Nursing Home Resident Risks: Falls, Weight Loss, Pressure Ulcers

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/16

|11

|9558

|341

Report

AI Summary

This research article, published in the Journal of Clinical Nursing, investigates the factors associated with falls, weight loss, and pressure ulcers among nursing home residents. The study utilizes the Downton Fall Risk Index, the short form of Mini Nutritional Assessment, and the Modified Norton Scale to assess risks. Findings indicate that a significant portion of residents face multiple risks. While physical activity increased falls, it decreased pressure ulcers. Cognitive decline and general health status were most important for weight loss. The study emphasizes the need for a comprehensive approach to prevention, highlighting mobility as a critical factor. The research aims to provide insights into the interplay of different scale items and their relation to severe outcomes, contributing to improved care processes for frail older adults in nursing homes. The study highlights the complexity of risk group categorization and the importance of considering multiple factors in risk assessment, suggesting that total scores alone are insufficient for effective preventive work. The research underscores the challenge of balancing physical activity to prevent falls and pressure ulcers.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors related to falls, weight-loss and pressure ulcers – more insi

in risk assessment among nursing home residents

Christina Lannering, Marie Ernsth Bravell, Patrik Midl€ov, Carl-Johan€Ostgren and Sigvard M€olstad

Aims and objectives.To describe how the included items in three different scales,

Downton Fall Risk Index, the short form of Mini Nutritional Assessment and the

Modified Norton Scale are associated to severe outcomes as falls, weight loss and

pressure ulcers.

Background.Falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers are common adverse events

among nursing home residents and risk scoring are common preventive activities,

mainly focusing on single risks.In Sweden the three scalesare routinely used

together with the purpose to improve the quality of prevention.

Design.Longitudinal quantitative study.

Methods.Descriptive analyses and Cox regression analyses.

Results.Only 4% scored no risk for any of these serious events. Longitudinal risk

scoring showed significantimpaired mean scores indicating increased risks.This

confirms the complexity of this population’s status of general condition. There were

no statisticalsignificantdifferences between residents categorised atrisk or not

regarding events. Physical activity increased falls, but decreased pressure ulcers. For

weight loss, cognitive decline and the status of general health were most important.

Conclusions.Risk tendencies for falls,malnutrition and pressure ulcers are high in

nursing homes, and when measure them at the same time the majority will have several

of these risks. Items assessing mobility or items affecting mobility were of most impor-

tance. Care processes can always be improved and this study can add to the topic.

Relevance to clinical practice.A more comprehensive view is needed and prevention

can not only be based on total scores. Mobility is an important factor for falls and

pressure ulcers, both as a risk factor and a protective factor. This involves a challenge

for care – to keep the inmates physical active and at the same time prevent falls.

Key words:falls, frail older, malnutrition,nursing homes,pressure ulcers,risk

assessment

What does this paper contribute

to the wider global clinical

community?

The complexity to risk group cat-

egorise frailolder persons.Risk

tendencies for falls,malnutrition

and pressureulcers are high

among older people living in

nursing homes and the majority

will have severalrisks.The total

scores, which constitute basis for

risk grouping,are not always

sufficient information for the

preventive work as a more com-

prehensive view is needed.

Care processescan always be

improved.The resultsfrom this

study can contribute to the knowl-

edge on how to assess older frail

persons.Maybe thereare other

ways than using severalassessing

scales. Mobility remains an impor-

tantfactor,both as a risk factor

and a protective factor and that is

challenge for care to manage.

Accepted for publication: 5 November 2015

Authors: Christina Lannering, RN, PhD Student, Unit of Research and

Developmentin Primary Care,Futurum,J€onk€oping;Marie Ernsth

Bravell, PhD, RN, Associate professor, Institute of Gerontology, School

of Health Sciences,J €onk€oping University,J€onk€oping;Patrik Midl€ov,

MD, Associate Professor,Department of ClinicalSciences in Malm€o,

GeneralPractice/Family Medicine,Lund University,Malm€o; Carl-

Johan €Ostgren,MD, Professor,Departmentof Medicaland Health

Sciences,GeneralPractice,Link€oping University,Link€oping;Sigvard

M€olstad,MD, Professor,Department of ClinicalSciences in Malm€o,

General Practice/Family Medicine, Lund University, Malm€o, Sweden

Correspondence:Christina Lannering, PhD Student, Unit of

Research and Developmentin Primary Care,Futurum,SE-551 85

J €onk€oping, Sweden. Telephone: +4636325205.

E-mail: christina.lannering@rjl.se

A study aimed to provide more insight in how different scale items

interact with each other and how they are associated to severe out-

comes.It is not a prediction study or a study ofdiagnostic accu-

racy,but a study that can contribute to the field of knowledge of

assessments in older persons.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

940 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950, doi: 10.1111/jocn.13154

Factors related to falls, weight-loss and pressure ulcers – more insi

in risk assessment among nursing home residents

Christina Lannering, Marie Ernsth Bravell, Patrik Midl€ov, Carl-Johan€Ostgren and Sigvard M€olstad

Aims and objectives.To describe how the included items in three different scales,

Downton Fall Risk Index, the short form of Mini Nutritional Assessment and the

Modified Norton Scale are associated to severe outcomes as falls, weight loss and

pressure ulcers.

Background.Falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers are common adverse events

among nursing home residents and risk scoring are common preventive activities,

mainly focusing on single risks.In Sweden the three scalesare routinely used

together with the purpose to improve the quality of prevention.

Design.Longitudinal quantitative study.

Methods.Descriptive analyses and Cox regression analyses.

Results.Only 4% scored no risk for any of these serious events. Longitudinal risk

scoring showed significantimpaired mean scores indicating increased risks.This

confirms the complexity of this population’s status of general condition. There were

no statisticalsignificantdifferences between residents categorised atrisk or not

regarding events. Physical activity increased falls, but decreased pressure ulcers. For

weight loss, cognitive decline and the status of general health were most important.

Conclusions.Risk tendencies for falls,malnutrition and pressure ulcers are high in

nursing homes, and when measure them at the same time the majority will have several

of these risks. Items assessing mobility or items affecting mobility were of most impor-

tance. Care processes can always be improved and this study can add to the topic.

Relevance to clinical practice.A more comprehensive view is needed and prevention

can not only be based on total scores. Mobility is an important factor for falls and

pressure ulcers, both as a risk factor and a protective factor. This involves a challenge

for care – to keep the inmates physical active and at the same time prevent falls.

Key words:falls, frail older, malnutrition,nursing homes,pressure ulcers,risk

assessment

What does this paper contribute

to the wider global clinical

community?

The complexity to risk group cat-

egorise frailolder persons.Risk

tendencies for falls,malnutrition

and pressureulcers are high

among older people living in

nursing homes and the majority

will have severalrisks.The total

scores, which constitute basis for

risk grouping,are not always

sufficient information for the

preventive work as a more com-

prehensive view is needed.

Care processescan always be

improved.The resultsfrom this

study can contribute to the knowl-

edge on how to assess older frail

persons.Maybe thereare other

ways than using severalassessing

scales. Mobility remains an impor-

tantfactor,both as a risk factor

and a protective factor and that is

challenge for care to manage.

Accepted for publication: 5 November 2015

Authors: Christina Lannering, RN, PhD Student, Unit of Research and

Developmentin Primary Care,Futurum,J€onk€oping;Marie Ernsth

Bravell, PhD, RN, Associate professor, Institute of Gerontology, School

of Health Sciences,J €onk€oping University,J€onk€oping;Patrik Midl€ov,

MD, Associate Professor,Department of ClinicalSciences in Malm€o,

GeneralPractice/Family Medicine,Lund University,Malm€o; Carl-

Johan €Ostgren,MD, Professor,Departmentof Medicaland Health

Sciences,GeneralPractice,Link€oping University,Link€oping;Sigvard

M€olstad,MD, Professor,Department of ClinicalSciences in Malm€o,

General Practice/Family Medicine, Lund University, Malm€o, Sweden

Correspondence:Christina Lannering, PhD Student, Unit of

Research and Developmentin Primary Care,Futurum,SE-551 85

J €onk€oping, Sweden. Telephone: +4636325205.

E-mail: christina.lannering@rjl.se

A study aimed to provide more insight in how different scale items

interact with each other and how they are associated to severe out-

comes.It is not a prediction study or a study ofdiagnostic accu-

racy,but a study that can contribute to the field of knowledge of

assessments in older persons.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

940 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950, doi: 10.1111/jocn.13154

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Introduction

In Sweden, like in the rest of Western societies the numbers

of older people are increasing, and also the number of older

people needing care and services (WHO 2012). The munici-

pality has the responsibility to offer care in nursing home

facilities when the older person can no longermanage at

home. According to national statistics Sweden had approxi-

mately 87,600 persons at the age 65 and over permanently

staying in nursing home facilities.From these,80% were

aged above80 yearsand 69% were women (Board of

National Health and Welfare 2012). Old age care in Sweden

requires a need assessmentperformed by a specialtrained

social worker.The need assessment is based on the amount

of functionalproblemsperforming activitiesin daily life

(ADL). As a ‘stay-in-place’ policy is applied, home care ser-

vice is offered as long as possible. Moreover, the number of

beds in nursing homes has decreased by 20% during the last

10 years in Sweden (Board of National Health and Welfare

2012).These circumstances indicates that individuals mov-

ing in to nursing homes today are frailer and in more

extended need of care than previously.

To provide optimalcare and foremost preventive actions

it is essentialto know risk status, and helpful tools to

establish action policiescan be assessing scales.Accord-

ingly, scoring risk for falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers

are common preventive activities in the care of older people

and numerous scales and assessments are used for this pur-

pose.In Sweden the most common tools are Downton Fall

Risk Index (DFRI)to assess fallrisk (Downton 1993),the

short form of Mini Nutritional Assessment(MNA-SF)

(Rubenstein et al.2001) to assess risk for malnutrition and

the Modified Norton Scale (MNS) (Ek 1987) to assess risk

for developing pressure ulcers.

Background

Falls by older people in nursing home facilities are common

events. The prevalence of falls in institutionalised older peo-

ple is reported at 53–62% of the inmates (Rosendahlet al.

2003,Meyer et al.2009).Risk factors have been described

as gait and balanceinstability,cognitiveand functional

impairment, sedating and psychoactive medications (Ruben-

stein et al.1994) and numberof diseases(Damian et al.

2013). Some falls may be caused by a single factor,but the

majority of falls are caused by a combination offactors

(Cameron et al. 2010).

Older persons are also considered to be athigh risk of

malnutrition.Severalstudies in nursing homes populations

have shown both high risk and high prevalence of malnutri-

tion; a recent review showed that approximately 14% were

classified as malnourished and more than half were at risk

of malnutrition (Kaiser et al.2011).A follow-up study in

Swedish nursing homes showed thatnutritionalstatus was

improved,but still63% were assessed at risk,and 30% of

those were malnourished (Torma et al. 2013).

A third major and serious eventthat is common among

older persons in nursing homes is pressure ulcers.A recent

systematic review of pressure ulcers risk factor studies iden-

tified three primary risk domains;mobility/activity,perfu-

sion and generalskin status.However,no single factor can

predictpressure ulcer risk,which is caused by a complex

interplay of factors (Coleman et al.2013). A Swedish nurs-

ing home study showed a prevalence ofpressure ulcers at

14% and according to risk assessment,a risk between 26–

30% (Gunningberg et al.2013)which is similarto other

European studies (Meesterberends et al. 2013).

