Customer Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty & Retention in Tourism

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|12

|11999

|170

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines the integration of Muslim Customer Perceived Value (MCPV) within the tourism industry, focusing on its impact on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and retention. It identifies MCPV dimensions and develops a conceptual model to test the relationships between MCPV and key consumer behaviors using data from 221 Muslim tourists. The study employs exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, along with structural equation modeling, to validate measures and test hypotheses. The findings suggest that incorporating Islamic attributes alongside conventional value dimensions is crucial for satisfying Muslim tourists and achieving customer retention, highlighting the importance of Shari'ah-compliant attributes in tourism offerings.

Integrating Muslim Customer Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty and

Retention in the Tourism Industry: An empirical study

RIYAD EID*

Faculty of Commerce, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt and College of Business & Economics, United Arab Emirates Univers

ABSTRACT

In recent years, customer value has been the favorable theme for numerous tourism studies and reports. However, alth

up one of the largest tourist markets in the world,perceived value of tourism offering oriented toward this market has not been

defined. Furthermore, there is a lack of systematic empirical evidence regarding the effects of Muslim Customer Percei

on consumer satisfaction, customer loyalty and customer retention. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to identify t

to examine the interrelationships between MCPV, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and Muslim customer retentio

and test a conceptual model of the consequences of MCPV in the tourism industry. Moreover, 13 hypotheses were deve

using a sample of 221 Muslim tourists. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were used to test the validity of the

the structural equation modeling has been used in hypotheses testing. The strength of the relationship between the co

features of the suggested MCPV model are crucial to achieving Muslim customer retention in the tourism industry. Find

that the availability of the suggested Islamic attributes value, along with conventional value dimensions, could satisfy M

they buy a tourism package. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Received 18 February 2013; Revised 28 October 2013; Accepted 5 November 2013

key words customer value; Muslim; tourism and hospitality; customer loyalty; customer retention; customer satisfact

INTRODUCTION

Despite a long-term interest in the understanding of consumer

value,its relationship with customersatisfaction,customer

loyalty and eventually customer retention to a service firm is

still unclear. Customer value is central to management think-

ing, especially for high-performing organizations, which strive

to satisfy customers at all times. According to Eid (2007), cus-

tomer value is becoming a priority because of very powerful

economic, technological and social forces that have effectively

made the traditional business models irrelevant in the contem-

porary business and technological environment. According to

Choi and Chu (2001), to be successful in the hospitality and

tourism industry,companies must provide superior customer

value, and this must be carried out in a continuous and efficient

way.Furthermore,tourism companiesshould improve the

quality of their services offerings and ensure thatthe needs

and expectations of their customers are being met.

Meanwhile,there are new trends and developments such

as the investmentand adoption of business practices based

on the Islamic principles ofShari’ah ‘Islamic law’(Essoo

& Dibb, 2004; Meng, Tepanon, & Uysal, 2008; Weidenfeld

& Ron, 2008; Stephenson, Russell, & Edgar, 2010;Zamani-

Farahani& Henderson,2010;Fakharyan,Jalilvand,Elyasi,

& Mohammadi,2012;Zamani-Farahani& Musa, 2012).

For example,Essoo and Dibb (2004)found thatreligion

influencestourism behavioramong Hindus,Muslimsand

Catholics. Weidenfeld and Ron (2008) also found that religion

influences the destination choice, tourist product favorite

selection of religious opportunities and facilities offered.

et al. (2008)found thattourists selectdestinations thatare

supposed to bestfulfill theirinternaldesiresor preferred

destination attributes.Finally,Zamani-Farahaniand Musa

(2012) explored the influence of Islamic religiosity (meas

on dimensions of ‘Islamic Belief’, ‘Islamic Practice’ and ‘Is

Piety’)on the perceived socio-culturalimpacts oftourism

among residents in two tourist areas in Iran.

However,although Muslims make up one of the largest

tourist markets in the world as Muslim population constit

an internationalmarketof 2.1 billion possible customers

(Muslim populationworldwide,2013) and marketing

scholars have long studied ‘perceived value’ and propose

variousconceptualizationsof the term (Holbrook,1994;

Petrick,2002; Benkenstein,Yavas,& Forberger,2003; Oh,

2003;Kwun, 2004;Gallarza& Saura, 2006;Sanchez,

Callarisa,Rodriguez,& Moliner, 2006; Nasution&

Mavondo,2008;Roig et al., 2009),perceived value of

tourism offering oriented toward this market and the con

quencesof creating Muslim CustomerPerceived Value

(MCPV) have not been clearly defined (Stephenson etal.,

2010; Zamani-Farahani& Henderson,2010; Laderlah,

Ab Rahman,Awang,& Man, 2011;Zamani-Farahani&

Musa, 2012;Fakharyan etal., 2012).Hence,full-scale

research conducted in amorerobustmannermustbe

undertaken.

Undoubtedly,although previous studies provide empirica

evidence of the existence of the cognitive and affective d

sions of perceived value (see, for example, Petrick, 2002

2003;Kwun, 2004;Gallarza & Saura,2006;Nasution &

Mavondo,2008;Sanchez,Roig etal., 2009),none of them

studies the overallperceived value ofa purchase from an

*Correspondence to:Dr. Riyad Eid,Associate Professorof Marketing,

Faculty ofCommerce,Tanta University,Tanta,Egyptand College of

Business & Economics, United Arab Emirates University, Al-Ain, UAE.

E-mail: riyad.aly@uaeu.ac.ae

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

International Journal of Tourism Research, Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

Published online 10 December 2013 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/jtr.1982

Retention in the Tourism Industry: An empirical study

RIYAD EID*

Faculty of Commerce, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt and College of Business & Economics, United Arab Emirates Univers

ABSTRACT

In recent years, customer value has been the favorable theme for numerous tourism studies and reports. However, alth

up one of the largest tourist markets in the world,perceived value of tourism offering oriented toward this market has not been

defined. Furthermore, there is a lack of systematic empirical evidence regarding the effects of Muslim Customer Percei

on consumer satisfaction, customer loyalty and customer retention. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to identify t

to examine the interrelationships between MCPV, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and Muslim customer retentio

and test a conceptual model of the consequences of MCPV in the tourism industry. Moreover, 13 hypotheses were deve

using a sample of 221 Muslim tourists. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were used to test the validity of the

the structural equation modeling has been used in hypotheses testing. The strength of the relationship between the co

features of the suggested MCPV model are crucial to achieving Muslim customer retention in the tourism industry. Find

that the availability of the suggested Islamic attributes value, along with conventional value dimensions, could satisfy M

they buy a tourism package. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Received 18 February 2013; Revised 28 October 2013; Accepted 5 November 2013

key words customer value; Muslim; tourism and hospitality; customer loyalty; customer retention; customer satisfact

INTRODUCTION

Despite a long-term interest in the understanding of consumer

value,its relationship with customersatisfaction,customer

loyalty and eventually customer retention to a service firm is

still unclear. Customer value is central to management think-

ing, especially for high-performing organizations, which strive

to satisfy customers at all times. According to Eid (2007), cus-

tomer value is becoming a priority because of very powerful

economic, technological and social forces that have effectively

made the traditional business models irrelevant in the contem-

porary business and technological environment. According to

Choi and Chu (2001), to be successful in the hospitality and

tourism industry,companies must provide superior customer

value, and this must be carried out in a continuous and efficient

way.Furthermore,tourism companiesshould improve the

quality of their services offerings and ensure thatthe needs

and expectations of their customers are being met.

Meanwhile,there are new trends and developments such

as the investmentand adoption of business practices based

on the Islamic principles ofShari’ah ‘Islamic law’(Essoo

& Dibb, 2004; Meng, Tepanon, & Uysal, 2008; Weidenfeld

& Ron, 2008; Stephenson, Russell, & Edgar, 2010;Zamani-

Farahani& Henderson,2010;Fakharyan,Jalilvand,Elyasi,

& Mohammadi,2012;Zamani-Farahani& Musa, 2012).

For example,Essoo and Dibb (2004)found thatreligion

influencestourism behavioramong Hindus,Muslimsand

Catholics. Weidenfeld and Ron (2008) also found that religion

influences the destination choice, tourist product favorite

selection of religious opportunities and facilities offered.

et al. (2008)found thattourists selectdestinations thatare

supposed to bestfulfill theirinternaldesiresor preferred

destination attributes.Finally,Zamani-Farahaniand Musa

(2012) explored the influence of Islamic religiosity (meas

on dimensions of ‘Islamic Belief’, ‘Islamic Practice’ and ‘Is

Piety’)on the perceived socio-culturalimpacts oftourism

among residents in two tourist areas in Iran.

However,although Muslims make up one of the largest

tourist markets in the world as Muslim population constit

an internationalmarketof 2.1 billion possible customers

(Muslim populationworldwide,2013) and marketing

scholars have long studied ‘perceived value’ and propose

variousconceptualizationsof the term (Holbrook,1994;

Petrick,2002; Benkenstein,Yavas,& Forberger,2003; Oh,

2003;Kwun, 2004;Gallarza& Saura, 2006;Sanchez,

Callarisa,Rodriguez,& Moliner, 2006; Nasution&

Mavondo,2008;Roig et al., 2009),perceived value of

tourism offering oriented toward this market and the con

quencesof creating Muslim CustomerPerceived Value

(MCPV) have not been clearly defined (Stephenson etal.,

2010; Zamani-Farahani& Henderson,2010; Laderlah,

Ab Rahman,Awang,& Man, 2011;Zamani-Farahani&

Musa, 2012;Fakharyan etal., 2012).Hence,full-scale

research conducted in amorerobustmannermustbe

undertaken.

Undoubtedly,although previous studies provide empirica

evidence of the existence of the cognitive and affective d

sions of perceived value (see, for example, Petrick, 2002

2003;Kwun, 2004;Gallarza & Saura,2006;Nasution &

Mavondo,2008;Sanchez,Roig etal., 2009),none of them

studies the overallperceived value ofa purchase from an

*Correspondence to:Dr. Riyad Eid,Associate Professorof Marketing,

Faculty ofCommerce,Tanta University,Tanta,Egyptand College of

Business & Economics, United Arab Emirates University, Al-Ain, UAE.

E-mail: riyad.aly@uaeu.ac.ae

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

International Journal of Tourism Research, Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

Published online 10 December 2013 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/jtr.1982

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Islamic perspective. Evaluation of the value of tourism products

in the case of Islamic tourism participation entails a completely

differentprocess because of the requirements of the Islamic

Shari’ah. Participation of Muslims in tourism activities requires

acceptable goods,services and environments.Therefore,any

attempt to design a scale of measurement of the overall MCPV

of a purchase, or to identify its dimensions, must not only reflect

a structure thatidentifies functionaland affective dimensions

but also the Shari’ah-Compliant attributes.

Therefore,the purposes ofthis research are to identify

MCPV dimensions and develop items ofmeasuring these

dimensions,to develop and clarify aconceptualmodel

integrating MCPV,customersatisfaction,customerloyalty

and their consequences on customer retention and to specify

and test hypothesized relationships derived from the concep-

tual framework. In the following sections, first, the develop-

mentof the conceptualmodeland the hypotheses ofthe

study are presented.Next,the methodology of the study is

discussed followed by the analysis and results. More specif-

ically,the conceptualmodelis tested using path analysis,

with the AMOS 19 structuralequation modeling package,

and data collected by mailsurvey of 221 Muslim tourists.

Finally, the conclusions and their implications are discussed.

