Difference in Non-Clinical Anxiety Levels between Young and Older Adults and in Respect to Depression, Cognitive Functions and Demographic Parameters

Added on 2023-06-12

34 Pages10472 Words446 Views

CHAPTER TWO 1

Difference in Non-Clinical Anxiety Levels between Young and Older Adults and in

Respect to Depression, Cognitive Functions and Demographic Parameters

Abstracts

This study aims at examining the difference in subclinical anxiety levels between young and

older adults in relation to depression. The study sample was composed of young and old

audits both male and female that had no clinical evidence of cognitive impairment. The

participants were taken through various tests on among them those that tested on personality,

retrospective memory questionnaires. More anxiety mostly causes more depression and

worse cognition impairment as a result. The results illustrated high scores in subjective

memory complaints association with subclinical levels of depression and anxiety as well as

more negative interpersonal interactions. A deeper understanding of the variables that are

associated with subjective memory complaints may serve as a guide on how to identity

cognitive changes as early as possible and thus establishing the institutions for interventions.

Difference in Non-Clinical Anxiety Levels between Young and Older Adults and in

Respect to Depression, Cognitive Functions and Demographic Parameters

Abstracts

This study aims at examining the difference in subclinical anxiety levels between young and

older adults in relation to depression. The study sample was composed of young and old

audits both male and female that had no clinical evidence of cognitive impairment. The

participants were taken through various tests on among them those that tested on personality,

retrospective memory questionnaires. More anxiety mostly causes more depression and

worse cognition impairment as a result. The results illustrated high scores in subjective

memory complaints association with subclinical levels of depression and anxiety as well as

more negative interpersonal interactions. A deeper understanding of the variables that are

associated with subjective memory complaints may serve as a guide on how to identity

cognitive changes as early as possible and thus establishing the institutions for interventions.

CHAPTER TWO 2

Introduction

This study aim, subjective memory function, objective cognitive function and demographic

factors, that are, age, gender, years of education, handedness, eyesight which are not

extensively iterated in previous studies. The focus of the study in this chapter will be on

subclinical anxiety levels between young and older adults in relation to depression. With the

the primary objective of this PhD research being an evaluation of the existing association

between the speed of information processing and non-clinical anxiety levels, among older

and younger adults, in relation to a plethora of brain functions, this chapter is designed to

give an understanding of the all the factors before looking at the main aim and see if there is

any correlation between it and those factor that haven’t investigated deeply before.

In as much anxiety has been examined in the various demographic groups, the young against

the old, this has only been done on clinical labels and in other cases as part of depression.

This has left not so much of extensive and explorative work on the subject. On the same note,

studies on anxiety of ageing with regard to the ageing have only been exploited on a clinical

scale. All these are illustration of limited depth of research and analysis of the task. This

study focuses on subclinical anxiety level between the young and the old in relation to

depression.

Numerous research and studies on the effect of depression and anxiety on cognition have

mainly been with relation to anxiety in a wider and general perception even though there is

one study that has given targeted the adults. Still, focus has been on studies targeting

individuals suffering from mild cognitive impairment and dementia while others have

explored formal anxiety disorders. There can be more effects of non-clinical anxiety on the

elements of information processing that what has been recognized and discussed earlier.

Studies on anxiety and age for been for a long time more inclined to clinical level among the

young and older adults. Other studied have delved into an exploration of the effects of

Introduction

This study aim, subjective memory function, objective cognitive function and demographic

factors, that are, age, gender, years of education, handedness, eyesight which are not

extensively iterated in previous studies. The focus of the study in this chapter will be on

subclinical anxiety levels between young and older adults in relation to depression. With the

the primary objective of this PhD research being an evaluation of the existing association

between the speed of information processing and non-clinical anxiety levels, among older

and younger adults, in relation to a plethora of brain functions, this chapter is designed to

give an understanding of the all the factors before looking at the main aim and see if there is

any correlation between it and those factor that haven’t investigated deeply before.

In as much anxiety has been examined in the various demographic groups, the young against

the old, this has only been done on clinical labels and in other cases as part of depression.

