Detailed Review: Chaney's Network Structure of International Trade

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|35

|22551

|199

Literature Review

AI Summary

This paper reviews Thomas Chaney's 'The Network Structure of International Trade,' published in the American Economic Review in 2014. The study introduces a novel theory of trade frictions, emphasizing the role of informational networks in international trade. Motivated by empirical evidence from French firms' exports, Chaney proposes that firms export only to markets where they have a contact, searching directly and remotely for new trading partners through their existing network. The model characterizes the dynamic formation of an international exporter network and is structurally estimated using French data, confirming predictions about the distribution of foreign markets accessed and the geographic distribution of exports. The review highlights the paper's contributions, including the introduction of informational frictions, a dynamic model of trade frictions, and the explicit accounting for the geography of trade. It also relates the paper to existing literature on international trade, networks, and the role of trade intermediaries.

American Economic Review 2014, 104(11): 3600–3634

http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.11.3600

3600

The Network Structure of International Trade†

By Thomas Chaney *

Motivated by empirical evidence I uncover on the dynamics of

French firms’ exports, I offer a novel theory of trade frictions. Firms

export only into markets where they have a contact. They search

directly for new trading partners, but also use their existing network

of contacts to search remotely for new partners. I characterize the

dynamic formation of an international network of exporters in this

model. Structurally, I estimate this model on French data and confirm

its predictions regarding the distribution of the number of foreign

markets accessed by exporters and the geographic distribution of

exports. (JEL D85, F11, F14, L24)

This paper proposes a new theory of the frictions associated with internationa

trade, and more generally the frictions that affect the ability of firms to trade w

each other. Samuelson (1954) and later Krugman (1980) recognized the key im

tance that trade frictions play not only in shaping the patterns of international

but also in determining relative factor prices between countries, and ulti

comparative development. Despite the central role they play in trade models, t

frictions remain largely unexplained, and we only have a very crude formalizat

of those frictions. Samuelson (1954), Krugman (1980) and most of the trade lit

ture assume “iceberg”-type trade costs, a simple proportional cost. Melitz (200

Helpman, Melitz, and Rubinstein (2008); and Chaney (2008) recognize the imp

tance of the extensive margin of trade in determining firm level and aggregate

and introduce a fixed cost in addition to the usual iceberg cost. Arkolakis (2010

further endogenizes this fixed cost and allows firms to choose from a menu of fi

costs. Yet this simple combination of a fixed and a variable cost is too crude to

ture many facts about firm-level exports. Whereas Bernard et al. (2003) or Mel

(2003) assume that differences in the ability of firms to enter foreign markets a

entirely driven by heterogeneous productivities, Armenter and Koren (forth

ing) point out that productivity differences can only account for a fraction of th

* Toulouse School of Economics, 21 Allee de Brienne, 31000 Toulouse, France (e-mail: thomas.chaney@gm

com). I am grateful to Enghin Atalay, Sylvain Chassang, Xavier Gabaix, Sam Kortum, Pierre-Louis Lions, Bob

Lucas, Marc Melitz, Roger Myerson, David Sraer, Nancy Stokey, and seminar participants at Chicago (Math a

Econ), Columbia, Harvard, MIT, the NBER Summer Institute, NYU, Princeton, Sciences Po (Paris), Toronto, the

Toulouse School of Economics, UBC Vancouver, UQAM, UW Milwaukee, Wharton, and Yale for helpful discus-

sions, and NSF grant SES-1061622 for financial support. I am indebted to Ferdinando Monte and Enghin Atal

for their superb research assistance. I declare that I have received in the last three years more than US$10,0

the National Science Foundation, in the form of a research grant (SES-1061622) for the particular research t

addressed in this paper. Beyond this grant, I have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to th

in this paper. First draft: July 2010.

† Go to http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.11.3600 to visit the article page for additional materials and aut

disclosure statement(s).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.11.3600

3600

The Network Structure of International Trade†

By Thomas Chaney *

Motivated by empirical evidence I uncover on the dynamics of

French firms’ exports, I offer a novel theory of trade frictions. Firms

export only into markets where they have a contact. They search

directly for new trading partners, but also use their existing network

of contacts to search remotely for new partners. I characterize the

dynamic formation of an international network of exporters in this

model. Structurally, I estimate this model on French data and confirm

its predictions regarding the distribution of the number of foreign

markets accessed by exporters and the geographic distribution of

exports. (JEL D85, F11, F14, L24)

This paper proposes a new theory of the frictions associated with internationa

trade, and more generally the frictions that affect the ability of firms to trade w

each other. Samuelson (1954) and later Krugman (1980) recognized the key im

tance that trade frictions play not only in shaping the patterns of international

but also in determining relative factor prices between countries, and ulti

comparative development. Despite the central role they play in trade models, t

frictions remain largely unexplained, and we only have a very crude formalizat

of those frictions. Samuelson (1954), Krugman (1980) and most of the trade lit

ture assume “iceberg”-type trade costs, a simple proportional cost. Melitz (200

Helpman, Melitz, and Rubinstein (2008); and Chaney (2008) recognize the imp

tance of the extensive margin of trade in determining firm level and aggregate

and introduce a fixed cost in addition to the usual iceberg cost. Arkolakis (2010

further endogenizes this fixed cost and allows firms to choose from a menu of fi

costs. Yet this simple combination of a fixed and a variable cost is too crude to

ture many facts about firm-level exports. Whereas Bernard et al. (2003) or Mel

(2003) assume that differences in the ability of firms to enter foreign markets a

entirely driven by heterogeneous productivities, Armenter and Koren (forth

ing) point out that productivity differences can only account for a fraction of th

* Toulouse School of Economics, 21 Allee de Brienne, 31000 Toulouse, France (e-mail: thomas.chaney@gm

com). I am grateful to Enghin Atalay, Sylvain Chassang, Xavier Gabaix, Sam Kortum, Pierre-Louis Lions, Bob

Lucas, Marc Melitz, Roger Myerson, David Sraer, Nancy Stokey, and seminar participants at Chicago (Math a

Econ), Columbia, Harvard, MIT, the NBER Summer Institute, NYU, Princeton, Sciences Po (Paris), Toronto, the

Toulouse School of Economics, UBC Vancouver, UQAM, UW Milwaukee, Wharton, and Yale for helpful discus-

sions, and NSF grant SES-1061622 for financial support. I am indebted to Ferdinando Monte and Enghin Atal

for their superb research assistance. I declare that I have received in the last three years more than US$10,0

the National Science Foundation, in the form of a research grant (SES-1061622) for the particular research t

addressed in this paper. Beyond this grant, I have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to th

in this paper. First draft: July 2010.

† Go to http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.11.3600 to visit the article page for additional materials and aut

disclosure statement(s).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3601CHANEY: THE NETWORK STRUCTURE OF TRADEVOL. 104 NO. 11

exposure to international markets. Similarly, Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (201

show that a large amount of idiosyncratic noise has to be added to the simple c

nation of fixed and variable costs of the Melitz model in order to empirically ma

firm level exports from France.

The main contribution of this paper is to develop a theory of trade frictions ba

on the notion of informational frictions. This theory is motivated by new stylize

facts I uncover on the dynamics of firm-level exports in France. The second con

bution of this paper is to build a dynamic model of trade frictions. While there a

strong patterns in the dynamics of firm-level trade, most existing trade models

static in essence.1 By adding structure to the export dynamics, I generate predictio

linking the cross section and the time series of international trade. The third co

bution of this paper is explicitly to account for the geography of trade. Geograp

measured as the physical distance between countries, plays a crucial role in ex

ing the empirical patterns of international trade, yet it is absent from most trad

models.2 I show how to introduce geographic space into a theoretical model of fi

level trade, and provide precise empirical evidence in support of the model. I fo

primarily on the physical distance between locations. The reason is both that th

a measure that is easy to calculate and that this is the measure that is empiric

most relevant to explain trade flows. Putting together those three contributions

notion that information is a key friction to trade, its corollary that the diffusion

information will follow an intrinsically dynamic process, and the fact that geogr

phy matters for trade in a specific way—this paper offers a very different persp

on international trade compared to traditional models.

Before describing the related literature, I will spell out quickly the main intuit

from the model, as well as the main predictions that I bring to the data.

Potential exporters meet foreign trading partners in two distinct ways.

firm searches directly for foreign partners, which I model as a geographically b

random search. Second, once a firm has acquired a network of foreign contacts

various foreign locations, it can search remotely for new trading partners from

locations. Those two assumptions are motivated by novel empirical evidence o

dynamics of firms exports I uncover using data on French firms from 1986 to 1

The more countries a firm exports to, the more likely it is to enter new market

sequently. Moreover, where a firm exports to affects which specific markets it w

enter in the future: if a French firm exports to country a in year t, it is then mor

likely to enter in year t + 1 a country b geographically close to a, even if b is no

close to France. The possibility to use existing contacts to find new ones gives

advantage to firms with many contacts. This generates a fat-tailed distribution

the number of foreign contacts across firms. The empirical distribution of the n

ber of foreign contacts is well described by the theory.

