Case Study: Comparing Community Engagement in Two Mining Projects

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|13

|2769

|137

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study provides a comparative analysis of two mining projects: the Melak Coal Mine Project managed by CIMIC Group and the Paddington Gold Mine Project by Mackellar Mining. The analysis examines the project descriptions, including the location, scale, and operational details of each mine. A key focus is the nature of the relationship between the mining companies and their host communities, considering community engagement strategies, the role of community liaison officers, and the implementation of corporate social responsibility initiatives such as scholarships and infrastructure development. The study highlights the reporting mechanisms used by both companies, including the integration of community projects in regular reports and stakeholder meetings. The conclusion emphasizes the similarities in community engagement structures and approaches, despite differences in project specifics and geographical locations, offering insights into effective community relations practices within the mining industry. The study draws from academic literature, company reports, and industry analysis.

A comparative analysis of the operations of Mackellar Mining and CIMIC Group

Name

Institution

Name

Institution

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Introduction

CIMIC Group is one of the major international public, private partnership groups that

engage in the activities of mining and infrastructural construction. The company was formerly

known as Leighton Holdings before it changes its name in the year 2015. The company is

known for environmental service, mining, building and property, engineering and infrastructure

as well as telecommunication industries. It operates in some countries including Australia, South

East Asia, New Zealand, and the Middle East. The core values of the company are innovation,

delivery, accountability, and integrity1. One of the projects that the company is currently

handling is the Metro Tunnel RailWorks.

Mackellar Mining, like its counterpart CIMIC Group, also takes part in Mining services.

Other than that, the company also does stockpile management, workshop maintenance services

and haul road maintenance. The company has an operation record of over 40 years and has

carried out some projects that have helped the company build a reputation for high-quality

service delivery. The company was initially known as Jalgrid and Jalagrid WA Pty Ltd when it

was founded in the year 1972. The entity made use of the initial name until the year 2003 when

the company rebranded and adopted the current name2. One of the most recent projects that the

company had to work on is the Paddington Gold Mine project.

1 “CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis.” 2018. CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis, July,

1–7. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=131348345&site=ehost-

live.

2 Marsh, Jillian K. 2013. “Decolonising the Interface between Indigenous Peoples and Mining

Companies in Australia: Making Space for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54

(2): 171–84. doi:10.1111/apv.12017.

CIMIC Group is one of the major international public, private partnership groups that

engage in the activities of mining and infrastructural construction. The company was formerly

known as Leighton Holdings before it changes its name in the year 2015. The company is

known for environmental service, mining, building and property, engineering and infrastructure

as well as telecommunication industries. It operates in some countries including Australia, South

East Asia, New Zealand, and the Middle East. The core values of the company are innovation,

delivery, accountability, and integrity1. One of the projects that the company is currently

handling is the Metro Tunnel RailWorks.

Mackellar Mining, like its counterpart CIMIC Group, also takes part in Mining services.

Other than that, the company also does stockpile management, workshop maintenance services

and haul road maintenance. The company has an operation record of over 40 years and has

carried out some projects that have helped the company build a reputation for high-quality

service delivery. The company was initially known as Jalgrid and Jalagrid WA Pty Ltd when it

was founded in the year 1972. The entity made use of the initial name until the year 2003 when

the company rebranded and adopted the current name2. One of the most recent projects that the

company had to work on is the Paddington Gold Mine project.

1 “CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis.” 2018. CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis, July,

1–7. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=131348345&site=ehost-

live.

2 Marsh, Jillian K. 2013. “Decolonising the Interface between Indigenous Peoples and Mining

Companies in Australia: Making Space for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54

(2): 171–84. doi:10.1111/apv.12017.

This paper entails a comparative analysis of the Malak Coal Mine Project by the CIMIC Group

and the Paddington Gold Mine Project of the Mackellar Mining Company. The study takes into

consideration the community engagement by both companies.

The projects

The Paddington Gold Mine project is a long-term project under the management of

Mackellar Mining Company. The side of the project is located in the Western parts of Australia.

The project description involves the excavation of ore and waste mining as well. The total output

of the process is approximated at 2M BCM each month, and the project is projected to take seven

years. However, the transition of the seven-year term can only be initiated by the owner of the

miner. The project uses dry hire of more than thirty machines with maintenance. The Malak Coal

Mine Project has its site in Indonesia. The client in this project is the Bayan Resource group, and

the role of the company is to deliver targeted quantities to the client daily. At the initial stages of

the project, the target production was two million tons per year. The current mining target for the

company is at 2.2 million tons in a year3. The project is valued at $A180 million.

