Investigating Online Mathematics Teaching and Learning in Saudi Arabia

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|116

|33613

|418

Project

AI Summary

This project examines the impact of online mathematics teaching and learning in Saudi Arabian primary schools, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and Saudi Vision 2030. The research employs a mixed-methods approach, including questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and non-participant observations, to gather data from both teachers and students. The study explores the challenges and opportunities presented by online education, including the use of digital platforms and synchronous/asynchronous learning methods. It investigates the influence of teacher characteristics such as gender and experience on the adoption of online tools, and assesses the impact of the curriculum on student performance. The findings aim to inform policy decisions, enhance mathematics education, and contribute to the broader understanding of online learning environments. The project also delves into the validity, reliability, and ethical considerations of the research methodology. The project includes an introduction, methodology, and literature review chapter.

1.1 Background....................................................................................................................1

1.1.1 Education in Saudi Vision 2030.............................................................................................1

1.1.2 The Educational Impact of COVID-19: The Case of Primary Mathematics Teaching

and Learning in Saudi Arabia........................................................................................................1

1.1.5 Online Teaching and Learning..............................................................................................5

1.3 Significance of The Study...................................................................................................6

1.4 Overview of The Study........................................................................................................7

3.1 Introduction........................................................................................................................3

3.2 Adopted research philosophy..............................................................................................3

3.2.1 Ontology..................................................................................................................................4

3.2.2 Epistemology...........................................................................................................................5

3.2.3 Pragmatism.............................................................................................................................6

3.3 Research design: Mixed methods.......................................................................................7

3.4 Sample sizes and sampling strategies...............................................................................10

3.4.1 Sample sizes...........................................................................................................................10

3.4.1.1 Quantitative stage..............................................................................................................................10

3.4.1.2 Qualitative stage................................................................................................................................12

3.4.2 Sampling strategies...............................................................................................................13

3.4.2.1 Quantitative stage..............................................................................................................................14

3.4.2.2 Qualitative stage................................................................................................................................15

3.5.1 Questionnaire .......................................................................................................................16

3.5.2 Semi-structure interview .....................................................................................................19

3.5.3 Non-participant observation................................................................................................21

3.6 Pilot study..........................................................................................................................23

3.7 Data analysis.....................................................................................................................23

3.7.1 Quantitative data analysis....................................................................................................23

3.7.2 Qualitative data analysis .....................................................................................................24

3.8 Validity and reliability.......................................................................................................26

3.8.1 Validity .................................................................................................................................26

3.8.2 Reliability..............................................................................................................................28

3.9 Ethical considerations......................................................................................................29

3.10 Summary.........................................................................................................................31

References...............................................................................................................................32

Introduction chapter: about 2000 words

1.1.1 Education in Saudi Vision 2030.............................................................................................1

1.1.2 The Educational Impact of COVID-19: The Case of Primary Mathematics Teaching

and Learning in Saudi Arabia........................................................................................................1

1.1.5 Online Teaching and Learning..............................................................................................5

1.3 Significance of The Study...................................................................................................6

1.4 Overview of The Study........................................................................................................7

3.1 Introduction........................................................................................................................3

3.2 Adopted research philosophy..............................................................................................3

3.2.1 Ontology..................................................................................................................................4

3.2.2 Epistemology...........................................................................................................................5

3.2.3 Pragmatism.............................................................................................................................6

3.3 Research design: Mixed methods.......................................................................................7

3.4 Sample sizes and sampling strategies...............................................................................10

3.4.1 Sample sizes...........................................................................................................................10

3.4.1.1 Quantitative stage..............................................................................................................................10

3.4.1.2 Qualitative stage................................................................................................................................12

3.4.2 Sampling strategies...............................................................................................................13

3.4.2.1 Quantitative stage..............................................................................................................................14

3.4.2.2 Qualitative stage................................................................................................................................15

3.5.1 Questionnaire .......................................................................................................................16

3.5.2 Semi-structure interview .....................................................................................................19

3.5.3 Non-participant observation................................................................................................21

3.6 Pilot study..........................................................................................................................23

3.7 Data analysis.....................................................................................................................23

3.7.1 Quantitative data analysis....................................................................................................23

3.7.2 Qualitative data analysis .....................................................................................................24

3.8 Validity and reliability.......................................................................................................26

3.8.1 Validity .................................................................................................................................26

3.8.2 Reliability..............................................................................................................................28

3.9 Ethical considerations......................................................................................................29

3.10 Summary.........................................................................................................................31

References...............................................................................................................................32

Introduction chapter: about 2000 words

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Literature review chapter: 3000 – 5000 words

