Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in dementia: systematic review of randomised controlled trials

Added on 2023-06-08

12 Pages9394 Words292 Views

The number of people with dementia is rising rapidly with

increased longevity. Although dementia’s core symptom is

cognitive deterioration, agitation is common, persistent and

distressing. Nearly half of all people with dementia have agitation

symptoms every month, including 30% of those living at home. 1

Four-fifths of those with clinically significant symptoms remain

agitated over 6 months, 2 and 20% of those initially symptom-free

develop symptoms over 2 years.2 Agitation in dementia is

associated with poor quality of life, 3 because it is unpleasant,

impedes activities and relationships, causes helplessness and anger

in family and paid caregivers,4 and predicts nursing home

admission, 5 where the agitated behaviour adversely influences

the environment.4 Several reviews, including our previous

systematic review, 6 considered all neuropsychiatric symptoms’

management together. We found direct behavioural management

therapies (BMT) with the person with dementia and specific staff

education had lasting effectiveness, but this may be limited to

affective symptoms. 7 A recent meta-analysis of family caregiver

interventions for overall neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia

found an effect size of 0.23, but did not consider which symptoms

improved.8

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia are heterogeneous,

therefore symptoms should be considered individually as success-

ful strategies may differ. The one published, well-conducted

systematic review of non-pharmacological management of

agitation in dementia included only randomised controlled trials

(RCTs) published before 2004 in English or Korean; it found just

14 papers and evidence of effectiveness only for sensory inter-

ventions.9 The review did not consider whether interventions were

effective only during the intervention or whether the effect lasted

longer; the settings in which the intervention had been shown to

be effective (e.g. in the community or in care homes); or whether

the intervention reduced levels of agitation symptoms and was

preventive or treated clinically significant agitation.

Psychotropic medication was routinely used to treat agitation

but is now discouraged since benzodiazepines and antipsychotics

increase cognitive decline, 10 and antipsychotics cause excess

mortality and are of limited efficacy. 11 Similarly, citalopram has

some efficacy but has cardiac side-effects and reduces cognition. 12

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine appear ineffective. 13,14

Preliminary evidence suggests mirtazapine may reduce agitation. 15

One RCT (not placebo-controlled) found analgesics improved

agitation in people with dementia, with an effect size comparable

to antipsychotics.16

Effective agitation management could in theory improve the

quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers, reduce

distress, decrease inappropriate medication, enable positive

relationships and activities, delay institutionalisation and be

cost-effective. We aimed therefore to review systematically the

evidence for non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in

people with dementia, both immediately and longer-term; the

costs of the successful interventions are reported in a separate

paper. 17

Method

We registered our protocol with the Prospero International

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (http://www.crd.york.

ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID = CRD42011001370). We

began electronic searches on 9 August 2011, repeating them on

12 June 2012. We searched PubMed, Web of Knowledge, British

Nursing Index, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

Programme Database, PsycINFO, NHS Evidence, System for

Information on Grey Literature, The Stationery Office Official

Publications website, the National Technical Information Service,

INAHL and the Cochrane Library. Search terms were agreed in

consultation with caregiver representatives, older adults and

436

Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation

in dementia: systematic review of randomised

controlled trials

Gill Livingston, Lynsey Kelly, Elanor Lewis-Holmes, Gianluca Baio, Stephen Morris,

Nishma Patel, Rumana Z. Omar, Cornelius Katona and Claudia Cooper

Background

Agitation in dementia is common, persistent and distressing

and can lead to care breakdown. Medication is often

ineffective and harmful.

Aims

To systematically review randomised controlled trial evidence

regarding non-pharmacological interventions.

Method

We reviewed 33 studies fitting predetermined criteria,

assessed their validity and calculated standardised effect

sizes (SES).

Results

Person-centred care, communication skills training and

adapted dementia care mapping decreased symptomatic and

severe agitation in care homes immediately (SES range

0.3–1.8) and for up to 6 months afterwards (SES range

0.2–2.2). Activities and music therapy by protocol (SES range

0.5–0.6) decreased overall agitation and sensory intervention

decreased clinically significant agitation immediately.

Aromatherapy and light therapy did not demonstrate

efficacy.

Conclusions

There are evidence-based strategies for care homes. Future

interventions should focus on consistent and long-term

implementation through staff training. Further research is

needed for people living in their own homes.

Declaration of interest

None.