One must also consider ageing as a risk factor for these

outcomes,knowing that biological ageing increases the vul-

nerability and decreasesthe reserve capacity (Fried et al.

2001, Rockwood & Mitnitski 2007).

In Sweden,DFRI, MNS and MNA-SF are routinely used

togetherto assessrisks in older personsliving in nursing

homes. The scales are included in the quality registry Senior

Alert which is a nationalinvestmentaimed to increase the

quality of the preventive work.The widely used MNA was

developed and validated for the assessmentof older, frail

persons.MNA has a long history (Secher et al.2007) and

seems to be wellsuited for nursing home residents (Diek-

mann et al.2013).Further validation has shown thatthe

short-form can be used as a stand-alone unit(Bauer et al.

2008,Salviet al. 2008,Dent et al. 2012).DFRI was vali-

dated in a Swedish study(Rosendahlet al. 2003) and

appeared to bea useful tool for predicting fallsamong

older people in residentialcare facilities.However,a com-

parison with DFRI and nurses judgement alone showed no

clinical benefitfor DFRI (Meyer et al. 2009). MNS is

tested, recommended and well known in Sweden (Gunning-

berg et al.2013)and it is validated to itsactualcontent

(Ek & Bjurulf 1987).

It is reasonable to believe thatfrail older persons have

severalrisks and that generaldecline increasesserious

events,but using severaldifferentinstruments can be time

consuming and increase the workload asresultsmust be

documentedand interventionsshould be planned and

followed.Therefore,it is importantto put knowledge to

this topic so that nursescan reflectupon the usefulness.

One problem when using the three scales together is that

severalfunctionsare assessed repeatedly asthey existin

more than one scale. Mobility and cognition are,for exam-

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 941

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

In Sweden, like in the rest of Western societies the numbers

of older people are increasing, and also the number of older

people needing care and services (WHO 2012). The munici-

pality has the responsibility to offer care in nursing home

facilities when the older person can no longermanage at

home. According to national statistics Sweden had approxi-

mately 87,600 persons at the age 65 and over permanently

staying in nursing home facilities.From these,80% were

aged above80 yearsand 69% were women (Board of

National Health and Welfare 2012). Old age care in Sweden

requires a need assessmentperformed by a specialtrained

social worker.The need assessment is based on the amount

of functionalproblemsperforming activitiesin daily life

(ADL). As a ‘stay-in-place’ policy is applied, home care ser-

vice is offered as long as possible. Moreover, the number of

beds in nursing homes has decreased by 20% during the last

10 years in Sweden (Board of National Health and Welfare

2012).These circumstances indicates that individuals mov-

ing in to nursing homes today are frailer and in more

extended need of care than previously.

To provide optimalcare and foremost preventive actions

it is essentialto know risk status, and helpful tools to

establish action policiescan be assessing scales.Accord-

ingly, scoring risk for falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers

are common preventive activities in the care of older people

and numerous scales and assessments are used for this pur-

pose.In Sweden the most common tools are Downton Fall

Risk Index (DFRI)to assess fallrisk (Downton 1993),the

short form of Mini Nutritional Assessment(MNA-SF)

(Rubenstein et al.2001) to assess risk for malnutrition and

the Modified Norton Scale (MNS) (Ek 1987) to assess risk

for developing pressure ulcers.

Background

Falls by older people in nursing home facilities are common

events. The prevalence of falls in institutionalised older peo-

ple is reported at 53–62% of the inmates (Rosendahlet al.

2003,Meyer et al.2009).Risk factors have been described

as gait and balanceinstability,cognitiveand functional

impairment, sedating and psychoactive medications (Ruben-

stein et al.1994) and numberof diseases(Damian et al.

2013). Some falls may be caused by a single factor,but the

majority of falls are caused by a combination offactors

(Cameron et al. 2010).

Older persons are also considered to be athigh risk of

malnutrition.Severalstudies in nursing homes populations

have shown both high risk and high prevalence of malnutri-

tion; a recent review showed that approximately 14% were

classified as malnourished and more than half were at risk

of malnutrition (Kaiser et al.2011).A follow-up study in

Swedish nursing homes showed thatnutritionalstatus was

improved,but still63% were assessed at risk,and 30% of

those were malnourished (Torma et al. 2013).

A third major and serious eventthat is common among

older persons in nursing homes is pressure ulcers.A recent

systematic review of pressure ulcers risk factor studies iden-

tified three primary risk domains;mobility/activity,perfu-

sion and generalskin status.However,no single factor can

predictpressure ulcer risk,which is caused by a complex

interplay of factors (Coleman et al.2013). A Swedish nurs-

ing home study showed a prevalence ofpressure ulcers at

14% and according to risk assessment,a risk between 26–

30% (Gunningberg et al.2013)which is similarto other

European studies (Meesterberends et al. 2013).

One must also consider ageing as a risk factor for these

outcomes,knowing that biological ageing increases the vul-

nerability and decreasesthe reserve capacity (Fried et al.

2001, Rockwood & Mitnitski 2007).

In Sweden,DFRI, MNS and MNA-SF are routinely used

togetherto assessrisks in older personsliving in nursing

homes. The scales are included in the quality registry Senior

Alert which is a nationalinvestmentaimed to increase the

quality of the preventive work.The widely used MNA was

developed and validated for the assessmentof older, frail

persons.MNA has a long history (Secher et al.2007) and

seems to be wellsuited for nursing home residents (Diek-

mann et al.2013).Further validation has shown thatthe

short-form can be used as a stand-alone unit(Bauer et al.

2008,Salviet al. 2008,Dent et al. 2012).DFRI was vali-

dated in a Swedish study(Rosendahlet al. 2003) and

appeared to bea useful tool for predicting fallsamong

older people in residentialcare facilities.However,a com-

parison with DFRI and nurses judgement alone showed no

clinical benefitfor DFRI (Meyer et al. 2009). MNS is

tested, recommended and well known in Sweden (Gunning-

berg et al.2013)and it is validated to itsactualcontent

(Ek & Bjurulf 1987).

It is reasonable to believe thatfrail older persons have

severalrisks and that generaldecline increasesserious

events,but using severaldifferentinstruments can be time

consuming and increase the workload asresultsmust be

documentedand interventionsshould be planned and

followed.Therefore,it is importantto put knowledge to

this topic so that nursescan reflectupon the usefulness.

One problem when using the three scales together is that

severalfunctionsare assessed repeatedly asthey existin

more than one scale. Mobility and cognition are,for exam-

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 941

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

ple, assessed in allthree scalesbut in differentways and

with different grading. The ambition with the present study

is to gain knowledge aboutthe relationsamong the out-

comes and the included scale items.

Aim

This study aims to find patterns of associations among scale

risk items in MNA-SF,DFRI and MNS, with the outcomes

falls, pressure ulcers and weight-loss.

Method

Study population

Data from this study were collected from a longitudinal

cohort study of older people living in nursing homesin

Sweden;The Study on Health and Drugs in Elderly

(SHADES). The SHADES study was launched in 2008

and completed in 2011 and the overall aims were to

describeand analyse morbidity, health-conditionsand

drug-useamong olderpeoplein nursing homefacilities.

A convenience sample of12 nursing homes including 443

beds was included in the SHADES study. The nursing

homes were located in three differentregions in southern

Sweden and were allin the public sector.As participants

were included during the whole study period,the partici-

pants had differentdurationswhich consequently led to

varying number offollow-up assessments.When the study

nurse returned for a follow-up visit,all new inmates were

asked to participate,not just those who moved in where

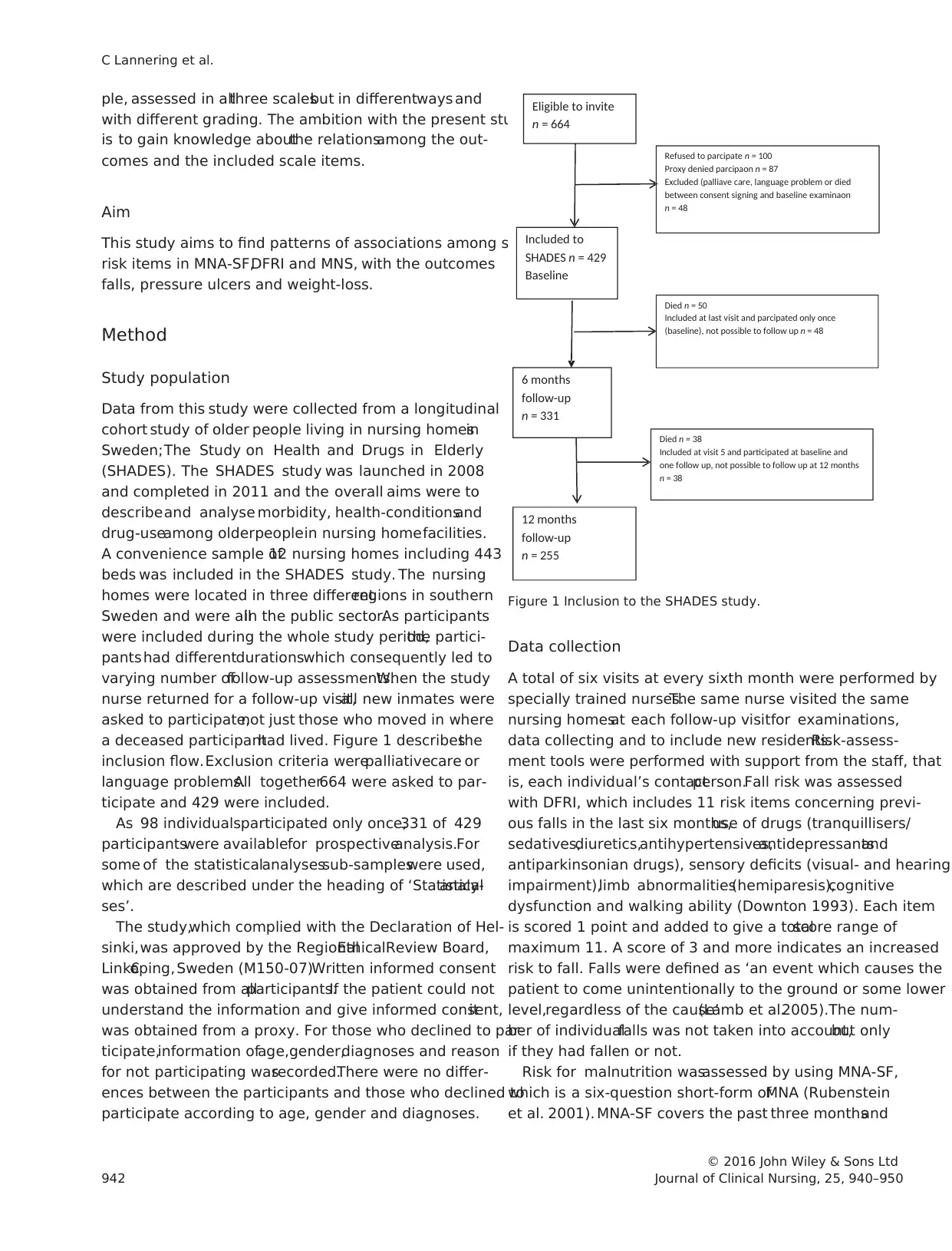

a deceased participanthad lived. Figure 1 describesthe

inclusion flow.Exclusion criteria werepalliativecare or

language problems.All together664 were asked to par-

ticipate and 429 were included.