LITERATURE REVIEW, CONCEPTUAL MODEL AND

HYPOTHESIZED RELATIONSHIPS

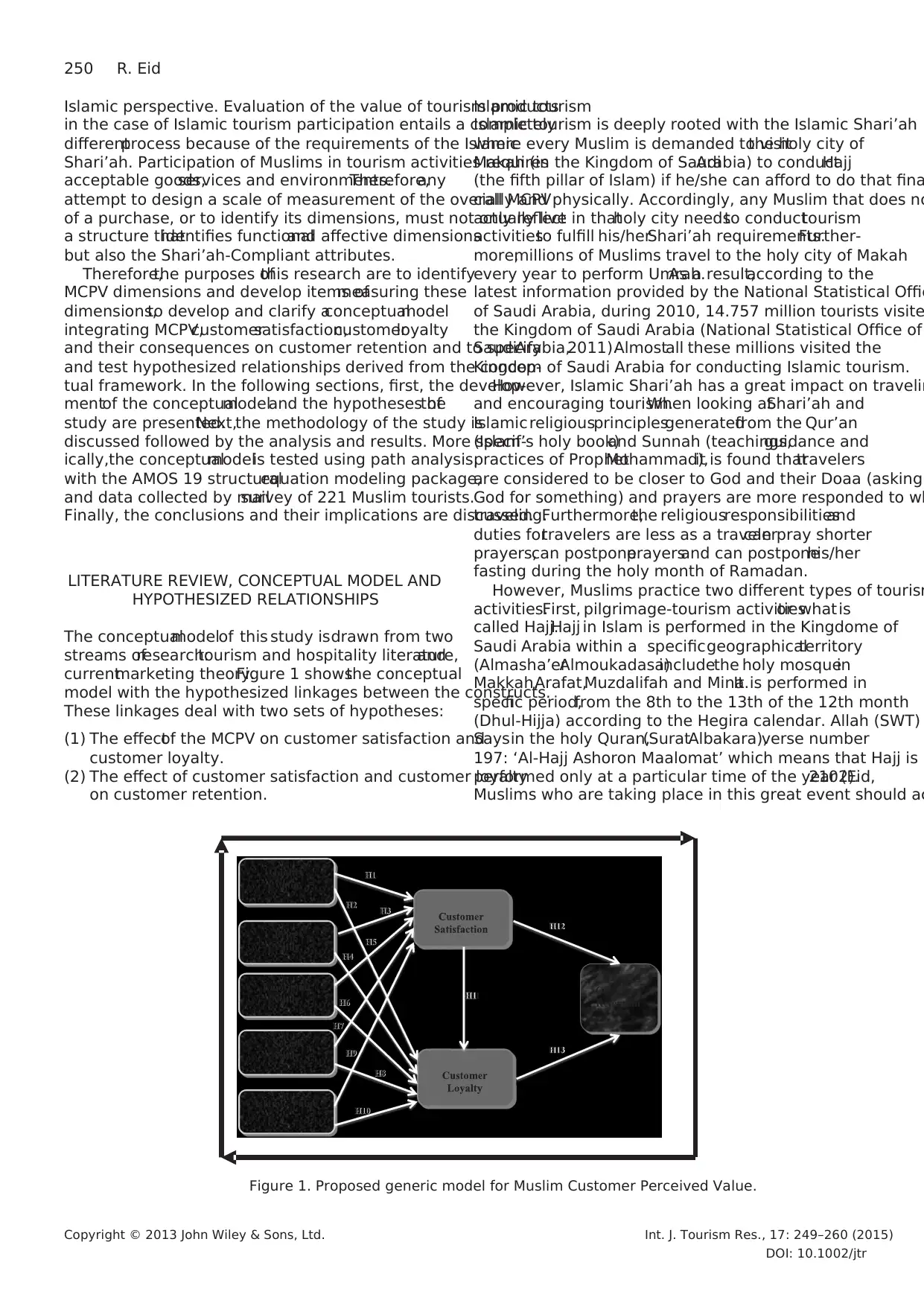

The conceptualmodelof this study isdrawn from two

streams ofresearch:tourism and hospitality literature,and

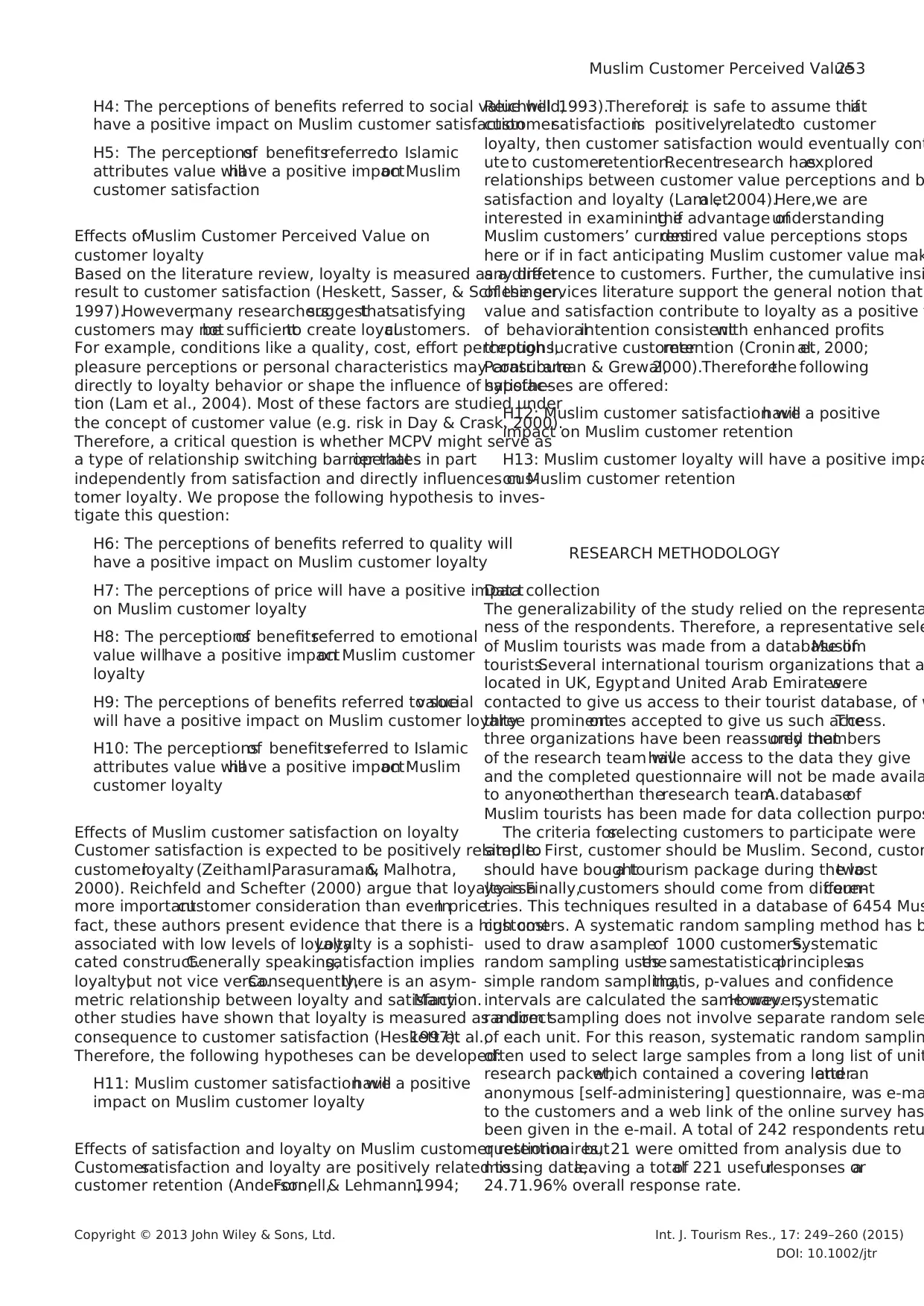

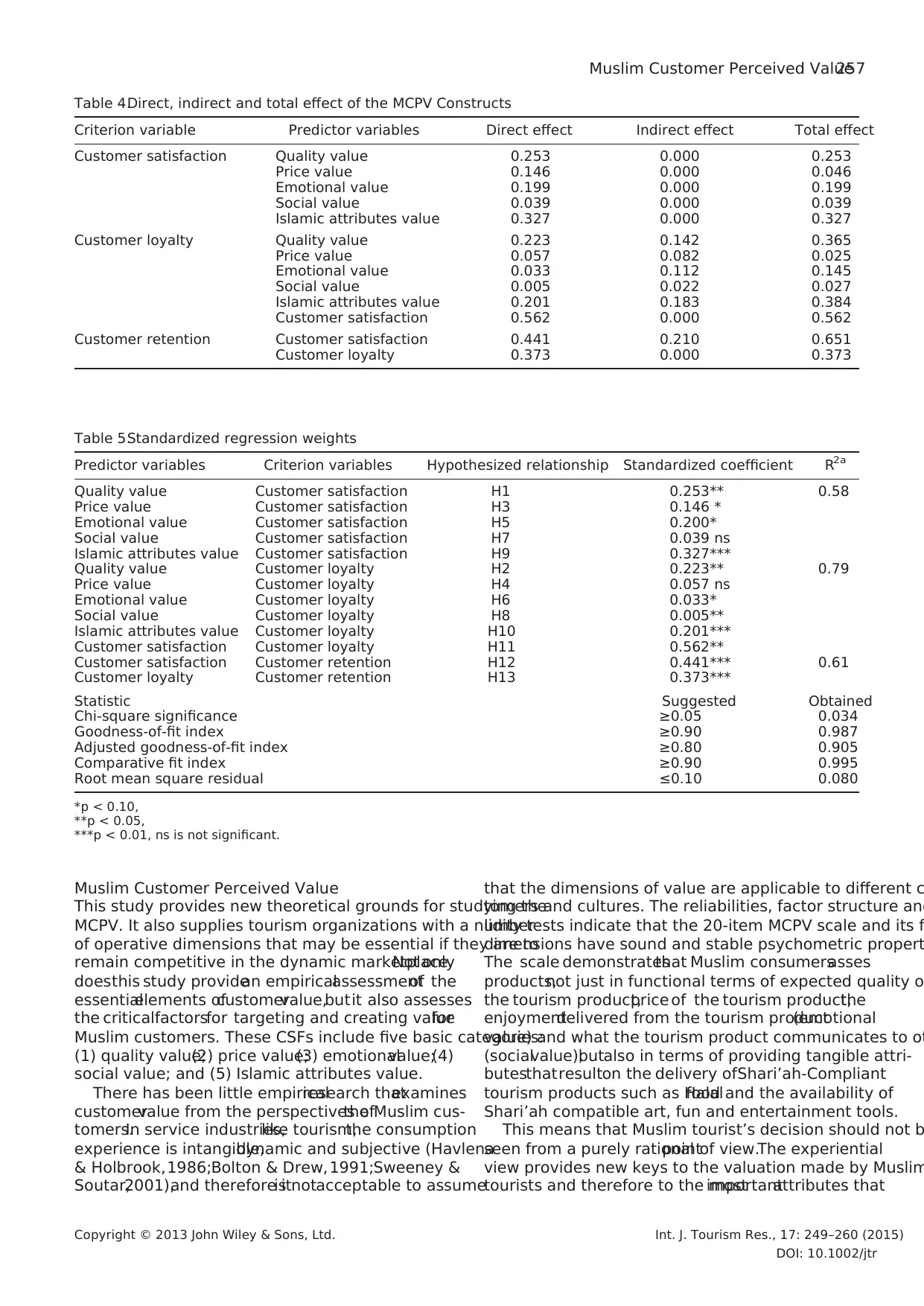

currentmarketing theory.Figure 1 showsthe conceptual

model with the hypothesized linkages between the constructs.

These linkages deal with two sets of hypotheses:

(1) The effectof the MCPV on customer satisfaction and

customer loyalty.

(2) The effect of customer satisfaction and customer loyalty

on customer retention.