The host Communities

In carving out a project such as mining, it is essential to include the local community is

the process as they form a vital part of the stakeholders4. It is required of the companies to

develop a stakeholder engagement plan that includes the local communities to help with the

3 Chia, Kerryn, John Koch, Rohan Sadler, and Shane Turner. 2016. “Re-Establishing the Mid-

Storey Tree Persoonia Longifolia (Proteaceae) in Restored Forest Following Bauxite Mining in

Southern Western Australia.” Ecological Research 31 (5): 627–38. doi:10.1007/s11284-016-

1370-y.

4 Dawkins, Cedric. 2015. “Agonistic Pluralism and Stakeholder Engagement.” Business Ethics

Quarterly 25 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1017/beq.2015.2.

and the Paddington Gold Mine Project of the Mackellar Mining Company. The study takes into

consideration the community engagement by both companies.

The projects

The Paddington Gold Mine project is a long-term project under the management of

Mackellar Mining Company. The side of the project is located in the Western parts of Australia.

The project description involves the excavation of ore and waste mining as well. The total output

of the process is approximated at 2M BCM each month, and the project is projected to take seven

years. However, the transition of the seven-year term can only be initiated by the owner of the

miner. The project uses dry hire of more than thirty machines with maintenance. The Malak Coal

Mine Project has its site in Indonesia. The client in this project is the Bayan Resource group, and

the role of the company is to deliver targeted quantities to the client daily. At the initial stages of

the project, the target production was two million tons per year. The current mining target for the

company is at 2.2 million tons in a year3. The project is valued at $A180 million.

The host Communities

In carving out a project such as mining, it is essential to include the local community is

the process as they form a vital part of the stakeholders4. It is required of the companies to

develop a stakeholder engagement plan that includes the local communities to help with the

3 Chia, Kerryn, John Koch, Rohan Sadler, and Shane Turner. 2016. “Re-Establishing the Mid-

Storey Tree Persoonia Longifolia (Proteaceae) in Restored Forest Following Bauxite Mining in

Southern Western Australia.” Ecological Research 31 (5): 627–38. doi:10.1007/s11284-016-

1370-y.

4 Dawkins, Cedric. 2015. “Agonistic Pluralism and Stakeholder Engagement.” Business Ethics

Quarterly 25 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1017/beq.2015.2.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

development of a good rapport between the mining company and the local community5. It is

therefore vital to include a community liaison officer in the leadership structure of the project

management. The liaison officer should come from the community to help in the creation of a

connection between the local community and the company6. The inclusion of a member of the

local community in the project management helps in understanding the peoples’ culture and

believes as well as expectations from the company. In most instances, the interests of the local

community are always anchored on jobs and corporate social responsibility of the company.

Through the development of a stakeholder engagement plan, the company can strategically

manage some of the expectations of the community.

In the case of Melak Coal Mine Project, the local community in Eastern Kalimantan,

Indonesia has been friendly and supportive to the miners. The company has not reported any

incidences of hostility from the local community. The peaceful environment that the community

has provided the miners has enabled them to operate peacefully without the worry of hostile

reactions or actions from the community. The only security measure that the company has had to

take is the use of multi-media communication among the works which have proven to be not

only effective but also efficient in the course of the mining process. The peaceful coexistence

5 Provasnek, Anna Katharina1, anna.provasnek@gmail.com, Erwin1, erwin.schmid@boku.ac.at

Schmid, and Gerald2,3, gsteiner@wcfia.harvard.edu, gerald.steiner@donau-uni.ac.at Steiner.

2018. “Stakeholder Engagement: Keeping Business Legitimate in Austria’s Natural Mineral

Water Bottling Industry.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (2): 467–84. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-

3121-y.

6 Maciej, Nowak, Targiel S. Krzysztof, Błaszczyk Bożena, and Kania Sebastian. 2018.

“Stakeholders in Mining Projects.” Project Management Development - Practice & Perspectives,

January, 66–74. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=buh&AN=130498229&site=ehost-live.

therefore vital to include a community liaison officer in the leadership structure of the project

management. The liaison officer should come from the community to help in the creation of a

connection between the local community and the company6. The inclusion of a member of the

local community in the project management helps in understanding the peoples’ culture and

believes as well as expectations from the company. In most instances, the interests of the local

community are always anchored on jobs and corporate social responsibility of the company.