Methodology chapter: 8000- 10000 words

Introduction Chapter

Methodology chapter: 8000- 10000 words

Introduction Chapter

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Education in Saudi Vision 2030

The "Saudi Arabia Vision 2030" aims to develop education in several aspects (Saudi Vision,

2030, 2016). One of the main objectives of this national transformation program is to improve the

educational system in the country, such as improving the basis of learning, updating assessments and

curricula, and ensuring that education is not affected by any emergency, such as what happened with

COVID-19 (OCED, 2020). Although education was greatly affected by the global pandemic, the

speed of response by the Ministry of Education and the support of Vision(Education in Saudi Vision,

2030) alleviated the suffering of students and parents by providing an educational platform that

contributed to this crisis significantly (Saudi Ministry of Education, 2021). According to the Ministry

of Education of Saudi Arabia (2017), one of the goals of the Vision is to build the current curriculum

around the stringent requirements of character development, skills, numeracy, and literacy. To ensure

that educational achievements align with market demands, educational institutions need to work

closely with the corporate sector.Saudi Arabia has achieved universal access to education for a large

and geographically dispersed school-age population. With its impressive gains in enrolment, however,

Saudi Arabia has stretched the capacity of educators and administrators to deliver and assure high-

quality learning. The advances in participation will now need to be matched with equivalent progress

in student learning and skills if the Kingdom is to achieve the ambitious development goals outlined

in Vision 2030.

1.1.2 The Educational Impact of COVID-19: The Case of Primary Mathematics Teaching and

Learning in Saudi Arabia

1

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Education in Saudi Vision 2030

The "Saudi Arabia Vision 2030" aims to develop education in several aspects (Saudi Vision,

2030, 2016). One of the main objectives of this national transformation program is to improve the

educational system in the country, such as improving the basis of learning, updating assessments and

curricula, and ensuring that education is not affected by any emergency, such as what happened with

COVID-19 (OCED, 2020). Although education was greatly affected by the global pandemic, the

speed of response by the Ministry of Education and the support of Vision(Education in Saudi Vision,

2030) alleviated the suffering of students and parents by providing an educational platform that

contributed to this crisis significantly (Saudi Ministry of Education, 2021). According to the Ministry

of Education of Saudi Arabia (2017), one of the goals of the Vision is to build the current curriculum

around the stringent requirements of character development, skills, numeracy, and literacy. To ensure

that educational achievements align with market demands, educational institutions need to work

closely with the corporate sector.Saudi Arabia has achieved universal access to education for a large

and geographically dispersed school-age population. With its impressive gains in enrolment, however,

Saudi Arabia has stretched the capacity of educators and administrators to deliver and assure high-

quality learning. The advances in participation will now need to be matched with equivalent progress

in student learning and skills if the Kingdom is to achieve the ambitious development goals outlined

in Vision 2030.

1.1.2 The Educational Impact of COVID-19: The Case of Primary Mathematics Teaching and

Learning in Saudi Arabia

1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The effect of COVID-19 on the educational sector resulted in the closure of schools

worldwide (Oraif&Elyas, 2021). According to Rahman et al. (2019), more than one billion students in

schools and universities were affected by school closures. Moreover, the structure of learning and

schooling has been changed by the closing of schools. (Tarkar, 2020). Hence, education has changed

significantly with an increasing shift in technology usage and online teaching and learning methods

(Oraif&Elyas, 2021).

In Saudi Arabia, although online learning was implemented in the country before the

pandemic, it was simple and in its infancy. The educational system had to be changed significantly to

allow students to learn and attend schools remotely (Oraif&Elyas, 2021). For example, before the start

of the 2020 academic year, Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Education launched a new digital platform

called Madrasati (translated as "My School"). This new platform was built to tackle the impact of the

pandemic on education for both staff and students in the country (Alshehri et al., 2020). The digital

platform enables students and teachers to engage in visual communication, conduct classes online,

and conduct assessments and examinations. Alongside this digital platform, the Ministry also

introduced more than twenty TV channels for each educational level, ranging from primary to high

schools (Oraif&Elyas, 2021).

1.1.4 Saudi Arabia's Primary Mathematics Curriculum and Achievement

Saudi Vision 2030 emphasizes mathematics in elementary schools, where students' identities

are formed, and their minds are exposed to a wealth of previously unknown material. This paves the

way for knowledge and community engagement. This is due to the government's emphasis on

strengthening Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education and putting

these topics at the forefront of educational advancement (Alhareth& Al Dighrir, 2014). According to

(Alhareth& Al Dighrir ,2014), the Saudi primary mathematics curriculum is built on real-life

applications that integrate science and mathematics. This might help students do better in math classes

2

worldwide (Oraif&Elyas, 2021). According to Rahman et al. (2019), more than one billion students in

schools and universities were affected by school closures. Moreover, the structure of learning and

schooling has been changed by the closing of schools. (Tarkar, 2020). Hence, education has changed

significantly with an increasing shift in technology usage and online teaching and learning methods

(Oraif&Elyas, 2021).

