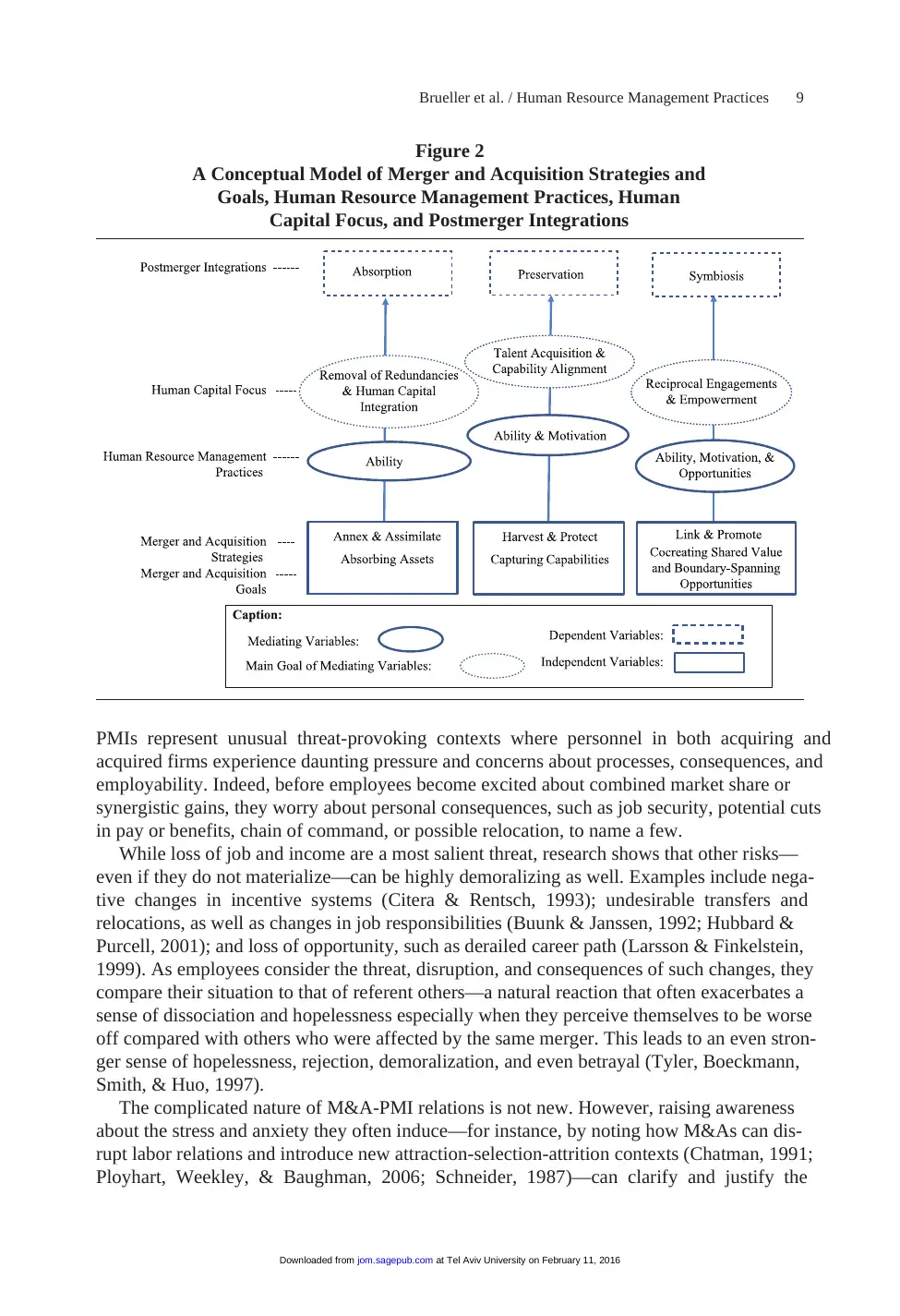

Having introduced (albeit briefly) the main parts of our conceptual model, the next section

elaborates on and integrates these points into a more detailed conceptual framework (see Figure

2). To recall, our thesis is that each distinct M&A-PMI path is mediated by suitable HRM prac-

tices. Figure 2 offers a configuration view that depicts how firms leverage their HRM practices

to align their M&A strategies with suitable PMIs (Fiss, 2007).