A more elaborate contribution of this paper accounts for geographic sp

Remote search allows say a French exporter that has a acquired a contact in Ja

1Dixit (1989); Krugman (1987); and Young (1991) are among a few early and notable exceptions, as are a

recent papers mentioned below in this introduction.

2There are a few important exceptions in the economic geography literature (for instance, Fujita, Krugman

Mori 1999). However, this literature is primarily theoretical, and rarely goes beyond testing a few stylized em

facts, if any. Desmet and Rossi-Hansberg (2010) identify some of the challenges of introducing space in an e

rium model, and show some empirical evidence. See Allen and Arkolakis (forthcoming) for a recent contribu

exposure to international markets. Similarly, Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (201

show that a large amount of idiosyncratic noise has to be added to the simple c

nation of fixed and variable costs of the Melitz model in order to empirically ma

firm level exports from France.

The main contribution of this paper is to develop a theory of trade frictions ba

on the notion of informational frictions. This theory is motivated by new stylize

facts I uncover on the dynamics of firm-level exports in France. The second con

bution of this paper is to build a dynamic model of trade frictions. While there a

strong patterns in the dynamics of firm-level trade, most existing trade models

static in essence.1 By adding structure to the export dynamics, I generate predictio

linking the cross section and the time series of international trade. The third co

bution of this paper is explicitly to account for the geography of trade. Geograp

measured as the physical distance between countries, plays a crucial role in ex

ing the empirical patterns of international trade, yet it is absent from most trad

models.2 I show how to introduce geographic space into a theoretical model of fi

level trade, and provide precise empirical evidence in support of the model. I fo

primarily on the physical distance between locations. The reason is both that th

a measure that is easy to calculate and that this is the measure that is empiric

most relevant to explain trade flows. Putting together those three contributions

notion that information is a key friction to trade, its corollary that the diffusion

information will follow an intrinsically dynamic process, and the fact that geogr

phy matters for trade in a specific way—this paper offers a very different persp

on international trade compared to traditional models.

Before describing the related literature, I will spell out quickly the main intuit

from the model, as well as the main predictions that I bring to the data.

Potential exporters meet foreign trading partners in two distinct ways.

firm searches directly for foreign partners, which I model as a geographically b

random search. Second, once a firm has acquired a network of foreign contacts

various foreign locations, it can search remotely for new trading partners from

locations. Those two assumptions are motivated by novel empirical evidence o

dynamics of firms exports I uncover using data on French firms from 1986 to 1

The more countries a firm exports to, the more likely it is to enter new market

sequently. Moreover, where a firm exports to affects which specific markets it w

enter in the future: if a French firm exports to country a in year t, it is then mor

likely to enter in year t + 1 a country b geographically close to a, even if b is no

close to France. The possibility to use existing contacts to find new ones gives

advantage to firms with many contacts. This generates a fat-tailed distribution

the number of foreign contacts across firms. The empirical distribution of the n

ber of foreign contacts is well described by the theory.

A more elaborate contribution of this paper accounts for geographic sp

Remote search allows say a French exporter that has a acquired a contact in Ja

1Dixit (1989); Krugman (1987); and Young (1991) are among a few early and notable exceptions, as are a

recent papers mentioned below in this introduction.

2There are a few important exceptions in the economic geography literature (for instance, Fujita, Krugman

Mori 1999). However, this literature is primarily theoretical, and rarely goes beyond testing a few stylized em

facts, if any. Desmet and Rossi-Hansberg (2010) identify some of the challenges of introducing space in an e

rium model, and show some empirical evidence. See Allen and Arkolakis (forthcoming) for a recent contribu

3602 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW NOVEMBER 2014

to radiate away from Japan as Japanese firms would. It does so by using its Japa

contacts as a remote hub from which it can expand out of Japan. By acquiring m

foreign contacts, firms expand into more remote countries and, as a result, exp

over longer distances. Empirically, the geographic distance of exports increase

the number of foreign contacts as the theory predicts.

This is a theory of a network. Therefore, a shock that hits anywhere will be

transmitted throughout the network, with an intensity that depends on the stru

ture of the network. The data confirms this prediction. For instance, I show that

a French firm which already exports to a, the probability that it begins exportin

to b will be higher following an increase in the trade volume between a and b,

else equal.

This paper contributes to the literature on international trade and networks.

There is a nascent literature in international trade and macroeconomics on th

that informational barriers and informational networks play in facilitating or ham

pering transactions, and in transmitting shocks. In a seminal paper, Rauch (199

conjectures that informational barriers play an important role. He offers a class

cation of traded goods between differentiated and homogeneous goods, and sh

that geographic proximity is more important for trade in differentiated goods. H

argues that this is evidence for the importance of informational barriers. While

Rauch classification has been used widely in international trade, the noti

informational networks are important in overcoming informational barriers

remained relatively underexplored. I offer a formal treatment of the network th

allows information to diffuse, and show evidence of this network using firm-leve

trade data. Rauch and Trindade (2002) show that the presence of ethnic Chine

networks facilitates bilateral trade, and particularly so for trade in differe

goods. They argue that these findings are evidence for the importance o

mational barriers, and that social networks mitigate those barriers. Rauch (200

offers a survey of the literature on networks in international trade. In the conte

intranational trade, Combes, Lafourcade, and Mayer (2005) show that social an

business networks facilitate trade between regions within France, where they u

migrations and multiplant firms to infer a measure of social and business linka

Using Spanish data, Garmendia et al. (2012) show that social and business net

have a stronger impact on the extensive margin than on the intensive margin o

a prediction that holds in my model. Burchardi and Hassan (2013) show that W

German regions which have closer social ties with East Germany inherited from

tumultuous history of refugees relocations after WWII experienced faster growt

and engaged in more investment into East Germany after the German reunifica

In this paper, I develop a more general model of the formation of an internation

network of firms, and show how this network matters for firm-level trade patter

over and beyond the effects analyzed in special cases studied so far.

On a somewhat related topic, Hidalgo et al. (2007) show that the product mix

goods manufactured and exported by countries can be described as a network

that countries move toward more connected sectors as they grow. Acemoglu e

(2012) describe the input-output linkages between sectors in the United States

network, and show how idiosyncratic shocks to individual sectors have a nonne

ble impact on aggregate volatility. The results I present on the transmission of

gate trade shocks on firm exports suggest that similar forces may be at play in

to radiate away from Japan as Japanese firms would. It does so by using its Japa

contacts as a remote hub from which it can expand out of Japan. By acquiring m

foreign contacts, firms expand into more remote countries and, as a result, exp

over longer distances. Empirically, the geographic distance of exports increase

the number of foreign contacts as the theory predicts.

This is a theory of a network. Therefore, a shock that hits anywhere will be

transmitted throughout the network, with an intensity that depends on the stru

ture of the network. The data confirms this prediction. For instance, I show that

a French firm which already exports to a, the probability that it begins exportin

to b will be higher following an increase in the trade volume between a and b,

else equal.

This paper contributes to the literature on international trade and networks.

There is a nascent literature in international trade and macroeconomics on th

that informational barriers and informational networks play in facilitating or ham

pering transactions, and in transmitting shocks. In a seminal paper, Rauch (199

conjectures that informational barriers play an important role. He offers a class

cation of traded goods between differentiated and homogeneous goods, and sh

that geographic proximity is more important for trade in differentiated goods. H

argues that this is evidence for the importance of informational barriers. While

Rauch classification has been used widely in international trade, the noti

informational networks are important in overcoming informational barriers

remained relatively underexplored. I offer a formal treatment of the network th

allows information to diffuse, and show evidence of this network using firm-leve

trade data. Rauch and Trindade (2002) show that the presence of ethnic Chine

networks facilitates bilateral trade, and particularly so for trade in differe

goods. They argue that these findings are evidence for the importance o

mational barriers, and that social networks mitigate those barriers. Rauch (200

offers a survey of the literature on networks in international trade. In the conte

intranational trade, Combes, Lafourcade, and Mayer (2005) show that social an

business networks facilitate trade between regions within France, where they u

migrations and multiplant firms to infer a measure of social and business linka

Using Spanish data, Garmendia et al. (2012) show that social and business net

have a stronger impact on the extensive margin than on the intensive margin o

a prediction that holds in my model. Burchardi and Hassan (2013) show that W

German regions which have closer social ties with East Germany inherited from

tumultuous history of refugees relocations after WWII experienced faster growt

and engaged in more investment into East Germany after the German reunifica

In this paper, I develop a more general model of the formation of an internation

network of firms, and show how this network matters for firm-level trade patter

over and beyond the effects analyzed in special cases studied so far.

