National Security and Homeland Security Strategies

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/26

|22

|8330

|225

Report

AI Summary

The provided content includes a variety of documents and resources related to homeland security, national strategy, counterterrorism, and emergency response. The documents include presidential policies, national strategies, and reports from various government agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Food and Drug Administration. The resources also cover topics like cybersecurity, critical infrastructure protection, and pandemic influenza preparedness. Additionally, there are glossaries, organizational charts, and historical information about the development of homeland security policies.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Module 2: Homeland Security Strategy and

Policy

Topics

1. Immediate Actions—Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2001 to 2004

2. The 9/11 Commission Report—General Findings and Recommendations

3. Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2004 to the Present

4. Summary

1. Immediate Actions—Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2001 to 2004

We believe the 9/11 attacks revealed four kinds of failures: in imagination, policy, capability,

and management.

—9/11 Commission

The surprise and shock of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, required an immediate

government response. The government's actions of the period from September 2001 to the

release of The 9/11 Commission Report in July 2004 are considered immediate actions. These

actions were also influenced by the immediately following anthrax attacks of September and

October 2001. The people demanded swift governmental action to find those responsible for the

attacks and ensure that they would not occur again.

The following section outlines the major actions taken by the federal government during that

time frame. We have divided the discussion into legislative (congressional) and executive

(presidential and military) actions. A brief description of each policy and its implications for

homeland security is presented through interactive timelines, and we will discuss several of the

major policies and strategies in greater detail. The focus will remain on the homeland security

mission, essentially the "home game" against terrorism. Homeland defense (the "away game")

against terrorism will be briefly mentioned, but the focus in this course is on domestic homeland

security policy and its effects on the United States; its citizens; and state, local, and tribal

governments.

Legislative Actions, 2001 to 2004

Legislative actions consist of the steps that the US Congress takes to abate terrorism through the

passage of new laws. Once signed by the president of the United States, these proposals become

law, providing additional funding and/or new legal tools to combat terrorism.

The period immediately following September 11 saw a flurry of activity by Congress to

authorize presidential action for the use of military force, to provide for the safety and stability of

Policy

Topics

1. Immediate Actions—Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2001 to 2004

2. The 9/11 Commission Report—General Findings and Recommendations

3. Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2004 to the Present

4. Summary

1. Immediate Actions—Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2001 to 2004

We believe the 9/11 attacks revealed four kinds of failures: in imagination, policy, capability,

and management.

—9/11 Commission

The surprise and shock of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, required an immediate

government response. The government's actions of the period from September 2001 to the

release of The 9/11 Commission Report in July 2004 are considered immediate actions. These

actions were also influenced by the immediately following anthrax attacks of September and

October 2001. The people demanded swift governmental action to find those responsible for the

attacks and ensure that they would not occur again.

The following section outlines the major actions taken by the federal government during that

time frame. We have divided the discussion into legislative (congressional) and executive

(presidential and military) actions. A brief description of each policy and its implications for

homeland security is presented through interactive timelines, and we will discuss several of the

major policies and strategies in greater detail. The focus will remain on the homeland security

mission, essentially the "home game" against terrorism. Homeland defense (the "away game")

against terrorism will be briefly mentioned, but the focus in this course is on domestic homeland

security policy and its effects on the United States; its citizens; and state, local, and tribal

governments.

Legislative Actions, 2001 to 2004

Legislative actions consist of the steps that the US Congress takes to abate terrorism through the

passage of new laws. Once signed by the president of the United States, these proposals become

law, providing additional funding and/or new legal tools to combat terrorism.

The period immediately following September 11 saw a flurry of activity by Congress to

authorize presidential action for the use of military force, to provide for the safety and stability of

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

the airline industry, to authorize new powers for law enforcement and intelligence authorities, to

enhance border security, to increase bioterrorism preparedness, to protect cyberspace and the

maritime environment, and to create the Department of Homeland Security.

Look for the link titled Timeline in the main module area. Click that link to see an interactive

timeline that summarizes the legislative responses—as well as the executive responses, which

we'll discuss later in this module—to the terrorist attacks of September 11 and subsequent major

events.

The USA PATRIOT Act

The USA PATRIOT Act, which was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Bush

on October 26, 2001, broadened the ability of law enforcement and intelligence agencies to

interdict terrorism in four ways (Congressional Research Service [CRS], 2002). First, it applied

toward the fight against terrorism a number of investigative tools that had previously been

available to fight other forms of organized crime. Second, the act removed many of the legal

barriers that prevented the intelligence community (IC) from sharing information with law

enforcement. Third, it updated laws to reflect new technology and new threats. Fourth, it

increased penalties and created new offenses for terrorism-related crimes. We will explore each

of these elements to develop an understanding of the scope of the changes effected by the

PATRIOT Act.

Many provisions of the PATRIOT Act are viewed by some as too great an expansion of

government power, which could violate the constitutional rights of American citizens.

The following is a brief summary of the major changes provided for in the USA PATRIOT Act,

as explained by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) in "The USA PATRIOT Act: Preserving

Life and Liberty?" (n.d.):

1. Legalized the use of a greater range of tools to fight terrorism

o allows law enforcement to use electronic surveillance against the full range of

terrorism-related crimes

o allows federal agents to follow terrorists by using "roving wiretaps" that can be

authorized by a federal judge to apply to a particular suspect, rather than just a

particular phone or device

o allows law enforcement to conduct investigations without tipping off terrorists, by

delaying when the subject is told that a search warrant was executed; this delay

gives law enforcement time to identify associates, eliminate immediate threats to

our communities, and coordinate the arrests of multiple individuals

o allows federal agents to ask a court for an order to examine business records from

the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for activity in terrorism cases, if

needed to aid a terrorism investigation

2. Enabled information sharing

enhance border security, to increase bioterrorism preparedness, to protect cyberspace and the

maritime environment, and to create the Department of Homeland Security.

Look for the link titled Timeline in the main module area. Click that link to see an interactive

timeline that summarizes the legislative responses—as well as the executive responses, which

we'll discuss later in this module—to the terrorist attacks of September 11 and subsequent major

events.

The USA PATRIOT Act

The USA PATRIOT Act, which was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Bush

on October 26, 2001, broadened the ability of law enforcement and intelligence agencies to

interdict terrorism in four ways (Congressional Research Service [CRS], 2002). First, it applied

toward the fight against terrorism a number of investigative tools that had previously been

available to fight other forms of organized crime. Second, the act removed many of the legal

barriers that prevented the intelligence community (IC) from sharing information with law

enforcement. Third, it updated laws to reflect new technology and new threats. Fourth, it

increased penalties and created new offenses for terrorism-related crimes. We will explore each

of these elements to develop an understanding of the scope of the changes effected by the

PATRIOT Act.

Many provisions of the PATRIOT Act are viewed by some as too great an expansion of

government power, which could violate the constitutional rights of American citizens.

The following is a brief summary of the major changes provided for in the USA PATRIOT Act,

as explained by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) in "The USA PATRIOT Act: Preserving

Life and Liberty?" (n.d.):

1. Legalized the use of a greater range of tools to fight terrorism

o allows law enforcement to use electronic surveillance against the full range of

terrorism-related crimes

o allows federal agents to follow terrorists by using "roving wiretaps" that can be

authorized by a federal judge to apply to a particular suspect, rather than just a

particular phone or device

o allows law enforcement to conduct investigations without tipping off terrorists, by

delaying when the subject is told that a search warrant was executed; this delay

gives law enforcement time to identify associates, eliminate immediate threats to

our communities, and coordinate the arrests of multiple individuals

o allows federal agents to ask a court for an order to examine business records from

the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for activity in terrorism cases, if

needed to aid a terrorism investigation

2. Enabled information sharing

o abolished the legal barriers that previously prevented the sharing of information

between the law enforcement and intelligence communities, allowing

coordination of information among the agencies to counter terrorism

3. Updated laws to reflect new technology

o allows warrants to be obtained in any district in where the terrorism activity being

investigated occurred, regardless of where those warrants will be executed

o allows cyber hacking victims to give law enforcement access to systems to

investigate and prosecute hackers

4. Increased penalties and added new offenses for terrorism-related crimes

o created a new offense that prohibits knowingly harboring persons involved in

terrorist offenses

o expanded the definitions of some conspiracy crimes and increased the number of

distinct conspiracy offenses

o increases the maximum penalties for terrorist crimes, including conspiracy crimes

o creates specific punishments for attacks using biological weapons and attacks on

mass transit

o eliminates the statutes of limitations on some terrorist crimes, and lengthens it on

others

The PATRIOT Act has spurred much debate concerning the balance between freedom and

security in America. Proponents of the act support the need for expanded law enforcement with

expanded powers to fight terrorism. Opponents cite the potential for abuses of rights that could

occur under the provisions of the act. Opponents of the act were fueled by a DOJ Office of the

Inspector General report that found abuses of the use of National Security Letters (USA

PATRIOT Act, Section 505) to obtain information from businesses and educational institutions

for investigations (2007). The act as originally legislated included sunset provisions that were to

expire at the end of 2005 unless expressly reauthorized. In 2006, the act was reauthorized,

making all sections of the original act permanent except for two sections: the National Security

Letters and roving wiretap provisions were reauthorized with four-year expirations. In 2011,

these provisions were again reauthorized for four years. The effectiveness of the PATRIOT Act

and its impact on the rights of American citizens continue as a topic of debate.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002

Dozens of agencies charged with homeland security will now be located within one Cabinet

department with the mandate and legal authority to protect our people. America will be better

able to respond to any future attacks, to reduce our vulnerability and, most important, prevent

the terrorists from taking innocent American lives.