As 98 individualsparticipated only once,331 of 429

participantswere availablefor prospectiveanalysis.For

some of the statisticalanalysessub-sampleswere used,

which are described under the heading of ‘Statisticalanaly-

ses’.

The study,which complied with the Declaration of Hel-

sinki,was approved by the RegionalEthicalReview Board,

Link€oping, Sweden (M150-07).Written informed consent

was obtained from allparticipants.If the patient could not

understand the information and give informed consent,it

was obtained from a proxy. For those who declined to par-

ticipate,information ofage,gender,diagnoses and reason

for not participating wasrecorded.There were no differ-

ences between the participants and those who declined to

participate according to age, gender and diagnoses.

Data collection

A total of six visits at every sixth month were performed by

specially trained nurses.The same nurse visited the same

nursing homesat each follow-up visitfor examinations,

data collecting and to include new residents.Risk-assess-

ment tools were performed with support from the staff, that

is, each individual’s contactperson.Fall risk was assessed

with DFRI, which includes 11 risk items concerning previ-

ous falls in the last six months,use of drugs (tranquillisers/

sedatives,diuretics,antihypertensives,antidepressantsand

antiparkinsonian drugs), sensory deficits (visual- and hearing

impairment),limb abnormalities(hemiparesis),cognitive

dysfunction and walking ability (Downton 1993). Each item

is scored 1 point and added to give a totalscore range of

maximum 11. A score of 3 and more indicates an increased

risk to fall. Falls were defined as ‘an event which causes the

patient to come unintentionally to the ground or some lower

level,regardless of the cause’(Lamb et al.2005).The num-

ber of individualfalls was not taken into account,but only

if they had fallen or not.

Risk for malnutrition wasassessed by using MNA-SF,

which is a six-question short-form ofMNA (Rubenstein

et al. 2001). MNA-SF covers the past three monthsand

Eligible to invite

n = 664

Refused to parcipate n = 100

Proxy denied parcipaon n = 87

Excluded (palliave care, language problem or died

between consent signing and baseline examinaon

n = 48

Included to

SHADES n = 429

Baseline

6 months

follow-up

n = 331

Died n = 50

Included at last visit and parcipated only once

(baseline), not possible to follow up n = 48

Died n = 38

Included at visit 5 and participated at baseline and

one follow up, not possible to follow up at 12 months

n = 38

12 months

follow-up

n = 255

Figure 1 Inclusion to the SHADES study.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

942 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

with different grading. The ambition with the present study

is to gain knowledge aboutthe relationsamong the out-

comes and the included scale items.

Aim

This study aims to find patterns of associations among scale

risk items in MNA-SF,DFRI and MNS, with the outcomes

falls, pressure ulcers and weight-loss.

Method

Study population

Data from this study were collected from a longitudinal

cohort study of older people living in nursing homesin

Sweden;The Study on Health and Drugs in Elderly

(SHADES). The SHADES study was launched in 2008

and completed in 2011 and the overall aims were to

describeand analyse morbidity, health-conditionsand

drug-useamong olderpeoplein nursing homefacilities.

A convenience sample of12 nursing homes including 443

beds was included in the SHADES study. The nursing

homes were located in three differentregions in southern

Sweden and were allin the public sector.As participants

were included during the whole study period,the partici-

pants had differentdurationswhich consequently led to

varying number offollow-up assessments.When the study

nurse returned for a follow-up visit,all new inmates were

asked to participate,not just those who moved in where

a deceased participanthad lived. Figure 1 describesthe

inclusion flow.Exclusion criteria werepalliativecare or

language problems.All together664 were asked to par-

ticipate and 429 were included.

As 98 individualsparticipated only once,331 of 429

participantswere availablefor prospectiveanalysis.For

some of the statisticalanalysessub-sampleswere used,

which are described under the heading of ‘Statisticalanaly-

ses’.

The study,which complied with the Declaration of Hel-

sinki,was approved by the RegionalEthicalReview Board,

Link€oping, Sweden (M150-07).Written informed consent

was obtained from allparticipants.If the patient could not

understand the information and give informed consent,it

was obtained from a proxy. For those who declined to par-

ticipate,information ofage,gender,diagnoses and reason

for not participating wasrecorded.There were no differ-

ences between the participants and those who declined to

participate according to age, gender and diagnoses.

Data collection

A total of six visits at every sixth month were performed by

specially trained nurses.The same nurse visited the same

nursing homesat each follow-up visitfor examinations,

data collecting and to include new residents.Risk-assess-

ment tools were performed with support from the staff, that

is, each individual’s contactperson.Fall risk was assessed

with DFRI, which includes 11 risk items concerning previ-

ous falls in the last six months,use of drugs (tranquillisers/

sedatives,diuretics,antihypertensives,antidepressantsand

antiparkinsonian drugs), sensory deficits (visual- and hearing

impairment),limb abnormalities(hemiparesis),cognitive

dysfunction and walking ability (Downton 1993). Each item

is scored 1 point and added to give a totalscore range of

maximum 11. A score of 3 and more indicates an increased

risk to fall. Falls were defined as ‘an event which causes the

patient to come unintentionally to the ground or some lower

level,regardless of the cause’(Lamb et al.2005).The num-

ber of individualfalls was not taken into account,but only

if they had fallen or not.

Risk for malnutrition wasassessed by using MNA-SF,

which is a six-question short-form ofMNA (Rubenstein

et al. 2001). MNA-SF covers the past three monthsand

Eligible to invite

n = 664

Refused to parcipate n = 100

Proxy denied parcipaon n = 87

Excluded (palliave care, language problem or died

between consent signing and baseline examinaon

n = 48

Included to

SHADES n = 429

Baseline

6 months

follow-up

n = 331

Died n = 50

Included at last visit and parcipated only once

(baseline), not possible to follow up n = 48

Died n = 38

Included at visit 5 and participated at baseline and

one follow up, not possible to follow up at 12 months

n = 38

12 months

follow-up

n = 255

Figure 1 Inclusion to the SHADES study.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

942 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

addressesdecreased food intake(0–2 points), estimated

weight loss (0–3 points), mobility (0–2 points), acute diseases

or psychologicalstress (0 or 2 points),neuropsychological

impairment (0–2 points) and BMI (0–3 points).The higher

the value the lower the risk. The maximum MNA-SF score is

14 points. A score of 7 points or less indicates malnutrition,

8–11 indicates risk of malnutrition and 12–14 points indi-

cates no risk for malnutrition.

Risk for pressure ulcers was assessed with MNS. In addi-

tion to the more internationally known Norton Scale, MNS

also includestwo items assessing nutrition status.MNS

consists of seven items; mental condition, activity, mobility,

food intake,fluid intake,incontinence and generalphysical

condition.Each item is assessed with a range from 1 (lack

of function) to 4 (normalfunction).The maximum score is

28 and a score at20 or lower indicates an increased risk

for pressure ulcers (Ek 1987).

The scales internal consistency in this study, measured by

Cronbach’salpha showed 05 for DFRI, 066 for MNS

and 045 for MNA-SF.

In the SHADES study the nursesexamined the partici-

pants in many ways regarding differentassessmentscales,

blood testing,use of drugs,different measurements etc.For

this presentstudy we used data from DFRI, MNA-SF,

MNS, data of weight and data of eventual presence of pres-

sure ulcers.Pressure ulcerswere graded as:(1) persistent

discoloration,with intactskin surface;(2) epithelialdam-

age;(3) damage to the fullthickness of the skin without a

deep cavity and (4) damage to the full thickness of the skin

with deep cavity.In this study,all kinds of pressure ulcers

were taken into account,but not gradated,only counted as

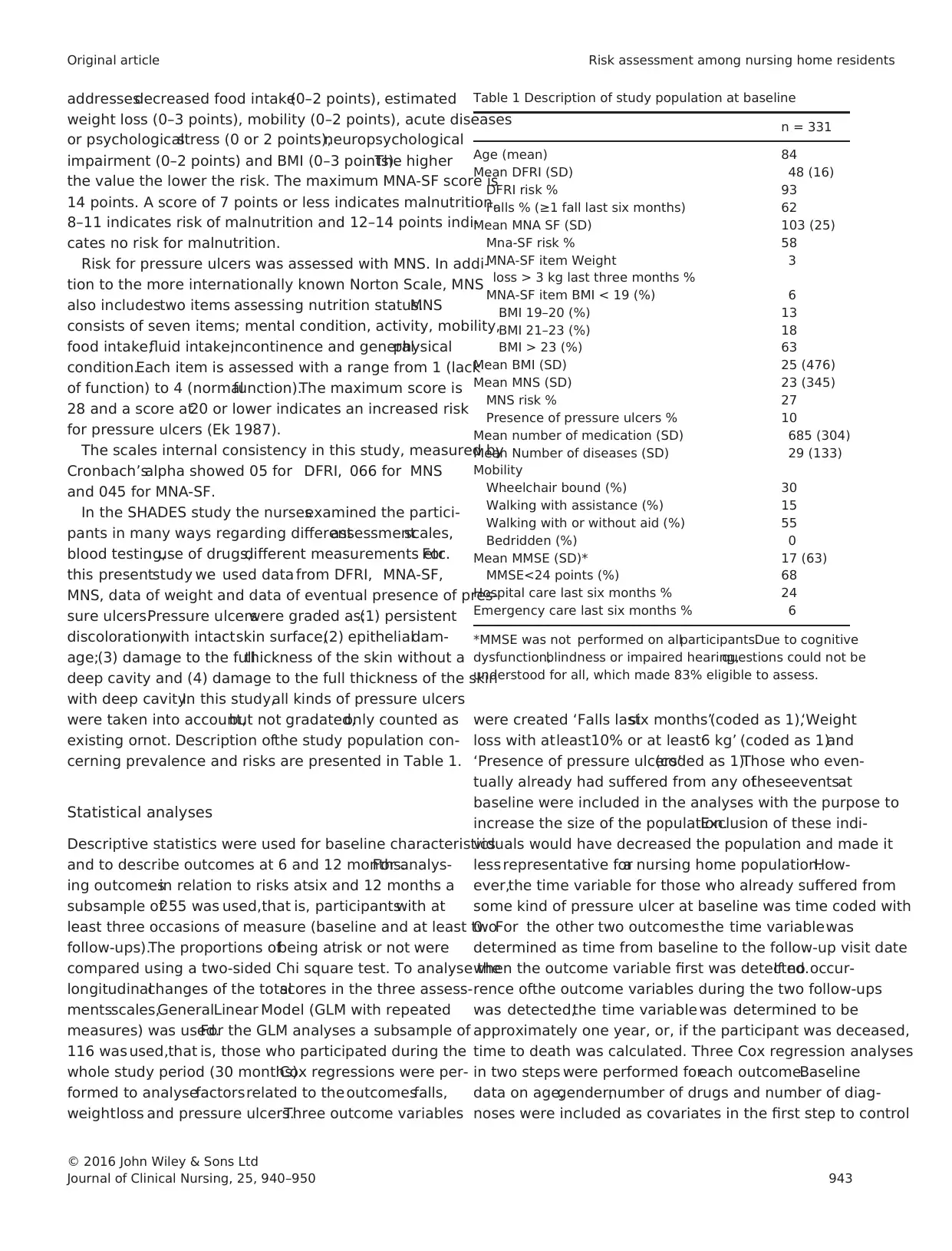

existing ornot. Description ofthe study population con-

cerning prevalence and risks are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics

and to describe outcomes at 6 and 12 months.For analys-

ing outcomesin relation to risks atsix and 12 months a

subsample of255 was used,that is, participantswith at

least three occasions of measure (baseline and at least two

follow-ups).The proportions ofbeing atrisk or not were

compared using a two-sided Chi square test. To analyse the

longitudinalchanges of the totalscores in the three assess-

mentsscales,GeneralLinear Model (GLM with repeated

measures) was used.For the GLM analyses a subsample of

116 was used,that is, those who participated during the

whole study period (30 months).Cox regressions were per-

formed to analysefactorsrelated to the outcomesfalls,

weightloss and pressure ulcers.Three outcome variables

were created ‘Falls lastsix months’(coded as 1),‘Weight

loss with atleast10% or at least6 kg’ (coded as 1)and

‘Presence of pressure ulcers’(coded as 1).Those who even-

tually already had suffered from any oftheseeventsat

baseline were included in the analyses with the purpose to

increase the size of the population.Exclusion of these indi-

viduals would have decreased the population and made it

less representative fora nursing home population.How-

ever,the time variable for those who already suffered from

some kind of pressure ulcer at baseline was time coded with

0. For the other two outcomesthe time variablewas

determined as time from baseline to the follow-up visit date

when the outcome variable first was detected.If no occur-

rence ofthe outcome variables during the two follow-ups

was detected,the time variable was determined to be

approximately one year, or, if the participant was deceased,

time to death was calculated. Three Cox regression analyses

in two steps were performed foreach outcome.Baseline

data on age,gender,number of drugs and number of diag-

noses were included as covariates in the first step to control

Table 1 Description of study population at baseline

n = 331

Age (mean) 84

Mean DFRI (SD) 48 (16)