On a somewhat related topic, Hidalgo et al. (2007) show that the product mix

goods manufactured and exported by countries can be described as a network

that countries move toward more connected sectors as they grow. Acemoglu e

(2012) describe the input-output linkages between sectors in the United States

network, and show how idiosyncratic shocks to individual sectors have a nonne

ble impact on aggregate volatility. The results I present on the transmission of

gate trade shocks on firm exports suggest that similar forces may be at play in

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3603CHANEY: THE NETWORK STRUCTURE OF TRADEVOL. 104 NO. 11

This paper is also related to a recent literature which emphasizes the role of

intermediaries in overcoming informational barriers. Casella and Rauch (2

offer a formal model of trade with informational barriers. They assume that the

are only two types of agents: some are perfectly informed about the quality of

eign goods, while the others are uniformed. The informed agents may chose to

as intermediaries for international trade. I offer a more nuanced model where fi

gradually learn about foreign markets, so that there is close to a continuum of

with a differential access to information about foreign markets. Antràs and Cos

(2011) develop a theoretical model of trade that relaxes the assumption of a ce

ized Walrasian market, and derive predictions for the welfare gains from trade

setting where trade is intermediated. Ahn, Khandelwal, and Wei (2011) demon

empirically the importance of trade intermediaries in facilitating trade, especia

for smaller exporters and for penetrating less accessible markets. I do not form

introduce trade intermediaries, but I stress the importance of informational bar

ers, and show how a network can partially overcome these barriers. The netwo

I describe can be thought of as a formal treatment of how intermediaries conne

importers and exporters.

This paper is complementary to models of international trade with heterogen

firms such as Bernard et al. (2003), Melitz (2003) and its extension in C

(2008). Those models assume that differences in the ability of individual firms

enter foreign markets are driven entirely by some exogenous productivity diffe

ences, and by the configuration of exogenous parameters which govern the ac

sibility of different foreign markets. These models replicate successfully a serie

stylized facts regarding the size distribution of individual firms in different mark

and the efficiency of firms entering different sets of countries, as shown by Eat

Kortum, and Kramarz (2011). While successful at explaining the intensive marg

of firm-level trade, these models are unable to match simultaneously the differ

stylized facts I uncover regarding the distribution of the number and the geogr

location of foreign markets entered by different firms. By contrast, the m

develop offers a parsimonious explanation for the extensive margin of trade at

firm level, but is mostly silent about the intensive margin of trade. In that sens

model is complementary to the existing models of trade with heterogeneous fir

This paper is also complementary to a recent literature on the dynamics of ex

or more generally expansion at the firm level. Albornoz et al. (2012) and Defev

Heid, and Larch (2010) both present simple models of learning about a firm’s p

tial in a foreign market. They show evidence of the sequential entry into foreign

markets of Argentine and Chinese exporters, respectively, meaning that w

firm already exports influences where it enters next. Morales, Sheu, and

(2013) use a moment inequality estimation procedure to estimate a similar mo

sequential export choice, and document that exports tend to be history depend

They stress the importance of what they call extended gravity, which is

that if a firm exports to a particular country, it is subsequently more likely to ex

to other similar countries. This corresponds to the notion of remote search in m

model. In the case study of a single firm, Jia (2008) and Holmes (2011) study th

geographic expansion of Wal-mart in the United States. Both stress the importa

of local complementarities. New Wal-mart outlets tend to benefit from the prox

ity of its existing retail centers. Local complementarities are similar to the notio

This paper is also related to a recent literature which emphasizes the role of

intermediaries in overcoming informational barriers. Casella and Rauch (2

offer a formal model of trade with informational barriers. They assume that the

are only two types of agents: some are perfectly informed about the quality of

eign goods, while the others are uniformed. The informed agents may chose to

as intermediaries for international trade. I offer a more nuanced model where fi

gradually learn about foreign markets, so that there is close to a continuum of

with a differential access to information about foreign markets. Antràs and Cos

(2011) develop a theoretical model of trade that relaxes the assumption of a ce

ized Walrasian market, and derive predictions for the welfare gains from trade

setting where trade is intermediated. Ahn, Khandelwal, and Wei (2011) demon

empirically the importance of trade intermediaries in facilitating trade, especia

for smaller exporters and for penetrating less accessible markets. I do not form

introduce trade intermediaries, but I stress the importance of informational bar

ers, and show how a network can partially overcome these barriers. The netwo

I describe can be thought of as a formal treatment of how intermediaries conne

importers and exporters.

This paper is complementary to models of international trade with heterogen

firms such as Bernard et al. (2003), Melitz (2003) and its extension in C

(2008). Those models assume that differences in the ability of individual firms

enter foreign markets are driven entirely by some exogenous productivity diffe

ences, and by the configuration of exogenous parameters which govern the ac

sibility of different foreign markets. These models replicate successfully a serie

stylized facts regarding the size distribution of individual firms in different mark

and the efficiency of firms entering different sets of countries, as shown by Eat

Kortum, and Kramarz (2011). While successful at explaining the intensive marg

of firm-level trade, these models are unable to match simultaneously the differ

stylized facts I uncover regarding the distribution of the number and the geogr

location of foreign markets entered by different firms. By contrast, the m

develop offers a parsimonious explanation for the extensive margin of trade at

firm level, but is mostly silent about the intensive margin of trade. In that sens

model is complementary to the existing models of trade with heterogeneous fir

This paper is also complementary to a recent literature on the dynamics of ex

or more generally expansion at the firm level. Albornoz et al. (2012) and Defev

Heid, and Larch (2010) both present simple models of learning about a firm’s p

tial in a foreign market. They show evidence of the sequential entry into foreign

markets of Argentine and Chinese exporters, respectively, meaning that w

firm already exports influences where it enters next. Morales, Sheu, and

(2013) use a moment inequality estimation procedure to estimate a similar mo

sequential export choice, and document that exports tend to be history depend

They stress the importance of what they call extended gravity, which is

that if a firm exports to a particular country, it is subsequently more likely to ex

to other similar countries. This corresponds to the notion of remote search in m

model. In the case study of a single firm, Jia (2008) and Holmes (2011) study th

geographic expansion of Wal-mart in the United States. Both stress the importa

of local complementarities. New Wal-mart outlets tend to benefit from the prox

ity of its existing retail centers. Local complementarities are similar to the notio

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3604 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW NOVEMBER 2014

of remote search in my paper, and the expansion of this single firm is similar to

expansion of exporters in my model. My paper is complementary to those pape

the sense that I incorporate these observations formally into a theoretical mod

the dynamics of entry of firms. I show how to analyze the properties of this mo

a tractable way. And I show formally how the dynamics of firm-level exports sh

both the cross-sectional distribution of exports as well as the time series of exp

the firm level. By going further into solving a theoretical model, I extract empir

predictions which are easier to test.

Finally, this paper is indirectly related to the literature on social networks. Wh

there is no explicit notion of social ties in my model, the formal treatment of fir

linkages resembles the analysis of the social network literature. Jackson and Ro

(2007) propose a tractable way to combine the features of a random network a

a preferential network. The notions of direct and remote search in my model ar

similar to their notions of random and preferential attachment. The main theor

innovation of my model is to embed this general network into an arbitrary spac

For the purpose of this paper, I assume that this space corresponds to the phys

geographic space. It could alternatively correspond to any other space that des

some of the attributes of the agents connected through that network.3 Bramoulle

et al. (2012) consider a model with a finite number of types that are biased aga

each other. They show that over time, agents increase the diversity of their con

in the sense that they get connected with different types. They derive condition

under which an agent’s initial bias asymptotically vanishes. As the notion of a b

between types is similar to the notion of geographic distance between firms in

model, their results are comparable to the gradual geographic expansion of ex

in my model. The technique used in those papers for finitely many types is com

mentary to the approach for infinitely many types I use: while I can model a lar

number of types, I have to impose an assumption of symmetry that these auth

relax. Those more general assumptions however limit them to results with only

types, or to only monotonicity and asymptotic results with more than two types

I also offer an empirical application of a network model to a dataset much large

than has typically been used in the social network literature.

I present reduced-form evidence on the dynamics of firms exports in Section

build a theory motivated by this evidence in Section II, and structurally estimat

theory in Section III.

I. Reduced-Form Evidence on Trade Dynamics

In this section, I present reduced-form evidence that individual firms fo

history-dependent process when expanding into foreign markets. In partic

show that a firm which exports to more countries is more likely to enter new m

kets subsequently. More interestingly, where a firm currently exports affects w

new markets it enters subsequently: if a firm exports to country c′ at time t, it is

subsequently more likely to enter any country c that is closely connected to co

3See McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook (2001) for an overview of various situations where agents tend to

nect to each other according to some attributes outside of the network, which is generally described as hom

of remote search in my paper, and the expansion of this single firm is similar to

expansion of exporters in my model. My paper is complementary to those pape

the sense that I incorporate these observations formally into a theoretical mod

the dynamics of entry of firms. I show how to analyze the properties of this mo

a tractable way. And I show formally how the dynamics of firm-level exports sh

both the cross-sectional distribution of exports as well as the time series of exp

the firm level. By going further into solving a theoretical model, I extract empir

predictions which are easier to test.