In Saudi Arabia, although online learning was implemented in the country before the

pandemic, it was simple and in its infancy. The educational system had to be changed significantly to

allow students to learn and attend schools remotely (Oraif&Elyas, 2021). For example, before the start

of the 2020 academic year, Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Education launched a new digital platform

called Madrasati (translated as "My School"). This new platform was built to tackle the impact of the

pandemic on education for both staff and students in the country (Alshehri et al., 2020). The digital

platform enables students and teachers to engage in visual communication, conduct classes online,

and conduct assessments and examinations. Alongside this digital platform, the Ministry also

introduced more than twenty TV channels for each educational level, ranging from primary to high

schools (Oraif&Elyas, 2021).

1.1.4 Saudi Arabia's Primary Mathematics Curriculum and Achievement

Saudi Vision 2030 emphasizes mathematics in elementary schools, where students' identities

are formed, and their minds are exposed to a wealth of previously unknown material. This paves the

way for knowledge and community engagement. This is due to the government's emphasis on

strengthening Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education and putting

these topics at the forefront of educational advancement (Alhareth& Al Dighrir, 2014). According to

(Alhareth& Al Dighrir ,2014), the Saudi primary mathematics curriculum is built on real-life

applications that integrate science and mathematics. This might help students do better in math classes

2

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

and give them a better connection and knowledge of the curriculum's basic concepts (Alghamdi,

2017).

These best curricula are designed to promote balanced understanding and vertical integration

across disciplines at all levels of education (Alafaleq& Fan, 2014). This promotes the development of

higher cognitive and comprehensive mathematics abilities at all levels of education (Alshehri& Ali,

2016). The design of these mathematical subjects in schools is based on a variety of learning

objectives, including 1) examining concepts and developing cognitive skills, 2) developing

comprehensive mathematical skills and techniques, and 3) enabling students to use logical reasoning

to overcome challenges and difficulties in life (Alshehri& Ali, 2016).