Conceptual Development

We should reemphasize that even the best-crafted M&A strategies and well-achieved PMIs

are rather disruptive and tend to produce substantial uncertainty, identity issues, and stress that

affect employees, suppliers, buyers, and even rivals. To clarify, M&A strategies and their

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

retention and capability alignment through the aid of compensation systems (Bartrajn et al.;

Batt & Colvin, 2011), career-enhancing practices (Beltran-Martin, Roca-Puig, Escrig-Tena,

& Bou-Llusar, 2008), and performance and development programs (Yang & Lin, 2009).

And finally, opportunity-enhancing HRM practices form opportunity-spawning contexts

and infrastructures through commitment, empowerment, and cause-based programs where

personnel can further develop and accelerate organizational learning. Such practices might

entail decentralized structures and information-sharing protocols (Katou & Budhwar, 2006);

empowerment, engagement, and networking programs (Cabello-Medina, Lopez-Cabrales,

& Valle-Cabrera, 2011); grievance and voice mechanisms (Delaney & Huselid, 1996); and

rotational assignments, to name a few.

Evidence shows that AMO-enhancing HRM practices improve diverse firm-level out-

comes, such as processes, operations, and financial performance (cf. Appelbaum et al., 2000;

Bailey, Berg, & Sandy, 2001; Batt & Colvin, 2011; Batt et al., 2002; Boxall & Purcell, 2008;

Delery & Shaw, 2001; Gardner, Wright, & Moynihan, 2011; Gerhart, 2007; Huselid, 1995;

Jiang et al., 2012; Katz, Kochan, & Weber, 1985; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Lepak, Liao,

Chung, & Harden, 2006; Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, 2009; Subramony, 2009). Our assess-

ment of this scholarship is that AMO-enhancing HRM practices are a strong organizational

modality to address the economic, social, and operational complexities that M&As demand

and PMIs create.

Increasingly, several HRM studies focus on human capital—for example, personnel

knowledge, skills, ability, creativity, intelligence, judgment, and wisdom that produce indi-

vidual and/or organizational value (cf. B. E. Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Carmeli & Schaubroeck,

2005; Nyberg & Wright, 2015; Wright, Coff, & Moliterno, 2014). We view human capital as

a means to convert personnel-level capacity and effort into organizational-level outcomes.

For example, boundary-spanning effort and firm wealth creation are increased when different

human capital types are combined and matched by or configured with cospecialized organi-

zational resources and capabilities (Mahoney & Kor, 2015). Building on such scholarship

and the view that microprocesses and macro-outcomes create opportunities to address meso-

level processes (Cappelli & Scherer, 1991; Nyberg & Wright), we theorize that understand-

ing human capital at the individual level—and matching and configuring those with

organizational capabilities—can shed light on firm-level processes and outcomes.

Specifically, we blend micro- and macroviews and evince that HRM practices that tap into

and leverage on human capital can catapult M&A strategies into PMI outcomes (Nyberg,

Moliterno, Hale, & Lepak, 2014; Ployhart, Nyberg, Reilly, & Maltarich, 2014).

Having introduced (albeit briefly) the main parts of our conceptual model, the next section

elaborates on and integrates these points into a more detailed conceptual framework (see Figure

2). To recall, our thesis is that each distinct M&A-PMI path is mediated by suitable HRM prac-

tices. Figure 2 offers a configuration view that depicts how firms leverage their HRM practices

to align their M&A strategies with suitable PMIs (Fiss, 2007).