Finally, this paper is indirectly related to the literature on social networks. Wh

there is no explicit notion of social ties in my model, the formal treatment of fir

linkages resembles the analysis of the social network literature. Jackson and Ro

(2007) propose a tractable way to combine the features of a random network a

a preferential network. The notions of direct and remote search in my model ar

similar to their notions of random and preferential attachment. The main theor

innovation of my model is to embed this general network into an arbitrary spac

For the purpose of this paper, I assume that this space corresponds to the phys

geographic space. It could alternatively correspond to any other space that des

some of the attributes of the agents connected through that network.3 Bramoulle

et al. (2012) consider a model with a finite number of types that are biased aga

each other. They show that over time, agents increase the diversity of their con

in the sense that they get connected with different types. They derive condition

under which an agent’s initial bias asymptotically vanishes. As the notion of a b

between types is similar to the notion of geographic distance between firms in

model, their results are comparable to the gradual geographic expansion of ex

in my model. The technique used in those papers for finitely many types is com

mentary to the approach for infinitely many types I use: while I can model a lar

number of types, I have to impose an assumption of symmetry that these auth

relax. Those more general assumptions however limit them to results with only

types, or to only monotonicity and asymptotic results with more than two types

I also offer an empirical application of a network model to a dataset much large

than has typically been used in the social network literature.

I present reduced-form evidence on the dynamics of firms exports in Section

build a theory motivated by this evidence in Section II, and structurally estimat

theory in Section III.

I. Reduced-Form Evidence on Trade Dynamics

In this section, I present reduced-form evidence that individual firms fo

history-dependent process when expanding into foreign markets. In partic

show that a firm which exports to more countries is more likely to enter new m

kets subsequently. More interestingly, where a firm currently exports affects w

new markets it enters subsequently: if a firm exports to country c′ at time t, it is

subsequently more likely to enter any country c that is closely connected to co

3See McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook (2001) for an overview of various situations where agents tend to

nect to each other according to some attributes outside of the network, which is generally described as hom

3605CHANEY: THE NETWORK STRUCTURE OF TRADEVOL. 104 NO. 11

c′ , either in the sense that it is geographically close toc′ , or that it trades a lot with

c′ . This reduced-form evidence motivates the theory presented in the next sec

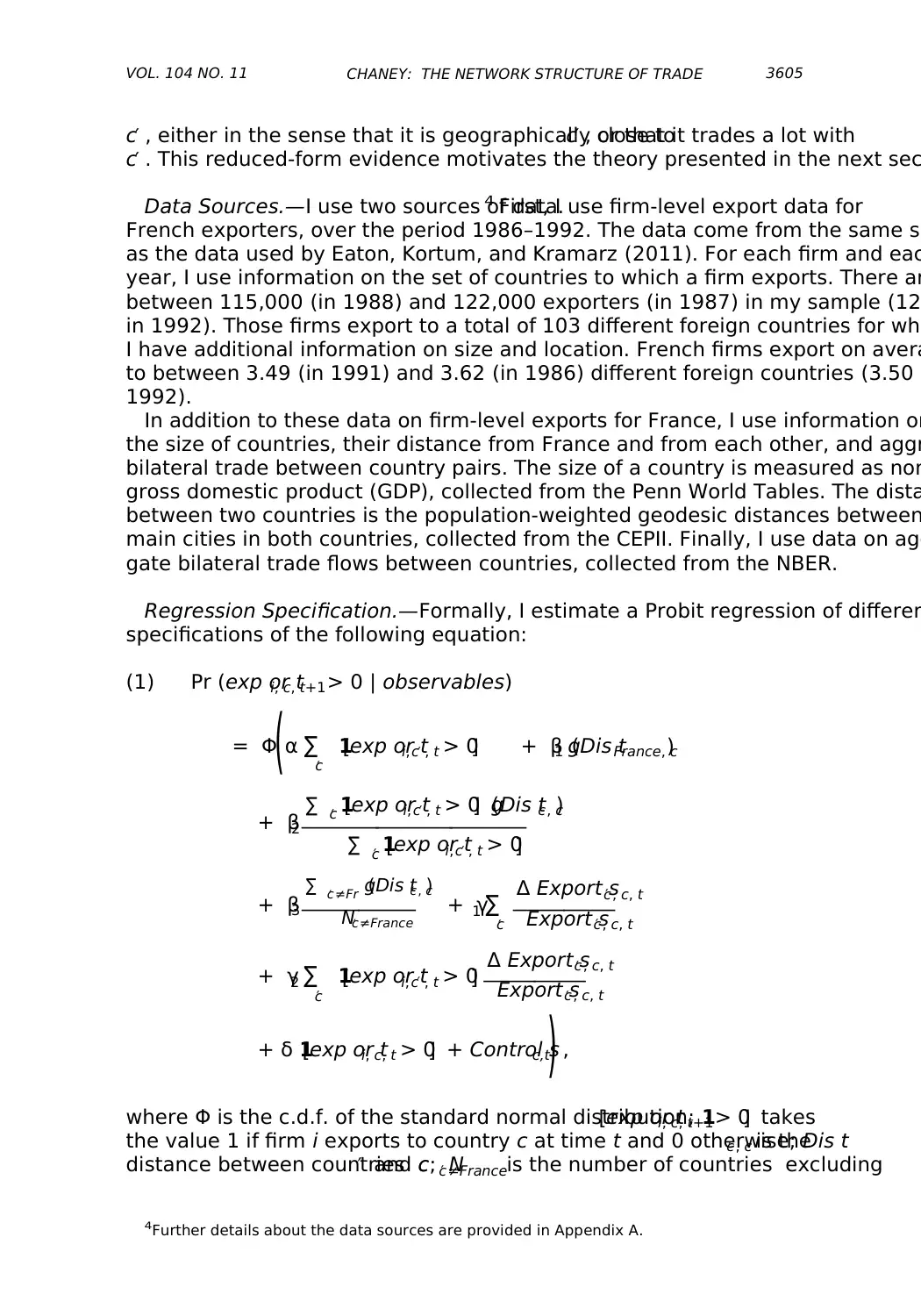

Data Sources.—I use two sources of data.4 First, I use firm-level export data for

French exporters, over the period 1986–1992. The data come from the same so

as the data used by Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (2011). For each firm and eac

year, I use information on the set of countries to which a firm exports. There ar

between 115,000 (in 1988) and 122,000 exporters (in 1987) in my sample (12

in 1992). Those firms export to a total of 103 different foreign countries for whi

I have additional information on size and location. French firms export on avera

to between 3.49 (in 1991) and 3.62 (in 1986) different foreign countries (3.50 i

1992).

In addition to these data on firm-level exports for France, I use information on

the size of countries, their distance from France and from each other, and aggr

bilateral trade between country pairs. The size of a country is measured as nom

gross domestic product (GDP), collected from the Penn World Tables. The dista

between two countries is the population-weighted geodesic distances between

main cities in both countries, collected from the CEPII. Finally, I use data on agg

gate bilateral trade flows between countries, collected from the NBER.

Regression Specification.—Formally, I estimate a Probit regression of differen

specifications of the following equation:

(1) Pr (exp or ti, c, t+1> 0 | observables)

= Φ

( α ∑c′

1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] + β1 g( Dis tFrance, c)

+ β2

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] g(Dis tc′ , c)

___

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0]

+ β3

∑ c′ ≠Fr g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

Nc′ ≠France

+ γ1 ∑c′

Δ Export sc′ , c, t__

Export sc′ , c, t

+ γ2 ∑c′

1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] Δ Export sc′ , c, t__

Export sc′ , c, t

+ δ 1[exp or ti, c, t > 0] + Control sc,t) ,

where Φ is the c.d.f. of the standard normal distribution; 1[exp or ti, c, t+1> 0] takes

the value 1 if firm i exports to country c at time t and 0 otherwise; Dis tc′ , c is the

distance between countries c′ and c; Nc′ ≠Franceis the number of countries excluding

4Further details about the data sources are provided in Appendix A.

c′ , either in the sense that it is geographically close toc′ , or that it trades a lot with

c′ . This reduced-form evidence motivates the theory presented in the next sec

Data Sources.—I use two sources of data.4 First, I use firm-level export data for

French exporters, over the period 1986–1992. The data come from the same so

as the data used by Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (2011). For each firm and eac

year, I use information on the set of countries to which a firm exports. There ar

between 115,000 (in 1988) and 122,000 exporters (in 1987) in my sample (12

in 1992). Those firms export to a total of 103 different foreign countries for whi

I have additional information on size and location. French firms export on avera

to between 3.49 (in 1991) and 3.62 (in 1986) different foreign countries (3.50 i

1992).

In addition to these data on firm-level exports for France, I use information on

the size of countries, their distance from France and from each other, and aggr

bilateral trade between country pairs. The size of a country is measured as nom

gross domestic product (GDP), collected from the Penn World Tables. The dista

between two countries is the population-weighted geodesic distances between

main cities in both countries, collected from the CEPII. Finally, I use data on agg

gate bilateral trade flows between countries, collected from the NBER.