The British Journal of Psychiatry (2014)

205, 436–442. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.141119

Review article

increased longevity. Although dementia’s core symptom is

cognitive deterioration, agitation is common, persistent and

distressing. Nearly half of all people with dementia have agitation

symptoms every month, including 30% of those living at home. 1

Four-fifths of those with clinically significant symptoms remain

agitated over 6 months, 2 and 20% of those initially symptom-free

develop symptoms over 2 years.2 Agitation in dementia is

associated with poor quality of life, 3 because it is unpleasant,

impedes activities and relationships, causes helplessness and anger

in family and paid caregivers,4 and predicts nursing home

admission, 5 where the agitated behaviour adversely influences

the environment.4 Several reviews, including our previous

systematic review, 6 considered all neuropsychiatric symptoms’

management together. We found direct behavioural management

therapies (BMT) with the person with dementia and specific staff

education had lasting effectiveness, but this may be limited to

affective symptoms. 7 A recent meta-analysis of family caregiver

interventions for overall neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia

found an effect size of 0.23, but did not consider which symptoms

improved.8

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia are heterogeneous,

therefore symptoms should be considered individually as success-

ful strategies may differ. The one published, well-conducted

systematic review of non-pharmacological management of

agitation in dementia included only randomised controlled trials

(RCTs) published before 2004 in English or Korean; it found just

14 papers and evidence of effectiveness only for sensory inter-

ventions.9 The review did not consider whether interventions were

effective only during the intervention or whether the effect lasted

longer; the settings in which the intervention had been shown to

be effective (e.g. in the community or in care homes); or whether

the intervention reduced levels of agitation symptoms and was

preventive or treated clinically significant agitation.

Psychotropic medication was routinely used to treat agitation

but is now discouraged since benzodiazepines and antipsychotics

increase cognitive decline, 10 and antipsychotics cause excess

mortality and are of limited efficacy. 11 Similarly, citalopram has

some efficacy but has cardiac side-effects and reduces cognition. 12

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine appear ineffective. 13,14

Preliminary evidence suggests mirtazapine may reduce agitation. 15

One RCT (not placebo-controlled) found analgesics improved

agitation in people with dementia, with an effect size comparable

to antipsychotics.16

Effective agitation management could in theory improve the

quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers, reduce

distress, decrease inappropriate medication, enable positive

relationships and activities, delay institutionalisation and be

cost-effective. We aimed therefore to review systematically the

evidence for non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in

people with dementia, both immediately and longer-term; the

costs of the successful interventions are reported in a separate

paper. 17

Method

We registered our protocol with the Prospero International

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (http://www.crd.york.

ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID = CRD42011001370). We

began electronic searches on 9 August 2011, repeating them on

12 June 2012. We searched PubMed, Web of Knowledge, British

Nursing Index, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

Programme Database, PsycINFO, NHS Evidence, System for

Information on Grey Literature, The Stationery Office Official

Publications website, the National Technical Information Service,

INAHL and the Cochrane Library. Search terms were agreed in

consultation with caregiver representatives, older adults and

436

Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation

in dementia: systematic review of randomised

controlled trials

Gill Livingston, Lynsey Kelly, Elanor Lewis-Holmes, Gianluca Baio, Stephen Morris,

Nishma Patel, Rumana Z. Omar, Cornelius Katona and Claudia Cooper

Background

Agitation in dementia is common, persistent and distressing

and can lead to care breakdown. Medication is often

ineffective and harmful.

Aims

To systematically review randomised controlled trial evidence

regarding non-pharmacological interventions.

Method

We reviewed 33 studies fitting predetermined criteria,

assessed their validity and calculated standardised effect

sizes (SES).

Results

Person-centred care, communication skills training and

adapted dementia care mapping decreased symptomatic and

severe agitation in care homes immediately (SES range

0.3–1.8) and for up to 6 months afterwards (SES range

0.2–2.2). Activities and music therapy by protocol (SES range

0.5–0.6) decreased overall agitation and sensory intervention

decreased clinically significant agitation immediately.

Aromatherapy and light therapy did not demonstrate

efficacy.

Conclusions

There are evidence-based strategies for care homes. Future

interventions should focus on consistent and long-term

implementation through staff training. Further research is

needed for people living in their own homes.

Declaration of interest

None.

The British Journal of Psychiatry (2014)

205, 436–442. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.141119

Review article

professionals. We hand-searched included papers’ reference lists

and contacted all authors about other relevant studies. We

translated eight non-English papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies in any language that met the following

criteria:

(a) the participants all had dementia, or those with dementia were

analysed separately;

(b) the study evaluated non-pharmacological interventions for

agitation, defined as inappropriate verbal, vocal or motor

activity not judged by an outside observer to be an outcome

of need, 18 encompassing physical and verbal aggression and

wandering;

(c) agitation was measured quantitatively;

(d) a comparator group was reported or agitation was compared

before and after the intervention.

We excluded studies if every individual was given psychotropic

drugs or some participants received medication as the sole

intervention. In this paper we report the highest-quality studies

– randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 45

participants – since none of the trials with a smaller sample size

provided a full and appropriate sample size calculation.