—President George W. Bush, on signing the Homeland Security Act of 2002

between the law enforcement and intelligence communities, allowing

coordination of information among the agencies to counter terrorism

3. Updated laws to reflect new technology

o allows warrants to be obtained in any district in where the terrorism activity being

investigated occurred, regardless of where those warrants will be executed

o allows cyber hacking victims to give law enforcement access to systems to

investigate and prosecute hackers

4. Increased penalties and added new offenses for terrorism-related crimes

o created a new offense that prohibits knowingly harboring persons involved in

terrorist offenses

o expanded the definitions of some conspiracy crimes and increased the number of

distinct conspiracy offenses

o increases the maximum penalties for terrorist crimes, including conspiracy crimes

o creates specific punishments for attacks using biological weapons and attacks on

mass transit

o eliminates the statutes of limitations on some terrorist crimes, and lengthens it on

others

The PATRIOT Act has spurred much debate concerning the balance between freedom and

security in America. Proponents of the act support the need for expanded law enforcement with

expanded powers to fight terrorism. Opponents cite the potential for abuses of rights that could

occur under the provisions of the act. Opponents of the act were fueled by a DOJ Office of the

Inspector General report that found abuses of the use of National Security Letters (USA

PATRIOT Act, Section 505) to obtain information from businesses and educational institutions

for investigations (2007). The act as originally legislated included sunset provisions that were to

expire at the end of 2005 unless expressly reauthorized. In 2006, the act was reauthorized,

making all sections of the original act permanent except for two sections: the National Security

Letters and roving wiretap provisions were reauthorized with four-year expirations. In 2011,

these provisions were again reauthorized for four years. The effectiveness of the PATRIOT Act

and its impact on the rights of American citizens continue as a topic of debate.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002

Dozens of agencies charged with homeland security will now be located within one Cabinet

department with the mandate and legal authority to protect our people. America will be better

able to respond to any future attacks, to reduce our vulnerability and, most important, prevent

the terrorists from taking innocent American lives.

—President George W. Bush, on signing the Homeland Security Act of 2002

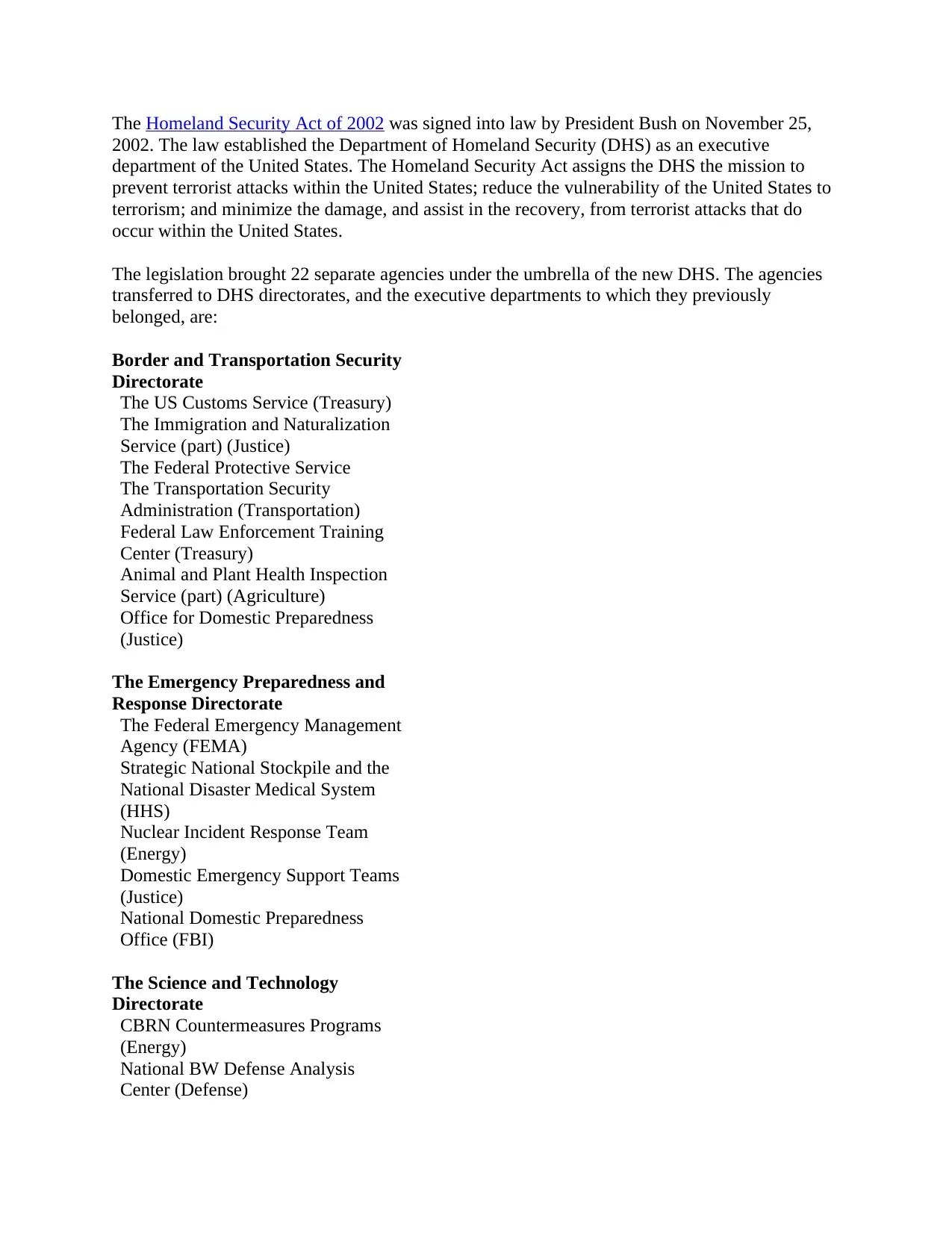

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 was signed into law by President Bush on November 25,

2002. The law established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as an executive

department of the United States. The Homeland Security Act assigns the DHS the mission to

prevent terrorist attacks within the United States; reduce the vulnerability of the United States to

terrorism; and minimize the damage, and assist in the recovery, from terrorist attacks that do

occur within the United States.

The legislation brought 22 separate agencies under the umbrella of the new DHS. The agencies

transferred to DHS directorates, and the executive departments to which they previously

belonged, are:

Border and Transportation Security

Directorate

The US Customs Service (Treasury)

The Immigration and Naturalization

Service (part) (Justice)

The Federal Protective Service

The Transportation Security

Administration (Transportation)

Federal Law Enforcement Training

Center (Treasury)

Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service (part) (Agriculture)

Office for Domestic Preparedness

(Justice)

The Emergency Preparedness and

Response Directorate

The Federal Emergency Management

Agency (FEMA)

Strategic National Stockpile and the

National Disaster Medical System

(HHS)

Nuclear Incident Response Team

(Energy)

Domestic Emergency Support Teams

(Justice)

National Domestic Preparedness

Office (FBI)

The Science and Technology

Directorate

CBRN Countermeasures Programs

(Energy)

National BW Defense Analysis

Center (Defense)

2002. The law established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as an executive

department of the United States. The Homeland Security Act assigns the DHS the mission to

prevent terrorist attacks within the United States; reduce the vulnerability of the United States to

terrorism; and minimize the damage, and assist in the recovery, from terrorist attacks that do

occur within the United States.

The legislation brought 22 separate agencies under the umbrella of the new DHS. The agencies

transferred to DHS directorates, and the executive departments to which they previously

belonged, are:

Border and Transportation Security

Directorate

The US Customs Service (Treasury)

The Immigration and Naturalization

Service (part) (Justice)

The Federal Protective Service

The Transportation Security

Administration (Transportation)

Federal Law Enforcement Training

Center (Treasury)

Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service (part) (Agriculture)

Office for Domestic Preparedness

(Justice)

The Emergency Preparedness and

Response Directorate

The Federal Emergency Management

Agency (FEMA)

Strategic National Stockpile and the

National Disaster Medical System

(HHS)

Nuclear Incident Response Team

(Energy)

Domestic Emergency Support Teams

(Justice)

National Domestic Preparedness

Office (FBI)

The Science and Technology

Directorate

CBRN Countermeasures Programs

(Energy)

National BW Defense Analysis

Center (Defense)

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Plum Island Animal Disease Center

(Agriculture)

Environmental Measurements

Laboratory (Energy)

The Information Analysis and

Infrastructure Protection

Directorate

Federal Computer Incident Response

Center (GSA)

National Communications System

(Defense)

National Infrastructure Protection

Center (FBI)

Energy Security and Assurance

Program (Energy)

Direct Report to the Secretary of

DHS

US Secret Service

US Coast Guard

Direct Report to the Deputy

Secretary of DHS

US Citizenship and Immigration

Services

Source: US DHS, n.d.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 initiated the largest reorganization of the federal

government since the creation of the Department of Defense in 1947. Those critical of the

reorganization claim that adding bureaucracy does not close the gaps exposed by the attacks of

September 11. Opposition also centers on the potential for constitutional right infringements by a

large law enforcement and intelligence organization. As with the USA PATRIOT Act, the

effectiveness and impact of the creation of the DHS by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 will

continue as a topic of debate.

