Nutrition Science Critique for Desklib

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|13

|7808

|322

AI Summary

This critique by Wai Lun Jeff Chan for Desklib discusses his background details, estimated energy requirements, and comparison of his average daily intake with recommendations. He also identifies two nutrients that are a priority for him to change and suggests changes he could make to reach the NRC for the identified nutrients. The two nutrients are dietary calcium and dietary fiber. Chan suggests incorporating more dairy products and fruits and nuts to increase his calcium intake and opting for skimmed or double toned milk to reduce his saturated fat intake. He also recommends consuming more high insoluble and soluble fiber food components to prevent constipation and reduce serum cholesterol levels.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

XNB251 Nutrition Science

Critique

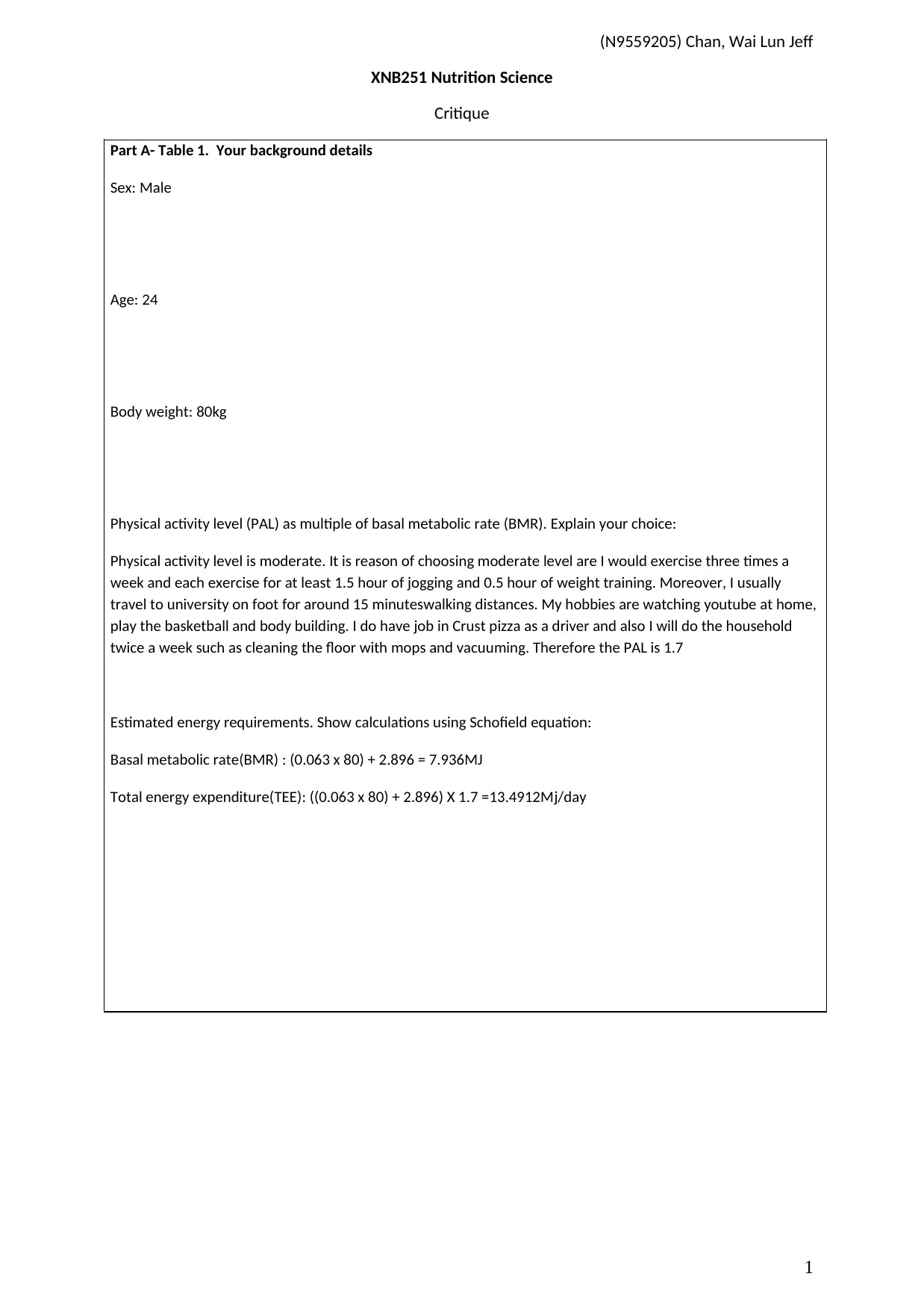

Part A- Table 1. Your background details

Sex: Male

Age: 24

Body weight: 80kg

Physical activity level (PAL) as multiple of basal metabolic rate (BMR). Explain your choice:

Physical activity level is moderate. It is reason of choosing moderate level are I would exercise three times a

week and each exercise for at least 1.5 hour of jogging and 0.5 hour of weight training. Moreover, I usually

travel to university on foot for around 15 minuteswalking distances. My hobbies are watching youtube at home,

play the basketball and body building. I do have job in Crust pizza as a driver and also I will do the household

twice a week such as cleaning the floor with mops and vacuuming. Therefore the PAL is 1.7

Estimated energy requirements. Show calculations using Schofield equation:

Basal metabolic rate(BMR) : (0.063 x 80) + 2.896 = 7.936MJ

Total energy expenditure(TEE): ((0.063 x 80) + 2.896) X 1.7 =13.4912Mj/day

1

XNB251 Nutrition Science

Critique

Part A- Table 1. Your background details

Sex: Male

Age: 24

Body weight: 80kg

Physical activity level (PAL) as multiple of basal metabolic rate (BMR). Explain your choice:

Physical activity level is moderate. It is reason of choosing moderate level are I would exercise three times a

week and each exercise for at least 1.5 hour of jogging and 0.5 hour of weight training. Moreover, I usually

travel to university on foot for around 15 minuteswalking distances. My hobbies are watching youtube at home,

play the basketball and body building. I do have job in Crust pizza as a driver and also I will do the household

twice a week such as cleaning the floor with mops and vacuuming. Therefore the PAL is 1.7

Estimated energy requirements. Show calculations using Schofield equation:

Basal metabolic rate(BMR) : (0.063 x 80) + 2.896 = 7.936MJ

Total energy expenditure(TEE): ((0.063 x 80) + 2.896) X 1.7 =13.4912Mj/day

1

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

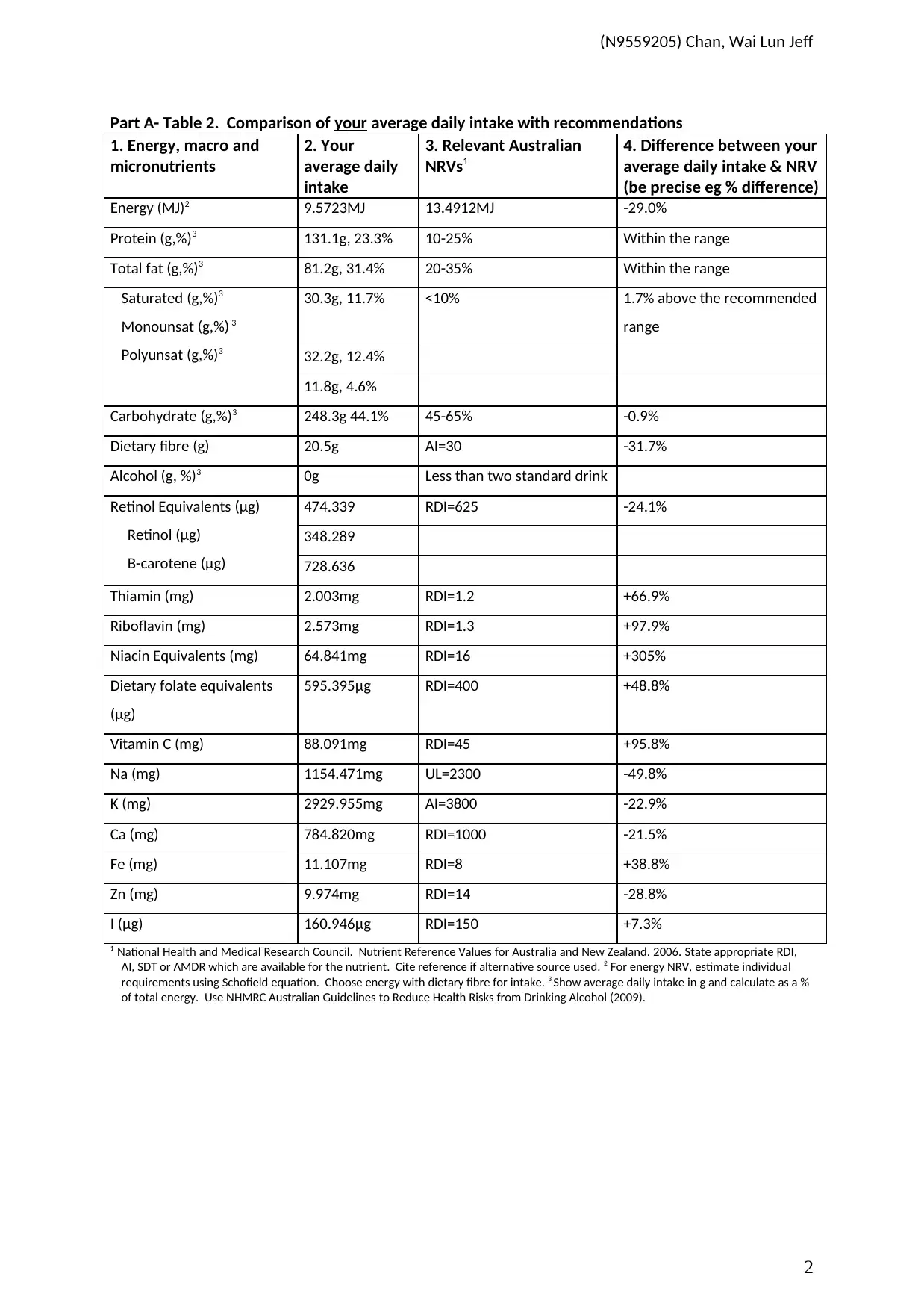

Part A- Table 2. Comparison of your average daily intake with recommendations

1. Energy, macro and

micronutrients

2. Your

average daily

intake

3. Relevant Australian

NRVs1

4. Difference between your

average daily intake & NRV

(be precise eg % difference)

Energy (MJ)2 9.5723MJ 13.4912MJ -29.0%

Protein (g,%)3 131.1g, 23.3% 10-25% Within the range

Total fat (g,%)3 81.2g, 31.4% 20-35% Within the range

Saturated (g,%)3

Monounsat (g,%) 3

Polyunsat (g,%)3

30.3g, 11.7% <10% 1.7% above the recommended

range

32.2g, 12.4%

11.8g, 4.6%

Carbohydrate (g,%)3 248.3g 44.1% 45-65% -0.9%

Dietary fibre (g) 20.5g AI=30 -31.7%

Alcohol (g, %)3 0g Less than two standard drink

Retinol Equivalents (μg)

Retinol (μg)

B-carotene (μg)

474.339 RDI=625 -24.1%

348.289

728.636

Thiamin (mg) 2.003mg RDI=1.2 +66.9%

Riboflavin (mg) 2.573mg RDI=1.3 +97.9%

Niacin Equivalents (mg) 64.841mg RDI=16 +305%

Dietary folate equivalents

(μg)

595.395μg RDI=400 +48.8%

Vitamin C (mg) 88.091mg RDI=45 +95.8%

Na (mg) 1154.471mg UL=2300 -49.8%

K (mg) 2929.955mg AI=3800 -22.9%

Ca (mg) 784.820mg RDI=1000 -21.5%

Fe (mg) 11.107mg RDI=8 +38.8%

Zn (mg) 9.974mg RDI=14 -28.8%

I (μg) 160.946μg RDI=150 +7.3%

1 National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. 2006. State appropriate RDI,

AI, SDT or AMDR which are available for the nutrient. Cite reference if alternative source used. 2 For energy NRV, estimate individual

requirements using Schofield equation. Choose energy with dietary fibre for intake. 3 Show average daily intake in g and calculate as a %

of total energy. Use NHMRC Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol (2009).

