Content of Articles Project 2022

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/09

|100

|31028

|23

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Content of Articles

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1. Shorten Grilled on Negative Gearing and Franking Credits

Labor Leader Bill Shorten has been grilled about his party's planned changes to negative

gearing and franking credits during a special episode of ABC's Q&A.

If elected on 18 May, a federal Labor government would scrap negative gearing on

investment properties from 1 January in 2020, except for newly-constructed houses.

Bill Shorten appeared on Q&A with less than two weeks to go before the May 18

election.

Bill Shorten appeared on Q&A with less than two weeks to go before the May 18

election.

ABC

Negative gearing allows property owners to claim rental losses as a tax deduction.

Speaking in front of a live studio audience in Melbourne, Mr Shorten insisted that the

changes were not tax hikes, but the removal of tax subsidies.

"You use the word tax. If I'm not giving you a subsidy for you making a loss on an

investment property, that ain't a new tax. It just means you're not getting a new subsidy,"

Mr Shorten said.

Will Labor’s negative gearing policy lead to more property owners selling then claiming

pensions? #QandA pic.twitter.com/4DH7tarWvH

Labor Leader Bill Shorten has been grilled about his party's planned changes to negative

gearing and franking credits during a special episode of ABC's Q&A.

If elected on 18 May, a federal Labor government would scrap negative gearing on

investment properties from 1 January in 2020, except for newly-constructed houses.

Bill Shorten appeared on Q&A with less than two weeks to go before the May 18

election.

Bill Shorten appeared on Q&A with less than two weeks to go before the May 18

election.

ABC

Negative gearing allows property owners to claim rental losses as a tax deduction.

Speaking in front of a live studio audience in Melbourne, Mr Shorten insisted that the

changes were not tax hikes, but the removal of tax subsidies.

"You use the word tax. If I'm not giving you a subsidy for you making a loss on an

investment property, that ain't a new tax. It just means you're not getting a new subsidy,"

Mr Shorten said.

Will Labor’s negative gearing policy lead to more property owners selling then claiming

pensions? #QandA pic.twitter.com/4DH7tarWvH

— ABC Q&A (@QandA) May 6, 2019

The Opposition Leader was also confronted by a man who said he would lose 20 per cent

of his income as a result of Labor's plans to limit franking credits.

Mr Shorten said it was a "gift" paid for by millions of working Australians.

While Labor has tried to focus on health during the election campaign, its come under

pressure to explain how it will pay for its policies.

Asked to detail the cost of its climate policy, Mr Shorten dismissed it as a "dumb

question".

"You can't have a debate about climate change without talking about the cost of

inaction," he said.

"There is a cost. The bushfires, the extreme weather events, the insurance premiums."

Indigenous suicide a 'national emergency'

During the hour-long session, Mr Shorten also declared Indigenous suicide is now at the

level of a national emergency.

The Opposition Leader was also confronted by a man who said he would lose 20 per cent

of his income as a result of Labor's plans to limit franking credits.

Mr Shorten said it was a "gift" paid for by millions of working Australians.

While Labor has tried to focus on health during the election campaign, its come under

pressure to explain how it will pay for its policies.

Asked to detail the cost of its climate policy, Mr Shorten dismissed it as a "dumb

question".

"You can't have a debate about climate change without talking about the cost of

inaction," he said.

"There is a cost. The bushfires, the extreme weather events, the insurance premiums."

Indigenous suicide a 'national emergency'

During the hour-long session, Mr Shorten also declared Indigenous suicide is now at the

level of a national emergency.

The Labor leader said Australia needs to redefine its relationship with its indigenous

people from one of indifference or paternalism to a true partnership.

"I think it's a national disaster, (a) national emergency," he told ABC's Q&A on Monday

night.

ELECTION19 BILL SHORTEN CAMPAIGN DAY 26

Labor Leader Bill Shorten.

AAP

"The issue of suicide is massive. But also the issue of our first Australians and the

inequality of the lives that many of them live is massive. There's an intersection."

He noted both his party and the coalition had committed to a range of suicide prevention

projects, particularly ones aimed at young people, during the lead-up to the 18 May

election.

But, he said, Labor also had a unique idea to help make sure indigenous people received

holistic solutions: making an indigenous man, Pat Dodson, the minister.

How would a Shorten government reduce Indigenous youth suicide? #QandA

pic.twitter.com/AjqpkVXpru

— ABC Q&A (@QandA) May 6, 2019

people from one of indifference or paternalism to a true partnership.

"I think it's a national disaster, (a) national emergency," he told ABC's Q&A on Monday

night.

ELECTION19 BILL SHORTEN CAMPAIGN DAY 26

Labor Leader Bill Shorten.

AAP

"The issue of suicide is massive. But also the issue of our first Australians and the

inequality of the lives that many of them live is massive. There's an intersection."

He noted both his party and the coalition had committed to a range of suicide prevention

projects, particularly ones aimed at young people, during the lead-up to the 18 May

election.

But, he said, Labor also had a unique idea to help make sure indigenous people received

holistic solutions: making an indigenous man, Pat Dodson, the minister.

How would a Shorten government reduce Indigenous youth suicide? #QandA

pic.twitter.com/AjqpkVXpru

— ABC Q&A (@QandA) May 6, 2019

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

"Sometimes we judge ourselves by how many billionaires we have on the Forbes Rich

List," Mr Shorten said.

"I have a view we should judge ourselves by if we have a great disadvantage."

Mr Dodson spoke at Labor's campaign launch on Sunday, releasing the party's plans for

working with indigenous people.

These include creating a system of regional assemblies and a Voice to the national

parliament, establishing a national Makarrata commission and local truth-telling

programs, building a national resting place for the unknown warriors, and giving justice

and compensation to survivors of the stolen generation.

2. 11 Urban Myths About Franking Credits

The decision to introduce dividend imputation has provided an unforeseen benefit for

Australia, perhaps one that is still not fully appreciated by policy makers – it has made

Australian companies manage their capital more efficiently. That makes them sounder

investments.

Yet this benefit appears to be in jeopardy because the debate about the value of dividend

imputation is obscured by myths. This submission seeks to puncture these illusions in the

hope that policy makers will possess the information they need when judging the

effectiveness of a tax system that has served Australia well since 1987

List," Mr Shorten said.

"I have a view we should judge ourselves by if we have a great disadvantage."

Mr Dodson spoke at Labor's campaign launch on Sunday, releasing the party's plans for

working with indigenous people.

These include creating a system of regional assemblies and a Voice to the national

parliament, establishing a national Makarrata commission and local truth-telling

programs, building a national resting place for the unknown warriors, and giving justice

and compensation to survivors of the stolen generation.

2. 11 Urban Myths About Franking Credits

The decision to introduce dividend imputation has provided an unforeseen benefit for

Australia, perhaps one that is still not fully appreciated by policy makers – it has made

Australian companies manage their capital more efficiently. That makes them sounder

investments.

Yet this benefit appears to be in jeopardy because the debate about the value of dividend

imputation is obscured by myths. This submission seeks to puncture these illusions in the

hope that policy makers will possess the information they need when judging the

effectiveness of a tax system that has served Australia well since 1987

Myth 1: Franking is an anachronism; Australia should modernise its tax structure

Reality: Franking’s primary benefits – avoiding double taxation, removing the incentive for

high levels of corporate debt – remain valid

Dividend imputation was introduced to avoid the unfairness of taxing company profits twice.

That motivation still stands. Without franking, the interest expense deduction would be

expected to have more influence in corporate funding. Since the introduction of franking,

Australian companies have increased their gearing levels – in line with the secular decline in

interest rates in the western world – but to a lesser extent than US companies have.

Not creating further incentives for Australian corporates to take on more debt is highly

desirable since negative gearing has created an incentive for high levels of borrowing by the

household sector:

Myth 2: Franking is all about the tax refunds

Reality: Franking’s most important influence has been on capital allocation within the

economy

Reality: Franking’s primary benefits – avoiding double taxation, removing the incentive for

high levels of corporate debt – remain valid

Dividend imputation was introduced to avoid the unfairness of taxing company profits twice.

That motivation still stands. Without franking, the interest expense deduction would be

expected to have more influence in corporate funding. Since the introduction of franking,

Australian companies have increased their gearing levels – in line with the secular decline in

interest rates in the western world – but to a lesser extent than US companies have.

Not creating further incentives for Australian corporates to take on more debt is highly

desirable since negative gearing has created an incentive for high levels of borrowing by the

household sector:

Myth 2: Franking is all about the tax refunds

Reality: Franking’s most important influence has been on capital allocation within the

economy

Growth and innovation require that funds available for investment are channelled to the most

promising opportunities. Franking facilitates this by automatically prompting companies that

generate the most cash flow to pay it out, which allows shareholders to reinvest that cash

flow into the best opportunities. Without franking, this capital-recycling process would be

diminished due to the friction of corporate tax reducing the funds available to be reinvested.

This recycling is necessary in Australia, which is an economy of cash-flow “haves” and cash-

flow “have nots”. As the charts below show, Australia has a greater proportion of its market

comprised of larger companies. Further, smaller companies in the US tend to generate higher

returns than their counterparts in Australia. This means that Australia’s smaller companies

are more reliant on attracting the dividends flowing from the largest stocks.

Myth 3: Australia has enjoyed extended economic growth. Franking has played no part in

this

Reality: It is likely that franking has contributed to Australia’s lower economic volatility

Franking constrains corporate reinvestment. If we assume that companies will fund their best

projects first, their second-best projects second, etc., then constrained reinvestment should

result in better outcomes. If only the best projects are funded, then those projects are likely to

be more robust through the economic cycle. At the margin, this likely brings greater stability

to employment, consumer sentiment, etc.

promising opportunities. Franking facilitates this by automatically prompting companies that

generate the most cash flow to pay it out, which allows shareholders to reinvest that cash

flow into the best opportunities. Without franking, this capital-recycling process would be

diminished due to the friction of corporate tax reducing the funds available to be reinvested.

This recycling is necessary in Australia, which is an economy of cash-flow “haves” and cash-

flow “have nots”. As the charts below show, Australia has a greater proportion of its market

comprised of larger companies. Further, smaller companies in the US tend to generate higher

returns than their counterparts in Australia. This means that Australia’s smaller companies

are more reliant on attracting the dividends flowing from the largest stocks.

Myth 3: Australia has enjoyed extended economic growth. Franking has played no part in

this

Reality: It is likely that franking has contributed to Australia’s lower economic volatility

Franking constrains corporate reinvestment. If we assume that companies will fund their best

projects first, their second-best projects second, etc., then constrained reinvestment should

result in better outcomes. If only the best projects are funded, then those projects are likely to

be more robust through the economic cycle. At the margin, this likely brings greater stability

to employment, consumer sentiment, etc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

As expected, corporate returns in Australia have improved, and have advanced more than

returns in the US:

This holds true even after excluding the anomalous mining and tech sectors:

What’s more, the quality of returns has improved, as the variance of returns has diminished

and the persistence of high returns has increased:

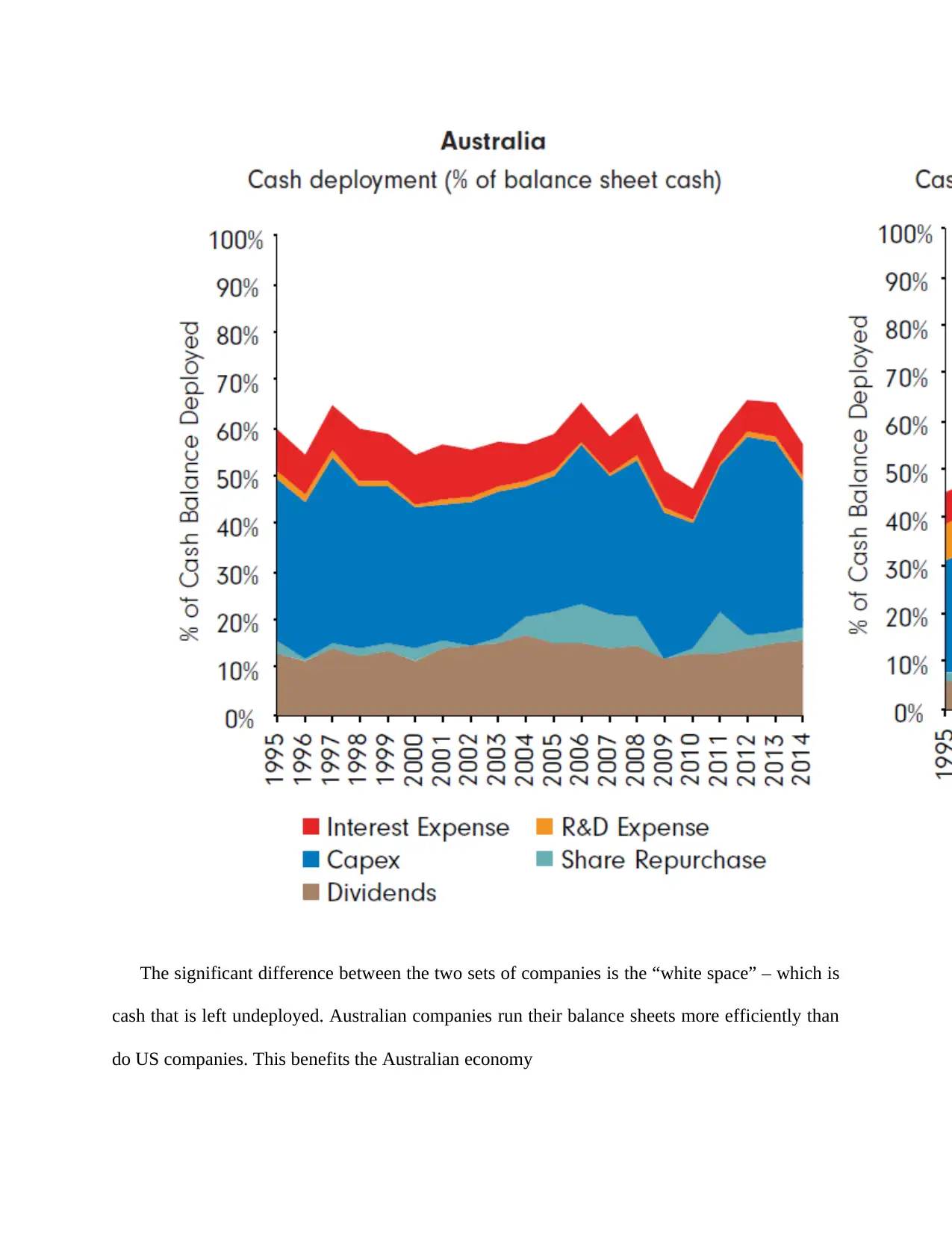

Myth 4: If Australian companies have higher payout ratios, it must be at the expense of

capex – but we need more investment now, not less

Reality: Relative to US companies, Australian companies pay higher dividends and also

invest more; the key difference is that Australian companies run their balance sheets more

efficiently

In this instance, it’s best to look at companies’ overall use of cash. Despite higher payouts

