Oral vs. LAI Antipsychotics: Metabolic Syndrome in Psychotic Disorders

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/30

|6

|5737

|364

Report

AI Summary

This research report investigates the prevalence and risk factors of metabolic syndrome (MetS) in patients with chronic psychotic disorders, specifically schizophrenia (Sz) and schizoaffective disorder (SzAff), treated with oral and long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics. The study, involving 151 patients, compares the metabolic health indices between Sz and SzAff patients and assesses the impact of different antipsychotic treatments on MetS. The findings indicate that SzAff diagnosis and higher antipsychotic doses are associated with increased MetS risk, while the mode of administration (oral vs. LAI) does not significantly influence MetS risk. The study identifies specific antipsychotics with higher MetS risk, such as quetiapine and clozapine, and highlights the importance of monitoring metabolic health in patients with severe mental illnesses. The research contributes to understanding the complex relationship between psychotic disorders, antipsychotic treatments, and metabolic complications.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

published: 16 January 2019

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00744

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 1 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

Edited by:

Andrea Fiorillo,

Università degliStudidella Campania

“LuigiVanvitelli” Naples, Italy

Reviewed by:

Francesco Bartoli,

Università deglistudidi Milano

Bicocca, Italy

Steve Simpson Jr,

The University of Melbourne, Australia

Beth McGinty,

Johns Hopkins University,

United States

*Correspondence:

Antonio Ventriglio

a.ventriglio@libero.it

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Psychosomatic Medicine,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychiatry

Received: 22 August 2018

Accepted: 17 December 2018

Published: 16 January 2019

Citation:

Ventriglio A, BaldessariniRJ, VitraniG,

Bonfitto I, Cecere AC, RinaldiA,

Petito A and Bellomo A (2019)

Metabolic Syndrome in Psychotic

Disorder Patients Treated With Oral

and Long-Acting Injected

Antipsychotics.

Front. Psychiatry 9:744.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00744

Metabolic Syndrome in Psychotic

Disorder Patients Treated With Oral

and Long-Acting Injected

Antipsychotics

Antonio Ventriglio1

*, Ross J. Baldessarini2,3, Giovanna Vitrani1, Iris Bonfitto1,

Angela Chiara Cecere1, Angelo Rinaldi1, Annamaria Petito1 and Antonello Bellomo1

1 Department of Clinicaland ExperimentalMedicine, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy,2 InternationalConsortium for

Psychotic & Mood Disorder Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, United States,3 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard

MedicalSchool, McLean Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Background: Severe mentalillnesses are associated with increased risks for metabolic

syndrome (MetS)and other medicaldisorders, often with unfavorable outcomes. MetS

may be more likely with schizoaffective disorder (SzAff)than schizophrenia (Sz).MetS

is associated with long-term antipsychotic drug treatment,but relative risk with orally

administered vs. long-acting injected (LAI) antipsychotics is uncertain.

Methods: Subjects (n = 151 with a DSM-IV-TR chronic psychotic disorder: 89 Sz, 62

SzAff),treated with oralor LAI antipsychotics were compared for risk ofMetS,initially

with bivariate comparisons and then by multivariate regression modeling.

Results: Aside from measures on which diagnosis of MetS is based, factors prelimina

associated with MetS included antipsychotic drug dose,“high-risk”antipsychotics

associated with weight-gain, older age and female sex. Defining factors associated w

diagnosis ofMetS ranked in multivariate regression as:higherfasting glucose,lower

LDL cholesterol,higherdiastolic blood pressure,and higherBMI. Risk of MetS with

antipsychotics ranked: quetiapine ≥ clozapine ≥ paliperidone ≥ olanzapine ≥ risper

≥ haloperidol≥ aripiprazole.Otherassociated risk factors in multivariate modeling

ranked: higher antipsychotic dose, older age, and SzAff diagnosis, but not oralvs. LAI

antipsychotics

Conclusions: SzAffdiagnosis and higher antipsychotic doses were associated with

MetS, whereas orally vs. injected antipsychotics did not differ in risk of MetS.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, antipsychotics, long-acting injected, schizoaffective, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Personswith severe mentalillnesseshave increased risk formetabolic disorders,including

metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipide

hypertension (1). Such disorders appear to be related to an unhealthy diet, lack of regul

adverse effects of psychotropic drugs,and possibly to undefined risk factors associated with the

illnesses themselves (2,3).Much of the research on this topic has involved patients diagnose

with chronic psychotic or mood disorders,particularly schizophrenia (Sz) and bipolar disorder

published: 16 January 2019

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00744

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 1 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

Edited by:

Andrea Fiorillo,

Università degliStudidella Campania

“LuigiVanvitelli” Naples, Italy

Reviewed by:

Francesco Bartoli,

Università deglistudidi Milano

Bicocca, Italy

Steve Simpson Jr,

The University of Melbourne, Australia

Beth McGinty,

Johns Hopkins University,

United States

*Correspondence:

Antonio Ventriglio

a.ventriglio@libero.it

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Psychosomatic Medicine,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychiatry

Received: 22 August 2018

Accepted: 17 December 2018

Published: 16 January 2019

Citation:

Ventriglio A, BaldessariniRJ, VitraniG,

Bonfitto I, Cecere AC, RinaldiA,

Petito A and Bellomo A (2019)

Metabolic Syndrome in Psychotic

Disorder Patients Treated With Oral

and Long-Acting Injected

Antipsychotics.

Front. Psychiatry 9:744.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00744

Metabolic Syndrome in Psychotic

Disorder Patients Treated With Oral

and Long-Acting Injected

Antipsychotics

Antonio Ventriglio1

*, Ross J. Baldessarini2,3, Giovanna Vitrani1, Iris Bonfitto1,

Angela Chiara Cecere1, Angelo Rinaldi1, Annamaria Petito1 and Antonello Bellomo1

1 Department of Clinicaland ExperimentalMedicine, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy,2 InternationalConsortium for

Psychotic & Mood Disorder Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, United States,3 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard

MedicalSchool, McLean Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Background: Severe mentalillnesses are associated with increased risks for metabolic

syndrome (MetS)and other medicaldisorders, often with unfavorable outcomes. MetS

may be more likely with schizoaffective disorder (SzAff)than schizophrenia (Sz).MetS

is associated with long-term antipsychotic drug treatment,but relative risk with orally

administered vs. long-acting injected (LAI) antipsychotics is uncertain.

Methods: Subjects (n = 151 with a DSM-IV-TR chronic psychotic disorder: 89 Sz, 62

SzAff),treated with oralor LAI antipsychotics were compared for risk ofMetS,initially

with bivariate comparisons and then by multivariate regression modeling.

Results: Aside from measures on which diagnosis of MetS is based, factors prelimina

associated with MetS included antipsychotic drug dose,“high-risk”antipsychotics

associated with weight-gain, older age and female sex. Defining factors associated w

diagnosis ofMetS ranked in multivariate regression as:higherfasting glucose,lower

LDL cholesterol,higherdiastolic blood pressure,and higherBMI. Risk of MetS with

antipsychotics ranked: quetiapine ≥ clozapine ≥ paliperidone ≥ olanzapine ≥ risper

≥ haloperidol≥ aripiprazole.Otherassociated risk factors in multivariate modeling

ranked: higher antipsychotic dose, older age, and SzAff diagnosis, but not oralvs. LAI

antipsychotics

Conclusions: SzAffdiagnosis and higher antipsychotic doses were associated with

MetS, whereas orally vs. injected antipsychotics did not differ in risk of MetS.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, antipsychotics, long-acting injected, schizoaffective, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Personswith severe mentalillnesseshave increased risk formetabolic disorders,including

metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipide

hypertension (1). Such disorders appear to be related to an unhealthy diet, lack of regul

adverse effects of psychotropic drugs,and possibly to undefined risk factors associated with the

illnesses themselves (2,3).Much of the research on this topic has involved patients diagnose

with chronic psychotic or mood disorders,particularly schizophrenia (Sz) and bipolar disorder

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Ventriglio et al. Metabolic Problems: Effects of Diagnosis and Treatment

(2,4–6).Few studies have compared physical health of subjects

diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (SzAff) to that of other

patients with other psychotic-disorder diagnoses,including Sz,

but SzAff patientsmay havea greaterrisk of MetS than

those with other major psychiatric disorders (6).SzAff patients

are characterized by emotionaland behavioralinstability over

time as well as psychoticfeatures,and often are treated

with relatively complex pharmacologicalregimens(7). Both

emotional instability and complex treatments may contribute to

an increased risk of metabolic disorders (1).

Also uncertain is whether specific types of medicines differ

appreciably in their associations with risks of metabolic disorders.

In particular,the extentto which relative metabolic risksof

modern or second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and their

long-acting injected (LAI) preparations differ from older or orally

administered antipsychotics remains uncertain (1, 8–10).

The preceding considerationsled us to compareclinical

measures, in particular indices of metabolic health, among SzAff

vs.Sz patient-subjects to identify factors associated specifically

with MetS, including comparison of orally administered vs. LAI

antipsychotics. We hypothesized that SzAff subjects would have

a higher risk of MetS than Sz subjects, and that the risk might be

lower with LAI antipsychotic treatments.