2

Part A- Table 2. Comparison of your average daily intake with recommendations

1. Energy, macro and

micronutrients

2. Your

average daily

intake

3. Relevant Australian

NRVs1

4. Difference between your

average daily intake & NRV

(be precise eg % difference)

Energy (MJ)2 9.5723MJ 13.4912MJ -29.0%

Protein (g,%)3 131.1g, 23.3% 10-25% Within the range

Total fat (g,%)3 81.2g, 31.4% 20-35% Within the range

Saturated (g,%)3

Monounsat (g,%) 3

Polyunsat (g,%)3

30.3g, 11.7% <10% 1.7% above the recommended

range

32.2g, 12.4%

11.8g, 4.6%

Carbohydrate (g,%)3 248.3g 44.1% 45-65% -0.9%

Dietary fibre (g) 20.5g AI=30 -31.7%

Alcohol (g, %)3 0g Less than two standard drink

Retinol Equivalents (μg)

Retinol (μg)

B-carotene (μg)

474.339 RDI=625 -24.1%

348.289

728.636

Thiamin (mg) 2.003mg RDI=1.2 +66.9%

Riboflavin (mg) 2.573mg RDI=1.3 +97.9%

Niacin Equivalents (mg) 64.841mg RDI=16 +305%

Dietary folate equivalents

(μg)

595.395μg RDI=400 +48.8%

Vitamin C (mg) 88.091mg RDI=45 +95.8%

Na (mg) 1154.471mg UL=2300 -49.8%

K (mg) 2929.955mg AI=3800 -22.9%

Ca (mg) 784.820mg RDI=1000 -21.5%

Fe (mg) 11.107mg RDI=8 +38.8%

Zn (mg) 9.974mg RDI=14 -28.8%

I (μg) 160.946μg RDI=150 +7.3%

1 National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. 2006. State appropriate RDI,

AI, SDT or AMDR which are available for the nutrient. Cite reference if alternative source used. 2 For energy NRV, estimate individual

requirements using Schofield equation. Choose energy with dietary fibre for intake. 3 Show average daily intake in g and calculate as a %

of total energy. Use NHMRC Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol (2009).

2

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

Task A2.

Answer A2: Two nutrients that are a priority for me to change:

As observed from the above, it is evident that my daily intake of calcium, is grossly less as compared

to the required values. Hence, one of the key nutrient changes which will prove to be a priority of

change in my respective diet, is my intake of dietary calcium. One of the key short term benefits

pertaining to the benefits of calcium intake, is its role in the provision of structural integrity to the

human body. Calcium comprises of the major foundational substance in the bones and teeth of the

human body, amounting to a percentage of over 1.6% to 2% (Lima et al., 2016). Hence, without

calcium, I would lose my required strength and integrity of bones and teeth outlining my body,

required for the optimum functioning of daily life tasks pertaining to basic weight bearing. Another

additional beneficial functioning of calcium, is for the purpose of coagulation and clotting of blood.

This is performed through the activation of the required coagulation factors via the functioning of

enzymes pertaining to proteolytic activities (Kyle et al., 2018). Calcium is also beneficial in the

functioning of digestion through the enhancement of the enzyme functioning such as nucleases,

proteases and phospholipidases. The secretion of the gastrointestinal digestive juices is also

activated through the expression of receptors pertaining to calcium ions (Ertan et al., 2015). Further,

calcium benefits for the human body are the enhancement of transmission of nerve impulses and

muscular contractions. This is conducted via the transmission of neurotransmitters from the

respective neurons which is conducted via ion channels containing calcium (Banerjee et al., 2016).

Hence, it is evident that the my intake of calcium is essential, not only for the maintenance of my

bone, teeth and overall structural components, but also in the development and enhancement of

basic strength, improve nervous system function, enhanced digestion and the resultant optimum

absorption of nutrients and the finally, for the purpose of optimum blood clotting for mitigation of

serious physical injuries. However, one of the key long term benefits of the calcium, is for the

maintenance of optimum bone health. Calcium is one of the cornerstone nutrients pertaining to the

functions of bone modelling and remodelling. The processes of bone modelling is outlined by the

various concentrations of bone as well as serum calcium concentrations, where osteoblasts facilitate

the repairing of bones, through the assimilation of calcium ion from the serum, via the functioning of

the calcitonin and parathyroid hormone. Further, for the adjustment of the serum calcium

concentrations, osteoclastic activity promptly engage in the resorption process through leeching of

bone calcium. Hence, if my calcium intake needs are not met, there would be a gross imbalance

between bone resorption and bone modelling functioning, further increasing my susceptibility to

bone related disorders such as osteoporosis and the resultant loss in bone strength and increased

rates of harmful fractures (Siddiqui & Partridge, 2016).

As observed table outlining nutrient intake, it can be observed that there also a deficiency in the

daily intake of dietary fibre. Dietary fibre, as is well known, is comprises of edible components of

food products which are insoluble by the regular digestive processes outlining the human body. The

purpose of dietary fibre is to add bulk to the stool formulation, leading to softening of stools and the

resultant ease in faecal evacuation of the body (Grundy et al., 2016). Hence, one of the short-term

benefits pertaining to the intake of dietary fibre, is the prevention of constipation. The negative

health implication of constipation due to lack of treatment for prolonged periods can pose a

detrimental impact on the daily life activities and overall well-being of any individual. High

occurrence of constipation has been associated with the prevalence of stools which are hard, further

leading to difficulty in evacuation. The resulting difficulty further leads to occurrence of tearing of

the tissues of the anus due to the presence of hard stools. The occurrence of such anal fissures is

also followed by the haemorrhoids, which is characterised by excessive swelling of the veins present

in the anal area, caused due to exertion of difficult stool evacuation (Kovacic et al., 2015). Further

lack of treatment can also result in the unwanted storage of stools which are hard and difficult to

evacuate, known as faecal. Hence, it is of utmost importance on my behalf, to increase my

consumption of dietary fibre, in order to reap the short-term benefits of removal of constipation and

the occurrence of further problems pertaining to possible rectal prolapsed, where excessive straining

and pressure for the purpose of stool evacuation can result in the protrusion of the intestine from

the anus (Ihana-Sugiyama et al., 2016). It is also worthwhile to mention that the consumption of

3

Task A2.

Answer A2: Two nutrients that are a priority for me to change:

As observed from the above, it is evident that my daily intake of calcium, is grossly less as compared

to the required values. Hence, one of the key nutrient changes which will prove to be a priority of

change in my respective diet, is my intake of dietary calcium. One of the key short term benefits

pertaining to the benefits of calcium intake, is its role in the provision of structural integrity to the

human body. Calcium comprises of the major foundational substance in the bones and teeth of the

human body, amounting to a percentage of over 1.6% to 2% (Lima et al., 2016). Hence, without

calcium, I would lose my required strength and integrity of bones and teeth outlining my body,

required for the optimum functioning of daily life tasks pertaining to basic weight bearing. Another

additional beneficial functioning of calcium, is for the purpose of coagulation and clotting of blood.

This is performed through the activation of the required coagulation factors via the functioning of

enzymes pertaining to proteolytic activities (Kyle et al., 2018). Calcium is also beneficial in the

functioning of digestion through the enhancement of the enzyme functioning such as nucleases,

proteases and phospholipidases. The secretion of the gastrointestinal digestive juices is also

activated through the expression of receptors pertaining to calcium ions (Ertan et al., 2015). Further,

calcium benefits for the human body are the enhancement of transmission of nerve impulses and

muscular contractions. This is conducted via the transmission of neurotransmitters from the

respective neurons which is conducted via ion channels containing calcium (Banerjee et al., 2016).

Hence, it is evident that the my intake of calcium is essential, not only for the maintenance of my

bone, teeth and overall structural components, but also in the development and enhancement of

basic strength, improve nervous system function, enhanced digestion and the resultant optimum

absorption of nutrients and the finally, for the purpose of optimum blood clotting for mitigation of

serious physical injuries. However, one of the key long term benefits of the calcium, is for the

maintenance of optimum bone health. Calcium is one of the cornerstone nutrients pertaining to the

functions of bone modelling and remodelling. The processes of bone modelling is outlined by the

various concentrations of bone as well as serum calcium concentrations, where osteoblasts facilitate

the repairing of bones, through the assimilation of calcium ion from the serum, via the functioning of

the calcitonin and parathyroid hormone. Further, for the adjustment of the serum calcium

concentrations, osteoclastic activity promptly engage in the resorption process through leeching of

bone calcium. Hence, if my calcium intake needs are not met, there would be a gross imbalance

between bone resorption and bone modelling functioning, further increasing my susceptibility to

bone related disorders such as osteoporosis and the resultant loss in bone strength and increased

rates of harmful fractures (Siddiqui & Partridge, 2016).

As observed table outlining nutrient intake, it can be observed that there also a deficiency in the

daily intake of dietary fibre. Dietary fibre, as is well known, is comprises of edible components of

food products which are insoluble by the regular digestive processes outlining the human body. The

purpose of dietary fibre is to add bulk to the stool formulation, leading to softening of stools and the

resultant ease in faecal evacuation of the body (Grundy et al., 2016). Hence, one of the short-term

benefits pertaining to the intake of dietary fibre, is the prevention of constipation. The negative

health implication of constipation due to lack of treatment for prolonged periods can pose a

detrimental impact on the daily life activities and overall well-being of any individual. High

occurrence of constipation has been associated with the prevalence of stools which are hard, further

leading to difficulty in evacuation. The resulting difficulty further leads to occurrence of tearing of

the tissues of the anus due to the presence of hard stools. The occurrence of such anal fissures is

also followed by the haemorrhoids, which is characterised by excessive swelling of the veins present

in the anal area, caused due to exertion of difficult stool evacuation (Kovacic et al., 2015). Further

lack of treatment can also result in the unwanted storage of stools which are hard and difficult to

evacuate, known as faecal. Hence, it is of utmost importance on my behalf, to increase my

consumption of dietary fibre, in order to reap the short-term benefits of removal of constipation and

the occurrence of further problems pertaining to possible rectal prolapsed, where excessive straining

and pressure for the purpose of stool evacuation can result in the protrusion of the intestine from

the anus (Ihana-Sugiyama et al., 2016). It is also worthwhile to mention that the consumption of

3

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

dietary fibre also results in beneficial long-term benefits. One of the key benefits is the reduction of

serum cholesterol levels , the increase in which can lead to further long term health complications of

cardiovascular diseases. Soluble fibre sources such as pectin from apples, beets and celery, along

with beta-glucan from oats, exhibit considerable gelling properties in the intestinal tract, resulting in

the accumulation and absorption of serum cholesterol, and their resultant excretion from the body

(Nwachukwu et al., 2015). The consumption of high insoluble and soluble fibre food components

have also been linked to the reduction in serum blood glucose levels, due to their high glycemic

index – a beneficial implication for the long-term prevention of diabetes mellitus. This is due to the

fact that the digestion and metabolism of fibre occurs without the absence of insulin, further

reducing the chances of fluctuations in blood glucose levels. Improved consumption of dietary fibre

is also an excellent way to maintain one’s weight in the long run, through provision of high satiety

and reduced food cravings (Solah et al., 2016).