(and higher interest expense), Australian companies do not spend less on capex. There is no

evidence that higher payouts have led to lower levels of investment.

returns in the US:

This holds true even after excluding the anomalous mining and tech sectors:

What’s more, the quality of returns has improved, as the variance of returns has diminished

and the persistence of high returns has increased:

Myth 4: If Australian companies have higher payout ratios, it must be at the expense of

capex – but we need more investment now, not less

Reality: Relative to US companies, Australian companies pay higher dividends and also

invest more; the key difference is that Australian companies run their balance sheets more

efficiently

In this instance, it’s best to look at companies’ overall use of cash. Despite higher payouts

(and higher interest expense), Australian companies do not spend less on capex. There is no

evidence that higher payouts have led to lower levels of investment.

The significant difference between the two sets of companies is the “white space” – which is

cash that is left undeployed. Australian companies run their balance sheets more efficiently than

do US companies. This benefits the Australian economy

cash that is left undeployed. Australian companies run their balance sheets more efficiently than

do US companies. This benefits the Australian economy

Myth 5: Franking promotes higher payouts, which reduces reinvestment and lowers

future growth

Reality: Higher payouts indicate higher future earnings growth – there is no income-

growth trade-off

Conventional wisdom holds that companies retain more earnings when growth opportunities

are ample and fruitful. Therefore, the paying out of large amounts of dividends signals a paucity

of good growth opportunities. However, academic analysis challenges this view. Arnott and

Asness (2003) used 130 years’ worth of data to show that it is high-payout firms that generate

the best earnings growth over time.

The work of Zhou and Ruland (2006) supported the Arnott and Asness conclusion. By using

data over 50 years, their paper showed that high-dividend-payout companies tend to experience

“strong, not weak, future earnings growth”.

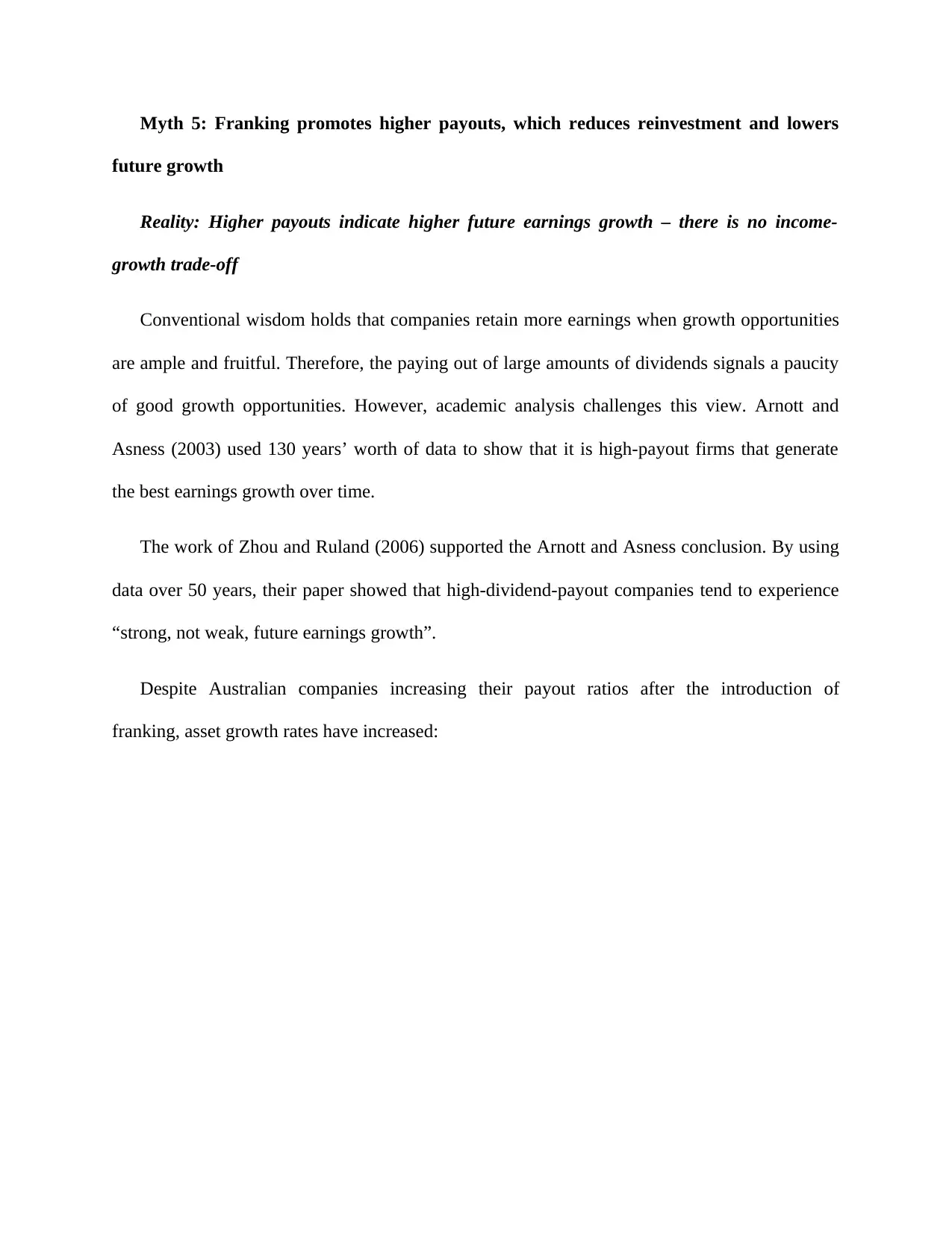

Despite Australian companies increasing their payout ratios after the introduction of

franking, asset growth rates have increased:

future growth

Reality: Higher payouts indicate higher future earnings growth – there is no income-

growth trade-off

Conventional wisdom holds that companies retain more earnings when growth opportunities

are ample and fruitful. Therefore, the paying out of large amounts of dividends signals a paucity

of good growth opportunities. However, academic analysis challenges this view. Arnott and

Asness (2003) used 130 years’ worth of data to show that it is high-payout firms that generate

the best earnings growth over time.

The work of Zhou and Ruland (2006) supported the Arnott and Asness conclusion. By using

data over 50 years, their paper showed that high-dividend-payout companies tend to experience

“strong, not weak, future earnings growth”.

Despite Australian companies increasing their payout ratios after the introduction of

franking, asset growth rates have increased:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Myth 6: Franking turns the Australian market into a high-yield, low-price-return

market

Reality: Higher dividend-paying share markets deliver higher price returns – even at the

aggregate level. There is no income-growth trade-off

market

Reality: Higher dividend-paying share markets deliver higher price returns – even at the

aggregate level. There is no income-growth trade-off

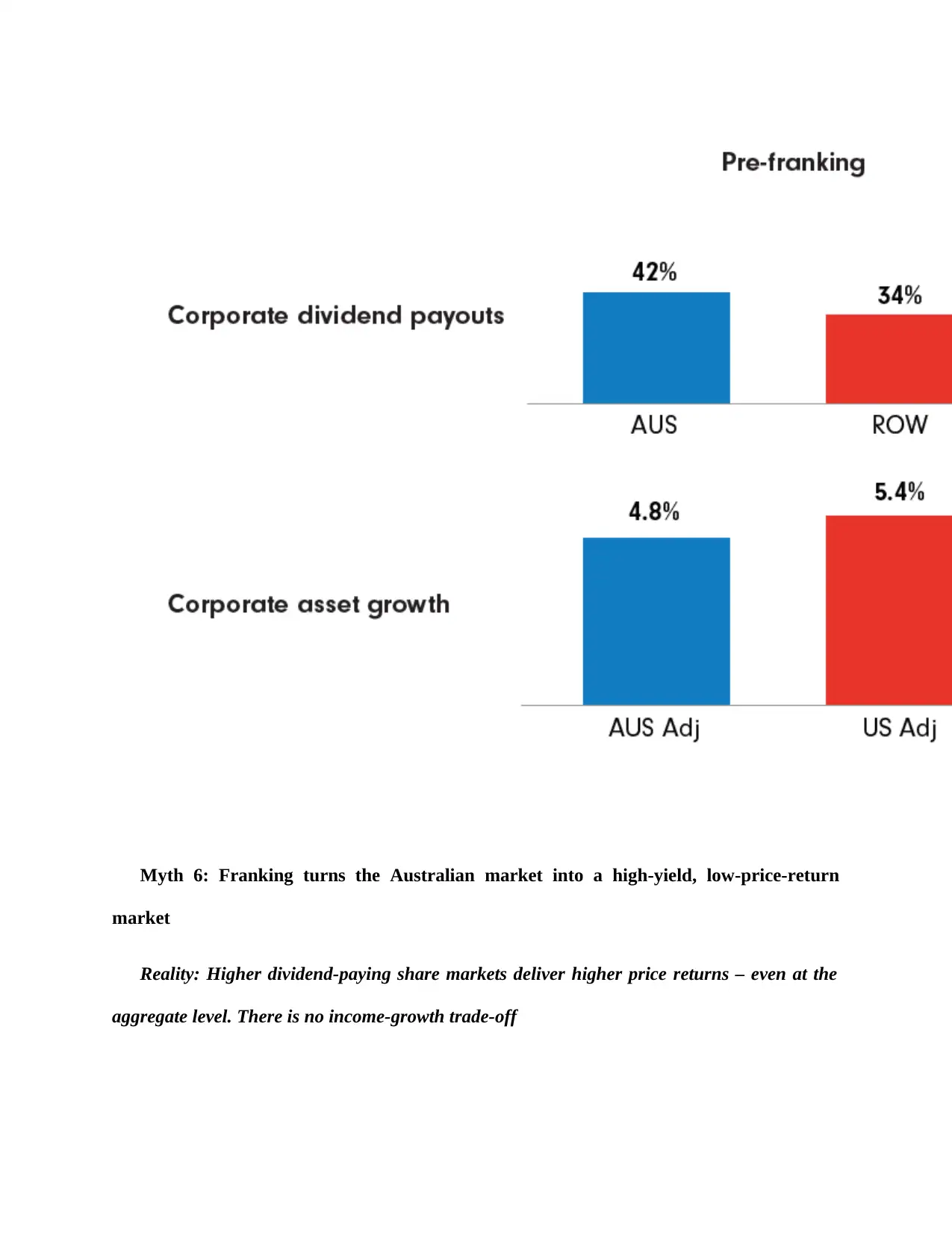

Conventional wisdom assumes that high-dividend stocks offer low growth potential. The

perception is that companies that return much of their earnings to shareholders have less to invest

than companies that retain their profits. But again this is not supported by the data: over time,

high-yielding stock markets have offered the highest total shareholder returns.

Analysis by the London Business School shows that the highest-yielding stock markets

returned 13.5% p.a. from 1900 to 2010 versus 5.5% p.a. from the lowest-yielding markets. As

the chart below shows, the highest-yielding markets were the top performers over every

consecutive quarter-century period last century and over the first decade of the 21st century

perception is that companies that return much of their earnings to shareholders have less to invest

than companies that retain their profits. But again this is not supported by the data: over time,

high-yielding stock markets have offered the highest total shareholder returns.