Conceptual Development

We should reemphasize that even the best-crafted M&A strategies and well-achieved PMIs

are rather disruptive and tend to produce substantial uncertainty, identity issues, and stress that

affect employees, suppliers, buyers, and even rivals. To clarify, M&A strategies and their

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices 9

PMIs represent unusual threat-provoking contexts where personnel in both acquiring and

acquired firms experience daunting pressure and concerns about processes, consequences, and

employability. Indeed, before employees become excited about combined market share or

synergistic gains, they worry about personal consequences, such as job security, potential cuts

in pay or benefits, chain of command, or possible relocation, to name a few.

While loss of job and income are a most salient threat, research shows that other risks—

even if they do not materialize—can be highly demoralizing as well. Examples include nega-

tive changes in incentive systems (Citera & Rentsch, 1993); undesirable transfers and

relocations, as well as changes in job responsibilities (Buunk & Janssen, 1992; Hubbard &

Purcell, 2001); and loss of opportunity, such as derailed career path (Larsson & Finkelstein,

1999). As employees consider the threat, disruption, and consequences of such changes, they

compare their situation to that of referent others—a natural reaction that often exacerbates a

sense of dissociation and hopelessness especially when they perceive themselves to be worse

off compared with others who were affected by the same merger. This leads to an even stron-

ger sense of hopelessness, rejection, demoralization, and even betrayal (Tyler, Boeckmann,

Smith, & Huo, 1997).

The complicated nature of M&A-PMI relations is not new. However, raising awareness

about the stress and anxiety they often induce—for instance, by noting how M&As can dis-

rupt labor relations and introduce new attraction-selection-attrition contexts (Chatman, 1991;

Ployhart, Weekley, & Baughman, 2006; Schneider, 1987)—can clarify and justify the

Figure 2

A Conceptual Model of Merger and Acquisition Strategies and

Goals, Human Resource Management Practices, Human

Capital Focus, and Postmerger Integrations

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

PMIs represent unusual threat-provoking contexts where personnel in both acquiring and

acquired firms experience daunting pressure and concerns about processes, consequences, and

employability. Indeed, before employees become excited about combined market share or

synergistic gains, they worry about personal consequences, such as job security, potential cuts

in pay or benefits, chain of command, or possible relocation, to name a few.

While loss of job and income are a most salient threat, research shows that other risks—

even if they do not materialize—can be highly demoralizing as well. Examples include nega-

tive changes in incentive systems (Citera & Rentsch, 1993); undesirable transfers and

relocations, as well as changes in job responsibilities (Buunk & Janssen, 1992; Hubbard &

Purcell, 2001); and loss of opportunity, such as derailed career path (Larsson & Finkelstein,

1999). As employees consider the threat, disruption, and consequences of such changes, they

compare their situation to that of referent others—a natural reaction that often exacerbates a

sense of dissociation and hopelessness especially when they perceive themselves to be worse

off compared with others who were affected by the same merger. This leads to an even stron-

ger sense of hopelessness, rejection, demoralization, and even betrayal (Tyler, Boeckmann,

Smith, & Huo, 1997).

The complicated nature of M&A-PMI relations is not new. However, raising awareness

about the stress and anxiety they often induce—for instance, by noting how M&As can dis-

rupt labor relations and introduce new attraction-selection-attrition contexts (Chatman, 1991;

Ployhart, Weekley, & Baughman, 2006; Schneider, 1987)—can clarify and justify the

Figure 2

A Conceptual Model of Merger and Acquisition Strategies and

Goals, Human Resource Management Practices, Human

Capital Focus, and Postmerger Integrations

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

decision to explore the M&A-PMI relations through the mediating lenses of HRM practices,

which is the next topic.

Annex & Assimilate—Ability-Enhancing HRM—PMI Absorption

As noted, annex & assimilate acquisitions aim to seize mostly tangible assets (e.g., real

estate, production facilities, intellectual property, and technology) while dissolving or selling

unneeded resources, including excess personnel. Under these M&As, acquired firms cease to

exist but acquirers frequently engage some of their personnel in order to better integrate and

utilize their tangible assets. Naturally, the absorption of personnel is a delicate and time-

consuming process requiring HRM managers to determine—often under time pressure and

budgetary constraints—which employees to retain, and how to integrate them, and which

ones to dismiss. Among the factors often considered are surplus or redundant corporate func-

tions involving management, marketing, information technology, legal, and, yes, even human

resource (HR) personnel. Moreover, acquirers rarely engage HRM executives in premerger

planning, which is a serious oversight given that most annex & assimilate M&As and PMI

absorption entail substantial downsizing (Siegel & Simons, 2007).