Task A3.

Answer A3: Changes that I could make that would enable me to reach the NRC for the nutrients

identified:

As observed from my dietary nutrient intake mentioned above, there is a need for me to improve my

dietary calcium consumption, as evident from the resultant deficiency. For this purpose, I will be

required to the undertake key modification in the food intake pertaining to my daily diet. As

observed by my dietary recall, it is evident that my consumption of milk and milk products is

significantly low as compared to the recommended 2.5 servings of milk and milk products suggested

in the Australian Dietary Guidelines for the purpose of consumption on core food groups (Allman-

Farinelli et al., 2014). As observed, the only milk product which I am consuming is full cream milk

during breakfast. Hence, I must incorporate further sources of dairy products in my diet, due to them

being major sources of dietary calcium (Keast et al., 2015). However, since I am already consuming

milk every day in one meal, hence, I believe that inclusion of other dietary sources would be an

advantageous dietary amendment in order to prevent boredom and add variety to my diet. Hence, I

can consume dairy products like a 100 gram cup of yoghurt or a 20 gram slice of cheese for

increasing my calcium intake. However, plain yoghurt may again be food choice which may cause

boredom if consumed daily. Hence, to enhance is flavour, I believe that I can consume it with added

fruits and nuts, like 10 to 12 almonds or a medium sized apples, bananas and handful of berries. This

will not only turn out to be an interesting meal addition as a breakfast or snack, but will also be

beneficial in enhancing my fruit intake, which I am also deficient in, as opined by the Australian

Dietary Guidelines recommendation of two servings (Allaman-Farinelli et al., 2014). Opting for

probiotic yoghurt would be good option, for the enhanced intake of calcium, as well as improved

digestion and immunity exhibited by my gut microflora (Bosnia et al., 2017). Additional dietary

changes which can be incorporated is the inclusion of cheese which will not only be a delicious

addition to my diet, but also prove to be a good source of calcium (Aune et al., 2014). However, I

must ensure that the consumption of cheese is limited since it is also a rich source of saturated fats,

which may put me at a risk of increased serum cholesterol and the resultant cardiovascular diseases

susceptibility (Thorning et al., 2015). Further considering fat intake, it is worthwhile to mention that

the full cream milk which I am consuming daily, is also a high source of saturated fat, which may

result in harmful health complications by increasing my dietary fat intake. Hence, there is a need to

consume milk which is of reduced fat, which is mainly skimmed or double toned milk (Chen et al.,

2016). This will meet my calcium needs, along with the reduced intake of harmful fat sources.

However, due to my habit of consuming the richness and creaminess of full fat milk, adjusting to

skimmed milk may pose to be a challenge due to its thinner texture. Hence, I believe gradually

reducing my full cream milk intake and gradually increasing skimmed milk intake, would be beneficial

in modifying my taste. The consumption of Vitamin D is to be taken under due consideration, since

this vitamin is closely associated with the functioning of the parathyroid hormones and the resultant

calcium absorption and functioning. Hence, exposure to increase sunlight, and incorporation of eggs

and small amounts of fortified butter and mushrooms, would be a beneficial due to their

enhancement of Vitamin D in the body, further enhancing calcium absorption (Cashman, 2015).

4

dietary fibre also results in beneficial long-term benefits. One of the key benefits is the reduction of

serum cholesterol levels , the increase in which can lead to further long term health complications of

cardiovascular diseases. Soluble fibre sources such as pectin from apples, beets and celery, along

with beta-glucan from oats, exhibit considerable gelling properties in the intestinal tract, resulting in

the accumulation and absorption of serum cholesterol, and their resultant excretion from the body

(Nwachukwu et al., 2015). The consumption of high insoluble and soluble fibre food components

have also been linked to the reduction in serum blood glucose levels, due to their high glycemic

index – a beneficial implication for the long-term prevention of diabetes mellitus. This is due to the

fact that the digestion and metabolism of fibre occurs without the absence of insulin, further

reducing the chances of fluctuations in blood glucose levels. Improved consumption of dietary fibre

is also an excellent way to maintain one’s weight in the long run, through provision of high satiety

and reduced food cravings (Solah et al., 2016).

Task A3.

Answer A3: Changes that I could make that would enable me to reach the NRC for the nutrients

identified:

As observed from my dietary nutrient intake mentioned above, there is a need for me to improve my

dietary calcium consumption, as evident from the resultant deficiency. For this purpose, I will be

required to the undertake key modification in the food intake pertaining to my daily diet. As

observed by my dietary recall, it is evident that my consumption of milk and milk products is

significantly low as compared to the recommended 2.5 servings of milk and milk products suggested

in the Australian Dietary Guidelines for the purpose of consumption on core food groups (Allman-

Farinelli et al., 2014). As observed, the only milk product which I am consuming is full cream milk

during breakfast. Hence, I must incorporate further sources of dairy products in my diet, due to them

being major sources of dietary calcium (Keast et al., 2015). However, since I am already consuming

milk every day in one meal, hence, I believe that inclusion of other dietary sources would be an

advantageous dietary amendment in order to prevent boredom and add variety to my diet. Hence, I

can consume dairy products like a 100 gram cup of yoghurt or a 20 gram slice of cheese for

increasing my calcium intake. However, plain yoghurt may again be food choice which may cause

boredom if consumed daily. Hence, to enhance is flavour, I believe that I can consume it with added

fruits and nuts, like 10 to 12 almonds or a medium sized apples, bananas and handful of berries. This

will not only turn out to be an interesting meal addition as a breakfast or snack, but will also be

beneficial in enhancing my fruit intake, which I am also deficient in, as opined by the Australian

Dietary Guidelines recommendation of two servings (Allaman-Farinelli et al., 2014). Opting for

probiotic yoghurt would be good option, for the enhanced intake of calcium, as well as improved

digestion and immunity exhibited by my gut microflora (Bosnia et al., 2017). Additional dietary

changes which can be incorporated is the inclusion of cheese which will not only be a delicious

addition to my diet, but also prove to be a good source of calcium (Aune et al., 2014). However, I

must ensure that the consumption of cheese is limited since it is also a rich source of saturated fats,

which may put me at a risk of increased serum cholesterol and the resultant cardiovascular diseases

susceptibility (Thorning et al., 2015). Further considering fat intake, it is worthwhile to mention that

the full cream milk which I am consuming daily, is also a high source of saturated fat, which may

result in harmful health complications by increasing my dietary fat intake. Hence, there is a need to

consume milk which is of reduced fat, which is mainly skimmed or double toned milk (Chen et al.,

2016). This will meet my calcium needs, along with the reduced intake of harmful fat sources.

However, due to my habit of consuming the richness and creaminess of full fat milk, adjusting to

skimmed milk may pose to be a challenge due to its thinner texture. Hence, I believe gradually

reducing my full cream milk intake and gradually increasing skimmed milk intake, would be beneficial

in modifying my taste. The consumption of Vitamin D is to be taken under due consideration, since

this vitamin is closely associated with the functioning of the parathyroid hormones and the resultant

calcium absorption and functioning. Hence, exposure to increase sunlight, and incorporation of eggs

and small amounts of fortified butter and mushrooms, would be a beneficial due to their

enhancement of Vitamin D in the body, further enhancing calcium absorption (Cashman, 2015).

4

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

Additional dietary changes are required in my diet, as evident from my reduced intake of dietary

fibre. It is to be noted that the recommended Australian Dietary Guidelines, place emphasis on the

consumption of the core food groups of vegetables, legumes and pulses to a total of six servings

(Allaman-Farinelli et al., 2014), which is grossly less in my diet, as evident in my dietary recall. Green

leafy vegetables are excellent sources of dietary fibre of the insoluble type, which will aid in the

prevention of constipation along with the enhancement of faecal movement (Dodevska, Šobajić, &

Đorđević, 2015). Hence, I must incorporate 5 to 6 servings of vegetables per day to meet my fibre

requirements. Another way of enhancing my dietary fibre intake, is through the intake of fruits such

as bananas, apples and citrus fruits to 2 servings, which are good a source of soluble fibre pectin

(Oliveira et al., 2016). Incorporation of oats will also be a novel dietary strategy, due to is high

reservoir of beta glucan - soluble dietary fibre associated with reduction in blood cholesterol and

blood sugar, further resulting in reduced susceptibility towards metabolic disorders such as

cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Schloermann & Glei, 2017). However, since I have never

consumed oats before, gradual changes are required in order to induce adjustment to its mushy

texture. An additional dietary intake change would be the incorporation of whole grains in my diet in

the form of multigrain breads and whole grain rice, in order to enhance my intake of dietary fibre

(Buil-Cosiales et al., 2016). However, it is worthwhile to mention that with the enhancement in fibre,

the textural qualities of the food product changes, resulting in whole grain breads and rice being

tougher and difficult to digest, which may act as a barrier for me during dietary incorporation. Also,

one of the major qualities of dietary fibre is the increase in satiety resulting in reduce food intake

and the resultant weight maintenance. However, excessive dietary fibre intake can also reduce my

water intake due to high satiety (Stephen et al., 2017). In addition, excessive intake of dietary fibre

has also been observed to reduce the bioavailability of minerals such as iron, magnesium, zinc,

phosphorous and calcium, by reducing their absorption (Baye Guyot & Mouquet-Rivier, 2017). In

addition, excessive dietary fibre intake has also been associated with high incidences of flatulence,

bloating and idiopathic constipation due to formation of dry stools (Christodoulides et al., 2016).

Hence, such barriers can prove to be detrimental to my dietary fibre consumption and hence, I must

incorporate fibre rich foods in my diet in controlled amounts.

In addition to the above dietary changes and the possible barriers, a major hurdle for me is my busy

academic life. Time constraints are a major factor which act as a barrier for me eat timely, healthy

meals. Also, another importance barrier is financial constraint, making it further difficult for me to

purchase food items like nuts, fruits, vegetables and the added whole grains and skimmed milk food

sources.

5

Additional dietary changes are required in my diet, as evident from my reduced intake of dietary

fibre. It is to be noted that the recommended Australian Dietary Guidelines, place emphasis on the

consumption of the core food groups of vegetables, legumes and pulses to a total of six servings

(Allaman-Farinelli et al., 2014), which is grossly less in my diet, as evident in my dietary recall. Green

leafy vegetables are excellent sources of dietary fibre of the insoluble type, which will aid in the

prevention of constipation along with the enhancement of faecal movement (Dodevska, Šobajić, &

Đorđević, 2015). Hence, I must incorporate 5 to 6 servings of vegetables per day to meet my fibre

requirements. Another way of enhancing my dietary fibre intake, is through the intake of fruits such

as bananas, apples and citrus fruits to 2 servings, which are good a source of soluble fibre pectin

(Oliveira et al., 2016). Incorporation of oats will also be a novel dietary strategy, due to is high

reservoir of beta glucan - soluble dietary fibre associated with reduction in blood cholesterol and

blood sugar, further resulting in reduced susceptibility towards metabolic disorders such as

cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Schloermann & Glei, 2017). However, since I have never

consumed oats before, gradual changes are required in order to induce adjustment to its mushy

texture. An additional dietary intake change would be the incorporation of whole grains in my diet in

the form of multigrain breads and whole grain rice, in order to enhance my intake of dietary fibre

(Buil-Cosiales et al., 2016). However, it is worthwhile to mention that with the enhancement in fibre,

the textural qualities of the food product changes, resulting in whole grain breads and rice being

tougher and difficult to digest, which may act as a barrier for me during dietary incorporation. Also,

one of the major qualities of dietary fibre is the increase in satiety resulting in reduce food intake

and the resultant weight maintenance. However, excessive dietary fibre intake can also reduce my

water intake due to high satiety (Stephen et al., 2017). In addition, excessive intake of dietary fibre

has also been observed to reduce the bioavailability of minerals such as iron, magnesium, zinc,

phosphorous and calcium, by reducing their absorption (Baye Guyot & Mouquet-Rivier, 2017). In

addition, excessive dietary fibre intake has also been associated with high incidences of flatulence,

bloating and idiopathic constipation due to formation of dry stools (Christodoulides et al., 2016).

