Systematic Review: Validity and Reliability of Myers-Briggs Indicator

VerifiedAdded on 2022/12/30

|28

|12353

|44

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), examining its validity and reliability. The study analyzed seven studies to assess the psychometric properties of the MBTI, which is frequently used in health professions and educational programs. The review investigated construct validity and test-retest reliability across the Extravert-Introvert, Sensing-Intuition, Thinking-Feeling, and Judging-Perceiving subscales. Findings suggest satisfactory reliabilities for most subscales, though heterogeneity was noted. The report highlights the importance of considering the MBTI's applicability to different populations, as the majority of studies were conducted on college-age students. The study underscores the need for careful interpretation of MBTI results and provides valuable insights for educators and practitioners using the instrument. This report is contributed by a student to be published on Desklib, a platform offering AI-based study tools.

J Best Pract Health Prof Divers (Spring, 2017), 10(1), 1–27.

ISSN: 2745-2843 © Winston-Salem State University

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Validity and Reliability of the

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Ken Randall,1 PhD, MHR, PT; Mary Isaacson,1 EdD;

Carrie Ciro,1 PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

Author Affiliations:1Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Oklahoma Health

Sciences Center, Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Corresponding Author: Ken Randall, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, University

of Oklahoma Schusterman Center, 4502 East 41st Street, Room 2H20, Tulsa, OK 74135

(Ken-Randall@ouhsc.edu)

ABSTRACT

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is frequently used by health professions and educationa

programs to address the diversity of personalities that exist. No systematic review of the

ture or meta-analysis of its validity and reliability has occurred. This comprehensive liter

search identified 221 potential studies, of which seven met our inclusion criteria. Four of

studies examined construct validity, but their varying methods did not permit pooling fo

meta-analysis. These studies agree that the instrument has reasonable construct validity

three studies of test-retest reliability did allow a meta-analysis to be performed, albeit w

tion due to substantial heterogeneity. Results indicate that the Extravert-Introvert, Sens

Intuition, and Judging-Perceiving Subscales have satisfactory reliabilities of .75 or higher

that the Thinking-Feeling subscale has a reliability of .61. The majority of studies were co

ducted on college-age students; thus, the evidence to support the tool’s utility applies m

to this group, and careful thought should be given when applying it to other individuals.

Keywordsn Myers-Briggs Type Indicatorn Personalityn Reliabilityn Validity

ISSN: 2745-2843 © Winston-Salem State University

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Validity and Reliability of the

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Ken Randall,1 PhD, MHR, PT; Mary Isaacson,1 EdD;

Carrie Ciro,1 PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

Author Affiliations:1Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Oklahoma Health

Sciences Center, Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Corresponding Author: Ken Randall, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, University

of Oklahoma Schusterman Center, 4502 East 41st Street, Room 2H20, Tulsa, OK 74135

(Ken-Randall@ouhsc.edu)

ABSTRACT

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is frequently used by health professions and educationa

programs to address the diversity of personalities that exist. No systematic review of the

ture or meta-analysis of its validity and reliability has occurred. This comprehensive liter

search identified 221 potential studies, of which seven met our inclusion criteria. Four of

studies examined construct validity, but their varying methods did not permit pooling fo

meta-analysis. These studies agree that the instrument has reasonable construct validity

three studies of test-retest reliability did allow a meta-analysis to be performed, albeit w

tion due to substantial heterogeneity. Results indicate that the Extravert-Introvert, Sens

Intuition, and Judging-Perceiving Subscales have satisfactory reliabilities of .75 or higher

that the Thinking-Feeling subscale has a reliability of .61. The majority of studies were co

ducted on college-age students; thus, the evidence to support the tool’s utility applies m

to this group, and careful thought should be given when applying it to other individuals.

Keywordsn Myers-Briggs Type Indicatorn Personalityn Reliabilityn Validity

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

INTRODUCTION

Personality is a commonly used term with a meaning that most of us readily comprehe

yet it is an elusive concept to fully describe or quantify. Broadly defined, it is the comb

of an individual’s cognitive, emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral response patterns (A

2009; McAdams, 2009). It has been studied since antiquity, with Hippocrates being am

the first to describe personality by grouping individuals into temperaments that relate

particular characteristics or types (Hippocrates 1923). Since then, countless theo

instruments have attempted to explicate and measure differences in personality more

Included in these instruments is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which is repo

to be one of the most widely used instruments in the world for understanding persona

differences (Briggs Myers, 1998; Jackson, Parker, & Dipboye, 1996; Lorr, 1991; Saggin

Kline, 1996; Salter, Evans, & Forney, 2006; Tzeng, Outcalt, Boyer, Ware, & Landis, 198

Zumbo & Taylor, 1993).

The MBTI is used extensively in human resource management and is one of the mo

commonly used instruments in higher education research and counseling (Hojat, Erdm

& Gonnella, 2013). Its application in medical education is quite varied and includes stu

of how certain preferences affect decision making (Pretz & Folse, 2011) and how know

of an individual’s type can enhance communication (Eksteen & Basson, 2015). Moreov

addressing the differences in type and preferences between instructors and students m

mize negative outcomes in both academic and clinical settings (Bell et al., 2011). In th

thors’ experience, we use the MBTI as both an educational and an academic adviseme

Our occupational therapy and physical therapy students learn about the 16 MBTI types

about how differing preferences can influence interactions with members of the health

team and with patients and their loved ones. We also provide academic advisors and c

instructors with information about individual student types that includes tips grounded

the MBTI literature on how to enhance their learning, communication, and feedback ba

on each student’s preference. Although we pay attention to the preferences of all stud

we also examine the preferences of learners from diverse backgrounds to determine i

trends exist in personality type. In an ongoing effort to use the best evidence to inform

educational program, we wanted to understand the psychometric properties of the MB

determine whether we should continue to use it with our students.

Since its inception in the 1940s, numerous studies have examined various aspects

MBTI, including many related to validity and reliability. Over the past 35 years, a numb

of relatively thorough reviews of the literature regarding these features of the MBTI ha

peared (Carlson, 1985; Carlyn, 1977; Gardner & Martinko, 1996; Murray, 1990; Pitteng

1993), including a compendium of research by the publishers of the tool itself (Thorne

Gough, 1999). However, none of these reviews was systematic in nature, nor did any a

INTRODUCTION

Personality is a commonly used term with a meaning that most of us readily comprehe

yet it is an elusive concept to fully describe or quantify. Broadly defined, it is the comb

of an individual’s cognitive, emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral response patterns (A

2009; McAdams, 2009). It has been studied since antiquity, with Hippocrates being am

the first to describe personality by grouping individuals into temperaments that relate

particular characteristics or types (Hippocrates 1923). Since then, countless theo

instruments have attempted to explicate and measure differences in personality more

Included in these instruments is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which is repo

to be one of the most widely used instruments in the world for understanding persona

differences (Briggs Myers, 1998; Jackson, Parker, & Dipboye, 1996; Lorr, 1991; Saggin

Kline, 1996; Salter, Evans, & Forney, 2006; Tzeng, Outcalt, Boyer, Ware, & Landis, 198

Zumbo & Taylor, 1993).

The MBTI is used extensively in human resource management and is one of the mo

commonly used instruments in higher education research and counseling (Hojat, Erdm

& Gonnella, 2013). Its application in medical education is quite varied and includes stu

of how certain preferences affect decision making (Pretz & Folse, 2011) and how know

of an individual’s type can enhance communication (Eksteen & Basson, 2015). Moreov

addressing the differences in type and preferences between instructors and students m

mize negative outcomes in both academic and clinical settings (Bell et al., 2011). In th

thors’ experience, we use the MBTI as both an educational and an academic adviseme

Our occupational therapy and physical therapy students learn about the 16 MBTI types

about how differing preferences can influence interactions with members of the health

team and with patients and their loved ones. We also provide academic advisors and c

instructors with information about individual student types that includes tips grounded

the MBTI literature on how to enhance their learning, communication, and feedback ba

on each student’s preference. Although we pay attention to the preferences of all stud

we also examine the preferences of learners from diverse backgrounds to determine i

trends exist in personality type. In an ongoing effort to use the best evidence to inform

educational program, we wanted to understand the psychometric properties of the MB

determine whether we should continue to use it with our students.