Analysis by the London Business School shows that the highest-yielding stock markets

returned 13.5% p.a. from 1900 to 2010 versus 5.5% p.a. from the lowest-yielding markets. As

the chart below shows, the highest-yielding markets were the top performers over every

consecutive quarter-century period last century and over the first decade of the 21st century

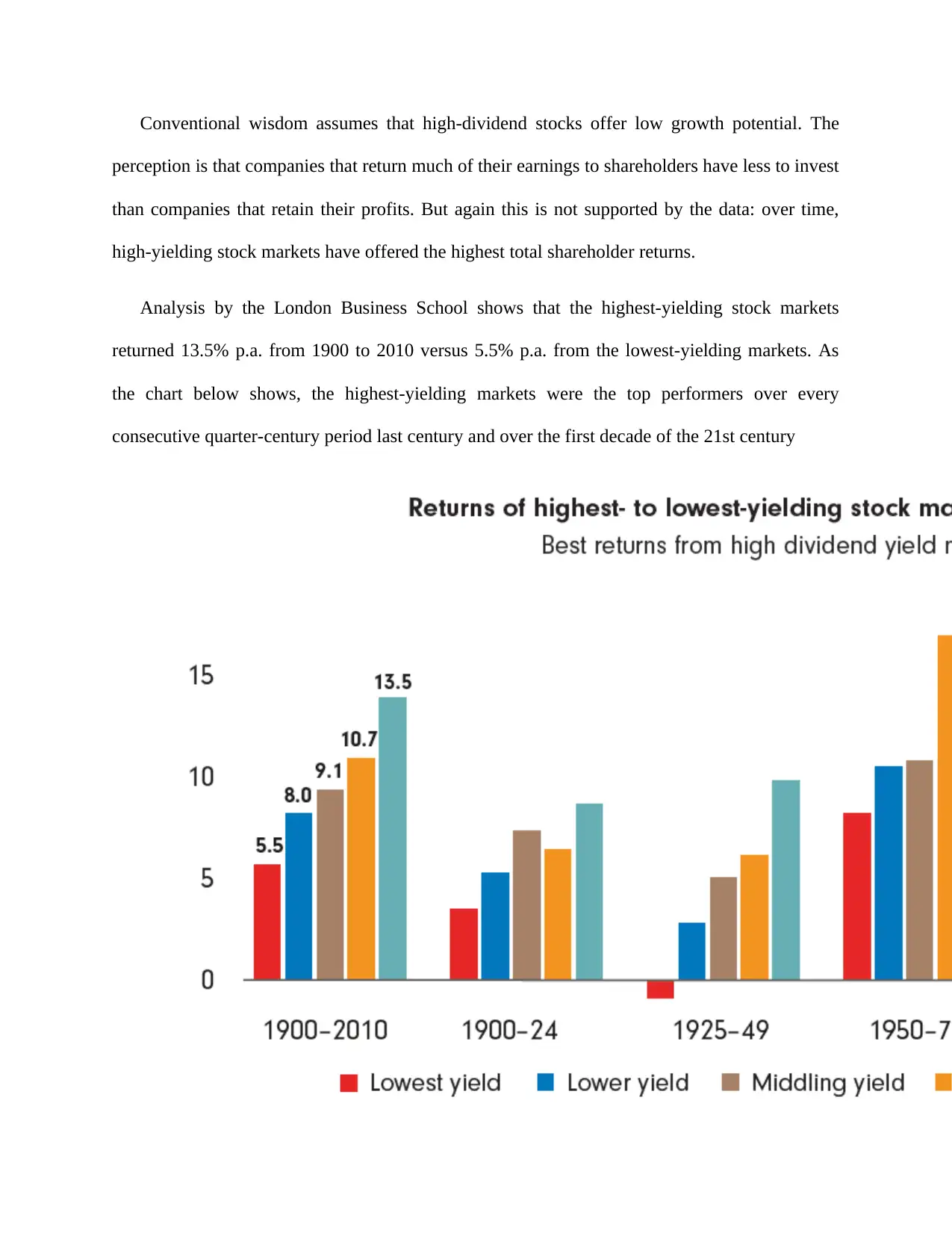

Australia’s experience post-franking has shown a continuation of this trend

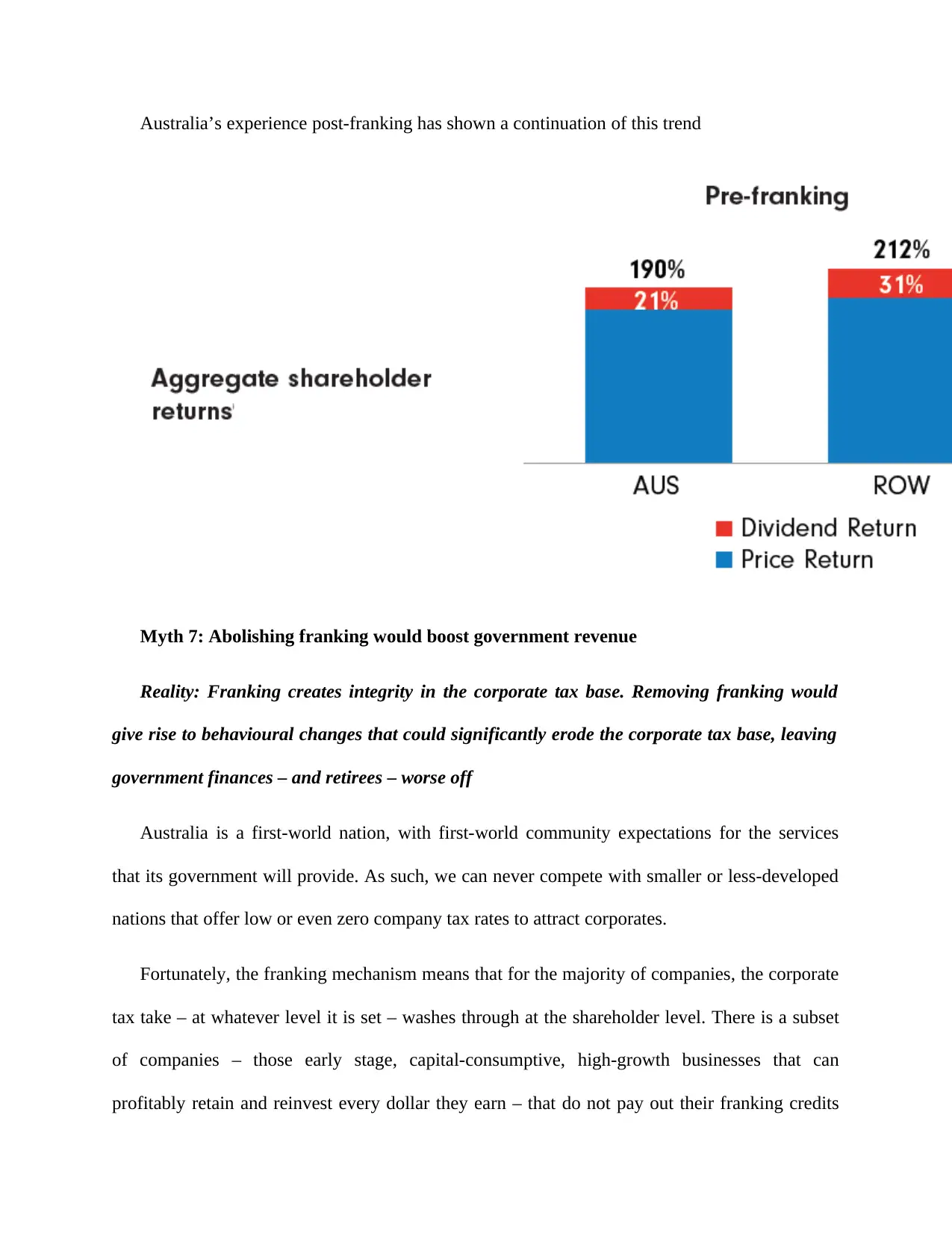

Myth 7: Abolishing franking would boost government revenue

Reality: Franking creates integrity in the corporate tax base. Removing franking would

give rise to behavioural changes that could significantly erode the corporate tax base, leaving

government finances – and retirees – worse off

Australia is a first-world nation, with first-world community expectations for the services

that its government will provide. As such, we can never compete with smaller or less-developed

nations that offer low or even zero company tax rates to attract corporates.

Fortunately, the franking mechanism means that for the majority of companies, the corporate

tax take – at whatever level it is set – washes through at the shareholder level. There is a subset

of companies – those early stage, capital-consumptive, high-growth businesses that can

profitably retain and reinvest every dollar they earn – that do not pay out their franking credits

Myth 7: Abolishing franking would boost government revenue

Reality: Franking creates integrity in the corporate tax base. Removing franking would

give rise to behavioural changes that could significantly erode the corporate tax base, leaving

government finances – and retirees – worse off

Australia is a first-world nation, with first-world community expectations for the services

that its government will provide. As such, we can never compete with smaller or less-developed

nations that offer low or even zero company tax rates to attract corporates.

Fortunately, the franking mechanism means that for the majority of companies, the corporate

tax take – at whatever level it is set – washes through at the shareholder level. There is a subset

of companies – those early stage, capital-consumptive, high-growth businesses that can

profitably retain and reinvest every dollar they earn – that do not pay out their franking credits

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

and thus would prefer a lower corporate tax rate. In theory, the risk is that these companies will

relocate to a more favourable tax locale. But tax is not the sole variable. We must ensure that

other policy settings (R&D tax settings, labour market flexibility, immigration flexibility, low

bureaucratic “red tape”, etc.) work together to make the Australian community a great place to

start – and grow – a business.

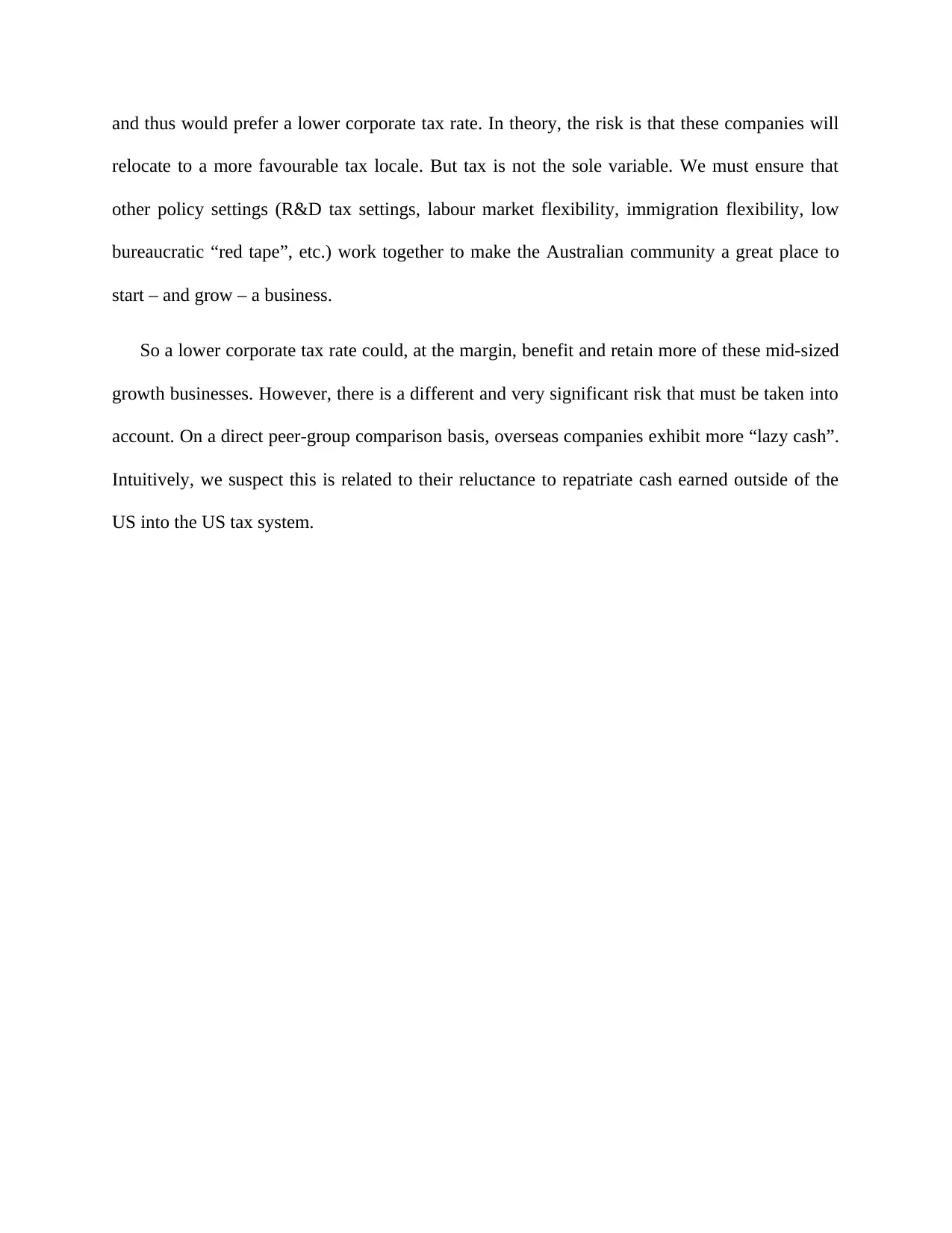

So a lower corporate tax rate could, at the margin, benefit and retain more of these mid-sized

growth businesses. However, there is a different and very significant risk that must be taken into

account. On a direct peer-group comparison basis, overseas companies exhibit more “lazy cash”.