Hence, such barriers can prove to be detrimental to my dietary fibre consumption and hence, I must

incorporate fibre rich foods in my diet in controlled amounts.

In addition to the above dietary changes and the possible barriers, a major hurdle for me is my busy

academic life. Time constraints are a major factor which act as a barrier for me eat timely, healthy

meals. Also, another importance barrier is financial constraint, making it further difficult for me to

purchase food items like nuts, fruits, vegetables and the added whole grains and skimmed milk food

sources.

5

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

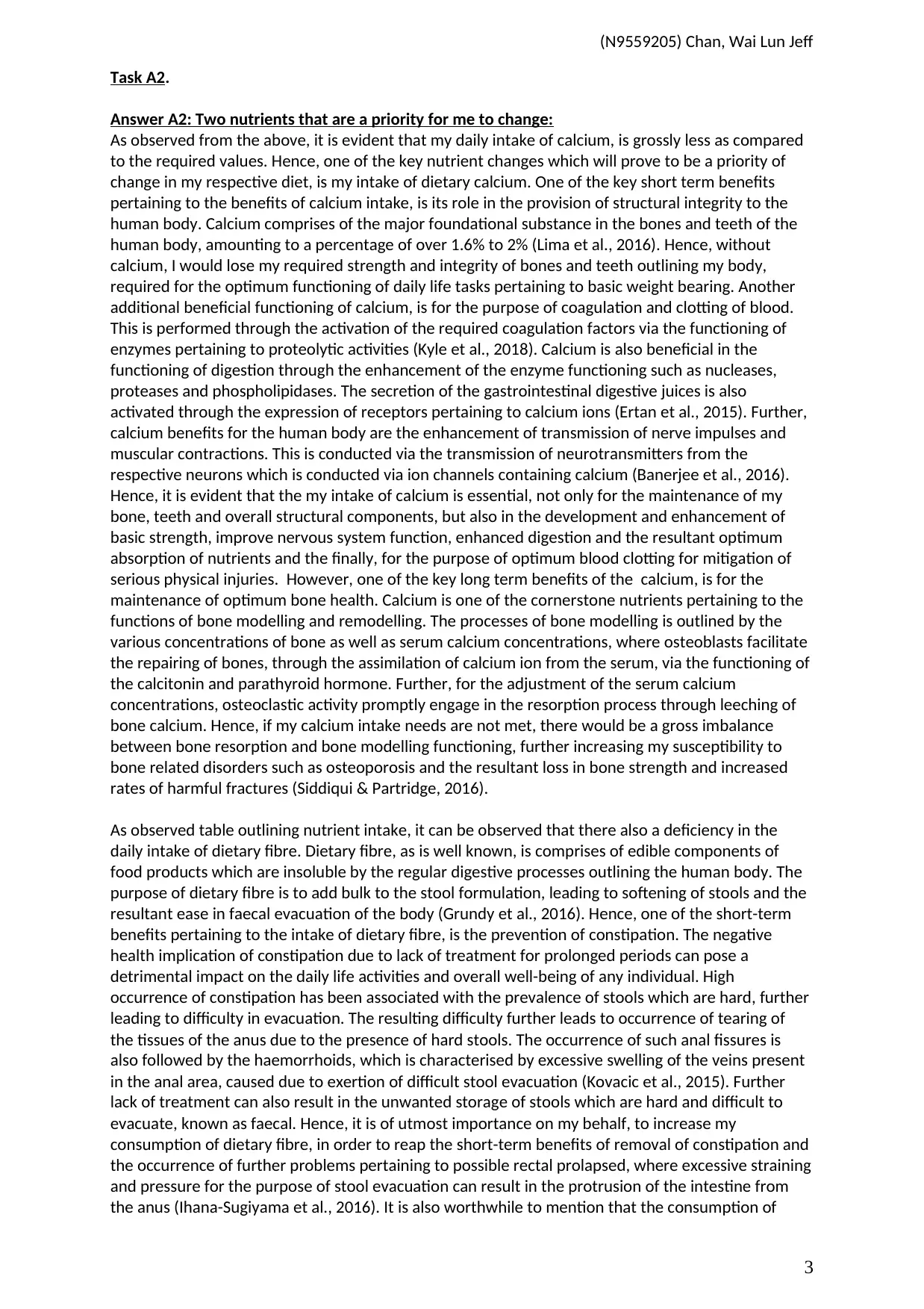

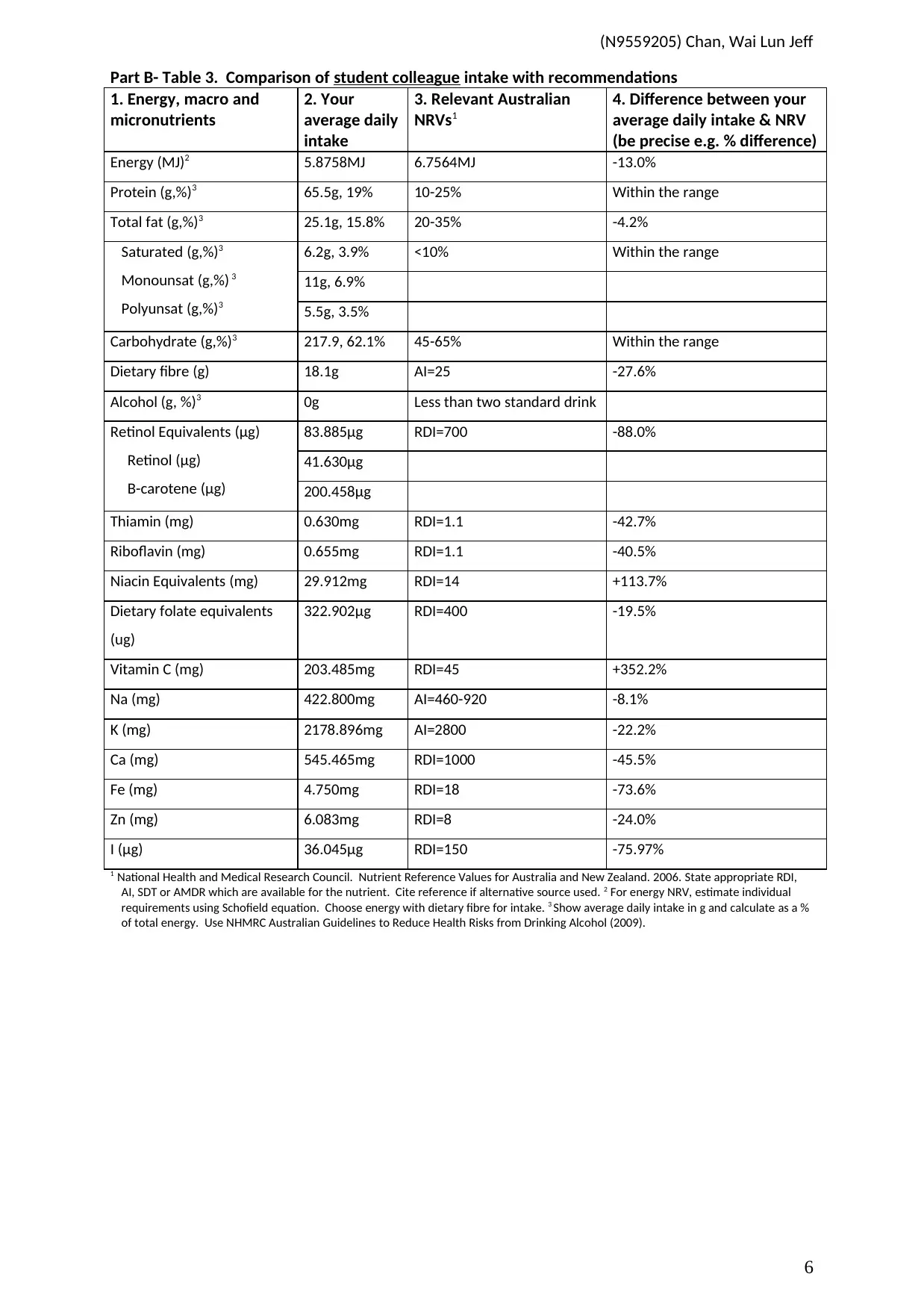

Part B- Table 3. Comparison of student colleague intake with recommendations

1. Energy, macro and

micronutrients

2. Your

average daily

intake

3. Relevant Australian

NRVs1

4. Difference between your

average daily intake & NRV

(be precise e.g. % difference)

Energy (MJ)2 5.8758MJ 6.7564MJ -13.0%

Protein (g,%)3 65.5g, 19% 10-25% Within the range

Total fat (g,%)3 25.1g, 15.8% 20-35% -4.2%

Saturated (g,%)3

Monounsat (g,%) 3

Polyunsat (g,%)3

6.2g, 3.9% <10% Within the range

11g, 6.9%

5.5g, 3.5%

Carbohydrate (g,%)3 217.9, 62.1% 45-65% Within the range

Dietary fibre (g) 18.1g AI=25 -27.6%

Alcohol (g, %)3 0g Less than two standard drink

Retinol Equivalents (μg)

Retinol (μg)

B-carotene (μg)

83.885μg RDI=700 -88.0%

41.630μg

200.458μg

Thiamin (mg) 0.630mg RDI=1.1 -42.7%

Riboflavin (mg) 0.655mg RDI=1.1 -40.5%

Niacin Equivalents (mg) 29.912mg RDI=14 +113.7%

Dietary folate equivalents

(ug)

322.902μg RDI=400 -19.5%

Vitamin C (mg) 203.485mg RDI=45 +352.2%

Na (mg) 422.800mg AI=460-920 -8.1%

K (mg) 2178.896mg AI=2800 -22.2%

Ca (mg) 545.465mg RDI=1000 -45.5%

Fe (mg) 4.750mg RDI=18 -73.6%

Zn (mg) 6.083mg RDI=8 -24.0%

I (μg) 36.045μg RDI=150 -75.97%

1 National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. 2006. State appropriate RDI,

AI, SDT or AMDR which are available for the nutrient. Cite reference if alternative source used. 2 For energy NRV, estimate individual

requirements using Schofield equation. Choose energy with dietary fibre for intake. 3 Show average daily intake in g and calculate as a %

of total energy. Use NHMRC Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol (2009).