Since its inception in the 1940s, numerous studies have examined various aspects

MBTI, including many related to validity and reliability. Over the past 35 years, a numb

of relatively thorough reviews of the literature regarding these features of the MBTI ha

peared (Carlson, 1985; Carlyn, 1977; Gardner & Martinko, 1996; Murray, 1990; Pitteng

1993), including a compendium of research by the publishers of the tool itself (Thorne

Gough, 1999). However, none of these reviews was systematic in nature, nor did any a

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator 3

the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration (2016), considered the standard for comp

hensive literature searches (Sampson et al., 2006) and quality appraisal. In 2002, Cap

and Capraro conducted a meta-analytic reliability generalization study of articles inves

a number of the psychometric properties of the MBTI; however, the scope of the study

limited to articles published between 1998 and 2001. To date, we could find no compl

systematic review of the literature or in-depth meta-analysis of studies that meet the

suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration to assess the psychometric properties of the

THE MYERS BRIGGS TYPE INDICATOR

The MBTI measures the degree to which an individual prefers to operate from four dic

mous type pairs using a series of forced-choice questions that represent behavioral pr

ences. In accord with Jung’s theory of types, it proposes that everyone has a natural p

for one of the two opposites on each of four scales, emphasizing that one preference i

better than another. According to supporters of the MBTI, this distinguishes it from mo

psychological assessments, which quantify personality traits, many of which consider

of the scale to be more positive and the other more negative (Schaubhut, Herk, & Tho

2009, p. 4). The MBTI emphasizes the word preference and uses single letters of the a

to denote its eight preferences. The definitions for each MBTI preference show a distin

with Jung’s original definitions:

Extraversion (E) is the tendency to focus on the outer world of people and

external events. People who prefer extraversion direct their energy and at-

tention outward and receive energy from external events, experiences, and

interactions.

Introversion (I) is the preference to focus on the inner world of ideas and ex-

periences. Individuals direct their energy and attention inward and receive

energy from their internal thoughts, feelings, reflections, and time alone.

Sensing (S) is the preference to take information in through the eyes, ears,

and other senses. People who are predominantly sensing are observant of

what is going on around them and are especially good at recognizing the

practical realities of a situation.

Intuition (N) is the ability to take in information by seeing the big picture,

focusing on relationships and connections between facts. People who prefer

intuition tend to grasp patterns and are especially adept at seeing new pos-

sibilities and different perspectives.

the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration (2016), considered the standard for comp

hensive literature searches (Sampson et al., 2006) and quality appraisal. In 2002, Cap

and Capraro conducted a meta-analytic reliability generalization study of articles inves

a number of the psychometric properties of the MBTI; however, the scope of the study

limited to articles published between 1998 and 2001. To date, we could find no compl

systematic review of the literature or in-depth meta-analysis of studies that meet the

suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration to assess the psychometric properties of the

THE MYERS BRIGGS TYPE INDICATOR

The MBTI measures the degree to which an individual prefers to operate from four dic

mous type pairs using a series of forced-choice questions that represent behavioral pr

ences. In accord with Jung’s theory of types, it proposes that everyone has a natural p

for one of the two opposites on each of four scales, emphasizing that one preference i

better than another. According to supporters of the MBTI, this distinguishes it from mo

psychological assessments, which quantify personality traits, many of which consider

of the scale to be more positive and the other more negative (Schaubhut, Herk, & Tho

2009, p. 4). The MBTI emphasizes the word preference and uses single letters of the a

to denote its eight preferences. The definitions for each MBTI preference show a distin

with Jung’s original definitions:

Extraversion (E) is the tendency to focus on the outer world of people and

external events. People who prefer extraversion direct their energy and at-

tention outward and receive energy from external events, experiences, and

interactions.

Introversion (I) is the preference to focus on the inner world of ideas and ex-

periences. Individuals direct their energy and attention inward and receive

energy from their internal thoughts, feelings, reflections, and time alone.

Sensing (S) is the preference to take information in through the eyes, ears,

and other senses. People who are predominantly sensing are observant of

what is going on around them and are especially good at recognizing the

practical realities of a situation.

Intuition (N) is the ability to take in information by seeing the big picture,

focusing on relationships and connections between facts. People who prefer

intuition tend to grasp patterns and are especially adept at seeing new pos-

sibilities and different perspectives.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

Thinking (T) is the preference in decision making to look at the logical con-

sequences of a choice or action. People who prefer this type try to mentally

remove themselves from a situation to examine it objectively and analyze

cause and effect.

Feeling (F) is the use of emotion in decision making, and people with this

preference tend to consider what is important to them and to other people.

They mentally place themselves in a situation and identify with the people

involved so that they can make decisions based on person-centered values.

Judging (J) is the preference to organize life in a planned, orderly way, with

a desire to regulate and control it. People who prefer judging make deci-

sions, achieve closure, and appreciate an environment that is structured

and organized.

Perceiving (P) is the tendency to live in a flexible, spontaneous way, seeking

to experience and understand life rather than control it. People who are

perceiving prefer to be open to experience and last-minute options. They

enjoy and trust their resourcefulness and ability to adapt to the demands of

a situation (Briggs-Myers, 1993; Hall & Nordby, 1973).

The MBTI treats each preference equally, so there are no principal functions or sub

ordinate functions as described by Jung. Given four sets of dichotomous preferences th

can occur in any combination, the MBTI proposes that there are sixteen different perso

types. With the MBTI, four letters represent each type, which indicate the four domina

preference areas. For example, ENFP is Extraversion Intuitive Feeling Perceiving, whic

its own set of characteristics, some like and some different from the other fifteen type

lar to Jung’s work in Psychological Types (1923), the MBTI addresses various combinat

each type, such as introverted-sensing or intuitive-thinking-perceiving. The MBTI allow

user to describe two people with the exact four-letter combination of preferences in ge

ties similar to both, yet accounts for the individual differences produced by variation o

extent (or strength) of each person’s preference. This echoes Jung’s belief that his typ

be used to describe groups of people as well as individuals (Jung, 1921/1923).

According to the companion manual to the MBTI, Introduction to Type (Briggs Myer

1998; Myers, Kirby, & Briggs Meyers, 2015), which was first published in 1970 and is c

in its seventh edition, the goal of the instrument is to foster self-understanding, enhan

learning and communication, assist with conflict management, and enhance relationsh

is a tool “with intent not to stereotype, but to allow understanding of individual prefere

(Jessup, 2002, p. 503). Between 1943 and 1975, the MBTI evolved through a number o

tions, spanning Forms A through F. In 1975 Consulting Psychologist Press acquired the

Thinking (T) is the preference in decision making to look at the logical con-

sequences of a choice or action. People who prefer this type try to mentally

remove themselves from a situation to examine it objectively and analyze

cause and effect.

Feeling (F) is the use of emotion in decision making, and people with this

preference tend to consider what is important to them and to other people.

They mentally place themselves in a situation and identify with the people

involved so that they can make decisions based on person-centered values.

Judging (J) is the preference to organize life in a planned, orderly way, with

a desire to regulate and control it. People who prefer judging make deci-

sions, achieve closure, and appreciate an environment that is structured

and organized.

Perceiving (P) is the tendency to live in a flexible, spontaneous way, seeking

to experience and understand life rather than control it. People who are

perceiving prefer to be open to experience and last-minute options. They

enjoy and trust their resourcefulness and ability to adapt to the demands of

a situation (Briggs-Myers, 1993; Hall & Nordby, 1973).