Regression Specification.—Formally, I estimate a Probit regression of differen

specifications of the following equation:

(1) Pr (exp or ti, c, t+1> 0 | observables)

= Φ

( α ∑c′

1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] + β1 g( Dis tFrance, c)

+ β2

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] g(Dis tc′ , c)

___

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0]

+ β3

∑ c′ ≠Fr g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

Nc′ ≠France

+ γ1 ∑c′

Δ Export sc′ , c, t__

Export sc′ , c, t

+ γ2 ∑c′

1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] Δ Export sc′ , c, t__

Export sc′ , c, t

+ δ 1[exp or ti, c, t > 0] + Control sc,t) ,

where Φ is the c.d.f. of the standard normal distribution; 1[exp or ti, c, t+1> 0] takes

the value 1 if firm i exports to country c at time t and 0 otherwise; Dis tc′ , c is the

distance between countries c′ and c; Nc′ ≠Franceis the number of countries excluding

4Further details about the data sources are provided in Appendix A.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

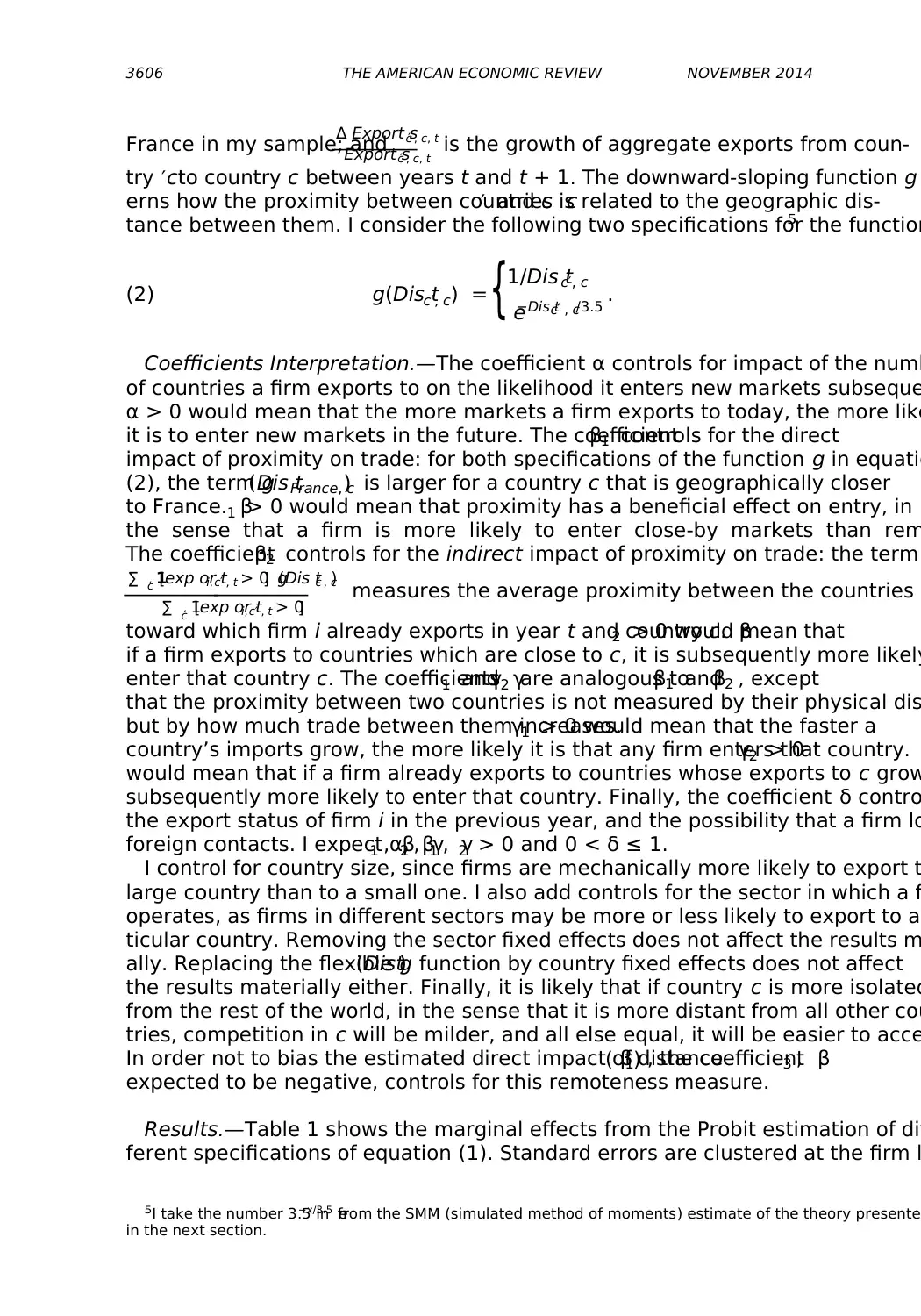

3606 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW NOVEMBER 2014

France in my sample; and

Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t is the growth of aggregate exports from coun-

try c′ to country c between years t and t + 1. The downward-sloping function g

erns how the proximity between countries c′ and c is related to the geographic dis-

tance between them. I consider the following two specifications for the function5

(2) g(Dis tc′, c) = {1/Dis tc′, c .

e−Dis tc′ , c/3.5

Coefficients Interpretation.—The coefficient α controls for impact of the numb

of countries a firm exports to on the likelihood it enters new markets subseque

α > 0 would mean that the more markets a firm exports to today, the more like

it is to enter new markets in the future. The coefficientβ1 controls for the direct

impact of proximity on trade: for both specifications of the function g in equatio

(2), the term g( Dis tFrance, c) is larger for a country c that is geographically closer

to France. β1 > 0 would mean that proximity has a beneficial effect on entry, in

the sense that a firm is more likely to enter close-by markets than rem

The coefficientβ2 controls for the indirect impact of proximity on trade: the term

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti, c′ , t > 0] g(Dis tc′ , c)

__

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] measures the average proximity between the countries

toward which firm i already exports in year t and country c. β2 > 0 would mean that

if a firm exports to countries which are close to c, it is subsequently more likely

enter that country c. The coefficients γ1 andγ2 are analogous toβ1 andβ2 , except

that the proximity between two countries is not measured by their physical dis

but by how much trade between them increases.γ1 > 0 would mean that the faster a

country’s imports grow, the more likely it is that any firm enters that country.γ2 > 0

would mean that if a firm already exports to countries whose exports to c grow

subsequently more likely to enter that country. Finally, the coefficient δ contro

the export status of firm i in the previous year, and the possibility that a firm lo

foreign contacts. I expect α, β1 , β2 , γ1 , γ2 > 0 and 0 < δ ≤ 1.

I control for country size, since firms are mechanically more likely to export t

large country than to a small one. I also add controls for the sector in which a fi

operates, as firms in different sectors may be more or less likely to export to an

ticular country. Removing the sector fixed effects does not affect the results m

ally. Replacing the flexible g(Dist) function by country fixed effects does not affect

the results materially either. Finally, it is likely that if country c is more isolated

from the rest of the world, in the sense that it is more distant from all other cou

tries, competition in c will be milder, and all else equal, it will be easier to acce

In order not to bias the estimated direct impact of distance( β1) , the coefficient β3 ,

expected to be negative, controls for this remoteness measure.