6

Part B- Table 3. Comparison of student colleague intake with recommendations

1. Energy, macro and

micronutrients

2. Your

average daily

intake

3. Relevant Australian

NRVs1

4. Difference between your

average daily intake & NRV

(be precise e.g. % difference)

Energy (MJ)2 5.8758MJ 6.7564MJ -13.0%

Protein (g,%)3 65.5g, 19% 10-25% Within the range

Total fat (g,%)3 25.1g, 15.8% 20-35% -4.2%

Saturated (g,%)3

Monounsat (g,%) 3

Polyunsat (g,%)3

6.2g, 3.9% <10% Within the range

11g, 6.9%

5.5g, 3.5%

Carbohydrate (g,%)3 217.9, 62.1% 45-65% Within the range

Dietary fibre (g) 18.1g AI=25 -27.6%

Alcohol (g, %)3 0g Less than two standard drink

Retinol Equivalents (μg)

Retinol (μg)

B-carotene (μg)

83.885μg RDI=700 -88.0%

41.630μg

200.458μg

Thiamin (mg) 0.630mg RDI=1.1 -42.7%

Riboflavin (mg) 0.655mg RDI=1.1 -40.5%

Niacin Equivalents (mg) 29.912mg RDI=14 +113.7%

Dietary folate equivalents

(ug)

322.902μg RDI=400 -19.5%

Vitamin C (mg) 203.485mg RDI=45 +352.2%

Na (mg) 422.800mg AI=460-920 -8.1%

K (mg) 2178.896mg AI=2800 -22.2%

Ca (mg) 545.465mg RDI=1000 -45.5%

Fe (mg) 4.750mg RDI=18 -73.6%

Zn (mg) 6.083mg RDI=8 -24.0%

I (μg) 36.045μg RDI=150 -75.97%

1 National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. 2006. State appropriate RDI,

AI, SDT or AMDR which are available for the nutrient. Cite reference if alternative source used. 2 For energy NRV, estimate individual

requirements using Schofield equation. Choose energy with dietary fibre for intake. 3 Show average daily intake in g and calculate as a %

of total energy. Use NHMRC Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol (2009).

6

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

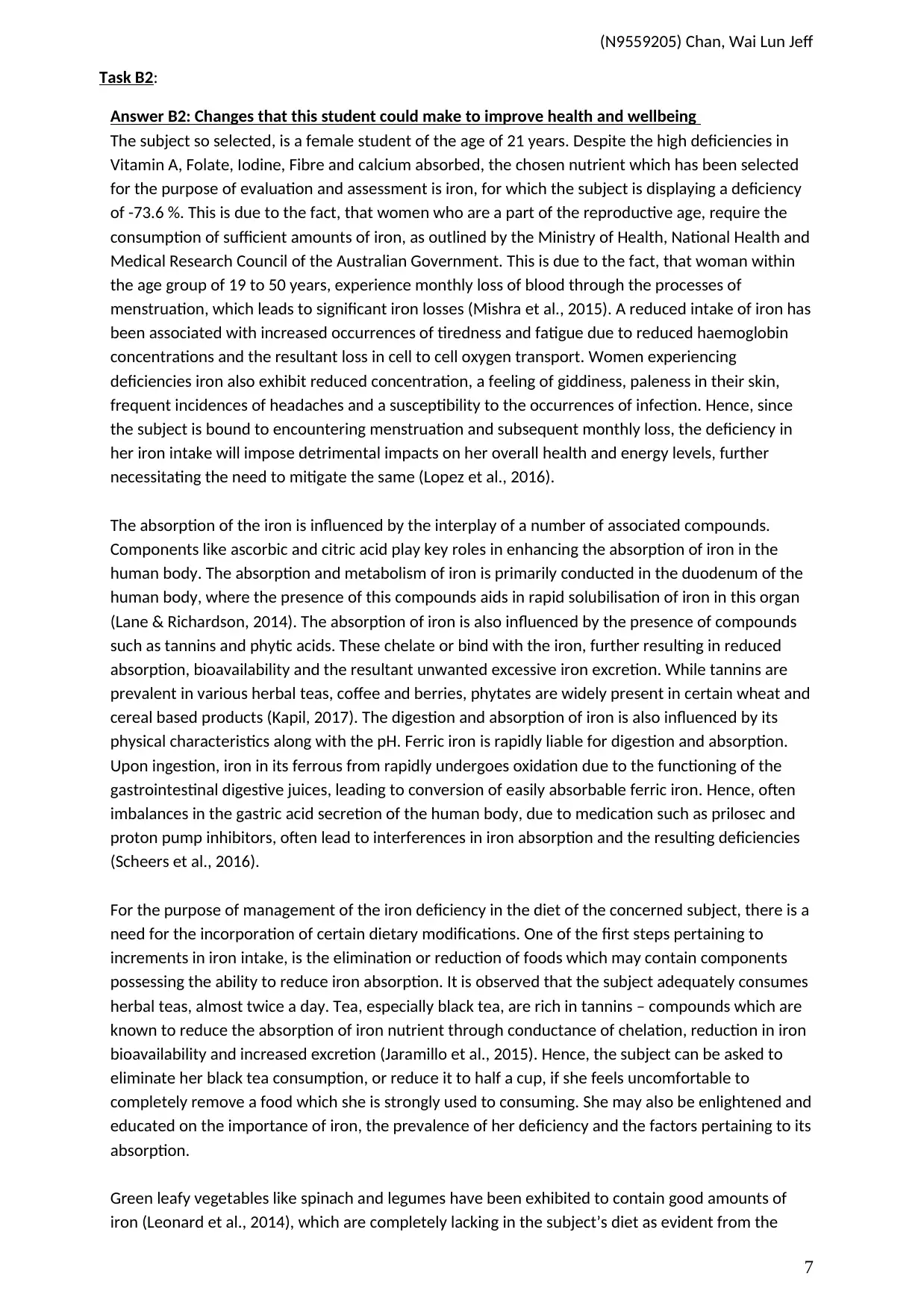

Task B2:

Answer B2: Changes that this student could make to improve health and wellbeing

The subject so selected, is a female student of the age of 21 years. Despite the high deficiencies in

Vitamin A, Folate, Iodine, Fibre and calcium absorbed, the chosen nutrient which has been selected

for the purpose of evaluation and assessment is iron, for which the subject is displaying a deficiency

of -73.6 %. This is due to the fact, that women who are a part of the reproductive age, require the

consumption of sufficient amounts of iron, as outlined by the Ministry of Health, National Health and

Medical Research Council of the Australian Government. This is due to the fact, that woman within

the age group of 19 to 50 years, experience monthly loss of blood through the processes of

menstruation, which leads to significant iron losses (Mishra et al., 2015). A reduced intake of iron has

been associated with increased occurrences of tiredness and fatigue due to reduced haemoglobin

concentrations and the resultant loss in cell to cell oxygen transport. Women experiencing

deficiencies iron also exhibit reduced concentration, a feeling of giddiness, paleness in their skin,

frequent incidences of headaches and a susceptibility to the occurrences of infection. Hence, since

the subject is bound to encountering menstruation and subsequent monthly loss, the deficiency in

her iron intake will impose detrimental impacts on her overall health and energy levels, further

necessitating the need to mitigate the same (Lopez et al., 2016).

The absorption of the iron is influenced by the interplay of a number of associated compounds.

Components like ascorbic and citric acid play key roles in enhancing the absorption of iron in the

human body. The absorption and metabolism of iron is primarily conducted in the duodenum of the

human body, where the presence of this compounds aids in rapid solubilisation of iron in this organ

(Lane & Richardson, 2014). The absorption of iron is also influenced by the presence of compounds

such as tannins and phytic acids. These chelate or bind with the iron, further resulting in reduced

absorption, bioavailability and the resultant unwanted excessive iron excretion. While tannins are

prevalent in various herbal teas, coffee and berries, phytates are widely present in certain wheat and

cereal based products (Kapil, 2017). The digestion and absorption of iron is also influenced by its

physical characteristics along with the pH. Ferric iron is rapidly liable for digestion and absorption.

Upon ingestion, iron in its ferrous from rapidly undergoes oxidation due to the functioning of the

gastrointestinal digestive juices, leading to conversion of easily absorbable ferric iron. Hence, often

imbalances in the gastric acid secretion of the human body, due to medication such as prilosec and

proton pump inhibitors, often lead to interferences in iron absorption and the resulting deficiencies

(Scheers et al., 2016).

For the purpose of management of the iron deficiency in the diet of the concerned subject, there is a

need for the incorporation of certain dietary modifications. One of the first steps pertaining to

increments in iron intake, is the elimination or reduction of foods which may contain components

possessing the ability to reduce iron absorption. It is observed that the subject adequately consumes

herbal teas, almost twice a day. Tea, especially black tea, are rich in tannins – compounds which are

known to reduce the absorption of iron nutrient through conductance of chelation, reduction in iron

bioavailability and increased excretion (Jaramillo et al., 2015). Hence, the subject can be asked to

eliminate her black tea consumption, or reduce it to half a cup, if she feels uncomfortable to

completely remove a food which she is strongly used to consuming. She may also be enlightened and

educated on the importance of iron, the prevalence of her deficiency and the factors pertaining to its

absorption.

Green leafy vegetables like spinach and legumes have been exhibited to contain good amounts of

iron (Leonard et al., 2014), which are completely lacking in the subject’s diet as evident from the

7

Task B2:

Answer B2: Changes that this student could make to improve health and wellbeing

The subject so selected, is a female student of the age of 21 years. Despite the high deficiencies in

Vitamin A, Folate, Iodine, Fibre and calcium absorbed, the chosen nutrient which has been selected

for the purpose of evaluation and assessment is iron, for which the subject is displaying a deficiency

of -73.6 %. This is due to the fact, that women who are a part of the reproductive age, require the

consumption of sufficient amounts of iron, as outlined by the Ministry of Health, National Health and

Medical Research Council of the Australian Government. This is due to the fact, that woman within

the age group of 19 to 50 years, experience monthly loss of blood through the processes of

menstruation, which leads to significant iron losses (Mishra et al., 2015). A reduced intake of iron has

been associated with increased occurrences of tiredness and fatigue due to reduced haemoglobin

concentrations and the resultant loss in cell to cell oxygen transport. Women experiencing

deficiencies iron also exhibit reduced concentration, a feeling of giddiness, paleness in their skin,

frequent incidences of headaches and a susceptibility to the occurrences of infection. Hence, since

the subject is bound to encountering menstruation and subsequent monthly loss, the deficiency in

her iron intake will impose detrimental impacts on her overall health and energy levels, further

necessitating the need to mitigate the same (Lopez et al., 2016).

The absorption of the iron is influenced by the interplay of a number of associated compounds.

Components like ascorbic and citric acid play key roles in enhancing the absorption of iron in the

human body. The absorption and metabolism of iron is primarily conducted in the duodenum of the

human body, where the presence of this compounds aids in rapid solubilisation of iron in this organ

(Lane & Richardson, 2014). The absorption of iron is also influenced by the presence of compounds

such as tannins and phytic acids. These chelate or bind with the iron, further resulting in reduced

absorption, bioavailability and the resultant unwanted excessive iron excretion. While tannins are

prevalent in various herbal teas, coffee and berries, phytates are widely present in certain wheat and

cereal based products (Kapil, 2017). The digestion and absorption of iron is also influenced by its

physical characteristics along with the pH. Ferric iron is rapidly liable for digestion and absorption.

Upon ingestion, iron in its ferrous from rapidly undergoes oxidation due to the functioning of the

gastrointestinal digestive juices, leading to conversion of easily absorbable ferric iron. Hence, often

imbalances in the gastric acid secretion of the human body, due to medication such as prilosec and

proton pump inhibitors, often lead to interferences in iron absorption and the resulting deficiencies

(Scheers et al., 2016).

For the purpose of management of the iron deficiency in the diet of the concerned subject, there is a

need for the incorporation of certain dietary modifications. One of the first steps pertaining to

increments in iron intake, is the elimination or reduction of foods which may contain components

possessing the ability to reduce iron absorption. It is observed that the subject adequately consumes

herbal teas, almost twice a day. Tea, especially black tea, are rich in tannins – compounds which are

known to reduce the absorption of iron nutrient through conductance of chelation, reduction in iron

bioavailability and increased excretion (Jaramillo et al., 2015). Hence, the subject can be asked to

eliminate her black tea consumption, or reduce it to half a cup, if she feels uncomfortable to

completely remove a food which she is strongly used to consuming. She may also be enlightened and

educated on the importance of iron, the prevalence of her deficiency and the factors pertaining to its

absorption.