Through the development of a stakeholder engagement plan, the company can strategically

manage some of the expectations of the community.

In the case of Melak Coal Mine Project, the local community in Eastern Kalimantan,

Indonesia has been friendly and supportive to the miners. The company has not reported any

incidences of hostility from the local community. The peaceful environment that the community

has provided the miners has enabled them to operate peacefully without the worry of hostile

reactions or actions from the community. The only security measure that the company has had to

take is the use of multi-media communication among the works which have proven to be not

only effective but also efficient in the course of the mining process. The peaceful coexistence

5 Provasnek, Anna Katharina1, anna.provasnek@gmail.com, Erwin1, erwin.schmid@boku.ac.at

Schmid, and Gerald2,3, gsteiner@wcfia.harvard.edu, gerald.steiner@donau-uni.ac.at Steiner.

2018. “Stakeholder Engagement: Keeping Business Legitimate in Austria’s Natural Mineral

Water Bottling Industry.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (2): 467–84. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-

3121-y.

6 Maciej, Nowak, Targiel S. Krzysztof, Błaszczyk Bożena, and Kania Sebastian. 2018.

“Stakeholders in Mining Projects.” Project Management Development - Practice & Perspectives,

January, 66–74. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=buh&AN=130498229&site=ehost-live.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

between the project managers and the community is also experienced in the case of the

Paddington Gold Mine project. The company has also not recorded any scenarios of hostility

from the community which is an indication of amicable coexistence between the miner and the

community.

Community engagement approach

The two companies have incorporated the community into the project through the

employment of some of the community members as laborers while some as research assistants.

The community liaison officers in both companies are locals from the various communities in

which the companies operate. The two companies also involve the community in the stakeholder

engagement meetings to get the views of the communities on the projects and register any

rinsing complaints7. The companies have invested in corporate social responsibilities at varying

magnitudes8. For instance, the Paddington Gold Mine project offers scholarships to local

students to study subjects of their interest in universities and colleges9. On the other hand, Melak

Coal Mine Project has invested in the development of infrastructure around the mining site to

improve on accessibility to the local social facilities like hospitals and schools. Since the projects

7 Herremans, Irene1, irene.herremans@haskayne.ucalgary.ca, Jamal2, jnazari@sfu.ca Nazari,

and Fereshteh, fmahmoud@sfu.ca Mahmoudian. 2016. “Stakeholder Relationships, Engagement,

and Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics 138 (3): 417–35. doi:10.1007/s10551-

015-2634-0.

8 Campbell, John L. 2018. “2017 Decade Award Invited Article Reflections on the 2017 Decade

Award: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Financial Crisis.” Academy of Management

Review 43 (4): 546–56. doi:10.5465/amr.2018.0057.

9 CIMIC annual report. 2017. Retreved through

https://www.cimic.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/35843/4-Annual-Report-to-

shareholders.pdf

Paddington Gold Mine project. The company has also not recorded any scenarios of hostility

from the community which is an indication of amicable coexistence between the miner and the

community.

Community engagement approach

The two companies have incorporated the community into the project through the

employment of some of the community members as laborers while some as research assistants.

The community liaison officers in both companies are locals from the various communities in

which the companies operate. The two companies also involve the community in the stakeholder

engagement meetings to get the views of the communities on the projects and register any

rinsing complaints7. The companies have invested in corporate social responsibilities at varying

magnitudes8. For instance, the Paddington Gold Mine project offers scholarships to local

students to study subjects of their interest in universities and colleges9. On the other hand, Melak

Coal Mine Project has invested in the development of infrastructure around the mining site to

improve on accessibility to the local social facilities like hospitals and schools. Since the projects

7 Herremans, Irene1, irene.herremans@haskayne.ucalgary.ca, Jamal2, jnazari@sfu.ca Nazari,

and Fereshteh, fmahmoud@sfu.ca Mahmoudian. 2016. “Stakeholder Relationships, Engagement,

and Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics 138 (3): 417–35. doi:10.1007/s10551-

015-2634-0.

8 Campbell, John L. 2018. “2017 Decade Award Invited Article Reflections on the 2017 Decade

Award: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Financial Crisis.” Academy of Management

Review 43 (4): 546–56. doi:10.5465/amr.2018.0057.