It is important to recognize, therefore, that ability-focused HRM practices entail a careful

screening of personnel in order to identify and retain those essential to asset integration while

decisively letting go of the rest. As further clarified below, ability-focused HRM practices

play a critical role in mediating the relationships between annex & assimilate acquisitions

and PMI absorption. Understanding that prescreening and early selection of personnel deter-

mine, to a large extent, the outcome of an acquisition sheds doubt on the common (and crude)

view that acquirers are merely applying indiscriminate cost-containment measures (Haleblian

et al., 2009; Schuler & Jackson, 2003). Our thesis, however, proposes that ability-focused

HRM practices are management tools that must be engaged early, during the due diligence

process prior to the merger, in order to carefully identify and select the skill sets needed to

lower the disruption and cost and to maximize the speed and efficacy of integration.

Many M&A studies and firms underestimate the critical role played by ability-focused

HRM in identifying, extracting, and retaining the right skills from acquired firms while

removing redundancies, curbing overcapacities, consolidating incongruent practices, and

eliminating excess assets (Galpin & Herndon, 2014). Returning to an earlier example, the

United–Continental merger eliminated not only redundant routs and hub services but also

600 front-office jobs and many back-office functions. Certainly, workforce morale is impor-

tant, especially during massive layoffs. Yet in the context of annex & assimilate strategies

and PMI absorption, the focus is on removing duplicate functions, addressing operational

integrations, and meeting payroll needs and contractual obligations. And because redundan-

cies increase costs, acquirers depend heavily on applying ability-focused HRM practices,

such as sorting for fit and mining the able from the less essential personnel.

According to the AMO model, ability-enhancing HRM practices allow acquirers to recruit

and select employees (from each firm) who have the right skills and attitude needed to com-

plete a merger (Delaney & Huselid, 1996). Relatedly, HRM practices such as retraining pro-

grams, selective hiring, and skill-enhancing training help to win the hearts and minds of

capable personnel from acquired firms. All of these practices are critical to improving morale

and raising and integrating the collective human capital base of acquirers (e.g., Cabello-

Medina et al., 2011; Takeuchi, Lepak, Wang, & Takeuchi, 2007; Yang & Lin, 2009; Youndt

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

decision to explore the M&A-PMI relations through the mediating lenses of HRM practices,

which is the next topic.

Annex & Assimilate—Ability-Enhancing HRM—PMI Absorption

As noted, annex & assimilate acquisitions aim to seize mostly tangible assets (e.g., real

estate, production facilities, intellectual property, and technology) while dissolving or selling

unneeded resources, including excess personnel. Under these M&As, acquired firms cease to

exist but acquirers frequently engage some of their personnel in order to better integrate and

utilize their tangible assets. Naturally, the absorption of personnel is a delicate and time-

consuming process requiring HRM managers to determine—often under time pressure and

budgetary constraints—which employees to retain, and how to integrate them, and which

ones to dismiss. Among the factors often considered are surplus or redundant corporate func-

tions involving management, marketing, information technology, legal, and, yes, even human

resource (HR) personnel. Moreover, acquirers rarely engage HRM executives in premerger

planning, which is a serious oversight given that most annex & assimilate M&As and PMI

absorption entail substantial downsizing (Siegel & Simons, 2007).

It is important to recognize, therefore, that ability-focused HRM practices entail a careful

screening of personnel in order to identify and retain those essential to asset integration while

decisively letting go of the rest. As further clarified below, ability-focused HRM practices

play a critical role in mediating the relationships between annex & assimilate acquisitions

and PMI absorption. Understanding that prescreening and early selection of personnel deter-

mine, to a large extent, the outcome of an acquisition sheds doubt on the common (and crude)

view that acquirers are merely applying indiscriminate cost-containment measures (Haleblian

et al., 2009; Schuler & Jackson, 2003). Our thesis, however, proposes that ability-focused

HRM practices are management tools that must be engaged early, during the due diligence

process prior to the merger, in order to carefully identify and select the skill sets needed to

lower the disruption and cost and to maximize the speed and efficacy of integration.