Green leafy vegetables like spinach and legumes have been exhibited to contain good amounts of

iron (Leonard et al., 2014), which are completely lacking in the subject’s diet as evident from the

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

recall. Hence, instead of simply having cabbage for lunch and dinner, she may consume a big bowl of

hearty vegetable and legume salads or curries which can improve her intake of iron. However, it is to

be noted that legumes often contain phytates which may interfere with iron absorption. Cooking the

legumes and vegetables thoroughly, or germinating the legume grains can be a beneficial step to

eliminate these detrimental compounds and enhance availability of iron (Mihafu et al., 2017).

Consequently, iron absorption is influenced by the consumption of vitamin C (Prentice et al., 2016).

Hence, squeezing some lime juice into her vegetable dish would be a beneficial way to enhance her

Vitamin C intake and the resultant increase in absorption of iron, since limes and lemons are good

sources of this vitamin (Zou et al., 2016).

Nuts like almonds are also rich sources of iron (Zivoli, 2017), which is consequently lacking in the

subject’s food intake, as evident from her dietary recall. Also, the subject only engages in

consumption of three meals a day, and hence, the inclusion of a snack would be a beneficial

implication for her diet. As a snack, the concerned subject can consume one serving, or 10 to 12 nuts

in between meals, for the purpose of adequate iron intake. Consequently, whole grain products such

as multigrain breads and whole grain rice, are also good sources of iron. However, care has to be

taken and excessive consumption of these recommended options should be avoided by the

concerned subject. This is due to the fact that whole grain cereal products are good sources of fibre,

which have been known to reduce iron absorption. Cereal based products also contain phytates

which have been known to exhibit reduced iron bioavailability, hence necessitating the need to

carefully consider these options (Rebello, Green way & Finley, 2014).

8

recall. Hence, instead of simply having cabbage for lunch and dinner, she may consume a big bowl of

hearty vegetable and legume salads or curries which can improve her intake of iron. However, it is to

be noted that legumes often contain phytates which may interfere with iron absorption. Cooking the

legumes and vegetables thoroughly, or germinating the legume grains can be a beneficial step to

eliminate these detrimental compounds and enhance availability of iron (Mihafu et al., 2017).

Consequently, iron absorption is influenced by the consumption of vitamin C (Prentice et al., 2016).

Hence, squeezing some lime juice into her vegetable dish would be a beneficial way to enhance her

Vitamin C intake and the resultant increase in absorption of iron, since limes and lemons are good

sources of this vitamin (Zou et al., 2016).

Nuts like almonds are also rich sources of iron (Zivoli, 2017), which is consequently lacking in the

subject’s food intake, as evident from her dietary recall. Also, the subject only engages in

consumption of three meals a day, and hence, the inclusion of a snack would be a beneficial

implication for her diet. As a snack, the concerned subject can consume one serving, or 10 to 12 nuts

in between meals, for the purpose of adequate iron intake. Consequently, whole grain products such

as multigrain breads and whole grain rice, are also good sources of iron. However, care has to be

taken and excessive consumption of these recommended options should be avoided by the

concerned subject. This is due to the fact that whole grain cereal products are good sources of fibre,

which have been known to reduce iron absorption. Cereal based products also contain phytates

which have been known to exhibit reduced iron bioavailability, hence necessitating the need to

carefully consider these options (Rebello, Green way & Finley, 2014).

8

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

9

9

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

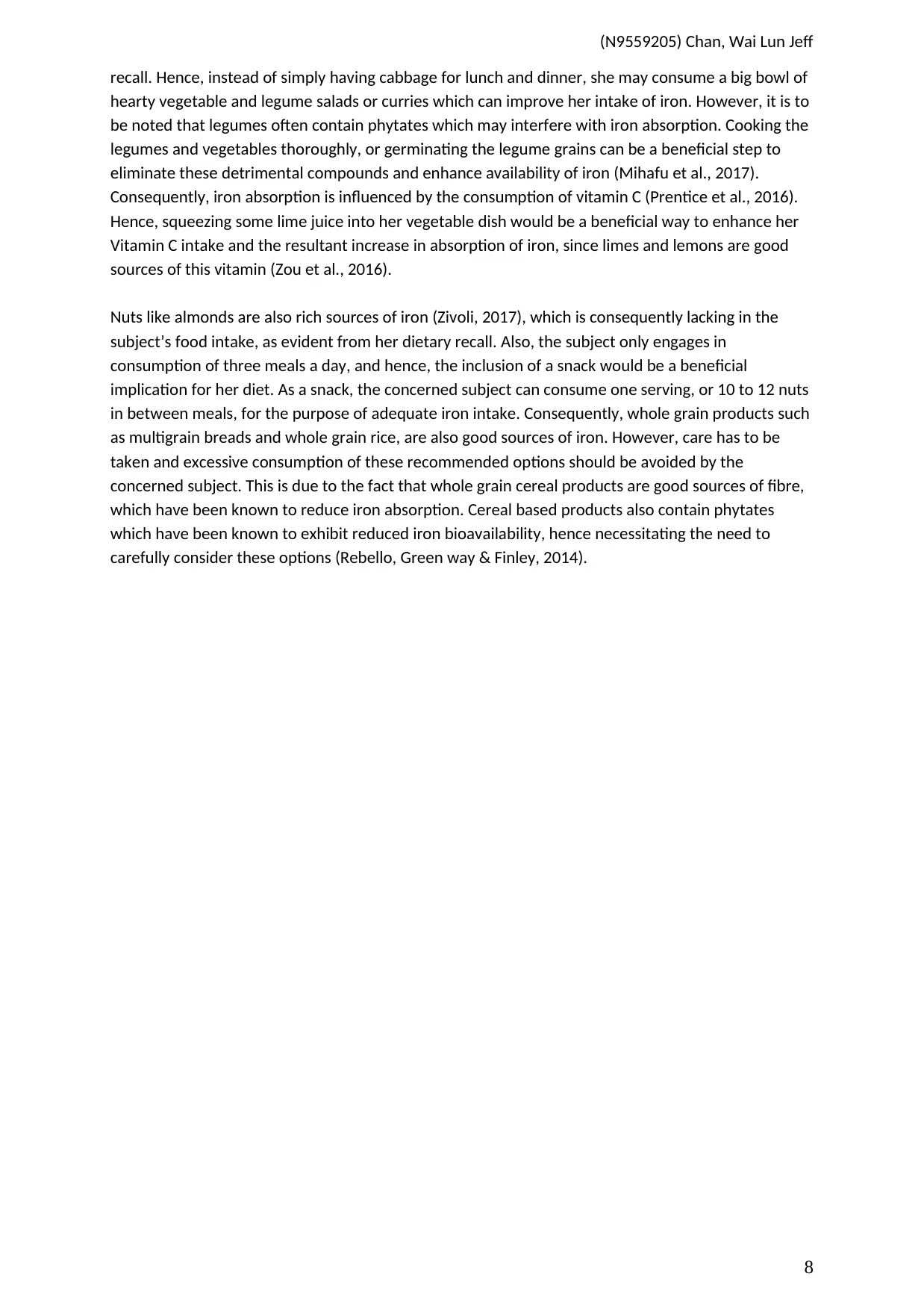

Part D - Table 4 Reflection on confidence in using the ready reckoner method

Reporting and responding

For the purpose of assessing the dietary intake of the patients, a number of evaluation tools continue to be

utilised. The usage of computerised analysis of the same, are usually recommended pertaining to their high

levels of accuracy and detailed nutrient profile exhibition of a large range of nutrients. However, the usage

of computerized analysis like ‘Foodworks’ often create hindrance due to the large amount of time required

for nutrient assessment. Despite the presence of a vast database of food items, such applications are often

expensive and require professional observation in order to derive the necessary data analysis and

interpretation (Paciepnik & Porter, 2017). With respect to this, I believe that the Ready Reckoner method is

a an effective tool which is highly simple due to its convenient evaluation of wide variety of food groups in

the form of average food values. Hence, for future use, I believe that we can apply the Ready Reckoner

method for nutrient analysis, since it financially feasible, requires less time in presenting the calculations

and is also easy to interpret by any individual lacking sufficient knowledge in nutrition. However, I still lack

sufficient confidence to use the Ready Reckoner method. This is because certain food groups such as Grains

Group 1 and 2, do not specify the intake of specific cereal based products such as spaghetti or instant

noodles. There is also no mention of beverages such as energy or coffee-based drinks, making it further

difficult to use. There is also no specification of the vegetables since this group comprises of a vast array of

items with varied weights and grouping them under ‘Moderate’ and ‘Low CHO’ is insufficient. Hence,

despite the simplicity, I believe that changes such as inclusion of additional food groups and specifications

under the grains and vegetables groups are required before applying full confidence in the Ready Reckoner

method.

Relating

Based on the occurrences of my previous experiences, I faced certain advantages as well as limitations in

my usage of various assessment methods such as 24 hour diet recall, weighed food record and the Ready

Reckoner Method. With respect to the weight food record, it is considered as one of the most

advantageous and comprehensive dietary assessment plan, as evident by the availability of the various

detailed food ingredients, the weight and the cooking procedures used by the subject (Martin et al., 2014).

However, while working with this assessment, I found it to be highly time consuming, and requires a lot of

communication between me and my clients, often resulting in difficulties in understanding. Due to high

effort and time required, I believe that this method may produce inaccurate results, since I have noticed

difficulties recalling accurate measurements by the clients. With respect, I believe that the usage of a 24-

hour recall is much easier, and participants are less likely to produce inaccurate information, due to

recording of previous day’s foods. Despite its efficiency with literate as well as illiterate subjects, I still

difficulty while interviewing, since careful questioning is required to elicit the requires responses. There is

also great difficulty if am required to undertake a 3 day recall, since participants find it very difficult to

remember. In my experience of Foodworks, I have found it to be highly accurate tool due to its large

database including various food items. However, I find it very time consuming where I am required to

explain clients in depth considering the results, since most of them lack sufficient nutritional knowledge.

With this respect, the Ready Reckoner method is highly effective in terms of convenience and simplicity, as I

can easily explain the results to the clients. However, I find it incomplete due to lack of specification of

several groups. Hence, based on relation to my experiences, I feel that instead of focusing on one method,

usage of multiple assessment methods would have been helpful for me in explaining the dietary needs of

the client.

10

Part D - Table 4 Reflection on confidence in using the ready reckoner method

Reporting and responding

For the purpose of assessing the dietary intake of the patients, a number of evaluation tools continue to be

utilised. The usage of computerised analysis of the same, are usually recommended pertaining to their high

levels of accuracy and detailed nutrient profile exhibition of a large range of nutrients. However, the usage

of computerized analysis like ‘Foodworks’ often create hindrance due to the large amount of time required

for nutrient assessment. Despite the presence of a vast database of food items, such applications are often

expensive and require professional observation in order to derive the necessary data analysis and

interpretation (Paciepnik & Porter, 2017). With respect to this, I believe that the Ready Reckoner method is

a an effective tool which is highly simple due to its convenient evaluation of wide variety of food groups in

the form of average food values. Hence, for future use, I believe that we can apply the Ready Reckoner

method for nutrient analysis, since it financially feasible, requires less time in presenting the calculations

and is also easy to interpret by any individual lacking sufficient knowledge in nutrition. However, I still lack

sufficient confidence to use the Ready Reckoner method. This is because certain food groups such as Grains

Group 1 and 2, do not specify the intake of specific cereal based products such as spaghetti or instant

noodles. There is also no mention of beverages such as energy or coffee-based drinks, making it further

difficult to use. There is also no specification of the vegetables since this group comprises of a vast array of

items with varied weights and grouping them under ‘Moderate’ and ‘Low CHO’ is insufficient. Hence,

despite the simplicity, I believe that changes such as inclusion of additional food groups and specifications

under the grains and vegetables groups are required before applying full confidence in the Ready Reckoner

method.