The legislative actions presented in this section represent the immediate action taken by

Congress in the wake of the attacks of September 11. The laws created by Congress served to

authorize presidential action for the use military force

provide for the safety and stability of the airline industry

authorize new powers for law enforcement and intelligence authorities

enhance border security, increase bioterrorism preparedness

(Agriculture)

Environmental Measurements

Laboratory (Energy)

The Information Analysis and

Infrastructure Protection

Directorate

Federal Computer Incident Response

Center (GSA)

National Communications System

(Defense)

National Infrastructure Protection

Center (FBI)

Energy Security and Assurance

Program (Energy)

Direct Report to the Secretary of

DHS

US Secret Service

US Coast Guard

Direct Report to the Deputy

Secretary of DHS

US Citizenship and Immigration

Services

Source: US DHS, n.d.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 initiated the largest reorganization of the federal

government since the creation of the Department of Defense in 1947. Those critical of the

reorganization claim that adding bureaucracy does not close the gaps exposed by the attacks of

September 11. Opposition also centers on the potential for constitutional right infringements by a

large law enforcement and intelligence organization. As with the USA PATRIOT Act, the

effectiveness and impact of the creation of the DHS by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 will

continue as a topic of debate.

The legislative actions presented in this section represent the immediate action taken by

Congress in the wake of the attacks of September 11. The laws created by Congress served to

authorize presidential action for the use military force

provide for the safety and stability of the airline industry

authorize new powers for law enforcement and intelligence authorities

enhance border security, increase bioterrorism preparedness

protect cyberspace and the maritime environments

create the DHS

Of all of the legislative actions during this period, the USA PATRIOT Act and the Homeland

Security Act of 2002 have had the most significant effects on the security of the homeland.

Executive Actions, 2001 to 2004

Following the events of September 11, President George W. Bush also utilized the powers

granted him under the US Constitution to determine the strategic direction of homeland security

policy. The president has the authority to issue executive orders that have the force of law.

Executive orders (EOs) usually are based on existing statutory authority of the president and

require no action by Congress to become effective. Following September 11, the president issued

several executive orders and, for the first time, EOs titled Homeland Security Presidential

Directives (HSPDs). The HSPDs issued between 2001 and 2004 set the direction for US

homeland security policy. The timeline in this module traces the actions taken by the president

between the September 11 attacks and the release of the 9/11 Commission Report in July 2004.

We will focus our discussion on three particular executive orders that have broad implications:

HSPD-3, HSPD-5, and HSPD-8 (replaced by PPD-8 in 2011). These directives have influenced

homeland security policy at the federal, state, and local levels of government and have been

translated into strategy documents and plans that affected the entire nation.

Focus on the Executive: Homeland Security Presidential Directives 3, 5, and 8

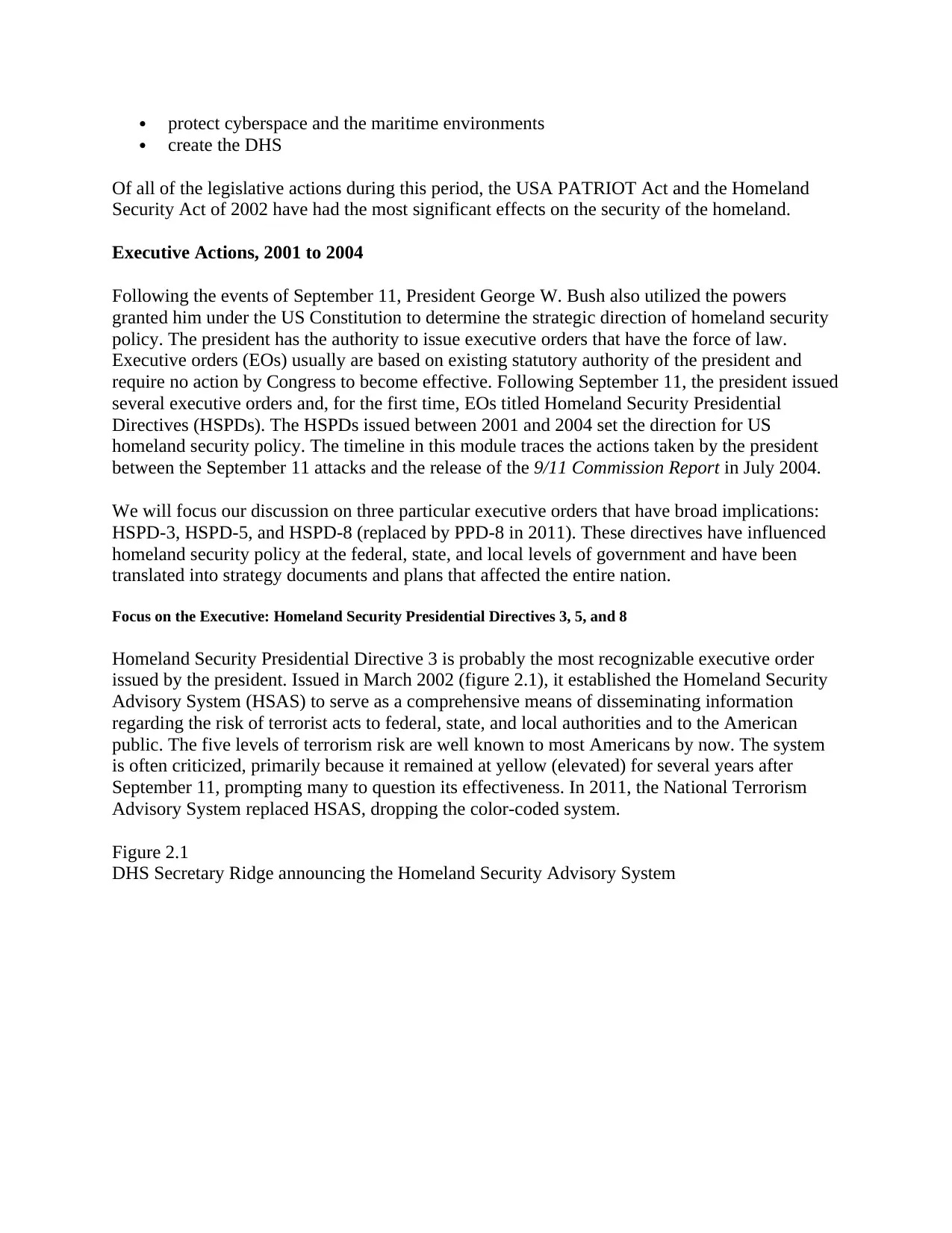

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 3 is probably the most recognizable executive order

issued by the president. Issued in March 2002 (figure 2.1), it established the Homeland Security

Advisory System (HSAS) to serve as a comprehensive means of disseminating information

regarding the risk of terrorist acts to federal, state, and local authorities and to the American

public. The five levels of terrorism risk are well known to most Americans by now. The system

is often criticized, primarily because it remained at yellow (elevated) for several years after

September 11, prompting many to question its effectiveness. In 2011, the National Terrorism

Advisory System replaced HSAS, dropping the color-coded system.

Figure 2.1

DHS Secretary Ridge announcing the Homeland Security Advisory System

create the DHS

Of all of the legislative actions during this period, the USA PATRIOT Act and the Homeland

Security Act of 2002 have had the most significant effects on the security of the homeland.

Executive Actions, 2001 to 2004

Following the events of September 11, President George W. Bush also utilized the powers

granted him under the US Constitution to determine the strategic direction of homeland security

policy. The president has the authority to issue executive orders that have the force of law.

Executive orders (EOs) usually are based on existing statutory authority of the president and

require no action by Congress to become effective. Following September 11, the president issued

several executive orders and, for the first time, EOs titled Homeland Security Presidential

Directives (HSPDs). The HSPDs issued between 2001 and 2004 set the direction for US

homeland security policy. The timeline in this module traces the actions taken by the president

between the September 11 attacks and the release of the 9/11 Commission Report in July 2004.

We will focus our discussion on three particular executive orders that have broad implications:

HSPD-3, HSPD-5, and HSPD-8 (replaced by PPD-8 in 2011). These directives have influenced

homeland security policy at the federal, state, and local levels of government and have been

translated into strategy documents and plans that affected the entire nation.

Focus on the Executive: Homeland Security Presidential Directives 3, 5, and 8

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 3 is probably the most recognizable executive order

issued by the president. Issued in March 2002 (figure 2.1), it established the Homeland Security

Advisory System (HSAS) to serve as a comprehensive means of disseminating information

regarding the risk of terrorist acts to federal, state, and local authorities and to the American

public. The five levels of terrorism risk are well known to most Americans by now. The system

is often criticized, primarily because it remained at yellow (elevated) for several years after

September 11, prompting many to question its effectiveness. In 2011, the National Terrorism

Advisory System replaced HSAS, dropping the color-coded system.

Figure 2.1

DHS Secretary Ridge announcing the Homeland Security Advisory System

Source: White House Photos, "War on Terror"

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5 was issued in February 2003. HSPD-5 instructed the

secretary of Homeland Security to establish a single, comprehensive system for managing

domestic incidents. The resulting policy, the National Incident Management System (NIMS),

which we will examine in a later module, has had far-reaching effects on federal agencies, as

well as on state and local governments. The NIMS Integration Center, also created by HSPD-5,

was charged with the responsibility for developing standards for training, personnel certification,

and other incident management–related elements. HSPD-5 arguably has had a greater effect on

operations at the state and local government levels than has any other homeland security policy.

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 8 was issued in December 2003 as a companion to

HSPD-5. This directive required the secretary of the DHS to establish a national preparedness

goal that includes "readiness metrics and elements that support the national preparedness goal,

including standards for preparedness assessments and strategies, and a system for assessing the

nation's overall preparedness to respond to major events, especially those involving acts of

terrorism." This directive required states and Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) cities to

express funding proposals in terms of measurable capabilities. HSPD-8 has resulted in a host of

guidance documents and the development of the Capabilities-Based Planning process, which is

used to determine capability gaps. We will discuss HSPD-8 documents and processes in greater

detail in the National Preparedness Module.