This has left not so much of extensive and explorative work on the subject. On the same note,

studies on anxiety of ageing with regard to the ageing have only been exploited on a clinical

scale. All these are illustration of limited depth of research and analysis of the task. This

study focuses on subclinical anxiety level between the young and the old in relation to

depression.

Numerous research and studies on the effect of depression and anxiety on cognition have

mainly been with relation to anxiety in a wider and general perception even though there is

one study that has given targeted the adults. Still, focus has been on studies targeting

individuals suffering from mild cognitive impairment and dementia while others have

explored formal anxiety disorders. There can be more effects of non-clinical anxiety on the

elements of information processing that what has been recognized and discussed earlier.

Studies on anxiety and age for been for a long time more inclined to clinical level among the

young and older adults. Other studied have delved into an exploration of the effects of

CHAPTER TWO 3

depressive symptoms on cognition among the aged and perceived anxiety as part or one of

the symptoms of depression. There have not been separate studies of subclinical anxiety from

depression despite the fact that anxiety and depression have always been linked with negative

implications on the functions of cognition (Balash et al., 2013). It is against this background

that the study examines the difference in subclinical anxiety level between young and older

adults and their links to depression, demographic parameters and its effects on cognition.

This study will also allow us to understand the differences between young and old in terms of

anxiety very well, in relation to many factors before looking deeply on attention and

information processing speed.

Depression and anxiety disorders are linked with abnormal cognitive control in the form of an

attentional bias towards negative information and reduced inhibitory control (Cisler &

Koster, 2010). Even though there is a high rate for comorbidity of the anxiety disorders and

depression, above 75%, they have various underlying neural correlates. The high comorbidity

implies commonality in etiology (Peckham, McHugh & Otto, 2010). The dorsal anterior

cingulate cortex is involved in inhibitory cognitive control. It detects conflict between

competing neural representations in the perceptuo-motor system and gives a signal to the

dorsa-lateral prefrontal cortex to help in adjusting the system to a regulated level.

Depression and clinical anxiety disorders are severe diseases that affect lives of people, both

mentally and physically (Association, 1998). Some symptoms appear in milder forms even

among individuals considered as psychologically healthy (Park et al., 2010). At the clinical

levels, anxiety and depression severely affect cognitive control (Eysneck & Derakshan,

2007). There is considerable decrease in activity within anterior cortical control structures

which is responsible for most cognitive functions including attention allocation, decision

making and impulse control. There exists evidence of an inverse relationship between

depression and resting-state activity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Robinson M. D.,

depressive symptoms on cognition among the aged and perceived anxiety as part or one of

the symptoms of depression. There have not been separate studies of subclinical anxiety from

depression despite the fact that anxiety and depression have always been linked with negative

implications on the functions of cognition (Balash et al., 2013). It is against this background

that the study examines the difference in subclinical anxiety level between young and older

adults and their links to depression, demographic parameters and its effects on cognition.

This study will also allow us to understand the differences between young and old in terms of

anxiety very well, in relation to many factors before looking deeply on attention and

information processing speed.

Depression and anxiety disorders are linked with abnormal cognitive control in the form of an

attentional bias towards negative information and reduced inhibitory control (Cisler &

Koster, 2010). Even though there is a high rate for comorbidity of the anxiety disorders and

depression, above 75%, they have various underlying neural correlates. The high comorbidity

implies commonality in etiology (Peckham, McHugh & Otto, 2010). The dorsal anterior

cingulate cortex is involved in inhibitory cognitive control. It detects conflict between

competing neural representations in the perceptuo-motor system and gives a signal to the

dorsa-lateral prefrontal cortex to help in adjusting the system to a regulated level.

Depression and clinical anxiety disorders are severe diseases that affect lives of people, both

mentally and physically (Association, 1998). Some symptoms appear in milder forms even

among individuals considered as psychologically healthy (Park et al., 2010). At the clinical

levels, anxiety and depression severely affect cognitive control (Eysneck & Derakshan,

2007). There is considerable decrease in activity within anterior cortical control structures

which is responsible for most cognitive functions including attention allocation, decision

making and impulse control. There exists evidence of an inverse relationship between

depression and resting-state activity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Robinson M. D.,

CHAPTER TWO 4

2007). A highly depressed individual has a hyperactive performance in the ACC, and at

certain levels of anxiety and depression, it goes into a resting state, bringing a halt to

important cognitive functions like attention allocation (Aaron T beck, Norman Epstein, &

Robert a Steer, 1988).