Relating

Based on the occurrences of my previous experiences, I faced certain advantages as well as limitations in

my usage of various assessment methods such as 24 hour diet recall, weighed food record and the Ready

Reckoner Method. With respect to the weight food record, it is considered as one of the most

advantageous and comprehensive dietary assessment plan, as evident by the availability of the various

detailed food ingredients, the weight and the cooking procedures used by the subject (Martin et al., 2014).

However, while working with this assessment, I found it to be highly time consuming, and requires a lot of

communication between me and my clients, often resulting in difficulties in understanding. Due to high

effort and time required, I believe that this method may produce inaccurate results, since I have noticed

difficulties recalling accurate measurements by the clients. With respect, I believe that the usage of a 24-

hour recall is much easier, and participants are less likely to produce inaccurate information, due to

recording of previous day’s foods. Despite its efficiency with literate as well as illiterate subjects, I still

difficulty while interviewing, since careful questioning is required to elicit the requires responses. There is

also great difficulty if am required to undertake a 3 day recall, since participants find it very difficult to

remember. In my experience of Foodworks, I have found it to be highly accurate tool due to its large

database including various food items. However, I find it very time consuming where I am required to

explain clients in depth considering the results, since most of them lack sufficient nutritional knowledge.

With this respect, the Ready Reckoner method is highly effective in terms of convenience and simplicity, as I

can easily explain the results to the clients. However, I find it incomplete due to lack of specification of

several groups. Hence, based on relation to my experiences, I feel that instead of focusing on one method,

usage of multiple assessment methods would have been helpful for me in explaining the dietary needs of

the client.

10

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

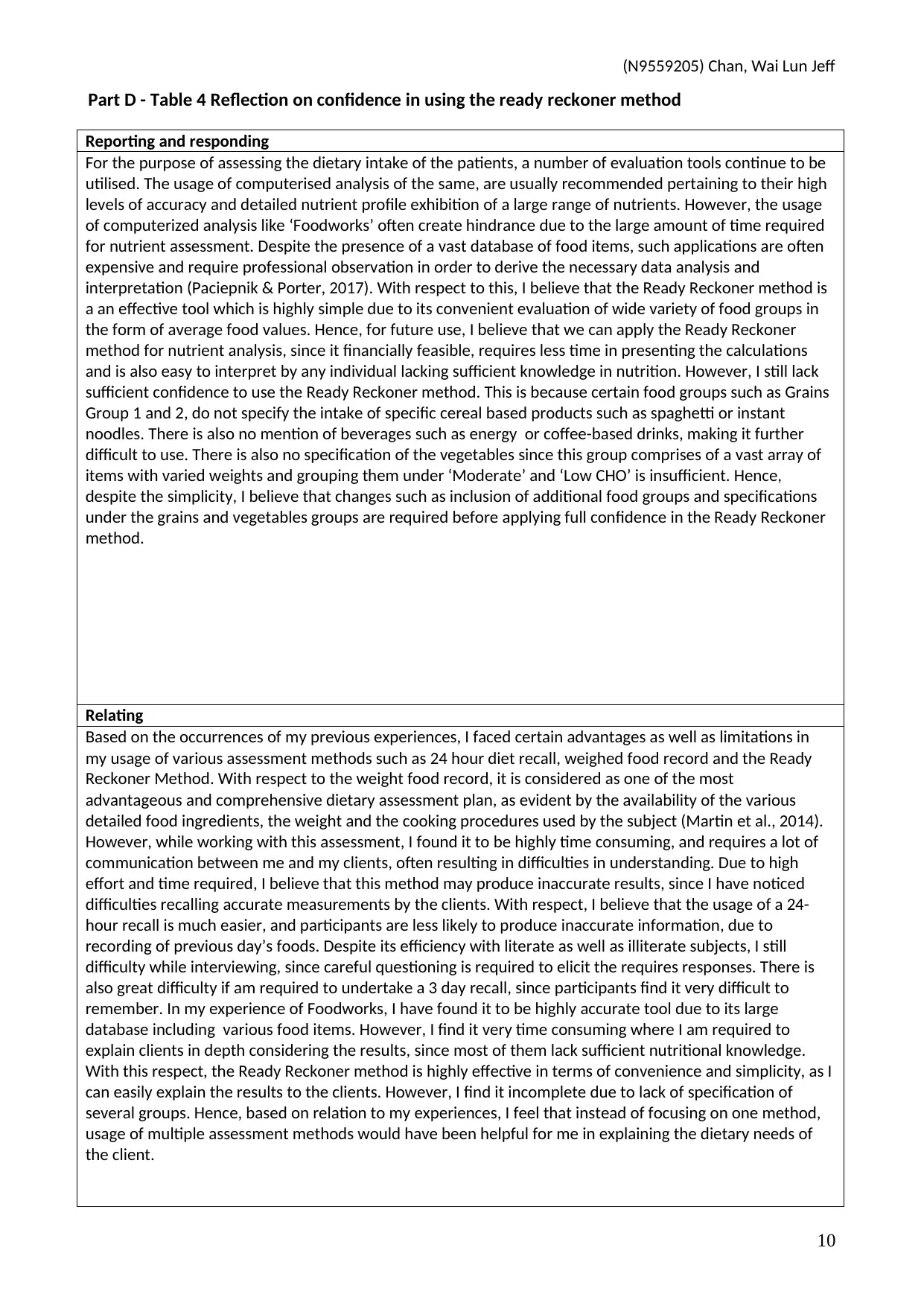

Reasoning

My confidence in the Ready Reckoner method, is due to its convenience, simplicity and reduced time

consumption, followed by its easy understanding by clients who lack sufficient nutritional knowledge.

Through the observation of these advantages, I believe that we can also observe the concerned limitations

of lack of specification of food groups. While this method provides quick and simple data which is easy to

comprehend, the presence of detailing in food groups such as grains, beverages and vegetables is

compromised , for the sake of convenience. Hence, if viewed from the dimensions of expert and

professional practice, the need of the hour is to not just rely on one quantitative dietary assessment

method like Ready Reckoner, but to use multiple quantitative as well as qualitative tools. Hence, an expert

would also interview the client and qualitatively observe the diet of the patient in detail to assess the diet

quality and consumption pattern of various food groups, along with also the usage of quantitative methods

such as Ready Reckoner (Paciepnik & Porter, 2016).

Reconstructing

If I am required to utilise the Ready Reckoner method for the purpose of formulating future dietary

recommendations, I believe that I may be required to undertake further communication with the client in

order to fully understand and as well as explain the results obtained from this method. The Ready Reckoner

method groups non-starchy vegetables as ‘low CHO’ and ‘moderate CHO’, which I believe is highly

unspecific since the group of vegetables consist of a vast array of micronutrients rather than simply limiting

them to containing carbohydrates (Paciepnik & Porter, 2016). Further, as observed, the Ready Reckoner

method does not take into account the various types of beverages which may be consumed by an

individual, including drinks or soups. Hence, I believe that during usage of Ready Reckoner method in the

future, one should discuss thoroughly with the client and obtain a detailed description of every food item

that he or she is consuming. Further, I believe that rather than relying solely on Ready Reckoner Method,

implementing a collaborative approach using various methods such a 24 hour diet recall and weighed food

diary, would further be beneficial in explaining the dietary changes a concerned patient will be required to

implement.

11

Reasoning

My confidence in the Ready Reckoner method, is due to its convenience, simplicity and reduced time

consumption, followed by its easy understanding by clients who lack sufficient nutritional knowledge.

Through the observation of these advantages, I believe that we can also observe the concerned limitations

of lack of specification of food groups. While this method provides quick and simple data which is easy to

comprehend, the presence of detailing in food groups such as grains, beverages and vegetables is

compromised , for the sake of convenience. Hence, if viewed from the dimensions of expert and

professional practice, the need of the hour is to not just rely on one quantitative dietary assessment

method like Ready Reckoner, but to use multiple quantitative as well as qualitative tools. Hence, an expert

would also interview the client and qualitatively observe the diet of the patient in detail to assess the diet

quality and consumption pattern of various food groups, along with also the usage of quantitative methods

such as Ready Reckoner (Paciepnik & Porter, 2016).

Reconstructing

If I am required to utilise the Ready Reckoner method for the purpose of formulating future dietary

recommendations, I believe that I may be required to undertake further communication with the client in

order to fully understand and as well as explain the results obtained from this method. The Ready Reckoner

method groups non-starchy vegetables as ‘low CHO’ and ‘moderate CHO’, which I believe is highly

unspecific since the group of vegetables consist of a vast array of micronutrients rather than simply limiting

them to containing carbohydrates (Paciepnik & Porter, 2016). Further, as observed, the Ready Reckoner

method does not take into account the various types of beverages which may be consumed by an

individual, including drinks or soups. Hence, I believe that during usage of Ready Reckoner method in the

future, one should discuss thoroughly with the client and obtain a detailed description of every food item

that he or she is consuming. Further, I believe that rather than relying solely on Ready Reckoner Method,

implementing a collaborative approach using various methods such a 24 hour diet recall and weighed food

diary, would further be beneficial in explaining the dietary changes a concerned patient will be required to

implement.

11

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

REFERENCES

Allman-Farinelli, M., Byron, A., Collins, C., Gifford, J., & Williams, P. (2014). Challenges and lessons from

systematic literature reviews for the Australian dietary guidelines. Australian journal of primary

health, 20(3), 236-240.

Aune, D., Navarro Rosenblatt, D. A., Chan, D. S., Vieira, A. R., Vieira, R., Greenwood, D. C., ... & Norat, T.

(2014). Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

cohort studies–. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 101(1), 87-117.

Banerjee, A., Larsen, R. S., Philpot, B. D., & Paulsen, O. (2016). Roles of presynaptic NMDA receptors in

neurotransmission and plasticity. Trends in neurosciences, 39(1), 26-39.

Baye, K., Guyot, J. P., & Mouquet-Rivier, C. (2017). The unresolved role of dietary fibers on mineral

absorption. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 57(5), 949-957.

Bosnea, L. A., Kopsahelis, N., Kokkali, V., Terpou, A., & Kanellaki, M. (2017). Production of a novel probiotic

yogurt by incorporation of L. casei enriched fresh apple pieces, dried raisins and wheat grains. Food

and bioproducts processing, 102, 62-71.

Buil-Cosiales, P., Toledo, E., Salas-Salvadó, J., Zazpe, I., Farràs, M., Basterra-Gortari, F. J., ... & Marti, A.

(2016). Association between dietary fibre intake and fruit, vegetable or whole-grain consumption and

the risk of CVD: results from the PREvencion con DIeta MEDiterranea (PREDIMED) trial. British Journal

of Nutrition, 116(3), 534-546.

Cashman, K. D. (2015). Vitamin D: dietary requirements and food fortification as a means of helping achieve

adequate vitamin D status. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 148, 19-26.

Chen, M., Li, Y., Sun, Q., Pan, A., Manson, J. E., Rexrode, K. M., ... & Hu, F. B. (2016). Dairy fat and risk of

cardiovascular disease in 3 cohorts of US adults–3. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 104(5),

1209-1217.