Many M&A studies and firms underestimate the critical role played by ability-focused

HRM in identifying, extracting, and retaining the right skills from acquired firms while

removing redundancies, curbing overcapacities, consolidating incongruent practices, and

eliminating excess assets (Galpin & Herndon, 2014). Returning to an earlier example, the

United–Continental merger eliminated not only redundant routs and hub services but also

600 front-office jobs and many back-office functions. Certainly, workforce morale is impor-

tant, especially during massive layoffs. Yet in the context of annex & assimilate strategies

and PMI absorption, the focus is on removing duplicate functions, addressing operational

integrations, and meeting payroll needs and contractual obligations. And because redundan-

cies increase costs, acquirers depend heavily on applying ability-focused HRM practices,

such as sorting for fit and mining the able from the less essential personnel.

According to the AMO model, ability-enhancing HRM practices allow acquirers to recruit

and select employees (from each firm) who have the right skills and attitude needed to com-

plete a merger (Delaney & Huselid, 1996). Relatedly, HRM practices such as retraining pro-

grams, selective hiring, and skill-enhancing training help to win the hearts and minds of

capable personnel from acquired firms. All of these practices are critical to improving morale

and raising and integrating the collective human capital base of acquirers (e.g., Cabello-

Medina et al., 2011; Takeuchi, Lepak, Wang, & Takeuchi, 2007; Yang & Lin, 2009; Youndt

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Brueller et al. / Human Resource Management Practices 11

& Snell, 2004). Teva Pharmaceutical Industries CEO Vigodman (2015) noted that they

refined their capability for screening and retaining only the most suitable employees and

teams from their targets.

Over and above removing redundancies on the basis of skills, ability-enhancing HRM

practices are useful for selecting a transition team; setting up integration timelines; communi-

cating rules, routines, and expectations; enforcing processes and milestones; and balancing

operational trade-offs while managing the integration of absorbed personnel. Similarly instru-

mental in dissolving a target’s autonomy is the role of ability-focused HRM in identifying and

preventing areas of friction and harmonizing cross-cultural issues, often by attracting, retain-

ing, and deploying the right personnel (while pruning others; Dhanaraj, Lyles, Steensma, &

Tihanyi, 2004). On the basis of this logic, we suggest the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Ability-enhancing HRM practices mediate the relationship between annex & assimi-

late strategies and PMI absorption.

Harvest & Protect—Ability- and Motivation-Enhancing HRM—PMI

Preservation

Harvest & protect acquisitions intend to harness and preserve the capabilities, partner-

ships, and other intangible assets of target firms. For instance, to preserve the capabilities and

vital partnerships of IronPort (a maker of products and services that protect enterprises

against Internet threats), Cisco enabled IronPort to operate almost as it did prior to the acqui-

sition. IronPort was grafted into Cisco’s security business unit by using a PMI preservation

(Yirrell, 2007). It comes as no surprise that harvest & protect acquisitions and PMI preserva-

tion are best paired with HRM practices aiming to safeguard and keep targets’ capabilities

intact so they can then be redeployed by acquirers. Considering the critical role played by

ability-enhancing HRM practices in removing redundancies and preserving human capital,

we suggest that when parties complement their ability-enhancing HRM effort with motiva-

tion-enhancing HRM practices, they can greatly strengthen personnel’s buy-in and, thus,

enable the harvest & protect acquisitions and their PMI preservation. There are several rea-

sons for this prediction.