Intuitively, we suspect this is related to their reluctance to repatriate cash earned outside of the

US into the US tax system.

relocate to a more favourable tax locale. But tax is not the sole variable. We must ensure that

other policy settings (R&D tax settings, labour market flexibility, immigration flexibility, low

bureaucratic “red tape”, etc.) work together to make the Australian community a great place to

start – and grow – a business.

So a lower corporate tax rate could, at the margin, benefit and retain more of these mid-sized

growth businesses. However, there is a different and very significant risk that must be taken into

account. On a direct peer-group comparison basis, overseas companies exhibit more “lazy cash”.

Intuitively, we suspect this is related to their reluctance to repatriate cash earned outside of the

US into the US tax system.

However for Australian companies, franking creates a strong incentive for local exporters to

etain a large tax liability within Australia, since franking credits are only generated on

Australian tax paid. Thus franking limits the scourge of tax minimisation that erodes the

corporate tax bases of other first-world nations. This highly beneficial incentive structure should

not be given up lightly

Myth 8: Franking disadvantages Australian companies that earn significant overseas

revenue

etain a large tax liability within Australia, since franking credits are only generated on

Australian tax paid. Thus franking limits the scourge of tax minimisation that erodes the

corporate tax bases of other first-world nations. This highly beneficial incentive structure should

not be given up lightly

Myth 8: Franking disadvantages Australian companies that earn significant overseas

revenue

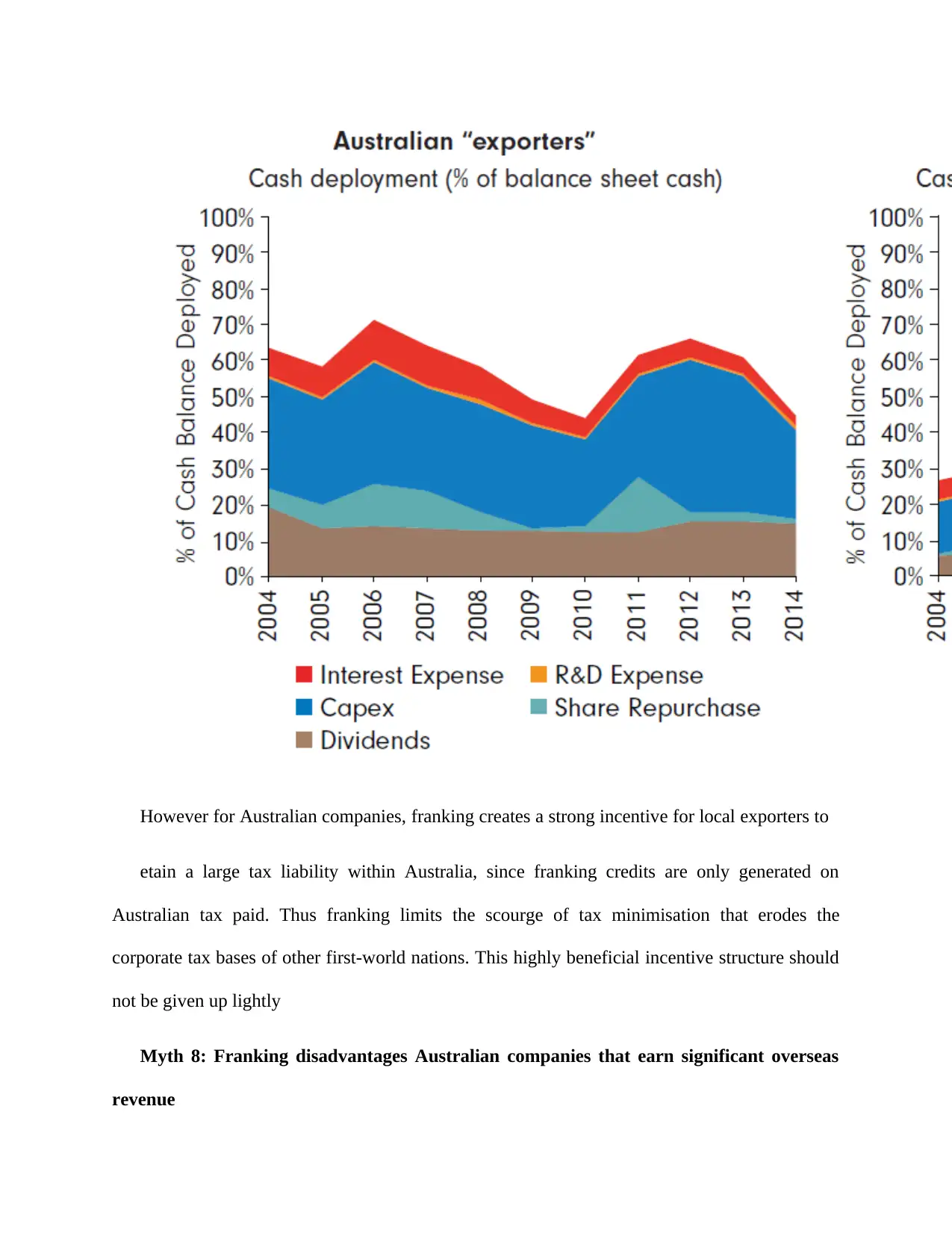

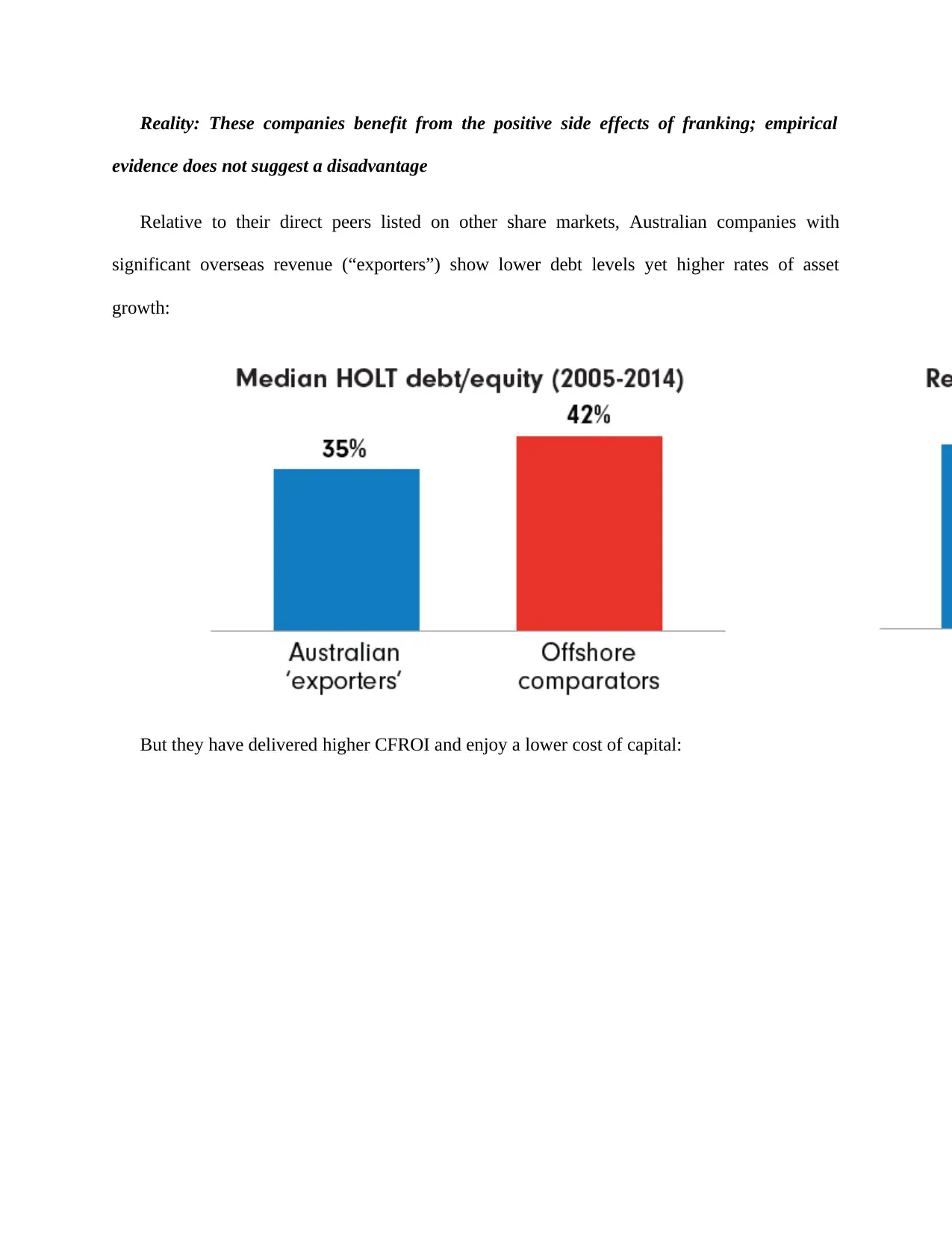

Reality: These companies benefit from the positive side effects of franking; empirical

evidence does not suggest a disadvantage

Relative to their direct peers listed on other share markets, Australian companies with

significant overseas revenue (“exporters”) show lower debt levels yet higher rates of asset

growth:

But they have delivered higher CFROI and enjoy a lower cost of capital:

evidence does not suggest a disadvantage

Relative to their direct peers listed on other share markets, Australian companies with

significant overseas revenue (“exporters”) show lower debt levels yet higher rates of asset

growth:

But they have delivered higher CFROI and enjoy a lower cost of capital:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