Data extraction

The first 20 search results were independently screened by G.L.

and L.K. to assess exclusion procedure reliability. No paper was

excluded incorrectly. All other papers were screened by L.K. and

E.L.H. If exclusion was unclear, L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. discussed

and reached consensus. Data extracted from the papers (by L.K.

and E.L.H.) included methodological characteristics; description

of the intervention; whether the intervention was applied to the

person with dementia, family caregivers or staff; statistical

methods; length of follow-up; diagnostic methods; and summary

outcome data (immediate and longer-term). Paper quality,

including bias, was scored independently by L.K. and E.L.H.,

discussing discrepancies with G.L. and/or G.B. They used Centre

for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) RCT evaluation criteria

(http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o = 1025); this approach gives

points for randomisation and its adequacy, participant and rater

masking, outcome measures validity and reliability, power

calculations and achievement, follow-up adequacy, accounting

for participants, and whether analyses were intention to treat

and appropriate. Possible scores range from 0 to 14 (highest

quality). Where a randomised design was used but the inter-

vention was not compared with the control group, we considered

this a within-subject design, for example the study by Raglio et

al. 19 We assigned CEBM evidence levels as follows:

(a) level 1b: high-quality RCTs (these were at least single-blind,

had follow-up rates of at least 80%, were sufficiently

powered, used intention-to-treat analysis, had valid outcome

measures and findings reported with relatively narrow

confidence intervals);

(b) level 2b: lower-quality RCTs.

Intervention categories

The authors L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. categorised the interventions

independently and then by consensus. The interventions were

activities; music therapy (protocol-driven); sensory interventions

(all involved touch, and some included additional sensory

stimulation such as light); light therapy; training paid caregivers

in person-centred care or communication skills (interventions

focused on improving communication with the person with

dementia and finding out what they wanted), with and without

supervision; dementia care mapping; aromatherapy; training

family caregivers in behavioural management therapies or

cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT); exercise; cognitive

stimulation therapy; and simulated presence therapy.

Agitation level

We separated studies according to the inclusion criteria of

participants in terms of level of symptoms of agitation: 1, no

agitation symptom necessary for inclusion; 2, some agitation

symptoms necessary for inclusion; 3, clinically significant

agitation level; 4, level unspecified. We used the usual thresholds:

a score above 39 on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory

(CMAI),20 and a score above 4 on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory

(NPI) agitation scale, 1 to denote significant agitation.

Statistical analysis

We decided a priori to meta-analyse when there were three or

more RCTs investigating sufficiently homogeneous interventions

using the same outcome measure, but no intervention met these

criteria. To facilitate comparison across interventions and

outcomes, where possible, we estimated interventions’

standardised effect sizes (SES) with 95% confidence intervals. 21

In some studies the outcome was measured and reported at several

time-points during the intervention. We used data from the last

time-point to estimate the SES, since individual patient data were

not available to incorporate repeated measures in the calculation.

We also recalculated results for studies not directly comparing

intervention and control groups but reporting only within-group

comparisons and with one-tailed significance tests, so some of our

results differ from the original analysis.

Results

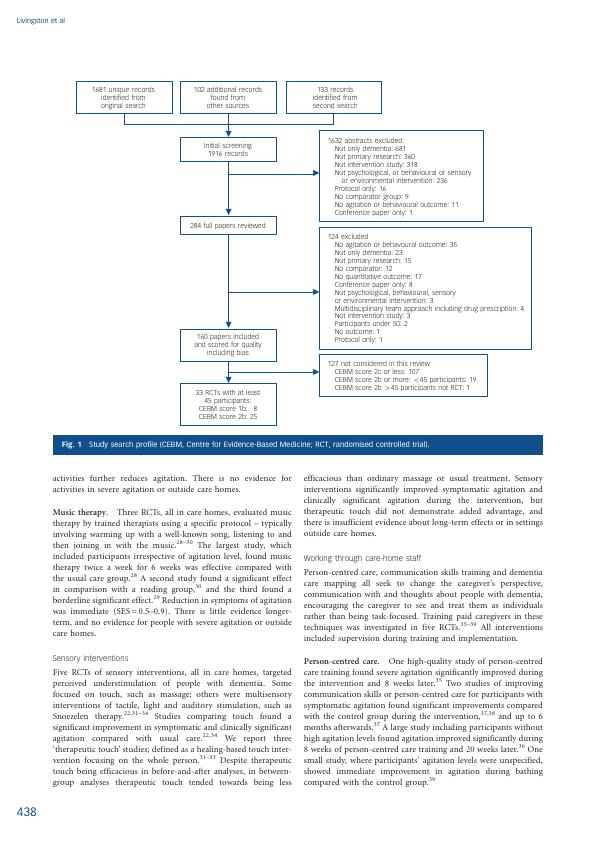

We found 1916 records, including 33 relevant RCTs with at least

45 participants (Fig. 1). Online Tables DS1 and DS2 list

methodological characteristics, SES and quality ratings; Table

DS1 contains the findings from interventions for which there

appeared to be adequate evidence, and Table DS2 contains those

for which there was not adequate evidence (either evidence that

they were not effective or where there was simply insufficient

evidence).