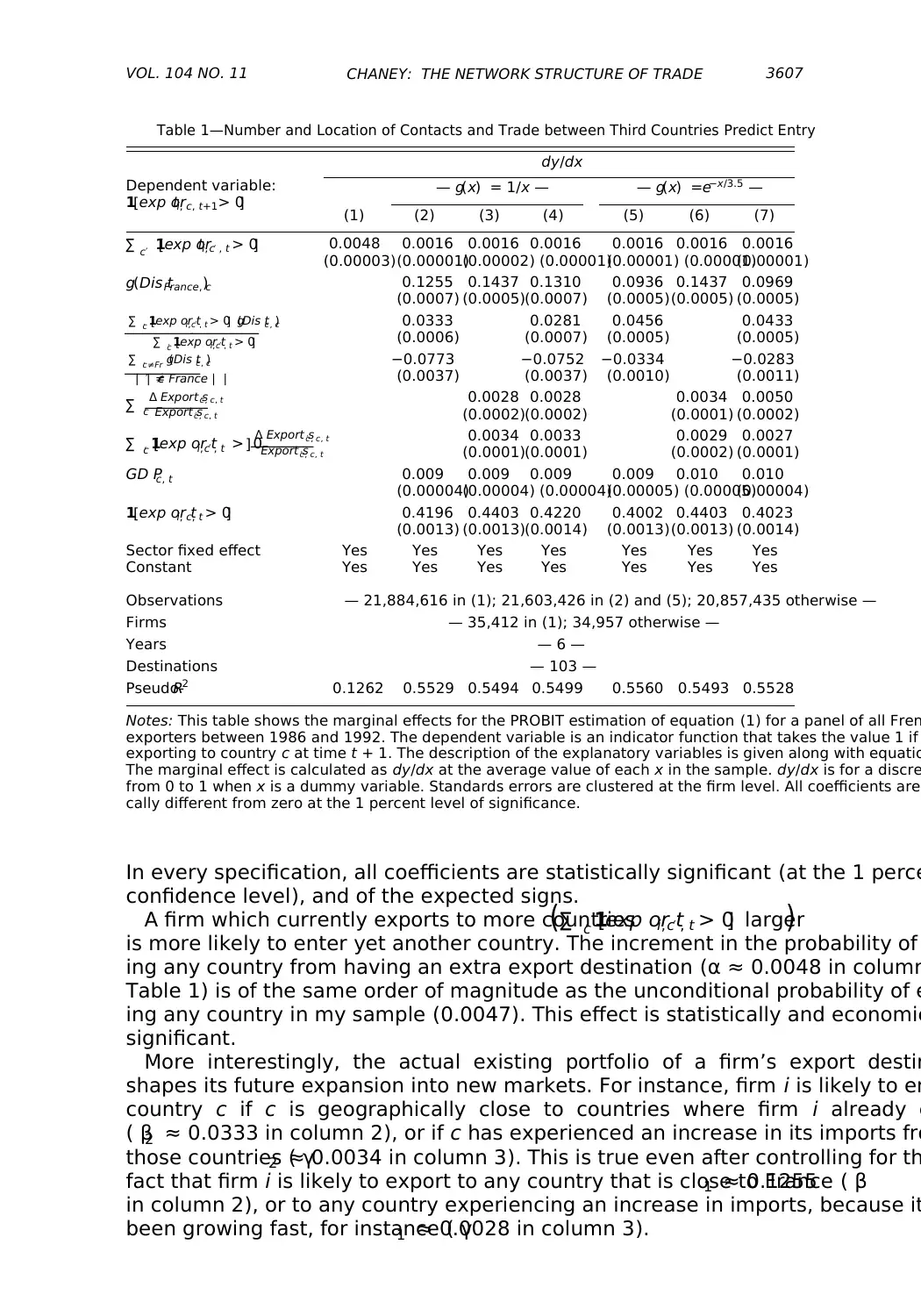

Results.—Table 1 shows the marginal effects from the Probit estimation of dif

ferent specifications of equation (1). Standard errors are clustered at the firm l

5I take the number 3.5 in e−x/3.5 from the SMM (simulated method of moments) estimate of the theory presented

in the next section.

France in my sample; and

Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t is the growth of aggregate exports from coun-

try c′ to country c between years t and t + 1. The downward-sloping function g

erns how the proximity between countries c′ and c is related to the geographic dis-

tance between them. I consider the following two specifications for the function5

(2) g(Dis tc′, c) = {1/Dis tc′, c .

e−Dis tc′ , c/3.5

Coefficients Interpretation.—The coefficient α controls for impact of the numb

of countries a firm exports to on the likelihood it enters new markets subseque

α > 0 would mean that the more markets a firm exports to today, the more like

it is to enter new markets in the future. The coefficientβ1 controls for the direct

impact of proximity on trade: for both specifications of the function g in equatio

(2), the term g( Dis tFrance, c) is larger for a country c that is geographically closer

to France. β1 > 0 would mean that proximity has a beneficial effect on entry, in

the sense that a firm is more likely to enter close-by markets than rem

The coefficientβ2 controls for the indirect impact of proximity on trade: the term

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti, c′ , t > 0] g(Dis tc′ , c)

__

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] measures the average proximity between the countries

toward which firm i already exports in year t and country c. β2 > 0 would mean that

if a firm exports to countries which are close to c, it is subsequently more likely

enter that country c. The coefficients γ1 andγ2 are analogous toβ1 andβ2 , except

that the proximity between two countries is not measured by their physical dis

but by how much trade between them increases.γ1 > 0 would mean that the faster a

country’s imports grow, the more likely it is that any firm enters that country.γ2 > 0

would mean that if a firm already exports to countries whose exports to c grow

subsequently more likely to enter that country. Finally, the coefficient δ contro

the export status of firm i in the previous year, and the possibility that a firm lo

foreign contacts. I expect α, β1 , β2 , γ1 , γ2 > 0 and 0 < δ ≤ 1.

I control for country size, since firms are mechanically more likely to export t

large country than to a small one. I also add controls for the sector in which a fi

operates, as firms in different sectors may be more or less likely to export to an

ticular country. Removing the sector fixed effects does not affect the results m

ally. Replacing the flexible g(Dist) function by country fixed effects does not affect

the results materially either. Finally, it is likely that if country c is more isolated

from the rest of the world, in the sense that it is more distant from all other cou

tries, competition in c will be milder, and all else equal, it will be easier to acce

In order not to bias the estimated direct impact of distance( β1) , the coefficient β3 ,

expected to be negative, controls for this remoteness measure.

Results.—Table 1 shows the marginal effects from the Probit estimation of dif

ferent specifications of equation (1). Standard errors are clustered at the firm l

5I take the number 3.5 in e−x/3.5 from the SMM (simulated method of moments) estimate of the theory presented

in the next section.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3607CHANEY: THE NETWORK STRUCTURE OF TRADEVOL. 104 NO. 11

In every specification, all coefficients are statistically significant (at the 1 perce

confidence level), and of the expected signs.

A firm which currently exports to more countries( ∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] larger)

is more likely to enter yet another country. The increment in the probability of

ing any country from having an extra export destination (α ≈ 0.0048 in column

Table 1) is of the same order of magnitude as the unconditional probability of e

ing any country in my sample (0.0047). This effect is statistically and economic

significant.

More interestingly, the actual existing portfolio of a firm’s export destin

shapes its future expansion into new markets. For instance, firm i is likely to en

country c if c is geographically close to countries where firm i already e

( β2 ≈ 0.0333 in column 2), or if c has experienced an increase in its imports fro

those countries ( γ2 ≈ 0.0034 in column 3). This is true even after controlling for th

fact that firm i is likely to export to any country that is close to France ( β1 ≈ 0.1255

in column 2), or to any country experiencing an increase in imports, because it

been growing fast, for instance ( γ1 ≈ 0.0028 in column 3).

Table 1—Number and Location of Contacts and Trade between Third Countries Predict Entry

Dependent variable:

1[exp orti, c, t+1> 0]

dy/dx

— g( x) = 1/x — — g( x) =e−x/3.5 —

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

∑ c′ 1[exp orti, c′ , t > 0] 0.0048 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016

(0.00003)(0.00001)(0.00002) (0.00001)(0.00001) (0.00001)(0.00001)

g( Dis tFrance, c) 0.1255 0.1437 0.1310 0.0936 0.1437 0.0969

(0.0007) (0.0005)(0.0007) (0.0005)(0.0005) (0.0005)

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0]

0.0333 0.0281 0.0456 0.0433

(0.0006) (0.0007) (0.0005) (0.0005)

∑ c′ ≠Fr g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

| | c′ ≠ France | |

−0.0773 −0.0752 −0.0334 −0.0283

(0.0037) (0.0037) (0.0010) (0.0011)

∑ c′

Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t

0.0028 0.0028 0.0034 0.0050

(0.0002)(0.0002) (0.0001) (0.0002)

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t

0.0034 0.0033 0.0029 0.0027

(0.0001)(0.0001) (0.0002) (0.0001)

GD Pc, t 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.010 0.010

(0.00004)(0.00004) (0.00004)(0.00005) (0.00005)(0.00004)

1[exp or ti, c, t > 0] 0.4196 0.4403 0.4220 0.4002 0.4403 0.4023

(0.0013) (0.0013)(0.0014) (0.0013)(0.0013) (0.0014)

Sector fixed effect Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Constant Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations — 21,884,616 in (1); 21,603,426 in (2) and (5); 20,857,435 otherwise —

Firms — 35,412 in (1); 34,957 otherwise —

Years — 6 —

Destinations — 103 —

Pseudo-R2 0.1262 0.5529 0.5494 0.5499 0.5560 0.5493 0.5528

Notes: This table shows the marginal effects for the PROBIT estimation of equation (1) for a panel of all Fren

exporters between 1986 and 1992. The dependent variable is an indicator function that takes the value 1 if

exporting to country c at time t + 1. The description of the explanatory variables is given along with equatio

The marginal effect is calculated as dy/dx at the average value of each x in the sample. dy/dx is for a discre

from 0 to 1 when x is a dummy variable. Standards errors are clustered at the firm level. All coefficients are

cally different from zero at the 1 percent level of significance.

In every specification, all coefficients are statistically significant (at the 1 perce

confidence level), and of the expected signs.

A firm which currently exports to more countries( ∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] larger)

is more likely to enter yet another country. The increment in the probability of

ing any country from having an extra export destination (α ≈ 0.0048 in column

Table 1) is of the same order of magnitude as the unconditional probability of e

ing any country in my sample (0.0047). This effect is statistically and economic

significant.

More interestingly, the actual existing portfolio of a firm’s export destin

shapes its future expansion into new markets. For instance, firm i is likely to en

country c if c is geographically close to countries where firm i already e

( β2 ≈ 0.0333 in column 2), or if c has experienced an increase in its imports fro

those countries ( γ2 ≈ 0.0034 in column 3). This is true even after controlling for th

fact that firm i is likely to export to any country that is close to France ( β1 ≈ 0.1255

in column 2), or to any country experiencing an increase in imports, because it

been growing fast, for instance ( γ1 ≈ 0.0028 in column 3).