METHODS

From June 2014 to February 2017, we enrolled study subjects as

part of a program monitoring the health of psychotic disorder

patients attending the Day HospitalService for Severe Mental

Disorders in the Psychiatric Departmentat the University of

Foggia Medical Center. A total of 151 consecutive patients were

enrolled as study-subjects,including 89 diagnosed with Sz and

62 as SzAff by two expert clinicians (AB,AV) based on DSM-

IV-TR (Diagnostic and StatisticalManualof mentaldisorders-

Text Revision) criteria (11).Treatments were selected clinically

and included oralantipsychotics(n = 64, with or without

mood-stabilizers or antidepressants) as well as LAI antipsychotics

(n = 87, usually as monotherapy).

All subjects provided written informed consent to participate,

after study procedures approved by the University ofFoggia

medical center ethics committee were explained to them. Patients

were enrolled in a stable phase of their illness and treatments;

candidates who required psychiatric hospitalization, had revised

treatment protocols within the previous 6 months, were actively

abusing alcoholor drugs (confirmed by urine assays),or were

pregnant, were excluded from the study.

Currentpsychiatric morbidity was assessed and rated with

the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (12),and

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (13) by two experienced

psychiatrist-investigators (AB, AV). Raters were held unaware of

treatments given,and their ratings yielded high,independent,

interrateragreement(χ2 ≥ 0.90).Being considered “mildly

ill” corresponded to a PANSS totalscoreof ≤58 or BPRS

score of ≤31,“moderately ill” corresponded to PANSS ratings

of 59–75 or BPRS scoresof 32–40,“moderately severely ill”

corresponded to PANSS of 76–95 or BPRS of 41–53, and “severely

ill” corresponded to a PANSS of96–116 or BPRS of54–126

(12, 13).

We also collecteddata on: demographics(sex, age,

employmentstatus), current pharmacologicaltreatments

(oral or LAI antipsychotics,mood stabilizers[MSs], and

antidepressants[ADs]),and theirdoses;anthropometric and

metabolic measures (height [cm] and weight [kg] for body-m

index [BMI]),systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg),

pulse (beats/min); serum concentrations of fasting glucose (F

mg/dL),%-glycated hemoglobin (Hgb-A1c),totalcholesterol

(mg/dL),low density lipoproteins (LDL;mg/dL),high density

lipoproteins(HDL; mg/dL), triglycerides(mg/dL); waist

circumference(cm), electrocardiographicrate-corrected QT

repolarization interval(QTc,msec);serum levels ofprolactin

(ng/dL),thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH,mIU/L),and free

thyroxin and triiodothyronine. We also recorded adverse even

associated with treatment,and rated treatment-adherence with

the 30-item Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI-30) (14).

We rated subjectsfor the presenceof MetS defined by

current, revised International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criter

American Heart Association and InternationalAssociation for

the Study of Obesity (15,16).MetS required meeting ≥3 of the

following 5 criteria:[a] large waist circumference (≥102 cm in

men, ≥88 cm in women); [b] elevated serum triglycerides (≥

ng/dL); [c] low HDL-cholesterol (<40 mg/dL in men and <50 i

women); high blood pressure (≥130 mm Hg systolic or ≥85 m

diastolic);elevated glucose as fasting blood sugar (FBS >100

mg/dL).

To facilitate comparisons,we converted antipsychotic doses

to approximate oral daily mg-chlorpromazine-equivalents (CP

eq); LAI antipsychotic doses were estimated as total mg dose

days of injection cycles for conversion to CPZ-eq (17,18).For

MSs, we converted dosages to approximate daily mg-equivale

of lithium carbonate (Li-eq) (18, 19). Antidepressants were no

as being prescribed or not.

We compared measures collected among subjects diagnos

with SzAff and Sz,treated with LAIand oralantipsychotics,

emphasizing comparisonsof subjectswith vs.withoutMetS.

Data analyses used commercialstatisticalprograms (Statview-

5, SAS Corp.,Cary,North Carolina,USA for spreadsheets;

Stata.13.0,Stata Corp.,College Station,Texas,USA). Data are

presented as means ± standard deviation (SD)or with 95%

confidence intervals (CI),or as percentages (%),unless stated

otherwise. Continuous data were compared using nonparame

Mann-Whitneyrank-sum test(z-score)to avoid problems

of non-normaldistribution ofvalues,and categoricaldata

weretested with contingencytables(χ2). Factorsyielding

p < 0.10 in preliminary bivariate comparisons were considere

multivariate logistic regression modeling, with presence of Me

as the outcome measure.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Treatments

The 151 patient-subjects were aged 42.1 ± 12.4 years;52.9%

were men, 18.5% were employed. Diagnoses included Sz (n =

58.9%) and SzAff (n = 62; 41.1%). More men than women we

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 2 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

(2,4–6).Few studies have compared physical health of subjects

diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (SzAff) to that of other

patients with other psychotic-disorder diagnoses,including Sz,

but SzAff patientsmay havea greaterrisk of MetS than

those with other major psychiatric disorders (6).SzAff patients

are characterized by emotionaland behavioralinstability over

time as well as psychoticfeatures,and often are treated

with relatively complex pharmacologicalregimens(7). Both

emotional instability and complex treatments may contribute to

an increased risk of metabolic disorders (1).

Also uncertain is whether specific types of medicines differ

appreciably in their associations with risks of metabolic disorders.

In particular,the extentto which relative metabolic risksof

modern or second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and their

long-acting injected (LAI) preparations differ from older or orally

administered antipsychotics remains uncertain (1, 8–10).

The preceding considerationsled us to compareclinical

measures, in particular indices of metabolic health, among SzAff

vs.Sz patient-subjects to identify factors associated specifically

with MetS, including comparison of orally administered vs. LAI

antipsychotics. We hypothesized that SzAff subjects would have

a higher risk of MetS than Sz subjects, and that the risk might be

lower with LAI antipsychotic treatments.

METHODS

From June 2014 to February 2017, we enrolled study subjects as

part of a program monitoring the health of psychotic disorder

patients attending the Day HospitalService for Severe Mental

Disorders in the Psychiatric Departmentat the University of

Foggia Medical Center. A total of 151 consecutive patients were

enrolled as study-subjects,including 89 diagnosed with Sz and

62 as SzAff by two expert clinicians (AB,AV) based on DSM-

IV-TR (Diagnostic and StatisticalManualof mentaldisorders-

Text Revision) criteria (11).Treatments were selected clinically

and included oralantipsychotics(n = 64, with or without

mood-stabilizers or antidepressants) as well as LAI antipsychotics

(n = 87, usually as monotherapy).

All subjects provided written informed consent to participate,

after study procedures approved by the University ofFoggia

medical center ethics committee were explained to them. Patients

were enrolled in a stable phase of their illness and treatments;

candidates who required psychiatric hospitalization, had revised

treatment protocols within the previous 6 months, were actively

abusing alcoholor drugs (confirmed by urine assays),or were

pregnant, were excluded from the study.

Currentpsychiatric morbidity was assessed and rated with

the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (12),and

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (13) by two experienced

psychiatrist-investigators (AB, AV). Raters were held unaware of

treatments given,and their ratings yielded high,independent,

interrateragreement(χ2 ≥ 0.90).Being considered “mildly

ill” corresponded to a PANSS totalscoreof ≤58 or BPRS

score of ≤31,“moderately ill” corresponded to PANSS ratings

of 59–75 or BPRS scoresof 32–40,“moderately severely ill”

corresponded to PANSS of 76–95 or BPRS of 41–53, and “severely

ill” corresponded to a PANSS of96–116 or BPRS of54–126

(12, 13).

We also collecteddata on: demographics(sex, age,

employmentstatus), current pharmacologicaltreatments

(oral or LAI antipsychotics,mood stabilizers[MSs], and

antidepressants[ADs]),and theirdoses;anthropometric and

metabolic measures (height [cm] and weight [kg] for body-m

index [BMI]),systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg),

pulse (beats/min); serum concentrations of fasting glucose (F

mg/dL),%-glycated hemoglobin (Hgb-A1c),totalcholesterol

(mg/dL),low density lipoproteins (LDL;mg/dL),high density

lipoproteins(HDL; mg/dL), triglycerides(mg/dL); waist

circumference(cm), electrocardiographicrate-corrected QT

repolarization interval(QTc,msec);serum levels ofprolactin

(ng/dL),thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH,mIU/L),and free

thyroxin and triiodothyronine. We also recorded adverse even

associated with treatment,and rated treatment-adherence with

the 30-item Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI-30) (14).

We rated subjectsfor the presenceof MetS defined by

current, revised International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criter

American Heart Association and InternationalAssociation for

the Study of Obesity (15,16).MetS required meeting ≥3 of the

following 5 criteria:[a] large waist circumference (≥102 cm in

men, ≥88 cm in women); [b] elevated serum triglycerides (≥

ng/dL); [c] low HDL-cholesterol (<40 mg/dL in men and <50 i

women); high blood pressure (≥130 mm Hg systolic or ≥85 m

diastolic);elevated glucose as fasting blood sugar (FBS >100

mg/dL).