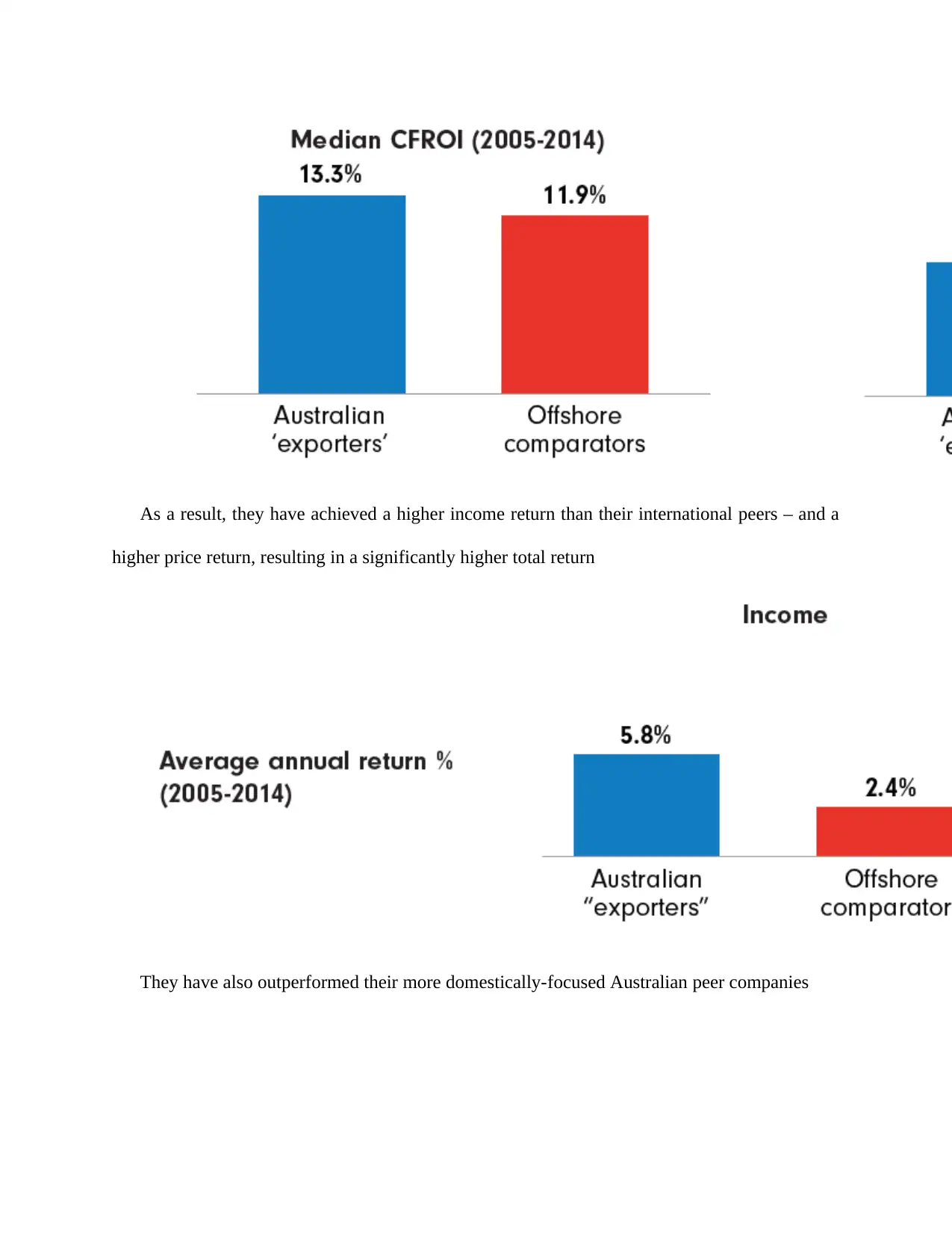

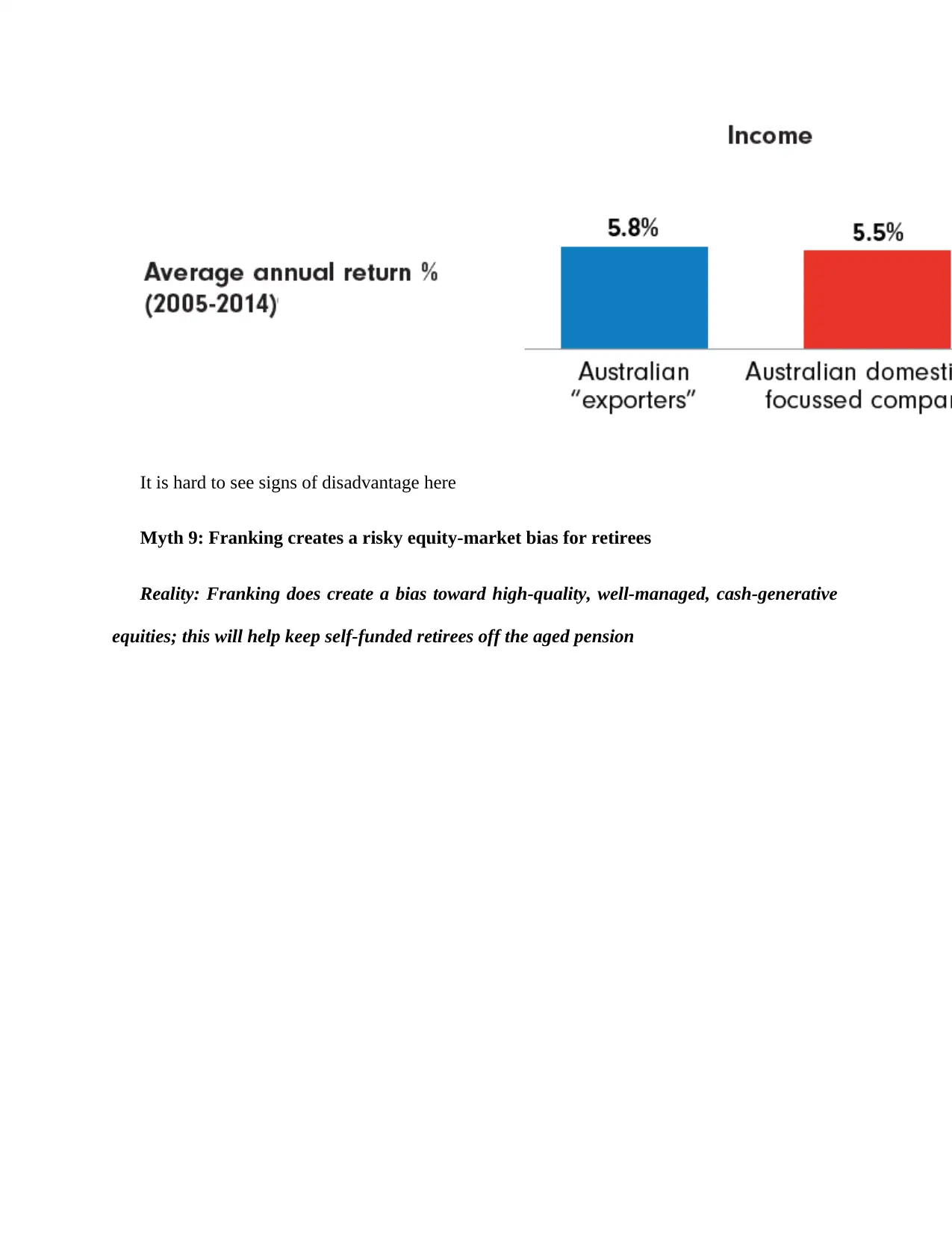

As a result, they have achieved a higher income return than their international peers – and a

higher price return, resulting in a significantly higher total return

They have also outperformed their more domestically-focused Australian peer companies

higher price return, resulting in a significantly higher total return

They have also outperformed their more domestically-focused Australian peer companies

It is hard to see signs of disadvantage here

Myth 9: Franking creates a risky equity-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking does create a bias toward high-quality, well-managed, cash-generative

equities; this will help keep self-funded retirees off the aged pension

Myth 9: Franking creates a risky equity-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking does create a bias toward high-quality, well-managed, cash-generative

equities; this will help keep self-funded retirees off the aged pension

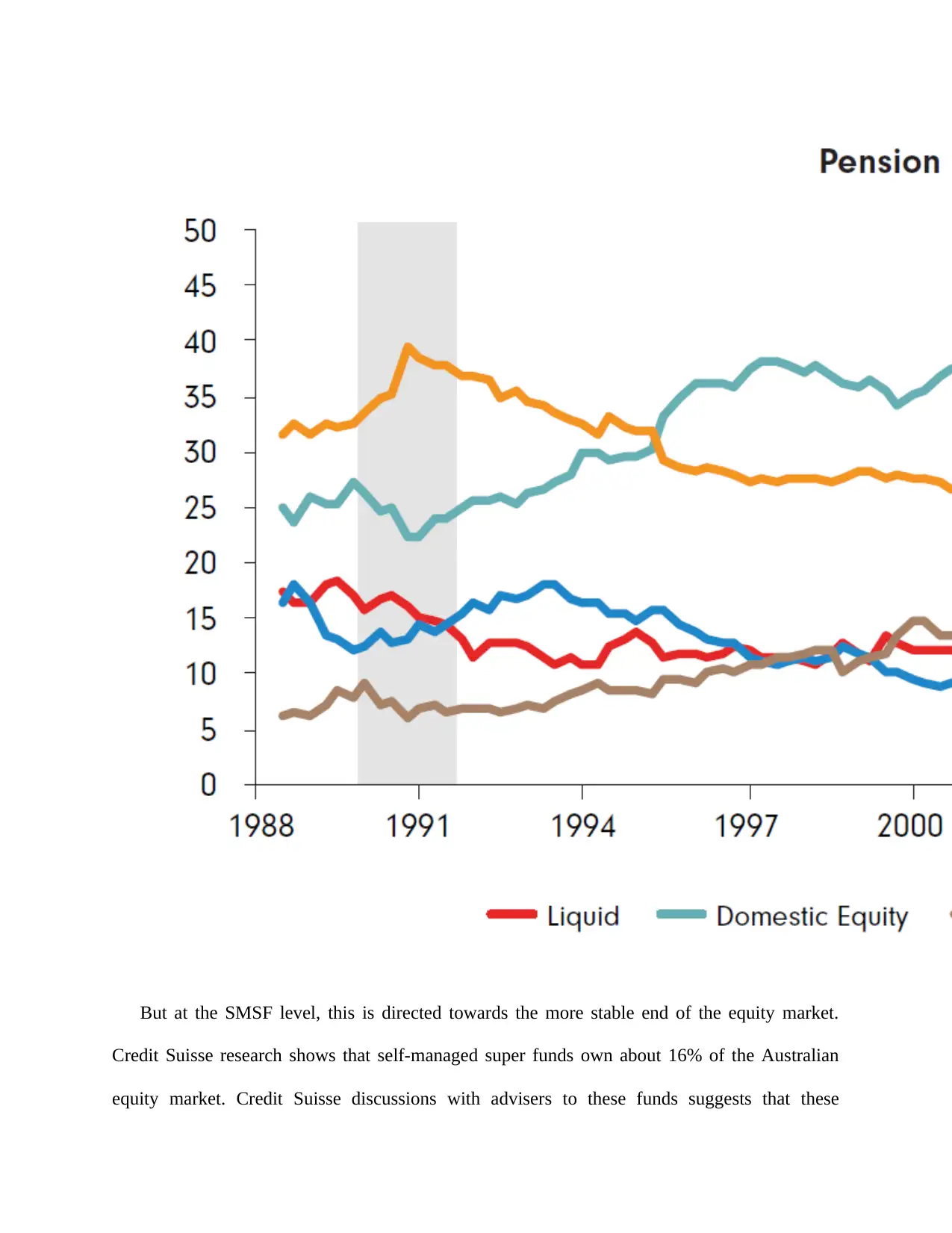

But at the SMSF level, this is directed towards the more stable end of the equity market.

Credit Suisse research shows that self-managed super funds own about 16% of the Australian

equity market. Credit Suisse discussions with advisers to these funds suggests that these

Credit Suisse research shows that self-managed super funds own about 16% of the Australian

equity market. Credit Suisse discussions with advisers to these funds suggests that these

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

investors want high-dividend yields from large companies they identify with and have a history

of dividend growth. They have a Tier-1 group of stocks that includes the big four banks and

Telstra. The equity-ownership incentive created by franking does not prompt investment at the

speculative end of the market, which lessens the risk of retirees experiencing permanent loss of

capital. This exposure to quality, cash-generative growth assets is likely to help retirees maintain

their purchasing power throughout an extended retirement, and avoid falling back on the aged

pension

Myth 10: Franking creates a risky home-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking results in well-managed, high-returning, lower-volatility companies that

are justifiably attractive to domestic and international investors

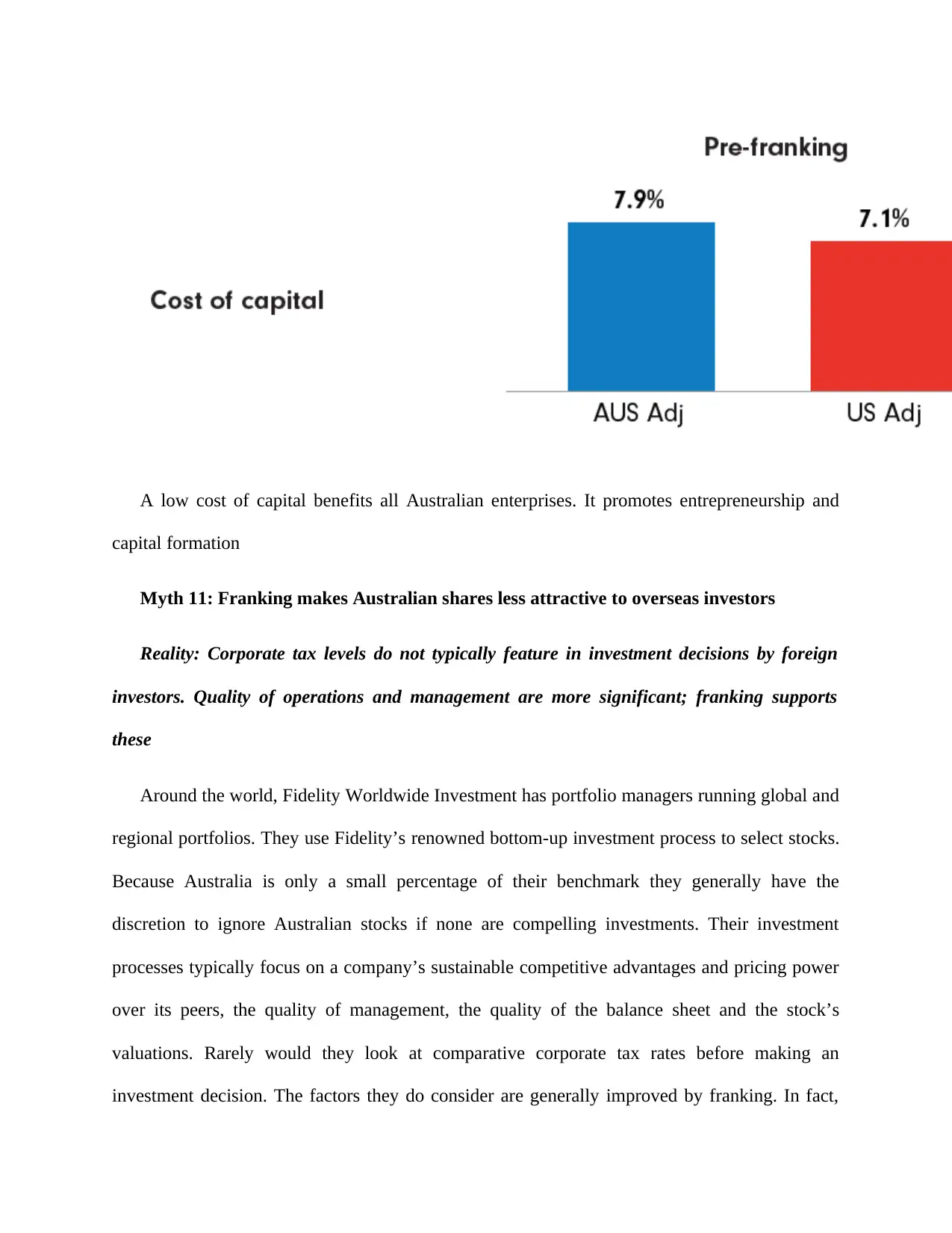

Franking constrains the reinvestment behaviour of Australian companies. This results in

leaner balance sheets, higher returns and lower volatility of returns. They are acutely aware of

the importance of maintaining sound balance sheets and of achieving high returns not just fast

growth. On the back of this – and deservedly for other reasons – Australian companies have

developed a reputation for being well-managed.