Table 1—Number and Location of Contacts and Trade between Third Countries Predict Entry

Dependent variable:

1[exp orti, c, t+1> 0]

dy/dx

— g( x) = 1/x — — g( x) =e−x/3.5 —

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

∑ c′ 1[exp orti, c′ , t > 0] 0.0048 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016 0.0016

(0.00003)(0.00001)(0.00002) (0.00001)(0.00001) (0.00001)(0.00001)

g( Dis tFrance, c) 0.1255 0.1437 0.1310 0.0936 0.1437 0.0969

(0.0007) (0.0005)(0.0007) (0.0005)(0.0005) (0.0005)

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0]

0.0333 0.0281 0.0456 0.0433

(0.0006) (0.0007) (0.0005) (0.0005)

∑ c′ ≠Fr g( Dis tc′ , c)

__

| | c′ ≠ France | |

−0.0773 −0.0752 −0.0334 −0.0283

(0.0037) (0.0037) (0.0010) (0.0011)

∑ c′

Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t

0.0028 0.0028 0.0034 0.0050

(0.0002)(0.0002) (0.0001) (0.0002)

∑ c′ 1[exp or ti,c′ , t > 0] Δ Export sc′ , c, t_

Export sc′ , c, t

0.0034 0.0033 0.0029 0.0027

(0.0001)(0.0001) (0.0002) (0.0001)

GD Pc, t 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.010 0.010

(0.00004)(0.00004) (0.00004)(0.00005) (0.00005)(0.00004)

1[exp or ti, c, t > 0] 0.4196 0.4403 0.4220 0.4002 0.4403 0.4023

(0.0013) (0.0013)(0.0014) (0.0013)(0.0013) (0.0014)

Sector fixed effect Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Constant Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations — 21,884,616 in (1); 21,603,426 in (2) and (5); 20,857,435 otherwise —

Firms — 35,412 in (1); 34,957 otherwise —

Years — 6 —

Destinations — 103 —

Pseudo-R2 0.1262 0.5529 0.5494 0.5499 0.5560 0.5493 0.5528

Notes: This table shows the marginal effects for the PROBIT estimation of equation (1) for a panel of all Fren

exporters between 1986 and 1992. The dependent variable is an indicator function that takes the value 1 if

exporting to country c at time t + 1. The description of the explanatory variables is given along with equatio

The marginal effect is calculated as dy/dx at the average value of each x in the sample. dy/dx is for a discre

from 0 to 1 when x is a dummy variable. Standards errors are clustered at the firm level. All coefficients are

cally different from zero at the 1 percent level of significance.

3608 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW NOVEMBER 2014

Of special interest is the size of the coefficient δ. δ measures the per

of a firm’s exports to a particular country. Across the various specificatio

equation (1), δ is around 40 percent. This implies that every year, a firm

60 percent chance of exiting a country where it is currently exporting. This larg

number implies a high degree of churning in exports, an observation that reson

with the findings in Eaton et al. (2010). The estimated δ is of course the margin

effect across a heterogeneous set of exporters, so it may hide a large amount o

heterogeneity.

To conclude, I find reduced-form evidence that individual firms follow a histor

dependent process which governs their gradual entry into foreign markets. I iso

two stylized facts. First, the more countries a firm exports to today, the more li

it is to enter yet other countries in the future. Second, where a firm exports tod

affects where that firm will export in the future: all else equal, if a firm exports

countries that are close to country c, it is more likely to enter that country c in

future. Motivated by those stylized facts, I now build a theoretical model of firm

level export dynamics.

II. A Dynamic Model of Exports

In this section, I develop a model of the sequential entry of firms into foreign

kets that incorporates the stylized facts uncovered earlier in the paper. I show

a model which features a history-dependent process for exporting generates st

predictions not only for the time series of exports, but also for the cross-section

exports.

A. Setup

Space.— is a discrete set of locations. I will consider several alternatives fo

set . I start with a presentation of the theory without imposing any restriction

. I then fully solve the model for the special case = ℤ. I use this special case

to illustrate the key forces of the model. I finally turn back to a more general se

where ≠ ℤ. Using numerical simulations, I show that the results derived in th

special case = ℤ offer a good approximation of what happens in more genera

cases, and provide a useful guidance for the structural estimation of the model

Firms.—In each location x ∈ , there is a finite set of firms. Those firms sell th

output to consumers in various locations. Time is discrete, and the number of fi

in each location grows at a constant rate γ.

Search Frictions.—In the absence of any frictions, all firms would sell to all co

sumers in every location. I assume instead that firms face the following matchi

frictions.6 Every period, a firm acquires new consumers in two distinct ways. Firs

the firm searches for new consumers locally, meaning that the search originate

where the firm itself is located. This first direct search corresponds to β1 , γ1 > 0 in

6I develop in the online Appendix a simple extension of the Krugman (1980) model which endogenizes tho

assumptions.

Of special interest is the size of the coefficient δ. δ measures the per

of a firm’s exports to a particular country. Across the various specificatio

equation (1), δ is around 40 percent. This implies that every year, a firm

60 percent chance of exiting a country where it is currently exporting. This larg

number implies a high degree of churning in exports, an observation that reson

with the findings in Eaton et al. (2010). The estimated δ is of course the margin

effect across a heterogeneous set of exporters, so it may hide a large amount o

heterogeneity.

To conclude, I find reduced-form evidence that individual firms follow a histor

dependent process which governs their gradual entry into foreign markets. I iso

two stylized facts. First, the more countries a firm exports to today, the more li

it is to enter yet other countries in the future. Second, where a firm exports tod

affects where that firm will export in the future: all else equal, if a firm exports

countries that are close to country c, it is more likely to enter that country c in

future. Motivated by those stylized facts, I now build a theoretical model of firm

level export dynamics.

II. A Dynamic Model of Exports

In this section, I develop a model of the sequential entry of firms into foreign

kets that incorporates the stylized facts uncovered earlier in the paper. I show

a model which features a history-dependent process for exporting generates st

predictions not only for the time series of exports, but also for the cross-section

exports.

A. Setup

Space.— is a discrete set of locations. I will consider several alternatives fo

set . I start with a presentation of the theory without imposing any restriction

. I then fully solve the model for the special case = ℤ. I use this special case

to illustrate the key forces of the model. I finally turn back to a more general se

where ≠ ℤ. Using numerical simulations, I show that the results derived in th

special case = ℤ offer a good approximation of what happens in more genera

cases, and provide a useful guidance for the structural estimation of the model

Firms.—In each location x ∈ , there is a finite set of firms. Those firms sell th

output to consumers in various locations. Time is discrete, and the number of fi

in each location grows at a constant rate γ.

Search Frictions.—In the absence of any frictions, all firms would sell to all co

sumers in every location. I assume instead that firms face the following matchi

frictions.6 Every period, a firm acquires new consumers in two distinct ways. Firs

the firm searches for new consumers locally, meaning that the search originate

where the firm itself is located. This first direct search corresponds to β1 , γ1 > 0 in

6I develop in the online Appendix a simple extension of the Krugman (1980) model which endogenizes tho

assumptions.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3609CHANEY: THE NETWORK STRUCTURE OF TRADEVOL. 104 NO. 11

the reduced-form evidence presented in Table 1. Second, the firm uses its exis

network of consumers to search remotely, meaning that the search originates

where the existing consumers are located. This second remote search correspo

to β2 , γ2 > 0 in the reduced form evidence presented in Table 1. It captures the

of local externalities as in the case of the geographic expansion of Wal-mart in

(2008) and Holmes (2011), or in the case of Chilean exporters in Morales, Sheu

and Zahler (2013). It may either correspond to the technological constraint on

expansion of a distribution network as in Holmes (2011); to the cost of customi

a product for local tastes and requirements as in Morales, Sheu, and Zahler (20

or more generally to the notion that exporting entails some amount of traveling

communicating with business partners, so that a firm which exports to a locatio

will acquire some knowledge about y and its surrounding locations.

Note that this is a model of the extensive margin of trade only. To fix ideas, t

of the firm as an intermediate input producer, and its consumers as other down

stream firms, potentially in other locations. I model explicitly how this firm ove

time sells to more consumers in more locations, but I do not model how much i

to each of them. Superimposing a model for the intensive margin of sales is lef

future research.

Before describing the dynamic acquisition of consumers formally, it is useful

introduce a few notations. Consider firm i of age t in a location which I arbitrari

call the origin. It has a network of consumers in various locations. The total num

of consumers of firm i ismi, t , distributed in various locations. I callfi, t( x) the num-

ber of consumers firm i has in location x,

fi, t : → ℕ with∑

x∈

fi, t(x) ≡mi, t ,

so that∑ x∈ fi, t(x) is the number of consumers firm i of age t has in the subset

⊂ . The functionfi, t specifies both the number and the location of all the con-

sumers of the firm.fi, t is not a probability distribution, as it sums up tomi, t and not 1.

The distribution of consumersfi, t evolves as follows.