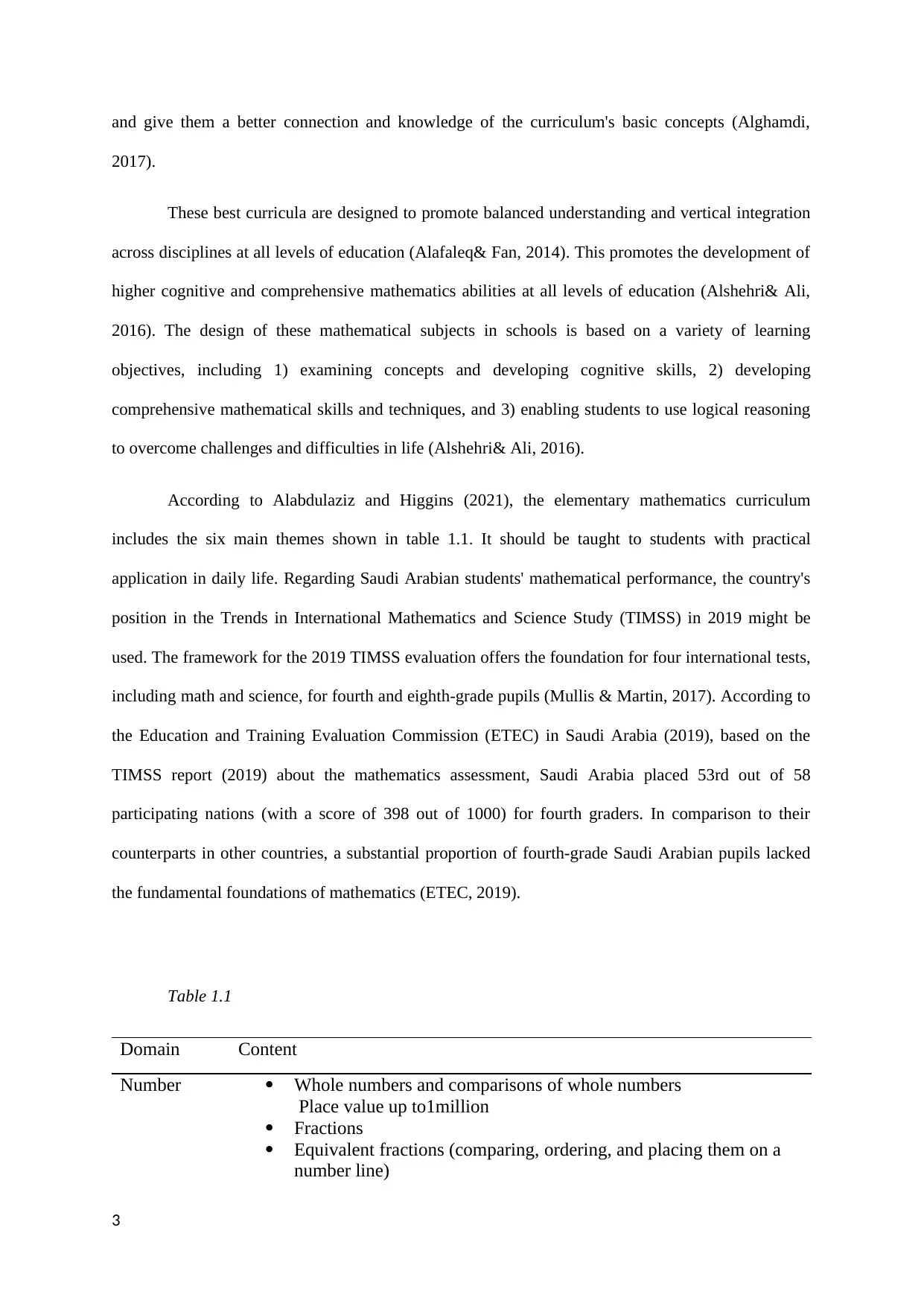

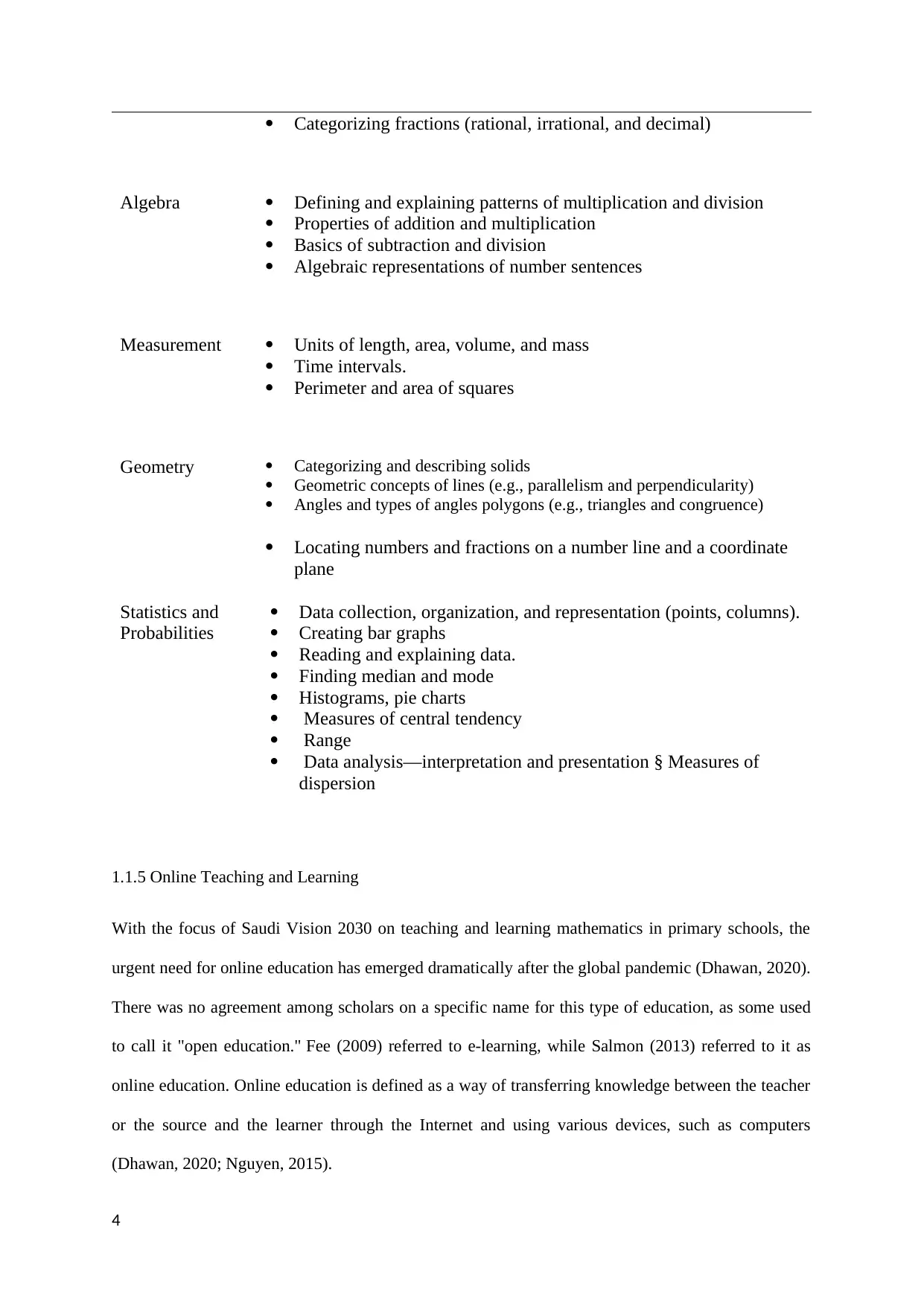

According to Alabdulaziz and Higgins (2021), the elementary mathematics curriculum

includes the six main themes shown in table 1.1. It should be taught to students with practical

application in daily life. Regarding Saudi Arabian students' mathematical performance, the country's

position in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in 2019 might be

used. The framework for the 2019 TIMSS evaluation offers the foundation for four international tests,

including math and science, for fourth and eighth-grade pupils (Mullis & Martin, 2017). According to

the Education and Training Evaluation Commission (ETEC) in Saudi Arabia (2019), based on the

TIMSS report (2019) about the mathematics assessment, Saudi Arabia placed 53rd out of 58

participating nations (with a score of 398 out of 1000) for fourth graders. In comparison to their

counterparts in other countries, a substantial proportion of fourth-grade Saudi Arabian pupils lacked

the fundamental foundations of mathematics (ETEC, 2019).

Table 1.1

Domain Content

Number Whole numbers and comparisons of whole numbers

Place value up to1million

Fractions

Equivalent fractions (comparing, ordering, and placing them on a

number line)

3

2017).

These best curricula are designed to promote balanced understanding and vertical integration

across disciplines at all levels of education (Alafaleq& Fan, 2014). This promotes the development of

higher cognitive and comprehensive mathematics abilities at all levels of education (Alshehri& Ali,

2016). The design of these mathematical subjects in schools is based on a variety of learning

objectives, including 1) examining concepts and developing cognitive skills, 2) developing

comprehensive mathematical skills and techniques, and 3) enabling students to use logical reasoning

to overcome challenges and difficulties in life (Alshehri& Ali, 2016).

According to Alabdulaziz and Higgins (2021), the elementary mathematics curriculum

includes the six main themes shown in table 1.1. It should be taught to students with practical