The MBTI treats each preference equally, so there are no principal functions or sub

ordinate functions as described by Jung. Given four sets of dichotomous preferences th

can occur in any combination, the MBTI proposes that there are sixteen different perso

types. With the MBTI, four letters represent each type, which indicate the four domina

preference areas. For example, ENFP is Extraversion Intuitive Feeling Perceiving, whic

its own set of characteristics, some like and some different from the other fifteen type

lar to Jung’s work in Psychological Types (1923), the MBTI addresses various combinat

each type, such as introverted-sensing or intuitive-thinking-perceiving. The MBTI allow

user to describe two people with the exact four-letter combination of preferences in ge

ties similar to both, yet accounts for the individual differences produced by variation o

extent (or strength) of each person’s preference. This echoes Jung’s belief that his typ

be used to describe groups of people as well as individuals (Jung, 1921/1923).

According to the companion manual to the MBTI, Introduction to Type (Briggs Myer

1998; Myers, Kirby, & Briggs Meyers, 2015), which was first published in 1970 and is c

in its seventh edition, the goal of the instrument is to foster self-understanding, enhan

learning and communication, assist with conflict management, and enhance relationsh

is a tool “with intent not to stereotype, but to allow understanding of individual prefere

(Jessup, 2002, p. 503). Between 1943 and 1975, the MBTI evolved through a number o

tions, spanning Forms A through F. In 1975 Consulting Psychologist Press acquired the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator 5

to sell the MBTI as a proprietary instrument (Pittenger, 1993), and it became readily a

for widespread use as Form G (McCaulley, 1990). In 1998, Form G underwent revision

was published as Form M, which can be administered by the publisher, by computer, o

using a self-scorable version. Additionally, two MBTI instruments that explore type mo

deeply are the Step II (first published as Form K in 1989 and subsequently revised as F

in 2001) and Step III (published in 2009). Step II explores differences within the same

and Step III is administered only by counselors specifically trained in the tool in one-on

sessions (Myers, McCaulley, Quenk, & Mitchell, 2009). There are currently four distinct

forms of the MBTI, each differing in its use and scoring: Form M and Form M self-scora

Step II Form Q, and Step III. The MBTI has a European version and has been translated

21 languages, including Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, and Spanish (

& Briggs Foundation, 2016).

Most criticisms of the MBTI relate to the dichotomous nature of the instrument, its

translation of continuous scale scores into nominal categories of preference, and whet

reflects the theory on which it is based (Barbuto, 1997; Daisly, 2011; Pittenger, 1993;

1992). The forced-choice nature of the MBTI does not allow respondents to select a me

or neutral response (Barbuto, 1997); they must choose a response that places them in

preference or the other (either Extraversion or Introversion, Sensing or iNtuition, Think

or Feeling, Judging or Perceiving). Scoring for the MBTI reflects the most frequently se

side of the four dichotomies, which determines preference, reflected in the four-letter

bination that expresses overall type. Barbuto (1997) suggests that this nominal

the MBTI results deviates from Jung’s original theory. These observations lead to ques

regarding the validity and reliability of the MBTI (Zemke, 1992).

Key properties of an assessment tool such as the MBTI are validity and reliability. T

relate to aspects of its construction, evaluation, and documentation as described by th

dards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Asso

tion, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Educa

tion, 2014). Validity is the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpreta

of scores for the proposed uses of the test. Construct validity refers to the extent to w

actually measures what the theory says it does. Reliability is the degree to which scor

individual or group are consistent over repeated administrations of the same test. Tes

reliability assesses the degree to which test scores are consistent from one test admin

to the next. Internal consistency reliability assesses the stability of results across item

test (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association,

National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014, chaps. 1, 2).

At present, no complete study has investigated the breadth of articles published ab

the MBTI or performed an in-depth analysis of the psychometric properties of the instr

ment as a whole or its various forms. This systematic review/meta-analysis seeks to in

our research question: in the adult population, is the MBTI a useful test in terms of con

to sell the MBTI as a proprietary instrument (Pittenger, 1993), and it became readily a

for widespread use as Form G (McCaulley, 1990). In 1998, Form G underwent revision

was published as Form M, which can be administered by the publisher, by computer, o

using a self-scorable version. Additionally, two MBTI instruments that explore type mo

deeply are the Step II (first published as Form K in 1989 and subsequently revised as F

in 2001) and Step III (published in 2009). Step II explores differences within the same

and Step III is administered only by counselors specifically trained in the tool in one-on

sessions (Myers, McCaulley, Quenk, & Mitchell, 2009). There are currently four distinct

forms of the MBTI, each differing in its use and scoring: Form M and Form M self-scora

Step II Form Q, and Step III. The MBTI has a European version and has been translated

21 languages, including Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, and Spanish (

& Briggs Foundation, 2016).

Most criticisms of the MBTI relate to the dichotomous nature of the instrument, its

translation of continuous scale scores into nominal categories of preference, and whet

reflects the theory on which it is based (Barbuto, 1997; Daisly, 2011; Pittenger, 1993;

1992). The forced-choice nature of the MBTI does not allow respondents to select a me

or neutral response (Barbuto, 1997); they must choose a response that places them in

preference or the other (either Extraversion or Introversion, Sensing or iNtuition, Think

or Feeling, Judging or Perceiving). Scoring for the MBTI reflects the most frequently se

side of the four dichotomies, which determines preference, reflected in the four-letter

bination that expresses overall type. Barbuto (1997) suggests that this nominal

the MBTI results deviates from Jung’s original theory. These observations lead to ques

regarding the validity and reliability of the MBTI (Zemke, 1992).

Key properties of an assessment tool such as the MBTI are validity and reliability. T

relate to aspects of its construction, evaluation, and documentation as described by th

dards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Asso

tion, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Educa

tion, 2014). Validity is the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpreta

of scores for the proposed uses of the test. Construct validity refers to the extent to w

actually measures what the theory says it does. Reliability is the degree to which scor

individual or group are consistent over repeated administrations of the same test. Tes

reliability assesses the degree to which test scores are consistent from one test admin

to the next. Internal consistency reliability assesses the stability of results across item

test (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association,

National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014, chaps. 1, 2).

At present, no complete study has investigated the breadth of articles published ab

the MBTI or performed an in-depth analysis of the psychometric properties of the instr

ment as a whole or its various forms. This systematic review/meta-analysis seeks to in

our research question: in the adult population, is the MBTI a useful test in terms of con

6 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

validity, test-retest reliability, and/or internal consistency reliability in determining per

ity preference in the areas of inward or outward focus (extraversion/introversion), info

tion processing (sensing/intuition), decision making (thinking/feeling), and organiz

(judging/perceiving)?

METHODS

Rationale for Methods

This systematic review of the key psychometric properties of the MBTI adhered

Cochrane guidelines and consisted of a priori identification of inclusion criteria,

determined our search strategy, followed by a two-phase process of critical appraisal o

cluded studies with the intent to extract data for analysis. Inclusion criteria for this rev

incorporated the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (Cochrane Collaboration Diagnosti

Test Accuracy Working Group 2011; Deeks, Wisniewski, & Davenport, 2013; Higgins et

2011) and contained questions extracted from its tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgin

man, 2008), as well as strategies for systematic reviews proposed by Meline (2006) an

(1986). Some Cochrane criteria, such as those pertaining to randomized controlled tria

multiple-group designs, were not applicable and thus not used. Other recommended c

were incorporated into the rubric we applied to assess each article’s quality.

Inclusion Criteria and Rationale

The inclusion criteria for studies in this systematic review/meta-analysis were as follow

• The study was consistent with the research question.

• The study examined construct validity, test-retest reliability, and/or internal

consistency reliability for the MBTI as new data.

• Subjects in the study were adults (18 years or older).

• The study was written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal

in 1975 or later, or the study was a dissertation written in English and pub-

lished in 2011 or later.

• Sample size and level of significance were reported or were obtainable from

study authors.

• The study authors expressed data for reliability as alpha coefficients, item-

total correlations, corrected item-total correlations, intraclass correlation

(ICC) coefficients, Pearson correlation coefficients, Spearman rank correla-

tion coefficients, or kappa coefficients; and/or expressed data for validity

as structural equation modeling, alpha coefficients, item-total correlations,

validity, test-retest reliability, and/or internal consistency reliability in determining per

ity preference in the areas of inward or outward focus (extraversion/introversion), info

tion processing (sensing/intuition), decision making (thinking/feeling), and organiz

(judging/perceiving)?