9 CIMIC annual report. 2017. Retreved through

https://www.cimic.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/35843/4-Annual-Report-to-

shareholders.pdf

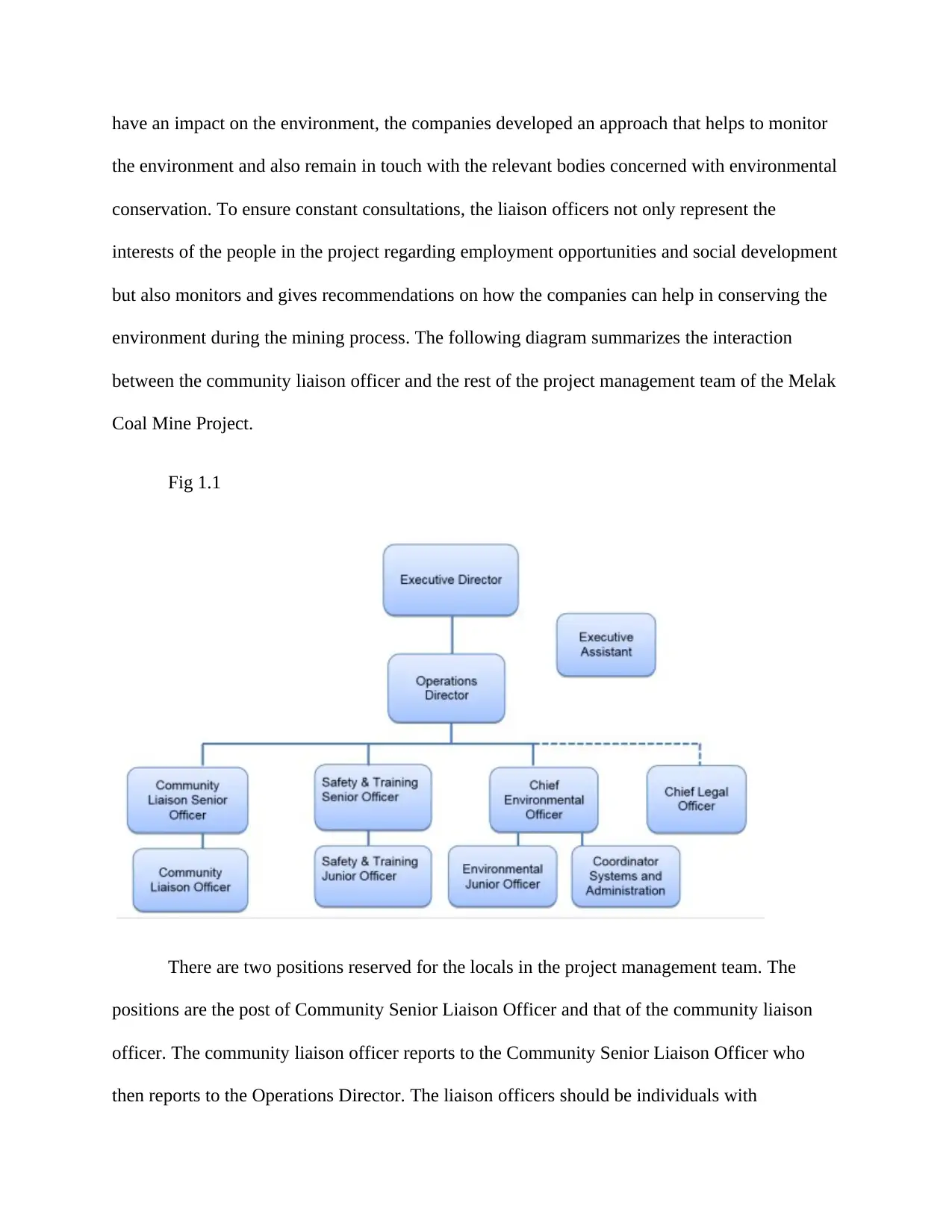

have an impact on the environment, the companies developed an approach that helps to monitor

the environment and also remain in touch with the relevant bodies concerned with environmental

conservation. To ensure constant consultations, the liaison officers not only represent the

interests of the people in the project regarding employment opportunities and social development

but also monitors and gives recommendations on how the companies can help in conserving the

environment during the mining process. The following diagram summarizes the interaction

between the community liaison officer and the rest of the project management team of the Melak

Coal Mine Project.