Efficacious interventions

Working with the person with dementia

Activities. Five of the included RCTs implemented group

activities; those with standard activities reduced mean agitation

levels, and decreased symptoms in care homes while they were

in place.22,23 One high-quality RCT found no additional effect

on agitation of individualising activities according to functional

level and interest, 24 although two lower-quality RCTs did. 25,26

All studies were in care homes except one, in which some

participants attended a day centre and others lived in a care

home. 27 None specified a significant degree of agitation for

inclusion. Only one study measured agitation after the

intervention finished, and did not show effects at 1-week and

4-week follow-up. 24

Although activities in care homes reduced levels of agitation

significantly while in place, there is no evidence regarding

longer-term effect, and it is unclear whether individualising

437

Non-pharmacological studies of agitation in dementia

and contacted all authors about other relevant studies. We

translated eight non-English papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies in any language that met the following

criteria:

(a) the participants all had dementia, or those with dementia were

analysed separately;

(b) the study evaluated non-pharmacological interventions for

agitation, defined as inappropriate verbal, vocal or motor

activity not judged by an outside observer to be an outcome

of need, 18 encompassing physical and verbal aggression and

wandering;

(c) agitation was measured quantitatively;

(d) a comparator group was reported or agitation was compared

before and after the intervention.

We excluded studies if every individual was given psychotropic

drugs or some participants received medication as the sole

intervention. In this paper we report the highest-quality studies

– randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with more than 45

participants – since none of the trials with a smaller sample size

provided a full and appropriate sample size calculation.

Data extraction

The first 20 search results were independently screened by G.L.

and L.K. to assess exclusion procedure reliability. No paper was

excluded incorrectly. All other papers were screened by L.K. and

E.L.H. If exclusion was unclear, L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. discussed

and reached consensus. Data extracted from the papers (by L.K.

and E.L.H.) included methodological characteristics; description

of the intervention; whether the intervention was applied to the

person with dementia, family caregivers or staff; statistical

methods; length of follow-up; diagnostic methods; and summary

outcome data (immediate and longer-term). Paper quality,

including bias, was scored independently by L.K. and E.L.H.,

discussing discrepancies with G.L. and/or G.B. They used Centre

for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) RCT evaluation criteria

(http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o = 1025); this approach gives

points for randomisation and its adequacy, participant and rater

masking, outcome measures validity and reliability, power

calculations and achievement, follow-up adequacy, accounting

for participants, and whether analyses were intention to treat

and appropriate. Possible scores range from 0 to 14 (highest

quality). Where a randomised design was used but the inter-

vention was not compared with the control group, we considered

this a within-subject design, for example the study by Raglio et

al. 19 We assigned CEBM evidence levels as follows:

(a) level 1b: high-quality RCTs (these were at least single-blind,

had follow-up rates of at least 80%, were sufficiently

powered, used intention-to-treat analysis, had valid outcome

measures and findings reported with relatively narrow

confidence intervals);

(b) level 2b: lower-quality RCTs.

Intervention categories

The authors L.K., E.L.H. and G.L. categorised the interventions

independently and then by consensus. The interventions were

activities; music therapy (protocol-driven); sensory interventions

(all involved touch, and some included additional sensory

stimulation such as light); light therapy; training paid caregivers

in person-centred care or communication skills (interventions

focused on improving communication with the person with

dementia and finding out what they wanted), with and without

supervision; dementia care mapping; aromatherapy; training

family caregivers in behavioural management therapies or

cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT); exercise; cognitive

stimulation therapy; and simulated presence therapy.

Agitation level

We separated studies according to the inclusion criteria of

participants in terms of level of symptoms of agitation: 1, no

agitation symptom necessary for inclusion; 2, some agitation

symptoms necessary for inclusion; 3, clinically significant

agitation level; 4, level unspecified. We used the usual thresholds:

a score above 39 on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory

(CMAI),20 and a score above 4 on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory

(NPI) agitation scale, 1 to denote significant agitation.

Statistical analysis

We decided a priori to meta-analyse when there were three or

more RCTs investigating sufficiently homogeneous interventions

using the same outcome measure, but no intervention met these

criteria. To facilitate comparison across interventions and

outcomes, where possible, we estimated interventions’

standardised effect sizes (SES) with 95% confidence intervals. 21

In some studies the outcome was measured and reported at several

time-points during the intervention. We used data from the last

time-point to estimate the SES, since individual patient data were

not available to incorporate repeated measures in the calculation.