To facilitate comparisons,we converted antipsychotic doses

to approximate oral daily mg-chlorpromazine-equivalents (CP

eq); LAI antipsychotic doses were estimated as total mg dose

days of injection cycles for conversion to CPZ-eq (17,18).For

MSs, we converted dosages to approximate daily mg-equivale

of lithium carbonate (Li-eq) (18, 19). Antidepressants were no

as being prescribed or not.

We compared measures collected among subjects diagnos

with SzAff and Sz,treated with LAIand oralantipsychotics,

emphasizing comparisonsof subjectswith vs.withoutMetS.

Data analyses used commercialstatisticalprograms (Statview-

5, SAS Corp.,Cary,North Carolina,USA for spreadsheets;

Stata.13.0,Stata Corp.,College Station,Texas,USA). Data are

presented as means ± standard deviation (SD)or with 95%

confidence intervals (CI),or as percentages (%),unless stated

otherwise. Continuous data were compared using nonparame

Mann-Whitneyrank-sum test(z-score)to avoid problems

of non-normaldistribution ofvalues,and categoricaldata

weretested with contingencytables(χ2). Factorsyielding

p < 0.10 in preliminary bivariate comparisons were considere

multivariate logistic regression modeling, with presence of Me

as the outcome measure.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Treatments

The 151 patient-subjects were aged 42.1 ± 12.4 years;52.9%

were men, 18.5% were employed. Diagnoses included Sz (n =

58.9%) and SzAff (n = 62; 41.1%). More men than women we

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 2 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

Ventriglio et al. Metabolic Problems: Effects of Diagnosis and Treatment

diagnosed with Sz (χ2 = 6.76; p = 0.009). Treatments included

oralantipsychotics in 42.3%,and LAI antipsychotics in 57.7%

(none received both). Antipsychotics were combined with mood-

stabilizers (MSs) in only 14.5%,or with antidepressants (ADs)

in 12.3% (ranking by use: duloxetine > paroxetine > citalopram

or S-citalopram > sertraline).Both adjunctive treatments were

given selectively with oralantipsychotics,by 6.4- (MSs) or 7.0-

times more (ADs; both p ≤ 0.006) among SzAff than Sz subjects.

Antipsychotic doses averaged 313 ± 329 mg/day CPZ-eq,and

MS (carbamazepine,lithium carbonate,sodium valproate) total

daily Li-eq doses averaged 650 ± 244 mg. Overall, clinical ratings

averaged 75.0 ± 34.7 for PANSS and 51.6 ± 23.6 for BPRS; both

indicate moderate symptomatic severity, even though all patients

reported clinical and treatment stability for at least six continuous

preceding months. Prolonged, stable dosing assured that even the

LAI antipsychotics were at pharmacokinetic steady-state.

Subjectswho receivedLAI vs. oral antipsychoticshad

significantly lowerlevelsof symptomaticmorbidity.PANSS

scores were, respectively, 58.0 ± 27.6 vs. 98.1 ± 29.9, and BPRS

scores averaged 40.1 ± 15.0 vs. 67.1 ± 24.5 (z-scores = 7.76 and

6.85, both p < 0.0001).

No subject was considered to have a substance-use disorder,

as was supportedby urine drug assays,consistentwith

current substance abuse as an exclusion criterion. Adherence to

prescribed treatments was considered good,as supported by a

DAI-30 score of 9.64 ± 2.19 (of a total maximum of 30).There

was a moderate rate of reported,treatment-associated,adverse

events (19.8%),most of which involved motor slowing or mild

tremor.

Risk and Measures Associated With

Metabolic Syndrome

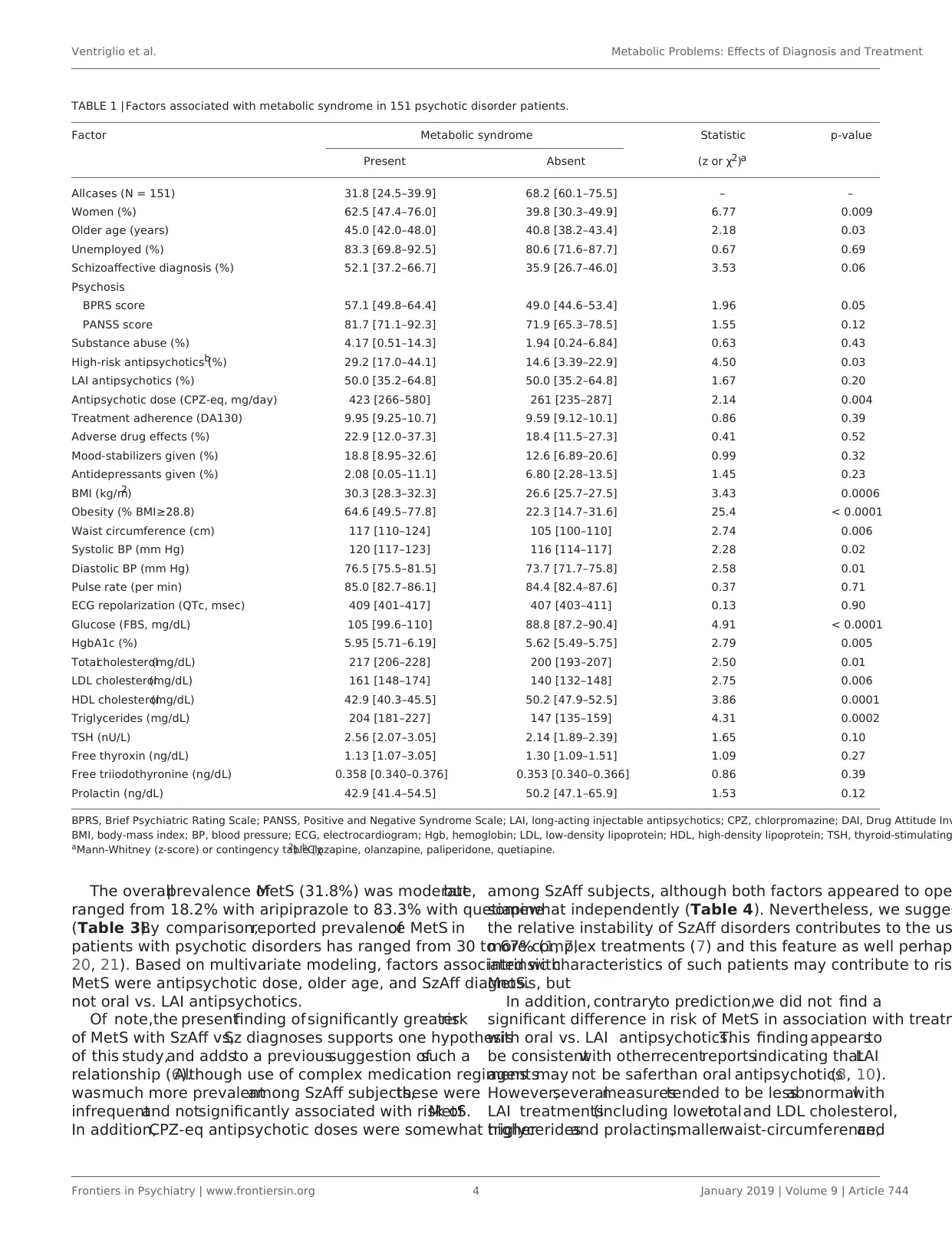

Of the entire sample,31.8% metdiagnostic criteria for MetS

(Table 1):42.3% ofwomen and 22.5% ofmen.Overall,BMI

averaged 27.7 ± 5.72 kg/m2, in the nearly obese range. However,

35.8% of subjects (38.0% of women and 33.8% of men) had BMI

of ≥28.8 kg/m2, taken to indicate obesity (15, 16).

Other factors possibly associated with MetS included: female

sex,older age,SzAff vs.Sz diagnosis,higher BPRS psychosis

score (which was associated with greater APD doses:Spearman

rs = 0.252,slope = 1.68 [0.653–2.72],p = 0.002),treatment

with antipsychoticswith relatively high risk ofobesity and

MetS (clozapine,olanzapine,paliperidone,quetiapine;Table 2),

higher CPZ-eq antipsychotic dose,but not orally administered

vs. LAI antipsychotics(Table 1).Additionalmetabolicand

cardiovascular measures did not differ between subjects with vs.

without MetS,including assays of TSH and thyroid hormones,

prolactin, pulse rate, and ECG repolarization interval (QTc), nor

did BPRS or PANSS ratings of psychosis-severity differ (Table 1).

As expected,measures that contributed to its diagnosis were

highly deviantamong subjectswith MetS,including obesity,

waist circumference, blood pressure, FBS, hemoglobin glycation,

serum concentrations of cholesterol (higher total and LDL, lower

HDL) and triglycerides (Table 1).BMI was not used to define

MetS but was markedly elevated in subjects with MetS (Table 1).