Fig 1.1

There are two positions reserved for the locals in the project management team. The

positions are the post of Community Senior Liaison Officer and that of the community liaison

officer. The community liaison officer reports to the Community Senior Liaison Officer who

then reports to the Operations Director. The liaison officers should be individuals with

the environment and also remain in touch with the relevant bodies concerned with environmental

conservation. To ensure constant consultations, the liaison officers not only represent the

interests of the people in the project regarding employment opportunities and social development

but also monitors and gives recommendations on how the companies can help in conserving the

environment during the mining process. The following diagram summarizes the interaction

between the community liaison officer and the rest of the project management team of the Melak

Coal Mine Project.

Fig 1.1

There are two positions reserved for the locals in the project management team. The

positions are the post of Community Senior Liaison Officer and that of the community liaison

officer. The community liaison officer reports to the Community Senior Liaison Officer who

then reports to the Operations Director. The liaison officers should be individuals with

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

knowledge about the cultures and norms of the people as well as conversant with the terrain of

the region10. The community liaison officers are charged with the responsibility of organizing

and conducting community engagement forums and passage of critical information between the

project management and the community. While the two companies make use of a similar

structure, there exists a slight difference inters of the senior management contact with the

community. Melak Coal Mine Project puts the liaison officers at the forefront when it comes to

community engagement while the senior management of the Paddington Gold Mine project

chooses to do the engagement side by side with the community liaison officers.