DFRI risk % 93

Falls % (≥1 fall last six months) 62

Mean MNA SF (SD) 103 (25)

Mna-SF risk % 58

MNA-SF item Weight

loss > 3 kg last three months %

3

MNA-SF item BMI < 19 (%) 6

BMI 19–20 (%) 13

BMI 21–23 (%) 18

BMI > 23 (%) 63

Mean BMI (SD) 25 (476)

Mean MNS (SD) 23 (345)

MNS risk % 27

Presence of pressure ulcers % 10

Mean number of medication (SD) 685 (304)

Mean Number of diseases (SD) 29 (133)

Mobility

Wheelchair bound (%) 30

Walking with assistance (%) 15

Walking with or without aid (%) 55

Bedridden (%) 0

Mean MMSE (SD)* 17 (63)

MMSE<24 points (%) 68

Hospital care last six months % 24

Emergency care last six months % 6

*MMSE was not performed on allparticipants.Due to cognitive

dysfunction,blindness or impaired hearing,questions could not be

understood for all, which made 83% eligible to assess.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 943

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

weight loss (0–3 points), mobility (0–2 points), acute diseases

or psychologicalstress (0 or 2 points),neuropsychological

impairment (0–2 points) and BMI (0–3 points).The higher

the value the lower the risk. The maximum MNA-SF score is

14 points. A score of 7 points or less indicates malnutrition,

8–11 indicates risk of malnutrition and 12–14 points indi-

cates no risk for malnutrition.

Risk for pressure ulcers was assessed with MNS. In addi-

tion to the more internationally known Norton Scale, MNS

also includestwo items assessing nutrition status.MNS

consists of seven items; mental condition, activity, mobility,

food intake,fluid intake,incontinence and generalphysical

condition.Each item is assessed with a range from 1 (lack

of function) to 4 (normalfunction).The maximum score is

28 and a score at20 or lower indicates an increased risk

for pressure ulcers (Ek 1987).

The scales internal consistency in this study, measured by

Cronbach’salpha showed 05 for DFRI, 066 for MNS

and 045 for MNA-SF.

In the SHADES study the nursesexamined the partici-

pants in many ways regarding differentassessmentscales,

blood testing,use of drugs,different measurements etc.For

this presentstudy we used data from DFRI, MNA-SF,

MNS, data of weight and data of eventual presence of pres-

sure ulcers.Pressure ulcerswere graded as:(1) persistent

discoloration,with intactskin surface;(2) epithelialdam-

age;(3) damage to the fullthickness of the skin without a

deep cavity and (4) damage to the full thickness of the skin

with deep cavity.In this study,all kinds of pressure ulcers

were taken into account,but not gradated,only counted as

existing ornot. Description ofthe study population con-

cerning prevalence and risks are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics

and to describe outcomes at 6 and 12 months.For analys-

ing outcomesin relation to risks atsix and 12 months a

subsample of255 was used,that is, participantswith at

least three occasions of measure (baseline and at least two

follow-ups).The proportions ofbeing atrisk or not were

compared using a two-sided Chi square test. To analyse the

longitudinalchanges of the totalscores in the three assess-

mentsscales,GeneralLinear Model (GLM with repeated

measures) was used.For the GLM analyses a subsample of

116 was used,that is, those who participated during the

whole study period (30 months).Cox regressions were per-

formed to analysefactorsrelated to the outcomesfalls,

weightloss and pressure ulcers.Three outcome variables

were created ‘Falls lastsix months’(coded as 1),‘Weight

loss with atleast10% or at least6 kg’ (coded as 1)and

‘Presence of pressure ulcers’(coded as 1).Those who even-

tually already had suffered from any oftheseeventsat

baseline were included in the analyses with the purpose to

increase the size of the population.Exclusion of these indi-

viduals would have decreased the population and made it

less representative fora nursing home population.How-

ever,the time variable for those who already suffered from

some kind of pressure ulcer at baseline was time coded with

0. For the other two outcomesthe time variablewas

determined as time from baseline to the follow-up visit date

when the outcome variable first was detected.If no occur-

rence ofthe outcome variables during the two follow-ups

was detected,the time variable was determined to be

approximately one year, or, if the participant was deceased,

time to death was calculated. Three Cox regression analyses

in two steps were performed foreach outcome.Baseline

data on age,gender,number of drugs and number of diag-

noses were included as covariates in the first step to control

Table 1 Description of study population at baseline

n = 331

Age (mean) 84

Mean DFRI (SD) 48 (16)

DFRI risk % 93

Falls % (≥1 fall last six months) 62

Mean MNA SF (SD) 103 (25)

Mna-SF risk % 58

MNA-SF item Weight

loss > 3 kg last three months %

3

MNA-SF item BMI < 19 (%) 6

BMI 19–20 (%) 13

BMI 21–23 (%) 18

BMI > 23 (%) 63

Mean BMI (SD) 25 (476)

Mean MNS (SD) 23 (345)

MNS risk % 27

Presence of pressure ulcers % 10

Mean number of medication (SD) 685 (304)

Mean Number of diseases (SD) 29 (133)

Mobility

Wheelchair bound (%) 30

Walking with assistance (%) 15

Walking with or without aid (%) 55

Bedridden (%) 0

Mean MMSE (SD)* 17 (63)

MMSE<24 points (%) 68

Hospital care last six months % 24

Emergency care last six months % 6

*MMSE was not performed on allparticipants.Due to cognitive

dysfunction,blindness or impaired hearing,questions could not be

understood for all, which made 83% eligible to assess.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 943

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

for sociodemographics and health.In the second step,the

scale items for one scale were included as covariates.This

procedure wasthen repeated foreach scale,respectively,

which made a total of nine regression models. Finally, three

two-step Cox regression analyses were performed with the

sociodemographics described above as covariates in the first

step and the totalscores of each scale as covariates in the

next step.

Analyseswere performed using theSPSS statisticalsoft-

ware (IBM SPSS version 20, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

p-values ≤005 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of study population

A sample oftotal 331 residents had consecutive and com-

plete data from baseline to at least one follow-up. Of those,

mean age was 84 years (SD 7) and 71% were female.The

subjects had been staying at the nursing homes for in med-

ian 10 months.At baseline (Table 1),the study population

demonstrated a considerable risk forfall n = 307 (93%),

malnutrition n = 192 (58%)and pressureulcers n = 89

(27%). Combination of risks were more common than sin-

gle risk as 25% had risk for both fall, malnutrition and

pressure ulcers and 32% had risk for two ofthese condi-

tions.Single risk was demonstrated at39%, but only 4%

of the sample scored no risk atany of the three assessing

scales at baseline.

To see how the totalscore values for DFRI,MNS and

MNA-SF varied over time, repeated measureswere anal-

ysed in several GLMs. The result showed statistically signif-

icant impaired mean scores;MNS decreased from 2309 to

2094 (p < 0001),MNA-SF decreased from 1076 to 934

(p < 0001) and DRFI increasedfrom 458 to 488

(p < 005).

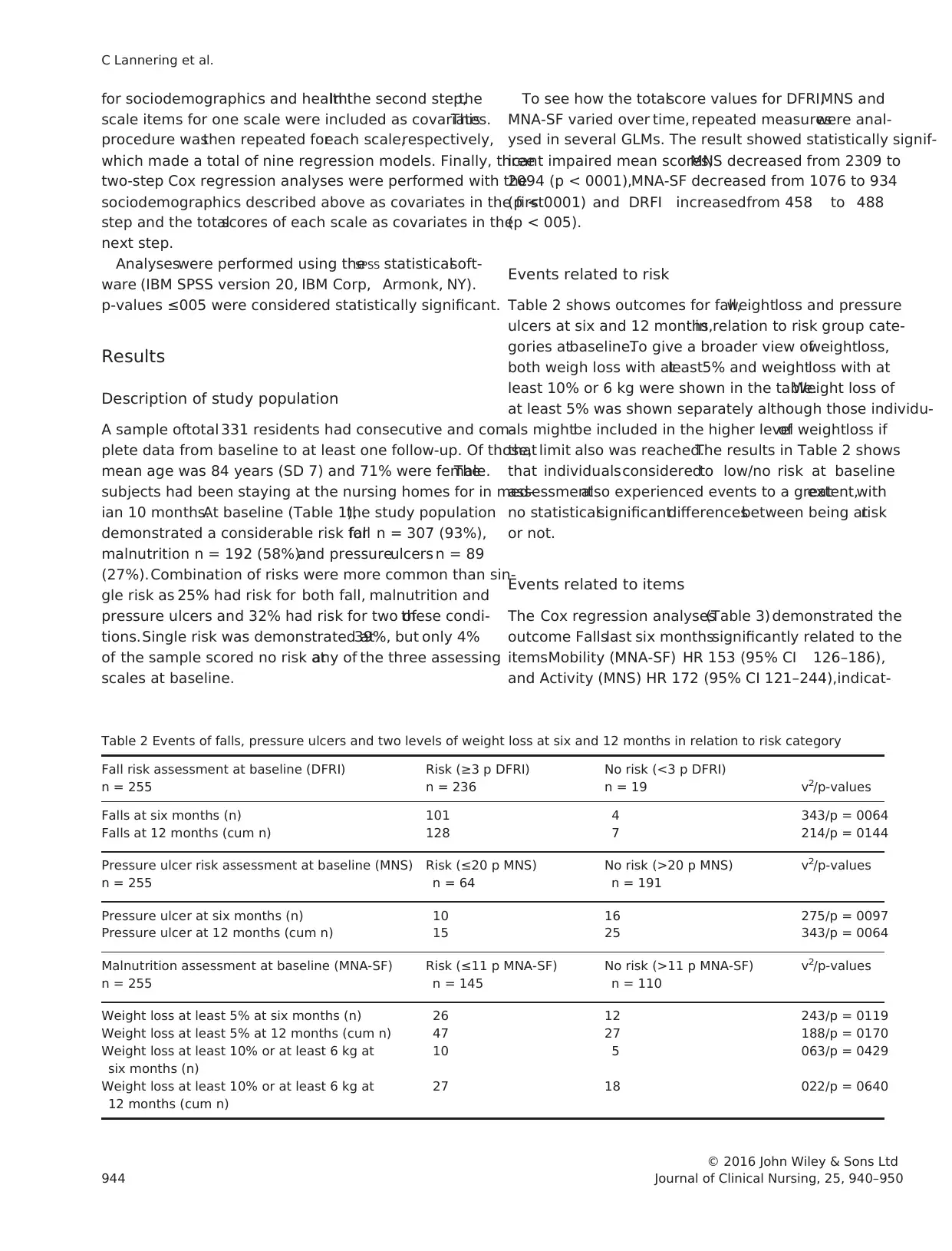

Events related to risk

Table 2 shows outcomes for fall,weightloss and pressure

ulcers at six and 12 months,in relation to risk group cate-

gories atbaseline.To give a broader view ofweightloss,

both weigh loss with atleast5% and weightloss with at

least 10% or 6 kg were shown in the table.Weight loss of

at least 5% was shown separately although those individu-

als mightbe included in the higher levelof weightloss if

that limit also was reached.The results in Table 2 shows

that individualsconsideredto low/no risk at baseline

assessmentalso experienced events to a greatextent,with

no statisticalsignificantdifferencesbetween being atrisk

or not.