METHODS

Rationale for Methods

This systematic review of the key psychometric properties of the MBTI adhered

Cochrane guidelines and consisted of a priori identification of inclusion criteria,

determined our search strategy, followed by a two-phase process of critical appraisal o

cluded studies with the intent to extract data for analysis. Inclusion criteria for this rev

incorporated the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (Cochrane Collaboration Diagnosti

Test Accuracy Working Group 2011; Deeks, Wisniewski, & Davenport, 2013; Higgins et

2011) and contained questions extracted from its tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgin

man, 2008), as well as strategies for systematic reviews proposed by Meline (2006) an

(1986). Some Cochrane criteria, such as those pertaining to randomized controlled tria

multiple-group designs, were not applicable and thus not used. Other recommended c

were incorporated into the rubric we applied to assess each article’s quality.

Inclusion Criteria and Rationale

The inclusion criteria for studies in this systematic review/meta-analysis were as follow

• The study was consistent with the research question.

• The study examined construct validity, test-retest reliability, and/or internal

consistency reliability for the MBTI as new data.

• Subjects in the study were adults (18 years or older).

• The study was written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal

in 1975 or later, or the study was a dissertation written in English and pub-

lished in 2011 or later.

• Sample size and level of significance were reported or were obtainable from

study authors.

• The study authors expressed data for reliability as alpha coefficients, item-

total correlations, corrected item-total correlations, intraclass correlation

(ICC) coefficients, Pearson correlation coefficients, Spearman rank correla-

tion coefficients, or kappa coefficients; and/or expressed data for validity

as structural equation modeling, alpha coefficients, item-total correlations,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator 7

corrected-item total correlations, ICCs, Pearson r, Spearman r, kappa, or

item-level ICCs or factor analysis.

The publication date of 1975 or later was selected based on the assertion by McCa

ley (1990) that in 1975 the MBTI was readily accessible for use. We elected to study a

the three forms of the MBTI (Form F, G, or M) that were in use from 1975 to the presen

day, since they all measure the same theoretical construct and are simply refinements

instrument. We did not use any articles related to the MBTI Step II or Step III instrume

because these are different versions of the MBTI that are scored only through the pub

or by a certified MBTI counselor, and more pragmatically, no studies were found when

conducted our literature search. Given the potential time lapse between completing a

sertation and submitting it for publication, we selected five years as sufficient time to

dissertation that was completed longer than five years ago likely will not have been ac

for publication due to failure to meet certain quality thresholds (Meline, 2006). If a stu

not report its level of significance (alpha) and we could not confirm it with study autho

excluded it from analysis.

Search Strategy

The comprehensive literature search was conducted by a librarian with a master of lib

information science degree and who is a distinguished member of the Academy of Hea

Information. Databases searched were Ovid MEDLINE®, OVID OLDMEDLINE®, OVID

MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID MEDLINE® Without Re-

visions, EMBASE+EMBASE CLASSIC, ERIC, PsycINFO, and HEALTH AND PSYCHO-

SOCIAL INSTRUMENTS (HAPI). Search terms used were Myers-Briggs, validity, reliabilit

and statistics. Results were limited to articles published in 1975 or later on adult popu

(older than 18 years). When possible, MeSH terms and descriptors were used and exp

Truncation was employed for a maximum number of results. Reference results from ea

database were reviewed, and the authors examined reference lists of individual article

ditional studies. A hand search was conducted on numerous compendiums of psychom

assessment and measurement for additional studies. The literature search produced 2

tential studies, which were assembled into the EndNote (Clarivate Analytics 2014) refe

management software system.