Islamic tourism

Islamic tourism is deeply rooted with the Islamic Shari’ah

where every Muslim is demanded to visitthe holy city of

Makah (in the Kingdom of SaudiArabia) to conductHajj

(the fifth pillar of Islam) if he/she can afford to do that fina

cially and physically. Accordingly, any Muslim that does no

actually live in thatholy city needsto conducttourism

activitiesto fulfill his/herShari’ah requirements.Further-

more,millions of Muslims travel to the holy city of Makah

every year to perform Umrah.As a result,according to the

latest information provided by the National Statistical Offic

of Saudi Arabia, during 2010, 14.757 million tourists visite

the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (National Statistical Office of

SaudiArabia,2011).Almostall these millions visited the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for conducting Islamic tourism.

However, Islamic Shari’ah has a great impact on travelin

and encouraging tourism.When looking atShari’ah and

Islamic religiousprinciplesgeneratedfrom the Qur’an

(Islam’s holy book)and Sunnah (teachings,guidance and

practices of ProphetMohammad),it is found thattravelers

are considered to be closer to God and their Doaa (asking

God for something) and prayers are more responded to wh

traveling.Furthermore,the religiousresponsibilitiesand

duties fortravelers are less as a travelercan pray shorter

prayers,can postponeprayersand can postponehis/her

fasting during the holy month of Ramadan.

However, Muslims practice two different types of tourism

activities.First, pilgrimage-tourism activitiesor whatis

called Hajj.Hajj in Islam is performed in the Kingdome of

Saudi Arabia within a specificgeographicalterritory

(Almasha’erAlmoukadasa)includethe holy mosquein

Makkah,Arafat,Muzdalifah and Mina.It is performed in

specific period,from the 8th to the 13th of the 12th month

(Dhul-Hijja) according to the Hegira calendar. Allah (SWT)

Saysin the holy Quran,(SuratAlbakara),verse number

197: ‘Al-Hajj Ashoron Maalomat’ which means that Hajj is

performed only at a particular time of the year (Eid,2102).

Muslims who are taking place in this great event should ac

Figure 1. Proposed generic model for Muslim Customer Perceived Value.

250 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

in the case of Islamic tourism participation entails a completely

differentprocess because of the requirements of the Islamic

Shari’ah. Participation of Muslims in tourism activities requires

acceptable goods,services and environments.Therefore,any

attempt to design a scale of measurement of the overall MCPV

of a purchase, or to identify its dimensions, must not only reflect

a structure thatidentifies functionaland affective dimensions

but also the Shari’ah-Compliant attributes.

Therefore,the purposes ofthis research are to identify

MCPV dimensions and develop items ofmeasuring these

dimensions,to develop and clarify aconceptualmodel

integrating MCPV,customersatisfaction,customerloyalty

and their consequences on customer retention and to specify

and test hypothesized relationships derived from the concep-

tual framework. In the following sections, first, the develop-

mentof the conceptualmodeland the hypotheses ofthe

study are presented.Next,the methodology of the study is

discussed followed by the analysis and results. More specif-

ically,the conceptualmodelis tested using path analysis,

with the AMOS 19 structuralequation modeling package,

and data collected by mailsurvey of 221 Muslim tourists.

Finally, the conclusions and their implications are discussed.

LITERATURE REVIEW, CONCEPTUAL MODEL AND

HYPOTHESIZED RELATIONSHIPS

The conceptualmodelof this study isdrawn from two

streams ofresearch:tourism and hospitality literature,and

currentmarketing theory.Figure 1 showsthe conceptual

model with the hypothesized linkages between the constructs.

These linkages deal with two sets of hypotheses:

(1) The effectof the MCPV on customer satisfaction and

customer loyalty.

(2) The effect of customer satisfaction and customer loyalty

on customer retention.

Islamic tourism

Islamic tourism is deeply rooted with the Islamic Shari’ah

where every Muslim is demanded to visitthe holy city of

Makah (in the Kingdom of SaudiArabia) to conductHajj

(the fifth pillar of Islam) if he/she can afford to do that fina

cially and physically. Accordingly, any Muslim that does no

actually live in thatholy city needsto conducttourism

activitiesto fulfill his/herShari’ah requirements.Further-

more,millions of Muslims travel to the holy city of Makah

every year to perform Umrah.As a result,according to the

latest information provided by the National Statistical Offic

of Saudi Arabia, during 2010, 14.757 million tourists visite

the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (National Statistical Office of

SaudiArabia,2011).Almostall these millions visited the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for conducting Islamic tourism.

However, Islamic Shari’ah has a great impact on travelin

and encouraging tourism.When looking atShari’ah and

Islamic religiousprinciplesgeneratedfrom the Qur’an

(Islam’s holy book)and Sunnah (teachings,guidance and

practices of ProphetMohammad),it is found thattravelers

are considered to be closer to God and their Doaa (asking

God for something) and prayers are more responded to wh

traveling.Furthermore,the religiousresponsibilitiesand

duties fortravelers are less as a travelercan pray shorter

prayers,can postponeprayersand can postponehis/her

fasting during the holy month of Ramadan.

However, Muslims practice two different types of tourism

activities.First, pilgrimage-tourism activitiesor whatis

called Hajj.Hajj in Islam is performed in the Kingdome of

Saudi Arabia within a specificgeographicalterritory

(Almasha’erAlmoukadasa)includethe holy mosquein

Makkah,Arafat,Muzdalifah and Mina.It is performed in

specific period,from the 8th to the 13th of the 12th month

(Dhul-Hijja) according to the Hegira calendar. Allah (SWT)

Saysin the holy Quran,(SuratAlbakara),verse number

197: ‘Al-Hajj Ashoron Maalomat’ which means that Hajj is

performed only at a particular time of the year (Eid,2102).

Muslims who are taking place in this great event should ac

Figure 1. Proposed generic model for Muslim Customer Perceived Value.

250 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

in a good manner.Allah says in the holy Quran,chapter 2

(Surat Albakara),verse number 197: ‘If any one undertakes

that duty therein, Let there be no obscenity, nor wickedness,

nor wrangling in the Hajj’. It means that whoever decides to

go for Hajj should have good manners, so, there shouldn’t be

any immortality, sensuality or arguments in Hajj.

The second type of tourism activities that could be prac-

ticed by Muslims is called Islamic tourism,and this is the

core theme ofthis article.According to Jafariand Scott

(2013), Islamic tourism is essentially a new ‘touristic’ inter-

pretation ofpilgrimage thatmergesreligiousand leisure

tourism. Thus, it is ‘unlike mass tourism which for Muslims

is “characterized by hedonism,permissiveness,lavishness”’

(Sonmez,2001,p. 127).Islamic travelinstead is proposed

as an alternative to this hedonic conceptualization of tourism.

Muslims are encouraged to practice such type oftourism

activities for historical, social and cultural encounters, to gain

knowledge,to associate with others,to spread God’s word

and to enjoy and appreciate God’s creations (Timothy &

Olsen,2006).Undoubtedly,religious beliefs influence and

directMuslim adherentsto travelto particularsitesand

influencetheir attitudesand behavior,perceptionsand

perhaps emotions at those sites (Jafari & Scott, 2013). There-

fore, trends in forms of religious tourism may vary between

adherents of different faiths.

Customer perceived value

In recent years, customer perceived value has been the object

of interestby many researchers in hospitality and tourism

industry. Some studies treated perceived value as two crucial

dimensions of consumer behavior: the functional (value is for

instance linked to perceived prices through what is known as

transaction value)(see,for example,Grewal,Monroe,&

Krishnan, 1998; Cronin, Brady, & Hult, 2000;Oh, 2003).

Undoubtedly,hospitality and tourism activities need to

resortto fantasies,feelingsand emotionsto explain the

touristpurchasing decision.Many products have symbolic

meanings,beyond tangible attributes,perceived quality or

price (Havlena & Holbrook, 1986). Furthermore, as perceived

value is a subjective and dynamic construct that varies among

different customers and cultures at different times, it is neces-

sary to include subjective oremotionalreactionsthatare

generated in the consumer mind (Havlena & Holbrook, 1986;

Bolton & Drew,1991;Sweeney & Soutar,2001).Havlena

and Holbrook havedemonstrated theimportanceof the

affective componentin the experiences of buying and con-

suming in leisure,esthetic,creative and religious activities

(Havlena & Holbrook, 1986).

Therefore, many studies adopt a wider view that treats the

conceptof customer perceived value as a multidimensional

construct (See, for example, De Ruyter, Wetzels, Lemmink,

& Mattson,1997;De Ruyter,Wetzels,& Bloemer,1998;

Sweeney,Soutar,& Johnson, 1999;Rust, Zeithaml,&

Lemmon,2000; Sweeney & Soutar,2001).For example,

Sweeney et al. (1999) identifies five dimensions: social value

(acceptability), emotional value, functional value (price/value

for money),functionalvalue(performance/quality) and func-

tional value (versatility); Kwun (2004) considers brand, price

and risk as the precursors of the formation ofvalue in the

restaurantindustry;Benkenstein etal. (2003) conclude that

satisfaction with leisure services is a function ofcognitive

and emotional (psychological) factors; and Petrick (2002)

consists of five components: behavioral price, monetary

emotional response, quality and reputation.

However,although these studies provide empiricalevi-

dence of the existence of the cognitive and affective dim

sions ofperceived value,none ofthem studies the overall

perceived value of a purchase from an Islamic perspectiv

Evaluation ofthe value oftourism products in the case of

Islamic tourism participation entails a completely differen

process because of the requirements of the Islamic Shari

Participation of Muslims in tourism activities requires acc

able goods, services and environments. Therefore, any a

to design a scale of measurement of the overall MCPV of

purchase,or to identify its dimensions,must not only reflect

a structure that identifies functional and affective dimensions

but also the Shari’ah-Compliant attributes.

Islamic attributes value

Undoubtedly, religious identity appears to play an import

role in shaping consumption experiences including hospi

tality and tourism choices among Muslim customers.It is a

religious compulsion for allMuslims to consume products

that are permitted by Allah (God) and falls under the juris

tion of Shari’ah.In Islam, Shari’ah-Complianttourism

products generally refer to all such products that are in a

dance with the instructions ofAlmighty Allah (God)and

ProphetMohammad (may peace be upon him).Shari’ah

designates the term ‘Halal’ specifically to the products th

are permissible, lawful and are unobjectionable to consum

Shari’ah-Complianttourism productsmay thereforeadd

value to Muslim consumers’ shopping experiences throug

Islamic benefits that contribute to the value of the shopp

experience.

Shari’ah principles are requirements forevery Muslim,

and sensitivity toward application oftheseprinciplesis

important because religious deeds are not acceptable if t

are not conductedappropriately.A typical Muslim is

expected to do regular prayers in clean environments an

in Ramadan. In Islamic teachings, Muslims are also expec

to abstainfrom profligateconsumptionand indulgence

(Hashim,Murphy,& Hashim,2007).In addition,Shari’ah

principles prohibitadultery,gambling,consumption of pork

and other haram (forbidden) foods, selling or drinking liq

and dressing inappropriately (Zamani-Farahani & Hender

2010). Therefore, Shari’ah compliance should be a prereq

for high value tourism experiences for Muslims.

Based on the aforementioned discussions,two conclu-

sions can be introduced to help in building an effective sc

to measure MCPV. Firstly, the view of perceived value as

cognitive variable is notenough,because itis necessary to

incorporatethe affectivecomponent.Secondly,Muslim

touristevaluates notonly the traditionalaspects ofvalue

(cognitive and affective components) butalso the religious

identity related aspects that contribute to the value crea

This overall vision underlies the multidimensional approa

to MCPV.

Muslim Customer Perceived Value251

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

(Surat Albakara),verse number 197: ‘If any one undertakes

that duty therein, Let there be no obscenity, nor wickedness,

nor wrangling in the Hajj’. It means that whoever decides to

go for Hajj should have good manners, so, there shouldn’t be

any immortality, sensuality or arguments in Hajj.