We also recalculated results for studies not directly comparing

intervention and control groups but reporting only within-group

comparisons and with one-tailed significance tests, so some of our

results differ from the original analysis.

Results

We found 1916 records, including 33 relevant RCTs with at least

45 participants (Fig. 1). Online Tables DS1 and DS2 list

methodological characteristics, SES and quality ratings; Table

DS1 contains the findings from interventions for which there

appeared to be adequate evidence, and Table DS2 contains those

for which there was not adequate evidence (either evidence that

they were not effective or where there was simply insufficient

evidence).

Efficacious interventions

Working with the person with dementia

Activities. Five of the included RCTs implemented group

activities; those with standard activities reduced mean agitation

levels, and decreased symptoms in care homes while they were

in place.22,23 One high-quality RCT found no additional effect

on agitation of individualising activities according to functional

level and interest, 24 although two lower-quality RCTs did. 25,26

All studies were in care homes except one, in which some

participants attended a day centre and others lived in a care

home. 27 None specified a significant degree of agitation for

inclusion. Only one study measured agitation after the

intervention finished, and did not show effects at 1-week and

4-week follow-up. 24

Although activities in care homes reduced levels of agitation

significantly while in place, there is no evidence regarding

longer-term effect, and it is unclear whether individualising

437

Non-pharmacological studies of agitation in dementia

Livingston et al

activities further reduces agitation. There is no evidence for

activities in severe agitation or outside care homes.

Music therapy. Three RCTs, all in care homes, evaluated music

therapy by trained therapists using a specific protocol – typically

involving warming up with a well-known song, listening to and

then joining in with the music. 28–30 The largest study, which

included participants irrespective of agitation level, found music

therapy twice a week for 6 weeks was effective compared with

the usual care group. 28 A second study found a significant effect

in comparison with a reading group, 30 and the third found a

borderline significant effect. 29 Reduction in symptoms of agitation

was immediate (SES = 0.5–0.9). There is little evidence longer-

term, and no evidence for people with severe agitation or outside

care homes.

Sensory interventions

Five RCTs of sensory interventions, all in care homes, targeted

perceived understimulation of people with dementia. Some

focused on touch, such as massage; others were multisensory

interventions of tactile, light and auditory stimulation, such as

Snoezelen therapy. 22,31–34 Studies comparing touch found a

significant improvement in symptomatic and clinically significant

agitation compared with usual care.22,34 We report three

‘therapeutic touch’ studies; defined as a healing-based touch inter-

vention focusing on the whole person. 31–33 Despite therapeutic

touch being efficacious in before-and-after analyses, in between-

group analyses therapeutic touch tended towards being less

efficacious than ordinary massage or usual treatment. Sensory

interventions significantly improved symptomatic agitation and

clinically significant agitation during the intervention, but

therapeutic touch did not demonstrate added advantage, and

there is insufficient evidence about long-term effects or in settings

outside care homes.

Working through care-home staff

Person-centred care, communication skills training and dementia

care mapping all seek to change the caregiver’s perspective,

communication with and thoughts about people with dementia,

encouraging the caregiver to see and treat them as individuals

rather than being task-focused. Training paid caregivers in these

techniques was investigated in five RCTs. 35–39 All interventions

included supervision during training and implementation.

Person-centred care. One high-quality study of person-centred

care training found severe agitation significantly improved during

the intervention and 8 weeks later.35 Two studies of improving

communication skills or person-centred care for participants with

symptomatic agitation found significant improvements compared

with the control group during the intervention,37,38 and up to 6

months afterwards.37 A large study including participants without

high agitation levels found agitation improved significantly during

8 weeks of person-centred care training and 20 weeks later. 36 One

small study, where participants’ agitation levels were unspecified,

showed immediate improvement in agitation during bathing

compared with the control group. 39

438

102 additional records

found from

other sources

Initial screening

1916 records

284 full papers reviewed

160 papers included

and scored for quality

including bias

33 RCTs with at least

45 participants:

CEBM score 1b: 8

CEBM score 2b: 25

133 records

identified from

second search

1632 abstracts excluded:

Not only dementia: 681

Not primary research: 360

Not intervention study: 318

Not psychological, or behavioural or sensory

or environmental intervention: 236

Protocol only: 16

No comparator group: 9

No agitation or behavioural outcome: 11

Conference paper only: 1

124 excluded

No agitation or behavoural outcome: 35

Not only dementia: 23

Not primary research: 15

No comparator: 12

No quantitative outcome: 17

Conference paper only: 8

Not psychological, behavioural, sensory

or environmental intervention: 3

Multidisciplinary team approach including drug prescription: 4

Not intervention study: 3

Participants under 50: 2

No outcome: 1

Protocol only: 1

127 not considered in this review

CEBM score 2c or less: 107

CEBM score 2b or more: 545 participants: 19

CEBM score 2b 445 participants not RCT: 1

1681 unique records

identified from

original search

6

7

6

7

6

7

6

Fig. 1 Study search profile (CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; RCT, randomised controlled trial).

activities further reduces agitation. There is no evidence for

activities in severe agitation or outside care homes.