First, firm i searches locally for consumers from where it is located (the locat

arbitrarily called the origin). Each period, it finds∼

γμ new consumers where∼

γμ is a

positive integer-valued random variable of mean γμ. γ is the (constant) growth

of the population of firms, and μ > 0 is a parameter.7 The location x ∈ of each

of these consumers is drawn randomly according to a function g, where(0, x)

denotes the probability that a search originating from the origin (arbitrarily cal

identifies a customer in location x. I expect that the function g(0, x) depends on the

distance between the origin( 0) of the search and the destination(x) , and the size

of the destination x, but I will only impose such conditions later in Sections IIC a

IID and when I bring the model to the data in Section III.

Second, given that firm i already has consumers in various locations, it searc

for new consumers remotely from these locations. For each existing consumer

location y ∈ , the firm meets∼

γμπ new consumers where∼

γμπ is a positive integer

7Expressing the number of randomly drawn new consumers as a multiple of the population growth rate is

a normalization, which will simplify the exposition of the main results.

the reduced-form evidence presented in Table 1. Second, the firm uses its exis

network of consumers to search remotely, meaning that the search originates

where the existing consumers are located. This second remote search correspo

to β2 , γ2 > 0 in the reduced form evidence presented in Table 1. It captures the

of local externalities as in the case of the geographic expansion of Wal-mart in

(2008) and Holmes (2011), or in the case of Chilean exporters in Morales, Sheu

and Zahler (2013). It may either correspond to the technological constraint on

expansion of a distribution network as in Holmes (2011); to the cost of customi

a product for local tastes and requirements as in Morales, Sheu, and Zahler (20

or more generally to the notion that exporting entails some amount of traveling

communicating with business partners, so that a firm which exports to a locatio

will acquire some knowledge about y and its surrounding locations.

Note that this is a model of the extensive margin of trade only. To fix ideas, t

of the firm as an intermediate input producer, and its consumers as other down

stream firms, potentially in other locations. I model explicitly how this firm ove

time sells to more consumers in more locations, but I do not model how much i

to each of them. Superimposing a model for the intensive margin of sales is lef

future research.

Before describing the dynamic acquisition of consumers formally, it is useful

introduce a few notations. Consider firm i of age t in a location which I arbitrari

call the origin. It has a network of consumers in various locations. The total num

of consumers of firm i ismi, t , distributed in various locations. I callfi, t( x) the num-

ber of consumers firm i has in location x,

fi, t : → ℕ with∑

x∈

fi, t(x) ≡mi, t ,

so that∑ x∈ fi, t(x) is the number of consumers firm i of age t has in the subset

⊂ . The functionfi, t specifies both the number and the location of all the con-

sumers of the firm.fi, t is not a probability distribution, as it sums up tomi, t and not 1.

The distribution of consumersfi, t evolves as follows.

First, firm i searches locally for consumers from where it is located (the locat

arbitrarily called the origin). Each period, it finds∼

γμ new consumers where∼

γμ is a

positive integer-valued random variable of mean γμ. γ is the (constant) growth

of the population of firms, and μ > 0 is a parameter.7 The location x ∈ of each

of these consumers is drawn randomly according to a function g, where(0, x)

denotes the probability that a search originating from the origin (arbitrarily cal

identifies a customer in location x. I expect that the function g(0, x) depends on the

distance between the origin( 0) of the search and the destination(x) , and the size

of the destination x, but I will only impose such conditions later in Sections IIC a

IID and when I bring the model to the data in Section III.

Second, given that firm i already has consumers in various locations, it searc

for new consumers remotely from these locations. For each existing consumer

location y ∈ , the firm meets∼

γμπ new consumers where∼

γμπ is a positive integer

7Expressing the number of randomly drawn new consumers as a multiple of the population growth rate is

a normalization, which will simplify the exposition of the main results.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

3610 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW NOVEMBER 2014

valued random variable of mean γμπ. π ≥ 0 is a parameter. The geographic loc

tion of these consumers is independently and randomly drawn according to the

function g, where g( y, x) is the probability that a search originating from y identifie

a customer in x. Remote search works exactly as local search, except that( i ) it is

shifted from the origin to location y, and( ii ) the efficiency of this remote search

is scaled by a constant factor π, which measures the relative importance of rem

versus local search.

Without loss of generality, neither does a firm lose consumers, nor do firms d

Adding a random death process to either contacts or firms does not change an

the results below, beyond some simple rescaling of the parameters.8

Firm Level Dynamics.—The dynamic evolution of the network of consum

described above can be summarized in the following difference equation forfi, t :

(3) fi, t+1( x) −fi, t(x) =∑

k0 =1

∼

γμi

1[˜xi,k0 = x] +∑

y∈

fi, t(y) ∑

ky =1

∼

γμπi, y

1[˜xi,ky = x] ,

with the initial conditionfi, 0( x) = 0, ∀x ∈ . 1 [ · ]is the indicator function.∼

γμi and

the∼

γμπi, y are independent draws from the random variables∼

γμ and∼

γμπ, respec-

tively. The˜xs are independent realizations from the probability distribution g, wh

determine the geographic location of each new contact. I give these draws som

arbitrary index: for instance, Pr( 1[˜xi,ky = x]) = g(y, x) is the probability that a

remote search from y identifies a consumer in x. The change in the number of

sumers in location x from time t to time t + 1 can be decomposed in two terms

first term corresponds to the local search for new contacts. Anyk0 of the∼

γμi new

contacts is located in x only if˜xi,k0 = x. The second term corresponds to the remote

search for new contacts. For each existing contact firm i has in location y (ther

fi, t( y) of them), any ky of the∼

γμπi, y new contacts acquired from y is located in x only

if ˜xi,ky = x. Since the remote search can be intermediated via any location y ∈

the new consumers found in x via y have to be summed over all possible remo

location y ∈ .

The same parameters( γμ, γμπ) in equation (3) govern the dynamic evolution of

the network of contacts of any firm. This does not mean of course that any two

will follow the same path ex post, as the luck of the draw will shape each indivi

firm’s network differently. In particular, the second term in equation (3) implies

strong history dependence in firms export dynamics.

Aggregate Dynamics.—Averaging across a large number of firms within a coh

however, the randomness of each draw disappears, and I can derive a simple e

sion for the recursive evolution of population averages. Consider all the firms o

t located in the origin, and call N the number of such firms. I define ft

N( x) as the

average number of contacts in location x ∈ within this cohort, and ft( x) the limit

of this population average when N gets large,

8See Atalay et al. (2011) for a related model, without geography, that features firm deaths.

valued random variable of mean γμπ. π ≥ 0 is a parameter. The geographic loc

tion of these consumers is independently and randomly drawn according to the

function g, where g( y, x) is the probability that a search originating from y identifie

a customer in x. Remote search works exactly as local search, except that( i ) it is

shifted from the origin to location y, and( ii ) the efficiency of this remote search

is scaled by a constant factor π, which measures the relative importance of rem

versus local search.

Without loss of generality, neither does a firm lose consumers, nor do firms d

Adding a random death process to either contacts or firms does not change an

the results below, beyond some simple rescaling of the parameters.8

Firm Level Dynamics.—The dynamic evolution of the network of consum

described above can be summarized in the following difference equation forfi, t :

(3) fi, t+1( x) −fi, t(x) =∑

k0 =1

∼

γμi

1[˜xi,k0 = x] +∑

y∈

fi, t(y) ∑

ky =1

∼

γμπi, y

1[˜xi,ky = x] ,

with the initial conditionfi, 0( x) = 0, ∀x ∈ . 1 [ · ]is the indicator function.∼

γμi and

the∼

γμπi, y are independent draws from the random variables∼

γμ and∼

γμπ, respec-

tively. The˜xs are independent realizations from the probability distribution g, wh

determine the geographic location of each new contact. I give these draws som

arbitrary index: for instance, Pr( 1[˜xi,ky = x]) = g(y, x) is the probability that a

remote search from y identifies a consumer in x. The change in the number of

sumers in location x from time t to time t + 1 can be decomposed in two terms

first term corresponds to the local search for new contacts. Anyk0 of the∼

γμi new

contacts is located in x only if˜xi,k0 = x. The second term corresponds to the remote

search for new contacts. For each existing contact firm i has in location y (ther

fi, t( y) of them), any ky of the∼

γμπi, y new contacts acquired from y is located in x only

if ˜xi,ky = x. Since the remote search can be intermediated via any location y ∈

the new consumers found in x via y have to be summed over all possible remo

location y ∈ .

The same parameters( γμ, γμπ) in equation (3) govern the dynamic evolution of

the network of contacts of any firm. This does not mean of course that any two

will follow the same path ex post, as the luck of the draw will shape each indivi

firm’s network differently. In particular, the second term in equation (3) implies

strong history dependence in firms export dynamics.

Aggregate Dynamics.—Averaging across a large number of firms within a coh

however, the randomness of each draw disappears, and I can derive a simple e

sion for the recursive evolution of population averages. Consider all the firms o

t located in the origin, and call N the number of such firms. I define ft

N( x) as the

average number of contacts in location x ∈ within this cohort, and ft( x) the limit