Christodoulides, S., Dimidi, E., Fragkos, K. C., Farmer, A. D., Whelan, K., & Scott, S. M. (2016). Systematic

review with meta analysis: effect of fibre supplementation on chronic idiopathic constipation in‐

adults. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 44(2), 103-116.

Dodevska, M., Šobajić, S., & Đorđević, B. (2015). Fibre and polyphenols of selected fruits, nuts and green

leafy vegetables used in Serbian diet. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society, 80(1), 21-33.

Ertan, H., Cassel, C., Verma, A., Poljak, A., Charlton, T., Aldrich-Wright, J., ... & Cavicchioli, R. (2015). A new

broad specificity alkaline metalloprotease from a Pseudomonas sp. isolated from refrigerated milk: role

of calcium in improving enzyme productivity. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 113, 1-8.

Grundy, M. M. L., Edwards, C. H., Mackie, A. R., Gidley, M. J., Butterworth, P. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2016). Re-

evaluation of the mechanisms of dietary fibre and implications for macronutrient bioaccessibility,

digestion and postprandial metabolism. British Journal of Nutrition, 116(5), 816-833.

Ihana-Sugiyama, N., Nagata, N., Yamamoto-Honda, R., Izawa, E., Kajio, H., Shimbo, T., ... & Noda, M. (2016).

Constipation, hard stools, fecal urgency, and incomplete evacuation, but not diarrhea is associated

with diabetes and its related factors. World journal of gastroenterology, 22(11), 3252.

Jaramillo, Á., Briones, L., Andrews, M., Arredondo, M., Olivares, M., Brito, A., & Pizarro, F. (2015). Effect of

phytic acid, tannic acid and pectin on fasting iron bioavailability both in the presence and absence of

calcium. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 30, 112-117.

12

REFERENCES

Allman-Farinelli, M., Byron, A., Collins, C., Gifford, J., & Williams, P. (2014). Challenges and lessons from

systematic literature reviews for the Australian dietary guidelines. Australian journal of primary

health, 20(3), 236-240.

Aune, D., Navarro Rosenblatt, D. A., Chan, D. S., Vieira, A. R., Vieira, R., Greenwood, D. C., ... & Norat, T.

(2014). Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

cohort studies–. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 101(1), 87-117.

Banerjee, A., Larsen, R. S., Philpot, B. D., & Paulsen, O. (2016). Roles of presynaptic NMDA receptors in

neurotransmission and plasticity. Trends in neurosciences, 39(1), 26-39.

Baye, K., Guyot, J. P., & Mouquet-Rivier, C. (2017). The unresolved role of dietary fibers on mineral

absorption. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 57(5), 949-957.

Bosnea, L. A., Kopsahelis, N., Kokkali, V., Terpou, A., & Kanellaki, M. (2017). Production of a novel probiotic

yogurt by incorporation of L. casei enriched fresh apple pieces, dried raisins and wheat grains. Food

and bioproducts processing, 102, 62-71.

Buil-Cosiales, P., Toledo, E., Salas-Salvadó, J., Zazpe, I., Farràs, M., Basterra-Gortari, F. J., ... & Marti, A.

(2016). Association between dietary fibre intake and fruit, vegetable or whole-grain consumption and

the risk of CVD: results from the PREvencion con DIeta MEDiterranea (PREDIMED) trial. British Journal

of Nutrition, 116(3), 534-546.

Cashman, K. D. (2015). Vitamin D: dietary requirements and food fortification as a means of helping achieve

adequate vitamin D status. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 148, 19-26.

Chen, M., Li, Y., Sun, Q., Pan, A., Manson, J. E., Rexrode, K. M., ... & Hu, F. B. (2016). Dairy fat and risk of

cardiovascular disease in 3 cohorts of US adults–3. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 104(5),

1209-1217.

Christodoulides, S., Dimidi, E., Fragkos, K. C., Farmer, A. D., Whelan, K., & Scott, S. M. (2016). Systematic

review with meta analysis: effect of fibre supplementation on chronic idiopathic constipation in‐

adults. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 44(2), 103-116.

Dodevska, M., Šobajić, S., & Đorđević, B. (2015). Fibre and polyphenols of selected fruits, nuts and green

leafy vegetables used in Serbian diet. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society, 80(1), 21-33.

Ertan, H., Cassel, C., Verma, A., Poljak, A., Charlton, T., Aldrich-Wright, J., ... & Cavicchioli, R. (2015). A new

broad specificity alkaline metalloprotease from a Pseudomonas sp. isolated from refrigerated milk: role

of calcium in improving enzyme productivity. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 113, 1-8.

Grundy, M. M. L., Edwards, C. H., Mackie, A. R., Gidley, M. J., Butterworth, P. J., & Ellis, P. R. (2016). Re-

evaluation of the mechanisms of dietary fibre and implications for macronutrient bioaccessibility,

digestion and postprandial metabolism. British Journal of Nutrition, 116(5), 816-833.

Ihana-Sugiyama, N., Nagata, N., Yamamoto-Honda, R., Izawa, E., Kajio, H., Shimbo, T., ... & Noda, M. (2016).

Constipation, hard stools, fecal urgency, and incomplete evacuation, but not diarrhea is associated

with diabetes and its related factors. World journal of gastroenterology, 22(11), 3252.

Jaramillo, Á., Briones, L., Andrews, M., Arredondo, M., Olivares, M., Brito, A., & Pizarro, F. (2015). Effect of

phytic acid, tannic acid and pectin on fasting iron bioavailability both in the presence and absence of

calcium. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 30, 112-117.

12

(N9559205) Chan, Wai Lun Jeff

Kapil, R. (2017). Bioavailability & absorption of Iron and Anemia. Indian Journal of Community Health, 29(4),

453-457.

Keast, D. R., Hill Gallant, K. M., Albertson, A. M., Gugger, C. K., & Holschuh, N. M. (2015). Associations

between yogurt, dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and obesity among US children aged 8–18 years:

NHANES, 2005–2008. Nutrients, 7(3), 1577-1593.

Kovacic, K., Sood, M. R., Mugie, S., Di Lorenzo, C., Nurko, S., Heinz, N., ... & Silverman, A. H. (2015). A

multicenter study on childhood constipation and fecal incontinence: effects on quality of life. The

Journal of Pediatrics, 166(6), 1482-1487.

Kyle, T., Greaves, I., Beynon, A., Whittaker, V., Brewer, M., & Smith, J. (2018). Ionised calcium levels in major

trauma patients who received blood en route to a military medical treatment facility. Emerg Med

J, 35(3), 176-179.

Lane, D. J., & Richardson, D. R. (2014). The active role of vitamin C in mammalian iron metabolism: much

more than just enhanced iron absorption!. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 75, 69-83.

Leonard, A. J., Chalmers, K. A., Collins, C. E., & Patterson, A. J. (2014). The effect of nutrition knowledge and

dietary iron intake on iron status in young women. Appetite, 81, 225-231.

Lima, G. A. C., Lima, P. D. A., Barros, M. D. G. C. R., Vardiero, L. P., Melo, E. F. D., Paranhos-Neto, F. D. P., ...

& Farias, M. L. F. D. (2016). Calcium intake: good for the bones but bad for the heart? An analysis of

clinical studies. Archives of endocrinology and metabolism, 60(3), 252-263.

Lopez, A., Cacoub, P., Macdougall, I. C., & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. (2016). Iron deficiency anaemia. The

Lancet, 387(10021), 907-916.

Martin, C. K., Nicklas, T., Gunturk, B., Correa, J. B., Allen, H. R., & Champagne, C. (2014). Measuring food

intake with digital photography. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 27, 72-81.

Mihafu, F., Laswai, H. S., Gichuhi, P., Mwanyika, S., & Bovell-Benjamin, A. C. (2017). Influence of soaking and

germination on the iron, phytate and phenolic contents of maize used for complementary feeding in

rural Tanzania. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, 6(2), 111-117.

Mishra, G. D., Schoenaker, D. A., Mihrshahi, S., & Dobson, A. J. (2015). How do women's diets compare with

the new Australian dietary guidelines?. Public health nutrition, 18(2), 218-225.

Nwachukwu, I. D., Devassy, J. G., Aluko, R. E., & Jones, P. J. (2015). Cholesterol-lowering properties of oat β-

glucan and the promotion of cardiovascular health: did Health Canada make the right call?. Applied

Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 40(6), 535-542.

Oliveira, T. Í. S., Rosa, M. F., Cavalcante, F. L., Pereira, P. H. F., Moates, G. K., Wellner, N., ... & Azeredo, H.

M. (2016). Optimization of pectin extraction from banana peels with citric acid by using response

surface methodology. Food chemistry, 198, 113-118.

Paciepnik, J., & Porter, J. (2017). Comparing Computerised Dietary Analysis with a Ready Reckoner in a Real

World Setting: Is Technology an Improvement?. Nutrients, 9(2), 99.

Prentice, A. M., Mendoza, Y. A., Pereira, D., Cerami, C., Wegmuller, R., Constable, A., & Spieldenner, J.

(2016). Dietary strategies for improving iron status: balancing safety and efficacy. Nutrition

reviews, 75(1), 49-60.

Rebello, C. J., Greenway, F. L., & Finley, J. W. (2014). Whole grains and pulses: A comparison of the

nutritional and health benefits. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 62(29), 7029-7049.

Scheers, N., Rossander-Hulthen, L., Torsdottir, I., & Sandberg, A. S. (2016). Increased iron bioavailability

from lactic-fermented vegetables is likely an effect of promoting the formation of ferric iron (Fe

3+). European journal of nutrition, 55(1), 373-382.

Schloermann, W., & Glei, M. (2017). Potential health benefits of β-glucan from barley and oat. Ernahrungs

Umschau, 64(10), 145-149.

13

Kapil, R. (2017). Bioavailability & absorption of Iron and Anemia. Indian Journal of Community Health, 29(4),

453-457.

Keast, D. R., Hill Gallant, K. M., Albertson, A. M., Gugger, C. K., & Holschuh, N. M. (2015). Associations

between yogurt, dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and obesity among US children aged 8–18 years:

NHANES, 2005–2008. Nutrients, 7(3), 1577-1593.

Kovacic, K., Sood, M. R., Mugie, S., Di Lorenzo, C., Nurko, S., Heinz, N., ... & Silverman, A. H. (2015). A

multicenter study on childhood constipation and fecal incontinence: effects on quality of life. The

Journal of Pediatrics, 166(6), 1482-1487.

Kyle, T., Greaves, I., Beynon, A., Whittaker, V., Brewer, M., & Smith, J. (2018). Ionised calcium levels in major

trauma patients who received blood en route to a military medical treatment facility. Emerg Med

J, 35(3), 176-179.

Lane, D. J., & Richardson, D. R. (2014). The active role of vitamin C in mammalian iron metabolism: much

more than just enhanced iron absorption!. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 75, 69-83.

Leonard, A. J., Chalmers, K. A., Collins, C. E., & Patterson, A. J. (2014). The effect of nutrition knowledge and

dietary iron intake on iron status in young women. Appetite, 81, 225-231.

Lima, G. A. C., Lima, P. D. A., Barros, M. D. G. C. R., Vardiero, L. P., Melo, E. F. D., Paranhos-Neto, F. D. P., ...

& Farias, M. L. F. D. (2016). Calcium intake: good for the bones but bad for the heart? An analysis of

clinical studies. Archives of endocrinology and metabolism, 60(3), 252-263.

Lopez, A., Cacoub, P., Macdougall, I. C., & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. (2016). Iron deficiency anaemia. The