Music therapy. Three RCTs, all in care homes, evaluated music

therapy by trained therapists using a specific protocol – typically

involving warming up with a well-known song, listening to and

then joining in with the music. 28–30 The largest study, which

included participants irrespective of agitation level, found music

therapy twice a week for 6 weeks was effective compared with

the usual care group. 28 A second study found a significant effect

in comparison with a reading group, 30 and the third found a

borderline significant effect. 29 Reduction in symptoms of agitation

was immediate (SES = 0.5–0.9). There is little evidence longer-

term, and no evidence for people with severe agitation or outside

care homes.

Sensory interventions

Five RCTs of sensory interventions, all in care homes, targeted

perceived understimulation of people with dementia. Some

focused on touch, such as massage; others were multisensory

interventions of tactile, light and auditory stimulation, such as

Snoezelen therapy. 22,31–34 Studies comparing touch found a

significant improvement in symptomatic and clinically significant

agitation compared with usual care.22,34 We report three

‘therapeutic touch’ studies; defined as a healing-based touch inter-

vention focusing on the whole person. 31–33 Despite therapeutic

touch being efficacious in before-and-after analyses, in between-

group analyses therapeutic touch tended towards being less

efficacious than ordinary massage or usual treatment. Sensory

interventions significantly improved symptomatic agitation and

clinically significant agitation during the intervention, but

therapeutic touch did not demonstrate added advantage, and

there is insufficient evidence about long-term effects or in settings

outside care homes.

Working through care-home staff

Person-centred care, communication skills training and dementia

care mapping all seek to change the caregiver’s perspective,

communication with and thoughts about people with dementia,

encouraging the caregiver to see and treat them as individuals

rather than being task-focused. Training paid caregivers in these

techniques was investigated in five RCTs. 35–39 All interventions

included supervision during training and implementation.

Person-centred care. One high-quality study of person-centred

care training found severe agitation significantly improved during

the intervention and 8 weeks later.35 Two studies of improving

communication skills or person-centred care for participants with

symptomatic agitation found significant improvements compared

with the control group during the intervention,37,38 and up to 6

months afterwards.37 A large study including participants without

high agitation levels found agitation improved significantly during

8 weeks of person-centred care training and 20 weeks later. 36 One

small study, where participants’ agitation levels were unspecified,

showed immediate improvement in agitation during bathing

compared with the control group. 39

438

102 additional records

found from

other sources

Initial screening

1916 records

284 full papers reviewed

160 papers included

and scored for quality

including bias

33 RCTs with at least

45 participants:

CEBM score 1b: 8

CEBM score 2b: 25

133 records

identified from

second search

1632 abstracts excluded:

Not only dementia: 681

Not primary research: 360

Not intervention study: 318

Not psychological, or behavioural or sensory

or environmental intervention: 236

Protocol only: 16

No comparator group: 9

No agitation or behavioural outcome: 11

Conference paper only: 1

124 excluded

No agitation or behavoural outcome: 35

Not only dementia: 23

Not primary research: 15

No comparator: 12

No quantitative outcome: 17

Conference paper only: 8

Not psychological, behavioural, sensory

or environmental intervention: 3

Multidisciplinary team approach including drug prescription: 4

Not intervention study: 3

Participants under 50: 2

No outcome: 1

Protocol only: 1

127 not considered in this review

CEBM score 2c or less: 107

CEBM score 2b or more: 545 participants: 19

CEBM score 2b 445 participants not RCT: 1

1681 unique records

identified from

original search

6

7

6

7

6

7

6

Fig. 1 Study search profile (CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; RCT, randomised controlled trial).

Non-pharmacological studies of agitation in dementia

Dementia care mapping. One large, high-quality care home

study evaluated dementia care mapping. The researchers observed

and assessed each resident’s behaviour, factors improving well-

being and potential triggers; explained the results to caregivers,

and supported proposed change implementation. Severe agitation

decreased during the intervention and 4 months afterwards.35

Effect sizes. Training paid care-home staff in communication

skills, person-centred care or dementia care mapping with

supervision during implementation was significantly effective for

symptomatic and severe agitation immediately (SES = 0.3–1.8)

and for up to 6 months (SES = 0.2–2.2). There was no evidence

in other settings.