Just like in clinical anxiety and depression, increased levels of subclinical anxiety and

depression symptoms occur together pointing to the likelihood of the same cause (Pizzagalli

et al., 2006). Taking this approach ends up in major theoretical challenges. This is why most

researchers treat the two as one, since they both point to the same etiologies. Studies done by

various authors (Sadock, 2009) and Anxiety and Depression Association of America

(ADAA) show that anxiety and depression could have the same or different causes or

etiologies (Association, 1998), thus, it is acceptable to test the two separately and compare

results thereafter. By testing the two variables separately and thereafter making a comparison,

the differences and the similarities in the results are compared and explorations and possible

explanations into the reasons for the differences and similarities made. Nonetheless, very

few studies have focused on determining the difference in anxiety level especially subclinical

levels between young and older adults in relation to cognitive functions especially in term of

processing information. Thus, pressing need to understand the differences between anxiety

and depression first, and see how the low levels of anxiety could lead/ or cause depression.

As there is a big overlap that exists between depression and anxiety as most studies normally

treat them as one disorder and a whole clinical illness. Coming up with a more conclusive

distinction could help in developing proper interventions aimed at increasing awareness of

Anxiety levels have been known to lower the cognitive performance of people across all the

age groups (Endler, Johnson, & Flett, 2001). Anxiety loads the brain and cognition requires

brain alertness. When it is active simultaneously, it interferes with C1 neurons and diverts

2007). A highly depressed individual has a hyperactive performance in the ACC, and at

certain levels of anxiety and depression, it goes into a resting state, bringing a halt to

important cognitive functions like attention allocation (Aaron T beck, Norman Epstein, &

Robert a Steer, 1988).

Just like in clinical anxiety and depression, increased levels of subclinical anxiety and

depression symptoms occur together pointing to the likelihood of the same cause (Pizzagalli

et al., 2006). Taking this approach ends up in major theoretical challenges. This is why most

researchers treat the two as one, since they both point to the same etiologies. Studies done by

various authors (Sadock, 2009) and Anxiety and Depression Association of America

(ADAA) show that anxiety and depression could have the same or different causes or

etiologies (Association, 1998), thus, it is acceptable to test the two separately and compare

results thereafter. By testing the two variables separately and thereafter making a comparison,

the differences and the similarities in the results are compared and explorations and possible

explanations into the reasons for the differences and similarities made. Nonetheless, very

few studies have focused on determining the difference in anxiety level especially subclinical

levels between young and older adults in relation to cognitive functions especially in term of

processing information. Thus, pressing need to understand the differences between anxiety

and depression first, and see how the low levels of anxiety could lead/ or cause depression.

As there is a big overlap that exists between depression and anxiety as most studies normally

treat them as one disorder and a whole clinical illness. Coming up with a more conclusive

distinction could help in developing proper interventions aimed at increasing awareness of

Anxiety levels have been known to lower the cognitive performance of people across all the

age groups (Endler, Johnson, & Flett, 2001). Anxiety loads the brain and cognition requires

brain alertness. When it is active simultaneously, it interferes with C1 neurons and diverts

CHAPTER TWO 5

attention making the brain less receptive and less effective in information integration (Shah

A, Jhawar, & Goel A, 2011). There is evidence of significant decline in cognitive abilities

among older adults considered to have anxiety disorders which result in cognitive impairment

(Price and Mohlman, 2007). Apart from clinical experiments (Williams JMG & MacLeod,

1998), subclinical anxiety levels have not been seriously researched on in relation to

depression and cognitive function (affects both subjective and objective cognitive and

memory processing ability) in a population-based sample across all age groups.