First, while ability-enhancing HRM practices ensure that personnel possess appropriate

human capital skills, motivation-enhancing HRM practices tend to strengthen the associa-

tion between the work, intentions, effort, and even identity of employees with their rewards,

retention, and commitment. Practices such as performance and career development plans,

competitive pay and benefits, flexible work design, and job security tend to motivate

employees to engage at a higher level (Ryan & Deci, 2000). An important nuance to stress

at this point is that even when training improves individual skills and ability, these benefits

are more likely to produce firm-level outcomes when coupled with motivation-enhancing

HRM practices. This blending of practices tends to expand the abilities, skills, and motiva-

tion of employees (Tharenou, Saks, & Moore, 2007). And, of course, as engagement

increases among personnel, so does their resilience against disruptions, including those

stemming from acrimonious M&As. For instance, studies show that ability- and motivation-

enhancing HRM practices are associated with increased engagement levels and reduced

voluntary turnover (Batt et al., 2002; Gardner et al., 2011; Guthrie, 2001; Huselid, 1995;

Sun, Aryee, & Law, 2007).

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

& Snell, 2004). Teva Pharmaceutical Industries CEO Vigodman (2015) noted that they

refined their capability for screening and retaining only the most suitable employees and

teams from their targets.

Over and above removing redundancies on the basis of skills, ability-enhancing HRM

practices are useful for selecting a transition team; setting up integration timelines; communi-

cating rules, routines, and expectations; enforcing processes and milestones; and balancing

operational trade-offs while managing the integration of absorbed personnel. Similarly instru-

mental in dissolving a target’s autonomy is the role of ability-focused HRM in identifying and

preventing areas of friction and harmonizing cross-cultural issues, often by attracting, retain-

ing, and deploying the right personnel (while pruning others; Dhanaraj, Lyles, Steensma, &

Tihanyi, 2004). On the basis of this logic, we suggest the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Ability-enhancing HRM practices mediate the relationship between annex & assimi-

late strategies and PMI absorption.

Harvest & Protect—Ability- and Motivation-Enhancing HRM—PMI

Preservation

Harvest & protect acquisitions intend to harness and preserve the capabilities, partner-

ships, and other intangible assets of target firms. For instance, to preserve the capabilities and

vital partnerships of IronPort (a maker of products and services that protect enterprises

against Internet threats), Cisco enabled IronPort to operate almost as it did prior to the acqui-

sition. IronPort was grafted into Cisco’s security business unit by using a PMI preservation

(Yirrell, 2007). It comes as no surprise that harvest & protect acquisitions and PMI preserva-

tion are best paired with HRM practices aiming to safeguard and keep targets’ capabilities

intact so they can then be redeployed by acquirers. Considering the critical role played by

ability-enhancing HRM practices in removing redundancies and preserving human capital,

we suggest that when parties complement their ability-enhancing HRM effort with motiva-

tion-enhancing HRM practices, they can greatly strengthen personnel’s buy-in and, thus,

enable the harvest & protect acquisitions and their PMI preservation. There are several rea-

sons for this prediction.

First, while ability-enhancing HRM practices ensure that personnel possess appropriate

human capital skills, motivation-enhancing HRM practices tend to strengthen the associa-

tion between the work, intentions, effort, and even identity of employees with their rewards,

retention, and commitment. Practices such as performance and career development plans,

competitive pay and benefits, flexible work design, and job security tend to motivate

employees to engage at a higher level (Ryan & Deci, 2000). An important nuance to stress

at this point is that even when training improves individual skills and ability, these benefits

are more likely to produce firm-level outcomes when coupled with motivation-enhancing

HRM practices. This blending of practices tends to expand the abilities, skills, and motiva-

tion of employees (Tharenou, Saks, & Moore, 2007). And, of course, as engagement

increases among personnel, so does their resilience against disruptions, including those

stemming from acrimonious M&As. For instance, studies show that ability- and motivation-

enhancing HRM practices are associated with increased engagement levels and reduced

voluntary turnover (Batt et al., 2002; Gardner et al., 2011; Guthrie, 2001; Huselid, 1995;

Sun, Aryee, & Law, 2007).

at Tel Aviv University on February 11, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

12 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

Second, extant research shows that the combination of ability- and motivation-enhancing