application in daily life. Regarding Saudi Arabian students' mathematical performance, the country's

position in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in 2019 might be

used. The framework for the 2019 TIMSS evaluation offers the foundation for four international tests,

including math and science, for fourth and eighth-grade pupils (Mullis & Martin, 2017). According to

the Education and Training Evaluation Commission (ETEC) in Saudi Arabia (2019), based on the

TIMSS report (2019) about the mathematics assessment, Saudi Arabia placed 53rd out of 58

participating nations (with a score of 398 out of 1000) for fourth graders. In comparison to their

counterparts in other countries, a substantial proportion of fourth-grade Saudi Arabian pupils lacked

the fundamental foundations of mathematics (ETEC, 2019).

Table 1.1

Domain Content

Number Whole numbers and comparisons of whole numbers

Place value up to1million

Fractions

Equivalent fractions (comparing, ordering, and placing them on a

number line)

3

Categorizing fractions (rational, irrational, and decimal)

Algebra Defining and explaining patterns of multiplication and division

Properties of addition and multiplication

Basics of subtraction and division

Algebraic representations of number sentences

Measurement Units of length, area, volume, and mass

Time intervals.

Perimeter and area of squares

Geometry Categorizing and describing solids

Geometric concepts of lines (e.g., parallelism and perpendicularity)

Angles and types of angles polygons (e.g., triangles and congruence)

Locating numbers and fractions on a number line and a coordinate

plane

Statistics and

Probabilities

Data collection, organization, and representation (points, columns).

Creating bar graphs

Reading and explaining data.

Finding median and mode

Histograms, pie charts

Measures of central tendency

Range

Data analysis—interpretation and presentation § Measures of

dispersion

1.1.5 Online Teaching and Learning

With the focus of Saudi Vision 2030 on teaching and learning mathematics in primary schools, the

urgent need for online education has emerged dramatically after the global pandemic (Dhawan, 2020).