Goldberg et al., (2003) compared the effect of anxiety on cognitive function of older and

younger people and found that the cognitive ability of the older group is lowered in relation

to thought process, perception and general problem solving, more than that of the younger

group. However, Unterrainer et al., (2018) differ with this observation based on the evidence

from their study, that low anxiety levels and cognitive function of people are not related

regardless of age. The associations they observed in clinical groups differed with ones in

population-based samples. Higher ratings of anxiety were associated with lower planning

performance independent of age. The evidence from the two studies, Mattay et al., (2003) and

Unterrainer et al., (2018) do not adequately explain the effects of subclinical anxiety levels on

cognitive function of individuals. This study explored this difference to help in better

understanding of how different levels of anxiety impair cognition and also help improve

measures in place to evaluate individuals with cognitive problems caused by non-clinical

anxiety and depression. Young and old people have significant differences in how the anxiety

levels affect their cognitive abilities. Old people are less susceptible to different anxiety

levels than young people as will be seen in results section, which is in concurrence with

previous studies. This is mostly because old people are more settled and do not worry about

life and all its troubles. They are more interested in living in peace and integrity. Subjective

attention making the brain less receptive and less effective in information integration (Shah

A, Jhawar, & Goel A, 2011). There is evidence of significant decline in cognitive abilities

among older adults considered to have anxiety disorders which result in cognitive impairment

(Price and Mohlman, 2007). Apart from clinical experiments (Williams JMG & MacLeod,

1998), subclinical anxiety levels have not been seriously researched on in relation to

depression and cognitive function (affects both subjective and objective cognitive and

memory processing ability) in a population-based sample across all age groups.

Goldberg et al., (2003) compared the effect of anxiety on cognitive function of older and

younger people and found that the cognitive ability of the older group is lowered in relation

to thought process, perception and general problem solving, more than that of the younger

group. However, Unterrainer et al., (2018) differ with this observation based on the evidence

from their study, that low anxiety levels and cognitive function of people are not related

regardless of age. The associations they observed in clinical groups differed with ones in

population-based samples. Higher ratings of anxiety were associated with lower planning

performance independent of age. The evidence from the two studies, Mattay et al., (2003) and

Unterrainer et al., (2018) do not adequately explain the effects of subclinical anxiety levels on

cognitive function of individuals. This study explored this difference to help in better

understanding of how different levels of anxiety impair cognition and also help improve

measures in place to evaluate individuals with cognitive problems caused by non-clinical

anxiety and depression. Young and old people have significant differences in how the anxiety

levels affect their cognitive abilities. Old people are less susceptible to different anxiety

levels than young people as will be seen in results section, which is in concurrence with

previous studies. This is mostly because old people are more settled and do not worry about

life and all its troubles. They are more interested in living in peace and integrity. Subjective

CHAPTER TWO 6

and objective cognitive functions are key elements in this study since they determine how

anxiety levels influence cognitive functions of both old and young groups.

METHODS

This section briefly describes the methods used to conduct the investigation, including

participants, measuring instruments, and other details of how the research was conducted.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the guidance and approval of the Research Ethics Committee

at the University Department of Psychology, which mandates informed consent of all

participants, along with their rights to withdraw from the study at any time. The informed

consent form was signed by all participants. All data collected in this study was blinded to

participant identity and stored under password protection on the researcher’s computer. All

the data is confidential and only accessible to responsible authorities. All data collected was

used for empirical research, and not for any medical purpose.

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited, older and younger adults. The young group

comprised of students (n=52; age 18-25 years, 21 males: 31 females) recruited from the

Psychology Department at the University. The older group of participants (n=52; age 50-80

years, 31 females: 21 males) were recruited from the community. The average age of the

young individuals was 19.92 (SD=1.57) whereas that of older adults was 66.47 (SD=4.52). In

the younger group, those who participated received 6 credits; older adult participants received

transportation expense assistance only. The young adults were recruited through the

Psychology Subject Pool System. While the older adults were identified and approached via

emails and telephone; advertisement in local newspapers, posters and flyers made the local

population aware of the study. The selection used inclusion criteria that involved individuals

who were not suffering from any clinical anxiety disorder and illustrated regular medical

and objective cognitive functions are key elements in this study since they determine how

anxiety levels influence cognitive functions of both old and young groups.