The second type of tourism activities that could be prac-

ticed by Muslims is called Islamic tourism,and this is the

core theme ofthis article.According to Jafariand Scott

(2013), Islamic tourism is essentially a new ‘touristic’ inter-

pretation ofpilgrimage thatmergesreligiousand leisure

tourism. Thus, it is ‘unlike mass tourism which for Muslims

is “characterized by hedonism,permissiveness,lavishness”’

(Sonmez,2001,p. 127).Islamic travelinstead is proposed

as an alternative to this hedonic conceptualization of tourism.

Muslims are encouraged to practice such type oftourism

activities for historical, social and cultural encounters, to gain

knowledge,to associate with others,to spread God’s word

and to enjoy and appreciate God’s creations (Timothy &

Olsen,2006).Undoubtedly,religious beliefs influence and

directMuslim adherentsto travelto particularsitesand

influencetheir attitudesand behavior,perceptionsand

perhaps emotions at those sites (Jafari & Scott, 2013). There-

fore, trends in forms of religious tourism may vary between

adherents of different faiths.

Customer perceived value

In recent years, customer perceived value has been the object

of interestby many researchers in hospitality and tourism

industry. Some studies treated perceived value as two crucial

dimensions of consumer behavior: the functional (value is for

instance linked to perceived prices through what is known as

transaction value)(see,for example,Grewal,Monroe,&

Krishnan, 1998; Cronin, Brady, & Hult, 2000;Oh, 2003).

Undoubtedly,hospitality and tourism activities need to

resortto fantasies,feelingsand emotionsto explain the

touristpurchasing decision.Many products have symbolic

meanings,beyond tangible attributes,perceived quality or

price (Havlena & Holbrook, 1986). Furthermore, as perceived

value is a subjective and dynamic construct that varies among

different customers and cultures at different times, it is neces-

sary to include subjective oremotionalreactionsthatare

generated in the consumer mind (Havlena & Holbrook, 1986;

Bolton & Drew,1991;Sweeney & Soutar,2001).Havlena

and Holbrook havedemonstrated theimportanceof the

affective componentin the experiences of buying and con-

suming in leisure,esthetic,creative and religious activities

(Havlena & Holbrook, 1986).

Therefore, many studies adopt a wider view that treats the

conceptof customer perceived value as a multidimensional

construct (See, for example, De Ruyter, Wetzels, Lemmink,

& Mattson,1997;De Ruyter,Wetzels,& Bloemer,1998;

Sweeney,Soutar,& Johnson, 1999;Rust, Zeithaml,&

Lemmon,2000; Sweeney & Soutar,2001).For example,

Sweeney et al. (1999) identifies five dimensions: social value

(acceptability), emotional value, functional value (price/value

for money),functionalvalue(performance/quality) and func-

tional value (versatility); Kwun (2004) considers brand, price

and risk as the precursors of the formation ofvalue in the

restaurantindustry;Benkenstein etal. (2003) conclude that

satisfaction with leisure services is a function ofcognitive

and emotional (psychological) factors; and Petrick (2002)

consists of five components: behavioral price, monetary

emotional response, quality and reputation.

However,although these studies provide empiricalevi-

dence of the existence of the cognitive and affective dim

sions ofperceived value,none ofthem studies the overall

perceived value of a purchase from an Islamic perspectiv

Evaluation ofthe value oftourism products in the case of

Islamic tourism participation entails a completely differen

process because of the requirements of the Islamic Shari

Participation of Muslims in tourism activities requires acc

able goods, services and environments. Therefore, any a

to design a scale of measurement of the overall MCPV of

purchase,or to identify its dimensions,must not only reflect

a structure that identifies functional and affective dimensions

but also the Shari’ah-Compliant attributes.

Islamic attributes value

Undoubtedly, religious identity appears to play an import

role in shaping consumption experiences including hospi

tality and tourism choices among Muslim customers.It is a

religious compulsion for allMuslims to consume products

that are permitted by Allah (God) and falls under the juris

tion of Shari’ah.In Islam, Shari’ah-Complianttourism

products generally refer to all such products that are in a

dance with the instructions ofAlmighty Allah (God)and

ProphetMohammad (may peace be upon him).Shari’ah

designates the term ‘Halal’ specifically to the products th

are permissible, lawful and are unobjectionable to consum

Shari’ah-Complianttourism productsmay thereforeadd

value to Muslim consumers’ shopping experiences throug

Islamic benefits that contribute to the value of the shopp

experience.

Shari’ah principles are requirements forevery Muslim,

and sensitivity toward application oftheseprinciplesis

important because religious deeds are not acceptable if t

are not conductedappropriately.A typical Muslim is

expected to do regular prayers in clean environments an

in Ramadan. In Islamic teachings, Muslims are also expec

to abstainfrom profligateconsumptionand indulgence

(Hashim,Murphy,& Hashim,2007).In addition,Shari’ah

principles prohibitadultery,gambling,consumption of pork

and other haram (forbidden) foods, selling or drinking liq

and dressing inappropriately (Zamani-Farahani & Hender

2010). Therefore, Shari’ah compliance should be a prereq

for high value tourism experiences for Muslims.

Based on the aforementioned discussions,two conclu-

sions can be introduced to help in building an effective sc

to measure MCPV. Firstly, the view of perceived value as

cognitive variable is notenough,because itis necessary to

incorporatethe affectivecomponent.Secondly,Muslim

touristevaluates notonly the traditionalaspects ofvalue

(cognitive and affective components) butalso the religious

identity related aspects that contribute to the value crea

This overall vision underlies the multidimensional approa

to MCPV.

Muslim Customer Perceived Value251

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Customer satisfaction

According to Rodriguez del Bosque and San Martin (2008),

consumersatisfaction is notonly cognitive butalso emo-

tional. Although the literature contains significant differences

in the definition ofsatisfaction,thereare at leasttwo

common formulationsof satisfaction (Ekinci,Dawes,&

Massey,2008;Nam, Ekinci, & Whyatt, 2011):one is

transient(transaction-specific),whereas the other is overall

(or cumulative)satisfaction.Transientsatisfaction results

from the evaluation of activities and behaviors that take place

during a single,discrete interaction ata service encounter

(Oliver, 1997). A key implication of this definition suggests

thattransientsatisfaction should be captured immediately

after each service interaction with the service provider (e.g.

satisfaction with a specific employee) (Nam et al., 2011).

On the otherhand,overallsatisfaction is viewed as an

evaluative judgment of the last purchase occasion and based

on all encounters with service provider (Ekinci et al., 2008;

Nam et al.,2011).Transaction-specific satisfaction is likely

to vary from experienceto experience,whereasoverall

satisfaction is a moving average that is relatively stable and

mostsimilarto an overallattitude towardspurchasing a

brand.Therefore,this study follow Oliver (1997) and view

consumersatisfaction asa consumer’soverallemotional

response to the entire service experience for a single transac-

tion at the post purchasing point.

Customer loyalty

Loyalty is the most powerful outcome of consumer satisfac-

tion. It is a multidimensional construct that has been concep-

tualized and operationalized in many differentways in the

marketing literature(Oliver,1999).For example,Oliver

(1997) proposes three components of satisfaction: cognitive,

affective and conative.The latter includes the use of repeat

usage.Also, intention to return ishighly correlated with

otheroutcomes ofsatisfaction.However,despite the large

number of studies on customer loyalty, it has been seen from

two perspectives:behavioralloyalty and attitudinalloyalty

(e.g.Dick & Basu,1994;Nam etal., 2011).Behavioral

loyalty refers to the frequency of repeat purchase. Attitudinal

loyalty refers to the psychologicalcommitmentthata con-

sumer makes in the purchase act,such as intentions to pur-

chaseand intentionsto recommend withoutnecessarily

taking theactualrepeatpurchasebehaviorinto account

(Jacoby, 1971; Jarvis & Wilcox, 1976).

Customer retention

There is only one valid definition ofbusiness purpose:to

create and retain a customer.It is the customer who deter-

mines what the business is (Drucker, 1954). Generally speaking,

there is no clear definition of a successful tourism organization.

A successfultourism organization isone thatsucceedsin

meeting thebusinessobjectives.Theseobjectivescan be

customer acquisition, customer retention, customer satisfaction,

customer loyalty, better customer service or any other objectives

that are set by the organization. MCPV includes the delivery of

sustained or increasing levels of satisfaction, and the retention of

customers by the maintenance and promotion of the relationship

(Palmer, Lindgreen, & Vanhamme, 2005).

Hypotheses

Homburg and Bruhn distinguish between the constructs of

customerretention,customerloyalty and customersatis-

faction,which they see as linked by a two-stage causal

chain (Homburg & Bruhn,1998).Therefore,they suggest

distinguishing between the constructs of customer retenti

customer loyalty and customer satisfaction, which they se

linked by a two-stage causalchain.Accordingly,customer

satisfaction is a direct determining of customer loyalty, wh

in turn, is a centraldeterminantof customerretention.

Customersatisfaction and customerloyalty constructsare

affected by the different elements of MCPV.

However,the differentconstructs ofMCPV, the theo-

retical differentiation of customer retention, customer loya

and customer satisfaction that can be derived from the lite

ture,and the two-staged causallinks between these con-

structs willnextbe considered with regard to their specific

relevance for the tourism industry.

Effects ofMuslim Customer Perceived Value on customer

satisfaction

Previouswork showsthatvariousmeasuresof customer

value are positivelycorrelatedwith satisfaction(Lam,

Shankar, Erramilli, & Murthy, 2004; Spiteri & Dion, 2004).

Yet none ofthese measures includes items similarto the

notion ofMuslim attributesvalue.For example,studies

conducted by Battour,Ismail,and Battor (2011) identified

Islamic attributes ofdestinations thatmay attractMuslim

tourists such as the inclusion of prayer facilities, Halal food

Islamic entertainment,Islamic dress codes,generalIslamic

morality and the Islamic callto prayer.This study recom-

mended thatIslamicattributesof destination should be

developed forthe purpose ofempiricalresearch.Ozdemir

and Met (2012)also argued thatas Muslimstypically

observe a dress code and avoid free mixing,some hotels in

Turkey offer separateswimmingpool and recreational

facilities.Thus,a key question here iswhetherMuslim

customers’perception ofsuch Islamic attributesleadsto

satisfaction outright.

Derived from previous works on the multidimensional na

ture of consumption value, we can assume that positive an

negative value dimensions could have positive and negati

effects on the Muslim customer perceived value construct

Thus,the six dimensions ofSanchez etal. (2006)study

could be considered:among them,we choose functional

value (quality and price),emotional value and social value.

But,considering the specialnature of Muslim tourists,we

shall add another positive input of perceived value (Islami

attributes value).The research hypotheses supporting this

proposal are then as follows:

H1: The perceptions of benefits referred to quality will

have a positive impact on Muslim customer satisfaction

H2: The perceptions of price will have a positive impact

on Muslim customer satisfaction

H3: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to emotional

value willhave a positive impacton Muslim customer

satisfaction

252 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

According to Rodriguez del Bosque and San Martin (2008),

consumersatisfaction is notonly cognitive butalso emo-

tional. Although the literature contains significant differences

in the definition ofsatisfaction,thereare at leasttwo

common formulationsof satisfaction (Ekinci,Dawes,&

Massey,2008;Nam, Ekinci, & Whyatt, 2011):one is

transient(transaction-specific),whereas the other is overall

(or cumulative)satisfaction.Transientsatisfaction results

from the evaluation of activities and behaviors that take place

during a single,discrete interaction ata service encounter

(Oliver, 1997). A key implication of this definition suggests

thattransientsatisfaction should be captured immediately

after each service interaction with the service provider (e.g.

satisfaction with a specific employee) (Nam et al., 2011).