We also tested the strengths ofassociation ofsuch measures

with the diagnosis ofMetS using logistic regression modeling

(Table 2).These ranked as:higher FBS ≥ lower HDL ≥ higher

diastolic blood pressure ≥ higher BMI ≥ female sex (BMI and

sex were not included in diagnostic criteria for MetS).

Treatments and Metabolic Syndrome

LAI antipsychoticsweremore prescribed than oralagents

(57.7% vs.42.3%),particularly among Szvs. SzAff subjects

(65.5% vs.34.5%;χ2 = 3.67, p = 0.055), whereasoral

agents were used in halfof both diagnostic groups.Average

CPZ-eq daily dosesof oral and LAI antipsychoticsamong

Sz (295 mg)and SzAff subjects(338 mg)did not differ

significantly. LAI paliperidone palmitate was the most prescrib

antipsychoticagentin both diagnosticgroups(Sz 34.8%;

SzAff 27.4%;31.8% overall);otherLAI antipsychoticusage

ranked:risperidone extended release (10.6%)> aripiprazole

long acting (9.28%) > olanzapine palmitate (4.64%).Usage of

oral antipsychotics ranked:risperidone (Sz 11.2%,SzAff 12.9%,

11.9% overall)> haloperidol(7.28% overall)= olanzapine

(7.28%)> aripiprazole(5.30%)> quetiapine(3.98%)≥

paliperidone (3.31%) = clozapine (3.31%) > ziprasidone 1.32

Severalmetabolic measures were somewhat more favorable

with use of LAI vs. oral antipsychotics, including total choleste

(192 vs.223 mg/dL),LDL cholesterol(125 vs.175 mg/dL),

triglycerides (148 vs.188 mg/dL);waist circumference (103 cm

[40.6 in] vs.117 cm [46.1 in]);the cardiac QTc repolarization

interval (399 vs. 413 msec); and circulating prolactin (42.7 vs

ng/dL).

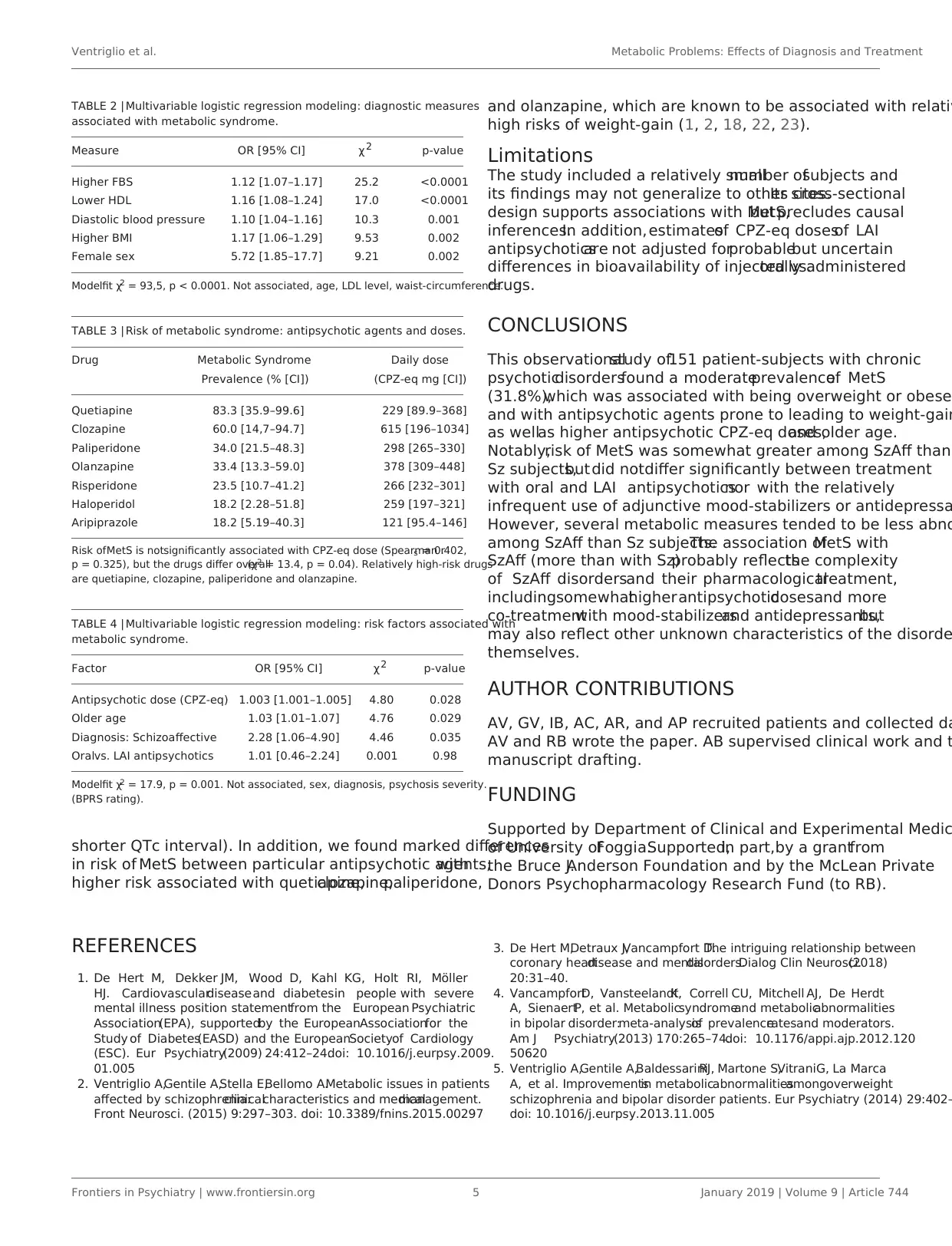

We compared the prevalence of MetS among subjects trea

with differentantipsychotic agents.Relatively high-risk drugs

were quetiapine (83.3%), clozapine (60.0%), paliperidone (34

and olanzapine (33.4%;Table 3).Of note,these risks were not

accounted for by dose as prevalence of MetS and CPZ-eq dos

were not significantly correlated (Table 3).

Multivariable Modeling: Factors

Associated With Metabolic Syndrome

We used multivariable logistic regression modeling to identify

factorsassociatedindependentlywith MetS. In order of

significance,associated factorsranked:CPZ-eq antipsychotic

dose,older age,and SzAff > Sz diagnosis,but not oralvs.LAI

antipsychotics (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study involved 151 patient-subjects with chronic psychot

disorders who had been clinically stable on constant medicati

regimens for at least 6 months. LAI antipsychotics were given

57.7%,and oralagents to 42.3%.LAI agents were more often

given to Sz subjects,whereasuse oforal antipsychoticswas

similarly prevalent in both SzAff and Sz subjects.SzAff subjects

were also 6–7-times more likely to be given co-treatment with

a mood-stabilizer or antidepressant.All subjects were rated at

moderate symptomatic severity by PANSS and BPRS. Adheren

to prescribed treatments was rated as good by DAI-30 score,

the risk of adverse effects was moderate at 19.8%.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 3 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

diagnosed with Sz (χ2 = 6.76; p = 0.009). Treatments included

oralantipsychotics in 42.3%,and LAI antipsychotics in 57.7%

(none received both). Antipsychotics were combined with mood-

stabilizers (MSs) in only 14.5%,or with antidepressants (ADs)

in 12.3% (ranking by use: duloxetine > paroxetine > citalopram

or S-citalopram > sertraline).Both adjunctive treatments were

given selectively with oralantipsychotics,by 6.4- (MSs) or 7.0-

times more (ADs; both p ≤ 0.006) among SzAff than Sz subjects.

Antipsychotic doses averaged 313 ± 329 mg/day CPZ-eq,and

MS (carbamazepine,lithium carbonate,sodium valproate) total

daily Li-eq doses averaged 650 ± 244 mg. Overall, clinical ratings

averaged 75.0 ± 34.7 for PANSS and 51.6 ± 23.6 for BPRS; both

indicate moderate symptomatic severity, even though all patients

reported clinical and treatment stability for at least six continuous

preceding months. Prolonged, stable dosing assured that even the

LAI antipsychotics were at pharmacokinetic steady-state.

Subjectswho receivedLAI vs. oral antipsychoticshad

significantly lowerlevelsof symptomaticmorbidity.PANSS

scores were, respectively, 58.0 ± 27.6 vs. 98.1 ± 29.9, and BPRS

scores averaged 40.1 ± 15.0 vs. 67.1 ± 24.5 (z-scores = 7.76 and

6.85, both p < 0.0001).

No subject was considered to have a substance-use disorder,

as was supportedby urine drug assays,consistentwith

current substance abuse as an exclusion criterion. Adherence to

prescribed treatments was considered good,as supported by a

DAI-30 score of 9.64 ± 2.19 (of a total maximum of 30).There

was a moderate rate of reported,treatment-associated,adverse

events (19.8%),most of which involved motor slowing or mild

tremor.