From the moments following the terrorist attacks on September 11 until mid-2004, the actions of

the president—effected through the issuance of Homeland Security Presidential Directives and

Executive Orders—served to define the direction of homeland security policies and procedures.

Legislative actions during the same period provided broad authorities, and executive power

shaped the direction of specific policy. To the furthest extent possible under the law, executive

authority shaped the intelligence- and information-sharing environments, communication with

citizens regarding terrorism risks, immigration policies, protection of critical infrastructure,

management of domestic incidents, and the relationship between levels of government with

regard to homeland security preparedness. In 2011, President Obama issued Presidential Policy

Directive 8 (PPD-8), which supersedes HSPD-8. Module 4, "National Preparedness," discusses

the changes implemented under PPD-8.

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5 was issued in February 2003. HSPD-5 instructed the

secretary of Homeland Security to establish a single, comprehensive system for managing

domestic incidents. The resulting policy, the National Incident Management System (NIMS),

which we will examine in a later module, has had far-reaching effects on federal agencies, as

well as on state and local governments. The NIMS Integration Center, also created by HSPD-5,

was charged with the responsibility for developing standards for training, personnel certification,

and other incident management–related elements. HSPD-5 arguably has had a greater effect on

operations at the state and local government levels than has any other homeland security policy.

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 8 was issued in December 2003 as a companion to

HSPD-5. This directive required the secretary of the DHS to establish a national preparedness

goal that includes "readiness metrics and elements that support the national preparedness goal,

including standards for preparedness assessments and strategies, and a system for assessing the

nation's overall preparedness to respond to major events, especially those involving acts of

terrorism." This directive required states and Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) cities to

express funding proposals in terms of measurable capabilities. HSPD-8 has resulted in a host of

guidance documents and the development of the Capabilities-Based Planning process, which is

used to determine capability gaps. We will discuss HSPD-8 documents and processes in greater

detail in the National Preparedness Module.

From the moments following the terrorist attacks on September 11 until mid-2004, the actions of

the president—effected through the issuance of Homeland Security Presidential Directives and

Executive Orders—served to define the direction of homeland security policies and procedures.

Legislative actions during the same period provided broad authorities, and executive power

shaped the direction of specific policy. To the furthest extent possible under the law, executive

authority shaped the intelligence- and information-sharing environments, communication with

citizens regarding terrorism risks, immigration policies, protection of critical infrastructure,

management of domestic incidents, and the relationship between levels of government with

regard to homeland security preparedness. In 2011, President Obama issued Presidential Policy

Directive 8 (PPD-8), which supersedes HSPD-8. Module 4, "National Preparedness," discusses

the changes implemented under PPD-8.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Homeland Security Strategy, 2001 to 2004

strategy: a prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a

synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives

—US DoD, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms

The period from 2001 to 2004 also saw the development of several strategy documents designed

to provide direction for the development of homeland security programs. Strategies are

essentially statements of how we are going to get from where we are now to the future condition

that is sought. The process of defining a strategy begins with setting a goal. Once established,

the strategy forms the road map to achieving the goal.

Many strategy documents were developed during the period of 2001 to 2004. Although each

strategy drills down to a specific area or mission of homeland security, our focus will be on the

overarching strategic direction provided by the National Strategy for Homeland Security.

Focus on Strategy: The National Strategy for Homeland Security

The National Strategy for Homeland Security (NSHS) is the key document for understanding the

strategic direction of homeland security. The development of this strategy was ordered by the

president in conjunction with the creation of the Office of Homeland Security in Executive Order

13228. The NSHS is the first document to provide a definition for homeland security: "a

concerted national effort to prevent terrorist attacks within the United States, reduce America's

vulnerability to terrorism, and minimize the damage and recover from attacks that do occur"

(President of the United States, NSHS, 2002). It also indicates that "the responsibility of

providing homeland security is shared between federal, state and local governments, and the

private sector" (President of the United States, NSHS, 2002). An updated version of The

National Strategy for Homeland Security was last released in 2007. The Obama administration

has not updated the National Strategy for Homeland Security.

Based on the definition, the 2002 NSHS identified three strategic objectives, in priority order:

1. prevention of terrorist attacks within the United States

2. reduction of America's vulnerability to terrorism

3. minimize the damage and recover from attacks that do occur

The 2002 NSHS also identified eight principles that guide the implementation of homeland

security programs:

require responsibility and accountability

mobilize our entire society

manage risk and allocate resources judiciously

seek opportunity out of adversity

foster flexibility

measure preparedness

strategy: a prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a

synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives

—US DoD, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms

The period from 2001 to 2004 also saw the development of several strategy documents designed

to provide direction for the development of homeland security programs. Strategies are

essentially statements of how we are going to get from where we are now to the future condition

that is sought. The process of defining a strategy begins with setting a goal. Once established,

the strategy forms the road map to achieving the goal.

Many strategy documents were developed during the period of 2001 to 2004. Although each

strategy drills down to a specific area or mission of homeland security, our focus will be on the

overarching strategic direction provided by the National Strategy for Homeland Security.

Focus on Strategy: The National Strategy for Homeland Security

The National Strategy for Homeland Security (NSHS) is the key document for understanding the

strategic direction of homeland security. The development of this strategy was ordered by the

president in conjunction with the creation of the Office of Homeland Security in Executive Order

13228. The NSHS is the first document to provide a definition for homeland security: "a

concerted national effort to prevent terrorist attacks within the United States, reduce America's

vulnerability to terrorism, and minimize the damage and recover from attacks that do occur"

(President of the United States, NSHS, 2002). It also indicates that "the responsibility of

providing homeland security is shared between federal, state and local governments, and the

private sector" (President of the United States, NSHS, 2002). An updated version of The

National Strategy for Homeland Security was last released in 2007. The Obama administration

has not updated the National Strategy for Homeland Security.

Based on the definition, the 2002 NSHS identified three strategic objectives, in priority order:

1. prevention of terrorist attacks within the United States

2. reduction of America's vulnerability to terrorism

3. minimize the damage and recover from attacks that do occur

The 2002 NSHS also identified eight principles that guide the implementation of homeland

security programs:

require responsibility and accountability

mobilize our entire society

manage risk and allocate resources judiciously

seek opportunity out of adversity

foster flexibility

measure preparedness

sustain efforts over the long term

constrain government spending

The 2002 strategy further identifies six critical mission areas that form the core of homeland

security:

intelligence and warning

border and transportation security

domestic counterterrorism

protecting critical infrastructures and key assets

defending against catastrophic threats

emergency preparedness and response

Each mission area contains a set of major initiatives designed to achieve a secure homeland.

The future of homeland security was shaped by the legislative and executive actions that

followed the attacks of September 11. Through legislation, new tools were given to law

enforcement, and the responsibility for homeland security was consolidated into the newly

formed DHS. Executive actions shaped the homeland security environment by developing new

programs and providing guidance and strategy for achieving a secure homeland.

The governmental actions from 2001 to 2004 left an indelible mark on American government,

resulting in new legal authorities and the largest reorganization of the federal government in 50

years. The decisions made during this period will be judged for decades to come. There are no

definitive measures to quantify the effectiveness of these decisions; the question is what to use as

a measure—the number of terrorist attacks, or the level of preparedness of America (the latter

also lacks a way to definitively measure). The actions of the period were undertaken without the

benefit of hindsight, and in a time when Americans were demanding that the government do

something to protect them from terrorism.

Return to top of page

2. The 9/11 Commission Report—General Findings and Recommendations

imagination: the act or power of forming a mental image of something not present to the senses

or never before wholly perceived in reality

—Merriam-Webster Online

In this module, our study of strategy and policy is segmented by the release of the findings of the

National Commission for the Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (9/11 Commission)

through The 9/11 Commission Report. The 9/11 Commission Report provides a complete

investigation into the events of September 11, including an examination of the perpetrators and

of the US government agencies and systems that were unable to counter the attacks. The policies

constrain government spending

The 2002 strategy further identifies six critical mission areas that form the core of homeland

security:

intelligence and warning

border and transportation security

domestic counterterrorism

protecting critical infrastructures and key assets

defending against catastrophic threats

emergency preparedness and response

Each mission area contains a set of major initiatives designed to achieve a secure homeland.

The future of homeland security was shaped by the legislative and executive actions that

followed the attacks of September 11. Through legislation, new tools were given to law

enforcement, and the responsibility for homeland security was consolidated into the newly

formed DHS. Executive actions shaped the homeland security environment by developing new

programs and providing guidance and strategy for achieving a secure homeland.

The governmental actions from 2001 to 2004 left an indelible mark on American government,

resulting in new legal authorities and the largest reorganization of the federal government in 50

years. The decisions made during this period will be judged for decades to come. There are no

definitive measures to quantify the effectiveness of these decisions; the question is what to use as

a measure—the number of terrorist attacks, or the level of preparedness of America (the latter

also lacks a way to definitively measure). The actions of the period were undertaken without the

benefit of hindsight, and in a time when Americans were demanding that the government do

something to protect them from terrorism.

Return to top of page

2. The 9/11 Commission Report—General Findings and Recommendations

imagination: the act or power of forming a mental image of something not present to the senses

or never before wholly perceived in reality

—Merriam-Webster Online

In this module, our study of strategy and policy is segmented by the release of the findings of the

National Commission for the Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (9/11 Commission)

through The 9/11 Commission Report. The 9/11 Commission Report provides a complete

investigation into the events of September 11, including an examination of the perpetrators and

of the US government agencies and systems that were unable to counter the attacks. The policies

created prior to the release of the report were developed without the benefit of investigation and

researched knowledge of the actual governmental failures. From 2004 to the present, the

government has had the benefit of The 9/11 Commission Report to gauge the need for policy and

legal changes to improve the government's ability to interdict a September 11-style attack. In this

section of Module 2, we will review the findings and recommendations of The 9/11 Commission

Report as they relate to homeland security strategy and to legislative and executive policy.