On the otherhand,overallsatisfaction is viewed as an

evaluative judgment of the last purchase occasion and based

on all encounters with service provider (Ekinci et al., 2008;

Nam et al.,2011).Transaction-specific satisfaction is likely

to vary from experienceto experience,whereasoverall

satisfaction is a moving average that is relatively stable and

mostsimilarto an overallattitude towardspurchasing a

brand.Therefore,this study follow Oliver (1997) and view

consumersatisfaction asa consumer’soverallemotional

response to the entire service experience for a single transac-

tion at the post purchasing point.

Customer loyalty

Loyalty is the most powerful outcome of consumer satisfac-

tion. It is a multidimensional construct that has been concep-

tualized and operationalized in many differentways in the

marketing literature(Oliver,1999).For example,Oliver

(1997) proposes three components of satisfaction: cognitive,

affective and conative.The latter includes the use of repeat

usage.Also, intention to return ishighly correlated with

otheroutcomes ofsatisfaction.However,despite the large

number of studies on customer loyalty, it has been seen from

two perspectives:behavioralloyalty and attitudinalloyalty

(e.g.Dick & Basu,1994;Nam etal., 2011).Behavioral

loyalty refers to the frequency of repeat purchase. Attitudinal

loyalty refers to the psychologicalcommitmentthata con-

sumer makes in the purchase act,such as intentions to pur-

chaseand intentionsto recommend withoutnecessarily

taking theactualrepeatpurchasebehaviorinto account

(Jacoby, 1971; Jarvis & Wilcox, 1976).

Customer retention

There is only one valid definition ofbusiness purpose:to

create and retain a customer.It is the customer who deter-

mines what the business is (Drucker, 1954). Generally speaking,

there is no clear definition of a successful tourism organization.

A successfultourism organization isone thatsucceedsin

meeting thebusinessobjectives.Theseobjectivescan be

customer acquisition, customer retention, customer satisfaction,

customer loyalty, better customer service or any other objectives

that are set by the organization. MCPV includes the delivery of

sustained or increasing levels of satisfaction, and the retention of

customers by the maintenance and promotion of the relationship

(Palmer, Lindgreen, & Vanhamme, 2005).

Hypotheses

Homburg and Bruhn distinguish between the constructs of

customerretention,customerloyalty and customersatis-

faction,which they see as linked by a two-stage causal

chain (Homburg & Bruhn,1998).Therefore,they suggest

distinguishing between the constructs of customer retenti

customer loyalty and customer satisfaction, which they se

linked by a two-stage causalchain.Accordingly,customer

satisfaction is a direct determining of customer loyalty, wh

in turn, is a centraldeterminantof customerretention.

Customersatisfaction and customerloyalty constructsare

affected by the different elements of MCPV.

However,the differentconstructs ofMCPV, the theo-

retical differentiation of customer retention, customer loya

and customer satisfaction that can be derived from the lite

ture,and the two-staged causallinks between these con-

structs willnextbe considered with regard to their specific

relevance for the tourism industry.

Effects ofMuslim Customer Perceived Value on customer

satisfaction

Previouswork showsthatvariousmeasuresof customer

value are positivelycorrelatedwith satisfaction(Lam,

Shankar, Erramilli, & Murthy, 2004; Spiteri & Dion, 2004).

Yet none ofthese measures includes items similarto the

notion ofMuslim attributesvalue.For example,studies

conducted by Battour,Ismail,and Battor (2011) identified

Islamic attributes ofdestinations thatmay attractMuslim

tourists such as the inclusion of prayer facilities, Halal food

Islamic entertainment,Islamic dress codes,generalIslamic

morality and the Islamic callto prayer.This study recom-

mended thatIslamicattributesof destination should be

developed forthe purpose ofempiricalresearch.Ozdemir

and Met (2012)also argued thatas Muslimstypically

observe a dress code and avoid free mixing,some hotels in

Turkey offer separateswimmingpool and recreational

facilities.Thus,a key question here iswhetherMuslim

customers’perception ofsuch Islamic attributesleadsto

satisfaction outright.

Derived from previous works on the multidimensional na

ture of consumption value, we can assume that positive an

negative value dimensions could have positive and negati

effects on the Muslim customer perceived value construct

Thus,the six dimensions ofSanchez etal. (2006)study

could be considered:among them,we choose functional

value (quality and price),emotional value and social value.

But,considering the specialnature of Muslim tourists,we

shall add another positive input of perceived value (Islami

attributes value).The research hypotheses supporting this

proposal are then as follows:

H1: The perceptions of benefits referred to quality will

have a positive impact on Muslim customer satisfaction

H2: The perceptions of price will have a positive impact

on Muslim customer satisfaction

H3: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to emotional

value willhave a positive impacton Muslim customer

satisfaction

252 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

H4: The perceptions of benefits referred to social value will

have a positive impact on Muslim customer satisfaction

H5: The perceptionsof benefitsreferredto Islamic

attributes value willhave a positive impacton Muslim

customer satisfaction

Effects ofMuslim Customer Perceived Value on

customer loyalty

Based on the literature review, loyalty is measured as a direct

result to customer satisfaction (Heskett, Sasser, & Schlesinger,

1997).However,many researcherssuggestthatsatisfying

customers may notbe sufficientto create loyalcustomers.

For example, conditions like a quality, cost, effort perceptions,

pleasure perceptions or personal characteristics may contribute

directly to loyalty behavior or shape the influence of satisfac-

tion (Lam et al., 2004). Most of these factors are studied under

the concept of customer value (e.g. risk in Day & Crask, 2000).

Therefore, a critical question is whether MCPV might serve as

a type of relationship switching barrier thatoperates in part

independently from satisfaction and directly influences cus-

tomer loyalty. We propose the following hypothesis to inves-

tigate this question:

H6: The perceptions of benefits referred to quality will

have a positive impact on Muslim customer loyalty

H7: The perceptions of price will have a positive impact

on Muslim customer loyalty

H8: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to emotional

value willhave a positive impacton Muslim customer

loyalty

H9: The perceptions of benefits referred to socialvalue

will have a positive impact on Muslim customer loyalty

H10: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to Islamic

attributes value willhave a positive impacton Muslim

customer loyalty

Effects of Muslim customer satisfaction on loyalty

Customer satisfaction is expected to be positively related to

customerloyalty (Zeithaml,Parasuraman,& Malhotra,

2000). Reichfeld and Schefter (2000) argue that loyalty is a

more importantcustomer consideration than even price.In

fact, these authors present evidence that there is a high cost

associated with low levels of loyalty.Loyalty is a sophisti-

cated construct.Generally speaking,satisfaction implies

loyalty,but not vice versa.Consequently,there is an asym-

metric relationship between loyalty and satisfaction.Many

other studies have shown that loyalty is measured as a direct

consequence to customer satisfaction (Heskett et al.,1997).

Therefore, the following hypotheses can be developed:

H11: Muslim customer satisfaction willhave a positive

impact on Muslim customer loyalty

Effects of satisfaction and loyalty on Muslim customer retention

Customersatisfaction and loyalty are positively related to

customer retention (Anderson,Fornell,& Lehmann,1994;

Reichheld,1993).Therefore,it is safe to assume thatif

customersatisfactionis positivelyrelatedto customer

loyalty, then customer satisfaction would eventually cont

ute to customerretention.Recentresearch hasexplored

relationships between customer value perceptions and b

satisfaction and loyalty (Lam etal., 2004).Here,we are

interested in examining ifthe advantage ofunderstanding

Muslim customers’ currentdesired value perceptions stops

here or if in fact anticipating Muslim customer value mak

any difference to customers. Further, the cumulative insi

of the services literature support the general notion that

value and satisfaction contribute to loyalty as a positive f

of behavioralintention consistentwith enhanced profits

through lucrative customerretention (Cronin etal., 2000;

Parasuraman & Grewal,2000).Thereforethe following

hypotheses are offered:

H12: Muslim customer satisfaction willhave a positive

impact on Muslim customer retention

H13: Muslim customer loyalty will have a positive impa

on Muslim customer retention

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Data collection

The generalizability of the study relied on the representa

ness of the respondents. Therefore, a representative sele

of Muslim tourists was made from a database ofMuslim

tourists.Several international tourism organizations that a

located in UK, Egypt and United Arab Emirateswere

contacted to give us access to their tourist database, of w

three prominentones accepted to give us such access.The

three organizations have been reassured thatonly members

of the research team willhave access to the data they give

and the completed questionnaire will not be made availa

to anyoneotherthan theresearch team.A databaseof

Muslim tourists has been made for data collection purpos

The criteria forselecting customers to participate were

simple. First, customer should be Muslim. Second, custom

should have boughta tourism package during the lasttwo

years.Finally,customers should come from differentcoun-

tries. This techniques resulted in a database of 6454 Mus

customers. A systematic random sampling method has b

used to draw asampleof 1000 customers.Systematic

random sampling usesthe samestatisticalprinciplesas

simple random sampling,thatis, p-values and confidence

intervals are calculated the same way.However,systematic

random sampling does not involve separate random sele

of each unit. For this reason, systematic random samplin

often used to select large samples from a long list of unit

research packet,which contained a covering letterand an

anonymous [self-administering] questionnaire, was e-ma

to the customers and a web link of the online survey has

been given in the e-mail. A total of 242 respondents retu

questionnaires,but21 were omitted from analysis due to

missing data,leaving a totalof 221 usefulresponses ora

24.71.96% overall response rate.

Muslim Customer Perceived Value253

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

have a positive impact on Muslim customer satisfaction

H5: The perceptionsof benefitsreferredto Islamic

attributes value willhave a positive impacton Muslim

customer satisfaction

Effects ofMuslim Customer Perceived Value on

customer loyalty

Based on the literature review, loyalty is measured as a direct

result to customer satisfaction (Heskett, Sasser, & Schlesinger,

1997).However,many researcherssuggestthatsatisfying

customers may notbe sufficientto create loyalcustomers.

For example, conditions like a quality, cost, effort perceptions,

pleasure perceptions or personal characteristics may contribute

directly to loyalty behavior or shape the influence of satisfac-

tion (Lam et al., 2004). Most of these factors are studied under

the concept of customer value (e.g. risk in Day & Crask, 2000).

Therefore, a critical question is whether MCPV might serve as

a type of relationship switching barrier thatoperates in part

independently from satisfaction and directly influences cus-

tomer loyalty. We propose the following hypothesis to inves-

tigate this question:

H6: The perceptions of benefits referred to quality will

have a positive impact on Muslim customer loyalty

H7: The perceptions of price will have a positive impact

on Muslim customer loyalty

H8: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to emotional

value willhave a positive impacton Muslim customer

loyalty

H9: The perceptions of benefits referred to socialvalue

will have a positive impact on Muslim customer loyalty

H10: The perceptionsof benefitsreferred to Islamic

attributes value willhave a positive impacton Muslim

customer loyalty

Effects of Muslim customer satisfaction on loyalty

Customer satisfaction is expected to be positively related to

customerloyalty (Zeithaml,Parasuraman,& Malhotra,

2000). Reichfeld and Schefter (2000) argue that loyalty is a

more importantcustomer consideration than even price.In

fact, these authors present evidence that there is a high cost

associated with low levels of loyalty.Loyalty is a sophisti-

cated construct.Generally speaking,satisfaction implies

loyalty,but not vice versa.Consequently,there is an asym-

metric relationship between loyalty and satisfaction.Many

other studies have shown that loyalty is measured as a direct

consequence to customer satisfaction (Heskett et al.,1997).