Events related to items

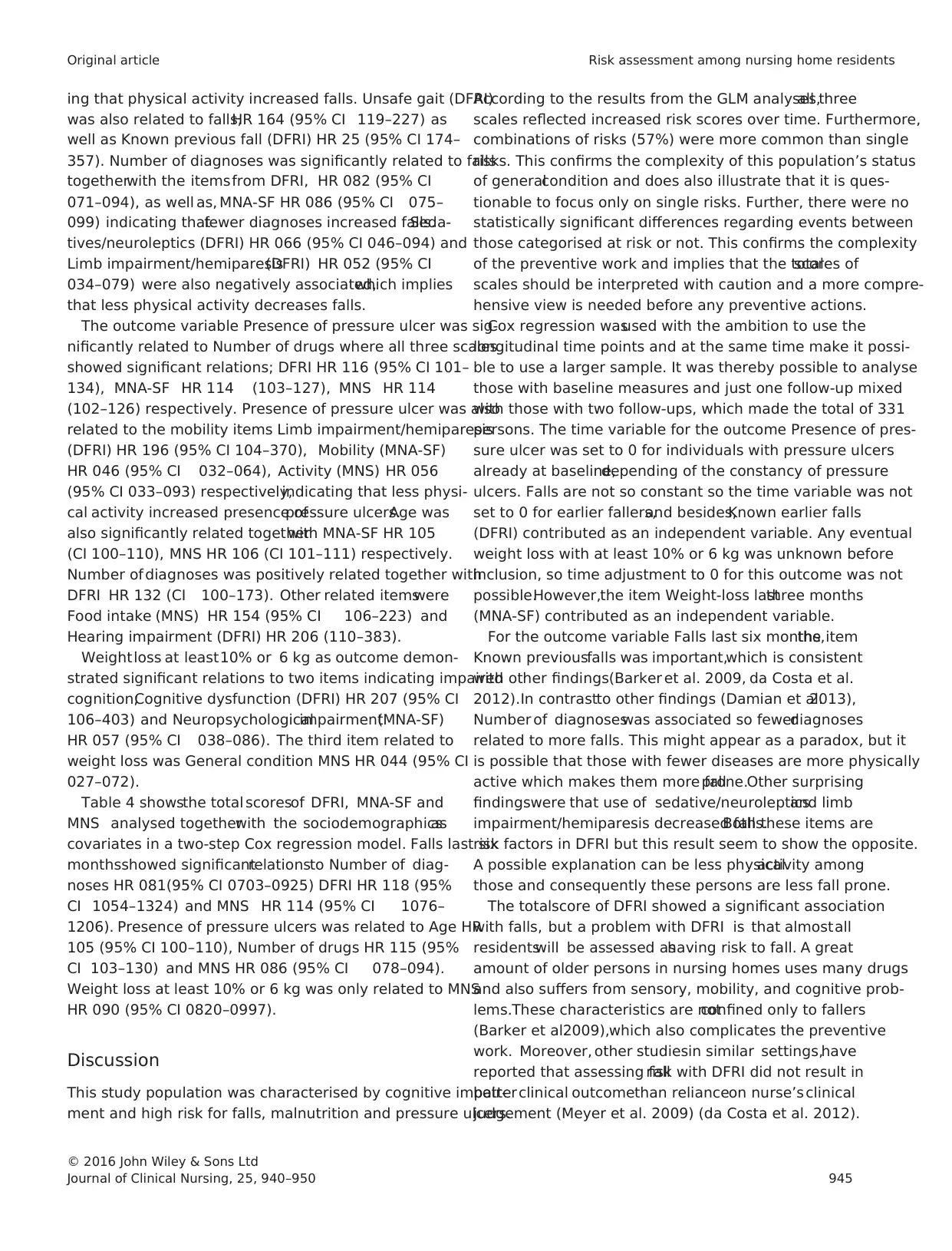

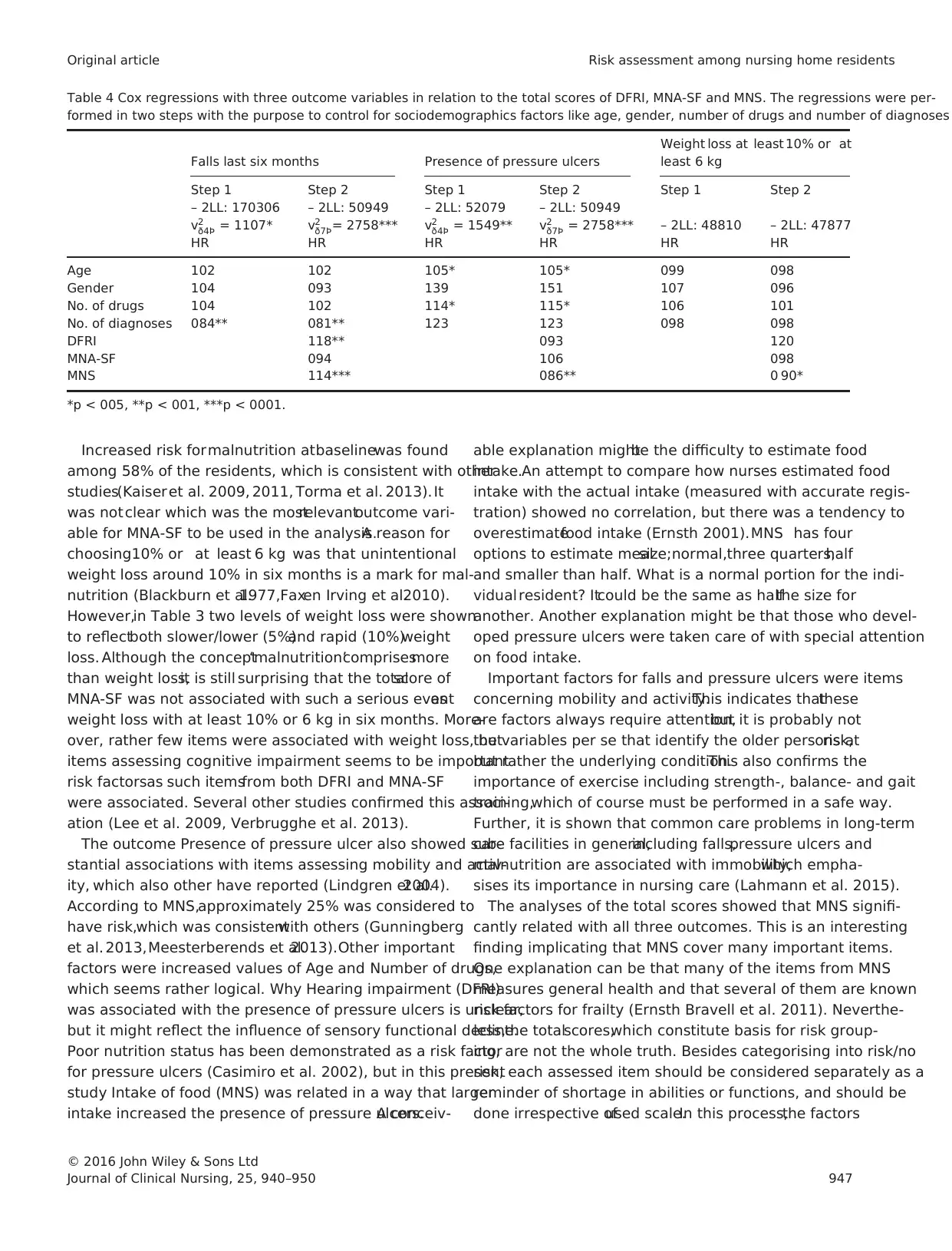

The Cox regression analyses(Table 3) demonstrated the

outcome Fallslast six monthssignificantly related to the

itemsMobility (MNA-SF) HR 153 (95% CI 126–186),

and Activity (MNS) HR 172 (95% CI 121–244),indicat-

Table 2 Events of falls, pressure ulcers and two levels of weight loss at six and 12 months in relation to risk category

Fall risk assessment at baseline (DFRI)

n = 255

Risk (≥3 p DFRI)

n = 236

No risk (<3 p DFRI)

n = 19 v2/p-values

Falls at six months (n) 101 4 343/p = 0064

Falls at 12 months (cum n) 128 7 214/p = 0144

Pressure ulcer risk assessment at baseline (MNS)

n = 255

Risk (≤20 p MNS)

n = 64

No risk (>20 p MNS)

n = 191

v2/p-values

Pressure ulcer at six months (n) 10 16 275/p = 0097

Pressure ulcer at 12 months (cum n) 15 25 343/p = 0064

Malnutrition assessment at baseline (MNA-SF)

n = 255

Risk (≤11 p MNA-SF)

n = 145

No risk (>11 p MNA-SF)

n = 110

v2/p-values

Weight loss at least 5% at six months (n) 26 12 243/p = 0119

Weight loss at least 5% at 12 months (cum n) 47 27 188/p = 0170

Weight loss at least 10% or at least 6 kg at

six months (n)

10 5 063/p = 0429

Weight loss at least 10% or at least 6 kg at

12 months (cum n)

27 18 022/p = 0640

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

944 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

scale items for one scale were included as covariates.This

procedure wasthen repeated foreach scale,respectively,

which made a total of nine regression models. Finally, three

two-step Cox regression analyses were performed with the

sociodemographics described above as covariates in the first

step and the totalscores of each scale as covariates in the

next step.

Analyseswere performed using theSPSS statisticalsoft-

ware (IBM SPSS version 20, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

p-values ≤005 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of study population

A sample oftotal 331 residents had consecutive and com-

plete data from baseline to at least one follow-up. Of those,

mean age was 84 years (SD 7) and 71% were female.The

subjects had been staying at the nursing homes for in med-

ian 10 months.At baseline (Table 1),the study population

demonstrated a considerable risk forfall n = 307 (93%),

malnutrition n = 192 (58%)and pressureulcers n = 89

(27%). Combination of risks were more common than sin-

gle risk as 25% had risk for both fall, malnutrition and

pressure ulcers and 32% had risk for two ofthese condi-

tions.Single risk was demonstrated at39%, but only 4%

of the sample scored no risk atany of the three assessing

scales at baseline.