9/11 Commission Findings: Government-wide Failures

The 9/11 Commission reported government-wide failures and grouped these failures into four

broad categories: imagination, policy, capability, and management. We will briefly explore all of

these areas and discuss their implications for future homeland security policy. The full findings

of the report describe additional specific findings, but these four broad categories of failure set

the stage for understanding the development of homeland security policy created following the

release of The 9/11 Commission Report.

Imagination

The report identifies imagination as the most important failure. In explaining this failure, the

commission concedes that "imagination is not a gift usually associated with bureaucracies"

(National Commission, p. 344). This failure is centered on the inability to recognize the scope of

the threat posed by terrorism and al-Qaeda. The media and citizens were not concerned about

terrorism, and it had not appeared to be an issue during the 2000 presidential campaigns.

According to the 9/11 Commission, the failure of the government and its intelligence institutions

to conceive the threat constitutes a failure of imagination.

Policy

The failure of policy is directed at the ineffective actions taken against al-Qaeda following the

1998 East African embassy bombings, the 1999 bombing plots against Americans in Jordan, the

capture of Ahmed Ressam before his planned attack at Los Angeles International Airport, and

the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole. The problem in dealing with the al-Qaeda phenomenon lay

in the fact that there were essentially two methods in the American arsenal for dealing with these

types of threats: criminal trial and war. The problem is described in the report as stemming from

the fact that the terrorist attacks "were committed by a loose, far-flung, nebulous conspiracy with

no territories or citizens or assets that could be readily threatened, overwhelmed, or destroyed"

(National Commission, p. 348). Countering the threat from al-Qaeda required a different method

—one the United States could not handle. The limited responses to attacks against America left

the enemy emboldened. An invasion into the al-Qaeda sanctuary in Afghanistan was not

considered. The report contends:

The United States had warned the Taliban that they would be held accountable for further attacks

by Bin Ladin against Afghanistan's US interests. The warning had been given in 1998, again in

late 1999, once more in the fall of 2000, and again in the summer of 2001. Delivering it

repeatedly did not make it more effective (National Commission, p. 350).

researched knowledge of the actual governmental failures. From 2004 to the present, the

government has had the benefit of The 9/11 Commission Report to gauge the need for policy and

legal changes to improve the government's ability to interdict a September 11-style attack. In this

section of Module 2, we will review the findings and recommendations of The 9/11 Commission

Report as they relate to homeland security strategy and to legislative and executive policy.

9/11 Commission Findings: Government-wide Failures

The 9/11 Commission reported government-wide failures and grouped these failures into four

broad categories: imagination, policy, capability, and management. We will briefly explore all of

these areas and discuss their implications for future homeland security policy. The full findings

of the report describe additional specific findings, but these four broad categories of failure set

the stage for understanding the development of homeland security policy created following the

release of The 9/11 Commission Report.

Imagination

The report identifies imagination as the most important failure. In explaining this failure, the

commission concedes that "imagination is not a gift usually associated with bureaucracies"

(National Commission, p. 344). This failure is centered on the inability to recognize the scope of

the threat posed by terrorism and al-Qaeda. The media and citizens were not concerned about

terrorism, and it had not appeared to be an issue during the 2000 presidential campaigns.

According to the 9/11 Commission, the failure of the government and its intelligence institutions

to conceive the threat constitutes a failure of imagination.

Policy

The failure of policy is directed at the ineffective actions taken against al-Qaeda following the

1998 East African embassy bombings, the 1999 bombing plots against Americans in Jordan, the

capture of Ahmed Ressam before his planned attack at Los Angeles International Airport, and

the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole. The problem in dealing with the al-Qaeda phenomenon lay

in the fact that there were essentially two methods in the American arsenal for dealing with these

types of threats: criminal trial and war. The problem is described in the report as stemming from

the fact that the terrorist attacks "were committed by a loose, far-flung, nebulous conspiracy with

no territories or citizens or assets that could be readily threatened, overwhelmed, or destroyed"

(National Commission, p. 348). Countering the threat from al-Qaeda required a different method

—one the United States could not handle. The limited responses to attacks against America left

the enemy emboldened. An invasion into the al-Qaeda sanctuary in Afghanistan was not

considered. The report contends:

The United States had warned the Taliban that they would be held accountable for further attacks

by Bin Ladin against Afghanistan's US interests. The warning had been given in 1998, again in

late 1999, once more in the fall of 2000, and again in the summer of 2001. Delivering it

repeatedly did not make it more effective (National Commission, p. 350).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

The policy response by the United States to the attacks of al-Qaeda clearly failed to deter further

terrorist activity.

Capability

International

The menu of options available to handle the problem posed by al-Qaeda was the same list of

cold-war options used for decades. These options were ineffective against a new enemy. The

report advises that CIA was not eager to conduct paramilitary operations and thought these types

of operations more appropriate for the military. The CIA also needed to increase its ability to

gather intelligence from human intelligence sources. The report asserts, "At no point before

September 11 was the Department of Defense fully engaged in the mission of countering al

Qaeda" (National Commission, p. 351). The report also states that the North American

Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was not prepared for the threat of domestic aircraft

hijacking, as it focused its attention outside our borders.

Domestic

The most glaring deficiencies were identified at home. The FBI had little capability to capture

and utilize knowledge gained in the field by its agents. Compounding the problem was the fact

that for terrorism-related concerns, other law enforcement agencies deferred to the FBI. The

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) also failed to recognize many of its vulnerabilities, such

as inadequate no-fly lists, lack of cockpit door security, and inadequate procedures for

identifying and barring passengers who posed security risks.

Management

The report identifies many ways the September 11 attacks could have been prevented, had

information and operations been better managed across the intelligence community. The most

notable was the lack of coordination in the intelligence community and the failure of the IC to

notify domestic agencies of the identity of two al-Qaeda operatives who ended up participating

in the September 11 attacks. This failure was representative of the overall lack of system

planning for joint operations present in the pre-September 11 IC. These failures were indicative

of a larger management problem and an example of the CIA's lack of a comprehensive strategy

for terrorism intelligence. Also problematic was the distancing of the FBI from the IC, which

resulted in a failure to give proper consideration to domestic intelligence for a full-spectrum

threat assessment of terrorism.

9/11 Commission: Recommendations

The 9/11 Commission Report made 41 recommendations for change in the conclusions of its

report. The suggested changes address a broad spectrum of issues. The domestic preparedness

recommendations seek to increase the capability of first responders, increase transportation

security, and improve border security. Recommendations for reforms to government institutions

include broad changes to the structure of the IC, checks on executive power as it relates to civil

liberties, and changes in Congressional structure and oversight as it relates to homeland security

terrorist activity.

Capability

International

The menu of options available to handle the problem posed by al-Qaeda was the same list of

cold-war options used for decades. These options were ineffective against a new enemy. The

report advises that CIA was not eager to conduct paramilitary operations and thought these types

of operations more appropriate for the military. The CIA also needed to increase its ability to

gather intelligence from human intelligence sources. The report asserts, "At no point before

September 11 was the Department of Defense fully engaged in the mission of countering al

Qaeda" (National Commission, p. 351). The report also states that the North American

Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was not prepared for the threat of domestic aircraft

hijacking, as it focused its attention outside our borders.

Domestic

The most glaring deficiencies were identified at home. The FBI had little capability to capture

and utilize knowledge gained in the field by its agents. Compounding the problem was the fact

that for terrorism-related concerns, other law enforcement agencies deferred to the FBI. The

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) also failed to recognize many of its vulnerabilities, such

as inadequate no-fly lists, lack of cockpit door security, and inadequate procedures for

identifying and barring passengers who posed security risks.

Management

The report identifies many ways the September 11 attacks could have been prevented, had

information and operations been better managed across the intelligence community. The most

notable was the lack of coordination in the intelligence community and the failure of the IC to

notify domestic agencies of the identity of two al-Qaeda operatives who ended up participating

in the September 11 attacks. This failure was representative of the overall lack of system

planning for joint operations present in the pre-September 11 IC. These failures were indicative

of a larger management problem and an example of the CIA's lack of a comprehensive strategy

for terrorism intelligence. Also problematic was the distancing of the FBI from the IC, which

resulted in a failure to give proper consideration to domestic intelligence for a full-spectrum

threat assessment of terrorism.

9/11 Commission: Recommendations

The 9/11 Commission Report made 41 recommendations for change in the conclusions of its

report. The suggested changes address a broad spectrum of issues. The domestic preparedness

recommendations seek to increase the capability of first responders, increase transportation

security, and improve border security. Recommendations for reforms to government institutions

include broad changes to the structure of the IC, checks on executive power as it relates to civil

liberties, and changes in Congressional structure and oversight as it relates to homeland security

and the IC. In the foreign policy realm the Commission makes recommendations on diplomacy

and foreign policy in the Middle East and worldwide nonproliferation efforts. The

recommendations of the Commission serve to influence the formulation of homeland security

policy in the period following its release in July 2004.

Return to top of page

3. Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2004 to the Present

Major Legislative and Executive Actions Since 2004

The July 2004 release of the 9/11 Commission Report had a profound impact on homeland

security policy. The initiatives that have been authorized through the use of legislative and

executive power since then directly address many of the findings and recommendations outlined

by the report. Although many of the 9/11 Commission recommendations have been incorporated

into policy during the period, others have not. The yet-unimplemented recommendations

continue to be a source of political contention.