Study Selection Process

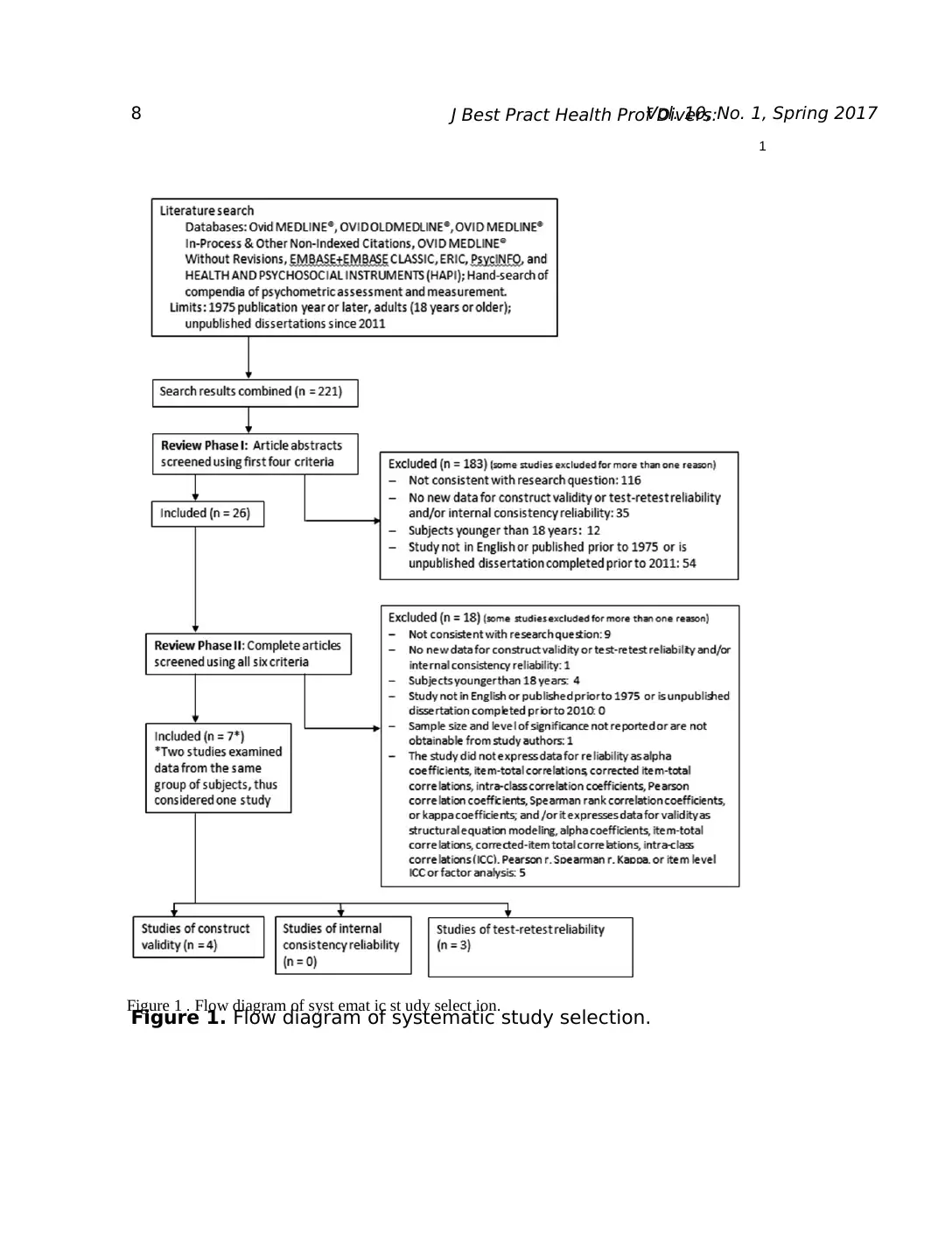

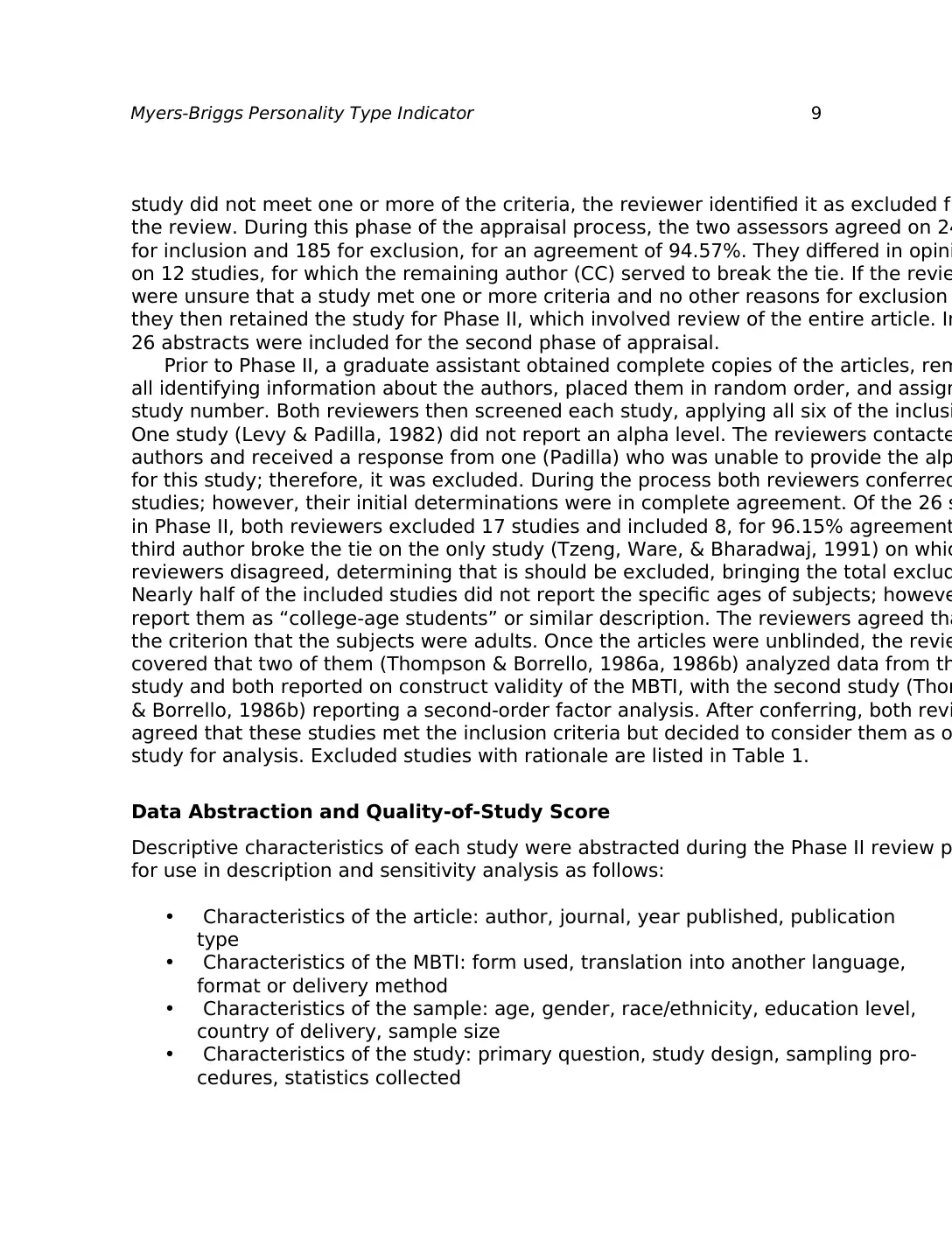

The application of this study’s inclusion criteria occurred in two phases, depicted in the

diagram of Figure 1. Phase I involved independent and blinded assessments of the ass

abstracts by two of the authors (MI and KR), applying the first four inclusion criteria. If

corrected-item total correlations, ICCs, Pearson r, Spearman r, kappa, or

item-level ICCs or factor analysis.

The publication date of 1975 or later was selected based on the assertion by McCa

ley (1990) that in 1975 the MBTI was readily accessible for use. We elected to study a

the three forms of the MBTI (Form F, G, or M) that were in use from 1975 to the presen

day, since they all measure the same theoretical construct and are simply refinements

instrument. We did not use any articles related to the MBTI Step II or Step III instrume

because these are different versions of the MBTI that are scored only through the pub

or by a certified MBTI counselor, and more pragmatically, no studies were found when

conducted our literature search. Given the potential time lapse between completing a

sertation and submitting it for publication, we selected five years as sufficient time to

dissertation that was completed longer than five years ago likely will not have been ac

for publication due to failure to meet certain quality thresholds (Meline, 2006). If a stu

not report its level of significance (alpha) and we could not confirm it with study autho

excluded it from analysis.

Search Strategy

The comprehensive literature search was conducted by a librarian with a master of lib

information science degree and who is a distinguished member of the Academy of Hea

Information. Databases searched were Ovid MEDLINE®, OVID OLDMEDLINE®, OVID

MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID MEDLINE® Without Re-

visions, EMBASE+EMBASE CLASSIC, ERIC, PsycINFO, and HEALTH AND PSYCHO-

SOCIAL INSTRUMENTS (HAPI). Search terms used were Myers-Briggs, validity, reliabilit

and statistics. Results were limited to articles published in 1975 or later on adult popu

(older than 18 years). When possible, MeSH terms and descriptors were used and exp

Truncation was employed for a maximum number of results. Reference results from ea

database were reviewed, and the authors examined reference lists of individual article

ditional studies. A hand search was conducted on numerous compendiums of psychom

assessment and measurement for additional studies. The literature search produced 2

tential studies, which were assembled into the EndNote (Clarivate Analytics 2014) refe

management software system.

Study Selection Process

The application of this study’s inclusion criteria occurred in two phases, depicted in the

diagram of Figure 1. Phase I involved independent and blinded assessments of the ass

abstracts by two of the authors (MI and KR), applying the first four inclusion criteria. If

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

Figure 1. Flow diagram of systematic study selection.

1

Figure 1 . Flow diagram of syst emat ic st udy select ion.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of systematic study selection.

1

Figure 1 . Flow diagram of syst emat ic st udy select ion.

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator 9

study did not meet one or more of the criteria, the reviewer identified it as excluded fr

the review. During this phase of the appraisal process, the two assessors agreed on 24

for inclusion and 185 for exclusion, for an agreement of 94.57%. They differed in opini

on 12 studies, for which the remaining author (CC) served to break the tie. If the revie

were unsure that a study met one or more criteria and no other reasons for exclusion

they then retained the study for Phase II, which involved review of the entire article. In

26 abstracts were included for the second phase of appraisal.

Prior to Phase II, a graduate assistant obtained complete copies of the articles, rem

all identifying information about the authors, placed them in random order, and assign

study number. Both reviewers then screened each study, applying all six of the inclusi

One study (Levy & Padilla, 1982) did not report an alpha level. The reviewers contacte

authors and received a response from one (Padilla) who was unable to provide the alp

for this study; therefore, it was excluded. During the process both reviewers conferred

studies; however, their initial determinations were in complete agreement. Of the 26 s

in Phase II, both reviewers excluded 17 studies and included 8, for 96.15% agreement

third author broke the tie on the only study (Tzeng, Ware, & Bharadwaj, 1991) on whic

reviewers disagreed, determining that is should be excluded, bringing the total exclud

Nearly half of the included studies did not report the specific ages of subjects; howeve

report them as “college-age students” or similar description. The reviewers agreed tha

the criterion that the subjects were adults. Once the articles were unblinded, the revie

covered that two of them (Thompson & Borrello, 1986a, 1986b) analyzed data from th

study and both reported on construct validity of the MBTI, with the second study (Thom

& Borrello, 1986b) reporting a second-order factor analysis. After conferring, both revi

agreed that these studies met the inclusion criteria but decided to consider them as o