To see how the totalscore values for DFRI,MNS and

MNA-SF varied over time, repeated measureswere anal-

ysed in several GLMs. The result showed statistically signif-

icant impaired mean scores;MNS decreased from 2309 to

2094 (p < 0001),MNA-SF decreased from 1076 to 934

(p < 0001) and DRFI increasedfrom 458 to 488

(p < 005).

Events related to risk

Table 2 shows outcomes for fall,weightloss and pressure

ulcers at six and 12 months,in relation to risk group cate-

gories atbaseline.To give a broader view ofweightloss,

both weigh loss with atleast5% and weightloss with at

least 10% or 6 kg were shown in the table.Weight loss of

at least 5% was shown separately although those individu-

als mightbe included in the higher levelof weightloss if

that limit also was reached.The results in Table 2 shows

that individualsconsideredto low/no risk at baseline

assessmentalso experienced events to a greatextent,with

no statisticalsignificantdifferencesbetween being atrisk

or not.

Events related to items

The Cox regression analyses(Table 3) demonstrated the

outcome Fallslast six monthssignificantly related to the

itemsMobility (MNA-SF) HR 153 (95% CI 126–186),

and Activity (MNS) HR 172 (95% CI 121–244),indicat-

Table 2 Events of falls, pressure ulcers and two levels of weight loss at six and 12 months in relation to risk category

Fall risk assessment at baseline (DFRI)

n = 255

Risk (≥3 p DFRI)

n = 236

No risk (<3 p DFRI)

n = 19 v2/p-values

Falls at six months (n) 101 4 343/p = 0064

Falls at 12 months (cum n) 128 7 214/p = 0144

Pressure ulcer risk assessment at baseline (MNS)

n = 255

Risk (≤20 p MNS)

n = 64

No risk (>20 p MNS)

n = 191

v2/p-values

Pressure ulcer at six months (n) 10 16 275/p = 0097

Pressure ulcer at 12 months (cum n) 15 25 343/p = 0064

Malnutrition assessment at baseline (MNA-SF)

n = 255

Risk (≤11 p MNA-SF)

n = 145

No risk (>11 p MNA-SF)

n = 110

v2/p-values

Weight loss at least 5% at six months (n) 26 12 243/p = 0119

Weight loss at least 5% at 12 months (cum n) 47 27 188/p = 0170

Weight loss at least 10% or at least 6 kg at

six months (n)

10 5 063/p = 0429

Weight loss at least 10% or at least 6 kg at

12 months (cum n)

27 18 022/p = 0640

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

944 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

ing that physical activity increased falls. Unsafe gait (DFRI)

was also related to falls,HR 164 (95% CI 119–227) as

well as Known previous fall (DFRI) HR 25 (95% CI 174–

357). Number of diagnoses was significantly related to falls

togetherwith the itemsfrom DFRI, HR 082 (95% CI

071–094), as well as, MNA-SF HR 086 (95% CI 075–

099) indicating thatfewer diagnoses increased falls.Seda-

tives/neuroleptics (DFRI) HR 066 (95% CI 046–094) and

Limb impairment/hemiparesis(DFRI) HR 052 (95% CI

034–079) were also negatively associated,which implies

that less physical activity decreases falls.

The outcome variable Presence of pressure ulcer was sig-

nificantly related to Number of drugs where all three scales

showed significant relations; DFRI HR 116 (95% CI 101–

134), MNA-SF HR 114 (103–127), MNS HR 114

(102–126) respectively. Presence of pressure ulcer was also

related to the mobility items Limb impairment/hemiparesis

(DFRI) HR 196 (95% CI 104–370), Mobility (MNA-SF)

HR 046 (95% CI 032–064), Activity (MNS) HR 056

(95% CI 033–093) respectively,indicating that less physi-

cal activity increased presence ofpressure ulcers.Age was

also significantly related togetherwith MNA-SF HR 105

(CI 100–110), MNS HR 106 (CI 101–111) respectively.

Number of diagnoses was positively related together with

DFRI HR 132 (CI 100–173). Other related itemswere

Food intake (MNS) HR 154 (95% CI 106–223) and

Hearing impairment (DFRI) HR 206 (110–383).

Weightloss at least10% or 6 kg as outcome demon-

strated significant relations to two items indicating impaired

cognition;Cognitive dysfunction (DFRI) HR 207 (95% CI

106–403) and Neuropsychologicalimpairment(MNA-SF)

HR 057 (95% CI 038–086). The third item related to

weight loss was General condition MNS HR 044 (95% CI

027–072).

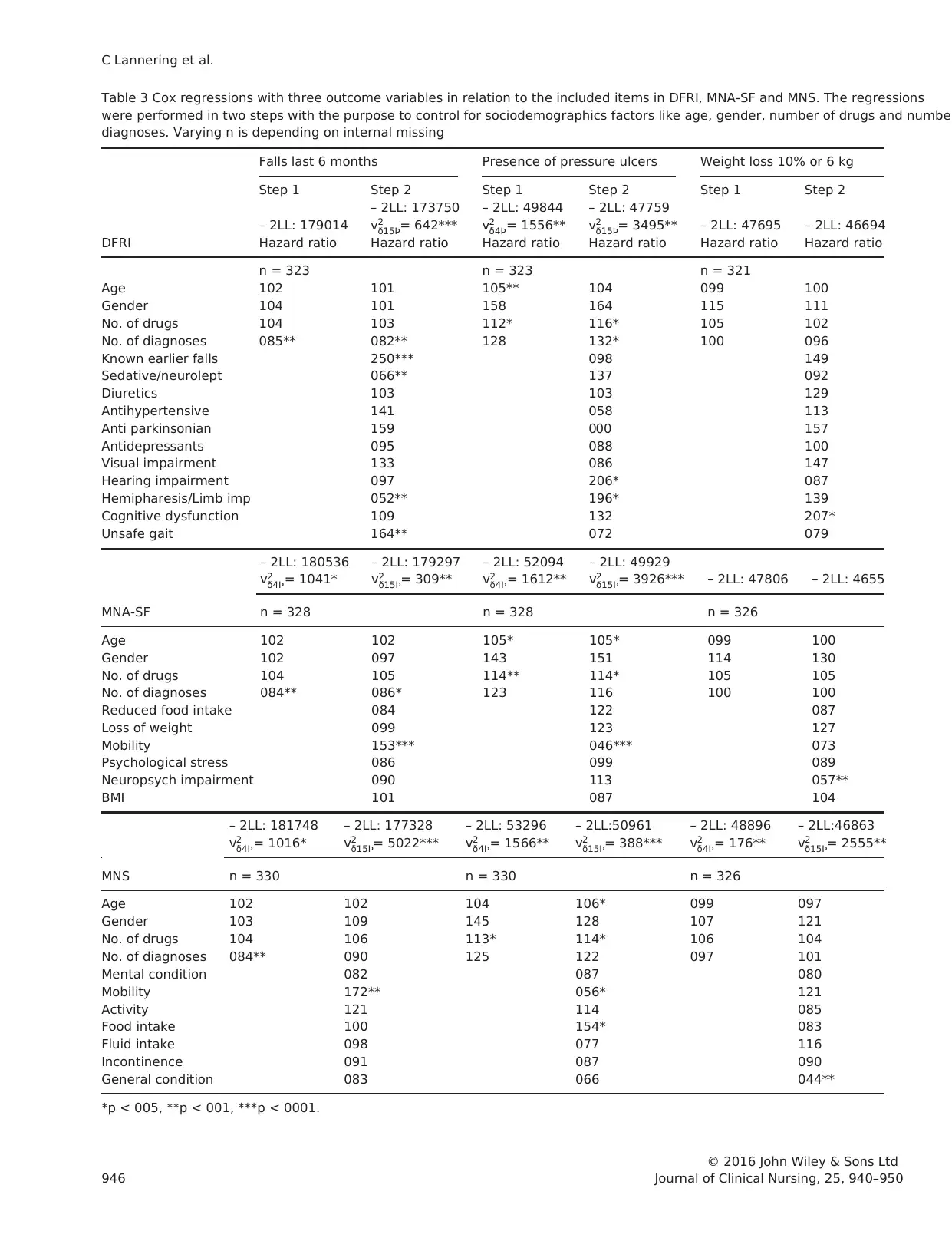

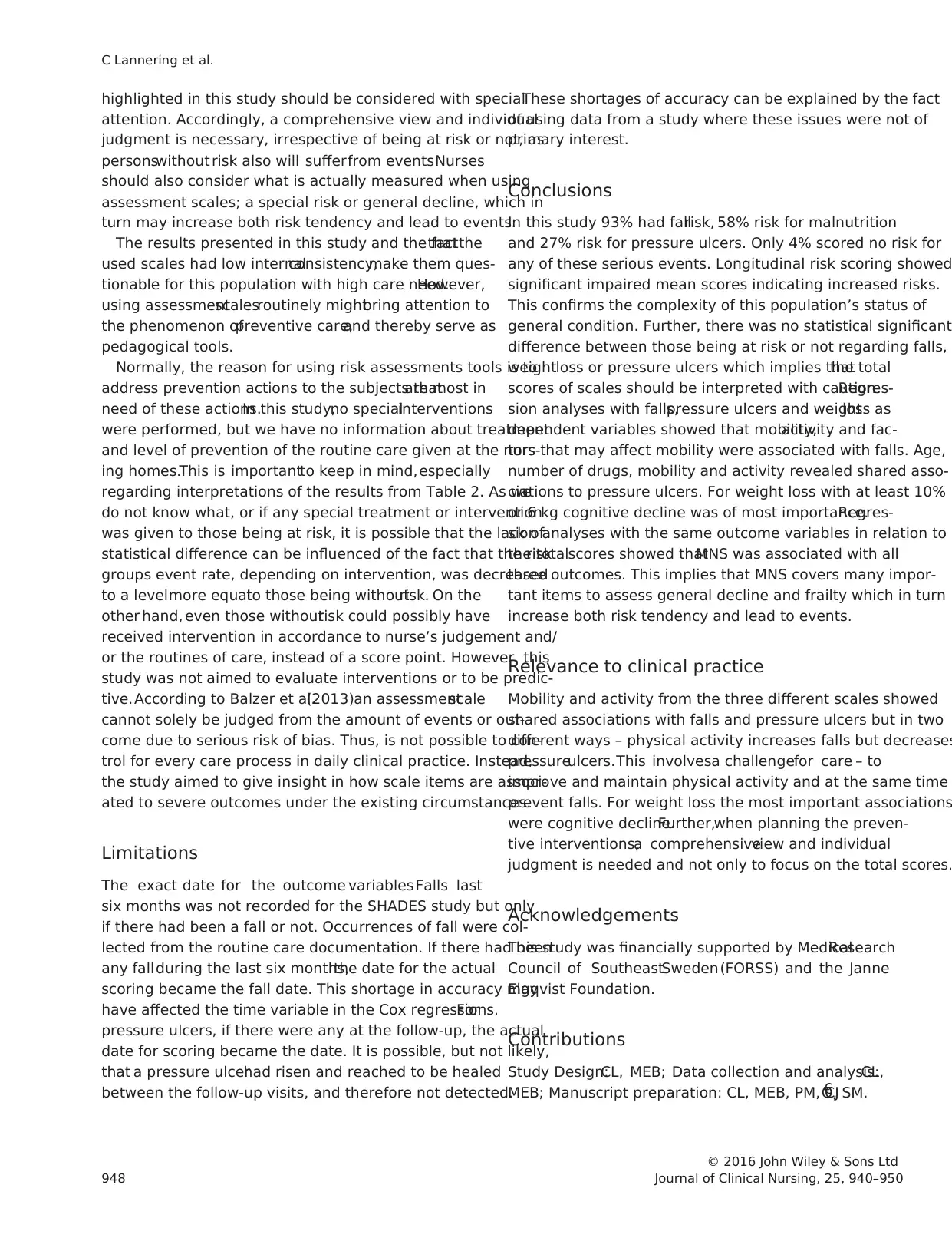

Table 4 showsthe total scoresof DFRI, MNA-SF and

MNS analysed togetherwith the sociodemographicsas

covariates in a two-step Cox regression model. Falls last six

monthsshowed significantrelationsto Number of diag-

noses HR 081(95% CI 0703–0925) DFRI HR 118 (95%

CI 1054–1324) and MNS HR 114 (95% CI 1076–

1206). Presence of pressure ulcers was related to Age HR

105 (95% CI 100–110), Number of drugs HR 115 (95%

CI 103–130) and MNS HR 086 (95% CI 078–094).