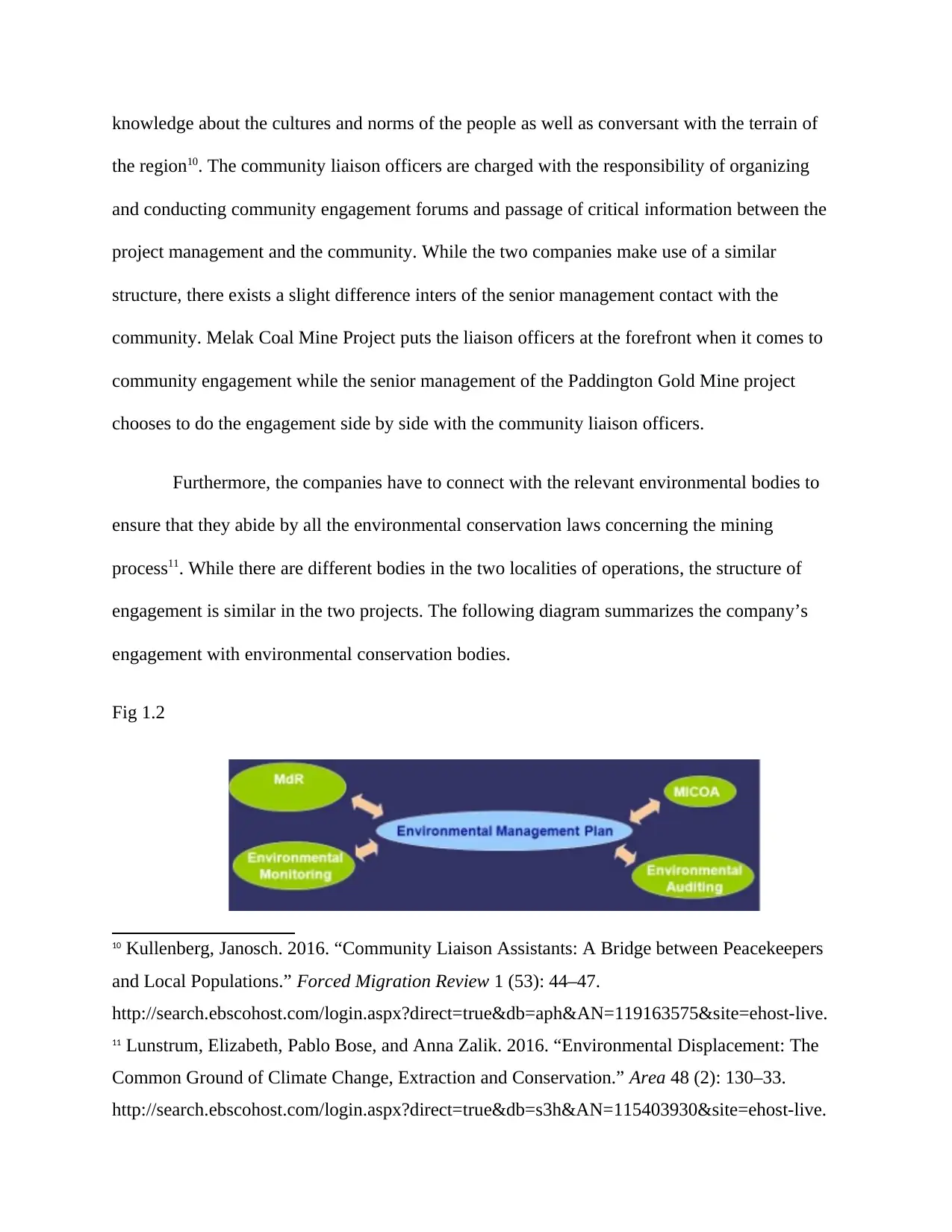

Furthermore, the companies have to connect with the relevant environmental bodies to

ensure that they abide by all the environmental conservation laws concerning the mining

process11. While there are different bodies in the two localities of operations, the structure of

engagement is similar in the two projects. The following diagram summarizes the company’s

engagement with environmental conservation bodies.

Fig 1.2

10 Kullenberg, Janosch. 2016. “Community Liaison Assistants: A Bridge between Peacekeepers

and Local Populations.” Forced Migration Review 1 (53): 44–47.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=119163575&site=ehost-live.

11 Lunstrum, Elizabeth, Pablo Bose, and Anna Zalik. 2016. “Environmental Displacement: The

Common Ground of Climate Change, Extraction and Conservation.” Area 48 (2): 130–33.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=115403930&site=ehost-live.

the region10. The community liaison officers are charged with the responsibility of organizing

and conducting community engagement forums and passage of critical information between the

project management and the community. While the two companies make use of a similar

structure, there exists a slight difference inters of the senior management contact with the

community. Melak Coal Mine Project puts the liaison officers at the forefront when it comes to

community engagement while the senior management of the Paddington Gold Mine project

chooses to do the engagement side by side with the community liaison officers.

Furthermore, the companies have to connect with the relevant environmental bodies to

ensure that they abide by all the environmental conservation laws concerning the mining

process11. While there are different bodies in the two localities of operations, the structure of

engagement is similar in the two projects. The following diagram summarizes the company’s

engagement with environmental conservation bodies.

Fig 1.2

10 Kullenberg, Janosch. 2016. “Community Liaison Assistants: A Bridge between Peacekeepers

and Local Populations.” Forced Migration Review 1 (53): 44–47.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=119163575&site=ehost-live.

11 Lunstrum, Elizabeth, Pablo Bose, and Anna Zalik. 2016. “Environmental Displacement: The

Common Ground of Climate Change, Extraction and Conservation.” Area 48 (2): 130–33.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=115403930&site=ehost-live.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Even though community liaison officers are vital for the representation of the community’s

opinion on the environmental issues, the companies also rely on the analysis of the

environmental bodies and organizations that operate within the locality12.

Reporting of the community relations activities

The two have similar reporting mechanisms for the community activities that they carry

out. The first common reporting technique that both the companies if the inclusion of the

community projects in the companies’ regular reports. Furthermore, the regular stakeholder

meetings create a good avenue for the companies to present a verbal explanation of their

intended community development project and also elaborate on what they can comfortably do

for the community and what they cannot do. The expectations of the community in most

instances are always beyond what the company can deliver to the community13. It is therefore

essential that the community liaison officers aid in the shaping of the community expectations to

avoid cases of discontent and hostility among the community members.

Conclusion

The two projects, the Paddington Gold Mine project, and Melak Coal Mine Project are

implemented by two different Australian companies in different geographical locations.

Moreover, there is also a variance between the natures of the two projects as they deal with two

12 Haalboom, B 2011, ‘Framed Encounters with Conservation and Mining Development:

Indigenous Peoples’ use of Strategic Framing in Suriname’, Social Movement Studies, vol. 10,

no. 4, pp. 387–406, viewed 17 October 2018, <http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=67366739&site=ehost-live>.

13 Patzer, Moritz, Christian Voegtlin, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2018. “The Normative

Justification of Integrative Stakeholder Engagement: A Habermasian View on Responsible

Leadership.” Business Ethics Quarterly 28 (3): 325–54. doi:10.1017/beq.2017.33.

opinion on the environmental issues, the companies also rely on the analysis of the

environmental bodies and organizations that operate within the locality12.