Risk and Measures Associated With

Metabolic Syndrome

Of the entire sample,31.8% metdiagnostic criteria for MetS

(Table 1):42.3% ofwomen and 22.5% ofmen.Overall,BMI

averaged 27.7 ± 5.72 kg/m2, in the nearly obese range. However,

35.8% of subjects (38.0% of women and 33.8% of men) had BMI

of ≥28.8 kg/m2, taken to indicate obesity (15, 16).

Other factors possibly associated with MetS included: female

sex,older age,SzAff vs.Sz diagnosis,higher BPRS psychosis

score (which was associated with greater APD doses:Spearman

rs = 0.252,slope = 1.68 [0.653–2.72],p = 0.002),treatment

with antipsychoticswith relatively high risk ofobesity and

MetS (clozapine,olanzapine,paliperidone,quetiapine;Table 2),

higher CPZ-eq antipsychotic dose,but not orally administered

vs. LAI antipsychotics(Table 1).Additionalmetabolicand

cardiovascular measures did not differ between subjects with vs.

without MetS,including assays of TSH and thyroid hormones,

prolactin, pulse rate, and ECG repolarization interval (QTc), nor

did BPRS or PANSS ratings of psychosis-severity differ (Table 1).

As expected,measures that contributed to its diagnosis were

highly deviantamong subjectswith MetS,including obesity,

waist circumference, blood pressure, FBS, hemoglobin glycation,

serum concentrations of cholesterol (higher total and LDL, lower

HDL) and triglycerides (Table 1).BMI was not used to define

MetS but was markedly elevated in subjects with MetS (Table 1).

We also tested the strengths ofassociation ofsuch measures

with the diagnosis ofMetS using logistic regression modeling

(Table 2).These ranked as:higher FBS ≥ lower HDL ≥ higher

diastolic blood pressure ≥ higher BMI ≥ female sex (BMI and

sex were not included in diagnostic criteria for MetS).

Treatments and Metabolic Syndrome

LAI antipsychoticsweremore prescribed than oralagents

(57.7% vs.42.3%),particularly among Szvs. SzAff subjects

(65.5% vs.34.5%;χ2 = 3.67, p = 0.055), whereasoral

agents were used in halfof both diagnostic groups.Average

CPZ-eq daily dosesof oral and LAI antipsychoticsamong

Sz (295 mg)and SzAff subjects(338 mg)did not differ

significantly. LAI paliperidone palmitate was the most prescrib

antipsychoticagentin both diagnosticgroups(Sz 34.8%;

SzAff 27.4%;31.8% overall);otherLAI antipsychoticusage

ranked:risperidone extended release (10.6%)> aripiprazole

long acting (9.28%) > olanzapine palmitate (4.64%).Usage of

oral antipsychotics ranked:risperidone (Sz 11.2%,SzAff 12.9%,

11.9% overall)> haloperidol(7.28% overall)= olanzapine

(7.28%)> aripiprazole(5.30%)> quetiapine(3.98%)≥

paliperidone (3.31%) = clozapine (3.31%) > ziprasidone 1.32

Severalmetabolic measures were somewhat more favorable

with use of LAI vs. oral antipsychotics, including total choleste

(192 vs.223 mg/dL),LDL cholesterol(125 vs.175 mg/dL),

triglycerides (148 vs.188 mg/dL);waist circumference (103 cm

[40.6 in] vs.117 cm [46.1 in]);the cardiac QTc repolarization

interval (399 vs. 413 msec); and circulating prolactin (42.7 vs

ng/dL).

We compared the prevalence of MetS among subjects trea

with differentantipsychotic agents.Relatively high-risk drugs

were quetiapine (83.3%), clozapine (60.0%), paliperidone (34

and olanzapine (33.4%;Table 3).Of note,these risks were not

accounted for by dose as prevalence of MetS and CPZ-eq dos

were not significantly correlated (Table 3).

Multivariable Modeling: Factors

Associated With Metabolic Syndrome

We used multivariable logistic regression modeling to identify

factorsassociatedindependentlywith MetS. In order of

significance,associated factorsranked:CPZ-eq antipsychotic

dose,older age,and SzAff > Sz diagnosis,but not oralvs.LAI

antipsychotics (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study involved 151 patient-subjects with chronic psychot

disorders who had been clinically stable on constant medicati

regimens for at least 6 months. LAI antipsychotics were given

57.7%,and oralagents to 42.3%.LAI agents were more often

given to Sz subjects,whereasuse oforal antipsychoticswas

similarly prevalent in both SzAff and Sz subjects.SzAff subjects

were also 6–7-times more likely to be given co-treatment with

a mood-stabilizer or antidepressant.All subjects were rated at

moderate symptomatic severity by PANSS and BPRS. Adheren

to prescribed treatments was rated as good by DAI-30 score,

the risk of adverse effects was moderate at 19.8%.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 3 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Ventriglio et al. Metabolic Problems: Effects of Diagnosis and Treatment

TABLE 1 | Factors associated with metabolic syndrome in 151 psychotic disorder patients.

Factor Metabolic syndrome Statistic p-value

Present Absent (z or χ2)a

Allcases (N = 151) 31.8 [24.5–39.9] 68.2 [60.1–75.5] – –

Women (%) 62.5 [47.4–76.0] 39.8 [30.3–49.9] 6.77 0.009

Older age (years) 45.0 [42.0–48.0] 40.8 [38.2–43.4] 2.18 0.03

Unemployed (%) 83.3 [69.8–92.5] 80.6 [71.6–87.7] 0.67 0.69

Schizoaffective diagnosis (%) 52.1 [37.2–66.7] 35.9 [26.7–46.0] 3.53 0.06

Psychosis

BPRS score 57.1 [49.8–64.4] 49.0 [44.6–53.4] 1.96 0.05

PANSS score 81.7 [71.1–92.3] 71.9 [65.3–78.5] 1.55 0.12

Substance abuse (%) 4.17 [0.51–14.3] 1.94 [0.24–6.84] 0.63 0.43

High-risk antipsychotics (%)b 29.2 [17.0–44.1] 14.6 [3.39–22.9] 4.50 0.03

LAI antipsychotics (%) 50.0 [35.2–64.8] 50.0 [35.2–64.8] 1.67 0.20

Antipsychotic dose (CPZ-eq, mg/day) 423 [266–580] 261 [235–287] 2.14 0.004

Treatment adherence (DA130) 9.95 [9.25–10.7] 9.59 [9.12–10.1] 0.86 0.39

Adverse drug effects (%) 22.9 [12.0–37.3] 18.4 [11.5–27.3] 0.41 0.52

Mood-stabilizers given (%) 18.8 [8.95–32.6] 12.6 [6.89–20.6] 0.99 0.32

Antidepressants given (%) 2.08 [0.05–11.1] 6.80 [2.28–13.5] 1.45 0.23

BMI (kg/m2) 30.3 [28.3–32.3] 26.6 [25.7–27.5] 3.43 0.0006

Obesity (% BMI≥28.8) 64.6 [49.5–77.8] 22.3 [14.7–31.6] 25.4 < 0.0001

Waist circumference (cm) 117 [110–124] 105 [100–110] 2.74 0.006

Systolic BP (mm Hg) 120 [117–123] 116 [114–117] 2.28 0.02

Diastolic BP (mm Hg) 76.5 [75.5–81.5] 73.7 [71.7–75.8] 2.58 0.01

Pulse rate (per min) 85.0 [82.7–86.1] 84.4 [82.4–87.6] 0.37 0.71

ECG repolarization (QTc, msec) 409 [401–417] 407 [403–411] 0.13 0.90

Glucose (FBS, mg/dL) 105 [99.6–110] 88.8 [87.2–90.4] 4.91 < 0.0001

HgbA1c (%) 5.95 [5.71–6.19] 5.62 [5.49–5.75] 2.79 0.005

Totalcholesterol(mg/dL) 217 [206–228] 200 [193–207] 2.50 0.01

LDL cholesterol(mg/dL) 161 [148–174] 140 [132–148] 2.75 0.006

HDL cholesterol(mg/dL) 42.9 [40.3–45.5] 50.2 [47.9–52.5] 3.86 0.0001

Triglycerides (mg/dL) 204 [181–227] 147 [135–159] 4.31 0.0002

TSH (nU/L) 2.56 [2.07–3.05] 2.14 [1.89–2.39] 1.65 0.10

Free thyroxin (ng/dL) 1.13 [1.07–3.05] 1.30 [1.09–1.51] 1.09 0.27

Free triiodothyronine (ng/dL) 0.358 [0.340–0.376] 0.353 [0.340–0.366] 0.86 0.39

Prolactin (ng/dL) 42.9 [41.4–54.5] 50.2 [47.1–65.9] 1.53 0.12

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; CPZ, chlorpromazine; DAI, Drug Attitude Inv

BMI, body-mass index; BP, blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; Hgb, hemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TSH, thyroid-stimulating

aMann-Whitney (z-score) or contingency table (χ2). bClozapine, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine.