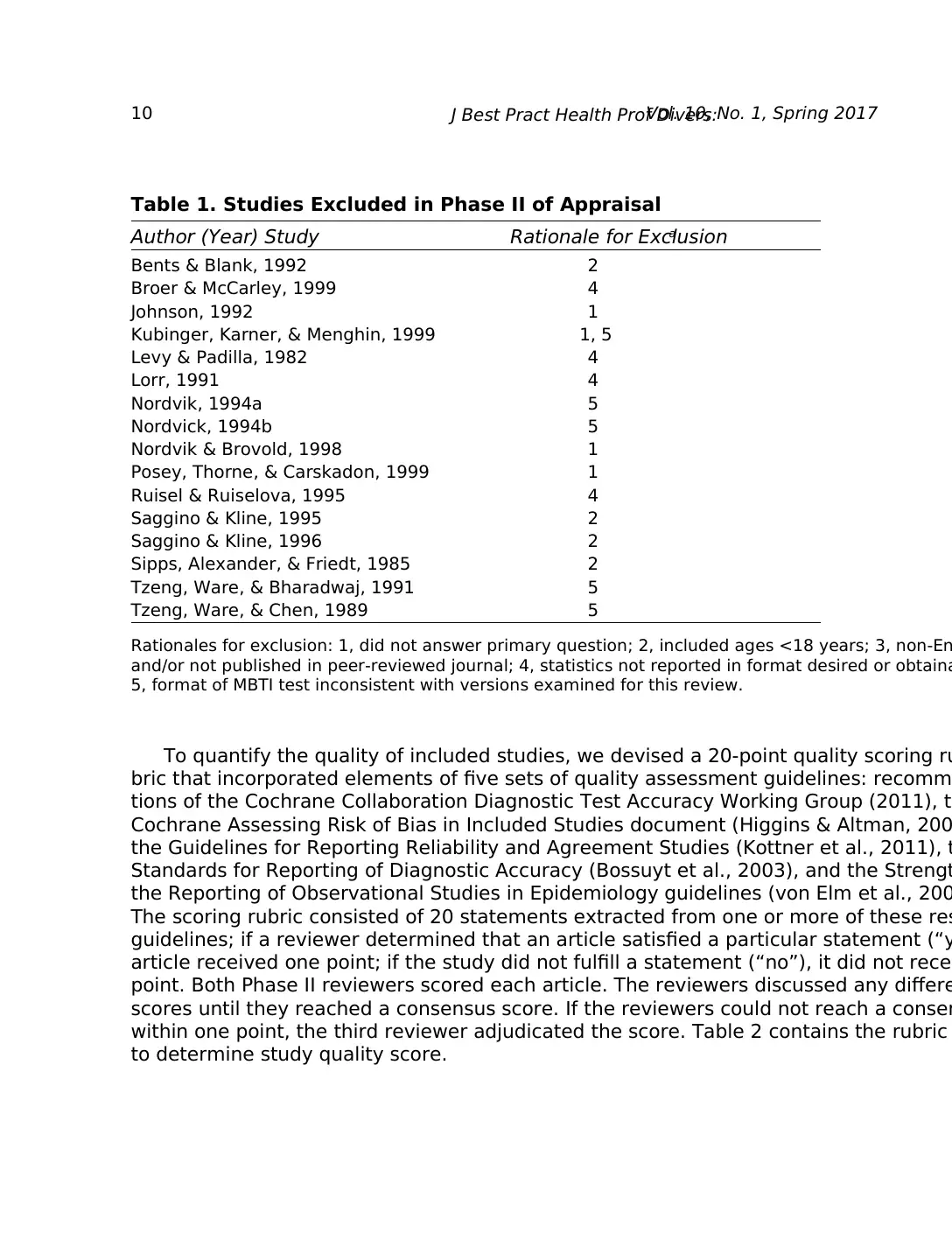

study for analysis. Excluded studies with rationale are listed in Table 1.

Data Abstraction and Quality-of-Study Score

Descriptive characteristics of each study were abstracted during the Phase II review p

for use in description and sensitivity analysis as follows:

• Characteristics of the article: author, journal, year published, publication

type

• Characteristics of the MBTI: form used, translation into another language,

format or delivery method

• Characteristics of the sample: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level,

country of delivery, sample size

• Characteristics of the study: primary question, study design, sampling pro-

cedures, statistics collected

study did not meet one or more of the criteria, the reviewer identified it as excluded fr

the review. During this phase of the appraisal process, the two assessors agreed on 24

for inclusion and 185 for exclusion, for an agreement of 94.57%. They differed in opini

on 12 studies, for which the remaining author (CC) served to break the tie. If the revie

were unsure that a study met one or more criteria and no other reasons for exclusion

they then retained the study for Phase II, which involved review of the entire article. In

26 abstracts were included for the second phase of appraisal.

Prior to Phase II, a graduate assistant obtained complete copies of the articles, rem

all identifying information about the authors, placed them in random order, and assign

study number. Both reviewers then screened each study, applying all six of the inclusi

One study (Levy & Padilla, 1982) did not report an alpha level. The reviewers contacte

authors and received a response from one (Padilla) who was unable to provide the alp

for this study; therefore, it was excluded. During the process both reviewers conferred

studies; however, their initial determinations were in complete agreement. Of the 26 s

in Phase II, both reviewers excluded 17 studies and included 8, for 96.15% agreement

third author broke the tie on the only study (Tzeng, Ware, & Bharadwaj, 1991) on whic

reviewers disagreed, determining that is should be excluded, bringing the total exclud

Nearly half of the included studies did not report the specific ages of subjects; howeve

report them as “college-age students” or similar description. The reviewers agreed tha

the criterion that the subjects were adults. Once the articles were unblinded, the revie

covered that two of them (Thompson & Borrello, 1986a, 1986b) analyzed data from th

study and both reported on construct validity of the MBTI, with the second study (Thom

& Borrello, 1986b) reporting a second-order factor analysis. After conferring, both revi

agreed that these studies met the inclusion criteria but decided to consider them as o

study for analysis. Excluded studies with rationale are listed in Table 1.

Data Abstraction and Quality-of-Study Score

Descriptive characteristics of each study were abstracted during the Phase II review p

for use in description and sensitivity analysis as follows:

• Characteristics of the article: author, journal, year published, publication

type

• Characteristics of the MBTI: form used, translation into another language,

format or delivery method

• Characteristics of the sample: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level,