As a result of this, Australian companies are favoured by international institutional investors,

not just local retirees. This is evidenced by the cost of capital enjoyed by Australian companies,

which is in line with that experienced by US companies

of dividend growth. They have a Tier-1 group of stocks that includes the big four banks and

Telstra. The equity-ownership incentive created by franking does not prompt investment at the

speculative end of the market, which lessens the risk of retirees experiencing permanent loss of

capital. This exposure to quality, cash-generative growth assets is likely to help retirees maintain

their purchasing power throughout an extended retirement, and avoid falling back on the aged

pension

Myth 10: Franking creates a risky home-market bias for retirees

Reality: Franking results in well-managed, high-returning, lower-volatility companies that

are justifiably attractive to domestic and international investors

Franking constrains the reinvestment behaviour of Australian companies. This results in

leaner balance sheets, higher returns and lower volatility of returns. They are acutely aware of

the importance of maintaining sound balance sheets and of achieving high returns not just fast

growth. On the back of this – and deservedly for other reasons – Australian companies have

developed a reputation for being well-managed.

As a result of this, Australian companies are favoured by international institutional investors,

not just local retirees. This is evidenced by the cost of capital enjoyed by Australian companies,

which is in line with that experienced by US companies

A low cost of capital benefits all Australian enterprises. It promotes entrepreneurship and

capital formation

Myth 11: Franking makes Australian shares less attractive to overseas investors

Reality: Corporate tax levels do not typically feature in investment decisions by foreign

investors. Quality of operations and management are more significant; franking supports

these

Around the world, Fidelity Worldwide Investment has portfolio managers running global and

regional portfolios. They use Fidelity’s renowned bottom-up investment process to select stocks.

Because Australia is only a small percentage of their benchmark they generally have the

discretion to ignore Australian stocks if none are compelling investments. Their investment

processes typically focus on a company’s sustainable competitive advantages and pricing power

over its peers, the quality of management, the quality of the balance sheet and the stock’s

valuations. Rarely would they look at comparative corporate tax rates before making an

investment decision. The factors they do consider are generally improved by franking. In fact,

capital formation

Myth 11: Franking makes Australian shares less attractive to overseas investors

Reality: Corporate tax levels do not typically feature in investment decisions by foreign

investors. Quality of operations and management are more significant; franking supports

these

Around the world, Fidelity Worldwide Investment has portfolio managers running global and

regional portfolios. They use Fidelity’s renowned bottom-up investment process to select stocks.

Because Australia is only a small percentage of their benchmark they generally have the

discretion to ignore Australian stocks if none are compelling investments. Their investment

processes typically focus on a company’s sustainable competitive advantages and pricing power

over its peers, the quality of management, the quality of the balance sheet and the stock’s

valuations. Rarely would they look at comparative corporate tax rates before making an

investment decision. The factors they do consider are generally improved by franking. In fact,

because of tax certainty due to zero withholding tax on franked dividends, franking is actually a

simplifying factor for overseas investors. Perhaps the only time that tax would come into

consideration would be if a new tax, such as the recently proposed mining tax, was imminent or

corporate tax levels were to rise to a large extent. Australia’s dividend imputation system is a

non-issue for global equity investors.

3. Franking Credits – An all-inclusive overview

The process of investing undergoes a prior deep research based on fundamental analysis,

technical evaluation and macro-scenario analysis. But the concept does not end with the investor

risking his money on a lucrative stock. The most interesting part comes post investing, or after

the risk has been taken- the consequences. The fundamental rationale behind investing in equity

market is to earn profits and source out a stable form of income, and this happens through capital

appreciation as well as dividends.

Talking about dividends, we often come across corporate updates wherein the company has

offered franked dividends for quarterly/semi-annually/annually basis. Today, Material sector

player, Amcor PLC (ASX: AMC) has announced an unfranked quarterly dividend of AU

0.17725 cents per share. Iron ore giant, BHP recently announced fully franked final dividend of

US 78 cents/share. Several other companies have updated the market with their dividend payout

plans in the ongoing reporting season.

Today’s article would provide you with a holistic understanding of one of the dividend

constituents- Franking Credits. Let us dive right in:

simplifying factor for overseas investors. Perhaps the only time that tax would come into

consideration would be if a new tax, such as the recently proposed mining tax, was imminent or

corporate tax levels were to rise to a large extent. Australia’s dividend imputation system is a

non-issue for global equity investors.

3. Franking Credits – An all-inclusive overview

The process of investing undergoes a prior deep research based on fundamental analysis,

technical evaluation and macro-scenario analysis. But the concept does not end with the investor

risking his money on a lucrative stock. The most interesting part comes post investing, or after

the risk has been taken- the consequences. The fundamental rationale behind investing in equity

market is to earn profits and source out a stable form of income, and this happens through capital

appreciation as well as dividends.

Talking about dividends, we often come across corporate updates wherein the company has

offered franked dividends for quarterly/semi-annually/annually basis. Today, Material sector

player, Amcor PLC (ASX: AMC) has announced an unfranked quarterly dividend of AU

0.17725 cents per share. Iron ore giant, BHP recently announced fully franked final dividend of

US 78 cents/share. Several other companies have updated the market with their dividend payout

plans in the ongoing reporting season.

Today’s article would provide you with a holistic understanding of one of the dividend

constituents- Franking Credits. Let us dive right in:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Understanding Franking Credits

Often synonymously used as imputation credit, franking credit could be best described as the

type of tax credit which is paid to the shareholders by the company they would have invested in,

along with the dividend payments.

Franking credits could exist as a consequence of an entitlement to a franked distribution, when

the company is a beneficiary of a trust. The concept is fairly famous in Australia, with several

companies offering franking credits to eliminate or at least reduce any sort of double taxation,

depending on the investor’s tax bracket. Shareholders avail a reduction in their income taxes or

are granted a tax refund, as the company distributing the dividend, already pays the tax on them

and the franking credit allows the company to allocate a tax credit to their shareholders. In the

Australian context, a franking credit can be described as an entitlement, offered to the

shareholders by a company they would have invested in, to a reduction in personal income tax

which is payable to the Australian Taxation Office.

Australia, New Zealand and Malta have imputation systems, whereas countries like the UK,

Chile, Korea and Canada have a partial imputation system.

Breaking Down The Concept

Often synonymously used as imputation credit, franking credit could be best described as the

type of tax credit which is paid to the shareholders by the company they would have invested in,

along with the dividend payments.

Franking credits could exist as a consequence of an entitlement to a franked distribution, when

the company is a beneficiary of a trust. The concept is fairly famous in Australia, with several

companies offering franking credits to eliminate or at least reduce any sort of double taxation,

depending on the investor’s tax bracket. Shareholders avail a reduction in their income taxes or

are granted a tax refund, as the company distributing the dividend, already pays the tax on them

and the franking credit allows the company to allocate a tax credit to their shareholders. In the

Australian context, a franking credit can be described as an entitlement, offered to the

shareholders by a company they would have invested in, to a reduction in personal income tax

which is payable to the Australian Taxation Office.

Australia, New Zealand and Malta have imputation systems, whereas countries like the UK,

Chile, Korea and Canada have a partial imputation system.

Breaking Down The Concept

Often, you would have come across the term ‘franked’ when it comes to dividend distribution.

Dividends are paid out of the generated profits subject to the Australian Company Tax system,

which means that the shareholders are granted a rebate for the tax which is paid by the company

on the profits that are distributed in the form of dividends.

Let us take an example: Mr X is the owner of shares in a company, that pays him a fully franked

dividend of $800. The dividend statement states that a franking credit of $200 exists,

representing the tax amount on the dividend which the company would have paid. When Mr X

declares his personal income, he would state an amount of $1000, (which was the actual

dividend). If the tax rate was 15%, he would have paid $150 tax on the dividend, but as the

company has already paid the franking credit amount as tax, Mr X would receive a refund of

$50. In case Mr X was on a higher tax slab, he would not be entitled to avail a refund, rather he

would be paying extra tax. On the contrary, a lower bracket slab would lead to the possibility of

full refund.

History of Franking Credits

The concept of franking credits was brought into consideration in the late 1980s by the Hawke

Government, making it a relatively new area in the business line. The franking credit imputation

system has existed in Australia and its taxation system for approximately 30 years. In the

beginning, the franking credit system was granted exclusively for the offsets on the tax amount

paid. This was modified in 2001, which allowed the cash refund of the excess credits to

shareholders who had their tax liabilities lower than the refunded credits.

Dividends are paid out of the generated profits subject to the Australian Company Tax system,

which means that the shareholders are granted a rebate for the tax which is paid by the company

on the profits that are distributed in the form of dividends.

Let us take an example: Mr X is the owner of shares in a company, that pays him a fully franked

dividend of $800. The dividend statement states that a franking credit of $200 exists,

representing the tax amount on the dividend which the company would have paid. When Mr X

declares his personal income, he would state an amount of $1000, (which was the actual

dividend). If the tax rate was 15%, he would have paid $150 tax on the dividend, but as the

company has already paid the franking credit amount as tax, Mr X would receive a refund of

$50. In case Mr X was on a higher tax slab, he would not be entitled to avail a refund, rather he

would be paying extra tax. On the contrary, a lower bracket slab would lead to the possibility of

full refund.

History of Franking Credits

The concept of franking credits was brought into consideration in the late 1980s by the Hawke

Government, making it a relatively new area in the business line. The franking credit imputation

system has existed in Australia and its taxation system for approximately 30 years. In the

beginning, the franking credit system was granted exclusively for the offsets on the tax amount

paid. This was modified in 2001, which allowed the cash refund of the excess credits to

shareholders who had their tax liabilities lower than the refunded credits.

Benefits of Franking Credits

The concept, even though is new, has proven its advantages for both companies and

shareholders. Some of these are mentioned below:

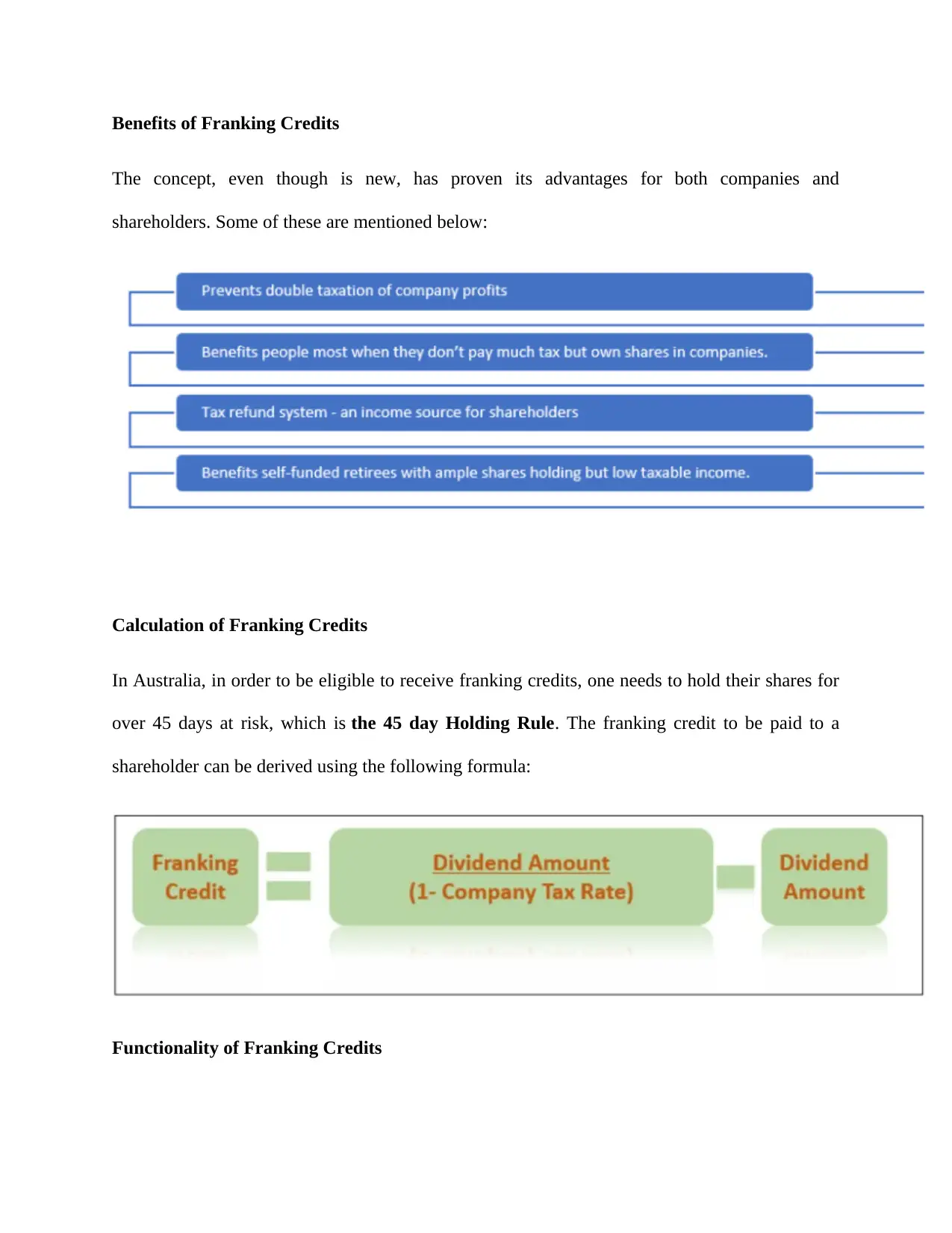

Calculation of Franking Credits

In Australia, in order to be eligible to receive franking credits, one needs to hold their shares for

over 45 days at risk, which is the 45 day Holding Rule. The franking credit to be paid to a

shareholder can be derived using the following formula:

Functionality of Franking Credits

The concept, even though is new, has proven its advantages for both companies and

shareholders. Some of these are mentioned below:

Calculation of Franking Credits

In Australia, in order to be eligible to receive franking credits, one needs to hold their shares for

over 45 days at risk, which is the 45 day Holding Rule. The franking credit to be paid to a

shareholder can be derived using the following formula:

Functionality of Franking Credits

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The franking credit is attached to a dividend which the company pays to shareholders out of its

after-tax profits. Its worth is the same as the amount of tax which is paid on the individual’s

share from the profit generated by the company, before it was distributed as a dividend. Intended

to shun down or remove the double taxation concept, because the tax on dividends is already

been paid by the company, when personal income tax is computed for the individual, the value of

their accrued franking credits can be subtracted from the tax payable.