Weight loss at least 10% or 6 kg was only related to MNS

HR 090 (95% CI 0820–0997).

Discussion

This study population was characterised by cognitive impair-

ment and high risk for falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers.

According to the results from the GLM analyses,all three

scales reflected increased risk scores over time. Furthermore,

combinations of risks (57%) were more common than single

risks. This confirms the complexity of this population’s status

of generalcondition and does also illustrate that it is ques-

tionable to focus only on single risks. Further, there were no

statistically significant differences regarding events between

those categorised at risk or not. This confirms the complexity

of the preventive work and implies that the totalscores of

scales should be interpreted with caution and a more compre-

hensive view is needed before any preventive actions.

Cox regression wasused with the ambition to use the

longitudinal time points and at the same time make it possi-

ble to use a larger sample. It was thereby possible to analyse

those with baseline measures and just one follow-up mixed

with those with two follow-ups, which made the total of 331

persons. The time variable for the outcome Presence of pres-

sure ulcer was set to 0 for individuals with pressure ulcers

already at baseline,depending of the constancy of pressure

ulcers. Falls are not so constant so the time variable was not

set to 0 for earlier fallers,and besides,Known earlier falls

(DFRI) contributed as an independent variable. Any eventual

weight loss with at least 10% or 6 kg was unknown before

inclusion, so time adjustment to 0 for this outcome was not

possible.However,the item Weight-loss lastthree months

(MNA-SF) contributed as an independent variable.

For the outcome variable Falls last six months,the item

Known previousfalls was important,which is consistent

with other findings(Barker et al. 2009, da Costa et al.

2012).In contrastto other findings (Damian et al.2013),

Number of diagnoseswas associated so fewerdiagnoses

related to more falls. This might appear as a paradox, but it

is possible that those with fewer diseases are more physically

active which makes them more fallprone.Other surprising

findingswere that use of sedative/neurolepticsand limb

impairment/hemiparesis decreased falls.Both these items are

risk factors in DFRI but this result seem to show the opposite.

A possible explanation can be less physicalactivity among

those and consequently these persons are less fall prone.

The totalscore of DFRI showed a significant association

with falls, but a problem with DFRI is that almostall

residentswill be assessed ashaving risk to fall. A great

amount of older persons in nursing homes uses many drugs

and also suffers from sensory, mobility, and cognitive prob-

lems.These characteristics are notconfined only to fallers

(Barker et al.2009),which also complicates the preventive

work. Moreover, other studiesin similar settings,have

reported that assessing fallrisk with DFRI did not result in

betterclinical outcomethan relianceon nurse’s clinical

judgement (Meyer et al. 2009) (da Costa et al. 2012).

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 945

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

was also related to falls,HR 164 (95% CI 119–227) as

well as Known previous fall (DFRI) HR 25 (95% CI 174–

357). Number of diagnoses was significantly related to falls

togetherwith the itemsfrom DFRI, HR 082 (95% CI

071–094), as well as, MNA-SF HR 086 (95% CI 075–

099) indicating thatfewer diagnoses increased falls.Seda-

tives/neuroleptics (DFRI) HR 066 (95% CI 046–094) and

Limb impairment/hemiparesis(DFRI) HR 052 (95% CI

034–079) were also negatively associated,which implies

that less physical activity decreases falls.

The outcome variable Presence of pressure ulcer was sig-

nificantly related to Number of drugs where all three scales

showed significant relations; DFRI HR 116 (95% CI 101–

134), MNA-SF HR 114 (103–127), MNS HR 114

(102–126) respectively. Presence of pressure ulcer was also

related to the mobility items Limb impairment/hemiparesis

(DFRI) HR 196 (95% CI 104–370), Mobility (MNA-SF)

HR 046 (95% CI 032–064), Activity (MNS) HR 056

(95% CI 033–093) respectively,indicating that less physi-

cal activity increased presence ofpressure ulcers.Age was

also significantly related togetherwith MNA-SF HR 105

(CI 100–110), MNS HR 106 (CI 101–111) respectively.

Number of diagnoses was positively related together with

DFRI HR 132 (CI 100–173). Other related itemswere

Food intake (MNS) HR 154 (95% CI 106–223) and

Hearing impairment (DFRI) HR 206 (110–383).

Weightloss at least10% or 6 kg as outcome demon-

strated significant relations to two items indicating impaired

cognition;Cognitive dysfunction (DFRI) HR 207 (95% CI

106–403) and Neuropsychologicalimpairment(MNA-SF)

HR 057 (95% CI 038–086). The third item related to

weight loss was General condition MNS HR 044 (95% CI

027–072).

Table 4 showsthe total scoresof DFRI, MNA-SF and

MNS analysed togetherwith the sociodemographicsas

covariates in a two-step Cox regression model. Falls last six

monthsshowed significantrelationsto Number of diag-

noses HR 081(95% CI 0703–0925) DFRI HR 118 (95%

CI 1054–1324) and MNS HR 114 (95% CI 1076–

1206). Presence of pressure ulcers was related to Age HR

105 (95% CI 100–110), Number of drugs HR 115 (95%

CI 103–130) and MNS HR 086 (95% CI 078–094).

Weight loss at least 10% or 6 kg was only related to MNS

HR 090 (95% CI 0820–0997).

Discussion

This study population was characterised by cognitive impair-

ment and high risk for falls, malnutrition and pressure ulcers.

According to the results from the GLM analyses,all three

scales reflected increased risk scores over time. Furthermore,

combinations of risks (57%) were more common than single

risks. This confirms the complexity of this population’s status

of generalcondition and does also illustrate that it is ques-

tionable to focus only on single risks. Further, there were no

statistically significant differences regarding events between

those categorised at risk or not. This confirms the complexity

of the preventive work and implies that the totalscores of

scales should be interpreted with caution and a more compre-

hensive view is needed before any preventive actions.

Cox regression wasused with the ambition to use the

longitudinal time points and at the same time make it possi-

ble to use a larger sample. It was thereby possible to analyse

those with baseline measures and just one follow-up mixed

with those with two follow-ups, which made the total of 331

persons. The time variable for the outcome Presence of pres-

sure ulcer was set to 0 for individuals with pressure ulcers

already at baseline,depending of the constancy of pressure

ulcers. Falls are not so constant so the time variable was not

set to 0 for earlier fallers,and besides,Known earlier falls

(DFRI) contributed as an independent variable. Any eventual

weight loss with at least 10% or 6 kg was unknown before

inclusion, so time adjustment to 0 for this outcome was not

possible.However,the item Weight-loss lastthree months

(MNA-SF) contributed as an independent variable.

For the outcome variable Falls last six months,the item

Known previousfalls was important,which is consistent

with other findings(Barker et al. 2009, da Costa et al.

2012).In contrastto other findings (Damian et al.2013),

Number of diagnoseswas associated so fewerdiagnoses

related to more falls. This might appear as a paradox, but it

is possible that those with fewer diseases are more physically

active which makes them more fallprone.Other surprising

findingswere that use of sedative/neurolepticsand limb

impairment/hemiparesis decreased falls.Both these items are

risk factors in DFRI but this result seem to show the opposite.

A possible explanation can be less physicalactivity among

those and consequently these persons are less fall prone.

The totalscore of DFRI showed a significant association

with falls, but a problem with DFRI is that almostall

residentswill be assessed ashaving risk to fall. A great

amount of older persons in nursing homes uses many drugs

and also suffers from sensory, mobility, and cognitive prob-

lems.These characteristics are notconfined only to fallers

(Barker et al.2009),which also complicates the preventive

work. Moreover, other studiesin similar settings,have

reported that assessing fallrisk with DFRI did not result in

betterclinical outcomethan relianceon nurse’s clinical

judgement (Meyer et al. 2009) (da Costa et al. 2012).

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 945

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 3 Cox regressions with three outcome variables in relation to the included items in DFRI, MNA-SF and MNS. The regressions

were performed in two steps with the purpose to control for sociodemographics factors like age, gender, number of drugs and number

diagnoses. Varying n is depending on internal missing

DFRI

Falls last 6 months Presence of pressure ulcers Weight loss 10% or 6 kg

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

– 2LL: 179014

– 2LL: 173750

v2

ð15Þ= 642***

– 2LL: 49844

v2

ð4Þ= 1556**

– 2LL: 47759

v2

ð15Þ= 3495** – 2LL: 47695 – 2LL: 46694

Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio

n = 323 n = 323 n = 321

Age 102 101 105** 104 099 100

Gender 104 101 158 164 115 111

No. of drugs 104 103 112* 116* 105 102

No. of diagnoses 085** 082** 128 132* 100 096

Known earlier falls 250*** 098 149

Sedative/neurolept 066** 137 092

Diuretics 103 103 129

Antihypertensive 141 058 113

Anti parkinsonian 159 000 157

Antidepressants 095 088 100

Visual impairment 133 086 147

Hearing impairment 097 206* 087

Hemipharesis/Limb imp 052** 196* 139

Cognitive dysfunction 109 132 207*

Unsafe gait 164** 072 079

– 2LL: 180536

v2

ð4Þ= 1041*

– 2LL: 179297

v2

ð15Þ= 309**

– 2LL: 52094

v2

ð4Þ= 1612**

– 2LL: 49929

v2

ð15Þ= 3926*** – 2LL: 47806 – 2LL: 4655

MNA-SF n = 328 n = 328 n = 326

Age 102 102 105* 105* 099 100

Gender 102 097 143 151 114 130

No. of drugs 104 105 114** 114* 105 105

No. of diagnoses 084** 086* 123 116 100 100

Reduced food intake 084 122 087

Loss of weight 099 123 127

Mobility 153*** 046*** 073

Psychological stress 086 099 089

Neuropsych impairment 090 113 057**

BMI 101 087 104

– 2LL: 181748

v2

ð4Þ= 1016*

– 2LL: 177328

v2

ð15Þ= 5022***

– 2LL: 53296

v2

ð4Þ= 1566**

– 2LL:50961

v2

ð15Þ= 388***

– 2LL: 48896

v2

ð4Þ= 176**

– 2LL:46863

v2

ð15Þ= 2555**

MNS n = 330 n = 330 n = 326

Age 102 102 104 106* 099 097

Gender 103 109 145 128 107 121

No. of drugs 104 106 113* 114* 106 104

No. of diagnoses 084** 090 125 122 097 101

Mental condition 082 087 080

Mobility 172** 056* 121

Activity 121 114 085

Food intake 100 154* 083

Fluid intake 098 077 116

Incontinence 091 087 090

General condition 083 066 044**

*p < 005, **p < 001, ***p < 0001.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