The overallprevalence ofMetS (31.8%) was moderate,but

ranged from 18.2% with aripiprazole to 83.3% with quetiapine

(Table 3).By comparison,reported prevalenceof MetS in

patients with psychotic disorders has ranged from 30 to 67% (1, 7,

20, 21). Based on multivariate modeling, factors associated with

MetS were antipsychotic dose, older age, and SzAff diagnosis, but

not oral vs. LAI antipsychotics.

Of note,the presentfinding of significantly greaterrisk

of MetS with SzAff vs,Sz diagnoses supports one hypothesis

of this study,and addsto a previoussuggestion ofsuch a

relationship (6).Although use of complex medication regimens

wasmuch more prevalentamong SzAff subjects,these were

infrequentand notsignificantly associated with risk ofMetS.

In addition,CPZ-eq antipsychotic doses were somewhat higher

among SzAff subjects, although both factors appeared to ope

somewhat independently (Table 4). Nevertheless, we sugges

the relative instability of SzAff disorders contributes to the us

more complex treatments (7) and this feature as well perhap

intrinsic characteristics of such patients may contribute to ris

MetS.

In addition, contraryto prediction,we did not find a

significant difference in risk of MetS in association with treatm

with oral vs. LAI antipsychotics.This finding appearsto

be consistentwith otherrecentreportsindicating thatLAI

agentsmay not be saferthan oral antipsychotics(8, 10).

However,severalmeasurestended to be lessabnormalwith

LAI treatments(including lowertotaland LDL cholesterol,

triglyceridesand prolactin,smallerwaist-circumference,and

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 4 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

TABLE 1 | Factors associated with metabolic syndrome in 151 psychotic disorder patients.

Factor Metabolic syndrome Statistic p-value

Present Absent (z or χ2)a

Allcases (N = 151) 31.8 [24.5–39.9] 68.2 [60.1–75.5] – –

Women (%) 62.5 [47.4–76.0] 39.8 [30.3–49.9] 6.77 0.009

Older age (years) 45.0 [42.0–48.0] 40.8 [38.2–43.4] 2.18 0.03

Unemployed (%) 83.3 [69.8–92.5] 80.6 [71.6–87.7] 0.67 0.69

Schizoaffective diagnosis (%) 52.1 [37.2–66.7] 35.9 [26.7–46.0] 3.53 0.06

Psychosis

BPRS score 57.1 [49.8–64.4] 49.0 [44.6–53.4] 1.96 0.05

PANSS score 81.7 [71.1–92.3] 71.9 [65.3–78.5] 1.55 0.12

Substance abuse (%) 4.17 [0.51–14.3] 1.94 [0.24–6.84] 0.63 0.43

High-risk antipsychotics (%)b 29.2 [17.0–44.1] 14.6 [3.39–22.9] 4.50 0.03

LAI antipsychotics (%) 50.0 [35.2–64.8] 50.0 [35.2–64.8] 1.67 0.20

Antipsychotic dose (CPZ-eq, mg/day) 423 [266–580] 261 [235–287] 2.14 0.004

Treatment adherence (DA130) 9.95 [9.25–10.7] 9.59 [9.12–10.1] 0.86 0.39

Adverse drug effects (%) 22.9 [12.0–37.3] 18.4 [11.5–27.3] 0.41 0.52

Mood-stabilizers given (%) 18.8 [8.95–32.6] 12.6 [6.89–20.6] 0.99 0.32

Antidepressants given (%) 2.08 [0.05–11.1] 6.80 [2.28–13.5] 1.45 0.23

BMI (kg/m2) 30.3 [28.3–32.3] 26.6 [25.7–27.5] 3.43 0.0006

Obesity (% BMI≥28.8) 64.6 [49.5–77.8] 22.3 [14.7–31.6] 25.4 < 0.0001

Waist circumference (cm) 117 [110–124] 105 [100–110] 2.74 0.006

Systolic BP (mm Hg) 120 [117–123] 116 [114–117] 2.28 0.02

Diastolic BP (mm Hg) 76.5 [75.5–81.5] 73.7 [71.7–75.8] 2.58 0.01

Pulse rate (per min) 85.0 [82.7–86.1] 84.4 [82.4–87.6] 0.37 0.71

ECG repolarization (QTc, msec) 409 [401–417] 407 [403–411] 0.13 0.90

Glucose (FBS, mg/dL) 105 [99.6–110] 88.8 [87.2–90.4] 4.91 < 0.0001

HgbA1c (%) 5.95 [5.71–6.19] 5.62 [5.49–5.75] 2.79 0.005

Totalcholesterol(mg/dL) 217 [206–228] 200 [193–207] 2.50 0.01

LDL cholesterol(mg/dL) 161 [148–174] 140 [132–148] 2.75 0.006

HDL cholesterol(mg/dL) 42.9 [40.3–45.5] 50.2 [47.9–52.5] 3.86 0.0001

Triglycerides (mg/dL) 204 [181–227] 147 [135–159] 4.31 0.0002

TSH (nU/L) 2.56 [2.07–3.05] 2.14 [1.89–2.39] 1.65 0.10

Free thyroxin (ng/dL) 1.13 [1.07–3.05] 1.30 [1.09–1.51] 1.09 0.27

Free triiodothyronine (ng/dL) 0.358 [0.340–0.376] 0.353 [0.340–0.366] 0.86 0.39

Prolactin (ng/dL) 42.9 [41.4–54.5] 50.2 [47.1–65.9] 1.53 0.12

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; CPZ, chlorpromazine; DAI, Drug Attitude Inv

BMI, body-mass index; BP, blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; Hgb, hemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TSH, thyroid-stimulating

aMann-Whitney (z-score) or contingency table (χ2). bClozapine, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine.

The overallprevalence ofMetS (31.8%) was moderate,but

ranged from 18.2% with aripiprazole to 83.3% with quetiapine

(Table 3).By comparison,reported prevalenceof MetS in

patients with psychotic disorders has ranged from 30 to 67% (1, 7,

20, 21). Based on multivariate modeling, factors associated with

MetS were antipsychotic dose, older age, and SzAff diagnosis, but

not oral vs. LAI antipsychotics.

Of note,the presentfinding of significantly greaterrisk

of MetS with SzAff vs,Sz diagnoses supports one hypothesis

of this study,and addsto a previoussuggestion ofsuch a

relationship (6).Although use of complex medication regimens

wasmuch more prevalentamong SzAff subjects,these were

infrequentand notsignificantly associated with risk ofMetS.

In addition,CPZ-eq antipsychotic doses were somewhat higher

among SzAff subjects, although both factors appeared to ope

somewhat independently (Table 4). Nevertheless, we sugges

the relative instability of SzAff disorders contributes to the us

more complex treatments (7) and this feature as well perhap

intrinsic characteristics of such patients may contribute to ris

MetS.

In addition, contraryto prediction,we did not find a

significant difference in risk of MetS in association with treatm

with oral vs. LAI antipsychotics.This finding appearsto

be consistentwith otherrecentreportsindicating thatLAI

agentsmay not be saferthan oral antipsychotics(8, 10).

However,severalmeasurestended to be lessabnormalwith

LAI treatments(including lowertotaland LDL cholesterol,

triglyceridesand prolactin,smallerwaist-circumference,and

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 4 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Ventriglio et al. Metabolic Problems: Effects of Diagnosis and Treatment

TABLE 2 | Multivariable logistic regression modeling: diagnostic measures

associated with metabolic syndrome.

Measure OR [95% CI] χ2 p-value

Higher FBS 1.12 [1.07–1.17] 25.2 <0.0001

Lower HDL 1.16 [1.08–1.24] 17.0 <0.0001

Diastolic blood pressure 1.10 [1.04–1.16] 10.3 0.001

Higher BMI 1.17 [1.06–1.29] 9.53 0.002

Female sex 5.72 [1.85–17.7] 9.21 0.002

Modelfit χ2 = 93,5, p < 0.0001. Not associated, age, LDL level, waist-circumference.

TABLE 3 | Risk of metabolic syndrome: antipsychotic agents and doses.

Drug Metabolic Syndrome Daily dose

Prevalence (% [CI]) (CPZ-eq mg [CI])

Quetiapine 83.3 [35.9–99.6] 229 [89.9–368]

Clozapine 60.0 [14,7–94.7] 615 [196–1034]

Paliperidone 34.0 [21.5–48.3] 298 [265–330]

Olanzapine 33.4 [13.3–59.0] 378 [309–448]

Risperidone 23.5 [10.7–41.2] 266 [232–301]

Haloperidol 18.2 [2.28–51.8] 259 [197–321]

Aripiprazole 18.2 [5.19–40.3] 121 [95.4–146]

Risk ofMetS is notsignificantly associated with CPZ-eq dose (Spearman rs = 0.402,

p = 0.325), but the drugs differ overall(χ2 = 13.4, p = 0.04). Relatively high-risk drugs

are quetiapine, clozapine, paliperidone and olanzapine.

TABLE 4 | Multivariable logistic regression modeling: risk factors associated with

metabolic syndrome.