country of delivery, sample size

• Characteristics of the study: primary question, study design, sampling pro-

cedures, statistics collected

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

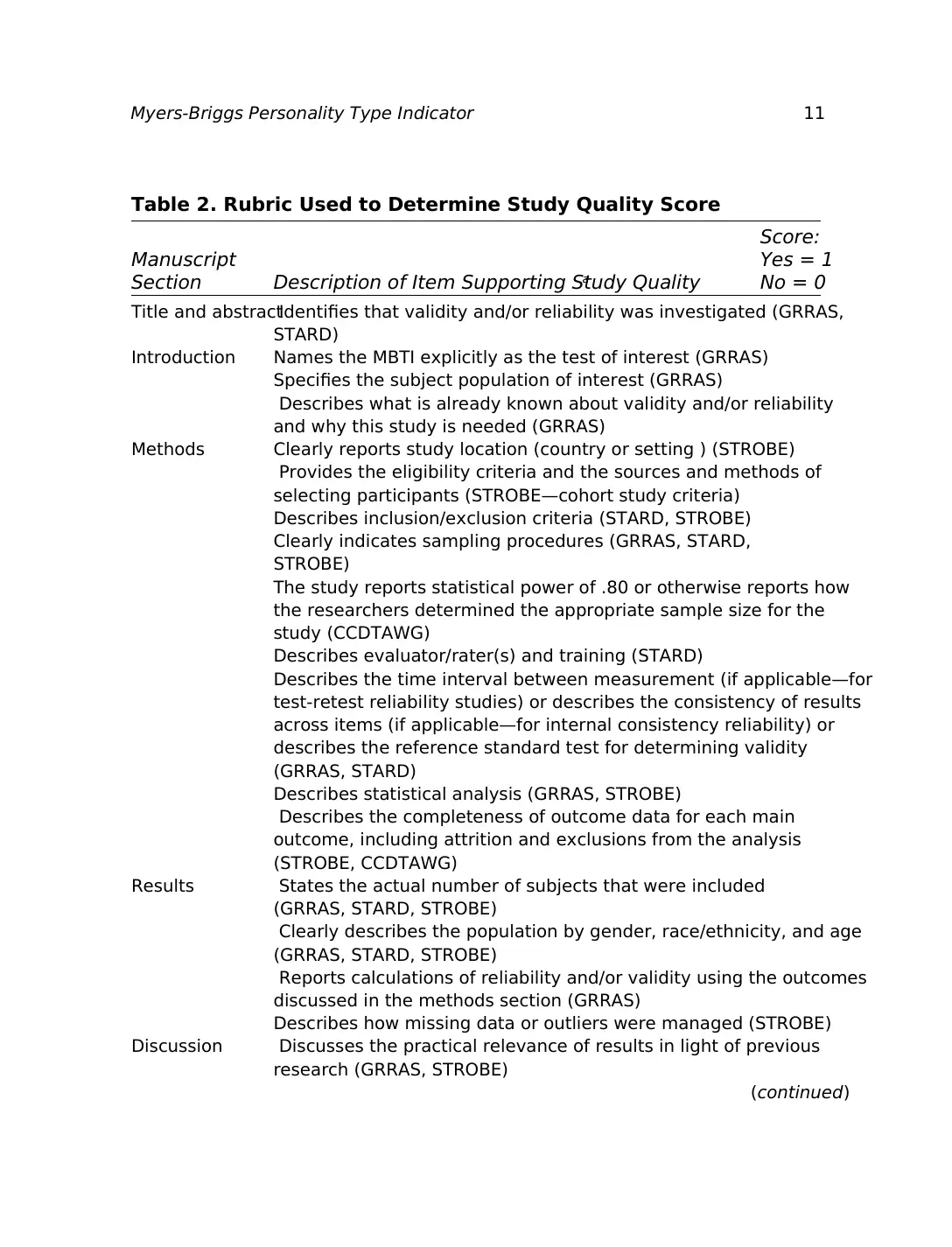

To quantify the quality of included studies, we devised a 20-point quality scoring ru

bric that incorporated elements of five sets of quality assessment guidelines: recomm

tions of the Cochrane Collaboration Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group (2011), th

Cochrane Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies document (Higgins & Altman, 200

the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (Kottner et al., 2011), t

Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (Bossuyt et al., 2003), and the Strengt

the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (von Elm et al., 200

The scoring rubric consisted of 20 statements extracted from one or more of these res

guidelines; if a reviewer determined that an article satisfied a particular statement (“y

article received one point; if the study did not fulfill a statement (“no”), it did not recei

point. Both Phase II reviewers scored each article. The reviewers discussed any differe

scores until they reached a consensus score. If the reviewers could not reach a consen

within one point, the third reviewer adjudicated the score. Table 2 contains the rubric

to determine study quality score.

Table 1. Studies Excluded in Phase II of Appraisal

Author (Year) Study Rationale for Exclusiona

Bents & Blank, 1992 2

Broer & McCarley, 1999 4

Johnson, 1992 1

Kubinger, Karner, & Menghin, 1999 1, 5

Levy & Padilla, 1982 4

Lorr, 1991 4

Nordvik, 1994a 5

Nordvick, 1994b 5

Nordvik & Brovold, 1998 1

Posey, Thorne, & Carskadon, 1999 1

Ruisel & Ruiselova, 1995 4

Saggino & Kline, 1995 2

Saggino & Kline, 1996 2

Sipps, Alexander, & Friedt, 1985 2

Tzeng, Ware, & Bharadwaj, 1991 5

Tzeng, Ware, & Chen, 1989 5

Rationales for exclusion: 1, did not answer primary question; 2, included ages <18 years; 3, non-En

and/or not published in peer-reviewed journal; 4, statistics not reported in format desired or obtaina

5, format of MBTI test inconsistent with versions examined for this review.

To quantify the quality of included studies, we devised a 20-point quality scoring ru

bric that incorporated elements of five sets of quality assessment guidelines: recomm

tions of the Cochrane Collaboration Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group (2011), th

Cochrane Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies document (Higgins & Altman, 200

the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (Kottner et al., 2011), t

Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (Bossuyt et al., 2003), and the Strengt

the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (von Elm et al., 200

The scoring rubric consisted of 20 statements extracted from one or more of these res

guidelines; if a reviewer determined that an article satisfied a particular statement (“y

article received one point; if the study did not fulfill a statement (“no”), it did not recei

point. Both Phase II reviewers scored each article. The reviewers discussed any differe

scores until they reached a consensus score. If the reviewers could not reach a consen

within one point, the third reviewer adjudicated the score. Table 2 contains the rubric

to determine study quality score.

Table 1. Studies Excluded in Phase II of Appraisal

Author (Year) Study Rationale for Exclusiona

Bents & Blank, 1992 2

Broer & McCarley, 1999 4

Johnson, 1992 1

Kubinger, Karner, & Menghin, 1999 1, 5

Levy & Padilla, 1982 4

Lorr, 1991 4

Nordvik, 1994a 5

Nordvick, 1994b 5

Nordvik & Brovold, 1998 1

Posey, Thorne, & Carskadon, 1999 1

Ruisel & Ruiselova, 1995 4

Saggino & Kline, 1995 2

Saggino & Kline, 1996 2

Sipps, Alexander, & Friedt, 1985 2

Tzeng, Ware, & Bharadwaj, 1991 5

Tzeng, Ware, & Chen, 1989 5

Rationales for exclusion: 1, did not answer primary question; 2, included ages <18 years; 3, non-En

and/or not published in peer-reviewed journal; 4, statistics not reported in format desired or obtaina

5, format of MBTI test inconsistent with versions examined for this review.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator 11

Table 2. Rubric Used to Determine Study Quality Score

Score:

Manuscript Yes = 1

Section Description of Item Supporting Study Qualitya No = 0

Title and abstractIdentifies that validity and/or reliability was investigated (GRRAS,

STARD)

Introduction Names the MBTI explicitly as the test of interest (GRRAS)

Specifies the subject population of interest (GRRAS)

Describes what is already known about validity and/or reliability

and why this study is needed (GRRAS)

Methods Clearly reports study location (country or setting ) (STROBE)

Provides the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of

selecting participants (STROBE—cohort study criteria)

Describes inclusion/exclusion criteria (STARD, STROBE)

Clearly indicates sampling procedures (GRRAS, STARD,

STROBE)

The study reports statistical power of .80 or otherwise reports how

the researchers determined the appropriate sample size for the

study (CCDTAWG)

Describes evaluator/rater(s) and training (STARD)

Describes the time interval between measurement (if applicable—for

test-retest reliability studies) or describes the consistency of results

across items (if applicable—for internal consistency reliability) or

describes the reference standard test for determining validity

(GRRAS, STARD)

Describes statistical analysis (GRRAS, STROBE)

Describes the completeness of outcome data for each main

outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis

(STROBE, CCDTAWG)

Results States the actual number of subjects that were included

(GRRAS, STARD, STROBE)

Clearly describes the population by gender, race/ethnicity, and age

(GRRAS, STARD, STROBE)

Reports calculations of reliability and/or validity using the outcomes

discussed in the methods section (GRRAS)

Describes how missing data or outliers were managed (STROBE)

Discussion Discusses the practical relevance of results in light of previous

research (GRRAS, STROBE)

(continued)

Table 2. Rubric Used to Determine Study Quality Score

Score:

Manuscript Yes = 1

Section Description of Item Supporting Study Qualitya No = 0

Title and abstractIdentifies that validity and/or reliability was investigated (GRRAS,

STARD)

Introduction Names the MBTI explicitly as the test of interest (GRRAS)

Specifies the subject population of interest (GRRAS)

Describes what is already known about validity and/or reliability

and why this study is needed (GRRAS)

Methods Clearly reports study location (country or setting ) (STROBE)

Provides the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of

selecting participants (STROBE—cohort study criteria)

Describes inclusion/exclusion criteria (STARD, STROBE)

Clearly indicates sampling procedures (GRRAS, STARD,

STROBE)

The study reports statistical power of .80 or otherwise reports how

the researchers determined the appropriate sample size for the

study (CCDTAWG)

Describes evaluator/rater(s) and training (STARD)

Describes the time interval between measurement (if applicable—for

test-retest reliability studies) or describes the consistency of results

across items (if applicable—for internal consistency reliability) or

describes the reference standard test for determining validity

(GRRAS, STARD)