METHODS

This section briefly describes the methods used to conduct the investigation, including

participants, measuring instruments, and other details of how the research was conducted.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the guidance and approval of the Research Ethics Committee

at the University Department of Psychology, which mandates informed consent of all

participants, along with their rights to withdraw from the study at any time. The informed

consent form was signed by all participants. All data collected in this study was blinded to

participant identity and stored under password protection on the researcher’s computer. All

the data is confidential and only accessible to responsible authorities. All data collected was

used for empirical research, and not for any medical purpose.

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited, older and younger adults. The young group

comprised of students (n=52; age 18-25 years, 21 males: 31 females) recruited from the

Psychology Department at the University. The older group of participants (n=52; age 50-80

years, 31 females: 21 males) were recruited from the community. The average age of the

young individuals was 19.92 (SD=1.57) whereas that of older adults was 66.47 (SD=4.52). In

the younger group, those who participated received 6 credits; older adult participants received

transportation expense assistance only. The young adults were recruited through the

Psychology Subject Pool System. While the older adults were identified and approached via

emails and telephone; advertisement in local newspapers, posters and flyers made the local

population aware of the study. The selection used inclusion criteria that involved individuals

who were not suffering from any clinical anxiety disorder and illustrated regular medical

CHAPTER TWO 7

visits indicating good health and no history of neurological and cognitive visual impairments;

the participants who exhibited severe depression and previous history of poor health were

excluded. Other exclusions included poor self-reported general health; past history of head

injury or neurological, medical, or psychological problems; reported cognitive impairment;

vision not normal or corrected to normal; and self-reported medications that impact cognitive

functioning. Two males were excluded from the younger group and one male excluded from

the older group due to severe depression scores in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The

participants were briefed about the objectives of the study and its importance to the field of

psychology. After completing the study, debriefing forms were given to them. All the

participants had normal general cognition score (26 or above) that was measured through

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). This approach detects objective cognitive

functioning and mild cognitive impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention,

concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction,

calculation, and orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a variety of

verbal and pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a diagram of a cube, and

doing delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores

indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont & Nasreddine, 2017).

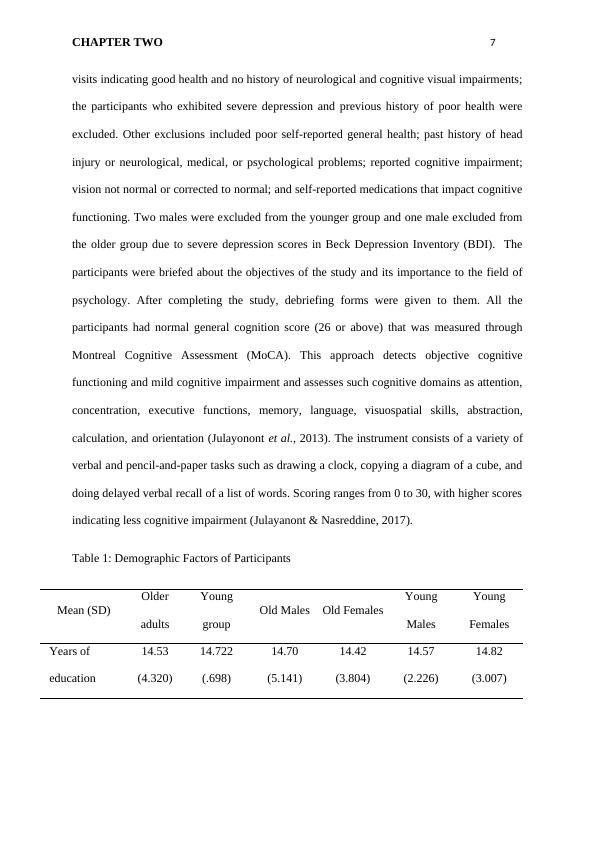

Table 1: Demographic Factors of Participants

Mean (SD)

Older

adults

Young

group

Old Males Old Females

Young

Males

Young

Females

Years of

education

14.53

(4.320)

14.722

(.698)

14.70

(5.141)

14.42

(3.804)

14.57

(2.226)

14.82

(3.007)

visits indicating good health and no history of neurological and cognitive visual impairments;

the participants who exhibited severe depression and previous history of poor health were

excluded. Other exclusions included poor self-reported general health; past history of head

injury or neurological, medical, or psychological problems; reported cognitive impairment;

vision not normal or corrected to normal; and self-reported medications that impact cognitive

functioning. Two males were excluded from the younger group and one male excluded from

the older group due to severe depression scores in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The

participants were briefed about the objectives of the study and its importance to the field of

psychology. After completing the study, debriefing forms were given to them. All the

participants had normal general cognition score (26 or above) that was measured through

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). This approach detects objective cognitive

functioning and mild cognitive impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention,

concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction,

calculation, and orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a variety of

verbal and pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a diagram of a cube, and

doing delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores

indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont & Nasreddine, 2017).