A company can differ from the another in the way that it deals with franking credits, depending

upon the amount of tax they have paid. It should be noted here that the company cannot offer a

franking credit exceeding an amount that is paid in company tax, and they cannot offer the

franking credit for tax that has been paid in a foreign country. In the context of Australia, this

means that the benefit of franking credit is exclusively available to Aussie residents and cannot

be claimed by the foreign proprietors of the Aussie companies.

Franking Credits On The ASX

As per a report from the Australian Securities Exchange, in the S&P/ASX 200 index, which

marks the 200 biggest players of the Australian equity market, 184 companies had paid

dividends in the 52 weeks to 19 April 2018. Of these companies, half granted fully franked

dividends and around a fourth paid semi-franked dividends and unfranked dividends. The highest

franking balances on the market included (in no particular order) Commonwealth Bank of

Australia (ASX: CBA), BHP Billiton Limited (ASX: BHP), Westpac Banking Corporation

(ASX: WBC), Woolworths Group Limited (ASX: WOW) and TPG telecom Limited (ASX:

TPM).

Key Takeaways:

after-tax profits. Its worth is the same as the amount of tax which is paid on the individual’s

share from the profit generated by the company, before it was distributed as a dividend. Intended

to shun down or remove the double taxation concept, because the tax on dividends is already

been paid by the company, when personal income tax is computed for the individual, the value of

their accrued franking credits can be subtracted from the tax payable.

A company can differ from the another in the way that it deals with franking credits, depending

upon the amount of tax they have paid. It should be noted here that the company cannot offer a

franking credit exceeding an amount that is paid in company tax, and they cannot offer the

franking credit for tax that has been paid in a foreign country. In the context of Australia, this

means that the benefit of franking credit is exclusively available to Aussie residents and cannot

be claimed by the foreign proprietors of the Aussie companies.

Franking Credits On The ASX

As per a report from the Australian Securities Exchange, in the S&P/ASX 200 index, which

marks the 200 biggest players of the Australian equity market, 184 companies had paid

dividends in the 52 weeks to 19 April 2018. Of these companies, half granted fully franked

dividends and around a fourth paid semi-franked dividends and unfranked dividends. The highest

franking balances on the market included (in no particular order) Commonwealth Bank of

Australia (ASX: CBA), BHP Billiton Limited (ASX: BHP), Westpac Banking Corporation

(ASX: WBC), Woolworths Group Limited (ASX: WOW) and TPG telecom Limited (ASX:

TPM).

Key Takeaways:

Imputation credit or franking credit is the type of tax credit which is paid to the

shareholders by the company along with the dividend payments to avoid double taxation.

The concept of franking credits was brought into consideration in the late 1980s by the

Hawke Government

In Australia, in order to be eligible to receive franking credits, one needs to hold their

shares at risk for over 45 days at risk, which is the ‘45 day Holding Rule’.

A company cannot offer a franking credit exceeding an amount that is paid in company

tax, and they cannot offer the franking credit for tax that has been paid in a foreign

country.

4. Labor's tax policies 'highly progressive' with top 20% feeling most impact

A new analysis of Labor’s tax policies says the proposed overhaul of franking credits,

changes to negative gearing, trusts and capital gains tax if Bill Shorten wins the election on

18 May will have a negligible impact on the bottom 50% of households in Australia

measured by income and wealth.

While the Morrison government has played up the negative impact of revenue measures,

particularly franking credits, on self-funded retirees with modest incomes, the distributional

analysis of Labor’s tax measures by the Australian National University’s Centre for Social

Research and Methods says that’s largely bunkum.

shareholders by the company along with the dividend payments to avoid double taxation.

The concept of franking credits was brought into consideration in the late 1980s by the

Hawke Government

In Australia, in order to be eligible to receive franking credits, one needs to hold their

shares at risk for over 45 days at risk, which is the ‘45 day Holding Rule’.

A company cannot offer a franking credit exceeding an amount that is paid in company

tax, and they cannot offer the franking credit for tax that has been paid in a foreign

country.

4. Labor's tax policies 'highly progressive' with top 20% feeling most impact

A new analysis of Labor’s tax policies says the proposed overhaul of franking credits,

changes to negative gearing, trusts and capital gains tax if Bill Shorten wins the election on

18 May will have a negligible impact on the bottom 50% of households in Australia

measured by income and wealth.

While the Morrison government has played up the negative impact of revenue measures,

particularly franking credits, on self-funded retirees with modest incomes, the distributional

analysis of Labor’s tax measures by the Australian National University’s Centre for Social

Research and Methods says that’s largely bunkum.

“Franking credits benefit households in the top 20% of income and wealth distribution

considerably more than other households,” the analysis says. “While these households often

have low taxable incomes, they tend to have large wealth balances or be in households with

high incomes, even when the individual affected has a low income.”

The ANU academics, led by economic and social researcher Ben Phillips, modelled Labor’s

changes to dividend imputation, negative gearing and capital gains tax, the reinstatement of

the budget levy, the low and middle-income tax offset, new personal income tax rates and

thresholds, and the taxation of trusts.

The overall impact of the proposed changes was highly progressive, “with virtually no

impact for households in the bottom 40% of the income distribution and the largest increase

for those in the top 10%”.

“In raw dollar terms, the top 20% account for around 70% of the fiscal impact with a loss of

disposable income of around $17bn out of around $25bn in increased revenue under Labor.”

The ANU analysis says the top income decile will see an average loss of disposable income

of $11,877 per year under Labor compared with the 2019 budget handed down by the

Morrison government just prior to the election – which compares to reduction in income for

the bottom five deciles of below 1%.

considerably more than other households,” the analysis says. “While these households often

have low taxable incomes, they tend to have large wealth balances or be in households with

high incomes, even when the individual affected has a low income.”

The ANU academics, led by economic and social researcher Ben Phillips, modelled Labor’s

changes to dividend imputation, negative gearing and capital gains tax, the reinstatement of

the budget levy, the low and middle-income tax offset, new personal income tax rates and

thresholds, and the taxation of trusts.

The overall impact of the proposed changes was highly progressive, “with virtually no

impact for households in the bottom 40% of the income distribution and the largest increase

for those in the top 10%”.

“In raw dollar terms, the top 20% account for around 70% of the fiscal impact with a loss of

disposable income of around $17bn out of around $25bn in increased revenue under Labor.”

The ANU analysis says the top income decile will see an average loss of disposable income

of $11,877 per year under Labor compared with the 2019 budget handed down by the

Morrison government just prior to the election – which compares to reduction in income for

the bottom five deciles of below 1%.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

On franking credits, the analysis says the largest impact in dollar terms and as a percentage

of disposable income of Labor’s policy falls on the top 10%.

The top 10% would, on average, pay $2,641 a year, or 1.1% of disposable income, if Labor

wins and franking credits are removed. It says there is “virtually no impact” on low income

groups in the bottom half of the income distribution. It says 600,000 households are

negatively affected by the removal of franking credits.

The study also indicates Labor will have room to move fiscally to increase the Newstart

allowance by $75 per week for singles, at a cost of around $3bn per year.

The new ANU analysis comes as the shadow treasurer, Chris Bowen, accused “vested

interests” of attempting to influence the election outcome, taking aim at the Real Estate

Institute of Australia for campaigning against proposed negative gearing and capital gains tax

changes.

REIA has boasted that its campaign, assisted by its network of real estate agents, has reached

nearly 8 million Australians.

of disposable income of Labor’s policy falls on the top 10%.

The top 10% would, on average, pay $2,641 a year, or 1.1% of disposable income, if Labor

wins and franking credits are removed. It says there is “virtually no impact” on low income

groups in the bottom half of the income distribution. It says 600,000 households are

negatively affected by the removal of franking credits.

The study also indicates Labor will have room to move fiscally to increase the Newstart

allowance by $75 per week for singles, at a cost of around $3bn per year.

The new ANU analysis comes as the shadow treasurer, Chris Bowen, accused “vested

interests” of attempting to influence the election outcome, taking aim at the Real Estate

Institute of Australia for campaigning against proposed negative gearing and capital gains tax

changes.

REIA has boasted that its campaign, assisted by its network of real estate agents, has reached

nearly 8 million Australians.

Campaign catchup 2019: leaders on the home straight

Read more

“This is part of a concerted effort by a select group of property interest groups to decide an

election outcome and Australians should be alive to it,” Bowen said. “The REIA’s

irresponsible claims are just downright lies.

“Labor’s housing affordability reforms will our first home buyers on a level playing field

with property investors and importantly, give renters saving for their first home a chance.”

In a letter sent to tenants, REIA warns that “rents will go up” under Labor’s policy.

“Because you’re currently renting, it might be tempting to dismiss the latest political battle

over whether negative gearing should be abolished. You might even see it as a good thing if

house prices go down, but rents will rise”.

5. If franking credits and negative gearing didn’t exist, no one would invent them

Read more

“This is part of a concerted effort by a select group of property interest groups to decide an

election outcome and Australians should be alive to it,” Bowen said. “The REIA’s

irresponsible claims are just downright lies.

“Labor’s housing affordability reforms will our first home buyers on a level playing field

with property investors and importantly, give renters saving for their first home a chance.”

In a letter sent to tenants, REIA warns that “rents will go up” under Labor’s policy.

“Because you’re currently renting, it might be tempting to dismiss the latest political battle

over whether negative gearing should be abolished. You might even see it as a good thing if

house prices go down, but rents will rise”.

5. If franking credits and negative gearing didn’t exist, no one would invent them

abor’s plans to unwind refundable franking credits and negative gearing are the most

controversial tax changes taken to an election since John Howard’s GST two decades

ago. There’s plenty of opposition from retirees on yachts pointing to the

thousands of dollars they’ll lose in franking credits, and the property lobby is warning

of a housing crash if negative gearing is changed.

But let’s think about it another way. Imagine that refundable franking credits and

negative gearing didn’t exist, and instead the Coalition was promising to introduce

them. How might the debate be different?

First, instead of simply pointing to people who lose from their removal, the

Coalition would have to explain why these policies should exist in the first place.

That’s a much harder ask.

The Coalition would no doubt rely on some standard tax policy principles. The basic

principle of franking credits is that company tax is simply paid on behalf of

shareholders, at each shareholder’s marginal personal income tax rate. And so any

unused franking credits are in effect an overpayment of prepaid tax, and should be

returned via a cheque from the government.

In addition, it would point to the unfairness of retirees in self-managed super funds

being denied (non-refundable) franking credits, whereas retirees in industry and retail

super funds can get the benefits because their credits can be used to offset the tax of

younger members who are taxed on their contributions and fund earnings.

In arguing for negative gearing, the Coalition would presumably point to the standard

principle that losses should be offset against income before it’s taxed. Tax

experts would quibble that any losses would be deducted in full, while only half

the capital gains are taxed.

But such arguments from principle are rarely enough to win a tax debate. Theoretical

purity is all well and good, but there are plenty of other considerations that take into

account how things work out in practice. And here the case would become much

harder to make.

controversial tax changes taken to an election since John Howard’s GST two decades

ago. There’s plenty of opposition from retirees on yachts pointing to the

thousands of dollars they’ll lose in franking credits, and the property lobby is warning

of a housing crash if negative gearing is changed.

But let’s think about it another way. Imagine that refundable franking credits and

negative gearing didn’t exist, and instead the Coalition was promising to introduce

them. How might the debate be different?

First, instead of simply pointing to people who lose from their removal, the

Coalition would have to explain why these policies should exist in the first place.