There was no agreement among scholars on a specific name for this type of education, as some used

to call it "open education." Fee (2009) referred to e-learning, while Salmon (2013) referred to it as

online education. Online education is defined as a way of transferring knowledge between the teacher

or the source and the learner through the Internet and using various devices, such as computers

(Dhawan, 2020; Nguyen, 2015).

4

Algebra Defining and explaining patterns of multiplication and division

Properties of addition and multiplication

Basics of subtraction and division

Algebraic representations of number sentences

Measurement Units of length, area, volume, and mass

Time intervals.

Perimeter and area of squares

Geometry Categorizing and describing solids

Geometric concepts of lines (e.g., parallelism and perpendicularity)

Angles and types of angles polygons (e.g., triangles and congruence)

Locating numbers and fractions on a number line and a coordinate

plane

Statistics and

Probabilities

Data collection, organization, and representation (points, columns).

Creating bar graphs

Reading and explaining data.

Finding median and mode

Histograms, pie charts

Measures of central tendency

Range

Data analysis—interpretation and presentation § Measures of

dispersion

1.1.5 Online Teaching and Learning

With the focus of Saudi Vision 2030 on teaching and learning mathematics in primary schools, the

urgent need for online education has emerged dramatically after the global pandemic (Dhawan, 2020).

There was no agreement among scholars on a specific name for this type of education, as some used

to call it "open education." Fee (2009) referred to e-learning, while Salmon (2013) referred to it as

online education. Online education is defined as a way of transferring knowledge between the teacher

or the source and the learner through the Internet and using various devices, such as computers

(Dhawan, 2020; Nguyen, 2015).

4

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Online education is divided into two types, namely, synchronous and non-

synchronous education. Synchronous education refers to teaching and learning techniques in

which the learner(s) and instructor(s) are in the exact location at the same time to facilitate

learning (Oztok et al., 2013). Non-synchronous education's core idea is that learning may

occur multiple times and places depending on the learner (Yamagata-Lynch, 2014). When

there is a time constraint or a desire for flexibility in learning, this method is used (Yamagata-

Lynch, 2014). Learners have the option of downloading or attending their online session

whenever they wish. This form of learning allows for social interaction using a message

board, which is an example of an asynchronous tool, and the learner can learn mathematics at

their leisure. (Yamagata-Lynch, 2014).

1.2 Aims of The Study

The purpose of this study is to query the perceptions of Saudi primary school teachers and

students about online mathematics teaching and learning during the global pandemic. The goal of this

study is to find out what teachers and students in primary schools in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

have to deal with when they use online tools to teach and learn math.In addition, to see if there is an

effect of gender and years of teaching experience on using online tools in elementary school

mathematics teaching, It focuses on analysing the impact of teacher characteristics such as gender and

years of teaching experience. Albalaw (2017) It is believed that male teachers are more comfortable

with computer-enabled online media sources because it has been determined that male teachers with

at least ten years of teaching experience in the education environment in Saudi Arabia are more

comfortable using online educational tools and platforms than females in general (Bluegrass, 2017).

Furthermore, Wiseman et al. This results in educational benefits for teachers in a gender-segregated

society (Weizmann et al., 2018). Furthermore, Prendergast et al. (2018) argued that with the support

of the theory of planned behavior, parameters such as attitude and behaviour to adopt an entity, social

5

synchronous education. Synchronous education refers to teaching and learning techniques in

which the learner(s) and instructor(s) are in the exact location at the same time to facilitate

learning (Oztok et al., 2013). Non-synchronous education's core idea is that learning may

occur multiple times and places depending on the learner (Yamagata-Lynch, 2014). When

there is a time constraint or a desire for flexibility in learning, this method is used (Yamagata-

Lynch, 2014). Learners have the option of downloading or attending their online session

whenever they wish. This form of learning allows for social interaction using a message

board, which is an example of an asynchronous tool, and the learner can learn mathematics at

their leisure. (Yamagata-Lynch, 2014).

1.2 Aims of The Study

The purpose of this study is to query the perceptions of Saudi primary school teachers and

students about online mathematics teaching and learning during the global pandemic. The goal of this

study is to find out what teachers and students in primary schools in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

have to deal with when they use online tools to teach and learn math.In addition, to see if there is an

effect of gender and years of teaching experience on using online tools in elementary school

mathematics teaching, It focuses on analysing the impact of teacher characteristics such as gender and

years of teaching experience. Albalaw (2017) It is believed that male teachers are more comfortable

with computer-enabled online media sources because it has been determined that male teachers with

at least ten years of teaching experience in the education environment in Saudi Arabia are more

comfortable using online educational tools and platforms than females in general (Bluegrass, 2017).