Interventions without evidence of efficacy

Working with the person with dementia

Light therapy. Light therapy hypothetically reduces agitation

through manipulating circadian rhythms, typically by 30–60 min

daily bright light exposure. We included three RCTs, all in care

homes. 40–42 Among participants with some or significant

agitation, light therapy either increased agitation or did not

improve it. The SES was 0.2 (for improvement) to 4.0 (for

worsening symptoms) compared with the control group. There

is therefore no evidence that light therapy reduces symptomatic

or severe agitation in care homes and it may worsen it.

Aromatherapy. The two RCTs of aromatherapy both took place

in care homes. 43,44 One large, high-quality blinded study found no

immediate or long-term improvement relative to the control group

for participants with severe agitation. 44 The other, non-blinded,

study found significant improvement compared with the control

group.43 When assessors are masked to the intervention,

aromatherapy has not been shown to reduce agitation in care

homes.

Training family caregivers in BMT. Two high-quality studies

found no immediate or longer-term effect (at 3 months, 6 months

or 12 months) of either four or eleven sessions training family

caregivers in BMT for severe or symptomatic agitation in people

with dementia living at home. 45,46 Two studies training family

caregivers in CBT for people with severe agitation also found no

improvement compared with controls.47,48 There is thus high-

quality evidence that teaching family caregivers BMT or CBT is

ineffective for severe agitation, but insufficient evidence to draw

conclusions regarding symptomatic agitation.

Interventions with insufficient evidence

For the following interventions there was insufficient evidence to

make a definitive recommendation.

Exercise

There is no evidence that exercise is effective. The one sufficiently

sized exercise RCT was conducted in a care home and found no

effect on agitation levels either immediately or 7 weeks later.

Training caregivers without supervision

Training in communication skills and person-centred care without

supervision was ineffective. 49,50

Other interventions

One study found that simulated presence therapy – playing a

recording mimicking a telephone conversation with a relative

when the participant was agitated – was not effective.51 One study

testing a mixed psychosocial intervention, including massage and

promoting residents’ activities of daily living skills, did not find

agitation improved significantly compared with the control

group. 52

Standardised effect sizes

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of person-centred care, communication,

dementia care mapping, music therapy and activities in reducing

agitation. Long-term effects (in months) of changing the way care-

givers interact with residents are at least as good as the short-term

effects. 35,38

Discussion

This is the first up-to-date systematic review to focus on agitation.

It uniquely analyses whether the intervention was potentially

preventive, by reducing mean levels of agitation symptoms

including those not clinically significant at baseline or managed

clinically significant agitation; whether effects were observed only

while the intervention was in place or lasted longer; and the

settings in which the intervention had been shown to be effective:

the community or in care homes.

Effective interventions

Effective interventions seem to work through care staff, partic-

ularly in the long term. There is convincing evidence that

when implementation is supervised, interventions that aim to

communicate with people with dementia, helping staff to

understand and fulfil their wishes, reduce symptomatic and severe

agitation during the intervention and for 3–6 months afterwards.

This suggests that training paid caregivers in communication,

person-centred care skills or dementia care mapping are clinically

important interventions, as shown by a 30% decrease in

agitation 43 or a standardised effect size of 0.2, which is clinically

small, 0.5 medium and 0.8 large.53

Sensory interventions significantly improved agitation of all

severities while in place. Therapeutic touch had no added

advantage. We also found replicated, good-quality evidence that

activities and music therapy by protocol reduce overall and

symptomatic agitation in care homes while in place. Although

we were surprised that individualised activities were no more

effective than prescribed activities, the low numbers in the activity

intervention groups may suggest that it was only those who were

particularly suited to the activity who participated. There is

no evidence for severe agitation. Theory-based activities

(neurodevelopmental and Montessori) were no more effective

than other pleasant activities.

Other interventions

Light therapy does not appear to be effective and may be harmful.

Non-blinded interventions with aromatherapy appeared effective,

possibly owing to rater bias, but masked raters do not find it

effective. Training family caregivers in BMT and CBT interventions

for the person with dementia was not effective. Learning complex

theories and skills and maintaining fidelity to an intervention may

be almost impossible to combine with looking after a family

member with dementia and agitation on a 24-hour basis.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is an exhaustive systematic review; two raters independently

evaluated studies to ensure reliability in study inclusion and

quality ratings. We searched all health and social sciences

439

Dementia care mapping. One large, high-quality care home

study evaluated dementia care mapping. The researchers observed

and assessed each resident’s behaviour, factors improving well-

being and potential triggers; explained the results to caregivers,

and supported proposed change implementation. Severe agitation

decreased during the intervention and 4 months afterwards.35

Effect sizes. Training paid care-home staff in communication

skills, person-centred care or dementia care mapping with

supervision during implementation was significantly effective for

symptomatic and severe agitation immediately (SES = 0.3–1.8)

and for up to 6 months (SES = 0.2–2.2). There was no evidence

in other settings.