That’s a much harder ask.

The Coalition would no doubt rely on some standard tax policy principles. The basic

principle of franking credits is that company tax is simply paid on behalf of

shareholders, at each shareholder’s marginal personal income tax rate. And so any

unused franking credits are in effect an overpayment of prepaid tax, and should be

returned via a cheque from the government.

In addition, it would point to the unfairness of retirees in self-managed super funds

being denied (non-refundable) franking credits, whereas retirees in industry and retail

super funds can get the benefits because their credits can be used to offset the tax of

younger members who are taxed on their contributions and fund earnings.

In arguing for negative gearing, the Coalition would presumably point to the standard

principle that losses should be offset against income before it’s taxed. Tax

experts would quibble that any losses would be deducted in full, while only half

the capital gains are taxed.

But such arguments from principle are rarely enough to win a tax debate. Theoretical

purity is all well and good, but there are plenty of other considerations that take into

account how things work out in practice. And here the case would become much

harder to make.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Retirees might question why the government should send cheques for $6 billion a

year to the wealthiest Australians, instead of doing more to help pensioners,

especially renters, at risk of poverty and financial stress in retirement.

After all, more than half the benefits of refundable franking credits for self-managed

super funds go to funds with balances of $2.4 million or more. And shareholdings

among over-sixty-fives outside super are also highly skewed towards the wealthy: the

richest 20 per cent of households over sixty-five own 86 per cent of the shares held

directly, while the poorest half of all retirees own less than 2 per cent.

Others would question whether the budget can afford such giveaways, especially

when fifteen years of intergenerational reports have warned us of the long-term

budgetary threat from the ageing of the population. Are refundable franking credits

really appropriate when fewer than one in six retirees pay any income tax?

Are they affordable if they lead to the average retired household with $100,000 in

income a year paying the same amount of tax as a working household earning

$50,000?

With negative gearing, we’d be debating whether it’s really a priority to spend

between $1 billion and $2 billion a year of taxpayers’ money on tax breaks for

housing investors, especially when most investors would simply purchase existing

properties. Voters might also be worried by projections showing that negative gearing

would push down home ownership as negatively geared investors outbid first

homebuyers at auctions.

And how would the public weigh these policies compared with their alternatives?

The $6 billion annual savings on refundable franking credits would be enough to fund

a 40 per cent increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance for all

income-support recipients ($1.2 billion) and relax the taper rate on the age

pension assets test ($750 million a year), with plenty left over to shore up the budget

against the long-term costs of an ageing population.

And if we’re serious about boosting housing construction, $1 billion in incentive

payments to state governments to reform land-use planning rules and get

year to the wealthiest Australians, instead of doing more to help pensioners,

especially renters, at risk of poverty and financial stress in retirement.

After all, more than half the benefits of refundable franking credits for self-managed

super funds go to funds with balances of $2.4 million or more. And shareholdings

among over-sixty-fives outside super are also highly skewed towards the wealthy: the

richest 20 per cent of households over sixty-five own 86 per cent of the shares held

directly, while the poorest half of all retirees own less than 2 per cent.

Others would question whether the budget can afford such giveaways, especially

when fifteen years of intergenerational reports have warned us of the long-term

budgetary threat from the ageing of the population. Are refundable franking credits

really appropriate when fewer than one in six retirees pay any income tax?

Are they affordable if they lead to the average retired household with $100,000 in

income a year paying the same amount of tax as a working household earning

$50,000?

With negative gearing, we’d be debating whether it’s really a priority to spend

between $1 billion and $2 billion a year of taxpayers’ money on tax breaks for

housing investors, especially when most investors would simply purchase existing

properties. Voters might also be worried by projections showing that negative gearing

would push down home ownership as negatively geared investors outbid first

homebuyers at auctions.

And how would the public weigh these policies compared with their alternatives?

The $6 billion annual savings on refundable franking credits would be enough to fund

a 40 per cent increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance for all

income-support recipients ($1.2 billion) and relax the taper rate on the age

pension assets test ($750 million a year), with plenty left over to shore up the budget

against the long-term costs of an ageing population.

And if we’re serious about boosting housing construction, $1 billion in incentive

payments to state governments to reform land-use planning rules and get

more housing built in the inner and middle suburbs of our major cities would be far

more effective.

Of course, the big difference between this imagined world and real life is that we

wouldn’t have a cacophony of special interest groups arguing so loudly to keep

refundable franking credits and negative gearing.

People prefer what they know, and like keeping what they have. These biases are

powerful allies for those defending bad policies. Take them away, and the case for

change becomes clearer.

The reality is that no major party would be able to defend introducing these policies

today. And if you can’t make that case, we should worry less about abolishing them. •

6. Do Franking Credits Matter? Exploring the Financial Implications of Dividend

Imputation

1. Executive Summary Questions have been raised over the efficacy of the dividend imputation

system, including by the Financial System Inquiry in November 2014 and the Tax Discussion

Paper released on 30 March, 2015. We aim to contribute to the policy debate by examining the

financial implications of the imputation system for markets, companies and investors. We

address the impact of dividend imputation for stock prices and returns, cost of capital, project

evaluation, capital structure, payout policy and investor portfolios. We also discuss potential

impacts if the imputation system was dismantled or adjusted, perhaps in conjunction with a

reduction in the corporate tax rate. This report draws on the literature and available evidence to

identify the issues, and offer some novel perspectives. Key Findings 1. The effects of imputation

are debatable both in theory and practice along most dimensions. The implications of imputation

for stock prices and returns, cost of capital, capital structure and investor portfolios are all

unclear. The notable exception is payout policy, where higher payout ratios have clearly been

encouraged by the desire to distribute imputation credits. 2. Whether imputation is priced into the

more effective.

Of course, the big difference between this imagined world and real life is that we

wouldn’t have a cacophony of special interest groups arguing so loudly to keep

refundable franking credits and negative gearing.

People prefer what they know, and like keeping what they have. These biases are

powerful allies for those defending bad policies. Take them away, and the case for

change becomes clearer.

The reality is that no major party would be able to defend introducing these policies

today. And if you can’t make that case, we should worry less about abolishing them. •

6. Do Franking Credits Matter? Exploring the Financial Implications of Dividend

Imputation

1. Executive Summary Questions have been raised over the efficacy of the dividend imputation

system, including by the Financial System Inquiry in November 2014 and the Tax Discussion

Paper released on 30 March, 2015. We aim to contribute to the policy debate by examining the

financial implications of the imputation system for markets, companies and investors. We

address the impact of dividend imputation for stock prices and returns, cost of capital, project

evaluation, capital structure, payout policy and investor portfolios. We also discuss potential

impacts if the imputation system was dismantled or adjusted, perhaps in conjunction with a

reduction in the corporate tax rate. This report draws on the literature and available evidence to

identify the issues, and offer some novel perspectives. Key Findings 1. The effects of imputation

are debatable both in theory and practice along most dimensions. The implications of imputation

for stock prices and returns, cost of capital, capital structure and investor portfolios are all

unclear. The notable exception is payout policy, where higher payout ratios have clearly been

encouraged by the desire to distribute imputation credits. 2. Whether imputation is priced into the

market is a central issue. Unfortunately, both theory and evidence provide very mixed

indications, and there is no consensus. The effects of imputation can be seen in share price

movements around dividend events, but are not readily apparent in returns or price levels.

Against this mixed evidence, the Tax Discussion Paper stance that the cost of capital is set in

international markets stands as an extreme position. Allowance should be made for the

possibility that imputation might be priced partially, or even fully, in some situations. 3. One

area where imputation probably matters is small, domestic companies. It is the smaller, domestic

segment where it is more likely that local investors who value imputation credits may determine

prices, as well as being chiefly responsible for providing funding. Any adverse impact from

removing imputation may well be concentrated in this (economically significant) segment. 4.

How imputation influences behaviour is important. Focusing on how imputation impacts on

precise computations like cost of capital estimates is arguably less important than understanding

the behaviours that imputation encourages, and how these might change if the imputation system

was adjusted. Investors and company management often do not formally build the value of

imputation into share price valuations, cost of capital estimates, or evaluations of investment

projects. Nevertheless, these players may still acknowledge that imputation credits are valuable

to many shareholders, and behave accordingly. Imputation can thus have an important influence

on some decisions, even though it may not be explicitly incorporated into any supportive

analysis. 5. The relation between imputation and payout policy deserves attention. The

contribution of the imputation system to lifting payout ratios has arguably been one of its key

effects and main benefits. By encouraging greater payouts, and thus requiring companies to

justify their case when seeking additional funding, the imputation system has probably

contributed to more disciplined use of capital. From this perspective, dismantling the imputation

indications, and there is no consensus. The effects of imputation can be seen in share price

movements around dividend events, but are not readily apparent in returns or price levels.

Against this mixed evidence, the Tax Discussion Paper stance that the cost of capital is set in

international markets stands as an extreme position. Allowance should be made for the

possibility that imputation might be priced partially, or even fully, in some situations. 3. One

area where imputation probably matters is small, domestic companies. It is the smaller, domestic

segment where it is more likely that local investors who value imputation credits may determine

prices, as well as being chiefly responsible for providing funding. Any adverse impact from

removing imputation may well be concentrated in this (economically significant) segment. 4.

How imputation influences behaviour is important. Focusing on how imputation impacts on

precise computations like cost of capital estimates is arguably less important than understanding

the behaviours that imputation encourages, and how these might change if the imputation system

was adjusted. Investors and company management often do not formally build the value of

imputation into share price valuations, cost of capital estimates, or evaluations of investment

projects. Nevertheless, these players may still acknowledge that imputation credits are valuable

to many shareholders, and behave accordingly. Imputation can thus have an important influence

on some decisions, even though it may not be explicitly incorporated into any supportive

analysis. 5. The relation between imputation and payout policy deserves attention. The

contribution of the imputation system to lifting payout ratios has arguably been one of its key

effects and main benefits. By encouraging greater payouts, and thus requiring companies to

justify their case when seeking additional funding, the imputation system has probably

contributed to more disciplined use of capital. From this perspective, dismantling the imputation

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

system could have detrimental effects for both shareholders and the Australian economy through

less efficient deployment of capital. 6. Imputation may not have much impact on corporate

capital structure or investment decisions. The link between imputation and both capital structure

and project evaluation is tenuous. The case is stronger for a relation with capital structure, given

that imputation increases the net return available to many shareholders. However, linking

imputation to capital structure requires companies to be concerned with personal tax effects

when making funding decisions; which are www.cifr.edu.au Page 4 one of many potential

influences on capital structure identified in the literature. When estimating cost of capital and

evaluating projects, the evidence suggests that few companies take imputation into account.

Rather, corporate investment decisions appear primarily based on more subjective

considerations, with financial analysis providing a supportive role. 7. Imputation is influential in

regulatory decisions. Regulation of utilities is one area where the value of imputation is

explicitly built into the computations, and has real effects in terms of output prices. The impact

of changes in imputation on utility prices should be given specific consideration in

contemplating any policy changes. 8. The influence of imputation on investor portfolios is

unclear; but any resulting domestic bias should not be a major policy concern. Home bias is

observed everywhere around the world, and has many potential explanations. The degree of

home bias among Australian investors does not seem untoward, except perhaps in the Self-

Managed Superannuation Fund sector. Further, just because a portfolio fails to reflect the

available asset universe does not necessarily mean that it is exposed to significant and

unwarranted non-diversifiable risk: the bulk of diversification opportunities can be secured with

a just a few assets. We see no significant danger to the Australian economy or financial system

from having a bias towards Australian equities paying high fullyfranked dividends. In any case,

less efficient deployment of capital. 6. Imputation may not have much impact on corporate

capital structure or investment decisions. The link between imputation and both capital structure

and project evaluation is tenuous. The case is stronger for a relation with capital structure, given

that imputation increases the net return available to many shareholders. However, linking

imputation to capital structure requires companies to be concerned with personal tax effects

when making funding decisions; which are www.cifr.edu.au Page 4 one of many potential

influences on capital structure identified in the literature. When estimating cost of capital and

evaluating projects, the evidence suggests that few companies take imputation into account.

Rather, corporate investment decisions appear primarily based on more subjective

considerations, with financial analysis providing a supportive role. 7. Imputation is influential in

regulatory decisions. Regulation of utilities is one area where the value of imputation is

explicitly built into the computations, and has real effects in terms of output prices. The impact

of changes in imputation on utility prices should be given specific consideration in

contemplating any policy changes. 8. The influence of imputation on investor portfolios is

unclear; but any resulting domestic bias should not be a major policy concern. Home bias is

observed everywhere around the world, and has many potential explanations. The degree of

home bias among Australian investors does not seem untoward, except perhaps in the Self-

Managed Superannuation Fund sector. Further, just because a portfolio fails to reflect the

available asset universe does not necessarily mean that it is exposed to significant and

unwarranted non-diversifiable risk: the bulk of diversification opportunities can be secured with

a just a few assets. We see no significant danger to the Australian economy or financial system

from having a bias towards Australian equities paying high fullyfranked dividends. In any case,

it is doubtful that this bias could be substantially addressed through changes to the imputation