Therefore, the following hypotheses can be developed:

H11: Muslim customer satisfaction willhave a positive

impact on Muslim customer loyalty

Effects of satisfaction and loyalty on Muslim customer retention

Customersatisfaction and loyalty are positively related to

customer retention (Anderson,Fornell,& Lehmann,1994;

Reichheld,1993).Therefore,it is safe to assume thatif

customersatisfactionis positivelyrelatedto customer

loyalty, then customer satisfaction would eventually cont

ute to customerretention.Recentresearch hasexplored

relationships between customer value perceptions and b

satisfaction and loyalty (Lam etal., 2004).Here,we are

interested in examining ifthe advantage ofunderstanding

Muslim customers’ currentdesired value perceptions stops

here or if in fact anticipating Muslim customer value mak

any difference to customers. Further, the cumulative insi

of the services literature support the general notion that

value and satisfaction contribute to loyalty as a positive f

of behavioralintention consistentwith enhanced profits

through lucrative customerretention (Cronin etal., 2000;

Parasuraman & Grewal,2000).Thereforethe following

hypotheses are offered:

H12: Muslim customer satisfaction willhave a positive

impact on Muslim customer retention

H13: Muslim customer loyalty will have a positive impa

on Muslim customer retention

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Data collection

The generalizability of the study relied on the representa

ness of the respondents. Therefore, a representative sele

of Muslim tourists was made from a database ofMuslim

tourists.Several international tourism organizations that a

located in UK, Egypt and United Arab Emirateswere

contacted to give us access to their tourist database, of w

three prominentones accepted to give us such access.The

three organizations have been reassured thatonly members

of the research team willhave access to the data they give

and the completed questionnaire will not be made availa

to anyoneotherthan theresearch team.A databaseof

Muslim tourists has been made for data collection purpos

The criteria forselecting customers to participate were

simple. First, customer should be Muslim. Second, custom

should have boughta tourism package during the lasttwo

years.Finally,customers should come from differentcoun-

tries. This techniques resulted in a database of 6454 Mus

customers. A systematic random sampling method has b

used to draw asampleof 1000 customers.Systematic

random sampling usesthe samestatisticalprinciplesas

simple random sampling,thatis, p-values and confidence

intervals are calculated the same way.However,systematic

random sampling does not involve separate random sele

of each unit. For this reason, systematic random samplin

often used to select large samples from a long list of unit

research packet,which contained a covering letterand an

anonymous [self-administering] questionnaire, was e-ma

to the customers and a web link of the online survey has

been given in the e-mail. A total of 242 respondents retu

questionnaires,but21 were omitted from analysis due to

missing data,leaving a totalof 221 usefulresponses ora

24.71.96% overall response rate.

Muslim Customer Perceived Value253

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

The sample was dominated by male respondents (66.1%),

and this is normalbecause there are some restrictions in

Islam that prevents a woman from traveling on her own.In

termsof age,mostwere youngerthan 45 years[76.9%],

and a few respondent [approximately 8.6%] were older than

55 years.Approximately 62.4% ofthe respondents had at

leastsome college education,with 37.6% having earned a

postgraduate degree.With respectto the income level,

21.3% of the respondentsreported ahousehold income

between $1000 and $1999 permonth,23.1% reported a

household income between $2000 and $3999 permonth,

17.2% reported a household income between $4000 and

$5999 per month and 17.2% reported a household income

more than $6000 per month.Finally,we have respondents

from 28 different countries, which include Bangladesh, Egypt,

France,India,Indonesia,Iraq, Ireland,Jordan,Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon,Libya, Malaysia,

Morocco,Oman,Pakistan,Palestine,Qatar,Singapore,

Spain, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates,

UK, USA and Yemen.

Research instrument development – measures

We measured the five constructs (functional value (quality),

functionalvalue (price),emotionalvalue,socialvalue and

Islamic attributes value by multiple-item scales adapted from

previousstudies.All itemswere operationalized using a

five-pointLikert-type scale.

Firstly, in conceptualizing the cognitive value (functional

value),the originalSweeney and Soutar(2001)scale of

cognitive value is used in this study. According to Sweeney

and Soutar (2001),cognitive value is a dimension that con-

sists of two constructs – quality and price.Four five-point

Likert-type questions have been used to measure each one

of them.Secondly,in conceptualizing the affective value

(Emotional),we follow Sanchez et al.(2006) defining it as

a dimension that consists of two constructs – emotional value

and socialvalue – measured by four5-pointLikert-type

questions. We borrowed or adapted these items from Gallarza

and Saura (2006);Sanchez etal. (2006) and Sweeney and

Soutar (2001).

Secondly,in conceptualizingthe Islamic value,the

developmentof the research instrumentwas based mainly

on new scales, because we could not identify any past studies

directly addressing thisconstruct.However,threemain

sources have been used forthis purpose;Qur’an (Islam’s

holy book) and Sunnah (teachings,guidance and practices

of ProphetMohammad)and a thorough review ofthe

literature in which the variable is used theoretically or empir-

ically (Hashim et al., 2007; Stephenson et al., 2010; Zamani-

Farahani & Henderson, 2010; Battour et al., 2011; Laderlah,

Ab Rahman, Awang, & Man, 2011; Fakharyan et al., 2012;

Zamani-Farahani& Musa, 2012).For example,Studies

conductedby Battouret al. (2011)identifiedIslamic

attributes ofdestinations thatmay attractMuslim tourists

such as the inclusion of prayer facilities, Halal food, Islamic

entertainment, Islamic dress codes,general Islamic morality

and the Islamic callto prayer.Similarly,Ozdemir& Met

(2012) argued that as Muslims typically observe a dress code

and avoid free mixing. However, the three sources lead us to

measure the Islamic attributes value by four 5-point Likert

type questions.

Finally, in conceptualizing theMCPV consequences,

customer satisfaction,customer loyalty and customer reten-

tion are used in this study – measured by four items each

each category.We borrowed oradapted these items from

Cronin et al.(2000); Murphy,Pritchard,and Smith (2000);

Petrick (2002) and Eid (2007).

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

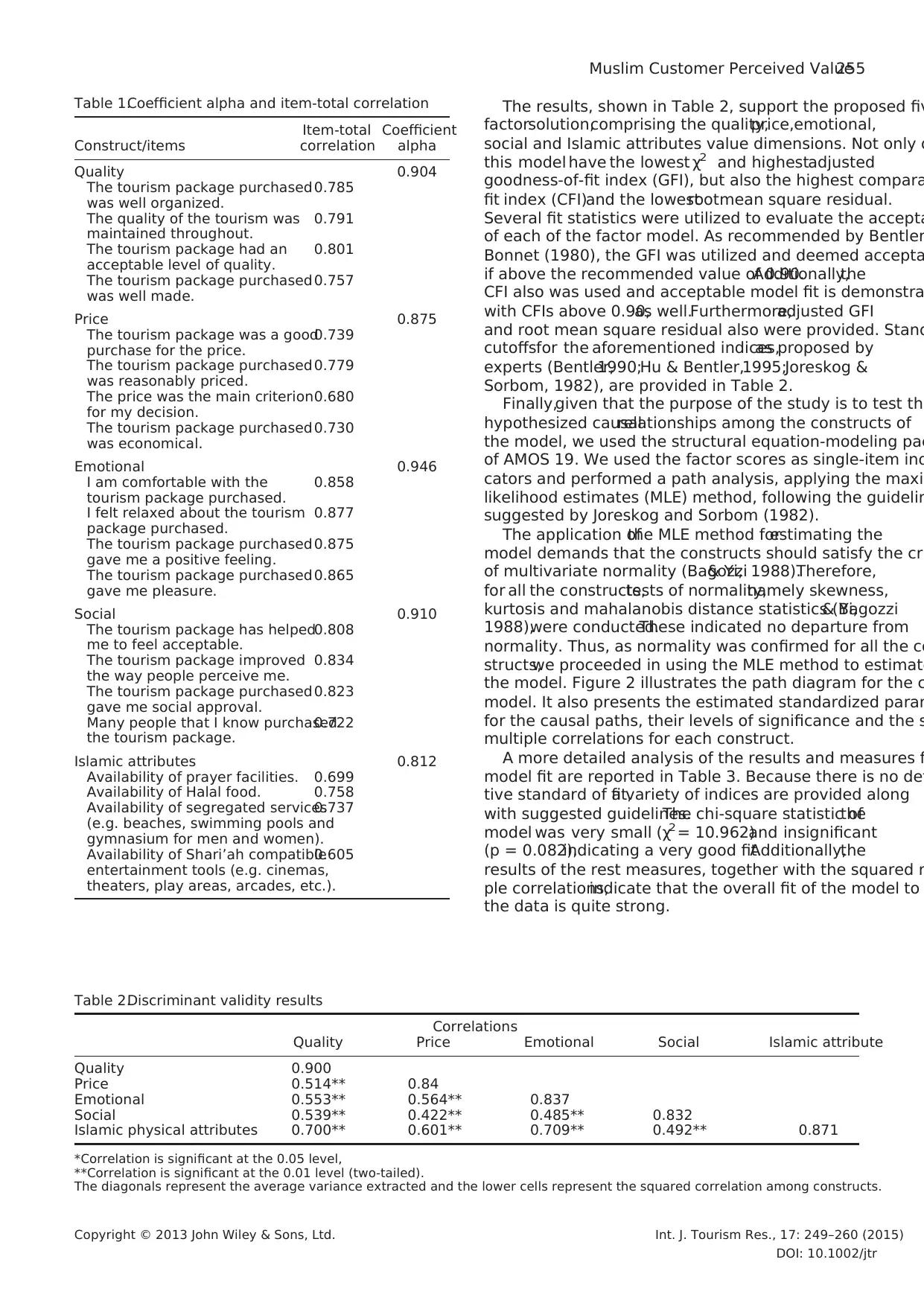

First,the psychometric propertiesof the constructswere

assessed by calculating theCronbach’salphareliability

coefficientand the items-to-totalcorrelation (Nunnally &

Bernstein,1994).As can be seen form Table 1,all scales

have reliability coefficientsranging from 0.812 to 0.946,

which exceed the cut-off level of 0.60 set for basic researc

(Nunnally, 1978).