Interventions without evidence of efficacy

Working with the person with dementia

Light therapy. Light therapy hypothetically reduces agitation

through manipulating circadian rhythms, typically by 30–60 min

daily bright light exposure. We included three RCTs, all in care

homes. 40–42 Among participants with some or significant

agitation, light therapy either increased agitation or did not

improve it. The SES was 0.2 (for improvement) to 4.0 (for

worsening symptoms) compared with the control group. There

is therefore no evidence that light therapy reduces symptomatic

or severe agitation in care homes and it may worsen it.

Aromatherapy. The two RCTs of aromatherapy both took place

in care homes. 43,44 One large, high-quality blinded study found no

immediate or long-term improvement relative to the control group

for participants with severe agitation. 44 The other, non-blinded,

study found significant improvement compared with the control

group.43 When assessors are masked to the intervention,

aromatherapy has not been shown to reduce agitation in care

homes.

Training family caregivers in BMT. Two high-quality studies

found no immediate or longer-term effect (at 3 months, 6 months

or 12 months) of either four or eleven sessions training family

caregivers in BMT for severe or symptomatic agitation in people

with dementia living at home. 45,46 Two studies training family

caregivers in CBT for people with severe agitation also found no

improvement compared with controls.47,48 There is thus high-

quality evidence that teaching family caregivers BMT or CBT is

ineffective for severe agitation, but insufficient evidence to draw

conclusions regarding symptomatic agitation.

Interventions with insufficient evidence

For the following interventions there was insufficient evidence to

make a definitive recommendation.

Exercise

There is no evidence that exercise is effective. The one sufficiently

sized exercise RCT was conducted in a care home and found no

effect on agitation levels either immediately or 7 weeks later.

Training caregivers without supervision

Training in communication skills and person-centred care without

supervision was ineffective. 49,50

Other interventions

One study found that simulated presence therapy – playing a

recording mimicking a telephone conversation with a relative

when the participant was agitated – was not effective.51 One study

testing a mixed psychosocial intervention, including massage and

promoting residents’ activities of daily living skills, did not find

agitation improved significantly compared with the control

group. 52

Standardised effect sizes

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of person-centred care, communication,

dementia care mapping, music therapy and activities in reducing

agitation. Long-term effects (in months) of changing the way care-

givers interact with residents are at least as good as the short-term

effects. 35,38

Discussion

This is the first up-to-date systematic review to focus on agitation.

It uniquely analyses whether the intervention was potentially

preventive, by reducing mean levels of agitation symptoms

including those not clinically significant at baseline or managed

clinically significant agitation; whether effects were observed only

while the intervention was in place or lasted longer; and the

settings in which the intervention had been shown to be effective:

the community or in care homes.

Effective interventions

Effective interventions seem to work through care staff, partic-

ularly in the long term. There is convincing evidence that

when implementation is supervised, interventions that aim to

communicate with people with dementia, helping staff to

understand and fulfil their wishes, reduce symptomatic and severe

agitation during the intervention and for 3–6 months afterwards.

This suggests that training paid caregivers in communication,

person-centred care skills or dementia care mapping are clinically

important interventions, as shown by a 30% decrease in

agitation 43 or a standardised effect size of 0.2, which is clinically

small, 0.5 medium and 0.8 large.53

Sensory interventions significantly improved agitation of all

severities while in place. Therapeutic touch had no added

advantage. We also found replicated, good-quality evidence that

activities and music therapy by protocol reduce overall and

symptomatic agitation in care homes while in place. Although

we were surprised that individualised activities were no more

effective than prescribed activities, the low numbers in the activity

intervention groups may suggest that it was only those who were

particularly suited to the activity who participated. There is

no evidence for severe agitation. Theory-based activities

(neurodevelopmental and Montessori) were no more effective

than other pleasant activities.

Other interventions

Light therapy does not appear to be effective and may be harmful.

Non-blinded interventions with aromatherapy appeared effective,

possibly owing to rater bias, but masked raters do not find it

effective. Training family caregivers in BMT and CBT interventions

for the person with dementia was not effective. Learning complex

theories and skills and maintaining fidelity to an intervention may

be almost impossible to combine with looking after a family

member with dementia and agitation on a 24-hour basis.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is an exhaustive systematic review; two raters independently

evaluated studies to ensure reliability in study inclusion and

quality ratings. We searched all health and social sciences

439

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Annotated Bibliography on Interventions for Dementia Patientslg...

|8

|1581

|488

Research in Nursing - Assignment PDFlg...

|12

|3330

|72

Systematic Review Checklist for Communication Strategies for People with Dementialg...

|11

|2533

|184

The impact of music therapy on wellbeing of dementia patientslg...

|12

|2931

|182

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression in Dementia Patientslg...

|7

|1866

|384

Chronic Pain: Nursing Interventions - Evidence Summarylg...

|3

|2062

|294