The legislative and executive actions that have been taken since the release of The 9/11

Commission Report are summarized in this module's interactive timeline, which you will find in

its own tab at the top of this screen. Click again on the Timeline tab to see an interactive timeline

that summarizes the legislative and executive responses that occurred subsequent to the release

of The 9/11 Commission Report.

Focus on Legislation

The Intelligence Community and the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (IRTPA)

intelligence: 1. the product resulting from the collection, processing, integration, analysis,

evaluation, and interpretation of available information concerning foreign countries or areas; 2.

information and knowledge about an adversary obtained through observation, investigation,

analysis, or understanding

—US DoD, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms

The IRTPA was signed into law on December 17, 2004 (IRTPA). It included many of the

report's suggested changes to intelligence, transportation security, border protection,

immigration, terrorist money laundering, and several first responder preparedness issues. The

greatest changes required by the law were to the US IC.

The government agencies that make up the intelligence community are as follows (US

Intelligence Community website, n.d.):

Air Force Intelligence

Department of the Treasury

and foreign policy in the Middle East and worldwide nonproliferation efforts. The

recommendations of the Commission serve to influence the formulation of homeland security

policy in the period following its release in July 2004.

Return to top of page

3. Homeland Security Strategy and Policy, 2004 to the Present

Major Legislative and Executive Actions Since 2004

The July 2004 release of the 9/11 Commission Report had a profound impact on homeland

security policy. The initiatives that have been authorized through the use of legislative and

executive power since then directly address many of the findings and recommendations outlined

by the report. Although many of the 9/11 Commission recommendations have been incorporated

into policy during the period, others have not. The yet-unimplemented recommendations

continue to be a source of political contention.

The legislative and executive actions that have been taken since the release of The 9/11

Commission Report are summarized in this module's interactive timeline, which you will find in

its own tab at the top of this screen. Click again on the Timeline tab to see an interactive timeline

that summarizes the legislative and executive responses that occurred subsequent to the release

of The 9/11 Commission Report.

Focus on Legislation

The Intelligence Community and the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (IRTPA)

intelligence: 1. the product resulting from the collection, processing, integration, analysis,

evaluation, and interpretation of available information concerning foreign countries or areas; 2.

information and knowledge about an adversary obtained through observation, investigation,

analysis, or understanding

—US DoD, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms

The IRTPA was signed into law on December 17, 2004 (IRTPA). It included many of the

report's suggested changes to intelligence, transportation security, border protection,

immigration, terrorist money laundering, and several first responder preparedness issues. The

greatest changes required by the law were to the US IC.

The government agencies that make up the intelligence community are as follows (US

Intelligence Community website, n.d.):

Air Force Intelligence

Department of the Treasury

Army Intelligence

Drug Enforcement Administration

Central Intelligence Agency

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Coast Guard Intelligence

Marine Corps Intelligence

Defense Intelligence Agency

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

Department of Energy

National Reconnaissance Office

Department of Homeland Security

National Security Agency

Department of State

Navy Intelligence

The IRTPA made legal changes to implement many of the recommendations of the 9/11

Commission related to the operation and administration of the IC. The most critical change

created a new position—Director of National Intelligence (DNI)—in an effort to create

management oversight and accountability in the IC. Previously, the IC had been led by the

Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) who also served as the head of the Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA). The DCI did not have strong authority over the other elements of the IC. The

IRTPA created the Office of the DNI as an independent authority over the 16 members of the IC.

Under the IRTPA, the DNI is an independent office that is not to be included as a part of any one

agency of the IC, though today the intelligence community considers the ODNI as part of the

coalition of 17 agencies and organizations.

The DNI, who is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, is granted certain

powers under the IRTPA. As with most other executive appointments, the DNI serves at the

pleasure of the president. The DNI is the principal advisor to the president of the United States,

the National Security Council, and the Homeland Security Council with regard to intelligence

issues relating to homeland and national security. The DNI is authorized to direct the budget and

implementation of a National Intelligence Program. The IRTPA (§ 1012) defines national

intelligence as

information gathered within or outside the United States, that—

(A) pertains, as determined consistent with any guidance issued by the president, to more than

one United States Government agency; and

(B) that involves—

(i) threats to the United States, its people, property, or interests;

(ii) the development, proliferation, or use of weapons of mass destruction; or

(iii) any other matter bearing on United States national or homeland security.

The National Intelligence Program includes all intelligence collection except that which is in

direct support of ongoing military operations by military intelligence. The creation of the

position of DNI consolidated authority and management responsibility into one office, thereby

addressing many of the concerns raised by the 9/11 Commission concerning accountability and

Drug Enforcement Administration

Central Intelligence Agency

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Coast Guard Intelligence

Marine Corps Intelligence

Defense Intelligence Agency

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

Department of Energy

National Reconnaissance Office

Department of Homeland Security

National Security Agency

Department of State

Navy Intelligence

The IRTPA made legal changes to implement many of the recommendations of the 9/11

Commission related to the operation and administration of the IC. The most critical change

created a new position—Director of National Intelligence (DNI)—in an effort to create

management oversight and accountability in the IC. Previously, the IC had been led by the

Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) who also served as the head of the Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA). The DCI did not have strong authority over the other elements of the IC. The

IRTPA created the Office of the DNI as an independent authority over the 16 members of the IC.

Under the IRTPA, the DNI is an independent office that is not to be included as a part of any one

agency of the IC, though today the intelligence community considers the ODNI as part of the

coalition of 17 agencies and organizations.

The DNI, who is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, is granted certain

powers under the IRTPA. As with most other executive appointments, the DNI serves at the

pleasure of the president. The DNI is the principal advisor to the president of the United States,

the National Security Council, and the Homeland Security Council with regard to intelligence

issues relating to homeland and national security. The DNI is authorized to direct the budget and

implementation of a National Intelligence Program. The IRTPA (§ 1012) defines national

intelligence as

information gathered within or outside the United States, that—

(A) pertains, as determined consistent with any guidance issued by the president, to more than

one United States Government agency; and

(B) that involves—

(i) threats to the United States, its people, property, or interests;

(ii) the development, proliferation, or use of weapons of mass destruction; or

(iii) any other matter bearing on United States national or homeland security.

The National Intelligence Program includes all intelligence collection except that which is in

direct support of ongoing military operations by military intelligence. The creation of the

position of DNI consolidated authority and management responsibility into one office, thereby

addressing many of the concerns raised by the 9/11 Commission concerning accountability and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

oversight in the IC. Some scholars argue that the establishment of the DNI position is an

improvement, but that the DNI should have been given more power over the individual agencies

within the IC.

In addition to the creation of the DNI, the IRTPA made other changes aimed at improving the

ability of the IC to better counter the threat of terrorism. The IRTPA also legally authorized the

creation of a National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). The 9/11 Commission Report specified

the creation of an NCTC as a necessary improvement to the IC. The NCTC was originally

authorized by the president through EO 13354, National Counterterrorism Center, on August 27,

2004; Congress authorized it by law with the passage of the IRTPA in December 2004. The

NCTC serves "as the primary organization in the United States Government for integrating and

analyzing all intelligence pertaining to terrorism possessed or acquired by the United States

Government" (NCTC, n.d.). The NCTC also serves as "the primary organization for strategic

operational planning for counterterrorism" (NCTC, n.d.).

Several other provisions related to intelligence were included in the IRTPA. The act also

required the development of an information-sharing environment within the IC, created an

intelligence-focused workforce within the FBI, mandated the creation of a Privacy and Civil

Rights Oversight Board, required the development of uniform security clearance standards, and

the creation of additional coordinating entities within the IC. The IRTPA legislatively addressed

many of the 9/11 Commission's recommendations. However, these changes still require proper

implementation to be effective. It is the implementation and effectuation of these new programs,

directives, and structures that has drawn criticism from many groups, including the 9/11

Commission members, who formed the now-defunct 9/11 Public Discourse Project to bring

attention to the unimplemented recommendations of the commission.

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act

Following the devastating effects and government-wide failures that were made apparent in the

response to Hurricane Katrina in September 2005, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency

Management Reform Act, which made several changes to the Homeland Security Act of 2002

and resulted in a reorganization of the DHS. Several reports on the event issued by the White

House, the US Senate, and the US House of Representatives highlighted the need for change.

Central to the changes required by the act was the reemergence of the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA). The organization of the DHS under the Homeland Security Act

of 2002 placed FEMA in the Preparedness Directorate, reporting to the undersecretary for

preparedness. Prior to the creation of DHS, FEMA had been an independent agency, with a

director who reported to the president of the United States. The Post-Katrina Emergency

Management Reform Act restored to FEMA several functions that were stripped from it with the

creation of DHS.

improvement, but that the DNI should have been given more power over the individual agencies

within the IC.

In addition to the creation of the DNI, the IRTPA made other changes aimed at improving the

ability of the IC to better counter the threat of terrorism. The IRTPA also legally authorized the

creation of a National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). The 9/11 Commission Report specified

the creation of an NCTC as a necessary improvement to the IC. The NCTC was originally

authorized by the president through EO 13354, National Counterterrorism Center, on August 27,

2004; Congress authorized it by law with the passage of the IRTPA in December 2004. The

NCTC serves "as the primary organization in the United States Government for integrating and

analyzing all intelligence pertaining to terrorism possessed or acquired by the United States

Government" (NCTC, n.d.). The NCTC also serves as "the primary organization for strategic

operational planning for counterterrorism" (NCTC, n.d.).