Factor OR [95% CI] χ2 p-value

Antipsychotic dose (CPZ-eq) 1.003 [1.001–1.005] 4.80 0.028

Older age 1.03 [1.01–1.07] 4.76 0.029

Diagnosis: Schizoaffective 2.28 [1.06–4.90] 4.46 0.035

Oralvs. LAI antipsychotics 1.01 [0.46–2.24] 0.001 0.98

Modelfit χ2 = 17.9, p = 0.001. Not associated, sex, diagnosis, psychosis severity.

(BPRS rating).

shorter QTc interval). In addition, we found marked differences

in risk of MetS between particular antipsychotic agents,with

higher risk associated with quetiapine,clozapine,paliperidone,

and olanzapine, which are known to be associated with relativ

high risks of weight-gain (1, 2, 18, 22, 23).

Limitations

The study included a relatively smallnumber ofsubjects and

its findings may not generalize to other sites.Its cross-sectional

design supports associations with MetS,but precludes causal

inferences.In addition,estimatesof CPZ-eq dosesof LAI

antipsychoticsare not adjusted forprobablebut uncertain

differences in bioavailability of injected vs.orally administered

drugs.

CONCLUSIONS

This observationalstudy of151 patient-subjects with chronic

psychoticdisordersfound a moderateprevalenceof MetS

(31.8%),which was associated with being overweight or obese

and with antipsychotic agents prone to leading to weight-gain

as wellas higher antipsychotic CPZ-eq doses,and older age.

Notably,risk of MetS was somewhat greater among SzAff than

Sz subjects,butdid notdiffer significantly between treatment

with oral and LAI antipsychoticsnor with the relatively

infrequent use of adjunctive mood-stabilizers or antidepressa

However, several metabolic measures tended to be less abno

among SzAff than Sz subjects.The association ofMetS with

SzAff (more than with Sz)probably reflectsthe complexity

of SzAff disordersand their pharmacologicaltreatment,

includingsomewhathigherantipsychoticdosesand more

co-treatmentwith mood-stabilizersand antidepressants,but

may also reflect other unknown characteristics of the disorde

themselves.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AV, GV, IB, AC, AR, and AP recruited patients and collected da

AV and RB wrote the paper. AB supervised clinical work and t

manuscript drafting.

FUNDING

Supported by Department of Clinical and Experimental Medic

of University ofFoggia.Supported,in part,by a grantfrom

the Bruce J.Anderson Foundation and by the McLean Private

Donors Psychopharmacology Research Fund (to RB).

REFERENCES

1. De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Möller

HJ. Cardiovasculardiseaseand diabetesin people with severe

mental illness position statementfrom the European Psychiatric

Association(EPA), supportedby the EuropeanAssociationfor the

Study of Diabetes(EASD) and the EuropeanSocietyof Cardiology

(ESC). Eur Psychiatry(2009) 24:412–24.doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.

01.005

2. Ventriglio A,Gentile A,Stella E,Bellomo A.Metabolic issues in patients

affected by schizophrenia:clinicalcharacteristics and medicalmanagement.

Front Neurosci. (2015) 9:297–303. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00297

3. De Hert M,Detraux J,Vancampfort D.The intriguing relationship between

coronary heartdisease and mentaldisorders.Dialog Clin Neurosci.(2018)

20:31–40.

4. VancampfortD, VansteelandtK, Correll CU, Mitchell AJ, De Herdt

A, SienaertP, et al. Metabolicsyndromeand metabolicabnormalities

in bipolar disorder:meta-analysisof prevalenceratesand moderators.

Am J Psychiatry(2013) 170:265–74.doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.120

50620

5. Ventriglio A,Gentile A,BaldessariniRJ, Martone S,VitraniG, La Marca

A, et al. Improvementsin metabolicabnormalitiesamongoverweight

schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients. Eur Psychiatry (2014) 29:402–

doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.11.005

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 5 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

TABLE 2 | Multivariable logistic regression modeling: diagnostic measures

associated with metabolic syndrome.

Measure OR [95% CI] χ2 p-value

Higher FBS 1.12 [1.07–1.17] 25.2 <0.0001

Lower HDL 1.16 [1.08–1.24] 17.0 <0.0001

Diastolic blood pressure 1.10 [1.04–1.16] 10.3 0.001

Higher BMI 1.17 [1.06–1.29] 9.53 0.002

Female sex 5.72 [1.85–17.7] 9.21 0.002

Modelfit χ2 = 93,5, p < 0.0001. Not associated, age, LDL level, waist-circumference.

TABLE 3 | Risk of metabolic syndrome: antipsychotic agents and doses.

Drug Metabolic Syndrome Daily dose

Prevalence (% [CI]) (CPZ-eq mg [CI])

Quetiapine 83.3 [35.9–99.6] 229 [89.9–368]

Clozapine 60.0 [14,7–94.7] 615 [196–1034]

Paliperidone 34.0 [21.5–48.3] 298 [265–330]

Olanzapine 33.4 [13.3–59.0] 378 [309–448]

Risperidone 23.5 [10.7–41.2] 266 [232–301]

Haloperidol 18.2 [2.28–51.8] 259 [197–321]

Aripiprazole 18.2 [5.19–40.3] 121 [95.4–146]

Risk ofMetS is notsignificantly associated with CPZ-eq dose (Spearman rs = 0.402,

p = 0.325), but the drugs differ overall(χ2 = 13.4, p = 0.04). Relatively high-risk drugs

are quetiapine, clozapine, paliperidone and olanzapine.

TABLE 4 | Multivariable logistic regression modeling: risk factors associated with

metabolic syndrome.

Factor OR [95% CI] χ2 p-value

Antipsychotic dose (CPZ-eq) 1.003 [1.001–1.005] 4.80 0.028

Older age 1.03 [1.01–1.07] 4.76 0.029

Diagnosis: Schizoaffective 2.28 [1.06–4.90] 4.46 0.035

Oralvs. LAI antipsychotics 1.01 [0.46–2.24] 0.001 0.98

Modelfit χ2 = 17.9, p = 0.001. Not associated, sex, diagnosis, psychosis severity.

(BPRS rating).

shorter QTc interval). In addition, we found marked differences

in risk of MetS between particular antipsychotic agents,with

higher risk associated with quetiapine,clozapine,paliperidone,

and olanzapine, which are known to be associated with relativ

high risks of weight-gain (1, 2, 18, 22, 23).

Limitations

The study included a relatively smallnumber ofsubjects and

its findings may not generalize to other sites.Its cross-sectional

design supports associations with MetS,but precludes causal

inferences.In addition,estimatesof CPZ-eq dosesof LAI

antipsychoticsare not adjusted forprobablebut uncertain

differences in bioavailability of injected vs.orally administered

drugs.

CONCLUSIONS

This observationalstudy of151 patient-subjects with chronic

psychoticdisordersfound a moderateprevalenceof MetS

(31.8%),which was associated with being overweight or obese

and with antipsychotic agents prone to leading to weight-gain

as wellas higher antipsychotic CPZ-eq doses,and older age.

Notably,risk of MetS was somewhat greater among SzAff than

Sz subjects,butdid notdiffer significantly between treatment

with oral and LAI antipsychoticsnor with the relatively

infrequent use of adjunctive mood-stabilizers or antidepressa

However, several metabolic measures tended to be less abno

among SzAff than Sz subjects.The association ofMetS with

SzAff (more than with Sz)probably reflectsthe complexity

of SzAff disordersand their pharmacologicaltreatment,

includingsomewhathigherantipsychoticdosesand more

co-treatmentwith mood-stabilizersand antidepressants,but

may also reflect other unknown characteristics of the disorde

themselves.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AV, GV, IB, AC, AR, and AP recruited patients and collected da

AV and RB wrote the paper. AB supervised clinical work and t

manuscript drafting.

FUNDING

Supported by Department of Clinical and Experimental Medic

of University ofFoggia.Supported,in part,by a grantfrom

the Bruce J.Anderson Foundation and by the McLean Private

Donors Psychopharmacology Research Fund (to RB).

REFERENCES

1. De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Möller

HJ. Cardiovasculardiseaseand diabetesin people with severe

mental illness position statementfrom the European Psychiatric

Association(EPA), supportedby the EuropeanAssociationfor the

Study of Diabetes(EASD) and the EuropeanSocietyof Cardiology

(ESC). Eur Psychiatry(2009) 24:412–24.doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.

01.005

2. Ventriglio A,Gentile A,Stella E,Bellomo A.Metabolic issues in patients

affected by schizophrenia:clinicalcharacteristics and medicalmanagement.

Front Neurosci. (2015) 9:297–303. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00297

3. De Hert M,Detraux J,Vancampfort D.The intriguing relationship between

coronary heartdisease and mentaldisorders.Dialog Clin Neurosci.(2018)

20:31–40.

4. VancampfortD, VansteelandtK, Correll CU, Mitchell AJ, De Herdt

A, SienaertP, et al. Metabolicsyndromeand metabolicabnormalities

in bipolar disorder:meta-analysisof prevalenceratesand moderators.