946 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

were performed in two steps with the purpose to control for sociodemographics factors like age, gender, number of drugs and number

diagnoses. Varying n is depending on internal missing

DFRI

Falls last 6 months Presence of pressure ulcers Weight loss 10% or 6 kg

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

– 2LL: 179014

– 2LL: 173750

v2

ð15Þ= 642***

– 2LL: 49844

v2

ð4Þ= 1556**

– 2LL: 47759

v2

ð15Þ= 3495** – 2LL: 47695 – 2LL: 46694

Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio Hazard ratio

n = 323 n = 323 n = 321

Age 102 101 105** 104 099 100

Gender 104 101 158 164 115 111

No. of drugs 104 103 112* 116* 105 102

No. of diagnoses 085** 082** 128 132* 100 096

Known earlier falls 250*** 098 149

Sedative/neurolept 066** 137 092

Diuretics 103 103 129

Antihypertensive 141 058 113

Anti parkinsonian 159 000 157

Antidepressants 095 088 100

Visual impairment 133 086 147

Hearing impairment 097 206* 087

Hemipharesis/Limb imp 052** 196* 139

Cognitive dysfunction 109 132 207*

Unsafe gait 164** 072 079

– 2LL: 180536

v2

ð4Þ= 1041*

– 2LL: 179297

v2

ð15Þ= 309**

– 2LL: 52094

v2

ð4Þ= 1612**

– 2LL: 49929

v2

ð15Þ= 3926*** – 2LL: 47806 – 2LL: 4655

MNA-SF n = 328 n = 328 n = 326

Age 102 102 105* 105* 099 100

Gender 102 097 143 151 114 130

No. of drugs 104 105 114** 114* 105 105

No. of diagnoses 084** 086* 123 116 100 100

Reduced food intake 084 122 087

Loss of weight 099 123 127

Mobility 153*** 046*** 073

Psychological stress 086 099 089

Neuropsych impairment 090 113 057**

BMI 101 087 104

– 2LL: 181748

v2

ð4Þ= 1016*

– 2LL: 177328

v2

ð15Þ= 5022***

– 2LL: 53296

v2

ð4Þ= 1566**

– 2LL:50961

v2

ð15Þ= 388***

– 2LL: 48896

v2

ð4Þ= 176**

– 2LL:46863

v2

ð15Þ= 2555**

MNS n = 330 n = 330 n = 326

Age 102 102 104 106* 099 097

Gender 103 109 145 128 107 121

No. of drugs 104 106 113* 114* 106 104

No. of diagnoses 084** 090 125 122 097 101

Mental condition 082 087 080

Mobility 172** 056* 121

Activity 121 114 085

Food intake 100 154* 083

Fluid intake 098 077 116

Incontinence 091 087 090

General condition 083 066 044**

*p < 005, **p < 001, ***p < 0001.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

946 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950

C Lannering et al.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Increased risk formalnutrition atbaselinewas found

among 58% of the residents, which is consistent with other

studies(Kaiser et al. 2009, 2011, Torma et al. 2013). It

was not clear which was the mostrelevantoutcome vari-

able for MNA-SF to be used in the analysis.A reason for

choosing10% or at least 6 kg was that unintentional

weight loss around 10% in six months is a mark for mal-

nutrition (Blackburn et al.1977,Faxen Irving et al.2010).

However,in Table 3 two levels of weight loss were shown

to reflectboth slower/lower (5%)and rapid (10%)weight

loss. Although the concept‘malnutrition’comprisesmore

than weight loss,it is still surprising that the totalscore of

MNA-SF was not associated with such a serious eventas

weight loss with at least 10% or 6 kg in six months. More-

over, rather few items were associated with weight loss, but

items assessing cognitive impairment seems to be important

risk factorsas such itemsfrom both DFRI and MNA-SF

were associated. Several other studies confirmed this associ-

ation (Lee et al. 2009, Verbrugghe et al. 2013).

The outcome Presence of pressure ulcer also showed sub-

stantial associations with items assessing mobility and activ-

ity, which also other have reported (Lindgren et al.2004).

According to MNS,approximately 25% was considered to

have risk,which was consistentwith others (Gunningberg

et al. 2013,Meesterberends et al.2013).Other important

factors were increased values of Age and Number of drugs,

which seems rather logical. Why Hearing impairment (DFRI)

was associated with the presence of pressure ulcers is unclear,

but it might reflect the influence of sensory functional decline.

Poor nutrition status has been demonstrated as a risk factor

for pressure ulcers (Casimiro et al. 2002), but in this present

study Intake of food (MNS) was related in a way that larger

intake increased the presence of pressure ulcers.A conceiv-

able explanation mightbe the difficulty to estimate food

intake.An attempt to compare how nurses estimated food

intake with the actual intake (measured with accurate regis-

tration) showed no correlation, but there was a tendency to

overestimatefood intake (Ernsth 2001).MNS has four

options to estimate mealsize;normal,three quarters,half

and smaller than half. What is a normal portion for the indi-

vidual resident? Itcould be the same as halfthe size for

another. Another explanation might be that those who devel-

oped pressure ulcers were taken care of with special attention

on food intake.

Important factors for falls and pressure ulcers were items

concerning mobility and activity.This indicates thatthese

are factors always require attention,but it is probably not

the variables per se that identify the older persons atrisk,

but rather the underlying condition.This also confirms the

importance of exercise including strength-, balance- and gait

training,which of course must be performed in a safe way.

Further, it is shown that common care problems in long-term

care facilities in general,including falls,pressure ulcers and

malnutrition are associated with immobility,which empha-

sises its importance in nursing care (Lahmann et al. 2015).

The analyses of the total scores showed that MNS signifi-

cantly related with all three outcomes. This is an interesting

finding implicating that MNS cover many important items.

One explanation can be that many of the items from MNS

measures general health and that several of them are known

risk factors for frailty (Ernsth Bravell et al. 2011). Neverthe-

less,the totalscores,which constitute basis for risk group-

ing, are not the whole truth. Besides categorising into risk/no

risk, each assessed item should be considered separately as a

reminder of shortage in abilities or functions, and should be

done irrespective ofused scale.In this process,the factors

Table 4 Cox regressions with three outcome variables in relation to the total scores of DFRI, MNA-SF and MNS. The regressions were per-

formed in two steps with the purpose to control for sociodemographics factors like age, gender, number of drugs and number of diagnoses

Falls last six months Presence of pressure ulcers

Weight loss at least 10% or at

least 6 kg

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

– 2LL: 170306

v2

ð4Þ = 1107*

– 2LL: 50949

v2

ð7Þ= 2758***

– 2LL: 52079

v2

ð4Þ = 1549**

– 2LL: 50949

v2

ð7Þ = 2758*** – 2LL: 48810 – 2LL: 47877

HR HR HR HR HR HR

Age 102 102 105* 105* 099 098

Gender 104 093 139 151 107 096

No. of drugs 104 102 114* 115* 106 101

No. of diagnoses 084** 081** 123 123 098 098

DFRI 118** 093 120

MNA-SF 094 106 098

MNS 114*** 086** 0 90*

*p < 005, **p < 001, ***p < 0001.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 940–950 947

Original article Risk assessment among nursing home residents

among 58% of the residents, which is consistent with other

studies(Kaiser et al. 2009, 2011, Torma et al. 2013). It

was not clear which was the mostrelevantoutcome vari-

able for MNA-SF to be used in the analysis.A reason for

choosing10% or at least 6 kg was that unintentional

weight loss around 10% in six months is a mark for mal-

nutrition (Blackburn et al.1977,Faxen Irving et al.2010).

However,in Table 3 two levels of weight loss were shown

to reflectboth slower/lower (5%)and rapid (10%)weight

loss. Although the concept‘malnutrition’comprisesmore

than weight loss,it is still surprising that the totalscore of

MNA-SF was not associated with such a serious eventas

weight loss with at least 10% or 6 kg in six months. More-

over, rather few items were associated with weight loss, but

items assessing cognitive impairment seems to be important

risk factorsas such itemsfrom both DFRI and MNA-SF

were associated. Several other studies confirmed this associ-

ation (Lee et al. 2009, Verbrugghe et al. 2013).

The outcome Presence of pressure ulcer also showed sub-

stantial associations with items assessing mobility and activ-

ity, which also other have reported (Lindgren et al.2004).

According to MNS,approximately 25% was considered to

have risk,which was consistentwith others (Gunningberg

et al. 2013,Meesterberends et al.2013).Other important

factors were increased values of Age and Number of drugs,

which seems rather logical. Why Hearing impairment (DFRI)

was associated with the presence of pressure ulcers is unclear,

but it might reflect the influence of sensory functional decline.

Poor nutrition status has been demonstrated as a risk factor

for pressure ulcers (Casimiro et al. 2002), but in this present

study Intake of food (MNS) was related in a way that larger

intake increased the presence of pressure ulcers.A conceiv-

able explanation mightbe the difficulty to estimate food

intake.An attempt to compare how nurses estimated food

intake with the actual intake (measured with accurate regis-

tration) showed no correlation, but there was a tendency to

overestimatefood intake (Ernsth 2001).MNS has four

options to estimate mealsize;normal,three quarters,half

and smaller than half. What is a normal portion for the indi-

vidual resident? Itcould be the same as halfthe size for

another. Another explanation might be that those who devel-

oped pressure ulcers were taken care of with special attention

on food intake.

Important factors for falls and pressure ulcers were items

concerning mobility and activity.This indicates thatthese

are factors always require attention,but it is probably not

the variables per se that identify the older persons atrisk,

but rather the underlying condition.This also confirms the

importance of exercise including strength-, balance- and gait

training,which of course must be performed in a safe way.

Further, it is shown that common care problems in long-term

care facilities in general,including falls,pressure ulcers and

malnutrition are associated with immobility,which empha-

sises its importance in nursing care (Lahmann et al. 2015).

The analyses of the total scores showed that MNS signifi-

cantly related with all three outcomes. This is an interesting

finding implicating that MNS cover many important items.

One explanation can be that many of the items from MNS

measures general health and that several of them are known

risk factors for frailty (Ernsth Bravell et al. 2011). Neverthe-

less,the totalscores,which constitute basis for risk group-

ing, are not the whole truth. Besides categorising into risk/no

risk, each assessed item should be considered separately as a

reminder of shortage in abilities or functions, and should be

done irrespective ofused scale.In this process,the factors

Table 4 Cox regressions with three outcome variables in relation to the total scores of DFRI, MNA-SF and MNS. The regressions were per-

formed in two steps with the purpose to control for sociodemographics factors like age, gender, number of drugs and number of diagnoses

Falls last six months Presence of pressure ulcers

Weight loss at least 10% or at

least 6 kg

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

– 2LL: 170306

v2

ð4Þ = 1107*

– 2LL: 50949

v2

ð7Þ= 2758***

– 2LL: 52079

v2

ð4Þ = 1549**

– 2LL: 50949

v2

ð7Þ = 2758*** – 2LL: 48810 – 2LL: 47877

HR HR HR HR HR HR

Age 102 102 105* 105* 099 098

Gender 104 093 139 151 107 096

No. of drugs 104 102 114* 115* 106 101

No. of diagnoses 084** 081** 123 123 098 098

DFRI 118** 093 120