Reporting of the community relations activities

The two have similar reporting mechanisms for the community activities that they carry

out. The first common reporting technique that both the companies if the inclusion of the

community projects in the companies’ regular reports. Furthermore, the regular stakeholder

meetings create a good avenue for the companies to present a verbal explanation of their

intended community development project and also elaborate on what they can comfortably do

for the community and what they cannot do. The expectations of the community in most

instances are always beyond what the company can deliver to the community13. It is therefore

essential that the community liaison officers aid in the shaping of the community expectations to

avoid cases of discontent and hostility among the community members.

Conclusion

The two projects, the Paddington Gold Mine project, and Melak Coal Mine Project are

implemented by two different Australian companies in different geographical locations.

Moreover, there is also a variance between the natures of the two projects as they deal with two

12 Haalboom, B 2011, ‘Framed Encounters with Conservation and Mining Development:

Indigenous Peoples’ use of Strategic Framing in Suriname’, Social Movement Studies, vol. 10,

no. 4, pp. 387–406, viewed 17 October 2018, <http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=67366739&site=ehost-live>.

13 Patzer, Moritz, Christian Voegtlin, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2018. “The Normative

Justification of Integrative Stakeholder Engagement: A Habermasian View on Responsible

Leadership.” Business Ethics Quarterly 28 (3): 325–54. doi:10.1017/beq.2017.33.

different products and the clients are also different. However, the projects exhibit a wide range of

similarities regarding community engagements. Both projects have structures in place that allows

communities’ participation in the projects. They have management structures that allow for

community liaison officers in the project management chain. The role of the community liaison

offices is similar in the two projects. The difference only comes in the level of community

engagement of the senior project management officers and the community. While one company

prefers to put the liaison officers at the forefront of the community engagement, the other

chooses to work side by side with the liaison officers to achieve the project goals and objectives.

Other than that, the concept of community engagement and community project is the same

applied by the projects. The corporate responsibility projects selected in the two scenarios are

different but based on the same concept.

similarities regarding community engagements. Both projects have structures in place that allows

communities’ participation in the projects. They have management structures that allow for

community liaison officers in the project management chain. The role of the community liaison

offices is similar in the two projects. The difference only comes in the level of community

engagement of the senior project management officers and the community. While one company

prefers to put the liaison officers at the forefront of the community engagement, the other

chooses to work side by side with the liaison officers to achieve the project goals and objectives.

Other than that, the concept of community engagement and community project is the same

applied by the projects. The corporate responsibility projects selected in the two scenarios are

different but based on the same concept.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Bibliography

Campbell, John L. 2018. “2017 Decade Award Invited Article Reflections on the 2017 Decade

Award: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Financial Crisis.” Academy of

Management Review 43 (4): 546–56. doi:10.5465/amr.2018.0057.

Chia, Kerryn, John Koch, Rohan Sadler, and Shane Turner. 2016. “Re-Establishing the Mid-

Storey Tree Persoonia Longifolia (Proteaceae) in Restored Forest Following Bauxite

Mining in Southern Western Australia.” Ecological Research 31 (5): 627–38.

doi:10.1007/s11284-016-1370-y.

CIMIC annual report. 2017. Retreved through

https://www.cimic.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/35843/4-Annual-Report-to-

shareholders.pdf

Campbell, John L. 2018. “2017 Decade Award Invited Article Reflections on the 2017 Decade

Award: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Financial Crisis.” Academy of

Management Review 43 (4): 546–56. doi:10.5465/amr.2018.0057.

Chia, Kerryn, John Koch, Rohan Sadler, and Shane Turner. 2016. “Re-Establishing the Mid-

Storey Tree Persoonia Longifolia (Proteaceae) in Restored Forest Following Bauxite

Mining in Southern Western Australia.” Ecological Research 31 (5): 627–38.

doi:10.1007/s11284-016-1370-y.

CIMIC annual report. 2017. Retreved through

https://www.cimic.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/35843/4-Annual-Report-to-

shareholders.pdf

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis.” 2018. CIMIC Group Limited SWOT Analysis,

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=buh&AN=131348345&site=ehost-live.

Haalboom, B 2011, ‘Framed Encounters with Conservation and Mining Development:

Indigenous Peoples’ use of Strategic Framing in Suriname’, Social Movement Studies, 10

(4), pp. 387–406, viewed 17 October 2018, <http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=67366739&site=ehost-live>.