Am J Psychiatry(2013) 170:265–74.doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.120

50620

5. Ventriglio A,Gentile A,BaldessariniRJ, Martone S,VitraniG, La Marca

A, et al. Improvementsin metabolicabnormalitiesamongoverweight

schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients. Eur Psychiatry (2014) 29:402–

doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.11.005

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 5 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

Ventriglio et al. Metabolic Problems: Effects of Diagnosis and Treatment

6. Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Caslini M, Clerici M, Carrà G. Schizoaffective disorder

and metabolicsyndrome:meta-analyticcomparison with schizophrenia

and othernonaffective psychoses.J PsychiatrRes.(2015)66–67:127–34.

doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.028

7. Chouinard VA, Pingali SM, Chouinard G, Henderson DC, Mallya SG, Cypess

AM, et al.Factors associated with overweight and obesity in schizophrenia,

schizoaffective and bipolardisorders.Psychiatry Res.(2016)237:304–10.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.024

8. Gentile S.Safety concerns associated with second-generation antipsychotic

long-acting injection treatment.A systematic update.Horm MolBiolClin

Investig. (2017). doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0004. [Epub ahead of print].

9. BrissosS, Ruiz VeguillaM, Taylor D, Balanzá-MartinezV. Role of

long-acting injectable antipsychoticsin schizophrenia:a criticalappraisal

Ther Adv Psychopharmacol.(2014)4:198–219.doi: 10.1177/20451253145

40297

10. Sanchez-Martinez V,Romero-Rubio D,Abad-Perez MJ,Descalzo-Cabades

MA, Alonso-GutierrezS, Salazar-FraileJ, et al. Metabolicsyndrome

and cardiovascularrisk in people treatedwith long-actinginjectable

antipsychotics. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets (2018) 18:379–87.

doi: 10.2174/1871530317666171120151201

11. American Psychiatric Association (APA).Diagnostic and StatisticalManual

of Mental Disorders.4th ed.Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).Washington,DC:

American Psychiatric Publishing (2000).

12. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positiveand negativesyndrome

scalefor schizophrenia(PANSS).Schizophrenia Bull.(1987)13:261–76.

doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

13. Overall JE,Gorham DR.The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).Psychol

Rep. (1962) 10:799–812. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799

14. Hogan TP, Awad AG, EastwoodR. Self-reportscale predictiveof

drug compliancein schizophrenics:reliability and discriminative

validity. PsycholMed. (1983) 13:177–83.doi: 10.1017/S00332917000

50182

15. Alberti KG, ZimmetP, Shaw J. Metabolicsyndrome-anew worldwide

definition: consensusstatementfrom the InternationalDiabetes

Federation.Diabet Med.(2006) 23:469–80.doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.0

1858.x

16. AlbertiKG, EckelRH, Grundy SM,Zimmet PZ,Cleeman JI,Donato KA,

et al.Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome.Circulation (2009) 120:1640–5.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

17. Gardner D,Murphy A,BaldessariniRJ. Equivalentdoses ofantipsychotic

agents: findings from an international Delphi survey. Am J Psychiatry (2010

167:686–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802

18. Baldessarini RJ. Chemotherapy in Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Spring

Press (2013).

19. Centorrino F,Sani G,Fogarty KV,Salvatore P,Talamo A,Cincotta SL,et al.

Combinations of mood-stabilizers with antipsychotics as treatment strateg

in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Clin Neuropsychiatry (2006) 3:322–26.

20. Centorrino F,Masters G,BaldessariniRJ, Öngür D.Metabolic syndrome

in psychiatricallyhospitalizedpatients treated with antipsychotics

and other psychotropics.Hum Psychopharmacol.(2012) 27:521–6.

doi: 10.1002/hup.2257

21. Correll CU, Frederickson AM,Kane JM, Manu P. Metabolic syndrome

and the risk of coronaryheartdiseasein 367 patientstreated with

second generation antipsychotic drugs.J Clin Psychiatry (2006) 67:575–83.

doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0408

22. Musil R, ObermeierM, Russ P, Hamerle M. Weight-gainand

antipsychotis;drug safety review.Expert Opin Drug Safety (2015) 14:73–96.

doi: 10.1517/14740338.2015.974549

23. Cascade E,KalaliAH, Buckley P.Treatmentof schizoaffective disorder.

Psychiatry (2009) 6:15–7.

Conflictof InterestStatement:The authorsdeclarethat the research was

conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that cou

be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2019 Ventriglio,Baldessarini,Vitrani,Bonfitto,Cecere,Rinaldi,

Petito and Bellomo.This is an open-accessarticle distributed under the terms

of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).The use,distribution or

reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and

copyrightowner(s) are credited and that the originalpublication in this journal

is cited,in accordance with accepted academic practice.No use,distribution or

reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 6 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

6. Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Caslini M, Clerici M, Carrà G. Schizoaffective disorder

and metabolicsyndrome:meta-analyticcomparison with schizophrenia

and othernonaffective psychoses.J PsychiatrRes.(2015)66–67:127–34.

doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.028

7. Chouinard VA, Pingali SM, Chouinard G, Henderson DC, Mallya SG, Cypess

AM, et al.Factors associated with overweight and obesity in schizophrenia,

schizoaffective and bipolardisorders.Psychiatry Res.(2016)237:304–10.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.024

8. Gentile S.Safety concerns associated with second-generation antipsychotic

long-acting injection treatment.A systematic update.Horm MolBiolClin

Investig. (2017). doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0004. [Epub ahead of print].

9. BrissosS, Ruiz VeguillaM, Taylor D, Balanzá-MartinezV. Role of

long-acting injectable antipsychoticsin schizophrenia:a criticalappraisal

Ther Adv Psychopharmacol.(2014)4:198–219.doi: 10.1177/20451253145

40297

10. Sanchez-Martinez V,Romero-Rubio D,Abad-Perez MJ,Descalzo-Cabades

MA, Alonso-GutierrezS, Salazar-FraileJ, et al. Metabolicsyndrome

and cardiovascularrisk in people treatedwith long-actinginjectable

antipsychotics. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets (2018) 18:379–87.

doi: 10.2174/1871530317666171120151201

11. American Psychiatric Association (APA).Diagnostic and StatisticalManual

of Mental Disorders.4th ed.Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).Washington,DC:

American Psychiatric Publishing (2000).

12. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positiveand negativesyndrome

scalefor schizophrenia(PANSS).Schizophrenia Bull.(1987)13:261–76.

doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

13. Overall JE,Gorham DR.The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).Psychol

Rep. (1962) 10:799–812. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799

14. Hogan TP, Awad AG, EastwoodR. Self-reportscale predictiveof

drug compliancein schizophrenics:reliability and discriminative

validity. PsycholMed. (1983) 13:177–83.doi: 10.1017/S00332917000

50182

15. Alberti KG, ZimmetP, Shaw J. Metabolicsyndrome-anew worldwide

definition: consensusstatementfrom the InternationalDiabetes

Federation.Diabet Med.(2006) 23:469–80.doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.0

1858.x

16. AlbertiKG, EckelRH, Grundy SM,Zimmet PZ,Cleeman JI,Donato KA,

et al.Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome.Circulation (2009) 120:1640–5.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

17. Gardner D,Murphy A,BaldessariniRJ. Equivalentdoses ofantipsychotic

agents: findings from an international Delphi survey. Am J Psychiatry (2010

167:686–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802

18. Baldessarini RJ. Chemotherapy in Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Spring

Press (2013).

19. Centorrino F,Sani G,Fogarty KV,Salvatore P,Talamo A,Cincotta SL,et al.

Combinations of mood-stabilizers with antipsychotics as treatment strateg

in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Clin Neuropsychiatry (2006) 3:322–26.

20. Centorrino F,Masters G,BaldessariniRJ, Öngür D.Metabolic syndrome

in psychiatricallyhospitalizedpatients treated with antipsychotics

and other psychotropics.Hum Psychopharmacol.(2012) 27:521–6.

doi: 10.1002/hup.2257

21. Correll CU, Frederickson AM,Kane JM, Manu P. Metabolic syndrome

and the risk of coronaryheartdiseasein 367 patientstreated with

second generation antipsychotic drugs.J Clin Psychiatry (2006) 67:575–83.

doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0408

22. Musil R, ObermeierM, Russ P, Hamerle M. Weight-gainand

antipsychotis;drug safety review.Expert Opin Drug Safety (2015) 14:73–96.

doi: 10.1517/14740338.2015.974549

23. Cascade E,KalaliAH, Buckley P.Treatmentof schizoaffective disorder.

Psychiatry (2009) 6:15–7.

Conflictof InterestStatement:The authorsdeclarethat the research was

conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that cou

be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2019 Ventriglio,Baldessarini,Vitrani,Bonfitto,Cecere,Rinaldi,

Petito and Bellomo.This is an open-accessarticle distributed under the terms

of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).The use,distribution or

reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and

copyrightowner(s) are credited and that the originalpublication in this journal

is cited,in accordance with accepted academic practice.No use,distribution or

reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org 6 January 2019 | Volume 9 | Article 744

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.