Several other provisions related to intelligence were included in the IRTPA. The act also

required the development of an information-sharing environment within the IC, created an

intelligence-focused workforce within the FBI, mandated the creation of a Privacy and Civil

Rights Oversight Board, required the development of uniform security clearance standards, and

the creation of additional coordinating entities within the IC. The IRTPA legislatively addressed

many of the 9/11 Commission's recommendations. However, these changes still require proper

implementation to be effective. It is the implementation and effectuation of these new programs,

directives, and structures that has drawn criticism from many groups, including the 9/11

Commission members, who formed the now-defunct 9/11 Public Discourse Project to bring

attention to the unimplemented recommendations of the commission.

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act

Following the devastating effects and government-wide failures that were made apparent in the

response to Hurricane Katrina in September 2005, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency

Management Reform Act, which made several changes to the Homeland Security Act of 2002

and resulted in a reorganization of the DHS. Several reports on the event issued by the White

House, the US Senate, and the US House of Representatives highlighted the need for change.

Central to the changes required by the act was the reemergence of the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA). The organization of the DHS under the Homeland Security Act

of 2002 placed FEMA in the Preparedness Directorate, reporting to the undersecretary for

preparedness. Prior to the creation of DHS, FEMA had been an independent agency, with a

director who reported to the president of the United States. The Post-Katrina Emergency

Management Reform Act restored to FEMA several functions that were stripped from it with the

creation of DHS.

Figure 2.2

The Effects of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, September 2005

Source: FEMA Photo Library, "Louisiana Hurricane Katrina Photographs"

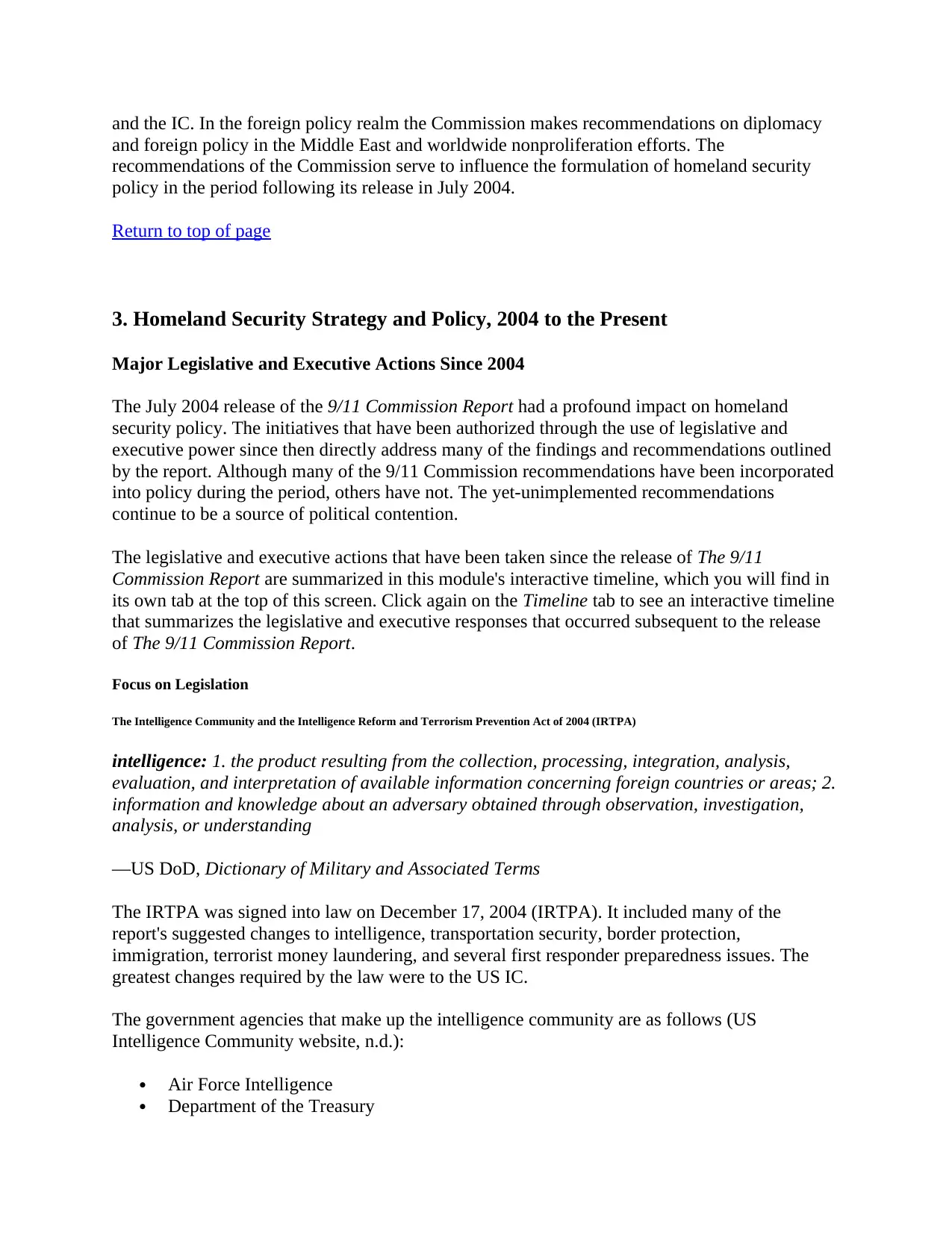

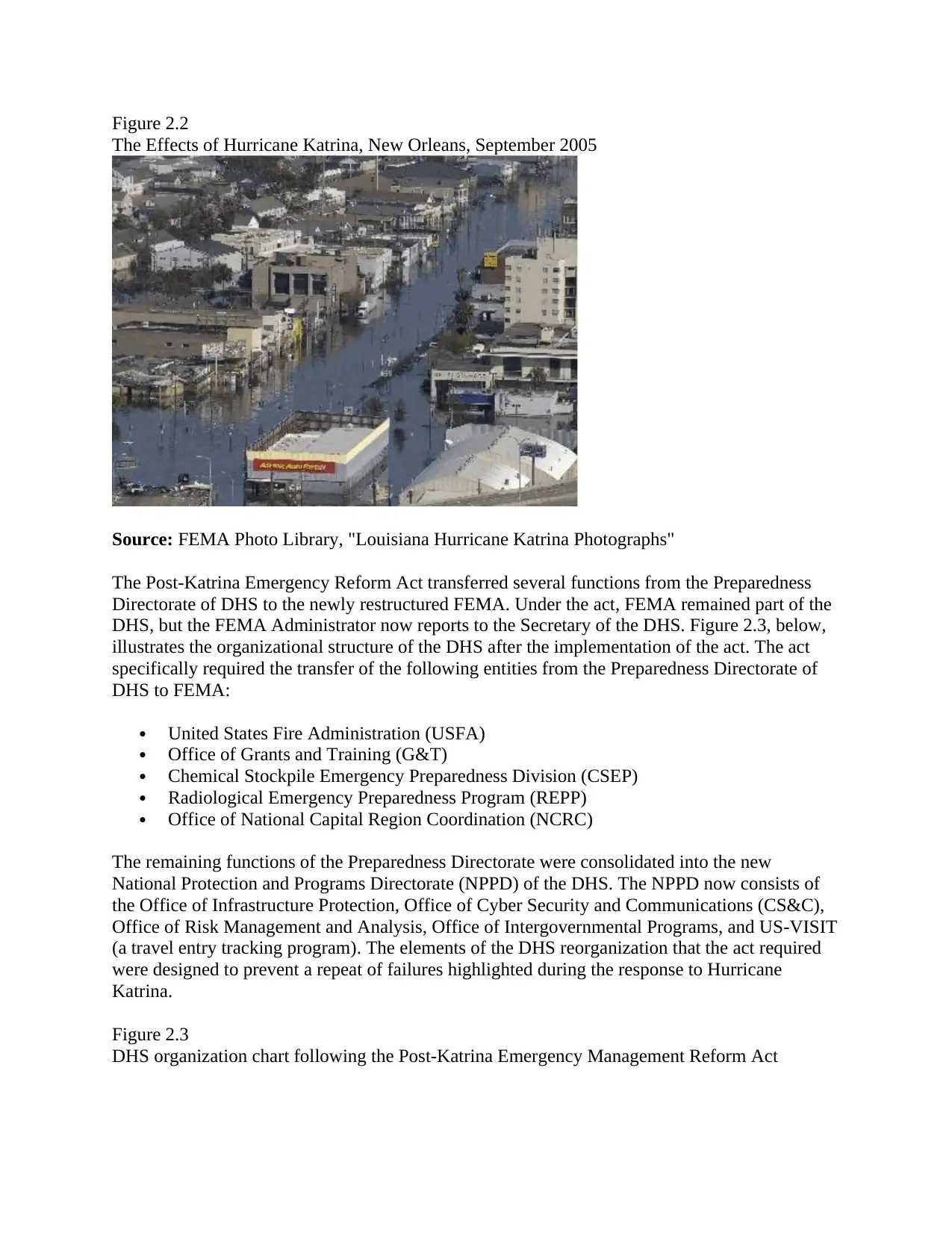

The Post-Katrina Emergency Reform Act transferred several functions from the Preparedness

Directorate of DHS to the newly restructured FEMA. Under the act, FEMA remained part of the

DHS, but the FEMA Administrator now reports to the Secretary of the DHS. Figure 2.3, below,

illustrates the organizational structure of the DHS after the implementation of the act. The act

specifically required the transfer of the following entities from the Preparedness Directorate of

DHS to FEMA:

United States Fire Administration (USFA)

Office of Grants and Training (G&T)

Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Division (CSEP)

Radiological Emergency Preparedness Program (REPP)

Office of National Capital Region Coordination (NCRC)

The remaining functions of the Preparedness Directorate were consolidated into the new

National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) of the DHS. The NPPD now consists of

the Office of Infrastructure Protection, Office of Cyber Security and Communications (CS&C),

Office of Risk Management and Analysis, Office of Intergovernmental Programs, and US-VISIT

(a travel entry tracking program). The elements of the DHS reorganization that the act required

were designed to prevent a repeat of failures highlighted during the response to Hurricane

Katrina.