Furthermore, Wiseman et al. This results in educational benefits for teachers in a gender-segregated

society (Weizmann et al., 2018). Furthermore, Prendergast et al. (2018) argued that with the support

of the theory of planned behavior, parameters such as attitude and behaviour to adopt an entity, social

5

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

factors, and behavioural control of processes influence a specific segment of users in support of a

particular educational reform (Prendergast et al., 2018). The purpose of this question is to find out if

there is an effect of gender and years of teaching experience on the use of online tools in elementary

school mathematics teaching.

1.3 Significance of The Study

The results of this research will enable policymakers in Saudi Arabia, and more specifically, the Saudi

Minister of Education, to revise their policies on primary mathematics curriculum design to enhance

students' mathematics learning and knowledge. Since the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has

led to the emergence of significant challenges in the education sector, and according to the Saudi

Minister of Education (2021),

And he added:

He is proud of the development of the education system in the Kingdom of Saudi

Arabia under the supervision of the Ministry of Education, expecting that distance

education will be a project for the future and will continue to benefit from it and

invest in it in all circumstances during the pandemic and after the pandemic, and this

is a quantum leap for the digitization of education at the level of the Kingdom

(Ministry of Education, 2021, para 8).

Hence, this study is vital and timely because it will provide a comprehensive understanding

of online learning tools and teaching, particularly about vital curricular subjects such as

mathematics.

Furthermore, this research aims to contribute to the field of educational research that focuses

on online learning and teaching. Using a mixed-method approach and collecting quantitative and

qualitative data via questionnaires, interviews, and observations leads to a more in-depth

understanding of the results as well as an increase in the validity of the study's results by using two or

more approaches to ensure their accuracy and reliability about the study under investigation. Finally,

6

particular educational reform (Prendergast et al., 2018). The purpose of this question is to find out if

there is an effect of gender and years of teaching experience on the use of online tools in elementary

school mathematics teaching.

1.3 Significance of The Study

The results of this research will enable policymakers in Saudi Arabia, and more specifically, the Saudi

Minister of Education, to revise their policies on primary mathematics curriculum design to enhance

students' mathematics learning and knowledge. Since the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has

led to the emergence of significant challenges in the education sector, and according to the Saudi

Minister of Education (2021),

And he added:

He is proud of the development of the education system in the Kingdom of Saudi

Arabia under the supervision of the Ministry of Education, expecting that distance

education will be a project for the future and will continue to benefit from it and

invest in it in all circumstances during the pandemic and after the pandemic, and this

is a quantum leap for the digitization of education at the level of the Kingdom

(Ministry of Education, 2021, para 8).

Hence, this study is vital and timely because it will provide a comprehensive understanding

of online learning tools and teaching, particularly about vital curricular subjects such as

mathematics.

Furthermore, this research aims to contribute to the field of educational research that focuses

on online learning and teaching. Using a mixed-method approach and collecting quantitative and

qualitative data via questionnaires, interviews, and observations leads to a more in-depth

understanding of the results as well as an increase in the validity of the study's results by using two or

more approaches to ensure their accuracy and reliability about the study under investigation. Finally,

6

the findings will contribute to previous research on the role of teachers' self-efficacy in using online

teaching tools and techniques to teach primary mathematics.

1.4 Overview of The Study

This Confirmation of Registration (CoR) report is broken down into three sections. This chapter,

Chapter 1 (Introduction), has provided an overview of the topic under investigation. More

specifically, the chapter has discussed the effect of the current pandemic on the educational sector in

general with a special reference to on-line mathematics learning in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, the

chapter has explained the Saudi 2030 vision regarding education in the country and has discussed

Saudi Arabia’s mathematical curriculum design and student evaluation as well as Saudi students’

students’ performance in TIMSS 2019. In addition. Finally, the chapter has explained the aims and the

significance of this research study.

Chapter 2 (Literature Review) will begin with a discussion on the definition of synchronous and

non-synchronous education and then will move on to the next section which is concerned with

teaching and learning primary mathematics. Moreover, it will present some of the theories used in

mathematics teaching and learning. It also will cover the underpinning theories of this study, which

are Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK), Moore's theory, and self-efficacy

theory. Then, it will present some barriers and enabling factors that have been presented in previous

studies related to on-line mathematics teaching and learning. Finally, the impact of the characteristics

of teachers, such as genders and years of teaching experience impact of teachers’ characteristics on

their self-efficacy is discussed.