Herremans, Irene1, irene.herremans@haskayne.ucalgary.ca, Jamal2, jnazari@sfu.ca Nazari, and

Fereshteh, fmahmoud@sfu.ca Mahmoudian. 2016. “Stakeholder Relationships,

Engagement, and Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics 138 (3): 417–35.

doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2634-0.

Kullenberg, Janosch. 2016. “Community Liaison Assistants: A Bridge between Peacekeepers

and Local Populations.” Forced Migration Review 1 (53): 44–47.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=119163575&site=ehost-live.

Lunstrum, Elizabeth, Pablo Bose, and Anna Zalik. 2016. “Environmental Displacement: The

Common Ground of Climate Change, Extraction and Conservation.” Area 48 (2): 130–

33. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=s3h&AN=115403930&site=ehost-live.

Maciej, Nowak, Targiel S. Krzysztof, Błaszczyk Bożena, and Kania Sebastian. 2018.

“Stakeholders in Mining Projects.” Project Management Development - Practice &

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=buh&AN=131348345&site=ehost-live.

Haalboom, B 2011, ‘Framed Encounters with Conservation and Mining Development:

Indigenous Peoples’ use of Strategic Framing in Suriname’, Social Movement Studies, 10

(4), pp. 387–406, viewed 17 October 2018, <http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=67366739&site=ehost-live>.

Herremans, Irene1, irene.herremans@haskayne.ucalgary.ca, Jamal2, jnazari@sfu.ca Nazari, and

Fereshteh, fmahmoud@sfu.ca Mahmoudian. 2016. “Stakeholder Relationships,

Engagement, and Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics 138 (3): 417–35.

doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2634-0.

Kullenberg, Janosch. 2016. “Community Liaison Assistants: A Bridge between Peacekeepers

and Local Populations.” Forced Migration Review 1 (53): 44–47.

http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=aph&AN=119163575&site=ehost-live.

Lunstrum, Elizabeth, Pablo Bose, and Anna Zalik. 2016. “Environmental Displacement: The

Common Ground of Climate Change, Extraction and Conservation.” Area 48 (2): 130–

33. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=s3h&AN=115403930&site=ehost-live.

Maciej, Nowak, Targiel S. Krzysztof, Błaszczyk Bożena, and Kania Sebastian. 2018.

“Stakeholders in Mining Projects.” Project Management Development - Practice &

Perspectives, January, 66–74. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=buh&AN=130498229&site=ehost-live.

Marsh, Jillian K. 2013. “Decolonising the Interface between Indigenous Peoples and Mining

Companies in Australia: Making Space for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Asia Pacific

Viewpoint 54 (2): 171–84. doi:10.1111/apv.12017.

Patzer, Moritz, Christian Voegtlin, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2018. “The Normative

Justification of Integrative Stakeholder Engagement: A Habermasian View on

Responsible Leadership.” Business Ethics Quarterly 28 (3): 325–54.

doi:10.1017/beq.2017.33.

Provasnek, Anna Katharina1, anna.provasnek@gmail.com, Erwin1, erwin.schmid@boku.ac.at

Schmid, and Gerald2,3, gsteiner@wcfia.harvard.edu, gerald.steiner@donau-uni.ac.at

Steiner. 2018. “Stakeholder Engagement: Keeping Business Legitimate in Austria’s

Natural Mineral Water Bottling Industry.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (2): 467–84.

doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3121-y.

direct=true&db=buh&AN=130498229&site=ehost-live.

Marsh, Jillian K. 2013. “Decolonising the Interface between Indigenous Peoples and Mining

Companies in Australia: Making Space for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Asia Pacific

Viewpoint 54 (2): 171–84. doi:10.1111/apv.12017.

Patzer, Moritz, Christian Voegtlin, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2018. “The Normative

Justification of Integrative Stakeholder Engagement: A Habermasian View on

Responsible Leadership.” Business Ethics Quarterly 28 (3): 325–54.

doi:10.1017/beq.2017.33.

Provasnek, Anna Katharina1, anna.provasnek@gmail.com, Erwin1, erwin.schmid@boku.ac.at

Schmid, and Gerald2,3, gsteiner@wcfia.harvard.edu, gerald.steiner@donau-uni.ac.at

Steiner. 2018. “Stakeholder Engagement: Keeping Business Legitimate in Austria’s

Natural Mineral Water Bottling Industry.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (2): 467–84.

doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3121-y.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.