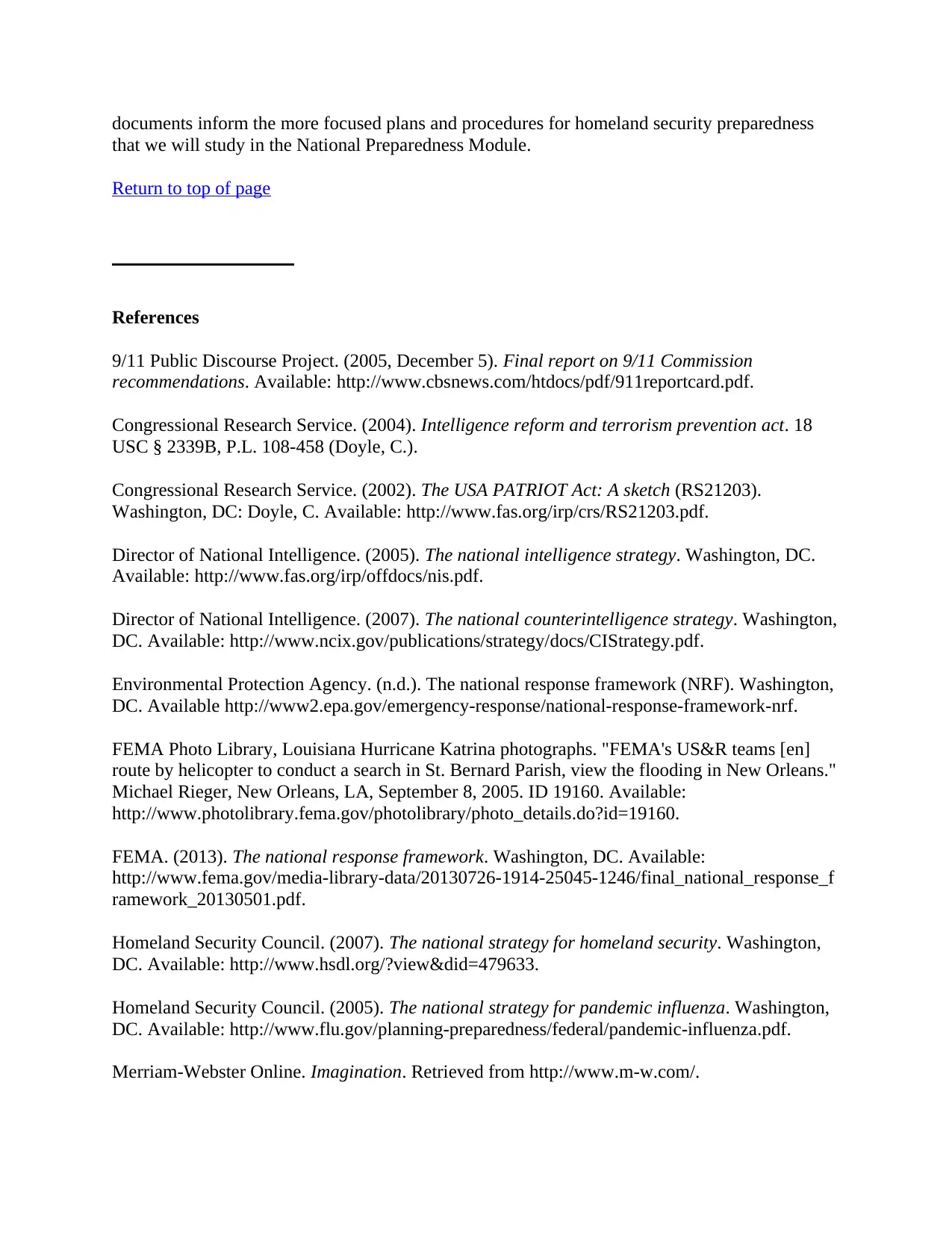

Figure 2.3

DHS organization chart following the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act

The Effects of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, September 2005

Source: FEMA Photo Library, "Louisiana Hurricane Katrina Photographs"

The Post-Katrina Emergency Reform Act transferred several functions from the Preparedness

Directorate of DHS to the newly restructured FEMA. Under the act, FEMA remained part of the

DHS, but the FEMA Administrator now reports to the Secretary of the DHS. Figure 2.3, below,

illustrates the organizational structure of the DHS after the implementation of the act. The act

specifically required the transfer of the following entities from the Preparedness Directorate of

DHS to FEMA:

United States Fire Administration (USFA)

Office of Grants and Training (G&T)

Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Division (CSEP)

Radiological Emergency Preparedness Program (REPP)

Office of National Capital Region Coordination (NCRC)

The remaining functions of the Preparedness Directorate were consolidated into the new

National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) of the DHS. The NPPD now consists of

the Office of Infrastructure Protection, Office of Cyber Security and Communications (CS&C),

Office of Risk Management and Analysis, Office of Intergovernmental Programs, and US-VISIT

(a travel entry tracking program). The elements of the DHS reorganization that the act required

were designed to prevent a repeat of failures highlighted during the response to Hurricane

Katrina.

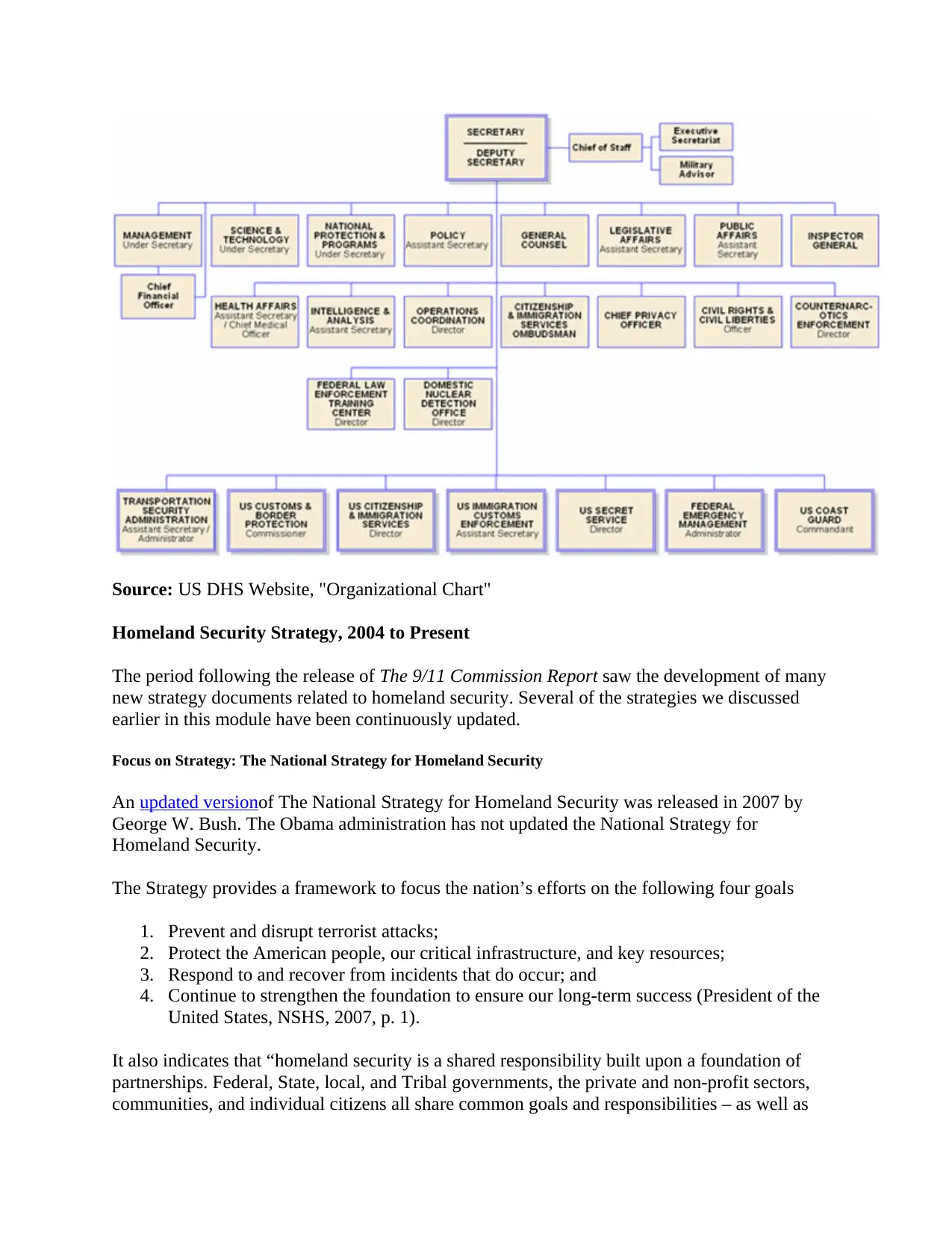

Figure 2.3

DHS organization chart following the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act

Source: US DHS Website, "Organizational Chart"

Homeland Security Strategy, 2004 to Present

The period following the release of The 9/11 Commission Report saw the development of many

new strategy documents related to homeland security. Several of the strategies we discussed

earlier in this module have been continuously updated.

Focus on Strategy: The National Strategy for Homeland Security

An updated versionof The National Strategy for Homeland Security was released in 2007 by

George W. Bush. The Obama administration has not updated the National Strategy for

Homeland Security.