The third chapter (Methodology) will explain the chosen research methodology for this

research. The chapter will start by explaining the chosen research philosophy and research design with

justification. The sample size and sampling strategy will also be explained, and the intended data

collection methods will be discussed. Finally, the chapter will discuss the analysis of the collected

7

teaching tools and techniques to teach primary mathematics.

1.4 Overview of The Study

This Confirmation of Registration (CoR) report is broken down into three sections. This chapter,

Chapter 1 (Introduction), has provided an overview of the topic under investigation. More

specifically, the chapter has discussed the effect of the current pandemic on the educational sector in

general with a special reference to on-line mathematics learning in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, the

chapter has explained the Saudi 2030 vision regarding education in the country and has discussed

Saudi Arabia’s mathematical curriculum design and student evaluation as well as Saudi students’

students’ performance in TIMSS 2019. In addition. Finally, the chapter has explained the aims and the

significance of this research study.

Chapter 2 (Literature Review) will begin with a discussion on the definition of synchronous and

non-synchronous education and then will move on to the next section which is concerned with

teaching and learning primary mathematics. Moreover, it will present some of the theories used in

mathematics teaching and learning. It also will cover the underpinning theories of this study, which

are Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK), Moore's theory, and self-efficacy

theory. Then, it will present some barriers and enabling factors that have been presented in previous

studies related to on-line mathematics teaching and learning. Finally, the impact of the characteristics

of teachers, such as genders and years of teaching experience impact of teachers’ characteristics on

their self-efficacy is discussed.

The third chapter (Methodology) will explain the chosen research methodology for this

research. The chapter will start by explaining the chosen research philosophy and research design with

justification. The sample size and sampling strategy will also be explained, and the intended data

collection methods will be discussed. Finally, the chapter will discuss the analysis of the collected

7

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

data, and the reliability and validity of this research. Ethical considerations have also been brought

forward.

8

forward.

8

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Literature Review

Chapter

1

Chapter

1

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This chapter aims to present a review of literature on perceptions of school teachers and

children in Saudi Arabia regarding online mathematics teaching and learning during the global

pandemic (2020–present). Specifically, the concept of online teaching and learning that includes

synchronous and asynchronous learning will be discussed. The study’s underpinning theories, namely

the Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework and the Self-efficacy

theory will be discussed. Finally, potential barriers and enablers concerning online mathematics

teaching and learning will be discussed.

2.2 online teaching and learning

2.2.1 Definitions

As denoted by Singh and Thurman, (2019), Online learning is defined as the education which takes

place over the internet. It is also defined as e – learning which is described in other forms.

As per Fitton, Finnegan and Proulx (2020), online learning is the learning where the students and are

learning through virtual environment. Online learning helps the student to learn and enhance their

knowledge and understanding in the form as to how effectively they are undertaking various measures

of learning.

According to Coman et.al. (2020), Online learning is that form of learning which is done through

different devices in the manner such as using an electronic media which is internet and some other

aspects of acquiring the knowledge and education from.

There are some key differences of online learning definitions which are being addressed as

that there are different definitions which the scholars have addressed to and this helps in analysing the

major concerns of how the online learning is being done (Singh and Thurman, 2019). Online learning

is also defined as internet ways through which learning is made easy and possible for students.

1

2.1 Introduction

This chapter aims to present a review of literature on perceptions of school teachers and

children in Saudi Arabia regarding online mathematics teaching and learning during the global

pandemic (2020–present). Specifically, the concept of online teaching and learning that includes

synchronous and asynchronous learning will be discussed. The study’s underpinning theories, namely

the Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework and the Self-efficacy

theory will be discussed. Finally, potential barriers and enablers concerning online mathematics

teaching and learning will be discussed.

2.2 online teaching and learning

2.2.1 Definitions

As denoted by Singh and Thurman, (2019), Online learning is defined as the education which takes

place over the internet. It is also defined as e – learning which is described in other forms.

As per Fitton, Finnegan and Proulx (2020), online learning is the learning where the students and are

learning through virtual environment. Online learning helps the student to learn and enhance their

knowledge and understanding in the form as to how effectively they are undertaking various measures

of learning.

According to Coman et.al. (2020), Online learning is that form of learning which is done through

different devices in the manner such as using an electronic media which is internet and some other

aspects of acquiring the knowledge and education from.

There are some key differences of online learning definitions which are being addressed as

that there are different definitions which the scholars have addressed to and this helps in analysing the

major concerns of how the online learning is being done (Singh and Thurman, 2019). Online learning

is also defined as internet ways through which learning is made easy and possible for students.

1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 116

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.