Describes statistical analysis (GRRAS, STROBE)

Describes the completeness of outcome data for each main

outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis

(STROBE, CCDTAWG)

Results States the actual number of subjects that were included

(GRRAS, STARD, STROBE)

Clearly describes the population by gender, race/ethnicity, and age

(GRRAS, STARD, STROBE)

Reports calculations of reliability and/or validity using the outcomes

discussed in the methods section (GRRAS)

Describes how missing data or outliers were managed (STROBE)

Discussion Discusses the practical relevance of results in light of previous

research (GRRAS, STROBE)

(continued)

12 J Best Pract Health Prof Divers:Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2017

Data Analysis

We conducted a preliminary analysis of the data using MedCalc statistical software (M

Software 2016) to calculate I2 and Cochran’s Q to assess for heterogeneity. The literature var

ies on exactly how many studies are required to effectively conduct a meta-analysis. W

studies are statistically homogeneous, they can be viewed from a fixed-effects

and subjects from as few as two studies can be pooled for meta-analysis (Borenstein,

Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Field & Gillett, 2010). The alternative, using a random-effe

approach in which some variability of studies is assumed, is appropriate only for studie

which the variability is reasonable. As the heterogeneity of the effects of multiple stud

increases, the appropriateness for pooling the data decreases (Higgins & Green, 2011

RESULTS

Included Studies

The seven studies that met our inclusion criteria are listed in chronological order in Ta

which includes the MBTI form and psychometric property studied, number of subjects

fied by gender (if reported), demographic information provided, and the reviewers’ co

quality ranking based on the 20-point scale developed a priori. Only validity and reliab

studies involving Forms F and G of the MBTI were included in this systematic review; n

studies of the most current form (Form M) were among those that remained after the

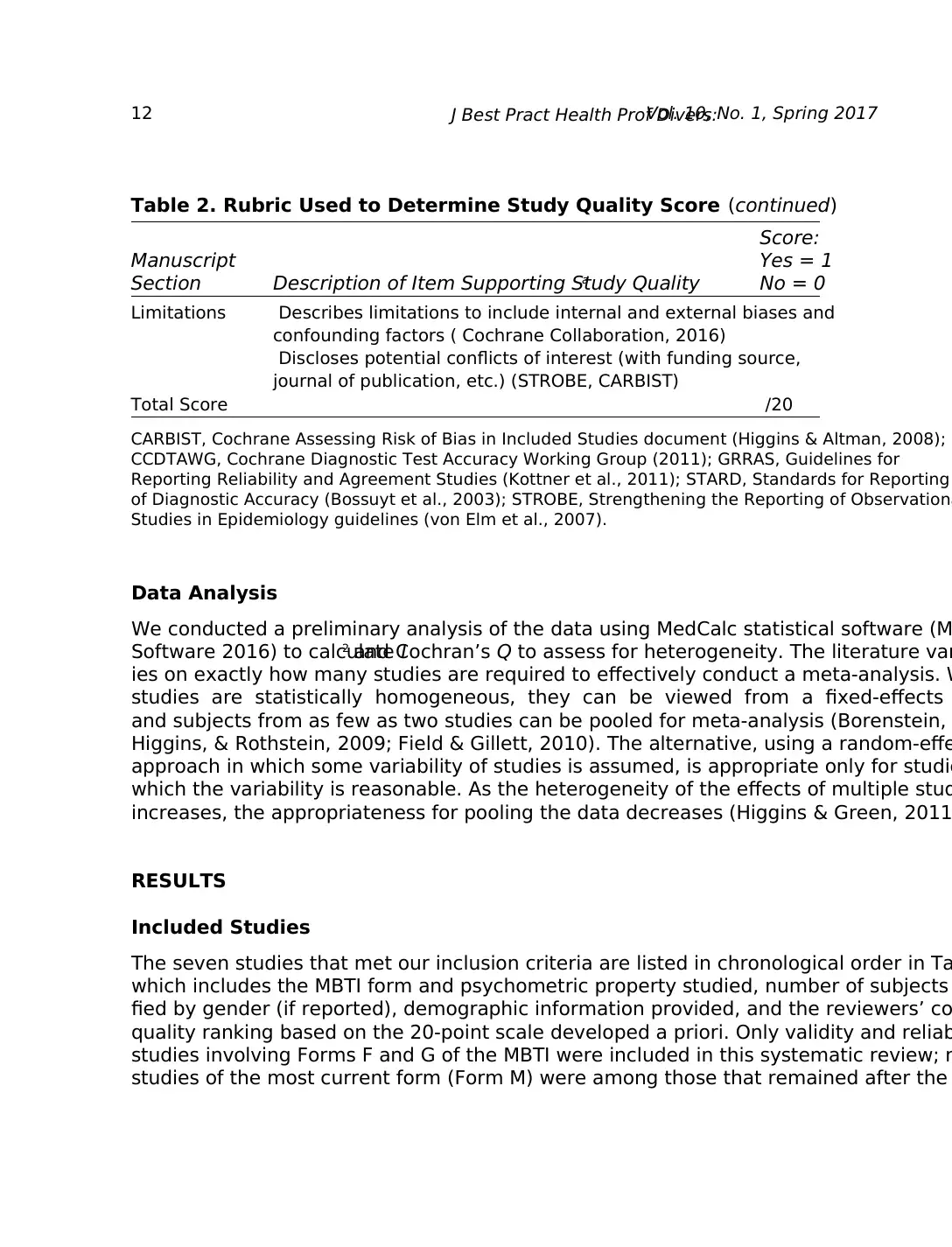

Table 2. Rubric Used to Determine Study Quality Score (continued)

Score:

Manuscript Yes = 1

Section Description of Item Supporting Study Qualitya No = 0

Limitations Describes limitations to include internal and external biases and

confounding factors ( Cochrane Collaboration, 2016)

Discloses potential conflicts of interest (with funding source,

journal of publication, etc.) (STROBE, CARBIST)

Total Score /20

CARBIST, Cochrane Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies document (Higgins & Altman, 2008);

CCDTAWG, Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group (2011); GRRAS, Guidelines for

Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (Kottner et al., 2011); STARD, Standards for Reporting

of Diagnostic Accuracy (Bossuyt et al., 2003); STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observationa

Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (von Elm et al., 2007).

Data Analysis

We conducted a preliminary analysis of the data using MedCalc statistical software (M

Software 2016) to calculate I2 and Cochran’s Q to assess for heterogeneity. The literature var

ies on exactly how many studies are required to effectively conduct a meta-analysis. W

studies are statistically homogeneous, they can be viewed from a fixed-effects

and subjects from as few as two studies can be pooled for meta-analysis (Borenstein,

Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Field & Gillett, 2010). The alternative, using a random-effe

approach in which some variability of studies is assumed, is appropriate only for studie

which the variability is reasonable. As the heterogeneity of the effects of multiple stud

increases, the appropriateness for pooling the data decreases (Higgins & Green, 2011

RESULTS

Included Studies

The seven studies that met our inclusion criteria are listed in chronological order in Ta

which includes the MBTI form and psychometric property studied, number of subjects

fied by gender (if reported), demographic information provided, and the reviewers’ co

quality ranking based on the 20-point scale developed a priori. Only validity and reliab

studies involving Forms F and G of the MBTI were included in this systematic review; n

studies of the most current form (Form M) were among those that remained after the

Table 2. Rubric Used to Determine Study Quality Score (continued)

Score:

Manuscript Yes = 1

Section Description of Item Supporting Study Qualitya No = 0

Limitations Describes limitations to include internal and external biases and

confounding factors ( Cochrane Collaboration, 2016)

Discloses potential conflicts of interest (with funding source,

journal of publication, etc.) (STROBE, CARBIST)

Total Score /20

CARBIST, Cochrane Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies document (Higgins & Altman, 2008);

CCDTAWG, Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group (2011); GRRAS, Guidelines for

Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (Kottner et al., 2011); STARD, Standards for Reporting

of Diagnostic Accuracy (Bossuyt et al., 2003); STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observationa

Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (von Elm et al., 2007).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 28

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.