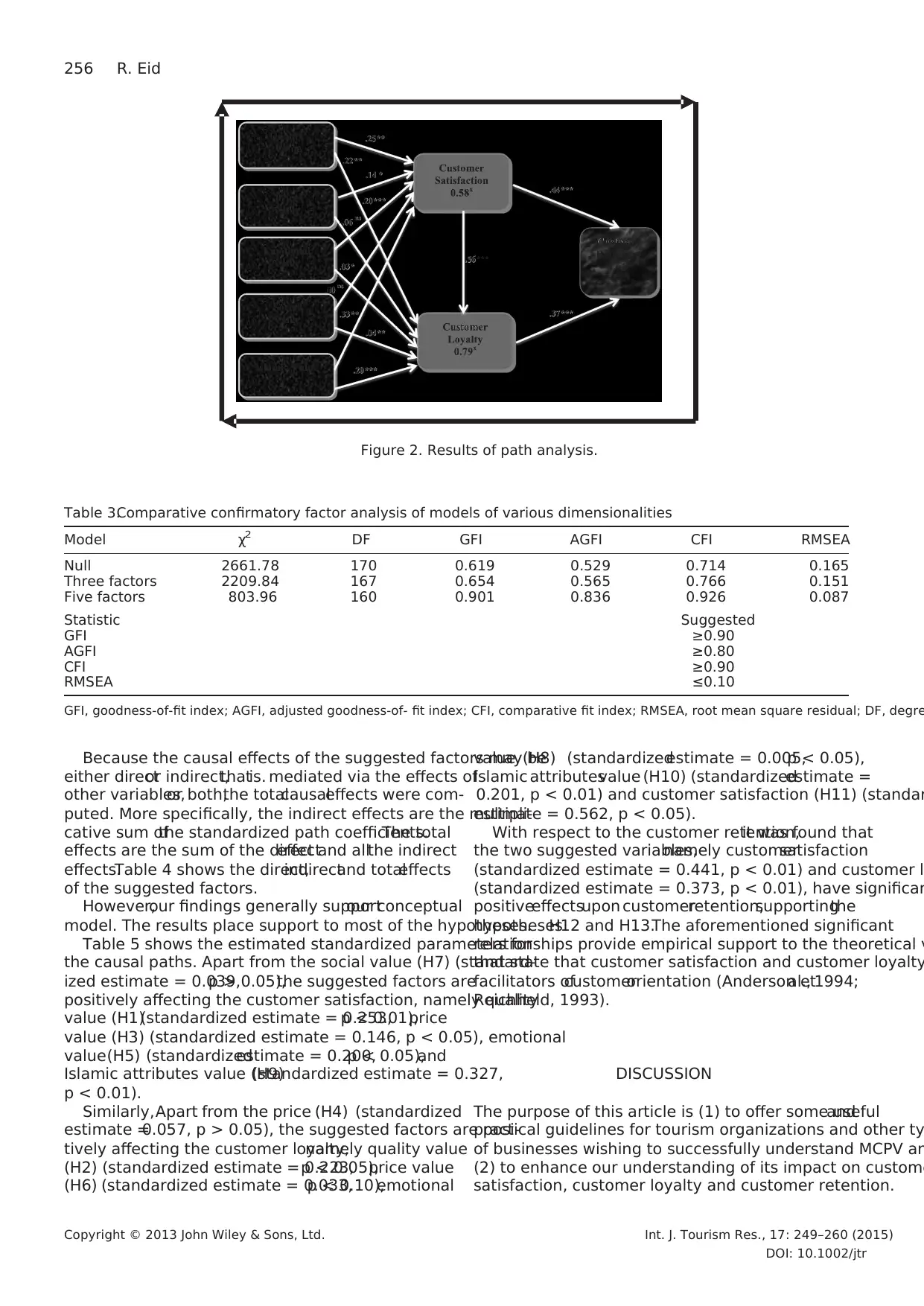

To meetthe requirements forsatisfactory discriminant

validity,Table 2 shows that the variances extracted by con-

structs(AVE) were greaterthan any squared correlation

among constructs (the factor scores as single-item indicat

have been used to calculate the between-constructs corre

tions); this implied that constructs were empirically distinc

Fornelland Larcker(1981).This indicates thateach con-

struct should share more variance with its items than it sh

with other constructs.In summary,the measurement model

test, including convergent and discriminant validity measu

was satisfactory.

Next, confirmatory factor analysis has been used to ass

the measurement models.Before building a model that will

considerall the dimensionsof value together,it is also

important to highlight, from a methodological point of view

that individualized analysis of each of those dimensions w

be made (the measurementmodel),in order to carry outa

priorrefinementof the items used in theirmeasurement.

Having established the five dimensionsof the scale,we

conducted a confirmatory factor analysis.For this research,

we chose to use both the structuralmodel(includes allthe

constructsin one model)and the measurementmodel

(separate model for each construct).

First, as suggested by many researchers (See, for exam

Fornell& Larcker,1981;Bollen,1989;Liang & Wang,

2004;Hair et al., 2006;Hooper,Coughlan,& Mullen,

2008; Čater & Čater, 2010), a null model, in which no facto

were considered to underlie the observed variables,correla-

tions between observed indicators were zero and the varia

of the observed variables were not restricted, was tested a

a series of models, namely, a one factor model (suggestin

the observed variables represent a single value dimension

three factor model (in which price and quality are suggest

to representa single functionaldimension ratherthan two

dimensions,emotionaland socialvaluesare suggested to

represent a single emotional dimension rather than two di

sions and Islamic attributes are suggested to represent a s

Islamic dimension rather than two dimensions),and a five-

factormodel(in which the dimensions are as proposed in

the earlier discussion).

254 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

and this is normalbecause there are some restrictions in

Islam that prevents a woman from traveling on her own.In

termsof age,mostwere youngerthan 45 years[76.9%],

and a few respondent [approximately 8.6%] were older than

55 years.Approximately 62.4% ofthe respondents had at

leastsome college education,with 37.6% having earned a

postgraduate degree.With respectto the income level,

21.3% of the respondentsreported ahousehold income

between $1000 and $1999 permonth,23.1% reported a

household income between $2000 and $3999 permonth,

17.2% reported a household income between $4000 and

$5999 per month and 17.2% reported a household income

more than $6000 per month.Finally,we have respondents

from 28 different countries, which include Bangladesh, Egypt,

France,India,Indonesia,Iraq, Ireland,Jordan,Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon,Libya, Malaysia,

Morocco,Oman,Pakistan,Palestine,Qatar,Singapore,

Spain, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates,

UK, USA and Yemen.

Research instrument development – measures

We measured the five constructs (functional value (quality),

functionalvalue (price),emotionalvalue,socialvalue and

Islamic attributes value by multiple-item scales adapted from

previousstudies.All itemswere operationalized using a

five-pointLikert-type scale.

Firstly, in conceptualizing the cognitive value (functional

value),the originalSweeney and Soutar(2001)scale of

cognitive value is used in this study. According to Sweeney

and Soutar (2001),cognitive value is a dimension that con-

sists of two constructs – quality and price.Four five-point

Likert-type questions have been used to measure each one

of them.Secondly,in conceptualizing the affective value

(Emotional),we follow Sanchez et al.(2006) defining it as

a dimension that consists of two constructs – emotional value

and socialvalue – measured by four5-pointLikert-type

questions. We borrowed or adapted these items from Gallarza

and Saura (2006);Sanchez etal. (2006) and Sweeney and

Soutar (2001).

Secondly,in conceptualizingthe Islamic value,the

developmentof the research instrumentwas based mainly

on new scales, because we could not identify any past studies

directly addressing thisconstruct.However,threemain

sources have been used forthis purpose;Qur’an (Islam’s

holy book) and Sunnah (teachings,guidance and practices

of ProphetMohammad)and a thorough review ofthe

literature in which the variable is used theoretically or empir-

ically (Hashim et al., 2007; Stephenson et al., 2010; Zamani-

Farahani & Henderson, 2010; Battour et al., 2011; Laderlah,

Ab Rahman, Awang, & Man, 2011; Fakharyan et al., 2012;

Zamani-Farahani& Musa, 2012).For example,Studies

conductedby Battouret al. (2011)identifiedIslamic

attributes ofdestinations thatmay attractMuslim tourists

such as the inclusion of prayer facilities, Halal food, Islamic

entertainment, Islamic dress codes,general Islamic morality

and the Islamic callto prayer.Similarly,Ozdemir& Met

(2012) argued that as Muslims typically observe a dress code

and avoid free mixing. However, the three sources lead us to

measure the Islamic attributes value by four 5-point Likert

type questions.

Finally, in conceptualizing theMCPV consequences,

customer satisfaction,customer loyalty and customer reten-

tion are used in this study – measured by four items each

each category.We borrowed oradapted these items from

Cronin et al.(2000); Murphy,Pritchard,and Smith (2000);

Petrick (2002) and Eid (2007).

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

First,the psychometric propertiesof the constructswere

assessed by calculating theCronbach’salphareliability

coefficientand the items-to-totalcorrelation (Nunnally &

Bernstein,1994).As can be seen form Table 1,all scales

have reliability coefficientsranging from 0.812 to 0.946,

which exceed the cut-off level of 0.60 set for basic researc

(Nunnally, 1978).

To meetthe requirements forsatisfactory discriminant

validity,Table 2 shows that the variances extracted by con-

structs(AVE) were greaterthan any squared correlation

among constructs (the factor scores as single-item indicat

have been used to calculate the between-constructs corre

tions); this implied that constructs were empirically distinc

Fornelland Larcker(1981).This indicates thateach con-

struct should share more variance with its items than it sh

with other constructs.In summary,the measurement model

test, including convergent and discriminant validity measu

was satisfactory.

Next, confirmatory factor analysis has been used to ass

the measurement models.Before building a model that will

considerall the dimensionsof value together,it is also

important to highlight, from a methodological point of view

that individualized analysis of each of those dimensions w

be made (the measurementmodel),in order to carry outa

priorrefinementof the items used in theirmeasurement.

Having established the five dimensionsof the scale,we

conducted a confirmatory factor analysis.For this research,

we chose to use both the structuralmodel(includes allthe

constructsin one model)and the measurementmodel

(separate model for each construct).

First, as suggested by many researchers (See, for exam

Fornell& Larcker,1981;Bollen,1989;Liang & Wang,

2004;Hair et al., 2006;Hooper,Coughlan,& Mullen,

2008; Čater & Čater, 2010), a null model, in which no facto

were considered to underlie the observed variables,correla-

tions between observed indicators were zero and the varia

of the observed variables were not restricted, was tested a

a series of models, namely, a one factor model (suggestin

the observed variables represent a single value dimension

three factor model (in which price and quality are suggest

to representa single functionaldimension ratherthan two

dimensions,emotionaland socialvaluesare suggested to

represent a single emotional dimension rather than two di

sions and Islamic attributes are suggested to represent a s

Islamic dimension rather than two dimensions),and a five-

factormodel(in which the dimensions are as proposed in

the earlier discussion).

254 R. Eid

Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Int. J. Tourism Res., 17: 249–260 (2015)