Table 1: Demographic Factors of Participants

Mean (SD)

Older

adults

Young

group

Old Males Old Females

Young

Males

Young

Females

Years of

education

14.53

(4.320)

14.722

(.698)

14.70

(5.141)

14.42

(3.804)

14.57

(2.226)

14.82

(3.007)

CHAPTER TWO 8

Data Collection

The demographic data collected included age, gender and years of education. Some of the

instruments used included consent form, information sheet and debriefing form, questionnaire

as well as demographics form, all found in Appendix A.

Instruments

Participants completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Steer & Beck A. T, 1997), the

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in full (Spielberger, 2010), including both the State and

Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Aarno

T, & Robert A, 1996), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) version 7.1 (Ziad S

Nasreddine & Phillips, 2005), and the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire

(PRMQ) (Slavin-Mulford & Hilsenroth, 2012). Each of these instruments is described below:

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to determine participant anxiety levels (Liang,

Wang and Zhu, 2016). This test is a 21-item self-assessment using a four-point Likert scale

(0: “not at all” to 3: “severely”) that focuses on somatic symptoms of anxiety as a way of

distinguishing between anxiety and depression (Julian, 2011). Scoring for the BAI is

computed by adding the scores of the 21 items, and thus ranges from 0 to 63, with higher

scores indicating greater anxiety levels. A score between from 0–21 indicates no to mild

anxiety; a score between 22 and 35 indicates moderate anxiety; and a score between 36 and

63 indicates potentially severe anxiety (Beck, 1988. Reliability of the BAI has been shown

with high internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (0.90 to 0.94).

State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI measures the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-state

anxiety in the present and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive situations as

threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two separate 20-item

Data Collection

The demographic data collected included age, gender and years of education. Some of the

instruments used included consent form, information sheet and debriefing form, questionnaire

as well as demographics form, all found in Appendix A.

Instruments

Participants completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Steer & Beck A. T, 1997), the

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in full (Spielberger, 2010), including both the State and

Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Aarno

T, & Robert A, 1996), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) version 7.1 (Ziad S

Nasreddine & Phillips, 2005), and the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire

(PRMQ) (Slavin-Mulford & Hilsenroth, 2012). Each of these instruments is described below:

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to determine participant anxiety levels (Liang,

Wang and Zhu, 2016). This test is a 21-item self-assessment using a four-point Likert scale

(0: “not at all” to 3: “severely”) that focuses on somatic symptoms of anxiety as a way of

distinguishing between anxiety and depression (Julian, 2011). Scoring for the BAI is

computed by adding the scores of the 21 items, and thus ranges from 0 to 63, with higher

scores indicating greater anxiety levels. A score between from 0–21 indicates no to mild

anxiety; a score between 22 and 35 indicates moderate anxiety; and a score between 36 and

63 indicates potentially severe anxiety (Beck, 1988. Reliability of the BAI has been shown

with high internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (0.90 to 0.94).

State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI measures the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-state

anxiety in the present and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive situations as

threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two separate 20-item

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Effects of Anxiety on Different Aspects of Information Processinglg...

|34

|10399

|104

(PDF) Anxiety disorders in older adultslg...

|34

|9370

|58

Visual Search and Information Processing Speedlg...

|46

|13333

|304

Anxiety, depression, cognitivity, and cognitive decline among elder adults and younger adultslg...

|35

|15634

|293

Anxiety, Reaction Time, and the Variability of Reaction Time in Younger and Older Adultslg...

|91

|11426

|49

Effects of Sub-clinical Anxiety Levelslg...

|39

|8262

|18