DOI: 10.1002/jtr

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

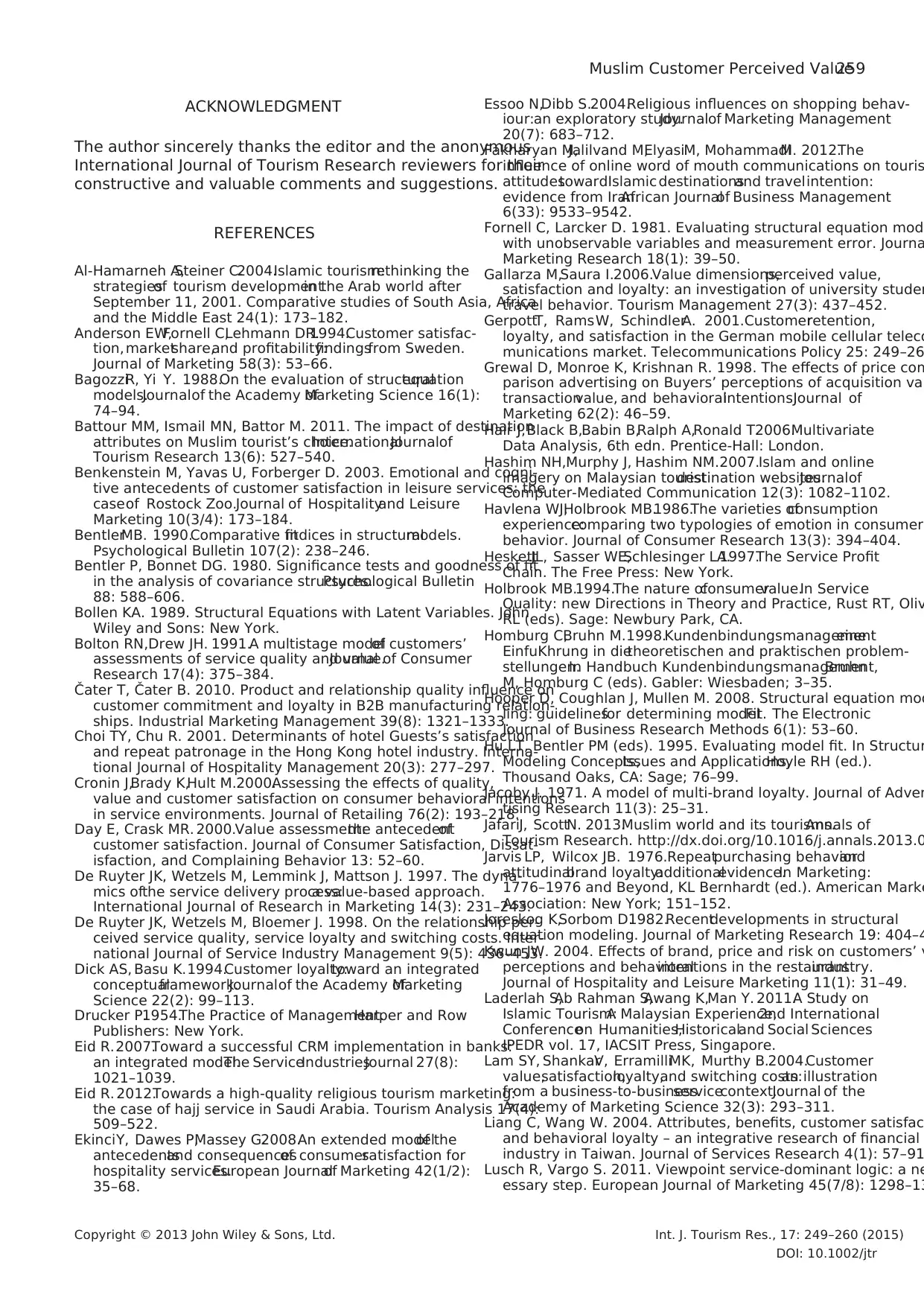

The results, shown in Table 2, support the proposed fiv

factorsolution,comprising the quality,price,emotional,

social and Islamic attributes value dimensions. Not only d

this model have the lowest χ2 and highestadjusted

goodness-of-fit index (GFI), but also the highest compara

fit index (CFI)and the lowestrootmean square residual.

Several fit statistics were utilized to evaluate the accepta

of each of the factor model. As recommended by Bentler

Bonnet (1980), the GFI was utilized and deemed accepta

if above the recommended value of 0.90.Additionally,the

CFI also was used and acceptable model fit is demonstra

with CFIs above 0.90,as well.Furthermore,adjusted GFI

and root mean square residual also were provided. Stand

cutoffsfor the aforementioned indices,as proposed by

experts (Bentler,1990;Hu & Bentler,1995;Joreskog &

Sorbom, 1982), are provided in Table 2.

Finally,given that the purpose of the study is to test the

hypothesized causalrelationships among the constructs of

the model, we used the structural equation-modeling pac

of AMOS 19. We used the factor scores as single-item ind

cators and performed a path analysis, applying the maxi

likelihood estimates (MLE) method, following the guidelin

suggested by Joreskog and Sorbom (1982).

The application ofthe MLE method forestimating the

model demands that the constructs should satisfy the cri

of multivariate normality (Bagozzi& Yi, 1988).Therefore,

for all the constructs,tests of normality,namely skewness,

kurtosis and mahalanobis distance statistics (Bagozzi& Yi,

1988),were conducted.These indicated no departure from

normality. Thus, as normality was confirmed for all the co

structs,we proceeded in using the MLE method to estimate

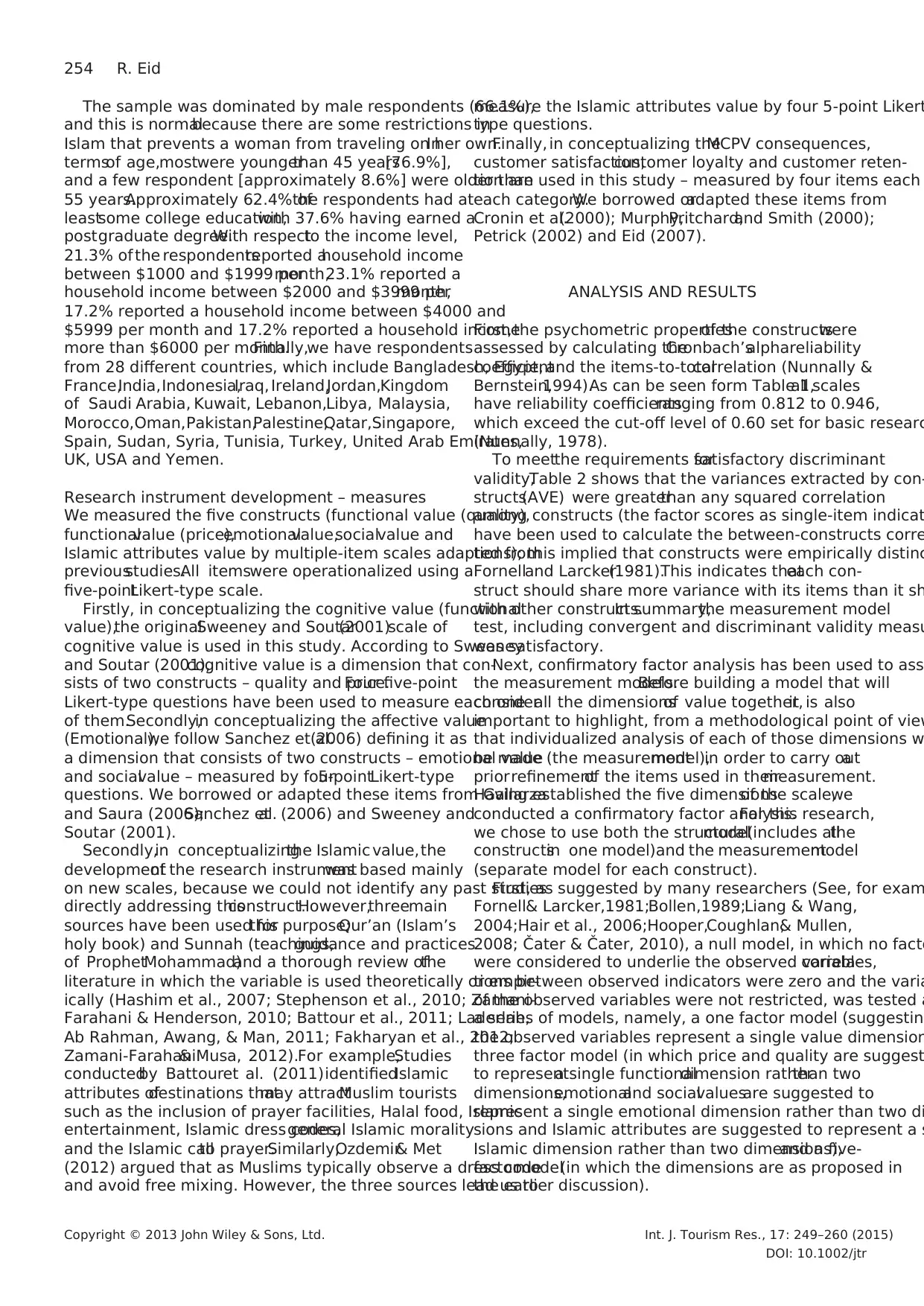

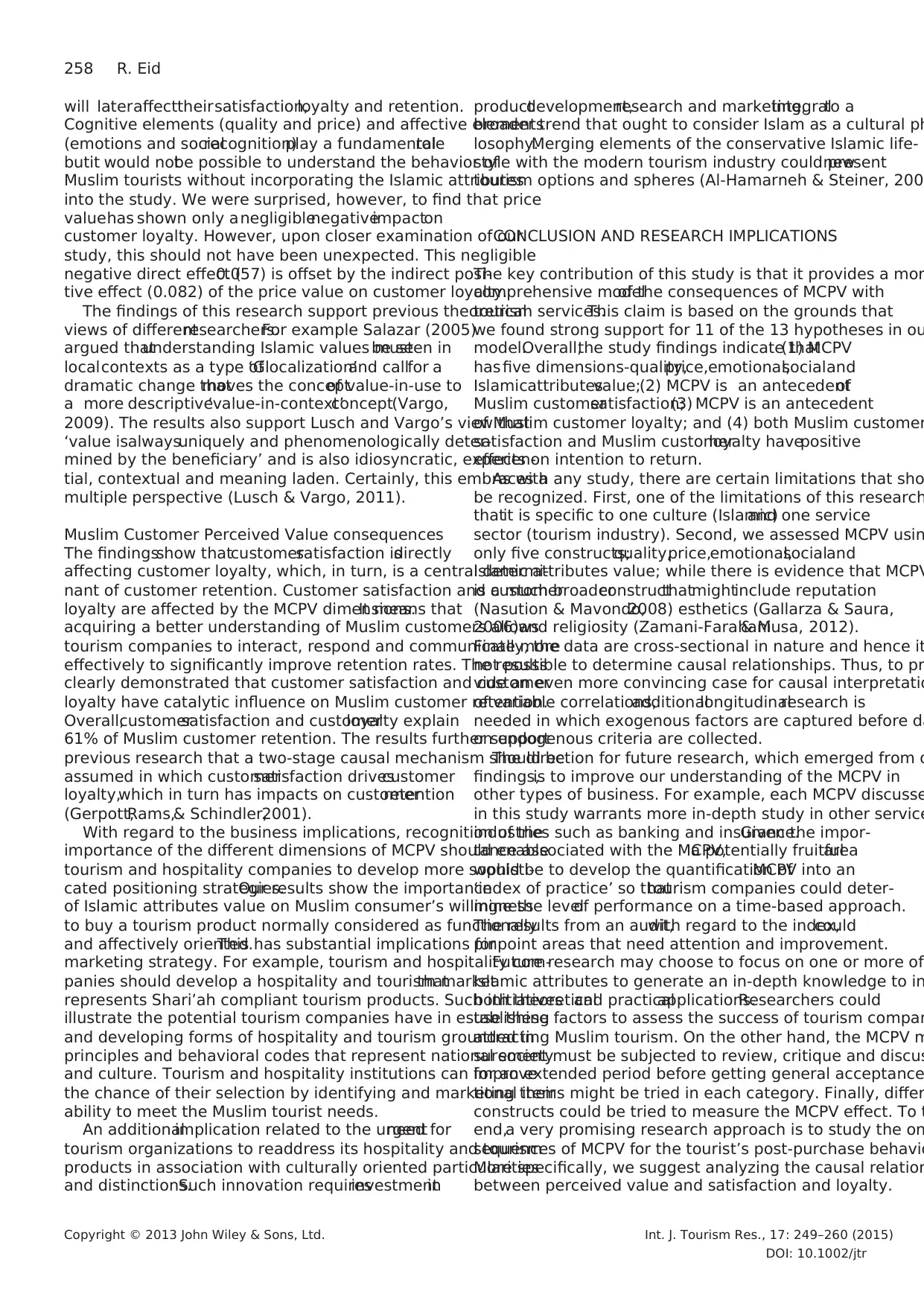

the model. Figure 2 illustrates the path diagram for the c

model. It also presents the estimated standardized param

for the causal paths, their levels of significance and the s

multiple correlations for each construct.

A more detailed analysis of the results and measures f

model fit are reported in Table 3. Because there is no defi

tive standard of fit,a variety of indices are provided along

with suggested guidelines.The chi-square statistic ofthe

model was very small (χ2= 10.962)and insignificant

(p = 0.082),indicating a very good fit.Additionally,the

results of the rest measures, together with the squared m

ple correlations,indicate that the overall fit of the model to

the data is quite strong.

Table 1.Coefficient alpha and item-total correlation

Construct/items

Item-total

correlation

Coefficient

alpha

Quality 0.904

The tourism package purchased

was well organized.

0.785

The quality of the tourism was

maintained throughout.

0.791

The tourism package had an

acceptable level of quality.

0.801

The tourism package purchased

was well made.

0.757

Price 0.875

The tourism package was a good

purchase for the price.

0.739

The tourism package purchased

was reasonably priced.

0.779